Abstract

Background:

Higher cumulative burden of depression among people with HIV (PWH) is associated with poorer health outcomes; however, longitudinal relationships with neurocognition are unclear. This study examined hypotheses that among PWH: 1) higher cumulative burden of depression would relate to steeper declines in neurocognition, and 2) visit-to-visit depression severity would relate to neurocognition within persons.

Setting:

Data was collected at a university-based research center from 2002–2016.

Methods:

Participants included 448 PWH followed longitudinally. All participants had >1 visit (M=4.97; SD=3.53) capturing depression severity (Beck Depression Inventory-II) and neurocognition (comprehensive test battery). Cumulative burden of depression was calculated using an established method that derives weighted depression severity scores by time between visits and total time on study. Participants were categorized into low (67%), medium (15%), and high (18%) depression burden. Multilevel modeling examined between- and within-person associations between cumulative depression burden and neurocognition over time.

Results:

The high depression burden group demonstrated steeper global neurocognitive decline compared to the low depression burden group (b=−0.100, p=0.001); this was driven by declines in executive functioning, delayed recall, and verbal fluency. Within-person results showed that compared to visits when participants reported minimal depressive symptoms, their neurocognition was worse when they reported mild (b=−0.12 p=0.04) or moderate-to-severe (b=−0.15, p=0.03) symptoms; this was driven by worsened motor skills and processing speed.

Conclusions:

High cumulative burden of depression is associated with worsening neurocognition among PWH, which may relate to poor HIV-related treatment outcomes. Intensive interventions among severely depressed PWH may benefit physical, mental, and cognitive health.

Keywords: cognition, psychological stress, aging, chronic disease, comorbidity

INTRODUCTION

Depression is one of the most common neuropsychiatric conditions among people with HIV (PWH) worldwide1,2. Reported rates of depression have been estimated as high as 37%1,3,4— a prevalence five times greater than that of the general population5. The relationship between HIV and depression appears to be somewhat reciprocal in nature, such that individuals with depression are at higher risk for acquiring HIV and PWH are at higher risk for developing depression6,7. The latter directional association has been widely researched, with studies suggesting both biological (e.g., changes in brain structure and function, HIV-related physiological fatigue) and psychosocial factors (e.g., HIV stigma, stress of living with a chronic illness, psychiatric vulnerability to major depression) contributing to depression risk among PWH8,9.

The consequences of depression among PWH are multifaceted, including worse quality of life, poorer medication adherence, worse viral suppression, faster HIV disease progression, and mortality2. Although depression has been associated with neurocognitive decline in the general population and in specific clinical populations (i.e., Alzheimer’s disease)10–12, findings among PWH have been somewhat inconsistent13,14. Cross-sectional studies more consistently demonstrate significant relationships between depressive symptoms and neurocognitive functioning among PWH13; however, the few longitudinal studies that exist in this population show inconsistent results. These inconsistencies may be partly explained by their failure to capture long-term severity and chronicity, or “cumulative burden,” of depression. For example, most of the existing longitudinal studies examine the likelihood of neurocognitive decline based on either presence of past major depressive disorder (MDD) and/or depression measured at a single timepoint14,15. Studies across populations, however, show that combined severity and chronicity of depression may be a stronger predictor of neurocognitive performance compared to that of depressive symptomology characterized at a single time point16,17.

Accounting for long-term, cumulative burden of depression may help clarify longitudinal relationships between depression and neurocognitive functioning among PWH. For example, elevated depressive symptoms can detrimentally impact performance during neurocognitive testing (e.g., information processing speed, timed psychomotor tasks), but such deficits in test performance often resolve with alleviation of depressive symptoms18. In contrast, recent findings suggest that more chronic and severe depression is associated with long-term neurobiological (e.g., neuroinflammation, glucocorticoid cascade) and behavioral consequences (e.g., decreased engagement in cognitive and physical activities) that are known to adversely affect neurocognition19,20. Given that neurocognitive impairment remains prevalent in the current antiretroviral era21, understanding the impact of treatable conditions (e.g., depression) on neurocognitive decline is imperative for developing appropriate intervention plans for maintaining optimal cognitive health.

Thus, the current study included two aims to examine longitudinal associations between depressive symptoms and cognitive functioning among PWH. The first study aim was to examine the between-person association between cumulative depression burden and global neurocognitive decline over time (i.e., across all study visits). We hypothesized that participants with higher cumulative depression burden would have faster global neurocognitive decline (i.e., negative slopes of greater magnitude) than those with lower cumulative depression burden. The second study aim was to examine within-person associations between visit-to-visit depressive symptom severity and global neurocognitive functioning. We hypothesized that participants would exhibit worse global neurocognitive performance on visits when they had worse depressive symptoms. For each aim, we also explored neurocognitive domain-specific outcomes to aid interpretation of global findings.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were 448 PWH enrolled in NIH-funded longitudinal studies at the UCSD HIV Neurobehavioral Research Program (HNRP) from 2002–2016. All the studies from which participants in the current study were pulled have specific aims that fall under the broad scientific aim of examining the effects of HIV on the central nervous system. Assessments and procedures are also standardized and consistent across all studies. Participants were included in the current study if they had at least two complete visits. Visits that occurred more than 10 years since baseline (i.e., about two standard deviations from the mean) were excluded as there were not enough data to robustly estimate slopes for cognitive change more than 10 years from baseline. Participants were included even if they missed visits in between complete visits. Exclusion criteria consistent among all parent studies were diagnosis of a psychotic disorder and presence of a neurological condition known to impact neurocognitive functioning (e.g., stroke). Additional exclusion criteria for the current study included DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of current dependence on any substances of abuse at the baseline visit, including alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, hallucinogens, inhalants, methamphetamine, opioids, and sedatives. All study procedures were approved by the UCSD Institutional Review Board. Participants provided written, informed consent.

Measures

Current Depressive Symptom Severity and Cumulative Burden of Depression.

The second edition Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) was administered to assess depressed mood at each visit. These BDI-II scores were categorized by severity based on recommended clinical cutoffs: none-to-minimal (0–13); mild (14–19); moderate-to-severe (≥20)22. Cumulative burden of depression across all visits for each individual was calculated based on established methods as follows23. First, BDI-II scores were converted to a scale ranging from 0 to 1, such that scores ≥20 were assigned a value of 1, scores <14 were assigned a value of 0, and scores 14–19 were assigned a value that is weighted proportionally between 0 and 1. Weighted averages for each individual across all their visits were then calculated based on the number of days between each visit. Specifically, the converted BDI-II scores were averaged over a given interval, then multiplied by the number of days in that interval. The resulting values for each interval were summed and then divided by the total number of days from first to last visit. This resulted in one total cumulative burden of depression score (ranging from 0 to 1) for each participant. This method has been validated previously, and represents the inverse of the commonly used “depression-free days” metric that is used across clinical trials to evaluate effectiveness of depression treatments23,24. Last, in order to evaluate cognitive decline by cumulative depression burden severity groups, final values were categorized to indicate a low depression burden group (participants with scores <0.33), a medium depression burden group (participants with scores between 0.33 and 0.67), and a high depression burden group (participants with scores >0.67).

Psychiatric and Neuromedical Assessment.

Modules of the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI, v2.1) were administered to assess for current and past (occurring >12 months ago) mood and substance use disorders based on the DSM-IV-TR. All participants were tested for HIV using a fingerstick test (Medmira, Nova Scotia, Canada) and confirmed with an Abbott RealTime HIV-1 test (Abbott Laboratories, Illinois, USA) or by submitting specimens to a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-certified laboratory (ARUP Laboratories, Utah, USA) for HIV-1 viral load quantitation. At each visit, additional HIV characterization included AIDS status, plasma viral load, CD4+ T-cell counts (nadir and current), estimated duration of HIV disease, and current antiretroviral therapy (ART) regimen.

Neurocognitive Assessment.

At each visit, participants completed a standardized battery of well-validated neuropsychological tests assessing seven cognitive domains: verbal fluency, executive functioning, speed of information processing (i.e., processing speed), learning, delayed recall, working memory, and speeded fine motor skills25. Raw test scores were converted to practice-effect corrected scaled scores (M=10; SD=3 in normative sample), which subtract a median practice-effect from the observed scaled score based on the number of testings26. Scaled scores were averaged across all tests to create a global scaled score, and averaged within each domain to create domain-specific scaled scores. Scaled scores were not corrected for demographics, as neurocognitive change is best measured using scores that do not remove reliable sources of variance in change over time (e.g., age)27.

Statistical Analyses

To compare baseline demographic and clinical characteristics by cumulative depression burden group, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or chi-squared analysis was used for continuous or dichotomous variables, respectively. Nonparametric Wilcoxon tests were used for non-normally distributed continuous variables (i.e., CD4 counts). Pairwise comparisons were examined using Tukey’s HSD for continuous outcomes or Bonferroni adjustments for dichotomous outcomes. ANOVA and Pearson correlations were also used to examine predictors of length of follow up (i.e., total years on study), including depression burden group, demographics, and HIV disease characteristics.

Next, a multilevel model was used to examine between- and within-person predictors of global neurocognitive performance, as multilevel models are able to account for the repeated measures nature of the data (i.e., multiple visits [at level 1] nested within participants [level 2])28. The effect of time (i.e., years since baseline) was modeled as a random slope allowing the relationship between time and global scaled score to vary by participants (i.e., modeling a cognitive change trajectory for each person), and thus allowing us to examine cumulative depression burden as a between-person predictor of this random slope. In other words, at the between-person level of the multilevel model, cumulative depression burden group was modeled as a moderator of the relationship between neurocognition and time. Cumulative depression burden group, mean age, sex, baseline education, and baseline nadir CD4 count<200 also predicted global scaled score averaged over each individual’s visits at the between-person level. At the within-person level of the multilevel model, depressive symptom severity was used to predict global scaled score at each visit, covarying for time-varying HIV disease severity (i.e., current CD4 count<200 [yes vs. no]). Random intercepts were specified. This statistical model was repeated for each neurocognitive domain outcome to explore domain-specific effects. Unstandardized model estimates are reported. Given that examination of domain-specific outcomes was exploratory, no corrections for multiple comparisons were applied.

To aid interpretation of results, four additional analyses were conducted. 1) In order to understand whether depression longitudinally relates to HIV medication adherence (a possible mechanism underlying cognitive change), we used a multilevel model to examine the within-person effect of visit-specific BDI-II score on log-transformed HIV plasma viral load (i.e., a proxy for ART adherence) among only participants on ART. 2) An additional multilevel model was examined to determine differences in cognitive change trajectories among the high depression burden group by antidepressant use. 3) Additional within-person longitudinal analyses also examined trajectories of change in BDI-II scores over time in each depression burden group, allowing us to understand whether BDI-II scores generally increased or decreased over time. For these analyses, the relationship between BDI-II score and time was modeled specifying random slopes and intercepts. 4) Last, a sensitivity analysis removing all female participants was completed to ensure that between- and within-person relationships between depression and global neurocognition were not being driven by women, as depression has previously been found to be a stronger predictor of neurocognition among women living with HIV29. All baseline analyses were conducted using JMP Pro version 14.0.0 (JMP®, Version 14.0.0. SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, 1989–2007). All longitudinal analyses were conducted using Mplus, version 7.4.

RESULTS

Of the 448 participants, there were 301 (67.2%) participants with low depression burden, 69 (15.4%) participants with medium depression burden, and 78 (17.4%) participants with high depression burden. Participants had a mean of 4.97 complete visits (SD=3.53; min=2; max=15) that were about 0.89 years apart on average (SD=0.63), with no more than 10 years from baseline to last visit (M=3.88 years; SD=2.94; min=0.50; max=10.0). Baseline (i.e., first visit) demographic and clinical characteristics of each cumulative depression burden group are displayed in Table 1. At baseline, the high cumulative depression burden group was older than the medium depression burden group (p=0.04). Groups were comparable on all other demographic and HIV disease characteristics. Regarding psychiatric characteristics, groups with higher cumulative depression burden severity had higher rates of MDD, higher BDI-II scores, and more antidepressant use, consistent with expectations. Additionally, the medium depression burden group had a higher rate of past SUDs compared to the low depression burden group. Groups also had comparable baseline global and domain-specific neurocognitive performance. Last, length of follow up was not related to depression burden group, demographics, or HIV disease characteristics (ps>0.05).

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Participants Living with HIV (N = 448)

| Cumulative Depression Burden Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A Low (n=301) | B Medium (n=69) | C High (n=78) | p-value | Pairwise Comparisons | |

| Demographics | |||||

| Age (years) | 44.03 (10.34) | 41.84 (8.73) | 45.97 (8.94) | 0.040 | C > B |

| Education (years) | 13.30 (2.53) | 12.90 (2.90) | 13.08 (2.62) | 0.456 | |

| Sex (% female) | 44 (14.6%) | 11 (15.9%) | 16 (20.5%) | 0.481 | |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.468 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 140 (46.5%) | 40 (58.0%) | 42 (53.8%) | ||

| Black | 101 (33.6%) | 21 (30.4%) | 24 (30.8%) | ||

| Hispanic | 44 (14.6%) | 8 (11.6%) | 9 (11.5%) | ||

| Asian | 2 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.3%) | ||

| Other | 14 (4.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (2.6%) | ||

| WRAT4 Reading | 96.82 (13.70) | 97.91 (13.44) | 95.87 (13.67) | 0.728 | |

| Total years on study | 4.00 (2.96) | 3.67 (2.98) | 3.55 (2.87) | 0.398 | |

| Psychiatric and Medical Characteristics | |||||

| Current MDD (% yes) | 13 (4.3%) | 15 (21.7%) | 30 (38.5%) | <0.001 | A < B < C |

| Lifetime MDD (% yes) | 111 (36.9%) | 47 (68.1%) | 60 (76.9%) | <0.001 | A < B,C |

| BDI-II score | 8.19 (7.25) | 21.06 (8.23) | 27.57 (8.44) | <0.001 | A < B < C |

| Any past SUD (% yes) | 171 (56.8%) | 57 (82.6%) | 59 (75.6%) | <0.001 | A < B |

| Hepatitis C infection (% yes) | 59 (19.6%) | 16 (23.2%) | 12 (15.4%) | 0.458 | |

| On antidepressant medication | 85 (28.2%) | 30 (43.5%) | 45 (57.7%) | <0.001 | A < B,C |

| HIV Disease Characteristics | |||||

| History of AIDS (% AIDS) | 185 (61.5%) | 37 (53.6%) | 47 (60.3%) | 0.433 | |

| Nadir CD4 | 155 [26–316] | 197 [66–390] | 180 [60–286] | 0.265 | |

| Current CD4 | 448 [270–675] | 491 [204–721] | 494 [323–677] | 0.573 | |

| Estimated Duration of HIV Disease | 10.21 (7.25) | 10.95 (7.33) | 11.17 (7.29) | 0.495 | |

| Plasma viral load (% undetectable) | 215 (71.4%) | 43 (62.3%) | 56 (71.8%) | 0.586 | |

| On ART (% yes) | 217 (72.1%) | 47 (68.1%) | 59 (75.6%) | 0.597 | |

| Neurocognitive Scaled Scores (SS) | |||||

| Global | 9.06 (1.94) | 8.81 (2.22) | 8.67 (1.79) | 0.250 | |

| Verbal Fluency | 10.09 (2.19) | 10.05 (2.26) | 9.61 (2.28) | 0.239 | |

| Executive Functioning | 8.65 (2.64) | 8.81 (3.08) | 8.52 (2.41) | 0.812 | |

| Processing Speed | 9.81 (2.45) | 9.42 (2.91) | 9.38 (2.25) | 0.272 | |

| Learning | 7.75 (2.26) | 7.54 (2.73) | 7.59 (2.13) | 0.754 | |

| Delayed Recall | 8.51 (2.72) | 8.40 (2.87) | 8.32 (2.56) | 0.844 | |

| Working Memory | 9.26 (2.73) | 8.81 (2.97) | 8.86 (2.62) | 0.309 | |

| Motor Skills | 8.74 (2.51) | 8.51 (2.92) | 7.91 (2.96) | 0.054 | |

Note. Values are displayed as mean (SD), median [IQR] or n (%). Bolded p-values are significant at p<0.05. WRAT4 Reading = Wide Range Achievement Test, 4th Edition Reading subtest; MDD = major depressive disorder; BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-2nd Edition; SUD = substance use disorder; ART = antiretroviral therapy.

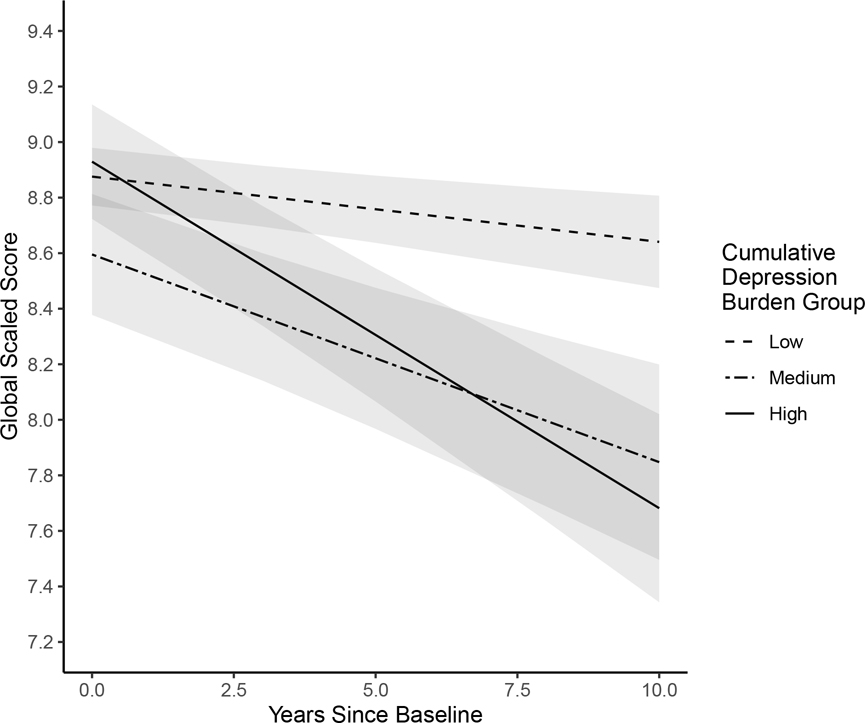

Results of the multilevel model examining between- and within-person predictors of global neurocognitive functioning are presented in Table 2. At the between-person level, participants in the high depression burden group had significantly steeper declines in global neurocognitive functioning over time compared to the low depression burden group (b=−0.100, p=.001; Figure 1). The medium depression burden group also had marginally significantly steeper declines in global neurocognition over time compared to the low burden group (b=−0.059, p=0.057). The rate of decline among the high depression burden group did not differ significantly from that of the medium burden group (when specifying the medium burden group as the reference; b=−0.050, p=0.223). Within-person results indicated that on visits when participants reported mild (b=−0.119, p=0.042) or moderate-to-severe (b=−0.150, p=0.026) depressive symptoms on the BDI-II, they had worse global neurocognitive functioning compared to visits when they reported none-to-minimal depressive symptoms.

Table 2.

Results of multilevel model examining between- and within-person effects of depression severity on global cognition and global cognitive decline

| Estimate | SE | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Between-person Level | |||

| Outcome: Random Slope (Global SS on Years) | |||

| Intercept | −0.020 | 0.013 | .117 |

| Medium cumulative depression burdenb | −0.059 | 0.031 | .057 |

| High cumulative depression burdenb | −0.100 | 0.031 | .001 |

| Outcome: Average Global SS | |||

| Medium cumulative depression burdenb | −0.284 | 0.234 | .224 |

| High cumulative depression burdenb | 0.027 | 0.228 | .906 |

| Mean age (years) | −0.084 | 0.009 | <.001 |

| Sex (female vs. male) | 0.246 | 0.232 | .287 |

| Baseline education (years) | 0.299 | 0.033 | <.001 |

| Baseline nadir CD4<200 (yes vs. no) | −0.314 | 0.173 | .070 |

| Within-person Level | |||

| Outcome: Global Scaled Score (SS) | |||

| Mild depressive symptomsa | −0.119 | 0.058 | .042 |

| Moderate-to-severe depressive symptomsa | −0.150 | 0.067 | .026 |

| Current CD4<200 (yes vs. no) | −0.087 | 0.081 | .283 |

Note. Bolded p-values are significant at p<0.05.

Compared to none-to-minimal depressive symptoms

Compared to low cumulative depression burden

Figure 1.

Trajectories of global neurocognitive change over a 10-year period by cumulative depression burden group. Intercepts, slopes, and 95%CI bands were derived from multilevel model estimates.

Examination of neurocognitive domain-specific outcomes (Table 3) revealed the between-person effect of high depression burden on global neurocognitive decline (compared to that of low depression burden) was primarily driven by declines in executive functioning (b=−0.152, p=0.020), delayed recall (b=−0.131, p=0.023), and verbal fluency (b=−0.096, p=0.045). The medium depression burden group also demonstrated significantly steeper declines in executive functioning (b=−.133, p=0.039) and verbal fluency (b=−.153, p=0.001), compared to the low depression burden group. Notably, a different pattern emerged at the within-person level for each domain. The within-person effects of visit-to-visit changes in depressive symptom severity on global neurocognition appeared to be driven by speeded fine motor skills and processing speed.

Table 3.

Multilevel model results for each neurocognitive domain outcome; values are regression estimate (SE)

| Neurocognitive Domain Outcome | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Between-person Level | Verbal Fluency | Executive Functioning | Processing Speed | Learning | Delayed Recall | Working Memory | Motor Skills |

| Outcome: Random Slope (Cognitive Domain SS on Years) | |||||||

| Intercept | −0.021 (0.020) | 0.044 (0.026) | −0.012 (0.020) | 0.021 (0.025) | −0.065 (0.024)** | −0.019 (0.020) | −0.114 (0.024)*** |

| Medium cumulative depression burdenb | −0.153 (0.047)** | −0.133 (0.064)* | −0.097 (0.049)† | −0.049 (0.058) | −0.041 (0.056) | 0.028 (0.047) | 0.001 (0.057) |

| High cumulative depression burdenb | −0.096 (0.048)* | −0.152 (0.065)* | −0.078 (0.049) | −0.086 (0.059) | −0.131 (0.058)* | −0.023 (0.048) | −0.111 (0.057)† |

| Outcome: Average Cognitive Domain SS | |||||||

| Medium cumulative depression burdenb | 0.215 (0.279) | 0.046 (0.314) | −0.304 (0.301) | −0.419 (0.317) | −0.452 (0.325) | −0.379 (0.334) | −0.456 (0.324) |

| High cumulative depression burdenb | −0.168 (0.278) | 0.477 (0.320) | 0.052 (0.296) | −0.066 (0.319) | −0.088 (0.328) | −0.130 (0.329) | −0.223 (0.324) |

| Mean age (years) | −0.047 (0.010)*** | −0.120 (0.011)*** | −0.079 (0.011)*** | −0.085 (0.011)*** | −0.084 (0.011)*** | −0.046 (0.012)*** | −0.135 (0.012)*** |

| Sex (female vs. male) | −0.099 (0.271) | 0.284 (0.299) | 0.661 (0.296)* | 0.252 (0.307) | 0.412 (0.311) | −0.070 (0.327) | 0.227 (0.315) |

| Baseline education (years) | 0.247 (0.039)*** | 0.345 (0.043)*** | 0.341 (0.042)*** | 0.307 (0.044)*** | 0.285 (0.044)*** | 0.331 (0.047)*** | 0.192 (0.045)*** |

| Baseline nadir CD4<200 (yes vs. no) | −0.099 (0.203) | −0.271 (0.224) | −0.270 (0.221) | −0.364 (0.229) | −0.408 (0.233)† | −0.282 (0.245) | −0.307 (0.236) |

| Within-person Level | |||||||

| Outcome: Cognitive Domain SS | |||||||

| Mild depressive symptomsa | −0.029 (0.098) | −0.175 (0.133) | −0.064 (0.089) | −0.131 (0.120) | −0.108 (0.128) | −0.060 (0.102) | −0.391 (0.111)*** |

| Moderate-to-severe depressive symptomsa | 0.001 (0.113) | −0.137 (0.154) | −0.256 (0.103)** | −0.126 (0.140) | 0.007 (0.149) | −0.161 (0.118) | −0.471 (0.129)*** |

| Current CD4<200 (yes vs. no) | −0.091 (0.131) | −0.290 (0.174)† | −0.137 (0.122) | −0.144 (0.160) | −0.097 (0.170) | −0.241 (0.139)† | −0.035 (0.150) |

Compared to none-to-minimal depressive symptoms

Compared to low depression burden

p<0.10

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

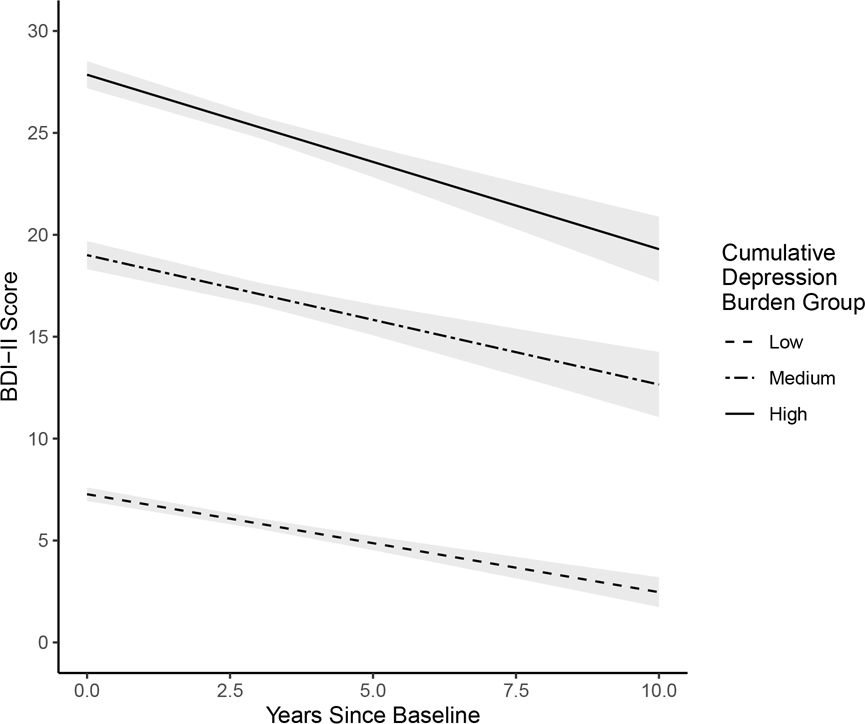

The first additional analysis examining the within-person effect of visit-specific BDI-II score on log-transformed HIV plasma viral load (covarying for mean age, sex, education, and depression burden group) among only those on ART (n=323) showed that compared to visits when participants reported no/minimal depressive symptoms, they had higher viral loads on visits when they reported either mild (b=0.257, p=0.001) or moderate-to-severe (b=0.244, p=0.009) depressive symptoms. The second additional analysis examining differences in cognitive change trajectories by antidepressant use among the high depression burden group (n=78) showed a significant interaction between antidepressant use and time (i.e., years since baseline) on global cognitive performance (b=−0.159; p=0.033) such that participants on antidepressants demonstrated a steeper decline (b=−0.213; p<0.001) than those who were not on antidepressants (b=−0.022; p=0.707). The third additional analysis exploring trajectories of change in BDI-II scores over time within each depression burden group showed that BDI-II scores slowly decreased over time for each group (low burden group: b=−0.494, SE=0.081, p<0.001; medium burden group: b=−0.482, SE=0.236, p=0.051; high burden group: b=−0.817, SE=0.201, p<0.001). Examination of model estimates showed that although BDI-II score decreased over time, scores generally stayed within respective clinical ranges for each group (see Figure 2). Finally, the sensitivity analysis removing all female participants from the sample did not change the results of the primary analyses examining within- and between-person relationships between depression and global cognition.

Figure 2.

Change in BDI-II score over time by cumulative depression burden group. Intercepts, slopes, and 95%CI bands were derived from multilevel model estimates.

DISCUSSION

Given the high rates of depression and neurocognitive impairment among PWH, there was a strong and compelling rationale to examine how these conditions related to one another. Consistent with our first hypothesis, higher depression burden was associated with faster declines in global neurocognitive functioning from baseline to last visit. The apparent rank ordering of the cumulative depression burden groups with regard to their rates of neurocognitive decline also suggest a dose-response relationship between depression burden and neurocognitive decline. Consistent with our second hypothesis, we also found an association between acute, visit-to-visit depressive symptom severity and global neurocognitive performance within persons, such that participants had lower global cognitive scaled scores on visits when they reported more severe depressive symptoms. Interestingly, these two findings were driven by different neurocognitive domains, possibly suggesting different mechanisms underlying these relationships.

Our finding that PWH with the highest depression burden exhibited faster global cognitive decline compared to PWH with the lowest depression burden is a novel result within this population. This finding, however, is consistent with recent literature in the general older adult population showing that greater long-term, cumulative depressive symptom severity over several evaluations is associated with higher risk for developing dementia17. Notably, our domain-specific analyses also demonstrated that the effect of high depression burden on global neurocognitive decline was driven by declines in executive functioning, delayed recall, and verbal fluency. These domains are some of the most commonly affected in the context of HIV disease30, which may suggest an overlap in neurobiological mechanisms of cognitive dysfunction in depression and HIV13. Deficits in executive functioning and delayed recall, in particular, are also associated with poor everyday functioning outcomes (e.g., medication non-adherence, poor healthcare engagement), highlighting the clinical relevance of our finding31. Additional analyses exploring trajectories of BDI-II score change among the three depression burden groups suggests that the observed declines were not simply due to corresponding increases in depression severity over time. In fact, results showed small but significant decreases in BDI-II score over time, suggesting that our data likely captured the outcome of underlying adverse neurobiological processes, rather than just behavioral manifestations of worsening depression. The slight decreases in depressive symptoms over time may also be consistent with the theory of emotional aging whereby psychological well-being generally increases from middle to older age32.

There are a number of possible mechanisms that may drive the relationship between cumulative depression burden and neurocognitive decline among PWH. In the context of HIV disease, depression is strongly associated with non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy33. This appears to be true in our sample as well, as supported by the result showing a positive within-person relationship between depressive symptom severity and HIV plasma viral load. This may lead to faster HIV disease progression and subsequent HIV-related neurocognitive impairment34. Neurobiological studies of depression have also found that sustained depressive symptoms and stress can lead to chronic neuroinflammation and a glucocorticoid cascade causing subsequent neuronal damage19. Coupled with the neuroinflammation and neuronal damage caused by HIV in the brain35, chronic depression may inflict detrimental additive or synergistic effects on brain integrity among PWH. Notably, we found that individuals in the high depression burden group who were on antidepressants had the steepest cognitive decline. While mechanisms underlying this relationship are unclear, it is possible that this group was perhaps the most clinically severe (as indicated by their having a prescription antidepressant medication). Next, psychosocial factors may also play a role. For example, depression is known to relate to decreased engagement in physical, social, and cognitively stimulating activities, all of which are protective factors against cognitive decline among older adult populations36,37. Last, it is important to highlight that although this study utilizes longitudinal data, causal conclusions cannot be drawn from the between or within-person effects. Thus, it is possible that the participants who experienced the most neurocognitive decline also experienced the highest levels of depression possibly due to awareness of their decline38 and/or to lowered cognitive ability needed to regulate emotions39.

Our within-person finding that depressive symptom severity was negatively associated with global neurocognitive performance at each visit is also consistent with other recent longitudinal work showing an acute effect of depression severity on test performance18. Interestingly, this within-person association was driven primarily by the neurocognitive domains of speeded fine motor skills and speed of information processing, which is highly consistent with the clinical presentation of depression. This finding demonstrates that not only are speeded fine motor skills and processing speed worse on visits when depressive symptoms are more severe, but that there is improvement in these domains on visits when one’s depressive symptoms subside. The distinction between the current within-person and between-person effects of depression severity on neurocognitive function highlight differences between acute and chronic (long-term) cognitive outcomes that cannot be distinguished when examining cross-sectional data from only one visit40,41.

This study importantly covaried for factors known to impact neurocognitive functioning, including demographics and HIV characteristics. Consistent with what is known about the effects of demographics on neuropsychological test performance42, our multilevel models suggest lower mean age and higher baseline education are consistently related to better average neurocognitive performance in all domains. In contrast, current and nadir CD4 counts were not predictive of neurocognition in any domain. While it is well documented that cognition can improve with reduction in HIV disease severity, e.g.43, our lack of significant findings may be related to the nature of our participants, who were healthy and clinically stable enough to be able to participate in our studies over a long period of time.

The current study has strengths, including a large, diverse, longitudinal sample, robust statistical methods, and novel findings; however, it is not without limitations. First, our measure of cumulative depression burden utilized repeated BDI-II assessments over relatively large intervals, which may not accurately estimate mood outside of in-laboratory observation. This method, however, has been previously used to predict important outcomes in HIV (e.g., mortality)23, and has been validated and used extensively in depression treatment literature24. Next, our sample included only PWH, precluding direct comparisons to individuals without HIV; however, given the already extensive literature on depression and cognition in the general population, our goal was to specifically understand these relationships in the context of HIV. Our sample also excluded for current substance dependence, preventing generalizability of our findings to those with co-occurring depression and current substance dependence. Our data were also limited with regard to depression treatment history, including reasons for non-treatment and history of non-pharmacological treatment. Additionally, because our sample of participants was selected for long-term engagement in our comprehensive longitudinal studies, they are likely not representative of the wider population of PWH in the U.S. who may not be as clinically stable. Future work must continue to examine how HIV disease severity may interact with psychiatric conditions (e.g., depression) in the progression of neurocognitive decline.

In summary, the current longitudinal study, using of a large sample of PWH, demonstrated between-person differences in the trajectories of neurocognitive decline by cumulative depression burden severity, as well as within-person fluctuations in neurocognitive performance with corresponding changes in depressive symptoms. Thus, our findings demonstrate both acute effects of depressive symptom severity on neurocognitive performance (particularly in speeded fine motor skills and processing speed) and chronic effects of cumulative depression burden severity on long-term neurocognitive decline. The declining neurocognitive functioning observed among PWH with the highest cumulative burden of depression may also be reciprocally related to the poorer healthcare engagement and HIV-related health outcomes in this group23. Our results support the need for future work that both monitors depression in a more continuous fashion (e.g., between clinical visits via mobile assessment) and examines how both pharmacological and/or psychotherapeutic interventions to treat depression may affect cognitive, mental, and physical health.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The San Diego HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center [HNRC] group is affiliated with the University of California, San Diego, the Naval Hospital, San Diego, and the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System, and includes: Director: Robert K. Heaton, Ph.D., Co-Director: Igor Grant, M.D.; Associate Directors: J. Hampton Atkinson, M.D., Ronald J. Ellis, M.D., Ph.D., and Scott Letendre, M.D.; Center Manager: Thomas D. Marcotte, Ph.D.; Jennifer Marquie-Beck, M.P.H.; Melanie Sherman; Neuromedical Component: Ronald J. Ellis, M.D., Ph.D. (P.I.), Scott Letendre, M.D., J. Allen McCutchan, M.D., Brookie Best, Pharm.D., Rachel Schrier, Ph.D., Debra Rosario, M.P.H.; Neurobehavioral Component: Robert K. Heaton, Ph.D. (P.I.), J. Hampton Atkinson, M.D., Thomas D. Marcotte, Ph.D., Mariana Cherner, Ph.D., David J. Moore, Ph.D., Matthew Dawson; Neuroimaging Component: Christine Fennema-Notestine, Ph.D. (P.I.), Gregory Brown, Ph.D.; Neurobiology Component: Cristian Achim, M.D., Ph.D.; Neurovirology Component: David M. Smith, M.D. (P.I.), Douglas Richman, M.D.; International Component: J. Allen McCutchan, M.D., (P.I.), Mariana Cherner, Ph.D.; Developmental Component: Cristian Achim, M.D., Ph.D.; (P.I.), Scott Letendre, M.D., Ph.D.; Participant Accrual and Retention Unit: J. Hampton Atkinson, M.D. (P.I.), Jennifer Marquie-Beck, M.P.H.; Data Management and Information Systems Unit: Anthony C. Gamst, Ph.D. (P.I.), Clint Cushman; Statistics Unit: Ian Abramson, Ph.D. (P.I.), Florin Vaida, Ph.D. (Co-PI), Bin Tang, Ph.D., Anya Umlauf, M.S.

Sources of Support: Data for this study were collected as part of four larger studies: (1) the HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center (HNRC; NIMH award P30MH062512); (2) the California NeuroAIDS Tissue Network (CNTN; NIMH awards U01MH083506 and R24MH59745); (3) the Translational Methamphetamine AIDS Research Center (TMARC; NIDA award P50DA026306); and (4) the CNS HIV Anti-Retroviral Therapy Effects Research (CHARTER; NIH HHSN271201000036C and HHSN271201000030C).

Additional funding was supported by: NIAAA award F31AA027198 (stipend support to EWP); NIMH award K23MH107260 and NIA award R01AG062387 (salary support to RCM).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, nor the United States Government.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nanni MG, Caruso R, Mitchell AJ, Meggiolaro E, Grassi L. Depression in HIV infected patients: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(1):530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rabkin JG. HIV and depression: 2008 review and update. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2008;5(4):163–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaynes BN, Pence BW, Eron JJ Jr., Miller WC. Prevalence and comorbidity of psychiatric diagnoses based on reference standard in an HIV+ patient population. Psychosom Med. 2008;70(4):505–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bing EG, Burnam MA, Longshore D, et al. Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(8):721–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression.shtml#part_155033: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration;2018.

- 6.Bhatia R, Hartman C, Kallen MA, Graham J, Giordano TP. Persons newly diagnosed with HIV infection are at high risk for depression and poor linkage to care: results from the Steps Study. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(6):1161–1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hutton HE, Lyketsos CG, Zenilman JM, Thompson RE, Erbelding EJ. Depression and HIV risk behaviors among patients in a sexually transmitted disease clinic. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(5):912–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arseniou S, Arvaniti A, Samakouri M. HIV infection and depression. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014;68(2):96–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Atkinson JH Jr., Grant I, Kennedy CJ, Richman DD, Spector SA, McCutchan JA. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among men infected with human immunodeficiency virus. A controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45(9):859–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rock PL, Roiser JP, Riedel WJ, Blackwell AD. Cognitive impairment in depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2014;44(10):2029–2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mourao RJ, Mansur G, Malloy-Diniz LF, Castro Costa E, Diniz BS. Depressive symptoms increase the risk of progression to dementia in subjects with mild cognitive impairment: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31(8):905–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ownby RL, Crocco E, Acevedo A, John V, Loewenstein D. Depression and risk for Alzheimer disease: systematic review, meta-analysis, and metaregression analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(5):530–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rubin LH, Maki PM. HIV, Depression, and Cognitive Impairment in the Era of Effective Antiretroviral Therapy. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2019;16(1):82–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cysique LA, Deutsch R, Atkinson JH, et al. Incident major depression does not affect neuropsychological functioning in HIV-infected men. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2007;13(1):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heaton RK, Franklin DR Jr., Deutsch R, et al. Neurocognitive change in the era of HIV combination antiretroviral therapy: the longitudinal CHARTER study. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(3):473–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cysique LA, Dermody N, Carr A, Brew BJ, Teesson M. The role of depression chronicity and recurrence on neurocognitive dysfunctions in HIV-infected adults. J Neurovirol. 2016;22(1):56–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeki Al Hazzouri A, Vittinghoff E, Byers A, et al. Long-term cumulative depressive symptom burden and risk of cognitive decline and dementia among very old women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69(5):595–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Douglas KM, Porter RJ. Longitudinal assessment of neuropsychological function in major depression. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2009;43(12):1105–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Furtado M, Katzman MA. Examining the role of neuroinflammation in major depression. Psychiatry Res. 2015;229(1–2):27–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verhoeven JE, Revesz D, Epel ES, Lin J, Wolkowitz OM, Penninx BW. Major depressive disorder and accelerated cellular aging: results from a large psychiatric cohort study. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19(8):895–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR Jr., et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study. Neurology. 2010;75(23):2087–2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beck A, Steer R, Brown G. Manual for The Beck Depression Inventory Second Edition (BDI-II). In. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pence BW, Mills JC, Bengtson AM, et al. Association of Increased Chronicity of Depression With HIV Appointment Attendance, Treatment Failure, and Mortality Among HIV-Infected Adults in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(4):379–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vannoy SD, Arean P, Unutzer J. Advantages of using estimated depression-free days for evaluating treatment efficacy. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(2):160–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carey CL, Woods SP, Gonzalez R, et al. Predictive validity of global deficit scores in detecting neuropsychological impairment in HIV infection. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2004;26(3):307–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cysique LA, Franklin D Jr., Abramson I, et al. Normative data and validation of a regression based summary score for assessing meaningful neuropsychological change. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2011;33(5):505–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cysique LA, Casaletto KB, Heaton RK. Reliably Measuring Cognitive Change in the Era of Chronic HIV Infection and Chronic HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorders. In: Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kwok OM, Underhill AT, Berry JW, Luo W, Elliott TR, Yoon M. Analyzing Longitudinal Data with Multilevel Models: An Example with Individuals Living with Lower Extremity Intra-articular Fractures. Rehabilitation psychology. 2008;53(3):370–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rubin LH, Springer G, Martin EM, et al. Elevated Depressive Symptoms Are a Stronger Predictor of Executive Dysfunction in HIV-Infected Women Than in Men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019;81(3):274–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heaton RK, Franklin DR, Ellis RJ, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders before and during the era of combination antiretroviral therapy: differences in rates, nature, and predictors. Journal of Neurovirology. 2011;17(1):3–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heaton RK, Marcotte TD, Mindt MR, et al. The impact of HIV-associated neuropsychological impairment on everyday functioning. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2004;10(3):317–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scheibe S, Carstensen LL. Emotional aging: recent findings and future trends. The journals of gerontology Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences. 2010;65b(2):135–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gonzalez JS, Batchelder AW, Psaros C, Safren SA. Depression and HIV/AIDS treatment nonadherence: a review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;58(2):181–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Becker BW, Thames AD, Woo E, Castellon SA, Hinkin CH. Longitudinal change in cognitive function and medication adherence in HIV-infected adults. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(8):1888–1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hong S, Banks WA. Role of the immune system in HIV-associated neuroinflammation and neurocognitive implications. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;45:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gallagher D, Kiss A, Lanctot K, Herrmann N. Depressive symptoms and cognitive decline: A longitudinal analysis of potentially modifiable risk factors in community dwelling older adults. J Affect Disord. 2016;190:235–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ngandu T, Lehtisalo J, Solomon A, et al. A 2 year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people (FINGER): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9984):2255–2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones JD, Kuhn T, Levine A, et al. Changes in cognition precede changes in HRQoL among HIV+ males: Longitudinal analysis of the multicenter AIDS cohort study. Neuropsychology. 2019;33(3):370–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Opitz PC, Lee IA, Gross JJ, Urry HL. Fluid cognitive ability is a resource for successful emotion regulation in older and younger adults. Front Psychol. 2014;5:609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Piantadosi S, Byar DP, Green SB. The ecological fallacy. American journal of epidemiology. 1988;127(5):893–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robinson WS. Ecological Correlations and the Behavior of Individuals. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;38(2):337–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heaton RK, Miller SW, Taylor MJ, Grant I. Revised comprehensive norms for an expanded Halstead-Reitan Battery: Demographically adjusted neuropsychological norms for African American and Caucasian adults. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sacktor N, Saylor D, Nakigozi G, et al. Effect of HIV Subtype and Antiretroviral Therapy on HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorder Stage in Rakai, Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019;81(2):216–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]