Abstract

Dual-energy CT (DECT) imaging is a technique that extends the capabilities of CT beyond that of established densitometric evaluations. CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA) performed with dual-energy technique benefits from both the availability of low kVp CT data and also the concurrent ability to quantify iodine enhancement in the lung parenchyma. Parenchymal enhancement, presented as pulmonary perfused blood volume maps, may be considered as a surrogate of pulmonary perfusion. These distinct capabilities have led to new opportunities in the evaluation of pulmonary vascular diseases. Dual-energy CTPA offers the potential for improvements in pulmonary emboli detection, diagnostic confidence, and most notably severity stratification. Furthermore, the appreciated insights of pulmonary vascular physiology conferred by DECT have resulted in increased use for the assessment of pulmonary hypertension, with particular utility in the subset of patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. With the increasing availability of dual energy-capable CT systems, dual energy CTPA is becoming a standard-of-care protocol for CTPA acquisition in acute PE. Furthermore, qualitative and quantitative pulmonary vascular DECT data heralds promise for the technique as a “one-stop shop” for diagnosis and surveillance assessment in patients with pulmonary hypertension. This review explores the current application, clinical value, and limitations of DECT imaging in acute and chronic pulmonary vascular conditions. It should be noted that certain manufacturers and investigators prefer alternative terms, such as spectral or multi-energy CT imaging. In this review, the term dual energy is utilised, although readers can consider these terms synonymous for purposes of the principles explained.

Introduction

Dual-energy CT (DECT) imaging is a technique that extends the capabilities of CT beyond that of conventional densitometric evaluations. By simultaneously scanning at two different X-ray energies, the volumetric fraction of individual materials constituting the voxels can be quantified and either depicted on a colour-scaled overlay or removed from the image. The ability to quantify iodine has, in particular, led to multiple CT applications which improve visualization or quantification of regional tissue enhancement. One of the most explored areas from the inception of multidetector DECT has been pulmonary vascular imaging. With the increasing availability of dual-energy capable CT systems, dual-energy CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA) is becoming a standard-of-care protocol for CTPA acquisition, with potential for improvements in pulmonary emboli (PE) detection, diagnostic confidence, and severity stratification. Furthermore, the appreciated insights of pulmonary vascular physiology conferred by DECT have resulted in increased use for the assessment of pulmonary hypertension, with particular utility in the subset of patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH).

This review explores the current application and clinical value of DECT imaging in acute and chronic pulmonary vascular conditions. It should be noted that certain manufacturers and investigators prefer alternative terms, such as spectral or multi energy CT imaging. In this review, the term dual energy is utilised, although readers can consider these terms synonymous for purposes of the principles explained.

Technical overview of dual-energy computed tomography

Dual-energy CT (DECT) was first proposed and demonstrated in the 1970s.1,2 However, limitations in CT hardware and software technology hindered development such that the first commercially available multidetector system was not realized until 2006.3 Various approaches to the implementation of DECT have been developed.4 At the time of writing of this review, there are six commercially available configurations in use, including dual-source (DS),3 rapid peak kilovoltage switching (RS),5,6 dual-layer detector (DL),7 split-filter (SF),8 and sequential scanning or slow switching (SS)9,10 systems. In Table 1, the DECT configuration and technical parameters for acquisition are shown for different commercially available DECT systems. DS systems have two X-ray tubes and detectors oriented at approximately 90 degrees from each other and operate at two different energies to gather DECT data. In the RS method, the peak kilovoltage is rapidly changed between 80 and 140 kVp, while DL systems implement a detector with two layers separated by a filter to absorb low-energy photons in the top layer and high-energy photons in the bottom layer. The SF system utilizes a z-axis filter in the cranio-caudal direction of the patient.8 Half of the filter is gold (Au) and the other half is tin (Sn) for spectral shaping of the low and high energy datasets, respectively. SS mode requires imaging the anatomic range of interest with two separate axial or helical acquisitions.

Table 1.

Commercial DECT manufacturer and model systems with applicable technologies

| Manufacturer and Model | DECT Method | Available kVp Settings |

Tube Current Modulation | Field of View (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GE | ||||

| HD 750 | RS | 80/140 | No | 50 |

| Revolution CT | RS | 80/140 | No | 50 |

| Philips | ||||

| IQon | DL | 120, 140 | Yes | 50 |

| Siemens | ||||

| Flash | DS | 80/140Sn, 100/140Sn | Yes | 33 |

| Force | DS | 70/150Sn, 80/150Sn, 90/150Sn, 100/150Sn | Yes | 35 |

| Edge/Edge+ | SF | 120AuSn | Yes | 50 |

| Canon | ||||

| Genesis | SS | 80/135 | Yes | 50 |

| Prism | RS | 80/135 | Yes | 50 |

DL, Dual layer; DS, Dual source; RS, Rapid switching; SF, Split filtration; SS, Sequential scanning.

Element abbreviations following the kVp indicate the use of spectral shaping filters, e.g. tin (Sn) and gold (Au).

All the described DECT systems perform clinical studies remarkably well, yet there are relative advantages and disadvantages to different systems based on their technical configuration and reconstruction methodology (Table 2). Enhanced spectral separation11,12 and/or temporal resolution13 to ensure coregistration of the multi-energy datasets4 are amongst the most important parameters. Better spectral separation, for example, lowers noise in the reconstructed dual-energy images. DS and SS systems achieve this through added filtration (e.g. tin) inserted to modulate the high-energy spectrum. As a result, a significant portion of the low energy photons is removed from the high energy polyenergetic spectrum and the mean effective energy is increased. Temporal co-registration is important for two primary reasons: (1) ensuring imaging with both spectra during the same contrast phase and (2) reducing patient motion between projections. The DL system in particular achieves perfect temporal registration of the multi-energy datasets due to its unique design in which all projections are separated into low- and high-energy data at the detector rather than source, while RS methods are nearly perfect due to the energy modulation between individual projection angles.

Table 2.

Advantages and disadvantages of commercially available DECT hardware configurations

| Dual-energy CT Configuration | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Dual-source (DS) | Good spectral separation Tube current modulation for each tube |

Limited dual energy field of view Slight temporal misregistration |

| Rapid peak kilovoltage switching (RS) | Near perfect co-registration of multi energy datasets Full field of view |

No tube current modulation |

| Dual-layer detector (DL) | Perfect co-registration of multi energy datasets Dual-energy always “on” Tube current modulation Full field of view |

Poor spectral separation |

| Split filter (SF) | Full field of view Tube current modulation |

Poor spectral separation Cross-scatter between filters Slow scan time |

| Sequential scanning (SS) | Good spectral separation Tube current modulation |

Temporal resolution is poor Not recommended for contrast-enhanced studies |

Regardless of the approach to DECT, all systems generate two unique energy spectra. This is important when considering that the linear attenuation coefficient (µ) is dependent on the chemical composition or effective atomic number (Zeff) of specific materials at the effective energy of the X-ray beam. The mass density (ρ) of the material also contributes to the linear attenuation coefficient but is independent of the X-ray energy. In conventional CT, the linear attenuation coefficient of a material, normalized to that of water, is used to derive the CT number or Hounsfield Unit (HU). The mass attenuation coefficient (µ/ρ) of a material is defined as the linear attenuation coefficient divided by the material’s mass density and can be separated into the relative contributions from the photoelectric effect and Compton scatter, which can be estimated using data from the two energy spectra. However, the end goal of most DECT processing is to estimate the physical density of materials within a voxel rather than the ratio of photoelectric to Compton effect. To calculate material densities, DECT techniques assume the presence of a set of chosen basis materials with known mass attenuation coefficients [(µ/ρ)1 and (µ/ρ)2] in the diagnostic energy range (Energy ≤150 keV) that have unknown densities (ρ1 and ρ2).14 In practice, these basis materials typically consist of one low-attenuation material such as water or soft tissue and the other is high attenuation, such as iodine or calcium. The photoelectric and Compton components are solved algebraically and converted to densities by substituting in the known X-ray attenuation properties of two basis materials (e.g. water, iodine, calcium). All other materials are considered to be weighted sums of the basis materials.

Another advantage of DECT material decomposition is the ability to generate synthetic monoenergetic images, also referred to as virtual monoenergetic or virtual monochromatic images. These images have an appearance comparable to images obtained from a monoenergetic source, which do not suffer from beam hardening, and can display images in the range of 40 to 200 keV energies for many systems. The primary advantages of synthetic monoenergetic images are primarily improvements in low contrast detectability using low keV reconstructions (i.e. 50–60 keV) and the reduction of beam hardening artefacts15 attributed to imaging with a polyenergetic spectrum by utilizing high keV reconstructions (i.e. 110–140 keV). Mathematically, synthetic monoenergetic images are created by determining the energy-independent mass density of the basis materials and multiplying by their respective mass attenuation coefficients at the chosen keV. An alternative method is to apply the weighted sum of the low- and high-energy images to achieve images at the desired monoenergetic energy.

The primary advantage of DECT is conservation of the energy-dependent interactions. This provides invaluable insights to determine the effective atomic number for accurate assessment of the chemical composition contributions and mass density to the CT number through material decomposition of typically two or three basis materials. Material-specific images (e.g. iodine) can be created with material decomposition; conversely, materials can be suppressed to generate virtual noncontrast (VNC) images.

Dual-energy ct acquisition and post-processing

Regardless of the CT acquisition technology, similar principles apply to the acquisition and reconstruction of DECT CTPA studies. The acquisition radiation dose is split between the low and high kVp acquisition such that the overall dose is comparable or only minimally increased compared to single-energy CTPA acquisitions. In dual-source systems, the data from the two energy spectra are combined into a single reconstruction termed a weighted-average image which has the best noise and attenuation characteristics for primary conventional interpretation. In fast switching single-source systems, a simulated monoenergetic reconstruction of approximately 60–70 keV serves a similar purpose.16,17 In all systems, the low and high kVp spectral data are used to calculate the distribution of iodine in the lung parenchyma. Such images are termed perfused blood volume (PBV) or sometimes pulmonary blood volume images. PBV maps may be colour-coded and superimposed as a colour fused overlay over the anatomic data of the weighted average image. These maps reflect the enhancement of the lung parenchyma at a single time point, but can be used as a surrogate of perfusion.18,19 While conventional multiphasic pulmonary perfusion imaging suffers from limited anatomic coverage for true perfusion analysis, PBV maps comprehensively evaluate the entire lung parenchyma, are dose neutral and permit concomitant standard diagnostic interpretation of the remainder of the entire thorax.

At our institution, DECT thoracic exams are performed on second- (Definition Flash, Siemens Healthineers, Forchheim, Germany) and third-generation dual source (Definition Force, Siemens Healthineers, Forchheim, Germany), split filter (Definition Edge Plus, Siemens Healthineers, Forchheim, Germany), or rapid switching (HD750 and Revolution, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) systems. The acquisition parameters used for DECT imaging on each of these systems are described in Table 3.

Table 3.

DECT Parameters for Thoracic Imaging Acquisition

| DECT Scanner Type | Peak Kilovoltage (kVp) | Pitch | Tube Current Setting | Rotation Time (sec) | CTDIvol (mGy) | Reconstruction Kernel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dual source | 80/150Sna, 80/140Snb | 0.6 | 180/99a, 175/149b | 0.5 | 12.6a, 14.5b |

Qr40 |

| Split filter | 120AuSn | 0.25 | 700 | 0.5 | 15.2 | D30 |

| Rapid Switching | 80/140 | 1.375 | 495 | 0.6 | 15.4 | Standard |

Deviations in acquisition parameters noted for the Siemens Definition Force (a) and Flash (b). The tube current setting are manufacturer specific where reference mAs for dual source and split filtration and the fixed mAs for rapid switching are shown. The dosimetry above has been optimised for a cancer centre usage, lower doses are achievable in different patient populations.

Acute pulmonary embolism

Background issues

An evaluation of the potential role for dual-energy CTPA requires a consideration of the current clinicoradiological issues in the diagnosis of PE by conventional CTPA, the current predominant assessment technique for the detection of acute PE. The introduction and subsequent development of multidetector CT along with additional improvements of spatial and temporal resolution has led to serial enhancements in the image quality of CTPA and translated into high clinical diagnostic accuracy. However, due to a variety of reasons, including respiratory motion in tachypnoeic patients, image noise in larger patients, or beam hardening errors due to medical devices, or the patient’s inability to elevate their arms, a proportion of studies remain suboptimal. These artefacts may be a cause of false positive diagnoses of small pulmonary emboli, particularly isolated subsegmental pulmonary emboli.20 Conversely, in a different study evaluating expert review of initial CTPA interpretations, instances of missed small pulmonary emboli (false-negatives) exceeded false-positive diagnoses.21 Such data have led to some uncertainty for clinicians particularly with regard to the diagnosis of single subsegmental pulmonary emboli. In such instances, the 2019 guidance from the European Society of Cardiology recommends that referring clinicians discuss the finding with radiologists and/or seek a second opinion.22 Therefore, one potential consideration regarding the use of dual energy CTPA is whether this technique improves the detection accuracy of PE or increases confidence for the diagnosis in limited pulmonary embolism.

Notwithstanding the consideration of suboptimal studies, CTPA is widely accepted as the gold standard for PE detection. Indeed, this high accuracy has raised concerns that there is a risk of overdiagnosis in acute pulmonary embolism, whereby small and potentially clinically inconsequential, pulmonary emboli are detected. It has been argued that this overdiagnosis may theoretically place patients at greater risk by virtue of the consequences of radiation exposure, use of contrast media, and the impact of clinical therapy. Such assertions remain contentious23,24 but are partially supported by retrospective epidemiological data that suggest an increase in PE detection since the advent of CTPA without an associated change in PE age-adjusted mortality.25 It is further asserted that retrospective outcome data demonstrate a similar mortality in patients diagnosed with PE by CTPA or by ventilation perfusion imaging (V/Q) despite a higher detection rate by CTPA.26

Such considerations have not materially impacted the clinical utilization of CTPA, largely because the mortality and morbidity related to PE remains a significant concern, particularly in patients who develop associated right ventricular dysfunction (RVD). It is, however, recognized that pulmonary thromboembolic disease is heterogeneous in nature and hence its treatment paradigm is under constant review. At the severe end of the spectrum, thrombolysis is recommended both in Europe and North America for patients with massive PE (RVD and hypotensive) or patients with submassive PE (RVD but no hypotension) that are clinically deteriorating with no known bleeding risks.22,27 However, in practice, these recommendations are inconsistently adopted due to ongoing concerns with respect to haemorrhagic complications caused by thrombolysis. In lower risk patients with no evidence of RVD, anticoagulation alone is recommended, although more recently the American College of Chest Physicians have suggested that isolated subsegmental PE may be treated by surveillance rather than anticoagulation if there is a low risk of recurrent PE and no residual deep vein thrombosis.27 Notably, this is a Grade 2C recommendation (weak, low or very-low quality evidence), reflecting the difficulty in predicting the wide range of outcomes in patients with PE. Therefore, stratification of PE severity may be a more important potential role for DECT as a guide to refining management. Further, it is important to consider whether DECT may also be of use in determining which patients require follow-up for PE to exclude development of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH).

DECT impact on PE detection

There are two mechanisms by which DECT may potentially improve the detection accuracy and diagnostic confidence of pulmonary embolism. The first mechanism is by the simultaneous availability of low kVp CT imaging data. Alternatively, or additively, the utilization of PBV maps may potentially assist in CTPA diagnostic interpretation.

Low kVp images may be reconstructed separately on several implementations of DECT, including DS, DL and SS. In dual source acquisitions, there is complete separation of the two CT energy spectra into separate tubes and detectors. Otherwise, the low kVp spectral data can be integrated into a simulated low keV monoenergetic image in all systems. The keV of such reconstructions varies according to preference, although reflecting our clinical experience, one study of computer-aided detection at variable keV demonstrated an optimal balance of sensitivity and false-positive rates at 60–65keV.28

The undoubted value of low kVp imaging in improving the conspicuity of contrast-enhanced vascular structures, by virtue of increased photoelectric interactions, is long recognized and predates the introduction of multidetector dual-energy systems.29,30 The advent of dual source dual energy imaging permitted confirmation within individual patients, at the same phase of contrast opacification, that 80 kVp imaging demonstrated significantly improved pulmonary arterial opacification compared to simultaneously acquired 140 kVp images. Low kVp images rendered non-dedicated CT studies clinically equivalent to CTPA studies for the interpretation of PE, and salvaged suboptimal enhancement in otherwise non-diagnostic or partially diagnostic CTPA studies31 (Figure 1). Similar results have been demonstrated for low keV monoenergetic images.17 The benefits of low kVp imaging extend to the ability to utilize smaller volumes of contrast and reduced administration flow rates. This may be important in patients with renal impairment or poor venous access32,33 and can reduce the risk of contrast extravasation.34

Figure 1.

(a). A subsegmental pulmonary embolus is suspected in the right lower lobe vasculature on weighted average images 100kVp/Sn140kVp. (b). Diagnostic confidence is increased by review of the simultaneous low energy100kVp images with greater contrast conspicuity. (c) Conversely 140kVp images are unhelpful with poorer iodine conspicuity but are essential for the reconstruction of dual-energy material-specific images.

Low kVp images are inherently associated with higher image noise. However, studies have demonstrated that although noise is measurably higher at low kVp images overall, the increased signal-to-noise ratio improves radiologist qualitative evaluation of image quality.35,36 In recent years, the development of iterative reconstruction has led to improvement of the noise image characteristics of thin section low kVp imaging.36,37 However, the inherent image smoothing of iterative reconstruction has led to concerns that potentially small filling defects may be obscured by iterative reconstruction. More recent studies have suggested that 100% CTPA accuracy may be maintained with iterative reconstruction with as much as 88% simulated mAs reduction even at lower kVp acquisitions38 (Figures 2 and 3). Nonetheless, the quality of the low kVp images significantly affects the calculation and generation of material basis images, so most manufacturers recommend not performing dual-energy images in larger patients (variably defined as >105–110 kilograms) due to an increase in beam hardening in the low kVp spectrum.39,40 This remains a limitation of DECT implementation in larger patients.

Figure 2.

(a) 1 mm 100 kVp image from dual-energy acquisition reconstructed by filtered back projection, (b) by iterative reconstruction SAFIRE level three and (c) by higher level iterative reconstruction, SAFIRE level 5. Increasing iterative reconstruction improves image quality without sacrificing ability to evaluate for small pulmonary emboli.

Figure 3.

(a). 1.5 mm 100kVp/Sn140kVp perfused blood volume (PBV) map reconstructed with filtered back projection in a patient with PE (not shown) and right lung central defect. (b) image data reconstructed with SAFIRE three iterative reconstructions demonstrate improvement in image noise with reduced mottle in the central pulmonary arteries as well as in the PBV image.

While the above data support the use of the low kVp spectra from a DECT study confers a diagnostic detection advantage, this advantage is not unique to dual energy acquisition. Similar benefits can be acquired with a single-energy low kVp dose acquisition at the same lower kVp. Indeed, as all the radiation dose of a single-energy acquisition can be assigned to a lower kVp acquisition, either a further improvement of signal-to-noise ratio or a maintenance of signal to noise with reduced radiation dose can be achieved with a single-energy low-kVp acquisition. Therefore, in and of itself, low kVp availability is a useful benefit of dual-energy acquisition but not a sole justification for the performance of this technique.

A potential key advantage of DECT acquisition in CTPA is the availability of material differentiation images, specifically the availability of PBV images of the lung parenchyma. With regard to increased detection of PE, there are limited studies supporting this as a minor benefit.41 For example, in a study of 1144 oncological patients (372 discrete emboli), the review of PBV maps following CTPA interpretation highlighted an additional 27 emboli (78% subsegmental) and resulted in new PE diagnosis in only 1% of cases.42 Leithner and colleagues have suggested that the combined use of low-keV monoenergetic images and PBV maps may improve the diagnostic confidence in diagnosis of PE in patients with suboptimal contrast opacification.43 In our experience, this combined approach is indeed a minor potential benefit (Figure 4), although many suboptimal studies due to poor contrast opacification may also suffer from poor quality PBV images, even without the detrimental effect on these images by the frequent co-existence in these patients of respiratory or beam hardening artefacts.

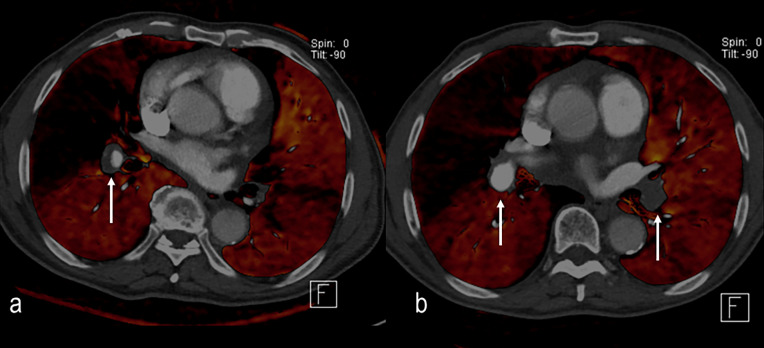

Figure 4.

(a). Weighted average 100 kVp/Sn140 kVp image. Single subsegmental right lower lobe pulmonary embolus suspected (arrow) but diagnosis is not certain. (b) Pulmonary perfused blood volume images demonstrate a corresponding single well-defined triangular defect (arrow) increasing radiological and clinical confidence in the diagnosis.

DECT impact on PE stratification

The presence of PBV defects distal to pulmonary emboli is not ubiquitous. Indeed, in early studies of dual-energy CTPA, only a small proportion of PE demonstrated associated PBV defects. However, when considering occlusive pulmonary emboli 82–95% demonstrated PBV defects compared to 6–9% in non-occlusive PE.44,45 This has led to the consideration that PBV defects may be an indicator of more physiologically significant pulmonary embolism. Several studies have demonstrated that an increased number and size of PBV defects correlates with adverse findings such as an increased pulmonary arterial obstruction indices,46,47 and features of right ventricular dysfunction, as measured by right ventricular and left ventricular diameter ratios (RV:LV).48–50 Increasing PBV defects have also been positively correlated to elevated Troponin I measurements in PE patients and inversely correlated to PaO2 (49). A pilot study by Bauer et al identified that there were two deaths and one readmission in 18 patients with >5% volumetric PBV defects, but none in the 35 patients with <5% of their lung volume affected.51 These results are corroborated by more recent studies.52,53 However, a recent study by Im et al found that although both PBV defects and a RV:LV >1 were predictive of 30-day mortality, in their study PBV defects did not provide additional predictive value compared to the RV:LV ratio54 (Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 5.

Occlusive pulmonary emboli in the right lower lobe segmental vasculature are associated with extensive perfusion defects. The right middle lobe demonstrates extensive perfusion reduction due to central embolus more cephalad (not shown). Patchy perfusion in the left lung is due to non-occlusive PE centrally.

Figure 6.

(a–c) Multifocal pulmonary perfused blood volume defects in a patient with multifocal pulmonary emboli. Defects of this extent are more often associated with right ventricular dysfunction, poor oxygenation and worse prognosis.

It is clear that PBV defects increase diagnostic confidence for determining whether pulmonary emboli are occlusive and therefore associated with poorer prognostic features reflecting morbidity and mortality. However, more work will be needed to determine the precise independent additive value that PBV defects confer and whether there is benefit to evaluating patients before and after treatment. It is also unknown whether PBV defects could be an indicator of patients requiring follow up to exclude evolution to chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension.55,56

It is important to recognize that not every defect in PBV maps reflects a genuine perfusion abnormality. Artefacts are common, most frequently in the upper lobes due to streaking from dense contrast within the central systemic veins. This artefact can be mitigated by using a smaller volume of high-density contrast, preferably with a saline flush, and implementing a caudocranial scan direction. Theoretically, dual-energy systems that utilize raw data reconstruction (e.g. rapid kVp switching) may correct for such beam hardening artefacts, which are already embedded in the images utilized by image-based reconstruction systems (e.g. dual source). In practice, both systems can be affected by such artefacts, largely due to the preferential attenuation of the low-energy spectrum in these cases. Additional artefacts may also occur due to motion near the diaphragm or by cardiac pulsation. Familiarity with these “windmill” or ovoid configuration appearances is essential to avoid misdiagnosis.

Users must also be aware of the variations of reconstruction techniques used by different manufacturers to reconstruct dual-energy pulmonary blood volume images. For example, some manufacturers utilize a thresholding system, limiting dual-energy calculation to a range of lung values excluding larger vessels. This enables faster reconstruction, material differentiation that is optimized for lung parenchymal densities, and fused images that retain grayscale opacification of the pulmonary arteries. A disadvantage of this approach that should be recognized is that areas of lung that are either denser than normal lung (ground glass opacity, consolidation, infarction) or much less dense (bullous emphysema) are excluded from the calculation and may be misinterpreted as areas of reduced perfusion. This does not apply to single source systems using raw data calculation that calculate iodine distribution across all tissues, including lung, vascular, and soft tissues. The disadvantage of this universal calculation approach is that subtle differences of parenchymal opacity may be qualitatively less evident since the scale of enhancement depicted is much broader to account for large vessels. Neither approach can be considered correct or incorrect. Rather, users should be familiar with the technique used by their system (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Differences in image reconstruction appearance. Same patient imaged initially with dual-source CT pulmonary angiography (a), with study interrupted due to patient-related factors. Repeated 4 h later with single-source rapid kVp switching scanner (b). Dual-source imaging thresholds out the central vasculature and mediastinum for perfused blood volume analysis, evaluating only the smaller vessels and parenchyma. The central vessels are depicted as per conventional grayscale angiography. In single-source technique, the entire image, including central vessels and mediastinum, is evaluated and colour-coded for calculated enhancement. Note that the difference in range of enhancement assessed also results in differences in the scale depicted and the conspicuity of a perfusion defect in the right upper lobe secondary to embolus.

Pulmonary hypertension

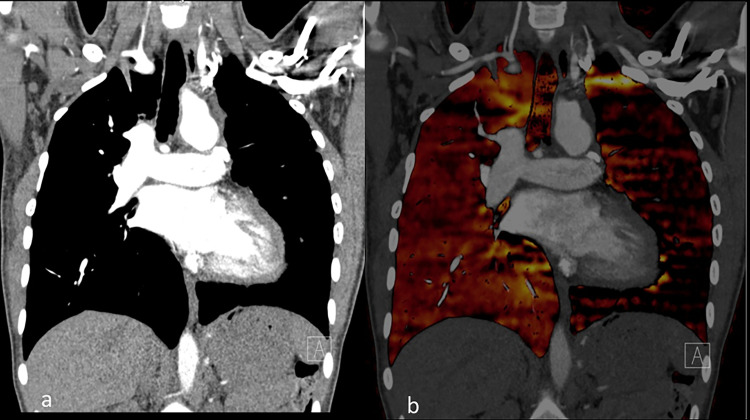

Building on the foundation of data demonstrating that more severe acute pulmonary embolism, with occlusive pulmonary emboli and resultant PBV defects, is more likely to be associated with right heart impairment and worse prognosis, it is not surprising that the utility of dual energy CTPA imaging has been explored in the similar entity of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH). In CTEPH, vascular perfusion is even more variable due to chronic, regionally heterogeneous occlusive plexogenic arteriopathy, in situ thrombosis, and vascular remodelling. Early DECT studies confirmed that these changes were readily appreciable with PBV maps.57–59 Historically, the perceived value of CT in the clinical evaluation of CTEPH has been limited by studies suggesting reduced sensitivity compared to V/Q imaging, particularly for small peripheral vessel disease.60,61 In many instances, such evaluations suffered from comparisons to early generation MDCT and suboptimal gold standard definition of CTEPH disease, including assumptions that all regional mismatched perfusion defects at V/Q were secondary to CTEPH. Increasingly, both at V/Q and CT imaging, we are aware that such variability in perfusion, visualized as either CT mosaic attenuation or quantified by PBV imaging, is not limited to CTEPH and is also seen in other causes of pulmonary hypertension.56,62 In direct comparison to V/Q and SPECT, an encouraging correlation to DECT studies has been demonstrated.63,64 Recent publications evaluating PBV images in CTEPH demonstrate sensitivity and specificity above 95%, while some earlier studies had lower specificity due to streak artefacts (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

(a). Initial diagnosis of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) with eccentric thrombus in the right interlobar artery and extensive peripheral defects in perfusion on perfused blood volume (PBV) imaging. (b) 4 months following anticoagulation and vasodilator therapy there is improvement of the right sided central thrombus but the large central defect in perfusion persists as well as several smaller peripheral defects bilaterally. Thrombus persists in the left-sided central vessels. The detection of smaller peripheral perfusion defects in CTEPH appears to be an advantage of dual-energy CT over conventional CT pulmonary angiography.

Inherently, comparing DECT to V/Q or SPECT imaging may not be most appropriate. Relative to V/Q imaging, DECT is performed during a breath-hold. Additionally, the higher resolution of current DECT systems, coupled with the observation that in patients with acute PE small triangular PBV defects without associated visible proximal endoluminal clot similarly respond to anticoagulant therapy lends credence to the premise that DECT may indeed be capable of detecting small peripheral perfusion defects that earlier studies suggested were only observed on physiological V/Q imaging.44,63 Coupled with a more anatomically precise delineation of perfusion and vascular abnormalities, DECT is increasingly becoming an essential tool in the management of CTEPH as well as the broader category of pulmonary hypertension.65

The diagnostic capabilities of DECT in CTEPH have been more widely adopted in the evaluation of patients with pulmonary hypertension (PH).66 Pulmonary hypertension is an often insidious complication of an aetiologically diverse spectrum of conditions characterized by elevated pulmonary arterial pressures. Delayed diagnosis in not uncommon, worsening already poor morbidity and mortality rates. Although echocardiography can be suggestive of CTEPH, definitive diagnosis requires right heart catheterization for confirmation, which is an invasive procedure with inherent risks. Additionally, a series of new, and often expensive, vasodilator therapies have emerged which are only suitable for treatment in certain subtypes of pulmonary hypertension. This has increased research into the quantitative evaluation of DECT pulmonary vascular imaging as a surrogate for right heart catheterization in patients with suspected pulmonary hypertension as well as non-invasive monitoring for patients treated with therapeutic vasodilators.56

In an initial study, Ameli-Renani et al demonstrated that dual-energy-derived central pulmonary arterial enhancement was increased and volumetric calculated whole-lung PBV-derived enhancement decreased in patients with pulmonary hypertension, reflecting a delay in contrast transit from the central vessels to the lung parenchyma.67 A ratio of central pulmonary artery enhancement to whole-lung PBV enhancement differentiated pulmonary hypertension patients with elevated pulmonary arterial pressures from non-PH patients. Additionally, this ratio was correlated with pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), a key right heart catheter-determined metric used in the management of PH patients. Such ratios of central to peripheral enhancement have been corroborated in further studies68 and have been utilized to guide and assess regional response to selective angioplasty in patients with CTEPH.69

DECT in chronic pulmonary vascular imaging is an emerging and exciting field of study. Amongst other efforts, DECT metrics have demonstrated potential in differentiating patients with chronic embolic disease without pulmonary hypertension from those with CTEPH,70 assessing the severity of CTEPH,71 and potentially differentiating different aetiologies of pulmonary hypertension72 (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

(a) Initial evaluation with dual energy CT demonstrates a right lower lobe embolus (arrow) with peripheral perfusion defect. (b) Follow-up study 14 months later demonstrates near complete resolution of the embolus but a residual linear defect in the vessel. The resolution of the PBV defect aids in discriminating that this reflects chronic thrombus rather than chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension.

Additionally, DECT may offer new additional insights into pulmonary vascular physiology in patients with acute and chronic pulmonary vascular disease. In studies using a dual-phase evaluation of the lung parenchyma, it has been suggested that acute and chronic PE can be differentiated by in-filling of initial PBV defects in chronic PE compared to the absence of in-filling in acute PE.68,73–75 It has been suggested that the possible cause is development of systemic bronchial collateral supply in chronic disease. However, a recent study by Bacon et al76 in which prospective right heart catheterization was used to corroborate dual-phase dual-energy CT also evaluated the morphology and size of bronchial arteries in patients with PH. Although enlarged bronchial arteries were more common in PH patients, the size and extent of the arteries did not correlate with increase in volumetric whole lung enhancement on the delayed phase CT, the best correlate of pulmonary vascular resistance76 (Figure 10). Therefore, although the presence of systemic blood flow from bronchial arteries may be a contributory factor, it may simply be that the prime reason for delayed lung enhancement in patients with PH is altered pulmonary arterial perfusion due to structural haemodynamic changes in the pulmonary arteries themselves.

Figure 10.

Dual time point dual-energy CT images in a patient with pulmonary hypertension. (a) Pulmonary arterial phase imaging demonstrates peripheral perfusion reduction defects. (b) Imaging performed 7 s later in the systemic arterial phase demonstrates global increase in pulmonary parenchymal perfusion and in-filling of pulmonary peripheral defects. This delayed increase in pulmonary parenchymal enhancement is a feature of pulmonary hypertension and correlates with pulmonary vascular resistance.

Overall, the advances in DECT imaging of PH, combined with its advantages of increased resolution, regional information, and quantitative evaluation, are promising for eventual replacement of V/Q imaging as a “one stop shop” for the evaluation of patients with PH.65,77

Pulmonary vascular evaluation in other diseases

The ability to non-invasively assess or monitor lung perfusion is of interest in a variety of diseases. Early evaluations focused on the physiological perfusion alterations in emphysema.78,79 Dual-energy pulmonary vascular metrics have been correlated to pulmonary function tests,80 and early data suggest that in combination with xenon ventilation, dual-energy perfusion CT may be used as an alternative to preoperative quantitative V/Q in patients prior to lung resection.81

More recently, the increased incidence of PE in patients with COVID-19 has led to a series of DECT studies evaluating the diffusely abnormal pulmonary microvasculature in these patients.82 In one representative study by Remy-Jardin et al83, widespread microangiopathic changes were detected by PBV imaging in 66% of patients with residual pulmonary symptoms at 3 months following hospitalization for COVID-19, including findings in a minority of patients with otherwise normal-appearing lung parenchyma.

Many applications of dual-energy CT utilize the combination of pulmonary blood volume maps and iodine quantification within the larger central vasculature to characterize congenital combined abnormalities of the vasculature and pulmonary parenchyma84 (Figure 11). A further area in which iodine enhancement discrimination can be particularly useful is in the occasional differentiation of large central bland pulmonary emboli from enhancing pulmonary artery sarcomas (Figure 12).85

Figure 11.

Congenital abnormality evaluated by dual-energy CT pulmonary angiography in a patient with Fallot’s tetralogy (a) coronal image demonstrates marked reduction in size of the left-sided central pulmonary arterial vasculature. (b) corresponding perfused blood volume image highlights the marked reduction in perfusion of the left lung.

Figure 12.

25-year-old male presented with symptoms of acute PE and large central filling defect on CT pulmonary angiography. Central linear high attenuation was concerning for possible enhancement within the filling defect. (b) Dual-energy calculated perfused blood volume images confirm reduction in perfusion of the right lung. (c) Iodine calculation performed of the central vessels and soft tissues demonstrates intermediate iodine uptake in the filling defect, above background uptake in the paraspinal musculature. The appearances were concerning for an enhancing intravascular tumour (d). Confirmation of corresponding metabolic activity in the same location at 18-fluorodeoxyglucose PET-CT imaging. Lesion was histologically confirmed as a leiomyosarcoma at resection.

Implementation and future directions

The initial implementation of dual-energy CT in general was restricted by the additional cost of systems that were capable of acquiring images using this technique, initially limited to more expensive dual-source CT systems. The advent of several single source acquisition technologies and increased market competition has reduced the cost premium for dual-energy-capable systems substantially. The increased availability of dual-energy systems has developed in parallel to the increasing body of scientific knowledge supporting the use of dual-energy imaging across multiple body systems.

Adoption of dual energy imaging in acute PE imaging is becoming more and more prevalent as radiologists become more familiar with the imaging characteristics of these studies. Evaluation of pulmonary hypertension with DECT is increasing but remains more prevalent in expert centres. Across DECT pulmonary vascular imaging, adoption requires not only technical availability but knowledge of how to optimize image acquisition, workflow adaptations for the additional image sets, and experience to interpret the unique image types, including PBV maps and monoenergetic images.

Notably, the availability of dual energy CT in a CTPA study is not limited to evaluation of the pulmonary vasculature. Incidentally detected other pathologies can be evaluated by other material decomposition images that can be generated retrospectively on many systems, including VNC imaging for evaluation of the pre-contrast appearance or enhancement of incidentally detected abnormalities.

The near-term direction of dual-energy CT research for pulmonary vascular disease diagnosis and monitoring will likely largely be in the continued validation of the unique added value that DECT acquisitions have in different clinical scenarios. This is likely to increasingly relate to the standardization of quantitative DECT metrics and their automated extraction from images. As techniques become more standardized, we are increasingly likely to move from HU-based metrics to parameters incorporating iodine concentrations, such as whole-lung PBV enhancement.

Technological innovation in dual-energy CT continues at a remarkable pace. Image noise remains a key consideration, limiting the accuracy of dual-energy calculations. One of the potentially transformational technological evolutions that is in current development is the advent of photon counting detector CT. With regard to multi-energy CT acquisition, photon counting detector CT offers several intriguing possibilities such as the ability to threshold out electronic noise to enable scans at lower radiation doses,86 and to allow binning of individual photons by energy, permitting true multi-energy imaging and concepts such as true k-edge imaging. Furthermore, current prototypes of clinical photon counting detector CT allow for increased spatial resolution,87 which may be particularly useful in the diagnosis of pulmonary disease aetiologies.

Conclusion

Dual-energy CT imaging of the pulmonary vasculature represents a currently available technique that can be implemented with a wide variety of currently available CT systems. From a patient perspective, dual-energy CTPA studies have an identical patient scanning experience, including a similar radiation dose profile. Yet these studies, appropriately processed, may provide additional information by virtue of the simultaneous availability of low kVp imaging with greater iodine conspicuity and, uniquely, through the availability of PBV enhancement maps that act as a surrogate for true perfusion imaging. DECT images confer additional diagnostic information, particularly with regard to the evaluation of pulmonary embolism severity and may offer further physiological insights and haemodynamic correlates to guide the management of patients with pulmonary hypertension. As the technological opportunities and our knowledge base evolve, it is important for radiologists to be aware of the status of current and developing dual-energy CT applications that provide additional value from existing images that they may already be routinely creating.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: RRL serves as a member of an advisory board for GE Healthcare. IV has had prior remote research support from Siemens Medical Systems and GE Healthcare (>5years previously). MCG has no disclosures. KS has no disclosures. MCJ has no disclosures.

Funding: RRL currently receives MDACC institutional funding, in-kind and salary support from Siemens Healthineers, and has extramural support from NIH/NHLBI (5R01HL141831-03), USDA (FP11156), and NASA (80NSSC18K1639).

Contributor Information

Ioannis Vlahos, Email: ivlahos@mdanderson.org.

Megan C Jacobsen, Email: MCJacobsen@mdanderson.org.

Myrna C Godoy, Email: MGodoy@mdanderson.org.

Konstantinos Stefanidis, Email: kstefanidis@nhs.net.

Rick R Layman, Email: RRLayman@mdanderson.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hounsfield GN. Computerized transverse axial scanning (tomography). 1. description of system. Br J Radiol 1973; 46: 1016–22. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-46-552-1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez RE, Macovski A. Energy-Selective reconstructions in X-ray computerized tomography. Phys Med Biol 1976; 21: 733–44. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/21/5/002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flohr TG, McCollough CH, Bruder H, Petersilka M, Gruber K, Süss C, et al. First performance evaluation of a dual-source CT (DSCT) system. Eur Radiol 2006; 16: 256–68. doi: 10.1007/s00330-005-2919-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCollough CH, Boedeker K, Cody D, Duan X, Flohr T, Halliburton SS, et al. Principles and applications of multienergy CT: report of AAPM task group 291. Med Phys 2020; 47: e881–912. doi: 10.1002/mp.14157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang D, Li X, Liu B. Objective characterization of Ge discovery CT750 HD scanner: gemstone spectral imaging mode. Med Phys 2011; 38: 1178–88. doi: 10.1118/1.3551999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boedeker K, Vaishnav J, Zhang R, Yu Z, Nakanishi S. Dual energy – the Canon approach. In: Alkadhi H, Euler A, Maintz D, Sahani D, eds.Spectral imaging: dual-energy, multi-energy and photon counting CT, 2nd Ed. 2nd Edition. Berlin, Germany: Springer-VerlagIn Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozguner O, Dhanantwari A, Halliburton S, Wen G, Utrup S, Jordan D. Objective image characterization of a spectral CT scanner with dual-layer detector. Phys Med Biol 2018; 63: 025027. doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/aa9e1b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Euler A, Parakh A, Falkowski AL, Manneck S, Dashti D, Krauss B, et al. Initial results of a single-source dual-energy computed tomography technique using a Split-Filter: assessment of image quality, radiation dose, and accuracy of dual-energy applications in an in vitro and in vivo study. Invest Radiol 2016; 51: 491–8. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diekhoff T, Engelhard N, Fuchs M, Pumberger M, Putzier M, Mews J, et al. Single-Source dual-energy computed tomography for the assessment of bone marrow oedema in vertebral compression fractures: a prospective diagnostic accuracy study. Eur Radiol 2019; 29: 31–9. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5568-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaytor RJ, Rajbabu K, Jones PA, McKnight L. Determining the composition of urinary tract calculi using stone-targeted dual-energy CT: evaluation of a low-dose scanning protocol in a clinical environment. Br J Radiol 2016; 89: 20160408. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20160408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Primak AN, Giraldo JCR, Eusemann CD, Schmidt B, Kantor B, Fletcher JG, et al. Dual-source dual-energy CT with additional tin filtration: dose and image quality evaluation in phantoms and in vivo. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2010; 195: 1164–74. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.3956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Primak AN, Ramirez Giraldo JC, Liu X, Yu L, McCollough CH. Improved dual-energy material discrimination for dual-source CT by means of additional spectral filtration. Med Phys 2009; 36: 1359–69. doi: 10.1118/1.3083567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li B, Yadava G, Hsieh J. Quantification of head and body CTDI(VOL) of dual-energy x-ray CT with fast-kVp switching. Med Phys 2011; 38: 2595–601. doi: 10.1118/1.3582701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelcz F, Joseph PM, Hilal SK. Noise considerations in dual energy CT scanning. Med Phys 1979; 6: 418–25. doi: 10.1118/1.594520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu L, Leng S, McCollough CH. Dual-Energy CT-based monochromatic imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2012; 199(5 Suppl): S9–15. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.9121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delesalle M-A, Pontana F, Duhamel A, Faivre J-B, Flohr T, Tacelli N, et al. Spectral optimization of chest CT angiography with reduced iodine load: experience in 80 patients evaluated with dual-source, dual-energy CT. Radiology 2013; 267: 256–66. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Apfaltrer P, Sudarski S, Schneider D, Nance JW, Haubenreisser H, Fink C, et al. Value of monoenergetic low-kV dual energy CT datasets for improved image quality of CT pulmonary angiography. Eur J Radiol 2014; 83: 322–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2013.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chae EJ, Kim N, Seo JB, Park J-Y, Song J-W, Lee HJ, et al. Prediction of postoperative lung function in patients undergoing lung resection: dual-energy perfusion computed tomography versus perfusion scintigraphy. Invest Radiol 2013; 48: 622–7. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e318289fa55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thieme SF, Becker CR, Hacker M, Nikolaou K, Reiser MF, Johnson TRC. Dual energy CT for the assessment of lung perfusion--correlation to scintigraphy. Eur J Radiol 2008; 68: 369–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.07.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hutchinson BD, Navin P, Marom EM, Truong MT, Bruzzi JF. Overdiagnosis of pulmonary embolism by pulmonary CT angiography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2015; 205: 271–7. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.13938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kligerman SJ, Mitchell JW, Sechrist JW, Meeks AK, Galvin JR, White CS. Radiologist performance in the detection of pulmonary embolism: features that favor correct interpretation and risk factors for errors. J Thorac Imaging 2018; 33: 350–7. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0000000000000361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Konstantinides SV, Meyer G, Becattini C, Bueno H, Geersing G-J, Harjola V-P. 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European respiratory Society (ERS): the task force for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism of the European Society of cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2019; 41: 543–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Remy-Jardin M. Are we overdiagnosing pulmonary embolism? "No". J Thorac Imaging 2018; 33: 348–9. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0000000000000366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tan S, Haramati LB. Are we Overdiagnosing pulmonary embolism? Yes!: paradigm shift in pulmonary embolism. J Thorac Imaging 2018; 33: 346–7. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0000000000000365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wiener RS, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Time trends in pulmonary embolism in the United States: evidence of overdiagnosis. Arch Intern Med 2011; 171: 831–7. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson DR, Kahn SR, Rodger MA, Kovacs MJ, Morris T, Hirsch A, et al. Computed tomographic pulmonary angiography vs ventilation-perfusion lung scanning in patients with suspected pulmonary embolism: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2007; 298: 2743–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.23.2743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, Blaivas A, Jimenez D, Bounameaux H, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTe disease: chest guideline and expert panel report. Chest 2016; 149: 315–52. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2015.11.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma G, Dou Y, Dang S, Yu N, Guo Y, Yang C, et al. Influence of Monoenergetic images at different energy levels in dual-energy spectral CT on the accuracy of computer-aided detection for pulmonary embolism. Acad Radiol 2019; 26: 967–73. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2018.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schueller-Weidekamm C, Schaefer-Prokop CM, Weber M, Herold CJ, Prokop M. CT angiography of pulmonary arteries to detect pulmonary embolism: improvement of vascular enhancement with low kilovoltage settings. Radiology 2006; 241: 899–907. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2413040128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakayama Y, Awai K, Funama Y, Liu D, Nakaura T, Tamura Y, et al. Lower tube voltage reduces contrast material and radiation doses on 16-MDCT aortography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2006; 187: W490–7. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.0471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Godoy MCB, Heller SL, Naidich DP, Assadourian B, Leidecker C, Schmidt B, et al. Dual-energy MDCT: comparison of pulmonary artery enhancement on dedicated CT pulmonary angiography, routine and low contrast volume studies. Eur J Radiol 2011; 79: e11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.12.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yuan R, Shuman WP, Earls JP, Hague CJ, Mumtaz HA, Scott-Moncrieff A, et al. Reduced iodine load at CT pulmonary angiography with dual-energy monochromatic imaging: comparison with standard CT pulmonary angiography—a prospective randomized trial. Radiology 2012; 262: 290–7. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11110648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boos J, Kröpil P, Lanzman RS, Aissa J, Schleich C, Heusch P, et al. CT pulmonary angiography: simultaneous low-pitch dual-source acquisition mode with 70 kVp and 40 ml of contrast medium and comparison with high-pitch spiral dual-source acquisition with automated tube potential selection. Br J Radiol 2016; 89: 20151059. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20151059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heshmatzadeh Behzadi A, Farooq Z, Newhouse JH, Prince MR. Mri and CT contrast media extravasation: a systematic review. Medicine 2018; 97: e0055. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li X, Ni QQ, Schoepf UJ, Wichmann JL, Felmly LM, Qi L, et al. 70-kVp High-pitch computed tomography pulmonary angiography with 40 mL contrast agent: initial experience. Acad Radiol 2015; 22: 1562–70. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2015.08.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leithner D, Gruber-Rouh T, Beeres M, Wichmann JL, Mahmoudi S, Martin SS, et al. 90-kVp low-tube-voltage CT pulmonary angiography in combination with advanced modeled iterative reconstruction algorithm: effects on radiation dose, image quality and diagnostic accuracy for the detection of pulmonary embolism. Br J Radiol 2018; 91: 20180269. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20180269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McLaughlin PD, Liang T, Homiedan M, Louis LJ, O'Connell TW, Krzymyk K, et al. High pitch, low voltage dual source CT pulmonary angiography: assessment of image quality and diagnostic acceptability with hybrid iterative reconstruction. Emerg Radiol 2015; 22: 117–23. doi: 10.1007/s10140-014-1230-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sauter A, Koehler T, Fingerle AA, Brendel B, Richter V, Rasper M, et al. Ultra low dose CT pulmonary angiography with iterative reconstruction. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0162716. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marin D, Pratts-Emanuelli JJ, Mileto A, Husarik DB, Bashir MR, Nelson RC, et al. Interdependencies of acquisition, detection, and reconstruction techniques on the accuracy of iodine quantification in varying patient sizes employing dual-energy CT. Eur Radiol 2015; 25: 679–86. doi: 10.1007/s00330-014-3447-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parakh A, An C, Lennartz S, Rajiah P, Yeh BM, Simeone FJ, et al. Recognizing and minimizing artifacts at dual-energy CT. Radiographics 2021; 41: 509–23. doi: 10.1148/rg.2021200049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Okada M, Kunihiro Y, Nakashima Y, Nomura T, Kudomi S, Yonezawa T, et al. Added value of lung perfused blood volume images using dual-energy CT for assessment of acute pulmonary embolism. Eur J Radiol 2015; 84: 172–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2014.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weidman EK, Plodkowski AJ, Halpenny DF, Hayes SA, Perez-Johnston R, Zheng J, et al. Dual-energy CT angiography for detection of pulmonary emboli: incremental benefit of iodine maps. Radiology 2018; 289: 546–53. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2018180594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leithner D, Wichmann JL, Vogl TJ, Trommer J, Martin SS, Scholtz J-E, et al. Virtual Monoenergetic imaging and iodine perfusion maps improve diagnostic accuracy of dual-energy computed tomography pulmonary angiography with suboptimal contrast attenuation. Invest Radiol 2017; 52: 659–65. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pontana F, Faivre J-B, Remy-Jardin M, Flohr T, Schmidt B, Tacelli N, et al. Lung perfusion with dual-energy multidetector-row CT (MDCT): feasibility for the evaluation of acute pulmonary embolism in 117 consecutive patients. Acad Radiol 2008; 15: 1494–504. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2008.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thieme SF, Johnson TRC, Lee C, McWilliams J, Becker CR, Reiser MF, et al. Dual-Energy CT for the assessment of contrast material distribution in the pulmonary parenchyma. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2009; 193: 144–9. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Qanadli SD, El Hajjam M, Vieillard-Baron A, Joseph T, Mesurolle B, Oliva VL, et al. New CT index to quantify arterial obstruction in pulmonary embolism: comparison with angiographic index and echocardiography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001; 176: 1415–20. doi: 10.2214/ajr.176.6.1761415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mastora I, Remy-Jardin M, Masson P, Galland E, Delannoy V, Bauchart J-J, et al. Severity of acute pulmonary embolism: evaluation of a new spiral CT angiographic score in correlation with echocardiographic data. Eur Radiol 2003; 13: 29–35. doi: 10.1007/s00330-002-1515-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chae EJ, Seo JB, Jang YM, Krauss B, Lee CW, Lee HJ, et al. Dual-energy CT for assessment of the severity of acute pulmonary embolism: pulmonary perfusion defect score compared with CT angiographic obstruction score and right ventricular/left ventricular diameter ratio. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2010; 194: 604–10. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.2681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thieme SF, Ashoori N, Bamberg F, Sommer WH, Johnson TRC, Leuchte H, et al. Severity assessment of pulmonary embolism using dual energy CT - correlation of a pulmonary perfusion defect score with clinical and morphological parameters of blood oxygenation and right ventricular failure. Eur Radiol 2012; 22: 269–78. doi: 10.1007/s00330-011-2267-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou Y, Shi H, Wang Y, Kumar AR, Chi B, Han P. Assessment of correlation between CT angiographic clot load score, pulmonary perfusion defect score and global right ventricular function with dual-source CT for acute pulmonary embolism. Br J Radiol 2012; 85: 972–9. doi: 10.1259/bjr/40850443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bauer RW, Frellesen C, Renker M, Schell B, Lehnert T, Ackermann H, et al. Dual energy CT pulmonary blood volume assessment in acute pulmonary embolism - correlation with D-dimer level, right heart strain and clinical outcome. Eur Radiol 2011; 21: 1914–21. doi: 10.1007/s00330-011-2135-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takx RAP, Henzler T, Schoepf UJ, Germann T, Schoenberg SO, Shirinova A, et al. Predictive value of perfusion defects on dual energy cta in the absence of thromboembolic clots. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2017; 11: 183–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2017.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perez-Johnston R, Plodkowski AJ, Halpenny DF, Hayes SA, Capanu M, Araujo-Filho JAB, et al. Perfusion defects on dual-energy cta in patients with suspected pulmonary embolism correlate with right heart strain and lower survival. Eur Radiol 2021; 31: 2013–21. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-07333-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Im DJ, Hur J, Han KH, Lee H-J, Kim YJ, Kwon W, et al. Acute pulmonary embolism: retrospective cohort study of the predictive value of perfusion defect volume measured with dual-energy CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2017; 209: 1015–22. doi: 10.2214/AJR.17.17815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nagayama H, Sueyoshi E, Hayashida T, Ashizawa K, Sakamoto I, Uetani M. Quantification of lung perfusion blood volume (lung PBV) by dual-energy CT in pulmonary embolism before and after treatment: preliminary results. Clin Imaging 2013; 37: 493–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2012.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ameli-Renani S, Rahman F, Nair A, Ramsay L, Bacon JL, Weller A, et al. Dual-Energy CT for imaging of pulmonary hypertension: challenges and opportunities. Radiographics 2014; 34: 1769–90. doi: 10.1148/rg.347130085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shimokawahara H, Ijuin S, Nuruki N, Sonoda M. Effectiveness of dual-energy computed tomography in providing information on pulmonary perfusion and vessel morphology in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Circ J 2015; 79: 2517–9. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-15-0537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hoey ETD, Mirsadraee S, Pepke-Zaba J, Jenkins DP, Gopalan D, Screaton NJ. Dual-energy CT angiography for assessment of regional pulmonary perfusion in patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: initial experience. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2011; 196: 524–32. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.4842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hoey ETD, Agrawal SKB, Ganesh V, Gopalan D, Screaton NJ. Dual energy CT pulmonary angiography: findings in a patient with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Thorax 2009; 64: 1012. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.112128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pitton MB, Kemmerich G, Herber S, Schweden F, Mayer E, Thelen M. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: diagnostic impact of Multislice-CT and selective Pulmonary-DSA. Rofo 2002; 174: 474–9. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-25117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tunariu N, Gibbs SJR, Win Z, Gin-Sing W, Graham A, Gishen P, et al. Ventilation-Perfusion scintigraphy is more sensitive than multidetector CtpA in detecting chronic thromboembolic pulmonary disease as a treatable cause of pulmonary hypertension. J Nucl Med 2007; 48: 680–4. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.106.039438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Talwar A, Sarkar P, Patel N, Shah R, Babchyck B, Palestro CJ. Correlation of a scintigraphic pulmonary perfusion index with hemodynamic parameters in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Thorac Imaging 2010; 25: 320–5. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0b013e3181ced14d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thieme SF, Graute V, Nikolaou K, Maxien D, Reiser MF, Hacker M, et al. Dual energy CT lung perfusion imaging--correlation with SPECT/CT. Eur J Radiol 2012; 81: 360–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.11.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nakazawa T, Watanabe Y, Hori Y, Kiso K, Higashi M, Itoh T, et al. Lung perfused blood volume images with dual-energy computed tomography for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: correlation to scintigraphy with single-photon emission computed tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2011; 35: 590–5. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e318224e227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kay FU. Could dual-energy CT become the "one-stop shop" modality in pulmonary hypertension workup? Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging 2020; 2: e200603. doi: 10.1148/ryct.2020200603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jenny Louise B, Muhammad Shahid P, Ernest W, Rajan S, Ioannis V, Agnieszka C-G. Current diagnostic investigation in pulmonary hypertension. Curr Respir Med Rev 2013; 9: 79–100. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ameli-Renani S, Ramsay L, Bacon JL, Rahman F, Nair A, Smith V, et al. Dual-Energy computed tomography in the assessment of vascular and parenchymal enhancement in suspected pulmonary hypertension. J Thorac Imaging 2014; 29: 98–106. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0000000000000061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Koike H, Sueyoshi E, Sakamoto I, Uetani M. Clinical significance of late phase of lung perfusion blood volume (lung perfusion blood volume) quantified by dual-energy computed tomography in patients with pulmonary thromboembolism. J Thorac Imaging 2017; 32: 43–9. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0000000000000250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Koike H, Sueyoshi E, Sakamoto I, Uetani M, Nakata T, Maemura K. Quantification of lung perfusion blood volume (lung PBV) by dual-energy CT in patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) before and after balloon pulmonary angioplasty (BPA): preliminary results. Eur J Radiol 2016; 85: 1607–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2016.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Saeedan MB, Bullen J, Heresi GA, Rizk A, Karim W, Renapurkar RD, Morphologic RRD. Morphologic and functional dual-energy CT parameters in patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension and chronic thromboembolic disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2020; 215: 1335–41. doi: 10.2214/AJR.19.22743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tsutsumi Y, Iwano S, Okumura N, Adachi S, Abe S, Kondo T, et al. Assessment of severity in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension by quantitative parameters of dual-energy computed tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2020; 44: 578–85. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0000000000001052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Giordano J, Khung S, Duhamel A, Hossein-Foucher C, Bellèvre D, Lamblin N, et al. Lung perfusion characteristics in pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) and peripheral forms of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (pCTEPH): dual-energy CT experience in 31 patients. Eur Radiol 2017; 27: 1631–9. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4500-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hong YJ, Kim JY, Choe KO, Hur J, Lee H-J, Choi BW, et al. Different perfusion pattern between acute and chronic pulmonary thromboembolism: evaluation with two-phase dual-energy perfusion CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2013; 200: 812–7. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.8697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lu L, Xu K, Zhang LJ, Morelli J, Krazinski AW, Silverman JR, et al. Lung ischaemia-reperfusion injury in a canine model: dual-energy CT findings with pathophysiological correlation. Br J Radiol 2014; 87: 20130716. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20130716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chai X, Zhang L-J, Yeh BM, Zhao Y-E, Hu X-B, Lu G-M, , GM L. Acute and subacute dual energy CT findings of pulmonary embolism in rabbits: correlation with histopathology. Br J Radiol 2012; 85: 613–22. doi: 10.1259/bjr/67661352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bacon JL, Madden BP, Gissane C, Sayer C, Sheard S, Vlahos I. Vascular and parenchymal enhancement assessment by Dual-phase dual-energy CT in the diagnostic investigation of pulmonary hypertension. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging 2020; 2: e200009. doi: 10.1148/ryct.2020200009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Masy M, Giordano J, Petyt G, Hossein-Foucher C, Duhamel A, Kyheng M, et al. Dual-Energy CT (DECT) lung perfusion in pulmonary hypertension: concordance rate with V/Q scintigraphy in diagnosing chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH. Eur Radiol 2018; 28: 5100–10. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5467-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pansini V, Remy-Jardin M, Faivre J-B, Schmidt B, Dejardin-Bothelo A, Perez T, et al. Assessment of lobar perfusion in smokers according to the presence and severity of emphysema: preliminary experience with dual-energy CT angiography. Eur Radiol 2009; 19: 2834–43. doi: 10.1007/s00330-009-1475-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lee CW, Seo JB, Lee Y, Chae EJ, Kim N, Lee HJ, et al. A pilot trial on pulmonary emphysema quantification and perfusion mapping in a single-step using contrast-enhanced dual-energy computed tomography. Invest Radiol 2012; 47: 92–7. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e318228359a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Meinel FG, Graef A, Thieme SF, Bamberg F, Schwarz F, Sommer WH, et al. Assessing pulmonary perfusion in emphysema: automated quantification of perfused blood volume in dual-energy CtpA. Invest Radiol 2013; 48: 79–85. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3182778f07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Aoki K, Izumi Y, Watanabe W, Shimizu Y, Osada H, Honda N, et al. Generation of ventilation/perfusion ratio map in surgical patients by dual-energy CT after xenon inhalation and intravenous contrast media. J Cardiothorac Surg 2018; 13: 43. doi: 10.1186/s13019-018-0737-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Grillet F, Busse-Coté A, Calame P, Behr J, Delabrousse E, Aubry S. COVID-19 pneumonia: microvascular disease revealed on pulmonary dual-energy computed tomography angiography. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2020; 10: 1852–62. doi: 10.21037/qims-20-708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Remy-Jardin M, Duthoit L, Perez T, Felloni P, Faivre J-B, Fry S, et al. Assessment of pulmonary arterial circulation 3 months after hospitalization for SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia: dual-energy CT (DECT) angiographic study in 55 patients. EClinicalMedicine 2021; 34: 100778. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Godoy MCB, Naidich DP, Marchiori E, Assadourian B, Leidecker C, Schmidt B, et al. Basic principles and postprocessing techniques of dual-energy CT: illustrated by selected congenital abnormalities of the thorax. J Thorac Imaging 2009; 24: 152–9. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0b013e31819ca7b2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chang S, Hur J, Im DJ, Suh YJ, Hong YJ, Lee H-J, et al. Dual-energy CT-based iodine quantification for differentiating pulmonary artery sarcoma from pulmonary thromboembolism: a pilot study. Eur Radiol 2016; 26: 3162–70. doi: 10.1007/s00330-015-4140-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Willemink MJ, Persson M, Pourmorteza A, Pelc NJ, Fleischmann D. Photon-counting CT: technical principles and clinical prospects. Radiology 2018; 289: 293–312. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2018172656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Leng S, Yu Z, Halaweish A, Kappler S, Hahn K, Henning A, et al. Dose-efficient ultrahigh-resolution scan mode using a photon counting detector computed tomography system. J Med Imaging 2016; 3: 043504. doi: 10.1117/1.JMI.3.4.043504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]