Abstract

Introduction:

While increasing taxes on tobacco is one of the most effective tobacco control measures, its adoption has been slow compared to other tobacco control policies. Given this, there is an urgent need to better understand the political and economic dynamics that lead to its adoption despite immense tobacco industry opposition. The primary aim of this study is to explore the process, actors, and determinants that helped lead to the successful passage of the 2012 Sin Tax Reform Law in the Philippines and the 2017 seven-year plan for tobacco tax increases in Ukraine.

Method:

Under the guidance of the Advocacy Coalition Framework, we used a case study approach gathering data from key informant interviews (n = 37) and documents (n = 56). Subsequently, cross-case analysis was undertaken to identify themes across the two cases.

Results:

We found that external events in the Philippines and Ukraine triggered policy subsystem instability and tipped the scale in the favor of tobacco tax proponents. In the Philippines, elections brought forth a new leader in 2010 who was keen to achieve universal health care and improve tax collection efficiency. In Ukraine, the European Union Association Agreement came into force in 2017 and included the Tobacco Products Directive requiring Ukraine to synchronize its excise taxes to that of the European Union. Exploiting these key entry points, tobacco tax proponents formed a multi-sectoral coalition and used a multi-pronged approach. In both countries, respected economic groups and experts who could generate timely evidence were present and used local as well as international data to counter opponents who also used an array of strategies to water down the tax policies.

Conclusions:

Findings are largely consistent with the Advocacy Coalition Framework and suggest the need for tobacco tax proponents to 1) form a multi-sectoral coalition, 2) include respected economic groups and experts who can generate timely evidence, 3) use both local data and international experiences, and 4) undertake a multi-pronged approach.

Keywords: Advocacy, Tobacco tax, Policy change, Advocacy coalition framework, Industry interference

1. Introduction

Tobacco use is a leading cause of preventable death and disease around the world, causing 8 million deaths a year (World Health Orgnaization, 2019). In order to tackle this global epidemic, the first World Health Organization (WHO) treaty known as the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) was adopted during the 56th World Health Assembly in 2003. Article 6 of the FCTC requires parties to increase tobacco taxes, which is one of the most cost-effective tobacco control measures, as higher prices reduce initiation, decrease consumption among current smokers, and reduce relapse among former smokers (Chaloupka et al., 2012; Jha, 2009; Ekpu and Brown, 2015; Aungkulanon et al., 2019; Ngalesoni et al., 2017). Implementation guidelines for Article 6 encourage parties to adopt specific or mixed excise systems to simplify their taxation structure, adjust tax rates regularly to account for inflation, and increase affordability of tobacco products as consumer income increases. Guidelines also recommend that the same tax rate be applied to all products, and recommend earmarking a portion of tax revenue for tobacco control activities (Conference of the Parties, 2014).

Despite the importance of raising tobacco taxes, adoption and implementation of Article 6 by parties across the world is considered slow compared to other FCTC policies (World Health Orgnaization, 2019; Chung-Hall et al., 2019). Only 38 countries have adequately high taxes and most are in high-income countries (n = 23) (World Health Orgnaization, 2019). Some low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), however, have made significant strides, adopting and implementing policies that incorporate some of the guidelines from Article 6. According to the WHO, these “partial policies are a stepping stone to complete policies (p.24).” (World Health Orgnaization, 2019).

In recent years, two LMICs made considerable progress towards Article 6. In 2012, the Philippines, a lower middle-income country and one of the largest tobacco consumers in the Western Pacific Region (Republic of the Philippin, 2010), passed the Sin Tax Reform Law (Republic Act 10,351) despite substantial opposition from the tobacco industry and its allies. R.A. 10351 simplified the excise tax system on tobacco and alcohol products, increased tax rates, and earmarked incremental revenues generated from the tax for health (Republic of the Philippin, 2020a). Similarly, in 2017, Ukraine, a middle-income country in the European Region that suffers a high tobacco-related health burden (World Health Organization, 2017), passed a seven-year tobacco tax increase plan despite tremendous tobacco industry interference (Timtchenko, 2018). This seven-year plan increased tobacco excise taxes by specified percentages annually between 2018 and 2024 (EU-Ukraine Trade Union Committee, 2014; Rada, 2018). Prior to this, Ukraine never had a plan that increased tobacco taxes for several years into the future. The new policies in the Philippines and Ukraine deviated from previous tobacco tax policies in the two countries.

What factors contributed to these successes? Bump & Reich (Bump and Reich, 2013) highlighted the fact that there is currently little research that focuses on the political and economic dynamics of tobacco control policies in LMICs, and several researchers have called for a better understanding of the political economy of tobacco control (Reich, 2019; van Walbeek et al., 2013). Given that LMICs are increasingly burdened by the rising prevalence of non-communicable diseases associated with tobacco use,” (Eckhardt and Lee, 2019) the politics of tobacco control tax policy in LMICs are, therefore, a particularly important area of study.

In light of these gaps, this cross-case study aims to explore the process, actors, and determinants that help lead to the passage of the tobacco tax policies in the Philippines and Ukraine.

2. Advocacy Coalition Framework

This study utilizes the Advocacy Coalition Framework (ACF) as a starting point to organize our results; specifically, we apply the framework to the two cases then address the inconsistencies between the results and the framework. ACF is particularly useful when seeking to explain policy change that involves a wide range of actors and multiple levels of government, over an extended period of time (Sabatier, 1993). Developed by Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith in the 1990s, the main premise of ACF is that people become involved in politics in order to translate their beliefs into action. Accordingly, coalitions, defined as “people from a variety of positions (elected and agency officials, interest group leaders, researchers) who share a particular belief system—i.e. a set of basic values, causal assumptions, and problem perceptions—and who show a non-trivial degree of coordinated activity over time” (Sabatier, 1988: 139) form and vie with other coalitions, utilizing an array of strategies. These coalitions are situated within a policy subsystem defined as a policy area (e.g. tobacco policy) that is geographically bounded (e.g. Ukraine) (Sabatier, 1988; Roberts et al., 1994) and are affected by two types of exogenous factors: 1) relatively stable parameters and 2) external subsystem events. Relatively stable parameters are factors such as attributes of the problem area, sociocultural values, social structure, and constitutional structure that do not easily fluctuate over time and, as a result, produce long-term coalition opportunity structures as by-products; this might, for example, include openness of the political system. Unlike relatively stable parameters, external subsystem events are dynamic and can trigger temporary policy subsystem instability; in other words, these dynamic external factors such as changes in socioeconomic conditions, public opinion, and systemic governing coalition can tip the scale in favor of one coalition over another and provide short-term opportunities for major change (Roberts et al., 1994). ACF also indicates that the level of policy change – major or minor – is “defined according to the extent to which alterations deviate from previous policy” (p. 145). (Jenkins-Smith et al., 2017).

Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith identified four pathways to policy change: 1) external subsystem events outside of the control of policy subsystem participants. This event needs to be accompanied by one or several facilitating factor such as redistribution of resources and/or opening and closing of policy venues, which can shift the balance of the coalitions, providing one with more opportunities than the other and resulting in a minority coalition replacing a dominant coalition. Consequently, policy change reflects the winning coalitions’ policy beliefs; 2) events within the subsystem like crises or scandals, which can verify or discredit the beliefs of the dominant coalition, thereby raising concerns about their proposed policy option; 3) policy-oriented learning, which refers to the learning new information that could alter the assumptions of the coalition; and 4) negotiated agreements between the coalitions (Roberts et al., 1994; Jenkins-Smith et al., 2017).

While ACF has been employed to study tobacco control policy adoption in high-income countries (e.g. the United Kingdom, Canada, Japan, the United States) (Cairney, 2007; Breton et al., 2006, 2008; Smith, 2013; Wray et al., 2017; Sato, 1999; Wood, 2006), it has not been extensively used in the LMIC context (Khayatzadeh-Mahani et al., 2017). In fact, we did not find any studies that used ACF to explore tobacco tax policy adoption in LMICs. Further, there have been calls to explore the coordination within coalitions and types of members within coalitions to help enhance the framework (Weible et al., 2009).

3. Methods

A cross-case analysis design was used to explore the process, actors and determinants that led to the passage of higher tobacco taxes. The selection of the Philippines (case 1) and Ukraine (case 2) were guided by the most-different design where cases are as different as possible, except on the outcome of interest (Mill, 2016). This approach allows for the identification of factors common across cases that are likely to have contributed to policy change. Our two cases differed with regards to their political system and geographic location: Ukraine is a semi-presidential unitary republic located in Eastern Europe, while the Philippines is a presidential, representative, and democratic republic situated in Southeast Asia. For each case, data were gathered from two sources– documents and key informant interviews. This study was deemed non-human subjects research by the authors’ Institutional Review Board.

3.1. Data collection and analysis

Data collection took place in Manila, Philippines and Kiev, Ukraine during January 2018 and February 2019, respectively. Across the two cases, 37 in-depth interviews were conducted with key informants (12 from Ukraine and 25 from the Philippines) who were purposively sampled based on the following criteria: played a significant role in the tobacco tax policy process, led an organization that is involved in the passage of the tobacco tax policy, and/or possess extensive knowledge of tobacco taxes in Philippines or Ukraine. These key informants included individuals who were working for governmental organizations, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), international/multinational organizations, universities, media and/or tobacco industry (Table 1). Interviews averaged 53 min, and were all conducted in English except for one, which was conducted through a professional translator. Recorded interviews were transcribed and notes were converted into textual form. Six categories of codes were developed from the conceptual framework to allow for deductive coding [see Supp. 1]. An example is “Pass_Tactic”, which was used when participants mentioned the strategies tobacco tax proponents employed to pass the tobacco tax policy. Inductive coding was also undertaken to allow for new themes to emerge. An example is “Alcohol vs Tobacco” for the case of the Philippines. This code was used when participants discussed about the differences between alcohol versus tobacco as it relates to the passage of the 2012 Sin Tax.” Other inductive codes that emerged during the study fell under the existing categories of codes. One example is “EU” which was used when participants mentioned Ukraine’s desire to join the European Union (EU) as a reason for the passage of the seven-year plan.

Table 1.

Key informant in-depth interviews (IDI) by affiliation, country and codes.

| Organizational Affiliation | Philippines Informant IDIs | Ukraine Informant IDIs |

|---|---|---|

| University | IDI 9 | IDI 29 |

| Government | IDIs 5, 8, 12,14, 16,17, 19, 21,24, | |

| International/multilateral organization | IDI 1, 3, 4, 6, 10, 15, 13, 22, 23 | IDIs 26, 27, 28, 30, 33, 35, 37 |

| Media | IDI 20 | |

| Local NGO | IDI 2, 7, 11,18 | IDI 31, 32, 34, 36 |

| Tobacco Industry | IDI 25 | |

| Total | 25 | 12 |

Across the two cases, 56 documents were reviewed, of which 14 documents relevant to the Ukraine case study were translated using Google Translate. These documents were purposively sample based on their relevance to the study objective and obtained from key informants, PubMed, local news sources, and advocacy websites. Documents included NGO documents (n = 17), local news articles (n = 15), peer reviewed academic articles (n = 8), academic grey literature (n = 10), and government documents (n = 6). Data pertaining to the conceptual framework and new themes that emerged were extracted onto an excel spreadsheet.

3.2. Cross-case analysis

In order to identify similarities and differences across the two cases, a cross-case analysis was conducted (Yin, 2003; Khan and VanWynsberghe, 2008). Data from the two cases were displayed in a matrix [see Supp. 2] using the domains of the conceptual framework and new themes that had emerged, allowing for common themes to be compared. All analysis was conducted in HyperRESEARCH and Microsoft Excel.

4. Results

4.1. Case 1: The Philippines

4.1.1. Relatively stable parameters

Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith defined relatively stable parameters as factors external to the policy subsystem (e.g. basic attribute of the problem, and constitutional structure) that do not easily fluctuate and can affect the behaviors of the coalitions (Sabatier, 1988).

With regards to the constitutional structure, the Philippines has a presidential form of government comprised of the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. While the constitutional structure of the country is influenced by the American system (Republic of the Philippin, 2020b), the Philippines has a unitary rather than federal form of state where power is concentrated in the executive branch, giving “rise to a constitutional order that allows governance of the country to be overly reliant on the President” (Yusingco, 2018).

The basic attributes of the problem were that tobacco use is one of the leading causes of death, killing 117,700 Filipinos each year (The Tobacco Atlas. Philip, 2018). Prior to the passage of the Sin Tax, 27.9% of adults were current smokers (Republic of the Philippin, 2010) and 27.5% of youth between the ages of 13 and 15 had ever smoked cigarettes (Republic of the Philippin, 2011). This made Philippines one of the top consumers of tobacco. While the country ratified the FCTC in 2005, cigarette price in the Philippines was historically one of the lowest in the world in part due to modest tax rates (Miguel-Baquilod et al., 2012). Prior to 2012, the specific excise tax was based on a 4-tiered system (Thirteenth Congress. Repu, 2004; Southeast Asia Tobacco Co, 2013). In 1996, the Bureau of Internal Review conducted a price survey to identify the net retail price (NRP) of all cigarette brands to classify cigarettes into a tier based on their price. This meant, expensive cigarettes were taxed at a higher rate than inexpensive cigarettes. The NRP identified in 1996 was “frozen” in a “price classification freeze” perpetually, with brands entering the market after 1996 having their NRP calculated when they entered the market. This advantaged older brands because their NRP was determined when inflation, and therefore prices, were lower. In addition, previous legislation only mandated every-other-year tax increases through 2011. After this point, a new legislation was needed to increase tobacco taxes (Thirteenth Congress. Repu, 2004; Southeast Asia Tobacco Co, 2013).

Analysis of tobacco industry documents revealed that this situation was largely due to tobacco companies interfering with tobacco tax policy making (Southeast Asia Tobacco Co, 2013; Alechnowicz and Chapman, 2004). In fact, it is known that the Philippines has the “strongest tobacco lobby in Asia.” (Alechnowicz and Chapman, 2004) In addition to industry interference, Philippines’ situation was also complicated by the fact that the country is a tobacco-producing one. Much of the tobacco is grown in the northern part of the country and legislators from that area often support pro-tobacco policies (In-depth interview (IDI) 1, 7). Despite this, the tax reform movement started in the mid-1990s and was spearheaded by the Department of Finance (DoF) in an effort to generate revenue and increase the efficiency of the tax system (IDI 1, 4, 5, 9, 13) (Drope et al., 2014). Similar to other countries, the health sector was not as engaged. Informants attributed this to the lack of familiarity with taxation (IDI 1, 4).

4.1.2. External events

According to ACF, dynamic events outside of the policy subsystem such as government transition can tip the scale in favor of one coalition over another and provide short-term opportunities for that coalitions (Sabatier, 1988). In 2010, Benigno Aquino III was elected as the 15th President of the Philippines. Two of his key priorities as the new head of state were to increase tax collection efficiency and achieve universal health care (Southeast Asia Tobacco Co, 2013; Drope et al., 2014; Aquino, 2011) (IDI 1). Seeing this as a potential alignment in agendas and recognizing the fact that Presidential support will help prioritize the Sin Tax (IDI 4, 7), proponents from various sectors seized this opportunity and reached out to the President to convince him to support the reform (IDI 2, 5, 7, 10, 13). Key informants believed that two key factors helped convince the President: 1) the need to finance Universal Health Care as he had promised during his campaign (IDI 1, 2, 7, 10, 17); and 2) the fact that Aquino, himself, was a smoker and did not want others to suffer the same addiction (IDI 5, 12, 14, 21).

“There were a lot of people … Different people were– we call it the bumulong advocacy. Whisper, bumulong is whisper, so you– there are a lot of people who would whisper to the right people so that it would reach the president … So it was a confluence of factors. So if your promise is health care, universal health care, the next question would be where will the money come from? So multiple sources of whispers strengthen the call, the clamor for, “Oh, why not sin tax?”” – NGO Actor.

In 2011, Aquino formally announced Sin Tax reform as part of his legislative agenda (Legislative Executive Dev, 2016; Madore et al., 2015). This support was critical (IDI 4, 9, 13, 15, 16, 19) as it expanded support for the bill and helped overcome opposition (IDI 2, 4, 6, 7, 12, 13, 18, 19).

“I mean, if you were to ask me what would be the single important factor, it would be, of course, the president.” – Government Official.

4.1.3. Policy subsystem – coalitions and strategies

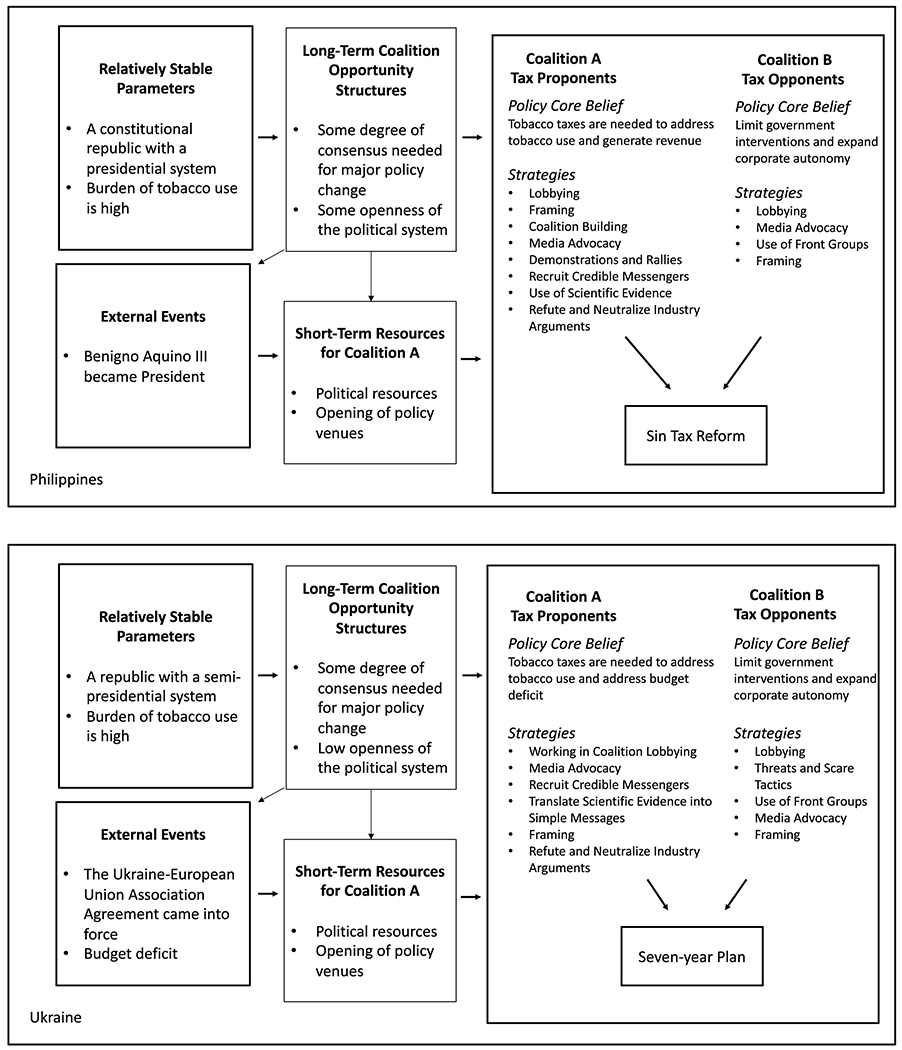

The external event triggered policy subsystem instability by shifting political resources to and opening policy venues for the coalition of Sin Tax Proponents; it provided a window for this coalition to replace the dominant coalition of opponents (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Philippines and Ukraine’s policy subsystems.

The initial coalition of proponents within the policy subsystem was a small group of tobacco control civil society organizations, who believed that tobacco use is a serious health concern, and the preferred solutions are ones that are consistent with the Framework Convention for Tobacco Control, including tobacco taxation (policy core belief) (IDIs 4, 13). They joined forces with the Department of Finance and an economic think tank who also believed that these products produce negative health outcomes and taxation can reduce health impact, generate revenue, and increase tax collection efficiency (IDIs 2, 5, 16) (policy core belief). This solution required government intervention to promote public health.

One of the key strategies undertaken by proponents was framing the Sin Tax as a health rather than revenue generating measure that will help achieve Universal Health Care (IDI 2, 4, 7, 16). (Paul, 2016; Paul).

“But when we said, “This is really a health measure, not a revenue measure,” I mean, then you are able to create more allies, yeah? Because health resonates with more people than– I mean, if you say, “Revenue,” people just said, “You’re just greedy, you want more money for government to corrupt.”” – Government Official.

This vision facilitated another key strategy - the formation of a broad-based, multi-sectoral coalition to tackle tobacco tax for the very first time (IDI 2, 3, 4) (Southeast Asia Tobacco Co, 2013). This “coalition of champions” (IDI 16) was steered by a “core group” (IDI 2, 3, 16) of well-connected and passionate individuals who capitalized on their own networks to mobilize other groups (IDI 1, 2) (Madore et al., 2015). Such skillful leadership is also considered a critical resource for the coalition (Jenkins-Smith et al., 2017).

“There was an inner core, a core group that cuts through the different sectors. So the coalition is composed of government and civil society partners. The core group is updated in real time, and then the core group is responsible of coordinating with other organizations who are part of a broad movement.” – NGO Actor.

Key informants explained that the involvement of such a diverse set of actors was critical as it not only underscored how popular the Sin Tax policy was amongst different groups of the population, but it also allowed the proponents to increase the visibility of the issue, cross-check their data and models on the health and economic impact of the policy, and pool together resources (e.g. human, financial, and social capital) (IDI 1, 2, 3, 4, 9, 16). (Southeast Asia Tobacco Co, 2013; Madore et al., 2015).

From the government side, the Undersecretary of DoF was assigned to spearhead the Reform for DoF. The Undersecretary emerged as one of the key political champions (IDI 1, 3, 4) who was highly skilled at connecting different individuals and groups (IDI 16). Further, the collaboration that emerged between champions from DoF and DoH, including the Secretary of Health, was vital as informants described this “whole government approach” as one of the key ingredients to Philippines’ success (IDI 13, 16, 19; 46). By “whole government,” the informants meant the involvement of multiple government agencies and in particular DoH.

The main difference between earlier efforts to reform sin tax, especially the final part of it and what happened in 2012, was that the health sector became involved. – Government Official.

From the civil society side, groups engaged in media advocacy (Southeast Asia Tobacco Co, 2013) to influence public opinion and expose industry tactics (IDI 3, 4, 11) (Southeast Asia Tobacco Co, 2013; Drope et al., 2014), developed policy briefs (IDI 7) (Southeast Asia Tobacco Co, 2013; Drope et al., 2014; HealthJustice. Million of, 2012), and organized demonstrations and rallies (IDI 11). Their efforts to raise public support appeared to be successful; this provided another important resource for the coalition. As one key informant noted:

“So we’ve reached that point that in a menu of tax policies, the consciousness of the Philippine people had opened itself to embracing that there are good kinds of taxes and bad kinds of taxes, or badly designed.” - NGO Actor

Civil society groups also brought on a medical doctor who was a professor at one of Philippines’ top universities. He was described as “articulate” (IDI 16) and capable as well as willing to respond to last minute requests for data (IDI 9, 16). Given the framing of the Sin Tax as a health measure, this medical doctor served as one of the key messengers for the Sin Tax coalition (IDI 2, 6, 9) and “the public face for doctors” (IDI 6). He along with other groups representing different voices (e.g. medical doctors, youth and victims), presented during House and Senate hearings. New Vois, a group of former smokers suffering from the devastating health consequences of tobacco use, was another one of these key voices that was described as “persuasive” (IDI 16).

It is important to note that civil society groups were effective because they were trusted by government officials (IDI 16); one of the members, Action for Economic Reform, was a “respected economic group” (IDI 1) that has a long-standing relationship with DoF (IDI 4, 15), which was an important political resource.

“You have to have people with credibility and reputation within taxation to do the tax work because they can convey the message better.” – International Actor

International allies provided technical and financial resources during the process (IDI 1). In particular, government officials reached out to experts at the World Bank who assisted the Departments in using international and local data to refute and neutralize industry arguments as these were the same arguments that have been used in other contexts (IDI 15, 16) (Madore et al., 2015; Purisima, 2012). The World Bank also helped set medium-term revenue goals to finance Universal Health Care, which informed what tax rate would be required to meet this need (IDI 15, 16).

To ensure that the diverse set of proponents were working towards a common vision, the “core group” met regularly in what was referred to as the “war room” (IDI 15, 19) to devise and align strategies, that were then echoed to the rest of the supporters (IDI 2). Members were also given “the space to enact their own methods (IDI 2),” as long as it was geared towards a common goal. Key informants explained that the diverse set of proponents also brought about a diverse set of perspectives and “at every point of the campaign we disagreed” (IDI 2). A key area of conflict was the sharing of tax burden between tobacco and alcohol since the Sin Tax included taxes on both products and proponents were concerned that the two industries would join forces (IDI 3, 4, 7, 9, 16, 19). To resolve these conflicts, proponents debated, reminded themselves of the key objective, and identified the issues shared by everyone. In the case of tobacco versus alcohol, they decided to focus on tobacco.

“So it became our method of resolving conflict was we debated it, and it became what would be the easiest, or the most– what is our objective? What issue is shared by everyone? And it was clear that tobacco control was the single most– tobacco tax was something that was easiest for everyone to agree on.” – NGO Actor

This decision was also facilitated by the fact that there were no alcohol control organizations in the country (IDIs 2, 6, 7).

Political mapping was also undertaken continuously throughout the legislative process to identify supporters, fence-sitters and staunch opponents (IDI 1, 7, 11, 16) (Fig. 1). Table 2 illustrates the range of members involved in the pro-Sin Tax coalition. This coalition faced inevitable opposition from opponents (Table 2) who appeared to be bound by the policy core belief of limiting government interventions and expanding corporate autonomy. They also used an array of strategies including lobbying, media advocacy and interference as well as front groups to block and/or water down the Sin Tax during the legislative process (Fig. 1) (IDIs 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 10, 13, 16, 17, 22) (Southeast Asia Tobacco Co, 2013; Drope et al., 2014; HealthJustice. World Toba, 2012). These opponents, for example, argued that increasing taxes will result in smuggling, and is regressive (IDI 16, 22). Proponents countered these frames using data to explain that the price of cigarettes in the Philippines is so low that even after the tax increase other countries in the region will still have more expensive cigarettes. As such, the Philippines is more likely to be the source of exported illicit products (IDIs 4, 22). Further, opponents argued that the poor have the highest prevalence of smoking in the Philippines and are the most burdened by the health effects of smoking. Taxation can bring about substantial health and financial benefits and the revenues generated from the Sin Tax will be used progressively to cover health insurance for the poor (IDIs, 1, 2, 4, 7, 13).

Table 2.

List of example proponents and opponents in the Philippines and Ukraine.

| Philippines |

Ukraine |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Proponents | Opponents | Proponents | Opponents |

| Government entities: e.g. The Office of the President, Department of Budget and Management, Department of Finance, Bureau of Internal Revenue, Department of Health, Some legislators, Local government executives | Tobacco industry: e.g. Philip Morris Fortune Tobacco Company, Mighty Corporation | Government entities: e.g. Ministry of Finance, Tobacco Control Unit Institute for Strategic Research at the Ministry of Health | Tobacco industry: e.g. Philip Morris Ukraine, British American Tobacco Ukraine, Japan Tobacco International Ukraine, Imperial Tobacco Production Ukraine, Vinnykivska Tyutynova Fabryka |

| Civil society organizations: e.g. Action for Economic Reform, HealthJustice, Framework Convention on Tobacco Control Alliance Philippines, Youth for Sin Tax, New Vois Association of the Philippines, WomanHealth Philippines, South East Asia Tobacco Control Alliance | Industry associations: e.g. Philippines Tobacco institute, National Tobacco Administration | Civil society organizations: e.g. LIFE Advocacy Center, Center for Democracy and Rule of Law | Industry associations: e.g. Ukrainian Association of Tobacco Producers “Ukrtyutyun” |

| International and multi-lateral institutions: e.g. World Bank, Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids, World Health Organization, The Union | Industry front groups: e.g. Philippines Tobacco Growers Association | International and multi-lateral institutions: e.g. World Bank, World Health Organization | Industry front groups: e.g. Ukrainian Economic Freedom Foundation |

| Academic and medical institutions and professionals: e.g. University of the Philippines College of Medicine, Philippine College of Physicians, Philippines Medical Association | Some legislators: e.g. those from the Northern Alliance | Academic institutions and professionals: e.g. Alcohol and Drug Information Center (ADIC-Ukraine), UK Health Forum | Some Parliamentarians: e.g. from The Committee on Taxation and Customs Policy |

| Business Associations: e.g. American Chamber of Commerce | Business Associations: e.g. American Chamber of Commerce and European Business Association | ||

Opponents suffered fragmentation with some opposing the Sin Tax in its entirety while others opposing some aspects (IDI 3, 4, 7, 16, 25). British American Tobacco even supported the Sin Tax Reform as this policy would remove the price tiers and level the playing field (IDI 1, 2). Tobacco companies also competed with each other for lower prices and had different tax structure preferences (IDI 1,3). Proponents also actively contributed to the fragmentation of the opponents, negotiating a lower tax increase for alcohol compared to tobacco in order to prevent the industries from joining forces (IDI 16).

“The alcohol people threatened not to support the reform unless they were given some concession. So we didn’t fight that battle, in order to get the tobacco reforms” – NGO Actor.

4.1.4. Legislative process – key events

In the Philippines, legislative power resides in the Congress, which consists of the House of Representatives (House) and the Senate. The House is composed of about 250 members elected from legislative districts and representatives elected through a party-list system and the Senate is composed of 24 Senator who are elected by voters (Republic of the Philippin, 2020b; Republic of the Philippin, 2020c). Only half of the Senators are up for election/re-election every three years (Senate of the Philippines, 2020). Both houses are critical to the passage of a tax bill, like the Sin Tax, as it must be first approved by the House, but the Senate reserves the right to “propose or concur with amendments” (Sec. 14, 1987). Accordingly, the first hurdle for the proponents was to advocate for the passage of the bill in the House, which has traditionally been controlled by the tobacco industry. Fortunately for the proponents, the House elections took place in 2010, and the new chair of the House Ways and Means Committee did not have such ties (IDI 16, 19). (Southeast Asia Tobacco Co, 2013; Drope et al., 2014).

“But what really moved the reform for us was that the chairman, [he] was behind us all the way. So he used his powers and authority as the Chair to move the discussion and the approval in favor of the reform.” - Government Official.

Before voting, the new chair convinced his core group of supporters to recruit other members with the use of evidence (IDI 16). The medical community also complemented this effort by reaching out to relatives of congressmen as well as congressman who had relatives who died of tobacco use (IDI 16). Undoubtedly, the support of the President also facilitated this process.

“At that time, 2011, he was in office just for a year or so he still had pretty strong connections, and even the opposition wanted to be on his good side. So there was a big majority, politically speaking, for him. So that helped push it through the lower house.” – NGO Actor.

Proponents set up a meeting between the President and the Speaker of the House, Ways and Means Committee and other Senior Members of Congress (IDI 4, 16). They also compromised on the house version of the bill with the knowledge that they could work on a better version in the Senate (IDI 16, 4, 7). On June 6, 2012, the bill was passed by the house.

The next hurdle was to advocate for the passage of the bill in the Senate. Unfortunately, Senator Ralph Recto, chairman of the Ways and Means Committee who was elected to the position in 2010, filed a bill that resembled Philip Morris’ stance, as it presented the same low rate (Drope et al., 2014; Watered, 2012). Sin Tax proponents used an array of strategies including lobbying, media advocacy and daily rallies to call for the resignation of Recto, cleverly naming the bill the “Recto-Morris bill” (IDI 1, 3). This ultimately raised up to the level of the president, who subsequently “used his political muscle” to push for his resignation (Southeast Asia Tobacco Co, 2013; Drope et al., 2014; Madore et al., 2015). On October 15, 2012, Recto resigned and was replaced by a Sin Tax Proponent and key political champion who was a member of the same political party as President Aquino. This senator’s wife passed away as a result of lung cancer (IDI 1, 6, 16). (Southeast Asia Tobacco Co, 2013; Drope et al., 2014).

After the House and the Senate passed their versions of the bill, differences between the versions were then reconciled in a Bicameral Conference Committee. Unfortunately, this was not a transparent process and the bill passed by only one vote due to the alleged connections of the industry (IDI 7). (Drope et al., 2014).

“It’s a closed-door meeting so there’s no accountability. You can vote yes or no, insert, and no one will know who did what and who voted.” - Academic.

One proponent, however, credited the chairman of the Senate Ways and Means Committee for pushing through the version of the bill the proponents had been advocating for (IDI 9). On December 11, 2012, the committee signed the report and the bill was transmitted to the President for approval. Finally, on December 20, 2012, Aquino signed the historic sin tax bill into law.

4.2. Case 2: Ukraine

4.2.1. Relatively stable parameters.

Ukraine has a semi-presidential system of government, where the president is elected by popular vote and the prime minister is appointed by the president with approval from the unicameral parliament (Verkhovna Rada). Since 1996, the constitution has been altered a few times to modify the balance of power between the president and parliament. In 2014, the 2004 Constitution was restored, re-transitioning the country from a presidential-parliamentary form of government to a parliamentary-presidential one and thus returning some power from the president to the parliament (constitutional structure). (Averchuk, 2019; Ukraine’s Constitution: a, 2018; Choudhry et al., 2018).

The basic attributes of the problem were that tobacco use is a major public health problem in Ukraine; in 2017, about 23% of Ukrainian adults reported using tobacco products and over 130,000 Ukrainians died as a result of tobacco-caused diseases (Ministry of Health of Ukraine, 2018; Institute for Health Metr, 2018). The economic burden is also immense; it is estimated that almost 4 percent of Ukraine’s Gross Domestic Product is lost due to loss of productivity related to tobacco use (Ross et al., 2009). While the Ukrainian government ratified the FCTC in 2006, the country has not fully adhered to Article 6 (He et al., 2018).

Ukraine’s historically low tobacco taxes were enabled by tobacco industry interference. The industry was initially successful at convincing Parliament to lower taxes in the early 1990s, but Parliamentarians soon realized that the industry’s strategy was not resulting in sufficient revenue and increased taxes (Krasovsky, 2010). This, however, was short-lived. In 1999, the industry successfully convinced Parliament to implement the tax in local currency (hryvnia) rather than in euros. This resulted in negligible tax increases and decreased the overall cost of cigarettes until 2008 (Krasovsky, 2010; Ross et al., 2012); 2008 was the first year that taxes increased dramatically (Krasovsky, 2010), which set the stage for multiple tax increases thereafter. The most dramatic increase occurred between 2014 and 2017 (Hayes et al., 2013; Krasovsky, 2013). Although cigarettes in Ukraine have remained inexpensive compared to prices in other European countries (Panko, 2020), this history of success meant that members of Parliament and the Ministry of Finance (MoF) were already aware of the harms of tobacco use, the tactics of the industry, and tobacco taxes as a reliable source of revenue. As a result of this context, it was easier for tobacco taxes to make it onto the agenda (IDI 26, 29, 31, 36, 37). (Hayes et al., 2013; Ukraine, 2017; Ukraine Center for Tobacc, 2020).

4.2.2. External events.

In recent years, Ukraine experienced political and economic turmoil outside of the control of the policy subsystem participants. After former president Viktor Yanukovych rejected the Ukraine-European Union Association Agreement (UEUAA) in 2013 in favor of strengthening ties with Russia, a wave of demonstrations and unrest spread throughout the country (The Henryackson Scho, 2017). Popularly known as the “Euromaidan,” this pro-West uprising which first centered around the desire to forge closer ties with the European Union, evolved into a wide-spread demonstration against corruption and authoritarianism that eventually led to the removal of Yanukovych in February 2014 (The Henryackson Scho, 2017). Following these events, Crimea, a peninsula located in Donbas region of Ukraine, was unlawfully annexed by Russia; subsequently parts of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions were invaded and occupied (Pifer, 2019). Over 10,000 lives were lost as a result and the country’s economy also took a significant hit, creating a budget deficit (Pifer, 2019).

In 2014, the newly elected President, Petro Poroshenko, signed the UEUAA which included the Directive 2011/64/EU (EU-Ukraine Trade Union Committee, 2014; Pifer, 2014). This directive specified the structure and rates of excise duty applied to manufactured tobacco including a minimum rate of 90 euros per 1000 cigarettes. The Association Agreement came fully into force in 2017 and Ukraine was required to align its policies in order to join the European Union (Kocijancic et al., 2017).

4.2.3. Policy subsystem – coalitions and strategies.

These external events provided more political resources for the coalition of tobacco tax proponents and opened policy venues, (IDI 29) allowing an opportunity for the proponents to become the dominant coalition. Having a firm grasp of the political economy, these proponents understood that generating revenue as well as harmonizing with the European Union policies were key “entry points” to the political process (IDI 28, 31, 36) and began the discussion of a longer-term tax increase strategy in 2014 (IDI 33, 36) (Fig. 1).

Table 2 shows the range of proponents involved in the coalition for higher tobacco tax. Having worked together on previous tobacco tax increases in the country, these proponents were not only well acquainted with one another but were also skilled at coordinating their efforts, and capitalizing on each other’s expertise (IDI 28, 29, 31, 36, 37), which helped provide critical resources (e.g. human, financial, and social capital). The coalition of tobacco tax proponents appeared to be bound by the policy core belief that government interventions, like increasing taxes on tobacco, are needed to address the high burden of diseases attributable to tobacco use and the country’s large budget deficit (IDI 3, 6, 8 11).

While key informants mentioned supporters within both MoF and Ministry of Health (MoH) (IDI 28, 31, 32, 36, 37) (Timtchenko, 2018) only one identified specific champions (IDI 36). This could, perhaps be due to frequent changes in Ministers and how behind-the scenes the MoF has remained throughout this process (IDI 31, 33). Informants also highlighted their wish for the MoH to be more involved.

“This is kind of our dream that Ministry of Health, they should be more involved in this.” – NGO Actor

NGO Advocacy LIFE (LIFE) stood out as one of the key actors from the civil society side. Described as a “credible” (IDI 33) tobacco control expert group (IDI 26, 31), members worked directly with decision makers, providing recommendations as well as protecting the government from public and industry backlash (IDI 26, 31, 33). LIFE was particularly skilled at media advocacy and used multiple strategies to attract media attention in order to increase awareness about the harms of tobacco use and highlight the importance of increasing tobacco taxes for public health (IDI 26, 28, 29, 31, 33, 36).

LIFE also worked closely with key local academic experts to translate evidence into simple messages that could be easily understood by decision makers, the public, and journalists (IDI 31, 36). One of these experts was a Ukrainian tobacco control researcher. He was described as “very skillful, very quick” (IDI 31) and was regularly monitoring and analyzing country-specific data. As such, he was able to provide evidence, including evidence to counter industry arguments, to other proponents in a timely manner (IDI 31). Given that this academic expert has worked on the issue of tobacco control in the Eastern European Region for many years, he had connections with bureaucrats within the MoF and was able to provide his expertise to government officials as well as during press conferences (IDI 29, 31). (Ukraine Center for Tobacc, 2020; The Ministry of Health be, 2017).

The involvement of international allies and in particular the World Bank was noteworthy. Given that the mandate of the World Bank is to provide financing, policy advice, and technical assistance to governments, they were regarded as a critical and “equal” (IDI 31) stakeholder by Ukrainian decision makers and has had a good and long-standing relationships with the MoF (IDI 28, 29, 31, 36, 37).

“Ministry of Finances is always more closed, usually, more closed to government for NGOs because they deal with the financials, very serious and they don’t need us … but the World Bank seem to be a stakeholder for them. They had more trust in World Bank because World Bank has economists” –NGO actor

The coalition of proponents was also able to secure the support of the World Bank’s country director which allowed them to gain access to Ukrainian government officials at the highest level (IDI 28) – an important political resource. In addition to facilitating access, the World Bank also worked with local experts to generate evidence using local data that would help refute tobacco industry arguments and develop models to show the health and economic impact of the policy (IDI 28, 29) (Fig. 1).

In addition to arguing that a longer-term plan will help Ukraine harmonize with the EU and address the budget deficit, proponents framed the policy as a win-win policy (win for health and win for revenue). This was important as informants believed that the health frame resonated more with the MoH, parliamentarians and the public and the finance frame resonated with the MoF (IDI 28, 36, 37).

“In the case of Ukraine, given the relative high level of consumption of cigarettes, particularly among adult males, the numbers that we were able to obtain based on our simulation were quite high. So the ministry of finance was quite happy in endorsing this measure. But again, we kept arguing that a key objective of the measure, and that also helped sell the policy to the parliamentarians as well as to the general public, was the health benefit to be generated out of it by reducing consumption. And we also argued that, from a fiscal point of view, besides the additional revenues that could be mobilized to expand the fiscal capacity of the government, the reduction of the risk of tobacco-attributable diseases was going to be beneficial for the government also because the need, demand, and utilization of costly services was also to decrease.” –International Actor.

Public support for tobacco tax was consistent (resource). As one key informant noted:

“So polling shows pretty much uniformly that taxation, increasing prices on tobacco products in Ukraine, remains consistently generally popular.” – NGO Actor

Unsurprisingly, proponents of increased tobacco tax were met with opposition even though publicly the tobacco companies stated their support for the tax increase (Holubeva, 2069; A pack of cigarettes in U, 2020). Table 2 illustrates the array of opponents; these opponents appeared to be bound by the policy core belief of limited government intervention in favor of corporate autonomy. Unlike proponents, however, tobacco companies have often fought with each other when it comes to tobacco taxes. Transnational companies such as British American Tobacco, Philip Morris International and Japan Tobacco International, for example, all opposed an increase in the ad valorem component of the tax, while local companies favored it (Panko, 2020; Skipalsky, 2017). Proponents compromised on the inclusion of an ad valorem tax increase in order to garner opponents support (IDI 33, 36).

“Tobacco companies come together when it comes to arguments but when it comes to different price segments they try to kill each other.” – NGO Actor

Opponents used various strategies during the legislative process to weaken the proposed tax bills, including behind-the-scenes lobbying, use of threats and scare tactics, and formation of front-groups to support the tobacco industry’s position (IDI 26, 29, 31, 32, 34, 36) (Panko, 2020; Skipalsky, 2017). Opponents also used media advocacy to discredit tobacco control proponents, suggesting that these proponents are only concerned about receiving foreign funding rather than improving public health in Ukraine (IDI 26, 30, 31) (Fig. 1). Moreover, opponents argued that tax increases will result in illicit trade and smuggling (IDIs 28, 31, 36). Proponents countered with data explaining that cigarette prices in neighboring countries are higher than the cigarette prices in Ukraine. As such, raising taxes will decrease the smuggling of cigarettes out of Ukraine (IDIs 28, 31).

4.2.4. Legislative process – key events.

In Ukraine, a tax bill is usually registered by the cabinet of Ministers although members of parliament can also register a tax bill. During this time, MoF registered a bill, proposing an eight-year plan with the proposed increases in euros. Informants suspected that the bill was leaked out as a similar plan was registered by a group of Parliament members at around the same time with proposed increases in local currency (IDI 31, 36) (Skipalsky, 2017). After a tax law is registered, it goes to a tobacco tax subgroup within the Committee on Taxation and Custom Policy which reviews it and provides its support and/or recommendations for change before it goes to the Parliament for the first hearing where a vote is taken. Suggested amendments are allowed to be made within 14 days after which this committee works on the amendments and prepares a draft law for the second reading. Given the importance of this subcommittee, it is unfortunate for proponents of higher tobacco tax, that members have links to the industry (IDI 26, 30, 31, 34, 36) (Transparency Internationa, 2017). The head of this subgroup between 2014 and 2019, for example, has a daughter who had, in the past, worked for Philip Morris International (IDI 31). (Transparency Internationa, 2017).

A news article published in 2017 also exposed the presence of tobacco company representatives at an “emergency” meeting held by the Committee on Tax and Customs Policy during the 1st reading to vote on terms from the bill to be included in the seven-year plan (Skipalsky, 2017).

During the second reading, the amendments are voted on (IDI 31, 32). The Ukrainian legislative process was also not a transparent one and industry interference was described by key informants as covert (IDI 27, 30, 31, 32). (Timtchenko, 2018).

“But we cannot see it sometimes. So even if they voted for something, the head of the committee, she can change, and then other stuff. So it’s not so transparent, unfortunately.” – NGO Actor.

On December 30, 2017, the President signed the bill into law, which includes the seven-year plan that will increase tobacco tax by nearly 30% in 2018 and 20% every year between 2019 and 2024. While a victory for public health, key informants suspected that industry interference likely resulted in the adoption of the version of the seven-year plan that administered the tax in local currency rather than in euros and switching the annual inflation adjustment from mandatory to optional, both of which occurred at the “emergency meeting” during the first reading (IDI 27, 31, 36) (Timtchenko, 2018; Ukraine, 2017). Both make it challenging for Ukraine to reach the EU requirement of 90 euros per 1000 sticks by 2025 (Skipalsky, 2017).

4.3. Cross-case analysis

The cross-case analysis showed that in both countries, external events – Benigno Aquino III becoming the 15th President of the Philippines in 2010 and Ukraine-European Union Association Agreement coming into force in 2017 – tipped the scale in the favor of tobacco tax proponents. While these external events appeared to be necessary for policy change, they were not sufficient in themselves as per the ACF. In both cases, the coalition of tobacco tax proponents had to swiftly and skillfully seize the opportunity to achieve their policy goals. The coalition of tobacco tax opponents, however, also used an array of strategies to successfully water down the tax policies.

5. Discussion

This study sheds light on the process and determinants that led to the passage of tobacco tax policies in the Philippines and Ukraine despite immense industry opposition. These findings underscore the utility of ACF and uncovered four additional themes; this included the importance of: 1) a multi-sectoral coalition, 2) respected economic groups and experts who can generate timely evidence, 3) both local data and international experiences, and 4) a multi-pronged approach. Future studies are needed to determine whether these factors are critical facilitators more generally.

A key feature of both advocacy efforts was the presence of a multi-sectoral coalition involving a diverse set of actors who capitalized on each other’s strengths and aligned strategies to ensure that all proponents were working towards a common goal. This finding is consistent with existing studies examining initiatives to increase cigarette taxes in Montana and Oregon (Moon et al., 1993; North, 1998). Likewise, James et al. (2020) described strategic cooperation between proponents from various sectors as vital during the passage of the sugar-sweetened beverage tax in Mexico (James et al., 2020). Future studies could use social network analysis to explore the structure and evolution of these multi-sectoral coalitions. While a multi-sectoral coalition was present in both countries, it involved more actors, particularly civil society actors (CSA), in the Philippines as compared to Ukraine. This could, in part, be due to the challenges CSAs face in Ukraine given that the country is less democratic than the Philippines. The 2019 Democracy Index, for example, rated the Philippines as a “flawed democracy (score: 6.64/10) and Ukraine as a “hybrid regime” (score: 5.9/10). Likewise, openDemocracy also highlighted that in post-Soviet countries “influence on public policy comes from expertise and connection to policy-makers and Western donors, rather than collective pressure of citizens.” (Lutsevych, 2016) It is important to note that while the Philippines is more democratic in comparison to Ukraine, it is still less democratic than many Western countries such as Canada (score: 9.22/10), Germany (score: 8.68/10), and the United States (score 7.96/10) (The Economic Intelligence, 2020). This is evidenced by the immense power the President wields during the passage of the bill. The Philippines was also more successful than Ukraine in garnering the support of its Department of Health. This is likely due to Ukraine’s frequent changes in health minister and the fact that the revenues generated from the Sin Tax was earmarked for health.

Coordination and collaboration were not seen amongst opponents of tobacco taxes in both countries as tobacco companies waged price wars with each other. Smith et al. (2013) similarly found that tobacco companies differed in their tax structure preferences (Smith et al., 2013). This lack of cohesiveness allowed tobacco tax proponents to negotiate with some of the opponents in order to facilitate the passage of the tax policies. Indeed, political scientists have long argued that cohesiveness within the policy community is a key factor for political prioritization, without which meaningful policy change will less likely take place (Sabatier, 1988; Kingdon, 1984; Shiffman and Smith, 2007). This finding suggests that tobacco tax proponents in other countries should actively seek to contribute to and/or capitalize on any potential fragmentation in the opponent coalition. It is important to note, however, that in the Philippines, Sin Tax proponents made sacrifices to the alcohol component of the Sin Tax to prevent the tobacco and alcohol industries from joining forces. This begs the question of whether or not proponents should consider advocating for tobacco and alcohol taxes separately.

While involving a diverse set of actors was critical and all actors played an important role in the process, this cross-case analysis also unveiled the importance of having respected economic groups within the coalition. In the Philippines, these groups were the Action for Economic Reform, an in-country economic think tank, and the World Bank. In Ukraine, this group was the World Bank. Given that MoF governs tax policies and, as we have seen in both cases, been traditionally more involved than MoH in pushing for tobacco taxation, these economic groups were able to engage in in-depth technical conversations with the MoF due to their expertise and facilitate access to these politicians for other groups. This finding also points to the need to boost familiarity of as well as engagement with Ministries of Health around the world on tobacco taxation.

The use of scientific evidence was also a critical component. In both Philippines and Ukraine there were experts who were monitoring and analyzing local data on a regular basis and were able to provide other proponents with timely evidence to back their arguments and counter industry frames. In the Philippines, this task was carried out by a medical doctor who was also a university professor. Similarly, in Ukraine, this expert was a tobacco control researcher. Both were from their respective countries and described by key informants as timely. While ACF also highlights the critical role experts play, it does not discuss the specific types of experts that might be helpful. The need for local data was highlighted by key informants in both countries and also emphasized in other studies that explored sugar-sweetened beverage tax policy making in the United States and the Philippines (James et al., 2020; Purtle et al., 2018). This is because proponents built models to show the health and economic impact of the tax policy. As such, the use of local data allowed for more accurate models. International experiences complemented local data as the tobacco industry uses the same arguments against raising tobacco taxes worldwide – illicit trade and regressivity (Smith et al., 2013). Accordingly, capitalizing on links with international allies was also found to be essential in both cases.

In both countries, the coalition of proponents cultivated a rigorous understanding of the political economy to identify favorable external events that can serve as key entry points. They were also well aware of which audiences needed to be convinced in order to reach their policy objectives. In both countries, decision makers were the most critical individuals for proponents to persuade as they hold power over the policy process. While the public was also important to convince, it appeared to be more important in the Philippines. This might be due to the level of openness of the policy process to public participation and the level of democracy as described above. Once key entry points were identified, proponents tailored their arguments and strategies according to their audience; this included who to select as a credible messenger. The need for credible messengers is consistent with other policy change theories, which have referred to these individuals as policy entrepreneurs “willing to invest their resources in pushing their pet proposals or problems, are responsible not only for prompting important people to pay attention, but also for coupling both problems and solutions to politics (Kingdon, 1984, p. 21).” (Kingdon, 1984) It is also consistent with grey literature on policy advocacy (Young and Quinn, 2012). These results suggest the need for advocates in other countries to recognize signs of favorable external events (e.g. regime change, crises) that can trigger subsystem instability, understand their policymaking process, and be prepared such that they can quickly seize these opportunities when they emerge.

A multi-pronged approach was used, which allowed proponents to employ different but interdependent and mutually reinforcing strategies to reach their target audience in order to achieve their policy objectives. Coalition members were given the space to use their own methods so long as the strategies were aligned and geared towards one common goal. This is consistent with other policy change theories and frameworks that underscore group cohesion as a key facilitating factor (Kingdon, 1984; Shiftman and Smith, 2007). The strategies common to both cases were included lobbying, media advocacy, as well as issue framing. One frame that emerged in both countries was that the tobacco tax policy is a health and revenue generating measure. This framing appeared to be important for attracting support from different sectors and the public, particularly in the Philippines. In fact, in the Philippines, Sin Tax proponents placed more emphasis on the health aspect of the framing. Informants explained that this helped steer the debate in the direction of health as evidence about the harms of tobacco use is so well established that it is difficult for opponents to argue against it. In both cases, opponents focused largely on economic arguments such as how raising taxes is regressive and could lead to smuggling and illicit trade. This is consistent with a systematic review conducted by Smith et al. (2013) (Smith et al., 2013) which showed that the most common frames used by the tobacco industry to counter tax increases are illicit trade, regressivity, and the negative impact on the economy. Future research should consider an interactive framing approach to explore framing contests during tobacco control advocacy battles. Studies could also be undertaken to verify the effectiveness of different frames, consider the process by which actors design different frames, and reasons for positioning the policy based on the different circumstances. It will also be important to explore whether or not framing tobacco tax policies as a health and revenue generating measure resonate more with the public compared to other frames. Koon et al. (2016) highlighted the importance of framing research and the dearth of existing literature in the LMICs on this topic (Koon et al., 2016).

In both countries, industry interference was immense and concessions occurred in both cases. The Philippines’ Sin Tax law, however, adhered to more of the guidelines within Article 6. This could be because the heads of the Ways and Means Committees in the Philippines were Sin Tax proponents, while the equivalent committee in Ukraine (Committee on Tax and Customs Policy) had stronger ties with the industry. This points to the urgent need for countries to strengthen the implementation of Article 5.3 to protect tobacco control tax policymaking from vested interests. Key informants also described certain aspects of the legislative process as opaque; this served as a major barrier for tobacco tax proponents but an advantage for the tobacco industry, underscoring the importance of policies akin to the Freedom of Information Act, which will help promote transparency, expose corruption, and preserve democracy.

6. Limitations

First, this study focuses on one public health issue in two LMICs. As such, readers should be mindful when transferring these findings to other contexts. Second, additional comparable cases are needed for causal inference; the factors identified can only be considered potential contributing rather than causal factors. Third, many of the individuals with firsthand knowledge of the policymaking process were high-level decision makers who had limited time for interviews. This is a common challenge with elite interviewing (Mikecz, 2012). Given this, we prioritized our questions, and focused more heavily on redistribution of resources and tactics, rather than beliefs. This is also because redistribution of resources is considered to be the “most important effect of external shock” (p.199)”. (Sabatier, 2007). Fourth, while efforts were made to reach out to opponents, almost all declined to participate in the study. Accordingly, the industry strategies and arguments included may not be exhaustive, and their beliefs can only be considered speculations based on available data. Lastly, only English documents were reviewed for the case of the Philippines and some Ukrainians documents were translated via Google Translate, which might have resulted in loss of some details and/or translation inaccuracies.

7. Conclusions

The Philippines and Ukraine both succeeded in passing tobacco tax policies that adhered to some of the key guidelines in Article 6 of the FCTC despite immense opposition from the tobacco industry and its affiliates. These victories came as a result of external events that shifted the balance of the policy subsystem, creating an opportunity for tobacco tax proponents. Having cultivated a rigorous understanding of the political economy, these proponents formed a multi-sectoral coalition and tailored their strategies and arguments accordingly.

These findings shed light on the utility of ACF in explaining policy change in non-Western, LMIC contexts. Results also uncovered areas that will benefit from future exploration: 1) the need for specific types of actors beyond the usual suspects including respected economics groups and experts who can generate timely evidence; 2) the use of both local and international data to convince decision makers and neutralize industry arguments; and 3) engagement in issue framing. One of the frames that emerged in both countries was that the tobacco tax policy is a health and revenue generating measure. Future studies are needed to verify the effectiveness of this frame and explore whether or not it resonates in other contexts.

Despite these victories, it is important to note that concessions were made in both cases as a result of tobacco industry interference. This underscores not only the need for persistence on the part of proponents but the urgency for countries to effectively implement Article 5.3 and consider policies akin to the Freedom of Information Act in order to enhance transparency and accountability.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This study was funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies’ Bloomberg Initiative to Reduce Tobacco Use. We would also like to acknowledge the key informants who contributed their time and expertise to this study.

Footnotes

Appendix A.: Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114001.

References

- EU-Ukraine Trade Union Committee, 2014. Association Agreement between the European Union and the European Atomic Energy Community and Their Member States, of the One Part, and Ukraine, of the Other Part. https://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2016/november/tradoc_155103.pdf.

- A pack of cigarettes in Ukraine in 2018 will rise by 4-5 UAH as a result of increased excise taxes. Interfax-Ukraine. Accessed June 24. https://interfax.com.ua/news/economic/474533.html–. (Accessed 3 January 2018).

- Alechnowicz K, Chapman S, 2004. The philippine tobacco industry: ‘the strongest tobacco lobby in Asia. Tobac. Contr 13 (Suppl. 2), ii71–i78. Suppl 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aquino Benigno III, 2011. A social contract with the Filipino people. Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/about/gov/exec/bsaiii/platform-of-government/. (Accessed 1 April 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Aungkulanon S, Pitayarangsarit S, Bundhamcharoen K, et al. , 2019. Smoking prevalence and attributable deaths in Thailand: predicting outcomes of different tobacco control interventions. BMC Publ. Health 19 (1), 984. 10.1186/s12889-019-7332-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averchuk Rostyslav, 2019. Political explainer: Ukraine’s system of government. Vox ukarine. https://voxukraine.org/cards/pravlinnya/index-en.html. (Accessed 3 March 2021). [Google Scholar]

- Breton E, Richard L, Gagnon F, Jacques M, Bergeron P, 2006. Fighting a tobacco-tax rollback: a political analysis of the 1994 cigarette contraband crisis in Canada. J. Publ. Health Pol 27 (1), 77–99. 10.1057/palgrave.jphp.3200060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breton E, Richard L, Gagnon F, Jacques M, Bergeron P, 2008. Health promotion research and practice require sound policy analysis models: the case of Quebec’s Tobacco Act. Soc. Sci. Med 67 (11), 1679–1689. 10.1016/J.SOCSCIMED.2008.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bump JB, Reich MR, 2013. Political economy analysis for tobacco control in low- and middle-income countries. Health Pol. Plann 28 (2), 123–133. 10.1093/heapol/czs049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairney P, 2007. A “multiple lenses” approach to policy change: the case of tobacco policy in the UK. Br. Polit 10.1057/palgrave.bp.4200039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaloupka FJ, Yurekli A, Fong GT, 2012. Tobacco taxes as a tobacco control strategy. Tobac. Contr 21 (2), 172–180. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhry S, Sedelius T, Kyrychenko J, 2018. Semi-Presidentialism and Inclusive Governance in Ukraine Reflections for Constitutional Reform. http://pravo.org.ua. (Accessed 3 March 2021).

- Chung-Hall J, Craig L, Gravely S, Sansone N, Fong GT, 2019. Impact of the WHO FCTC over the first decade: a global evidence review prepared for the Impact Assessment Expert Group. Tobac. Contr 28 (Suppl. 2), s119–s128. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conference of the Parties. Guidelines for Implementation of Article 6 of the WHO FCTC, 2014. http://www.who.int/fctc/guidelines/adopted/Guidelines_artide_6.pdf?ua=1. (Accessed 21 May 2018).

- Drope J, Chavez JJ, Lencucha R, McGrady B, 2014. The political economy of foreign direct investment–evidence from the Philippines. Polic. Soc 33 (1), 39–52. 10.1016/j.polsoc.2014.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt J, Lee K, 2019. The international political economy of health. In: The Palgrave Handbook of Contemporary International Political Economy. Palgrave Macmillan UK, London, UK, pp. 667–682. 10.1057/978-1-137-45443-0_41. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ekpu VU, Brown AK, 2015. The economic impact of smoking and of reducing smoking prevalence: review of evidence. Tob. Use Insights 8, S15628. 10.4137/TUI.S15628. TUI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A, Ryaboshlyk VV, Krasovsky K, Hrevtsova R, 2013. Tobacco Control in Practice Article 6: Price and Tax Measures to Reduce the Demand for Tobacco. Copenhagen, http://www.euro.who.int/_data/assets/pdf_file/0007/233368/Tobacco-Control-in-Practice-Artide-6.pdf?ua=1. (Accessed 7 November 2019).

- He Y, Shang C, Chaloupka FJ, 2018. The association between cigarette affordability and consumption: an update. In: Husain MJ (Ed.), PloS One 13 (12), e0200665. 10.1371/journal.pone.0200665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HealthJustice. Million of Lives at Stake on Tobacco Tax Reform, 2012. https://www.healthjustice.ph/?cat=2.

- HealthJustice. World Tobacco Growers Day, 2012. A Ploy against Health? https://www.healthjustice.ph/?cat=2.

- Holubeva O. European prices for Ukrainian smokers: new increasing costs of cigarettes. 112 UA. Accessed June 24, 2020. https://112.international/article/european-prices-for-ukrainian-smokers-new-increasing-costs-of-cigarettes-20692.html. (Accessed 13 September 2017). [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, 2018. Global Burden of Disease Study 2017 Results. Seattle, United States. http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/. [Google Scholar]

- James E, Lajous M, Reich MR, 2020. The politics of taxes for health: an analysis of the passage of the sugar-sweetened beverage tax in Mexico. Heal Syst Reform 6 (1), e1669122. 10.1080/23288604.2019.1669122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins-Smith HC, Nohrstedt D, Weible CM, Ingold K, 2017. The advocacy coalition framework: an overview of the research program. In: Theories of the Policy Process, fourth ed. Westview Press, Boulder, CO, pp. 135–171. 10.4324/9780429494284-5. Routledge; 2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jha P, 2009. Avoidable global cancer deaths and total deaths from smoking. Nat. Rev. Canc 9 (9), 655–664. 10.1038/nrc2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan S, VanWynsberghe R, 2008. Cultivating the under-mined: cross-case analysis as knowledge mobilization. Forum Qual Sozialforsch 9 (1), 34. 10.17169/fqs-9.1.334. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khayatzadeh-Mahani A, Breton E, Ruckert A, Labonté R, 2017. Banning shisha smoking in public places in Iran: an advocacy coalition framework perspective on policy process and change. Health Pol. Plann 32 (6), 835–846. 10.1093/heapol/czx015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingdon J, 1984. Agendas, Alternatives Public Policies, second ed. Little, Brown and Company, Boston. [Google Scholar]

- Kocijancic M, Kaznowski A, Smerilli A, 2017. EU-Ukraine association agreement fully enters into force. European Commission Press Release Database. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-17-3045_en.htm. (Accessed 2 July 2019). [Google Scholar]

- Koon AD, Hawkins B, Mayhew SH, 2016. Framing and the health policy process: a scoping review. Health Pol. Plann 31 (6), 801–816. 10.1093/heapol/czv128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasovsky KS, 2010. “The lobbying strategy is to keep excise as low as possible” - tobacco industry excise taxation policy in Ukraine. Tob. Induc. Dis 8 (10), 1–9. 10.1186/1617-9625-8-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasovsky K, 2013. Sharp changes in tobacco products affordability and the dynamics of smoking prevalence in various social and income groups in Ukraine in 2008-2012. Tob. Induc. Dis 11 (1), 21. 10.1186/1617-9625-11-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legislative Executive Development Advisory Council Secretariat, 2016. LEGISLATIVE AGENDA IN THE PHILIPPINE DEVELOPMENT PLAN 10 TH CONGRESS-16 TH CONGRESS. Manila. [Google Scholar]

- Lutsevych O. Civil society in the post-Soviet space: fighting for the “End of History” | openDemocracy. Open Democracy. Published April 20, 2016. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/openglobalrights-openpage/civil-society-in-post-soviet-space-fighting-for-end-of-history/. (Accessed 17 November 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Madore A, Rosenberg J, Weintraub R, 2015. “Sin Taxes” and Health Financing in the Philippines. Cambridge. http://www.globalhealthdelivery.org/files/ghd/files/ghd-030_philippines_tobacco_control_teaching_case.pdf. (Accessed 1 April 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Miguel-Baquilod M, Luz S, Quimbo A, et al. , 2012. The Economics of Tobacco and Tobacco Taxation in the Philippines. Paris. https://www.global.tobaccofreekids.org/assets/global/pdfs/en/Philippines_tobacco_taxes_report_en.pdf. (Accessed 22 May 2018). [Google Scholar]

- Mikecz R, 2012. Interviewing Elites. Qual Inq. 18 (6), 482–493. 10.1177/1077800412442818. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mill JS, 2016. A System of Logic, Ratiocinative and Inductive. Dinslaken: Anboco. https://catalyst.library.jhu.edu/catalog/bib_6294643. (Accessed 17 November 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health of Ukraine, 2018. Kiev international Institute of sociology, world health organization regional office for Europe, national academy of medical sciences of Ukraine, U.S. Centers for disease control and prevention. Global Adult Tobacco Survey Ukraine 2017. Kyiv. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325257431_Global_Adult_Tobacco_Survey_Report_Ukraine_2017. (Accessed 22 May 2019). [Google Scholar]

- Moon RW, Males MA, Nelson DE, 1993. The 1990 Montana initiative to increase cigarette taxes: Lessons for other states and localities. J. Publ. Health Pol 14 (1), 19. 10.2307/3342824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngalesoni F, Ruhago G, Mayige M, et al. , 2017. Cost-effectiveness analysis of population-based tobacco control strategies in the prevention of cardiovascular diseases in Tanzania. In: Doran CM (Ed.), PloS One 12 (8), e0182113. 10.1371/journal.pone.0182113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North R, 1998. Getting key players to work together and defending against diversion-Oregon. Cancer 83 (12A), 2713–2716. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panko R, 2020. Under the gun: how the Ministry of Finance can contribute to the monopolization of the cigarette market. RBC Ukraine. Accessed April 7. https://daily.rbc.ua/rus/show/pritselom-minfin-sposobstvovat-monopolizatsii-1523536448.html. (Accessed 4 December 2018). [Google Scholar]

- Paul J Earmarking Revenues for Health: A Finance Perspective on the Philippine Sin Tax Reform. [Google Scholar]

- Paul J, 2016. Philippine sin tax reform: a win-win for revenues and health. In: Winning the Tax Wars: Global Solutions for Developing Countries Conference. World Health Organization, Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- Pifer S, 2014. Poroshenko signs EU-Ukraine association agreement. Front. Times https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2014/06/27/poroshenko-signs-eu-ukraine-association-agreement/. (Accessed 2 July 2019). [Google Scholar]

- Pifer S. Five years after Crimea’s illegal annexation, the issue is no closer to resolution. Brookings. Published March 18, 2019. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2019/03/18/five-years-after-crimeas-illegal-annexation-the-issue-is-no-closer-to-resolution/. (Accessed 7 April 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Purisima C, 2012. Farmers Q&A. Manila. [Google Scholar]

- Purtle J, Langellier B, Lê-Scherban F, 2018. A case study of the Philadelphia sugar-sweetened beverage tax policymaking process. J. Publ. Health Manag. Pract 24 (1), 4–8. 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rada Verkhovna, 2018. Ukraine Law No. 2245- 19 on Amendments to the Tax Code of Ukraine and Some Legislative Acts of Ukraine on Ensuring Balance of Budgetary Revenues. https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/2246-19#Text.

- Reich MR, 2019. Political economy of non-communicable diseases: from unconventional to essential. Heal Syst Reform 5 (3), 250–256. 10.1080/23288604.2019.1609872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Republic of the Philippines Department of Health, Philippines Statistics Authority. 2009 Philippines Global Adult Tobacco Survey, 2010. Atlanta, GA. https://www.doh.gov.ph/sites/default/files/publications/2009GATSCountryReport_FinalPhilippines_0.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of the Philippines Department of Health Philippine Statistics Authority, 2011. Philippines Country Report Global Youth Tobacco Survey; 2011. Manila. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of the Philippines Department of Finance, 2020a. Sin Tax Reform. Republic of the Philippines Department of Finance. https://www.dof.gov.ph/advocacies/sin-tax-reform/. (Accessed 9 April 2020).