Abstract

Objective

To determine the impact of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tubes in patients with advanced Huntington disease (HD).

Methods

A retrospective chart review of patients with HD was conducted to assess the rate of pneumonia and pressure ulcer, length of life, changes in weight, and serologic nutritional measures. Surviving and deceased patients with and without PEG tubes were compared using descriptive statistical analysis.

Results

One hundred forty-eight records were reviewed (39 patients with PEG tubes). The mean age of patients still alive and diagnosed with HD was 58.3 ± 12.7 years and age at death (n = 62) 57.7 ± 10.3 years. At the time of analysis, the mean duration of HD was 14.2 ± 7 years. Groups were similar in sex, age, and weight at admission. In those deceased, insertion of a PEG tube increased the length of life with HD by 3.6 years (16.2 ± 6.7 vs 13.2 ± 4.9 years). PEG tube placement significantly reduced cholesterol levels, increased the prevalence of skin ulcers and the rate of pneumonia. Insertion of a PEG tube did not significantly change weight or albumin levels.

Conclusions

PEG tube placement in advanced HD provided benefit in the length of life, but weight, other nutritional measures, and the rate of pneumonia were either not impacted or worsened with the insertion of a PEG tube. Impact on quality of life needs further study, but providers, patients, and families should consider all options when discussing preferences for interventions.

Classification of Evidence

This study provides Class IV evidence that for patients with advanced HD, PEG tube placement increases the length of life but has no or negative impacts on nutritional measures.

Huntington disease (HD) is a fatal hereditary neurodegenerative disorder characterized by progressive motor and cognitive symptoms.1 Symptom onset typically occurs around 30–40 years of age, and death occurs 10–25 years after the first onset of symptoms.2 Cognitive decline and motor dysfunction can result in dysphagia and loss of independent feeding. Loss of motor control may lead to difficulty closing lips, chewing, moving the tongue, moving the food bolus properly in the mouth and pharynx, and difficultly coordinating respiratory musculature, leading to choking, dysphagia, or aspiration while eating.3-5 Mechanical problems with eating and an increased metabolic rate in HD may lead to weight loss, which in turn may worsen motor aspects of HD, leading to a vicious negative cycle. There are few therapeutic options studied for dysphagia, but patients and families are often given the option of artificial nutrition and hydration (ANH) through the use of a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube, assuming that it will help patients receive proper nutrients.6,7

There are no studies of PEG tubes' placement frequency, effectiveness, or impact in HD. In other CNS-based neurodegenerative disorders, studies indicate that ANH through PEG tubes may not improve malnutrition, reduces frequency of aspiration, length of survival, comfort, or functional status, and may increase the risk of pneumonia.8 Through a retrospective chart review, this study assessed whether the use of PEG tubes changed the length of life and rate of aspiration pneumonia or affected the nutritional status of patients with advanced HD.

Methods

The objective of this study was to determine how a PEG tube affects patients with advanced HD based on a retrospective chart review. The data for this study were obtained from a single center that cares for patients with advanced HD, Tewksbury Hospital in Tewksbury, MA. The years included were 2001–2018. The data were collected using a chart review of living and deceased patients who had been admitted for any length of time with the diagnosis of HD. Patients were typically in the hospital for at least several years, but the range varied from months to decades. Clinical variables collected included the following: demographic information, weight (at admission, before PEG tube placement, and most recent/closest to death) and, if relevant, age at death. The cause of death was determined by the local treating clinicians. Laboratory measures collected most relevant to nutritional status and available for most patients included serum albumin levels (prealbumin values were not available) and total cholesterol. All laboratory test results are reported as mean ± SD unless stated otherwise. Other contributing factor data collected included diet consistency, appetite stimulant use in the form of prescription medications, and PEG tube placement data. Clinical measures included pneumonia types and frequency, presence and severity of skin ulcers, length of life, and weight.

The majority of the data for this retrospective chart review are descriptive. Statistical analysis was completed to compare the clinical differences between patients living and deceased and those with and without PEG tube placement. For between-group analyses, independent samples t tests and χ2 test for independence were performed. For within-group analyses, paired samples t tests were performed.

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

Before study data collection, IRB approval was obtained from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Office of Data Management and Outcomes Assessment run by the Department of Public Health.

Data Availability

Any data not published within the article are available as anonymized data on request from any qualified investigator.

Results

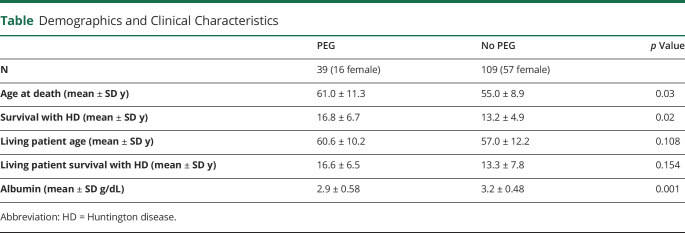

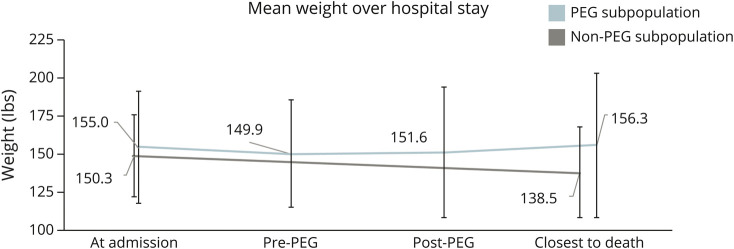

Between the years of 2001 and 2018, 148 patients with HD were admitted to Tewksbury Hospital. Of those 148 patients, 39 received a PEG tube, and 109 received oral-only feedings (Table). At the time of data collection, the mean age (±SD) of living patients was 58.3 ± 12.7 years. Insertion of a PEG tube increased the number of years patients survived with symptoms of HD (Δ = 3.6 years, p = 0.02). Among the patients with a PEG tube, there was a higher history of skin ulcers (44% vs 12%, p < 0.001) and pneumonia (77% vs 35%, p < 0.001). Total serum cholesterol levels lowered after PEG tube placement (172.2 mg/dL ± 34.1 reduced to 150.5 mg/dL ± 23.4, p = 0.046) and remained lower than those without a PEG tube (180.9 mg/dL ± 45.7). Comparing weight before and after the PEG tube insertion, there was no significant difference between the starting and most recent weights of patients (Figure). Cytosine-adenine-guanine repeat was available for 46 (31%) patients. The range was 40–48 with a mean of 43 ± 2.2. Eleven of 109 patients without a PEG tube were prescribed a medication with known weight-increasing properties.

Table.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

Figure. Mean Weight Over Hospital Stay.

This figure illustrates the mean weight patterns of the subpopulations and that the insertion of a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube did not significantly affect weight.

Discussion

HD is a progressive disorder that ultimately leads to loss of function, including difficulty with swallowing and weight loss. Families and providers naturally feel increasing pressure to intervene as patients start to decline, particularly in more advanced disease. To date, it has been assumed that ANH improves nutritional status, lengthens life, and at least maintains quality of life. However, there have been no data to support these assumptions and guide patients, families, or providers in this decision-making process.9

The insertion of a PEG tube bypasses the oral cavity and provides hydration and nutrition directly into the gastrointestinal system, with the hope of reducing the rate of pneumonia and complications of malnutrition and immobility such as skin ulcers. In this retrospective chart review from 148 patients at a single hospital that cares for patients with advanced HD, overall, PEG tube placement in advanced HD provided benefit only in length of life, and we did not find reduced rates of pneumonia or complications of immobility. Multiple negative aspects of this procedure need to be considered when making decisions about whether to place a PEG tube, such as immediate surgical complications and longer-term issues that were seen in these data such as an increased rate of pneumonia. There are inherent limitations of this study related to identifying the rate of pneumonia because patients who undergo PEG tube placement likely have been assessed to have worse dysphagia and may be at a higher risk of pneumonia, which the PEG tube tubes do not fully mitigate. Because patients with a PEG tube placed live longer, there is a possibility that there were more opportunities for events such as pneumonia to occur. One further limitation of this retrospective chart review study is the possibility of an immortal-time bias. If death were to occur in between the diagnosis of HD and the PEG tube placement, the death would be considered in the no-PEG tube group. This immortal-time bias may result in longer survival until death in patients who had a PEG tube placed. We did not see a difference in weight or other measures of nutritional status based on the placement of a PEG tube.

When discussing whether a PEG tube should be placed in patients with HD, there are many factors families and providers should consider, including the increased length of life, lack of other clinical differences, and quality of life in advanced HD.10 The placement of a PEG tube does not entirely exclude the use of oral intake. Ceasing oral feedings (independent or with help) will likely reduce socialization opportunities. The actual act of eating also provides sensation of a basic human need of taste, temperature, and feel of food in the mouth. The data presented in this study support the idea that hand feeding is no more harmful or beneficial than inserting a PEG tube in patients with HD.

If maintaining or increasing weight is the goal of therapy, methods beyond the insertion of a PEG tube should be discussed. Behavioral interventions can be implemented, such as offering more frequent smaller, high calorie meals. Although there is limited evidence in HD, certain medications may increase appetite or cause weight gain; these include valproic acid, mirtazapine, megestrol acetate, olanzapine, or cannabinoids. One study also suggested that deutetrabenazine can increase weight.11 The involvement of a speech and swallow therapist as well as nutritionists who can closely monitor patients may call attention to the issues and improve quality of life. In addition to the simple placement of a feeding tube, the idea of eating for pleasure should also be considered in patients who are having increasing difficulty with chewing, swallowing, and maintaining nutritional status.

The current reference points for swallowing and nutritional issues in HD are studies of PEG tube placement in other progressive neurologic diseases. In 1 study of 55 patients with dementia, after 6 months, there was a 44% mortality rate in patients with a PEG tube and a 26% rate in those without a PEG tube placed.12 In another study of patients with dementia, weight loss and pressure ulcer development increased because of the use of a feeding tube; a review of the literature concluded that there were no data to support the idea that enteral feeding provides clinically meaningful outcomes and risks are substantial.13,14 In patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), 13 of 63 ALS with a PEG tube had a weight loss of 10% or more of their body weight and a reduced length of life.15 Patients with HD are young, similar to the patients with ALS, but also have dementia, similar to the patients with Alzheimer disease.

Overall, if the preference of the patient and family is singularly focused on the goal to increase the length of life in advanced HD, a PEG tube may be helpful. However, quality of life and other medical issues should be considered, and preferences for nutritional options should ideally be discussed earlier in the course of HD, if possible. Future studies should be completed to confirm our findings to help guide clinical care over the course of decades of living with HD.

Appendix. Authors

Footnotes

Class of Evidence: NPub.org/coe

Contributor Information

Emma Frank, Email: emma.frank@uvm.edu.

Allison Dyke, Email: allisondyke@gmail.com.

Sarah MacKenzie, Email: smackenz@bidmc.harvard.edu.

Evagelia Maskwa, Email: emaskwa@bidmc.harvard.edu.

Study Funding

This work was supported in part by the More Fives Fund (morefives.org/).

Disclosure

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

References

- 1.Roos RAC. Huntington's disease: a clinical review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodrigues FB, Abreu D, Damásio J, et al. Survival, mortality, causes and places of death in a European Huntington's disease prospective cohort. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2017;4(5):737-742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heemskerk AW, Roos RAC. Aspiration pneumonia and death in Huntington's disease. PLoS Curr. 2012;4:RRN1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kagel MC, Leopold NA. Dysphagia in Huntington's disease: a 16-year retrospective. Dysphagia. 1992;7(2):106-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heemskerk AW, Roos RAC. Dysphagia in Huntington's disease: a review. Dysphagia. 2011;26(1):62-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solberg OK, Filkukovà P, Frich JC, Feragen KJB. Age at death and causes of death in patients with Huntington disease in Norway in 1986-2015. J Huntingtons Dis. 2018;7(1):77-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cervo FA, Bryan L, Farber S. To PEG or Not to PEG: A Review of Evidence for Placing Feeding Tubes in Advanced Dementia and the Decision-Making Process. Geriatrics;. 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murphy LM, Lipman TO. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy does not prolong survival in patients with dementia. Arch Intern Med. 2003;20(24):7739-7751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ekberg O, Hamdy S, Woisard V, Wuttge-Hannig A, Ortega P. Social and psychological burden of dysphagia: its impact on diagnosis and treatment. Dysphagia. 2002;17(2):139-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stewart C. Dysphagia symptoms and treatment in Huntington's disease: review. Perspect Swallowing Swallowing Disord. 2012;21:126-134. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frank S, Testa CM, Stamler D, et al. Effect of deutetrabenazine on chorea among patients with Huntington disease : a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316(1):40-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nair S, Hertan H, Pitchumoni CS. Hypoalbuminemia is a poor predictor of survival after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in elderly patients with dementia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(1):133-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horn SD, Bender SA, Ferguson ML, et al. The national pressure ulcer long-term care study: pressure ulcer development in long-term care residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(3):359-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finucane TE, Christmas C, Travis K. Tube feeding in patients with advanced dementia: a review of the evidence. J Am Med Assoc. 1999;282(14):1365-1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Limousin N, Blasco H, Corcia P, et al. Malnutrition at the time of diagnosis is associated with a shorter disease duration in ALS. J Neurol Sci. 2010;297(1-2):36-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Any data not published within the article are available as anonymized data on request from any qualified investigator.