Abstract

Purpose

Dental implant surgery was developed to be the most suitable and comfortable instrument for dental and oral rehabilitation in the past decades, but with increasing numbers of inserted implants, complications are becoming more common. Diabetes mellitus as well as prediabetic conditions represent a common and increasing health problem (International Diabetes Federation in IDF Diabetes Atlas, International Diabetes Federation, Brussels, 2019) with extensive harmful effects on the entire organism [(Abiko and Selimovic in Bosnian J Basic Med Sci 10:186–191, 2010), (Khader et al., in J Diabetes Complicat 20:59–68, 2006, 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2005.05.006)]. Hence, this study aimed to give an update on current literature on effects of prediabetes and diabetes mellitus on dental implant success.

Methods

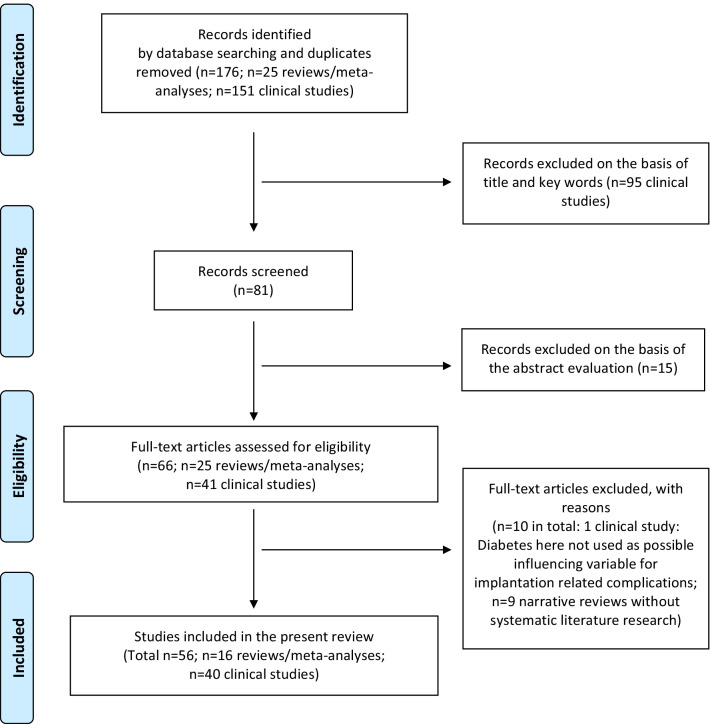

A systematic literature research based on the PRISMA statement was conducted to answer the PICO question “Do diabetic patients with dental implants have a higher complication rate in comparison to healthy controls?”. We included 40 clinical studies and 16 publications of aggregated literature in this systematic review.

Results

We conclude that patients with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus suffer more often from peri-implantitis, especially in the post-implantation time. Moreover, these patients show higher implant loss rates than healthy individuals in long term. Whereas, under controlled conditions success rates are similar. Perioperative anti-infective therapy, such as the supportive administration of antibiotics and chlorhexidine, is the standard nowadays as it seems to improve implant success. Only few studies regarding dental implants in patients with prediabetic conditions are available, indicating a possible negative effect on developing peri-implant diseases but no influence on implant survival.

Conclusion

Dental implant procedures represent a safe way of oral rehabilitation in patients with prediabetes or diabetes mellitus, as long as appropriate precautions can be adhered to. Accordingly, under controlled conditions there is still no contraindication for dental implant surgery in patients with diabetes mellitus or prediabetic conditions.

Keywords: Dental implants, Implant survival, Diabetes mellitus, Prediabetes, Glycemic control, Peri-implantitis, Systemic inflammation, Systemic disease, Risk factor

Background

Nowadays, oral rehabilitation is increasingly achieved through the insertion of dental implants. This takes into account the patient’s and practitioner’s growing desire for aesthetically and chewing-functionally demanding as well as minimally invasive solutions with a high durability. Nevertheless, with increasing numbers of inserted implants, complications are becoming more common. A sufficient osseointegration of the previously placed implants is inevitable for early implant survival. During the osseointegration, however, bone remodeling plays an increasingly crucial role for implant success.

Diagnostic criteria for diabetes mellitus are a fasting plasma glucose in venous plasma with a concentration of ≥ 126 mg/dL, a HbA1c ≥ 6.5%, a 2-h postload plasma glucose measurement of ≥ 200 mg/dL or a random plasma glucose ≥ 200 mg/dL in the presence of symptoms of hyperglycaemia, such as polydipsie or polyurie [1]. Prediabetic conditions are defined as an intermediate hyperglycaemia, that do no attain diabetes thresholds [2]. However, both are very common metabolic disorders, that cause hyperglycemia leading to micro- and macroangiopathies [3]. They are known to be associated with periodontitis [4], delayed wound healing [5] and an impairments of bone metabolism [6].

Diabetes mellitus as well as prediabetic conditions represent a common and increasing health problem with extensive harmful effects on the entire organism. Although diabetes mellitus has been regarded as a relative risk factor for dental rehabilitation with implants, dental implant surgery was developed to be the most suitable and comfortable instrument for dental and oral rehabilitation in the past decades.

Hence, this systematic review aimed to give an update on current literature on effects of pre-diabetes and diabetes mellitus on dental implant success, especially on postoperative complications, peri-implantitis and implant failure rates.

Materials and methods

The substructure of the systematic review is based on the PRISMA 2020 statement/checklist (Table 1) [7]. The focused question was built according to the PICO (population, intervention, comparison, outcome) scheme. It answers the questions “Who are the patients?—diabetic patients” for “P” or population, “What are they exposed to?—dental implants” for “I” or intervention, “What do we compare them to?—healthy controls” for “C” or comparison and for “O” or outcome “What is the outcome?—the complication rate”. Accordingly, the focused question is: “Do diabetic patients with dental implants have a higher complication rate in comparison to healthy controls?”. A registration has not been performed and no review protocol has been prepared.

Table 1.

PRISMA checklist

| Section and topic | Item # | Checklist item | Location where item is reported |

|---|---|---|---|

| Title | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review | Headline |

| Abstract | |||

| Abstract | 2 | See the PRISMA 2020 for Abstracts checklist | – |

| Introduction | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of existing knowledge | Last sentence of introduction |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the objective(s) or question(s) the review addresses | Last sentence of introduction |

| Methods | |||

| Eligibility criteria | 5 | Specify the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review and how studies were grouped for the syntheses | M&M, Study inclusion and exclusion criteria |

| Information sources | 6 | Specify all databases, registers, websites, organisations, reference lists and other sources searched or consulted to identify studies. Specify the date when each source was last searched or consulted | M&M, search strategies |

| Search strategy | 7 | Present the full search strategies for all databases, registers and websites, including any filters and limits used | M&M, search strategies |

| Selection process | 8 | Specify the methods used to decide whether a study met the inclusion criteria of the review, including how many reviewers screened each record and each report retrieved, whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process | M&M, search strategies, first sentence |

| Data collection process | 9 | Specify the methods used to collect data from reports, including how many reviewers collected data from each report, whether they worked independently, any processes for obtaining or confirming data from study investigators, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process | M&M, search strategies, first sentence |

| Data items | 10a | List and define all outcomes for which data were sought. Specify whether all results that were compatible with each outcome domain in each study were sought (e.g., for all measures, time points, analyses), and if not, the methods used to decide which results to collect | M&M, search strategies, second sentence |

| 10b | List and define all other variables for which data were sought (e.g., participant and intervention characteristics, funding sources). Describe any assumptions made about any missing or unclear information | M&M, search strategies, second sentence | |

| Study risk of bias assessment | 11 | Specify the methods used to assess risk of bias in the included studies, including details of the tool(s) used, how many reviewers assessed each study and whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process | M&M, Quality and risk of bias assessment of selected studies; Tables 2/3 |

| Effect measures | 12 | Specify for each outcome the effect measure(s) (e.g., risk ratio, mean difference) used in the synthesis or presentation of results | No effect measures were used due to heterogenous study designs |

| Synthesis methods | 13a | Describe the processes used to decide which studies were eligible for each synthesis (e.g., tabulating the study intervention characteristics and comparing against the planned groups for each synthesis (item #5)) | M&M, study selection, Sentence 6 |

| 13b | Describe any methods required to prepare the data for presentation or synthesis, such as handling of missing summary statistics, or data conversions | M&M, Quality and risk of bias assessment of selected studies | |

| 13c | Describe any methods used to tabulate or visually display results of individual studies and syntheses | M&M, Quality and risk of bias assessment of selected studies, last paragraph | |

| 13d | Describe any methods used to synthesize results and provide a rationale for the choice(s). If meta-analysis was performed, describe the model(s), method(s) to identify the presence and extent of statistical heterogeneity, and software package(s) used | M&M, Quality and risk of bias assessment of selected studies, last paragraph | |

| 13e | Describe any methods used to explore possible causes of heterogeneity among study results (e.g., subgroup analysis, meta-regression) | M&M, Quality and risk of bias assessment of selected studies, last paragraph | |

| 13f | Describe any sensitivity analyses conducted to assess robustness of the synthesized results | No sensitivity analysis has been performed | |

| Reporting bias assessment | 14 | Describe any methods used to assess risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis (arising from reporting biases) | M&M, Quality and risk of bias assessment of selected studies, Risk of bias tools |

| Certainty assessment | 15 | Describe any methods used to assess certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for an outcome | M&M, Quality and risk of bias assessment of selected studies, Clinical studies, penultimate paragraph; Table 3 |

| Results | |||

| Study selection | 16a | Describe the results of the search and selection process, from the number of records identified in the search to the number of studies included in the review, ideally using a flow diagram | Figure 1 |

| 16b | Cite studies that might appear to meet the inclusion criteria, but which were excluded, and explain why they were excluded | Figure 1, Results, Study selection, 3rd section | |

| Study characteristics | 17 | Cite each included study and present its characteristics | Table 6 |

| Risk of bias in studies | 18 | Present assessments of risk of bias for each included study | Tables 2/3/5 |

| Results of individual studies | 19 | For all outcomes, present, for each study: (a) summary statistics for each group (where appropriate) and (b) an effect estimate and its precision (e.g., confidence/credible interval), ideally using structured tables or plots | Table 6 |

| Results of syntheses | 20a | For each synthesis, briefly summarise the characteristics and risk of bias among contributing studies | Tables 2/3/5 |

| 20b | Present results of all statistical syntheses conducted. If meta-analysis was done, present for each the summary estimate and its precision (e.g., confidence/credible interval) and measures of statistical heterogeneity. If comparing groups, describe the direction of the effect | No statistical analysis has been performed | |

| 20c | Present results of all investigations of possible causes of heterogeneity among study results | Tables 3/5 | |

| 20d | Present results of all sensitivity analyses conducted to assess the robustness of the synthesized results | No sensitivity analysis has been performed | |

| Reporting biases | 21 | Present assessments of risk of bias due to missing results (arising from reporting biases) for each synthesis assessed | M&M, Quality and risk of bias assessment of selected studies, Clinical studies |

| Certainty of evidence | 22 | Present assessments of certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for each outcome assessed | Table 3 |

| Discussion | |||

| Discussion | 23a | Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence | Conclusion section |

| 23b | Discuss any limitations of the evidence included in the review | First part of the conclusion | |

| 23c | Discuss any limitations of the review processes used | First part of the conclusion | |

| 23d | Discuss implications of the results for practice, policy, and future research | Conclusion, last part | |

| Other information | |||

| Registration and protocol | 24a | Provide registration information for the review, including register name and registration number, or state that the review was not registered | M&M, first part |

| 24b | Indicate where the review protocol can be accessed, or state that a protocol was not prepared | M&M, first part | |

| 24c | Describe and explain any amendments to information provided at registration or in the protocol | – | |

| Support | 25 | Describe sources of financial or non-financial support for the review, and the role of the funders or sponsors in the review | No fundings/Funding section |

| Competing interests | 26 | Declare any competing interests of review authors | No conflicts of interest/Competing interests section |

| Availability of data, code and other materials | 27 | Report which of the following are publicly available and where they can be found: template data collection forms; data extracted from included studies; data used for all analyses; analytic code; any other materials used in the review | M&M, search strategies |

From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71; For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/

Search strategies

The systematic literature search and data extraction were performed by two independent scientists (JWa and HN). The following databases were incorporated in the systematic search for relevant literature: PubMed, AWMF Online and Cochrane Library. The following search terms were used: dental implant AND diabetes, transgingival implant AND diabetes, maxillary augmentation AND diabetes, mandibular augmentation AND diabetes, periimplantitis AND diabetes, Zahnimplantate AND Diabetes, Kieferkammaufbau AND Diabetes, dental implant AND prediabetes, transgingival implant AND prediabetes, maxillary augmentation AND prediabetes, mandibular augmentation AND prediabetes, periimplantitis AND prediabetes, Zahnimplantate AND Prädiabetes, Kieferkammaufbau AND Prädiabetes. Electronic search was complemented by an iterative hand-search in the reference lists of the already identified articles. The search for aggregated literature was carried out analogously to the search for the clinical literature described above. In addition to the search criteria, the filters meta-analysis, review and systematic review were used and the search was carried out using the above search criteria with the addition meta-analysis or AND meta-analysis or AND Review or AND Systematic Review. Electronic search was complemented by an iterative hand-search in the reference lists of the already identified articles. The starting point of the search was May 7th 2015, taking the time period of our prior literature research and publication into consideration [8]. The end point of the search was April 23rd 2021. Publications before and after these dates have not been considered. A total of 151 of clinical literature studies and 25 studies of aggregated literature were identified after removing duplicates. A total of 25 duplicates were excluded at the title level (Fig. 1). Endnote X9 was used for the electronic management of the literature.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of identified, excluded and included literature

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies at abstract level were included according to the following criteria:

English or German language.

Retrospective and prospective clinical interventional and observation studies, cross-sectional studies, cohort studies, case series.

During the abstract review, hits were excluded according to the following criteria:

In vitro studies.

Animal studies.

Case reports with fewer than 10 patients.

During the assessment the full text of the aggregated literature was excluded according to the following criteria:

Diabetes mellitus/prediabetes not an influencing factor for implant-related parameters.

During the assessment the full text of the aggregated literature was excluded according to the following criteria:

Narrative reviews.

Reviews without systematic literature research.

Quality and risk of bias assessment of selected studies

Clinical studies

The assessment of the internal validity of the primary literature was carried out in the only randomized controlled trial (RCT) presented here, using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool I. Here, the assessment was based on six higher level types of bias (a total of eight sub-items).

Selection bias: has the randomization been carried out adequately? Has the allocation been made in a blinded manner (allocation concealment)?

Performance bias: has the patient and staff been blinded?

Detection bias: was the evaluation blinding?

Attrition bias: has the adequate handling of missing result data been adequately described?

Reporting bias: were planned endpoints really reported?

Other bias: is there no other source of bias?

The selection bias, reporting bias and other bias were assessed for the entire study. The performance bias, detection bias and attrition bias were determined based on endpoints. The only RCT included showed an overall low risk of bias, as six out of eight sub-items could be answered with yes.

The assessment of the internal validity of the 19 cohort studies was based on the New Castle–Ottawa Scale (NOS). Three overarching areas were addressed with a total of nine questions:

- (1) Selection: were the selected cases adequately described (patient characteristics including risk factors, did the consecutive inclusion take place?

- Are the cases representative of the average population?

- Can you describe the collective in an understandable way?

- Is the intervention (everything that has an impact on the outcome) adequately described?

- Has the intervention (everything that has an influence on the outcome) been adequately surveyed?

(2) Comparability: are controls and cases comparable? Are influencing factors checked? Are the results adjusted?

- (3) Outcome.

- Is the outcome adequately described?

- Is the outcome adequately recorded?

- Has the follow-up been chosen long enough?

- Is the number of patients (in follow-up) high enough?

For the assessment of the risk of bias in the cohort studies, a maximum of nine stars are awarded if the questions are answered positively. A maximum of four stars can be achieved for the area of selection bias, a maximum of two stars for comparability and a maximum of three stars for outcome.

The internal validity of the present 18 case series was based on Moga et al. 2012 [9].

The following four questions were addressed and answered with yes, partially, unclear or no:

Were the cases adequately described?

Has the intervention been adequately described and has the relevant data been adequately collected?

Have the outcomes been described adequately and was the relevant data collected adequately?

Has the follow-up period been chosen long enough?

A maximum of four points could be achieved in this way. The final assessment of the risk of bias was then carried out as shown in the following table (Table 2).

Table 2.

Risk of bias assessment for clinical studies

| Risk of bias assessment | Cochrane risk of bias tool I | New Castle–Ottawa Scale | Based on Moga et al. (2012) | Number of studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High risk of bias | < 3 | < 4 | < 2 | 4 |

| Moderate risk of bias | 3–5 | 4–6 | 2–3 | 9 |

| Low risk of bias | 6–8 | 7–9 | 4 | 26 |

The assessment of the risk of bias was then included in the assessment of the evidence (“Body of Evidence”) according to GRADE (“Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation”). In addition, the indirectness (missing mapping of the PICO elements), the heterogeneity of the results and inconsistencies, a lack of precision as well as the suspicion or evidence of publication bias were also included in the evaluation of the quality according to GRADE. A downgrading of one level (“serious”) or two levels (“very serious”) per aspect is possible. With a devaluation of two levels, the maximum achievable evidence is moderate. Cohort studies were upgraded with a low risk of bias and positive evaluation of all other criteria included in GRADE. High quality (++++) rating was achieved by the RCT of Yadav et al. 2018, five studies achieved a moderate quality (+++) as they were upgraded cohort studies, low quality (++) was assumed for 13 cohort studies. In total 20 case studies as well as downgraded cohort studies only a achieved a very low (+) GRADE quality rate (Table 3).

Table 3.

GRADE quality rating for clinical studies

| Study (author/year) | (a) Risk of bias | (b) Indirectness | (c) Heterogenity | (d) Lack of precision | (e) Publication bias | GRADE quality rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eskow et al. (2017) [10] | Low | No | No | No data given | No | + |

| Ormianer et al. (2018) [11] | Moderate | No | No | No | No | + |

| Castellanos-Cosano et al. (2019) [12] | Low | No | No | No data given | No | ++ |

| Alrabiah et al. (2019) [13] | Low | No | No | No data given | No | ++ |

| Sghaireen et al. (2020) [14] | Low | No | No | No | No | +++ |

| Papantonopoulos et al. (2017) [15] | Low | No | No | No data given | No | ++ |

| Atarchi et al. (2020) [16] | Moderate | No | No | No | No | + |

| Alasqah et al. (2018) [17] | Low | No | No | No data given | No | ++ |

| Singh et al. (2020) [18] | High | No | No | No data given | No | + |

| Al Zahrani et al. (2019) [19] | Low | No | No | No data given | No | ++ |

| Erdogan et al. (2015) [20] | Low | No | No | No data given | No | ++ |

| Oztel et al. (2017) [21] | Moderate | No | Yes | No | Possible | + |

| Gomez-Moreno et al. (2015) [22] | Low | No | Nein | No data given | No | ++ |

| Dogan et al. (2015) [23] | Low | No | Nein | No data given | No | ++ |

| Okamoto et al. (2018) [24] | Low | No | No | No | No | +++ |

| Al Amri et al. (2015) [25] | Low | No | No | No | No | +++ |

| de Araujo Nobre et al. (2016) | Low | No | No | No | No | + |

| Al Amri et al. (2017) [26] | Low | No | No | No data given | No | ++ |

| Al Amri et al. (2017) [27] | Low | No | No | No data given | No | ++ |

| Soh et al. (2020) [28] | Moderate | No | No | No data given | No | + |

| Mohanty et al. (2018) [29] | High | No | No | No data given | No | + |

| Aguilar-Salvatierra et al. (2016) [30] | Low | No | No | No data given | No | ++ |

| Rekawek et al. (2021) [31] | Low | No | No | No | No | +++ |

| Jagadeesh et al. (2020) [32] | High | No | No | No data given | Possible | + |

| Kandasamy et al. (2018) [33] | Moderate | No | No | No data given | Possible | + |

| Pedro et al. (2017) [34] | Moderate | No | No | No data given | No | + |

| Yadav et al. (2018) [35] | Low | No | No | No data given | No | ++++ |

| Khan et al. (2016) [36] | High | No | No | No data given | No | + |

| French et al. (2021) [37] | Moderate | No | No | No | No | + |

| Alberti et al. (2020) [38] | Low | No | No | No | No | +++ |

| Krebs et al. (2019) [39] | Low | No | No | No | No | + |

| Dalago et al. (2017) [40] | low | no | no | No | No | + |

| De Araújo Nobre et al. (2017) [41] | Moderate | No | No | No | No | + |

| Mayta-Tovalino et al. (2019) [42] | Moderate | No | No | No | No | + |

| Kissa et al. (2020) [43] | Low | No | No | No | No | + |

| Krennmair et al. (2018) [44] | Low | No | No | No | No | + |

| Al-Sowygh et al. (2018) [45] | Low | No | No | No data given | No | ++ |

| Corbella et al. (2020) [46] | Low | No | No | No | No | + |

| Al Amri et al. (2017) [47] | Low | No | No | No data given | No | ++ |

| Weinstein et al. (2020) [48] | Low | No | No | No | No | + |

No studies were excluded due to a lack of quality, but all data were included in the evaluation.

Moreover, the external validity of the available clinical literature was determined, as the question, whether the results can be transferred to the German supply situation, was answered. Attention was paid to the collective of patients, the treatment plan used and the setting (Table 4).

Table 4.

External validity for clinical studies

| Study (author/year) | Results transferable to the German supply situation? | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Treatment | Setting | |

| Eskow et al. (2017) [10] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ormianer et al. (2018) [11] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Castellanos-Cosano et al. (2019) [12] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Alrabiah et al. (2019) [13] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Sghaireen et al. (2020) [14] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Papantonopoulos et al. (2017) [15] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Atarchi et al. (2020) [16] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Alasqah et al. (2018) [17] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Singh et al. (2020) [18] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Al Zahrani et al. (2019) [19] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Erdogan et al. (2015) [20] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Oztel et al. (2017) [21] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Gomez-Moreno et al. (2015) [22] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Dogan et al. (2015) [23] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Okamoto et al. (2018) [24] | Uncertain | Yes | Uncertain, obviously university for women |

| Al Amri et al. (2015) [25] | Male subjects only | Yes | Yes |

| de Araujo Nobre et al. (2016) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Al Amri et al. (2017) [26] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Al Amri et al. (2017) [27] | Male subjects only | Yes | Yes |

| Soh et al. (2020) [28] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Mohanty et al. (2018) [29] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Aguilar-Salvatierra et al. (2016) [30] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Rekawek et al. (2021) [31] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Jagadeesh et al. (2020) [32] | Yes | n.d. | Yes |

| Kandasamy et al. (2018) [33] | Yes | n.d. | Yes |

| Pedro et al. (2017) [34] | Yes | n.d. | n.d. |

| Yadav et al. (2018) [35] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Khan et al. (2016) [36] | Yes | n.d. | n.d. |

| French et al. (2021) [37] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Alberti et al. (2020) [38] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Krebs et al. (2019) [39] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Dalago et al. (2017) [40] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| De Araújo Nobre et al. (2017) [41] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Mayta-Tovalino et al. (2019) [42] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Kissa et al. (2020) [43] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Krennmair et al. (2018) [44] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Al-Sowygh et al. (2018) [45] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Corbella et al. (2020) [46] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Al Amri et al. (2017) [47] | Male subjects only | Yes | Yes |

| Weinstein et al. (2020) [48] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

n.d. no data provided

Aggregated literature

The assessment of the aggregated literature was based on the AMSTAR (Assessment of Multiple SysTemAtic Reviews)-2 criteria, including eleven questions that can be answered with yes, no, uncertain or not applicable. If a question is answered with yes, one point will be awarded. A maximum of eleven points could be achieved per study. The following 11 questions were used to assess the quality:

A priori planning/definition: Do you refer to a protocol or previously defined research goals?

Was the study selection and data extraction carried out by two independent persons?

Has the comprehensive and systematic literature search been carried out?

Have unpublished data/grey literature been considered?

Are the references for included and excluded studies given in the review article? Are the references listed and accessible electronically?

Were the study characteristics (patient characteristics, intervention (s) and endpoints) of the included studies given in tabular form or in detail in text form?

Was the risk of bias of the included primary studies assessed using established methods?

Was the risk of bias of the included studies considered for the result interpretation of the review article? (No yes, if previous question was not answered with yes)

Were the study results statistically adequately evaluated? Have pooled results been determined? Have heterogeneity tests been carried out?

Have publication bias/dissemination bias been addressed? Have at least ten primary studies been included?

Have any conflicts of interest been addressed?

The quality was then assessed using a scale based on the following points: 0–3 points: low quality; 4–7 points: moderate quality; 8–11 points: high quality [49]. Based on this rating, the quality of 15 studies was rated as high. The evaluation of two studies as moderate and no studies with a low quality. No studies had to be excluded due to a low quality (Table 5).

Table 5.

AMSTAR-quality rating for aggregated literature due to AMSTAR-2 criteria

| Study (first author/year) | (1) A priori planning/definition? | (2) Was the study selection and data extraction carried out by two independent persons? | (3) Systematic literature search | (4) Has grey literature been taken into account? | (5) References given and electronicall available? | (6) Study characteristics given? | (7) Risk of bias assessment? | (8) Was the risk of bias taken into account for interpretation in the review article? | (9) Adequate statistics? Pooled results? Heterogenity tests? | (10) Have publication bias/dissemination bias been addressed? Have at least ten primary studies been included? | (11) Have conflicts of interest been addressed? | AMSTAR-Rating | AMSTAR-Quality (8–11 = high, 4–7 = medium; 0–3 = low) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naujokat et al. (2016) [8] | y | y | y | n | y | y | y | y | n | y | y | 9 | High |

| Jiang et al. (2021) [50] | y | u | y | n | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | 9 | High |

| Moraschini et al. (2016) [51] | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | 11 | High |

| Schimmel et al. (2018) [52] | y | y | y | u | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | 10 | High |

| Singh et al. (2019) [53] | y | u | y | n | y | y | n | n | n | y | y | 6 | Medium |

| Ting et al. (2018) [54] | y | y | y | u | y | y | y | y | u | y | y | 9 | High |

| Souto-Maior et al. (2019) [55] | y | y | y | u | y | y | y | y | n | n | y | 8 | High |

| De Oliveira-Neto et al. (2019) [56] | y | u | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | n | y | 9 | High |

| Shi et al. (2016) [57] | y | y | y | n | y | y | y | u | y | n | y | 8 | High |

| Shang et al. (2021) [58] | y | y | y | n | y | y | y | y | y | n | y | 9 | High |

| Lagunov et al. (2019) [59] | y | y | y | n | y | y | y | y | y | n | n | 8 | High |

| Dreyer et al. (2018) [60] | y | y | y | n | y | n | y | y | y | n** | y | 8 | High |

| Monje et al. (2017) [61] | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | u | y | y | y | 10 | High |

| Turri et al. (2016) [62] | y | u* | y | n | y | y | y | u | u | n | y | 6 | Medium |

| Meza Mauricio et al. (2019) [63] | y | y | y | n | y | y | y | n | n | y | y | 8 | High |

| Guobis et al. (2016) [64] | y | y | y | n | y | y | y | y | n | n** | n | 7 | High |

y yes, n no, u unclear

*Data extraction: yes; study selection: unclear; **less than ten studies regarded diabetes mellitus

All risk of bias assessments were performed by two independent researches (JWa, HN). All results were displayed in a table and the results were colored differently, dependent on the positive, negative or any other non-significant influence of diabetes on the outcomes (survival, periimplantitis, osseointegration, augmentation). In addition, the studies in the table were colored differently if an influence of any supportive therapy, the glycemic control or the duration of diabetes mellitus has been reported.

Results

Study selection

One guideline from 2016 to the topic of dental implants and diabetes mellitus, in which the authors of this study (JWi, HN) play a key role, was identified.

A total of 177 potentially relevant titles and abstracts were found by the electronic search and additional evaluation of reference lists. During the first screening, 95 publications were excluded based on the title and keywords. In addition, 15 titles of clinical studies were excluded based on abstract evaluation. In total, 66 full-text articles were thoroughly evaluated, containing of clinical studies (n = 41) and reviews (n = 25). Ten titles had to be excluded at this stage, because they did not fulfil the inclusion criteria of the present systematic review.

56 articles (40 clinical studies and 16 reviews and meta-analyses) went into qualitative assessment by tabulating the study characteristics, implant related parameters and diabetes related parameters. Ten studies had to be excluded although they matched the inclusion criteria. One study had to be excluded, because diabetes was not used as possible variable for implantation related complications [65]. Nine studies of aggregated literature had to be excluded, because they were narrative without systematic literature research ([66–74] Fig. 1). No meta-analysis was performed, due to limited number of studies, heterogenic study design and incompletely reported data, such as type of diabetes therapy, quality of glycemic control and duration of disease. The quantitative data synthesis could not be performed in the way necessary for meta-analysis.

Regarding the clinical studies, the majority (n = 20) of the 40 studies were retrospective, eight had a cross-sectional study design. Eleven were prospective and one study was a randomized controlled trial. The main characteristics of the included studies are given in Table 6.

Table 6.

List of the included clinical studies and its main characteristics

| Study (author/year) | Study type | No. of patients | Age (mean) | Time of examination | Duration of study [months] | Number of implants | Survival rate [%] | Diabetestype | Control | Diabetes therapy | Glycemic control [HbA1c %] | Duration of diabetes mellitus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eskow et al. (2017) [10] | Retrospective | 24 | 59.7 ± 9.6 | k.A. | 34 | 59 | 98.6 (1 year); 96.6 (2 years) | 2 | No controlgroup | n.d. | “Poorly controlled”; 9.55 ± 1.0% | 14.2 ± 7.7 years |

| Ormianer et al. (2018) [11] | Retrospective | 169 | 55.9 ± 10.474 | 1995–2015 | 104 | 1112 | 94 | 2 | n.d. | n.d. | “Moderately controlled” < 8%; “well-controlled” up to 7% | At least 2 years |

| Castellanos-Cosano et al. (2019) [12] | Retrospective | 346 | 56.12 ± 12.15 | 2014–2017 | 48 | 44,415 | n.d. | n.d. | No controlgroup | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Alrabiah et al. (2019) [13] | Cross-sectional | 79 | Prediabetic group: 54.3 ± 3.6; nondiabetic group: 51.2 ± 2.4 | n.d. | 60 | 80 | 100 | Prediabetes | Nondiabetic group | n.d. | Prediabetic group: 6.1[5.9–6.3]%; nondiabetic group: 4.1[4–4.8]% | Prediabetes diagnosis 5.4 ± 0.2 years |

| Sghaireen et al. (2020) [14] | Retrospective | 257 | Diabetic group: 62.41 ± 13.62y; nondiabetic group: 59.24 ± 29.36 y | 2013–2016 | 36 | 742 | Diabetic group: 90.18; nondiabetic group: 90.95 | n.d. | HbA1c < 6.5% | n.d. | “Well controlled” 6.5–8%; no further information + L8 | n.d. |

| Papantonopoulos et al. (2017) [15] | Cross-sectional | 72 | 61.9 ± 11.1 | 2014–2015 | n.d. | 237 | n.d. | n.d. | Nondiabetic Clusters | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Atarchi et al. (2020) [16] | Cross-sectional | 1343 | 61.66 ± 12.77 | 2002–2017 | n.d. | 2323 | n.d. | n.d. | Nondiabetic group | n.d. | < 8%;“controlled diabetics” | n.d. |

| Alasqah et al. (2018) [17] | Cross-sectional | 86 | Diabetic group: 57.6 ± 5.5; nondiabetic group: 61.6 ± 4.3 y | n.d. | 72 | 172 | n.d. | 2 | Nondiabetic group; HbA1c 5.3 ± 0.3% | n.d. | “Well controlled” diabetes group: 4.8 ± 0.2%; nondiabetic group: 5.3 ± 0.3% | 10.1 ± 3.5 years |

| Singh et al. (2020) [18] | Retrospective | 826 | n.d. | n.d. | 120 | 1420 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Al Zahrani et al. (2019) [19] | Prospective | 67 | Well controlled diabetics: 54.6 ± 9.9; poorly controlled diabetics: 53.8 ± 7.9 | 2009–2011 | 84 | 124 | 99 (7 years) | 2 | Poorlycontrolled diabetics | “Well controlled” diabetics: controlled by diet and anti-diabetic drugs (w or w/o insulin); “poorly controlled” diabetics: no control by diet or drugs | “Well controlled” diabetics: ≤ 6.0% “poorly controlled” diabetics: > 8.0% | Well controlled: 6.6 years; poorly controlled: 11.8 years |

| Erdogan et al. (2015) [20] | Prospective | 24 | Diabetic group: 52.5 ± 7.3; nondiabetic group: 49.5 ± 9.3 | k.A. | 12 (and more) | 43 | 100 | 2 | n.d. | All diabetic patients on active treatment (oral therapy, insuline, combination) | 6.7 ± 0.3% | 8.2 ± 3.5 years |

| Oztel et al. (2017) [21] | Retrospective | 177 | 60.2 ± 15.1 | 2011–2013 | 36 | 302 | 95 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Gomez-Moreno et al. (2015) [22] | Prospective | 67 | Groups: HbA1c ≤ 6%: 60 ± 7.2; HbA1c = 6.1–8%: 59 ± 8.1; HbA1c = 8.1–10%: 62 ± 6.8; HbA1c ≥ 10.1%:64 ± 5.6 | n.d. | 36 | 67 | n.d. | 2 | Four groups: HbA1c ≤ 6%; HbA1c = 6.1–8%; HbA1c = 8.1–10%; HbA1c ≥ 10.1% | n.d. | Four groups: HbA1c ≤ 6%; HbA1c = 6.1–8%; HbA1c = 8.1–10%; HbA1c ≥ 10.1% | n.d. |

| Dogan et al. (2015) [23] | Prospective | 20 | Diabetic group: 53.54 ± 4.01; nondiabetic group: 52.14 ± 3.93 | 2010–2011 | 7 | 39 | n.d. | 2 | HbA1c 4.87 ± 0.53% | All diabetic patients: oral antidiabetics, exclusion criteria: insulin-therapy | “Well controlled”: 6.37 ± 1.28% | “At least 5 years” |

| Okamoto et al. (2018) [24] | Retrospective | 289 | Complications group: 62.8 ± 2.6; no complications group: 54.7 ± 13.1 | 2006–2013 | 0.75 | 298 | 100 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Al Amri et al. (2015) [25] | Prospective | 91 | HbA1c ≤ 6%: 48.5(45–52); HbA1c = 6.1–8%: 50.1(46–55); HbA1c = 8.1–10%: 50.5(45–59); | k.A. | 24 | n.d. | n.d. | 2 | HbA1c < 6% | k.A. | Three groups: HbA1c ≤ 6% (controls included); HbA1c = 6.1–8%; HbA1c = 8.1–10% | n.d. |

| de Araujo Nobre et al. (2016) | Retrospective | 70 | 59(41–80) | 1999–2007 | 60 | 352 | 89.8; group with type 1 diabetes mellitus: 80; group with type 1 diabetes mellitus: 90.5 | 1 and 2 | No controlgroup | “Treated”; no further information | n.d. | n.d. |

| Al Amri et al. (2017) [26] | Retrospective | 108 | Immediately loaded group: 50.6 ± 2.2; conventional loading group 51.8 ± 1.7 | n.d. | 24 | 108 | 100 | 2 | No controlgroup | n.d. | No initial HbA1c; At 12- and 24-month follow-up, the mean HbA1c levels in group 1 (immediately loading) and 2 (conventional loading) were 5.4%(4.8–5.5%) and 5.1%(4.7–5.4%) and 5.1%(4.7–5.2%) and 4.9%(4.5–5.2%) | Immediately loaded group: 9.2 ± 2.4 years; conventional loaded 8.5 ± 0.4 years |

| Al Amri et al. (2017) [27] | Prospective | 45 | Diabetic group: 42.4(40–46); nondiabetic group: 41.8(39–44) | n.d. | 24 | 45 | n.d. | 2 | HbA1c < 4.5% (visually, boxplot) | Antihyperglycemic drugs, dietary control | “Well controlled”: no exact data given, but visually (boxplots) the baseline HbA1c is significantly higher in the diabetic group (visually < 7%) than in nondiabetic control group (visually < 4.5%) | 14.5 ± 0.7 months |

| Soh et al. (2020) [28] | Retrospective | 89 | n.d. | 2019–2020 | 3 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Mohanty et al. (2018) [29] | Cross-sectional | 208 | n.d. | n.d. | 96–120 | 425 | Diabetic group: 70.7, periodontitis group: 83.3, smokers group: 80.9, bruxism group:86.3 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Aguilar-Salvatierra et al. (2016) [30] | Prospective | 85 | Group 1: 57 ± 3.8; group 2: 57 ± 3.8; group 3: 61 ± 1.9 | n.d. | 48 | 85 | Group 1: 100; group 2: n.d.; group 3: 86.3 | 2 | Three groups: HbA1c ≤ 6%; HbA1c = 6.1–8%; HbA1c = 8.1–10% | Oral hypoglycemic agents with similar doses | Three groups: HbA1c ≤ 6%; HbA1c = 6.1–8%; HbA1c = 8.1–10% | n.d. |

| Rekawek et al. (2021) [31] | Retrospective | 286 | n.d. | 2006–2012 | 60 (and more) | 748 | n.d. | n.d. | HbA1c < 8% | k.A. | > 8% “uncontrolled diabetes” | n.d. |

| Jagadeesh et al. (2020) [32] | Retrospective | 342 | n.d. | n.d. | 24 | 580 | 87.5 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Kandasamy et al. (2018) [33] | Retrospective | 200 | 47.5 | n.d. | 96–180 | 650 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Pedro et al. (2017) [34] | Prospective | 23 | 71.05(65–80) | 2009–2013 | 48 | 57 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Yadav et al. (2018) [35] | RCT | 88 | Flap group: 54.35 ± 14.51; Flapless group: 57.82 ± 13.99 | 2013–2015 | 30 | 88 | n.d. | 2 | n.d. | “Controlled” (under medication) | Inclusion criterion: HbA1c less than 7%; Flap group: 6.59 ± 0.42%; Flapless group: 6.75 ± 0.30% | Flap group: 6.55 ± 4.01 years; Flapless group: 6.91 ± 3.86 years |

| Khan et al. (2016) [36] | Retrospective | 83 | n.d. | 2010–2015 | n.d. | 220 | 86,8 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| French et al. (2021) [37] | Retrospective | 4247 | 53.8 ± 13.5 | 1995–2019 | 54 | 10,871 | 98.9 (3 years), 98.5 (5 years), 96.8 (10 years), and 94.0 (15 years) | Mellitus | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Alberti et al. (2020) [38] | Retrospective | 204 | 57.3 ± 13.7 | 2005–2018 | 68 | 929 | Diabetic group: 96.51, nondiabetic group: 94.74 | 1 and 2 | n.d. | Diet:5, Metformin:7, Insuline:3, Sulfonylureas:1, Metformin + Sulfonylureas:3, Metformine + Pioglitazone + Glicazide:1 | 6.40 ± 0.36% (isurgery) | n.d. |

| Krebs et al. (2019) [39] | Retrospective | 106 | 70.9(45–91) | 1991–1997 | 227 | 274 | n.d. | Mellitus | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Dalago et al. (2017) [40] | Retrospective | 183 | 59.3 | 1998–2012 | 68 | 938 | 98.3 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| De Araújo Nobre et al. (2017) [41] | Prospective | 22,009 | 48.5 ± 15.6 | 2012–2015 | 24 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Mayta-Tovalino et al. 2019) [42] | Retrospective | 431 | n.d. | 2006–2017 | 132 | 1279 | 82.02 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Kissa et al. (2020) [43] | Cross-sectional | 145 | 58.3 | 04/2017–12/2017 | 77 | 642 | n.d. | Mellitus | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Krennmair et al. (2018) [44] | Prospective | 85 | 56.7 ± 11.2 | 2007–2009 | 60 | 295 | 99 | 2 | n.d. | n.d. | ≤ 7,5% controlled (> 7.5% = Exclusion criteria) | n.d. |

| Al-Sowygh et al. (2018) [45] | Cross-sectional | 93 | Three diabetic groups; group 1: 51.5(46–57), group 2: 53.7 (42–56), group 3: 55.9 (49–59); nondiabetic group: 50.1(41–53) | n.d. | n.d. | 148 | n.d. | 2 | Non-diabetic individuals with HbA1c < 6% (mean:5.8%) | n.d. | Group 1: HbA1c 6.1–8%(mean:6.7%); group 2: HbA1c 8.1–10%(mean:9.2); group 3: HbA1c > 10%(mean:11.4); | Group 1: 10.7(7–11.2) years, group 2: 9.4(8–10.6) years, group 3: 12.6(9.9–14.1) years |

| Corbella et al. (2020) [46] | Retrospective | 112 | 57.3 ± 13.7 | 2004–2019 | 52 | 344 | 91.69 (12 years) | Mellitus | No controlgroup | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Al Amri et al. (2017) [47] | Prospective | 24 | Prediabetic group: 44.5(41–49); nondiabetic group: 43.3(39–47) | n.d. | 12 | 24 | 100 | Prediabetes | HbA1c: (baseline:) 4.4 ± 0.2% | n.d. | Baseline: Prediabetic group:6.1 ± 0.4; nondiabetic group:4.4 ± 0.2; follow-up values given | n.d. |

| Weinstein et al. (2020) [48] | Cross-sectional | 248 | 63.4 (women); 62.5 (men) | Unclear | 5 | 1162 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

n.d. no data provided

Diabetes and osseointegration

Osseointegration is the process of osseous healing and bone remodeling building an actual interface between the living bone tissue and the implant surface, after implant insertion. This process is crucial for implant stability as well as inflammation-free survival [8].

In a prospective clinical study, 22 implants were placed in diabetics and 21 implants in a healthy control group (12 patients each). The stability values were comparable both at the time of implant insertion (ISQ 55.4 ± 6.5 vs. 59.6 ± 4.1, p = 0.087) and when the implant was exposed after 4 months (ISQ 73.7 ± 3.5 vs. 75.7 ± 3.2, p = 0.148) [20]. In another retrospective case–control study, 257 subjects were included, 121 with and 136 without diabetes; diabetes was defined as well controlled with an HbA1c below 8%. Implant failure in the osseointegration phase was observed in 17 cases in the diabetes group (4.5%) and 16 cases in the control group (4.4%), so that a non-significant difference has been concluded (p = 0.365) [14].

High primary stability, sufficient osseointegration and healthy surrounding tissue are prerequisites for concepts such as immediate or early restoration of the implants with prosthetic restorations. Immediate loading in patients with type 2 diabetes was investigated in two studies. In the retrospective cohort study with 108 diabetics, the immediately loaded implants showed an identical survival as those after 3 months with delayed loading (100% each) [66]. Next, in a prospective clinical study, the diabetic patients were divided into two groups based on the HbA1c value (Hba1c 6.1–8% and 8.1–10%) and compared with a control group with an HbA1c ≤ 6%. The implant survival rate in the control group and the group with an HbA1c between 6.1 and 8% was 100%, the group with an HbA1c of 8.1–10% showed an implant survival rate of 95.4% [30].

Regarding the question of osseointegration in prediabetes, one study could show similar success rates of implant healing in prediabetes as in the healthy collective [47].

Diabetes and peri-implantitis

As diabetes mellitus is today seen as a systemic parainflammatic status [75] that is known to be associated with periodontitis and tooth loss [76], it is clear that the question of an increased risk of developing peri-implantitis in these patients is the subject of current research.

Thus, 23 studies could be included which contain a statement on peri-implantitis and diabetes mellitus or prediabetes. In fact, the conclusions on the influence of hyperglycemia on peri-implant inflammation are still heterogeneous. 12 clinical studies (1× cross-sectional study, 5× prospective, 6× retrospective) showed no increased risk of developing peri-implantitis with manifest diabetes mellitus [17, 23, 24, 27, 34, 38–41, 44, 46, 77]. On the other hand, six studies indicated an increased risk of peri-implant inflammation, with the highest determined relative risk being given as 8.65 [15, 28, 31, 48]. Two of these publications showed this especially in poorly controlled diabetes mellitus with an HbA1c > 8% with increased probing depths, bleeding on probing and peri-implant bone resorption [19, 45]. In five studies, no clear conclusion could be drawn from the data obtained, so that the question of an increased risk was not answered [10, 25, 33, 43, 64]. However, the available aggregated literature consistently concluded that diabetes mellitus represents a risk factor for the development of peri-implant inflammation, although most studies point to a lack of high-quality and long-term studies on this research area [8, 50, 51, 54–56, 58, 60–63].

Furthermore, two studies examined the effect of regular professional oral hygiene measures on the incidence of peri-implant inflammation in diabetics. In addition to a reduction in the clinical indicators of peri-implantitis, both studies could also show an improvement in the HbA1c value in the longitudinal course [25, 48].

Besides, two studies were included on the question of the influence of prediabetes on peri-implantitis. The prospective study by Al-Amri et al. with 24 test persons (12 prediabetic metabolic condition, 12 healthy) showed comparable clinical and radiological peri-implant findings in a 1-year observation interval, so that no increased risk was concluded [26]. The cross-sectional study by Alrabiah et al. with 79 subjects, however, indicated a higher incidence of peri-implant inflammation (probing depths, bleeding on probing, plaque index and peri-implant bone resorption) in prediabetes [13].

Diabetes and implant survival

The results regarding diabetes and implant survival are heterogeneous. Five studies showed no negative influence [10, 11, 38, 42, 44], two showed a non-significant [29, 36] and six a significantly negative influence of diabetes on implant survival [12, 16, 32, 37]. For example, the study of Alberti et al. [38] showed no significant difference of the implant survival after 10 years in patients with diabetes (survival rate of 96.5%) compared to patients without diabetes mellitus (survival rate of 94.8%), whereas the study of French et al. [37] identified diabetes mellitus with a hazard ratio of 2.25 as a risk factor for implant failure in a multivariate analysis, implicating an over two times higher risk for failure of dental implants in patients with diabetes mellitus. In addition, eight aggregated literature references could be included on this question, whereby in seven publications, it was concluded that diabetes mellitus does not seem to have a significant influence on implant survival [8, 51, 52, 55–58, 63]. This includes two meta-analyses. The first meta-analysis demonstrated a relative risk of implant loss in these patients of 1.43, indicating a 43% higher risk for implant loss in patients with diabetes. Even though this corresponds with a confidence interval of 0.54–3.82 and a p value of p = 0.07, to a statistically insignificant increase in risk [51]. The other meta-analysis calculated a similar relative risk of 1.39 with a confidence interval of 0.58–3.30, which is also not statistically significant with a p value of p = 0.46 [58].

Two further studies were included that examined implant survival in prediabetes. Both, the cross-sectional and prospective studies, showed a similar level of implant loss in the prediabetic and the control group [13, 47].

Diabetes and bone augmentation

We could identify one prospective study, that evaluated the effect of diabetes mellitus on maxillary sinus augmentation. Krennmair et al. performed a sinus lift with two-stage implant placement in a prospective study with a 5-year observation interval. In the evaluation, diabetics with an HbA1c < 7.5% were included and compared with non-diabetics. There was no difference in terms of bone augmentation, implant survival or peri-implant bone alteration [44]. A study on prediabetes and bone augmentation was not identified.

Influence of quality of glycemic control

Two studies were included that demonstrated an influence of the quality of the blood sugar control on therapy with dental implants. In the cross-sectional study by Al-Sowygh et al. 93 patients were divided into four groups based on the HbA1c (< 6%, 6.1–8%, 8.1–10%, > 10%). It was found that with increasing HbA1c a significant deterioration in the clinical indicators for peri-implantitis could be observed. A significant difference could be shown in the group comparison of diabetic patients with a HbA1c 6.1–8% and > 8.1% [45]. The work by Eskow et al. comes to a comparable conclusion. They could show a positive correlation between the HbA1c value and peri-implant mucositis and implant loss [10]. Likewise, three meta-analyses were included in the aggregated literature. One analysis could show a positive correlation of the HbA1c and the bleeding on probing, but not with probing depths [50]. The other two analyses, on the other hand, showed no association between increased HbA1c and implant loss [57] or a correlation of HbA1c with clinical parameters of peri-implant complications [58].

Influence of duration of diabetes disease

Information on the duration of the disease were given in 10 of 40 studies. The information remained descriptive in all studies. Therefore, no correlation of the duration of the disease and the possible influence on the implant therapy could be found.

Influence of supportive therapy

The use of perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis and disinfecting mouthwash was reported in almost every study. No publication focused on the effect of an adjuvant anti-infective therapy on implant success in prediabetic or diabetic patients.

Conclusions

This update was carried out on the basis of the publication of a large number of new studies in recent years, regarding dental implant insertion and possible complications in patients with diabetes mellitus in the last years. Therefore, for this update we could include a total number of 56 titles, consisting of 40 clinical studies and 16 titles of aggregated literature. This high number is an indication of the actuality and high interest in this research area and the large number of scientific questions that remain unanswered. Despite the large number of scientific publications, the level of evidence is not always high and the results are sometimes very heterogeneous. Furthermore, although the review process is quality assessed and indepentently performed by two of the reviewers (JWa, HN), but still is no automated, fully objective process.

In Germany around 7 billion people suffer from diabetes mellitus, with an estimated number of at least 2 billion cases on top [78]. In addition, prediabetes represents an increasing health problem with an annual conversation rate of 5–10% in manifest type 2 diabetes mellitus [79] and as it could be shown in follow-up data, the risk of developing diabetic microvascular complications is not only increased in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus but already in patients with prediabetes [80].

Accordingly, diabetes mellitus should be recognized as a potential risk factor for delayed osseointegration, the occurrence of peri-implant inflammation and poor implant survival and has to be taken into account in patient management and treatment decisions as well as follow-up care.

Previous studies clearly showed, that poorly controlled HbA1c can have negative effects on osseointegration and primary stability of dental implants, as we could already show in our review in 2016 [8], but the information on osseointegration in well controlled diabetes mellitus is still heterogeneous. Nevertheless, the indication for immediate and early loading should be viewed critically, especially in poorly controlled diabetes mellitus.

The influence of diabetes mellitus on the development of peri-implant inflammation in the early phase is unclear due to the heterogeneous data situation. In contrast, the risk seems to increase over time after implantation. Hence, risk-adapted follow-up care should be carried out after implant placement.

There are no significant differences in the survival rates in the first few years of diabetics compared to the healthy comparison group. However, in the long term, the risk of implant loss seems to be increased as previous studies could show [81–83]. Referring to prediabetes, this seems to have no influence on dental implant loss at all.

Furthermore, the evidence available on the influence of the quality of blood glucose control on the success of implant therapy is heterogeneous and there is insufficient evidence on the possible influence of the duration of the illness of diabetes mellitus on implant therapy. The final assessment regarding the influence of the duration of diabetes mellitus is also still pending.

In conclusion the results of our systematic review and the included literature more or less confirmed earlier knowledge in this field [8]. It has to be mentioned, that especially the preoperative preparation and evaluation of possible risk factors as well as the postoperative visits and recall gains importance, as the implant insertion itself is already highly standardized and perioperative anti-infective procedures are carried out in most cases. In addition, we included literature regarding oral rehabilitation with dental implants in prediabetic conditions in this review. Whereas, prediabetes seems to have no influence on implant survival rates at all.

Taking the existing evidence together, it can be concluded that oral rehabilitation with dental implants in patients with prediabetes and diabetes mellitus is a safe and predictable procedure. In times of precision medicine, a precise indication and a risk-adapted approach and adopted recall system for patients with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes mellitus is inevitable and provides a high probability for implant success.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

JWa has managed the literature search, collected the original data, has done the data analysis and has written the manuscript. JHS has done the data analysis and revised the manuscript. JWi is the head of the project and developed the project. He revised the manuscript. HN collected the original data, has done the data analysis and critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. No sources of funding contributed to this manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Atkinson MA, Eisenbarth GS, Michels AW. Type 1 diabetes. Lancet (London, England) 2014;383:69–82. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60591-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tabák AG, Herder C, Rathmann W, Brunner EJ, Kivimäki M. Prediabetes: a high-risk state for diabetes development. Lancet (London, England) 2012;379:2279–2290. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60283-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zheng Y, Ley SH, Hu FB. Global aetiology and epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its complications. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14:88–98. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2017.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khader YS, Dauod AS, El-Qaderi SS, Alkafajei A, Batayha WQ. Periodontal status of diabetics compared with nondiabetics: a meta-analysis. J Diabetes Complicat. 2006;20:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abiko Y, Selimovic D. The mechanism of protracted wound healing on oral mucosa in diabetes. Review. Bosnian J Basic Med Sci. 2010;10:186–191. doi: 10.17305/bjbms.2010.2683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiao H, Xiao E, Graves DT. Diabetes and its effect on bone and fracture healing. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2015;13:327–335. doi: 10.1007/s11914-015-0286-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naujokat H, Kunzendorf B, Wiltfang J. Dental implants and diabetes mellitus—a systematic review. Int J Implant Dent. 2016;2:5. doi: 10.1186/s40729-016-0038-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moga C, GB, Schopflocher D, Harstall C. (ed Edmonton AB: Institute of Health Economics); 2012.

- 10.Eskow CC, Oates TW. Dental implant survival and complication rate over 2 years for individuals with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2017;19:423–431. doi: 10.1111/cid.12465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ormianer Z, Block J, Matalon S, Kohen J. The effect of moderately controlled type 2 diabetes on dental implant survival and peri-implant bone loss: a long-term retrospective study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2018;33:389–394. doi: 10.11607/jomi.5838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castellanos-Cosano L, et al. Descriptive retrospective study analyzing relevant factors related to dental implant failure. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2019;24:e726–e738. doi: 10.4317/medoral.23082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alrabiah M, et al. Survival of adjacent-dental-implants in prediabetic and systemically healthy subjects at 5-years follow-up. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2019;21:232–237. doi: 10.1111/cid.12715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sghaireen MG, et al. Comparative evaluation of dental implant failure among healthy and well-controlled diabetic patients—a 3-year retrospective study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17145253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papantonopoulos G, Gogos C, Housos E, Bountis T, Loos BG. Prediction of individual implant bone levels and the existence of implant “phenotypes”. Clin Oral Implant Res. 2017;28:823–832. doi: 10.1111/clr.12887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Atarchi AR, Miley DD, Omran MT, Abdulkareem AA. early failure rate and associated risk factors for dental implants placed with and without maxillary sinus augmentation: a retrospective study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2020;35:1187–1194. doi: 10.11607/jomi.8447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alasqah MN, et al. Peri-implant soft tissue status and crestal bone levels around adjacent implants placed in patients with and without type-2 diabetes mellitus: 6 years follow-up results. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2018;20:562–568. doi: 10.1111/cid.12617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh R, et al. A 10 years retrospective study of assessment of prevalence and risk factors of dental implants failures. J Family Med Prim Care. 2020;9:1617–1619. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1171_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al Zahrani S, Al Mutairi AA. Crestal bone loss around submerged and non-submerged dental implants in individuals with type-2 diabetes mellitus: a 7-year prospective clinical study. Med Princ Pract. 2019;28:75–81. doi: 10.1159/000495111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erdogan Ö, et al. A clinical prospective study on alveolar bone augmentation and dental implant success in patients with type 2 diabetes. Clin Oral Implant Res. 2015;26:1267–1275. doi: 10.1111/clr.12450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oztel M, Bilski WM, Bilski A. Risk factors associated with dental implant failure: a study of 302 implants placed in a regional center. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2017;18:705–709. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gómez-Moreno G, et al. Peri-implant evaluation in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: a 3-year study. Clin Oral Implant Res. 2015;26:1031–1035. doi: 10.1111/clr.12391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dŏgan Ş, et al. Evaluation of clinical parameters and levels of proinflammatory cytokines in the crevicular fluid around dental implants in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2015;30:1119–1127. doi: 10.11607/jomi.3787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okamoto T, et al. Factors affecting the occurrence of complications in the early stages after dental implant placement: a retrospective cohort study. Implant Dent. 2018;27:221–225. doi: 10.1097/id.0000000000000753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al Amri MD, et al. Effect of oral hygiene maintenance on HbA1c levels and peri-implant parameters around immediately-loaded dental implants placed in type-2 diabetic patients: 2 years follow-up. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2016;27:1439–1443. doi: 10.1111/clr.12758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Al Amri MD, et al. Comparison of clinical and radiographic status around immediately loaded versus conventional loaded implants placed in patients with type 2 diabetes: 12- and 24-month follow-up results. J Oral Rehabil. 2017;44:220–228. doi: 10.1111/joor.12466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al Amri MD, Abduljabbar TS. Comparison of clinical and radiographic status of platform-switched implants placed in patients with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus: a 24-month follow-up longitudinal study. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2017;28:226–230. doi: 10.1111/clr.12787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soh N, Duraisamy R, Arthi B. Evaluation of osseointegration and crestal bone loss associated with implants placed in diabetic and other medically compromised patients. J Long Term Eff Med Implants. 2020;30:247–253. doi: 10.1615/JLongTermEffMedImplants.2020035938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohanty R, Sudan P, Dharamsi A, Mokashi R, Misurya A. Risk assessment in long-term survival rates of dental implants: a prospective clinical study. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2018;19:587–590. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aguilar-Salvatierra A, Calvo-Guirado JL. Peri-implant evaluation of immediately loaded implants placed in esthetic zone in patients with diabetes mellitus type 2: a two-year study. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2016;27:156–161. doi: 10.1111/clr.12552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rekawek P, et al. Hygiene recall in diabetic and nondiabetic patients: a periodic prognostic factor in the protection against peri-implantitis? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021;79:1038–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2020.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jagadeesh KN, et al. Assessment of the survival rate of short dental implants in medically compromised patients. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2020;21:880–883. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-2854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kandasamy B, et al. Long-term retrospective study based on implant success rate in patients with risk factor: 15-year follow-up. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2018;19:90–93. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pedro RE, et al. Influence of age on factors associated with peri-implant bone loss after prosthetic rehabilitation over osseointegrated implants. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2017;18:3–10. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yadav R, et al. Crestal bone loss under delayed loading of full thickness versus flapless surgically placed dental implants in controlled type 2 diabetic patients: a parallel group randomized clinical trial. J Prosthodont. 2018;27:611–617. doi: 10.1111/jopr.12549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khan FR, Ali R, Nagi SE. A review of the failed cases of dental implants at a university hospital in Karachi, Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2016;66(Suppl 3):S24–s26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.French D, Ofec R, Levin L. Long term clinical performance of 10 871 dental implants with up to 22 years of follow-up: a cohort study in 4247 patients. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2021;23:289–297. doi: 10.1111/cid.12994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alberti A, et al. Influence of diabetes on implant failure and peri-implant diseases: a retrospective study. Dent J. 2020;8:70. doi: 10.3390/dj8030070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krebs M, et al. Incidence and prevalence of peri-implantitis and peri-implant mucositis 17 to 23 (18.9) years postimplant placement. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2019;21:1116–1123. doi: 10.1111/cid.12848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dalago HR, Schuldt Filho G, Rodrigues MA, Renvert S, Bianchini MA. Risk indicators for peri-implantitis. A cross-sectional study with 916 implants. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2017;28:144–150. doi: 10.1111/clr.12772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Araújo Nobre M, Maló P. Prevalence of periodontitis, dental caries, and peri-implant pathology and their relation with systemic status and smoking habits: results of an open-cohort study with 22009 patients in a private rehabilitation center. J Dent. 2017;67:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2017.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mayta-Tovalino F, et al. An 11-year retrospective research study of the predictive factors of peri-implantitis and implant failure: analytic-multicentric study of 1279 implants in Peru. Int J Dent. 2019 doi: 10.1155/2019/3527872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kissa J, et al. Prevalence and risk indicators of peri-implant diseases in a group of Moroccan patients. J Periodontol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jper.20-0549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krennmair S, et al. Implant health and factors affecting peri-implant marginal bone alteration for implants placed in staged maxillary sinus augmentation: a 5-year prospective study. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2019;21:32–41. doi: 10.1111/cid.12684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Al-Sowygh ZH, Ghani SMA, Sergis K, Vohra F, Akram Z. Peri-implant conditions and levels of advanced glycation end products among patients with different glycemic control. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2018;20:345–351. doi: 10.1111/cid.12584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Corbella S, Alberti A, Calciolari E, Francetti L. Medium- and long-term survival rates of implant-supported single and partial restorations at a maximum follow-up of 12 years: a retrospective study. Int J Prosthodont. 2021;34:183–191. doi: 10.11607/ijp.6883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Al Amri MD, Abduljabbar TS, Al-Kheraif AA, Romanos GE, Javed F. Comparison of clinical and radiographic status around dental implants placed in patients with and without prediabetes: 1-year follow-up outcomes. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2017;28:231–235. doi: 10.1111/clr.12788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weinstein T, et al. Prevalence of peri-implantitis: a multi-centered cross-sectional study on 248 patients. Dent J. 2020;8:80. doi: 10.3390/dj8030080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sharif MO, Janjua-Sharif FN, Ali H, Ahmed F. Systematic reviews explained: AMSTAR-how to tell the good from the bad and the ugly. Oral Health Dent Manag. 2013;12:9–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jiang X, Zhu Y, Liu Z, Tian Z, Zhu S. Association between diabetes and dental implant complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Odontol Scand. 2021;79:9–18. doi: 10.1080/00016357.2020.1761031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moraschini V, Barboza ES, Peixoto GA. The impact of diabetes on dental implant failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;45:1237–1245. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2016.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schimmel M, Srinivasan M, McKenna G, Müller F. Effect of advanced age and/or systemic medical conditions on dental implant survival: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Implant Res. 2018;29(Suppl 16):311–330. doi: 10.1111/clr.13288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Singh K, Rao J, Afsheen T, Tiwari B. Survival rate of dental implant placement by conventional or flapless surgery in controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: a systematic review. Indian J Dent Res. 2019;30:600–611. doi: 10.4103/ijdr.IJDR_606_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ting M, Craig J, Balkin BE, Suzuki JB. Peri-implantitis: a comprehensive overview of systematic reviews. J Oral Implantol. 2018;44:225–247. doi: 10.1563/aaid-joi-D-16-00122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Souto-Maior JR, et al. Influence of diabetes on the survival rate and marginal bone loss of dental implants: an overview of systematic reviews. J Oral Implantol. 2019;45:334–340. doi: 10.1563/aaid-joi-D-19-00087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.de Oliveira-Neto OB, Santos IO, Barbosa FT, de Sousa-Rodrigues CF, de Lima FJ. Quality assessment of systematic reviews regarding dental implant placement on diabetic patients: an overview of systematic reviews. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2019;24:e483–e490. doi: 10.4317/medoral.22955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shi Q, Xu J, Huo N, Cai C, Liu H. Does a higher glycemic level lead to a higher rate of dental implant failure?: a meta-analysis. J Am Dent Assoc. 2016;147:875–881. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2016.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shang R, Gao L. Impact of hyperglycemia on the rate of implant failure and peri-implant parameters in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Dent Assoc. 2021;152:189–201.e181. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2020.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lagunov V, Sun J, George R. Evaluation of biologic implant success parameters in type 2 diabetic glycemic control patients versus health patients: a meta-analysis. J Invest Clin Dent. 2019 doi: 10.1111/jicd.12478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dreyer H, et al. Epidemiology and risk factors of peri-implantitis: a systematic review. J Periodontal Res. 2018;53:657–681. doi: 10.1111/jre.12562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Monje A, Catena A, Borgnakke WS. Association between diabetes mellitus/hyperglycaemia and peri-implant diseases: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol. 2017;44:636–648. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Turri A, Rossetti PH, Canullo L, Grusovin MG, Dahlin C. Prevalence of peri-implantitis in medically compromised patients and smokers: a systematic review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2016;31:111–118. doi: 10.11607/jomi.4149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Meza Maurício J, et al. An umbrella review on the effects of diabetes on implant failure and peri-implant diseases. Braz Oral Res. 2019;33:e070. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107bor-2019.vol33.0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Guobis Z, Pacauskiene I, Astramskaite I. General diseases influence on peri-implantitis development: a systematic review. J Oral Maxillofac Res. 2016;7:e5. doi: 10.5037/jomr.2016.7305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Romandini M, et al. Prevalence and risk/protective indicators of peri-implant diseases: a university-representative cross-sectional study. Clin Oral Implant Res. 2021;32:112–122. doi: 10.1111/clr.13684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schwarz F, Derks J, Monje A, Wang HL. Peri-implantitis. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S267–s290. doi: 10.1002/jper.16-0350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chambrone L, Palma LF. Current status of dental implants survival and peri-implant bone loss in patients with uncontrolled type-2 diabetes mellitus. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2019;26:219–222. doi: 10.1097/med.0000000000000482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Javed F, Romanos GE. Impact of diabetes mellitus and glycemic control on the osseointegration of dental implants: a systematic literature review. J Periodontol. 2009;80:1719–1730. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rokaya D, Srimaneepong V, Wisitrasameewon W, Humagain M, Thunyakitpisal P. Peri-implantitis update: risk indicators, diagnosis, and treatment. Eur J Dent. 2020;14:672–682. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1715779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Marcantonio C, Nicoli LG, Marcantonio Junior E, Zandim-Barcelos DL. Prevalence and possible risk factors of peri-implantitis: a concept review. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2015;16:750–757. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Heitz-Mayfield LJA, Salvi GE. Peri-implant mucositis. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S257–s266. doi: 10.1002/jper.16-0488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kormas I, et al. Peri-implant diseases: diagnosis, clinical, histological, microbiological characteristics and treatment strategies. A narrative review. Antibiotics (Basel) 2020 doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9110835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Renvert S, Quirynen M. Risk indicators for peri-implantitis. A narrative review. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2015 doi: 10.1111/clr.12636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fretwurst T, Nelson K. Influence of medical and geriatric factors on implant success: An overview of systematic reviews. Int J Prosthodont. 2021. 10.11607/ijp.7000 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 75.Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation, metaflammation and immunometabolic disorders. Nature. 2017;542:177–185. doi: 10.1038/nature21363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Holmstrup P, et al. Comorbidity of periodontal disease: two sides of the same coin? An introduction for the clinician. J Oral Microbiol. 2017;9:1332710. doi: 10.1080/20002297.2017.1332710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.de Araújo Nobre M, Maló P, Gonçalves Y, Sabas A, Salvado F. Dental implants in diabetic patients: retrospective cohort study reporting on implant survival and risk indicators for excessive marginal bone loss at 5 years. J Oral Rehabil. 2016;43:863–870. doi: 10.1111/joor.12435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Deutsche Diabetes Gesellschaft (DDG) und. diabetesDE – Deutsche Diabetes-Hilfe. Deutscher Gesundheitsbericht Diabetes 2020; 2020. https://www.deutsche-diabetes-gesellschaft.de/fileadmin/user_upload/06_Gesundheitspolitik/03_Veroeffentlichungen/05_Gesundheitsbericht/2020_Gesundheitsbericht_2020.pdf.

- 79.Knowler WC, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Perreault L, et al. Regression from prediabetes to normal glucose regulation and prevalence of microvascular disease in the diabetes prevention program outcomes study (DPPOS) Diabetes Care. 2019;42:1809–1815. doi: 10.2337/dc19-0244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Olson JW, et al. Dental endosseous implant assessments in a type 2 diabetic population: a prospective study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2000;15:811–818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]