PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS

Consider a possible association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and GBS. More epidemiologic data are required to support a causal relationship.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) has spread around the world since it emerged in Wuhan, and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has become a pandemic.1 There is still little information regarding possible neurologic complications of this spread. Herein, we describe a patient with Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) preceded by COVID-19, raising the possibility of a causal relationship.

Case

On March 27, 2020, a 58-year-old woman with hypertension presented to our emergency department with a complaint of loss of strength in all 4 extremities. She had been diagnosed 2 months before with infiltrating breast carcinoma (cT2m pN1 cM0, Stage IIB) and received a cycle of neoadjuvant doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and paclitaxel, followed by right mastectomy with axillary lymphadenectomy. A second cycle of doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide was given on March 6. In addition, she had been seen by her primary care physician for complaints of dry cough, odynophagia, and dyspnea on March 2.

On March 19, she began to suffer progressive, symmetric limb weakness accompanied by paresthesia in her hands and feet. Neurologic examination disclosed bilateral facial nerve palsy, symmetric and severe tetraparesis with distal predominance, glove and stocking hypoesthesia, and global areflexia. Lung auscultation revealed bibasilar crackles. Days later, she experienced bradycardia, constipation, and urinary retention.

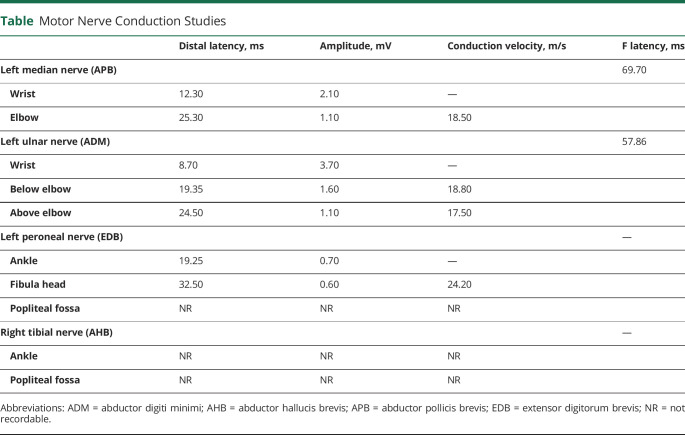

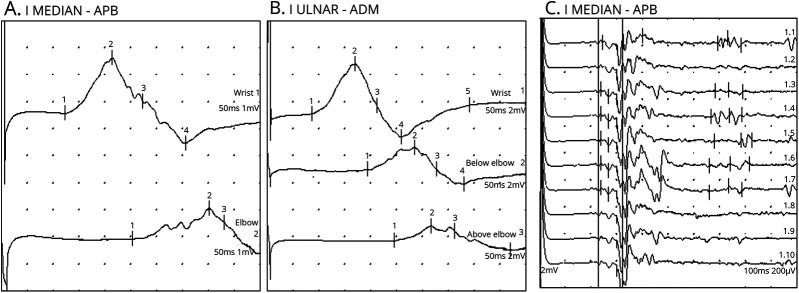

Blood tests on admission showed leukocytosis (17.51 × 109/L, normal: 1.5–7.5 × 109/L), neutrophilia (14.52 × 109/L, normal: 1.5–7.5), thrombocythemia (627.00 × 109/L, normal: 150.0–400.0 × 109/L), and hyperfibrinogenemia (555.00 mg/dL, normal: 150.0–400.0 mg/dL). The remainder results, including lymphocytes, D-dimer, lactate dehydrogenase, and C-reactive protein, were anodyne. Serum antiganglioside antibodies were negative. CSF testing disclosed albuminocytologic dissociation (cell count 1 × 106/L, normal: 0–8 × 106/L; protein levels 114.9 mg/dL, normal: 8–43 mg/dL), an elevated immunoglobulin G index (0.8; normal: 0.0–0.7), negative oligoclonal bands, and negative onconeuronal antibodies. Brain CT showed no abnormalities. Nerve conduction studies and needle electromyography were consistent with acute demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy with associated axonal damage (Table and Figure). The initial chest X-ray was normal, but the second showed a mixed interstitial and alveolar pattern with both lungs affected. Nasopharyngeal swabs were extracted, with a positive result for SARS-CoV-2 on reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction assay.

Table.

Motor Nerve Conduction Studies

Figure. Motor Nerve (Left Median and Left Ulnar) Conduction Studies.

(A) Left median nerve conduction study demonstrating prolonged distal motor latency, decreased motor nerve conduction velocity, conduction block, and temporal dispersion. (B) Left ulnar nerve conduction study demonstrating prolonged distal motor latency, decreased motor nerve conduction velocity, conduction block, and temporal dispersion. (C) Increased F wave latency in the left median nerve. All of these findings are consistent with a demyelinating form of Guillain-Barré syndrome. ADM = abductor digiti minimi; APB = abductor pollicis brevis.

The patient was diagnosed with COVID-19 and GBS. She received IV immunoglobulin (IVIg, 2 g/kg) and hydroxychloroquine. Two weeks after admission, the patient experienced significant muscle strength improvement, and her respiratory symptoms resolved.

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

The authors have obtained written informed consent from the patient participating in the study.

Data Availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Discussion

The novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 is responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. Similar to other betacoronaviruses, evidence has suggested that SARS-CoV-2 may have a neuroinvasive capacity and associated neurologic conditions. Previously, a patient with Middle East Respiratory Syndrome infection had been diagnosed with Bickerstaff encephalitis overlapping with GBS2 and 4 cases of critical illness polyneuropathy/myopathy had been related to SARS-CoV.3 In April 2020, a case of possible GBS associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection was reported, with a nonclassic postinfectious pattern, suggesting a possible causal relationship.4

Our case reports an acute demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy in the seventeenth day of symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. According to updated National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke criteria,5 there is a high level of certainty of a GBS diagnosis (progressive bilateral weakness of arms and legs, areflexia, autonomic dysfunction, progressive phase lasting less than 4 weeks, cranial nerve involvement, and consistent CSF and EMG findings). Moreover, as other coronaviruses have previously resulted in virus-induced neuroinmunopathology or neuropathology,6 the SARS-CoV-2 infection may have triggered GBS.

Given the oncological history, a possible paraneoplastic syndrome was considered as an alternative diagnosis. According to the current diagnostic criteria,7 it could have been a nonclassic syndrome, without antibodies, within 2 years of cancer onset. Nevertheless, the existing literature suggests that these associations are possibly coincidental and specifically with breast cancer and without onconeural antibodies, only occasional. Chemotherapy drugs can also cause acute polyneuropathy, but they are typically axonal, predominantly sensitive, and without cranial nerve involvement nor dysautonomia.

In this case, respiratory and neurologic improvement was achieved after treatment with IVIg and hydroxychloroquine. COVID-19 can be severely worsened if there is an impairment of respiratory musculature. Moreover, bacterial superinfection related to dysphagia should be considered. Regarding treatment, there is already evidence that COVID-19 increases the risk of thrombosis,1 which should be taken into account when administering IVIg. Concomitant to an active infection, plasmapheresis could be hazardous. In the matter of a novel disease, with limited scientific evidence available, clinical decisions must be individualized and previously informed consent from patients must be received.

Acknowledgment

The authors extend their gratitude to this patient and her family for their time and patience. The authors also thank Elisabeth Bassini for English language editing.

Appendix. Authors

Study Funding

No targeted funding reported.

Disclosure

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

References

- 1.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China. N Eng J Med 2020;382:727–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim JE, Heo JH, Kim HO, et al. Neurological complications during treatment of Middle East respiratory syndrome. J Clin Neurol 2017;13:227–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsai L, Hsieh S, Chao C, et al. Neuromuscular disorders in severe acute respiratory syndrome. Arch Neurol 2004;61:1669–1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao H, Shen D, Zhou H, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection: causality or coincidence? Lancet Neurol 2020;19:383–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leonhard S, Mandarakas M, Gondim F, et al. Diagnosis and management of Guillain–Barré syndrome in ten steps. Nat Rev Neurol 2019;15:671–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desforges M, Le Coupance A, Dubeau P, et al. Human coronaviruses and other respiratory viruses: underestimated opportunistic pathogens of the central nervous system? Viruses 2019;12:1–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graus F, Delattre JY, Antoine JC, et al. Recommended diagnostic criteria for paraneoplastic neurological syndromes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004;75:1135–1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.