Abstract

Background

Pain relief remains a major subject of inadequately met need of patients. Therapeutic agents designed to treat pain and inflammation so far have low to moderate efficiencies with significant untoward side effects. FAAH-1 has been proposed as a promising target for the discovery of drugs to treat pain and inflammation without significant adverse effects. FAAH-1 is the primary enzyme accountable for the degradation of AEA and related fatty acid amides. Studies have revealed that the simultaneous inhibition of COX and FAAH-1 activities produce greater pharmacological efficiency with significantly lowered toxicity and ulcerogenic activity. Recently, the metabolism of endocannabinoids by COX-2 was suggested to be differentially regulated by NSAIDs.

Methods

We analysed the affinity of oleamide, arachidonamide and stearoylamide at the FAAH-1 in vitro and investigated the potency of selected NSAIDs on the hydrolysis of endocannabinoid-like molecules (oleamide, arachidonamide and stearoylamide) by FAAH-1 from rat liver. NSAIDs were initially screened at 500 μM after which those that exhibited greater potency were further analysed over a range of inhibitor concentrations.

Results

The substrate affinity of FAAH-1 obtained, increased in a rank order of oleamide < arachidonamide < stearoylamide with resultant Vmax values in a rank order of arachidonamide > oleamide > stearoylamide. The selected NSAIDs caused a concentration-dependent inhibition of FAAH-1 activity with sulindac, carprofen and meclofenamate exhibiting the greatest potency. Michaelis-Menten analysis suggested the mode of inhibition of FAAH-1 hydrolysis of both oleamide and arachidonamide by meclofenamate and indomethacin to be non-competitive in nature.

Conclusion

Our data therefore suggest potential for study of these compounds as combined FAAH-1-COX inhibitors.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40360-021-00539-1.

Keywords: Arachidonamide, Affinity, FAAH-1, Hydrolysis, Oleamide, Arachidonamide, Stearoylamide, Inhibition, NSAIDs, Mode

Introduction

Several therapeutic agents have been designed to address different forms of pain, yet pain relief remains an area of significant unmet patient need [1, 2]. Drugs administered to treat pain and inflammation presently have low to moderate efficiencies with significant untoward side effects such as gastrointestinal bleeding, ulceration, renal dysfunction, nausea and vomiting.

Fatty acid amide hydrolase I (FAAH-1) has been proposed as a promising target for the discovery of drugs to treat pain, inflammation and other pathologies [3, 4]. FAAH-1 is the primary enzyme that is responsible for the degradation of N –Arachidonoyl ethanolamide (Anandamide, AEA) and related fatty acid amides which constitute a group of biologically active endogenous amides [5, 6]. Inhibition of FAAH-1 results in the accumulation of AEA and other endocannabinoid-like molecules in the central and peripheral nervous systems where they act as ligands of cannabinoid (CB1 and CB2) receptors. Similar to Δ9 -tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), AEA is a partial agonist at both CB1 and CB2 transmembrane receptors - members of the G-protein-coupled receptor superfamily [7–9] however, in contrast to THC, AEA also stimulates the transient receptor potential vanilloid receptor type 1 (TRPV1) [10–12]. AEA exhibits cannabimimetic effects at the cannabinoid receptors [13]. Palmitoyl ethanolamide has also been reported to be active at peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) as well as vanilloid receptors. The primary fatty acid amides (PFAMs) such as oleamide, arachidonamide, stearoylamide, stearoyl ethanolamide, palmitamide, etc.) are also important molecules controlling sleep, angiogenesis, locomotion, convulsions and inhibition of gap junction formation among several other functions [14–18].

Although the major current strategy for drug development is to design compounds that are selective for a given target, compounds that target more than one biochemical process may have superior efficacies with better safety profiles compared with standard selective compounds. This can be achieved by administering the drugs either separately or in single tablets made of more than one active ingredient. The disadvantage in both cases is the potential for a large pharmacokinetic variability that is equivalent to the concomitant administration of separate drugs. The alternative to avoid these drawbacks is to develop drugs that target more than one molecular mechanism [19]. Inhibition of COX-1 and -2 at the first committed step of prostanoid and other eicosanoid biosynthesis from arachidonic acid (AA) underlies the analgesic action of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) [20–23]. NSAIDs constitute a class of chemically diverse compounds that provide analgesic, antipyretic and anti-inflammatory effects. The fatty acid metabolic end-products of the induction of the COX cascade by a wide range of stimuli are prostaglandins (PGD2, PGE2, PGF2α and PGI2). AA embedded in cell membranes as esters of phospholipids is the precursor of prostaglandins (PGs). AA is made available by action of several enzymes including cPLA2/sPLA2, αβ Hydrolase 4 and GDE [24]. Once induced, COX, LOX and cytochrome P450 enzymes convert available AA to various eicosanoids. These eicosanoids are known essential physiological and pathophysiological mediators implicated in a wide scope of therapeutic interest such as in inflammation, pain, cancer, glaucoma, male sexual dysfunction, osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, labour, asthma, etc [25]

Selected NSAIDs have also been reported to inhibit FAAH-1 activity from mouse and rat preparations [26]. Studies in animal models have revealed that the simultaneous inhibition of COX and FAAH-1 activities produce greater pharmacological efficiency with significantly lowered toxicity and ulcerogenic activity associated with COX inhibitors [27, 28]. More recently, the metabolism of endocannabinoids by COX-2 was suggested to be differentially regulated by NSAIDs resulting in antinociceptive effects mediated via cannabinoid receptors [29–32]. Apart from catalysing the formation of PGs from AA, COX-2 also catalyses the formation of prostaglandin-glycerol esters and prostaglandin ethanolamines from 2-arachidonoyl glycerol (2-AG) and AEA respectively [30, 33–35]. Since COX-2 is a significant target of NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibition can reduce this mechanism of endocannabinoid metabolism to enhance their concentrations in vivo [36, 37]. Moreover, rapid reversible inhibitors of COX-2 selectively inhibit the oxygenation of 2-AG and AEA with much higher potencies for AA, a phenomenon referred to as substrate selective effect [30, 38]. The fact that selected NSAIDs inhibit AEA and 2-AG metabolism via FAAH-1 and COX inhibition in vivo, suggests that at the appropriate concentrations, NSAIDs may co-regulate the activity of both COX and FAAH-1 enzymes which make them better suitable therapeutic agents [39, 40]. Since cannabinoids possess anti-inflammatory, antinociceptive, analgesic, anti-tumour and immunosuppressive properties, inhibitors of endocannabinoid degrading enzymes (FAAH-1, FAAH-2, NAAA, COX-2, LOX, MAGL) may be of therapeutic significance via augmentation of endocannabinoid and endocannabinoid-like molecule accumulation in vivo. Based on this previous knowledge, it is essential to conduct further investigations on the ability of other NSAIDs to inhibit FAAH-1 deamination of endocannabinoid and endocannabinoid-like molecule substrates (e.g. oleamide, arachidonamide, stearoylamide and stearoyl ethanolamide among others) for the reason that NSAIDs with both inhibitory capabilities (on COX and FAAHs) will synergistically enhance therapeutic efficacies. The aim of this study therefore, was to assess pharmacological profiles of FAAH-1 with regards to potential substrates and inhibitors. The investigation was specifically designed to assess the potency of selected NSAIDs on the hydrolysis of oleamide, arachidonamide and stearoylamide by FAAH-1.

Materials and methods

FAAH-1 activity was studied in rat liver homogenate.

Preparation of rat liver homogenate

Liver obtained from male Wister rats (150–250 g, Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, USA) which had been stored at − 40 °C was thawed. A volume of 6 ml/g wet weight of rat liver was homogenized in 0.2 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 using a hand held homogenizer (Ultra-turrax) (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). The resulting mixture was centrifuged at 250 g for 10 min after which the pellet obtained was re-homogenised and centrifuged as aforementioned. The supernatants were combined and centrifuged at 20,000 g for 30 min, after which the membrane containing pellet was re-suspended in 1:1w/v 0.2 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, and stored in 1 ml aliquots at − 40 °C.

Assay of FAAH-1 activity

FAAH-1 activity was assayed essentially as described previously [41]. Briefly, rat liver homogenate was pre-incubated at 37 °C with shaking (50 × 10 rpm) for 10 min in 0.2 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 in 96-well microtitre plates (Thermo Scientific Inc., Waltham, USA) prior to substrate addition and incubation at 37 °C for 30 min. The 100 μl total assay reaction mixtures were halted with an equivalent volume of o-phthaldehyde (OPA) developing solution (0.4 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 11.5) and incubated further at 37 °C for 15 min before assessing fluorescence using a FLUOstar Galaxy (Excitation 390 nm, Emission 450–10 nm) (BMG LABTECH GmbH, Ortenberg, Germany). Substrate blank and a control containing 0.2 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, were incorporated into the experiments.

Subsequently, the influence of ethanol concentrations on the ability of particular NSAIDs e.g. indomethacin (SIGMA-ALDRICH, Poole, UK) was assessed by varying the volume of inhibitor solution added, using both absolute ethanol and buffer blanks to account for background influences on enzymatic activity.

Protein assay

Homogenate protein content was measured by modifications of the method described [42] using 200 μl of different concentrations of bovine serum albumin (0, 25, 50, 100, 150, 200, 300 μg/ml) as standard and 200 μl of 0.5 M NaOH as blank (Fig. SS1). Briefly, 50 μl of each membrane fragment in 5 ml of 0.5 M NaOH was prepared, after which 200 μl of each dilution was added to 1 ml of solution A (100 ml of 2% sodium carbonate and 1 ml each of both sodium potassium tartrate and copper sulphate). The solutions were mixed and allowed to stand at room temperature. After 10 min, 100 μl of dilute Folin Ciocalteau’s reagent 1:1 ddH2O was added and mixed immediately. The absorbance of each sample was read at a wavelength of 700 nm following incubation at room temperature for 1 h. Relative absorbance of each sample was entered into GraphPad prism and analysed. The protein concentration of preparations were interpolated from the standard (Fig. SS1), using non-linear, second order polynomial (quadratic) graph of the standards.

Statistical analysis

Data obtained were entered into a Microsoft Excel 2010 spread sheet and analysed with GraphPad Prism computer software programme (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA USA). Effect of 500 μM concentration of NSAIDs (SIGMA-ALDRICH, Poole, UK) on each enzyme activity was analysed by removing the baseline line. Each specific activity was then plotted as percentage of control. Specific activity obtained at each inhibitor concentration for the concentration-inhibition curves were normalized and analysed using the inbuilt log (inhibitor) versus response variable slope (robust fit) and were constrained at the bottom (= 0.0%). Each specific activity was then plotted as percentage of the control. To determine the mode of inhibition, Vmax values were initially extrapolated from the (NH4)2SO4 standard curve plotted using the inbuilt second order polynomial (quadratic) Michaelis-Menten enzyme kinetics. These values were then adjusted using the protein concentrations of the preparations obtained from the Lowry protocol [42] (Fig. SS1 and SS2).

Results and discussion

Affinity of oleamide, arachidonamide and stearoylamide at FAAH-1

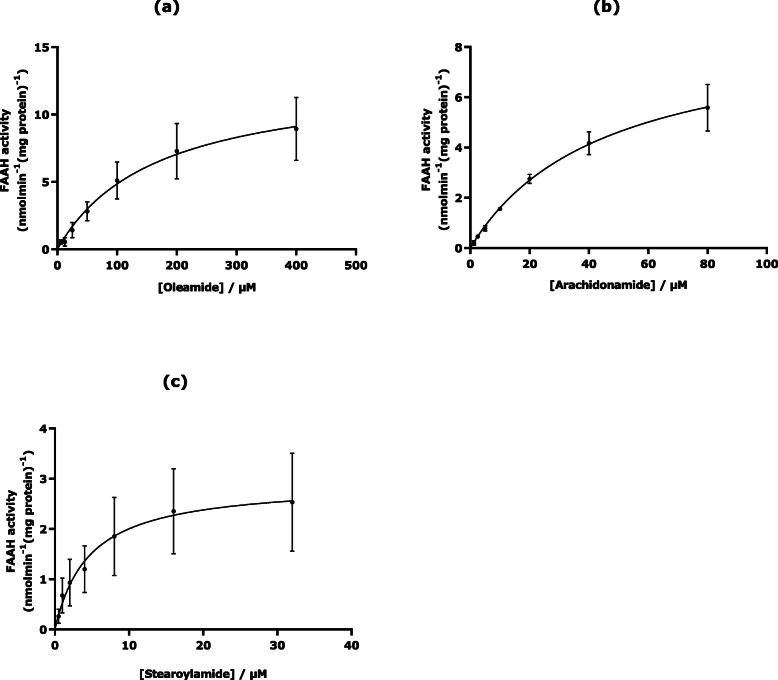

Several drugs are inhibitors of the most relevant enzymes since blocking these enzymes can kill a pathogen or correct a metabolic imbalance. To characterise an enzyme in the presence of inhibitors however, a good kinetic description of its activity is essential. Here, the ability of rat liver to hydrolyse oleamide, stearoylamide and arachidonamide was assessed by Michaelis-Menten analysis (Fig. 2). The resultant Michaelis-Menten constant (Km) and maximum velocity (Vmax) values obtained are summarized in Table 1. The substrate affinity of FAAH-1 increased in a rank order of oleamide < arachidonamide < stearoylamide with resultant Vmax values in a rank order of arachidonamide > oleamide > stearoylamide (Fig. 1, Table 1). The kinetic values for FAAH-1 hydrolysis of oleamide obtained are consistent with previous observations. Similar Km and Vmax values of 129 μM and 15 nmol.min− 1.mg protein− 1 from oleamide hydrolysis by FAAH-1 in rat liver preparations and a Km value of 179 μM with FAAH-1 in rat brain were previously obtained compared with Km of 177.2 ± 15.5 μM and Vmax of 8.9 ± 1.1 nmol.min− 1.mg protein− 1 obtained in our findings (Table 1) [41]. An affinity of 104 μM and a Vmax of 5.7 nmol.min− 1.mg protein− 1 for rat liver FAAH-catalysed oleamide hydrolysis has been reported [44]. Additionally, an affinity of 37 ± 7 μM at pH 9 for rat recombinant FAAH-catalysed oleamide hydrolysis has also been reported [45].

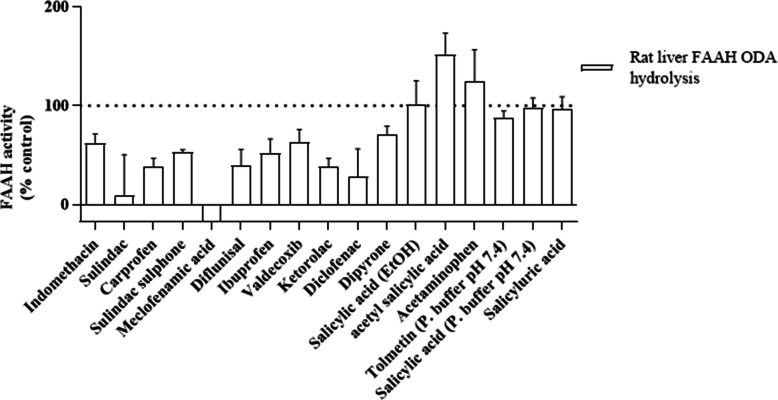

Fig. 2.

Effect of 500 μM concentration of NSAIDs on rat liver FAAH-1 oleamide hydrolase activity. Data are mean ± SEM (Standard Error of the Mean) of four separate preparations (n = 4) conducted in triplicate

Table 1.

Km and Vmax values determined for rat liver FAAH-1 hydrolysis of three different fatty acid amides

| FAAH-1 kinetics | Substrate | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Oleamide | Arachidonamide | Stearoylamide | |

| Km (μM) | 177.2 ± 15.5 | 44.9 ± 7.0 | 4.6 ± 0.8 |

| Vmax (nmol/min/mg protein) | 8.9 ± 1.1 | 10.1 ± 3.0 | 2.5 ± 0.6 |

Data are mean ± SEM (Standard Error of the Mean) of four separate preparations (n = 4) conducted in triplicate

Fig. 1.

Hydrolysis of oleamide (a), arachidonamide (b) and stearoylamide (c) by rat liver FAAH-1 activity. Rat liver FAAH-hydrolytic activity of each primary amide substrate in vitro, was assayed by quantification of ammonia released after hydrolysis. Ammonia generated in the presence of sulphite ions is reacted with alkaline o-phthaldehyde (OPA) to generate the stable fluorescent isoindole derivative (1-sulphonatoisoindole) which is quantified by fluorescent spectroscopy [41, 43]. Four separate experiments with three replicates on the same microtiter plate were conducted for each substrate using different rat liver preparations. Data are mean ± SEM (Standard Error of the Mean) of four separate preparations (n = 4) conducted in triplicate

FAAH-1 has the ability to hydrolyse a wide range of unsaturated and, to a lesser extent, saturated PFAMs and other fatty acids e.g. oleamide and palmitoyl ethanolamide [46, 47]. In our findings, FAAH-1 capacity (Vmax) was 12% higher for arachidonamide compared with oleamide and 75% higher than that for stearoylamide. This confirms the propensity of FAAH-1 to turn over polyunsaturated PFAMs particularly with cis double bonds at higher rates than monounsaturated and saturated PFAMs and is consistent with literature (Fig. 1) [48, 49].

Screening of NSAIDs as potential inhibitors of oleamide, arachidonamide and stearoylamide hydrolase activity

Following pilot experiments that revealed indomethacin to have an IC50 ~ 500 μM, 16 selected NSAIDs were screened at 500 μM (Fig. 2) for ability to inhibit FAAH-1 in order to assess pharmacological profiles of rat liver FAAH-catalysed hydrolysis of the three PFAMs assayed at a concentration ≥ Km value determined [41, 43]. NSAIDs were randomly selected based on availability and considering what had not been reported while using a few that had been reported against FAAH-1 as reference standards. Meclofenamic acid exhibited complete inhibition of FAAH-1 activity when oleamide was used as substrate. Sulindac, diclofenac, carprofen, ketorolac and diflunisal exhibited a higher degree of inhibition of rat liver FAAH-1 activity by inhibiting oleamide hydrolysis to below 50% of control (Fig. 2). Ibuprofen, sulindac sulphone, indomethacin and dipyrone were moderate inhibitors of oleamide hydrolysis and inhibited FAAH-1 activity to between 50 and 70% of control. Tolmetin, salicyluric acid, salicylic acid (diluted in 0.2 M potassium phosphate buffer) evoked weak inhibitory ability of FAAH-1 activity to between 70 and 100% of control. Acetaminophen and acetyl salicylic acid appeared to enhance enzyme activity.

Acetaminophen is reported to be metabolised to N-arachidonoylaminophenol (AM404) via FAAH-1 [50]. AM404 then inhibits FAAH-1 activity and prevents AEA metabolism. Thus, FAAH-1 is active until concentrations of AM404 are high enough to inhibit its function. AEA accordingly activates platelets, however, the process is unaffected by acetyl salicylic acid, thus it is possible it did not affect rat liver FAAH-1 activity [51]. The differences in reaction of FAAH-1 to specific compounds (e.g. ketorolac or ibuprofen) might be due to differences in structures, their sites of binding to FAAH-1 and how this affects substrate entry and binding at the catalytic sites [52–55].

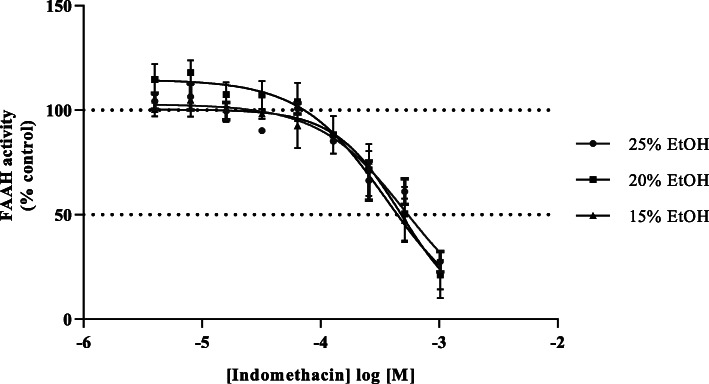

Effect of vehicle controls on FAAH activity

As the NSAIDs are differently soluble in aqueous compared to organic solution, the effect of a range of concentrations of the vehicle ethanol was assessed using indomethacin as a reference compound. Indomethacin evoked a concentration-dependent inhibition of FAAH-1 activity in pIC50 values between 15, 20 or 25% ethanol concentrations (Fig. 3). Tukey’s multiple comparisons test with single pooled variance, p = 0.7250, p < 0.05 as significantly different, CI = 95% indicated no significant difference between pIC50 values obtained (Table 2). This implies that, within the experimental limits, ethanol had no effect on the inhibitory function of indomethacin, albeit with a reduced capacity for basal oleamide hydrolysis of 95 ± 1, 78 ± 1 and 76 ± 4% of control for 15, 20 and 25% assay ethanol respectively consistent with earlier reports that butanol reduced FAAH-1 activity by 30 to 50% but did not affect the enzyme response to inhibitors [40].

Fig. 3.

Effect of 15, 20 and 25% ethanol on the inhibition of rat liver oleamide hydrolase activity by indomethacin. Data are mean ± SEM (Standard Error of the Mean) of four separate preparations (n = 4) conducted in triplicate

Table 2.

Potency of indomethacin in the presence of different concentrations of ethanol

| 15% EtOH | 20% EtOH | 25% EtOH | |

|---|---|---|---|

| pIC50 | 3.4 ± 0.1 | 3.5 ± 0.1 | 3.4 ± 0.1 |

| FAAH-1 activity (%) | 95 ± 1 | 78 ± 1 | 76 ± 4% |

Data are mean ± SEM (Standard Error of the Mean) of four separate preparations (n = 4) conducted in triplicate

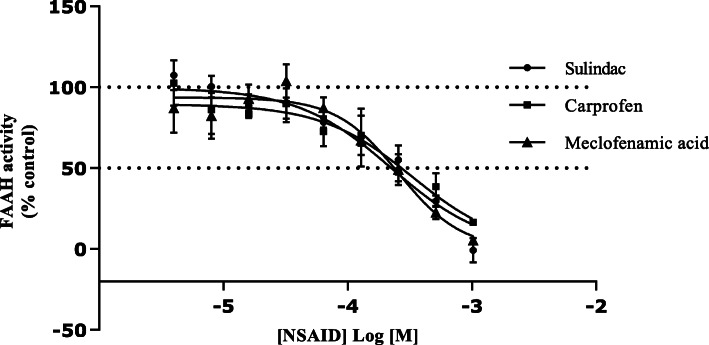

Concentration-dependence of rat liver FAAH-1 oleamide hydrolase inhibition

NSAIDs selected on the basis of the greater levels of inhibition at 500 μM were examined over a range of concentrations in absolute ethanol, from 4.0 × 10− 6 to 1.024 × 10− 3 M (Fig. 4). These exhibited concentration-dependent inhibition of FAAH-1 oleamide hydrolase activities. The order of inhibitory potency against rat liver FAAH-1 hydrolysis of oleamide was sulindac > carprofen > meclofenamic acid > sulindac sulphone > indomethacin > diflunisal > ibuprofen > valdecoxib > ketorolac > diclofenac > dipyrone (Table 3). The remaining NSAIDs assayed exhibited very similar potencies (pIC50 values) against activity of FAAH-1. The inhibition exhibited by the selected NSAIDs to FAAH-1 activity (Fig. 4, Table 3) is consistent with earlier studies although under different conditions [26, 39, 56, 57]. The rank order of potency displayed by NSAIDs screened at 500 μM was not exactly the same when the pIC50 values were examined. Earlier findings indicate that NSAID inhibition of FAAH-1 activity is pH dependent [58] with a pH optimum of ~ 9 [46, 59–63]. The rank order of NSAIDs reported for potency against rat brain FAAH-1 activity at pH 7.4 was; indomethacin (pIC50 = 4.18) ≈ carprofen (pIC50 = 4.10) > ibuprofen (pIC50 = 3.1) and is similar to our findings however, indomethacin was less effective than carprofen and more potent than ibuprofen [52]. Other studies found apparently biphasic pH dependence of FAAH AEA metabolism using brain microsomes [64].

Fig. 4.

Concentration-dependence of rat liver oleamide hydrolase activity inhibition. Data are mean ± SEM (Standard Error of the Mean) of four separate preparations (n = 4) conducted in triplicate

Table 3.

Potencies of NSAIDs as inhibitors of rat liver oleamide hydrolase activity

| NSAID | pIC50 (M) | NSAID | pIC50 (M) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sulindac | 3.65 ± 0.08 | Ibuprofen | 3.01 ± 0.06 |

| Carprofen | 3.58 ± 0.09 | Valdecoxib | 3.00 ± 0.15 |

| Meclofenamic acid | 3.57 ± 0.06 | Ketorolac | 2.91 ± 0.07 |

| Sulindac sulphone | 3.35 ± 0.03 | Diclofenac | 2.90 ± 0.07 |

| Indomethacin | 3.28 ± 0.03 | Dipyrone | 2.77 ± 0.07 |

| Diflunisal | 3.15 ± 0.04 |

Data are mean ± SEM (Standard Error of the Mean) of four separate preparations (n=4) conducted in triplicate

Mode of inhibition of FAAH-1 metabolism by meclofenamic acid and indomethacin

To date, little has been reported on the mode of inhibition of NSAIDs on FAAH-catalysed hydrolysis of endocannabinoids and endocannabinoid-like molecules [26, 52]. Hence, meclofenamic acid and indomethacin were selected for further mechanistic investigation as the former evoked the greatest inhibition and the latter has previously been examined extensively in the literature [26].

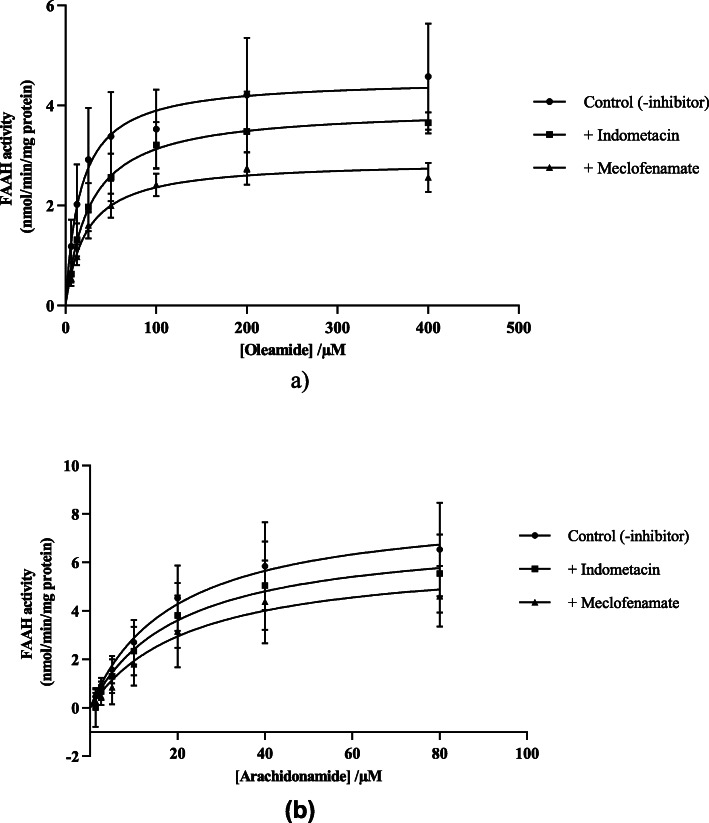

Michaelis-Menten analysis indicated no significant changes in substrate affinity (Km) values but with decreasing Vmax values (Fig. 5, Table 4), thus indicative of non-competitive type inhibition of FAAH activity by the two inhibitors (meclofenamic acid and indomethacin). This finding is consistent with similar findings that FAAH is mechanistically allosteric in nature which is often associated with a non-competitive mode of inhibition, thus FAAH might also likely exhibit a non-competitive mode of inhibition against these NSAIDs [58, 65, 66]. Unlike aspirin which is an irreversible inhibitor of COX enzymes, most other NSAIDs are reversible competitive inhibitors of the COX enzymes [67]. Previously scientists [38] found that meclofenamic acid and ibuprofen are also potent inhibitors of COX-2 suggestive of the potential for the design of a dual targeting inhibitor possibly in combination with URB597 an uncompetitive FAAH inhibitor [68], which may reduce the loading dose of NSAIDs with resultant fewer side effects.

Fig. 5.

Mode of inhibition of rat liver FAAH-1 hydrolysis of (a) oleamide and (b) arachidonamide by meclofenamic acid and indomethacin. Data are mean ± SEM (Standard Error of the Mean) of four separate preparations (n = 4) conducted in triplicate

Table 4.

Mode of inhibition of rat liver FAAH-1 oleamide hydrolysis by indomethacin and meclofenamate

| FAAH-1 Kinetics | Km (μM) | Vmax (nmol/min/mg protein) | Substrate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 18.4 ± 3.5 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | Oleamide |

| + 200 μM indomethacin | 24.4 ± 3.3 | 3.8 ± 0.4 | Oleamide |

| + 100 μM meclofenamate | 22.7 ± 1.4 | 2.9 ± 0.1 | Oleamide |

| Control | 19.8 ± 2.0 | 8.4 ± 1.2 | Arachidonamide |

| + 200 μM indomethacin | 21.6 ± 2.8 | 7.2 ± 0.9 | Arachidonamide |

| + 100 μM meclofenamate | 23.4 ± 3.7 | 6.7 ± 1.0 | Arachidonamide |

Data are mean ± SEM of triplicate assessments conducted on five transient transfects (n = 5)

Therapeutic application of novel multi-target (FAAH/COX) analgesics

In vivo increases in the levels of AEA resulting from FAAH-1 inhibition potentiates actions of COX inhibitors [19, 31] suggesting that, compounds that inhibit both FAAH and COX enzymes can be as effective as NSAIDs but with a reduced COX inhibitor ‘load’, consequently with accompanying reduction in the adverse effects associated with NSAIDs [19]. There is evidence to support the controversy that dual-action FAAH-COX inhibitors may be more useful in this aspect. In vitro evidence suggests that the metabolism of AEA by COX-2 might be the most predominant degradation pathway after blocking the major FAAH metabolic pathway. Combinations of URB597 and diclofenac have demonstrated synergistic analgesic interactions [27, 69]. Also, in vivo synergistic effect was achieved by administration of a combination of AEA and rofecoxib. Local injection of AEA with NSAID (ibuprofen or rofecoxib) generated higher amounts of fatty acid ethanolamides [70]. Synergistic effects have also been reported after a systematic administration of URB597 and diclofenac in a mouse model of visceral pain [71]. Meclofenamic acid, carprofen and indomethacin are among the most potent inhibitors of the COX enzymes and at the same time FAAH-1 from our study [72–75]. Our in vitro results support the possibility of combined therapeutic agents being explored. This suggests that, a combination of FAAH inhibitors such as URB597 and the NSAIDs with dual inhibitory capability may have greater utility to treat pain with reduced NSAID load and may have enhanced efficacies and safety profiles.

Conclusion

We established inhibitory potencies of NSAIDs against rat liver FAAH-1 using oleamide, arachidonamide and stearoylamide as substrates. Substrate affinity of FAAH-1 increased in a rank order of oleamide < arachidonamide < stearoylamide with resultant Vmax values in a rank order of arachidonamide > oleamide > stearoylamide. Our Findings confirmed the propensity of FAAH-1 to turn over polyunsaturated PFAMs particularly with cis double bonds at higher rates than monounsaturated and saturated PFAMs. In the presence of meclofenamate or indomethacin, Michaelis-Menten analysis suggested a reduction in the Vmax of oleamide and arachidonamide hydrolysis, without significant alteration in substrate affinity, indicative of a non-competitive action of these inhibitors against FAAH-1 activity though more research is required for conclusive evidence. Even though, there was no indication of any selective action of NSAIDs, these results suggest potential for study of these compounds as combined FAAH-COX inhibitors.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Stephen P.H. Alexander, Dr. Simon P. Dawson, Dr. Michael Garle, Liaque Lateef, Nicola De Vivo and Monika Owen, all of the School of Life Sciences, University of Nottingham, UK for their support. We are grateful to our sponsors, Ghana Education Trust Fund (GETFund), Ghana and the University for Development Studies, Ghana for funding, and the University of Nottingham, UK, for providing the environment in which to conduct these studies.

Authors’ contributions

J.T.D performed the experiments and drafted the manuscript. A. O, G.K.H, K.O-A and C.A.W contributed to the final version of the manuscript The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The project was financed by GETFund.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were carried out in accordance with the relevant UKRIO (UK Research Integrity Office) guidelines and regulations for animal use in research and the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 19862 (ASPA) and guidance regulating the use of animals in scientific procedures. All experimental protocols were approved by the ethics committee of the School of Life Sciences, University of Nottingham Medical School, Queen’s Medical Centre, UK. All experiments on animal parts were carried out in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Stahl S, Briley M. Understanding pain in depression. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2004;19(Suppl 1):S9–S13. doi: 10.1002/hup.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson KG, Eriksson MY, D'Eon JL, Mikail SF, Emery PC. Major depression and insomnia in chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 2002;18(2):77–83. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200203000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clapper JR, Moreno-Sanz G, Russo R, Guijarro A, Vacondio F, Duranti A, Tontini A, Sanchini S, Sciolino NR, Spradley JM, Hohmann AG, Calignano A, Mor M, Tarzia G, Piomelli D. Anandamide suppresses pain initiation through a peripheral endocannabinoid mechanism. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13(10):1265–1270. doi: 10.1038/nn.2632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaetani S, Dipasquale P, Romano A, et al. The endocannabinoid system as a target for novel anxiolytic and antidepressant drugs. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2009;85:57–72. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(09)85005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahn K, Douglas SJ and Cravatt BF. Fatty acid amide hydrolase as a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of pain and CNS disorders. Expert Opin Drug Discov 2009; 4(7): 763–784.: 763–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Di Marzo V, Melck D, Bisogno T, et al. Endocannabinoids: endogenous cannabinoid receptor ligands with neuromodulatory action. |21,: 521. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Mackie K. Cannabinoid receptors: where they are and what they do. J Neuroendocrinol. 2008;20(Suppl 1):10–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graham ES, Ashton JC and Glass M. Cannabinoid Receptors: A brief history and what not. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2009; 14: 944–957. DOI: 10.2741/3288, Cannabinoid Receptors: A brief history and "what's hot", 14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Howlett AC. The cannabinoid receptors. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2002;68-69:619–631. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(02)00060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ross RA. Anandamide and vanilloid TRPV1 receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;140(5):790–801. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smart D, Gunthorpe MJ, Jerman JC, Nasir S, Gray J, Muir AI, Chambers JK, Randall AD, Davis JB. The endogenous lipid anandamide is a full agonist at the human vanilloid receptor (hVR1) Br J Pharmacol. 2000;129(2):227–230. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zygmunt PM, Petersson J, Andersson DA, Chuang HH, Sørgård M, di Marzo V, Julius D, Högestätt ED. Vanilloid receptors on sensory nerves mediate the vasodilator action of anandamide. Nature. 1999;400(6743):452–457. doi: 10.1038/22761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deutsch DG, Chin SA. Enzymatic synthesis and degradation of anandamide, a cannabinoid receptor agonist. Biochem Pharmacol. 1993;46(5):791–796. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90486-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Basile AS, Hanus L, Mendelson WB. Characterization of the hypnotic properties of oleamide. Neuroreport. 1999;10(5):947–951. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199904060-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheer JF, Cadogan AK, Marsden CA, Fone KC, Kendall DA. Modification of 5-HT2 receptor mediated behaviour in the rat by oleamide and the role of cannabinoid receptors. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38(4):533–541. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00208-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cravatt BF, Prospero-Garcia O, Siuzdak G, Gilula NB, Henriksen SJ, Boger DL, Lerner RA. Chemical characterization of a family of brain lipids that induce sleep. Science. 1995;268(5216):1506–1509. doi: 10.1126/science.7770779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leggett JD, Aspley S, Beckett SR, et al. Oleamide is a selective endogenous agonist of rat and human CB1 cannabinoid receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;141(2):253–262. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mechoulam R, Fride E, Hanus L, et al. Anandamide may mediate sleep induction. Nature. 1997;389(6646):25–26. doi: 10.1038/37891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fowler CJ, Naidu PS, Lichtman A, Onnis V. The case for the development of novel analgesic agents targeting both fatty acid amide hydrolase and either cyclooxygenase or TRPV1. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;156(3):412–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2008.00029.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garavito RM, Malkowski MG, DeWitt DL. The structures of prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthases-1 and -2. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2002;68-69:129–152. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(02)00026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith WL, DeWitt DL, Garavito RM. Cyclooxygenases: structural, cellular, and molecular biology. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69(1):145–182. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vane JR. Inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis as a mechanism of action for aspirin-like drugs. Nat New Biol. 1971;231(25):232–235. doi: 10.1038/newbio231232a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vane JR, Bakhle YS, Botting RM. Cyclooxygenases 1 and 2. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1998;38(1):97–120. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.38.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sugiura T, Kondo S, Sukagawa A, Tonegawa T, Nakane S, Yamashita A, Ishima Y, Waku K. Transacylase-mediated and phosphodiesterase-mediated synthesis of N-arachidonoylethanolamine, an endogenous cannabinoid-receptor ligand, in rat brain microsomes. Comparison with synthesis from free arachidonic acid and ethanolamine. Eur J Biochem. 1996;240(1):53–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0053h.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abramovitz M, Metters KM. Prostanoid receptors. Ann Rep Med Chem. 1998;33:223–231. doi: 10.1016/S0065-7743(08)61087-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fowler CJ, Borjesson M, Tiger G. Differences in the pharmacological properties of rat and chicken brain fatty acid amidohydrolase. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;131(3):498–504. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naidu PS, Booker L, Cravatt BF, Lichtman AH. Synergy between enzyme inhibitors of fatty acid amide hydrolase and cyclooxygenase in visceral nociception. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;329(1):48–56. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.143487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sasso O, Bertorelli R, Bandiera T, Scarpelli R, Colombano G, Armirotti A, Moreno-Sanz G, Reggiani A, Piomelli D. Peripheral FAAH inhibition causes profound antinociception and protects against indomethacin-induced gastric lesions. Pharmacol Res. 2012;65(5):553–563. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bishay P, Schmidt H, Marian C, Häussler A, Wijnvoord N, Ziebell S, Metzner J, Koch M, Myrczek T, Bechmann I, Kuner R, Costigan M, Dehghani F, Geisslinger G, Tegeder I. R-flurbiprofen reduces neuropathic pain in rodents by restoring endogenous cannabinoids. PLoS One. 2010;5(5):e10628. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duggan KC, Hermanson DJ, Musee J, Prusakiewicz JJ, Scheib JL, Carter BD, Banerjee S, Oates JA, Marnett LJ. (R)-Profens are substrate-selective inhibitors of endocannabinoid oxygenation by COX-2. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7(11):803–809. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hermanson DJ, Hartley ND, Gamble-George J, Brown N, Shonesy BC, Kingsley PJ, Colbran RJ, Reese J, Marnett LJ, Patel S. Substrate-selective COX-2 inhibition decreases anxiety via endocannabinoid activation. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16(9):1291–1298. doi: 10.1038/nn.3480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Staniaszek LE, Norris LM, Kendall DA, Barrett DA, Chapman V. Effects of COX-2 inhibition on spinal nociception: the role of endocannabinoids. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160(3):669–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00703.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kozak KR, Rowlinson SW, Marnett LJ. Oxygenation of the endocannabinoid, 2-arachidonylglycerol, to glyceryl prostaglandins by cyclooxygenase-2. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(43):33744–33749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007088200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rouzer CA, Marnett LJ. Non-redundant functions of cyclooxygenases: oxygenation of endocannabinoids. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(13):8065–8069. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800005200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Windsor MA, Hermanson DJ, Kingsley PJ, Xu S, Crews BC, Ho W, Keenan CM, Banerjee S, Sharkey KA, Marnett LJ. Substrate-selective inhibition of Cyclooxygenase-2: development and evaluation of achiral Profen probes. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2012;3(9):759–763. doi: 10.1021/ml3001616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Glaser ST, Kaczocha M. Cyclooxygenase-2 mediates anandamide metabolism in the mouse brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;335(2):380–388. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.168831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim J, Alger BE. Inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 potentiates retrograde endocannabinoid effects in hippocampus. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7(7):697–698. doi: 10.1038/nn1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prusakiewicz JJ, Duggan KC, Rouzer CA, Marnett LJ. Differential sensitivity and mechanism of inhibition of COX-2 oxygenation of arachidonic acid and 2-arachidonoylglycerol by ibuprofen and mefenamic acid. Biochemistry. 2009;48(31):7353–7355. doi: 10.1021/bi900999z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fowler CJ, Stenstrom A, Tiger G. Ibuprofen inhibits the metabolism of the endogenous cannabimimetic agent anandamide. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1997;80(2):103–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1997.tb00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fowler CJ, Tiger G, Stenstrom A. Ibuprofen inhibits rat brain deamidation of anandamide at pharmacologically relevant concentrations. Mode of inhibition and structure-activity relationship. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;283(2):729–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garle MJ, Clark JS and Alexander SPH. A fluorescence-derivatisation assay for fatty acid amide hydrolase activity. 2005; pA2 Online. E-journal of the British Pharmacological Society.

- 42.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193(1):265–275. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)52451-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mana H, Spohn U. Sensitive and selective flow injection analysis of hydrogen sulfite/sulfur dioxide by fluorescence detection with and without membrane separation by gas diffusion. Anal Chem. 2001;73(13):3187–3192. doi: 10.1021/ac001049q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.De Bank PA. Kendall DA, Alexander SPH. A spectrophotometric assay for fatty acid amide hydrolase suitable for high throughput screening. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;69(8):1187–1193. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Patricelli MP, Cravatt BF. Fatty acid amide hydrolase competitively degrades bioactive amides and esters through a nonconventional catalytic mechanism. Biochemistry. 1999;38(43):14125–14130. doi: 10.1021/bi991876p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ueda N, Yamanaka K, Terasawa Y, Yamamoto S. An acid amidase hydrolyzing anandamide as an endogenous ligand for cannabinoid receptors. FEBS Lett. 1999;454(3):267–270. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00820-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ueda N, Yamanaka K, Yamamoto S. Purification and characterization of an acid amidase selective for N-palmitoylethanolamine, a putative endogenous anti-inflammatory substance. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(38):35552–35557. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106261200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boger DL, Fecik RA, Patterson JE, Miyauchi H, Patricelli MP, Cravatt BF. Fatty acid amide hydrolase substrate specificity. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2000;10(23):2613–2616. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(00)00528-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wakamatsu K, Masaki T, Itoh F, Kondo K, Sudo K. Isolation of fatty acid amide as an angiogenic principle from bovine mesentery. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;168(2):423–429. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)92338-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zaitone SA, El-Wakeil AF, Abou-El-Ela SH. Inhibition of fatty acid amide hydrolase by URB597 attenuates the anxiolytic-like effect of acetaminophen in the mouse elevated plus-maze test. Behav Pharmacol. 2012;23(4):417–425. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3283566065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maccarrone M, Bari M, Menichelli A, del Principe D, Finazzi Agrò A. Anandamide activates human platelets through a pathway independent of the arachidonate cascade. FEBS Lett. 1999;447(2-3):277–282. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00308-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bertolacci L, Romeo E, Veronesi M, Magotti P, Albani C, Dionisi M, Lambruschini C, Scarpelli R, Cavalli A, de Vivo M, Piomelli D, Garau G. A binding site for nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in fatty acid amide hydrolase. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135(1):22–25. doi: 10.1021/ja308733u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Giang DK, Cravatt BF. Molecular characterization of human and mouse fatty acid amide hydrolases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(6):2238–2242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Piomelli D, Tarzia G, Duranti A, Tontini A, Mor M, Compton TR, Dasse O, Monaghan EP, Parrott JA, Putman D. Pharmacological profile of the selective FAAH inhibitor KDS-4103 (URB597) CNS Drug Rev. 2006;12(1):21–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2006.00021.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wei BQ, Mikkelsen TS, McKinney MK, et al. A second fatty acid amide hydrolase with variable distribution among placental mammals. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(48):36569–36578. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606646200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Favia AD, Habrant D, Scarpelli R, Migliore M, Albani C, Bertozzi SM, Dionisi M, Tarozzo G, Piomelli D, Cavalli A, de Vivo M. Identification and characterization of carprofen as a multitarget fatty acid amide hydrolase/cyclooxygenase inhibitor. J Med Chem. 2012;55(20):8807–8826. doi: 10.1021/jm3011146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fowler CJ, Holt S, Tiger G. Acidic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs inhibit rat brain fatty acid amide hydrolase in a pH-dependent manner. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2003;18(1):55–58. doi: 10.1080/1475636021000049726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Holt S, Nilsson J, Omeir R, Tiger G, Fowler CJ. Effects of pH on the inhibition of fatty acid amidohydrolase by ibuprofen. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;133(4):513–520. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bisogno T, Sepe N, Melck D, et al. Biosynthesis, release and degradation of the novel endogenous cannabimimetic metabolite 2-arachidonoylglycerol in mouse neuroblastoma cells. Biochem J. 1997;322(Pt 2):671–677. doi: 10.1042/bj3220671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hillard CJ, Wilkison DM, Edgemond WS, Campbell WB. Characterization of the kinetics and distribution of N-arachidonylethanolamine (anandamide) hydrolysis by rat brain. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1257(3):249–256. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(95)00087-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Maurelli S, Bisogno T, De Petrocellis L, et al. Two novel classes of neuroactive fatty acid amides are substrates for mouse neuroblastoma 'anandamide amidohydrolase'. FEBS Lett. 1995;377(1):82–86. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01311-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Patricelli MP, Lashuel HA, Giang DK, Kelly JW, Cravatt BF. Comparative characterization of a wild type and transmembrane domain-deleted fatty acid amide hydrolase: identification of the transmembrane domain as a site for oligomerization. Biochemistry. 1998;37(43):15177–15187. doi: 10.1021/bi981733n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ueda N, Kurahashi Y, Yamamoto S, Tokunaga T. Partial purification and characterization of the porcine brain enzyme hydrolyzing and synthesizing anandamide. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(40):23823–23827. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.40.23823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Desarnaud F, Cadas H, Piomelli D. Anandamide amidohydrolase activity in rat brain microsomes. Identification and partial characterization. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(11):6030–6035. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.11.6030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dainese E, Oddi S, Simonetti M, Sabatucci A, Angelucci CB, Ballone A, Dufrusine B, Fezza F, de Fabritiis G, Maccarrone M. The endocannabinoid hydrolase FAAH is an allosteric enzyme. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):2292. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-59120-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Holt S, Paylor B, Boldrup L, Alajakku K, Vandevoorde S, Sundström A, Cocco MT, Onnis V, Fowler CJ. Inhibition of fatty acid amide hydrolase, a key endocannabinoid metabolizing enzyme, by analogues of ibuprofen and indomethacin. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;565(1-3):26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Scott HE. Anti-inflammatory agents. MERCK veterinary manuals. 2014 Retrieved January 21, 2015 from Dialog database on worldwide web DOI: http://www.merckmanuals.com/vet/pharmacology/anti-inflammatory _agents/nonsteroidal_anti-inflammatory_drugs.html.

- 68.Dongdem JT, Dawson SP, Alexander SPH. Characterization of [3-(3-carbamoylphenyl) phenyl] N-cyclohexyl carbamate, an inhibitor of FAAH: effect on rat liver FAAH and HEK293T-FAAH-2 deamination of oleamide, arachidonamide and stearoylamide. Asian J Pharmacol Toxicol. 2016;04:01–11. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lichtman AH, Naidu PS, Booker L, et al. Targetting FAAH and COX to treat visceral pain. FASEB J 2008; 22: . DOI: 10.1096/fasebj.22.1_supplement.1125.12.

- 70.Guindon J, LoVerme J, De Lean A, et al. Synergistic antinociceptive effects of anandamide, an endocannabinoid, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in peripheral tissue: a role for endogenous fatty-acid ethanolamides? Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;550(1-3):68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Naidu PS and Lichtman AH. Synergistic antinociceptive effects of URB597 and diclofenac in a mouse visceral pain model. . In: 17th Annual symposium on the cannabinoids, Vermont International Cannabioid Research Society Burlington, Vermont USA, 2007.

- 72.Blain H, Boileau C, Lapicque F, Nédélec E, Lœuille D, Guillaume C, Gaucher A, Jeandel C, Netter P, Jouzeau JY. Limitation of the in vitro whole blood assay for predicting the COX selectivity of NSAIDs in clinical use. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;53(3):255–265. doi: 10.1046/j.0306-5251.2001.01533.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mitchell JA, Akarasereenont P, Thiemermann C, Flower RJ, Vane JR. Selectivity of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs as inhibitors of constitutive and inducible cyclooxygenase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(24):11693–11697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rao P, Knaus EE. Evolution of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibition and beyond. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2008;11:81s–110s. doi: 10.18433/j3t886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Warner TD, Giuliano F, Vojnovic I, Bukasa A, Mitchell JA, Vane JR. Nonsteroid drug selectivities for cyclo-oxygenase-1 rather than cyclo-oxygenase-2 are associated with human gastrointestinal toxicity: a full in vitro analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(13):7563–7568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.