Abstract

Introduction:

Although cervical cancer is preventable, it is a major gynecological disorder among women currently. More than 500,000 new cases of cervical cancer are being diagnosed across the globe, with one woman dying of cervical cancer every 2 min. In addition, about half of cervical cancer survivors have challenges with their sexual function. Despite these findings, literature regarding the sexual function of women with cervical cancer is scanty. The study aims to assess cervical cancer’s impact on the sexual and physical health of women diagnosed with cervical cancer in Ghana.

Methods:

The researchers of this study employed a qualitative approach with phenomenological design. A purposive sampling technique was used to select 30 participants engaged in face-to-face in-depth interviews that were audio-recorded. The content of the transcripts was analyzed using content analysis.

Results:

This study revealed that cervical cancer patients experienced low libido due to the cervical cancer symptoms and the side effects of chemotherapy. This low libido made them divert their sexual gratification from the vagina to other centers of the body. Findings further revealed that some participants showed apathy toward their partners’ sexual feelings. Some physical problems experienced by the participants were also unraveled.

Conclusion:

Cervical cancer affects all aspects of a woman’s health, including sexual function and physical well-being. Therefore, there is the need for more to help address challenges faced by cervical cancer women about their sexual and physical health.

Keywords: cervical cancer, impact, phenomenological study, physical health, sexual health

Introduction

Even though cervical cancer is preventable, it is currently a major gynecological disorder among women.1,2 More than 500,000 new cases of cervical cancer are being diagnosed across the globe, with one woman dying of cervical cancer every 2 min. 1 The cervix plays a significant role in reproduction and human sexuality. 3 Sexual health is an integral part of human life, and when compromised, it causes psychological discomfort. 4 However, some researchers have discovered that most needs of women with cervical cancer are unmet, of which sexual health is included. 5 About half of cervical cancer survivors have challenges with their sexual function. 4 However, it was identified by some authors that studies focusing on the quality of life among women who have cervical cancer were scarce. 6

Cervical cancer, malignancy of the cervix, is reported to be preventable and curable if detected early. 7 Researchers have identified that women with cervical cancer, though may be asymptomatic at the initial stages of the disease, present with the following clinical manifestations at the advanced stages: bleeding in between menses, post-menopausal bleeding, and foul-smelling vaginal discharge.7–9 Human Papilloma Virus is the main organism detected to be associated with cervical cancer. 10 Other risk factors linked to cervical cancer are multiple sexual partners and early onset of sexual activity since it is found to spread through sexual intercourse. Cervical cancer can be prevented through screening and treated with chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgery or combination of the various therapies. 11 Some authors have reported that treatment choice is based on several factors including the stage of cancer, involvement of lymph node, other co-existing chronic diseases, and the probability of it reoccurring. 10 Apart from the complications resulting from cervical cancer, and despite the increased survival rates associated with the treatment, researchers have ascertained that several side effects have also been linked to cervical cancer treatment such as depression, anxiety, hair loss, and fatigue.12,13 Moreover, treatment of cervical cancer including chemotherapy and radiation therapy may alter the sexual life of women affected. 4

In addition, some researchers believe that most women suffer lasting sexual dysfunction after cervical cancer treatment. 14 The stigma and discrimination attached to sexually dysfunctional individuals highly predispose cervical cancer patients to impaired social life. 15 In addition, it was asserted that the sexual dysfunction experienced by these women predisposes them to reduced sexual enjoyment and psychological stress. 16 The sexual problems found in patients with cancer are attributed to chemotherapy and radiotherapy effects, causing most patients to opt for surgical intervention to maintain their sexual activities. 17 It has also been established that some women with cancer undergoing treatment experience infertility. 18

Moreover, a study among 30 cervical cancer survivors established that most participants reported sexual inactivity and dysfunctions. 19 In addition, multiple urine leakage was a worry to about two-thirds of the study participants. Other cervical cancer treatment side effects reported were loss of libido, vagina dryness, and pain during intercourse. Consequently, low sexual drive and loss of interest in sex were significant problems of cervical cancer survivors.20,21 Other examples of sexual dysfunction included pain during intercourse (32.9%), altered sexual life (25.9%), and vaginal stenosis (75.2%). Sexual dysfunction among cervical cancer survivors was associated with increased depression among women affected. 22 Also, cervical cancer patients with impaired sexual function have a poor quality of life compared with those with normal sexual life.23,24

Cervical cancer patients suffer several physical changes including loss of hair, weight loss, skin itching, and loss of self-esteem among others due to chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Although some people may be cured, the immediate and later effects of any form of the therapy essentially impair the quality of life of these patients. 25 In addition, women receiving chemotherapy and radiation therapy have been found to have challenges with their nutritional status due to the effects of the treatment and some food restrictions. Also, another side effect of chemotherapy is stomatitis, which may result in poor feeding and subsequent malnutrition.26–28

In Kenya, a study conducted among 419 cervical cancer patients found that 20.3% of participants reported being stigmatized by the families and their community members. 29 Cervical cancer is often stigmatized in Brazil, and women affected find it difficult to endure the stigmatization. 30 In Ghana, it has been established that cervical cancer patients suffer pain, vaginal bleeding, immobility due to fear of soiling themselves in public, and loss of sleep. 31 They also experience loss of hope, anxiety, and fear of death after the diagnosis.

Apart from the sexual dysfunction, most cervical cancer patients experience numerous physical symptoms. Cervical cancer treatment is associated with several physical challenges, including pain, fatigue, impaired sleep and rest, fertility issues, and functional inactivities. 32 More than half of the patients (61.88%) with cervical cancer in India reported pain, and it remains the most troublesome symptom of cervical cancer patients. 33 According to some researchers, cervical cancer brings about activity limitations among ambulatory women due to pain. 34 According to researchers in Indonesia, most cervical cancer patients suffer severe discomfort caused by pain (67.8%) and are associated with anxiety/depression (57.5%). 35

In Ghana, it was reported that cervical cancer women need to be given regular injection to reduce pain severity. 31 In a study to determine the prevalence of pain in cervical cancer patients in Nigeria, 73.8% out of 210 patients interviewed experienced excruciating pain which predisposed them to depression and anxiety. 36

Methods

Research design

Research method is the process that researchers follow to conduct their research. The design of the research also refers to the framework that guides researchers. 37 The research design guides the collection of data and data analysis. 38 The research design adopted by the researchers of this study was a qualitative approach using a phenomenological design. A qualitative method was selected because it allowed respondents to share their sexual life experiences following a cervical cancer diagnosis. The population targeted in this study were women diagnosed with cervical cancer and receiving treatment at the largest public health facility in Ghana.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Women diagnosed with cervical cancer receiving various forms of curative treatments or palliation, who have lived with the cervical cancer diagnosis for over a year, and who are willing to participate in the study were included in this study. Participants who were severely ill (unconscious or on life-supporting machines) or emotionally disturbed (depressed) and those who could not speak TWI or English, which the researchers understand, were exempted from the study.

Sampling technique and sampling size

Purposive sampling technique was used to select participants who met all the inclusion criteria and were capable of giving appropriate responses for the data analysis. The sample size was determined by data saturation. Hence, the researchers kept including and interviewing participants until the participants were repeating the same responses. The sample size for this study was reached at 30.

Instrument for data collection

Data from the participants of this study were collected using a semi-structured interview as a guide. The tool consisted of open-ended questions with probes designed by the researchers related to the study objectives and literature of the phenomena under study. The subsections were the demographic data, sexual well-being of participants, and participants’ physical well-being. The semi-structured interview guide was pretested in participants with cervical cancer at a private hospital in Ghana. This pilot study helped in the revision of the data collection tool to ensure its credibility.

Data collection procedure

Ethical clearance was granted by an Institutional Review Board in Ghana with the ethical clearance number (DHRCIRB 158/11/20). The ethical clearance letter and an introductory letter were sent to the administration of the study setting to seek their permission to enter the facility. In-charges of the units used were made aware of the study, and their permission were sought before using the patients on their wards. Participants who met the inclusion criteria were recruited after establishing a rapport with them, explaining the purpose of the study, and seeking their consent. They were also made to sign a consent form before interviewing them. Face-to-face semi-structured interviews were conducted between the participants and the researchers at a private place of participants’ choice. Interviews were conducted in English based on the participants’ preferences since all the participants could speak and understand English. Each of the face-to-face interviews lasted for 50 min to 1 h, and the entire interview lasted for a period of 6 weeks. Participants’ permission was sought before recording the interviews using audio recorders. Field notes were written in addition to the recordings where necessary.

Rigor

Methodological rigor is the process of ensuring trustworthiness of a qualitative study. 39 The process of ensuring that the study’s conclusions are accurate and transparent is known as trustworthiness. Rigor has four components, according to Guba and Lincoln: credibility, transferability, confirmability, and dependability. 40 To maintain the trustworthiness of this study, the topic was carefully selected with the aim of the study in mind. The study was strictly guided by the purpose and the objectives of the study; the design and technique used for selecting participants as well as the sample size and data collection procedure were described to allow replication of the study in other settings. The data collection tool was also formulated based on the objectives and pretested to ensure its credibility before using it for the data collection.

Data analysis

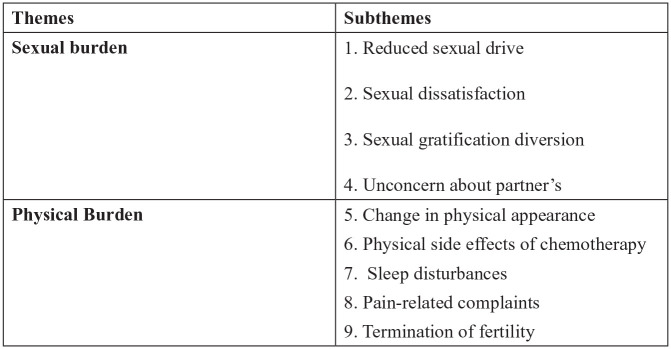

After transcribing all the data, the researchers analyzed the transcripts using content analysis to make them more meaningful, unambiguous, and concise. The purpose of the content analysis in qualitative studies aims to attain a condensed and broad description of the phenomenon and use categories to describe the phenomenon. 41 This involves five processes: familiarization with the data, dividing text into several meaningful units, condensing the unit (reducing the words while maintaining the meaning), formulating codes, developing categories, and finally forming themes. This was done by the researchers reading the transcripts multiple times to understand the data collected. Following this, the units were shortened into smaller words with similar meanings to the larger units. The smaller units were further reduced to few words, not more than four, termed as codes. The codes were then put together to form categories. This was later used to generate themes and subthemes as illustrated in Table 1. Also, COREQ software was used in reporting the qualitative data.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic data of participants.

| Identity | Age | Location | Religion | Educational status | Employment | Marital status | No. of children | No. of years with C.C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 43 | Koforidua-Tafo | Muslim | Never | Trader | Married | 4 | 5 |

| P2 | 65 | Tamale | Muslim | Tertiary | Retired teacher | Married | 7 | 1 |

| P3 | 79 | Daboase-enyirim | Christian | Never | Unemployed | Widow | 3 | 1 |

| P4 | 72 | Winneba | Christian | Tertiary | Caterer | Married | 4 | 4 |

| P5 | 60 | Awudome | Christian | Tertiary | Retired banker | Divorce | 2 | 5 |

| P6 | 44 | Dzorwulu | Christian | Secondary | Trader | Married | 3 | 3 |

| P7 | 48 | Dansoman | Christian | Tertiary | Constructor | Married | 0 | 1 |

| P8 | 45 | Madina | Christian | Secondary | Hairdresser | Married | 4 | 5 |

| P9 | 29 | Nungua | Christian | Secondary | Trader | Married | 4 | 2 |

| P10 | 57 | Mamprobi | Muslim | Secondary | Trader | Married | 5 | 6 |

| P11 | 77 | Ashaiman | Christian | Never | Unemployed | Married | 5 | 10 |

| P12 | 65 | Abokobi | Christian | Tertiary | Retired teacher | Divorce | 5 | 2 |

| P13 | 70 | Nungua | Christian | Tertiary | Trader | Widow | 8 | 3 |

| P14 | 73 | Maamobi | Christian | Secondary | Seamstress | Married | 4 | 4 |

| P15 | 43 | Teshie | Muslim | Primary | Trader | Married | 2 | 3 |

| P16 | 52 | Ashaley botwe | Christian | Secondary | Trader | Married | 5 | 4 |

| P17 | 56 | Lapaz | Christian | Secondary | Cleaner | Married | 3 | 2 |

| P18 | 61 | Nima | Muslim | Tertiary | Trader | Married | 6 | 2 |

| P19 | 58 | Larteh | Christian | Secondary | Trader | Married | 4 | 6 |

| P20 | 48 | Adenta | Christian | Secondary | Trader | Married | 2 | 3 |

| P21 | 54 | Assin Fosu | Christian | Elementary | Trader | Married | 2 | 2 |

| P22 | 56 | Akim Oda | Christian | Never | Farmer | Widow | 2 | 1 |

| P23 | 45 | Sogakope | Christian | Secondary | Trader | Married | 4 | 2 |

| P24 | 40 | Kasoa | Christian | Tertiary | Nurse | Married | 3 | 1 |

| P25 | 35 | Dodowa | Christian | Primary | Trader | Married | 3 | 2 |

| P26 | 67 | Sakumono | Muslim | Secondary | Unemployed | Married | 4 | 2 |

| P27 | 70 | Mampong | Christian | Primary | Unemployed | Widow | 3 | 4 |

| P28 | 58 | Labadi | Muslim | Secondary | Trader | Married | 5 | 3 |

| P29 | 38 | Teshie | Christian | Secondary | Hairdresser | Married | 2 | 2 |

| P30 | 45 | East Legon | Christian | Primary | Unemployed | Married | 4 | 3 |

Results

Socio-demographic characteristic of the participants

The majority of the participants, 24 (80%), were married; four were widowed; and the rest were separated. The majority of the participants, 26 (86.6%), were employed but could not go to work because of their diagnosis. Participants had lived with their diagnosis for a year and over. The rest of the data is illustrated in Table 1.

Organization of themes

Two main themes and nine subthemes emerged from the data analysis, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Themes and subthemes.

Sexual functions of cervical cancer patients

Sexuality is an important part of who we are as humans. Beyond the ability to reproduce, sexuality defines how we see ourselves and physically relate to others. Adequate sexual relation in marriage strengthens the bond between the couples. Unfortunately, cervical cancer patients’ sexual desire was impaired as a result of the symptoms experienced. From the data collected, cervical cancer patients expressed having challenges in relation to their sexual functions. The subthemes derived from this construct are as follows:

Reduced sexual drive

Sexual dissatisfaction

Sexual gratification diversion

Unconcerned about partner’s sexual life

Reduced sexual drive and sexual dissatisfaction

The majority of participants, especially those with advanced cases of cervical cancer, cited low libido due to reduced sensitivity to the sexual act. One of the significant sexual organs for females, that is, the vagina, is highly affected with abnormal offensive discharges and bleeding, preventing majority of the participants from availing themselves for sexual intercourse. Moreover, some participants reported having little/no feelings for sexual activities due to the psychological trauma they were experiencing.

I am having offensive discharge through my vagina, I cannot present myself for any sexual intercourse and my husband understand me. Due to the discharge, I was not thinking about any sexual act because of unhygienic state of the vagina. (P25)

Before the cancer I could meet my husband about 4–5 times in a week but now I can only sleep with him ones or twice in a week which I am not okay with that, but I have no option than to manage. (P11)

Left for me alone, I will not have any intercourse again because of the pains and the discharges. The feelings is not there but I have to please my husband. (P11)

Some participants attributed their sexual dissatisfaction to severe pain and vaginal bleeding they experienced during intercourse which caused them to reduce the number of times they permitted their husbands to have sex with them.

Initially, I tried to bear with the pain during sex. However, as times goes on, I could no longer bear the pain so I had to tell him to stop. Since 2 months now I have not had sex with my husband. (P4)

I was not interested in having sex because I was bleeding for several months through my vagina. But I am happy my husband understood the situation. (P20)

Few participants also narrated that their husbands do not enjoy the sexual act they have after the condition.

I could feel that my husband does not exhibit the kind of feeling he used to have when we had sex before my condition, sometimes he stop having the sex even before orgasm when he sees me crying. (P19)

Sexual gratification diversion

Some participants of the study shifted their usual sexual gratification to other parts of the body instead of vaginal penetration. According to them, breast sucking is one of the ways they attained their sexual pleasure due to challenges associated with their condition.

This was exhibited in the following narrations:

Now I cannot bear with the pains during intercourse so what I do when I feel for sex is to allow my husband to play with my breast and suck it for me especially my nipples so that I feel relieved (laugh). (P9)

My husband does not have sex with me often as he used to but has resorted to kissing as many times as he can within a day. Kissing and touching is my major means of attaining my sexual pleasure now. (P22)

You can see that I am very busty (big breast) so my husband at times have intercourse in between my breast. I also play with his manhood at times but I don’t allow him to penetrate my vagina now because it is very painful. (P11)

Unconcern about partner’s sexual life

It was deduced from the data collected that as these women’s sexual drive became impaired, some were less concerned about their partner’s sexual feelings. This impaired the smooth relationship that existed between them and their partners. This comment was made by participants who were severely affected by cervical cancer.

I cannot engage in any sexual act in this state. Am having discharges and feeling severe pain for about three weeks now and I have no desire to engage in sex. My husband can only bear with me at this difficult moment if not he should find other alternative, it is up to him. (P19)

If am well I will give him good sex no matter how he wants it. I am currently not well and am dying how can I be thinking about my husband’s sexual feelings. I cannot kill myself for my husband to have sexual feelings. (P17)

Few of the women were suspicious of their husbands cheating on them due to their state.

For three months, I have not been able to have sex with my husband, and he is not complaining; I am not bothered because you know men will always get it elsewhere. I guess that is why he does not complain. (P3)

Physical burden of cervical cancer patients

Physical well-being refers to performing physical activities and carrying out social roles that are not hindered by physical limitations. Cervical cancer brings numerous physical challenges to women affected. It ranges from loss of body organs to deformed structures, especially in a metastasized woman. These physical effects are attributed to side effects of chemotherapy and the destruction of body cells by metastasized cancer cells. This theme contains all the physical side effects of chemotherapy and the symptoms of cervical cancer.

Change in physical appearance

Cervical cancer causes physical changes in patients during the advanced stages. Hence, some participants in this study revealed that they had noticed a noticeable change in their physical appearance. The data of this study revealed that some participants’ physical appearance has deteriorated. On the field note taken, the participants looked very emaciated and weak on the bed.

I have been bleeding for over a week now, and I have lost much blood. You can even see that I am looking pale, this has made me very weak and loss weight. (P1)

I have not been able to eat well for about three weeks now, I am also feeling pains and discharging clots of blood from my vagina. In a day I can bleed about three hand full of blood. This is not my normal stature, have really reduced weight. (P17)

I think I am losing weight because I am not able to sleep well at night nowadays. This is because the pain gets severe during the night which prevent me from sleeping. (P9)

Sleep disturbances

This study indicated that participants had difficulty sleeping at night. Participants described their sleep patterns as poor. The poor sleep reported by the participants was linked to severe pains and vaginal bleeding, hence keeping them awake throughout the night.

I was not able to sleep well because of the severe pains experienced. When the pain comes, I have to take medication and the pain reduces but after little time I feel the pains again. This has been happening to me for about 1 month now hence the need for my admission. (P10)

For about 2 months now I am not able to have adequate sleep because I feel so much pain both throughout the day and the night. (P30)

Few participants were not able to sleep due to severe vaginal bleeding.

I do not have enough sleep because I have to wake up and change my pad. I am bleeding heavily and if I don’t change my pad it will get wet and smelling on me. In a night I can wake up like 2–3 times to change my pad and after changing, I am able to sleep easily again, and that has affected my sleep patterns. (P22)

The diagnosis of cervical cancer has brought much anxiety to the participants, interrupting their sleeping patterns.

The diagnosis of cervical cancer has caused me to think and that has affected my sleep. The maximum hour that I sleep is 2 hours in the night. Previously I used to sleep for about 6–8 hours and if I wake up, I feel. (P20)

I always have that fear that I will die because my condition is deteriorating, due to that I have not been able to sleep well for about 3 months now. (P27)

Physical side effects of chemotherapy

Although the cancer drugs are given to manage cancer, prevent its progression, and relieve suffering, its side effects are very numerous and have a toll on the participants. Almost all the participants reported several side effects they experienced after beginning their chemotherapy. Among the side effects experienced, vomiting was the most common side effect reported by the participants.

I vomited the first day I took the drug, I felt very weak and drowsy and that day I could not do anything and this continued for about two weeks. (P6)

I vomited several times upon taking the drug, and I could not continue with that drug. I came back to the hospital and asked the doctor to change my drugs for me because I was vomiting continuously and became very weak but he explained to me that they are normal side effects of the drugs and he prescribed other drugs to help prevent the vomiting. (P9)

Few participants experienced a loss of appetite after taking the drug.

When I started the medication, for about 2 weeks I could not feel for food because I was having nausea. I could not even eat my favorite food which is rice with kontomire stew. Sometimes, even if I want to eat the food, it taste bitter so I just have to stop eating. (P5)

Some participants had diarrhea after taking the cervical cancer medications.

When I took the drug, I had diarrhea for 1 week. In a day, I could visit the toilet for about 5–7 times. I became weak because I was losing a lot of fluid and sometimes I soil myself with feces if I don’t get to the washroom early. (P26)

Since I started taking this medication, my elimination patterns has changed. Sometimes, the stools will be coming unaware and it is very watery. There are times I have to rush to the washroom when the urges come. (P11)

Other participants described their experiences with hair loss as follows:

When I started the medication, the nurses told me that one of the side effects of the chemotherapy is hair loss. Three weeks after I started the medication, I realized that when I comb the hair, a lot of the hair removed. Hmmm, now I have to cover my head whenever am going out and to prevent people from staring at me and to look presentable. (P20)

I decided not to comb my hair on frequent bases to avoid further hair loss. Now I always have to put on wigs to look a bit better in public. I think that will prevent friends from asking lots of questions about the hair loss. (P8)

A participant who had chemotherapy 2 months ago reported,

Even though I lost my hair few weeks after the treatment, the hair started coming back after some weeks when I completed it. And it is looking nicer now as you can see. (P15)

Few participants had infection due to low white blood cell (WBC) count caused by chemotherapy.

For these 3 years that I was placed on chemotherapy, I have been treating mouth sore almost every 4 months. (P21)

About six months after I was placed on chemotherapy, I was experiencing severe itching inside my vagina. During my following review I complained to the doctor and she told me that it was vagina infection and could be side effects of the chemotherapy. (P14)

Pain-related complaints

The majority of participants in the study experienced pain during activities like sexual intercourse and sometimes while walking. Pain is felt inside the vagina and radiates to the waist as well as the abdomen. Some participants narrated,

I feel severe pain during sexual intercourse. The pains almost like a woman in labor who is about to deliver. Sometimes, it feel like a pepper put in a wound. I did bear with the pain but it is severe I had to tell my husband to stop because am feeling pain. I would rate the pain as 7 out of 10 on pain assessment scale. (P15)

The more I engage in activities the more I feel the pain in my groin. For that matter, I could not do anything proper. (P6)

Few participants reported that their pain was unresponsive to pain medications.

Initially, I was feeling the pain, I went to the pharmacy and bought tablet Paracetamol and took but the pain still persisted. I further bought tramadol which reduced the pain but the pain was felt later after few hours so the pain has been on and off even with the medications prescribed. (P5)

Since admission I have been injected with several medications but I am still feeling the pain sometimes the nurses have to increase the dosage but the pain is still there. (P30)

Termination of fertility

Few participants reported having gone through an operation due to metastasized cancer to remove their uterus and fallopian tube. According to them, they are less than 40 years and wish to give birth to more children. Due to their operation, they could not give birth again, which was a worry to them.

I have gone through an operation and my uterus was removed. Though I have given birth to 2 children, my intention was to give birth to 2 more children. Am 40 years and I believe I can still give birth but due to the operation, I can’t give birth anymore. Among my siblings no one has given birth less than 3 children, but my cancer situation has terminated my fertility and I cannot give birth to any child again. (P19)

Even though I was informed I will not be able to give birth again before the surgery, I wish they can remove the old one and replace with someone’s own like a spare part so I can give birth now, because I have only one child who does not really care about my condition. He is a male and her wife is the one influencing him. I wish I had another daughter who could support me. (P28)

Nevertheless, few participants had no interest in giving birth again due to the challenges they encountered due to their condition.

Other participants reported that they would do family planning to interfere with their fertility.

I have three children and that is ok, I don’t think I have to give birth again because am feeling so much pain in my vagina and waist and the condition has made me weak. Even if I get pregnant which I know I won’t because I am 46 years, I will remove the pregnancy. (P21)

Discussion

Sexual functions of cervical cancer patients

Reduced sexual drive

This study revealed that cervical cancer patients experienced low libido. Factors that contribute to this problem were cervical cancer symptoms and the side effects of the chemotherapy. Another factor that is associated with the reduced sexual drive of cervical cancer patients was foul-smelling discharge. Vaginal sex is a common and satisfactory means for sexual pleasures for most people. The challenges experienced by these women made them reduce the number of times they had sex with their partners. This is because participants were not comfortable allowing their partners to have sex with them when they were bleeding through their vagina or having discharges that had a foul odor from their vagina. This was found to threaten their marital relationship since sex is vital for most couples and it strengthens most marriages. Other contributing factors for low sexual drive in cervical cancer patients in this study were severe pain during sex and vaginal bleeding. Also, most women revealed that they could not bear the pain when having coitus with their husbands. Feeling the pain during intercourse by one of the couples may affect the enjoyment process and attainment of orgasm. The study is in consonance with another study which ascertained that cervical cancer patients complained of loss of libido. 18 Similarly, a study conducted among cervical cancer patients found that some of the patients tend to have lower sexual function. 24 However, in a study to investigate sexual activeness of cervical cancer survivors in the United States, it was reported that 81.4% of the participants had a desire for sex. 42

Sexual gratification diversion is one of the critical findings of this study. The main route of sexual gratification for human satisfaction is vaginal intercourse. However, in most cases, cervical cancer affects the vagina due to the proximity to the cervix, making it impossible for victims to have sex. As a result, some participants in this study narrated that they have resulted in other body parts, such as breast sucking, massaging, and kissing, for their sexual pleasures. Breast sucking and kissing were usually considered as a romance leading to sexual pleasure. Hence, husbands of such women are recommended to adopt some of these means to ensure that their partner’s sexual desires are met, which may positively impact their psychological well-being and promote recovery. Even though the study findings were in consonance with other study findings in terms of sexual dysfunctions experienced by the participants,14,43 this study further revealed other ways of achieving sexual satisfaction without vaginal penetration. In addition, one unique finding uncovered in this study was that some of the participants were not concerned about their partner’s sexual life. According to the participants, they could not engage themselves in any sexual intercourse because of vaginal discharge and severe pain, which took their mind and attention from sexual enjoyment. This made them ignore their partner’s sexual feelings and desires. This is a problem since some men may cheat on their wives by having sex with other women.

Physical appearance is something that every individual is much particular about, especially among females. Hence, how a woman looks or comments made about their appearance may affect their overall well-being. One key factor that affects one’s physical appearance is weight. However, the study revealed that weight loss was common and evident among some participants with advanced cervical cancer. According to the participants, heavy vaginal bleeding and loss of appetite were the leading causes of the change in their physical appearance. Weight loss, even though it is physical, could affect other aspects of the woman’s health, such as social, psychological, and emotional well-being. Thus, a woman may end up isolating herself from the public to avoid being discussed because of her weight. This study supports findings of another study which established that cervical cancer patients experienced weight loss due to heavy vaginal bleeding. 44 Excruciating vaginal pain was another predictor to changes in the physical appearance of some cervical cancer women in this study since they reported that it interrupted their sleep.

A notable finding of this study was impaired rest and sleep of cervical cancer patients. One factor responsible for the sleep disturbance was severe pain that the patient usually experienced. Apart from that, heavy vaginal bleeding was one factor that accounted for poor sleep patterns in cervical cancer patients. The women reported that they have to wake up several times in the night to clean themselves and change their pads. After changing the pad, they could not sleep again, which affected their sleep pattern. Usually, an adult is expected to have 7–8 h of uninterrupted sleep to be fresh and gain energy for the next day. Frequent waking up in the night was found to disrupt participants’ sleep patterns. This could negatively impact the recovery and quality of life of these women. The finding of this study agrees with the study in Ghana which revealed that some of their participants’ sleep pattern was disrupted. 16

Chemotherapy is one of the main treatment options for cervical cancer that may be used alone or in combination with other treatments to destroy cancer cells, control growth, and palliation. However, there are numerous side effects of chemotherapy. In this study, the participants reported several chemotherapy side effects, including fatigue, hair loss, severe diarrhea, vomiting, and nausea. Some participants reported that they started losing hair a few weeks after starting treatment. According to them, they realize much hair on the comb when they brush the hair. This implies that cervical cancer patients will look unattractive to their husband and the general public, affecting them psychologically. Hair loss can be upsetting and distressing to women. Several studies reported hair loss in cancer treatment. This finding is in support of the results of another study which discovered that hair loss is associated with cancer treatment. 45 The interesting part of the findings in this study is that a participant reported how nice her hair has become after completion of the treatment. This should be a source of motivation to women who are worried about hair loss prior to their treatment since it is not permanent.

Vomiting was one of the significant side effects of chemotherapy experienced by participants of this study. According to the participants, they vomited few minutes after taking the drug. Some of the participants reported that they vomited several times, and they requested for change of medication. Vomiting is a severe side effect of chemotherapy since it can lead to dehydration, hypovolemic shock, and subsequent death. Vomiting in cervical cancer patients was reported in various studies. Similarly, a study found that cervical cancer patients reported vomiting as side effect of chemotherapy. 46 Vomiting was the most frequent short-term side effect of chemotherapy as found in another study. 47 Hence, other researchers may explore ways to manage these symptoms to prevent the complications.

Diarrhea and vaginal infections were also reported in some participants undergoing chemotherapy. Due to diarrhea, they had to visit the toilet several times, both day and night. This, according to some of the participants, made them weak. Others reported that they sometimes soil themselves before they get to the washroom. This implies that health care professionals should ensure bedpans and commodes are close to the patients on these treatments to prevent some of these issues, which may embarrass them. Also, their hygiene should be of significant concern to health professionals if they experience some of these problems to prevent infection. The study finding agrees with a previous study finding which discovered that diarrhea is a common side effect of chemotherapy. 48 It was not surprising that some of the participants experienced vaginal infections. Frequent infection was one of the significant effects of chemotherapy as reported by few of the participants. This may be due to lowered WBC due to chemotherapy. This is a problem since it may cause participants to incur extra cost treating these infections. The study finding is in consonance with the results of another study which identified that cancer patients experience low WBC count due to cancer medications thereby exposing them to frequent infection. 49

Termination of pregnancy was also a key finding in this study. Cervical cancer women in their reproductive age and who were fertile were worried that their fertility was terminated because of their condition. According to the participants, cancer had spread to their uterus, which led to the removal of their uterus. This caused much worry to the two participants who had undergone hysterectomy but wished to have more children. The decision to terminate the fertility by saving the woman’s life can make partners who wish to continue given birth go in for other women. However, partners are encouraged to show empathy to their wives and support them in these challenging times. This finding has corroboration with a study which unveiled that 57.7% of their participants suffered infertility while others suffered cervical stenosis after they had Abdominal Radical Tracheotomy (ART) for treatment. 46

Limitations of the study

The researchers only engaged participants in a face-to-face discussion without doing a focus group discussion which makes it a limitation; however, researchers used this method due to the outbreak of Covid 19. Only one approach which is a qualitative method is followed; however, other researchers could consider a mixed method in conducting a similar study.

Conclusion

Cervical cancer affects all aspects of a woman’s health, including sexual and physical well-being. Therefore, there is a need for more studies to help address challenges faced by cervical cancer women about their sexual and physical health.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-whe-10.1177_17455065211066075 for Impact of cervical cancer on the sexual and physical health of women diagnosed with cervical cancer in Ghana: A qualitative phenomenological study by Evans Osei Appiah, Ninon P Amertil, Ezekiel Oti-Boadi Ezekiel, Honest Lavoe and Dimah John Siedu in Women’s Health

Acknowledgments

The authors want to express their sincere gratitude to all the participants who took part in the study and the authors whose work were cited.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate: The Dodowa Health Research Centre Institutional Review Board provided clearance for this study to be conducted with the protocol identification number (DHRCIRB 158/11/20). Researchers sought approval verbally from all the participants after the purpose of the study was explained to them. Participants were also given a written informed consent form to sign as an evidence of their approval and as a legal document.

ORCID iD: Evans Osei Appiah  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6730-4725

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6730-4725

Availability of data and materials: Relevant data are in custody of the researchers and will be provided upon request.

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Beddoe AM. Elimination of cervical cancer: challenges for developing countries. Ecancermedicalscience 2019; 13: 975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tsu VD, Njama-Meya D, Lim J, et al. Opportunities and challenges for introducing HPV testing for cervical cancer screening in sub-Saharan Africa. Prev Med 2018; 114: 205–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Martyn F, McAuliffe FM, Wingfield M. The role of the cervix in fertility: is it time for a reappraisal? Human Reprod 2014; 29(10): 2092–2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shankar A, Prasad N, Roy S, et al. Sexual dysfunction in females after cancer treatment: an unresolved issue. Asian Pacific J Cancer Prevent 2017; 18(5): 1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McCormack M, Gaffney D, Tan D, et al. The Cervical Cancer Research Network (Gynecologic Cancer InterGroup) roadmap to expand research in low-and middle-income countries. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2021; 31(5): 775–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Finocchario-Kessler S, Wexler C, Maloba M, et al. Cervical cancer prevention and treatment research in Africa: a systematic review from a public health perspective. BMC Women Health 2016; 16(1): 1–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mwaka AD, Orach CG, Were EM, et al. Awareness of cervical cancer risk factors and symptoms: cross-sectional community survey in post-conflict northern Uganda. Health Expect 2016; 19(4): 854–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lim AW, Forbes LJ, Rosenthal AN, et al. Measuring the nature and duration of symptoms of cervical cancer in young women: developing an interview-based approach. BMC Women Health 2013; 13(1): 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Taneja N, Chawla B, Awasthi AA, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice on cervical cancer and screening among women in India: a review. Cancer Control 2021; 28: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wipperman J, Neil T, Williams T. Cervical cancer: evaluation and management. Am Fam Physic 2018; 97(7): 449–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Randall LM, Walker AJ, Jia AY, et al. Expanding our impact in cervical cancer treatment: novel immunotherapies, radiation innovations, and consideration of rare histologies. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2021; 41: 252–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dilalla V, Chaput G, Williams T, et al. Radiotherapy side effects: integrating a survivorship clinical lens to better serve patients. Curr Oncol 2020; 27(2): 107–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Devlin EJ, Denson LA, Whitford HS. Cancer treatment side effects: a meta-analysis of the relationship between response expectancies and experience. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017; 54(2): 245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fakunle IE, Maree JE. Sexual function in South African women treated for cervical cancer. Int J Africa Nurs Sci 2019; 10: 124–130. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ongtengco N, Thiam H, Collins Z, et al. Role of gender in perspectives of discrimination, stigma, and attitudes relative to cervical cancer in rural Sénégal. PLoS ONE 2020; 15(4): e0232291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Khalil J, Bellefqih S, Sahli N, et al. Impact of cervical cancer on quality of life: beyond the short term (results from a single institution). Gynecol Oncol Res Pract 2015; 2: 7–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pak R, Kaidarova D. Initial study of sexual function among cervical cancer survivors in Almaty, Kazakhstan. JCO Global Oncol 2018; 4: 50400. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ferrandina G, Petrillo M, Mantegna G, et al. Evaluation of quality of life and emotional distress in endometrial cancer patients: a 2-year prospective, longitudinal study. Gynecol Oncol 2014; 133(3): 518–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vermeer WM, Bakker RM, Kenter GG, et al. Cervical cancer survivors’ and partners’ experiences with sexual dysfunction and psychosexual support. Support Care Cancer 2016; 24(4): 1679–1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Boa R, Grénman S. Psychosexual health in gynecologic cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2018; 143(Suppl. 2): 147–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lammerink EA, de Bock GH, Pras E, et al. Sexual functioning of cervical cancer survivors: a review with a female perspective. Maturitas 2012; 72(4): 296–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tsatsou I, Parpa E, Tsilika E, et al. A systematic review of sexuality and depression of cervical cancer patients. J Sex Marital Ther 2019; 45(8): 739–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bae H, Park H. Sexual function, depression, and quality of life in patients with cervical cancer. Support Care Cancer 2016; 24(3): 1277–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Carter J, Sonoda Y, Baser RE, et al. A 2-year prospective study assessing the emotional, sexual, and quality of life concerns of women undergoing radical trachelectomy versus radical hysterectomy for treatment of early-stage cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2010; 119(2): 358–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sun C, Brown AJ, Jhingran A, et al. Patient preferences for side effects associated with cervical cancer treatment. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2014; 24(6): 1077–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Custódio ID, Marinho Eda C, Gontijo CA, et al. Impact of chemotherapy on diet and nutritional status of women with breast cancer: a prospective study. PLoS ONE 2016; 11(6): e0157113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Koom WS, Ahn SD, Song SY, et al. Nutritional status of patients treated with radiotherapy as determined by subjective global assessment. Radiat Oncol J 2012; 30(3): 132–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. O’Brien CP. Management of stomatitis. Canad Fam Physic 2009; 55(9): 891–892. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rosser JI, Njoroge B, Huchko MJ. Cervical cancer stigma in rural Kenya: what does HIV have to do with it? J Cancer Educ 2016; 31(2): 413–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gregg JL. An unanticipated source of hope: stigma and cervical cancer in Brazil. Med Anthropol Quart 2011; 25(1): 70–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Binka C, Doku DT, Awusabo-Asare K. Experiences of cervical cancer patients in rural Ghana: an exploratory study. PLoS ONE 2017; 12(10): e0185829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shoosmith R. Cervical cancer: how nurses can support people with human papillomavirus. Cancer Nurs Pract 2018; 9: 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jyani G, Chauhan AS, Rai B, et al. Health-related quality of life among cervical cancer patients in India. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2020; 30(12): 1887–1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shah UJ, Nasiruddin M, Dar SA, et al. Emerging biomarkers and clinical significance of HPV genotyping in prevention and management of cervical cancer. Microb Pathog 2020; 143: 104131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Endarti D, Riewpaiboon A, Thavorncharoensap M, et al. Evaluation of health-related quality of life among patients with cervical cancer in Indonesia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2015; 16(8): 3345–3350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nuhu FT, Odejide OA, Adebayo KO, et al. Psychological and physical effects of pain on cancer patients in Ibadan, Nigeria. Afr J Psychiatry 2009; 12(1): 64–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sileyew KJ. Research design and methodology. In: Cyberspace, 7 August 2019. Rijeka: IntechOpen. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Blanche MT, Blanche MJ, Durrheim K, et al. Research in practice: applied methods for the social sciences. Cape Town, South Africa: Juta and Company Ltd, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Connelly LM. Trustworthiness in qualitative research. Medsurg Nursing 2016; 25(6): 435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. New York: SAGE, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 2008; 62(1): 107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Greenwald HP, McCorkle R. Sexuality and sexual function in long-term survivors of cervical cancer. J Womens Health 2008; 17(6): 955–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rahman S. Female sexual dysfunction among Muslim women: increasing awareness to improve overall evaluation and treatment. Sex Med Rev 2018; 6(4): 535–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jou J, Coulter E, Roberts T, et al. Assessment of malnutrition by unintentional weight loss and its implications on oncologic outcomes in patient with locally advanced cervical cancer receiving primary chemoradiation. Gynecol Oncol 2021; 160(3): 721–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Paus R, Haslam IS, Sharov AA, et al. Pathobiology of chemotherapy-induced hair loss. Lancet Oncol 2013; 14(2): e50–e59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Li S, Hu T, Chen Y, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy, a valuable alternative option in selected patients with cervical cancer. PLoS ONE 2013; 8(9): e73837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yavas G, Yavas C, Dogan NU, et al. Pelvic radiotherapy does not deteriorate the quality of life of women with gynecologic cancers in long term follow-up: a two-year prospective single center study. Gynecol Oncol 2015; 137: 192–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. McQuade RM, Stojanovska V, Abalo R, et al. Chemotherapy-induced constipation and diarrhea: pathophysiology, current and emerging treatments. Front Pharmacol 2016; 7: 414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nguyen TH, Bach KQ, Vu HQ, et al. Pre-chemotherapy white blood cell depletion by therapeutic leukocytapheresis in leukemia patients: a single-institution experience. J Clin Apher 2020; 35(2): 117–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-whe-10.1177_17455065211066075 for Impact of cervical cancer on the sexual and physical health of women diagnosed with cervical cancer in Ghana: A qualitative phenomenological study by Evans Osei Appiah, Ninon P Amertil, Ezekiel Oti-Boadi Ezekiel, Honest Lavoe and Dimah John Siedu in Women’s Health