Abstract

Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) affords curative potential for high-risk patients but also carries risk of morbidity and mortality. Early palliative care (PC) integration can aid in supporting patients and families, fostering goal-directed care, and maximizing quality-of-life throughout. However, little is known about patient and family hopes, worries, goals or values in pediatric HCT. Through retrospective review of pre-transplant PC consultations, this study sought to provide insights from this unique patient population. Across 100 initial PC encounters conducted between December 2015 to March 2018, patient and caregiver responses to 5 targeted questions were extracted and analyzed. Data analysis revealed themes related to patient quality-of-life, caregiver/parent role, hopes, and worries. The most commonly identified thematic responses within each topic area were: patient quality-of-life- “electronics/entertainment” (49%), caregiver/parent role- “doing right by my child” (58%), hopes- “cure” (83%), worries- “potential side effects” (43%), other- spirituality (34%), and resiliency (29%). These findings provide an understanding of the values, goals, priorities, hopes, and fears experienced by pediatric HCT patients and their families, which may help inform a targeted approach to improve communication and overall care throughout transplantation. Variability was noted, underscoring the importance of fostering flexible, patient/family-centered communication beginning in the pre-transplant period.

Introduction

Early palliative care (PC) integration in high risk-oncology patients is beneficial for patients and caregivers alike.1,2,3 Despite expert recommendations that PC be introduced at diagnosis and incorporated throughout treatment,4,5,6,7,8 this practice occurs infrequently and inconsistently, especially in pediatrics.9 Due to high risk for morbidity and mortality accompanying transplantation, hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) recipients would likely benefit from early PC integration; however, the focus on cure-directed interventions and the goals of HCT may preclude or delay the integration of PC services.10 Pediatric oncology patients and their parents report quality-of-life as high-priority from the beginning of treatment and do not oppose early PC integration, even with a goal of cure.11 Early PC in HCT is gaining traction with recent data demonstrating potential benefits12,13 and innovative models of PC integration in pediatric transplantation.14

In the context of HCT, one pivotal function of the PC team is to elicit patient and family values and goals in order to assist in shared, goal-directed medical decision-making and integration of quality-of-life directed care. Little is known about the hopes, fears, values and goals of pediatric HCT patients and families. Yet, evidence demonstrates that fostering the hopes of patients and families is vital for seriously ill patients.15 Limited historical data suggest that parents of children undergoing HCT experience significant distress throughout the process, including feelings of helplessness, burnout, and depression.16 Families may fluctuate between hoping for a cure and contemplating death when facing uncertainty in childhood cancer.17 Families preparing for HCT, a high-risk therapy with curative intent, may face immense uncertainty, as well as duality of hope and fear.18 While the majority of parents of children undergoing HCT hope for cure,19 they worry about complications and negative outcomes, and may have widely variable outlooks.20

A better understanding of values, goals, priorities, hopes, and fears in pediatric HCT patients and their families may improve communication and overall care. Our study seeks to expand both the depth and scope of the existing knowledge base through qualitative analysis of patient and family perspectives elicited during routine pre-transplantation PC consults. This is the first study to utilize qualitative analysis of pre-HCT PC consultations to explore the important factors underlying the motivations and thought processes of HCT patients and families approaching transplantation.

Material and methods

Study Population

The study was designed as an exploratory qualitative retrospective cohort study of patients who received routine PC consultation prior to the start of allogeneic HCT. Records of all patients who received allogeneic HCT between December 1, 2015 and April 1, 2018 at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (St. Jude) were reviewed. After IRB approval, 112 patient charts were reviewed, and 100 (89%) patients were included in the analysis. Patients were excluded if they did not have a documented PC consultation prior to transplantation or the PC consultation note was substantively incomplete.

Data Collection

A novel model of routine tiered PC consultation12 in the pre-evaluation period was implemented for all patients presenting for allogeneic HCT at St. Jude beginning in December of 2015 (Figure 1). The consult team included at least a PC physician and nurse practitioner. The initial visit aimed to build a relationship with the family, assess patient symptoms, and develop a care plan. Patients and families were routinely asked five key targeted questions aimed to elicit their values, hopes, and fears, including: 1) “What is a good day for the patient?” 2) “What is your definition of a good parent?” 3) “What are you hoping for?” 4) “What else are you hoping for?” 5) “What are you worried about?” Families were given the opportunity to further share using the prompt: “Is there any additional information that we should know to take better care of you as a family?”. The patient and family members present received independent opportunities to answer each open-ended question. Responses and resulting discussion were paraphrased and entered into the medical record by a PC team member.

Figure 1:

Novel Model of Routine Tiered Palliative Care Integration in Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital

Research staff reviewed the electronic medical records of the HCT patients to extract: the date of PC consultation, participants present during consultation (e.g., patient, family members, PC team), patient demographics (e.g., age, gender, race, ethnicity, primary diagnosis, date of diagnosis), and transplantation characteristics (e.g., transplantation type, transplantation number, hematopoietic progenitor cell source). The pre-transplantation PC consultation note was reviewed for responses to the five key questions. Patient/family responses to each question were recorded in an Excel table. Charted terms in plural, such as “they hope,” were tabulated as family responses and not as a patient’s independent response. Additional information noted beyond the scope of the 5 targeted questions, was recorded and categorized as “other,” if present.

Analysis:

Semantic content analysis methodology21 was utilized to qualitatively analyze excerpts from patients’ medical records. Answers to the five key targeted questions, as well as “other” information, were reviewed for content familiarity. Two authors (KVN, DL) reviewed all transcripts to develop a detailed codebook for four of the five targeted questions and “other” information. For the “good parent” question, a previously developed a priori coding dictionary was utilized.22 Following codebook development, transcripts of documented responses to the five questions and “other” information were coded. Due to thematic overlap, “what are you hoping for” and “what else are you hoping for” were combined and coded as one question. Researchers (KVN, DL) reviewed codes independently. When disparate, a third coder (JB) aided in achieving consensus to arrive at a final code assignment. Each code was applied once within a given patients’ response segment and frequencies of codes represent thematic content in each topic area per patient/family. Descriptive statistics were utilized to describe the characteristics of the study population. All responses in the PC consult notes were imported into MAXQDA, a qualitative analysis software. Using MAXQDA software, code frequencies for each question were calculated. Graphs illustrating the frequencies were created in excel.

Results

Demographics

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the patients included in this study (n=100). The mean age of patients at the time of PC consult was 9.5 years (range 0-21, median 10). Most patients received HCT as therapy for leukemia (AML 47%; ALL 24%), of which 9 cases were a secondary leukemia. Twenty-one children had previously undergone HCT. Most PC consultations included the patient (97%) and at least 1 parent (93%). In other instances, a grandparent, significant other, or another family member was present for the PC consultation instead of, or in addition to, the parent. The average number of days between PC consultation and HCT cellular infusion was 22 days (range 6-141 days).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics and Demographics

| Patient Demographics (n = 100) | |

|---|---|

| Age at PC consult | Number (%) |

| 0-4 years | 31 |

| 5-10 years | 21 |

| 11-15 years | 29 |

| 16 years and older | 19 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 63 |

| Female | 37 |

| Race | |

| White | 77 |

| African American | 15 |

| Asian American | 4 |

| Multiracial | 3 |

| American Indian/Alaskan | 1 |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 32 |

| Non-Hispanic | 68 |

| Primary Diagnosis | |

| AML | 46 |

| ALL | 24 |

| Aplastic Anemia | 6 |

| SCID | 3 |

| Lymphoma | 4 |

| Myelodysplastic Syndrome | 2 |

| Sickle Cell | 2 |

| Other | 5 |

| Multiple Diagnosis | 8 |

| Donor Source | |

| Haploidentical Donor | 50 |

| Matched Sibling Donor | 19 |

| Matched Unrelated Donor | 31 |

| History of prior transplant | |

| Yes | 21 |

| No | 79 |

Item-Specific Analyses

“Good Day”

The majority of HCT patients had recorded patient/family responses to the “what is a good day for the patient?” question in the pre-transplant PC consult note (n=98). A total of 10 codes created during codebook development were utilized for semantic content analysis (Table 2). The most frequent “good day” code identified was “electronics/entertainment” (50%). “Being active” (46.9%), “toys/books” (35.7%), “quality time with loved ones” (30.6%) and “overall well-being” (26.5%) were identified in over a quarter of patients/families as contributors to patient quality-of-life. Other “good day” codes included creative art (24.5%), music/dance (19.4%), food (18.4%), relaxation (11.2%), and education (10.2%).

Table 2.

Good Day: Codes, Definitions, Frequencies and Sample Content for the question/prompt - “What is a good day for the patient?”

| Code | Definition | Families Reporting (n=98) | Sample Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relaxation | not having required activities; being allowed to rest; state of being calm | 11 (11.2%) | Doing nothing, hanging out, chilling, sleeping |

| Electronics / Entertainment | any electronic game including those on the computer, X-box, PlayStation, phone, or other gaming device; watching any form of video; spending time on the internet | 49 (50%) | Electronics, playing games on the phone, likes playing X-box or PlayStation, watching Netflix, watching videos on YouTube, favorite movies/TV shows, online shopping |

| Toys/Books | any object that a child could play with including but not limited to dolls, action figures, games, Legos, and cars; spending time reading | 35 (35.7%) | Stuffed animals, princess dolls, baby dolls, puzzles, board games, miniature figures, reading |

| Music/Dance | listening to music, singing songs, and playing instruments; moving rhythmically to music; following a pattern of movements | 19 (19.4%) | Singing, music, loves playing guitar and piano, ballet or jazz dancing, twirling a baton, using ribbons in dance |

| Creative Art | using creative skills and imagination to make various things; an interest in clothing and makeup | 24 (24.5%) | Crafts, coloring, painting, drawing, making jewelry, sewing, play dough, painting nails, loves fashion |

| Education | having the opportunity to learn; spend time in the classroom; gaining knowledge | 10 (10.2%) | Likes school, loves learning new languages, interested in a scientific field, science experiments, wanting to go to graduate school |

| Overall well-being | a general state of contentment; being happy; feeling well; being out of the hospital | 26 (26.5%) | Pain free, feeling good in his or her body, feeling happy, cheerful, being able to be independent, out of the hospital |

| Being active | any physical activity done for enjoyment; being able to play; spending time outdoors; exercising; going places; doing things on your own | 46 (46.9%) | Staying active, playing sports, exerting oneself, playing outside, keeping busy, riding a bike, lifting weights, playtime, loves to travel, gardening |

| Quality time with loved ones | being with friends, family, or pets; doing activities with important people in your life; being at home; family outings | 30 (30.6%) | Enjoys talking to friends, being outside with friends, going to the zoo, family adventures, family time, homebodies, playing with siblings, being together, playing with their pets |

| Food | making and consuming favorite foods | 18 (18.4%) | Enjoys cooking, eating is a favorite pastime, loves food |

Most frequent characterizations of a “good day” for young children, ages 0-4, included “being active” (n=18/28,64.3%) and “toys/books” (n=13/28,46.4%), while the most common response for all other age groups included “electronics/entertainment” (ages 5-10 n=13/21,61.9%, 11-15 n=21/28,43.6%, 16-21 n=9/19,47.4%). Characterizations of a “good day” also frequently included “creative art” for children ages 5-10 (n=13/21,61.9%) and “being active” for patients ages 16-21 (n=9/19,47.4%).

Female patients more commonly reported “ creative art” as characterization of a “good day” (female n=18/36,50%, male n=6/62,9.7%) as well as “music/dance” (female n=11/36,30.6%, male n=8/62,12.9%), while male patients more commonly reported “electronics/entertainment” (female n=13/36,36.1%, male n=36/62,58%) and “being active” (female n=14/36,38.9%, male n=32/62,51.6%). Approximately 40% of both male and female “good day” characterizations included “quality time with loved ones” (female n=14/36,38.9%, male n=25/62,40.3%) and greater than a third of both group’s responses included “toys/books” (female n=12/36,50%, male n=23/62,10%).

“Good Parent”

Ninety charts had a response recorded for the question: “What is your definition of a good parent?”. Data was missing from 10 records because the consult did not include a parent/guardian, or the PC clinician deemed the question to be inappropriate due to family dynamics. A codebook of 8 codes was utilized for semantic content analysis of the “good parent” question (Table 3). The code, “Doing right by my child” (64.4%) was identified most commonly in their definition of a good parent. Most families also indicated that “being there for my child” (54.4%), and “conveying love to my child” (43.3%) were important characteristics of a good parent. Other “good parent” codes included “being a good life example” (18.9%), “being an advocate for my child” (15.6%), “making my child healthy” (15.6%), “letting the lord lead” (10%), and “not allowing suffering” (8.8%).

Table 3.

Good Parent: Codes, Definitions, Frequencies and Sample Content for the question/prompt - “What is your definition of a good parent?”

| Code* | Definition* | Families Reporting (n=90) | Sample Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| Doing right by my child | Making prudent decisions in best interest of child (even when parent would prefer different course) after weighing all options; meeting basic needs (ie. clothing, food, education) in unselfish way that may require sacrifices | 58 (64.4%) | Ensuring your child is okay, taking care of your child’s body, making sure all needs are met, keeping your children out of trouble, doing everything for your child, making sacrifices, doing what needs to be done, putting the child first |

| Being there for my child | Always at child’s side and supportive regardless of challenges; knowing at all times which activities child is engaged in and with whom | 49 (54.4%) | Giving time, showing up, constantly playing with their child, listening |

| Conveying love to my child | Demonstrating to child by actions and words how cherished child is, even under difficult circumstances; focusing on child’s quality-of-life and happiness | 39 (43.3%) | Loving whole-heartedly, showing love, soothing your child, reassuring, being there for child to lean on, offering a nurturing and loving environment, keeping their child happy |

| Being a good life example | Trying to live life that teaches child to behave in positive ways, know right and wrong, make good choices, be respectful of others, and show sympathy to others | 17 (18.9%) | Setting a good example, teaching your child how to make decisions and choices, teaching children right from wrong |

| Being an advocate for my child | Knowing what child wants and alerting staff to those wants; involving staff in care that parent is unable to perform; trying to stay focused on meeting child’s needs at all times | 14 (15.6%) | Fights hard for their child, sensing something might be wrong |

| Letting the lord lead | Bringing child up to know God and find comfort in his constant presence; letting child know that parent prays for child every day | 9 (10%) | teaching your child to love God |

| Not allowing suffering | Trying to prevent care that causes child to suffer but may not benefit child; wanting child to be able to die with dignity | 8 (8.8%) | making their child feel better, easing sadness or pain |

| Making my child healthy | Helping child to be as healthy as possible and to function as normally as possible for as long as possible | 14 (15.6%) | doing whatever she must to fight for a cure, worrying about child’s health, attuned to child’s illness, proactive about child’s care |

“Hopes”

All 100 families reported at least one hope in their pre-transplant PC consult. A codebook of 7 codes was used for semantic content analysis (Table 4). “Cure” was identified as the most common of the family’s hopes for transplantation (83%). Many families also reported hopes for “few side effects/complications” (36%), “rapid recovery/return home” (30%), and “easy transplant” (33%). Families identified other hopes: “regain health” (26%), “return to normalcy” (22%), and “family well-being” (5%). In 28 of the pre-transplant consults, the child was recorded as providing their own distinct hope. Of these, the most common responses were “return to normalcy” (32.1%) as opposed to parents/caregivers whose most common hope was “cure” (78%). Table 4 details the codes used during the content analysis of both hope questions as reported by the family overall, parent/caregiver, and patient.

Table 4.

Hopes: Codes, Definitions, Frequencies and Sample Content for the question/prompt - “What are you hoping for?” & “What else are you hoping for?”

| Code | Definition | Family Overall (n=100) | Parent (n=100) | Patient (n=28) | Sample Content |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cure | cancer free; disease will be gone; an end to being sick; complete recovery or remission; treatment gets rid of cancer; the patient will be healed | 83 (83%) | 78 (78%) | 7 (25%) | Cured, disease completely gone, cancer free, things will be okay, overcoming disease, sickness goes away, treatment is effective/works |

| Return to Normalcy | getting back to the patient’s and/or family’s typical state and previous life activities | 22 (22%) | 17 (17%) | 9 (32.1%) | Going back to school, playing sports again, getting back to a normal life, being a normal kid |

| Regain Health | A freedom from illness, cancer complications, and disability; the body getting better or healing | 26 (26%) | 23 (23%) | 3 (10.7%) | Free of complications, no long-term problems, active, no more hospital visits, never having to do treatment again, going home without cancer |

| Rapid recovery / return home | returning to a healthy state quickly; minimal time with complications associated with cancer or treatment; leaving the hospital shortly after transplant; returning to and reuniting as a family | 30 (30%) | 24 (24%) | 6 (21.4%) | Treatment going quickly, feeling better fast, full and complete healing, getting out of hospital, reuniting with family, getting treatment over with, going home |

| Few side effects / complications | the avoidance of symptoms including but not limited to pain, nausea, fever, or infections during the treatment process; feeling well throughout transplant; minimizing adverse reactions/complications | 36 (36%) | 32 (32%) | 5 (17.9%) | Not getting too sick, feeling good, not getting worse, few complications, pain free, not attached to machines, not intubated, no GVHD, successful engraftment |

| Easy transplant | Minimal complications; unremarkable hospital stay; gentle and successful transplant; keeping a regular routine and/or regular activities throughout transplant | 33 (33%) | 28 (28%) | 7 (25%) | Smooth transplant process, everything goes well, it is not too bad, uneventful time, hopes for art activities during transplant, wanting to be a part of routine to minimize change |

| Family wellbeing | Wanting the best for the family, financially providing for family, fortitude to withstand transplant as a family | 5 (5%) | 3 (3%) | 2 (7.1%) | Family being safe and healthy, staying on their feet, financial stability, hoping to get a VISA to work in the country, maintaining strength |

“Worries”

Ninety-five consult notes contained recorded responses to the question “What are you worried about?”, with 22 additional recorded distinct patient worries. 7 codes were used for semantic content analysis (Table 5). Concern about potential “side effects/complications” was the most commonly reported worry (45.3%). Other worries overall included “family impact” (26.3%), “transplant process/uncertainty” (22.1%), “bad outcome” (17.9%), and “ability to return to normalcy” (7.4%). 28.4% of families reported “no worries” during the pre-HCT PC visit, while 15.8% reported “many worries”. Compared to patients, parents/caregivers more commonly reported “many worries” (parent/caregiver 14.7%, patient 4.5%), “family impact” (parent/caregiver 25.3%, patient 4.5%) and “bad outcome (parent/caregiver 17.9%, patient 4.5%), while patients were more concerned with “ability to return to normalcy” (parent/caregiver 4.2%, patient 13.6%) and “side effects/complications” (parent/caregiver 33.7%, patient 50%). Table 5 details the codes used during the content analysis to identify worries as reported by the family overall, parent/caregiver, and patient.

Table 5.

Worries: Codes, Definitions, Frequencies and Sample Content for the question/prompt-“What are you worried about?”

| Code | Definition | Family Overall (n=95) | Parent (n=95) | Patient (n=22) | Sample Content |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Worries | no concerns, fears, apprehensions regarding transplant process | 27 (28.4%) | 19 (20%) | 8 (36.4%) | No worries, no specific concerns, not worried, not nervous |

| Many Worries | having too many worries to name them all; being apprehensive about everything | 15 (15.8%) | 14 (14.7%) | 1 (4.5%) | Worried about everything, nervous enough for both of them, normal worries, worried about many things and don’t know where to start |

| Family Impact | how the disease has and will affect the both immediate and extended family members; negative effect on family; separation from family; disruption of family unit; financial impact on family | 25 (26.3%) | 24 (25.3%) | 1 (4.5%) | Not being together, struggling to give equal time to all children, not being able to stay with the patient, worried about mother who is sick, worried about sister’s feelings if transplant fails, concerned about money, not being able to work |

| Bad Outcome | cancer returning; transplant is not successful; rejection of donor cells; patient never going into remission; failure of engraftment; fear of death | 17 (17.9%) | 17 (17.9%) | 1 (4.5%) | Treatment not working, cancer coming back, not getting better, not wanting to die, worried patient would view dying as letting his parents down |

| Side Effects / Complications | specific complications associated with transplant including negative physical or emotional symptoms, pain, distress, or hardship; fear of invasive, painful procedures | 43 (45.3%) | 32 (33.7%) | 11 (50%) | Worried about symptoms, afraid of having an NG tube, risk of infection, worried about GVHD, not wanting to be intubated, worried about misery associated with transplant |

| Transplant Process / Uncertainty | stress about any aspect of the transplant process; concern regarding following the rules of transplant; not knowing what to expect; feeling isolated | 21 (22.1%) | 19 (20%) | 4 (18.2%) | Worried about entire treatment process, unknowns, difficulty being away from friends, forced to remain in hospital room for extended amount of time |

| Ability to Return to Normalcy | concerns about how transplant will affect getting back to their daily life; concerns about falling behind educationally | 7 (7.4%) | 4 (4.2%) | 3 (13.6%) | Not getting back to normalcy, having to make changes to accommodate the patient’s needs, concern regarding intellectual development, being away from school |

“Other”

For 81 families, additional information was noted in the pre-transplant PC consult categorized as “other” or as a response to the question; “Is there any additional information that we should know to take better care of you as a family?”. A codebook of 10 codes was created for semantic content analysis (Table 6). Coping mechanisms were identified as the most common theme. Codes were categorized as positive and negative coping mechanisms. “Spirituality” (42%), “resiliency” (35.8%), and “positive attitude” (22.2%) were the most commonly identified positive coping mechanisms. “Negative past experiences” was identified as the most common factor for negative coping. (11.1%).

Table 6.

Other: Codes, Definitions, Frequencies and Sample Content for other information thematically categorized as factors leading to positive or negative coping

| Code | Definition | Family Reporting (n=81) | Sample Content | Theme |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Support System | surrounded by people, family, or friends that provide emotional or physical support to make the difficult times easier | 10 (12.3%) | Supportive family, having friends to support them, very close family who will be supportive through this time | Positive Coping |

| Spirituality | religious principles, a belief in divine forces, a higher power; supportive spiritual community; finding strength through religion/spirituality | 34 (42%) | Trusting the Lord, God gives them the strength to make it through, prayer is a way to cope, leaving it in God’s hands, faith is important, divine intervention; belief that higher power will heal the patient, supportive church community | Positive Coping |

| Positive Attitude | marked by optimism; using jokes, laughter, and comedy to handle situations; choosing to ignore or create an alternate explanation of a difficult situation | 18 (22.2%) | Not focusing on the negative, smiling no matter what happens, positive outlook, hopefulness; being goofy/silly, making light of situations, decided to think of their inpatient stay as a trip to MARS for 40 days and 40 nights, act as if he doesn’t have a disease | Positive Coping |

| Resiliency | overcoming obstacles; the ability to recover quickly from hardship; determination and inner fortitude; anticipating needs for times ahead; recognition of the reality of the situation while remaining hopeful for cure | 29 (35.8%) | Able to bounce back, focusing on problems as they come, taking it one day at a time, strong willed, brave, just dealing with it, finding strength from the patient; planning ahead; understanding risks and complications of transplant but believing their child will not have those problems | Positive Coping |

| Positive Past Experiences | relying on past experiences to find strength through future difficult situations; being in a similar situation allows the family to find peace or reduce anxiety | 6 (7.4%) | Knowing what to expect, no worries because second transplant, feeling prepared, never knowing anything different | Positive Coping |

| Negative Past Experiences | past experiences contributing to fear and poor coping with similar difficult situations | 9 (11.1%) | Difficult previous transplant, serious complications in previous treatment, stress and anxiety surrounding second transplant | Negative Coping |

| Lack of Support | isolated from support system during treatment making it harder to handle difficult situations | 3 (3.7%) | Loss of support, no family members close, feeling alone | Negative Coping |

| Lack of Positive Attitude | focusing on the negative; not being a positive person | 3 (3.7%) | Negative outlook | Negative Coping |

| Insecurity | uncomfortable about self because of illness | 1 (1.2%) | Shy, self-conscious | Negative Coping |

| Decisional Doubt | wondering if transplant was the right option; second guessing the decision for transplant | 8 (9.9%) | Should we have done this, the decision was very difficult, is transplant really needed, worries that side effects outweigh the benefits | Negative Coping |

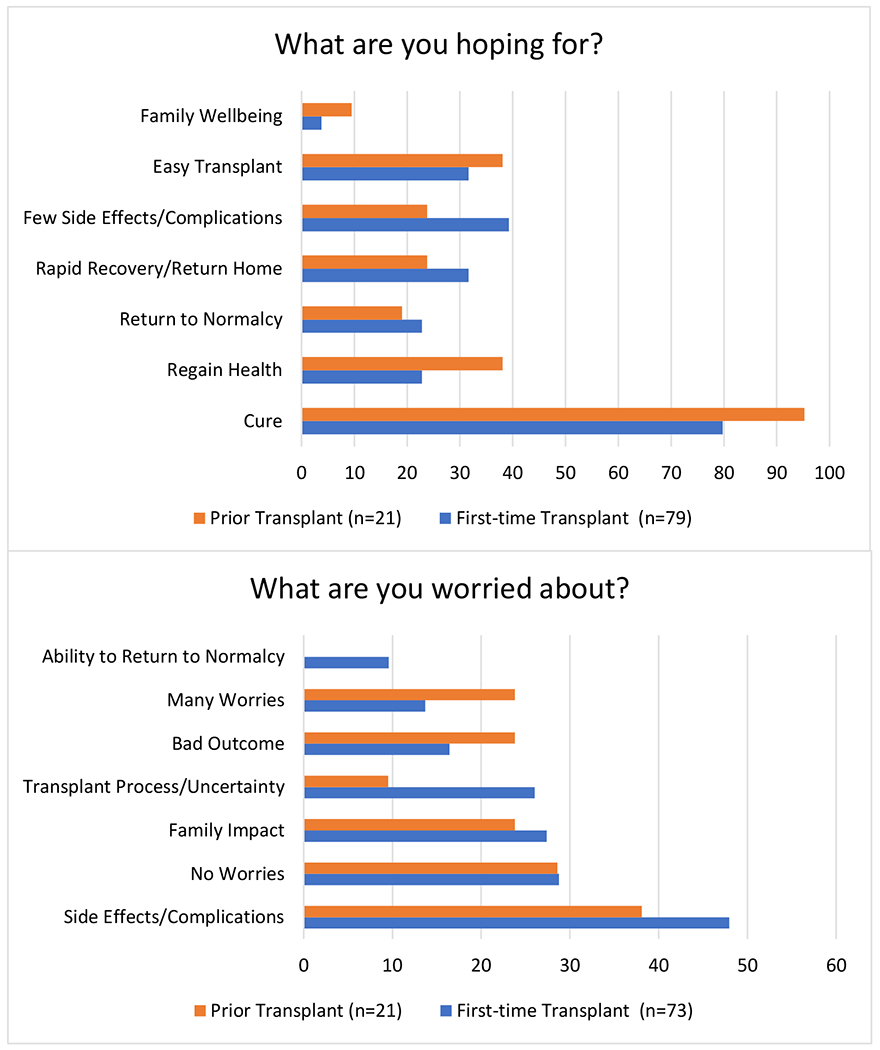

Role of prior transplantation history

Twenty-one patients had previously undergone HCT and were approaching subsequent transplantation. Irrespective of prior HCT history, families most frequently reported a hope for “cure” (first HCT 79.7%, repeat HCT 95.2%).Families of patients who had undergone prior transplantation reported some differences in their prevalent secondary hopes as compared with families of first HCT patients, with repeat HCT families most frequently reporting hopes for an “easy transplant” (38.1%) and to “regain health” (38.1%), while families of first HCT patients most frequently reported hopes for “few side effects/complications” (39.2%), “rapid recovery/return home” (31.6%) and “easy transplant” (31.6%). Regarding worries, all families expressed most concern about “side effects/complications” (first HCT 47.9%, repeat HCT 38.1%). Families of first HCT patients were more concerned about the transplant process/uncertainty, compared to families of patients with prior HCT (26.0% and 9.5%, respectively). As compared to families preparing for first HCT, families of prior HCT patients expressed higher rates of “many worries” (first HCT 13.7%, repeat HCT 23.8%) and worrying about a “bad outcome” (first HCT 16.4%, repeat HCT 23.8%). Differences between the hopes and worries of these two patient populations are illustrated in figure 2.

Figure 2:

Comparison of patient/family hopes and worries for patients with a history of prior Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation and those preparing for first Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation (expressed as percentages)

Discussion

A pivotal role of the PC team is to elicit family hopes, worries, and central values through open communication to meet the physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual needs of patients and families. HCT patients can benefit from PC integration in all areas, ranging from routine care coordination to end-of-life care. HCT patients, who do not survive, often die while receiving aggressive medical interventions23 in the absence of PC or hospice services.19 Parents of deceased HCT patients report feeling less prepared for their child’s death and suffer worse bereavement outcomes, as compared to parents of pediatric oncology patients who have not undergone HCT.24,25 Adult HCT research has shown that integration of PC prior to the start of transplantation results in improved quality-of-life and decreased depression, anxiety, and symptom burden for patients.13, 14 However, limited data exists on outcomes of PC integration in HCT, demonstrating further research is needed.26 PC integration into the care of HCT patients and families can provide additional support for HCT families and teams alike.

Because of the significant toll of transplantation, understanding a patient’s conception of a “good day” may enhance patient and family quality-of-life during and after HCT. Defining a “good day” as a quality-of-life measure for children and adolescents in active cancer treatment has been shown to be feasible and valid.27,28 Prior studies of adolescents undergoing cancer therapy found quality-of-life to be characterized by a sense of well-being and ability to participate in usual activities and relationships.27 A longitudinal study of the “good day” metric in children and adolescents ages 8-18 revealed normalcy to be paramount, with performing usual activities, playing, spending time with friends and being active as common themes.28 Our study is unique in its inclusion of infants and younger children for whom family members offered “good day” definitions, as well as the timepoint of query as families prepared for a long inpatient HCT stay. Despite these differences, our findings resemble prior studies, demonstrating quality-of-life characterizations including ability to participate in usual activities, overall well-being, and time with family and friends.27,28 While common themes can be found, clinicians must consider variability amongst individuals and over time, and should proactively explore each patient’s “good day” concept at multiple time points to provide optimal individualized care.

Understanding a family’s definition of a “good parent” can elucidate their beliefs and values, which may play a role in decision-making.22 Similar to “good parent” findings in parents of children with advanced stage cancer,22 we found that parents of patients undergoing HCT have “good parent” conceptions with predominant themes of “doing right by my child”, followed by “being there for my child” and “conveying love to my child”. Research has demonstrated that these beliefs may change over time,29 and as such clinicians should assess these perceptions at multiple time points across the illness trajectory. Better understanding the caregiver’s definition of a “good parent” may enhance anticipatory guidance and empower caregivers to foster partnership and mitigate stress. Further, parental values may strongly influence the beliefs and values of their children, thus insight into “good parent” beliefs may enable clinicians to create enhanced therapeutic partnerships with pediatric patients and caregivers alike.

Every family in our study shared hopes in the pre-transplant PC consult, suggesting that families wish to discuss hopes with their care team. In our study, families most often expressed hope for cure, which is similar to previous research of parents of children with advanced cancer.30 HCT often represents a potentially curative option for patients that have failed previous treatment options; therefore, it is not surprising that families remain hopeful for cure. The theme resonates in a statement from a patient’s medical record: “Their ultimate hope is that [they] get to keep him.” While families may hope for cure, they may have other prominent hopes as well. Similar to the observed hopes for both cure and minimal side effects in our study, many concurrently prioritize cure and comfort.30,31. In utilizing the prompts: “what are you hoping for” and “what else are you hoping for?” we acknowledged the existence of many hopes.32 Our findings underscore the importance of asking patients and families about all their hopes. If the clinical team attempts to understand a family’s hopes, they can better provide ongoing goal-directed care aligned with their hopes.33

Children who provided distinct hopes in this study most often expressed hopes for returning to normalcy, quick recovery, and return home. While both children and parents reported worrying most about potential side effects/complications, parents were more likely to express concern about the impact of HCT on the family. These findings mirror previous research demonstrating that children are often more concerned with the “here and now” while parents focus on the long-term.34 Our findings demonstrate that pediatric patients may have different worries than their parents/caregivers, thus including children in these discussions is vital. Knowing the child’s specific worries can help clinicians tailor communication, foster partnership, and individualize treatment planning.

Our study revealed differences between families of patients who had previously undergone HCT and those preparing for their first transplant. Families of patients undergoing repeat HCT expressed hope for an easy transplant and to regain health, while families of first time HCT patients commonly expressed hope for minimal side effects. Families of first-time HCT patients voiced worries about uncertainty and transplant process, while repeat HCT patients and families more commonly reported “many worries” and concern for a “bad outcome.” These findings highlight that when patients and families have experienced a process before, they may feel more prepared and struggle less with uncertainty, but their prior experience can heighten anxiety. Individualized anticipatory guidance and pre-emptive discussions is critical, as each HCT experience and patient/family is unique.

While our study demonstrates common themes in our HCT patients and families, we also observed wide variability. Prior published research in pediatric HCT has also shown parental outlook findings to be variable and unpredictable.20 Clinicians should explore family perspectives prior to HCT using an individualized approach and continually assess these perspectives to build therapeutic alliance and optimize quality-of-life.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Retrospective data extraction inherently precludes assessment beyond descriptive associations. Moreover, documentation in the medical record may not comprise complete or accurate representation of what patients and families verbalized in consultations. Additionally, families may not be fully forthcoming in sharing their perspectives in the PC consult, leading to under-reporting. Furthermore, this study gathered information from responses to open-ended questions thus, lack of specific themes only indicates the patient/family did not share that sentiment; however, they might have done so if directly queried. Despite these limitations, profound value lies in the analysis of open-ended patient/family responses to questions about their hopes, fears, values, and goals.

Conclusions

At the threshold of HCT, pediatric patients and their families exhibit a range of concurrent hopes, goals, and fears, with demonstrated commonality and variability. Individually exploring topics with both patients and caregivers, which may heavily influence their goals and motivations, can enable the provision of optimal patient and family centered care. PC integration, particularly if initiated early and maintained throughout the HCT process, can facilitate foundational understanding of patient and family hopes, fears, and values, forming the basis for HCT team and family partnerships through relationship-based care.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Wolfe J, Grier HE, Klar N, Levin SB, Ellenbogen JM, Salem-Schatz S, et al. Symptoms and suffering at the end of life in children with cancer. N Engl J Med 2000; 342: 326–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolfe J, Hammel JF, Edwards KE, Duncan J, Comeau M, Breyer J, et al. Easing of suffering in children with cancer at the end of life: Is care changing? J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 1717–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, et al. Early Palliative Care for Patients with Metastatic Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2010; 363(8): 733–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, Abernethy AP, Balboni TA, Basch EM, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology Provisional Clinical Opinion: The Integration of Palliative Care into Standard Oncology Care. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30(8): 880–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris MB. Palliative Care in Children with Cancer: Which Child and When? J Natl Cancer Inst Monographs 2004; 32: 144–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mack J, Wolfe J Early integration of pediatric Palliative Care for some children, Palliative Care starts at diagnosis. Curr Opin Pediatr 2006; 18(1): 10–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Bioethics and Committee on Hospital Care. Palliative Care for Children. Pediatrics 2000; 106(2): 351–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldman A, Heller KS. Integrating Palliative and Curative Approaches in the Care of Children with Life-Threatening Illnesses. J Palliat Med 2000; 3(3): 353–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnston DL, Nagel K, Friedman DL, Meza JL, Hurwitz CA, Friebert S. Availability and use of Palliative Care and end-of-life services for pediatric oncology patients. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 4646–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung HM, Lyckholm LJ, Smith TJ. Palliative Care in BMT. Bone Marrow Transplant 2009; 43: 265–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levine DR, Mandrell BN, Sykes A, Pritchard M, Gibson D, Symons HJ, et al. Patients’ and Parents’ Needs, Attitudes, and Perceptions About Early Palliative Care Integration in Pediatric Oncology. JAMA Oncol 2017; 3(9): 1214–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Jawahri A, LeBlanc T, VanDusen H, Traeger L, Greer JA, Pirl WF, et al. Effect of Inpatient Palliative Care on Quality of Life 2 Weeks After Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2016; 316(20): 2094–2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El-Jawahri A, Traeger L, Greer JA, VanDusen H, Fishman SR, LeBlanc TW, et al. Effect of Inpatient Palliative Care During Hematopoietic Stem-Cell Transplant on Psychological Distress 6 Months After Transplant: Results of a Randomized Clinical Trial. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35(32): 3714–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levine DR, Baker JN, Wolfe J, Lehmann LE, Ullrich C. Strange Bedfellows No More: How Integrated Stem Cell Transplant and Palliative Care Programs Can Together Improve EOL Care. J Oncol Pract 2017; 13(9): 569–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clayton J, Butow P, Arnold R, Tattersall M. Fostering Coping and Nurturing Hope When Discussing the Future with Terminally Ill Cancer Patients and Their Caregivers. Cancer 2004; 103(9): 1965–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oppenheim D, Valteau-Couanet D, Vasselon S, Hartmann O. How do parents perceive high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation for their children. Bone Marrow Transplant 2002; 30(1): 35–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Graves S, Aranda S. Living with hope and fear--the uncertainty of childhood cancer after relapse. Cancer Nurs 2008; 31(4): 292–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forinder U Bone marrow transplantation from a parental perspective. J Child Health Care 2004; 8(2): 134–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ullrich CK, Dussel V, Hilden JM, Sheaffer JW, Lehmann L, Wolfe J. End-of-life experience of children undergoing stem cell transplantation for malignancy: parent and provider perspectives and patterns of care. Blood 2010; 115(19): 3879–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ullrich CK, Rodday AM, Bingen K, Kupst MJ, Patel SK, Syrjala KL, et al. Parent Outlook: How Parents View the Road Ahead as They Embark on Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation for Their Child. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016; 22(1): 104–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krippendorff K Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology, 3rd edn. Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hinds PS, Oakes LL, Hicks J, Powell B, Srivastava DK, Spunt SL, et al. “Trying to Be a Good Parent” As Defined By Interviews With Parents Who Made Phase I, Terminal Care, and Resuscitation Decisions for Their Children. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27(35): 5979–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Snaman JM, Talleur AC, Lu J, Levine DR, Kaye EC, Sykes A, et al. Treatment intensity and symptom burden in hospitalized adolescent and young adult hematopoietic cell transplant recipients at the end of life. Bone Marrow Transplant 2018; 53(1): 84–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jalmsell L, Onelov E, Steineck G, Henter JI, Kreicbergs U. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in children with cancer and the risk of long-term psychological morbidity in the bereaved parents. Bone Marrow Transplant 2011; 46(8): 1063–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drew D, Goodenough B, Maurice L, Foreman T, Willis L. Parental grieving after a child dies from cancer: is stress from stem cell transplant a factor? Int J Palliat Nurs 2005; 11(6): 266–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.El-Jawahri A, Temel JS. Palliative Care Integration in Hematopoietic Stem-Cell Transplantation: The Need for Additional Research. J Oncol Pract. 2017; 3(9): 578–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hinds PS, Gattuso JS, Fletcher A, Baker E, Coleman B, Jackson T,et al. Quality of Life as conveyed by pediatric patients with cancer. Qual Life Res 2004; 13(4): 761–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Momani TG, Mandrell BN, Gattuso JS, West NK, Taylor SL, Hinds PS. Children’s perspective on health-related quality of life during active treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia: an advanced content analysis approach. Cancer Nurs 2015; 38(1): 49–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hill DL, Faerber JA, Li Y, Miller VA, Carroll KW, Morrison W, et al. Changes Over Time in Good-Parent Beliefs Among Parents of Children with Serious Illness: A Two-Year Cohort Study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2019; 58(2): 190–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kamihara J, Nyborn JA, Olcese ME, Nickerson T, Mack JW. Parental Hope for Children with Advanced Cancer. Pediatrics 2015; 135(5): 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolfe J, Klar N, Grier HE, Duncan J, Salem-Schatz S, Emanuel EJ, et al. Understanding of prognosis among parents of children who died of cancer: impact on treatment goals and integration of palliative care. JAMA 2000; 284(19): 2469–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feudtner C The breadth of hopes. N Engl J Med 2009; 361(24): 2306–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hill DL, Nathanson PG, Carroll KW, Schall TE, Miller VA, Feudtner C. Changes in Parental Hopes for Seriously Ill Children. Pediatrics 2018; 141(4): 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brand SR, Fasciano K, Mack JW. Communication preferences of pediatric cancer patients: talking about prognosis and their future life. Support Care Cancer 2017; 25(3): 769–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]