Abstract

Objective

To develop mid-range programme theory from perceptions and experiences of out-of-hours community palliative care, accounting for human factors design issues that might be influencing system performance for achieving desirable outcomes through quality improvement.

Setting

Community providers and users of out-of-hours palliative care.

Participants

17 stakeholders participated in a workshop event.

Design

In the UK, around 30% of people receiving palliative care have contact with out-of-hours services. Interactions between emotions, cognition, tasks, technology and behaviours must be considered to improve safety. After sharing experiences, participants were presented with analyses of 1072 National Reporting and Learning System incident reports. Discussion was orientated to consider priorities for change. Discussions were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by the study team. Event artefacts, for example, sticky notes, flip chart lists and participant notes, were retained for analysis. Two researchers independently identified context–mechanism–outcome configurations using realist approaches before studying the inter-relation of configurations to build a mid-range theory. This was critically appraised using an established human factors framework called Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS).

Results

Complex interacting configurations explain relational human-mediated outcomes where cycles of thought and behaviour are refined and replicated according to prior experiences. Five such configurations were identified: (1) prioritisation; (2) emotional labour; (3) complicated/complex systems; (4a) system inadequacies and (4b) differential attention and weighing of risks by organisations; (5) learning. Underpinning all these configurations was a sixth: (6a) trust and access to expertise; and (6b) isolation at night. By developing a mid-range programme theory, we have created a framework with international relevance for guiding quality improvement work in similar modern health systems.

Conclusions

Meta-cognition, emotional intelligence, and informal learning will either overcome system limitations or overwhelm system safeguards. Integration of human-centred co-design principles and informal learning theory into quality improvement may improve results.

Keywords: adult palliative care, organisation of health services, primary care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study design provided a safe space to integrate multiple perspectives on safety and improvement initiatives in palliative care.

Cross-disciplinary expertise has been combined with stakeholder experiences of frontline care to develop a new understanding of human factor issues in out-of-hours palliative care, and how these create mechanisms for desirable or undesirable outcomes.

Using the Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) framework in combination with realist approaches is a novel methodological development for cross-disciplinary analysis that has promise for future research.

Further work is needed to explore the issues raised and mid-range theory generated in other contexts, different cultures and with more people.

We were not able to address the issue of a false divide between out-of-hours and in-hours care in this study but this requires urgent attention as each impacts on the other.

Background

Palliative care seeks to improve the quality of life of patients and their families when they are facing challenges associated with life-threatening illness, whether physical, psychological, social or spiritual. Fragmented system design of out-of-hours palliative care heightens the risk of patient safety incidents.1 2 In a suboptimally designed system, human factors issues are exposed as people seek to work around, manage goal conflicts and resource constraints, and mitigate structural challenges ‘to get the job done’ as safely and efficiently as possible. The extent to which risk and well-being are impacted because of system-wide human factors issues in out-of-hours palliative care is unknown.

In the UK, out-of-hours healthcare provision is complex due to the many different professionals, organisations and systems involved.2 So-called ‘out-of-hours’ community healthcare services are responsible for providing care for two-thirds of the week (commonly 18:30–08:00 on weekdays, and all hours at weekends).2 Out-of-hours palliative care provision presents patient safety and professional performance challenges arising from both the nature of the care needs (which are often unstable and/or unpredictable, for example, medications required to achieve and maintain symptom control) and generic risks commonly found in out-of-hours care.1 2 The latter include problems with lack of prior knowledge about patients, reliance on remote consultations, lack of access to patient records and difficulties in service coordination.1 2 Electronic Palliative Care Coordination Records have been designed to provide a systematic approach to information needs but are not universally available nor fully functional in practice.3–5

Around 30% of people receiving palliative care in their usual place of residence in the UK have contact with out-of-hours services.6 Patients and families can struggle to identify who to contact out-of-hours and may feel they have to trade-off between speed of response and relevant service/expertise of responders.7 Most patients in the last phase of life are in their usual place of residence for the majority of their remaining time (home or care home).8 Access to services for most out-of-hours palliative care is via community/primary care and emergency services. Acute hospitals are the second most common place of care and most patients still die in hospital, with both numbers of deaths and the proportion occurring in hospitals projected to rise.9 10 Addressing out-of-hours challenges has been identified as a key priority by patients and palliative care organisations.11

In this study, we use the term ‘system’ to refer to the entirety of healthcare enterprise, that is, both the structural (in various disciplines referred to as field, architecture, artefacts) and the human. ‘Human factors’ is a scientific discipline that seeks to understand and optimise the interaction of people within the wider system in which they work.12 More specifically, human factors have been used to consider the direct and indirect (humanly mediated) impacts of sociotechnical systems (ie, systems intrinsically dependent on the interaction of human beings with structures, organisations and artefacts) and environments on safety, risk and well-being.12 The interactions between human emotion, cognition and behaviours and the influence of wider system elements have not, however, always been fully considered. This is essential to better understand how to design environments and structural systems to guide humans into the best course of action, while still maintaining allowances for necessary adaptions in performance to ‘get the job done’ given care complexities, goal conflicts and resource constraints. This is a priority for out-of-hours palliative care given the proportion of time covered by these services.

In previous work, National Health Service (NHS) palliative care-related patient safety incident reports stored on national databases were analysed for underlying contributing factors.1 2 These findings were presented to stakeholders in out-of-hours palliative care in a half-day research event which itself generated data for the current study. Separate analysis of the stakeholder event data, in this study, was conducted to further understand underlying desirable/wanted and undesirable/unwanted outcomes in community-based palliative care drawing on the concerns of those on the frontline. The study design was also situated in a wider quality improvement project, which aimed to improve out-of-hours palliative care across a South Wales Health Board.

Research question

Which human factors design issues are influencing system performance in out-of-hours community palliative care?

Objective

To develop mid-range programme theory from perceptions and experiences of out-of-hours community palliative care, accounting for human factors design issues that might be influencing system performance for achieving desirable outcomes through quality improvement.13

Methods

Theoretical orientation

Realist approaches seek to understand what works, for whom, under what circumstances and how, through the identification of context–mechanism–outcome (CMO) configurations.14 If outcomes (desired or not) are known, then analysis can trace back the mechanisms that led to those outcomes in particular contexts.15 Once CMO configurations are identified, these can be drawn together into a mid-range programme theory of practice. Mid-range theories are concepts that explain CMOs within an overarching theory of how a process functions to produce particular outcomes in different circumstances, that is, as underlying changes in reasoning and behaviour are triggered by different types or qualities of interaction or context.13 16

Mechanisms almost always operate on a continuum of activation rather than as a discrete dichotomous on/off. Mechanisms are components of whole systems, (incorporating both agency and structure), that intervene in or otherwise moderate, the relationship with other components. A mechanism’s functionality is dependent on combinations of human reasoning and available resource. When an intervention (such as a quality improvement initiative) is made, with the provision of additional or different resources then there is a complex interaction which occurs between resource, reasoning and context.17 This means that in an intervention, or routine clinical practice, the activities people engage in will be subject to individual and group choices, and these choices subject to social influences such as prior experience.

In this study, we apply realist approaches to the naturally occurring processes of routine clinical practice. Our initial (‘rough’) programme theory (ie, what might be producing outcomes from a complex system with diverse participants and how) was derived from our knowledge of the existing literature and prior work analysing NHS patient safety incident reports. The process of conducting the workshop and the data generated from it permitted us to refine this initial programme theory by identifying CMO configurations. In doing so, we have developed a mid-range theory, to explain what was happening and why. As with all mid-range theories, ours ‘lie[s] between the minor but necessary working hypotheses that evolve in abundance during day-to-day research and the all-inclusive systematic efforts to develop a unified theory’.18

After initially conducting an inductive data-driven analysis using the realist approach described above, and in more detail in the methods section below, we critically considered our analysis, including the developing mid-range theory, using a deductive approach to compare and contrast our findings with the perspective of the Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) framework.19 20 SEIPS is a well-established, multifunctional human factors framework that can be applied holistically to map research findings (in this case, CMO configurations) across predefined elements of healthcare (work) systems such as the person, task, technology, and organisational factors that typically interact and give rise to both wanted and unwanted care outcomes.

Setting

We wanted to use the learning from prior analyses of 1072 incident reports from the National Reporting and Learning System (NRLS) in England and Wales to inform improvement agendas for out-of-hours palliative care. The NRLS analysis itself was a separate study, also published2 which was used as a prompt to participants in this study. This study was set within the Aneurin Bevan University Health Board, one of the largest of the seven health boards in Wales, serving a population of 560 500 in South East Wales. In cooperation with the Board’s Palliative Care Strategy Group, a single stakeholder event (workshop format) was convened, combining our research objective, (ie, a mid-range programme theory of out-of-hours community palliative care) with local goals to develop quality improvement planning in this area.

The local goals were to:

Identify which issues in out-of-hours palliative care highlighted in national-level analyses of patient safety incident reports were prevalent in the local out-of-hours service (perceptions and experiences discussed also fed into our research objective).

Identify which of these issues should be the priority area for improvement efforts within local services (shared goal/objective).

Create an opportunity for participants to identify a local quality improvement project group (local goal, unpublished data, Williams. Study to Improve the Quality of Out of Hours palliative care services for out of hours patients. Grant: RCGP MC-06-16).21

In this paper, we present analysis related to our overarching research question and research objective for this study. The third local goal was not an objective of the research but something we wanted to support participants in, should they choose to do so.

Recruitment, selection and participation

Local providers and service users of out-of-hours palliative care were invited to participate in a stakeholder event via email. The palliative care network in South East Wales and Gwent Palliative Care Strategy Board agreed to facilitate this. Invitations were disseminated to the local palliative care network, out-of-hours General Practice (GP) providers, GP clusters and the local Research and Development office asking them to circulate details to their networks/membership. Further direct email invitations were sent by the study team to people in key roles including hospice providers, out-of-hours clinicians, palliative care consultants, GP leads and members of the public (including informal carers and patients). Potential participants were told they were being invited to a stakeholder event to identify priority areas in out-of-hours palliative care and that their participation would be used to inform a wider research programme. This led to a convenience sample of stakeholders who were engaged and interested in the subject. All those who chose to attend the stakeholder event provided written informed consent for this study. As we did not own the mailing lists used, we do not know the total number of people approached.

Patient and public involvement

Two informal carers attended the event in addition to the other stakeholders. Intrinsic to our methods is a collaborative approach as this study/the event was the mechanism for sharing prior research findings and seeking to bridge the gap between these and the experiences of all stakeholders in frontline clinical care.

Data generation

The event was approximately 6 hours long, with participants working in a mixture of small groups (five to six) and the whole group of 17. We drew on our prior experience of engagement exercises using quality improvement principles and tools22 to structure our dissemination of our previous analyses of safety incident reports during the event.

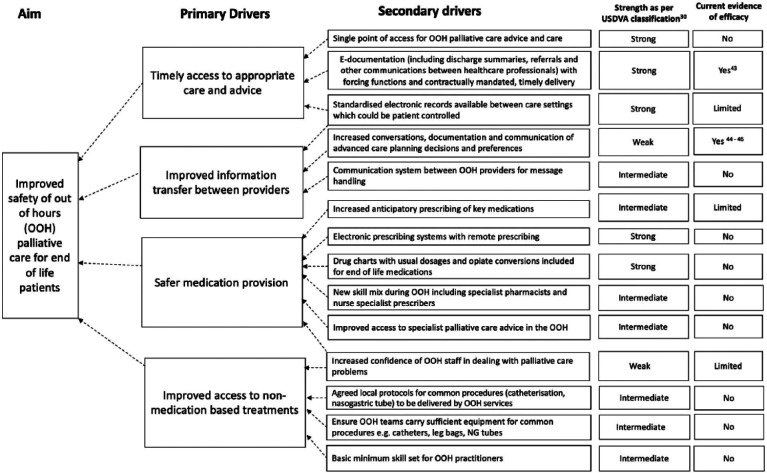

The stakeholder event was designed to first allow participants an opportunity to share and reflect on their experiences of out-of-hours provision of palliative care (‘Tell us what could have gone better in the last month while delivering palliative care in your role’). They were then provided with our analyses of incident reports (three examples used to provide stories behind a summary of incident types by severity of harm, contributory factors and patient outcomes). Event facilitators next worked with stakeholders to compare experiences with reported incidents and discuss potential priorities for change (‘which of the issues identified thus far should be a priority and why?’). The facilitators then shared a summary of existing literature for improvement (we presented initial ideas for change in the form of a driver diagram, see figure 1).2 Participants were next asked to expand on examples from recent experiences with a focus on potential solutions to identified problems; and decide which problems would be most important and feasible to tackle locally (‘What’s feasible in our service and why? Where next?’).

Figure 1.

Driver diagram to show potential interventions to improve the safety of out-of-hours primary care for patients at the end of life. Reproduced from: Williams et al.2

All event discussions were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by the study team. Participants were also invited to record challenges to the provision of good care and their priorities via sticky notes, flip chart lists and participant notes, and these were retained as data (hard copy plus photographs of collective arrangements (eg, group ordering of priorities) made during the event).

Data analysis

We focused analysis on understanding:

The context of out-of-hours community palliative care, and what occurs (mechanisms) to produce desirable outcomes; the intended global outcome of interest was for patients to receive the right care by the right person at the right time in the right place.

What mechanisms were operating in the same context to produce deviations from desirable outcomes, and what undesirable outcomes consequentially occurred.

First, HW and SY independently identified individual CMO configurations in data transcripts before comparing to reach a consensus of their line-by-line coding (using the framework of context, mechanisms and outcomes) and annotating these to form provisional configurations. This was refined with joint analysis of sticky notes and photographs of flip chart material plus handwritten field notes generated in the course of the stakeholder event. We then studied the inter-relation of the CMO configurations to identify themes and build a mid-range programme theory of the potential human factors design issues in out-of-hours palliative care.

Second, SY and PB led the critical comparison of our mid-range theory, built from CMO configurations with the SEIPS framework. This was achieved by reanalysing the raw data described above, notably complex themes and identified CMO configurations (simple, complicated and complex), to map all data to the SEIPS framework elements. This provided us with a second analytical lens from which to consider underlying contributing factors across the spectrum of CMO configurations.

Results

The roles of event participants are listed in table 1 below.

Table 1.

Participants in stakeholder event (n=17)

|

|

|

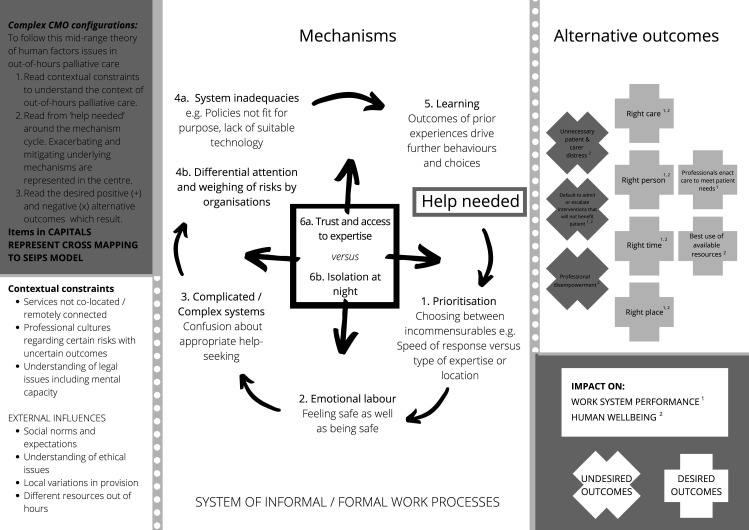

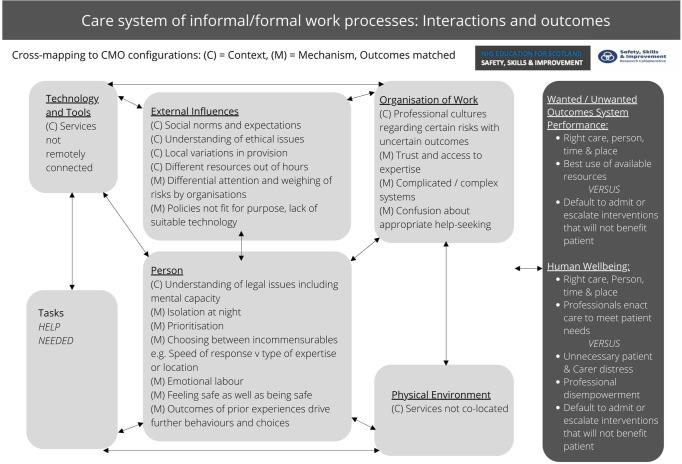

The outcomes of the CMO configurations identified in these data impact on both system performance and human well-being, demonstrating how it is not possible to disentangle these in out-of-hours palliative care. In summary, six CMO configurations that could be classified as simple/complicated (see table 2) were identified. In addition, six complex themes (see table 3) were identified and synthesised into the complex CMO configuration possibilities in figure 2. By definition, as these are complex, the resulting three contextual constraints, four external influences, six mechanisms (two of these subdivided into parts a and b) and nine alternative outcomes identified in figure 2 cannot be simplified into individual CMOs. However, tables 2 and 3 provide a summary of our analytical working as we developed the mid-range theory that is then presented in figure 2 and critically examined using SEIPS (figure 3). Underlying contributing factors, as well as mechanisms and outcomes, are classified using SEIPS. This is demonstrated in figure 3, and the right-hand columns of both tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Specific CMO configurations that might be amenable to simple or complicated interventions

| Context | Mechanisms | Outcomes | Interventions suggested to improve* | Exemplar quotations from stakeholder group to support the CMO configurations created | SEIPS mapping of mechanisms (subject-specific examples given in square brackets) |

| Multiple care providers | Different information technology systems Uncertainty about who to contact for what |

Lack of timely access to patient records Decisions made on incomplete information leading to suboptimal care |

Technological interfaces to improve access to live patient records in a timely manner need to be developed with a user-centred design approach Single point of access for out-of-hours care |

‘Most of the time we’ll get everything that we need from the out-of-hours General Practitioner (GP) but it’s adding that extra time, for both us, for the patient and for the out-of-hours GP you know. If we knew the information in the first place it would be a lot easier.’ (Professional) ‘What do carer’s want? And the answer is a single point of communication… don’t think it matters what the single point is but I do think it’s absolutely essential for a carer to have that phone number they can, they can ring and say help I don’t know the answer to this.’ (Informal carer) |

External influences [national policies] Organisation of work Technology and tools |

| Advance care planning (ACP) | Plans not created Plans not communicated/accessible when needed Unclear who is responsible for completing and updating advance care plans Lack of effective processes and tools for care coordination between hospital and community |

Optimal care in line with patient preferences not delivered Deviations from preferred place of care or death Admissions to acute healthcare when patient not going to benefit from escalation in treatment interventions |

Interpersonal solutions accounting for socially mediated factors to prompt advance care planning creation Technological interfaces to improve access to live patient records in a timely manner across all services including hospitals |

‘We looked at the volume of 999 to care homes pre ACPs and post ACPs and there’s a definite reduction it caused. ACPs are empowering care homes nurses to not make that phone call.’ (Professional) ‘How do you keep that up to date when we’ve got an electronic system that’s–but there’s lots of different electronic systems that we’re supposed to be putting the information on’ (Professional) ‘Because he’s not ambulant he can’t go through the usual turn up to clinic so he has to get brought in by ambulance so he has to go through the medical intake he’s there waiting you know for hours and hours and hours for that, then they do the Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) and they admit him through the process check his DVT–no, but then it took 3½ weeks to get him home, discharge planning all he came in for was a DVT to be ruled out and but the fact is he’s now in hospital unsafe discharge, la, la, la, la, la, you know everyone wanted him to be at home, he wanted to be at home, but the minute we ticked this system box of get him in we can’t get him out then.’ (Professional) |

Organisation of work Technology and tools Person [including dynamics between people–patient/informal carers/healthcare professionals; and, psychological, social and cognitive factors] Physical environment |

| Workload pressures due to volume of need in comparison with staff resources | Professionals focusing on crisis management Tendency to leave complex issues to ‘in-hours’ care providers |

Further crises due to lack of preventative/prophylactic measures Agency staff used–lack of local knowledge disadvantaging them in providing best care |

Population-based needs assessment of resources to deliver agreed standards of care | ‘What we do is we normalise a lot of it we just say it’s part of our working day to go around correcting all the mistakes that the system has put in.’ (Professional) ‘How much extra work these mistakes cause us and literally every you know about a third of these is that somebody else has actually caused so yes we’ve had to do the extra paperwork. So, it builds inefficiency into our systems.’ (Professional) ‘Actually, we could chuck in agency staff… absolutely yeah and that’s above their paid rate you know.’ (Professional) |

Organisation of work Person [healthcare professionals—physical, cognitive and psychological capabilities] |

| Reliance on professionals outside specialist palliative care to deliver frontline services | Inexperience Lack of training Uncertainty about how to gain expert advice/advice not available |

Default to admit patients to hospital Missed or delayed diagnosis of palliative care emergencies, for example, bowel obstruction, pathological fractures |

Additional specialist palliative care resources for direct patient care and/or training of others in frontline care: population-based needs assessments could guide quantification of this. Robust concurrent evaluations of effectiveness, and value of additional resources and new training interventions | ‘We might have breathing difficulties… well breathing difficulties can be so many things so we’ve got to walk in and we’ve got to, we’ve got to determine first of all you know is this a reversible cause, you know is this an asthma, is this a chest infection or is it palliative care you know so…and then once we’ve decided okay perhaps it is palliative care, we don’t know at what stage.’ (Professional) ‘You’ve got the GP who doesn’t know the patient, they turn up its gonna take a lot more time to sort them out locally, it’s easier to get them admitted.’ (Professional) |

Organisation of work Person [healthcare professionals: team working, psychological and cognitive factors] |

| Medication management | Complicated medication regimes Unfamiliarity of frontline staff with palliative care medications Myths and fears about symptom control medications Breakdown of practical systems for prescribing, supplying and administering medications |

Delays in symptom control Increased risk of medication errors: wrong doses prescribed, dispensed or administered |

End-to-end solutions for medication provision and management, for example, electronic prescribing, clarity about who could prescribe/alter dosing of existing medications/transcribe prescriptions Out-of-hours pharmacy support Increased anticipatory prescribing |

‘I saw people going out of hospital with complicated treatments regimes that gave the feeling that I don’t think there’s a chance in a million of those people taking the right drugs at the right time.‘ (Informal carer) ‘Tell me if I’m speaking out of turn, I think in the community out-of-hours GP’s, Primary care, some people are afraid of it and they’ll only prescribe it [oral morphine instant release liquid] every 4 hours whereas we didn’t have a problem in giving them every hour.’ (Professional) ‘And then when there’s artificial barriers put up so when for instance we can’t get the drugs in the community even if you call on-call pharmacy it’s really difficult to get the medicine from say the hospital because it’s a community patient and they want a hospital prescription and it’s always things like that it’s like an artificial barrier that’s put up for accessing the meds.’ (Professional) ‘We used to have dose ranges which were stopped so we would have 2.5–10 mg of midazolam written up but once that’s stopped the GP then writes 2.5 mg 2 hourly, but if that patient then overnight an hour later is in excruciating pain the qualified nurses there can’t give anything, can’t take a verbal, has to wait for out-of-hours then to come which could take X, Y-10 [participant indicating problems of this taking an unknown length of time] you know or however long, so that can be quite frustrating.’ (Professional) |

Organisation of work Person [patient, informal carers, healthcare professionals: physical, psychological and cognitive factors] |

| Implicit reliance on informal carers | Inadequate support | Carer distress and breakdown | Investment in carer support: psychological, emotional and practical Adequate needs-based assessment of patient care |

‘I had a patient admitted a week last Friday who was in renal failure end of life, he preferred basically a death at his home we rang out-of-hours at quarter to eleven they arrived at 2am patient was severely agitated with retention of urine potentially they gave a stat that they didn’t catheterise patient an hour later became very, very agitated GP couldn’t go out the wife panicked and then rang 999 he was then admitted and died so… I think if the reassurance that somebody was gonna go back, maybe the GP could visit then she may not have panicked and rung 999. However, she could’ve also rung me back, but she didn’t so it was a very sad situation really, because he was obviously extremely agitated, but he dipped very quickly… People react differently overnight as they might do during the day really don’t they? They often say long hours at night they see things differently, in the day there would’ve been a lot more people around… we see a lot of out-of-hours calls where people panic and ring 999 even though you’ve put everything in place.’ (Professional) ‘I was confused, my wife running a really high temperature with her being tired because I thought they visited on the weekend I didn’t take her temperature quite as often as I should.’ (Informal carer) ‘And I had a promise of support from Marie Curie which was very good for my peace of mind.’ (Informal carer) |

Organisation of work Person [patient, informal carers: physical, social, psychological and cognitive factors] |

*As demonstrated in figure 1, evidence to support these is variable: we report here the suggestions made during the stakeholder event. Our analysis demonstrated professional belief in these interventions regardless of the level of empirical evidence.

ACP, advance care planning; CMO, context–mechanism–outcome; SEIPS, Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety.

Table 3.

Complex person-level themes leading to interacting mechanisms that influence human factors issues in out-of-hours palliative care

| Themes | Exemplar quotations to support themes identified | SEIPS mapping |

| Frontline professionals commonly feared that the consequences of not admitting a patient to hospital or escalating investigations or disease-focused treatment would be personal blame | ‘For the carer one of the critical questions is how will I know when they are actually about to die? Or what will I see, what will actually happen? And some cancers some conditions will manifest themselves in different ways, so for instance if I were to anticipate …I wouldn’t want to manage that and that could be …and coping afterwards you know, because that would be very stressful… but I don’t when people talk about preferred place of care they go into the A—the options, or that the hospitals sort’ve of thing or B—what each one then can offer, still so that they’re aware.’ (Professional) ‘One area with clinical practice which has changed dramatically in the last 24 months is sepsis and it’s not included in the advanced care plan it’s gonna happen that you become sceptic and everyone is now saying that and in out-of-hours cos I’ve seen in happen oh well if they become septic well their preferred place of care is at home but when they’re sceptic—call an ambulance.’ (Professional) |

Person (healthcare professionals: emotional intelligence, meta-cognition, workplace culture, learning from prior experiences) |

| Patients and informal carers were reported to be regularly facing an impossible choice due to enormous differentials in the speed of response times of different services, that is, people were choosing between having any professional present quickly over having someone with the right expertise. Who was called by patients and informal carers was also shaped by previous experiences of who was most likely to respond. | ‘We have a lot of calls because it’s quicker to get through to us than it is we have I mean we’ve worked our 8 hours that day so we’re doing an on-call and then doing another 8 hours literally we’re working solid through for 2 days and we have many calls at 3am, 5am you know because we’re quicker and that’s not a good thing is it at all?’ (Professional) | Person (patients and informal carers: psychological, cognitive and social factors) |

| Neither patients/informal carers nor professionals felt safe or supported to take calculated risks in line with patient priorities for care in the community | There’s a lady who’d had a severe stroke who was actually bed-bound for about 4 years Do Not Attempt Resuscitation (DNAR) end of life drugs, she was deteriorating, we sent a driver up, he [patient’s informal carer] still rang 999 and there was no way on earth that lady of ever being moved, she was hoist only, and she died in the ambulance—it’s unavoidable on times isn’t it?’ (Professional) | Person (patients, informal carers and healthcare professionals: psychological factors and learning from prior experiences) |

| The lack of pre-existing relationships between professionals within and across out-of-hours services meant there was a lack of trust, which in turn impinged on professional autonomy, giving and receiving advice, and lack of understanding of practical constraint on each other’s working practices | ‘It took a couple of hours for someone from out-of-hours to see them, we were going that’s good! It’s pretty damn good that 2 hours, but you know it all depends what the family were expecting and actually 2 hours, I’m dialling 999 cos no one’s coming I’m on my own I don’t know what’s going on, they’re looking terrible… So there’s an issue of knowing what carer’s needs are and what their expectations are, and actually whether we’re able to meet them because otherwise the default will be 999. There were some issues around kind’ve expertise and knowledge and skills I don’t think it was a big as one of the other issues and the other final one which I suppose is around equipment 2 major issues were around catheters, simple as that, someone with terminal agitation where a catheter would’ve sorted it, for various reasons it wasn’t, and another where a patient had, had a catheter, it had come out at their request and then when it needed to go back in because it had been put in by frailty the Distrinct Nursing (DN) service, there wasn’t a catheter pack, so they couldn’t do it. So once again, different systems not, not connecting…’ (Professional) | Person (healthcare professionals: psychological and social factors in team working) |

| Apart from some doctors, professionals were uncertain of their authority to act on discussions around ceilings of care even in the presence of documented advance care plans, in part due to different policies and guidance in different organisations. | ‘We had a 40 year old lady who we’d discharged from nursing home who had a detailed advanced care plan and they still admitted her at 8 o’clock in the morning you know we just sat and managed then to turn her around the following day and get her back out. So that was really disappointing because she could’ve died on route or what have you, fortunately she made it back to the home it was all the distress around that so there’s communication there around the nursing home and skills of the nursing staff and I think the knowledge and the understanding of the detail around the advanced care plan because when we looked into that they were saying oh we not everybody realised that the detail of that and therefore you know somebody like you say has probably panicked and thought oh my god we just need to send her in you know she was a little bit more short of breath, that was potentially imminently dying and it was just all very unfortunate.’ (Professional) ‘And that’s gone to the NMC (Nursing and Midwifery Council) saying why didn’t you start it? And she said well he was obviously dead it was not DNAR you have to go in and jump on his chest you cannot make that decision to say to stop it has to be a doctor.’ (Professional) |

Person (healthcare professionals: meta-cognition, lack of empowerment, workplace cultures, learning from prior experiences) |

| Many professionals lacked understanding of the law regarding mental capacity and advance care planning and viewed ‘doing something’ as being by definition more defensible than what they perceived to be ‘doing nothing’ even though the latter was often in fact not nothing but taking action to provide appropriate symptom control and basic care | ‘Because they’ll say oh yeah we’ve got a DNAR, but it doesn’t mean to say that they’re not gonna be actively treated up to the point of arrest and the number of times when you’re saying to people in nursing homes well are they for admission or are they treatment within their home? And they can’t answer you most of the time and they’re making calls in the middle of the night to relatives to ask then do you want them to go in or not? But we can’t take that as a legal requirement because we, because nobody’s had the discussion properly and put it in writing, so some of it is to do with the advanced planning really. It seems to be lacking…so by the time our GP’s or our nurses are coming in the middle of the night you’ve got to follow with what’s before you and half of the times when I’ve driven like say and I don’t want to send this person in, but there is nothing there to stop me.’ (Professional) ‘The COPD’s [Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, COPD] and the dementia’s and things like that, because the disease trajectory is difficult to work out you can have somebody who’s had a DNAR and they are in place for 4 years but it’s never been updated and therefore how can you make a decision on something that was put on 4 years ago. If it’s not been updated on an electronic system or anything.’ (Professional) |

Person (healthcare professionals: cognitive and psychological factors) |

SEIPS, Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety.

Figure 2.

Complex CMO configurations. CMO, context–mechanism–outcome; SEIPS, Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety.

Figure 3.

Care system of informal/formal work processes: interactions and outcomes. Carayon et al.19

Simple situations are defined by identification of straightforward solutions if necessary skills and techniques are mastered. In complicated situations, an identifiable set of linked solution components which interact in predictable ways can still lead to definite outcomes.23 As described above, during our analysis, it became evident that with exception of relatively few specific instances (provided in table 2), it was not possible to disentangle independent simple, or even complicated, CMO configurations. Instead, the analysis pointed to interacting complex CMO configurations as possible explanations for relational and experience-based human-mediated mechanisms and outcomes (table 3 and figure 3).

Therefore, we first present the few simple and complicated CMO configurations that might be most amenable to technical/structural system change, gaining of skills or techniques for tasks or other component-by-component interventions in table 2. This table demonstrates that contextual factors such as multiple care providers, including informal carers within a specialist-generalist advisory model where advance care planning was not well established, triggered system breakdowns which were considered by participants in the stakeholder event to be amendable to systems-based change. Technological solutions and greater investment in care coordination services such as a single point of access/medication management models in tandem with greater public health assessment of population need were all anticipated to offer improvements. Hence, it can be seen from table 2 that structural solutions are likely to provide part, but not all, of the solution particularly if human factors issues are taken into consideration in any redesign.

However, as indicated above, what we were identifying in most of the data was complex with several significant and concerning underlying themes contributing to multiple human-mediated mechanisms. The themes are presented in table 3, with illustrative quotations from participants to demonstrate how these themes are supported by analysis of the raw data. Together these themes were identified to be influencing outcomes which were produced by mechanisms that co-evolved through interpersonal relationships. Such mechanisms could not be explained by a straightforward analysis of parts. Furthermore, the outcomes and subsequent consequences resulting were both unpredictable and yet what mattered most.23

Our overarching interpretive analysis, bringing together the underlying themes and complex CMOs, is presented in figure 2 (our mid-range theory). The interconnected mechanisms interact to form a system with adaptive capacity to change from experience as mediated by the people within it, and their experiential learning. At any point, the mechanisms might come together to either overcome system limitations (a ‘desirable’ outcome) or to overwhelm system safeguards (an ‘undesired’ outcome).

In figure 2, for each of the outcomes and mechanisms described, all the contextual elements listed were relevant. The themes of table 3 also underpin all these complex CMO configurations. The context of out-of-hours palliative care was one where multiple service providers are disconnected from each other, and so misunderstanding and miscommunication could occur very easily in addition to different professional cultures developing regarding risk and uncertain outcomes.

The mechanisms numbered 1–5 ((1) prioritisation; (2) emotional labour; (3) complicated/complex systems; (4a) system inadequacies and (4b) differential attention and weighing of risks by organisations; (5) learning) within figure 2 all feed into and off each other. Underlying these mechanisms could be either ‘trust and access to expertise (6a)’ which if strong enough could lead to desired outcomes in support of, or regardless of, mechanisms 1–5 through a positive cycle or ‘isolation at night (6b)’ which could lead to the opposite effects and hence undesirable outcomes. ‘Trust and access to expertise (6a)’ is, therefore, ‘interpersonal glue’ that can stick the component parts together to reach desired outcomes. We have labelled 6a and 6b as such as these are components on a continuum.

The data suggest that seeking to focus on specific parts of these complex CMO configurations in isolation is unlikely to be successful. What needs to be generated is a positive cycle of learning with attention to all the underlying themes and interacting human-mediated mechanisms identified. Depending on how human factors-based systems issues interact and function in a particular patient’s care, there are alternative desirable or undesirable outcomes for patients that are intertwined with the same for professionals. When patients, informal carers or professionals seek help, they are commonly weighing up priorities between speed of response and ability to meet a particular need. Emotional labour is a significant mechanism. Being safe in a technical sense does not hold meaning if patients, informal carers, or professionals do not feel safe in their location, decision-making, or actions. Furthermore, both prioritisation and emotional labour mechanisms feed into confusion about whom to call for what and when. Mechanisms driven by organisational interests or system inadequacies which do not support, for example, individualised decision-making or use of professional judgement when in a situation that requires doing the ‘least wrong’ thing are unhelpful.

In out-of-hours palliative care, if trust is achieved and access to expertise is available, then desired outcomes can be achieved; but if instead the underlying mechanism is a sense of personal or professional isolation, undesirable outcomes result. The most common undesirable outcomes identified were unnecessary patient and carer distress, defaulting to admitting patients to acute hospital care and/or escalation of treatment interventions from which there was not a realistic possibility of patient benefit and professional disempowerment—all of which would feed back into the mechanism cycle by triggering adverse learning that in turn would influence future help-seeking approaches. Positive learning could, however, be created by achieving desired outcomes, as could best use of available resources, both in turn leading to human factors supporting the system.

In mapping the identified CMO configurations to the SEIPS model (figure 3), it is possible to see more clearly how little of the complex person-level concerns from stakeholders regarding out-of-hours palliative care directly relate exclusively to technical factors. Instead, the inter-relationships between social and technical factors warrant greater attention to optimise the system. External influences, organisation of work and person elements come to the fore, demonstrating what is filling design gaps in a system which has evolved piecemeal over time, with a striking absence of identified mechanisms related to human factors-based design issues at individual, team, organisation and external levels. Furthermore, while it is possible to map relatively simple and complicated mechanisms (table 2) to SEIPS elements, other than the person level this is not the case with the complex interacting mechanisms that are influencing broader system interaction issues and related performance and well-being outcomes (table 3).

Discussion

Our work demonstrates that optimal care is dependent on ‘interpersonal glue’: often mediated by trust, empowerment and ability to tell whether a situation demands a standardised, customised or flexible response. This study contributes to the existing literature on three fronts: methodology and theory-building; human factors issues; and safety in out-of-hours palliative care. The key messages and recommendations for each are summarised in table 4.

Table 4.

Key messages and recommendations

| Methodology and theory-building There is value in drawing on different perspectives and frameworks to explore the nature of problems before attempting to offer potential solutions. |

Sharing findings from analysis of patient safety incident reports directly with stakeholders is an effective prompt for discussing gaps between official accounts and day-to-day experiences. Synthesis of complementary approaches (eg, the realist context–mechanism–outcome model with SEIPS) helps cross disciplinary boundaries and consider intersectionality between different perspectives. |

| Human factors issues Interventions can only be targeted at underlying mechanisms driving human factors issues when problems are studied in depth and in context. |

As people experience different events, socially constructed learning in the form of sense-making, or meaning-making occurs leading to cycles of thought and behaviour that are refined and replicated according to experiences in future events. It is relatively rare that addressing knowledge gaps alone will make a difference in complex situations. Better integration of human-centred co-design principles and informal learning theory into future attempts at improvement are needed to increase the likelihood of success. |

| Safety in out-of-hours palliative care Problems are created, defined and constructed by people in ways that generate variable patient outcomes, experiential learning (desirable or otherwise) and consequences for future healthcare. |

Optimal care is dependent on ‘interpersonal glue’: often mediated by trust, empowerment and ability to tell whether a situation demands a standardised, customised or flexible response. Optimal care and a holistic approach to safety in palliative care are seen to commonly require in-the-moment enacting of workaround strategies to manage risk in complex and adverse conditions. |

SEIPS, Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety.

We have drawn on realist and human factors theory to interpret the reality of day-to-day experiences of patients, informal carers and professionals as they are active agents in patient safety endeavours in out-of-hours palliative care. In doing so, we demonstrate a small number of CMO configurations that may be amenable to structural change but more importantly why structural change alone will seldom be enough to ensure patients receive the right care by the right person at the right time in the right place. Our findings show human factors issues go beyond how people interact with each other and with their surroundings or immediate environment. As people experience different events, socially constructed learning in the form of sense-making or meaning-making occurs leading to cycles of thought and behaviour that are refined and replicated according to experiences in future events.

In demonstrating complexity, it is important to note that this means different approaches to the planning and testing of improvement interventions will be needed. Simple and complicated solutions can only take us so far. We suggest that better integration of human-centred co-design principles,24 a fundamental approach of human factors and informal learning theory into future attempts at improvement are needed to increase the likelihood of success. This is because our findings demonstrate that optimal care is dependent on ‘interpersonal glue’: often mediated by trust, empowerment and ability to tell whether a situation demands a standardised, customised or flexible response.25 Optimal care and a holistic approach to safety in palliative care are seen to commonly require in-the-moment enacting of workaround strategies to manage risk in complex and adverse conditions.26–29 Our findings provide evidence of not just what the problems are but how these are created, defined and constructed by people in ways that generate variable patient outcomes, experiential learning (desirable or otherwise) and consequences for future healthcare. Our data provide a basis for selecting targeted interventions to influence the social mechanisms underlying safety issues in out-of-hours care.30

This extends previous work analysing patient safety incident reports1 2 31 by deepening analysis of the human factors interaction issues which are an intrinsic part of the complexity of palliative care work in the community.24 As a result, we propose a mid-range programme theory of the influences on human factors in response to palliative care needs out-of-hours. This can be used to guide future attempts to improve the design of care processes through recognition of implicit assumptions and rationales,13 thereby increasing the chances of mitigating undesirable mechanisms and promoting desirable ones. Doing so should help to create meaningful change for patients and increase professionals’ chance of success as they endeavour to provide safe care in difficult circumstances. We have already applied this mid-range programme theory to our later analysis of incidents arising from advance care planning.31 This identified structure-based solutions to ensure patients receive timely and robust advance care planning would not be enough; in 37% (26 of 70) of advance care planning incidents, the plan was not followed due to person-level issues such as poor higher-level meta-cognitive skills or emotional intelligence often in the context of lack of confidence or experience.

Strengths and limitations

SEIPS is one of the most widely used human factors frameworks in healthcare,20 22 and the use of realist approaches in healthcare has grown significantly in recent decades. Using both to develop a cross-disciplinary analysis to theory and empirical data is, we believe, a novel methodological development. In doing so, we have been better placed to consider intersectionality between human factors issues and structural elements in the context of a healthcare system. Our explicit use of realist principles in concert with SEIPS provided us with the analytical means to consider multiple dimensions operating as interacting mechanisms in the real-world experiences of stakeholders. In doing so, we have illuminated the space where structure meets agency, developing a mid-range programme theory through complex CMO configurations.13 Although our data are drawn from the UK, by developing a mid-range programme theory and integrating SEIPS, we have created a framework that is of international relevance through its potential to guide quality improvement work in similar modern health systems. Using our theory will help ensure attention is paid to both agency and structure in system (re)design. Nevertheless, the end product from this work results in a theoretical framework which requires further refinement and testing through application in different contexts, and with different people across differing systems and cultures.

While the use of the driver diagram (figure 1) created in our prior work remains a useful tool for organisations to evaluate their own local context, the addition of this study is to provide a similar contextualised framework for digging deeper into socially constructed concerns which may help or hinder process-based and task-based interventions seeking better outcomes. This study used analyses of data summarised as driver diagrams as prompts to engage stakeholders in structured discussions that would help us better understand the differences between what happens ‘on paper’ and in reported incidents (knowing these are likely to be the tip of an iceberg) and what happens in day-to-day practice. It is not enough to consider out-of-hours palliative care to be a series of task-based processes. Professionals and patients/informal carers alike base choices and behaviours on ‘grander’ socially influenced learning from prior experiences and constructions of roles, responsibilities and accountability. We suggest that our approach is a helpful method for creating safe spaces to promote voices to build a richer and more meaningful construct of the challenges which need to be addressed through improvement initiatives.32

The study team included GPs (HW, AC-S, AE) and palliative medicine consultants (SN, SY) with interests in realist methodological, educational and sociocultural expertise. In addition, the study team had expertise in human ergonomics (PB) and patient safety (AC-S, LD). The stakeholder event also provided a starting point for a local quality improvement project in South East Wales (unpublished data, Williams. A Study to Improve the Quality of Out of Hours palliative care services for out-of-hours patients. RCGP MC-06-16). In this way, we sought to create local impact alongside our research objectives.13 We are aware, however, that our research data are necessarily contextualised and hence further work exploring the issues raised and theories generated in other contexts is needed. For example, we note the limited diversity of our participants. It is also worth noting that out-of-hours both makes up the majority of time in any given week, and what happens in-hours is bound to impact on out-of-hours care. Rethinking systems from a patient and informal carer perspective is needed to shift from considering in-hours and out-of-hours as two distinct entities. Addressing this issue was outside the remit of our current study.

Implications for policy, practice and further research

We do not claim our programme theory to be more than mid-range and accept that it is based on a relatively small sample of people. It is not intended to be a definitive explanation of all out-of-hours palliative care, rather we anticipate its usefulness being in providing a framework to guide quality improvement work that integrates person-level and other human factors-based systems thinking principles.33 We expect, for example, this will help to support future attempts to improve out-of-hours palliative care, thereby increasing the likelihood of meaningful constructive change. This is because our mid-range theory highlights areas that are often overlooked in whole systems redesign. Throughout our work, we accept that the meaning people derive from experiences influences future learning and actions.34 Human agency inherently risks unintended and unanticipated consequences of actions as people seek to adapt to changing circumstances. Practical experience creates informal knowledge of how work can be done. There are often gaps between work-as-imagined (ie, designed and necessarily schematic) and work-as-done (ie, on the ground practice).35 As we identified, a sense of isolation experienced in out-of-hours work exacerbates these challenges and is an underlying mechanism driving all the other CMO configurations. Addressing this through systems that facilitate ready access to expertise and interpersonal trust instead should be a priority.

Less attention has perhaps been given in healthcare improvement to work-as-reimagined, that is how those on the ground learn informally to get work done, or not, based on prior experience, including when structural elements of a system are suboptimal. It remains the case that there is a lack of empirical evidence to support many improvement interventions in out-of-hours palliative care that professionals believe in. In many instances, this is due to an absence of high-quality studies rather than evidence against interventions. There is also a lack of human factors-based studies exploring system-wide complexities and adaptations that facilitate or inhibit good quality care. Further work is needed to support the design and redesign of improvement interventions to better suit the people in the system and develop meaningful ways for impact (effectiveness, efficiency and value as well as patient benefit) to be assessed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank: (1) Professor Joyce Kenkre, University of South Wales, for her support of HW in gaining Fellowship funding which subsequently allowed this study to be undertaken and for supporting his Fellowship work in addition to her helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper; (2) Angela Watkins, PRIME Centre Wales, for her assistance with the creation of figures 2 and 3.

Footnotes

Twitter: @simonnoble

Contributors: The study team included GPs (HW, AC-S, AE) and palliative medicine consultants (SN, SY) with interests in realist methodological, educational and sociocultural expertise. In addition, the study team had expertise in human ergonomics (PB) and patient safety (AC-S, LD). All authors were involved in the conception and design of the work in addition to all authors contributing to the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of the data. HW and SN attended the event with HW facilitating and ensuring accurate data collection. SY led the analysis with HW (both independently identifying individual CMO configurations). SY drafted the first version of the full manuscript with input from AC-S and PB. SY and PB led the critical comparison of our mid-range theory with the SEIPS framework by reanalysing the raw data, identified CMO configurations and themes during a cross-matching and mapping exercise using the SEIPS framework. All authors provided critical revisions and their own expertise to reach the final synthesis and interpretation. All authors agreed the final version. ACS is guarantor for the study.

Funding: The authors gratefully acknowledge the Royal College of General Practitioners Marie Curie Palliative Care Research Fellowship to enable the team to carry out this research.

Competing interests: AC-S was senior mentor to HW as recipient of a Royal College of General Practitioners Marie Curie Palliative Care Fellowship. No competing interests to declare for other authors.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

No data are available. We are not able to provide the raw dataset for this study to other parties because it is not possible to sufficiently anonymise the data to protect the identity of our participants. We are willing to discuss and provide further details of our methodological approach on request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and ethical approval was granted from Wales Research Ethics Committee 3 (17/WA/0222). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Yardley I, Yardley S, Williams H, et al. Patient safety in palliative care: a mixed-methods study of reports to a national database of serious incidents. Palliat Med 2018;32:1353–62. 10.1177/0269216318776846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams H, Donaldson SL, Noble S, et al. Quality improvement priorities for safer out-of-hours palliative care: lessons from a mixed-methods analysis of a national incident-reporting database. Palliat Med 2019;33:346–56. 10.1177/0269216318817692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petrova M, Riley J, Abel J, et al. Crash course in EPaCCS (electronic palliative care coordination systems): 8 years of successes and failures in patient data sharing to learn from. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2018;8:447–55. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2015-001059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wye L, Lasseter G, Simmonds B, et al. Electronic palliative care coordinating systems (EPaCCS) may not facilitate home deaths: a mixed methods evaluation of end of life care in two English counties. J Res Nurs 2016;21:96–107. 10.1177/1744987116628922 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Millares Martin P. Electronic palliative care coordination system (EPaCCS): Interoperability is a problem. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2018;8:358–9. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2017-001396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brettell R, Fisher R, Hunt H, et al. What proportion of patients at the end of life contact out-of-hours primary care? A data linkage study in Oxfordshire. BMJ Open 2018;8:e020244. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karasouli E, Munday D, Bailey C, et al. Qualitative critical incident study of patients’ experiences leading to emergency hospital admission with advanced respiratory illness. BMJ Open 2016;6:e009030. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calanzani N. Local preferences and place of death in regions within England 2010. London: Cicely Saunders international, 2011. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/34a3/4db13024a72307e16c3c95b6c9c723299a72.Pdf [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gomes B, Higginson IJ. Where people die (1974-2030): past trends, future projections and implications for care. Palliat Med 2008;22:33–41. 10.1177/0269216307084606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beynon T, Gomes B, Murtagh FEM, et al. How common are palliative care needs among older people who die in the emergency department? Emerg Med J 2011;28:491–5. 10.1136/emj.2009.090019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Best S, Tate T, Noble B, et al. Research priority setting in palliative and end of life care: the James Lind alliance approach consulting patients, carers and clinicians. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2015;5:102 10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000838.3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chartered Institute of Ergonomics & Human Factors . What is ergonomics? Find out how it makes life better. Available: https://www.ergonomics.org.uk/Public/Resources/What_is_Ergonomics_.aspx

- 13.Davidoff F, Dixon-Woods M, Leviton L, et al. Demystifying theory and its use in improvement. BMJ Qual Saf 2015;24:228–38. 10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pawson R, Tilley N. Realistic evaluation. London: SAGE, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong G, Westhorp G, Manzano A, et al. RAMESES II reporting standards for realist evaluations. BMC Med 2016;14:96. 10.1186/s12916-016-0643-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, et al. Realist methods in medical education research: what are they and what can they contribute? Med Educ 2012;46:89–96. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04045.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dalkin SM, Greenhalgh J, Jones D, et al. What’s in a mechanism? Development of a key concept in realist evaluation. Implement Sci 2015;10:49. 10.1186/s13012-015-0237-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merton RK. On sociological theories of the middle range. In: Merton RK, ed. On theoretical sociology: five essays, old and new. New York, NY: Free Press, 1967: 39–72. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carayon P, Schoofs Hundt A, Karsh B-T, et al. Work system design for patient safety: the SEIPS model. Qual Saf Health Care 2006;15:i50–8. 10.1136/qshc.2005.015842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holden RJ, Carayon P, Gurses AP, et al. SEIPS 2.0: a human factors framework for studying and improving the work of healthcare professionals and patients. Ergonomics 2013;56:1669–86. 10.1080/00140139.2013.838643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naughton J, Williams H. Gleeson A2 Rekindling primary carers’ relationship with advance care planning: a quality improvement project. BMJ Supp Palliat Care 2019;9:A1. [Google Scholar]

- 22.NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement . The handbook of quality and service improvement tools. 2010. London: NHS Institute for innovation and improvement. Available: http://www.miltonkeynesccg.nhs.uk/resources/uploads/files/NHS%20III%20Handbook%20serviceimprove.pdf

- 23.Yardley S. Editorial. Palliat Med 2018;32:1039–41. 10.1177/0269216318771239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schuler D, Namioka A. Participatory design: principles and practices. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paul B. Getting more health from healthcare: quality improvement must acknowledge patient coproduction—an essay by Paul Batalden. BMJ 2018;362:k3617. 10.1136/bmj.k3617 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vincent C, Amalberti R. Safer healthcare, strategies for the real world. New York, NY: Springer International Publishing, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collier A, Phillips JL, Iedema R. The meaning of home at the end of life: a video-reflexive ethnography study. Palliat Med 2015;29:695–702. 10.1177/0269216315575677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lang A, Toon L, Cohen SR, et al. Client, caregiver, and provider perspectives of safety in palliative home care: a mixed method design. Saf Health 2015;1:3. 10.1186/2056-5917-1-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sampson C, Finlay I, Byrne A, et al. The practice of palliative care from the perspective of patients and carers. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2014;4:291–8. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2013-000551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin G, Ozieranski P, Leslie M, et al. How not to waste a crisis: a qualitative study of problem definition and its consequences in three hospitals. J Health Serv Res Policy 2019;24:145–54. 10.1177/1355819619828403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dinnen T, Williams H, Yardley S, et al. Patient safety incidents in advance care planning for serious illness: a mixed-methods analysis. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2019. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2019-001824. [Epub ahead of print: 28 Aug 2019]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dixon-Woods M, Campbell A, Martin G, et al. Improving employee voice about transgressive or disruptive behavior: a case study. Acad Med 2019;94:579–85. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McNab D, McKay J, Shorrock S, et al. Development and application of 'systems thinking' principles for quality improvement. BMJ Open Qual 2020;9:e000714. 10.1136/bmjoq-2019-000714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mezirow JD. Learning as transformation: critical perspectives on a theory in progress. 1st edn. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anderson JE, Ross AJ, Jaye P. Modelling Resilience and Researching the Gap between Work-as-Imagined and Work—as-done. In: Braithwaite J, Wears RL, Hollnagel E, eds. Resilient health care, volume 3: reconciling work-as-imagined and work-as-done. Florida: CRC Press, 2016: 133–42. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No data are available. We are not able to provide the raw dataset for this study to other parties because it is not possible to sufficiently anonymise the data to protect the identity of our participants. We are willing to discuss and provide further details of our methodological approach on request.