Abstract

Although yeast RNA polymerase III (Pol III) and the auxiliary factors TFIIIC and TFIIIB are well characterized, the mechanisms of class III gene regulation are poorly understood. Previous studies identified MAF1, a gene that affects tRNA suppressor efficiency and interacts genetically with Pol III. We show here that tRNA levels are elevated in maf1 mutant cells. In keeping with the higher levels of tRNA observed in vivo, the in vitro rate of Pol III RNA synthesis is significantly increased in maf1 cell extracts. Mutations in the RPC160 gene encoding the largest subunit of Pol III which reduce tRNA levels were identified as suppressors of the maf1 growth defect. Interestingly, Maf1p is located in the nucleus and coimmunopurifies with epitope-tagged RNA Pol III. These results indicate that Maf1p acts as a negative effector of Pol III synthesis. This potential regulator of Pol III transcription is likely conserved since orthologs of Maf1p are present in other eukaryotes, including humans.

The yeast RNA polymerase III (Pol III) transcription system is well characterized. Small untranslated RNAs with essential housekeeping functions, such as tRNAs, 5S rRNA, or the U6 small nuclear RNA (snRNA) that is required for mRNA splicing, are synthesized by Pol III with the help of two general auxiliary factors, TFIIIC and TFIIIB. The large TFIIIC factor (six subunits) binds to the DNA promoter elements and assembles the initiation factor TFIIIB (three components) upstream of the start site. Once TFIIIB is in position, it recruits the Pol III enzyme (17 subunits) and directs accurate and multiple rounds of transcription. All of the polypeptide components of the Pol III apparatus (∼1,500 kDa) have been characterized and found to be essential for cell viability (8, 23). The identification of the components of the Pol III system has facilitated the description of a cascade of protein-protein interactions that leads to the recruitment of the Pol III enzyme (reviewed in reference 55).

Detailed knowledge of the yeast Pol III transcription system contrasts with the limited information available on the control of class III gene expression in yeast. Cellular tRNA levels respond to cell growth rate (48, 49), to a nutritional upshift (27, 48) or to nitrogen starvation (36) but only modestly to amino acid starvation (41). Finally, Pol III transcription is repressed in secretion-defective cells (30). Although the mechanism of repression is not clear, it does involve activation of the cell integrity pathway (30). The effect of growth conditions on Pol III transcription is well mimicked in vitro with whole-cell extracts (11, 39). tRNA synthesis is downregulated in dense cell cultures approaching stationary phase, a result due essentially to reduced TFIIIB activity. The TFIIIB component Brf/TFIIIB70 was found to be the limiting factor in extracts from such cells (39). However, the occupancy of the TFIIIB binding site on the SUP53 gene encoding tRNALeu does not decrease in stationary-phase cells. Rather, in vivo footprinting data suggest reduced promoter occupancy by Pol III (25).

In higher eukaryotic cells, Pol III transcription responds to growth rate, developmental phase, cell cycle position, and a number of pathological conditions (reviewed in reference 55). The regulation operates principally at the level of TFIIIB and TFIIIC (17, 20, 42, 46, 52). The tumor suppressors Rb and p53 inhibit TFIIIB (9, 10, 28, 53). Therefore, it is likely that the control of Pol III transcription rate is important in restraining tumor cell proliferation (54). No equivalent negative regulator of Pol III transcription has been found in yeast.

Genes controlling tRNA synthesis in yeast can be identified by nonsense suppression approaches (22). One candidate for such a gene is Saccharomyces cerevisiae MAF1. It was originally identified by the isolation of maf1-1 as a temperature-sensitive mutation that decreases the efficiency of SUP11 (tRNA Tyr/UAA) suppression (34). A search for multicopy suppressors of maf1-1 revealed an intriguing genetic interaction between MAF1 and RPC160, the gene encoding the largest subunit of the RNA Pol III, C160. RPC160 genes with 3′ deletions in their open reading frame suppress the maf1-1 phenotypes when overexpressed (6).

In the present work, we show that tRNA levels are elevated in maf1-1 cells and that spontaneous mutations in RPC160 which reduce tRNA levels also suppress the growth phenotype associated with maf1-1. maf1-1 cell extracts support increased levels of Pol III transcription in vitro compared to wild-type cells. Further, we show that Maf1p is a nuclear protein that physically interacts with RNA Pol III. Therefore, Maf1p appears to be a negative effector of Pol III activity, potentially regulating the level of cellular tRNA in response to external signals. A database search revealed that a variety of organisms have sequences similar to Maf1p, suggesting that this type of Pol III regulation may not be limited to yeast.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media.

The following media were used for growth of yeast: YPD (2% glucose, 2% peptone, 1% yeast extract), YPGly (2% glycerol, 2% peptone, 1% yeast extract), and W0 (2% glucose, 0.67% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids). W0−ura, W0−trp, and W0−leu contained 20 μg of the amino acids per ml required for growth except for the single amino acid as indicated. 5-Fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) medium was prepared as described previously (4). Sporulation medium (SP1) contains 0.25% yeast extract, 0.1% glucose, and 0.98% potassium acetate. Solid media contained 2% agar. All reagents used for media were Difco products.

Strains and plasmids.

The strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. MT6-7, the maf1-1 mutant, was derived by ethyl methanesulfonate mutagenesis of T8-1D (34). The MAF1 gene was disrupted by replacing the internal NheI-HpaI fragment with the URA3 cassette, as described previously (6). KC3-4D, designated as Δmaf1, was derived by sporulation of 4A × 11D diploid heterozygous disruption-deletion of the MAF1 gene. R16 and K2 were selected as spontaneous revertants of maf1-1 in MB123-2C and Δmaf1 in KC3-4D, respectively. In MW671-HA the chromosomal copy of RPC160 is deleted, and C160 is provided by pC160-240 (TRP1 CEN4 HA-RPC160) plasmid carrying the RPC160 gene hemagglutinin HA-tagged at the 5′ end (14). DNA coding for 13 repeats of the myc epitope was inserted just before the stop codon in the endogenous MAF1 in MW671-HA by a PCR-based gene deletion and modification system (31).

TABLE 1.

Genotypes and sources of S. cerevisiae strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| W303-1A | MATa ade2-1 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 trp1-1 can1-100 | R. J. Rothstein |

| 11D | MATα his3 leu2 ura3 | D. Thomas |

| MB105-6A | MATaSUP11 mod5-1 ade2-1 ura3-1 lys2-1 leul trp5-2 | 5 |

| T8-1D | MATα SUP11 mod5-1 ade2-1 ura3-1 lys2-1 leu2-3,112 his4-519 | 56 |

| MT6-7 | MATα SUP11 maf1-1 mod5-1 ade2-1 ura3-1 lys2-1 leu2-3,112 his4-519 | 34 |

| MB123-2C | MATα SUP11 maf1-1 mod5-1 ade2-1 ura3-1 lys2-1 leu1 trp5-2 | Segregant of MT6-7 × MB105-6A |

| KC3-4D | MATα maf1::URA3 his3 leu2 ura3 | 6 |

| R16 | MATα rpc160-16 SUP11 maf1-1 mod5-1 ade2-1 ura3-1 lys2-1 leul trp5-2 | Revertant of MB123-2C |

| K2 | MATα rpc160-2 maf1::URA3 his3 leu2 ura3 | Revertant of KC3-4D |

| MB156-1B | MATα rpc160-2 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 trp1-1 | Segregant of K2 × 4A |

| MW671-HA | MATaade2-101 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 his3-Δ200 ura3-52 trp1-Δ63 rpc160-Δ1::HIS3 pC160-240 (TRP1 CEN4 HA-RPC160) | 14 |

| MW671-HA,myc | MATaMAF1-myc ade2-101 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 his3-Δ200 ura3-52 trp1-Δ63 rpc160-ΔI::HIS3 pC160-240 (TRP1 CEN4 HA-RPC160) | This study |

| MW671-myc | MATaMAF1-myc ade2-101 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 his3-Δ200 ura3-52 trp1-Δ63 rpc160-ΔI::HIS3 pC160-6 (URA3 CEN4 RPC160) | This study |

| J12-5C | MATaura3 leul ade2-1 can1-100 lys2-1 trp5-2 met4-1 | This study |

| 4A | MATatrp1 leu2 ura3 | D. Thomas |

Primers F2MAF (TGTAATAGATGATAAATCAGATCAAGAAGAATCCCTACAGCGGATCCCCGGGTTAATTAA) and R1MAF (AAATAGAAACTTACAATAGTAGACATAAAGGGACTGTTTTGAATTCGAGCTCGTTTAAAC) containing 20 bases complementary to the template (plasmid pFA6a-13Myc-kanMX6) and 40 bases complementary to MAF1 were used to amplify the DNA coding for 13 myc epitopes fused to sequences encoding a kanamycin resistance marker. The 2,325-bp PCR product, pooled from 10 reactions, was transformed into MW671-HA cells, and transformants were selected for geneticin resistance. Insertion of the myc sequences was confirmed by PCR and Western blot experiments.

The resulting strain, MW671-HA,myc, encodes two tagged proteins, Maf1p-myc and C160-HA. MW671-HA,myc harboring pC160-240 (TRP1 CEN4 HA-RPC160) was also transformed with pC160-6 (URA3 CEN4 RPC160) (14) and grown on nonselective medium overnight to allow plamid loss. MW671-myc was selected because it cannot grow on W0−trp and 5-FOA medium but can grow on W0−ura media because it only contains pC160-6 (URA3 CEN4 RPC160) and produces a tagged Maf1p-myc and nontagged C160.

To construct a gene encoding HA tagged MAF1, a ClaI site was created just upstream of the stop codon of the MAF1 open reading frame employing an oligonucleotide, CTGTATCGATTCTTCTTGATCTG, to allow in-frame ligation of the sequence coding for the HA epitope from pYeFH2 (12). This construct was cut with NotI to insert the 110-bp NotI-NotI fragment from pBF30 that encodes a triple HA epitope (47). The EcoRI fragment, containing MAF1 with its own promoter and four HAs at the 3′ end, was subcloned into YCp111 (16), giving YCpMAF-4HA (URA3 CEN4 MAF1-HA).

Identification of maf1-1 mutation.

Two overlapping fragments of the maf1-1 allele and control wild-type MAF1 were amplified by PCR using specific primers, AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer), and genomic DNA prepared from strains MT6-7 and T8-1D. The primer sequences were CGAGGATCCGATGAAATTTATTGATGAGCTAGAT, TGCTGTACCAGAACTG, GAGGATAAGAAGAAGGAG, and CGCGGATCCTACTGTAGGGATTCTTC. The PCR products were sequenced with the same primers in an automatic sequencer ABI PRISM (Perkin-Elmer).

Immunofluorescence.

Immunofluorescence microscopy of Maf1p-HA protein was performed as described previously (37). Mouse 16B12 anti-HA (BabCo) was used in a 1:750 dilution as the primary antibody, and goat anti-mouse Cy3 (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove, Pa.) at 1:250 dilution was used as the secondary antibody. Cells were stained with DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole) at a final concentration of 4 μg/ml for 2 min. Samples were viewed at ×600 magnification on a Nikon Microphot-S.A. microscope equipped with filters for epifluorescence. Images were captured and saved electronically.

Preparation of total RNA and Northern analysis.

Cells were grown in liquid YPD or YPGly at 30°C to log phase (A600 = ca 0.8) and then shifted to a restrictive temperature for 2.5 h. Total RNA was isolated from cells disrupted with glass beads by phenol extraction using LETS buffer (0.1 M LiCl; 0.01 M Na2EDTA; 0.01 M Tris-Cl, pH 7.4; 0.2% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]) (26). A total of 10 μg of each RNA sample was resolved by electrophoresis in 7 M urea, 6% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), or 1.2% Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) agarose gels. The RNAs were transferred from agarose gel to a Zeta-probe membrane (Bio-Rad) with 10× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) by capillary action. For quantitative studies, slot blots were prepared. The membrane was prehybridized in 4× SSC–20 mM EDTA–0.5% SDS–0.1 mg of denatured salmon sperm DNA per ml, and the RNA was hybridized at 37°C in the same solution with oligonucleotide probes labeled with [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase. The probes were as follows: 5′-GCCATCTCCTAGAATCGAACCAGG-3′, complementary to tRNAHis; 5′-GGTAAATTACAGTCTTGCG-3′, complementary to tRNATyr; 5′-CAGTTGATCGGACGGGAACA-3′, complementary to 5S rRNA; and 5′-GGATTGCGGACCAAGCTAA-3′, complementary to U3 snRNA. After hybridization, blots were washed 15 min in 6× SSC at room temperature, exposed to film, or exposed to a phosphorimager plate. RNA was quantified using the laser densitometer GelScan XL (Pharmacia). Arithmetic means and standard deviations of tRNA levels, corrected for snRNA U3 levels, obtained for at least three independent blots are presented.

In vivo labeling of RNA.

Cells were grown in low-phosphate YPD at 30°C to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.8 and then pulse-labeled using 150 μCi of carrier-free [32P]orthophosphate per ml of culture. After 5 min, unlabeled potassium phosphate was added to a final concentration of 0.8 M. The cell culture was further incubated for 15 min and then centrifuged and frozen prior to the preparation of total RNA. Labeled RNA (5 μg) was separated on a 7 M urea–6% PAGE gel. Gels were stained with ethidium bromide, dried, and exposed to a phosphor storage plate or autoradiographed. Quantitative analysis of RNA bands was done as described above.

In vitro transcription.

Wild-type (T8-1D) and maf1-1 mutant (MT6-7) cell extracts were prepared in parallel essentially as follows. First, 6 to 8 g of cells grown in YPD at 30°C was collected in early stationary phase (A600 = ca. 2.0), washed two times with solubilization buffer (200 mM Tris acetate, pH 8.0; 10 mM magnesium acetate; 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol; 10% glycerol), resuspended at 1 ml/g (wet weight) of cells in buffer A800 (180 mM Tris acetate, pH 8.0; 9 mM magnesium acetate; 800 mM ammonium sulfate; 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol; 10% glycerol, 2.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride; Complete protease inhibitor [Roche]), frozen at −70°C in dry ice and ethanol, and disrupted in an Eaton press. The homogenized paste was resuspended at 0.5 ml/g (wet weight) of cells in buffer A400 (same as buffer A800 but with 400 mM ammonium sulfate), and clarified by centrifugation at 20,000 rpm for 10 min ( Beckman roter JA20). The extract was then diluted with 1 ml of buffer A400/g (wet weight) of cells and centrifuged at 40,000 rpm for 150 min in a Beckman 45Ti ultracentrifuge rotor. The whole supernatant was collected, taking care to avoid the flaky white layer at the top of the tubes, and dialyzed for 3 h against 1 liter of transcription buffer (20 mM Tris acetate, pH 8.0; 8 mM magnesium acetate; 25 mM ammonium sulfate; 0.5 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]; 10% glycerol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride; 175 mM potassium glutamate). Insoluble material was removed by low-speed centrifugation.

Transcription was performed as described by Riggs and Nomura (38) with minor modifications. Transcription mixtures (40 μl) contained transcription buffer with 0.2 mM ATP, CTP, and GTP; 0.01 mM UTP; 10 μCi of [α-32P]UTP (400 Ci/mmol; Amersham); 8 U of RNasin inhibitor (Promega), 40 ng of DNA per template; and protein crude extract. Each transcription experiment was carried out with two DNA templates: a mini-35S rRNA gene (35) and a Pol III gene. The transcription extract (65 μg of protein) was preincubated with the DNA templates for 60 min at 25°C in the transcription mixture in the absence of nucleotides. Transcription was initiated by the addition of the nucleotides, allowed to proceed for 15 min at 25°C, and then stopped by the addition of 60 μl of 30 mM EDTA containing E. coli tRNA (800 μg/ml). Nucleic acids were extracted once with phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) and, after addition of 200 μl of 2.5 M ammonium acetate, the RNA was precipitated with 2.5 volumes of ethanol and analyzed on a 7 M urea–6% PAGE gel. Gels were exposed to a PhosphorImager plate (Molecular Dynamics). RNA was quantified using ImageQuant software v.1.1. The arithmetic means and standard deviations of Pol III transcripts levels, corrected for mini-35S rRNA levels, were derived from five independent cell cultures per strain.

Immunopurification experiments.

Immunoprecipitation reactions were performed with cellular extracts (30 μg/μl of protein in a 50-μl reaction volume) in extraction buffer (HEPES [pH 7.5], 50 mM; EDTA, 0.5 mM; CH3COOK, 500 mM; DTT, 1 mM; glycerol, 10%). The reactions were incubated while being agitated at 1,000 rpm in the presence of Dynal PanMouse immunoglobulin G beads (Dynal A.S.) preloaded with either α-myc or α-HA antibody. Incubation was for 3 h at 4°C. Routinely, 2 μg of antibody was incubated with 20 μl of the beads (4 × 108/ml). Beads were recovered by use of a magnet and washed with extraction buffer. The proteins bound to the beads were separated on SDS–8% PAGE gels and analyzed by immunoblotting. The protein concentration was estimated by use of a Bio-Rad protein assay using bovine serum albumin as a standard.

Immunoblotting.

Proteins separated by SDS–8% PAGE were transferred electrophoretically to nitrocellulose membranes. After incubation with a specific antibody as indicated, immune complexes were visualized with anti-mouse or anti-rabbit monoclonal antibody coupled to horseradish peroxidase (Amersham Life Sciences). The monoclonal antibodies 9E10 against myc and 12CA5 against HA were applied.

Sequence homology searches.

S. cerevisiae Maf1p (GI:642810) was searched against several databases using the BLAST (1) server at The National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Similar proteins were exhaustively searched against the same databases until all similar proteins were identified. The identified protein sequences were aligned using CLUSTAL X (45) based on the BLOSUM 62 scoring matrix (19). Complete MAF1-like genes were identified in Caenorhabditis elegans (GI:3786409), Candida albicans (Con 5 2883), and Arabidopsis thaliana (GI:7529279). Partial genomic sequences resembling MAF1 were identified in the following organisms: Plasmodium falciparum (AL035476), Cryptosporidium parvum (AQ522040, B83774, and G35235), and Schizosaccharomyces pombe (GI:2388951, GI:2388963, and GI:1507665). Translations of expressed sequence tags (ESTs) from the following organisms appear to be Maf1p homologs: human, AL040071, AA352022, AA179500, AA486502, AA143586, and others; mouse, AA671675, AA066820, AA467315, AA154074, AA042010, and others; rat, AA899627, H34701, H32342, AI172177, and AA817806; zebrafish, AI794541; Drosophila melanogaster, AA142300, AA140704, AI403188, AA539678, and AI109742; Bombyx mori, AU006267; Brugia malayi, AA841076 and AA471615; Arabidopsis thaliana, AL096524, R83973, AI992545, and AA042353; rice, C26657, D24548, C26708, AU030720, and AQ050286; and Saccharum spp., AA525694.

RESULTS

Maf1p is a nuclear protein conserved from yeast to humans.

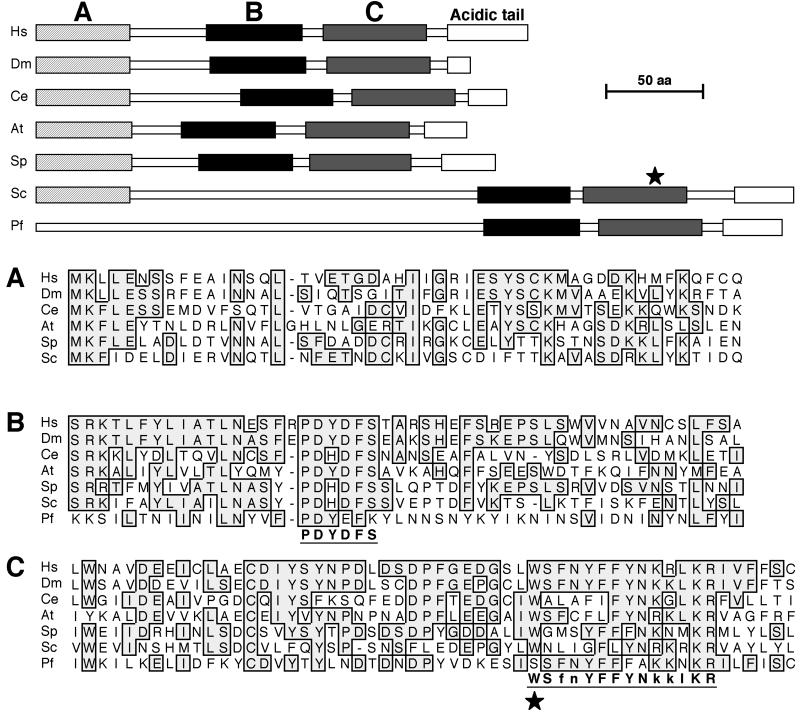

Yeast MAF1 gene (6) encodes a hydrophilic protein of 395 amino acids rich in serine and asparagine residues with a predicted molecular mass of 44.7 kDa. Comparison of the Maf1p sequence with multiple databases using the BLAST server at the NCBI revealed potential orthologs in human, animals, plants, and lower eukaryotes (Fig. 1). No potential prokaryotic orthologs were identified. The eukaryotic proteins identified share three regions of high similarity that are shown in Fig. 1 (labeled regions A, B, and C). Within these regions signature sequences for this protein family can be identified (PDYDFS and WSfnYFFYNkklKR). These motifs have not been previously reported in the PROSITE database (21). Interestingly, in the majority of Maf1p homologs, the second motif includes a putative nuclear targeting signal. The PSORT program found two possible nuclear targeting signals in S. cerevisiae Maf1p: KRRK (position 204) and a double signal RKRK-KRKR (positions 327 and 328).

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of Maf1p and potential orthologs. Abbreviations: Homo sapiens, Hs; Drosophila melanogaster, Dm; Caenorhabditis elegans, Ce; Arabidopsis thaliana, At; Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Sp; Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Sc; Plasmodium falciparum, Pf. Conserved domains are boxed and labeled by letters A (dashed box), B (black box), and C (gray box) in the upper panel. Sequence alignments of each conserved domain (A, B, and C) are shown in the lower panel. Amino acids conserved in at least two sequences are boxed. A star indicates the maf1-1 mutation substituting a stop codon for W319. The two Maf1p-specific signature sequences are underlined.

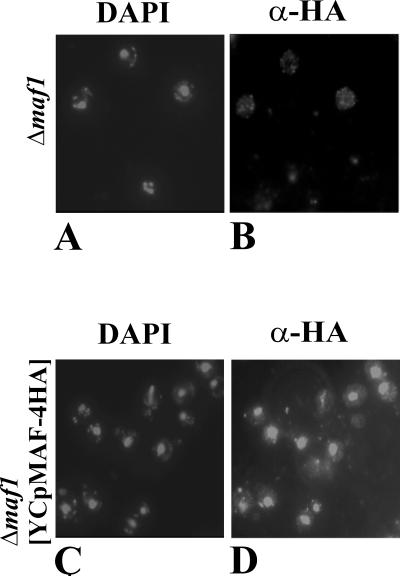

To investigate whether Maf1p represents a new family of eukaryotic nuclear proteins, four in-frame sequences encoding the HA epitope were introduced at the 3′ terminus of MAF1. The epitope-tagged version of the gene subcloned into the centromeric plasmid generating YCpMAF-4HA complemented the growth phenotypes of maf1-1 (MT6-7) and Δmaf1 disruption (KC3-4D). In strains containing YCpMAF-4HA, the anti-HA antibody revealed a protein of about 49 kDa that corresponded to the size expected for HA-tagged Maf1p (not shown). When Δmaf1 cells transformed with YCpMAF-4HA were inspected by indirect immunofluorescence microscopy, a specific signal derived from epitope-tagged Maf1p was detected in the nucleus (Fig. 2), while the cytoplasmic background was the same as in the negative control. Therefore, we concluded that Maf1p is a nuclear protein.

FIG. 2.

Nuclear localization of Maf1p. Δmaf1 (KC3-4D) cells were transformed with the control YCp111 plasmid (A and B) or YCpMAF-4HA, a single-copy plasmid encoding HA-tagged Maf1p (C and D). The cells were stained with DAPI (A and C) or tagged with the 16B12 antibody that recognizes the HA epitope in Maf1p-HA (B and D).

The nature and precise location of the maf1-1 mutation was determined by DNA sequencing. The mutant gene has a single nucleotide change from G to A at position 957, resulting in the change of codon 319 encoding tryptophan into a UGA stop codon. The maf1-1 mutation is localized to the 3′ end of the gene, maps into the signature sequence located in conserved region C, and eliminates the putative nuclear targeting signal RKRK-KRKR at positions 327 and 328 (Fig. 1). We assume that Maf1p function is inactivated in maf1-1 since the temperature-sensitive respiratory growth and antisuppressor phenotype are the same as those observed in strains containing disrupted alleles of MAF1 (6).

Mutations in RPC160 suppress the maf1 defects.

To gain a better understanding of Maf1p function, we searched for second-site suppressors of maf1-1 and spontaneous bypass suppressors of a Δmaf1 disruption. maf1 mutants are temperature sensitive on nonfermentable carbon sources (6). We selected for suppressor mutations that allowed colonies to grow at the restrictive temperature of 37°C on glycerol-containing medium (YPGly). Three spontaneous revertants of maf1-1, i.e., R2, R9, and R16, were isolated. R2 and R9 were obtained from MT6-7, while R16 was obtained from MB123-2C (Fig. 3A). All partially complemented the antisuppressor phenotype of maf1-1 (not shown). In a parallel screen, one revertant, K2, was isolated in Δmaf1 KC3-4D, the MAF1 deletion strain (Table 1). All four suppressors were haploid maf1 mutants with additional chromosomal suppressor mutations that gave a cold-sensitive phenotype. The phenotype of R16 was the most severe since cell growth was reduced at the permissive temperature. Mating of yeast containing the suppressors to each other yielded cold-sensitive diploids, indicating that all mutant alleles were members of a single complementation group.

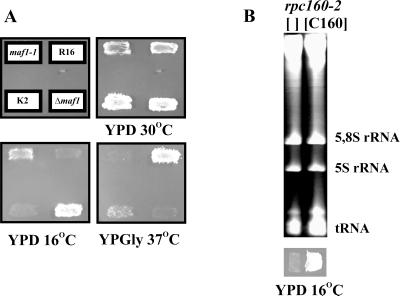

FIG. 3.

Mutations in the RPC160 gene are second site suppressors of maf1 mutants. (A) The R16 suppressor (rpc160-16 maf1-1) and its isogenic maf1-1 strain (MB123-2C), The K2 suppressor (rpc160-2 Δmaf), and the isogenic Δmaf strain (KC3-4D) were grown on YPD and replicated on YPD and YPGly prior to incubation at the indicated temperatures. (B) In vivo content of small RNA species in the rpc160-2 mutant carrying the wild-type MAF1 (strain MB156-1B; Table 1) transformed with empty vector ([ ]) or pC160-6 plasmid ([C160]) that complements its cold-sensitive phenotype. Cells were grown in glucose selective medium and shifted to a nonpermissive temperature (2.5 h at 16°C). RNA was extracted and separated by electrophoresis on a 7 M urea–6% PAGE gel using equal amounts of RNA per lane (10 μg). The gel was stained with ethidium bromide.

Analysis of progeny from crosses of R2, R9, R16, and K2 with wild-type strains showed that the suppressor mutations were recessive and unlinked to maf1. The temperature-sensitive phenotype segregated 2:2 in all tetrads when backcrosses of each single suppressor to the parental maf1-1 or Δmaf1 strains were performed. This indicates that a single nuclear locus was responsible for the suppression effect. The cold-sensitive phenotype in these strains segregated 2:2 in tetrads and was linked to ade2-1. This linkage was further analyzed in a cross of strain K2 with J12-5C (Table 1). Among 20 tetrads analyzed, 18 were PD (parental ditype), indicating a 5-centimorgan (cM) genetic linkage of ade2-1 and the cold-sensitive mutation (40). Given our previous results identifying truncated forms of RPC160 as a high-copy-number suppressor of maf1-1, we hypothesized that the cold-sensitive suppressor mutations recovered here map in RPC160, which is located about 20 kbp from ADE2 on chromosome XV as indicated from the yeast genome sequencing data. The physical distance between RPC160 and ADE2 correlated well with a genetic linkage of 5 cM (33). Indeed, introduction of a centromeric plasmid carrying RPC160 complemented the cold-sensitive growth of K2 and R16. These mapping and rescue data indicated that the suppressor mutations are located in RPC160.

The K2 suppressor mutant was back-crossed with a parental wild-type strain to separate maf1-1 and rpc160 alleles by meiosis. The cold-sensitive phenotype of MB156-1B rpc160-2 carrying the wild-type MAF1 (Table 1) was fully complemented by pC160-6 centromeric plasmid encoding C160 (Fig. 3B). Total RNA was isolated from rpc160-2 transformed with empty vector or with plasmid-encoded C160. Examination of an ethidium-stained RNA gel reveals that the rpc160-2 mutation leads to reduced levels of tRNA (Fig. 3B).

Increased tRNA levels in maf1 mutants correlate with increased tRNA synthesis rate in vitro.

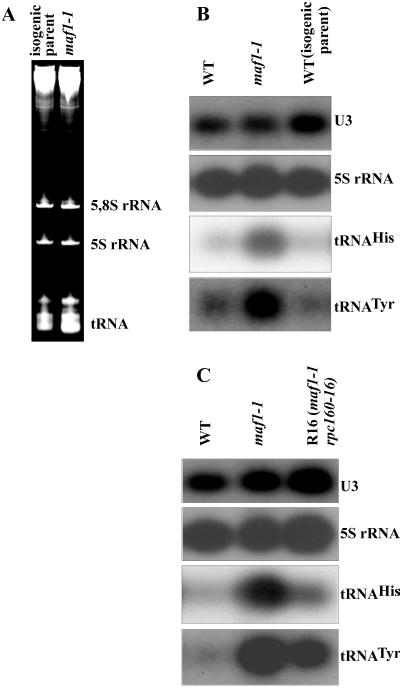

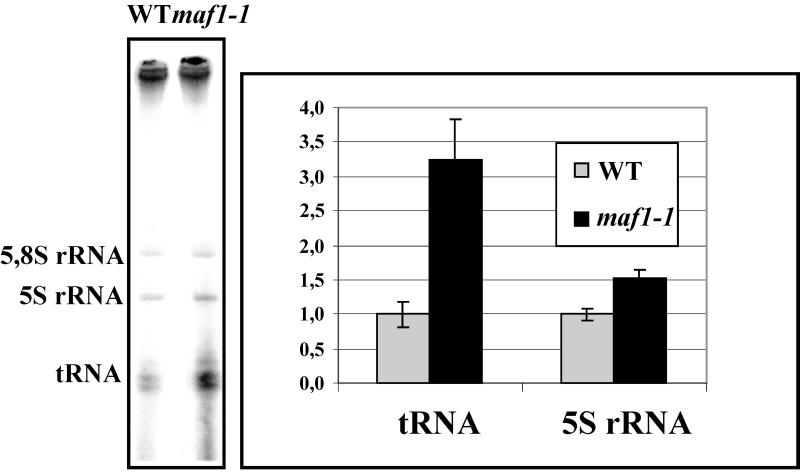

The recovery of RPC160 mutant alleles as suppressors of maf1-1 prompted us to investigate tRNA levels in maf1 mutants. Total RNA was isolated from maf1-1 (MT6-7), Δmaf1 (KC3-4D), and the isogenic parental strains (T8-1D and 11D, respectively) grown with a shift to the restrictive growth conditions. Separation of total cellular RNAs by electrophoresis and examination of ethidium-stained gels revealed a substantial increase of tRNA levels in maf1-1 cells, whereas the levels of 5S and 5.85 rRNA remained stoichiometric and seemed to be unaffected by the maf1-1 mutation (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

tRNA levels are elevated in maf1-1 strains and subsequently reduced in a maf1 rpc160 cold-sensitive suppressor strain. Total RNA was isolated from yeast cells after a shift to a nonpermissive temperature in YPGly (2.5 h at 37°C). (A) Small RNA species from maf1-1 (MT6-7) and the parental strain (T8-1D) were separated on a 7 M urea–6% PAGE gel using equal amounts of RNA per lane (10 μg) and stained with ethidium bromide. (B) Northern analysis of RNA from the wild-type (11D WT), maf1-1 (MT6-7), and parental strain isogenic to maf1-1 (T8-1D) using labeled oligonucleotide probes complementary to U3 RNA, 5S rRNA, tRNAHis, or tRNATyr, as indicated. (C) Northern analysis of RNA from the wild-type (11D WT), maf1-1 (MB123-2C), and maf1-1 strains with a suppressor mutation in C160 (R16) using the probes indicated as in panel B.

Northern blots were performed to confirm this observation. RNA was transferred to a membrane and hybridized with oligonucleotide probes specific to tRNAHis and tRNATyr, 5S rRNA, and U3 snRNA. U3 snRNA, transcribed by Pol II, was used as an internal control to standardize RNA loading. In maf1-1 (Fig. 4B) and Δmaf1 strains (data not shown) the levels of tRNAHis and tRNATyr were markedly elevated compared to wild-type tRNA levels in the isogenic parental strains or in a standard wild-type strain. This tRNA increase was detected independently in two maf1 mutants (maf1-1 and Δmaf1) from different genetic backgrounds. Thus, it is clear that the increase is due to the inactivation of Maf1p. Quantification of the Northern blots revealed that maf1-1 cells have, respectively, (4.0 ± 0.2)- and (3.5 ± 0.1)-fold elevated levels of tRNATyr and tRNAHis over that of the wild-type when corrected for U3 snRNA content. Consistent with the observations made with ethidium-stained RNA, Northern blots showed no significant change of 5S rRNA level in maf1 versus wild-type strain when U3 snRNA is taken as an internal control (Fig. 4B)

In accordance with the growth phenotype, the R16 (Fig. 4C) and K2 (data not shown) cold-sensitive rpc160 suppressors reduce tRNA levels in maf1 mutants. tRNATyr and tRNAHis are reduced (5.0 ± 0.5)- and (8.2 ± 2.1)-fold, respectively, in R16 cells compared to maf1-1 cells without this suppressor (Fig. 4C). The reductions of tRNATyr and tRNAHis by the K2 suppressor mutation are, respectively, (2.1 ± 0.3)- and (2.5 ± 0.5)-fold (data not shown). Therefore, suppression of the Maf1p deficiency by mutations in the C160 subunit of Pol III appears to be correlated with a reduction of tRNA levels.

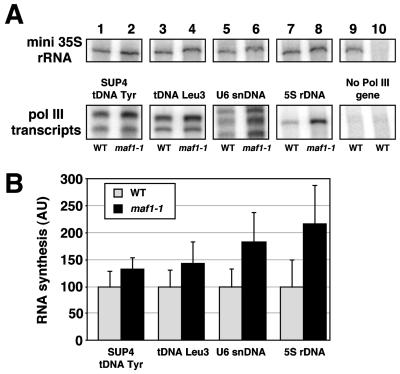

Since tRNA content is increased in maf1 mutant cells, we determined whether the absence of functional Maf1p could increase tRNA synthesis in vitro. We compared the transcription of SUP4 tDNATyr and tDNALeu3 in cellular extracts prepared from maf1-1 and wild-type cells. We used crude extracts so as to avoid removing Maf1p or putative components important for Maf1p function in the wild-type samples. Radiolabeled transcripts were analyzed by urea-PAGE, and the rate of tRNAs transcription was monitored by quantitating the bands as described in Materials and Methods. The relative transcription rates in wild-type and maf1-1 extracts were estimated by reference to the transcription of a mini-35S rRNA gene (a Pol I transcript) used as an internal control. As shown in Fig. 5A, there was a reproducible increase in the transcription rate of the two tRNA genes in maf1-1 crude extracts (lanes 1 to 4). Means of different transcription assays using five independent crude extracts per strain and corrected for mini-35S rRNA levels established firmly the enhanced transcription rate of tRNA genes in crude extracts from maf1-1 cells (Fig. 5B). Remarkably, the U6 snRNA and 5S rRNA were also reproducibly and significantly more actively transcribed in maf1-1 extracts (Fig. 5A, lanes 5 to 8, and Fig. 5B), suggesting that all class III genes could be affected by maf1-1 to different extents.

FIG. 5.

Increased transcription of different Pol III genes in maf1-1 deficient cell extracts. Transcription assays were performed as described in Materials and Methods using a mixture of two genes: a gene transcribed by Pol III and a mini-35S rRNA gene transcribed by Pol I. Transcription was carried out using cell extract (65 μg) from maf1-1 (MT6-7) or parental (T8-1D) strains. RNA was analyzed by urea-PAGE and quantified with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). RNA levels transcribed by Pol III were normalized to the level of mini-35S rRNA transcript. (A) Specific transcription of various genes transcribed by Pol III in crude extracts from wild-type (odd lanes) or maf1-1 cells (even lanes). The different DNA templates are indicated. Lane 9, control experiment with no Pol III gene; lane 10, negative control experiment with no added template DNA. (B) Arithmetic means and standard deviations of Pol III transcript levels, corrected for mini-35S rRNA levels, using five independent crude extracts per strain. The different DNA templates are indicated. All of the RNA bands shown in panel A were used for quantification. Gray bars, wild-type crude extract; black bars, maf1-1 crude extracts; AU, arbitrary units.

Transcription of tRNA was also monitored in vivo by pulse-labeling. Late-log-phase cells from maf1-1 and wild-type strains in low-phosphate medium were incubated for 5 min with [32P]orthophosphate at the permissive temperature. After the addition of excess unlabeled phosphate and further incubation for 15 min to allow for the maturation of 5.8S rRNA, the total RNA was isolated and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Labeling of tRNA band in maf1-1 cells was found to be increased (3 ± 0.8)-fold. A small increase in 5S rRNA synthesis rate was also observed (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

In vivo 32P labeling of RNA. The wild-type (T8-1D) and mutant (MT6-7) cells grown in low-phosphate medium were pulse-labeled for 5 min and supplemented with an excess of nonradioactive phosphate for 15 min to allow for the maturation of 5.8S rRNA. RNAs were extracted and analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. Loading of equal amounts of RNA in each lane was confirmed by staining with ethidium bromide prior to drying of the gel and autoradiography. Synthesis rate of tRNA and 5S rRNA is expressed relative to the 5.8S rRNA species.

Maf1p interacts with RNA Pol III.

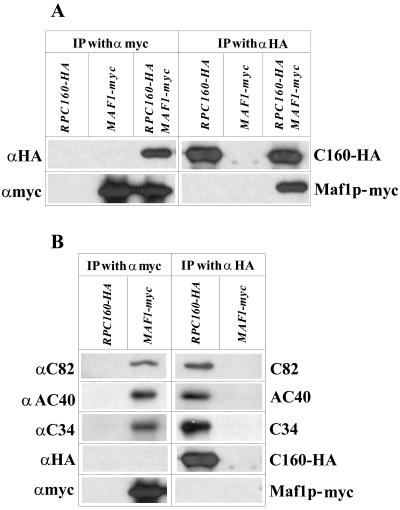

These genetic studies showed that the effect of Maf1p deficiency causing elevated tRNA levels is suppressed by alterations of C160. This genetic interaction suggested that Maf1p and Pol III might physically interact. Coimmunopurification experiments were therefore performed to investigate the possibility of a complex formation between Maf1p and RNA Pol III.

We constructed a strain expressing both C160 and Maf1p tagged with different epitopes. We used the strain MW671-HA (see Table 1) harboring a lethal Δrpc160 deletion complemented by the HA-tagged RPC160 gene harbored on a centromeric plasmid (14), and the chromosomal MAF1 gene in MW671-HA was tagged with the sequence of 13 myc epitopes at its carboxyl terminus (see Materials and Methods). The resulting strain, MW671-HA, myc, which encodes two tagged proteins, Maf1p-myc and C160-HA, has a wild-type phenotype with respect to MAF1 and RPC160. The control strain, MW671-myc, codes for a tagged Maf1p-myc and the untagged version of C160.

Extracts prepared from MW671-HA,myc, MW671-HA, and MW671-myc were incubated with magnetic beads coated with anti-myc monoclonal antibody. The beads were washed, and the bound proteins were eluted and analyzed by SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting. The anti-myc antibody revealed a single band of about 70 kDa in extracts from MW671-HA,myc (RPC160-HA MAF1-myc) and from MW671-myc (MAF1-myc). This protein band was not observed in the control extract from MW671-HA (RPC160-HA) (Fig. 7A, left panel) and therefore corresponds to Maf1p-myc, although the predicted molecular mass of the tagged protein was somewhat lower (65 kDa). Interestingly, a significant fraction (5 to 10%) of HA-tagged C160 was found to copurify with Maf1p-myc when the MW671-HA,myc (RPC160-HA MAF1-myc) extract was incubated with anti-myc beads. The control immunopurified material from MW671-HA (RPC160-HA) cell extracts did not contain Maf1p-myc nor C160-HA (Fig. 7A, left panel). These results suggested the interaction of Maf1p and C160 subunit or at least the interaction of Maf1p and Pol III.

FIG. 7.

Maf1p interacts with RNA Pol III. Crude extracts from cells expressing HA-tagged C160 (RPC160-HA), myc-tagged Maf1p (MAF1-myc) or both (RPC160-HA MAF1-myc) were incubated with magnetic beads coated with anti-myc (left panels) or anti-HA (right panels) antibodies. The beads were washed, and the bound polypeptides were eluted and analyzed by SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting using specific antibodies, as indicated on the left. For clarity, the polypeptides revealed by the specific antibodies are identified on the right. (A) The beads coated with anti-myc antibodies retained specifically Maf1p-myc; background retention of C160-HA was undetectable. However, C160-HA copurified with Maf1p-myc (left panel). Reciprocally, Maf1p-myc was specifically retained on the anti-HA beads only in the presence of C160-HA (right panel). (B) Pol III subunits C82, AC40, and C34 specifically copurified with Maf1p-myc (left panel), as well as with C160-HA (right panel).

To reinforce this conclusion, a reciprocal experiment was performed using anti-HA specific antibody for immunopurification of Pol III, followed by analysis for the presence of Maf1p-myc. Probing with anti-HA antibody indicated that C160-HA was retained on the magnetic beads from MW671-HA,myc (RPC160-HA MAF1-myc) and MW671-HA (RPC160-HA) but not from MW671-myc (MAF1-myc) extracts. Using the anti-myc antibody, the presence of Maf1p-myc was detected in the immunocomplex purified from MW671-HA,myc (RPC160-HA MAF1-myc) extract (Fig. 7A, right panel), providing evidence that Maf1p binds to Pol III in vivo. According to our estimation, about 15% of the Maf1p present in the extract copurifies with the RNA polymerase. As a control for the specificity of this interaction, a protein extract from MW671-myc (MAF1-myc) was used in the same protocol with the anti-HA antibody under the same conditions as described above. As expected, neither C160-HA nor Maf1p-myc was detected.

The anti-myc immune complex from the MW671-myc (MAF1-myc) extract was examined further to determine if the whole Pol III complex, and not simply C160, was bound to Maf1p. Indeed, three other subunits of RNA Pol III—C82, C34, and AC40—were found to copurify with Maf1p (Fig. 7B, left panel). These polypeptides were not detected in the control extract from MW671-HA (RPC160-HA) cells subjected to the anti-myc immunoprecipitation.

Note that the relative intensity of the immune complex in the Western blots was similar when Pol III was directly immunopurified by anti-HA antibody (Fig. 7B, right panel) or copurified with the myc-tagged Maf1p (Fig. 7B, left). These results confirmed the associations of Maf1p and Pol III. As determined by Western blot analysis, neither TBP nor τ55, τ95, and τ131 subunits of TFIIIC copurified detectably with Maf1p. A slight increase of Brf1/TFIIIB70 signal above background suggested the possibility of a Maf1p-TFIIIB70 interaction (results not shown).

DISCUSSION

Regulation of Pol III-directed tRNA biosynthesis is a potentially important mechanism that may contribute to the cell metabolic economy and coordination of translation with growth. The genetic and biochemical data presented here support the model that in S. cerevisiae Maf1p is a negative effector of Pol III: (i) mutations in the MAF1 gene increased the level of tRNAs in vivo and the rate of Pol III RNA synthesis in vitro; (ii) Maf1p, a nuclear protein, coimmunopurified with the components of the Pol III complex; and (iii) mutations in the largest Pol III subunit, C160, suppressed mutations in MAF1 and restored normal levels of tRNA. The presence of proteins similar to yeast Maf1p in a wide variety of organisms suggests that Maf1p homologs may provide a mechanism for the coordination of Pol III transcription with cell growth rate in eukaryotes.

Pleiotropic phenotype of maf1 mutants.

maf1-1 was originally isolated as a mutation that decreases the efficiency of the tRNA suppressor SUP11. Although one might have anticipated that increased cellular tRNA levels would improve the efficiency of tRNA-mediated nonsense suppression, our data show the opposite. There are a number of mechanisms that could account for this counterintuitive result. First, since SUP11 tRNA is a minor tRNA Tyr/UAA, even if SUP11 tRNA is proportionally elevated in the maf1 tRNA population, it may compete less efficiently for tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase, EF1α, or ribosome binding, resulting in the observed antisuppressor phenotype. This explanation is supported by the observation that increasing the copy number of a SUP11 tRNA encoding gene overcomes the antisuppression of maf1-1 cells (K. Pluta and M. Boguta, unpublished results). Alternatively, reduced suppression could result from altered SUP11 tRNA modification. We recently reported that cells have limiting quantities of dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (3), the precursor for the i6A modification found at position 37 of tRNATyr. Since suppression is dependent upon this modification and tRNAs are overproduced, it is possible that not all i6A-containing tRNAs are completely modified in maf1 cells. Our preliminary results indicate that tRNAs in maf1-1 strains contain i6A (M. Boguta and N. C. Martin, unpublished results); nevertheless, partial modification would result in reduced nonsense suppression.

In addition to having high tRNA levels, maf1 mutants are also temperature sensitive when grown on nonfermentable carbon sources, suggesting a connection between Maf1p and mitochondrial biogenesis or function. Since Maf1p is a nuclear protein, its location is inconsistent with a mitochondrial function. Nonetheless, this is not the first example of a mutation that alters tRNA biogenesis and the ability of yeast cells to grow on respiratory substrates. A partial deletion of the N-terminal domain of τ55, a TFIIIC subunit required for tRNA transcription, impairs its function and cell growth at elevated temperatures on nonfermentable carbon sources (32). Maf1p may be involved in coupling carbon metabolism to tRNA transcription because the levels of tRNA in maf1-1 cells are fourfold increased on nonfermentable carbon source and only twofold increased on fermentable carbon source (data not shown).

Effect of Maf1p on Pol III transcription.

Steady-state tRNA levels in maf1 mutants are significantly increased relative to 5S rRNA levels that reflect the cellular content in the 60S ribosomal subunit. Northern analysis confirmed that the level of two different tRNAs, tRNAHis and tRNATyr, increased about fourfold but the 5S rRNA level remained the same relative to U3 RNA that is a Pol II transcript. That result is supported by pulse-labeling experiments showing a threefold increase of tRNA synthesis in maf1-1 relative to 5.8S rRNA (Fig. 6). It is likely that the population of tRNAs was increased as a whole, as also suggested by the trailing of the tRNA species in ethidium bromide-stained stained gels (Fig. 4A).

Remarkably, in vitro mutant extracts showed a small but reproducible increase in tRNA synthesis and a larger effect on 5S rRNA, also a Pol III transcript. The fact that the in vitro synthesis rate but not the steady-state level of 5S rRNA in vivo is affected in the absence of functional Maf1p is intriguing. This result is reminiscent of the in vivo observation that mutations in essential components of the Pol III transcription system, including several Pol III subunits (C34, C31, C82, C55, and C160), caused a strong, preferential decline in tRNA synthesis, while 5S rRNA synthesis and the 5S rRNA/5.8S rRNA ratio remained relatively unaffected (18, 43). This observation is only partly understood (13). Since cell extracts from maf1-1 cells were found to be more active in transcribing several class III genes, including the 5S rRNA gene, in vitro, we suggest that the 5S rRNA made in excess of ribosome biogenesis needs is rapidly turned over.

Interaction of Maf1p with RNA Pol III.

The increased in vitro Pol III transcription of maf1-1 extracts suggests a direct interaction of Maf1p with the Pol III complex. The observation that mutations in the largest subunit of Pol III, C160, counteract MAF1 inactivation led us to investigate a possible physical interaction between Maf1p and Pol III. Immunopurification experiments demonstrated that Maf1p is directly or indirectly tightly associated with C160 in cell extracts. The precise binding target of Maf1p on Pol III, however, is undefined since C160 is part of a 17-subunit enzyme. That Maf1p is bound to Pol III and not to a hypothetical free pool of C160 polypeptides was confirmed by showing that three additional subunits of Pol III (C34, AC40, and C82) copurify, together with C160, with Maf1p. This finding strongly suggests that Maf1p represses tRNA synthesis by a direct action on the Pol III enzyme.

Maf1p might interfere with Pol III recruitment by the preinitiation TFIIIB-TFIIIC-DNA complex, or it might block a later stage of the transcription cycle or counteract a putative activator that might either be a component of the Pol III transcription machinery or an yet-as-unknown protein interacting with the Pol III enzyme. One could propose a model in which an undefined activator would bind to the N-terminal part of C160 to account for the fact that overexpression of that small part of C160 suppresses the maf1-1 defect, possibly by titrating the activator (6). Limitation of the activator would in consequence decrease the tRNA levels. The rpc160 cold-sensitive mutations could similarly interfere with the interaction or the function of the putative activator. Alternatively, these mutations could decrease the basal enzyme activity, thereby restoring a lower level of tRNA. This explanation is in keeping with the cryosensitive phenotype of the R16 and K2 suppressors but does not account well for the fact that all suppressor mutations isolated affected C160 and not other subunits of Pol III. It is interesting that stationary-phase cells, with repressed tRNA synthesis, have a normal in vivo footprinting pattern on the TFIIIB binding region and a decreased occupancy of the transcription start site (−10 to +15 region) indicative of a Pol III recruitment defect (25). Our attempts to supplement Maf1p-deficient transcription extracts with recombinant Maf1p to restore control (decreased) levels of SUP4 DNA transcription were unsuccessful.

Maf1p, the founding member of a new class of Pol III negative effectors.

There is a remarkable conservation of the yeast and human Pol III machineries. The most conserved components are those involved in transcription complex assembly: subunit of TFIIIC, τ131, all components of TFIIIB (TBP, Brf/TFIIIB70, and B"/TFIIIB90), and the tetrad of Pol III-specific subunits (C82, C34, C31, and C17) all have structural and functional homologs in human cells (2, 15, 24, 44, 50, 51). Since Maf1p is conserved across a wide range of organisms, it is probable that the orthologs of Maf1p are involved in Pol III regulation in higher cells. This would be very interesting in light of the connection between Pol III regulation and the malignancy process (29). The abundance of Pol III transcripts is abnormally elevated in many types of transformed and tumor cells (55). In mammals, two tumor suppressors, Rb (53) and p53 (7, 9), act as global repressors of Pol III transcription. Rb and p53 interact with and inactivate TFIIIB (9, 10, 28). Remarkably, Rb mutations occurring in tumors also release TFIIIB from repression (10). Deregulation of the control of Pol III and Pol I transcription is clearly an important step in tumor development. Therefore, it will be important to determine whether Maf1p orthologs really represent a new class of Pol III regulators in mammals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank B. Szczesniak and M. Steffen for excellent technical assistance. We are also grateful to Joël Acker, Christine Conesa, Gérald Peyroche, and Emmanuel Favry (CEA/Saclay) for helpful discussions and their help with the in vitro experiments.

This work was supported by State Committee for Scientific Research (KBN) grant 6PO4B02915 to K.P. and M.B., State Committee for Scientific Research grant 6P04A03315 to K.P. National Science Foundation grant MCB 9506810 to A.K.H., National Science Foundation grant MCB9528216 to N.C.M., and French-Polish Centre of Biotechnology of Plants grants to K.P. and W.J.S.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schaffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arrebola R, Manaud N, Rozenfeld S, Marsolier M C, Lefebvre O, Carles C, Thuriaux P, Conesa C, Sentenac A. Tau91, an essential subunit of yeast transcription factor IIIC, cooperates with tau138 in DNA binding. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:1–9. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benko A L, Vaduva G, Martin N C, Hopper A K. Competition between a sterol biosynthetic enzyme and tRNA modification in addition to changes in the protein synthesis machinery causes altered nonsense suppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:61–66. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boeke J D, Lacroute F, Fink G R. A positive selection for mutants lacking orotidine 5′ phosphate decarboxylase activity in yeast: 5-fluoro-orotic acid resistance. Mol Gen Genet. 1984;197:345–346. doi: 10.1007/BF00330984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boguta M, Hunter L A, Gillman E C, Martin N C, Hopper A K. Subcellular locations of MOD5 proteins: mapping of the sequences sufficient for targeting to mitochondria and demonstration that mitochondrial and nuclear isoforms commingle in the cytosol. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2298–2306. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.4.2298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boguta M, Czerska K, Zoladek T. Mutation in a new gene MAF1 affects tRNA suppressor efficiency in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene. 1997;185:291–296. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00669-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cairns C A, White R J. p53 is a general repressor of RNA polymerase III transcription. EMBO J. 1998;17:3112–3123. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.11.3112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chedin S, Ferri M L, Peyroche G, Andrau J C, Jourdain S, Lefebvre O, Werner M, Carl C, Sentenac A. The yeast RNA polymerase III transcription machinery: a paradigm for eukaryotic gene activation. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1998;63:381–389. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1998.63.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chesnokov I, Chu W M, Botchan M R, Schmid C W. p53 inhibits RNA polymerase III-directed transcription in a promoter-dependent manner. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:7084–7088. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.12.7084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chu W M, Wang Z, Roeder R G, Schmid C W. RNA polymerase III transcription repressed by Rb through its interactions with TFIII and TFIIIC2. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:14755–14761. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.23.14755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clarke E M, Peterson C L, Brainard A V, Riggs D L. Regulation of the RNA polymerase I and III transcription systems in response to growth conditions. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:22189–22195. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.36.22189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cullin C, Minvielle-Sebastia L. Multipurpose vectors designed for the fast generation of N- or C-terminal epitope-tagged proteins. Yeast. 1994;10:105–112. doi: 10.1002/yea.320100110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dechampesme A M, Koroleva O, Leger-Silvestre I, Gas N, Camier S. Assembly of 5S ribosomal RNA is required at a specific step of the pre-rRNA processing pathway. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:1369–1380. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.7.1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dieci G, Herman-Le-Denmat S, Lukhtanov E L, Thuriaux P, Werner M, Sentenac A. A universally conserved region of the largest subunit participates in the active site of RNA polymerase III. EMBO J. 1995;14:3766–3776. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00046.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferri M L, Peyroche G, Siaut M, Lefebvre O, Carles C, Conesa C, Sentenac A. A novel subunit of yeast RNA polymerase III interacts with the TFIIB-related domain of TFIIIB70. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:488–495. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.2.488-495.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gietz R D, Sugino A. New yeast-Escherichia coli shuttle vectors constructed with in vitro mutagenized yeast genes lacking six-base pair restriction sites. Gene. 1988;74:527–534. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90185-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gottesfeld J M, Wolf V J, Dang T, Forbes D J, Hartl P. Mitotic repression of RNA polymerase III transcription in vitro mediated by phosphorylation of a TFIIIB component. Science. 1994;263:81–84. doi: 10.1126/science.8272869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gudenus R, Mariotte S, Moenne A, Ruet A, Memet S, Buhler J M, Sentenac A, Thuriaux P. Conditional mutants of RPC160, the gene encoding the largest subunit of RNA polymerase C in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1988;119:517–526. doi: 10.1093/genetics/119.3.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henikoff S, Henikoff J G. Amino acid substitution matrices from protein blocks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10915–10919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoeffler W K, Kovelman R, Roeder R G. Activation of transcription factor IIIC by the adenovirus E1A protein. Cell. 1988;53:907–920. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)90409-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hofmann K, Bucher P, Falquet L, Bairoch A. The PROSITE database, its status in 1999. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:215–219. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hopper A K. Genetic methods for study of trans-acting genes involved in processing of precursors to yeast cytoplasmic transfer RNAs. Methods Enzymol. 1990;181:400–420. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)81139-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huet J, Manaud N, Dieci G, Peyroche G, Conesa C, Lefebvre O, Ruet A, Riva M, Sentenac A. RNA polymerase III and class III transcription factors from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Enzymol. 1996;273:249–267. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)73024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsieh Y J, Wang Z, Kovelman R, Roeder R G. Cloning and characterization of two evolutionarily conserved subunits (TFIIIC102 and TFIIIC63) of human TFIIIC and their involvement in functional interactions with TFIIIB and RNA polymerase III. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:4944–4952. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.7.4944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huibregtse J M, Engelke D R. Genomic footprinting of a yeast tRNA gene reveals stable complexes over the 5′-flanking region. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:3244–3252. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.8.3244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaiser C, Michaelis S, Mitchel A. Yeast RNA isolation: methods in yeast genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kief D R, Warner J R. Coordinate control of syntheses of ribosomal ribonucleic acid and ribosomal proteins during nutritional shift-up in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1981;1:1007–1015. doi: 10.1128/mcb.1.11.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larminie C G, Cairns C A, Mital R, Martin K T, Kouzarides K, Jackson S P, White R J. Mechanistic analysis of RNA polymerase III regulation by the retinoblastoma protein. EMBO J. 1997;16:2061–2071. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.8.2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Larminie C G, Alzuherri H M, Cairns C A, McLees A, White R J. Transcription by RNA polymerases I and III: a potential link between cell growth, protein synthesis and the retinoblastoma protein. J Mol Med. 1998;76:94–103. doi: 10.1007/s001090050196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Y, Moir R D, Sethy-Coraci I K, Warner J R, Willis I M. Repression of ribosome and tRNA synthesis in secretion-defective cells is signaled by a novel branch of the cell integrity pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;11:3843–3851. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.11.3843-3851.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Longtine M S, McKenzie III A, Demarini D J, Shah N G, Wach A, Brachat A, Philippsen P, Pringle J R. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998;14:953–961. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<953::AID-YEA293>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manaud N, Arrebola R, Buffin-Meyer B, Lefebvre O, Voss H, Riva M, Conesa C, Sentenac A. A chimeric subunit of yeast transcription factor IIIC forms a subcomplex with tau95. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3191–3200. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mortimer R K, Schild D, Contopoulou C R, Kans J A. Genetic map of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, 10th. Yeast. 1989;5:321–403. doi: 10.1002/yea.320050503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murawski M, Szczesniak B, Zoladek T, Hopper A K, Martin N C, Boguta M. maf1 mutation alters the subcellular localization of the Mod5 protein in yeast. Acta Biochim Pol. 1994;41:441–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Musters W, Knol J, Maas P, Dekker A F, Van Heerikhuizen H. Linker scanning of the yeast RNA polymerase I promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:9661–9678. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.23.9661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oliver S G, McLaughlin C S. The regulation of RNA synthesis in yeast. I: Starvation experiments. Mol Gen Genet. 1977;154:145–153. doi: 10.1007/BF00330830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pringle J R, Adams A E, Drubin D R, Haarer B K. Immunofluorescence methods for yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:565–602. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94043-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riggs D L, Nomura M. Specific transcription of Saccharomyces cerevisiae 35 S rDNA by RNA polymerase I in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:7596–7603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sethy I, Moir R D, Librizzi M, Willis I M. In vitro evidence for growth regulation of tRNA gene transcription in yeast. A role for transcription factor (TF) IIIB70 and TFIIIC. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:28463–28470. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.47.28463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sherman F, Wakem P. Mapping of the yeast genes. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:38–56. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shulman R W, Sripati C E, Warner J R. Noncoordinated transcription in the absence of protein synthesis in yeast. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:1344–1349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sinn E, Wang Z, Kovelman R, Roeder R G. Cloning and characterization of a TFIIIC2 subunit (TFIIIC beta) whose presence correlates with activation of RNA polymerase III-mediated transcription by adenovirus E1A expression and serum factors. Genes Dev. 1995;9:675–685. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.6.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stettler S, Mariotte S, Riva M, Sentenac A, Thuriaux P. An essential and specific subunit of RNA polymerase III (C) is encoded by gene RPC34 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:21390–21395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Teichmann M, Dieci G, Huet J, Ruth J, Sentenac A, Seifart K H. Functional interchangeability of TFIIIB components from yeast and human cells in vitro. EMBO J. 1997;16:4708–4716. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.15.4708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thompson J D, Plewniak T J, Jeanmougin F, Higgins D G. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tower J, Sollner-Webb B. Polymerase III transcription factor B activity is reduced in extracts of growth-restricted cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:1001–1005. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.2.1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tyers M, Tokiwa G, Futcher B. Comparison of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae G1 cyclins: Cln3 may be an upstream activator of Cln1, Cln2 and other cyclins. EMBO J. 1993;12:1955–1968. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05845.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Waldron C. Synthesis of ribosomal and transfer ribonucleic acids in yeast during a nutritional shift-up. J Gen Microbiol. 1977;98:215–221. doi: 10.1099/00221287-98-1-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Waldron C, Lacroute F. Effect of growth rate on the amounts of ribosomal and transfer ribonucleic acids in yeast. J Bacteriol. 1975;122:855–865. doi: 10.1128/jb.122.3.855-865.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang Z, Luo T, Roeder R G. Identification of an autonomously initiating RNA polymerase III holoenzyme containing a novel factor that is selectively inactivated during protein synthesis inhibition. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2371–2382. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.18.2371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang Z, Roeder R G. Three human RNA polymerase III-specific subunits form a subcomplex with a selective function in specific transcription initiation. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1315–1326. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.10.1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.White R J, Stott D, Rigby P W. Regulation of RNA polymerase III transcription in response to F9 embryonal carcinoma stem cell differentiation. Cell. 1989;59:1081–1092. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90764-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.White R J, Trouche D, Martin K, Jackson S P, Kouzarides T. Repression of RNA polymerase III transcription by the retinoblastoma protein. Nature. 1996;382:88–90. doi: 10.1038/382088a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.White R J. Regulation of RNA polymerases I and III by the retinoblastoma protein: a mechanism for growth control? Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:77–80. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(96)10067-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.White R J. RNA polymerase III transcription. New York, N.Y: Springer-Verlag/ R. G. Landes Co.; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zoladek T, Vaduva G, Hunter L A, Boguta M, Go B D, Martin N C, Hopper A K. Mutants altering the mitochondrial-cytoplasmic distribution of Mod5p implicate the actin cytoskeleton and mRNA 3′ ends and/or protein synthesis in mitochondrial delivery. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6884–6894. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.12.6884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]