Abstract

mRNA display is a powerful biological display platform for the directed evolution of proteins and peptides. mRNA display libraries covalently link the displayed peptide or protein (phenotype) with the encoding genetic information (genotype) through the biochemical activity of the small molecule puromycin. Selection for peptide/protein function is followed by amplification of the linked genetic material and generation of a library enriched in functional sequences. Iterative selection cycles are then performed until the desired level of function is achieved, at which time the identity of candidate peptides can be obtained by sequencing the genetic material.

The purpose of this review is to discuss the development of mRNA display technology since its inception in 1997 and to comprehensively review its use in the selection of novel peptides and proteins. We begin with an overview of the biochemical mechanism of mRNA display and its variants with a particular focus on its advantages and disadvantages relative to other biological display technologies. We then discuss the importance of scaffold choice in mRNA display selections and review the results of selection experiments with biological (e.g., fibronectin) and linear peptide library architectures. We then explore recent progress in the development of “drug-like” peptides by mRNA display through the post-translational covalent macrocyclization and incorporation of non-proteogenic functionalities. We conclude with an examination of enabling technologies that increase the speed of selection experiments, enhance the information obtained in post-selection sequence analysis, and facilitate high-throughput characterization of lead compounds. We hope to provide the reader with a comprehensive view of current state and future trajectory of mRNA display and its broad utility as a peptide and protein design tool.

Keywords: mRNA display, directed evolution, in vitro selection, non-natural amino acids, macrocyclization, next generation sequencing

Graphical Table of Contents

1. Overview

New functional proteins and peptides can aid in the development of new therapeutics to treat human disease or function as molecular tools to help solve biological and chemical problems. Despite recent advances in the rational design of proteins,1 directed evolution remains an important and robust functional solution to engineer new protein and peptide function. In directed evolution, a large library of diverse proteins is first partitioned for a desired function and the functional molecules are subsequently amplified. This process is repeated until most to all of the pool is highly enriched in molecules that perform the desired task (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Directed evolution process.

In directed evolution, a library of molecules is subjected to a selective step that separates functional and non-functional molecules. Functional molecules are then amplified to generate a library for the next round of selection. This process is repeated until the library is dominated by functional molecules. Directed evolution requires that the genotype (e.g., DNA or RNA) is linked to its corresponding phenotype (function).

A key requirement for directed evolution is that the genotype (i.e., DNA or RNA) and phenotype (function) of the molecules must be linked, otherwise amplification of the “fittest” sequences is impossible. The directed evolution of proteins presents a challenge: once a protein is synthesized during translation, its sequence information is lost; no current methods are capable of reverse translation nor can the protein be directly amplified through a process analogous to polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Several “display” methods have been developed to link a protein to its encoding genetic material including phage display (PD)2, 3, mRNA display,4 ribosome display,5 peptides-on-plasmids,6 and CIS display.7 For a comprehensive discussion of biological display technologies, the reader is directed to these reviews.8–12

Of these display methods, mRNA display has several unique advantages over other display techniques including the ability to generate the most diverse peptide libraries and the ability to engineer drug-like peptides containing unnatural amino acids. Over the last 20 years, mRNA display has been used to develop high affinity ligands against a wide range of targets including intracellular proteins, extracellular proteins, membrane proteins, and RNA. In this review, we first introduce basic mRNA display principles, mechanisms, and variants. We define mRNA display as any technique using puromycin to link genetic information to proteins and/or peptides. We discuss the application of mRNA display to engineer new proteins, peptides, and drug-like peptides and efforts to use these new molecules as tools for chemical biology, molecular imaging, and therapy. Finally, we highlight recent technological advances to improve mRNA display, including increasing speed and depth of post-selection analysis.

mRNA display is an elegant solution to the display problem as it involves simply linking a protein to its encoding mRNA.4 This is accomplished by appending puromycin to the 3’ end of an mRNA via a molecular spacer (Figure 2). Puromycin is an antibiotic that mimics the 3’ end of an aminoacylated tRNA (Figure 3) and acts as a bridge between mRNA and protein. The resulting fusion of mRNA and protein (i.e., an mRNA-protein fusion) generates a molecular “Rosetta Stone,” allowing the sequence of the peptide to be recovered by reverse transcription/PCR of the linked nucleic acid followed by DNA sequencing.

Figure 2. mRNA-peptide fusion formation.

(A) puromycin-ligated mRNA is translated by the ribosome (pink) in vitro. (B) When the ribosome reaches the mRNA/DNA junction, puromycin enters the A site of the ribosome, forming a covalent bond with the C-terminus of the nascent peptide, generating an mRNA-peptide fusion. (C) The mRNA strand is reverse transcribed into cDNA, enabling sequence amplification and identification, and eliminating RNA secondary structure.

Figure 3. Structures of Tyrosyl tRNA and puromycin.

Puromycin is a structural mimic of the 3’ end of aminoacylated tRNA. The differences between puromycin and tyrosyl tRNA are highlighted in red

A typical mRNA display in vitro selection cycle is shown in Figure 4. A DNA library, obtained from synthetic or natural sources, is first transcribed into mRNA. A linker containing puromycin is attached to the 3’ end of the mRNA and the resulting mRNA-puromycin template is translated in vitro. The resulting mRNA-protein fusion is typically reverse transcribed into a cDNA/mRNA duplex, which prevents the inadvertent selection of RNA aptamers. The pool of mRNA-peptide fusions is then subjected to a selective step, typically binding to an immobilized macromolecular target, which separates functional and non-functional sequences. Non-functional sequences are washed away and cDNA from functional sequences is amplified by PCR, generating a dsDNA library enriched in functional sequences. This library can either be used for more rounds of selection or sequenced to identify the functional protein sequences.

Figure 4. mRNA display cycle.

A library of dsDNA consisting of a 5’ promoter and 5’ untranslated region (UTR) is PCR amplified and transcribed into an mRNA library which is subsequently ligated to a puromycin-linker. The ligated mRNA library is then translated in vitro to form a library of mRNA-peptide fusion molecules. The mRNA-peptide fusion library is then reverse transcribed and panned against the target of interest to isolate functional sequences. PCR amplification regenerates the DNA library, which can be used for another round of selection or sequenced to identify functional peptides.

2. mRNA Display

2.1. mRNA Display Mechanism

All mRNA display formats require a DNA library with a 5’ promoter for transcription (e.g., for T7 RNA polymerase), a 5’ untranslated region (UTR) for the preferred cell-free translation system, start codon, open reading frame (ORF; usually containing a mix of fixed and random codons), and a 3’ UTR used for RT-PCR amplification. Libraries can be constructed to include an affinity purification tag (e.g., His tag, FLAG tag, hemagglutinin (HA)-tag, etc.) or chemical moiety for purification.

The in vitro translation systems used in mRNA display can be bacterial, eukaryotic, or a synthetic reconstitution of selected proteins from either source. The current model for fusion formation involves translation of an mRNA template until the ribosome reaches the RNA/DNA junction and stalls. There, puromycin enters the A-site and the peptidyl transferase activity of the ribosome catalyzes the formation of an amide bond between the primary amino group of puromycin and the C-terminus of the nascent protein chain in the P-site (Figure 2). This fusion formation reaction must occur “in cis,” i.e., an mRNA template must be fused to the protein that it encodes. A “trans” reaction – an mRNA fused to a protein translated by another mRNA – would result in a mixed message, preventing directed evolution. Early experiments showed that translation of two templates of different lengths resulted in only the correctly fused products. No mixed products were observed, supporting a cis fusion formation model.4, 13 Experiments optimizing the linker length between mRNA and puromycin also support a model for cis fusion formation. Increasing the linker length beyond ~30 nucleotides (which roughly spans a distance corresponding to that between the mRNA decoding site and the peptidyl transferase center) results in decreased fusion formation efficiency, suggesting that trans products would be unlikely to form.13 Lastly, many new ligands have been engineered using mRNA display, which would not be possible unless the fidelity of fusion formation between mRNA and protein within the same ribosome is preserved.

Ribosomal stalling at the mRNA/DNA junction also seems to play an important role in fusion formation. In a study to determine where puromycin can enter the ribosome, Starck et al. used a biotinylated derivative of puromycin to pull-down puromycin-terminated products.14 Rather than observing random puromycin entry at many sites in the sequence, this group observed that puromycin only terminated translation at distinct sites in the protein sequence. This observation suggested that these sites corresponded to ribosomal pause points during translation of the mRNA, supporting the idea that a pause during translation in mRNA display is important for puromycin entry. When the mRNA template is linked to puromycin through a DNA linker (typically poly-dA), the DNA-RNA junction provides an efficient pause site.13 In TRAP display (Transcription–Translation coupled with Association of Puromycin linker), a UAG stop codon is placed at the 3’ end of the ORF to induce ribosomal pausing.15

2.2. mRNA Display Variants

Several variants of mRNA display have been developed, all of which use puromycin as the means to link mRNA and protein (Figure 5). These technologies include Profusion™,16 in vitro virus (IVV) display,17 cDNA display,18 and TRAP display.15 The main difference in these variants lies in the structure of the puromycin linker that bridges mRNA and protein. The original mRNA display linker consisted of a simple deoxyadenosine spacer (5’ – dA27dCdCP – 3’, where P = puromycin),4 which was trademarked as Profusion™ technology.13, 16 Subsequent optimization experiments showed that increased flexibility in the linker, introduced via incorporation of polyethylene glycol spacers (Spacer 9), resulted in higher rates of fusion formation between mRNA and translated protein.13 In both cases, these puromycin linkers were ligated to mRNA using T4 DNA Ligase in the presence of a DNA splint (Figure 5A).19 Alternatively, the puromycin linker can be added to the mRNA using photo-crosslinking by incorporating a psoralen20, 21 (Figure 5B) or a 3-cyanovinylcarbazole nucleoside (CNVK).22 The advantage of psoralen ligation is that the ligated product can be directly translated without a gel purification step, whereas splint-mediated ligation requires gel purification to eliminate the DNA splint that can lead to RNase H-mediated degradation of the mRNA.23 Similarly, a branched puromycin linker containing both psoralen and a reverse transcription primer (Figure 5C) can be used to create a cDNA-protein fusion or a dsDNA-protein fusion, which both show higher stability versus mRNA-protein fusions in environments where RNase is present.20

Figure 5. mRNA Display Variants.

All mRNA display systems use puromycin to conjugate a protein to its encoding mRNA. How the puromycin linker is attached to the mRNA differs between mRNA display variants. DNA is represented by grey lines while RNA is represented by black lines. (A) Classical mRNA display uses a DNA splint in the ligation between mRNA and the linker. The puromycin linker contains a poly dA stretch to stall the ribosome for puromycin entry and serve as an affinity handle for poly-deoxythymidine (dT) purification after fusion formation. Psoralen mediated photo-crosslinking can also be used to form (B) mRNA-protein fusions or (C) cDNA-protein fusions. (D) In TRAP display, the puromycin linker is not covalently attached to the mRNA and the mRNA 3’ UTR contains a UAG codon to stall the ribosome and enhance puromycin entry. (E) In cDNA display, the puromycin linker consists of four main parts including a ligation site, a restriction site, a reverse transcription primer site, and a biotin site.

The IVV approach to mRNA display was named for an mRNA-protein fusion’s similarity to a simple retrovirus.17 In this system, puromycin is attached to mRNA via a DNA/RNA chimera nucleotide termed a “P-acceptor” and a 105 nucleotide DNA spacer linking protein and mRNA.17 A second generation IVV was generated through simple hybridization of a puromycin linker containing 2’-OMe nucleotides, leading to a non-covalent peptide fusion.24 A more recent version, TRAP display, uses a non-covalent hybridized DNA-containing puromycin linker and incorporates a UAG codon into the mRNA to stall the ribosome and enhance puromycin entry (Figure 5D).15 This format was found to reduce the time required for a single selection round to <3 hours.

Several other technologies using splint-less ligation methods have also been developed. A Y-ligation method uses a puromycin linker that hybridizes to the mRNA, after which short single-stranded sections of the mRNA and linker are ligated in the presence of T4 RNA ligase to form a small single-stranded loop.25, 26 This strategy has been further developed to synthesize cDNA-fusions using a linker similar to the branched psoralen linker described above, except that instead of using psoralen crosslinking, the Y-ligation strategy is used.18, 27, 28 This branched Y-ligation linker contains a reverse transcription primer for generation of a covalently linked cDNA-peptide fusion. In some versions of this technique, this linker also incorporates a restriction site and biotin group, allowing for immobilization of the ligated mRNA followed by solid-phase translation and reverse transcription (Figure 5E). This approach effectively eliminates the need for intermediate purification steps27 and the subsequent cDNA-peptide fusions can be released from the solid phase by restriction enzyme cleavage.18 A recent well-controlled study comparing mRNA display and cDNA display showed that both mRNA and cDNA display are comparable in enriching functional sequences, though mRNA display showed higher enrichment versus cDNA display, possibly due to higher non-specific binding of the cDNA display fusions.29 However, this effect was only seen when gel purification steps were included during library synthesis.

3. Advantages and Disadvantages of mRNA Display

As with any technology, mRNA display has a number of inherent advantages and disadvantages that should be considered. As an entirely in vitro technology, virtually any library can be constructed ranging from a totally random peptide library to those based on a complex protein scaffolds (e.g., antibodies. The covalent link between mRNA and protein allows a wider range of temperatures, buffers, binding conditions, and incubation times during selection compared to ribosome display, where a non-covalent ternary complex must be maintained throughout the selection. Flexibility in buffer conditions is also an advantage of in vitro selection systems, as display systems involving cells, such as yeast display (YD) or E. Coli display (ED), require conditions that keep cells viable and intact. Finally, the covalent link between peptide and protein, coupled with the minimized peptide-nucleic acid structure of the mRNA-protein fusion allows for the possibility of post-translational chemical modification which dramatically enhances the potential chemical complexity of mRNA display libraries.

mRNA display also has a number of disadvantages. One general limitation of many mRNA display selections (and all selections using biochemically purified targets) is that targets are often presented on a solid-phase support, which may not recapitulate the conformation of the target in a native biological context. For example, if a target can adopt multiple conformations, not all of these conformations may be sampled on the solid support. Also, by selecting against an immobilized target, in vitro selections partition molecules based purely on their binding affinity or binding kinetics (i.e., KD, kon, and/or koff) as it is difficult to devise a method to partition molecules based on their activity. As a result, some selections result in molecules that can bind to a target in vitro, but show no activity in biological systems or cannot bind the target in a biological context (see, for example, Sections 5.2.2, 5.2.4, or 6.2.1). An alternative strategy is to overexpress a target on the cell surface and select for binding against these cells. However, ensuring that the selection results in ligands to the target of interest is often difficult, even if cells without overexpressed target are used as a negative selection step. Lastly, the mRNA portion of an mRNA-protein fusion can help to solubilize the linked protein, allowing marginally soluble proteins to be selected. As a result, downstream expression or synthesis of the selected proteins or peptides can be challenging.

3.1. Diversity

mRNA display4 and ribosome display libraries30 are effectively the largest peptide libraries that are experimentally accessible. While it is physically possible to construct even larger libraries, such efforts are impractical requiring kilograms of genetic material. Up to 1015 unique sequences can be synthesized using mRNA display (Figure 6) and even a single copy of a functional sequence can be PCR amplified following in vitro selection. In contrast, in vivo display technologies, such as PD, are typically limited to a practical diversity of approximately 109 sequences owing to the obligate in vivo transformation step and resulting loss of diversity. mRNA display libraries are orders of magnitude larger than the immune system (~109 unique molecules), one-bead-one-compound (OBOC) libraries31 (~107 unique molecules), and non-ribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) or polyketide synthetase (PKS) libraries32, 33 (~103 unique molecules).

Figure 6. Biological display platforms including one-bead-one-compound (OBOC), yeast display (YD), phage display (PD), E. coli display (ED) and mRNA display libraries.

The platforms are compared based on their complexity and the maximum dissociation constant (KD,max) that can be achieved for the highest affinity ligand for a given library complexity. Ribosome display libraries have the same complexity as mRNA display. KD,max values were roughly estimated according to Reference 34 (not to scale).

In general, library size is directly correlated with the probability of obtaining a functional sequence of desired affinity.34, 35 A theoretical study by Rosenwald36 found that the degree of binding site complementarity is correlated to the size and complexity of the ligand, e.g., the more topologically complex the ligand, the more interactions it can make with a topologically complex binding site, such as a protein surface. There is also a correlation between the initial diversity of the library and the probability of obtaining a ligand of a given dissociation constant (KD), and for every log of increased complexity in the starting library, a log of decreased KD is obtained. An example of the effect of library size on affinity is shown by comparing selections against streptavidin using mRNA display and PD. Using mRNA display, Wilson et al. discovered 20-amino acid peptide sequences that bound to streptavidin with dissociation constants ranging from 110 nM to as low as 2.4 nM.37 In comparison, a PD selection against streptavidin resulted in a single peptide that bound with 13 μM affinity.38, 39 While different libraries were used in these selections, these results suggest that large mRNA display libraries may yield higher affinity compounds than PD.

Despite the advantages of highly diverse libraries, there are some notable drawbacks. For example, if a high diversity library is constructed so that there is only one copy of each sequence, it is possible that functional sequences could be lost stochastically in the first round of selection. Therefore, the copy number of each random sequence in the library should be carefully considered.40 In addition, because there are more total sequences in a high diversity library, more non-functional sequences must be removed in order to identify the functional sequences. This implies more rounds required for convergence in mRNA display (4 to >10) as compared with PD (generally, <3). In addition to requiring more time, additional selection cycles can result in contamination or selection failure. In the end, high diversity display libraries generated by selection platforms like mRNA display offer the potential for identifying high affinity compounds which must be considered alongside the increased selection time and technical difficulty.

3.2. Biases in Display Technology

All display technologies suffer from some bias and no display technology will generate a truly unbiased library. In a translation-based in vitro selection (e.g., mRNA display, ribosome display, PD, YD, etc.) the codon bias of the translation machinery, mRNA secondary structure, and post-translational processing are well-known sources of library bias.41, 42 Finally, differential efficiencies in the amplification and transcription of the fused genetic material may also introduce significant bias into the final protein library.

In PD, proteins are displayed on the surface of a micrometer-long bacteriophage with a negative surface charge [MW > 1 X 108 Da] raising the possibility of non-selective target binding through interactions between the phage and target. In ribosome display, the ribosome, mRNA, and translated peptide form a stable ternary complex. Although smaller than phage, the ribosome is still a ~2,000,000 Da particle, raising the possibility of steric occlusion and/or non-selective binding driven by the nucleic acid and protein components of the ribosome. In other display technologies, peptide or protein libraries are linked to even larger molecules such as cells (ED or YD) or plasmids. mRNA display, on the other hand, only contains mRNA linked to peptide or protein,43 and is the minimal set of elements needed for protein or peptide display. The effect of the display scaffold on the quality of selection results or scaffold bias has been discussed elsewhere44, 45 and is an important source of background binding and false-positive hits.

Display technologies that require an in vivo transformation step (e.g., PD, YD, etc.) introduce additional library biases. In the case of PD, peptides are most commonly displayed as fusions with Gene III (5 copies) or Gene VIII (thousands of copies). Multiple copies of a peptide displayed on phage can result in selection for weaker binding peptides due to avidity effects that prevent discrimination between moderate and high affinity clones.46 In mRNA display, proteins are presented in a strictly monomeric context, avoiding avidity effects and allowing the selection of high affinity sequences. The insertion of a peptide or protein into Gene III can also interfere with the infectivity of the phage particle. If phage amplification is biased by a peptide sequence, the abundance of a clone might reflect a clone’s infectivity and amplification rather than its binding to target. Lastly, during the process of phage assembly and export, known biases against certain sequences prevent display of some peptides (e.g., basic peptides).47–49

3.3. Simultaneous Optimization of Multiple Positions

The stepwise optimization of a peptide sequence is a relatively straightforward strategy – starting with a single functional sequence, the best amino acid at a single position is determined and repeated for each position in the sequence. Once the optimal amino acids are known at each position, they are then combined into one sequence. While a stepwise optimization strategy can be successful, it is often difficult to achieve in practice since changing an amino acid can result in unpredictable changes in binding affinity or specificity. One example is a study where Fiacco and co-workers attempted to introduce N-methyl amino acids into a peptide binding to the G-protein, Gαi1.50 Each position in this peptide was systematically substituted for its corresponding N-methyl amino acid, with many substitutions resulting in dramatic increases in protease resistance. However, almost all substitutions resulted in a decrease in affinity and one substitution resulted in a change in binding specificity from Gαi1 to Gα12.

The best amino acid at one position in a sequence can also change depending on the context of the surrounding positions. mRNA display offers a powerful solution for optimization of a sequence since multiple positions of a sequence can be optimized simultaneously. One example is where mRNA display was used to engineer a peptide that could not be achieved through stepwise modifications.51 In this study, the authors developed a macrocyclic peptide that bound Gαi1. Unlike the parental sequence, this peptide contained two N-methyl Alanine residues and was highly protease resistant. However, substitution of either residue with alanine lead to a 100-1,000-fold decrease in protease stability. In a hypothetical stepwise optimization experiment, adding N-methyl amino acids in a stepwise fashion to the original peptide would have resulted in peptides with no increase in stability and these peptides would have been discarded. As a result, it seems highly unlikely that a stepwise optimization strategy could have resulted in the discovery of the selected Gαi1-binding peptide. Furthermore, only 20% of the original natural amino acids of the parental peptide were retained in the selected peptide. This indicates that a leap of about 8 independent steps would have been required in a stepwise modification strategy beginning with the parental peptide and ending at the protease-resistant selected peptide.51

3.4. Simultaneous Optimization of Multiple Properties

An additional advantage of mRNA display is that it can also be used to optimize multiple biophysical properties of a sequence simultaneously. For example, Howell et al., developed a multi-step selection for binding and for protease resistance.52 This was achieved by first incubating an mRNA display library with chymotrypsin, thereby selecting for sequences that were protease resistant, followed by incubation of the library with target. A 100- to 400-fold increase in protease resistance was observed, while still retaining binding for target. Selections for thermostability have also been performed similarly.53 These examples illustrate the powerful ability of mRNA display to optimize properties along multiple fitness axes.

4. Results from mRNA Display Selections

In the ~20 years since its inception, mRNA display has successfully been used to engineer novel ligands against a wide variety of targets. In this section, we review the results of these selections and observe some common themes and results. These selections fall into two broad categories: 1) Protein selections, where the resulting ligands are folded and contain a buried hydrophobic core, and 2) Peptide selections, where no explicit structural constraints or contexts are imposed on the initial library. We will begin with a discussion of selections in the first category where known biological scaffolds (e.g., fibronectin) are partially randomized to generate mRNA display libraries from which folded, functional ligands can be identified. We will then review the selection of linear, natural peptides by mRNA display and their application as chemical tools. We will conclude by surveying the recent literature describing the use of cyclization and non-proteogenic amino acids to generate non-ribosomally synthesized peptide (NRSP)-like mRNA display libraries and their application to the selection of drug-like peptides. We note that while mRNA display libraries can be constructed from cDNA, we refer the reader to other publications for more information.54, 55

5. Biological Scaffolds in mRNA Display

There is great interest in engineering novel proteins for a number of applications, including therapeutics,56 imaging agents,57 diagnostics,58 and tools for biological/biochemical research. One difficulty encountered when engineering proteins is that it is impossible to exhaustively search the entire sequence space of even the smallest proteins. Sequence space is immeasurably large: the number of possible sequence combinations increases by a factor of 20 with each additional amino acid that is added to a protein chain. Thus, even using libraries of 1015 unique molecules, only a maximum of ~11-12 amino acids can be exhaustively searched by in vitro display technologies. As a result, it is often necessary to design and constrain a library to specific regions within the primary sequence. Many protein libraries are based on a protein “scaffold,” which remains constant and acts to support randomized regions that will be selected to interact with a target of interest. Often, the scaffold’s hydrophobic core is kept constant so that randomization of loops or surface residues will not result in unfolding, aggregation, or loss of solubility.59, 60

The choice of scaffold and if a scaffold is even needed should be carefully considered before embarking on an mRNA display selection. Matching the biophysical properties of a potential scaffold to the final intended end application is important, as each scaffold has both advantages and disadvantages. In general, scaffolds are thought to result in higher affinity ligands relative to peptides. Peptides are generally unstructured in solution and must pay a large entropic penalty upon binding resulting in weaker binding affinities.61 In contrast, random regions within a scaffold are comparatively fixed in place by the scaffold topology and lose less conformational entropy upon binding, resulting in improved affinity.62 Structured proteins are also generally more resistant to proteolytic degradation relative to linear peptides making them an attractive starting point for in vivo applications.63

These advantages must be weighed against the disadvantages of protein scaffolds. In mRNA display, longer proteins have a reduced efficiency of fusion formation,64 which can increase the technical difficulty of successfully completing an mRNA display selection and result in decreased effective library sizes. Likewise, scaffold-based proteins will be selected for both foldedness and function, which can potentially reduce the number of winning sequences. For example, Keefe and Szostak estimated that ATP-binding proteins selected from a random 80-mer library occurred at frequency of roughly 1 in 1011 molecules.65 They hypothesized that this surprising low frequency of ATP binders could have been due to the difficulty of forming a folded protein with a buried hydrophobic core from a totally random library. Additionally, longer random protein libraries often have increased chances of stop codons or frameshifts due to library construction, increasing the probability of aborted translation products.66 Lastly, larger protein scaffolds, such as the fibronectin and single chain fragment variable (scFv) domains, may suffer from reduced tissue/tumor penetration due to poor extravasation rates and rapid systemic clearance.67

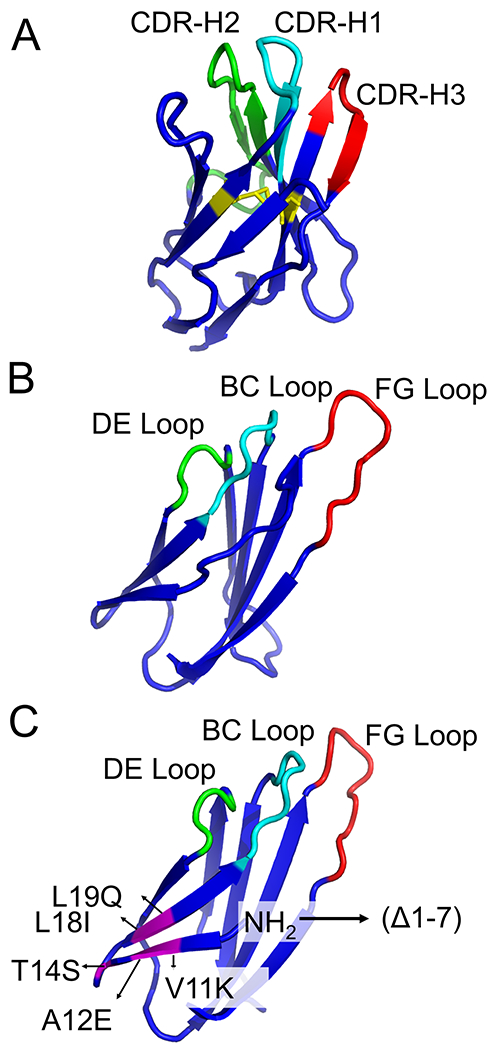

In mRNA display, several scaffolds have been used in successful in vitro selections including nanobodies,68 SH3 domains,69 fragment antigen binding (Fab) domains,70 scFv domains, and fibronectin71 scaffolds. Of these, the two most common scaffolds are scFvs (~27 kDa) and fibronectin-based scaffolds (~10 kDa) (Figure 7). While both scaffolds are substantially larger than small peptides (~1-2 kDa), they are still approximately 1/5 to 1/10 the size of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), facilitating binding to molecular crevices that antibodies are too large to access. Despite their smaller size, however, they are still capable of modulating protein function and can be more effective at blocking protein-protein interactions than small peptides.72, 73

Figure 7. Schematic of various mRNA-protein fusions.

(A) A 13-amino acid peptide attached to its encoding mRNA. Randomized regions (for mRNA and peptide) are red. (B) A fibronectin fusion with three randomized loops (BC (cyan), DE (green), and FG (red) attached to its encoding mRNA. Random regions in the mRNA are colored while the constant scaffold is dark blue. (C) An scFv attached to its encoding mRNA. Constant scaffold regions are dark blue while CDRs are colored accordingly.

5.1. Antibody Scaffolds

Antibodies are the gold standard for protein ligands and can bind to protein targets with high affinities and specificities. mAbs are among the most promising therapeutics and have revolutionized the pharmaceutical industry, with up to $200 billion in annual revenue predicted by 2022.74 Although hybridoma technology has been effectively used to generate thousands of new mAbs,75 this technology is over 40 years old and has a number of disadvantages. mAb production is laborious and little control can be exerted over the binding conditions and the stringency under which a mAb is generated, potentially resulting in mAbs with poor affinity and/or selectivity.76 mRNA display using antibody and antibody-like scaffolds is an attractive alternative for generating novel antibodies and antibody-like compounds, as the larger library size (Figure 6) and precise control over selection conditions can yield antigen-binding ligands with antibody-like affinity and specificity. In the following section, we review the use of mAb scaffolds (antibody) as well as Fab and scFv scaffolds (antibody-like) in mRNA display experiments.

Structurally, immunoglobulin variable domains (Fv) consist of two sandwiched β-sheets. Antigen specificity is conferred by loops that connect β-strands called complementarity determining regions (CDRs). CDRs vary with each antibody and comprise the antigen-binding surface.77 In mRNA display, as with the immune system, CDR loops are commonly randomized in order to create antibody and antibody-like libraries.71 Antibodies are composed of variable heavy (VH) and variable light (VL) chains, which contain both intermolecular (between VH and VL chains) and intramolecular (within a VH or VL chain) disulfide bonds.78 Because these disulfide bonds potentially make antibody folding and assembly difficult, mRNA display methods have been developed to increase the folded fraction of the library.79 Alternative translation conditions can also mitigate folding issues. For example, the PURE (Protein synthesis Using Recombinant Elements) system was used to select a disulfide-containing scFv targeting insulin.80 Reticulocyte-based systems have used protein disulfide isomerase and other disulfide-forming enzymes to translate and properly fold antibodies.81 Lastly, assembling an antibody that retains VH/VL pairing throughout a selection is difficult because the chains are encoded separately. Despite a method using emulsion PCR to retain Fab fragment VH/VL pairs,70 Fab fragments are uncommon in mRNA display.

For the past 20 years, the scFvs have been most frequently used antibody scaffold in mRNA display. The scFv scaffold balances the challenges associated with in vitro library development and expression (e.g., incorporating disulfide bonds) with the benefits of the antibody scaffold. scFvs are derived from VH and VL chains of antibodies where the chains are linked by glycine-serine repeats (Figure 8). Encoding the VH/VL pairs in a single protein chain simplifies mRNA display library construction and selection, making scFvs the preferable scaffold for antibody selection.

Figure 8. Antibody based scaffolds (scFv and Fab) compared to full IgG antibody.

(Fv: immunoglobulin variable domain, Fc: fragment crystallizable domain, Fab: antigen-binding fragment, VH: variable heavy, VL: variable light, CL: constant light, CH: constant heavy, scFv: single chain fragment variable)

mRNA display using scFv scaffolds has resulted in several successful selections. A selection against Mouse Double Minute 2 homolog (MDM2) and p53 combining Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) and an off-rate selection converged after two rounds to yield scFvs with 4.3 nM and 12 nM KD values, respectively.82 scFv selections using mRNA display were also performed against Tumor Necrosis Factor α Receptor (TNFR),83 fluorescein (0.95 nM KD),84 and Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor κB (RANK).85

While scFvs may be better suited for mRNA display, full-length mAbs that include both the Fv and the Fc (Fragment crystallizable) constant regions are important for therapeutic purposes. These regions mediate antibody-dependent cell-mediated toxicity (ADCC), activation of complement, and are responsible for long serum half-lives.86

Unfortunately, as discussed above, full-length mAbs are extremely challenging to adapt to mRNA display library design and selection workflows. One strategy to create full-length mAbs is to first perform an mRNA display selection with an scFv library then graft the selected CDR loop sequences onto a full-length mAb scaffold. In one such study, scFvs obtained by mRNA display were used to design over 100 mAbs against 15 antigens.81 However, this strategy is only successful in some circumstances as many of the grafted antibodies showed loss of specificity/affinity. This phenomenon was also observed when scFvs were selected using PD.87, 88 These observations suggest that the scFv scaffold may not present the CDR loops in the same context/structure as an intact antibody.81

5.2. Fibronectin-Based Scaffolds

While antibody and antibody-like scaffolds are leading sources of biological therapeutics, alternative scaffolds are being developed for the next generation of therapeutic proteins.89 Disulfides in antibodies can cause structural heterogeneity and instability due to isomerization/alternative disulfide pairing, interconversion, and/or reduction.90, 91 Antibodies are also unstable in the reducing intracellular environment, making the use of antibodies inside the cell (i.e., intrabodies) more challenging. During mRNA display, disulfide bond-mediated protein folding also poses an additional challenge that can decrease the library complexity and impair selection robustness. As a result, alternative scaffolds that structurally mimic antibody variable chains without disulfide bonds have been developed for use in mRNA display selections. The most common of these is the fibronectin scaffold.

Fibronectin is a large extracellular matrix protein responsible for interfacing cells with the stromal environment.92 Three types of modules or domains (Type I, II, and III) are found in fibronectin and each type contains two anti-parallel β-sheets that form a β-sandwich. Type I and II domains contain disulfide bonds while the Type III domain lacks disulfide bonds, making the Type III domain an attractive scaffold for mRNA display. The 10th subunit of human Fibronectin is a Type III domain (10Fn3) that is widely used as a scaffold in mRNA display (trademarked as Adnectins™ by Bristol-Myers Squibb, or also called “monobodies”).62 Wild type 10Fn3 has several biophysical properties that are attractive for a biological scaffold: it has high solubility (>15 mg/mL), is highly thermostable (Tm >90 °C) even without disulfide bonds,62, 71, 93 and expresses well in bacterial systems (50 mg/L).94 The 94-amino acid 10Fn3 scaffold contains three loops (BC, FG, DE), analogous to nanobodies, which are based on the single variable domain camelid antibody VHH CDRs (Figure 9A and Figure 9B).95 The FG loop is the longest and most flexible of the three loops and is involved in endogenous RGD-mediated binding of wild type 10Fn3 with integrins.92 Randomization of the BC and FG loops does not affect 10Fn3 stability, allowing the BC and FG loops to form a contiguous molecular surface for target binding.62 mRNA display-generated 10Fn3 ligands have been used to as ligands for extracellular proteins in molecular imaging, immune regulation, crystallization, and therapeutic applications.96–98 10Fn3 probes for intracellular targets (intrabodies) have also been developed for dynamic in vivo imaging.99 A comprehensive list of fibronectin-based ligands selected by mRNA display is presented in Table 1.

Figure 9. The tertiary structure of (A) Llama VHH domain (PDB accession number 1TTG), (B) wild-type human 10Fn3 domain (PDB accession number 1HCV) and (C) truncated human 10Fn3 domain carrying structural mutations (PDB accession number 1HCV).

The Llama VHH domain and human 10Fn3 domain show comparable folding into β-sandwiches. (10Fn3: 10th subunit of Fibronectin type III), with the BC, DE, and FG of the 10Fn3 domain resembling the CDR loops of the Llama VHH domain. The complementarity determining regions (CDR) in the VHH domain and the randomized loops in the 10Fn3 domain are showed in green, cyan and red. The disulfide bond formed between cysteines 22 and 92 in the VHH domain is highlighted in yellow. In the truncated human 10Fn3 domain, the mutated residues are highlighted in magenta.

Table 1. Fibronectin Scaffolds Selected with mRNA Display.

Affinities are obtained directly from the corresponding reference and are not normalized for temperature.

| Target | Loop(s) Randomized | Library Diversity* | Rounds Selected | Affinity/ Solubility Maturation | Selected Scaffold Name | Final Loop Sequence(s) | Affinity/IC50/Kinetic Properties | Notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α | BC DE FG |

1012 | 14 | Error-Prone PCR | M12.04 (10Fn3) | BC: SMTPNWP DE: PWAS FG: HRDT (FG truncation) |

KD= 0.02 nM | - | 71 |

| VEGFR2 | BC DE FG |

N/S | - | Thermo-stability optimization | 10Fn3- 159-(A56E) | BC: RHPHFPT DE: LQPP(E) FG: MAQSGHELFT |

KD= 0.59 nM | - | 112 |

| VEGFR2 (KDR); Flk-1 | BC DE FG |

1013 | 6 | Error-prone PCR | VR28-E19 | BC: RHPHFPT DE: LQPP FG: VERNGRHLMTP |

VEGFR2: KD = 0.06 nM Flk-1: KD = 0.34 |

- | 73 |

| Phospho-IκBα | BC FG |

3×1013 | 10 | Error-prone PCR | 10C17C25 (10FnIII) | BC: PASSRWR FG: QQLHQPKWRW |

KD = 18 nM | 1000x more specific for phosphorylated version; Used as intrabody FRET sensor | 113 |

| SARS nucleocapsid protein | BC FG |

1012 | 6 | - | Fn-N22 | BC: LNMWYNV FG: KRSFWSKSAG |

KD = 1.7 nM | Used as Intrabody | 114 |

| EGFR; IGF-1R (bispecific EI-tandem Adnectin) | BC DE FG |

1013 | 4 | - | EI-tandem Adnectin |

EGFR: BC: DSGRGSYQ; DE: GPVH; FG: DHKPHADGPHTYHES IGF-IR: BC: SARLKVAR DE: KNVY FG: RFRDYQ |

EGFR: KD = 10.1 nM IGF-IR: KD = 1.17 nm |

- | 72 |

| IL-6 | BC FG |

1012 | 4 | CFMS | eFn-4B02 | BC: GNGGPLV FG: HAFSGRVAVI |

KD = 21 nM | - | 115 |

| EGFR | BC DE FG |

N/S | - | - | Adnectin1 (EGFR) | BC: DSGRGSY DE: GPVH FG: DHKPHADGPHTYHES |

IC50= 50 nM KD = 2 nM |

IC50 was determined based on inhibition of EGFR phosphorylation | 96 |

| IL-23 | Adnectin 2 (IL-23) | BC: EHDYPYR DE: KDVD FG: SSYKYDMQYS |

IC50= 1 nM KD = 2 nM |

IC50 was determined based on IL-23 receptor competition | |||||

| IgG (Fc) | BC FG |

109 | 1 | CFMS/HTS | eFn-anti-IgG-1 | BC: PATTYTL FG: PCNQCQLRPN |

KD = 28 nM | - | 116 |

| MBP | eFn-anti-MBP-2 | BC: QAPHLFV FG: QFMYLLLPGR |

KD = 130 nM | ||||||

| Human/ mouse DC-SIGN | BC FG |

1012 | Mouse: 3 Human: 4 |

- | eFn-DC6 | BC: PQPWLQV FG: YLPLTYGHYR |

Human: KD = 19 nM; Mouse: KD = 133 nM |

- | 102 |

| PSD-95 and Gephyrin | BC FG |

1012 | PSD-95: 6 Gephyrin: 7 |

- | FingRs | - | - | Used as Intrabody | 117 |

| CAMKIIα | BC FG |

1012 | 7 | - | CAMKIIα FingR clone 1 | BC: IHHAKEI FG: TVSFAWKRVL |

- | Used as intrabody | 118 |

| PXR Ligand Binding Domain (To compete with SRC-1) | BC DE FG |

N/S | - | - | - | BC: PPPYYEGVTV DE: PYWTET FG: EMYPGSPWAGQVMDIQP |

KD = 11 nM | - | 97 |

| IL-23 | BC DE FG |

1012 | - | - | ATI-1221 anti-mouse IL-23p19 Adnectin | - | Parent: KD = 0.245 nM PEGylated form: KD=0.234 nM |

- | 103 |

| H-RAS (G12V) | BC FG |

1012 | 6 | 5 additional rounds for maturation | RasIn2 | BC: SIVFGKHD FG: FRWPKRRLVR |

KD = 120 nM | - | 119 |

| CD4 | NP1 library: BC, DE, FG with N-terminal and flanked randomized residues WS1 library: CD strand FG loop with randomized flanked residues |

N/S | 6 | Stringency and off-rate improvement | Adnectin 6940_B01 | CD strand region: HSYHIQYWPLGSYQRYQVFS FG loop and flank: EYQIRVYAETGGADSDQSFG WIQIGYRTEPES |

KD = 3.9 nM | - | 107 |

| PD-L1 | - | N/S | - | - | Adnectin BMS-986192 | - | KD = 0.035 nM | - | 99 |

| gp41 (N17) | BC DE FG |

N/S | 7 | 3 additional rounds for optimization | Adnectin 6200_A08 | BC: EYKVHPY DE: FVLE FG: VDS |

Parent Adnectin: KD = 0.8 nM | Tethered CD4 and gp41 Adnectin to inhibit HIV (EC50= 37 pM) | 108 |

| Glypican-3 | BC DE FG |

5.3 × 1013 | 7 | - | A2-tub | BC: SDDYHAH DE: GEHV FG: YDAEKAATDWSIS C-terminus: NYRTPC |

KD = 8 nM | - | 110 |

| α211 subunit of α1-Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor | BC FG |

≤1014 | 5 | Off-rate optimization/ heat and protease stability selection | α1-FANG3 | BC: PSMFGHV FG: WIHLKWLTNF |

KD = 0.67 nM | - | 53 |

| Subunit S1 of SARS-CoV-2 | BC FG |

3x1013 | 6 | Clone 6 monobody | BC: GGDYVGYY FG: TYNGPWIYGYEEI |

KD = 0.76 nM | 111 |

Refers to the stated complexity of the library in the original reference. N/S is used if this value is not provided.

(Abbreviations: CFMS (Continuous flow magnetic separation); HTS (High throughput sequencing))

5.2.1. Initial mRNA Display Selections with the 10Fn3 Scaffold

In 1998, Koide et al. designed the first 10Fn3-based scaffold library.62 Using PD, they isolated a single clone with moderate specificity and affinity towards ubiquitin (reported IC50: 5 μM). The first mRNA display selection using an 10Fn3 scaffold was against Tumor Necrosis Factor α (TNFα).71 In this selection, three libraries were constructed: one library randomizing the FG loop only, one randomizing the BC and FG loops, and one randomizing the BC, DE, and FG loops. Using these three libraries, the selection yielded ligands with KD values ranging from 1 to 24 nM, with over 90% of the clones originating from the third, three-loop library. Subsequent affinity maturation that included random mutagenesis, high temperature incubations to select for protein stability, and extended washing for increased binding affinity, resulted in improved variants with KD values as low as 20 pM. Biophysical characterization of the two winning sequences showed they were monomeric, could be expressed in E. coli, and were resistant to proteolytic digestion at room temperature. However, the selected molecules showed lower thermostability than wild type 10Fn3 and suffered from low to moderate bacterial expression efficiencies.71 The authors hypothesized that the higher affinity and larger number of functional sequences resulting from the selection (~100 total) was due to the larger mRNA display library (1012 independent sequences) versus the less diverse PD library (108) in the original ubiquitin selection.

A second study described extensive biophysical and biochemical characterization of the fibronectin scaffold. In this study, Olson and co-workers synthesized a library similar to the two-loop library above, where the DE loop was kept constant while the BC and FG loops were randomized. The first seven amino acids of the 10Fn3 scaffold were removed in this library because structural analysis showed these N-terminal residues threaded between the randomized BC and FG loops, potentially affecting binding. Supporting this hypothesis was the observation that removal of the first eight residues of 10Fn3 fibronectins selected against Kinase insert domain receptor (KDR)/vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR2) improved binding by ~3-fold on average.73 The wild type and Δ1-7 mutant were equally stable in unfolding studies, suggesting that these seven N-terminal amino acids were not important for folding and stability. The authors also determined the folded fraction of the library by screening clones from the 10Fn3 library expressed with Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) fused to its C-terminus. GFP fluorescence is highly dependent on the solubility and tertiary stability of the fused N-terminal protein.100 GFP reporter fluorescence showed that ~45% of the naïve fused library was correctly translated in-frame and lacked stop codons. These data supported the hypothesis that the fibronectin library is able to tolerate loop randomization and can display these random loops without significant effects on stability or folded structure.94

5.2.2. Targeting Extracellular Proteins with 10Fn3 Selections

Extracellular proteins are a common target in 10Fn3-based mRNA display selections. Each selection described below employed slightly different selection pressures and antigen presentation strategies. Engineered 10Fn3 scaffolds termed Adnectins were selected against interleukin-23 (IL-23) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR).101 Both Adnectins bound their targets with a KD of 2 nM and inhibited either EGFR receptor phosphorylation (IC50 = 50 nM) or IL-23/IL-23R binding (IC50 = 1 nM).96 Co-crystallization of the Adnectins with their targets revealed they bound epitopes distinct from previously identified mAbs, suggesting their small size allowed them to bind to concave, antibody-inaccessible sites while still being able to sterically hinder receptor/agonist interactions.96 The ability to recognize distinct epitopes from mAbs could make fibronectin scaffolds useful in situations where critical protein surfaces cannot be effectively targeted with larger scaffolds.

The dendritic cell-specific ICAM3-grabbing non-integrin receptor (DC-SIGN) was targeted with a fibronectin mRNA display library containing two random loops. The authors hypothesized a DC-SIGN specific fibronectin would enable targeted delivery of antigens to dendritic cells, promoting a more effective immune response. After seven rounds of selection, several fibronectin ligands were obtained, with the most promising 10Fn3 ligand showing a reported KD of 19 nM.102 While all fibronectins were able to bind to recombinant DC-SIGN in biochemical assays, only one sequence bound to DC-SIGN expressed on the surface of cells. It is unclear if many of these sequences did not bind because the binding epitope for the non-functional sequences is occluded on the cell surface. These results highlight the utility of having multiple potential ligands to screen for function in downstream experiments. Lastly, when this DC-SIGN specific fibronectin was coupled with vaccine antigens, the fibronectin-antigen conjugate resulted in greater DC antigen presentation and enhanced CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell activation.102

Bispecific biologics were also generated using 10Fn3 mRNA display selections. Adnectins were first engineered separately against EGFR and insulin-like growth factor-I receptor (IGF-IR). Optimized 10Fn3 clones were integrated into a bispecific construct through a glycine-serine cross-linker to create the EI-Tandem Adnectin that inhibited EGFR and IGF-IR phosphorylation with IC50 values from 0.1 to 113 nM and triggered receptor degradation. A polyethylene glycol (PEG)ylated version of EI-Tandem increased serum half-life while only minimally impacting affinity for either target. In a preclinical nude mouse model of pancreatic cancer where EGFR and IGF-IR are overexpressed, administration of the EI-Tandem Adnectin resulted in significant tumor growth inhibition.72 Notably, the EI-Tandem Adnectin was more effective than co-administered monomeric EGFR and IGF-IR Adnectins, indicating that bispecific presentation is crucial for enhanced effectiveness. The EGFR binding Adnectin was also adapted for chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) adoptive T-cell transfer.98 This Adnectin demonstrated comparable effectiveness when compared to established scFv molecules derived from EGFR binding mAbs, indicating the 10Fn3 scaffold could provide a simpler and faster route to produce a larger repertoire of CARs.98 Adnectins have also been combined with traditional mAbs or other biologics. For example, a mouse IL-23 specific Adnectin (PEGylated Adnectin KD for IL-23 = 234 pM) was combined with an IL-17 mAb and/or IL-17 decoy receptor.103 Administering both Adnectin and mAb resulted in decreased inflammation with an enduring response in an autoimmune mouse model that was more effective than administration of either inhibitor alone.103

Adnectins targeting immune checkpoint ligands have been developed as well. Notably, the Adnectin BMS-986192 binds programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) with a KD = 35 pM even after radiolabeling with 18F.99 18F-BMS-986192 has also been shown to discriminate dynamic levels of PD-L1 in murine xenograft models,104 and was used to assess PD-L1 expression in patients with advanced stage non-small cell lung cancer.105 Alternative radiolabeling (68Ga chelation) was also successful in preclinical mouse models.106 Adnectins were also developed to inhibit human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection by binding to CD4 (KD = 3.9 nM).107 In one study, a gp41-binding Adnectin was tethered to a CD4-targeted Adnectin, resulting in enhanced inhibition of HIV replication (EC50 = 37 pM).108 Mutagenesis and addition of a membrane fusion blocking peptide further improved the bispecific Adnectin.109

A two-loop fibronectin library was used to develop ligands against the extracellular domain of the α1-Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor. 53 These ligands, called FANGs (Fibronectin Antibody-mimetic Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor Generated ligands) were selected under conditions to improve thermostability (by incubating at 65 °C), protease resistance (by incubating with Proteinase K), and improved affinity (through selection for sequences with slower off-rates). As a result, these FANGs were highly thermostable and bound to the α211 subunit of α1 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (KD = 670 pM) with the receptor in monomeric and heteropentameric forms in cell culture.53 One of these fibronectins, α1-FANG3, was able to compete directly with the bungarotoxin for nicotinic acetylcholine receptor binding.53

Engineered fibronectins have also been used as targeting agents to deliver cytotoxic drugs in the form of fibronectin-drug conjugates.110 Pharmacokinetically, the smaller size of Adnectins (~10 kDa) results in much faster clearance than antibodies, which could expand the therapeutic window by reducing cytotoxic exposure to normal tissue. In order to test this hypothesis, Lipovsek et al. first engineered an Adnectin targeting Glypican-3, which is overexpressed on hepatocellular carcinoma cells. This Adnectin was then site-specifically conjugated to the cytotoxic drug tubulysin via a C-terminal cysteine on the Adnectin. Conjugation of tubulysin had little impact on Adnectin binding (KD = 8 nM). The group observed that the drug conjugate was effective at the xenograft tumor site, but was cleared rapidly through the kidneys, limiting systemic toxicity. Although this result supports the hypothesis that Adnectin-drug conjugates might display more favorable therapeutic safety profiles relative to antibodies, further studies will be necessary to show this in the clinic.110

Biologics targeting the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2; the virus that causes COVID-19) were rapidly developed in wake of the pandemic using TRAP display. In this study, a fibronectin library with randomized BC and FG loops was used to target the S1 subunit of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein that contains the receptor binding domain (RBD).111 In the first round of selection, the authors added mRNA coding for the fibronectin library with a puromycin linker instead of the typical TRAP display protocol (where a DNA library is added and transcription/translation occur simultaneously) in order to increase the diversity of the library. In subsequent rounds, TRAP display was used to increase the speed of the selection. Within four days, 10FN3 sequences that bound to the S1 subunit with single-digit nanomolar to sub-nanomolar KD’s were obtained. Several clones were able to block the interaction between the RBD domain of the spike protein and ACE2, some at concentrations as low as 10 nM. The set of clones that were tested also bound to three epitopes and 16 different combinations were suitable reagents for a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Clones also inhibited S1 subunit proteolytic conversion and were able to capture virions from patient nasal swabs. Finally, one clone was able to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 infection in a cell-based assay as a monomer (0.5 nM IC50) or as a tandem dimer (0.4 nM IC50). This work demonstrates that mRNA display-based selections can be used to discover new affinity reagents in exigent public health emergencies.

5.2.3. Clinical Translation of 10Fn3/Adnectin Biologics Targeting Tumor-Promoting Receptors

Fibronectin molecules selected via mRNA display have been translated to the clinic. An Adnectin targeting VEGFR-2 has advanced the furthest along the translational pathway, ending in a Phase 2 clinical trial. Several strategies were used to develop anti-VEGFR-2 10Fn3 scaffolds. Using a combination of mRNA display, affinity maturation and site-directed mutagenesis, an exceptionally stable 10Fn3 derivative capable of binding VEGFR-2 with a 13 nM KD was engineered.112 Stability of the Adnectin was sacrificed in favor of enhanced binding affinity, which was improved by >40-fold through additional screening. Based on these two molecules, a third 10Fn3 scaffold was designed that exhibited a combination of high affinity (KD = 0.59 nM) and improved stability (Tm = 53 °C).112 The dissociation constant was later improved by modifying the FG loop, achieving KD values as low as 0.06 nM. These anti-VEGFR-2 Adnectins were screened against both human and murine VEGFR-2 to ensure that selected Adnectins would bind to VEGFR-2 from both species. This strategy allows the same molecule to be used in mouse preclinical studies and clinical human trials, potentially simplifying translation. These Adnectins significantly inhibited VEGF-mediated cell proliferation in a dose dependent manner.73

CT-322/BMS-844203, a PEGylated anti-VEGFR-2 10Fn3 derivative with a KD of 11 nM, was tested in pre-clinical animal models.120, 121 CT-322 entered the clinic with the goal of blocking angiogenesis in a variety of human cancers.122–124 In a Phase 1 trial, CT-322 was well tolerated up to doses of 2 mg/kg/week, however 82% of patients developed anti-drug antibodies that were directed against the engineered fibronectin loops.123 Surprisingly, these anti-drug antibodies did not have an effect on pharmacokinetics or biological function. CT-322 was then tested in Phase 2 trials assessing efficacy in recurrent glioblastoma as a monotherapy and in combination with camptotechin-11 chemotherapy.125 Unfortunately, CT-322 failed to show efficacy as a monotherapy as measured by six month progression free survival, resulting in termination of the study before completion.125 Despite its patient tolerability and potent VEGFR-2 inhibition, the CT-322 Adnectin has yet to find a clinical role.

5.2.4. Targeting Intracellular Proteins with Fibronectins

The term “intrabodies” refers to antibodies that target intracellular antigens. Intrabodies are useful as reagents for live cell imaging or for the recognition of proteins in real-time, allowing researchers to address temporal and dynamic biological questions. Historically, proteins have been monitored in live cells through fluorescent protein tagging (e.g., GFP). However, overexpressing proteins as fusions with fluorescent proteins can perturb biological systems, resulting in protein mis-localization and unintended functional effects rendering the system incapable of addressing nuanced biology.126 Some intrabodies are based on antibody scaffolds which have been engineered to eliminate redox-labile disulfide bonds.127 However, since the 10Fn3 scaffold is disulfide free, it is well-suited for intrabody applications and these intrabodies can be generated by mRNA display.

The first mRNA display derived intrabody was engineered against the phosphorylated form of IκBα, a negative regulator of nuclear factor-κB signaling. After ten rounds of selection using a 10Fn3 library to target a phosphorylated peptide derived from IκBα, a clone was found to bind phospho-IκBα (KD = 18 nM). This clone showed >1,000-fold greater affinity for the phosphorylated peptide versus the non-phosphorylated version.113 To increase solubility and expression, the authors performed iterative rounds of mutagenic PCR followed by a GFP solubility screen.100 This screen resulted in the replacement of solvent-exposed hydrophobic residues with polar ones, greatly enhancing β-sheet formation and bacterial expression. The intrabody was then adapted into a fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) sensor with the goal of monitoring IκBα phosphorylation within cells.113

A second selection by the same group was directed against the SARS nucleocapsid protein (SARS-N). The selection resulted in at least eight fibronectin intrabodies that recognized different epitopes of SARS-N; six of these recognized the C-terminal domain of SARS-N while two recognized the N-terminal domain. Two were characterized by SPR and found to have low nanomolar dissociation constants (1.7 nM and 72 nM). At least four transfected SARS-N binding intrabodies were capable of selectively disrupting SARS virus replication inside cells.114 These anti-SARS intrabodies have been used as affinity reagents for detection of SARS.128

In a follow up study, anti-SARS fibronectins were engineered to recognize the nucleocapsid protein from SARS-CoV-2.129 The nucleocapsid protein from SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV are highly similar, with 91% identity and 94% similarity. The authors performed an initial doped selection based on one N-terminal domain binding fibronectin (NN1) and one C-terminal domain binding fibronectin (NC1) from the original selection, in order to improve the affinity and stability of these first-generation fibronectins. However, since the nucleocapsid sequence from SARS-CoV-2 (SARS-CoV-2 N) was not known at the beginning of the project, nucleocapsid from SARS-CoV (SARS-N) was instead used as the target. Two second-generation fibronectins, NN2 and NC2 were isolated with binding to both SARS-N (NN2 KD = 3.3 nM; NC2 KD = 390 pM) and to SARS-CoV-2 N (NN2 KD = 28 nM; NC2 KD = 6.7 nM). Both fibronectins retained binding to the respective domain of their parental clone and were able to bind the nucleocapsid protein inside SARS-CoV-2 infected cells. These second-generation fibronectins were once again doped and selected against SARS-CoV-2 N to make third-generation fibronectins. With only a single round of selection coupled with high throughput sequencing and a machine learning approach, several fibronectins were identified. Following expression and purification from E. Coli, one clone, NN3-1, was found to have a KD = 18 nM. Finally, this group engineered a sandwich ELISA-based assay for SARS-CoV-2 N detection using either a fibronectin and an antibody, or using two fibronectins, with sensitivity limits approaching 4 pg/mL in human sera.

A three-loop library was used to produce Adnectins that bound to the ligand-binding domain of a promiscuous nuclear receptor family member, human pregnane X receptor (PXR). Eight Adnectins were identified, with binding affinities (KD) ranging from 100 nM to sub-nanomolar values. These Adnectins bound to different epitopes with one Adnectin (KD = 11 nM) able to compete with the endogenous PXR ligand, steroid receptor co-activator-1 (SRC-1).97 Previously, the authors discovered a small molecule antagonist of CC Chemokine Receptor-1 (CCR1) with undesirable off-target binding to PXR. The anti-PXR Adnectin was used to obtain a co-crystal structure of the small molecule compound in complex with PXR. This co-crystal structure was important for the structure-based design of new small molecule derivatives with reduced PXR binding and off-target effects.97 This work highlights the ability of selected fibronectin ligands to act as crystallization chaperones to enhance target crystallization efforts.130

The 10Fn3 scaffold was also exploited to identify state-selective K- and H-Ras intrabodies. mRNA display was used to select a 10Fn3 that bound GTPγS-K-Ras(G12V), a constitutively active mutant Ras commonly found in cancer. This study included selective pressure for fibronectins that recognized the active, GTP-bound state. The selection resulted in a first-generation antibody called RasIn1 (Ras Intrabody), which had modest binding affinity (KD = 2.1 μM) and was state selective for active GTP-Ras versus inactive GDP-Ras. Affinity maturation of RasIn1 by doping the BC loop of RasIn1 and selecting with a fully randomized FG loop resulted in RasIn2. The second generation fibronectin showed improved affinity (KD = 120 nM) while retaining selectivity towards the GTP bound state of mutant K and H-Ras.119 By designing and expressing RasIn-GFP variants, the authors were able to monitor the activation state of Ras in living cells.119

Lastly, intrabodies to explore neuronal dynamics were engineered with mRNA display. These intrabodies were termed FingRs (Fibronectin Intrabodies Generated with mRNA display) and were first selected against excitatory and inhibitory post-synaptic marker proteins, Post Synaptic Density-95 (PSD-95) and Gephyrin, respectively.117 The authors of this study first selected for fibronectin ligands that recognized each protein. Several clones from each selection were expressed in cells and screened for their ability to colocalize with exogenously expressed target. Surprisingly, only a few fibronectins were able to colocalize in this assay, suggesting that this dual selection/screening strategy was required to identify functional FingRs. Fusing FingRs to GFP enabled live-cell imaging in dynamic protein trafficking and localization experiments. The authors note that use of these FingRs does not lead to observable changes in neurons, such as spine density, size of PSD-95 or Gephryin puncta, morphological, or electrophysiological changes.126 In a complementary study, a similar strategy was used to develop a FingR targeting Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II α (CaMKIIα). Dynamic changes in CaMKIIα clustering and localization in response to pH, Ca2+, or glutamate could be monitored in cortical neuron somata using FingR agents.118 These FingRs have been used in several other follow-up experiments131–133

6. Peptide Evolution by mRNA Display

6.1. Peptides and Peptide-Based Therapeutics

Natural peptides (e.g., hormones, neurotransmitters and growth factors) have critical roles in human physiology, specifically bind to their respective cellular receptors, and trigger a variety of downstream signals. Peptide therapeutics have been developed based on these natural peptides and as a class, have desirable safety and efficacy profiles and can have beneficial outcomes in treating human diseases.134 Peptides have the ability to modulate protein-protein interactions whereas few small molecules that bind tightly or disrupt protein-protein interfaces have been identified, with some exceptions.135 One hypothesis to explain this observation is that protein interaction surfaces are typically large and flat,135, 136 with the interface area per subunit for dimeric protein-protein interactions ranging from 350 to 4,900 angstroms.137 Lastly, peptides also have lower production costs and reduced quality control issues compared to protein-based biopharmaceuticals therapeutics and small molecules, making them nominally attractive molecular architectures for rapid clinical translation.134

Unfortunately, peptides are often seen as poor therapeutic candidates because of the poor stability of unmodified natural peptides and their short circulation times. Rational peptide design approaches to improve the physiochemical properties of peptides include: 1) improving chemical and physical stability by replacing amino acid residues susceptible to oxidation, isomerization, or chemical modifications,134, 138 2) improving solubility by modifying the charge distribution or pI (isoelectric point),134 3) increasing resistance to enzymatic modification by removing potential cleavage sites from the peptide sequence or by addition of non-natural modifications (e.g., cyclization, stapling, N-methylation, etc.), and 4) extending circulation time through PEGylation, acylation or by incorporating albumin binding elements.134, 139–141 However, as discussed above, these rational design approaches can be difficult because of context-dependent effects.

In the context of oncology, peptides are attractive alternatives to existing biologics because their tumor penetration is potentially enhanced relative to larger biologics. Tumor penetration is a complex function of molecular size, vascular permeability, affinity, diffusibility, stability, and plasma clearance.142 A comparison of Her2 targeting therapeutics of vastly differing molecular weights demonstrated that compounds with low effective molecular weight (e.g., affibodies and peptides) and high molecular weight (e.g., antibodies) penetrated tumors much more effectively than compounds with intermediate molecular weights (e.g., Fab fragments and scFvs).67 The higher tumor permeability of small peptides was attributed to their rapid diffusivity and interstitial transport as well as enhanced extravasation through capillary vessels of the tumor tissue.67 High tumor penetration of extremely large molecules, such as antibodies, was attributed to their long serum half-lives (days to weeks) which provides sufficient time for slow, but continuous tumor uptake. In addition, the rate of clearance from the body is roughly inversely proportional to compound size, and as a result, peptides offer different pharmacokinetics than mAbs. Unlike antibodies the small effective molecular weight of peptides generally results in rapid renal clearance within minutes following their administration.143 In some applications – such as imaging or treatment with compounds with small therapeutic windows – fast clearance of a compound could be desirable. Finally, peptides are generally considered less immunogenic than proteins (though peptides may contain some immunogenic sequences143) and therefore are predicted to have more favorable safety profiles.144, 145

Peptides thus offer a different modality for treatment of disease and many efforts have focused on isolating novel peptide sequences that recognize macromolecules or making peptides more drug-like through macrocyclization and introduction of non-natural amino acids. In this section, we review mRNA display selections supporting these efforts.

6.2. Linear Peptides Selected with mRNA Display

6.2.1. RNA Binding Peptides

RNA- and DNA-binding proteins are key regulators of transcription and translation.64 mRNA display has been used to discover novel ligands that recognize nucleic acids with high affinity and specificity.146, 147 Engineering novel nucleic acid-binding ligands is a challenge for mRNA display since the nucleic acid target must be recognized in the context of the fused mRNA/cDNA that could cause off-target binding. Liu et al. showed that the λ N peptide (1-22 amino acids) synthesized as an mRNA-peptide fusion retained its ability to recognize its cognate BoxBR target.13 Selection conditions were also optimized in order to develop a robust protocol for selection of RNA-binding peptides.23 An important result from this work was that increasing the amount of non-specific competitor (i.e., non-target nucleic acid, such as tRNA) increased the enrichment of RNA-binding peptides, probably by increasing the selection stringency for peptides that bound to the target RNA.

Building on this work, Barrick et al. designed several libraries based on the λ N peptide.146 One library randomized two positions and was selected against the BoxBR hairpin target. Surprisingly, few of the resulting peptides contained wild type residues at the randomized positions, with arginine favored at position 15 instead of the wild type glutamine. Although these peptides still bound the BoxBR target, they did so using a distinct recognition mode relative to wild type λ N peptide. A second library of 9 trillion sequences where the first ~11 amino acids of λ N peptide were fixed were while the last 10 C-terminal amino acids were randomized. This library was panned against three targets: 1) the cognate BoxBR RNA hairpin, 2) a non-cognate GNRA tetraloop, or 3) a non-cognate P22 hairpin. These targets all share the same stem as BoxBR, but differ in the hairpin loop by a single nucleotide.23, 146 More than 80 different peptide sequences were isolated which had few similarities with the wild type sequence or to each other. As with the selection described above, Arg15 was the most conserved residue in final pools. The selected peptides all bound their targets with nanomolar KD values and were able to distinguish between different RNA hairpins.146 Subsequent studies further examined the function of these selected peptides as well as their affinity and specificity for different RNA targets.148–150

6.2.2. G-Protein Signaling

Peptides can also be used to modulate intracellular signaling. Many of the most important intracellular signaling networks are controlled by G-Protein Coupled Receptors (GPCRs).151, 152 Binding of cognate ligands to GPCR extracellular domains results in activation of G-proteins bound to the cytosolic portion of the receptor.153–155 There are three classes of G-protein subunits (α, β, γ), that associate in a combinatorial fashion.156 Furthermore, G-proteins α subunits have different states (GDP-bound, GTP-bound, or apo) which dictate their biochemical and biological function.157

To target proteins in the Gα family, Ja et al. designed a library based on the G-protein regulatory motif (L19 GPR) and performed a selection using Giα1 as the target. The library fixed 10 amino acids of the L19 GPR motif to act as an “anchor” for binding to Giα1, followed by six random amino acids. The selection resulted in a peptide called R6A (KD of 60 nM) which was selective for the GDP-bound form of Giα1. R6A was truncated to a nine amino acid version (called R6A-1) that retained a KD of 200 nM for Giα1. Surprisingly, R6A-1 only includes two amino acids from the original GPR “anchor,” suggesting that the majority of the fixed GPR residues were dispensable for binding in the context of the newly selected residues. However, R6A and R6A-1 still compete with L19 GPR for binding, suggesting that they bind the same site, though the authors could not rule out allosteric competition. In addition, both peptides inhibit the guanine nucleotide dissociation of Giα1 and compete with Gβγ for binding to Giα1.153, 158

Further studies examined the specificity profile of the selected peptides. While L19 GPR has selectivity for the Gαi class, R6A was able to bind to three Gα classes, and R6A-1 was able to bind to all four Gα classes (Gα, Go, Gq, and Gs).159 Since truncation of R6A to R6A-1 resulted in a decrease of specificity, the authors hypothesized that performing the inverse experiment – i.e., addition of amino acids to R6A-1 – might confer binding specificity to different Gα classes. To test this hypothesis, Austin and co-workers designed a library based on R6A-1 of the form MXXXXXXDQLYWWEYLXXXXXX, where the central R6A-1 sequence (bold) was doped at ~50% wild type amino acids and six random amino acids (X positions) were added to the N- and C-terminus.160 This library was used in a positive selection for Gαs(s) binding, which resulted in a peptide called GSP that was able to bind with some specificity to Gαs(s) but still retained some binding to Giα1. A second library based on the GSP sequence was used in a second selection that included a negative selection for binding to Giα1. Here, a molar excess of soluble Giα1 was added to the binding buffer to act as a decoy in the presence of immobilized Gαs(s). This dual selection strategy resulted in highly specific Gαs(s) peptides with KDs in the 130-300 nM range, representing an over 8,000-fold change in specificity from Giα1 to Gαs(s).160

This library was also used in a second selection to generate state-specific peptides. In this selection, the library described above was targeted to Giα1-AlF (AlF3 or AlF4−), which mimics the transition state of GTP hydrolysis. This selection also included a negative selection against Giα1-GDP to remove Giα1-GDP binding sequences. Two peptides with the highest ratio of binding Giα1-AlF versus Giα1-GDP (AR6–04 and AR6–05) were chosen for further characterization. Even with the negative selection, AR6–05 had a KD of 10 nM for Giα1-GDP, blocked Gβγ binding, and enhanced the basal current of a downstream G-protein-activated inwardly rectifying potassium (GIRK) channel. AR6-04 was the only peptide that bound more strongly to Giα1-AlF versus Giα1-GDP. It also enhanced Gβγ binding to Giα1, in contrast with the AR6-05 and the parental R6A-1 peptides. One reason why Giα1-AlF-specific peptides might have not been readily found is that AR6-04 also has a much weaker KD of 10 μM, yet was still able to decrease downstream basal GIRK current.161