Abstract

Background.

Negative attitudes toward hospice care might prevent patients with cancer from discussing and choosing hospice as they approach end of life. When making a decision, people often naturally focus on either expected benefits or the avoidance of harm. Behavioral research has demonstrated that framing information in an incongruent manner with patients’ underlying motivational focus reduces their negative attitudes toward a disliked option.

Objective.

Our study tests this communication technique with cancer patients, aiming to reduce negative attitudes toward a potentially beneficial but often-disliked option, that is, hospice care.

Methods.

Patients (n = 42) with active cancer of different types and/or stages completed a paper survey. Participants read a vignette about a patient with advanced cancer and a limited prognosis. In the vignette, the physician’s advice to enroll in a hospice program was randomized, creating a congruent message or an incongruent message with patients’ underlying motivational focus (e.g., a congruent message for someone most interested in benefits focuses on the benefits of hospice, whereas an incongruent message for this patient focuses on avoiding harm). Patients’ attitudes toward hospice were measured before and after receiving the physician’s advice.

Results.

Regression analyses indicated that information framing significantly influenced patients with strong initial negative attitudes. Patients were more likely to reduce intensity of their initial negative attitude about hospice when receiving an incongruent message (b = −0.23; P < 0.01) than a congruent one (b = −0.13; P = 0.08).

Conclusion.

This finding suggests a new theory-driven approach to conversations with cancer patients who may harbor negative reactions toward hospice care.

Keywords: Decision making, end-of-life care, advice, attitude change, information framing, palliative care, cancer

Introduction

About 50% of patients at the end of life receive at least one potentially aggressive intervention.1 When high-stakes outcomes and strong negative emotions are at play, patients often optimistically rate their prognosis,2 which may lead to treatment choices the patient, or their loved ones, later regret.3,4 Evidence suggests that optimal physician-patient communication helps patients meet their preferences at the end of life.5 However, at times, patients’ negative attitudes toward hospice care can prevent them from discussing palliative care options with their physicians.6 Consequently, many patients do not consider discontinuing treatment and enrolling in hospice as they approach end of life. Behavioral research suggests, however, that information framing may impact how people perceive potentially beneficial choices. Applying these insights to physician-patient communication could help patients consider available options like hospice, even if they initially dislike these options.

This study tests an intervention that was discovered in recent social-psychology research to help individuals make decisions when strong emotions and attitudes are at stake.7 The study demonstrates that individuals who focused on avoiding losses while making a decision were more likely to change their negative attitudes toward an option if a clinician emphasized the benefits they could receive by choosing it (incongruent framing), instead of emphasizing what losses could be avoided (congruent framing). Alternatively, individuals who focused on achieving benefits were more likely to change their negative attitudes toward a disliked option if a clinician emphasized what losses could be avoided (incongruent framing) instead of emphasizing what benefits could be achieved (congruent framing). These findings are consistent with social-psychological theories (regulatory focus and regulatory fit) that have a robust impact on motivation and decision making across multiple contexts.8–10

We sought to extend these previous findings and explore the impacts of congruent and/or incongruent message framing among people for whom end-of-life decisions have high relevance. We recruited patients with active cancer in palliative medicine outpatient clinics to test the impact of information framing on patients’ perceptions about hospice enrollment. Patients were asked to report their attitudes toward hospice care. They observed a hypothetical situation in which a patient with end-stage cancer has to decide between continuing chemotherapy or choose hospice care instead. We hypothesized that when a physician recommends a potentially beneficial but unpleasant option, such as hospice care, if advice is framed in an incongruent manner (vs. congruent manner), patients will be more willing to re-evaluate their initial negative attitudes.

Methods

Participants

Patients with active cancer of different types and/or stages who attended Palliative Medicine clinics at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center completed a paper survey. This study was approved by Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Institutional Review Board. As the first study of this kind in a vulnerable patient population, we planned this as a small pilot project and, therefore, recruited a convenient sample of patients.

Procedure

Most patients (85%) completed the survey after their clinic appointments in the office. The remainder took the survey home and mailed it back to the office after completion. Participants read a vignette about a patient with advanced cancer and a limited prognosis. Following the methods of previous research in this area,7 patients reported their initial attitudes toward hospice after reading the vignette. This procedure helped us determine the degree of negativity of patients’ initial attitudes, as well as explore the influence of the advice-framing intervention, after adjusting for baseline attitudes. As the next step, using a validated procedure, we primed participants to think about either receiving benefits or avoiding harms while they were making a decision.11 A literature review demonstrates that studies that primed motivational orientations yield the same results as studies that measure motivational orientation.9 The priming procedure helps to ensure that we have an equal amount of participants who approach decisions thinking first about avoiding losses or reaching benefits. To prime participants to think about benefits, we asked them to recall three instances in which they successfully achieved gains. To prime participants to think about avoiding harms, we asked participants to write about three instances wherein they avoided losses. This priming procedure allowed us to orient participants to approach the evaluation of hospice care, thinking about either what harms could be avoided or what benefits could be achieved. Participants then learned from the vignette that the physician recommended hospice care, rather than continuing chemotherapy. When presenting this recommendation, the physician emphasized either receiving benefits (gains) of or avoiding harms (losses) in choosing to enroll in hospice. Participants received incongruently framed advice: if focused to think about benefits, they received advice that emphasized avoiding harms; or if focused to think about avoiding harms, they received advice that emphasized benefits. Those participants who received congruent messages experienced one of the following: if focused to think about benefits, they received advice that emphasized benefits; or if focused to think about avoiding harms, they received advice that emphasized avoiding harms. Because theoretically and psychologically these two incongruent experiences and two congruent experiences are equivalent, it is a common practice to combine participants into two groups: congruent and incongruent message recipients.12–16 Participants then reported their attitudes toward hospice again.

Attitude Change

Attitudes toward hospice care were assessed before and after the physician advice was provided, via a previously used scale.7 Participants were asked to rate their agreement with five statements. Based on their rating, two variables were created: initial attitude (α = 0.93; mean [M] = 5.00; SD = 1.44) and post-advice attitude (α = 0.91; M = 5.19; SD = 1.28). The dependent variable, attitude change, was created by subtracting participants’ initial attitude toward hospice from their post-advice attitude toward hospice (M = 0.19; SD = .72).

Study Design and Analysis

As a result of the priming procedure and advice randomization, two groups were created. The experimental group consisted of participants who received incongruent advice. The control group consisted of participants who received congruent advice. Theory and previous findings7 have indicated that incongruent message framing helps to reduce the intensity of initial attitudes. Therefore, initial attitudes need to be accounted for in the design and analysis. We used a linear regression analysis to explore the effect of the congruent and/or incongruent information framing on attitude change. To account for initial attitudes, we included the baseline measure as an independent variable in the regression analysis. We used bootstrapping procedures that address the imperfection of a sampling distribution because of a limited sample size.17

Results

Participants

Of 93 eligible participants approached, 42 (45%) returned a completed survey. Sixty percent of participants were younger than 65 years; 39% were males; 70% were white; 22% were of African American origin; and 8% were Asian, Hispanic, or other; 65% of participants had a college education.

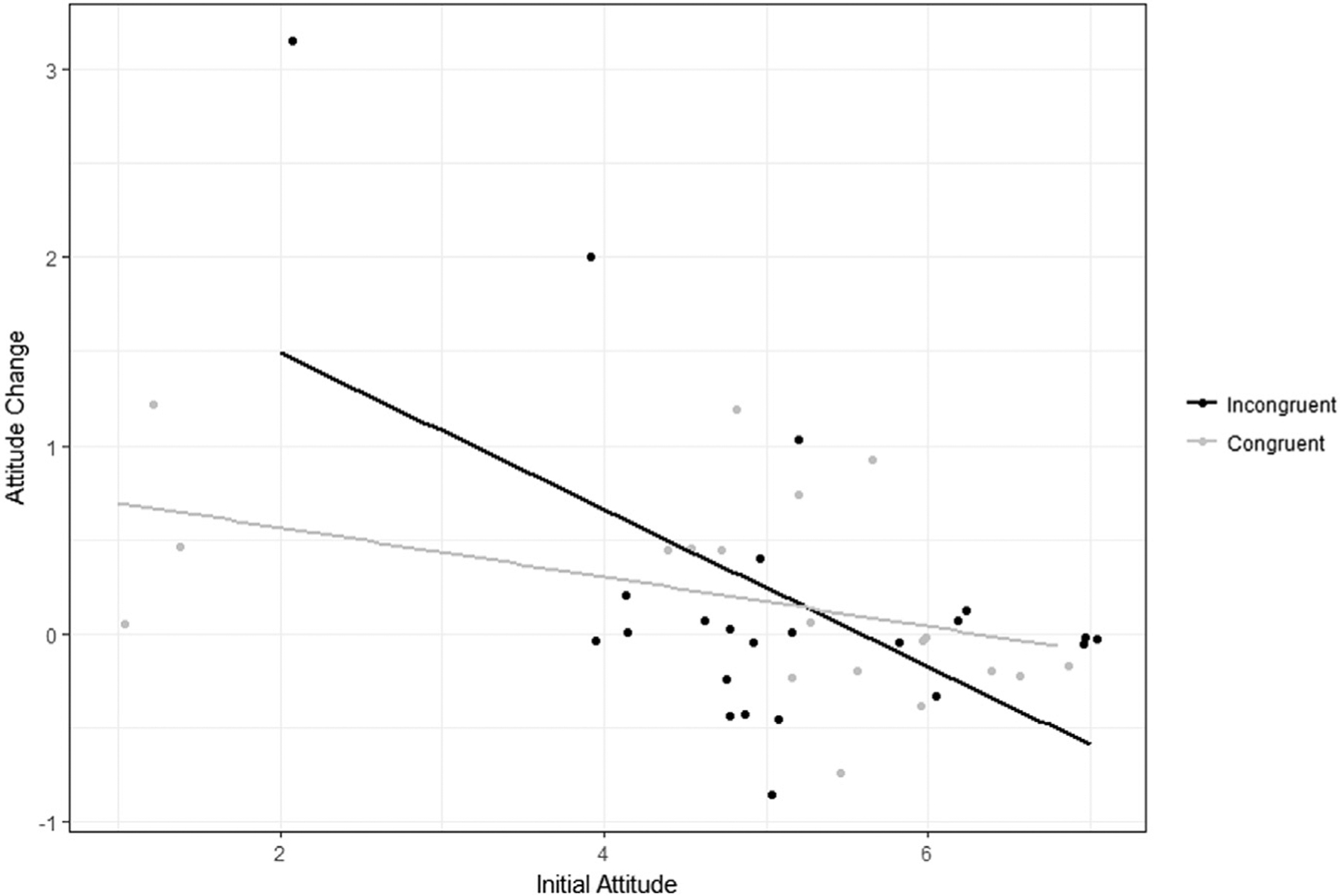

Attitude Change

The previous research has demonstrated that incongruent message framing was effective if participants had initial negative attitudes toward the recommended option.7 Following the previous research, we included in the analysis the following variables: the main effect of initial attitudes, the main effect of the message framing, and their interaction: 2 (incongruent message and congruent message) by (initial attitude) regressed on participants’ attitude change. The summary indicated that the proposed model was appropriate and statistically significant (r2 = 0.28; P = 0.01). The main effect of the initial attitude was significant (b = −0.42; SE = 0.12; t[38] = −3.52; P < 0.01; 95% CI −0.66, −0.18). This result suggests that the more negative participants’ initial attitudes were, the more they improved their attitude as a result of the advice. The effect of congruent advice vs. incongruent advice was also significant (b = −1.50; SE = 0.76; t[38] = −1.97; P = 0.056; 95% CI −3.05, 0.04), suggesting that incongruent advice has a stronger influence on attitude change than congruent. More importantly, the interaction between initial attitudes and congruent and/or incongruent framing of advice was significant (b = 0.28; SE = 0.15; t[38] = 1.98; P = 0.058; 95% CI −0.01, 0.58), suggesting that the framing of the message impacted patients’ initial negative attitudes. Uncovering this interaction, we found that as expected, the patients who had initial negative attitudes toward hospice were more likely to reduce the intensity of their initial negative attitudes when receiving incongruent advice (b = −0.23; SE = 0.07; t = −3.21; P < 0.01; 95% CI −0.66, −0.18; Fig. 1) than a congruent one (b = −0.13; SE = 0.07; t = −1.89; P = 0.08; 95% CI −0.31, 0.04). As expected, less negative attitudes were not significantly affected by advice framing. To check the robustness of our results, we used the Winsorizing procedure.18 The largest outlier was substituted with the value of the nearest extreme. Conditional effects were comparable with these that we report with unadjusted data: incongruent advice (b = −0.29; SE = 0.11; t = −2.73; P < 0.01; 95% CI −0.50, −0.07) and congruent advice (b = −0.13; SE = 0.07; t = −1.72; P = 0.09; 95% CI −0.29, 0.02).

Fig. 1.

Attitude change as a function of initial attitudes and incongruent and/or congruent information (n = 42). Y axis shows the extent to which patients make their initial negative attitude toward hospice more positive after receiving hypothetical advice about hospice. X axis indicates initial attitudes toward hospice care. Lower numbers correspond to initial negative attitudes. The black line represents the average rating of participants who received an incongruent message. The gray line represents the average rating of participants who received a congruent message.

An additional analysis indicated that framing of advice by itself did not influence the negative attitude reduction (b = −0.34; P = 0.67), meaning that neither advice that emphasized benefits nor advice that emphasized avoiding harms had an effect on attitude change by itself. Only the combination of advice framing and individual motivational orientations reduced initial negative attitude toward an initially disliked hospice option.

Discussion

Our study shows that incongruently framed advice influenced patients’ evaluations of a recommended but disliked hospice option. Although physician advice itself had a positive impact on individuals’ initial attitudes across all conditions, the framing of advice also had an important impact, specifically for those patients who had initial negative attitudes toward the recommended option. We found that patients with strong negative initial attitudes toward hospice were more likely to adjust their attitudes to be less negative if they received advice that was framed incongruently (vs. congruently) with their initial motivational focus (avoiding harms vs. receiving benefits). These findings are consistent with an extensive body of research suggesting that incongruently framed messages increase individuals’ motivation to process information and, therefore, increase their motivation to pay close attention to the arguments presented.12,13 Similarly, in our research, participants were more likely to think through the advice (vs. discard it) for a disliked option if it was framed incongruently (vs. congruently).

Incongruent advice framing aims to counteract a patients’ tendency to dismiss unpleasant advice. Therefore, incongruent advice was more effective among those who have strong negative attitudes and might be more inclined to react defensively; but it did not influence those who have less negative attitudes toward recommended option and were more willing to consider the advice even before the intervention.

Our results confirmed previous observations among healthy volunteers in the behavior laboratory and applied them to a real-world setting.7 Thus, this study provides evidence that the proposed behavior intervention could be helpful in conversations with a vulnerable population of patients facing end-of-life conversations, who are likely to experience more negative reactions and attitudes than healthy individuals.

Our findings add to the research that investigates behavioral interventions to help communicate negative information to patients.19,20 Specifically, we proposed a conceptually new approach that could help clinicians reduce patients’ negative reactions toward a recommended option and potentially facilitate patients’ willingness to consider initially disliked but beneficial options.

To implement our proposed intervention in practice, a physician could consider recommending a beneficial but disliked option, such as hospice care, framing it in a way that would counter the patients’ motivational orientations. A physician could assess a patient’s motivational focus during a consultation. More patients will likely focus on benefits rather on avoiding harms because in Western culture, individuals have a natural inclination to focus on receiving benefits rather than on avoiding losses.21 If assessing patients’ preferences during a consultation proves challenging, another way would be to ask a patient to think about either the benefits or the harms of an option first, and then frame any provided advice in an incongruent manner. For example, if a patient with negative attitudes toward hospice care focuses on benefits while making decisions, the physician’s advice should emphasize the harms that hospice could help avoid (e.g., avoid side effects of cancer treatment). Alternatively, if a patient with negative attitudes toward hospice care focuses on avoiding harms while making decisions, the physician’s advice should emphasize the benefits that the patients could achieve (e.g., having more meaningful time with loved ones). This incongruence between motivational focus and message framing would deintensify a patients’ initial negative attitudes toward hospice, thereby improving chances that they consider this option.

A limitation of this study is that a proportion of patients declined to participate because of their physical weakness, inability to concentrate, or their busy schedules of medical appointments. As a result, the sample size of this experiment is limited. This study was planned as a pilot project to explore feasibility and influence/significance of message framing in sensitive conversations about end of life, and calls for further testing. Our study has demonstrated promising results and confirmed the feasibility of testing a theory-driven behavioral intervention among a vulnerable patient population. Further research should test the proposed intervention within a larger sample, exploring different clinical settings and various patient populations.

Another limitation is that patients evaluated hypothetical options in the decision-making scenario rather than evaluated their own actual treatment and nontreatment options. At this stage of our research, it would not be ethical or feasible to manipulate the framing of physicians’ advice in clinical situations. We must first use experimental settings to develop a better understanding of what effect this intervention could have on individuals’ decision making. To do so, we developed a hypothetical scenario that was drafted based on the existing literature22 and validated by clinical oncologists. The scenario closely resembled actual decisions that patients who visit palliative clinics had to deal with during the course of their disease. Next steps should include studies in which patients’ personal inclinations are measured rather than manipulated, and studies in which the intervention is tested in actual conversations.

We explored incongruent advice framing within the context of negative attitudes. Assessing patients’ attitudes toward hospice, we were likely operating on the continuum of extreme negative attitudes and more neutral attitudes (rather than positive attitudes toward hospice). We observed that incongruent message framing reduced extremely negative attitudes, but had an insignificant impact on these with neutral attitudes toward hospice. Theoretically, incongruent messages could reduce extremely positive attitudes as well. It would be interesting to explore in future studies how incongruently framed discussions influence patients’ positive attitudes toward continuing chemotherapy at the end stage of their cancer. Despite its limitations, our study provides evidence that congruent and incongruent advice framing influences patients’ evaluations of medical options and, therefore, could be helpful in medical communications specifically for patients who may harbor negative reactions toward a potentially beneficial choice.

Disclosures and Acknowledgments

This research received no specific funding/grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Wang SY, Hall J, Pollack CE, et al. Trends in end-of-life cancer care in the Medicare program. J Geriatr Oncol 2016;7:116–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gramling R, Fiscella K, Xing G, et al. Determinants of patient-oncologist prognostic discordance in advanced cancer. JAMA Oncol 2016;2:1421–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Izumi SS, Van Son C. “I didn’t know he was dying”: missed opportunities for making end-of-life care decisions for older family members. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 2016;18: 74–81. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hu JC, Kwan L, Saigal CS, Litwin MS. Regret in men treated for localized prostate cancer. J Urol 2003;169: 2279–2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trice ED, Prigerson HG. Communication in end-stage cancer: review of the literature and future research. J Health Commun 2009;14:95–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Perceptions of palliative care among patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers. CMAJ 2016;188:E217–E227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fridman I, Scherr K, Glare P, Higgins ET. Using a non-fit message helps to de-intensify negative reactions to tough advice. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2016;42:1025–1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Higgins ET. Promotion and prevention: How “0” can create dual motivational forces. Dual-process theories of the social mind. New York: Guilford Publications, 2014: 423–436. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Motyka S, Grewal D, Puccinelli NL, et al. Regulatory fit: a meta analytic synthesis. J Consum Psychol 2014;24: 394–404. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ludolph R, Schulz PJ. Does regulatory fit lead to more effective health communication? A systematic review. Soc Sci Med 2015;128:142–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins ET, Friedman RS, Harlow RE, et al. Achievement orientations from subjective histories of success: promotion pride versus prevention pride. Eur J Soc Psychol 2001;31:3–23. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koenig AM, Cesario J, Molden DC, Kosloff S, Higgins ET. Incidental experiences of regulatory fit and the processing of persuasive appeals. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2009;35:1342–1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vaughn LA, O’Rourke T, Schwartz S, et al. When two wrongs can make a right: regulatory nonfit, bias, and correction of judgments. J Exp Soc Psychol 2006;42: 654–661. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee AY, Aaker JL. Bringing the frame into focus: the influence of regulatory fit on processing fluency and persuasion. J Pers Soc Psychol 2004;86:205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cesario J, Grant H, Higgins ET. Regulatory fit and persuasion: transfer from “feeling right.’’. J Pers Soc Psychol 2004;86:388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vaughn LA, Malik J, Schwartz S, Petkova Z, Trudeau L. Regulatory fit as input for stop rules. J Pers Soc Psychol 2006;91:601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayes AF. Beyond Baron and Kenny: statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun Monogr 2009;76:408–420. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tukey JW, McLaughlin DH. Less vulnerable confidence and significance procedures for location based on a single sample: trimming/Winsorization. Ind J Stat Ser A 1963;1: 331–352. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Porensky EK, Carpenter BD. Breaking bad news: effects of forecasting diagnosis and framing prognosis. Patient Educ Couns 2016;99:68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Osch M, Sep M, van Vliet LM, van Dulmen S, Bensing JM. Reducing patients’ anxiety and uncertainty, and improving recall in bad news consultations. Health Psychol 2014;33:1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hamamura T, Meijer Z, Heine SJ, Kamaya K, Hori I. Approach—avoidance motivation and information processing: a cross-cultural analysis. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2009;35: 454–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klastersky J, Paesmans M. Response to chemotherapy, quality of life benefits and survival in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: review of literature results. Lung Cancer 2001;1:95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]