Abstract

The vocational experiences and skills of young adolescents could be infused into formal education by identifying career competencies to be taught within the academic curriculum. Such curriculum practices that embed educational and career pathways must also include the perspectives of students and the community, particularly those from marginalised groups. Drawing on data from 111 teachers, principals, carers and students, this paper presents research undertaken to co-design career education lesson plans within an infused model of the curriculum for early Middle Year students from regional, rural, and remote Australia. The lesson plans and activities were designed to allow for meaningful self-reflection and goal-setting that could be seamlessly infused into the formal curriculum and help embed early-stage career education. The paper concludes by projecting opportunities and challenges for seamless curriculum integration, while pertinent to the Australian context, can also be read with broader relevance to other educational systems and schools.

Keywords: Career education; Regional, rural and remote students; Vocational identity; Middle years students; Curriculum co-design; Participatory design

Introduction

Young adolescents experience daily cognitive, physical, and social-emotional changes that can impact on the formation of their identity (McLean et al., 2010; Tanti et al., 2011). Part of their development involves reflecting on skills, capabilities, and personal characteristics that inform their vocational identity and guide their career choices (Lee et al., 2016; Patton & Portfeli, 2007). Despite these formative stages, it has been demonstrated that some young adolescents would benefit from a scaffolded, formal approach in the curriculum to assist them with navigating the complexities of career identities and to support their career exploration (Akos et al., 2011; Choi et al., 2015). Arrington (2000) suggests that vocational experiences and skills could be integrated into formal education by identifying “career competencies to be taught” (p. 104). These competencies include students’ ability to reflect on potential careers, to exhibit proactive behaviour towards career development, and networking (see Kuijpers et al., 2011). An integrated career guidance component within the curriculum can provide opportunities for young adolescents to “develop aspirations and motivation for opportunities beyond high school by encouraging students to consider seriously all choices” (Wheelock & Dorman, 1988, p. 27). Indeed, the integration of formal careers education in the curriculum is an important equity function, as marginalised student groups have been shown to particularly benefit from careers awareness and support through formal education (Doren et al., 2013; Lindstrom et al., 2019).

There is a growing awareness that some groups continue to be under-represented in higher education. For instance, scholars and policymakers have sought to increase the participation of African American, Latin, Native American, Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander communities in the United States (Jones et al., 2017); and Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic (BAME) students, particularly those from low socioeconomic backgrounds in the United Kingdom (Atherton & Mazhari, 2019). In Australia, widening participation has focussed on six equity groups that were formalised by the Australian Government in the late 1980s: people from low socioeconomic status (SES) backgrounds; regional and remote people; those from non-English speaking backgrounds; those with a disability; Indigenous people; and women in non-traditional areas, such as Engineering and Information Technology (Fray et al., 2020; Harvey et al., 2016). Increasingly, other marginalised groups are drawing policy attention, such as carers, parents, first in family students, and people from out-of-home care backgrounds (Harvey et al., 2015; Stone & O’Shea, 2019).

Debates around the role of schools in preparing students for lifelong learning as well as combating inequity systematically, highlight the importance of an embedded careers and vocational identity approach (Ben-Porath, 2013; Lüftenegger et al., 2012). Additionally, there is growing recognition of the need to embed student voice(s) in designing curriculum and creating inclusive learning environments (McLeod, 2011; Mitra, 2018). By supporting the integration of student voice(s), educational practices not only support students’ self-efficacy, confidence, and engagement, but can also better align to the needs and expectations of specific student cohorts (Mitra, 2018). Without this direct consultation and input, there remains a risk that policy development—however well-intentioned or well-informed—is paternalistic, inappropriate and/or misdirected.

This paper discusses research undertaken to co-design careers-related lesson plans for Year 7 and 8 regional, rural, and remote students in Australia. This paper argues that effective curriculum design and practices should both embed educational and career pathways and include the perspectives of students and their community. The research project draws on the perspectives and aspirations of regional communities in Australia as an illustrative example, but argues that the same principles of co-design could be applied to further explore the experiences of other marginalised groups of students. Pertinent to recent global events, the educational disparities highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic underscore the urgent need to reflect on curriculum design practices globally, to ensure that they minimise rather than reinforce existing power disparities.

Career Education in the Australian Curriculum

The past two decades in Australia have seen an improvement in school completion rates, however, youth unemployment remains high, especially in equity groups, including regional, rural, and remote communities (Cardak et al., 2017; Cooper et al., 2018). While 83% of young people living in major cities were fully engaged in employment or study, this number drops to 74% in inner regional areas and 72% in outer regional and remote areas for the total number of young people engaged or partially engaged (defined as employed part-time or studying, or part-time) (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2019). The overall cost to individuals, governments and society arising from youth who are neither employed nor in education/training (NEET) is estimated at AUD$15.9 billion every year. The social impact is equally compelling with loss of confidence, hope, and self-esteem potentially leading to mental health issues costing Australia around AUD$7.2 billion per annum (Foundation for Young Australians, 2018). Concerns about NEET rates is not unique to the Australian context, yet Australia falls behind some jurisdictions that have legislated entitlement for young people to access and enjoy a strong educational foundation and induction into post school life (Michelsen & Stenström, 2018).

Australian students usually participate in careers-related activities in the later Middle Years (Years 9 and 10), when decision-making takes place around elective subject selection for the Senior Years. As a result, the decisions made in the later Middle Years can impact senior secondary schooling (Ellerbrock et al., 2018; Trusty et al., 2005) as well as postsecondary educational and career options. Researchers strongly recommend early interventions that focus on improving students’ educational and career readiness skills to offer students an informed foundation from which to base their decision-making (Galliott & Graham, 2015; Gore et al., 2017; Rivera & Schaefer, 2009; Schaefer & Rivera, 2012).

Specifically, Fleming and Grace (2014) found that student aspirations for higher education pathways were highest during Year 7 (ages 12–13; first year secondary school). At the younger Middle Years level (Years 7 and 8), career development interventions can have a positive impact on young adolescents’ career planning and exploration (O’Brien et al., 1999; Turner & Conkel, 2010; Turner & Lapan, 2005), career decision making (Lee et al., 2016), and career knowledge (Baker, 2002). Research has shown that Middle Years students reported significant increases in levels of agency, awareness of career opportunities and confidence in their ability to explore and plan for future careers after participating in a series of interventions (see for e.g., O’Brien et al., 1999; Turner & Lapan, 2005). These activities include offering information on a variety of occupations (e.g., educational and work requirements), completing self-assessment activities (e.g., interests, efficacy beliefs), engaging in group discussions (Turner & Lapan, 2005) and activities that increase their awareness of career opportunities, teaching them how to explore careers, and conduct research on occupations (O’Brien et al., 1999).

Given the significant impact that career development interventions can have on students’ overall development, including their academic skills and knowledge acquisition, a greater emphasis should be applied to creating and delivering such interventions to students across the Middle Years (Shaefer & Rivera, 2012). Such interventions can also build academic capacity while also responding to social-personal development (Gysbers & Henderson, 2006). There are several ways that these interventions could be delivered within formal education. Watts (2011) suggests four broad models of delivery described below.

A stand-alone model, in which career education is provided as a separate subject within the curriculum;

A subsumed model, in which it is provided as part of a more broadly-based subject; for example, a common model in Britain has been to deliver career education within personal, social and health education;

An infused model, in which career education is infused into different subjects across the curriculum as a whole; and

An extra-curricular model, in which career education is provided as an additional element outside the boundaries of the formal curriculum.

Each model has merits, but many across disciplinary boundaries, have advocated for the infused model, for example within social work education (Abrams & Gibson, 2007; Cummings et al., 2006; Dyeson, 2004; Lee & Waites, 2006). The call for infusing career development into different subjects across the curriculum as a whole has had a long history, starting in the 1970s (see Akos et al., 2011; Roberts, 1983). The infusion model can be particularly effective if the larger school community is involved (e.g., through co-design) in career education programs and “if the necessary learning can take place within strongly classified and framed subject discourses” (Whitty et al., 1994, p. 174). The infusion model also aligns well to project-based learning pedagogy, as infused careers curriculum can be designed to include inquiry activities that emphasise students to find solutions and/or apply ideas they have learned (Kanter & Konstantopoulos, 2010).

More recently, the call to embed educational and career readiness across secondary education curricula is gaining traction. The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) called for the alignment of curricula to meet the environmental, economic and social challenges in modern society (OECD, 2018). In the United States (US), federal policies have encouraged states to implement career readiness immersed curriculum across the school sector, with the intention to prepare students for colleges and 21st-century careers. The most recent iteration of the US standards-based reform movement has produced college-and career-readiness (CCR) standards intended to prepare students to build capacity for successful postsecondary opportunities (Pak et al., 2020).

In Australia, the need for a unifying career development framework was identified by the Youth Action Plan Taskforce in its report, Footprints to the Future (Eldridge, 2001), which found that the career and transition services were inconsistent in quality and availability nationally. As a result, the Australian Blueprint for Career Development was developed in 2003, using the Canadian Blueprint for Life/Work Designs as its starting point (Ministerial Council for Education, Early Childhood Development and Youth Affairs [MCEECDYA], 2010). The Blueprint has been in place nationally since 2008 and provides a framework for designing, implementing and evaluating career development programs that identifies the skills, attitudes and knowledge that individuals need to make sound choices and to effectively manage their careers (MCEECDYA, 2010). While the framework is aligned to the Australian Curriculum, it is a standalone framework rather than an integrated component. Four years after its implementation, a review of the Blueprint found that “the placement of career development competencies within a curriculum framework provides the greatest potential to impact the competency development of all students” (Atelier Learning Solutions, 2012, p. 48). Additionally, teachers have been identified as best placed to deliver careers activities (Welde et al., 2015), supporting the long-standing view of embedding careers education in the curriculum. Given the marked socioeconomic divide in the type and quality of career information available to students (Dockery et al., 2021) researchers have advocated for a whole school approach to “embed career education and development in curriculum/co-curriculum, beginning with exploratory activities in primary school and linking these to further exploration, reflection and adaptive goal setting in later years” (Keele et al., 2020, p. 57) and developing a “curriculum that explicitly teaches students the ‘hidden’ discourses to navigate the world of work” (Austin et al., 2021, p. 6).

Curriculum reforms in Victoria

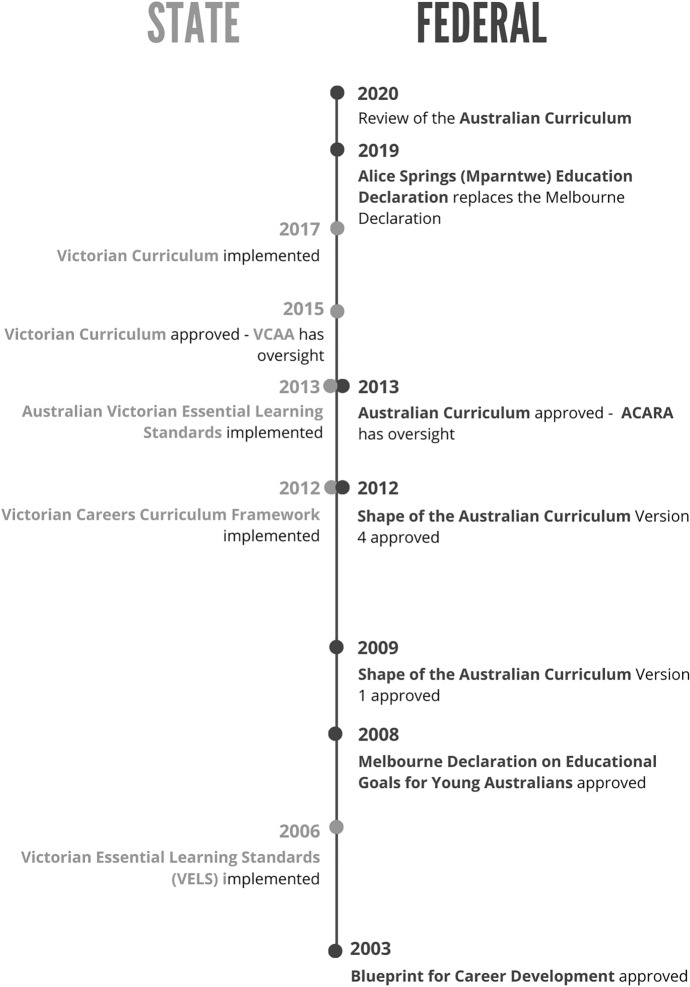

Any national reforms in federal systems, such as Australia, in which power is split between federal (national) and state (sub-national) governments create challenges. In Australia, whilst there are strong arguments for national consistency on the grounds of equity, effectiveness and efficiency (Keating, 2009), reform is complicated because the state and territory governments retain constitutional responsibility for schooling. A summary of curriculum reforms at Federal and state-level of Victoria is summarised in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Overview of Australian and Victorian curriculum reforms. By M. Mahat. Copyright 2020 by M.Mahat

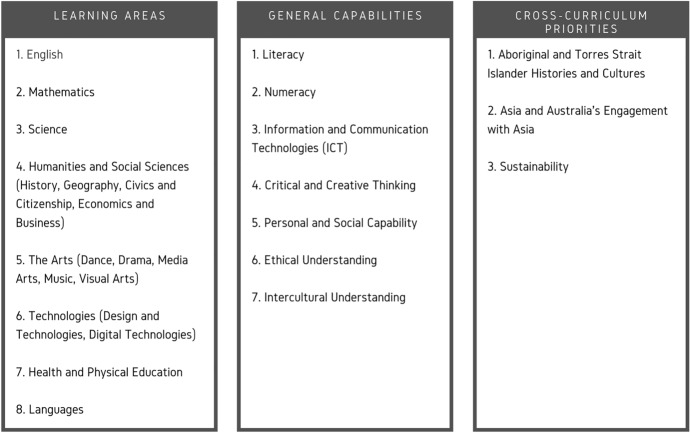

The Australian Curriculum is presented as a progression of learning from Foundation to Year 10. It is organised within a ‘three-dimensional’ structure, encompassing: eight traditional disciplinary key learning areas, seven general capabilities (also referred to as essential skills for the twenty-first century), and three cross-curriculum priorities (CCPs). Figure 2 provides a summary of the Australian Curriculum structure. In Years 7–10, the Australian Curriculum is purportedly designed to equip students for senior secondary schooling, including vocational pathways (Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Agency [ACARA], 2020) but there are no clear standards nor guidance on how this is incorporated.

Fig. 2.

The three-dimensional structure of the Australian Curriculum

Although the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Agency (ACARA) has assumed unprecedented policy development roles, mediating state and federal relations through novel processes of negotiation (Savage, 2016), responsibility for the implementation of the Australian Curriculum remains with each of the six states and two territories of Australia. Within this state-based system, compliance responsibilities vary among independent and religious schools, which adds another layer of complexity to the implementation of a national approach across both public and independent sectors. In the state of Victoria, the latest iteration of the Victorian Curriculum incorporates the Australian Curriculum but is formatted as a continuum of learning along four key principles (VCAA, 2015): (1) the learning areas or disciplines that are the cornerstone of the curriculum; (2) the general capabilities that require explicit attention in the development of teaching and learning programs; (3) the curriculum as a developmental learning continuum rather than a series of distinct learning blocks; and (4) the content of the curriculum (the ‘what’) that is mandated through the learning areas and the capabilities. The provision of the curriculum (the ‘how’), remains a responsibility for local schools and their communities.

The Victorian Careers Curriculum Framework (VCCF), separate from the Victorian Curriculum, provides a scaffolded model for a career education that helps prepare young people to transition successfully into further education, training, or employment. The VCCF is based on the 11 competencies identified in the Australian Blueprint for Career Development (mentioned earlier), with the learning outcomes focussed on the three Stages of Career Development: Self-Development, Career Exploration and Career Management. Learning outcomes are developed for students in specific year levels (Years 7 to 12) as well as students enrolled via institutions providing Vocational Education and Training (VET) and Adult and Community Education (ACE). The focus of these learning outcomes is to provide opportunities for young people to build their career skills, knowledge and capabilities. The framework learning outcomes are also structured around the six steps to a young person’s acquisition of skills and knowledge for lifelong career self-management. Students are encouraged to complete all six steps—Discover, Explore, Focus, Plan, Decide, and Apply—with a focus on a different step each year (DEECD, 2012). As an example, the learning outcomes for Year 7 students are summarised in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Victorian careers curriculum framework, learning outcomes for year 7. Copyright 2012 by DEECD

Adapted from Aligning the Australian curriculum with the Victorian careers curriculum framework by Department of Education and Early Childhood Development [DEECD]

There is some attempt to integrate the VCCF into the Victorian Curriculum, and hence align it to the Australian Curriculum. This integration is done at the level of linking the Australian (and Victorian) Curriculum’s ‘general capabilities’ and the VCCF’s ‘learning outcomes’. The objective of this alignment is so that students are on their way to achieving the essential skills required for the twenty-first century (DEECD, 2012). Schools are encouraged to build on and contextualise the alignment between the Australian Curriculum and the VCCF to meet the needs of their unique learner cohort and school priorities (DEECD, 2012).

There are a number of emerging career education reforms in both Victoria and nationally, with increasing recognition that not enough is being done to support students to identify, explore, and pursue careers. Nationally, Future Ready is a student-focussed strategy, emphasising on improving career education in schools by building teacher and school leader capability; supporting parents and carers to have career conversations; and encouraging collaboration between industry and schools (Department of Education & Training, 2019). Despite this national strategy, a recent review by the Department of Education, Skills and Employment (2020) argues that more needs to be done to prepare young people “for purposeful engagement with the labour market” (p. 12) and that general “capabilities should be specifically discussed as part of a pathways conversation between teachers and students from Year 9” (p. 40).

In Victoria, the Firth review of the Victorian Certificate of Applied Learning (VCAL) found that a vocational specialist pathway should be integrated in the VCE, rather than a stand-alone qualification (Department of Education & Training, 2020). The review further recommended that this can be achieved through improving the capability of teachers and reducing operational and administrative burdens on schools (Department of Education & Training, 2020). Furthermore, the Victorian Department of Education and Training has enlisted VCAA to create careers education resources that are linked to the Victorian Curriculum that will be distributed to teachers across the state. Other resources in development include Career Self-Exploration Workshops, Career Planning Service, and the Careers e-Portfolio (Parliament of Victoria, 2019). It is important to note here that these resources will be freely accessible to all Victorian schools, however there is no mandate to utilise and incorporate them within the curriculum. Other initiatives include the expansion of Managed Individual Pathways (MIPs) into the new Career Education Funding (CEF) which will provide for course and career counselling and completion of career action plans; activities which again, sit outside of the formal curriculum (Parliament of Victoria, 2019).

In amongst these reforms, the government has acknowledged that there is an urgent need to address the career development needs of students in regional areas, and students experiencing disadvantage. Specifically, the government has highlighted the importance of understanding students’ interests, strengths and aspirations, students’ ability to explore how jobs and careers are changing, what work looks and feels like, and the range of opportunities available to them, and students’ ability to identify the subjects and qualifications that suit them best and which reflect industry needs (Parliament of Victoria, 2019).

Methods

A case study approach involving multiple cases (i.e., schools) was used (Yin, 2017), combining two qualitative data collection methods: participatory design workshops and semi-structured interviews. Participatory design workshops were used as an approach to increase the quality of findings, address ethical concerns of participants, improve implementation (Elberse et al., 2011), as well rectify long-term power imbalances and safeguard against future unethical or detrimental research methods (Hamington, 2019). Participatory design workshops were approximately one hour in length, conducted at the school site, and included a range of activities that allowed for school staff (i.e., teachers, career counsellors, and principals), students, and carers to share their ideas and experiences that would later inform the design of learning activities (see Table 2 for an overview of participants). Each participant group (i.e., student, school staff, and carer) had their own workshop, as activities varied depending on the group. For example, students were asked to reflect on what careers they knew of and what educational qualifications or attributes they believed were necessary for each. Alternatively, teachers were asked to brainstorm what types of learning activities would be useful to support students’ career development. Activities that were included in the workshops spanned from role-playing, voting exercises, mind maps, and storyboarding (Dollinger et al., 2020, for a full overview of the workshops). At each of the workshops, at least two members of the research team were present to collect the artefacts (e.g., worksheets) as well as take observational notes.

Table 2.

Workshop participant overview

| School | Year 7 and 8 students (n) | Carers (n) | Educators (n) | Total (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| School 1 | 31 | 0 | 6 | 37 |

| School 2 | 16 | 4 | 4 | 24 |

| School 3 | 11 | 1 | 17 | 29 |

| School 4 | 8 | 0 | 3 | 11 |

| Total | 66 | 5 | 30 | 101 |

The focus of the semi-structured interviews was to explore principals’ perceptions of how to support early-stage student awareness and development towards higher education pathways and careers. To encourage participants to elaborate on questions and experiences, the interviews were undertaken online and designed in a semi-structured way and conducted conversationally, so participants could freely explore any themes they felt were relevant or of interest to them (Marshall & Rossman, 1989; Seidman, 2006).

Participants

All 14 schools which participated in the study were classified as ‘outer-regional’, or ‘very remote’ by the Australian Statistical Geography Standards (ASGS). The selection process also sought to include schools from low socioeconomic communities by adopting the Index of Community Socio-Educational Advantage (ICSEA) to determine which schools were below the national mean value of 1000. Participating schools had at least ten students per year level, to ensure sufficient participation for the student workshops. The school characteristics are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participating school characteristics

| School | State | Size of School | ICSEA | ASGS | Distance to nearest regional centre (km) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| School 1 | Victoria | 252 (P-12) | 959 | Outer regional | 74 |

| School 2 | Victoria | 179 (P-12) | 982 | Outer regional | 114 |

| School 3 | Victoria | 170 (P-12) | 975 | Outer regional | 48 |

| School 4 | Victoria | 122 (7–12) | 905 | Outer regional | 94 |

| School 5 | Victoria | 252 (P-12) | 959 | Outer regional | 75 |

| School 6 | Victoria | 179 (P-12) | 982 | Outer regional | 114 |

| School 7 | Victoria | 170 (P-12) | 975 | Outer regional | 48 |

| School 8 | Victoria | 122 (7–12) | 905 | Outer regional | 94 |

| School 9 | Victoria | 544 (7–12) | 938 | Outer regional | 14 |

| School 10 | Queensland | 200 (7–12) | 960 | Very remote | 687 |

| School 11 | Queensland | 157 (7–12) | 958 | Outer regional | 210 |

| School 12 | Queensland | 42 (P-10) | 903 | Very remote | 439 |

| School 13 | Queensland | 232 (7–12) | 915 | Very remote | 617 |

| School 14 | Queensland | 79 (P-10) | 927 | Very remote | 603 |

ASGS refers to the Australian Statistical Geography Standards and ICSEA refers to the Index of Community Socio-Educational Advantage

The data collection for the study occurred on the eve of the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result of travel restrictions to other states of Australia, only four schools (Schools 1 to 4) from outer-regional Victoria, Australia (Victorian Department of Education and Training ethics reference: 2019_004214; La Trobe University Human Ethics Committee HEC19370), were involved in the participatory design workshops. Participants consisted of Year 7 and Year 8 students, their carers (e.g. parents, guardians), and school staff (e.g. teachers, principals). A total of 101 participants (see Table 2) participated in a series of participatory design workshops aimed to ascertain participants’ understanding(s) and recommendations for pathways and career curriculum. In all of these activities, the intended goal was not only to collect data from participants but to help participants reflect on their own experiences (Dollinger et al., 2020).

The second component of the study involved semi-structured interviews with ten school principals in Queensland (Queensland Department of Education ethics reference: 550/27/2278) and Victoria (Schools 5 to 14). Originally the research team was planning to visit these schools to conduct co-design workshops, but new arrangements were made due to restrictions resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. The study produced data such as observation notes, participants’ commentaries, artefacts such as mind maps or drawings, and interview data which were audio recorded and transcribed. Bazeley’s (2009) three-step approach of describe, compare and relate, was used to analyse the data. All data were coded by at least two members of the research team to ensure reliability. The findings shown below represent the key common themes which arose from the multi-site case study approach.

Findings

Findings of the study yielded several significant and relevant results, including varying perceptions of barriers to postsecondary education by participant groups, information gaps on what life at university was like, and suggestions for more community-driven and locally-specific careers events and interventions (Dollinger et al., 2020).

This paper will focus explicitly on findings that later informed the development of lesson plans. These findings are organised by themes and include 1) simple, easy-to-teach, engaging activities; 2) a positive narrative about regional employment options; and 3) differentiating between postsecondary options. While the themes were derived from data triangulated from the co-design workshops and interviews, the quotes provided here have been explicated from interviews with principals (P1–P10).

Simple, easy-to-teach, engaging activities

The first finding arose from workshops and interviews with teachers and principals about the difficulty of including more content in what was already considered to be a very ‘crowded’ curriculum. While the majority of participants indicated sentiments that careers curriculum needed to have a more prominent role in Year 7 and Year 8, they also discussed the existing pressures to teach a wide range of topics. One suggestion from many participants was that lesson plans should be simple, take very little preparation time, and be focussed on student reflection and engagement. As one principal recommended, “The learning activities would be good if it was short and sharp, something that could be delivered every Monday or Tuesday… it has to be really specific and something that’s very rapid fire” (P4).

Participants also recommended that lesson plans be centred around the students’ own development and allow them to reflect on their capabilities and goals. As one participant noted, “For our students [what would work] is to consider the things that they value, the things that they enjoy, thinking about themselves as learners and ways in which they learn best.” (P3).

Suggestions and ideas from participants also included embedding activities in the lessons plans that were “hands on, tactile type activities…” (P5). When possible, it was also suggested that lesson plans allow for students to consider or reflect what was happening around them in their own lives and perhaps even participate in local career visits. For example, one participant suggested, “Don’t just say this is what a goat’s dairy looks like, take them to a goat’s dairy and say this is how it operates” (P10).

Positive narrative about regional employment options

The second theme of participant-led suggestions was around the importance that lesson plans communicated a positive narrative about regional life and/or regional employment options. There was a concern, especially among carers (e.g., parents, guardians), that careers education often assumed that students would need to move to urban areas to participate in ‘jobs of the future’. In one of the carers’ co-design workshops, carers discussed the importance of debunking the myth that regional areas offered no employment opportunities. They pointed out that students could study online or at a local Technical and Further Education (TAFE) institution or university to stay closer to home and that many jobs were becoming location independent. They also voiced their perceptions that teachers in urban areas or large postsecondary schools may not care about students as much, and that regional study and work options might allow for students to have more care and support within a community. Participants also felt that the city-centric narrative around careers and postsecondary options were discouraging regional, rural, and remote students who preferred to stay in their local communities. As one participant noted, “Believe it or not, many of our kids don’t like [city] life. We’ve got four students who went to university [a couple years ago] and they came back… it’s not just where they wanted to be” (P7).

As a solution, participants felt that lesson plans should positively highlight the job opportunities for students in their local areas. Some suggestions from participants included conservation work, police or legal jobs and graphic design or freelance jobs. As one participant suggested, “What have we got in our own backyard? …You know, we have a factory up the road here and there’s some terrific career pathways that could be engaged in out there…” (P8).

Differentiating between postsecondary options

Finally, the third theme to arise linked to a need for lesson plans to help students differentiate between various postsecondary options. In the workshops with students, the majority of students were unsure and confused of the options that were available to them after Year 12, and the differences between VET and university. This is particularly important because students currently need to choose their Victorian Certificate of Education (VCE) or Victorian Certificate of Applied Learning (VCAL) pathways in Year 9, so having a basic understanding of the differences and how they may/may not support career goals can help students make an informed decision. One such principal summarised this sentiment as:

A lot of the Year 9s are choosing subjects because their mates are choosing them. So, that’s why I’m thinking that the earlier we get in, the seeds that we’re sowing, by the time they get to Year 9, hopefully they’re able then, to make those informed decisions rather than at spur of the moment, my mate’s doing this. (P4)

Participants agreed that lessons plans should also help ‘plant the seed’ about postsecondary options. Given that costs were a commonly cited barrier among carers and students, many teachers and principals felt that the far more affordable VET pathways should be promoted more widely to students. One principal spoke of their own story of trying to promote TAFE options:

One of the things I’ve worked on is to create a positive perception of TAFE because it is such a fantastic alternative for kids. We’ve really seen our TAFE numbers rise just with some different messaging and TAFE itself has rebranded itself more broadly as well. (P3)

Development of learning activities

Through the workshops and interviews, participants shared with the research team their ideas and experiences on how the subsequent lesson plans could be designed. The research further drew upon strands and sub-strands of the Australian Curriculum that could be enhanced by career-related learning activities. In addition, the Victorian Careers Curriculum Framework was consulted to ensure accordance with the lesson plans. The lesson plans and their learning activities were then designed by the research team to reflect principles of the Victorian Teaching and Learning Model (VTLM) (State Government of Victoria, 2019a) and the Practice Principles for Excellence in Teaching and Learning (PPLT) (State Government of Victoria, 2019b), which are key pedagogical concepts familiar to Victorian teachers. To craft the lesson procedure, the Teaching and Learning Cycle (TLC) model (State Government of Victoria, 2019c) was utilised as it is a common approach used in teachers’ lesson planning.

In addition to the framework requirements above, many factors were taken into account during the design of the lesson plans and learning activities. Considerations were taken to include students’ ability to explore how jobs and careers are changing, what work looks and feels like, and the range of opportunities available to them, and to identify the subjects and qualifications that suit them best and which reflect industry needs (Parliament of Victoria, 2019).Their applicability to regional careers was an essential component which needed to be balanced with projections of future regional job growth and new sectors emerging in these communities. For instance, activities included examining the changing technological nature of farming as well as exploring heritage management and aged care. It was essential that the careers and pathways presented to the students expanded on their knowledge (e.g. farming), but also exposed them to avenues that may be foreign to them (e.g. robotics/ ‘agbots’). It was important that students become acquainted with vocabulary that will be important to know in the years ahead, such as Australian Tertiary Admission Rank (ATAR), qualification, bachelor’s degree and TAFE, thus reciprocal reading strategies were included to facilitate comprehension of these key terms. Participants in the workshops and interviews were particularly concerned with students having an opportunity to reflect on their own skills and interests in light of any careers-related learning. Therefore, lesson plans embrace a ‘whole-of-person’ approach, and give students opportunities to think about the applicability of certain careers to their community and their own goals.

In practical terms, the lesson plans were formatted to provide teachers with the necessary information at a glance (Fig. 4). The relevant part of the Australian Curriculum and Victorian Careers Curriculum Framework are clearly noted as well as any logistical requirements such as IT access and photocopying. A Scootle code provides the digital code for a compendium of digital resources in the national repository that is aligned to the Australian Curriculum (Education Services Australia, 2020). As recommended by the regional, rural, and remote participants, most activities could be implemented without internet access, which is often an issue in these communities (Hay & Eagle, 2021). Additionally, while the learning activities align to an infused model (linking to the curriculum topics) they were also designed to be stand-alone if needed. This design consideration was also suggested through our interviews with principals, who noted that many teachers are already burdened and time-poor (also see McCallum & Price, 2010), and activities that could be easily integrated when free time unexpectedly arose, would be ideal. Each lesson aims to address simultaneously the specific disciplinary knowledge of Learning Areas while also exploring careers-related content by widening students' understanding of what jobs are available (both in cities and in regional and rural locations) and what school/education is typically needed for these jobs.

Fig. 4.

A sample lesson plan (Dollinger et al., forthcoming )

Discussion

The empirical contribution of this paper is the three main themes identified in the perspectives of regional communities to inform curriculum design and practices. The first theme, the need for simple, easy to teach career activities links to ongoing research that discussed how to balance what some scholars have described as a crowded curriculum (Keele et al., 2020). Wyn (2007), speaking on health and wellbeing, however, argues that non-core curriculum topics are marginalised not because of available time, but because of they are not valued within policy frameworks. Therefore, by taking an infused curriculum approach, whereby topics such as careers and wellbeing are aligned and embedded to existing topics, the important lessons may be given more equal emphasis, with the ability for students to find solutions and apply key ideas (Kanter & Konstantopoulos, 2010).

The second theme, the need for positive narratives about regional employment opportunities, speaks to growing research that there needs to be more targeted regional-focussed policy engagement (Herbert, 2020). This is also consistent with the view that students should have the ability to explore how jobs and careers are changing, what work looks and feels like, and the range of opportunities available to them (Parliament of Victoria, 2019). Participants expressed concerns about the lack of visibility of their communities and ways of life—about their fears for the futures of their communities if school leavers had to move away for further vocational or higher education and fears for the wellbeing, care and support available for those school leavers who move to metropolitan areas. This concern would not be easily articulated to policy makers without the participation of these communities in this study. It also suggests a tension between the national priorities identified and expressed in national curricula, and the flexibility required to adapt these priorities to local wants, needs and resources.

Finally, the third theme, the need for better differentiation between postsecondary options, suggests a relatively simple information deficit among students, which may be addressed through the clear provision of information and engaging activities. This finding is consistent with the view students’ need to have the ability to identify the subjects and qualifications that suit them best and which reflect industry needs (Parliament of Victoria, 2019). It also speaks to the importance of utilising participatory design, or co-design, towards careers education, as uncovering participants’ gaps or preferred solutions can be addressed through straightforward consultation (Elberse et al., 2011; Hamington, 2019).

While the current Australian Curriculum offers select career guidance, it often assumes that careers advice is homogenous across student cohorts and contexts (such as metropolitan vs. regional). The lesson plans were therefore developed to try and mitigate these differences by including informative activities including the changing nature of regional employment in traditional regional industries (e.g., automation in the agricultural sector), introduce students to growth and emerging industries as well as expose students to a number of career paths they may not have considered simply because they had no knowledge of these careers existing. Moreover, the lesson plans were also designed to allow for meaningful self-reflection and goal setting. These activities are infused into the existing Australian and Victorian Curriculum and the Victorian Careers Curriculum Framework to showcase user suggested topics and activities that can help embed early-stage career education.

An embedded model, in which career development interventions are embbeded into different subjects across the curriculum as a whole, while simple in principle (Watts, 2011), has some interesting challenges. There can be difficulties in infusing careers themes or ‘horizontal discourse’ into subjects or ‘vertical discourse’ and based on different ‘recognition rules’ (Whitty et al., 1994) of what teachers and students regard as legitimate discourse within particular lessons. Implementation of such an infused model can also often be patchy, disconnected and invisible to the student (OECD, 2004). An infusion model requires a high level of co-ordination and support to be effective. Provisions need to be made, on one hand, to help students make personal sense of their career and educational development, and on the other hand, to help teachers in managing a potentially higher workload.

By extending the notion of working with the school community from the objects of research to ‘co-producers’ (Abebe, 2009) of career-infused curriculum, the findings of the study and resulting lesson plans have shown that an infused model is possible and a worthwhile cause. The infused model allows students to “synthesise learning from a range of different subjects and apply this to life beyond school” (Whitty et al., 1994, p. 174). Assessment and accreditation can legitimise career education as a worthwhile and rigorous activity, motivating students, increasing its credibility in the eyes of teaching staff, and making it easier to secure curriculum time and other resources (Watts, 2011). Finding forms of broad and flexible assessment which are congruent with the aims of career education and which support the learning process: assessment for learning as well as assessment of learning (Watts, 2011) can help identify and value the knowledge and competencies students have acquired, and to explore new opportunities to which they might be transferable.

Conclusion and implications

It is not sufficient to assume students can navigate the complexities of career learning without scaffolded curriculum interventions that can support career exploration experiences, provide foundations for identity formation, and build self-assessment or self-reflection skills necessary for vocational success. The role of schools is to ensure students have equal access to careers education and support (Ben-Porath, 2013; Lüftenegger et al., 2012), and in particular, early access during Middle Years that can help guide students before they make key decisions that may impact their future (e.g., attending high school, choosing postsecondary degree type) (Gore et al., 2015, 2017). However, additional to this responsibility is the added necessity to ensure that the curriculum reflects the communities in which it serves, in this instance, regional, rural, and remote communities. In fact, the need for differentiated curriculum and interventions, that are tailored to specific cohorts may play a critical role in driving buy-in and engagement, and ultimately, success of such initiatives (Guenther, 2013). Previous research has already highlighted the relatively poor employment outcomes for school-leavers from regional, rural, and remote communities, (ABS, 2019; Curtain, 2001) pointing to a need to create more nuanced, context-specific solutions (Dollinger et al., 2020).

Although this case study focusses on regional communities in Australia, the findings regarding community concerns about the lack of visibility and community strength and wellbeing, may well apply to many marginalised groups around the world. Without direct consultation and input, there remains a risk that policy development remains paternalistic, inappropriate and misdirected. The importance of ensuring that voices of marginalised students’ groups and communities are considered during the development of curriculum policies and activities remains critical to ensure that existing power disparities are reduced.

Acknowledgements

This project was funded the National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education (NCSEHE), Australia.

Biographies

Marian Mahat

is a Senior Research Fellow at the University of Melbourne. Her research focuses on learning environments with an emphasis on co-designing curriculum and pedagogy, teacher-led inquiry and teachers professional development.

Mollie Dollinger

is Equity-First, Students as Partners Lecturer at Deakin University. Her research areas include student and staff partnership (co-creation), student equity, learning analytics, higher education policy, and work-integrated learning.

Belinda D’Angelo

is an Associate Lecturer in Enabling Education at La Trobe University. She previously worked as a Middle Years school teacher throughout Victoria. Her research interests include improving student access and equity, participatory design methodology, and learning design.

Ryan Naylor

is Associate Professor (Education) in the Sydney School of Health Sciences. His current research focuses primarily on understanding and addressing barriers to success in higher education. He has published widely on issues of access to higher education, equity interventions and their evaluation, and the experiences and expectations of students.

Andrew Harvey

is Professor and Director of the Centre for Higher Education Equity and Diversity Research at La Trobe University. He has published widely in areas of higher education policy, including student equity, admissions, retention, and globalisation.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education (NCSEHE), Australia.

Data availability

Upon request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All the authors declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Marian Mahat, Email: marian.mahat@unimelb.edu.au.

Mollie Dollinger, Email: mollie.dollinger@deakin.edu.au.

Belinda D’Angelo, Email: b.dangelo@latrobe.edu.au.

Ryan Naylor, Email: ryan.naylor@sydney.edu.au.

Andrew Harvey, Email: andrew.harvey@latrobe.edu.au.

References

- Abebe T. Multiple methods, complex dilemmas: Negotiating socio-ethical spaces in participatory research with disadvantaged children. Children’s Geographies. 2009;7(4):451–465. doi: 10.1080/14733280903234519. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abrams LS, Gibson P. Reframing multicultural education: Teaching white privilege in the social work curriculum. Journal of Social Work Education. 2007;43(1):147–160. doi: 10.5175/JSWE.2007.200500529. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akos P, Charles P, Orthner D, Cooley V. Teacher perspectives on career-relevant curriculum in middle school. RMLE Online. 2011;34(5):1–9. doi: 10.1080/19404476.2011.11462078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arrington K. Middle grades career planning programs. Journal of Career Development. 2000;27(2):103–109. doi: 10.1023/A:1007896516872. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atelier Learning Solutions. (2012). Report of the review of the Australian Blueprint for Career Development. Retrieved from https://www.dese.gov.au/school-work-transitions/resources/blueprint-review-report-november-2012

- Atherton, G., & Mazhari, T. (2019). Working Class Heroes – Understanding access to higher education for white students from lower socio-economic backgrounds: A National Education Opportunities Network (NEON) report, UK. Retrieved from https://www.educationopportunities.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/Working-Class-Heroes-Understanding-access-to-Higher-Education-for-white-students-from-lower-socio-economic-backgrounds.pdf

- Austin, K., O’Shea, S., Groves, O., & Lamanna, J. (2021). Best-practice principles for career development learning for students from low socioeconomic (LSES) backgrounds. University of Wollongong and National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education, Australia.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2019). Education and work: 2019 (cat. no. 6227.0). Retrieved from https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/6227.0May%202019?OpenDocument

- Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. (2020). Learning 7–10. Retrieved from https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/learning-7-10/

- Baker HE. Reducing adolescent career indecision: The ASVAB career exploration program. Career Development Quarterly. 2002;50(4):359–370. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-0045.2002.tb00584.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bazeley P. Analysing qualitative data: More than ‘identifying themes’. Malaysian Journal of Qualitative Research. 2009;2(2):6–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Porath S. Deferring virtue: The new management of students and the civic role of schools. Theory and Research in Education. 2013;11(2):111–128. doi: 10.1177/1477878513485172. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cardak, B., Brett, M., Bowden, M., Vecci, J., Barry, P., Bahtsevanoglou, J., & McAllister, R. (2017). Regional Student Participation and Migration: Analysis of Factors influencing Regional Student Participation and Internal Migration in Australian Higher Education. National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education. Retrieved from https://www.ncsehe.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Regional-Student-Participation-and-Migration-20170227-Final.pdf

- Choi Y, Kim J, Kim S. Career development and school success in adolescents: The role of career interventions. The Career Development Quarterly. 2015;63(2):171–186. doi: 10.1002/cdq.12012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper G, Strathdee R, Baglin J. Examining geography as a predictor of students’ university intentions: A logistic regression analysis. Rural Society. 2018;27(2):83–93. doi: 10.1080/10371656.2018.1472909. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings SM, Cassie KM, Galambos C, Wilson E. Impact of an infusion model on social work students’ aging knowledge, attitudes, and interests. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2006;47(3/4):173–186. doi: 10.1300/J083v47n03_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtain, R. (2001). How young people are faring. Key Indicators 2001. Retrieved from http://dusseldorp.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2001/11/hypaf_oct2001.pdf

- Department of Education and Early Childhood Development. (2012). Aligning the Australian curriculum with the Victorian careers curriculum framework. Retrieved from https://www.education.vic.gov.au/Documents/school/teachers/teachingresources/careers/carframe/auscurricmapping.pdf

- Department of Education and Training. (2019). Future ready. A student focused national career education strategy. Retrieved from https://schooltowork.dese.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-07/future_ready_a_student_focused_national_career_education_strategy.pdf

- Department of Education and Training. (2020). Review into vocational and applied learning pathways in senior secondary school: Final Report. Retrieved from https://www.education.vic.gov.au/Documents/about/department/vocational-applied-learning-pathways-report.pdf

- Department of Education, Skills and Employment. (2020). Looking to the future: Report of the review of senior secondary pathways into work, further education and training. Retrieved from https://www.dese.gov.au/quality-schools-package/resources/looking-future-report-review-senior-secondary-pathways-work-further-education-and-training

- Dockery AM, Bawa S, Coffey J, Li IW. Secondary students’ access to careers information: The role of socio-economic background. The Australian Educational Researcher. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s13384-021-00469-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dollinger, M., D’Angelo, B., Naylor, R., Harvey, A., & Mahat, M. (2020). Participatory design for community-based research: A study on regional student higher education pathways. The Australian Educational Researcher, 48(4), 739–755. 10.1007/s13384-020-00417-5

- Dollinger, M., Harvey, A., Mahat, M., Naylor, R. & D'Angelo, B. (Forthcoming). Careers Exploration for Country Kids: 10 Learning Activities for Middle Years Students to Kickstart Career Planning. National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education, Curtin University.

- Doren B, Lombardi AR, Clark J, Lindstrom L. Addressing career barriers for high risk adolescent girls: The PATHS curriculum intervention. Journal of Adolescence. 2013;36(6):1083–1092. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyeson TB. Cultural diversity and populations at risk: Social work education and practice. Social Work Perspective. 2004;17(1):45–47. [Google Scholar]

- Education Services Australia. (2020). Scootle. Retrieved from https://www.scootle.edu.au/

- Elberse JE, Caron-Flinterman JF, Broerse JE. Patient–expert partnerships in research: How to stimulate inclusion of patient perspectives. Health Expectations. 2011;14(3):225–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2010.00647.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldridge, D. (2001). Footprints to the future: Report from the prime minister's youth pathways action plan taskforce. Department of Education and Training.

- Ellerbrock CR, Main K, Falbe KN, Pomykal Franz D. An examination of middle school organizational structures in the United States and Australia. Education Sciences. 2018;8(4):168. doi: 10.3390/educsci8040168. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming MJ, Grace DM. Increasing participation of rural and regional students in higher education. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management. 2014;36(5):483–495. doi: 10.1080/1360080X.2014.936089. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foundation for Young Australians. (2018). The new work reality. Retrieved from https://www.fya.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/FYA_TheNewWorkReality_sml.pdf

- Fray L, Gore J, Harris J, North B. Key influences on aspirations for higher education of Australian school students in regional and remote locations: A scoping review of empirical research, 1991–2016. The Australian Educational Researcher. 2020;47(1):61–93. doi: 10.1007/s13384-019-00332-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galliott NY, Graham LJ. School based experiences as contributors to career decision-making: Findings from a cross-sectional survey of high-school students. The Australian Educational Researcher. 2015;42(2):179–199. doi: 10.1007/s13384-015-0175-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gore J, Holmes K, Smith M, Fray L, McElduff P, Weaver N, Wallington C. Unpacking the career aspirations of Australian school students: Towards an evidence base for university equity initiatives in schools. Higher Education Research & Development. 2017;36(7):1383–1400. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2017.1325847. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gore J, Holmes K, Smith M, Southgate E, Albright J. Socioeconomic status and the career aspirations of Australian school students: Testing enduring assumptions. The Australian Educational Researcher. 2015;42(2):155–177. doi: 10.1007/s13384-015-0172-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guenther J. Are we making education count in remote Australian communities or just counting education? The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education. 2013;42(2):157–170. doi: 10.1017/jie.2013.23. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gysbers, N. C., & Henderson, P. (2006). Developing and managing your school guidance and counseling program (4th ed.). American Counselling Association.

- Hamington M. Integrating care ethics and design thinking. Journal of Business Ethics. 2019;155(1):91–103. doi: 10.1007/s10551-017-3522-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey A, Andrewartha L, McNamara P. A forgotten cohort? Including people from out-of-home care in Australian higher education policy. Australian Journal of Education. 2015;59(2):182–195. doi: 10.1177/0004944115587529. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, A., Burnheim, C., & Brett, M. (2016). Towards a fairer chance for all: Revising the Australian student equity framework. In A. Harvey, A. Burnheim, & C. Brett (Eds.), Student equity in Australian higher education (pp. 3–20). Springer.

- Hay, R., & Eagle, L. (2021). Marketing social change: Fixing bush internet in rural, regional, and remote Australia. In R. Hay, L. Eagle, & A. Bhati (Eds.), Broadening cultural horizons in social marketing (pp. 281–293). Springer.

- Herbert A. Contextualising policy enactment in regional, rural and remote Australian schools: A review of the literature. Australian and International Journal of Rural Education. 2020;30(1):64–81. doi: 10.3316/informit.060165882819180. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, T., Jones, S. M., Elliott, K. C., Owens, L. R., Assalone, A. E., & Gándara, D. (2017). Outcomes based funding and race in higher education: Can equity be bought? Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kanter DE, Konstantopoulos S. The impact of a project-based science curriculum on minority student achievement, attitudes, and careers: The effects of teacher content and pedagogical content knowledge and inquiry-based practices. Science Education. 2010;94(5):855–887. doi: 10.1002/sce.20391. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keating, M. (2009). Social citizenship, devolution and policy divergence. In S. L. Greer (Ed.), Devolution and social citizenship in the UK (pp. 97–116). Policy Press.

- Keele SM, Swann R, Davie-Smythe A. Identifying best practice in career education and development in Australian secondary schools. Australian Journal of Career Development. 2020;29(1):54–66. doi: 10.1177/1038416219886116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuijpers MACT, Meijers F, Gundy C. The relationship between learning environment and career competencies of students in vocational education. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2011;78(1):21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2010.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B, Porfeli EJ, Hirschi A. Between-and within-person level motivational precursors associated with career exploration. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2016;92:125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2015.11.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E-KO, Waites CE. Special section: Innovations in gerontological social work education infusing aging content across the curriculum: Innovations in baccalaureate social work education. Journal of Social Work Education. 2006;42(1):49–66. doi: 10.5175/JSWE.2006.042110002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom L, Hirano KA, Ingram A, DeGarmo DS, Post C. “Learning to Be Myself”: Paths 2 the future career development curriculum for young women with disabilities. Journal of Career Development. 2019;46(4):469–483. doi: 10.1177/0894845318776795. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lüftenegger M, Schober B, van de Schoot R, Wagner P, Finsterwald M, Spiel C. Lifelong learning as a goal: Do autonomy and self-regulation in school result in well prepared pupils? Learning and Instruction. 2012;22(1):27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2011.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahat, M. (2020). Australian and Victorian Curriculum Reforms Overview. University of Melbourne. Figure. 10.26188/12910118

- Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. B. (1989). Designing qualitative research. Sage.

- McCallum F, Price D. Well teachers, well students. The Journal of Student Wellbeing. 2010;4(1):19–34. doi: 10.21913/JSW.v4i1.599. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLean KC, Breen AV, Fournier MA. Constructing the self in early, middle, and late adolescent boys: Narrative identity, individuation, and well-being. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2010;20(1):166–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00633.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod J. Student voice and the politics of listening in higher education. Critical Studies in Education. 2011;52(2):179–189. doi: 10.1080/17508487.2011.572830. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Michelsen, S., & Stenström, M. L. (Eds.). (2018). Vocational education in the Nordic countries: The historical evolution. Routledge.

- Ministerial Council for Education, Early Childhood Development and Youth Affairs. (2010). Australian blueprint for career development. Commonwealth of Australia. Retrieved from http://www.blueprint.edu.au

- Mitra D. Student voice in secondary schools: The possibility for deeper change. Journal of Educational Administration. 2018;56(5):473–487. doi: 10.1108/JEA-01-2018-0007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien KM, Dukstein RD, Jackson SL, Tomlinson MJ, Kamatuka NA. Broadening career horizons for students in at-risk environments. The Career Development Quarterly. 1999;47(3):215–229. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-0045.1999.tb00732.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2004). Career guidance and public policy: Bridging the gap. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/education/innovation-education/34050171.pdf

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2018). The future of education and skills: Education 2030. The future we want. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/education/2030/E2030%20Position%20Paper%20(05.04.2018).pdf

- Pak K, Desimone LM, Parsons A. An integrative approach to professional development to support college-and career-readiness standards. Education Policy Analysis Archives. 2020;28:111. doi: 10.14507/epaa.28.4970. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parliament of Victoria. (2019). Government response to the parliamentary inquiry into career advice activities in Victorian schools. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.vic.gov.au/925-eejsc/inquiry-into-career-advice-activities-in-victorian-schools

- Patton, W., & Porfeli, E. J. (2007). Career exploration. In V. B. Skorikov & W. Patton (Eds.), Career development in childhood and adolescence (pp. 47–69). Sense Publishers.

- Rivera LM, Schaefer MB. The career institute: A collaborative career development program for traditionally underserved secondary (6–12) school students. Journal of Career Development. 2009;35(4):406–426. doi: 10.1177/0894845308327737. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RJ. Conditions for a justifiable careers education. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling. 1983;11(2):170–183. doi: 10.1080/03069888308253755. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Savage GC. Who’s steering the ship? National curriculum reform and the re-shaping of Australian federalism. Journal of Education Policy. 2016;31(6):833–850. doi: 10.1080/02680939.2016.1202452. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer MB, Rivera LM. College and career readiness in the middle grades. Middle Grades Research Journal. 2012;7(3):51–66. [Google Scholar]

- Seidman, I. (2006). Interviewing as qualitative research: A guide for researchers in education and the social sciences. Teachers College Press.

- State Government of Victoria. (2019a). Practice principles for excellence in teaching and learning. Retrieved from https://www.education.vic.gov.au/school/teachers/teachingresources/practice/improve/Pages/Victorianteachingandlearningmodel.aspx

- State Government of Victoria. (2019b). Victorian teaching and learning model (VTLM). Retrieved from https://www.education.vic.gov.au/school/teachers/teachingresources/practice/improve/Pages/principlesexcellence.aspx

- State Government of Victoria. (2019c). Making sense of the teaching-learning cycle in reading and writing. Retrieved from https://www.education.vic.gov.au/school/teachers/classrooms/Pages/resourceslttwriting.aspx

- Stone, C., & O’Shea, S. (2019). Older, online and first: Recommendations for retention and success. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology,35(1), 57–69. 10.14742/ajet.3913

- Tanti C, Stukas AA, Halloran MJ, Foddy M. Social identity change: Shifts in social identity during adolescence. Journal of Adolescence. 2011;34(3):555–567. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trusty J, Niles S, Carney J. Education-career planning and middle school counselors. Professional School Counseling. 2005;9:136–143. doi: 10.1177/2156759X0500900203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turner SL, Conkel JL. Evaluation of a career development skills intervention with adolescents living in an inner city. Journal of Counseling & Development. 2010;88(4):457–465. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00046.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turner SL, Lapan RT. Evaluation of an intervention to increase non-traditional career interests and career-related self-efficacy among middle-school adolescents. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2005;66(3):516–531. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2004.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority. (2015). Victorian curriculum F–10 revised curriculum planning and reporting guidelines. Retrieved from https://www.vcaa.vic.edu.au/Documents/viccurric/RevisedF-10CurriculumPlanningReportingGuidelines.pdf

- Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority. (n.d.). Previous curricula. Retrieved from https://www.vcaa.vic.edu.au/curriculum/foundation-10/Pages/Previous-curricula.aspx?Redirect=1

- Watts T. Global perspectives in effective career development practices. Curriculum Leadership Journal. 2011;9(9):57. [Google Scholar]

- Welde A, Bernes K, Gunn T, Ross S. Integrated career education in senior high: Intern teacher and student recommendations. Australian Journal of Career Development. 2015;24(2):81–92. doi: 10.1177/1038416215575163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wheelock, A., & Dorman, G. (1988). Before it’s too late: Drop-out prevention in the middle grades. Centre for Early Adolescence. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED301355

- Whitty G, Rowe G, Aggleton P. Subjects and themes in the secondary school curriculum. Research Papers in Education. 1994;9(2):159–181. doi: 10.1080/0267152940090203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wyn J. Learning to ‘become somebody well’: Challenges for educational policy. The Australian Educational Researcher. 2007;34(3):35–52. doi: 10.1007/BF03216864. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R. K. (2017). Case study research and applications: Design and methods. Sage.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Upon request.

Not applicable.