Abstract

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) is a potentially fatal condition caused by a brain infection with JC polyomavirus (JCV), which occurs almost exclusively in immunocompromised patients. Modern immunosuppressive and immunomodulatory treatments for cancers and autoimmune diseases have been accompanied by increasing numbers of PML cases. We report a psoriasis patient treated with fumaric acid esters (FAEs) with concomitant hypopharyngeal carcinoma and chronic alcohol abuse who developed PML. Grade 4 lymphopenia at the time point of PML diagnosis suggested an immunocompromised state. This case underscores the importance of immune cell monitoring in patients treated with FAEs, even more so in the presence of additional risk factors for an immune dysfunction.

Keywords: progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, psoriasis, fumaric acid esters, carcinoma

Case Report

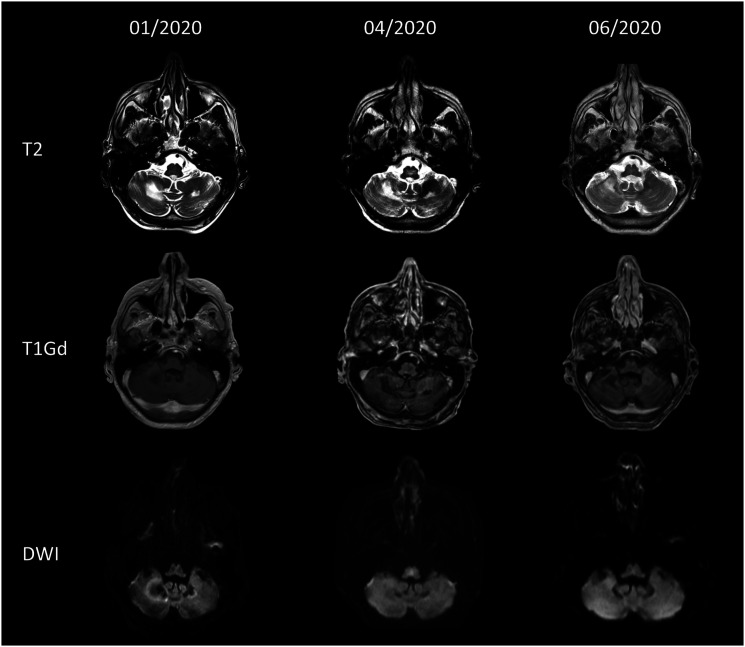

A 52-year-old man presented to our neurological department in March 2020 reporting progressive limb ataxia and cognitive impairment including disorientation, attention and memory deficits, and reduced speech fluency since January 2020. Cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed multifocal T2w-hyperintense white-matter lesions without contrast-enhancement, edema, or restricted diffusion predominantly involving the cerebellum (Figure 1). Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis revealed an elevation of protein levels with presence of CSF-specific oligoclonal IgG-bands and an increased CSF/serum albumin quotient as a marker of blood–brain barrier disruption, whereas the cell count was normal. The detection of 144 copies/mL of the JC virus (JCV) in CSF by polymerase chain reaction prompted the diagnosis of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML).

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging findings over time. Upper row: T2-weighted axial images show hyperintense white-matter lesions in the cerebellum. Middle row: Axial T1 gadolinium (Gd)-weighted images show no Gd-enhancement. Lower row: Axial diffusion weighted image shows no restricted diffusion.

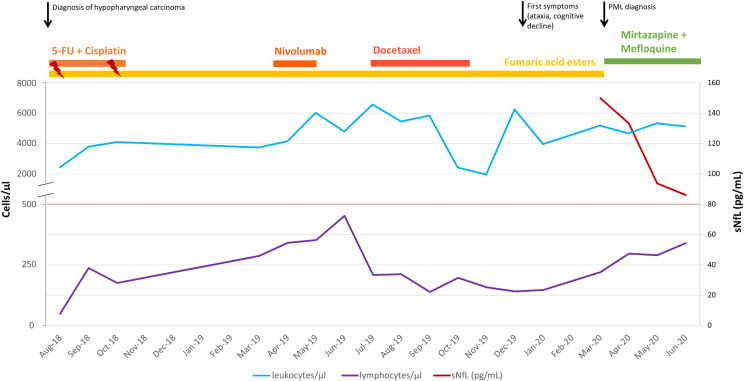

During the previous 24 months, the patient’s psoriasis was being treated with fumaric acid esters (FAEs) (Fumaderm®). During this time, lymphocyte counts were below 500/mm³ in all routine measurements (Figure 2). At the time of PML diagnosis, the lymphocyte count was 147/mm3 consistent with severe grade 4 lymphopenia, whereas the leukocyte count was within normal ranges. Furthermore, the patient had been diagnosed with hypopharyngeal carcinoma in July 2018, for which he received chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin (from August 2018 until October 2018 with adjuvant radiation in weeks 1 and 5), nivolumab (3 cycles from April 2019 until May 2019), and docetaxel (6 cycles from July 2019 until October 2019). The clinical history included chronic alcohol and nicotine abuse (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Overview of the patient’s history and serum neurofilament light chain values. Leukocyte counts are displayed as a blue line. Lymphocyte counts are displayed as a violet line. Clinical events (black arrows) are indicated. Duration of treatments is depicted with lines of different colors on the top of the diagram. Serum neurofilament light chain levels are displayed as a red line.

After the PML diagnosis, FAE therapy was discontinued immediately. In addition, we initiated an off-label treatment attempt with mefloquine 250 mg per week and mirtazapine 15 mg per day based on in vitro data showing antiviral effects1,2 and observations from several case reports (see Table 1). We stress that this treatment regimen has not convincingly prolonged survival or reduced disability in clinical trials so far.3-6

Table 1.

Overview of previous PML reports in FAE-treated psoriasis patients.

| Case reference | Age, sex | Underlying conditions with immunocompromising potential | Duration of FAE treatment prior to PML onset | Other immunosuppressive treatments within 5 years prior to PML onset | Grade of lymphopenia a at PML onset | Duration of lymphopenia prior to PML onset | PML treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present case report | 52-year-old male | Psoriasis, hypopharyngeal carcinoma, and alcohol abuse | 2 years | Chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin (terminated 17 months prior to PML onset), nivolumab (last cycle 10 months prior to PML onset), and docetaxel (terminated 5 months prior to PML onset) | 4 | 18 months | Discontinuation of FAE treatment and off-label use of mirtazapine and mefloquine | Partial recovery from clinical symptoms, remission of MRI lesions, decrease in CSF JCV DNA titer and in sNfL levels |

| van Oosten et al (2013) 27 | 42-year-old female | Psoriasis | 5 years | None | 3 | 5 years | Discontinuation of FAE treatment and off-label use of mirtazapine and mefloquine | Development of PML-IRIS followed by partial clinical recovery |

| Ermis et al (2013) 28 | 74-year-old male | Psoriasis | 3 years | Methotrexate (terminated 3 years prior to PML onset) | 3 | 2 years | Discontinuation of FAE treatment and off-label use of mirtazapine and mefloquine | Development of PML-IRIS, followed by partial remission of clinical signs and MRI findings |

| Buttmann et al (2013), Sweetser et al (2013)29,30 | 60-year-old female | Psoriasis, and pulmonary sarcoidosis | 3 years | Prednisolone and methotrexate (terminated 3.5 years prior to PML onset) | 2–3 | 20 months | No information available | Partial recovery with mild-to-moderate residual symptoms |

| Stoppe et al (2014), Sweetser et al (2013)15,30 | Male patient, no information on age available | Psoriasis, and superficial spreading melanoma | 3 years | Efalizumab (terminated 3 years prior to PML onset) | 2–3 | No information available | Discontinuation of FAE treatment and off-label use of mirtazapine, mefloquine, and immunoglobulins | Partial recovery |

| Bartsch et al (2015) 12 | 68-year-old male | Psoriasis, and adenocarcinoma of the rectum 8 years earlier (adjuvant radiochemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil) | 2.5 years | None | 2 | 16 months | Discontinuation of FAE treatment and off-label use of mirtazapine and mefloquine | Partial recovery |

| Nieuwkamp et al (2015) 13 | 64-year-old female | Psoriasis | 2 years | None | 2 | 1 month | Discontinuation of FAE treatment and off-label use of mirtazapine, mefloquine, and steroids | Deceased |

| Dammeier et al (2015) 31 | 53-year-old female | Psoriasis | 1.5 years | None | 2–3 | No information available | Discontinuation of FAE treatment and off-label use of mirtazapine and mefloquine | Stable disease course with only mild residual deficits at 7-month follow-up |

| Hoepner et al (2015) 32 | 69-year-old male | Psoriasis, and monoclonal gammopathy | 4 years | None | 2–3 | At least 18 months | Discontinuation of FAE treatment and off-label use of mirtazapine and mefloquine | Development of mild PML-IRIS followed by partial recovery |

| Elsner et al (2020) 33 | 58-year-old female | Psoriasis | 4 years | No information available | No information available | No information available | Discontinuation of FAE treatment and antiviral treatment (not specified) | Persisting global aphasia and recurrent seizures |

| Case series by Gieselbach et al (2017) 14 | 57-year-old male | Psoriasis | 4 years | No information available | 1–3 | 4 years | No information available | Survived |

| Case series by Gieselbach et al (2017) 14 | 50-year-old female | Psoriasis | 9 years | No information available | 2–3 | 6 years | No information available | Survived |

| Case series by Gieselbach et al (2017) 14 | 71-year-old male | Psoriasis | 1.5 years | No information available | 3 | No information available | No information available | Survived |

| Case series by Gieselbach et al (2017) 14 | 64-year-old female | Psoriasis, breast carcinoma (10 years prior to PML) | .5 years | Cyclophosphamide | 3 | No information available | No information available | Survived |

Abbreviations: CSF: cerebrospinal fluid, DNA, desoxyribonucleic acid; FAE, fumaric acid ester; IRIS, immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome; JCV, JC virus; PML, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy.

aGrade 1 lymphopenia = 800–100 cells per mm3, Grade 2 lymphopenia = 500–800 cells per mm3, Grade 3 lymphopenia = 500–200 cells per mm3, Grade 4 lymphopenia <200 cells per mm3.

During this course of treatment, there was a gradual rise of lymphocyte counts without clinical evidence of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome; CSF analysis 3 weeks after PML diagnosis already showed a slight decrease in JCV DNA levels (117 copies/mL). Clinically, the patient experienced improvement of cognitive function, but significant limb ataxia persisted. MRI follow-up examination revealed regression of the cerebellar lesions (Figure 1). Serum neurofilament light chain (sNfL) levels were 149.9 pg/mL at PML diagnosis and constantly declined over the follow-up measurements 1, 2, and 3 months after diagnosis (Figure 2). There were no serum samples available to assess sNfL levels prior to PML diagnosis. sNfL was shown to serve as a non-specific biomarker of PML in natalizumab-treated multiple sclerosis (MS) patients7,8 discriminating patients with PML from those without PML with high accuracy in a retrospective study. 7 A recent study in a prospective cohort confirmed that sNfL levels can identify natalizumab-treated MS patients who will develop PML with a sensitivity of 67% and specificity of 80%. 9 These results highlight the value of sNfL as a biomarker in clinical practice to monitor the occurrence and early recognition of PML.

This patient had numerous risk factors for developing PML, but he exhibited severe lymphopenia for approximately 18 months (minimal lymphocyte count 48/mm3) before emergence of neurological deficits. Lymphopenia is a known side effect of FAE and is more likely to occur with older age. 10 FAE therapy should be terminated if the lymphocyte count drops below 500/mm3 (corresponding to grade 3 and grade 4 lymphopenia) as the risk for opportunistic infections increases. 11 Previous reports of PML in FAE-treated psoriasis patients show low lymphocyte counts in all patients (Table 1), although some patients only had grade 1 or grade 2 lymphopenia at the time point of PML diagnosis.12,13 Nevertheless, marked lymphocyte reduction is a modifiable risk factor in the prevention of PML and the existing recommendations for regular lymphocyte monitoring upon FAE therapy should be followed rigorously.

A second aspect that has likely contributed to the immunocompromised state along with PML development in this patient is the presence of concomitant hypopharyngeal carcinoma with various chemotherapeutic treatments. Remarkably, three of the previously published FAE-treated psoriasis patients who developed PML also had a history of concomitant malignancy; two of them received chemotherapy.12,14,15 It is therefore difficult to separate the contributing effect of the malignancy on immune dysfunction from the effect its chemotherapy exhibits.

The previous treatment with the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab in this patient is a topic of special interest since checkpoint inhibitors are currently discussed as a promising therapeutic option for the treatment of PML. They are believed to target pathways that are involved in immune exhaustion and reinvigorate antiviral immunity by restoring the anti-JCV activity of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. 16 In several case reports and a small-scope case series, PD-1 inhibitor treatment with nivolumab or pembrolizumab was associated with clinical improvements in some patients.17-20 However, there are also reports of patients who developed PML after treatment with nivolumab, 21 and cases where PML deteriorated despite treatment with pembrolizumab.22,23 Additional analyses revealed that checkpoint inhibitors seem to be most promising in patients with some detectable anti-JCV cellular immune response before treatment, whereas advanced PML and profound immune compromise are associated with a poor treatment response. 23 Of note, our patient’s chronic alcohol abuse might represent an additional risk factor for PML development.24-26

Taken together, we believe that the case reported here represents an illustrative example of the complexity of FAE treatment in patients exposed to situations of generalized immunosuppression such as chemotherapies. In retrospect, it is evident that this patient had an increased risk for the development of an opportunistic infection in general, and for PML in particular. Likewise, it is also indisputable that the occurrence of hypopharyngeal carcinoma required an effective treatment. However, the initiation of chemotherapy should have prompted the reevaluation of FAE treatment, especially when the lymphocyte count dropped to critical levels. From our point of view, this highlights the need to educate FAE-prescribing physicians about lymphocyte monitoring and PML and emphasizes that they must closely coordinate their immunotherapy with other physicians involved such as the oncologist.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Cheryl Ernest for proofreading the manuscript.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical/Consent Statement: The patient in this manuscript has given written informed consent to publication of his case details.

ORCID iDs

Sinah Engel https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9051-9062

Felix Luessi https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4334-4199

References

- 1.Brickelmaier M, Lugovskoy A, Kartikeyan R, et al. Identification and characterization of mefloquine efficacy against JC virus in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53(5):1840-1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elphick GF, Querbes W, Jordan JA, et al. The human polyomavirus, JCV, uses serotonin receptors to infect cells. Science. 2004;306(5700):1380-1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blankenbach K, Schwab N, Hofner B, Adams O, Keller-Stanislawski B, Warnke C. Natalizumab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in Germany. Neurology. 2019;92(19):e2232-e2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clifford DB, Nath A, Cinque P, et al. A study of mefloquine treatment for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: results and exploration of predictors of PML outcomes. J Neurovirol. 2013;19(4):351-358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stefoski D, Balabanov R, Waheed R, Ko M, Koralnik IJ, Sierra Morales F. Treatment of natalizumab-associated PML with filgrastim. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2019;6(5):923-931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tan IL, McArthur JC, Clifford DB, Major EO, Nath A. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in natalizumab-associated PML. Neurology. 2011;77(11):1061-1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalla Costa G, Martinelli V, Moiola L, et al. Serum neurofilaments increase at progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy onset in natalizumab-treated multiple sclerosis patients. Ann Neurol. 2019;85(4):606-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaiottino J, Norgren N, Dobson R, et al. Increased neurofilament light chain blood levels in neurodegenerative neurological diseases. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e75091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fissolo N, Pignolet B, Rio J, et al. Serum neurofilament levels and pml risk in patients with multiple sclerosis treated with natalizumab. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2021;8(4):e1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Longbrake EE, Naismith RT, Parks BJ, Wu GF, Cross AH. Dimethyl fumarate-associated lymphopenia: risk factors and clinical significance. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2015;1:2055217315596994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nast A, Gisondi P, Ormerod AD, et al. European S3-guidelines on the systemic treatment of psoriasis vulgaris--update 2015--short version--EDF in cooperation with EADV and IPC. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(12):2277-2294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bartsch T, Rempe T, Wrede A, et al. Progressive neurologic dysfunction in a psoriasis patient treated with dimethyl fumarate. Ann Neurol. 2015;78(4):501-514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nieuwkamp DJ, Murk J-L, Cremers CHP, et al. PML in a patient without severe lymphocytopenia receiving dimethyl fumarate. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(15):1474-1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gieselbach R-J, Muller-Hansma AH, Wijburg MT, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in patients treated with fumaric acid esters: a review of 19 cases. J Neurol. 2017;264(6):1155-1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stoppe M, Thomä E, Liebert UG, et al. Cerebellar manifestation of PML under fumarate and after efalizumab treatment of psoriasis. J Neurol. 2014;261(5):1021-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cortese I, Reich DS, Nath A. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and the spectrum of JC virus-related disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2021;17(1):37-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cortese I, Muranski P, Enose-Akahata Y, et al. Pembrolizumab treatment for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(17):1597-1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rauer S, Marks R, Urbach H, et al. Treatment of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy with pembrolizumab. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(17):1676-1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walter O, Treiner E, Bonneville F, et al. Treatment of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy with nivolumab. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(17):1674-1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoang E, Bartlett NL, Goyal MS, Schmidt RE, Clifford DB. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy treated with nivolumab. J Neurovirol. 2019;25(2):284-287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martinot M, Ahle G, Petrosyan I, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy after treatment with nivolumab. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24(8):1594-1596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Küpper C, Heinrich J, Kamm K, Bücklein V, Rothenfusser S, Straube A. Pembrolizumab for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy due to primary immunodeficiency. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2019;6(6):e628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pawlitzki M, Schneider-Hohendorf T, Rolfes L, et al. Ineffective treatment of PML with pembrolizumab: exhausted memory T-cell subsets as a clue? Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2019;6(6):e627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Acket B, Guillaume M, Tardy J, Dumas H, Sattler V, Bureau C. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient with alcoholic cirrhosis. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2010;34(4-5):336-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gheuens S, Pierone G, Peeters P, Koralnik IJ. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in individuals with minimal or occult immunosuppression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81(3):247-254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grewal J, Dalal P, Bowman M, Kaya B, Otero JJ, Imitola J. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient without apparent immunosuppression. J Neurovirol. 2016;22(5):683-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Oosten BW, Killestein J, Barkhof F, Polman CH, Wattjes MP. PML in a patient treated with dimethyl fumarate from a compounding pharmacy. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(17):1658-1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ermis U, Weis J, Schulz JB. PML in a patient treated with fumaric acid. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(17):1657-1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buttmann M, Stoll G. Case reports of PML in patients treated for psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(11):1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sweetser MT, Dawson KT, Bozic C. Manufacturer’s response to case reports of PML. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(17):1659-1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dammeier N, Schubert V, Hauser T-K, Bornemann A, Bischof F. Case report of a patient with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy under treatment with dimethyl fumarate. BMC Neurol. 2015;15:108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoepner R, Faissner S, Klasing A, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy during fumarate monotherapy of psoriasis. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2015;2(3):e85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elsner P. Insufficient laboratory monitoring and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy on fumaric acid ester therapy for psoriasis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2020;18(4):367-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]