Abstract

Winning the war against resistant bacteria will require a change of paradigm in antibiotic discovery. A promising new direction is the targeting of non-essential pathways required for successful infection, such as quorum-sensing, virulence, and biofilm formation. Similarly important will be strategies to prevent or revert antibiotic resistance. Here, we argue that the (p)ppGpp signaling pathway should be a prime target of this effort, since its inactivation could potentially achieve all these goals simultaneously. The hyperphosphorylated guanine nucleotide (p)ppGpp is an ancient and universal second messenger of bacteria that has pleotropic effects on the physiology of these organisms. Initially described as a stress signal—an alarmone—it is now clear that (p)ppGpp plays a more general and fundamental role in bacterial adaptation, by integrating multiple internal and environmental signals to establish the optimal balance between growth and maintenance functions at any given time. Given such centrality, perturbation of the (p)ppGpp pathway will affect bacteria in multiple ways, from the ability to adjust metabolism to the available nutrients to the capacity to differentiate into developmental forms adapted to colonize different niches. Here, we provide an overview of the (p)ppGpp pathway, how it affects bacterial growth, survival and virulence, and its connection with antibiotic tolerance and persistence. We will emphasize the dysfunctions of cells living without (p)ppGpp and finalize by reviewing the efforts and prospects of developing inhibitors of this pathway, and how these could be employed to improve current antibiotic therapy.

Keywords: Stringent response, (p)ppGpp, Persistence, Antibiotic tolerance, Anti-virulence

(p)ppGpp, a second messenger with a central role in bacterial adaptation

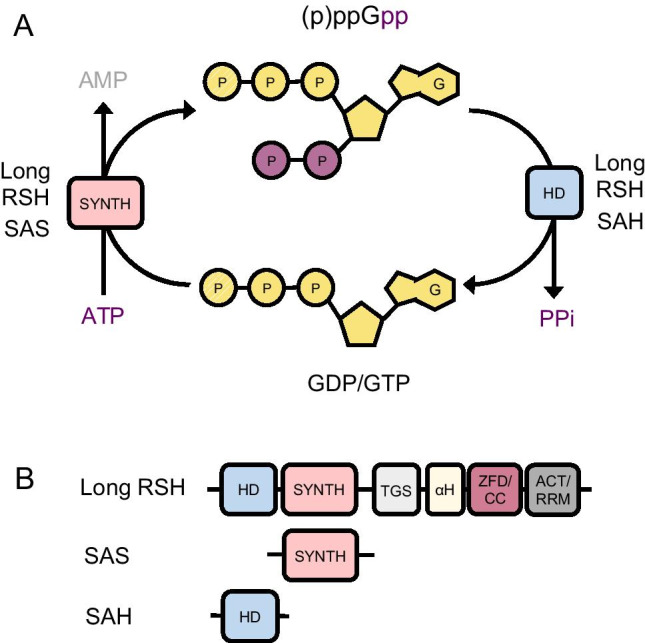

The nucleotide guanosine 3′,5′-bis(diphosphate) (ppGpp) and its pentaphosphate derivative pppGpp (collectively referred to as (p)ppGpp) (Fig. 1A) are ancient and ubiquitous signaling molecules of bacteria which occupy a deep-seated position in the circuitry used by these organisms to sense and respond to the environment (Mittenhuber 2001; Atkinson et al. 2011; Nelson and Breaker 2017). Initially identified as molecules that accumulated in response to acute amino acid starvation and called alarmones (Cashel and Gallant 1969), subsequent work showed that (p)ppGpp plays a more general and fundamental role in bacterial adaptation, being the molecules responsible for resource allocation and the establishment of the optimal balance between growth and maintenance functions at any given moment (Nyström 2004; Zhu et al. 2019). As such, (p)ppGpp will affect essentially every physiological process of bacteria, from the ability to use specific nutrients to the differentiation into complex developmental programs such as sporulation and virulence. Here, we will argue that the centrality of (p)ppGpp makes it an ideal target in the search for new and improved antibiotics. For the many other important research questions related to this pathway, the reader is referred to several excellent recent reviews (Gourse et al. 2018; Ronneau and Hallez 2019; Spira and Ospino 2020; Steinchen et al. 2020; Fernández-Coll and Cashel 2020; Irving et al. 2021; Bange et al. 2021).

Fig. 1.

Chemistry and enzymes involved in (p)ppGpp synthesis and degradation. A Synthesis and degradation of (p)ppGpp. The substrates for synthesis are ATP and GTP or GDP and the reaction is catalyzed by the synthetase domain (SYNTH) of long RSH and SAS enzymes. (p)ppGpp degradation occurs by hydrolysis of the 3′ pyrophosphate regenerating GTP/GDP. This reaction is catalyzed by the hydrolase domain (HD) of long RSH and SAH enzymes. B The RSH (RelA SpoT Homology) superfamily consists of long RSH, SAS (small alarmone synthetase) and SAH (small alarmone hydrolase) enzymes. Long RSHs have both a (p)ppGpp hydrolase domain (HD) and a (p)ppGpp synthetase domain (SYNTH) in their catalytic N-terminal half. In addition, long RSHs have a complex regulatory C-terminal half constituted of four domains: TGS (ThrRs, GTPase, and SpoT); αH (alpha helical); ZFD (zinc finger domain) or CC (conserved cysteine); and RRM (RNA recognition motif) or ACT (aspartokinase, chorismate mutase, and TyrA). SAS and SAH enzymes have a single catalytic domain, (SYNTH) and (HD) respectively

The sharp accumulation of (p)ppGpp in bacteria exposed to starvation or other stresses (pH, heat, antibiotics) is known as the stringent response. During the stringent response, intracellular accumulation of (p)ppGpp induces a dramatic reprogramming of gene expression and metabolism, with a sharp decrease in macromolecular synthesis (protein, rRNA, DNA, peptidoglycan, and lipid) associated with growth and the activation of general and specific stress responses that favor survival. In addition to acute stress situations, where high levels of (p)ppGpp basically act as an emergency brake, it is clear that this second messenger also plays an important role in adjusting bacterial physiology to smaller fluctuations in their environment, such as during a diauxic transition, and even during balanced growth in different media, where growth rate has been shown to inversely correlate with (p)ppGpp levels (Traxler et al. 2006; Gaca et al. 2013; Imholz et al. 2020; Fernández-Coll and Cashel 2020). The important role of so-called “basal” (p)ppGpp is also evident in the striking dysfunctionalities of cells that no longer make this signal, something that will be discussed at length in the next sections of this review.

Synthesis of (p)ppGpp involves the transfer of a pyrophosphate group of ATP onto the 3′OH of GDP or GTP, whereas degradation occurs by hydrolysis of the 3′ pyrophosphate moiety back to GDP or GTP (Fig. 1A). The intracellular balance of (p)ppGpp is controlled by the competing synthesis and hydrolysis activities of RSH (RelA SpoT Homology) superfamily enzymes. This superfamily encompasses both long bifunctional and short monofunctional enzymes. Long bifunctional RSH enzymes have a catalytic domain with independent synthesis and hydrolysis active sites and, thus, can both make and break (p)ppGpp. In contrast, monofunctional RSHs are small enzymes containing just a (p)ppGpp synthesis or hydrolysis domain and have been named SAS (small alarmone synthetases) or SAH (small alarmone hydrolases) (Fig. 1B). Typically, bacteria have a single bifunctional RSH, but in E. coli and related taxa a duplication event originated two enzymes—RelA and SpoT—with specialized functions. RelA is a strong ppGpp synthethase but lacks hydrolase activity, whereas SpoT is a weak synthetase but an effective ppGpp hydrolase (Mittenhuber 2001; Atkinson et al. 2011). The SASs and SAHs are found almost exclusively in Gram + bacteria, with most species having one or two SASs (usually named RelP and RelQ) in addition to one bifunctional RSH in their genomes (Atkinson et al. 2011). The SAHs have a more restricted distribution, being absent of most of the commonly studied bacteria (Atkinson et al. 2011).

(p)ppGpp exerts its pleiotropic effects by acting as an inhibitor or allosteric modulator of a large number of protein targets (Kanjee et al. 2012; Corrigan et al. 2016; Zhang et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2019) (Fig. 2). As expected of a GTP analog, it affects many GTPases, including the small GTPases involved in ribosome maturation and the translation factors IF-2, EF-G, and EF-Tu (Milon et al. 2006; Bennison et al. 2019; Diez et al. 2020). These interactions, together with the shut-off of rRNA transcription, account for the inhibition of protein synthesis promoted by (p)ppGpp. Other important targets are purine biosynthesis enzymes, whose inhibition results in a marked drop in intracellular GTP in response to (p)ppGpp accumulation, and DNA primase, which is one of the ways in which (p)ppGpp controls DNA replication (Sinha et al. 2020). (p)ppGpp also inhibits lipid and cell wall synthesis, although the enzymes affected in each case are still controversial (Noga et al. 2020). In addition, there are the effects of (p)ppGpp on gene expression. Recent RNAseq experiments showed that as many as a thousand genes are under the control of this second messenger (Sanchez-Vazquez et al. 2019; Horvatek et al. 2020). In addition to the hallmark reduction in transcription of stable RNAs (rRNA and tRNA), during the stringent response many other genes involved in growth are repressed, whereas genes involved in survival, stress resistance, and virulence are activated (Fig. 2). In E. coli and most proteobacteria, this reprogramming is the result of (p)ppGpp binding directly to RNA polymerase at two different sites, altering the efficiency of transcription initiation at different promoters (Gourse et al. 2018). However, in Gram + bacteria, (p)ppGpp does not bind to RNA polymerase and modulation of gene expression occurs indirectly, being a consequence of the reduction in intracellular GTP via two different mechanisms. Low intracellular GTP negatively affects the expression of genes that have G as the initiating NTP, among them the rRNA genes (Gourse et al. 2018). Low GTP also promotes the activation of genes under the control of CodY, a repressor whose binding to DNA is itself modulated by GTP (Geiger and Wolz 2014).

Fig. 2.

Activation of the stringent response and effects of (p)ppGpp on bacterial physiology. Long bifunctional RSHs are the main regulators of intracellular (p)ppGpp levels. The C-terminal is the part of the protein that senses metabolic conditions and transduces this information to the N-terminal catalytic domain, inducing it to adopt mutually exclusive conformations: when the synthesis site is properly formed, the hydrolysis is not, and vice versa. Accumulation of (p)ppGpp then modulates several pathways, via direct effects on enzyme targets and by reprogramming gene expression. We have highlighted the effects of (p)ppGpp that result in the shutdown of protein synthesis. They include the inhibition of translation factors and small GTPases involved in ribosome maturation, and a sharp reduction in rRNA and tRNA transcription. Another relevant effect not shown in the figure for simplicity is the expression of HPF, a protein that promotes ribosome dimerization (Irving et al. 2021). The combined result is a reduction in both the number or ribosomes per cell and in the rate of translation by these ribosomes

Long bifunctional RSHs are the main controllers of intracellular (p)ppGpp levels. These enzymes can switch between mutually exclusive synthesis and hydrolysis conformations depending on the signals detected by their C-terminal regulatory domain (Hogg et al. 2004; Tamman et al. 2020; Pausch et al. 2020) (Fig. 2). The signal detected by RSHs during amino acid starvation is the appearance of stalled ribosomes containing uncharged tRNAs in their A site. RSHs associate with stalled ribosomes via multiple contacts between the regulatory domain and the stalled ribosome, including a critical contact with the acceptor stem of tRNA that can only happen if the tRNA is uncharged. Within this ternary complex, the regulatory domain of RSH opens up, undergoing a large conformational change that is transmitted to the catalytic domain, switching it to a synthesis on/hydrolysis off state (Brown et al. 2016; Loveland et al. 2016; Arenz et al. 2016). The molecular details of how RSHs respond to other starvation and stress signals is an active area of investigation (Irving and Corrigan 2018; Ronneau and Hallez 2019). In Gram + bacteria, the SAS also play an important role in adjusting the basal (p)ppGpp pool and in responding to stresses that affect cell envelope integrity, including pH, ethanol, and cell wall antibiotics (Krishnan and Chatterji 2020). The SAS lack a regulatory domain; thus, their activity seems to be controlled predominantly at the expression level (Nanamiya et al. 2008; Libby et al. 2019). RSHs and some SAS (RelQ) are allosterically activated by their own product. Binding of ppGpp to RelA increases its activity near 10 times (Shyp et al. 2012), while RelQ is mostly affected by pppGpp (Steinchen et al. 2015). This positive feedback loop is likely important for the quick surge in (p)ppGpp levels in response to stress. Some SAS are also regulated by RNA, but the physiological significance of this is still unclear (Beljantseva et al. 2017a; Hauryliuk and Atkinson 2017).

The physiological disorders of the absence of (p)ppGpp

In thinking of (p)ppGpp signaling as a target for antimicrobials, it is useful to consider what happens to bacteria when this pathway is inactivated. Mutants that do not produce (p)ppGpp (known as (p)ppGpp0) grow similarly to wild-type bacteria in nutrient-rich conditions (Lemos et al. 2007; Abranches et al. 2009; Potrykus et al. 2011; Kriel et al. 2012; Pletzer et al. 2020). However, this apparent normality belies important vulnerabilities. For example, (p)ppGpp0 mutants have markedly altered transcriptomes, even under non-stressed conditions (Gaca et al. 2013; Puszynska and O’Shea 2017; Pletzer et al. 2020), reflecting the important role of “basal” (p)ppGpp in adjusting gene expression to environmental conditions. Among the phenotypic consequences of altered gene expression is the amino acid auxotrophy commonly seen in (p)ppGpp0 mutants (Xiao et al. 1991; Tedin and Norel 2001; Lemos et al. 2007; Kriel et al. 2012), since the expression of several amino acid biosynthetic operons is dependent on (p)ppGpp in both Gram + and Gram − bacteria, albeit via different regulatory mechanisms (Paul et al. 2005; Kriel et al. 2014). Other noteworthy transcriptome alterations are the gratuitous upregulation of alternative carbon catabolism in E. faecalis (Gaca et al. 2013) and the massive overexpression of growth-related genes in cyanobacteria (Puszynska and O’Shea 2017), which indicates that (p)ppGpp0 mutants have lost the ability to properly sense metabolic cues.

On a more global level, (p)ppGpp0 strains tend to exhibit increased overall transcription and accumulate more RNA (both stable and mRNA) per cell than their wild-type counterparts (Hernandez and Bremer 1993; Potrykus et al. 2011; Puszynska and O’Shea 2017), suggesting a compromised coordination of macromolecular synthesis. Loss of coordination of biosynthesis is also evident in the observation that replication initiation becomes uncoupled from growth rate and cell mass in these mutants (Fernández-Coll et al. 2020).

Another important “disease” of (p)ppGpp0 cells is the dysregulation of GTP homeostasis. As described above, (p)ppGpp is a regulator of GTP synthesis, inhibiting both the de novo and salvage pathways that produce GTP. The enzyme targets vary in different bacteria, in E. coli they are Hpt, Gpt, PurF, and Gsk (Wang et al. 2020), whereas in B. subtilis the enzymes controlled are Hpt, Gpt, and Gmk (Kriel et al. 2012), but this effect is widely conserved, highlighting the importance of lowering cellular GTP concentrations as a strategy to respond to stress. As a result of their inability to maintain GTP homeostasis, (p)ppGpp0 cells have a higher GTP to ATP ratio in exponential growth and become susceptible to guanosine toxicity, the surprising loss of viability caused by a massive increase in intracellular GTP when cells are fed with guanosine (Kriel et al. 2012). Furthermore, when faced with nutritional stresses, (p)ppGpp0 cells fail to inhibit GTP synthesis (Kriel et al. 2012; Kästle et al. 2015; Pulschen et al. 2017; Pathania et al. 2021). The inability to lower GTP when under stress is a crucial source of vulnerability of (p)ppGpp0 cells, in particular in Gram + bacteria, where activation of the many genes under CodY control depend on a drop of intracellular GTP. In E. coli, the effect of (p)ppGpp in nucleotide homeostasis extends to ATP as well, and seems to contribute to viability by maintaining the pools of phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate, an essential precursor of nucleotides and amino acids (Wang et al. 2020).

The absence of (p)ppGpp also leads to impaired redox homeostasis. (p)ppGpp0 mutants of S. aureus and V. cholera exhibit basal oxidative stress because of increased TCA cycle and respiratory activity, which together with deffective iron homeostasis result in increased ROS production (Kim et al. 2018; Fritsch et al. 2020). A similar situation is found with E. faecalis, where (p)ppGpp0 mutants exhibit a five-fold increase in H2O2 production resulting from an altered fermentative metabolism (Gaca et al. 2013). Another explanation for the redox perturbation of (p)ppGpp0 mutants is the role played by (p)ppGpp in the expression of detoxifying enzymes such as catalase and SOD. This has been shown for Pseudomonas (Khakimova et al. 2013; Martins et al. 2018), but probably applies to other species as well, as these enzymes are commonly under stationary phase control.

Finally, (p)ppGpp0 mutants also exhibit cellular scale phenotypes. In several bacteria, absence of (p)ppGpp is associated with impaired cell division and filamentation (Xiao et al. 1991; Dasgupta et al. 2019; Jung et al. 2020), whereas in M. smegmatis and B. subtilis (p)ppGpp0 mutants divide normally but have a marked defect in cell separation, forming long chains of cells that stay connected by their septal walls (Dahl et al. 2005) (A.Z.N.F and F.J.G.-F, unpublished observations). Another cellular phenotype commonly found in (p)ppGpp0 mutants is loss of motility (Magnusson et al. 2007; Dalebroux et al. 2010b).

Facing stress without (p)ppGpp

The metabolic and gene expression perturbations of (p)ppGpp0 cells, which are of limited consequence during good times, become much more dangerous when bacteria are exposed to stress. In the case of starvation, regardless if it is attained gradually in the course of a growth curve, or via an abrupt change in the environment (change of medium, entry into host, exposure to antibiotic), strains that do not produce (p)ppGpp (or that still produce basal (p)ppGpp but cannot mount a stringent response) are oblivious to these changes and keep their metabolism and gene expression program in “growth mode,” failing to redirect resources and reprogram physiology to maximize survival under non-optimal conditions.

The general response of wild-type cells to starvation is to reduce macromolecular synthesis and slow down or interrupt growth. This is true irrespective of the source of starvation (amino acids, carbon, fatty acids, nitrogen, phosphate) and illustrates that one of the main goals of the stringent response is to keep macromolecular synthesis tightly coupled, thereby avoiding the damaging effects of running the biosynthesis engine with a limited or unbalanced supply of fuels. Another hallmark of starved cells is reduced cell size (Traxler et al. 2008; Yao et al. 2012; Stott et al. 2015; Pulschen et al. 2017), which is a consequence of cell division continuing after growth is shutdown (Schreiber et al. 1995; Bergmiller et al. 2011). Together with the activation of stress resistance genes, such as ROS detoxifying enzymes, this “safe shutdown” maneuver is key to maintain viability during starvation, and when disabled (as in (p)ppGpp0 mutants) results in the massive death of every bacterial species investigated, from free-living B. subtilis (Kriel et al. 2012, 2014; Pulschen et al. 2017) and C. crescentus (Lesley and Shapiro 2008; Stott et al. 2015), to commensal E. coli (Nyström 1994; Gong et al. 2002) and pathogens M. tuberculosis (Primm et al. 2000), B. burgdorferi (Drecktrah et al. 2015), E. faecalis (Chávez de Paz et al. 2012), S. aureus (Geiger et al. 2010), and Vibrio strains (Ostling et al. 1995), to cite some.

A survey of papers that have investigated how (p)ppGpp-deficient bacteria respond to starvation demonstrates that a common theme is that these mutants attempt to grow even in the absence of nutrients (Fig. 3). This has been documented by measurements of stable RNA and protein synthesis rates, DNA replication status, and also by the observation that (p)ppGpp-deficient cells do not become smaller upon starvation, a sign that their growth rate was never reduced before losing viability (Fig. 3). However, how growth in the absence of proper resources leads to death may vary depending on the type of starvation imposed on the mutants.

Fig. 3.

Physiological disorders faced by cells incapable of producing (p)ppGpp upon starvation. Starvation is color coded depending on the nutrient missing: lipids (green), amino acids (red), carbon (blue). References are as follows: [1] Pulschen et al., 2017; [2] Stott et al., 2015; [3] Yao et al., 2012; [4] Seyfzadeh et al. 1993; [5] Gong et al., 2002; [6] Wille et al., 1975; [7] Nyström 1994; [8] Traxler et al., 2008; [9] Kriel et al., 2012; [10] O’Farrell, 1978; [11] Kriel et al., 2014; [12] Wang et al. 2007; [13] Tehranchi et al. 2010; [14] Sørensen et al., 1994; [15] Geiger et al., 2010; [16] Nyström 1994; [17] Boutte et al. 2012; [18] Lesley & Shapiro, 2008; [19] Ostling et al., 1995; [20] Fredriksson et al., 2007; [21] Pathania et al., 2021; [22] Kästle et al., 2015

Upon amino acid starvation, protein synthesis continues but with reduced fidelity in (p)ppGpp-deficient E. coli (O’Farrell 1978; Sørensen et al. 1994; Nyström 1994). The resulting accumulation of nonfunctional and misfolded proteins is a known source of toxicity, although the mechanism is still debated (Allan Drummond and Wilke 2009; Ling et al. 2012). Another source of damage during amino acid starvation is the dysregulation of purine homeostasis, in particular GTP, whose synthesis is not inhibited in (p)ppGpp-deficient cells (Kriel et al. 2012, 2014; Kästle et al. 2015; Horvatek et al. 2020).

A different, and perhaps more dramatic, picture emerges when we analyze (p)ppGpp-deficient bacteria subject to fatty acid starvation. In (p)ppGpp0 B. subtilis treated with cerulenin, an inhibitor of fatty acid synthase, the continuation of protein and nucleic acid synthesis without a proper supply of fatty acids results in quick loss of membrane integrity (Pulschen et al. 2017). Cells with large rips and tears in their membranes could be observed by fluorescence microscopy. In addition, the totality of cells lost membrane potential, indicating that membrane function was compromised even in cells whose membranes were not grossly ruptured. A similar situation—uncontrolled growth followed by envelope damage and lysis—was recently observed when LPS synthesis was genetically inhibited in (p)ppGpp-deficient E. coli (Roghanian et al. 2019). Such truly self-destructive behavior illustrates the importance of (p)ppGpp to keep macromolecular synthesis tightly coordinated, and the damage that may ensue when this coordination is lost.

(p)ppGpp and antibiotic tolerance and resistance:

Given that most antibiotics function by perturbing macromolecular synthesis (often leading to starvation-like situations), it should come as no surprise that (p)ppGpp plays an important role in the response to these drugs. It has been known for a while that activation of the stringent response either via starvation or genetic induction of (p)ppGpp accumulation leads to marked tolerance against antibiotics, in special those that target actively growing cells, such as beta lactams and quinolones (Hobbs and Boraston 2019). In fact, the tolerance of stationary phase bacteria to antibiotics is in large measure a result of the controlled shutdown of growth and activation of stress defenses, in particular against ROS, orchestrated by (p)ppGpp at this stage (Kim et al. 2018; Martins et al. 2018). Importantly, the identification of mutations that activate (p)ppGpp production in bacterial isolates associated with treatment failure indicates that antibiotic resistance mediated by (p)ppGpp accumulation is more than just a laboratory phenomenon and has clinical relevance (Gao et al. 2010; Honsa et al. 2017).

Perhaps less appreciated is the fact that (p)ppGpp also influences the baseline sensitivity of bacteria to antibiotics. (p)ppGpp-deficient mutants exhibit greater sensitivity than wild-type strains to a variety of antibiotics, with different modes of action (Table 1). Sensitivity originates from the same dysregulations that make these cells vulnerable to starvation, such as uncoordinated and error-prone macromolecular synthesis, altered metabolism, and impaired ROS homeostasis. In addition, the absence of (p)ppGpp may prevent the expression of genes specifically associated with antibiotic tolerance and resistance, such as ABC transporters (Jung et al. 2020), aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes (Koskiniemi et al. 2011), and alternative penicillin-binding proteins (Aedo and Tomasz 2016). The hypersensitivity of (p)ppGpp-deficient mutants typically manifests itself in MIC measurements, but sometimes the MIC stays the same and the sensitivity can only be detected in time kill experiments. The effects of a disabled (p)ppGpp pathway can be quite dramatic, and it is common that a regimen that is only bacteriostatic for wild-type cells becomes bactericidal for (p)ppGpp-deficient cells (Gaca et al. 2013; Geiger et al. 2014; Pulschen et al. 2017).

Table 1.

Increased antibiotic sensitivity in (p)ppGpp-deficient bacteria

| Organism | Antibiotic |

|---|---|

| Acinetobacter baumannii* | Colistin1 |

| Gentamicin1 | |

| Trimethoprim1 | |

| Tetracycline1 | |

| Bacillus subtilis | Cerulenin2 |

| Clostridioides difficile** | Metronidazole3 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | Ampicillin4 |

| Norfloxacin4 | |

| Vancomycin5 | |

| Escherichia coli | Ampicillin6 |

| Cephalexin7 | |

| Cephalosporin C7 | |

| Cephalothin7 | |

| Cephamycin C7 | |

| Cerulenin8 | |

| Mupirocin6 | |

| Ofloxacin9, 10 | |

| Penicillin G7 | |

| Francisella tularensis | Nitrofurantoin11 |

| Streptomycin11 | |

| Tetracycline11 | |

| Helicobacter pylori | Amoxicillin12 |

| Ampicillin12 | |

| Coprofloxacin12 | |

| Clarithromycin12 | |

| Furazolidone12 | |

| Metronidazole12 | |

| Penicillin G12 | |

| Tetracycline12 | |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Isoniazid13 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Colistin10 |

| Gentamicin10 | |

| Meropenem10, 14 | |

| Ofloxacin10, 14, 15 | |

| Pseudomonas syringae | Rifampicin16 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Ampicillin17 |

| Vancomicin17 | |

| Vibrio cholerae | Chloramphenicol18 |

| Erythromycin18 | |

| Tetracycline18 |

*Deletion of relA only, spoT gene still present

**Knockdown of rsh gene

[1] Jung et al., 2020; [2] Pulschen et al., 2017; [3] Pokhrel et al. 2020; [4] Gaca et al., 2013; [5] Abranches et al., 2009; [6] Kudrin et al. 2017; [7] Greenway and England 1999; [8] Vadia et al., 2017; [9] Fung et al., 2010; [10] Nguyen et al., 2011; [11] Ma et al., 2019; [12] Ge et al., 2018; [13] Dutta et al., 2019; [14] Khakimova et al., 2013; [15] Martins et al., 2018; [16] Chatnaparat et al., 2015; [17] Geiger et al., 2014; [18] Kim et al., 2018

The SAS of Gram + bacteria seem to play a specialized role in antibiotic tolerance. Expression of some SAS (usually RelP) is under the control of two-component systems (WalRK in B. subtilis) (Libby et al. 2019) and ECF sigma factors (sigM in B. subtilis) (Eiamphungporn and Helmann 2008) that respond to envelope stress and is strongly activated by cell wall active antibiotics such as vancomycin, ampicillin, bacitracin, and fosfomycin (D’Elia et al. 2009; Geiger et al. 2014). The importance of these enzymes for the response to cell wall damage is also underscored by the fact that inactivation of the SAS genes is sufficient to make E. faecalis more vulnerable to vancomycin (Abranches et al. 2009) and S. aureus to vancomycin and ampicillin (Geiger et al. 2014), even though these mutants still possess the RSH enzyme that responds to nutritional stress and are capable of activating the stringent response.

Bacterial persistence is a phenotypic state in which a rare subpopulation of a sensitive strain becomes temporarily tolerant to multiple antibiotics (Balaban et al. 2019). Persistence is associated with chronic and recurrent bacterial infections (Cohen et al. 2013) and, importantly, may also facilitate the evolution of heritable antibiotic resistance (Levin-Reisman et al. 2017; Bakkeren et al. 2020). Initial work with E. coli led to the notion that persistence was a result of stochastic activation of toxin-antitoxin (TA) gene modules, potentially in a (p)ppGpp-dependent way (Maisonneuve et al. 2013), but this has since been revised (Goormaghtigh et al. 2018). Instead, the current view is that persistence is not strictly linked to TA modules and probably has multiple molecular causes, their common denominator being the ability to generate non-growing, biosynthetically dormant cells (Dewachter et al. 2019; Pontes and Groisman 2020; Kaldalu et al. 2020). Thus, even though it is unlikely that all persistent states are a result of (p)ppGpp accumulation, this pathway is clearly an important contributor to persistence development in several bacteria. The first mutation shown to increase persister frequency in E. coli (the hipA1 allele, of the high persistence A gene) exerts its effect by inhibiting tRNA charging and thus promoting (p)ppGpp accumulation (Korch et al. 2003). In addition, lack of (p)ppGpp has been associated with significant reductions in persister formation in P. aeruginosa (Nguyen et al. 2011) and B. subtilis (Fung et al. 2020). Other important observations implicating (p)ppGpp with persistence are two recent publications which employed single-cell methods to demonstrate that subpopulations of bacteria do indeed stochastically accumulate high levels of (p)ppGpp and to provide convincing evidence that the accumulation of (p)ppGpp results in persistence and antibiotic tolerance (Libby et al. 2019; Fung et al. 2020).

(p)ppGpp and virulence:

Defects in (p)ppGpp signaling drastically hamper the infectivity of every pathogen that was tested (Dalebroux et al. 2010a; Kundra et al. 2020). The attenuation is so strong that (p)ppGpp-deficient strains have been suggested as live vaccine candidates (Na et al. 2006; Sun et al. 2009). The impaired virulence of (p)ppGpp-deficient mutants has many concurrent reasons. First, and perhaps foremost, there are the metabolic dysfunctions, stress sensitivity, and the inability of these mutants to interpret and adjust to different environmental conditions. Successfully, colonizing a host requires navigating through diverse cellular and body compartments where pathogens are exposed to different or scarce nutrients and a variety of insults, such as oxidative defenses, low pH, high temperature, hypoxia, and osmotic stress. This alone would result in a much-reduced fitness for a (p)ppGpp-deficient strain. However, on top of that, there are several instances where (p)ppGpp also plays a role as a signal for virulence gene expression. Among the best-studied examples are the activation of the LEE pathogenicity island of enterohemorragic E. coli (EHEC) (Nakanishi et al. 2006) and of the SPI-1 island of Salmonella enterica (Pizarro-Cerdá and Tedin 2004), and the (p)ppGpp-dependent differentiation of Legionella pneumophila into a motile transmissible form (Hammer and Swanson 1999). Among Gram + bacteria, (p)ppGpp was shown to be necessary for the expression of phenol soluble modulins, an important virulence factor of S. aureus (Geiger et al. 2012).

Another connection between (p)ppGpp and virulence is through quorum sensing, the population density signaling system of bacteria. In P aeruginosa, (p)ppGpp directly or indirectly controls the expression of genes of the AHL and PQS quorum-sensing systems of this pathogen, and this probably explains the virulence gene expression defect of a (p)ppGpp0 mutant (van Delden et al. 2001; Schafhauser et al. 2014). Because of its central role in controlling virulence gene expression, quorum sensing is one of the most popular targets of anti-virulence therapies (Rutherford and Bassler 2012; Defoirdt 2018). However, (p)ppGpp seems to sit atop of quorum sensing in the virulence signaling hierarchy and affects virulence in multiple ways beyond quorum sensing. Thus, inhibitors of (p)ppGpp signaling should be even better as anti-virulence therapy.

Targeting the (p)ppGpp pathway:

Inhibitors of (p)ppGpp synthesis will have the potential to combine multiple desirable effects in a single antimicrobial: they should reduce viability and survival, inhibit virulence, increase antibiotic sensitivity, and/or reduce persistence. Because (p)ppGpp is not essential for survival in the lab, the current view is that (p)ppGpp inhibitors would have to be used as adjuvants with other antibiotics. However, (p)ppGpp-deficient mutants are so attenuated that (p)ppGpp inhibitors may be effective antimicrobials when used alone. Another positive side of drugs targeting the (p)ppGpp pathway is a lower selective pressure for resistance, since these molecules will not kill bacteria directly (Allen et al. 2014). Given all these benefits, there are surprisingly few published inhibitors of this pathway.

The first reported inhibitor of RSH enzymes with in vivo activity was the rationally designed (p)ppGpp analog relacin (Wexselblatt et al. 2012). Relacin is active against Gram + species at submillimolar concentrations but it does not penetrate Gram − bacteria. It has found use as a laboratory tool, but its low potency and poor pharmacology are incompatible with development as a drug. Since then, there have been several attempts to identify better (p)ppGpp analogs (Wexselblatt et al. 2013; Beljantseva et al. 2017b; Syal et al. 2017). The most successful of these arrived at two guanosine analogs (compounds AB and AC) that showed improved potency in vitro (IC50 of 40 uM) and were active against M. smegmatis, inhibiting long-term survival and biofilm formation (Syal et al. 2017).

More recently, two high-throughput screens against RSH enzymes were carried out. The first one employed a whole-cell assay that aimed to identify inhibitors of (p)ppGpp synthesis because these should cause amino acid auxotrophy (Andresen et al. 2016b). Despite the ingenious idea, none of the molecules identified in the screen were true RSH inhibitors. The second screen was an academia-pharma collaboration, which employed a biochemical assay to search for inhibitors of M. tuberculosis RSH in GSK’s collection of 2 million compounds and identified 11 molecules with good potency that were also active against the bacterium and lacked host toxicity (Dutta et al. 2019). One of these, compound X9, was shown to sensitize starved mycobateria to isoniazide, validating RSH inhibition as a strategy to circumvent antibiotic tolerance in non-growing states such as persistence. Subsequently, two other potentially interesting compounds (S3-G1A and S3-G1B) were identified in a virtual screen against E. coli RelA and shown to affect biofilm architecture and sensitivity to ampicillin (Hall et al. 2020). Although these molecules were shown to inhibit RelA in vitro, further characterization of their specificity would be desirable. Other reported inhibitors of the (p)ppGpp pathway include two antimicrobial peptides whose anti-biofilm activity was proposed to stem from their ability to bind to (p)ppGpp and promote its degradation (de la Fuente-Núñez et al. 2014; Pletzer et al. 2018). These observations have since been questioned, and thus it is unclear whether the anti-biofilm activity of these peptides is in any way related to (p)ppGpp (Andresen et al. 2016a, b; Bryson et al. 2020).

The scarcity of good and well-characterized inhibitors of the (p)ppGpp pathway suggests that there is ample room for more efforts in this area. The long RSHs are complex enzymes with two active sites in their catalytic domain and that have evolved to sense many different stimuli via their regulatory domains. Therefore, there should be many different ways to inhibit their (p)ppGpp-synthetic activity, including via molecules that work allosterically by pushing the enzyme into a synthesis off/hydrolysis on conformation. Attention should also be given to the SAS, since these enzymes are important for antibiotic tolerance in Gram + bacteria, including a recently recognized role in the expression of high-level methicillin resistance in MRSA (Matsuo et al. 2019; Bhawini et al. 2019). Relacin does not affect these enzymes (Gaca et al. 2015; Beljantseva et al. 2017b), and it is unclear whether any RSH inhibitors will work against the SAS, despite their similar active sites. Progress towards these goals will benefit from the increasing number of structures of RSH and SAS enzymes and the elucidation of their catalytic mechanisms, valuable information for rational design, and virtual screening efforts (Steinchen et al. 2015, 2018; Manav et al. 2018; Tamman et al. 2020; Patil et al. 2020; Pausch et al. 2020; Civera and Sattin 2021; Roghanian et al. 2021). Together with new and clever protein-based and target-directed whole-cell small molecule screens, we hope that the clinical validation of the (p)ppGpp signaling pathway as a new target for antimicrobials is just a matter of time.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jonathan Dworkin for suggestions and critical reading of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by FAPESP grant 2016/05203–5 and the following fellowships: FAPESP 2014/26528–4 (A.A.P), FAPESP 2014/13411–1 (D.E.S) and CNPq fellowships from the Graduate Program in Biochemistry, IQ-USP (A.Z.N.F and A.F.C.).

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abranches J, Martinez AR, Kajfasz JK, et al. The molecular alarmone (p)ppGpp mediates stress responses, vancomycin tolerance, and virulence in Enterococcus faecalis. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:2248–2256. doi: 10.1128/JB.01726-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aedo S, Tomasz A. Role of the stringent stress response in the antibiotic resistance phenotype of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60:2311–2317. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02697-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan Drummond D, Wilke CO. The evolutionary consequences of erroneous protein synthesis. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:715–724. doi: 10.1038/nrg2662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen RC, Popat R, Diggle SP, Brown SP. Targeting virulence: can we make evolution-proof drugs? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12:300–308. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andresen L, Tenson T, Hauryliuk V. Cationic bactericidal peptide 1018 does not specifically target the stringent response alarmone (p)ppGpp. Sci Rep. 2016;6:36549. doi: 10.1038/srep36549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andresen L, Varik V, Tozawa Y, et al. Auxotrophy-based high throughput screening assay for the identification of Bacillus subtilis stringent response inhibitors. Sci Rep. 2016;6:35824. doi: 10.1038/srep35824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arenz S, Abdelshahid M, Sohmen D, et al. The stringent factor RelA adopts an open conformation on the ribosome to stimulate ppGpp synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:6471–6481. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson GC, Tenson T, Hauryliuk V. The RelA/SpoT homolog (RSH) superfamily: distribution and functional evolution of ppGpp synthetases and hydrolases across the tree of life. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakkeren E, Diard M, Hardt W-D. Evolutionary causes and consequences of bacterial antibiotic persistence. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2020;18:479–490. doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-0378-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaban NQ, Helaine S, Lewis K, et al. Definitions and guidelines for research on antibiotic persistence. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17:441–448. doi: 10.1038/s41579-019-0196-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bange G, Brodersen DE, Liuzzi A, Steinchen W (2021) Two P or not two P: understanding regulation by the bacterial second messengers (p)ppGpp. Annu Rev Microbiol 75:annurev-micro-042621–122343. 10.1146/annurev-micro-042621-122343 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Beljantseva J, Kudrin P, Andresen L, et al. Negative allosteric regulation of Enterococcus faecalis small alarmone synthetase RelQ by single-stranded RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:3726–3731. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1617868114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beljantseva J, Kudrin P, Jimmy S, et al. Molecular mutagenesis of ppGpp: turning a RelA activator into an inhibitor. Sci Rep. 2017;7:41839. doi: 10.1038/srep41839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennison, Irving, Corrigan The impact of the stringent response on TRAFAC GTPases and prokaryotic ribosome assembly. Cells. 2019;8:1313. doi: 10.3390/cells8111313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmiller T, Peña-Miller R, Boehm A, Ackermann M. Single-cell time-lapse analysis of depletion of the universally conserved essential protein YgjD. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:118. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhawini A, Pandey P, Dubey AP, et al. RelQ mediates the expression of β-lactam resistance in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:339. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutte CC, Henry JT, Crosson S. ppGpp and Polyphosphate modulate cell cycle progression in Caulobacter crescentus. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:28–35. doi: 10.1128/JB.05932-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown A, Fernández IS, Gordiyenko Y, Ramakrishnan V. Ribosome-dependent activation of stringent control. Nature. 2016;534:277–280. doi: 10.1038/nature17675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryson D, Hettle AG, Boraston AB, Hobbs JK (2020) Clinical mutations that partially activate the stringent response confer multidrug tolerance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 6410.1128/AAC.02103-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cashel M, Gallant J. Two compounds implicated in the function of the RC gene of Escherichia coli. Nature. 1969;221:838–841. doi: 10.1038/221838a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatnaparat T, Li Z, Korban SS, Zhao Y. The bacterial alarmone (p)ppGpp is required for virulence and controls cell size and survival of Pseudomonas syringae on plants. Environ Microbiol. 2015 doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chávez de Paz LE, Lemos JA, Wickström C, Sedgley CM. Role of (p)ppGpp in biofilm formation by Enterococcus faecalis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:1627–1630. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07036-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Civera M, Sattin S. Homology model of a catalytically competent bifunctional Rel protein. Front Mol Biosci. 2021;8:628596. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2021.628596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen NR, Lobritz MA, Collins JJ. Microbial persistence and the road to drug resistance. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;13:632–642. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan RM, Bellows LE, Wood A, Gründling A. ppGpp negatively impacts ribosome assembly affecting growth and antimicrobial tolerance in Gram-positive bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E1710–E1719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1522179113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl JL, Arora K, Boshoff HI, et al. The relA homolog of Mycobacterium smegmatis affects cell appearance, viability, and gene expression. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:2439–2447. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.7.2439-2447.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalebroux ZD, Svensson SL, Gaynor EC, Swanson MS. ppGpp conjures bacterial virulence. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2010;74:171–199. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00046-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalebroux ZD, Yagi BF, Sahr T, et al. Distinct roles of ppGpp and DksA in Legionella pneumophila differentiation. Mol Microbiol. 2010;76:200–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07094.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta S, Das S, Biswas A, et al (2019) Small alarmones (p)ppGpp regulate virulence associated traits and pathogenesis of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi. Cellular Microbiology 2110.1111/cmi.13034 [DOI] [PubMed]

- de la Fuente-Núñez C, Reffuveille F, Haney EF, et al. Broad-spectrum anti-biofilm peptide that targets a cellular stress response. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004152. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defoirdt T. Quorum-sensing systems as targets for antivirulence therapy. Trends Microbiol. 2018;26:313–328. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2017.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Elia MA, Millar KE, Bhavsar AP, et al. Probing teichoic acid genetics with bioactive molecules reveals new interactions among diverse processes in bacterial cell wall biogenesis. Chem Biol. 2009;16:548–556. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewachter L, Fauvart M, Michiels J. Bacterial heterogeneity and antibiotic survival: understanding and combatting persistence and heteroresistance. Mol Cell. 2019;76:255–267. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez S, Ryu J, Caban K, et al. The alarmones (p)ppGpp directly regulate translation initiation during entry into quiescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117:15565–15572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1920013117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drecktrah D, Lybecker M, Popitsch N, et al. The Borrelia burgdorferi RelA/SpoT homolog and stringent response regulate survival in the tick vector and global gene expression during starvation. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1005160. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta NK, Klinkenberg LG, Vazquez MJ, et al. Inhibiting the stringent response blocks Mycobacterium tuberculosis entry into quiescence and reduces persistence. Sci Adv. 2019 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aav2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiamphungporn W, Helmann JD. The Bacillus subtilis σM regulon and its contribution to cell envelope stress responses: Bacillus subtilis σM regulon. Mol Microbiol. 2008;67:830–848. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06090.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Coll L, Cashel M. Possible roles for basal levels of (p)ppGpp: growth efficiency vs. surviving stress. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:592718. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.592718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Coll L, Maciag-Dorszynska M, Tailor K, et al (2020) The absence of (p)ppGpp renders initiation of Escherichia coli chromosomal DNA synthesis independent of growth rates. mBio 11 10.1128/mBio.03223-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fredriksson A, Ballesteros M, Peterson CN, Persson O, Silhavy TJ, Nyström T (2007) Decline in ribosomal fidelity contributes to the accumulation and stabilization of the master stress response regulator sigmaS upon carbon starvation. Genes Dev 21:862–874. 10.1101/gad.409407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fritsch VN, Loi VV, Busche T, et al. The alarmone (p)ppGpp confers tolerance to oxidative stress during the stationary phase by maintenance of redox and iron homeostasis in Staphylococcus aureus. Free Radical Biol Med. 2020;161:351–364. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.10.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung DK, Barra JT, Schroeder JW, et al (2020) A shared alarmone-GTP switch underlies triggered and spontaneous persistence. Microbiology

- Fung DKC, Chan EWC, Chin ML, Chan RCY. Delineation of a bacterial starvation stress response network which can mediate antibiotic tolerance development. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010 doi: 10.1128/AAC.01218-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaca AO, Kajfasz JK, Miller JH, et al. Basal levels of (p)ppGpp in Enterococcus faecalis: the magic beyond the stringent response. mBio. 2013 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00646-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaca AO, Kudrin P, Colomer-Winter C, et al. From (p)ppGpp to (pp)pGpp: characterization of regulatory effects of pGpp synthesized by the small alarmone synthetase of Enterococcus faecalis. J Bacteriol. 2015;197:2908–2919. doi: 10.1128/JB.00324-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao W, Chua K, Davies JK, et al. Two novel point mutations in clinical Staphylococcus aureus reduce linezolid susceptibility and switch on the stringent response to promote persistent infection. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000944. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Cai Y, Chen Z, et al. Bifunctional enzyme SpoT is involved in biofilm formation of Helicobacter pylori with multidrug resistance by upregulating efflux pump Hp1174 (gluP) Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018 doi: 10.1128/AAC.00957-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger T, Francois P, Liebeke M, et al. The stringent response of Staphylococcus aureus and its impact on survival after phagocytosis through the induction of intracellular PSMs expression. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1003016. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger T, Goerke C, Fritz M, et al. Role of the (p)ppGpp synthase RSH, a RelA/SpoT homolog, in stringent response and virulence of Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun. 2010;78:1873–1883. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01439-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger T, Kästle B, Gratani FL, et al. Two small (p)ppGpp synthases in Staphylococcus aureus mediate tolerance against cell envelope stress conditions. J Bacteriol. 2014 doi: 10.1128/JB.01201-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger T, Wolz C. Intersection of the stringent response and the CodY regulon in low GC Gram-positive bacteria. Int J Med Microbiol. 2014;304:150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong L, Takayama K, Kjelleberg S. Role of spoT-dependent ppGpp accumulation in the survival of light-exposed starved bacteria. Microbiology (reading, England) 2002;148:559–570. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-2-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goormaghtigh F, Fraikin N, Putrinš M, et al (2018) Reassessing the role of type II toxin-antitoxin systems in formation of Escherichia coli type II persister cells. mBio 9 10.1128/mBio.00640-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gourse RL, Chen AY, Gopalkrishnan S, et al. Transcriptional responses to ppGpp and DksA. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2018;72:163–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-090817-062444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenway DLA, England RR. The intrinsic resistance of Escherichia coli to various antimicrobial agents requires ppGpp and σ(s) Lett Appl Microbiol. 1999 doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765X.1999.00642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall DC, Król JE, Cahill JP, et al. The development of a pipeline for the identification and validation of small-molecule RelA inhibitors for use as anti-biofilm drugs. Microorganisms. 2020;8:1310. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8091310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer BK, Swanson MS. Co-ordination of Legionella pneumophila virulence with entry into stationary phase by ppGpp. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:721–731. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauryliuk V, Atkinson GC. Small alarmone synthetases as novel bacterial RNA-binding proteins. RNA Biol. 2017;14:1695–1699. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2017.1367889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez VJ, Bremer H. Characterization of RNA and DNA synthesis in Escherichia coli strains devoid of ppGpp. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:10851–10862. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)82063-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs JK, Boraston AB. (p)ppGpp and the stringent response: an emerging threat to antibiotic therapy. ACS Infect Dis. 2019;5:1505–1517. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.9b00204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg T, Mechold U, Malke H, et al. Conformational antagonism between opposing active sites in a bifunctional RelA/SpoT homolog modulates (p)ppGpp metabolism during the stringent response [corrected] Cell. 2004;117:57–68. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00260-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honsa ES, Cooper VS, Mhaissen MN, et al (2017) RelA mutant Enterococcus faecium with multiantibiotic tolerance arising in an immunocompromised host. mBio 8:e02124–16, /mbio/8/1/e02124–16.atom. 10.1128/mBio.02124-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Horvatek P, Salzer A, Hanna AMF, et al. Inducible expression of (pp)pGpp synthetases in Staphylococcus aureus is associated with activation of stress response genes. PLoS Genet. 2020;16:e1009282. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1009282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imholz NCE, Noga MJ, van den Broek NJF, Bokinsky G. Calibrating the bacterial growth rate speedometer: a re-evaluation of the relationship between basal ppGpp, growth, and RNA synthesis in Escherichia coli. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:574872. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.574872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irving SE, Choudhury NR, Corrigan RM. The stringent response and physiological roles of (pp)pGpp in bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021;19:256–271. doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-00470-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irving SE, Corrigan RM. Triggering the stringent response: signals responsible for activating (p)ppGpp synthesis in bacteria. Microbiology. 2018;164:268–276. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung HW, Kim K, Islam MM, et al. Role of ppGpp-regulated efflux genes in Acinetobacter baumannii. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2020 doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaldalu N, Hauryliuk V, Turnbull KJ, et al (2020) In Vitro Studies of Persister Cells. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 8410.1128/MMBR.00070-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kanjee U, Ogata K, Houry WA. Direct binding targets of the stringent response alarmone (p)ppGpp: protein targets of ppGpp. Mol Microbiol. 2012;85:1029–1043. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kästle B, Geiger T, Gratani FL, et al. rRNA regulation during growth and under stringent conditions in S taphylococcus aureus: rRNA regulation in S. aureus. Environ Microbiol. 2015;17:4394–4405. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khakimova M, Ahlgren HG, Harrison JJ, et al. The stringent response controls catalases in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and is required for hydrogen peroxide and antibiotic tolerance. J Bacteriol. 2013 doi: 10.1128/JB.02061-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HY, Go J, Lee KM, et al. Guanosine tetra- and pentaphosphate increase antibiotic tolerance by reducing reactive oxygen species production in Vibrio cholerae. J Biol Chem. 2018 doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA117.000383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korch SB, Henderson TA, Hill TM. Characterization of the hipA7 allele of Escherichia coli and evidence that high persistence is governed by (p)ppGpp synthesis: persistence and (p)ppGpp synthesis in E. coli. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50:1199–1213. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koskiniemi S, Pränting M, Gullberg E, et al. Activation of cryptic aminoglycoside resistance in Salmonella enterica: activation of cryptic resistance. Mol Microbiol. 2011;80:1464–1478. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriel A, Bittner AN, Kim SH, et al. Direct regulation of GTP homeostasis by (p)ppGpp: a critical component of viability and stress resistance. Mol Cell. 2012;48:231–241. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriel A, Brinsmade SR, Tse JL, et al. GTP dysregulation in Bacillus subtilis cells lacking (p)ppGpp results in phenotypic amino acid auxotrophy and failure to adapt to nutrient downshift and regulate biosynthesis genes. J Bacteriol. 2014;196:189–201. doi: 10.1128/JB.00918-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan S, Chatterji D. Pleiotropic effects of bacterial small alarmone synthetases: underscoring the dual-domain small alarmone synthetases in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:594024. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.594024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudrin P, Varik V, Oliveira SRA, et al. Subinhibitory concentrations of bacteriostatic antibiotics induce relA-dependent and relA-independent tolerance to β-lactams. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017 doi: 10.1128/AAC.02173-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundra S, Colomer-Winter C, Lemos JA. Survival of the fittest: the relationship of (p)ppGpp with bacterial virulence. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:601417. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.601417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemos JA, Lin VK, Nascimento MM, et al. Three gene products govern (p)ppGpp production by Streptococcus mutans. Mol Microbiol. 2007;65:1568–1581. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesley JA, Shapiro L. SpoT regulates DnaA stability and initiation of DNA replication in carbon-starved Caulobacter crescentus. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:6867–6880. doi: 10.1128/JB.00700-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin-Reisman I, Ronin I, Gefen O, et al. Antibiotic tolerance facilitates the evolution of resistance. Science. 2017;355:826–830. doi: 10.1126/science.aaj2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby EA, Reuveni S, Dworkin J. Multisite phosphorylation drives phenotypic variation in (p)ppGpp synthetase-dependent antibiotic tolerance. Nat Commun. 2019;10:5133. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13127-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling J, Cho C, Guo L-T, et al. Protein aggregation caused by aminoglycoside action is prevented by a hydrogen peroxide scavenger. Mol Cell. 2012;48:713–722. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loveland AB, Bah E, Madireddy R, et al. Ribosome•RelA structures reveal the mechanism of stringent response activation. eLife. 2016;5:e17029. doi: 10.7554/eLife.17029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z, King K, Alqahtani M, et al. Stringent response governs the oxidative stress resistance and virulence of Francisella tularensis. PLoS One. 2019 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0224094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson LU, Gummesson B, Joksimović P, et al. Identical, Independent, and opposing roles of ppGpp and DksA in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:5193–5202. doi: 10.1128/JB.00330-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisonneuve E, Castro-Camargo M, Gerdes K. RETRACTED: (p)ppGpp controls bacterial persistence by stochastic induction of toxin-antitoxin activity. Cell. 2013;154:1140–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manav MC, Beljantseva J, Bojer MS, et al. Structural basis for (p)ppGpp synthesis by the Staphylococcus aureus small alarmone synthetase RelP. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:3254–3264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA117.001374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins D, McKay G, Sampathkumar G, et al. Superoxide dismutase activity confers (p)ppGpp-mediated antibiotic tolerance to stationary-phase Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1804525115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo M, Yamamoto N, Hishinuma T, Hiramatsu K (2019) Identification of a novel gene associated with high-level β-lactam resistance in heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus strain Mu3 and methicillin-resistant S. aureus strain N315. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 63 10.1128/AAC.00712-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Milon P, Tischenko E, Tomsic J, et al. The nucleotide-binding site of bacterial translation initiation factor 2 (IF2) as a metabolic sensor. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103:13962–13967. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606384103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittenhuber G. Comparative genomics and evolution of genes encoding bacterial (p)ppGpp synthetases/hydrolases (the Rel, RelA and SpoT proteins) J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2001;3:585–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na HS, Kim HJ, Lee H-C, et al. Immune response induced by Salmonella typhimurium defective in ppGpp synthesis. Vaccine. 2006;24:2027–2034. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi N, Abe H, Ogura Y, et al. ppGpp with DksA controls gene expression in the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) pathogenicity island of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli through activation of two virulence regulatory genes: stringent response system in EHEC pathogenicity. Mol Microbiol. 2006;61:194–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanamiya H, Kasai K, Nozawa A, et al. Identification and functional analysis of novel (p)ppGpp synthetase genes in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 2008;67:291–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JW, Breaker RR. The lost language of the RNA World. Sci Signal. 2017;10:eaam8812. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aam8812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen D, Joshi-Datar A, Lepine F, et al. Active starvation responses mediate antibiotic tolerance in biofilms and nutrient-limited bacteria. Science. 2011 doi: 10.1126/science.1211037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noga MJ, Büke F, van den Broek NJF, et al (2020) Posttranslational control of PlsB Is sufficient to coordinate membrane synthesis with growth in Escherichia coli. mBio 11:e02703–19, /mbio/11/4/mBio.02703–19.atom. 10.1128/mBio.02703-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nyström T. Role of guanosine tetraphosphate in gene expression and the survival of glucose or seryl-tRNA starved cells of Escherichia coli K12. Molec Gen Genet. 1994;245:355–362. doi: 10.1007/BF00290116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyström T. Growth versus maintenance: a trade-off dictated by RNA polymerase availability and sigma factor competition?: transcriptional trade-offs. Mol Microbiol. 2004;54:855–862. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Farrell PH. The suppression of defective translation by ppGpp and its role in the stringent response. Cell. 1978;14:545–557. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90241-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostling J, Flärdh K, Kjelleberg S. Isolation of a carbon starvation regulatory mutant in a marine Vibrio strain. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6978–6982. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.23.6978-6982.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathania A, Anba-Mondoloni J, Gominet M, et al (2021) (p)ppGpp/GTP and malonyl-CoA modulate Staphylococcus aureus adaptation to FASII antibiotics and provide a basis for synergistic bi-therapy. mBio 12 10.1128/mBio.03193-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Patil PR, Vithani N, Singh V, et al. A revised mechanism for (p)ppGpp synthesis by Rel proteins: the critical role of the 2′-OH of GTP. J Biol Chem. 2020;295:12851–12867. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA120.013636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul BJ, Berkmen MB, Gourse RL. DksA potentiates direct activation of amino acid promoters by ppGpp. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102:7823–7828. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501170102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pausch P, Abdelshahid M, Steinchen W, et al. Structural basis for regulation of the opposing (p)ppGpp Synthetase and hydrolase within the stringent response orchestrator Rel. Cell Rep. 2020;32:108157. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizarro-Cerdá J, Tedin K. The bacterial signal molecule, ppGpp, regulates Salmonella virulence gene expression: ppGpp regulates Salmonella virulence gene expression. Mol Microbiol. 2004;52:1827–1844. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pletzer D, Blimkie TM, Wolfmeier H, et al (2020) The stringent stress response controls proteases and global regulators under optimal growth conditions in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. mSystems 5 10.1128/mSystems.00495-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pletzer D, Mansour SC, Hancock REW. Synergy between conventional antibiotics and anti-biofilm peptides in a murine, sub-cutaneous abscess model caused by recalcitrant ESKAPE pathogens. PLoS Pathog. 2018;14:e1007084. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokhrel A, Poudel A, Castro KB, et al. The (p)ppGpp synthetase RSH mediates Stationary-phase onset and antibiotic stress survival in Clostridioides difficile. J Bacteriol. 2020 doi: 10.1128/JB.00377-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontes MH, Groisman EA (2020) A physiological basis for nonheritable antibiotic resistance. mBio 11 10.1128/mBio.00817-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Potrykus K, Murphy H, Philippe N, Cashel M. ppGpp is the major source of growth rate control in E. coli. Environ Microbiol. 2011;13:563–575. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02357.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primm TP, Andersen SJ, Mizrahi V, et al. The stringent response of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is required for long-term survival. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:4889–4898. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.17.4889-4898.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulschen AA, Sastre DE, Machinandiarena F, et al. The stringent response plays a key role in Bacillus subtilis survival of fatty acid starvation. Mol Microbiol. 2017 doi: 10.1111/mmi.13582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puszynska AM, O’Shea EK. ppGpp controls global gene expression in light and in darkness in S. elongatus. Cell Rep. 2017;21:3155–3165. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.11.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roghanian M, Semsey S, Løbner-Olesen A, Jalalvand F. (p)ppGpp-mediated stress response induced by defects in outer membrane biogenesis and ATP production promotes survival in Escherichia coli. Sci Rep. 2019;9:2934. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-39371-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roghanian M, Van Nerom K, Takada H, et al. (p)ppGpp controls stringent factors by exploiting antagonistic allosteric coupling between catalytic domains. Mol Cell. 2021;81:3310–3322.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronneau S, Hallez R. Make and break the alarmone: regulation of (p)ppGpp synthetase/hydrolase enzymes in bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2019;43:389–400. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuz009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford ST, Bassler BL. Bacterial quorum sensing: its role in virulence and possibilities for its control. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2:a012427–a012427. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Vazquez P, Dewey CN, Kitten N, et al. Genome-wide effects on Escherichia coli transcription from ppGpp binding to its two sites on RNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:8310–8319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1819682116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafhauser J, Lepine F, McKay G, et al. The stringent response modulates 4-hydroxy-2-alkylquinoline biosynthesis and quorum-sensing hierarchy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 2014;196:1641–1650. doi: 10.1128/JB.01086-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber G, Ron EZ, Glaser G. ppGpp-mediated regulation of DNA replication and cell division in Escherichia coli. Curr Microbiol. 1995;30:27–32. doi: 10.1007/BF00294520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seyfzadeh M, Keener J, Nomura M. spoT-dependent accumulation of guanosine tetraphosphate in response to fatty acid starvation in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11004–11008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyp V, Tankov S, Ermakov A, et al. Positive allosteric feedback regulation of the stringent response enzyme RelA by its product. EMBO Rep. 2012;13:835–839. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha AK, Løbner-Olesen A, Riber L. Bacterial chromosome replication and DNA repair during the stringent response. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:582113. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.582113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen MA, Jensen KF, Pedersen S. High concentrations of ppGpp decrease the RNA chain growth rate. J Mol Biol. 1994;236:441–454. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spira B, Ospino K. Diversity in E. coli (p)ppGpp levels and its consequences. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:1759. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinchen W, Schuhmacher JS, Altegoer F, et al. Catalytic mechanism and allosteric regulation of an oligomeric (p)ppGpp synthetase by an alarmone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:13348–13353. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1505271112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinchen W, Vogt MS, Altegoer F, et al. Structural and mechanistic divergence of the small (p)ppGpp synthetases RelP and RelQ. Sci Rep. 2018;8:2195. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20634-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinchen W, Zegarra V, Bange G. (p)ppGpp: magic modulators of bacterial physiology and metabolism. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:2072. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.02072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stott KV, Wood SM, Blair JA, et al. (p)ppGpp modulates cell size and the initiation of DNA replication in Caulobacter crescentus in response to a block in lipid biosynthesis. Microbiology (reading, Engl) 2015;161:553–564. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, Roland KL, Branger CG, et al. The role of relA and spoT in Yersinia pestis KIM5+ pathogenicity. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6720. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syal K, Flentie K, Bhardwaj N, et al (2017) Synthetic (p)ppGpp analogue is an inhibitor of stringent response in mycobacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e00443–17, /aac/61/6/e00443–17.atom. 10.1128/AAC.00443-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tamman H, Van Nerom K, Takada H, et al. A nucleotide-switch mechanism mediates opposing catalytic activities of Rel enzymes. Nat Chem Biol. 2020;16:834–840. doi: 10.1038/s41589-020-0520-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedin K, Norel F. Comparison of Δ relA strains of Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium suggests a role for ppGpp in attenuation regulation of branched-chain amino acid biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:6184–6196. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.21.6184-6196.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tehranchi AK, Blankschien MD, Zhang Y, et al. The transcription factor DksA prevents conflicts between DNA replication and transcription machinery. Cell. 2010;141:595–605. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traxler MF, Chang D-E, Conway T. Guanosine 3′,5′-bispyrophosphate coordinates global gene expression during glucose-lactose diauxie in Escherichia coli. PNAS. 2006;103:2374–2379. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510995103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traxler MF, Summers SM, Nguyen HT, Zacharia VM, Hightower GA, Smith JT, Conway T (2008) The global, ppGpp-mediated stringent response to amino acid starvation in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 68:1128–1148. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06229.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Vadia S, Tse JL, Lucena R, et al. Fatty acid availability sets cell envelope capacity and dictates microbial cell size. Curr Biol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.05.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Delden C, Comte R, Bally AM. Stringent response activates quorum sensing and modulates cell density-dependent gene expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:5376–5384. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.18.5376-5384.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Dai P, Ding D, et al. Affinity-based capture and identification of protein effectors of the growth regulator ppGpp. Nat Chem Biol. 2019;15:141–150. doi: 10.1038/s41589-018-0183-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Grant RA, Laub MT. ppGpp coordinates nucleotide and amino-acid synthesis in E. coli during starvation. Mol Cell. 2020;80:29–42.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JD, Sanders GM, Grossman AD. Nutritional control of elongation of DNA replication by (p)ppGpp. Cell. 2007;128:865–875. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wexselblatt E, Kaspy I, Glaser G, et al. Design, synthesis and structure–activity relationship of novel Relacin analogs as inhibitors of Rel proteins. Eur J Med Chem. 2013;70:497–504. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wexselblatt E, Oppenheimer-Shaanan Y, Kaspy I, et al. Relacin, a Novel antibacterial agent targeting the stringent response. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002925. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao H, Kalman M, Ikehara K, et al. Residual guanosine 3′,5′-bispyrophosphate synthetic activity of relA null mutants can be eliminated by spoT null mutations. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:5980–5990. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)67694-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Z, Davis RM, Kishony R, Kahne D, Ruiz N (2012) Regulation of cell size in response to nutrient availability by fatty acid biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109: E2561–2568. 10.1073/pnas.1209742109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhang Y, Zborníková E, Rejman D, Gerdes K. Novel (p)ppGpp Binding and Metabolizing Proteins of Escherichia coli. mBio. 2018;9:e02188–17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02188-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M, Pan Y, Dai X. (p)ppGpp: the magic governor of bacterial growth economy. Curr Genet. 2019;65:1121–1125. doi: 10.1007/s00294-019-00973-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]