Abstract

Introduction

Although paramedicine is an integral element of healthcare systems, there is a lack of universal consensus on its definition. This study aimed to derive a global consensus definition of paramedicine.

Methods

Key attributes pertaining to paramedicine were identified from existing definitions within the literature. Utilising text analysis, common attribute themes were identified and six initial domains were developed. These domains formed the basis for a four-round Delphi study with a panel of 58 global experts within paramedicine to develop an international consensus definition.

Results

Response rates across the study varied from 96.6% (round 1) to 63.8% (round 4). Participant feedback on appropriate attributes to include in the definition reflected the high level of specialized clinical care inherent within paramedicine, and its status as an essential element of healthcare systems. In addition, the results highlighted the extensive range of paramedicine capabilities and roles, and the diverse environments within which paramedics work.

Conclusion

Delphi methodology was utilized to develop a global consensus definition of paramedicine. This definition is as follows: paramedicine is a domain of practice and health profession that specialises across a range of settings including, but not limited to, emergency and primary care. Paramedics work in a variety of clinical settings such as emergency medical services, ambulance services, hospitals and clinics as well as non-clinical roles, such as education, leadership, public health and research. Paramedics possess complex knowledge and skills, a broad scope of practice and are an essential part of the healthcare system. Depending on location, paramedics may practice under medical direction or independently, often in unscheduled, unpredictable or dynamic settings. We believe that the generation and provision of this consensus definition is essential to enable the further development and maturation of the discipline of paramedicine.

Keywords: allied health personnel, consensus, Delphi study, paramedicine

Plain Language Summary

The discipline of paramedicine continues to advance and mature, however, there is a lack of consensus on its definition.

This study aimed to derive a global consensus definition of paramedicine.

The research team used a Delphi process that sought feedback from worldwide discipline experts over four rounds of questionnaires, enabling definition development.

The definition is: Paramedicine is a domain of practice and health profession that specialises across a range of settings including, but not limited to, emergency and primary care. Paramedics work in a variety of clinical settings such as emergency medical services, ambulance services, hospitals and clinics as well as non-clinical roles, such as education, leadership, public health and research. Paramedics possess complex knowledge and skills, a broad scope of practice and are an essential part of the healthcare system. Depending on location, paramedics may practice under medical direction or independently, often in unscheduled, unpredictable or dynamic settings.

We believe that the adoption of the proposed definition is a vital step in the unification, collaboration and further development of the discipline of paramedicine.

Introduction

Globally over the last few decades, the discipline of paramedicine has evolved from a vocation that exclusively responded to emergencies and transferred patients to hospital, to an autonomous out-of-hospital profession with an extensive scope of evidence-based practice.1,2 A key step that has contributed to this progression, and indeed will need to keep progressing, is the growth of a domain of practice and a unique body of knowledge.3 An additional element accompanying these changes within paramedicine is the increasing movement towards professional regulation and registration worldwide,4 ensuring that only those with the appropriate qualifications and who conduct their practice within ethical guidelines may utilise the title of “paramedic” within the discipline of paramedicine.

Although paramedicine is an integral element of healthcare systems, there is a lack of universal consensus on its definition5 and many terms are used to identify the discipline in different settings. One reason for the lack of a universal definition may arguably be that paramedicine is practiced heterogeneously across the globe. However, there are many similarities, and failure to combine these under a unifying definition may hinder the progression of the paramedicine field as a whole. The lack of consistent nomenclature is demonstrated by a 2016 National EMS Advisory Council (US) committee report and advisory document which listed 37 unique terms for the field of out-of-hospital healthcare and expressed the importance of utilising common terminology.6 Even peak bodies in countries such as the US, which typically uses terms like Emergency Medical Technician (EMT) or Emergency Medical Service (EMS), have advocated for all prehospital medicine providers to become unified as the discipline and profession of paramedicine.7 Examples of terms commonly in use within the international literature are: emergency ambulance services, community paramedicine services, mobile intensive care paramedic, or critical care paramedic, and emergency medical responder (see Appendix A for further information). Furthermore, the absence of a Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) term related to paramedicine (or paramedic) reflects the lack of terminology definition and consistency. Therefore, paramedicine and prehospital literature search filters have been created which have necessarily contained multiple terms to address this inconsistency.8,9 Given the growth and development of paramedic education, research and scholarship, and standards and scope of practice; unification and standardisation of the profession and adoption of a common lexicon should be considered internationally. Examples of this continued growth with the intent of connecting paramedics and the domain of paramedicine internationally include the following groups: Global Paramedic Leadership Alliance,10 Paramedicine World,11 Global Paramedic Higher Education Council,12 Global Community Paramedic Higher Education Council,13 International Roundtable on Community Paramedicine,14 and International Paramedic Registry.15

This lack of global uniformity and conceptual clarity hinders international collaboration and complicates the comparison of research findings, while reducing the development of a widespread body of knowledge and diminishing the strength of the evidence base. Consequently, there are likely to be adverse effects on educational curricula design and healthcare policies16 and limitations to the mobility and transferability of qualifications between both countries and jurisdictions. Clarity of terminology is also essential for the further maturation of paramedicine research, and to facilitate efficient and collegial clinical practice within the wider healthcare system (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Importance of Defining Professional Terms in Healthcare

| Advantages of Clarity of Terms in Healthcare |

|---|

| Assist the development of a strong evidence base |

| Inform agenda for future research |

| Enable international comparisons and benchmarking |

| Assist with articulation of role to patients, colleagues, other healthcare professionals, the public, other key stakeholders |

| Inform curricula development |

| Inform healthcare policy development |

| Provide clarity on concepts guiding contemporary paramedic practice |

| Protection of professional title |

| International work/Humanitarian aid work (professional titles of responders may assist in the rapid organisation of roles) |

The development of an accepted worldwide definition of paramedicine would not be without its challenges. For example, various countries and jurisdictions around the globe utilise different terms for their workforce, have different educational standards, and mandate different standards of practice and models of care. A further hindrance to widespread clarity is that some countries use the term “paramedical” to describe non-physician, hospital-based healthcare workers such as nurses, pharmacists and technicians.17 Occupations included under the umbrella of this alternate usage of the term “paramedical” will not be included in the development of a global definition of paramedicine.

The importance and challenges of generating healthcare definitions are not unique to practice domains such as paramedicine7 or palliative care18 but also exists in the clinical realm. For example, the definition of a pathophysiological event such as exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.19

Previous attempts to fully encapsulate the meaning of paramedicine have generally been nation-centric and have concentrated on issues such as professionalisation, key characteristics, roles, competency standards, and regulation.22–25 A definition of paramedicine should contain multiple elements to comprehensively describe the unique autonomous discipline and its contemporary role within global healthcare. In addition, it needs to demonstrate relevance across national and international borders. With no previous published work undertaken, this study aims to develop a global definition of paramedicine.

Methods

Delphi methodology was utilized to systematically and transparently develop a definition of paramedicine. The Delphi method is a structured process to develop consensus amongst a group of individuals with expertise on a particular topic (Jones & Hunter, 1995). Historically it has been employed within fields such as the military and finance and is now widely utilized for healthcare research to provide consensus on complex issues where there is uncertainty or lack of agreement (Karmarkar, Dubois, and Graff, 2021; Nasa, Jain, and Juneja, 2021). The technique involves nominated experts participating in a series of structured questionnaires requiring their opinion and feedback, which remains anonymous to the other participants (Nasa et al, 2021). It is an iterative process whereby the feedback from each “round” informs refinement of the information included in the next round, with the degree of consensus being assessed at each point (Toma & Picioreanu, 2016). This two-way feedback process enables the participants to reflect on their initial opinions and allows for modification of views throughout the Delphi (Hsu & Sandford, 2007). Delphi rounds may continue until consensus has been achieved, although between two and four rounds are commonly sufficient.26 The Conducting and Reporting of Delphi Studies (CREDES) framework27 informed the conduct and reporting of this Delphi study, thereby ensuring a methodical and well-defined approach. Delphi studies have been utilized to develop operational definitions within other healthcare fields including obstetrics and gynaecology,20 behavioural medicine,28 neurology,29 palliative care,30 and allied health assistants.31

The First Stage – Attribute Identification

An initial literature search was performed to identify attributes pertaining to paramedicine from existing definitions. Search terms included ambulance, paramedics, military, first aid, emergency medical services, emergency medical technicians. In addition, definitions offered by professional organisations and industry bodies were sought (see Appendix B for further information). Utilising text analysis, common attribute themes were identified and six initial domains were developed; i) about the paramedics, ii) the focus and aim of paramedicine, iii) the clinical work of paramedicine, iv) where and when paramedics work, v) paramedicine and transportation, and lastly vi) the role of paramedicine within the healthcare system. These domains formed the basis for the four-round Delphi study.

Overview of the Four-Round Delphi

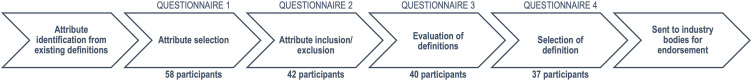

We circulated the identified attributes to global paramedicine leaders and advocates (ie the participants), asking which attributes they believed should be included in a definition of paramedicine (Questionnaire 1). We then asked the participants to consider excluding and including attributes amongst the top-ranked attributes from the previous round (Questionnaire 2). Following the results of the first two questionnaires and their free text input, we generated three definitions that were semantically different and asked for evaluation and ranking in terms of the completeness of the definitions (Questionnaire 3). We then presented the participants with the proposed definition (ie the most accepted definition) asking whether they believed it encapsulated paramedicine adequately (Questionnaire 4). Lastly, we circulated the definition to paramedicine/EMS industry regulatory bodies around the world to seek their input and/or endorsement. See Figure 1 for an overview of this process.

Figure 1.

Delphi process and participation

Questionnaires

In the first questionnaire, after having collected and analysed definitions of “paramedicine” from around the world from governing bodies and industry groups, participants were asked to rate a list of different attributes on a 10-point Likert rating scale, from “no value/definitely should not be included” (least positive response) to “very high value/should be included in the definition of paramedicine” (most positive response). The order in which the attributes appeared was random for each participant.

In the second questionnaire, participants reviewed the most valuable attributes identified in the first questionnaire. They were asked to identify a minimum of five and maximum of seven attributes that should be included in the definition of paramedicine, and from the same list of attributes identifying which attributes that they believed should be excluded from the definition (minimum of 0 and maximum of 5 attributes). Free text responses were welcomed at this stage, as well as after the third and fourth questionnaires.

In the third questionnaire, we created definitions based on the top attributes and based on free text input. Participants rated the definitions on a scale of 0 (“worst possible definition”) to 10 (“best possible definition”). An open-ended question was available for feedback and rationale for ratings.

In the fourth and final questionnaire, we amended the highest-rated definition based on free-text responses and presented that definition to participants asking whether or not they believed it sufficiently encapsulated paramedicine. Following the final questionnaire and group consensus, the proposed definition was sent to multiple paramedic associations and agencies around the world (from Asia, North America, Oceania, Europe) for external validation and endorsement. Based on feedback received from the fourth Delphi round and external paramedic organisations, the definition wording was slightly modified to produce the final version of the definition.

Participants

The participants were identified from the authors’ contact network and represented views from across the globe including the following six regions: South America, North America, Oceania, Asia, Africa and Europe. The participants consisted of a mix of experienced paramedicine clinicians and academics.

Procedures

The questionnaires were distributed and returned using the online survey platform Qualtrics. Participants’ anonymity was maintained throughout the study to ensure freedom and non-judgement of thoughts, beliefs and views. Each questionnaire was sent to participants’ email addresses via blind copy so all email addresses and identities were protected. Responses were collected by the research team and analysed individually and collectively.

Data Analysis

Data were exported from the Qualtrics Survey platform to Microsoft Excel for analysis. Median and interquartile ranges, as well as modes, were calculated for quantitative answers and used for summary statistics. Binary questions were analysed by proportion and percentages. Free-text responses were analysed by the author team. We used inductive content analysis32 – which is suited for half-structured data – to narrow down frequently recurring themes in feedback from the participants. The percentage of agreement between participants which constitutes consensus has not been universally established.33 Moreover, there is a wide variation in the reported percentage of agreement that constitutes consensus (50–97%), and many studies fail to provide a clear target agreement level.34 The criterion for consensus used in our study was 50% agreement.

Ethics

Ethics was approved by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (ID #: 15064).

Results

Questionnaire 1 was sent to 58 with a response rate of 96.6% (56/58). The 33 attributes extracted from currently existing global definitions were ranked on a 10-point Likert scale and six domains were identified (Table 2). The top 17 attributes, which included at least one attribute from each domain, were included in Questionnaire 2.

Table 2.

Existing Paramedicine Definitions: Identified Domains and Attributes

| Domain | Specific Attributes | Median (IQR) | Mode | % Mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| About the paramedics | Paramedicine is a specialized allied health profession | 10 (8.25–10) | 10 | 59% |

| Paramedicine is underpinned by autonomous practice | 8 (7.25–9) | 8 | 22% | |

| Paramedicine requires medical oversight | 4.5 (1–8) | 0 | 9% | |

| A paramedic has complex knowledge and skills | 9 (8–9.75) | 9 | 26% | |

| A paramedic understands pathophysiology and pharmacology | 8 (6–9) | 10 | 24% | |

| The focus and aim of paramedicine | Paramedicine focuses on enhancing survival, controlling morbidity, and preventing disability | 8 (6.25–10) | 10 | 28% |

| Paramedicine focuses on providing advanced emergency medical care | 8 (6–9) | 10 | 22% | |

| Paramedicine focuses on attaining and maintaining optimal health and quality of life | 7 (6–9) | 7 | 13% | |

| Paramedicine focuses on patient-centred care | 9 (8–10) | 10 | 43% | |

| Paramedics treat individuals, families, communities and patients accessing the emergency medical system | 9 (7.25–10) | 10 | 35% | |

| The clinical work of paramedicine | Paramedics deliver emergency, lifesaving care to patients with life-threatening conditions | 9 (8–10) | 10 | 48% |

| Paramedics deliver emergency, critical care, to patients that are seriously ill or injured | 9 (8–10) | 10 | 39% | |

| Paramedics deliver emergency and non-emergency medical care | 10 (8–10) | 10 | 54% | |

| Paramedics deliver general emergency care including assessment, treatment and referrals | 9 (8–10) | 10 | 33% | |

| Paramedics deliver specialized thorough assessments, pathology testing, interpretation, and appropriate medical care | 8 (7–9.75) | 10 | 26% | |

| Paramedics deliver care that contribute to the treatment of chronic conditions and community health monitoring | 8 (6–9) | 10 | 24% | |

| Paramedics work in clinical and non-clinical roles (such as education, leadership and research) | 9 (8–10) | 10 | 41% | |

| Where and when paramedics work | Paramedics respond to unscheduled, episodic events, at any time | 9 (7.25–10) | 10 | 43% |

| Paramedics respond to both scheduled and unscheduled events, at any time | 9 (7–10) | 10 | 41% | |

| Paramedics provide timely provision of appropriate interventions | 9 (8–10) | 10 | 33% | |

| Paramedics work within a variety of environments, predominantly outside hospitals | 9 (8–10) | 9 | 30% | |

| Paramedics work in a pre-hospital context | 8 (4–10) | 10 | 30% | |

| Paramedics work on scene and during transport to hospital | 9 (5.25–10) | 10 | 39% | |

| Paramedics work across a range of settings including emergency, primary and urgent care | 9 (8–10) | 10 | 39% | |

| Paramedicine and transportation | Paramedics provide prompt transport to hospital | 7 (5–9) | 10 | 24% |

| Paramedics transport patients to an appropriate health facility | 8 (7–9.75) | 10 | 26% | |

| Paramedics provide ongoing care if required or arrange alternative options | 9 (7.25–10) | 10 | 33% | |

| Paramedics work in an ambulance transporting patients to the hospital | 5 (1.25–9) | 10 | 24% | |

| The role of paramedicine within the healthcare system | Paramedicine is an essential and intricate part of the healthcare system | 10 (9–10) | 10 | 65% |

| Paramedicine coordinates the responses of multiple emergency agencies | 8 (5–10) | 10 | 28% | |

| Paramedicine is an integrated medical health care delivery system | 8.5 (7–10) | 10 | 37% | |

| Paramedicine is a branch of medicine | 8 (5–10) | 10 | 33% | |

| Paramedicine is fully integrated with the rest of the health care system | 8 (6–10) | 10 | 28% |

Questionnaire 2 received 42 responses (response rate 72.4%). Five out of the 17 attributes identified in the first questionnaire were identified by more than half of the participants as “should be included” in the definition (Table 3).

Table 3.

Attributes Identified from Questionnaire 2 as Important to Include in the Definition of Paramedicine

| Attributes | Include (n) | Include (%) | Exclude (n) | Exclude (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paramedicine is a specialized allied health profession | 31 | 74% | 3 | 7% |

| Paramedicine is an essential and intricate part of the healthcare system | 30 | 71% | 0 | 0% |

| Paramedics work across a range of settings including emergency, primary and urgent care | 26 | 62% | 1 | 2% |

| Paramedics work in clinical and non-clinical roles (such as education, leadership and research) | 25 | 60% | 2 | 5% |

| A paramedic has complex knowledge and skills | 23 | 55% | 4 | 10% |

| Paramedicine focuses on patient-centred care | 19 | 45% | 1 | 2% |

| Paramedics deliver emergency and non-emergency medical care | 17 | 40% | 3 | 7% |

| Paramedics deliver emergency, life-saving care to patients with life-threatening conditions | 15 | 36% | 10 | 24% |

| Paramedics deliver general emergency care including assessment, treatment and referrals | 15 | 36% | 7 | 17% |

| Paramedics treat individuals, families, communities and patients accessing the emergency medical system | 15 | 36% | 3 | 7% |

| Paramedics deliver emergency, critical care, to patients that are seriously ill or injured | 14 | 33% | 7 | 17% |

| Paramedics work within a variety of environments, predominantly outside hospitals | 10 | 24% | 4 | 10% |

| Paramedics respond to both scheduled and unscheduled events, at any time | 9 | 21% | 5 | 12% |

| Paramedics respond to unscheduled, episodic events, at any time | 8 | 19% | 9 | 21% |

| Paramedics provide ongoing care if required or arrange alternative options | 6 | 14% | 4 | 10% |

| Paramedics provide timely provision of appropriate interventions | 4 | 10% | 6 | 14% |

| Paramedics work on scene and during transport to hospital | 2 | 5% | 22 | 52% |

Questionnaire 3 received 40 responses (response rate 69%) where participants ranked the three created definitions from best to worst possible definition (Table 4).

Table 4.

Proposed Definitions of Paramedicine as Rated in Questionnaire 3

| Definition | Median (IQR) | Mode |

|---|---|---|

| Paramedicine is a specialized allied health profession, which works across a range of settings, including emergency, primary and urgent care, as well as non-clinical roles such as education, leadership and research. Paramedics work autonomously and possess complex knowledge and skills, and a broad scope of practice that is an integral part of the healthcare system. | 9 (8–10) | 10 |

| Paramedicine is an essential, specialized and integral part of the healthcare system and spans across emergent, primary and urgent care, working both in the out-of-hospital and in-hospital settings. Paramedics work interdisciplinary in both clinical and non-clinical roles and possess complex knowledge and skills, sufficient to practice autonomously. | 7 (5–8) | 8 |

| Paramedicine is an allied health profession providing community-based emergency healthcare. Paramedics possess a wide range of knowledge, skills and scope of practice to provide optimal health outcomes to their patients. They work in both clinical and non-clinical roles and across a range of primary healthcare settings. | 4.5 (3–7) | 3 |

A total of 37 responses (response rate 63.8%) were received to Questionnaire 4 (final questionnaire). The participants were presented with the proposed definition. Three quarters (n=28/37, 75.7%) reported that they believed it captured paramedicine satisfactorily. Furthermore, the proposed definition was overwhelmingly endorsed by numerous paramedic associations, colleges and agencies from Asia, North America, Oceania, and Europe. Some additional comments and suggestions included clarification around ambulance services versus other agencies such as fire-based services and the conditions and circumstances in which paramedics work.

Based on these four phases, the final definition is described as:

Paramedicine is a domain of practice and health profession that specialises across a range of settings including, but not limited to, emergency and primary care. Paramedics work in a variety of clinical settings such as emergency medical services, ambulance services, hospitals and clinics as well as non-clinical roles, such as education, leadership, public health and research. Paramedics possess complex knowledge and skills, a broad scope of practice and are an essential part of the healthcare system. Depending on location, paramedics may practice under medical direction or independently, often in unscheduled, unpredictable or dynamic settings.

Discussion

Although paramedicine continues to develop and mature both clinically and academically in many parts of the world, there has historically been a lack of consensus concerning professional nomenclature. This lack of conceptual clarity regarding the definition of paramedicine and inherent professional responsibilities may affect national and international comparisons and collaboration, research, curricula development, and clinical practice.16,20,21 To facilitate the future development of paramedicine, it is therefore vital to develop a widely accepted definition of the profession. We have used a Delphi methodology, with the participation of experts from across the globe, to develop a consensus definition of paramedicine.

Throughout the process, there was a considerable level of agreement on many aspects of paramedicine. However, differences in opinions and perspectives across the panel were also demonstrated, both in the ranking of attributes and definitions and in free-text responses. These differences are likely due to the wide range of participants’ education, experience, location, and clinical standards. For example, it is unlikely that perceptions regarding paramedicine will be identical in a large American city compared with a location such as a rural area in Australia. However, it is in these circumstances that a Delphi process may assist with resolving the resulting complexity of views, as it is these agreements and differences of opinion that are vital to informing the development of each successive questionnaire round.

Participant feedback on the relevant and appropriate attributes to include in the definition reflect the high level of specialized clinical care required of a paramedic and the status as an essential component of the wider healthcare environment. The importance of the latter is emphasised by a universal agreement that the attribute of “Paramedicine is an essential and intricate part of the healthcare system” should not be excluded. In addition, the results highlighted the extensive range of capabilities and roles inherent within paramedicine and the diverse environments within which paramedics function. Attributes involving the necessity for medical oversight and the ambulance as a workplace setting were seen to have less importance by the participants, which may be indicative of the continuing development of paramedicine from ambulance stretcher-bearers to autonomous healthcare professionals.1

During the Delphi process, the issues of definitional sensitivity and specificity were considered at length. It was important to balance these two concepts. A definition that was too specific may have excluded important areas within paramedicine whilst excessive sensitivity risked introducing components that are traditionally done by other professions (eg primary community care). Although each of the included attributes is not necessarily unique to paramedicine, it is apparent that the amalgamation of certain attributes is a distinctive feature of paramedicine.

Due to the diverse nature of paramedicine globally, it is unlikely that a definition will ever capture every possible element or variant of paramedic practice or personnel, however, an overarching consensus definition is essential to the continued advancement and maturation of the discipline. Additionally, it is important to note that the proposed definition has been developed within the context of current global healthcare contexts and perceptions. As the discipline of paramedicine continues to advance and mature throughout the world, future revisions to this definition may be required.

Limitations

This study, like all Delphi studies, have limitations. The composition of the expert panel may affect the consensus process and result. Although the Delphi method does not stipulate the characteristics of an “expert”,35 we chose to include a relatively large number of international participants with diverse but extensive experience, both as clinicians and researchers. We believe this will increase prospects for acceptance and application internationally. Although expert opinion is widely considered to produce a lower level of evidence than other research techniques,36 the combined perspectives of a group of experts are considered to have higher validity than the opinion of one expert. This expert consensus is particularly valuable when an experimental design may not be practical.37 Additionally, we did not control for differences in education, qualifications, clinical standards, models of care, location, age or sex. Nonetheless, a key strength of this study is that participants from almost every region in the world were included.

Conclusion

Through the utilisation of a Delphi process, an international consensus definition of paramedicine has been developed. The definition is:

Paramedicine is a domain of practice and health profession that specialises across a range of settings including, but not limited to, emergency and primary care. Paramedics work in a variety of clinical settings such as emergency medical services, ambulance services, hospitals and clinics as well as non-clinical roles, such as education, leadership, public health and research. Paramedics possess complex knowledge and skills, a broad scope of practice and are an essential part of the healthcare system. Depending on location, paramedics may practice under medical direction or independently, often in unscheduled, unpredictable or dynamic settings.

We believe that the adoption of the proposed international consensus definition of paramedicine will provide clarity for providers of out-of-hospital healthcare as well as for other healthcare disciplines, policymakers, the general public, and the media. Importantly, it is a vital step in the unification, collaboration and further development of the discipline of paramedicine.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank and acknowledge all of the experts and paramedic advocates for participating in this study over the four phases.

Abbreviations

CREDES, Conducting and Reporting of Delphi Studies; EMS, emergency medical service; EMT, emergency medical technician; IQR, interquartile range; MeSH, Medical Subject Heading.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Williams B, Onsman A, Brown T. From stretcher-bearer to paramedic: the Australian paramedics’ move towards professionalisation. J Prim Health Care. 2009;7(4):Article 990346. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eaton G, Wong G, Williams V, Roberts N, Mahtani KR. Contribution of paramedics in primary and urgent care: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70(695):e421–e426. doi: 10.3399/bjgp20X709877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olaussen A, Beovich B, Williams B. Top 100 cited paramedicine papers: a bibliometric study. Emerg Med Australas. 2021;33:975–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Townsend RM. What Australian and Irish paramedic registrants can learn from the UK: lessons in developing professionalism. Ir J Paramedicine. 2017;2(2). doi: 10.32378/ijp.v2i2.69 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Long DN, Lea J, Devenish S. The conundrum of defining paramedicine: more than just what paramedics’ do’. Australas J Paramedicine. 2018;15(1). doi: 10.33151/ajp.15.1.629 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National EMS Advisory Council. Changing the nomenclature of emergency medical services is necessary; 2016. Available from: https://www.ems.gov/pdf/Final-Draft-Changing-Nomenclature-of-EMS-120216.pdf. Accessed August 18, 2021.

- 7.National EMS Management Association. Position Statement: call for common nomenclature for the profession of paramedicine; 2017. Available from: https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.nemsma.org/resource/resmgr/position_statements_papers/position-paper-paramedicine-.pdf. Accessed August 18, 2021.

- 8.Olaussen A, Semple W, Oteir A, Todd P, Williams B. Paramedic literature search filters: optimised for clinicians and academics. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2017;17(1):1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12911-017-0544-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burgess S, Smith E, Piper S, Archer F. The development of an updated prehospital search filter for the Cochrane library: prehospital search filter version 2.0. Australas J Paramedicine. 2010;8(4):Article 990444. doi: 10.33151/ajp.8.4.82 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Council of Ambulance Authorities Inc. Global paramedic leadership alliance; 2021. Available from: https://www.caa.net.au/global-paramedic-leadership-alliance-subpage. Accessed October 13, 2021.

- 11.Paramedicine World. Welcome to paramedicine world; 2021. Available from: https://www.paramedicineworld.com/. Accessed October 13, 2021.

- 12.Global Paramedic Higher Education Council. Welcome to GPHEC; 2021. Available from: https://gphec.org/. Accessed October 13, 2021.

- 13.Nursing Network. Global community paramedic higher education council (GCPHEC)™; 2018. Available from: https://cpar.nursingnetwork.com/nursing-news/113451-global-community-paramedic-higher-education-council-gcphec-. Accessed October 13, 2021.

- 14.Community Paramedic. International roundtable on community paramedicine; 2020. Available from: http://ircp.info/Default.aspx. Accessed October 13, 2021.

- 15.International Paramedic Registry. Enhancing the quality of prehospital patient care internationally; 2019. Available from: http://www.iprcert.net/. Accessed October 13, 2021.

- 16.Feo R, Conroy T, Jangland E, et al. Towards a standardised definition for fundamental care: a modified Delphi study. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(11–12):2285–2299. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El-Sherbiny NA, Ibrahim EH, Abdel-Wahed WY. Assessment of patient safety culture among paramedical personnel at general and district hospitals, Fayoum Governorate, Egypt. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2020;95(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dellon E, Goggin J, Chen E, et al. Defining palliative care in cystic fibrosis: a Delphi study. J Cyst Fibros. 2018;17(3):416–421. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2017.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pauwels R, Calverley P, Buist A, et al. COPD exacerbations: the importance of a standard definition. Respir Med. 2004;98(2):99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2003.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schaap T, Bloemenkamp K, Deneux‐Tharaux C, et al. Defining definitions: a Delphi study to develop a core outcome set for conditions of severe maternal morbidity. BJOG. 2019;126(3):394–401. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frisch NC, Rabinowitsch D. What’s in a definition? Holistic nursing, integrative health care, and integrative nursing: report of an integrated literature review. J Holist Nurs. 2019;37(3):260–272. doi: 10.1177/0898010119860685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reed B, Cowin LS, O’Meara P, Wilson IG. Professionalism and professionalisation in the discipline of paramedicine. Australas J Paramedicine. 2019;16:1–10. doi: 10.33151/ajp.16.715 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Meara P. So how can we frame our identity? J Paramed Pract. 2011;3(2):57. doi: 10.12968/jpar.2011.3.2.57 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bowles RR, van Beek C, Anderson GS. Four dimensions of paramedic practice in Canada: defining and describing the profession. Australas J Paramedicine. 2017;14(3). doi: 10.33151/ajp.14.3.539 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paramedics Australasia. Australasian competency standards for paramedics; 2011. Available from: https://nasemso.org/wp-content/uploads/PA_Australasian-Competency-Standards-for-paramedics-2011.pdf. Accessed August 24, 2021.

- 26.Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32(4):1008–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jünger S, Payne SA, Brine J, Radbruch L, Brearley SG. Guidance on Conducting and REporting DElphi Studies (CREDES) in palliative care: recommendations based on a methodological systematic review. Palliat Med. 2017;31(8):684–706. doi: 10.1177/0269216317690685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dekker J, Amitami M, Berman AH, et al. Definition and characteristics of behavioral medicine, and main tasks and goals of the international society of behavioral medicine—an International Delphi Study. Int J Behav Med. 2021;28(3):268–276. doi: 10.1007/s12529-020-09928-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luquin M-R, Kulisevsky J, Martinez-Martin P, Mir P, Tolosa ES. Consensus on the definition of advanced Parkinson’s disease: a neurologists-based Delphi study (CEPA study). Parkinson’s Dis. 2017. doi: 10.1155/2017/4047392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Forbat L, Johnston N, Mitchell I. Defining ‘specialist palliative care’: findings from a Delphi study of clinicians. Aust Health Rev. 2019;44(2):313–321. doi: 10.1071/AH18198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stute M, Hurwood A, Hulcombe J, Kuipers P. Defining the role and scope of practice of allied health assistants within Queensland public health services. Aust Health Rev. 2013;37(5):602–606. doi: 10.1071/AH13042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kyngäs H. Inductive content analysis. In: Kyngäs H, Mikkonen K, Kääriäinen M, editors. The Application of Content Analysis in Nursing Science Research. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020:13–21. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jorm AF. Using the Delphi expert consensus method in mental health research. Aust N. Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49(10):887–897. doi: 10.1177/0004867415600891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM, et al. Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(4):401–409. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Swedo S, Baguley DM, Denys D, et al. A consensus definition of misophonia: using a delphi process to reach expert agreement. medRxiv. 2021. Available from: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.04.05.21254951v2. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burns PB, Rohrich RJ, Chung KC. The levels of evidence and their role in evidence-based medicine. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128(1):305–310. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318219c171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Niederberger M, Spranger J. Delphi technique in health sciences: a map. Public Health Front. 2020;8(Article):457. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]