Abstract

Objective

To evaluate service use, clinical outcomes and user experience related to telephone-based digital triage in urgent care.

Design

Systematic review and narrative synthesis.

Data sources

Medline, Embase, CINAHL, Web of Science and Scopus were searched for literature published between 1 March 2000 and 1 April 2020.

Eligibility criteria for selecting studies

Studies of any design investigating patterns of triage advice, wider service use, clinical outcomes and user experience relating to telephone based digital triage in urgent care.

Data extraction and synthesis

Two reviewers extracted data and conducted quality assessments using the mixed methods appraisal tool. Narrative synthesis was used to analyse findings.

Results

Thirty-one studies were included, with the majority being UK based; most investigated nurse-led digital triage (n=26). Eight evaluated the impact on wider healthcare service use following digital triage implementation, typically reporting reduction or no change in service use. Six investigated patient level service use, showing mixed findings relating to patients’ adherence with triage advice. Evaluation of clinical outcomes was limited. Four studies reported on hospitalisation rates of digitally triaged patients and highlighted potential triage errors where patients appeared to have not been given sufficiently high urgency advice. Overall, service users reported high levels of satisfaction, in studies of both clinician and non-clinician led digital triage, but with some dissatisfaction over the relevance and number of triage questions.

Conclusions

Further research is needed into patient level service use, including patients’ adherence with triage advice and how this influences subsequent use of services. Further evaluation of clinical outcomes using larger datasets and comparison of different digital triage systems is needed to explore consistency and safety. The safety and effectiveness of non-clinician led digital triage also needs evaluation. Such evidence should contribute to improvement of digital triage tools and service delivery.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42020178500.

Keywords: health services administration & management, quality in health care, organisation of health services, qualitative research, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first systematic review to focus on the use of telephone based digital triage in urgent care.

This comprehensive, mixed-methods review covers a 20-year period, enabling evaluation of older literature prior to shifts of some services to non-clinician led models of service delivery.

Outcomes relating to cost-effectiveness, and staff focused outcomes were not within the review scope.

The review was limited to studies published in English, which may have led to some evidence being overlooked.

Background

Telephone based digital triage is widely used in urgent care.1 2 Urgent care is the ‘the range of responses that health and care services provide to people who require—or who perceive the need for—urgent advice, treatment or diagnosis’,3 and includes national or regional help-lines, out of hours centres and emergency care providers.

Digital triage involves a call handler or clinician using a digital triage tool to generate advice based on an assessment of a patient’s symptoms. Advice typically takes the form of signposting within defined levels of urgency to specific local services, such as an emergency department (ED), out of hours centre or general practice (GP) appointment; in some cases self-care advice is given.

Digital triage service delivery models vary widely. In England and Scotland digital triage is delivered by non-clinical call handlers, for example, through the 111 service, which operates 24/7, while in most other countries it is predominantly clinician (nurse) led.4–9 In part, digital triage has been implemented in response to increasing demand on primary care and EDs in the last several decades.10

Despite wide adoption over the last several decades, there is limited evaluation of its impact on wider healthcare service use, clinical outcomes and user experience. No previous systematic reviews have focused solely on services that use digital triage; instead reviewing telephone consultation and triage more broadly, including services that use digital triage and those that are not digitally supported.1 10 11

One review indicated that 50% of calls in the general healthcare setting (with studies predominantly conducted in primary care settings) could be handled completely over the telephone, showing the potential of telephone triage to manage face to face care demand.10 However, there are mixed findings relating to wider healthcare service use and very limited investigation of clinical outcomes.10 A previous review reported a high level of user satisfaction,10 while another highlighted that satisfaction with advice related to improved compliance with advice.11

Given technological development and, in some cases, the reorganisation of services in recent years,2 systematic reviews conducted several years ago (between 2005 and 2012)1 10–13 may have limited relevance to today’s services.

This review addresses the need for an up-to date evaluation of telephone-based digital triage within urgent care. It aims to evaluate wider healthcare service use, clinical outcomes and user experience in a range of in hours and out of hours urgent care settings in order to identify areas for improvement and the need for further research.

Method

This review uses a mixed-methods design and is reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) framework.14 See online supplemental appendix 1 for the PRISMA checklist.15

bmjopen-2021-051569supp001.pdf (196KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

No patient and public involvement (PPI) directly fed into the development or conduct of this review.

Eligibility criteria

Eligibility criteria have been developed using the population, interventions, comparators, outcomes and study designs principle16:

Population: studies that evaluated digital triage in the general population or within population subgroups (eg, older people).

-

Interventions: studies that assessed telephone based digital triage, which met all of the below criteria:

In services providing urgent care (excluding in-hours GP)

That was used by the general population (not condition specific services).

That result in signposting advice (referral to a local service, such as ED, GP, ambulance dispatch and in some cases self-care advice).

Outcomes: studies that evaluated at least one of the following: characteristics of service users and triage advice; healthcare service use following triage; clinical outcomes (including hospitalisations and mortality) and service user experience.

All empirical study types published between 1 March 2000 and 1 April 2020 in English were included: qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods studies.

Search strategy

The search strategy was designed with support from a librarian. Searches were conducted in Medline, Embase, CINAHL, Web of Science and Scopus. Terms relating to digital triage and urgent care settings (excluding in-hours GP) were used. See Medline search terms in online supplemental appendix 2. The search was restricted to studies published in English, including electronically published (Epub) studies ahead of print. Reference handsearches were conducted for all included full texts.

bmjopen-2021-051569supp002.pdf (158KB, pdf)

Study selection and data extraction

Articles were deduplicated ahead of study selection. Two reviewers screened studies independently at title and abstract stage and at full text stage using Covidence software. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion between the reviewers; where necessary a third reviewer was consulted. A PRISMA flow chart was is presented in the results.

A data extraction form was developed and initially piloted on three studies to confirm that key elements of studies were captured. See online supplemental appendix 3 for data extraction fields. Data were extracted independently by two reviewers, and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer. Study authors were contacted in cases where clarifications regarding study conduct were required.

bmjopen-2021-051569supp003.pdf (161.4KB, pdf)

Quality assessment

Quality assessment, including risk of bias, was conducted by two reviewers using the mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT),17 which enables the assessment of mixed study types. The assessment was used to provide context, rather than to exclude studies.18 Based on the number of MMAT criteria met, studies were categorised as high (if all five MMAT criteria were met), medium (if three or four criteria were met) or low quality (if two or less criteria were met).

Data synthesis

Narrative synthesis18 was used due to the diversity of designs in the included studies. This included: generating a preliminary synthesis, exploring relationships in findings across studies, assessing the robustness of the evidence and summarising findings.18 Statistical meta-analysis was not possible due to the heterogeneity of the included studies. Key findings within and between studies were grouped by outcome and visually summarised using a subgroup analyses method,18 which we modified to additionally present the strength of evidence. Where a visual summary was not possible due to heterogeneity of outcomes, findings were summarised in text.

Results

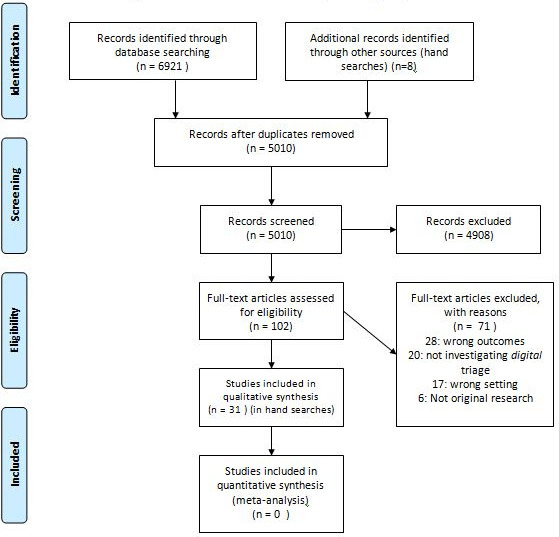

The search resulted in 6921 records, after duplicates were removed, there were 5010 records to screen at title and abstract level; 102 records were included for full-text screening, out of which 31 studies were included. See figure 1 for PRISMA flow chart.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Most included studies were of quantitative design (n=25)5 7 19–41 including: routine data analyses(n=16),5 7 19–25 27 29 34 35 37–39 surveys(n=6),26 28 31 33 40 41 controlled trials (n=2)30 36 and a quantitative descriptive study (n=1).32 There were fewer qualitative (n=4)42–45 and mixed-methods studies (n=2).6 46

Studies were mainly from the UK (n=17),5 6 20 21 23 26–29 32 36–38 40 42 43 46 with small numbers from Sweden (n=4),41 44 45 47 Australia (n=4),30 31 34 39 USA (n=3),7 19 22 Netherlands (n=2),25 33 Japan (n=1)35 and Portugal (n=1).24 Most included the full range of service users (n=24),5 6 19 21–26 28 30 32–36 38–41 43–46 but some focused on subsets: older adults,21 24 younger age groups,20 37 parents of children,31 men42 or adults with limited English proficiency (LEP).7

Most studies evaluated digital triage conducted by nurses (n=26),5 7 19–34 37 39 41–46 but some included non-clinicians (n=3),6 38 40 nurses and paramedics (n=1)36 or nurses and non-clinical call handler (n=1).35

Most studies were of identifiable call centre-based services: England’s former National Health Service (NHS) Direct20 21 23 26 28 29 37 42–44 46 and current NHS 111 service,38 40 Scotland’s NHS24,5 6 USA’s MayoClinic,7 19 22 Portugal’s Linha Saude 24,24 Swedish Health Direct,41 44 45 Australia’s Health Direct.34 A few involved smaller scale ‘unnamed’ implementations30 39 or GP cooperatives.25 32 33 Two were based in the emergency setting, one within an English ambulance service36 and one within an emergency telephone service in Japan.35 Table 1 shows characteristics of studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies (31 studies)

| Main outcome area | Author year Country Reference |

Study design | Sample/data size | Urgent or emergency care | Staff type conducting triage | Participants and service name | Comparator | Quality |

| User experience | Björkman 2018 Sweden44 |

Qualitative: 'Netnographic' method using information from online forums using six step |

Data collected from 3 online forums | Urgent | Nurse | General population | None | High |

| User experience | O'Cathain 2014 England40 |

Quantitative: Survey |

Survey sent to 1200 patients from 4 pilot sites, 1769 responded and were included for analysis | Urgent | Non-clinical call handler | General population | None | Medium |

| User experience | McAteer 2016 Scotland6 |

Mixed methods: survey and interviews | Survey: Age and sex-stratified random sample of 256 adults from each of 14 Scottish GP surgeries, final sample was 1190. Interviews: 30 semistructured interviews |

Urgent | Non-clinical call handler | General population (National Health Service (NHS) 24 users and non-users) | Interviewees (from survey respondents) grouped into satisfied users, dissatisfied users and non-users | High |

| User experience | Rahmqvist 2011 Sweden41 |

Quantitative: Survey |

Random sample of 660 callers, made at one call centre site in October 2008 | Urgent | Nurse | General population | (1) Cases: those who disagreed with nurse advice and felt they needed higher level of care; (2) Controls: those who disagreed with nurse advice OR felt they needed higher level of care; (3) other callers | Medium |

| User experience | Goode 2004 England43 |

Qualitative: Interview study |

60 interviews | Urgent | Nurse | General population | None | High |

| User experience | Winneby 2014 Sweden45 |

Qualitative: Interview study |

8 semistructured interviews | Urgent | Nurse | General population | None | High |

| User experience | Goode 2004 England42 |

Qualitative: Interview study |

10 semistructured interviews | Urgent | Nurse | Interviews focused on men | None | High |

| Patterns of triage advice | Payne 2001 England23 |

Routine data analysis | 56 450 calls | Urgent | Nurse | General population | None—comparisons within digital triage call data | High |

| Patterns of triage advice | Elliot 2015 Scotland5 |

Routine data analysis | 1 285 038 calls | Urgent | Nurse | General population | None—comparisons within digital triage call data | High |

| Patterns of triage advice | Zwaanswijk 2015 Netherlands25 |

Routine data analysis | 895 253 patients | Urgent | Nurse (GP cooperative) | General population | Some comparison with non-digital triage | High |

| Patterns of triage advice | Njeru 2017 USA7 |

Routine data analysis | 587 cases 587 controls |

Urgent | Nurse | Those aged over 18— (callers with and without limited English proficiency) | Patients with limited English proficiency compared with English proficient | High |

| Patterns of triage advice | Jacome 2018 Portugal24 |

Routine data analysis | 148 099 calls | Urgent | Nurse | General population (Older age groups 65+) |

None - Comparisons within digital triage call data | High |

| Patterns of triage advice | Hsu 2011 England21 |

Routine data analysis | 402 959 calls | Urgent | Nurse | Older age groups (aged over 65 years) | None | High |

| Patterns of triage advice | Cook 2013 England20 |

Routine data analysis | 358 503 calls | Urgent | Nurse | children aged 0–15 (<1, 1–3 and 4–15 years)) |

Comparisons between age groups | Medium |

| Patterns of triage advice | North 2010 USA22 |

Routine data analysis | 20 230 calls | Urgent | Nurse | General population (those with subscription and insurance) | Three comparison groups: (1)Triaged callers; (2) Emergency Department (ED) attendances; (3) Office (GP) visits. (Comparison of hospitalisation in these groups) |

Medium |

| Patterns of triage advice | North 2011 USA19 |

Routine data analysis | Over the 3-year period: 105 866 adult calls (65% of the total calls). Of these, 14 646 (14%) were made by a surrogate on behalf of the patient. | Urgent | Nurse | General population (aged over 18) | Surrogate vs self calls | Medium |

| Service use following triage | Lattimer 2000 England32 |

Quantitative descriptive: Cost-effectiveness report from controlled trial | >14 000 Control group (n=7308 calls) Intervention group that is, Nurse telephone consultation (n=7184 calls) |

Urgent | Nurse (within general practice cooperative) | General population | Usual care (referral to a General Practice) compared with nurse-led digital triage |

Medium |

| Service use following triage | Munro 2000 England29 |

Routine data analysis | Study corresponds to the 1st year of operation, where 68 500 NHS direct calls from the 1.3 million people served. | Urgent | Nurse | All contacts with these immediate care services (at time spanning before and after introduction of call centre based service) | Service use in regions where digital triage service was introduced, compared with regions with no implementation | High |

| Service use following triage | Dale 2003 England36 |

Controlled trial | 635 triaged calls 611 non-triaged calls |

Emergency | Nurse and paramedic (within emergency control room) | General population, calling the emergency service for non-emergency concerns (only those aged 2+) | The control group not offered triage was compared with calls digitally triaged either by nurses or paramedics. | High |

| Service use following triage | Foster 2003 England27 |

Routine data analysis and data linkage | 4493 calls, of which 193 were advised to go to Emergency Department (ED) | Urgent | Nurse | General population | Three comparison groups:

|

Medium |

| Service use following triage | Mark 2003 England46 |

Mixed methods (routine data analysis +interviews) | Numbers of calls analysed across 3 years: 5126 (year 1998) 5702 (1999) 4698 (2000) |

Urgent | Nurse | General population | n/a | Low |

| Service use following triage | Sprivulis 2004 Australia34 |

Routine data analysis & data linkage | 13 019 presentations to Emergency Department (ED) of which 842 were identified as having contacted Health-Direct within the 24 hours period prior to presentation. | Urgent | Nurse | General population—all patients who contacted the digital triage service during the 1-year study period |

|

High |

| Service use following triage | Dunt 2005 Australia30 |

Quantitative: four trials including surveys (self-reported service use) | Random sampling (350 households per trial site) | Urgent | Nurse | General population | 2 sites using ‘standalone’ telephone triage which used ‘call centre software’ 2 embedded telephone triage sites using paper based protocols |

Medium |

| Service use following triage | Munro 2005 England28 |

Quantitative: Surveys (care providers) | 571 surveys sent (188/297) responses from GP cooperatives, (35/35) for ambulance services and (200/239) for emergency departments | Urgent | Nurse | Surveys sent to care providers (general use of services following NHS direct implementations) | n/a | Medium |

| Service use following triage | Stewart 2006 England37 |

Routine data analysis & data linkage | 3312 calls to call centre based service, and 14 029 patients who attended Emergency Department (ED) | Urgent | Nurse | Children and young adults aged under 16 |

|

High |

| Service use following triage | Byrne 2007 England26 |

Quantitative: Survey | 268 callers | Urgent | Nurse | General public with 3 symptom types (abdominal pain or cough and/or sore throat) | None | High |

| Service use following triage | Morimura 2010 Japan35 |

Routine data analysis | 26 138 telephone consultations | Emergency | Nurse and call handler | General population | None | Medium |

| Service use following triage | Huibers 2013 Netherlands33 |

Quantitative: Questionnaires |

7039 questionnaires returned (from a total of 13 953 sent) | Urgent | Nurse | General population (users who had a telephone contact with a nurse) | None | High |

| Service use following triage | Turner 2013 England38 |

Routine data analysis | 400 000 calls to call centre based service in first year of operation analysed | Urgent | Nurse | General population | Matched sites: (1) Intervention sites: four digital pilot sites; (2)Control sites (North of Tyne, Leicester, Norfolk) |

High |

| Service use following triage | Turbitt 2015 Australia31 |

Quantitative: Surveys |

1150 parents attending Emergency Department (ED) (decline rate 19.9%) | Urgent | Nurse | Specific group | Some comparisons between parents who called and did not call but prior to attending ED | Medium |

| Service use following triage | Siddiqui 2019 Australia39 |

Routine data analysis and data linkage | 12 741 triaged cases linked to 72.577 ED presentations | Urgent | Nurse | General population | None | High |

ED, emergency department; GP, general practice.

Nineteen studies were rated as being of high quality,5–7 21 23–26 29 33 34 36–39 42–45 11 medium19 20 22 27 28 30–32 35 40 41 and 1 was low.46 Qualitative studies tended to be of higher quality, while quantitative studies were more variable. Reasons for lower quality among quantitative studies included inadequate description of accounting for confounders28 30 34 35 and risk of non-response bias.31 32 40 41 One mixed-methods study did not adequately describe integration of qualitative and quantitative components.46 In two of the qualitative studies details about how the findings were derived from the data could have been expanded.43 45 The quality assessment results are included in online supplemental appendix 4.

bmjopen-2021-051569supp004.pdf (309.2KB, pdf)

Patterns of use

Nine studies focused on patterns of triage advice; all used routine datasets.5 7 19–25 Key findings are summarised below; detailed findings from studies are in online supplemental table 1.

bmjopen-2021-051569supp005.pdf (227.3KB, pdf)

Characteristics of patients and callers

Presenting symptoms with highest frequency among patients, included: abdominal or digestive problems, 6.8%–12.2% of calls5 19 22 24 39 and respiratory problems, 11.3%–11.9%39 24 of calls. The majority of calls were made by women (range: 59%–72%).5 19 22–24 39

Calls about patients in younger age groups22 23 made up a comparatively high proportions of calls; 24% of calls were for 0–5 years in one study23 and another reported 15% of out of hours calls being for 0–4 years.5

User characteristics and triage advice urgency

Factors associated with triage advice urgency included:

Patient’s age: Two studies reported urgency to be lower in children and younger age groups23 20, one study reported a high proportion (47%) of calls about children aged (0–15) were resolved through self-care advice or health information.20 Two studies reported that urgency increased with age.19 24

Sex: Two studies reported women were more likely to receive lower urgency advice as compared with men; however, neither controlled for age or presenting symptoms,21 23 one suggested this may be explained by women seeking care advice earlier, before their symptoms progress and become more urgent.21

Symptoms: Two studies reported symptoms associated with higher urgency advice20 25; for example, calls about children with respiratory problems were more likely to be referred to emergency care as compared with other symptom types.20

Caller language proficiency: One case–control study reported that adults with LEP were more likely to receive higher urgency advice (ambulance, immediate ED attendance or urgent visit) (49.4% vs 39.0%; p<0.0004)7; groups in this study were balanced based on age and sex and comorbidities were controlled for.7

Service use and clinical outcomes following triage

Change in service use following digital triage implementation

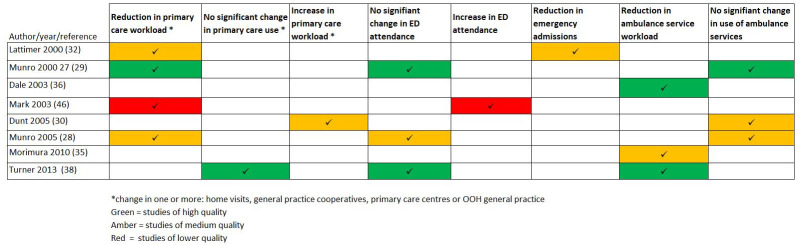

Eight studies reported on change in wider healthcare service use (primary care, ED use, ambulance use and emergency admissions) following implementation of digital triage.28–30 32 35 36 38 46 Of these, one investigated non-clinician led triage.38 Comparators included: rates of service use in patients receiving usual care (eg, GP referral) in comparison to those who were digitally triaged32 36; service use rates prior to implementation28 30 35 46; comparator regions with no digital triage implementation29 38 and national service use comparator.30

There were mixed findings across studies, as visually summarised in figure 2. Most reported reduction or no change in wider service use after implementation; there were two exceptions, which both evaluated clinician (nurse) led digital triage: one (rated as being a lower quality study) reported an increase in ED use.46 The other reported some increase in out of hours service use (GP clinic use and home visits) related to ‘standalone’ digital triage call centres in comparison to national comparator; however, this study differed to the other studies as it utilised household surveys to capture service use.30

Figure 2.

Findings from studies of out of hours (OOH) service use after digital triage implementation. ED, emergency department.

Online supplemental table 2 presents detailed findings from studies.

bmjopen-2021-051569supp006.pdf (280.6KB, pdf)

Patient level service use and adherence with advice

Six studies reported varying patient adherence to triage advice through evaluation of patients’ subsequent ED attendance.26 27 31 34 37 39 Four used routine data and data linkage with sample sizes ranging from: 3312 to 13 019 triage calls. Of these, three studies reported 60%–70% of patients who were advised to attend ED followed this advice27 34 37; one reported a range of 29%–69%, with higher compliance when ambulance was advised (53%–69%) and lowest compliance when self-transport to ED was recommended (29%).37

One small survey of 268 callers reported high levels of adherence with advice to attend ED (96%; 49 of 51 calls), to contact a GP (92%; 133 of 144) and to self care (93%; 64 of 69).26

Four studies reported proportions of patients who attended ED after receiving alternative triage advice (other than attending ED): 2.4%,27 9%34 37 and 22%.31 The latter included 51 of 1150 parents who had remained worried after calling the digital triage service.31 Results are showed in online supplemental table 3.

bmjopen-2021-051569supp007.pdf (230.7KB, pdf)

Safety

Four studies highlighted potential triage errors based on hospital admission rates.27 34 36 37 These mainly related to potential ‘undertriage’, where the advice was considered to be at too low a level of urgency in relation to clinical need. However, these findings were peripheral to the main aims of these studies.27 34 36 37

One study reported similar hospitalisation rates between patients attending ED who had been directed to ‘immediate or prompt’ care and ‘non-urgent’ care: immediate or prompt: 38%(n=261), 95% CI 34 to 41 vs non-urgent: 37% (n=56), 95% CI 30 to 44).34 Another reported 15% (n=71) of paediatric cases attending ED after being triaged were admitted; of these, 37 had been advised to attend ED and 34 were given other lower urgency advice.37

Another study reported 15% (n=15) of patients given advice that was lower urgency than ED attendance, (such as urgent or routine GP appointment or self care), attended ED following their triage call and were admitted.27 One study reported 9.2% (n=30) of patients triaged as not requiring ambulance dispatch were subsequently admitted.27 36

One qualitative study described users reporting not having received appropriate triage advice for symptoms which later turned out to be more serious.44

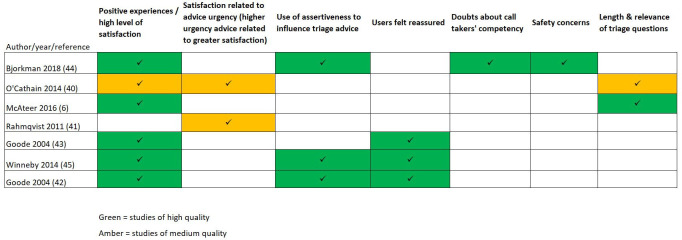

Service user experience

Seven studies focused on user experience and satisfaction.6 40–45 Three studies reported a high level of satisfaction among users.6 31 40 Two studies reported higher satisfaction among those who received higher urgency advice.40 41 Two studies reported dissatisfaction relating to the relevance and number of triage questions.6 40Three studies highlighted that callers felt they needed to be assertive in order to receive the expected care advice.42 44 45 For example, a user’s post to an online forum:

If you need help and advice you can always call the healthcare advice line, if you think they’re giving you the ‘wrong’ advice, tell them, and maybe you’ll get better help.44

Two studies reported that users felt that the nurses using digital triage gave them time, conducted ‘thorough’ assessments and felt reassured.43 45

In contrast, one study of users who posted to an online forum reported feeling scrutinised by the nurses questioning their symptoms and need for care.44 Some expressed doubts about nurses’ advice, competency and credibility.44

Integrated services made for a smoother patient care journey. One study based on an online forum described the experience of poor integration:

They send you to the ER where they yell at you for being stupid enough to listen to them (SHD). SHD is a big problem and seems to be at war with the ER.44

In contrast, there was high satisfaction in 71%, of users where the service provider was able to book an appointment at a local service on behalf of the patient.40

See figure 3 for a visual summary of findings across studies and table 2 for detailed findings.

Figure 3.

Key themes from studies of user experience.

Table 2.

Findings from studies that investigated user experience and satisfaction

| Author year Country Reference |

Study type | Sample/data size | Digital triage user | Participants | Key themes and example quotes |

| Björkman 2018 Sweden44 |

Descriptive research design using information from online forums using six step 'netnographic' method | Data from 3 Swedish online forums were purposively sampled. | Nurse | General population (users) | General satisfaction/attitudes ‘Where we are, the healthcare advice line is great, I’d rather call them than my primary care center’ Experience of call taker: Patients expressed doubts and mistrust on advice given and credibility of nurses. Feelings that nurses were not well competent/ qualified and relied on google: ‘And seriously, are they real nurses who take the calls at SHD? I almost think it sounds like they’re googling every question they get.’ Safety: Some concerns related to safety and feeling that advice given was not appropriate, for example: a user posted that they were advised to stay at home for a condition that turned out to be serious, ‘When you’re advised to take two paracetamols and go to bed. Not go into the ER. When I was feeling really bad, and called them and described my symptoms, that’s the exact advice I was given. The situation ended with my husband more or less forcing me into the car and driving me to the hospital. By then, my lips were purple and I was having trouble keeping my balance. Once there, they found that both my lungs were filled with 100 s of small blood clots.’ Assertiveness and negotiation: One user posted, ‘If you need help and advice you can always call the healthcare advice line, if you think they’re giving you the ‘wrong’ advice, tell them, and maybe you’ll get better help’ Service working together: a user expressed dissatisfaction where the service did not work well together, ‘There’s no point calling [digital triage service name]. They send you to the ER where they yell at you for being stupid enough to listen to them. [digital triage service name] is a big problem and seems to be at war with the ER’ |

| O'Cathain 2014 England40 |

Survey | Survey sent to 1200 patients from each of the 4 pilot sites studied, 1769 responded and were included for analysis | Non-clinical call handler | General population (users) | General satisfaction/attitudes Satisfaction levels were good overall (91% very satisfied or satisfied). 73% (1255/1726, 95%CI: 71% to 75%) were very satisfied with the way NHS 111 handled the whole process, 19% (319/1726) were fairly satisfied and 5% (79/1726) were dissatisfied. Two aspects of the service were less acceptable than others: 1) relevance of questions asked and 2) whether the advice given worked in practice. Greater satisfaction with higher urgency advice: Patients more likely to feel the service was helpful if directed to ambulance service (76%), compared with self-care(64%) visit health centre (55%), other service 54%, contact GP (52%). Services working together: Patients more likely to feel the service was helpful if an appointment was arranged for them (71%). |

| McAteer 2016 Scotland6 |

Other—mixed methods | Age-stratified and sex-stratified random sample of 256 adults from each of 14 Scottish GP surgeries, final sample was 1190 based on response rate with 601 of those having used the digital triage service. Purposive sampling used for interview group with total of 30 being interviewed. | Non-clinical call handler | General public (users and non-users) | General satisfaction/attitudes:

|

| Rahmqvist 2011 Sweden41 |

Survey | Random sample of 660 callers, made at one site in October 2008 | Nurse | General public (users) | Greater satisfaction with higher urgency advice Patients who were recommended to wait and see, were less likely to be satisfied and more likely to make an emergency visit or an on call doctor. Results reported in relation to callers' agreement with advice: analysed using 3 groups: (1) cases: those who disagreed with nurse advice and felt they needed higher level of care; (2) controls: those who disagreed with nurse advice or felt they needed higher level of care; (3) other callers. Average global patient satisfaction was significantly lower for nurses who served the cases compared with those who had not served the cases |

| Goode 2004 England43 |

Interview study | 60 interviews | Nurse | General public (users) |

General satisfaction/attitudes Results related to feelings that the digital triage service was 'trustworthy', and being able to access care without being a ‘nuisance’. Authors state that some interviewees experienced or predicted deterioration in service quality: ‘They’ll put a bit too much work on their call centres, they’ll be understaffed, then they’ll start becoming hurried or you’ll lose that friendly ‘take as long as you like’ sort of attitude that I experienced…’ Experience of call taker: reassurance Users felt reassured and cared for:

|

| Winneby 2014 Sweden45 |

Interview study | 8 semistructured interviews | Nurse | General public (users) |

Experience of call taker: feeling reassured when taken seriously The authors describe findings relating to users feeling reassured on follow-up care required, ‘When the nurse believed and advised them to turn to the care center on duty, having obtained a mandate to go there, gave them a sense of security’. A quote from a participant: ‘Because they [nurses] know more than I do and will refer me if it’s something serious.’ Assertiveness and negotiation ‘Being a nurse, I know what to say and what I’ve done at home. Otherwise they will tell you to ‘drink plenty of fluids’ and 'do this and that'. But now I say that ‘I have drunk a lot” and 'I have medication at home'. It feels as if they [SHD] try to sift out and turn away… you don’t call unless it’s necessary.’ |

| Goode 2004 England42 | Interview study | 10 interviews | Nurse |

General public

(users) interviews with men/or that related to men |

General satisfaction/attitudes

Assertiveness and negotiation One male participant made a follow up call to NHSDirect regarding his wife, while his wife was waiting for a call back from the service: ‘I simply had one aim at that point, which was to get a doctor out to the house without putting the phone down… everything was pretty much arranged in the one call. It was acknowledged that things were bad and that a doctor would be calling tonight… I guess I was being pretty direct, like, ‘She is sick and she must be seen.’ |

GP, general practice.

Discussion

This systematic review has evaluated the evidence on how telephone-based digital triage affects wider healthcare service use, clinical outcomes and user experience in urgent care. Thirty-one studies were included, covering a range of different designs, settings, populations and digital triage systems. Studies typically showed no change or a reduction in wider healthcare service use following the implementation of digital triage. They reported varied levels of caller adherence to the triage advice provided. There was very limited evidence on clinical outcomes; however four studies reported some findings on hospitalisation rates that highlighted potential safety concerns relating to under-triage.

Overall user satisfaction with telephone based digital triage appears to be high, but there was some evidence of poorer user experience relating to the length and relevance of triage questioning, and perceptions of ‘undertriage’. Users sometimes felt the need for assertiveness during calls when their expectations were not being met; however, this is unlikely to be specific to digital triage and has been reported in telephone-based consultation more widely.48

There was considerable heterogeneity across studies in terms of types of setting, types of participants, study designs and ‘digital triage’ systems. ‘Digital triage’ is a complex intervention with outcomes that may be influenced by multiple factors due to varying healthcare systems, local service configuration, staff training and an evolving landscape in the use of digital technologies to allow patients to seek urgent care, for example, through the use of digital self-triage tools. Hence, there needs to be caution in the interpretation of the applicability of findings. Additionally, strength of evidence differed between studies, as demonstrated by the visual tables of key findings; these differences fed into the narrative synthesis of this review.

Many of the studies that investigated service use following digital triage implementation reported no change in wider healthcare service use. In one context, for example, following the replacement of a nurse-led service with a non-clinician led service this may be seen as a success,38 but this may not be applicable to all healthcare settings. One study of ‘standalone’ digital triage implementation showed an increase in GP clinic use,30 which was in contrast to other studies in this review; this may be because this service was less embedded within the healthcare system, but could also have been a methodological consequence of using household surveys to gather service use data.30

Strengths and limitations

This is the first systematic review to focus on the use of telephone based digital triage in urgent care. It covered a 20-year period, during which some services have started to shift towards non-clinician-led models of service delivery. This review enabled evaluation of a broad range of service models and settings. However, it was limited to studies published in English, and this may have led to important evidence being overlooked.

This review used a comprehensive mixed-methods approach and evaluated quality of studies using the MMAT tool. While this tool worked well for many studies in this review, an acknowledged limitation49 is the applicability of its criteria for assessing studies that are cross-sectional in nature (where there are not necessarily defined groups with an intervention or exposure); this is applicable to some of the studies included in this review

There was limited evaluation of non-clinician led models of digital triage, with only one study evaluating service use following implementation and no studies of clinical outcomes. Another limitation is the scope of the included outcomes; outcomes relating to broad utilisation of services that use digital triage (such as call volumes, call lengths and caller characteristics alone), cost-effectiveness and staff focused outcomes were not covered.

While PPI did not directly feed into this review, this forms the first stage of a wider project investigating user outcomes related to digital triage. For the wider project, has been sought in the project design, and a panel has been selected to aid the interpretation of results and dissemination of findings.

Comparison with other literature

This review’s focus is narrower, in terms of intervention and setting, compared with previous reviews which evaluated telephone triage more broadly, including services that were not digitally supported.1 10 Bunn et al’s review evaluated telephone triage in comparison to usual care.10 They similarly reported no significant change in wider healthcare use (ED visits, routine GP visits and hospitalisations) associated with telephone triage. Other reviews found that user satisfaction is generally high when comparing telephone consultation with other forms of care,10 but lower satisfaction was described when patients’ initial expectations were not met.48

Our review highlights the limited evaluation of clinical outcomes. A previous review of telephone triage reported limited and inconclusive findings on mortality rates (with no mortalities occurring in some studies that sought to investigate this outcome), and rates of undertriage and subsequent hospitalisation ranging from 0.2% to 5.25%.1

Although our review did not include broad utilisation outcomes related to digital triage, a previous study reported lower than expected use by some ethnic minority groups.50 Our review found that no studies to date have reported on patterns of advice, user experience, service use or clinical outcomes in ethnic minority groups; this may have been limited by our exclusion of studies that were not published in English.

We found that patients’ adherence with advice varied by setting and study design. While very high adherence was reported in one survey based study,26 this may be an overestimate due to response bias in comparison to other studies that evaluated adherence based on routine data. Similar observations in higher adherence rates in self-reported service use were reported by two reviews.11 13

Implications for service delivery and future research

The review has identified several gaps in the literature, particularly a need for evaluation of patient level service use and clinical outcomes. Further analysis of large patient level datasets (particularly those that are linked with subsequent service use and clinical outcomes data) will help to gain a better understanding of who does and does not adhere to advice and help to evaluate safety concerns relating to under triage within particular patient subgroups.

In the absence of comparative studies, it is unclear how patient satisfaction and outcomes are affected by the design of services, the staff groups involved and how they are trained and managed, and the type of digital triage system deployed. Further evaluation of non-clinician led digital triage may help policy-makers and service commissioners to adopt the most efficient and safe digital triage systems.

While not a key aim, this review highlights that associations between factors (such as age, gender, ethnicity) and urgency of advice have not been explored in depth. The granular demographic and symptom data captured by digital triage tools gives opportunity to explore these associations which will likely provide insight into how services are used by different groups and form the basis for generating hypotheses within particular groups.

Many studies in this review were undertaken when digital triage was first being implemented. However, like any significant service change, digital triage services will take a significant period of time to become established and performing optimally within urgent care services that have been used to working in another way. To date, no studies have involved longitudinal data collection to evidence the extent to which this occurs. Longer-term evaluation studies are needed to explore how the safety and effectiveness of services changes over time. In addition, telephone-based approaches to seeking care have been critical during the COVID-19 pandemic and are likely to be more widely adopted in the long term51; therefore, evaluation of how these services have functioned during and after the pressures of a pandemic is also important.

Lastly, this review highlights limited qualitative and mixed-methods approaches to date. Integrating findings from routine data with qualitative research will help to better understand user experiences and care needs of particular patients groups in more depth. These could feed into targeted support for these groups within or outside of digital triage services, and ultimately improved delivery of these services which are key to a well functioning healthcare system.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Samantha Johnson (Academic Support Librarian, University of Warwick) for support with developing the search strategy. Patients and or public were not involved directly in the conduct of this review.

Footnotes

Twitter: @h_atherton

Contributors: VS developed the review protocol, with the support of HA and JD. VS conducted searches. VS, CB, ES and JWNB conducted screening, data extraction and quality assessment. VS conducted the narrative synthesis with support from CB and HA. HA and JD reviewed and revised manuscript and approved the final version. VS is the guarantor for the review.

Funding: This systematic review is part of a PhD that is funded through University of Warwick in collaboration with an industrial partner: Advanced (https://www.oneadvanced.com/).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information. Relevant data are included in online supplemental tables.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Huibers L, Smits M, Renaud V, et al. Safety of telephone triage in out-of-hours care: a systematic review. Scand J Prim Health Care 2011;29:198–209. 10.3109/02813432.2011.629150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tan S, Mays N. Impact of initiatives to improve access to, and choice of, primary and urgent care in the England: a systematic review. Health Policy 2014;118:304–15. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salisbury C, Coulter A. Urgent care and the patient. Emerg Med J 2010;27:181–2. 10.1136/emj.2009.073064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blakoe M, Gamst-Jensen H, von Euler-Chelpin M, et al. Sociodemographic and health-related determinants for making repeated calls to a medical helpline: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2019;9:e030173. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elliott AM, McAteer A, Heaney D, et al. Examining the role of Scotland's telephone advice service (NHS 24) for managing health in the community: analysis of routinely collected NHS 24 data. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007293. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McAteer A, Hannaford PC, Heaney D, et al. Investigating the public’s use of Scotland’s primary care telephone advice service (NHS 24): a population-based cross-sectional study. British Journal of General Practice 2016;66:e337–46. 10.3399/bjgp16X684409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Njeru JW, Damodaran S, North F, et al. Telephone triage utilization among patients with limited English proficiency. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:706. 10.1186/s12913-017-2651-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.North F, Varkey P, Laing B, et al. Are e-health web users looking for different symptom information than callers to triage centers? Telemed J E Health 2011;17:19–24. 10.1089/tmj.2010.0120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McKenzie R, Williamson M, Roberts R. Who uses the 'after hours GP helpline'? A profile of users of an after-hours primary care helpline. Aust Fam Physician 2016;45:313–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bunn F, Byrne G, Kendall S. The effects of telephone consultation and triage on healthcare use and patient satisfaction: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 2005;55:956. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blank L, Coster J, O'Cathain A, et al. The appropriateness of, and compliance with, telephone triage decisions: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. J Adv Nurs 2012;68:2610–21. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06052.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Randell R, Mitchell N, Dowding D, et al. Effects of computerized decision support systems on nursing performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review. J Health Serv Res Policy 2007;12:242–51. 10.1258/135581907782101543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carrasqueiro S, Oliveira M, Encarnação P. Evaluation of telephone triage and advice services: a systematic review on methods, metrics and results. Stud Health Technol Inform 2011;169:407–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sexton V, Dale J, Atherton H. An evaluation of service user experience, clinical outcomes and service use associated with urgent care services that utilise telephone-based digital triage: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev 2021;10:25. 10.1186/s13643-021-01576-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Methley AM, Campbell S, Chew-Graham C, et al. PICO, PICOS and spider: a comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:579. 10.1186/s12913-014-0579-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hong QN. 'Mixed methods appraisal tool' version, 2018. Available: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/page/24607821/FrontPage

- 18.Poyay J. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews, 2006. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Mark_Rodgers4/publication/233866356_Guidance_on_the_conduct_of_narrative_synthesis_in_systematic_reviews_A_product_from_the_ESRC_Methods_Programme/links/02e7e5231e8f3a6183000000/Guidance-on-the-conduct-of-narrative-synthesis-in-systematic-reviews-A-product-from-the-ESRC-Methods-Programme.pdf

- 19.North F, Muthu A, Varkey P. Differences between surrogate telephone triage calls in an adult population and self calls. J Telemed Telecare 2011;17:118–22. 10.1258/jtt.2010.100511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cook EJ, Randhawa G, Large S, et al. Young people's use of NHS direct: a national study of symptoms and outcome of calls for children aged 0-15. BMJ Open 2013;3:e004106. 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsu W-C, Bath PA, Large S, et al. Older people's use of NHS direct. Age Ageing 2011;40:335–40. 10.1093/ageing/afr018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.North F, Varkey P. How serious are the symptoms of callers to a telephone triage call centre? J Telemed Telecare 2010;16:383–8. 10.1258/jtt.2010.091016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Payne F, Jessopp L. Nhs direct: review of activity data for the first year of operation at one site. J Public Health Med 2001;23:155–8. 10.1093/pubmed/23.2.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jácome M, Rego N, Veiga P. Potential of a nurse telephone triage line to direct elderly to appropriate health care settings. J Nurs Manag 2019;27:1275–84. 10.1111/jonm.12809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zwaanswijk M, Nielen MMJ, Hek K, et al. Factors associated with variation in urgency of primary out-of-hours contacts in the Netherlands: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2015;5:e008421. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Byrne G, Morgan J, Kendall S, et al. A survey of NHS Direct callers’ use of health services and the interventions they received. PHC 2007;8:91–100. 10.1017/S1463423607000102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foster J, Jessopp L, Chakraborti S. Do callers to NHS direct follow the advice to attend an accident and emergency department? Emerg Med J 2003;20:285–8. 10.1136/emj.20.3.285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Munro J, Sampson F, Nicholl J. The impact of NHS direct on the demand for out-of-hours primary and emergency care. Br J Gen Pract 2005;55:790. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Munro J, Nicholl J, O'Cathain A, et al. Impact of NHS direct on demand for immediate care: observational study. BMJ 2000;321:150. 10.1136/bmj.321.7254.150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dunt D, Day SE, Kelaher M, et al. Impact of standalone and embedded telephone triage systems on after hours primary medical care service utilisation and mix in Australia. Aust New Zealand Health Policy 2005;2:30. 10.1186/1743-8462-2-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Turbitt E, Freed GL. Use of a telenursing triage service by Victorian parents attending the emergency department for their child's lower urgency condition. Emerg Med Australas 2015;27:558–62. 10.1111/1742-6723.12477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lattimer V, Sassi F, George S, et al. Cost analysis of nurse telephone consultation in out of hours primary care: evidence from a randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2000;320:1053–7. 10.1136/bmj.320.7241.1053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huibers L, Koetsenruijter J, Grol R, et al. Follow-Up after telephone consultations at out-of-hours primary care. J Am Board Fam Med 2013;26:373–9. 10.3122/jabfm.2013.04.120185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sprivulis P, Carey M, Rouse I. Compliance with advice and appropriateness of emergency presentation following contact with the HealthDirect telephone triage service. Emerg Med Australas 2004;16:35–40. 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2004.00538.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morimura N, Aruga T, Sakamoto T, et al. The impact of an emergency telephone consultation service on the use of ambulances in Tokyo. Emerg Med J 2011;28:64–70. 10.1136/emj.2009.073494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dale J, Higgins J, Williams S, et al. Computer assisted assessment and advice for "non-serious" 999 ambulance service callers: the potential impact on ambulance despatch. Emerg Med J 2003;20:178–83. 10.1136/emj.20.2.178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stewart B, Fairhurst R, Markland J, et al. Review of calls to NHS direct related to attendance in the paediatric emergency department. Emerg Med J 2006;23:911. 10.1136/emj.2006.039339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Turner J, O'Cathain A, Knowles E, et al. Impact of the urgent care telephone service NHS 111 pilot sites: a controlled before and after study. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003451. 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Siddiqui N, Greenfield D, Lawler A. Calling for confirmation, reassurance, and direction: investigating patient compliance after accessing a telephone triage advice service. Int J Health Plann Manage 2020;35:735–45. 10.1002/hpm.2934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O'Cathain A, Knowles E, Turner J, et al. Acceptability of NHS 111 the telephone service for urgent health care: cross sectional postal survey of users' views. Fam Pract 2014;31:193–200. 10.1093/fampra/cmt078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rahmqvist M, Ernesäter A, Holmström I. Triage and patient satisfaction among callers in Swedish computer-supported telephone advice nursing. J Telemed Telecare 2011;17:397–402. 10.1258/jtt.2011.110213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goode J, Hanlon G, Luff D, et al. Male callers to NHS direct: the assertive carer, the new DAD and the reluctant patient. Health 2004;8:311–28. 10.1177/1363459304043468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goode J, Greatbatch D, O’cathain A, et al. Risk and the responsible health consumer: the problematics of entitlement among callers to NHS direct. Crit Soc Policy 2004;24:210–32. 10.1177/0261018304041951 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Björkman A, Salzmann-Erikson M. The bidirectional mistrust: Callers’ online discussions about their experiences of using the national telephone advice service. Internet Research 2018;28:1336–50. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Winneby E, Flensner G, Rudolfsson G. Feeling rejected or invited: experiences of persons seeking care advice at the Swedish healthcare direct organization. Jpn J Nurs Sci 2014;11:87–93. 10.1111/jjns.12007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mark AL, Shepherd IDH. How has NHS direct changed primary care provision? J Telemed Telecare 2003;9 Suppl 1:S57–9. 10.1258/135763303322196367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ernesäter A, Engström M, Holmström I, et al. Incident reporting in nurse-led national telephone triage in Sweden: the reported errors reveal a pattern that needs to be broken. J Telemed Telecare 2010;16:243–7. 10.1258/jtt.2009.090813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lake R, Georgiou A, Li J, et al. The quality, safety and governance of telephone triage and advice services - an overview of evidence from systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:614. 10.1186/s12913-017-2564-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hong Q. Questions on the MMAT version, 2018. Available: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/page/71030694/FAQ

- 50.Cook EJ, Randhawa G, Large S, et al. Who uses NHS direct? investigating the impact of ethnicity on the uptake of telephone based healthcare. Int J Equity Health 2014;13:99. 10.1186/s12939-014-0099-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wosik J, Fudim M, Cameron B, et al. Telehealth transformation: COVID-19 and the rise of virtual care. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2020;27:957–62. 10.1093/jamia/ocaa067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-051569supp001.pdf (196KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-051569supp002.pdf (158KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-051569supp003.pdf (161.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-051569supp004.pdf (309.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-051569supp005.pdf (227.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-051569supp006.pdf (280.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-051569supp007.pdf (230.7KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information. Relevant data are included in online supplemental tables.