ABSTRACT

Purpose

Humeral retroversion alters range of motion and has been linked to injury risk. Clinically,palpation of the bicipital groove is used to quantify humeral torsion, but the accuracy of this procedure has not been fully examined. The purpose of this study was to investigate the relationship between clinical and diagnostic ultrasound (US) assessment of humeral torsion while considering shoulder position of the participant and clinical expertise of the examiner.

Methods

Seventeen participants (34 shoulders, 16/17 right handed, 10/17 history of throwing) were recruited. US was assessed by an experienced assessor. Two clinical assessments of humeral torsion were performed by two assessors of different experience (expert and novice). Humeral torsion was assessed at 90 degrees shoulder abduction (Palp90) and 45 degrees shoulder abduction (Palp45). Within assessor intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC (3, 1) were calculated. Correlation coefficients (Pearson’s) were generated to determine relationship between clinical and US examination findings.

Results

Intra-rater reliability for clinical tests were good (ICCs .73 - .92) for both raters. Of the palpation tests, only the expert assessor was significantly correlated to the US measurement (p<.001) at Palp45 (r = .64) and Palp90 (r = .62). For the expert, there was a significantly lower angle calculated for Palp45 compared to Palp90 (p<.001).

Conclusion

The accuracy of both palpation methods for assessing humeral retrotorsion may depend on the training background of the assessor. Further, the glenohumeral position of the patient during palpation should be consistent for the purposes of repeated testing.

KEYWORDS: Ultrasound, overhead athlete, palpation, manual therapy, shoulder

I. Introduction

Humeral version, also called humeral torsion, is defined as the bony twist about the long axis of the humerus [1,2]. Humeral retroversion (HRT), or increased posterior rotation, has been found in overhead athletes ranging from adolescents to adults. This bony adaptation allows for greater glenohumeral external rotation, but decreases glenohumeral internal rotation and horizontal adduction. While these changes in glenohumeral range of motion can be advantageous to overhead athletes, they can also lead to increased risk of injury [3–15].

Multiple methods have been established to assess HRT in individuals. The current Gold Standard has been defined as computer tomography (CT) [13,16–18]. However, CT is very costly and difficult to administer. A less costly alternative are radiographs, but radiographs are not as accurate as CT and still expose individuals to radiation [19–21]. A clinically accessible method that reduces radiation exposure and is reliable and valid when compared to CT is ultrasound (US) [3,6,16,22]. However, there is still a financial cost that limits widespread availability of US usage. Therefore, development of valid and reliable clinical measures is needed to allow a cost-effective and easy way to assess HRT.

Palpation of the bicipital groove is a common examination procedure that is used to establish a quantifiable value for HRT, by use of the bicipital forearm angle (BFA) [23]. The BFA is a measurement of the alignment of the forearm to vertical when the bicipital groove is thought to be vertically oriented and is a clinical surrogate for HRT. There is conflicting support for the validity of using palpation as a standalone assessment for HRT. Dashottar and Borstad demonstrated high correlation (r = 0.85) between US assessment and a palpation-based test for HRT with the arm at the participant’s side [24]. However, Feuerherd et al. [25] described two separate palpation tests, one with the participant’s shoulder in 90° abduction and one with the shoulder in 45° abduction. Neither test resulted in high correlation to US assessment (r ≤ 0.33). Overall, the validity of the palpation-based tests may be related to arm position, as Dashottar and Borstad [24] hypothesized that when the shoulder is abducted to 90° the bicipital tuberosities may be underneath the deltoid.

The above studies demonstrate a continued need for understanding the reliability and validity of the palpation-based examination. The inter-rater reliability with musculoskeletal palpation varies widely (0.29–0.86), there is evidence that clinician’s experience can influence reliability [25,26]. The previous HRT literature examined the reliability and validity of a single expert clinician [24,25]. This may limit the generalizability of these results to clinicians with less experience. Additionally, using the same assessor to perform both palpation and US-based assessments introduces a risk of bias that also limits generalizability [24].

It is unknown how clinical expertise and shoulder positions affect the accuracy of the clinical palpation method for assessing HRT when compared to imaging. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to investigate the relationship between measurements of HRT using clinical palpation techniques and diagnostic ultrasound imaging, with consideration of shoulder position and clinical expertise. We hypothesize that the expert clinician will exhibit a stronger correlation with US compared to the novice clinician in both shoulder positions of testing.

II. Methods

Design

This was an observational study testing for consistency of clinical palpation methods of HRT.

Participant recruitment and eligibility

Participants were recruited from a university setting. They were included in the study if they were a healthy adult between 18 and 55 years old. Additionally, participants had to demonstrate sufficient fluency in spoken or written English to communicate with the research team and complete informed consent as approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board. Participants were excluded if they had any active shoulder pain or pathology that would limit ability to tolerate the testing positions, had a history of upper extremity fracture or bone surgery, underwent medical treatment for their shoulder in the past year, or were unable to tolerate the supine position needed for testing.

Experience of assessors

The ultrasound imaging assessor was a physical therapist with 16 years of experience in orthopedics and 8 year experience with ultrasound imaging. The clinical expert assessor was a physical therapist with 9 years of experience in orthopedics and sports medicine physical therapy, a board certification in orthopedic physical therapy, extensive manual therapy training for the upper extremity, 8 years of experience treating in an overhead athlete clinic, and 5 years teaching overhead athlete continuing education coursework including clinical retroversion testing. The novice assessor was a physical therapist with 5 years of experience in an outpatient physical therapy clinic with emphasis on lower extremity pathologies and experience teaching lower extremity-specific content.

Clinical assessments

Seventeen participants (34 shoulders, 9 females: 8 males) presented to a laboratory and provided written informed consent. Next, participants were assessed for limb dominance, activity and injury history. Participants then had their height and weight measured via stadiometer and digital scale, respectively. After anthropometric measures were taken, participants then underwent assessment from the US assessor using diagnostic ultrasound followed by clinical examination by the expert assessor and finally by the novice assessor.

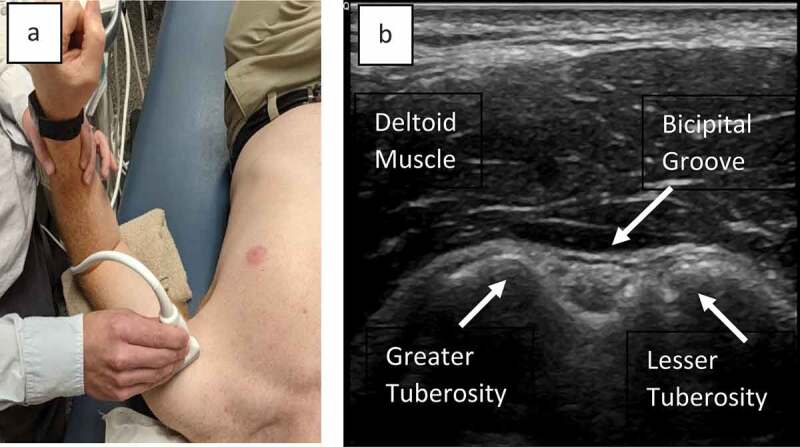

The first measurement was HRT. A BE LOGIQ S8 was used as previously described [25] but we positioned the shoulder at 45° abduction rather than 90°. This was decided based on preliminary collections with our expert US assessor having better visualization of the landmarks at 45° abduction. In B-mode, the assessor positioned the US transducer perpendicular to the proximal humerus in line with the biceps tendon, short axis view. The transducer was than translated superiorly and inferiorly until the deepest aspect of the bicipital groove was located. Image optimization was used to acquire consistency in the tilting placement of the ultrasound transducer. Once clearest view of the acoustic bony landmarks of the greater and lesser tuberosities were obtained the transducer was held in the same position while the shoulder was rotated [27]. The participant’s arm was rotated until both the greater and lesser tuberosity demonstrated a strong hyperechoic signal and were level based on a transparent, level gridline placed over the ultrasound screen (Figure 1). An assistant then measured the angle of inclination of the forearm using a bubble goniometer along the ulnar aspect of the forearm. Each procedure was performed three times.

Figure 1.

A. Arm and transducer placement for ultrasound assessment. B – Image of landmarks for ultrasound assessment

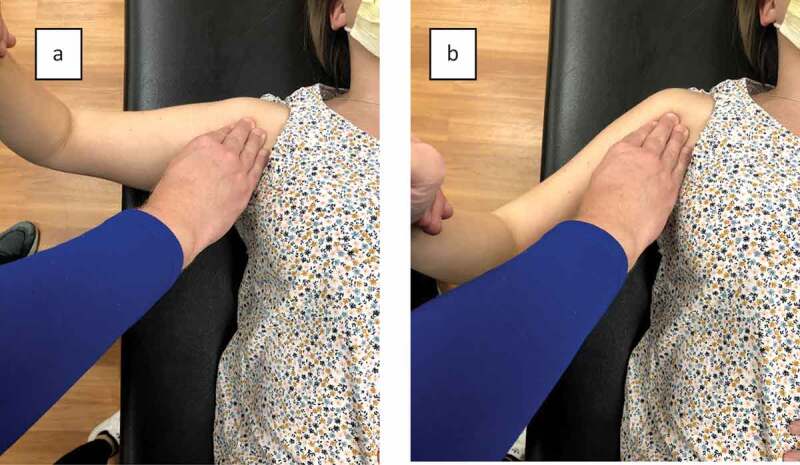

The clinical assessment of HRT was performed as previously described [25] using palpation and two different shoulder positions (Figure 2). For all clinical assessments of HRT, the participant lay supine on a table. For the first method (Palp90), the participants shoulder was abducted to 90° The assessor then palpated for the greater and lesser tuberosities of the humerus while externally rotating the participant’s shoulder. Once it was established that the greater and lesser tuberosity were vertically oriented an assistant measured the angle of inclination of the forearm. The assistant aligned a bubble goniometer oriented to vertical with the participant’s forearm and recorded the angle, with Internal Rotation denoted by a negative value and external rotation denoted by a positive value. A second assessment (Palp45) was performed in the same manner, except the participant’s shoulder was be abducted to 45° prior to the palpation and rotation.

Figure 2.

A. Palpation based assessment with shoulder at 90° abduction. B – Palpation based assessment with shoulder at 45° abduction

Participants had their external and internal rotation range of motion assessed. All clinical tests were performed after US assessment. The first measurement of each variable was assessed followed by at least 1-min rest time before the next two bouts of measurements to minimize soft tissue changes and assessor memory of measurement position.

Blinding

All assessors were blinded to all participant history including injury history, activity history and arm dominance. The assessors were also blinded to their own measurements with use of an assistant to measure and record the measurements for each assessor. Additionally, partitions were used to blind assessors from other assessor’s measurements.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 24.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Means and standard deviations were calculated on participant age and body mass index. Nominal data were reported on variables such as sex, arm dominance, and previous overhead sport participation. Within assessor, same session, intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC [1,3]) with 95% confidence intervals were conducted comparing the 3 separate measurements (US, Palp45, and Palp90) using a two-way mixed model single measure for absolute agreement. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests for normality were run prior to the main analysis and indicated that all data were normally distributed. For each clinical palpation-based test for HRT from each assessor, a correlation coefficient (Pearson’s) was run on the average of three measurements to determine the relationship between the clinical examination findings and the range of motion findings of the diagnostic ultrasound. The level of significance was set a priori to α < 0.05.

III. Results

Seventeen participants (34 shoulders) were included in our study (16 right handed: 1 left handed, 9 female: 8 male). The study population had an average body mass index of 25.88 kg/m2 with ten out of the seventeen participants reporting previous participation in overhead sports. (Table 1). Three of the participants reported a history of upper extremity musculoskeletal pathologies (ulnar collateral ligament sprain, labral tear, and clavicular fracture), none of which would alter bony alignment as assessed during the clinical humeral torsion assessment.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of participants

| Subjects | N = 17 (34 shoulders) |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | 23.88 ± 2.12 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.88 ± 4.88 |

| Overhead Sports (Yes:No) | 10:7 |

| Gender (Female:Male) | 9:8 |

| Arm Dominance (Right:Left) | 16:1 |

Y = year, kg = kilogram, m = meter.

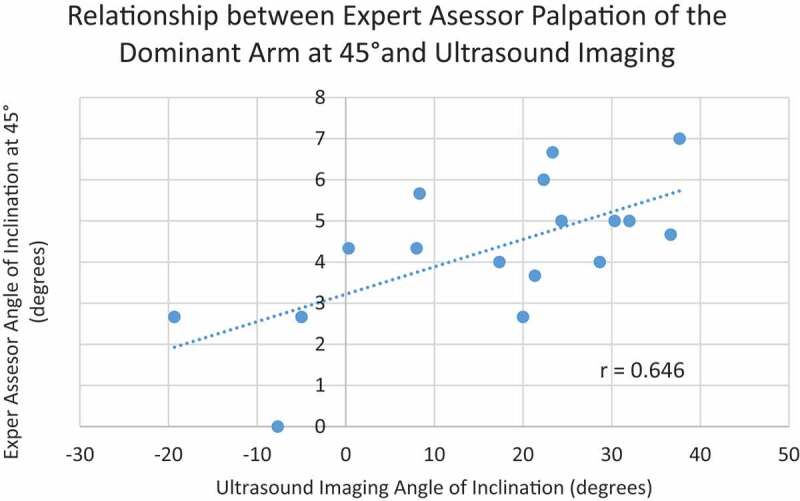

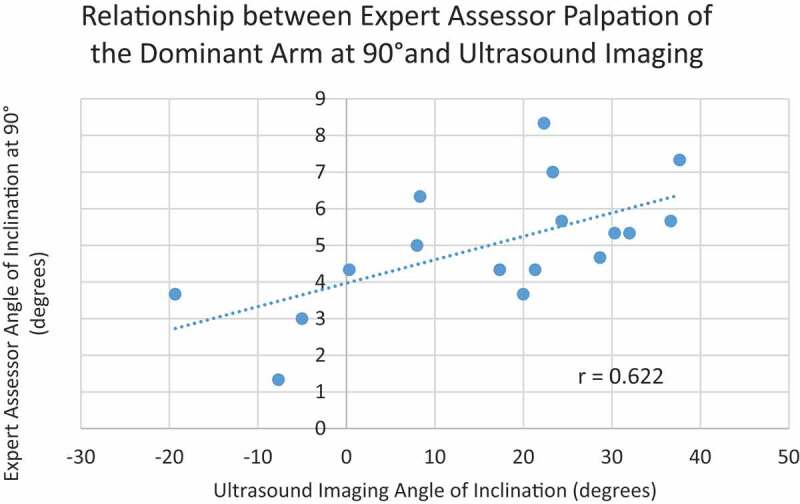

Intra-rater reliability for clinical tests were good for both the expert and novice assessor (ICC > 0.725) [28] (Table 2) [28]. The Palp45 and Palp90 values of the dominant arm obtained by the expert assessor were the only values that demonstrated correlation to the US measurements (r > 0.60). (Figures 3 and 4 and Table 3). For the expert, there was significantly lower angles calculated for Palp45 compared to Palp90 (p < 0.001), but the two were also highly correlated (r = 0.91).

Table 2.

Within day intra-rater reliability of forearm to vertical measurement in expert and novice assessor (degrees)

| Position/Limb | Measure 1 (sd) | Measure 2 (sd) | Measure 3 (sd) | ICC(95% CI) | SEM | MDC95 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expert Assessor | ||||||

| 45 abduction/dominant | 4.65 (1.97) | 4.00 (1.66) | 4.29 (2.29) | *.819(.592 – .929) | 0.97 | 2.70 |

| 45 abduction/non-dominant | 1.71 (2.57) | .18 (3.41) | 1.35 (3.02) | *.891 (.756 – .957) | 1.00 | 2.76 |

| 90 abduction/dominant | 4.82 (2.07) | 4.82 (1.70) | 5.41 (2.00) | *. 850 (.662 – .941) | 0.80 | 2.22 |

| 90 abduction/non-dominant | 2.53 (3.12) | 1.00 (3.54) | 1.18 (3.36) | *0.924(.828 – .970) | 0.93 | 2.57 |

| Novice Assessor | ||||||

| 45 abduction/dominant | −1.53 (11.28) | −3.41(13.40) | −4.65 (8.59) | *0.725 (.382 – .892) | 7.03 | 19.48 |

| 45 abduction/non-dominant | −8.12 (12.20) | −6.82 (13.53) | −5.53(13.05) | *.850 (.663 − .941) | 5.24 | 14.52 |

| 90 abduction/dominant | −1.2 (7.94) | −2.88(8.36) | 2.00 (11.08) | *.724 (.381 – .892) | 5.82 | 16.13 |

| 90 abduction/non-dominant | −3.24 (9.40) | −4.18 (12.53) | −3.65(8.07) | *.733(.400 – .895) | 6.47 | 17.95 |

*F test was considered significant at p < .05, ICC = Intraclass Correlation Coefficient, SD = standard deviation, SEM = standard error of the measure, MDC = minimal detectable change,

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

Table 3.

Relationship of clinically assessed motion with ultrasound assessed motion

| Position/Limb | Ultrasound Average (°) (sd) | Clinical Average (°) (sd) (Expert/Novice) | r (Expert/Novice) | p-value (Expert/Novice) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 45° abduction/dominant | 16.39 (16.48) | 4.31 (1.70) -3.20 (9.04) |

0.646 0.109 |

*0.005 0.676 |

| 45° abduction/non-dominant | −.765 (13.66) | 1.08 (2.74) -6.82 (11.35) |

0.266 –0.119 |

0.302 0.648 |

| 90° abduction/dominant | N/A | 5.02 (1.69) -.333(7.41) |

0.622 0.205 |

*0.008 0.431 |

| 90° abduction/non-dominant | N/A | 1.57 (3.11) -3.69 (8.21) |

0.349 –0.280 |

0.169 0.278 |

*indicates significance p < .05, r = Pearson’s Product Correlation Coefficient

IV. Discussion

This study had two purposes: 1) to examine the relationship between HRT measured using palpation-based techniques and with US-guided assessment, 2) to examine the impact clinician experience may have on reliability or validity of two palpation-based tests. The results support our hypothesis that there was a strong correlation between Palp45 and Palp90 from the expert assessor and the US guided technique. Additionally, while the novice assessor had moderate intra-rater reliability, values were lower than the expert assessor and there was no correlation between novice assessor measurement and US guided measurement.

These results contribute to the conflicting data regarding the validity of palpation-based assessments of HRT compared to US guided assessments. While one study found a strong correlation (r = 0.85) between US assessment and palpation-based testing [24], another reported fair correlation (r = 0.326) at best [25]. The differences in results may be partially explained by methodological differences between the studies. Dashotter and Borstad [24] found the highest correlation between US and palpation, but had the same expert assessor perform both the US and palpation assessments. It is very likely that the same examiner performing both palpation-based and US guided assessment would introduce bias that could lead to a higher correlation coefficient. Meanwhile, Feuerherd et al. [25] specifically recruited overhead athletes, which likely biased the sample to higher presence of HRT. Lastly, the current study utilized a shoulder abduction angle of 45° for US assessment while the previous studies used a variety of approaches: an arm at side [24] approach with good reliability, an arm at 90° abduction [25] approach with fair reliability, and an arm at 45° abduction [25] approach with poor reliability. These varying degrees of shoulder abduction likely change the relationship of the soft tissue around the bicipital groove that may affect visibility. Combining the results of the previous literature with the current study it appears that experienced clinicians can better infer presence of HRT during clinical examination compared to novice clinicians.

With the expert clinician performing more reliably and with stronger correlation to US guided assessment, our results support previous research demonstrating that experience with palpation techniques improves reliability. When asked to identify myofascial trigger points of the elbow, two experienced clinicians had moderate percent agreement (58–86% agreement), while an inexperienced assessor had poor to moderate percent agreement (39–60%) [29]. When performing Craig’s test, which is a similar procedure to the one performed in the current study used to assess hip bony alignment, novice clinicians had poor inter-rater reliability [26]. Additionally, the shoulder medial rotation test demonstrated much higher levels of agreement between experienced assessors (k = 0.33) compared to novice assessors (k = 0.06) [30]. Taken all together, novice clinicians perform more variably during palpation-based tests. It is possible that if both assessors from the current study had similar levels of experience in performing the palpation-based clinical examinations there would have been higher correlation with the US guided measurement from the novice.

While the values at Palp45 and Palp90 differed for the expert clinician these values were highly correlated (r = 0.91). Therefore, it is recommended that expert clinicians perform the palpation exam at the same angle of abduction to allow comparison of values obtained. Additionally, since the exact values obtained at each abduction position may be difficult to compare to each other, using the test as a side-to-side comparison merits consideration.

The expert clinician had differing reliability values when compared to the US for the dominant and non-dominant limb. The examiner would have used their right hand (dominant hand) when palpating the right bicipital groove when testing the right arm HRT, but would have used their left hand when testing the left HRT. This could explain the differences seen in reliability values seen between the dominant and non-dominant shoulders as 16/17 individuals were right hand dominant. Therefore, it is the authors recommendation that clinicians practice bilaterally to improve the accuracy of the test on both sides.

This study is not without limitations. As the order of assessors or assessments were not randomized, there is a possibility that there were alterations in the status of the participants. To minimize soft tissue adaptations, time was taken between each measurement. Additionally, with increased training there may have been an improvement in the results from the novice assessor. As with previous research that compares palpation to US assessment, there may be a different relationship seen if CT scan was utilized to assess HRT. However, as it has been established in the literature, CT scan and US measures have yielded high correlation and US has been identified as a surrogate measure [16,25]. While the palpation-based measurement of the expert examiner had high correlation to the US assessment, the mean values did not agree. This likely speaks to the variability of assessor hand placement. While an individual assessor might have consistent hand placement for palpation for each repetition, this placement might not completely align with vertical orientation, hence giving different values. Methodologically, we did not have an inclinometer to ensure the transducer was level, but our trained US examiner utilized established methods for visualizing bony landmarks. The choice of using 45° abduction for the assessment using US was made despite some previous literature assessing 90° abduction [16,23] based on the ability to visualize the bony landmarks. Results of this study may have limited generalizability to an overhead athlete population given that this pilot study had limited participants with overhead sport backgrounds whereas previous studies have included exclusively overhead athletes. Lastly, the same session intra-rater reliability of our measures were derived from a single measure (ICC form 1) while the relationships between the clinical measures and ultrasound were calculated using the average of three trials. The researchers chose this approach as it is was not feasible to obtain data collection on a second day. In order to mitigate concerns related to measuring within day reliability, all assessors were blinded to the their own assessments as well as other assessor assessments.

The palpation-based assessments for HRT are potentially viable options for clinical use. Based on the results of the current study, clinician experience needs to be considered when applying the results. Clinicians with experience with the palpation-based assessments are more likely to repeat valid measurements, while those with limited experience should ensure practice prior to clinical application. Additionally, the expert palpation-based assessment demonstrated higher correlation to the US-based assessment, but the specific measurements were different. Thus, palpation-based assessments should not be considered direct replacements for US-based assessments.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- [1].Whiteley RJ, Ginn KA, Nicholson LL, et al. Sports participation and humeral torsion. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009;39(4):256–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Debevoise NT, Hyatt GW, Townsend GB.. Humeral torsion in recurrent shoulder dislocations. A technic of determination by X-ray. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1971;76:87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Thomas SJ, Sheridan S, Reuther KE, et al. Participation age in professional baseball pitchers by geographic region. J Athl Train. 2020;55(1):27–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Helmkamp JK, Bullock GS, Rao A, et al. The relationship between humeral torsion and arm injury in baseball players: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Health. 2020;12(2):132–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ito A, Mihata T, Hosokawa Y, et al. Injury risk after proximal humeral epiphysiolysis (Little Leaguer’s Shoulder). Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(13):3100–3106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Takenaga T, Goto H, Tsuchiya A, et al. Relationship between bilateral humeral retroversion angle and starting baseball age in skeletally mature baseball players-existence of watershed age. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2019;28(5):847–853. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Takeuchi S, Yoshida M, Sugimoto K, et al. The differences of humeral torsion angle and the glenohumeral rotation angles between young right-handed and left-handed pitchers. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2019;28(4):678–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Nakase C, Mihata T, Itami Y, et al. Relationship between humeral retroversion and length of baseball career before the age of 16 years. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(9):2220–2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Astolfi MM, Struminger AH, Royer TD, et al. Adaptations of the shoulder to overhead throwing in youth athletes. J Athl Train. 2015;50(7):726–732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hibberd EE, Oyama S, Myers JB. Increase in humeral retrotorsion accounts for age-related increase in glenohumeral internal rotation deficit in youth and adolescent baseball players. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(4):851–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Shanley E, Thigpen CA, Clark JC, et al. Changes in passive range of motion and development of glenohumeral internal rotation deficit (GIRD) in the professional pitching shoulder between spring training in two consecutive years. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(11):1605–1612. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Thomas SJ, Swanik CB, Kaminski TW, et al. Humeral retroversion and its association with posterior capsule thickness in collegiate baseball players. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(7):910–916. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Polster JM, Bullen J, Obuchowski NA, et al. Relationship between humeral torsion and injury in professional baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(9):2015–2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Myers JB, Oyama S, Rucinski TJ, et al. Humeral retrotorsion in collegiate baseball pitchers with throwing-related upper extremity injury history. Sports Health. 2011;3(4):383–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Noonan TJ, Shanley E, Bailey LB, et al. Professional pitchers with Glenohumeral Internal Rotation Deficit (GIRD) Display Greater Humeral Retrotorsion Than Pitchers Without GIRD. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(6):1448–1454. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Myers JB, Oyama S, Clarke JP. Ultrasonographic assessment of humeral retrotorsion in baseball players: a validation study. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(5):1155–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Crockett HC, Gross LB, Wilk KE, et al. Osseous adaptation and range of motion at the glenohumeral joint in professional baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(1):20–26. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Chant CB, Litchfield R, Griffin S, et al. Humeral head retroversion in competitive baseball players and its relationship to glenohumeral rotation range of motion. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2007;37(9):514–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Osbahr DC, Cannon DL, Speer KP. Retroversion of the humerus in the throwing shoulder of college baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(3):347–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Reagan KM, Meister K, Horodyski MB, et al. Humeral retroversion and its relationship to glenohumeral rotation in the shoulder of college baseball players. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(3):354–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Tokish JM, Curtin MS, Kim YK, et al. Glenohumeral internal rotation deficit in the asymptomatic professional pitcher and its relationship to humeral retroversion. J Sports Sci Med. 2008;7(1):78–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Whiteley R, Ginn K, Nicholson L, et al. Indirect ultrasound measurement of humeral torsion in adolescent baseball players and non-athletic adults: reliability and significance. J Sci Med Sport. 2006;9(4):310–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kurokawa D, Yamamoto N, Ishikawa H, et al. Differences in humeral retroversion in dominant and nondominant sides of young baseball players. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26(6):1083–1087. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Dashottar A, Borstad JD. Validity of measuring humeral torsion using palpation of bicipital tuberosities. Physiother Theory Pract. 2013;29(1):67–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Feuerherd R, Sutherlin MA, Hart JM, et al. Reliability of and the relationship between ultrasound measurement and three clinical assessments of humeral torsion. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2014;9(7):938–947. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Choi BR, Kang SY. Intra- and inter-examiner reliability of goniometer and inclinometer use in Craig’s test. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015;27(4):1141–1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Zander D, Hüske S, Hoffmann B, et al. Ultrasound Image Optimization (“Knobology”): b-Mode. Ultrasound Int Open. 2020;6(1):E14–e24. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Portney LGWM, editor. Foundations of Clinical Research: applications to Practice. 3rd ed ed. Upper Saddle River NJ: F.A. Davis Company; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Mora-Relucio R, Núñez-Nagy S, Gallego-Izquierdo T, et al. Experienced versus inexperienced interexaminer reliability on location and classification of myofascial trigger point palpation to diagnose lateral epicondylalgia: an observational cross-sectional study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:6059719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Lluch E, Benítez J, Dueñas L, et al. The shoulder medial rotation test: an intertester and intratester reliability study in overhead athletes with chronic shoulder pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2014;37(3):198–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]