Abstract

Purpose

Up to 44% of individuals with bulimia nervosa (BN) experience worsening of symptoms after cognitive behavior therapy (CBT). Identifying risk for post-treatment worsening of symptoms using latent trajectories of change in eating disorder (ED) symptoms during treatment could allow for personalization of treatment to improve long-term outcomes

Methods

Participants (N = 56) with BN-spectrum EDs received 16 sessions of CBT and completed digital self-monitoring of eating episodes and ED behaviors. The Eating Disorder Examination was used to measured ED symptoms at post-treatment and 3-month follow-up. Latent growth mixture modeling of digital self-monitoring data identified latent growth classes. Kruskal–Wallis H tests examined effect of trajectory of change in ED symptoms on post-treatment to follow-up symptom change.

Results

Multi-class models of change in binge eating, compensatory behaviors, and regular eating improved fit over one-class models. Individuals with high frequency-rapid response in binge eating (H(1) = 10.68, p =0 .001, η2 = 0.24) had greater recurrence of compensatory behaviors compared to individuals with low frequency-static response. Individuals with static change in regular eating exhibited greater recurrence of binge eating than individuals with moderate response (H(1) = 8.99, p = 0.003, η2 = 0.20).

Conclusion

Trajectories of change in ED symptoms predict post-treatment worsening of symptoms. Personalized treatment approaches should be evaluated among individuals at risk of poor long-term outcomes.

Level of evidence

IV, evidence obtained from multiple time series.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov registration number NCT03673540, registration date: September 17, 2018.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40519-021-01348-5.

Keywords: Bulimia nervosa, Binge eating, Compensatory behaviors, Cognitive-behavior therapy, Treatment outcome

Introduction and aims

Although cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT), the most evidence-based treatment for bulimia nervosa (BN), is moderately effective in achieving symptom reduction at post-treatment, 28–44% of individuals experience post-treatment recurrence of symptoms [1, 2]. Detecting risk for post-treatment worsening of symptoms (i.e., an increase in frequency of binge eating or compensatory behaviors and/or reduction in regular eating following treatment completion) early in treatment could inform clinical decision-making and personalized treatment approaches to improve long-term outcomes (e.g., introduction of supplemental treatment components, increased treatment duration or frequency).

There is relatively limited previous research on predictors of symptom change following treatment in BN. Recent literature has identified that high baseline symptom severity, low motivation for change, and high post-treatment preoccupation with eating predict post-treatment relapse [1, 2]. These identified predictors of poor post-treatment prognosis are difficult or impossible to intervene on (e.g., baseline symptom severity) or rely on post-treatment metrics (at which point it is too late to adjust the treatment approach).

Post-treatment outcomes may be more effectively predicted during treatment by examining trajectories of symptom change [3]. Rapid treatment response, typically defined as a reduction of ≥ 65% in binge eating and/or compensatory behaviors by week four of treatment, has been robustly linked to end-of-treatment remission among individuals with eating disorders [EDs; 4], but the association with longer-term outcomes has been mixed [5]. Further, research on early response has typically considered early response to be present or absent, thus examining only two trajectories of treatment response. There may be more than two distinct change trajectories and examining trajectories of change in behavioral ED symptoms individually may identify more complex patterns of treatment response (e.g., individuals may have rapid decline in binge eating but slower decline in compensatory behaviors). Although rapid response may be most strongly associated with post-treatment remission, slower but sustained trajectories of symptom change may also be associated with acquisition of treatment skills and positive long-term outcomes, whereas static change in symptoms may be indicative of poor skill acquisition and long-term outcomes. Examination of latent trajectories of change may provide more information about long-term prognosis than rapid response status alone.

Only one previous study has examined trajectories of change predicting outcome at follow-up in binge-spectrum EDs [6]. This study identified a three-class model of early change in binge eating among individuals with binge eating disorder (BED). The model included a “low level binge eating stable” class, a “low level binge eating decreasing class”, and a “medium level binge eating decreasing” class, characterized by an average of 2.66, 2.05, and 6.15 binge eating episodes per week at pre-treatment, respectively. The model was associated with remission at 6-month follow-up, with significantly lower remission rates in the “medium level binge eating decreasing” class compared to the other classes. The study also found that latent class analysis was superior to traditionally defined rapid response for predicting remission rates. Findings from this study in BED substantiate that trajectories of change in binge eating can predict post-treatment outcomes, suggesting that latent trajectories of change should be further examined in other ED populations.

The limited research examining trajectories of change in ED symptoms during treatment may be partially due to lack of access to the necessary data. The extant research examining trajectories of symptom change during CBT has exclusively utilized periodic self- or therapist-reported data [e.g., 6]. The use of electronic self-monitoring records allows for daily collection of symptom information throughout treatment, which is likely more accurate and comprehensive than weekly self- or therapist-reported data.

This preliminary study aimed to (1) identify latent trajectories of change in binge eating, compensatory behaviors, and regular eating during 16 weeks of CBT in individuals with BN-spectrum EDs using digital self-monitoring data and (2) examine the association between trajectories of change in ED symptoms during treatment and early change in binge eating, compensatory behaviors, or cognitive ED pathology from post-treatment to 3-month follow-up.

Methods

Participants

Participants (N = 56) were adults participating in a treatment study for BN-spectrum disorders. Eligibility criteria were: 18–70 years old, BMI ≥ 17.5 kg/m2, ≥ 12 objectively or subjectively large binge eating episodes, and ≥ 12 compensatory behaviors in the past 3 months. Exclusion criteria were: current or planned pregnancy, previous trial of CBT for BN, unstable psychiatric medication, concurrent ED treatment, previous bariatric surgery, and severe comorbid psychopathology (e.g., psychotic disorder).

The sample was 83.6% female and 65.4% White, 9.1% Black, 7.3% Asian and 18.1% multiracial or other. Average age was 38.5 years old (SD = 13.8). Average BMI was 29.5 kg/m2 (SD = 6.8). Although the inclusion criteria for BMI were ≥ 17.5 kg/m2, all participants had BMI > 18.5. Most of the sample (92.9%) met DSM-5 behavioral criteria for BN and 7.1% met criteria for another BN-spectrum ED (e.g., BN with subjectively large binge episodes).

Procedures

The present study is a secondary data analysis of a trial examining the efficacy of a smartphone application as an adjunct to CBT for BN-spectrum EDs (see [7] for a description of the treatment and smartphone application). Participants were recruited from the Philadelphia area (pre-COVID-19 pandemic; n = 51) and nationally (during COVID-19 pandemic; n = 5). National recruitment began during COVID-19 to facilitate recruitment of the full sample within the funding period, as all study procedures were remote. Participants provided informed consent and completed a baseline assessment to confirm eligibility. Assessment procedures, conducted at baseline, mid-treatment, post-treatment, and 3-month follow-up, included an ED diagnostic interview (i.e., the Eating Disorder Examination [EDE; 8]), self-report measures, and behavioral tasks. Participants received 16 sessions of outpatient CBT (n = 613 sessions in-person; n = 227 sessions over Zoom) based on the focused version of CBT-E [9] while completing digital self-monitoring records to track eating episodes and ED behaviors (see [7]). Participants in the experimental condition (n = 29) received just-in-time adaptive interventions reminding them to practice therapeutic skills (see [7]), while participants in the control condition (n = 26) did not receive just-in-time adaptive interventions. One participant received some, but not all relevant just-in-time adaptive interventions, and therefore was excluded from analyses. Treatment outcomes (binge episodes, compensatory behaviors, and EDE global scores) did not differ by treatment delivery modality (baseline to post-treatment mixed factorial ANOVA ps = 0.18–0.76, ηp2s = 0.002–0.04). Trajectory of change membership proportions did not significantly differ by treatment delivery modality (Fisher’s exact test ps = 0.38–1.00).

Statistical analysis

Latent growth mixture modeling (LGMM) was conducted on self-monitoring data to examine unobserved trajectories of change in binge eating, compensatory behaviors, and episodes of ≥ five waking hours without eating during treatment using the ‘hlme’ function in the ‘lcmm’ package in R [10]. Binge eating, compensatory behaviors, and episodes of five or more hours without eating across treatment were not normally distributed. Therefore, before conducting LGMM these variables were normalized using the ‘lcmm’ package (see [11] and [12] for more detail). Baseline age, body mass index, and treatment condition were included as fixed effects in the generated growth mixture models One- to four-class mixed effects growth models were fitted. LGMM was conducted with random intercepts and random slopes to maximize model fit. Initial start values were based on the one-class model and each model was estimated 100 times. Fixed and random intercepts and linear and quadratic effects of time on ED symptoms were estimated for all models. Best-fit models were selected by minimizing the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and the Akaike information criterion (AIC; [13]); when the BIC and AIC disagreed, minimizing BIC was prioritized [14]. Class membership was assigned using posterior probabilities and entropy was examined as a marker of class separation. Given variability in inter-session period length, the number of reported ED symptoms in a given inter-session period was divided by total days in the inter-session period and multiplied by seven to estimate the number of ED symptoms in a standardized week. Latent trajectories were not fitted for two participants due to missing digital self-monitoring data after period 1. Latent classes were labeled in terms of baseline frequency (number of behaviors reported during the first week) and rate of treatment response. Baseline frequency thresholds were based on the DSM-5 severity criteria for BN as follows: low frequency < 4 episodes/week, moderate frequency 4–7 episodes/week, high frequency 8–13 episodes/week, extreme frequency > 13 episodes/week. Rate of responses were considered static if the linear time coefficient was < 0.2, moderate if the linear time coefficient was ≥ 0.2 but < 0.4, and rapid if the linear time coefficient was ≥ 0.4. These thresholds were chosen as they correspond to reductions of three behaviors per week (static response), six behaviors per week (moderate response), and > six behaviors per week (rapid response) by end of treatment, which corresponds to the difference between moderate and low severity (three behaviors) and between severe and moderate BN (six behaviors), respectively.

Change scores from post-treatment to follow-up were computed from EDE data for past-month binge eating frequency, compensatory behavior frequency, and EDE global scores. Kruskal–Wallis H tests examined the effect of growth class on change in ED symptoms from post-treatment to follow-up given non-normality of change scores. Power analyses conducted utilizing the ‘MultNonParam’ package and ‘kweffectsize’ function in R with alpha = 0.05 and power = 0.80 indicate that the study was powered to detect differences of large effect size for trajectories of change in binge eating, small for trajectories in compensatory behaviors, and medium effect size for trajectories in regular eating. p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

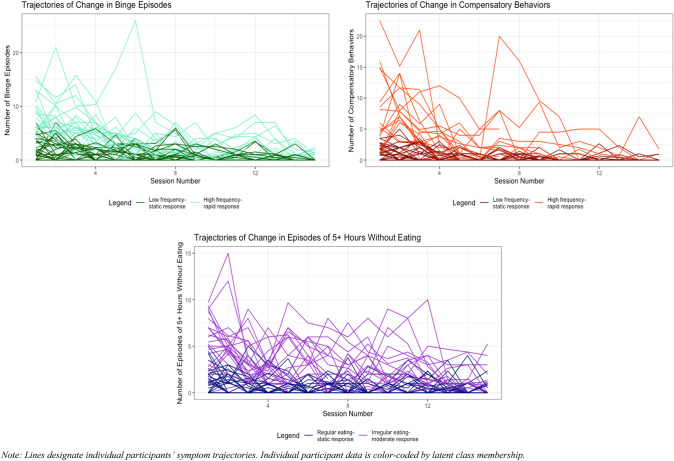

Results

LGMM indicated that a two-class model of change in binge eating, a two-class model of change in compensatory behaviors, and a two-class model of change in regular eating best fit the data (see Table 1 and Fig. 1). All best-fit models demonstrated adequate class separation (entropy ≥ 0.70) and average posterior probability (mean posterior probability ≥ 0.80). The binge eating classes (Class 1: low frequency-static response, Class 2: high frequency-rapid response) differed in both baseline frequency (MBinge Class 1 = 2.15; MBinge Class 2 = 7.63) and rate of decrease in binge eating over time, with Class 2 demonstrating much greater decrease than Class 1. The compensatory behaviors classes (Class 1: low frequency-static response, Class 2: high frequency-rapid response) differed on baseline frequency (MCompensatory Behavior Class 1 = 1.01; MCompensatory Behavior Class 2 = 7.54) and rate of change during treatment. The regular eating classes (Class 1: regular eating-static response, Class 2: irregular eating-moderate response) differed on frequency of ≥ five waking hours without eating at baseline (MRegular Eating Class 1 = 1.33; MRegular Eating Class 2 = 5.57) and change in regular eating over time. Table 1 depicts LGMM fit statistics, model estimates, treatment outcomes, and associations between BN symptom change trajectories and symptom change from post-treatment to follow-up.

Table 1.

Best-fit models of change in binge eating, compensatory behaviors, and episodes of 5 + hours without eating and their associations with relapse

| Fit indices and growth model parameter estimates for best-fit models of change | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binge eating episodes | |||||||||

| Number of classes | Number of parameters | Max. log-likelihood | BIC | SABIC | AIC | Entropy | Class membership Proportions % (N) | Mean posterior probability | % posterior probability > 0.80 |

| 2 | 21 | − 1132.07 | 2347.52 | 2281.56 | 2306.15 | 0.72 |

1:54.7% (29) 2:45.3% (24) |

1:0.87 2:0.98 |

1:0.76 2:0.96 |

| Fixed effects: class membership model | Fixed effects: longitudinal model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept Est. (SE), p |

Intercept Est. (SE), p |

Linear time Est. (SE), p |

Quadratic time Est. (SE), p |

|

| Class 1: low frequency-static response | − 0.05 (0.34), .88 | 1.22 (0.36), <.001*** | − 0.18 (0.07), .01* | 0.01 (0.00), .10 |

| Class 2: high frequency-rapid response | Not estimated, reference class | 3.20 (0.99), .001** | − 0.64 (0.14), <.001*** | 0.02 (0.01), <.001*** |

| Treatment outcome variable | Class 1 baseline mean (SD) | Class 2 baseline mean (SD) | Class 1 post-treatment mean (SD) | Class 2 post-treatment mean (SD) | Class 1 follow-up mean (SD) | Class 2 follow-up mean (SD) | F (p), ηp2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Past month binge episodes | 16.0 (10.20) | 38.10 (29.60) | 4.44 (9.29) | 4.38 (8.60) | 4.83 (8.48) | 7.17 (13.20) | 11.41 (<.001***), 0.22 |

| Past month compensatory behaviors | 27.70 (19.80) | 37.5 (30.80) | 9.04 (16.10) | 2.81 (10.40) | 7.75 (17.85) | 11.30 (21.20) | 7.03 (.004**), 0.15 |

| EDE global score | 2.97 (0.74) | 3.71 (1.07) | 1.71 (1.13) | 1.66 (1.23) | 1.61 (1.20) | 1.42 (1.21) | 6.86 (.005**), 0.15 |

| Compensatory behavior episodes | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of classes | Number of parameters | Max. log-likelihood | BIC | SABIC | AIC | Entropy | Class membership proportions % (N) | Mean posterior probability | % posterior probability > 0.80 |

| 2 | 21 | − 1110.07 | 2303.52 | 2236,56 | 2262.15 | 0.86 |

1:67.9% (36) 2:32.1% (17) |

1:0.97 2:0.97 |

1:0.97 2:0.94 |

| Fixed effects: class membership model | Fixed effects: longitudinal model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept Est. (SE), p |

Intercept Est. (SE), p |

Linear time Est. (SE), p |

Quadratic time Est. (SE), p |

|

| Class 1: low frequency-static response | 0.71 (0.32), .02* | − 1.35 (0.32), <.001*** | − 0.14 (0.04), .002** | 0.01 (0.00), .02* |

| Class 2: high frequency-rapid response | Not estimated, reference class | 3.47 (1.14), .002** | − 0.90 (0.19), <.001*** | 0.04 (0.01), <.001*** |

| Treatment outcome variable | Class 1 baseline mean (SD) | Class 2 baseline mean (SD) | Class 1 post-treatment mean (SD) | Class 2 post-treatment mean (SD) | Class 1 follow-up mean (SD) | Class 2 follow-up mean (SD) | F (p), ηp2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Past month binge episodes | 19.20 (15.90) | 40.50 (30.90) | 2.68 (5.48) | 8.64 (13.50) | 3.86 (8.08) | 10.23 (14.44) | 5.94 (.01*), 0.13 |

| Past month compensatory behaviors | 21.20 (12.60) | 55.30 (30.80) | 2.97 (7.36) | 14.40 (22.00) | 3.83 (7.92) | 21.46 (29.65) | 9.77 (<.001***), 0.20 |

| EDE global score | 3.22 (0.83) | 3.48 (1.23) | 1.51 (0.98) | 2.13 (1.47) | 1.41 (1.08) | 1.79 (1.42) | 1.57 (.22), 0.04 |

| Episodes of 5 + hours without eating | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of classes | Number of parameters | Max. log-likelihood | BIC | SABIC | AIC | Entropy | Class membership proportions % (N) | Mean posterior probability | % posterior probability > 0.80 |

| 2 | 21 | − 1142.98 | 2369.33 | 2303.37 | 2327.95 | 0.87 |

1:58.5% (31) 2:41.5% (22) |

1:0.95 2:0.99 |

1:0.94 2:1.00 |

| Fixed effects: class membership model | Fixed effects: longitudinal model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept Est. (SE), p |

Intercept Est. (SE), p |

Linear time Est. (SE), p |

Quadratic time Est. (SE), p |

|

| Class 1: regular eating-static response | 0.23 (0.30), .46 | − 1.76 (0.30), <.001*** | − 0.13 (0.05), .01* | 0.01 (0.00), .06 |

| Class 2: irregular eating-moderate response | Not estimated, reference class | 1.34 (1.12), <.001*** | − 0.37 (0.17), .03* | 0.01 (0.01), .29 |

| Treatment outcome variable | Class 1 baseline mean (SD) | Class 2 baseline mean (SD) | Class 1 post-treatment mean (SD) | Class 2 post-treatment mean (SD) | Class 1 follow-up mean (SD) | Class 2 follow-up mean (SD) | F (p), ηp2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Past month binge episodes | 23.80 (24.60) | 29.10 (22.80) | 5.14 (9.33) | 3.32 (8.33) | 9.16 (12.80) | 0.94 (2.22) | 1.40 (.25), 0.03 |

| Past month compensatory behaviors | 33.60 (29.60) | 30.10 (19.10) | 7.72 (13.60) | 4.16 (15.00) | 12.32 (19.34) | 4.82 (18.63) | 0.37 (.62), 0.01 |

| EDE global score | 3.21 (0.84) | 3.44 (1.14) | 1.83 (1.11) | 1.48 (1.24) | 1.75 (1.11) | 1.20 (1.27) | 1.76 (.19), 0.04) |

| Associations between trajectories of change in eating disorder symptoms and relapse from post-treatment to 3-month follow-up | ||

|---|---|---|

| Post-treatment change variable | Kruskal–Wallis H Test | η2 |

| Binge eating trajectory | ||

| Binge eating | H(1) = 0.004, p = .95 | 0.00 |

| Compensatory behaviors | H(1) = 10.68, p = .001** | 0.24 |

| EDE global score | H(1) = 1.34, p = .25 | 0.01 |

| Compensatory behavior trajectory | ||

| Binge eating | H(1) = 2.53, p = .11 | 0.04 |

| Compensatory behaviors | H(1) = 0.26, p = 61 | 0.00 |

| EDE global score | H(1) = 0.07, p = .79 | 0.00 |

| Regular eating trajectory | ||

| Binge eating | H(1) = 8.99, p = .003** | 0.20 |

| Compensatory behaviors | H(1) = 0.55, p = .46 | 0.00 |

| EDE global score | H(1) = 0.22, p = .64 | 0.00 |

BIC Bayesian information criterion, SABIC sample-size adjusted Bayesian information criterion, AIC Akaike information criterion, Est. estimate, SE standard error, η2 eta squared, a measure of effect size for Kruskal–Wallis H Test (η2 > 0.01 = small effect, 0.06 < η2 < 0.14 = medium effect, η2 > 0.14 = large effect)

*Designates significance at the p < 0.05 level, **designates significance at the p < 0.01 level, ***designates significance at the p < 0.001 level

Fig. 1.

Latent trajectories of change in eating disorder symptoms across 16 sessions of CBT. Lines designate individual participants’ symptom trajectories. Individual participant data are color-coded by latent class membership

Trajectory of change in binge eating was significantly associated with post-treatment worsening of compensatory behaviors with large effect size (see Table 1). Individuals with high frequency-rapid response in binge eating demonstrated significantly larger post-treatment increases in compensatory behaviors (Mchange = 9.41, SDchange = 17.20) than individuals with low frequency-static response in binge eating (Mchange = − 1.00, SDchange = 10.50). Trajectory of change in regular eating was significantly associated with worsening of binge eating (see Table 1). The regular eating-static response class demonstrated significantly greater post-treatment increase in binge eating (Mchange = 5.20, SDchange = 14.70) than the irregular eating-moderate response class (Mchange = − 1.71, SDchange = 8.92). Worsening of cognitive ED pathology (measured by EDE global score) did not differ by behavioral trajectories of change.

Discussion

Outpatients with BN-spectrum EDs demonstrate heterogeneous trajectories of change in behavioral ED symptoms during CBT and these change trajectories differentially predict post-treatment change in binge eating and compensatory behaviors. Individuals with highly irregular eating (i.e., ≥ five waking hours without eating ~ five times/week) at baseline and moderately rapid improvements in regular eating during treatment demonstrated much lower recurrence of binge eating than individuals with regular eating at baseline (i.e., ≥ five waking hours without eating ~ one time/week) and static change. Individuals with high baseline frequency and rapid response in binge eating (i.e., ~ eight episodes of binge eating/week) during CBT demonstrated larger post-treatment increases in compensatory behaviors than individuals demonstrating low baseline frequency and static response in binge eating. The impact of binge eating class on post-treatment symptom change is consistent with Hilbert et al.’s [6] findings that higher baseline frequency of binge eating was associated with poorer outcome at follow-up.

Results of this study indicate that while CBT for BN can be very effective for individuals with highly irregular eating at baseline, it may yield poorer long-term outcomes for individuals not engaging in significant dietary restraint between binge eating/compensatory behavior episodes. Individuals with low baseline levels of dietary restraint and static response may primarily engage in binge eating in reaction to internal or external cues, like negative affect or presence of palatable foods. The relatively high recurrence in binge eating among these individuals may indicate that CBT insufficiently targets these precursors to binge eating.

Analogously, although CBT may be effective in reducing compensatory behaviors during treatment for individuals with high baseline frequency of binge eating, the high recurrence in compensatory behaviors noted for these individuals suggests CBT may fail to adequately address key maintenance factors for compensatory behaviors. Individuals in the high frequency-rapid response trajectory of binge eating may engage in compensatory behaviors for a number of reasons, including controlling shape or weight, for affect regulation, to reduce intolerable interoceptive sensations, or as a habitual reaction to binge eating episodes. These individuals may demonstrate good treatment response due to non-specific treatment factors such as supportive accountability to a therapist, but given that these factors do not persist after treatment, they may experience recurrence of compensatory behaviors when treatment ends. For instance, individuals may be more motivated to tolerate feelings of fullness or negative affect and avoid purging when their therapist will monitor engagement in compensatory behaviors than when they no longer experience supportive accountability.

These findings preliminarily suggest that identification of an individual’s trajectory of change in ED symptoms during CBT for BN may facilitate personalized interventions to improve long-term outcomes. Clinicians should be cautioned against assuming that rapid changes in ED behaviors during treatment will necessarily yield long-term improvements in symptoms for individuals with BN undergoing CBT. Individuals may demonstrate rapid change in ED symptoms during treatment for many reasons (e.g., elevated hope and motivation, supportive accountability). Following treatment, these factors may subside, putting the individual at risk for BN symptom recurrence. Clinicians should work with individuals exhibiting reductions in binge eating and compensatory behaviors and individuals with static change in regular eating to collaboratively determine factors that may put these individuals at risk for post-treatment worsening of symptoms. For instance, even if an individual has demonstrated a significant decrease in binge eating and compensatory behaviors during treatment, they may still have elevated shape or weight concerns, difficulty regulating affect, or intolerance of fullness and these factors may need to be addressed more thoroughly to prevent future recurrence of compensatory behaviors. Additional psychological interventions that could address maintenance factors for ED behaviors that are not a focus of CBT (e.g., exposure for intolerable interoceptive sensations, emotion regulation strategies to replace the affect regulatory function of ED behaviors, planning for ongoing supportive accountability after treatment) should be considered as augmentations. Further research should evaluate whether individuals demonstrating high-risk trajectories of ED symptom change have better long-term outcomes when receiving personalized treatments that incorporate supplemental strategies.

Strengths and limits

This study was the first to examine latent trajectories of change in binge eating, compensatory behaviors, and regular eating during CBT for BN. Strengths of the study were the use of the EDE to measure ED symptoms and the use of daily self-monitoring data to identify latent trajectories of change, which promoted ecological validity and minimized recall bias. Another strength of the study is the use of a data-driven analytic approach to identify latent trajectories. The study was limited by the small sample size, limiting power. Although digital self-monitoring data are likely more accurate than weekly self-report or therapist report, long-term use of self-monitoring demonstrates some decline in compliance. Finally, therapy was initially administered in-person but later transitioned to Zoom during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have impacted treatment response. This is a particularly major limitation, given preliminary evidence that CBT for BN may be less effective when delivered via telehealth [15]. It is possible that individuals receiving telehealth therapy may have had poorer treatment response due to factors such as inhibited therapeutic alliance or reduced supportive accountability. Additionally, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic may have contributed to increased symptoms during or following treatment for some individuals due to increased psychological stress and changes to food environments.

This study preliminarily suggests that individuals with BN-spectrum EDs demonstrate heterogeneous trajectories of change in ED symptoms during treatment. These trajectories differentially predict change in binge eating and compensatory behaviors in the post-treatment period. Future research should replicate these findings and examine whether personalized treatment approaches improve long-term outcomes.

What is already known on this subject?

Previous research suggests that individuals with eating disorders exhibit heterogeneous trajectories of symptom change during treatment. These trajectories may be associated with post-treatment outcomes.

What this study adds?

The present study is the first to examine trajectories of change in binge eating, compensatory behaviors, and regular eating during CBT for bulimia nervosa. These trajectories may differentially predict post-treatment worsening of bulimia symptoms.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

Emily K. Presseller contributed to study design, data analysis, and writing and editing of the manuscript. Elizabeth W. Lampe, Megan L. Michael, Claire Trainor, and Stephanie C. Fan contributed to writing and editing of the manuscript. Adrienne S. Juarascio contributed to study design and editing of the manuscript.

Funding

The parent study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (Grant number: R34MH116021).

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethics approval

The parent study procedures were approved and overseen by the Drexel University Institutional Review Board.

Informed consent

Informed consent was provided by all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Halmi KA, Agras WS, Mitchell J, Wilson GT, Crow S, Bryson SW, Kraemer H. Relapse predictors of patients with bulimia nervosa who achieved abstinence through cognitive behavioral therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(12):1105–1109. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.12.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olmsted MP, MacDonald DE, McFarlane T, Trottier K, Colton P. Predictors of rapid relapse in bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2015;48(3):337–340. doi: 10.1002/eat.22380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Melchior H, Schulz H, Kriston L, Hergert A, Hofreuter-Gatgens K, Bergelt C, Morfeld M, Koch U, Watzke B. Symptom change trajectories during inpatient psychotherapy in routine care and their associations with long-term outcomes. Psychiatry Res. 2016;238:228–235. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linardon J, Brennan L, De la Piedad GX. Rapid response to eating disorder treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Eat Disord. 2016;49(10):905–919. doi: 10.1002/eat.22595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thompson-Brenner H, Shingleton RM, Sauer-Zavala S, Richards LK, Pratt EM. Multiple measures of rapid response as predictors of remission in cognitive behavior therapy for bulimia nervosa. Behav Res Ther. 2015;64:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hilbert A, Herpertz S, Zipfel S, Tuschen-Caffier B, Friederich H-C, Mayr A, Crosby RD, de Zwaan M. Early change trajectories in cognitive-behavioral therapy for binge-eating disorder. Behav Ther. 2019;50(1):115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2018.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Juarascio A, Srivastava P, Presseller E, Clark K, Manasse S, Forman E. A clinician-controlled just-in-time adaptive intervention system (CBT+) designed to promote acquisition and utilization of cognitive behavioral therapy skills in bulimia nervosa: development and preliminary evaluation study. JMIR Form Res. 2021;5(5):e18261. doi: 10.2196/18261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, O’Connor M (2014) Eating disorder examination. Centre for Research on Eating Disorders at Oxford (CREDO)

- 9.Fairburn CG. Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Proust-Lima C, Philipps V, Liquet B. Estimation of extended mixed models using latent classes and latent processes: the R package lcmm. J Stat Softw. 2017;78(2):1–56. doi: 10.18637/jss.v078.i02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Philipps V, Amieva H, Andrieu S, Dufouil C, Berr C, Dartigues JF, Jacqmin-Gadda H, Proust-Lima C. Normalized Mini-Mental State Examination for assessing cognitive change in population-based brain aging studies. Neuroepidemiology. 2014;43(1):15–25. doi: 10.1159/000365637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pre-normalizing a dependent variable using lcmm. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/lcmm/vignettes/pre_normalizing.html#ces-d-example

- 13.Muthen B, Muthen LK. Integrating person-centered and variable-centered analyses: growth mixture modeling with latent trajectory classes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24(6):882–891. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2000.tb02070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthén BO. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: a monte carlo simulation study. Struct Equ Model. 2007;14(4):535–569. doi: 10.1080/10705510701575396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitchell JE, Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA, Crow S, Lancaster K, Simonich H, Swan-Kremeier L, Lysne C, Myers TC. A randomized trial comparing the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa delivered via telemedicine versus face-to-face. Behav Res Ther. 2008;46(5):581–592. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Not applicable.