Abstract

Hic-5 is a paxillin homologue that is localized to focal adhesion complexes. Hic-5 and paxillin share structural homology and interacting factors such as focal adhesion kinase (FAK), Pyk2/CAKβ/RAFTK, and PTP-PEST. Here, we showed that Hic-5 inhibits integrin-mediated cell spreading on fibronectin in a competitive manner with paxillin in NIH 3T3 cells. The overexpression of Hic-5 sequestered FAK from paxillin, reduced tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin and FAK, and prevented paxillin-Crk complex formation. In addition, Hic-5-mediated inhibition of spreading was not observed in mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) derived from FAK−/− mice. The activity of c-Src following fibronectin stimulation was decreased by about 30% in Hic-5-expressing cells, and the effect of Hic-5 was restored by the overexpression of FAK and the constitutively active forms of Rho-family GTPases, Rac1 V12 and Cdc42 V12, but not RhoA V14. These observations suggested that Hic-5 inhibits cell spreading through competition with paxillin for FAK and subsequent prevention of downstream signal transduction. Moreover, expression of antisense Hic-5 increased spreading in primary MEFs. These results suggested that the counterbalance of paxillin and Hic-5 expression may be a novel mechanism regulating integrin-mediated signal transduction.

Integrin-mediated cell adhesion to the extracellular matrix (ECM) is crucial for multiple biological functions, including cell growth, differentiation, survival, cytoskeleton reorganization, migration, tumor metastasis, and embryonic development (10, 23, 26, 30, 46, 59, 68, 71). Integrins are heterodimeric transmembrane receptors composed of α- and β-subunits whose specificity for different ECMs are determined by their combination (26). Cell attachment to the ECM induces integrin clustering and recruitment of a number of intracellular proteins, such as focal adhesion kinase (FAK), paxillin, vinculin, talin, and p130 Cas (8, 60, 65, 68) to specialized sites of the inner cytoplasmic membrane to form focal adhesion complexes. These complexes link the actin cytoskeleton and regulate intracellular signaling pathways, thereby coordinating cell attachment with cell architecture, movement, and gene expression (68). Although the molecular mechanism of integrin-mediated signal transduction has not been well defined, tyrosine phosphorylation of several cytoplasmic proteins, including FAK, paxillin, tensin, and Cas seems to be a critical biochemical aspect of this process (5, 9, 19 54, 60, 81). On integrin-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation, these proteins bind to signaling molecules such as Crk, Grb2, Nck, and Src that contain the Src homology 2 (SH2) domain (21, 68).

Paxillin is one of the focal adhesion proteins (17, 81, 82) that was originally identified as a major tyrosine phosphorylated protein in cells transformed by v-Src and v-Crk (4, 17). Paxillin associates with signaling molecules and cytoskeletal proteins, such as FAK, Pyk2/Cakβ/RAFTK, c-Src, PTP-PEST, talin, and vinculin, and has been suggested to be involved in the regulation of focal adhesion dynamics (6, 11, 61). In particular, the association of FAK with paxillin is essential for focal adhesion targeting of FAK (74). In addition, paxillin is tyrosine phosphorylated following integrin stimulation by FAK and/or other kinases that are associated with FAK (66, 82). This phosphorylation creates docking sites for the SH2 domain of Crk (3) and links integrin stimulation to downstream signaling pathways through guanine nucleotide exchange proteins such as C3G (77), SOS (44), and DOCK180 (22). Thus, paxillin is involved in integrin-mediated signal transduction as a scaffold of these signaling molecules. In addition, a recent study demonstrated that the tyrosine residues at positions 31 and 118 on paxillin regulate cell migration through association with Crk in NBT-II cells (53). Paxillin also binds to the recently identified paxillin-kinase linker, p95PKL, that links paxillin to p21 GTPase-activated kinase, PAK, and the guanine nucleotide exchange protein, PIX, through the LD domain that is defined as a leucine-rich motif for association with interacting proteins (84). The formation of the paxillin-p95PKL-PAK-PIX complex has been suggested to play an important role in cytoskeletal organization (84).

Hic-5, a paxillin homologue, was originally identified as a transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1)- and hydrogen peroxide-inducible gene by differential hybridization (69). Its expression is increased during cellular senescence of normal human fibroblasts and is decreased during immortalization of mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) (28, 69). The forced expression of Hic-5 in immortalized fibroblasts induced growth retardation, senescence cell-like morphology (i.e., cells became enlarged, flattened, and well spread), and the increased gene expression of p21/WAF1/Cip1/sdi1 and ECM-related proteins such as collagen, fibronectin, and collagenase (70). These observations suggested that Hic-5 is involved in the negative regulation of cell growth, including the senescence process and TGFβ signal transduction. However, the molecular mechanisms of the function of Hic-5 have not been clarified. Recent studies have shown that Hic-5 is a cytoskeletal protein localized to focal adhesions in fibroblasts (15, 28, 45). In addition, Hic-5 contains four LD motifs in the N-terminal half and four LIM domains in the C-terminal half (6, 70). These regions are well conserved in paxillin (6, 70). Several proteins have been identified as Hic-5 interacting factors, including FAK (6, 15), Pyk2 (45), PTP-PEST (50), vinculin (6), and p95PKL (84). These are shared with paxillin and are considered to play important roles in integrin-mediated signal transduction and remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton. Despite their similarity, Hic-5 has some features distinct from paxillin. Unlike paxillin, Hic-5 is not phosphorylated by integrin stimulation (15) and does not have a target site for the Crk SH2 domain (80). Furthermore, the Hic-5 expression level was specifically decreased during immortalization, whereas that of paxillin tended to increase (28). Taken together, we hypothesized that Hic-5 could compete for common interaction factors with paxillin and antagonize the signaling pathways that involve paxillin.

Most adherent cells respond to ECM by adhering and then spreading out to acquire a flattened morphology. This process is mediated by integrins and involves dynamic rearrangements of the actin cytoskeleton, which are regulated by intracellular signaling pathways (58, 85). The cell spreading assay provides a convenient model for examining the formation of focal adhesions and cell migration (57). In the present study, we adopted this assay system to assess the possibility that Hic-5 competed with paxillin for integrin-mediated signal transduction. The results presented below indicated that the altered balance between paxillin and Hic-5 expression affected cell spreading and that Hic-5 overexpression inhibited cell spreading.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies.

Anti-mouse Hic-5 polyclonal antibody was raised against recombinant Hic-5 as described previously (28). Anti-FAK rabbit polyclonal antibody C-20 was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, Calif.). Anti-paxillin and antiphosphotyrosine (PY20) mouse monoclonal antibodies were from Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, Ky.). Anti-p130Cas polyclonal antibody was a generous gift from Tatsuya Nakamoto, University of Tokyo. Anti-hemagglutinin (HA) (12CA5) and anti-Myc (9E10) monoclonal antibodies were purchased from Boehringer Mannheim Co. (Indianapolis, Ind.) and Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, N.Y.), respectively. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) and anti-mouse IgG antibodies were from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom). Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody was from Dako (Copenhagen, Denmark).

Cell culture and transfection.

NIH 3T3 cells were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated calf serum and 50 μg of kanamycin per ml at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air. Mortal and immortal MEFs were established as described previously (28) and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 50 μg of kanamycin per ml in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air. FAK-null cells derived from FAK knockout mice were a generous gift from Tadashi Yamamoto, Institute of Medical Science, University of Tokyo. Cells were transfected with plasmid DNAs using Lipofectamine Plus reagent (Life Technologies, Inc., Rockville, Md.) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Plasmids.

For construction of the HA-tagged mouse Hic-5 expression vector (pCG-mhic-5), the NspI-ApaI fragment from the CMV/S5 described elsewhere (69) was blunted and ligated with BamHI linkers for in-frame insertion into the expression vector driven by the cytomegalovirus promoter pCG-N-BL (25). After BamHI digestion, the linker-linked cDNA fragment was inserted into the BamHI site of the pCG-N-BL vector. For HA-tagged human Hic-5, an EcoRI-HindIII fragment cut out from Myc-tagged human Hic-5/pcDNA3.1A (described below) was blunted at the EcoRI site and inserted into the expression vector pCG-N-BL digested with EcoRV and HindIII.

All other Hic-5 expression vectors were constructed by PCR-based methods. HA-tagged expression vectors were constructed by introducing inserts into pCG-N-BL. Myc-tagged constructs were based on pcDNA3.1(−)/Myc-HisA vector (Invitrogen, San Diego, Calif.). For the HA-tagged paxillin expression vector (pCG-pax), the insert was amplified by PCR using primers incorporating 5′ XbaI and 3′ HindIII restriction sites and human α-form paxillin cDNA provided by Hisataka Sabe, Osaka Bioscience Institute, as a template (48). For the HA-tagged LD1 mouse Hic-5 expression vector (pCG-LD1mhic-5), the cDNA was generated by PCR using a 5′ primer containing the nucleotide sequence corresponding to the LD1 domain of mouse Hic-5 (80). For Myc-tagged human Hic-5 expression vector (pcDNA3.1A-hhic-5), the cDNA was generated by reverse transcriptase-PCR using mRNA prepared from normal human diploid fibroblasts. Forward and reverse primers were derived from the sequences reported by Matsuya et al. (45) and those determined previously by the 5′-Full RACE (rapid amplification of cDNA ends) method (28). For Myc-tagged N-terminal deletion mutants of human Hic-5 (pcDNA3.1A-Δ1-2hhic-5 lacked amino acids 1 to 145, and pcDNA3.1A-hic/LIM lacked amino acids 1 to 219), the selected regions of pcDNA3.1A-hhic-5 plasmid were amplified by PCR using 5′ primers containing an EcoRI site and an endogenous Kozak consensus sequence (39) and a 3′ primer incorporating a BamHI site. To construct expression vectors for HA-tagged deletion mutants of hHic-5 (pCG-ΔLD3-4hhic-5 lacked amino acids 148 to 222, and pCG-ΔLD3hhic-5 lacked amino acids 148 to 170), N-terminal fragments and C-terminal fragments were amplified by independent PCR. The N-terminal fragment, which corresponded to amino acid residues 1 to 148, was amplified using a 5′ primer incorporating a BamHI site and a 3′ primer incorporating an EcoRI site. The C-terminal fragments, which corresponded to amino acid residues 223 to 461 or 171 to 461, were amplified by using 5′ primers incorporating EcoRI sites and a 3′ primer incorporating a HindIII site. The N-terminal fragment and each of the C-terminal fragments were digested with EcoRI, ligated, and digested with BamHI and HindIII for incorporation into pCG-N-BL. The identities of the inserts were confirmed by sequencing. The antisense expression vector of Hic-5 was described previously (70).

Retrovirus expression vectors, pCHC/EGFP and pCdEB/Myc-Hic-5, were constructed by inserting enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) or Myc-tagged mouse Hic-5 cDNA into pCdEB lacking the neo gene of pCLNCX (Imgenex, San Diego, Calif.). Myc-tagged wild-type FAK and kinase-defective FAK (K454R) were constructed by inserting these cDNAs into pSRα. pEF-BOS-HA-RhoA V14, pEF-BOS-HA-Rac1 V12, and pEF-BOS-HA-Cdc42 V12 constructs were generously provided by Kohzoh Kaibuchi, Nara Institute of Science and Technology. pSRA2, a v-Src construct, was obtained from Japan Human Sciences Foundation.

Cell spreading.

At 48 h after transfection, NIH 3T3 cells were collected by trypsinization and washing with serum-free DMEM containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Cells resuspended in serum-free DMEM containing 1% BSA were replated on coverslips coated with 5 μg of fibronectin (Upstate Biotechnology) per cm2 and placed on ice for 5 min. Subsequently, the cells were allowed to spread for 30 min at 37°C. Cells attached to coverslips were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 10 min and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 3 min. Cells were blocked with 3% BSA in PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20, treated with anti-HA antibody (12CA5) at 1:300 or with anti-Myc antibody (9E10) at 1:300 for 1 h, and then incubated with tetramethyl rhodamine isocyanate (TRITC)-conjugated phalloidin (Sigma) at 1:300 and with FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Dako) at 1:300 for 1 h. After being washed with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20, the cells were mounted and visualized under a low-magnification fluorescence microscope. Transfected cells were counted, and the percentage of spread cells was evaluated. Nonspread cells were defined as round phase-bright cells, whereas spread cells were defined as those that lacked a rounded shape, were not phase-bright, and had extended membrane protrusions. In each experiment, more than 150 cells were counted. At least four independent experiments were performed for each combination of experiments.

Virus infection.

Retroviral expression vectors were cotransfected with the packaging vector pCL-Eco (49) into 293 cells by the calcium phosphate method. At 48 h after transfection, the supernatants were collected, filtered through 0.45-μm (pore size) filters, and then used to infect MEFs in the presence of 80 μg of Polybrene per ml. The day before infection, MEFs were trypsinized and plated to reach 50 to 80% confluence on the day of transfection. Supernatants containing viruses were poured onto MEFs and, 1 day after infection, the media were replaced with fresh media.

Cell stimulation with fibronectin.

Cells were starved of serum in DMEM containing 0.5% FBS and 1% BSA for 16 h and harvested with PBS containing 0.05% trypsin and 2 mM EDTA. Trypsin was inactivated by adding 0.5 mg of soybean trypsin inhibitor per ml with 1% BSA in DMEM, and cells were collected by centrifugation, resuspended in DMEM containing 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) and 1% BSA, and held in suspension for 90 min at 37°C. Suspended cells were distributed onto fibronectin-coated culture dishes and incubated at 37°C for 20 min. Fibronectin-coated dishes were prepared by incubation of culture dishes with 2 μg of fibronectin per ml in serum-free DMEM for 2 h at 37°C, blocking with 0.5% BSA in PBS overnight at 37°C, and washing with PBS.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting.

Cells were washed with PBS and lysed in lysis buffer, and insoluble material was removed by centrifugation. For evaluation of phosphotyrosine levels, cells were lysed in modified radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4; 150 mM NaCl; 1.5 mM MgCl2; 1 mM EGTA; 1% Triton X-100; 1% sodium deoxycholate; 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]; 10% glycerol; 1 mM sodium orthovanadate; 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate; 1 mM NaF; protease inhibitor mixture [Wako]). For coimmunoprecipitation, cells were lysed in HTN lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4; 150 mM NaCl; 1% Triton X-100; 1 mM sodium orthovanadate; 1 mM NaF; protease inhibitor mixture [Wako]). Lysates were precleaned with normal IgG (Dako, Copenhagen, Denmark) immobilized on protein G-Sepharose (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Precleared lysates were incubated with antibodies immobilized on protein G-Sepharose at 4°C for 60 min. The beads were then washed four times in their respective washing buffers. For evaluation of phosphotyrosine levels, 1% Triton washing buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4; 150 mM NaCl; 1.5 mM MgCl2; 1 mM EGTA; 1% Triton X-100; 10% glycerol; 1 mM sodium orthovanadate; 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate; 1 mM NaF; protease inhibitor mixture [Wako]) was used. For coimmunoprecipitation, HTN washing buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4; 150 mM NaCl; 0.1% Triton X-100; 1 mM sodium orthovanadate; 1 mM NaF; protease inhibitor mixture [Wako]) was used. The immunecomplexes were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) loading dye.

For immunoblotting, proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, washed with TBS (10 mM Tris, pH 7.4; 100 mM NaCl), and blocked with blocking buffer (TBS containing 0.1% Tween and 1% BSA). Blots were incubated with 1 μg of anti-Myc (9E10) per ml, 5 μg of anti-HA antibody (12CA5) per ml, a 1:10,000 dilution of antipaxillin antibody, a 1:2,500 dilution of antiphosphotyrosine (PY20) monoclonal antibody, or a 1-μg/ml concentration of anti-FAK per ml of polyclonal antibody for 1 h at room temperature. HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) were used at 1:10,000. Bound antibodies were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Renaissance TM; New England Nuclear Life Science Products, Boston, Mass.).

In vitro kinase assay.

Cells were lysed in modified RIPA buffer. Immunoprecipitations by anti-c-Src antibody were carried out as described above. After the beads were washed in modified RIPA buffer, they were washed in kinase buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.2; 125 mM MgCl2; 25 mM MnCl2; 2 mM EGTA; 250 μM sodium orthovanadate; 2 mM dithiothreitol). Beads were split equally into two two tubes: one portion was analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-c-Src antibody (Upstate Biotechnology), and the other was used in the kinase assay. Acid-denatured rabbit muscle enolase was added to 30 μl of kinase reaction buffer as a substrate. To initiate kinase reactions, 10 μl of ATP mixture (20 mM morpholinepropanesulfonic acid, pH 7.2; 75 mM MgCl2; 500 μM cold ATP; 25 mM β-glycerol phosphate; 5 mM EGTA; 1 mM sodium orthovanadate; 1 mM dithiothreitol; 10 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP) was added to immunoprecipitates, and reaction mixtures were incubated for 5 min at 25°C. The reactions were stopped by adding 10 μl of 5× SDS-PAGE sample buffer (313 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8; 50% glycerol; 10% SDS; 0.065% bromophenol blue; 7.7% dithiothreitol) and boiled for 3 min. Reaction products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Gels were prepared for standard autoradiography and quantitated using BAS2000 (Fuji Film). Specific kinase activity was calculated by dividing the radioactivity of the enolase band by the area of the c-Src band determined by immunoblotting.

RESULTS

Hic-5 Inhibits cell spreading.

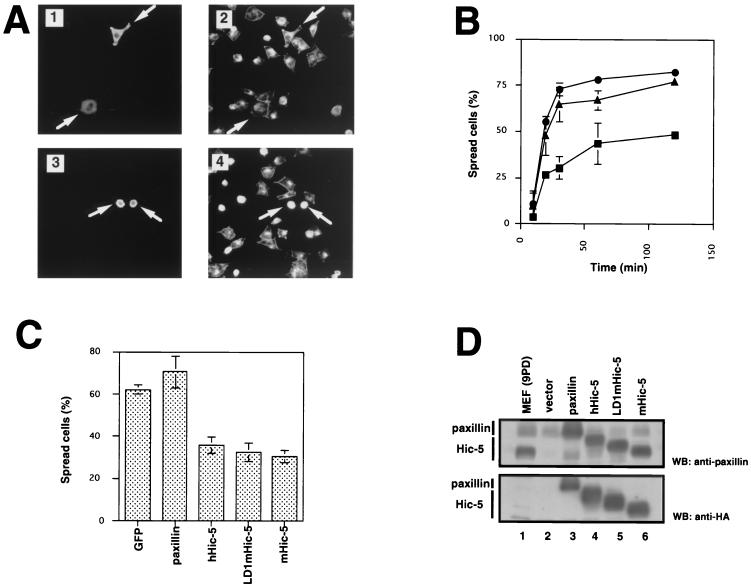

To investigate the effects of the counterbalance between paxillin and Hic-5 expression on integrin functions, we compared the cell spreading on fibronectin using NIH 3T3 cells, which were either nontransfected or transfected with HA-tagged Hic-5 (LD1mHic-5, described below) or paxillin expression vectors. Cells were collected by trypsinization, replated onto coverslips coated with fibronectin, and then fixed and stained with anti-HA antibody. Nontransfected NIH 3T3 cells and paxillin-overexpressing cells began to spread within 30 min (Fig. 1A and B). In contrast, Hic-5-overexpressing cells showed significantly less spreading at this time point (Fig. 1A and B).

FIG. 1.

Effects of Hic-5 overexpression on cell spreading. (A) NIH 3T3 cells transfected with pCG-pax (HA-tagged paxillin, panels 1 and 2) or pCG-LD1mhic-5 (HA-tagged LD1mHic-5, panels 3 and 4) were allowed to spread on fibronectin-coated coverslips for 30 min, fixed with 3.7% formalin, and then immunostained with anti-HA antibody (panels 1 and 3) or stained with TRITC-conjugated phalloidin (panels 2 and 4). Arrows indicate the transfected cells. (B) NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with vector (●), expression vector of paxillin (▴), or Hic-5 (■). After 48 h, cell spreading was quantified by allowing the cells to spread on fibronectin-coated coverslips for the indicated times. Cells were stained with anti-HA antibody, and the percentages of spread cells among transfected cells stained with anti-HA antibody at each time point were calculated. Values represent the means of at least three independent experiments ± the standard deviation (SD). (C) NIH 3T3 cells transfected with pEGFP-N3 (GFP), pCG-pax (paxillin), pCG-hhic-5 (hHic-5), pCG-LD1mhic-5 (LD1mHic-5), and pCG-mhic-5 (mHic-5) were allowed to spread on fibronectin-coated coverslips for 30 min. The percentages of the spread cells were determined. Each bar represents the mean of at least three independent experiments ± the SD. (D) Equal amounts of total cell lysates from cells used in the spreading assay were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-HA antibody. Lane 1, primary MEFs; lanes 2 to 6, NIH 3T3 cells transfected with vector (lane 2) or the expression vectors of paxillin (lane 3), hHic-5 (lane 4), LD1mHic-5 (lane 5), or mHic-5 (lane 6).

To further explore this observation, we carried out semiquantitative cell spreading assay. Transiently transfected cells were counted, and the percentage of spread cells was evaluated. Original mouse Hic-5 did not include the LD1 domain, but Thomas et al. (80) reported an alternative form of Hic-5 mRNA that contained the LD1 domain, so an LD1 domain (7) was added to the N terminus of the originally cloned mouse Hic-5 to construct LD1mHic-5. In NIH 3T3 cells, the inhibitory effect of Hic-5 was maximal at 30 min (nontransfected cells, 72.9% ± 3.6%; paxillin-overexpressing cells, 64.7% ± 9.4%; LD1mHic-5-overexpressing cells, 30.2% ± 6.1% of spread) (Fig. 1B). The majority of cells, however, spread within 3 h (data not shown), indicating that Hic-5 overexpression delayed but did not completely prevent the spreading process. In addition to LD1mHic-5, we used other Hic-5 expression vectors, such as human Hic-5 (hHic-5) (45) and mouse Hic-5 (mHic-5) (69), in the spreading assay and found that all Hic-5 constructs inhibited cell spreading to essentially the same extent (Fig. 1C). This observation that mHic-5 lacking the LD1 domain showed comparable inhibitory activity to hHic-5 and LD1mHic-5 suggested that the LD1 domain of Hic-5 is not essential for the downregulation of cell spreading. Hic-5 expression levels of cells transfected with the expression vector restored Hic-5 level to that of mortal MEFs (Fig. 1D).

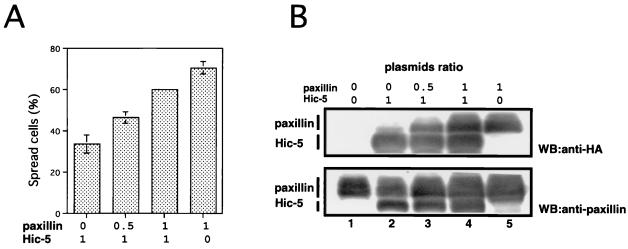

Paxillin rescues Hic-5-mediated inhibition of cell spreading.

To determine whether the inhibition of spreading was caused by the altered counterbalance between Hic-5 and paxillin expression, we cotransfected the paxillin and the Hic-5 expression vectors at various ratios. The expression of these proteins was determined by Western blotting using anti-HA and anti-paxillin antibodies (Fig. 2B). Hic-5-mediated inhibition of spreading was restored by cotransfection of the paxillin expression vector at a 1:1 ratio to the level of 85.2% of control cells (Fig. 2A), indicating that the counterbalance between Hic-5 and paxillin is important for the modulation of cell spreading and that the inhibition observed in this study was not caused by the toxic effects of the overexpression of exogenous proteins. In addition, the efficiency of this reversion was dose dependent. This implied that Hic-5 has a competitive effect on the action of paxillin. Indeed, Hic-5 and paxillin share common interacting factors, including FAK, Pyk2, vinculin, talin, and PTP-PEST. In this regard, FAK and PTP-PEST have been reported to be involved in cell spreading (1, 57). Therefore, these are possible molecular targets for this competition.

FIG. 2.

Paxillin rescued Hic-5-mediated inhibition of cell spreading. (A) NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with pCG-pax (HA-paxillin) and/or pCG-LD1mhic-5 (HA-LD1mHic-5) at the ratios indicated. The transfected cells were allowed to spread on fibronectin-coated coverslips for 30 min, and the numbers of spread cells were determined in each case as described above. Each bar represents the mean of at least three independent experiments ± the SD. (B) Equal amounts of total cell lysates (20 μg of cellular protein/lane) from cells transfected with an empty vector (lane 1), pCG-pax (HA-paxillin) and/or pCG-LD1mhic-5 (HA-LD1mHic-5) at the ratios 0:1 (lane 2), 0.5:1 (lane 3), 1:1 (lane 4), or 1:0 (lane 5), respectively, were subjected to immunoblotting with anti-HA antibody (upper panel) or antipaxillin antibody (lower panel). The gels were stained with Coomassie blue to confirm the same amounts of protein loading.

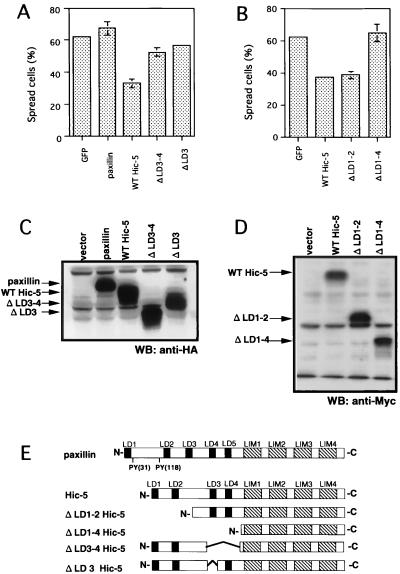

LD3 domain of Hic-5 is required for inhibition of spreading.

A chimeric mutant containing the N-terminal region of Hic-5 and the C-terminal region of paxillin had almost the same activity as did the wild-type Hic-5 (data not shown). Therefore, we focused on the N-terminal region of Hic-5. To determine which region of Hic-5 is required for inhibition of spreading, we used various Hic-5 deletion mutants in the spreading assay (Fig. 3E). Mutant constructs used in this study (Fig. 3E) were transiently transfected, and their expression in NIH 3T3 cells was assessed (Fig. 3C and D). Each construct expressed similar amounts of the protein.

FIG. 3.

The LD3 domain of Hic-5 was required for the inhibition of spreading. (A and C) NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with pEGFP-N3 (GFP), pCG-pax (paxillin), pCG-hhic-5 (WT Hic-5), pCG-ΔLD3-4hhic-5 (ΔLD3-4, HA-tagged human Hic-5 with deletion of LD3-4 domains), or pCG-ΔLD3hhic-5 (ΔLD3, HA-tagged human Hic-5 with deletion of LD3 domain). (B and D) Cells were transfected with an empty vector or pcDNA3, 1A-hhic-5 (Myc-tagged WT hHic-5), pcDNA3.1A-ΔLD1-2hhic-5 (ΔLD1-2, Myc-tagged human Hic-5 with deletion of LD1-2 domains), and pcDNA3. 1A-hic/LIM (ΔLD1-4, Myc-tagged human Hic-5 with deletion of LD1-4 domains) in lanes 1 to 4, respectively. Cells were allowed to spread on fibronectin-coated coverslips for 30 min and stained with anti-HA (A) or anti-Myc (B) antibodies, and the numbers of spread cells were determined in each case as described above. Each bar represents the mean of at least three independent experiments ± the SD. Lysates obtained from cells transfected with the different constructs were analyzed for the expression of tagged proteins with anti-HA antibody (C) or anti-Myc antibody (D). (E) Schematic representation of recombinant proteins used in this assay. PY indicates tyrosine phosphorylation sites.

ΔLD1-2Hic-5 lacking LD1 and LD2 domains of hHic-5 significantly decreased cell spreading (62.2% reduction) compared to the control cells expressing EGFP, whereas ΔLD1-4Hic-5 lacking all of its four LD domains had no effect on spreading (Fig. 3B). These observations indicated that LD1 and LD2 domains are not required to inhibit cell spreading and suggested the importance of the region around the LD3 and LD4 domains. To determine whether LD3 and/or LD4 domains are necessary to prevent cell spreading, we generated ΔLD3-4Hic-5 lacking the LD3 and LD4 domains and ΔLD3 lacking the LD3 domain and used them in the spreading assay (Fig. 3A). ΔLD3-4Hic-5 and ΔLD3Hic-5 no longer inhibited cell spreading. These results suggested that the LD3 domain of Hic-5 is necessary for the inhibition of spreading on fibronectin. It should be noted that the LD3 domain of Hic-5 corresponds to the LD4 domain of paxillin, which associates with several interacting factors, including vinculin (6), FAK (6), and p95PKL (84).

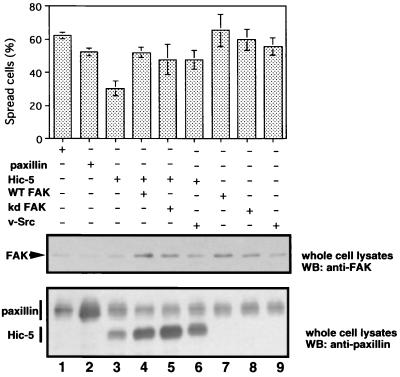

FAK seems to be involved in Hic-5-mediated inhibition of spreading.

Paxillin becomes phosphorylated on tyrosine residues in response to integrin-mediated cellular events that are associated with cytoskeletal remodeling (9, 83). Recent studies identified paxillin as a potential substrate for FAK and its associated kinase Src (3, 66) and showed that paxillin needed to bind to FAK for maximal phosphorylation in response to adhesion (79). Hic-5 overexpression may prevent cell spreading by sequestration of FAK, perhaps by competition between Hic-5 and paxillin. To assess this possibility, we cotransfected the LD1mHic-5 expression vector with wild-type FAK (WT FAK) or catalytically inactive FAK (kinase-defective [kd] FAK) expression vectors. Hic-5-mediated inhibition of spreading was efficiently rescued by coexpression of WT FAK (Fig. 4). Cotransfection of catalytically inactive kd FAK also restored the inhibitory effect of Hic-5 (Fig. 4). These observations indicated that FAK is a potential target for competition between Hic-5 and paxillin and that the kinase activity itself may not be necessary to rescue cell spreading. This observation is consistent with those of a previous study that showed that overexpression of catalytically inactive FAK variants restored pp41 and pp43 FRNK-mediated inhibition of cell spreading at levels comparable to those of WT FAK (57); these authors also proposed that FAK acts as an adapter molecule that recruits Src family kinase to phosphorylate paxillin and to promote cell spreading. To determine whether this model is applicable to Hic-5-mediated inhibition of cell spreading, we coexpressed Hic-5 and v-Src in NIH 3T3 cells. As shown in Fig. 4, coexpression of Hic-5 and v-Src reversed the inhibitory effects of Hic-5 on cell spreading.

FIG. 4.

FAK was a limiting factor in Hic-5-mediated inhibition of cell spreading. Upper panel. NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with pEGFP-N3 (GFP, lane 1), pCG-pax (HA-paxillin, lane 2), pCG-LD1mhic-5 (HA-LD1mHic-5, lane 3), LD1mHic-5 plus pSRα-FAK (WT FAK, lane 4), LD1mHic-5 plus pSRα minus FAK K454R (kinase-defective [kd] FAK, lane 5), or LD1mHic-5 plus pSRA2 (v-Src, lane 6) and allowed to spread on fibronectin-coated coverslips for 30 min, and the numbers of spread cells were determined in each case as described in the legends to Fig. 1. Lanes 7 to 9 represent cells transfected with GFP plus FAK, GFP plus kd FAK, or GFP plus v-Src, respectively. The numbers of spread cells were counted using cells labeled with anti-HA antibody or GFP. Each bar represents the mean of at least three independent experiments ± the SD. In the lower panel, cell extracts were prepared, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with antiserum indicated.

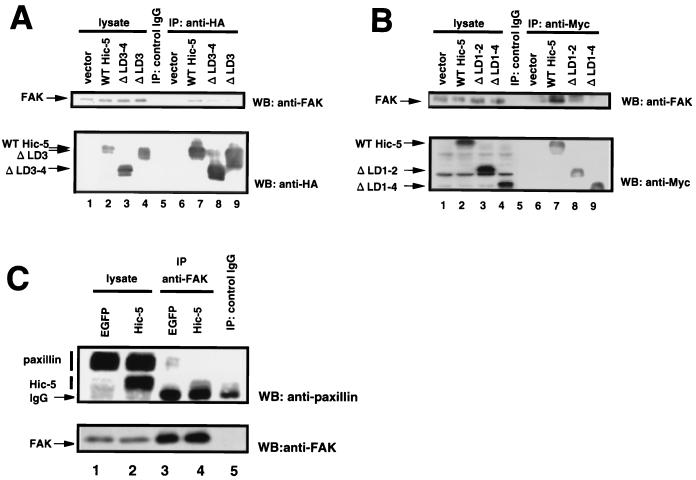

We demonstrated previously that Hic-5 interacts with FAK through its N-terminal region in vitro (15, 28). However, the region that is required for association with FAK in cells has not been clarified. Therefore, we investigated this point by coimmunoprecipitation (Fig. 5A and B) using epitope-tagged deletion mutants. HA and Myc tags were introduced at the N terminus or C terminus of Hic-5, respectively. HA-hHic-5, HA-ΔLD3-4hHic-5, HA-ΔLD3hHic-5, Myc-hHic-5, Myc-ΔLD1-2hHic-5, or Myc-ΔLD1-4hHic-5 were expressed in NIH 3T3 cells, immunoprecipitated with anti-HA or anti-Myc antibodies, and we then estimated the association with endogenous FAK. As shown in Fig. 5A, FAK was efficiently coimmunoprecipitated with WT hHic-5. ΔLD1-2hHic-5 modestly interacted with FAK. In ΔLD1-4 immunoprecipitation, coprecipitated FAK was hardly detectable, but a low level of background was seen. This may have been due to the presence of proteins that form a bridge between Hic-5 lacking all LD domains and FAK. Although ΔLD3-4- and ΔLD3hHic-5 has the LD2 domain corresponding to the region of paxillin reported to be involved in binding to FAK (84), ΔLD3-4- and ΔLD3hHic-5 showed decreased ability to associate with FAK. This may reflect the existence of complex mechanisms of association between Hic-5 and FAK or simply an unusual conformation caused by deletion. However, the LD3 domain of Hic-5 seems to be important for preventing cell spreading and for interaction with FAK.

FIG. 5.

Hic-5 competed with paxillin for FAK. NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with pCG-N-BL (an empty vector; lanes 3, 7, and 12), pCG-hhic-5 (HA-tagged WT Hic-5; lanes 4, 8, and 13), pCG-ΔLD3-4hhic-5 (HA-tagged ΔLD3-4; lanes 5, 9, and 14), or pCG-ΔLD3hhic-5 (HA-tagged ΔLD3; lanes 6, 10, and 15) (A) or with an empty vector (lanes 3, 7, and 12), pcDNA3. 1A-hhic-5 (Myc-tagged WT hHic-5; lanes 4, 8, and 13), pcDNA3.1A-ΔLD1-2hhic-5 (Myc-tagged ΔLD1-2; lanes 5, 9, and 14), or pcDNA3.1A-hic/LIM (Myc-tagged ΔLD1-4, lanes 6, 10, and 15). Total cell lysates were prepared, immunoprecipitated with anti-HA (A) or anti-Myc (B) antibody, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with anti-FAK, anti-HA, or anti-Myc antibody. Lane 1 represents whole-cell lysate, and lanes 2 and 11 indicate the results of immunoprecipitation with control IgG. Control extracts were prepared from cells transfected with tagged WT hHic-5. (C) MEFs were infected with viruses producing EGFP (lanes 1 and 3) or Myc-tagged mHic-5 (lanes 2 and 4). Total cell lysates were prepared, immunoprecipitated with anti-FAK antibody, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with antipaxillin antibody and anti-FAK antibody. Lane 5 represents a result of immunoprecipitation with control IgG. Lysate lanes contained one-fifth the amount of cellular proteins used for immunoprecipitation. The amounts of protein in each lane were corrected by cell numbers.

To determine whether Hic-5 overexpression actually sequesters FAK from paxillin, we compared the amount of coprecipitated paxillin from Hic-5-overexpressing cells with that of control cells. Exogenous genes were introduced into MEFs by a retrovirus-mediated method, and then the cells were stimulated with fibronectin and subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-FAK antibody. The amount of coprecipitated paxillin was determined by Western blotting by using antipaxillin antibody. As shown in Fig. 5C, coprecipitated paxillin was markedly reduced in immunoprecipitates derived from Hic-5-overexpressing cells. This indicated that the counterbalance between Hic-5 and paxillin expression can determine the efficiency of paxillin-FAK complex formation.

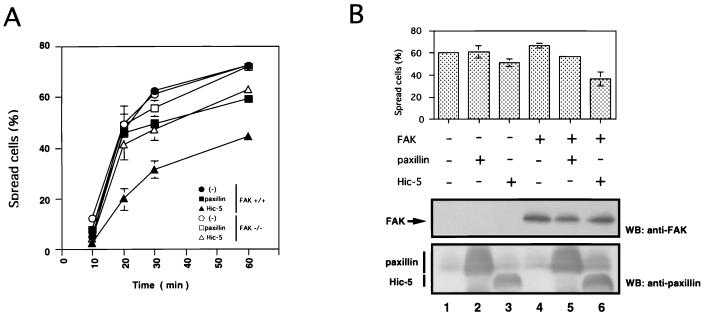

Recent studies have implicated FAK as a positive regulator of cell spreading and migration (52, 56, 57). However, a previous report suggested that FAK may be involved in the feedback loop that determines the turnover rate of focal adhesions. The observation that FAK-null cells showed enhanced formation of focal adhesions and reduced cell migration (27) suggested the existence of such negative signals. Thus, Hic-5-mediated inhibition of cell spreading may be due to an inhibitory signaling complex consisting of FAK and Hic-5 in addition to simple sequestration of FAK from paxillin. To confirm that FAK is required for Hic-5-mediated inhibition of cell spreading, we used MEFs derived from FAK−/− mice in the spreading assay. FAK−/− MEFs were transfected with paxillin or LD1mHic-5 expression vectors and allowed to spread on fibronectin-coated coverslips. LD1mHic-5 delayed spreading of FAK+/+ MEFs (24.7% ± 5.4%) and NIH 3T3 cells (data not shown). In contrast, the inhibitory effect of LD1mHic-5 on spreading was markedly weakened in FAK−/− MEFs (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, reconstitution of FAK−/− MEFs with exogenous FAK expression partially restored loss of spreading when LD1mHic-5 was cotransfected (Fig. 6B). This partial effect of FAK reconstitution may have been due to an inappropriate balance of the expression levels among exogenous genes. Single transfection of FAK slightly enhanced cell spreading, but the effect was faint in comparison with that reported previously (52). FAK itself seemed not to prevent cell spreading in immortalized cells which had a low level of Hic-5 expression. These results indicated that FAK is required for Hic-5-mediated inhibition of cell spreading. In addition, the requirement of FAK for a function of Hic-5 is consistent with a previous report in which the interaction between Hic-5 and FAK was shown to be necessary for a decrease in colony formation (28).

FIG. 6.

FAK seemed necessary for Hic-5-mediated inhibition of cell spreading. (A) MEFs derived from FAK−/− mice were transfected with pCG-pax (HA-paxillin) or pCG-LD1mhic-5 (HA-LD1mHic-5). Transfected cells were allowed to spread on fibronectin-coated coverslips for the indicated times and stained with anti-HA antibody, and the percentages of spread cells among those stained at each time point were calculated. Values represent the means of at least three independent experiments ± the SD. (B) FAK−/− MEFs were transfected with an empty vector (lanes 1 and 4), pCG-pax (HA-paxillin, lanes 2 and 5), or pCG-LD1mhic-5 (HA-LD1mHic-5, lanes 3 and 6) in the absence (lanes 1 to 3) or presence (Myc-WT FAK, lanes 4 to 6) of pSRα-FAK and allowed to spread on fibronectin-coated coverslips for 20 min. Upper panel, the numbers of spread cells were determined in each case as described above. Each bar represents the mean of at least three independent experiments ± the SD. For the lower panel, cell extracts were Western blotted with anti-FAK or antipaxillin antiserum.

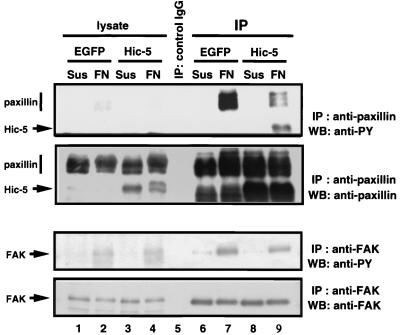

Hic-5 inhibits integrin-mediated paxillin phosphorylation.

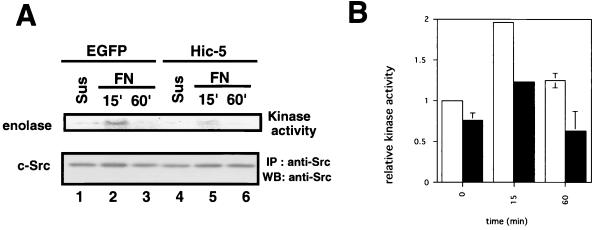

Paxillin is highly phosphorylated on tyrosine residues during various cellular events associated with cell adhesion, cytoskeletal reorganization, and growth signaling (43) and is recognized as a substrate of FAK and/or of kinases activated by FAK (66). In addition, physical interaction between paxillin and FAK is required for maximal phosphorylation of paxillin in response to cell adhesion (79). Since Hic-5 inhibited cell spreading after fibronectin stimulation, we tested whether Hic-5 influenced the integrin-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin in the presence or absence of Hic-5. Hic-5 or EGFP as a control was expressed by the retrovirus-mediated method in MEFs, and cells were replated onto fibronectin and lysed. The lysates were immunoprecipitated with corresponding antibodies and analyzed by immunoblotting with antiphosphotyrosine antibody. Paxillin and FAK were tyrosine phosphorylated in an adhesion-dependent manner in cells infected with both of these retroviruses (Fig. 7). However, the tyrosine phosphorylation level of paxillin was reduced in Hic-5-overexpressing cells relative to controls, a result consistent with the findings reported previously (15). In addition, we reproducibly observed a modest decrease in the tyrosine phosphorylation level of FAK in our system (Fig. 7, lower panels). We also examined c-Src kinase activity in cells infected with retroviral constructs. Immortalized MEFs were infected with retroviral constructs encoding EGFP or mouse Hic-5, and cells were kept in suspension or stimulated with fibronectin to be subjected to kinase reaction using enolase as a substrate. The results shown in Fig. 8 indicate that Hic-5 reduced c-Src kinase activity significantly.

FIG. 7.

Hic-5 reduced tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin. Immortalized MEFs were infected with retroviral constructs encoding EGFP (lanes 1, 2, 6, and 7) or mouse Hic-5 (lanes 4, 8, and 9). Cells were kept in suspension (S; lanes 1, 3, 6, and 8) or were stimulated on fibronectin (FN; lanes 2, 4, 7, and 9) for 60 min at 37°C. Cell lysates containing the same amount of protein were run directly (lanes 1 to 4) or were immunoprecipitated (lanes 6 to 9) with antipaxillin (upper panels) or anti-FAK (lower panels) antibody and then immunoblotted with antiphosphotyrosine antibody or with the corresponding antibodies. Lane 5 represents immunoprecipitate with control IgG.

FIG. 8.

Hic-5 reduced c-Src kinase activity. (A) Immortalized MEFs were infected with retroviral constructs encoding EGFP (lanes 1 to 3) or mouse Hic-5 (lanes 4 to 6). Cells were kept in suspension (Sus, lanes 1 and 4) or stimulated on fibronectin (FN; lanes 2, 3, 5, and 6) for 15 min (lanes 2 and 5) or 60 min (lanes 3 and 6) at 37°C. Cell lysates containing same amount of protein were immunoprecipitated with anti-c-Src and subjected to kinase reaction using enolase as a substrate. The reaction products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography (upper panel). Immunoprecipitated c-Src was immunoblotted with anti-c-Src antibody (lower panel). (B) Src kinase activity was calculated by dividing the radioactivities of the enolase bands by amounts of immunoprecipitated c-Src. Each bar represents the mean of three independent experiments ± the SD (open columns, EGFP-expressing cells; closed columns, Hic-5-expressing cells).

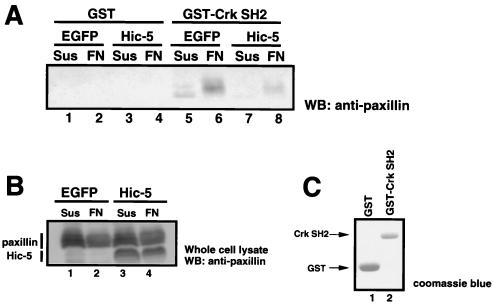

Tyrosine residues 31 and 118 of paxillin, which reside within a YXXP motif, are putative binding sites for the SH2 domain of Crk, an oncogenic adapter protein (4, 47, 66). A recent study indicated an important role of the paxillin-Crk complex formation through YXXP motifs in ECM-induced cell migration (53). Since YXXP motifs of paxillin become effective binding sites for Crk on phosphorylation (4, 66), the association of paxillin with the SH2 domain of Crk may be reduced in Hic-5-overexpressing cells in which paxillin is insufficiently phosphorylated. To confirm this possibility, we performed a pull-down assay using the SH2 domain of Crk expressed as a glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein. Hic-5-overexpressing cells were suspended or adhered to fibronectin and then lysed. The same amounts of lysates were incubated with GST-Crk SH2 immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose beads. The bound proteins were precipitated, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with antipaxillin antibody (Fig. 9). In the Hic-5-expressing cells, paxillin binding to the SH2 domain of Crk was significantly decreased, whereas paxillin in the control cells expressing EGFP was coprecipitated in an adhesion-dependent manner. Paxillin derived from cells used in this assay failed to bind to GST alone. These results were reproducibly observed and demonstrated that Hic-5 overexpression can interrupt phosphorylation of the Crk binding motif on paxillin and the formation of the paxillin-Crk complex. These observations may account for the inhibition of cell spreading in Hic-5-overexpressing cells.

FIG. 9.

Hic-5 inhibited paxillin-Crk complex formation. (A) Immortalized MEFs were infected with retroviral construct encoding EGFP (lanes 1 to 4) or mouse Hic-5 (lanes 5 to 8). Cells were kept in suspension (Sus; lanes 1, 2, 5, and 6) or stimulated on fibronectin (FN; lanes 3, 4, 7, and 8) for 60 min at 37°C. Cell lysates containing the same amount of protein were incubated for 1 h at 4°C with GST-Crk SH2 fusion protein (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8) or GST alone (lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7) Immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads. Bound proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with antipaxillin antibody. (B) Cells were infected with retroviral constructs encoding EGFP (lanes 1 and 2) or Hic-5 (lanes 3 and 4). Whole-cell lysates from MEFs kept in suspension (Sus, lanes 1 and 3) or plated on fibronectin (FN; lanes 2 and 4), and Western blotted with antipaxillin antiserum. (C) GST fusion proteins used in this experiment were visualized by Coomassie blue staining.

Rho family small GTPases are involved in Hic-5-mediated inhibition of spreading.

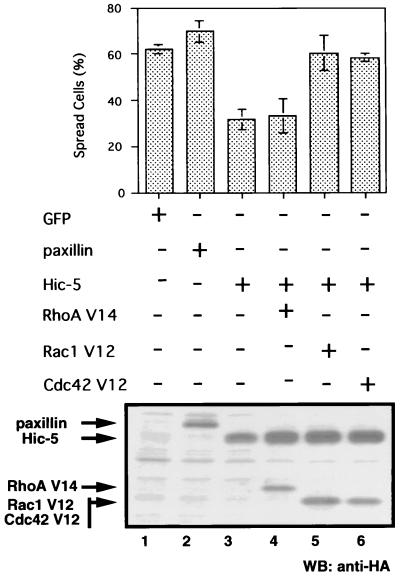

Crk is an adapter molecule consisting almost entirely of SH2 and SH3 domains (43). Paxillin and p130Cas, both of which are components of focal adhesion complexes (33), are two major Crk SH2-binding proteins. Numerous cellular proteins have recently been identified on the basis of interaction through the SH3 domain of Crk. Among these, DOCK180 is a downstream molecule of integrin-mediated signal transduction (22, 34). DOCK180 can directly bind to and activate Rac1, a small G protein involved in the regulation of the actin cytoskeleton (35). As discussed by Petit et al. (53), paxillin-Crk complex formation could link integrin stimulation to downstream molecules, and thus this complex may promote actin reorganization, cell spreading, and migration. To further investigate the involvement of Hic-5 in downstream signaling, we examined whether constitutively active forms of Rho family GTPases, i.e., RhoA V14, Rac1 V12, and Cdc42 V12, could bypass the spreading-deficient phenotype observed in cells overexpressing Hic-5. NIH 3T3 cells were cotransfected with the LD1mHic-5 expression vector with RhoA V14, Rac1 V12, or Cdc42 V12 expression vectors and subjected to spreading assay. Coexpression of Rac1 V12 or Cdc42 V12 resulted in the restoration of cell spreading (Fig. 10). This finding was consistent with the results of a previous study in which Rac1 and Cdc42 were reported to contribute to early-phase cell spreading (55). In contrast, transfection with RhoA V14 did not rescue LD1mHic-5-mediated inhibition of cell spreading. These findings agreed with the observation that DOCK180 elevates the GTP/GDP ratio of Rac1 but not of RhoA (35). The results obtained here suggested that Hic-5 influences the signaling pathways in which Rac1 and Cdc42 are involved during the early phase of cell spreading.

FIG. 10.

Constitutively active Cdc42 and Rac-1 rescued Hic-5-mediated inhibition of spreading. NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with pGFP (lane 1), pCG-pax (HA-paxillin, lane 2), or pCG-LD1mhic-5 (HA-LD1mHic-5, lanes 3 to 6), in the presence of pEF BOS (empty vector, lanes 3), pEF BOS RhoA DA (HA-RhoA V14, lane 4), pEF BOS Rac1 DA (HA-Rac1 V12, lane 5), or pEF BOS Cdc42 DA (HA-Cdc42 V12, lane 6). In the upper panel, cells were allowed to spread on fibronectin-coated coverslips for 30 min, and the numbers of spread cells were determined in each case as described above. Each bar represents the mean of at least three independent experiments ± the SD. In the lower panel, cell extracts were Western blotted with anti-HA antibody.

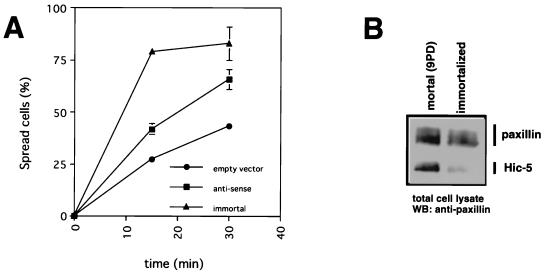

Effect of antisense expression of Hic-5 on spreading.

The expression level of Hic-5 is markedly decreased during immortalization of MEFs (28, 70). To investigate the participation of endogenous Hic-5 in the early phase of cell spreading, we expressed antisense Hic-5 in mortal MEFs that contained higher levels of Hic-5. As shown in Fig. 11, mortal MEFs (nine population doublings) with increased Hic-5 expression showed a delayed spreading rate relative to that of immortalized MEFs of at least within 60 min, and the expression of antisense Hic-5 in mortal MEFs restored spreading activity, at least in part (Fig. 11A). Furthermore, the forced expression of Hic-5 caused inhibition of early-phase cell spreading as described above (Fig. 6). These observations indicated that the constitutive levels of Hic-5 expression are correlated with the cell spreading rate in the early phase. These observations suggest that Hic-5 inhibits the cell spreading rate only at the early phase and that the early and late phases of cell spreading are different processes that may involve different molecules.

FIG. 11.

Effect of antisense expression of Hic-5 on spreading abilities. (A) Mortal MEFs were transfected with an empty vector (●) or an antisense expression vector of Hic-5 (■), together with GFP. At 48 h after transfection, cells were allowed to spread on fibronectin-coated coverslips for the indicated times and stained with rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin, and the percentages of spread cells at each time point were calculated. Values represent the means of at least three independent experiments ± the SD. The spreading ability was measured as described above. The spreading activity of immortal MEFs (▴) was also examined. (B) Cell lysates from mortal and immortal MEFs were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using anti-paxillin antibody.

DISCUSSION

Focal adhesions are formed following stimulation of integrins and are composed of numerous scaffold, docking proteins, as well as signal transduction molecules. The structurally related molecules paxillin and Hic-5 are colocalized in focal adhesions, thereby docking several signal transducers. We previously reported the involvement of Hic-5, a paxillin homologue, in cellular senescence (70) and the specific decrease in Hic-5 expression levels during the immortalization of MEFs (28). Despite its unique features, the molecular basis of Hic-5 function has not been fully clarified. In this study, we demonstrated that the counterbalance between Hic-5 and paxillin expression is a determinant of integrin-mediated cellular events, including cell spreading, phosphorylation of focal adhesion proteins, and downstream signaling.

Competitive effects between Hic-5 and paxillin on cell spreading.

Hic-5 and paxillin share a closely related structure and common interaction factors. Paxillin has phosphotransfer sites that serve as putative target sites for the SH2 domain of Crk (3, 66), implying the involvement in downstream signals such as proliferation and cytoskeletal organization. However, unlike paxillin, Hic-5 is not phosphorylated on tyrosine by integrin stimulation (15). Furthermore, the Hic-5 expression level is specifically decreased during immortalization, whereas that of paxillin tends to be increased (28). Taken together, we hypothesized that Hic-5 may not transduce signals downstream and may antagonize paxillin and that the balance between Hic-5 and paxillin expression may influence integrin-mediated signal transduction. To address these possibilities, we overexpressed exogenous Hic-5 in immortalized mouse fibroblasts in which Hic-5 was expressed at a relatively low level and assessed the effects on cell spreading. In the present study, we show that Hic-5 overexpression inhibited cell spreading on fibronectin. This inhibitory effect was rescued by coexpression of paxillin in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2), suggesting that Hic-5 and paxillin compete for a common interacting factor(s), the association of which with paxillin is necessary for cell spreading.

Hic-5 is composed of an N-terminal region containing four LD domains (7) and a C-terminal region containing four LIM domains (67). The LD and the LIM domains have been suggested to be structures that associate with interacting factors. Indeed, the N-terminal half of Hic-5 binds to various proteins, including FAK (6, 15, 28), Pyk2/CAKβ/RAFTK (45), vinculin (6), and p95PKL (84), and LIM domains interact with PTP-PEST (50). These are common interacting factors with paxillin and thus may be possible targets for competition between Hic-5 and paxillin in the focal adhesion complexes. In particular, FAK (52, 56, 57) and PTP-PEST (1) have been reported to be involved in cell spreading. PTP-PEST regulates focal adhesion disassembly and actin cytoskeleton and migration through dephosphorylation of p130Cas (1, 16). The involvement of PTP-PEST is a possible mechanism of Hic-5-mediated inhibition of cell spreading. Studies using deletion mutants of Hic-5 are useful to determine the regions and interacting factors required for the function: however, LIM domains of Hic-5 are required for its proper intracellular localization, and LIM mutants used in a previous study could not interfere with the in vivo interaction between LIM domains and PTP-PEST (50). Therefore, we did not use constructs with mutations within LIM domains in this study. In contrast, all N-terminal deletion mutants tested, even a mutant in which all four LD domains were deleted, localized precisely to the focal adhesions. Comparison of the effects of N-terminal deletion constructs on cell spreading with those of the wild-type Hic-5 construct revealed that the LD3 domain on Hic-5 was required for the Hic-5-mediated inhibition of cell spreading. This region is a possible binding site for FAK since the corresponding domain (LD4 domain) of paxillin has been reported to serve as one of the FAK binding domains (6). These regions have 85% amino acid identity. Indeed, ΔLD3-4 and ΔLD3 could not interact with FAK (Fig. 5). Recent studies have suggested that FAK may act as a positive regulator of cell spreading and migration (52, 56, 57). Therefore, Hic-5-mediated inhibition of cell spreading seems to involve FAK. Indeed, the inhibitory effect was rescued by coexpression of FAK (Fig. 4). Recently, the association between FAK and paxillin has been reported to contribute to maximal tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin in response to cell adhesion (79). In the present study, we observed that Hic-5 overexpression sequestered FAK from paxillin (Fig. 5) and reduced tyrosine phosphorylation of FAK and paxillin (Fig. 7), confirming the previous results (15).

Roles of FAK in cell spreading.

Richardson and Parsons reported that the C-terminal domain of FAK (pp41 and pp43 FRNK) acts as an inhibitor of FAK by delaying cell spreading on fibronectin; reducing tyrosine phosphorylation of FAK, paxillin, and tensin, and transiently blocking the formation of focal adhesions (56). These FRNK-mediated inhibitory effects were rescued by coexpression of FAK but not by coexpression of a FAK variant lacking the paxillin-binding site (cFAK) (57), suggesting that the binding of FAK to paxillin and tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin play important roles in integrin-mediated cytoskeletal organization leading to cell spreading. Taken together, these observations indicated that Hic-5-mediated inhibition of cell spreading is probably mediated by similar mechanisms to that in the case of pp41 and pp43 FRNK.

In addition to simple sequestration of FAK from paxillin, more complex FAK-dependent mechanisms may contribute to Hic-5-mediated inhibition of cell spreading. The expression of the FAK-related tyrosine kinase, Pyk2/Cakβ/RAFTK (2, 41, 64), is elevated in MEFs derived from FAK-null mice compared with wild-type MEFs (72). FAK and Pyk2/Cakβ/RAFTK have been suggested to share common substrates and facilitate linkages between integrins and cytoskeletal proteins such as paxillin and Hic-5 (24, 45, 61, 82). Sieg et al. reported that Pyk2/Cakβ/RAFTK functions in a compensatory manner to promote integrin-mediated signaling in FAK−/− MEFs (72). Although Pyk2/Cakβ/RAFTK is one of the Hic-5 binding tyrosine kinases, Hic-5-mediated inhibition of cell spreading was decreased in FAK−/− MEFs (Fig. 6), suggesting that the contribution of FAK is more significant in the Hic-5-mediated inhibitory effect compared to Pyk2/Cakβ/RAFTK. Interestingly, c-Src activity is enhanced in FAK−/− MEFs compared with that in FAK+/+ MEFs (72). Thus, the regulation of c-Src activity may be important for Hic-5-mediated inhibition of cell spreading observed in FAK+/+ MEFs. Indeed, coexpression of v-Src restored Hic-5-mediated inhibition of spreading (Fig. 4), and the activity of c-Src in fibronectin-stimulated cells was reduced by forced expression of Hic-5 (Fig. 8). The elevated c-Src activity in FAK−/− MEFs may be due to enhanced dephosphorylation of the phosphorylation site for Csk, a Hic-5-associated kinase, in the C-terminal region of c-Src (72). The Csk site on c-Src has been known to be a negative regulatory phosphorylation site (12, 37), which is dephosphorylated upon fibronectin stimulation, resulting in c-Src activation (31). Furthermore, Csk has recently been reported to interfere with cell spreading (75). We speculated that Hic-5-mediated inhibition of cell spreading involves c-Src, although the precise mechanism is unclear at present.

Significance of tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin in signals for spreading.

One of the processes that follows paxillin phosphorylation is signal transduction through the docking of SH2 proteins (38). Tyrosine phosphorylation of two major sites, Y31 and Y118, on paxillin creates binding sites for the SH2 domain of the adapter protein Crk (3, 66). Although paxillin and Hic-5 show marked homology over their entire structures, Hic-5 does not have the tyrosine residue that serves as a site for Crk binding. In fact, no interaction between Hic-5 and Crk SH2 was detected even under forced phosphorylation by treatment with pervanadate (29). In the present study, we showed that formation of the paxillin-Crk complex is prevented in Hic-5-overexpressing cells (Fig. 9). This prevention probably resulted from diminished tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin by sequestration of FAK. A recent study indicated that phosphorylation of Y31 and Y118 on paxillin plays a critical role in the collagen-induced migration of NBT-II cells. Mutations in Y31 and Y118 impaired motility, diminished tyrosine phosphorylation and prevented formation of the paxillin-Crk complex (53).

Crk is an adapter protein that consists mostly of SH2 and SH3 domains (43) and connects tyrosine phosphorylated proteins, such as paxillin and p130Cas, to downstream signal transducers through SH2 and SH3 domains. Among SH3-associated proteins, DOCK180 is a downstream molecule of integrin-mediated signal transduction (22, 34). DOCK180 directly binds to Rac1, a member of the Rho family of small GTPases that regulates and activates the actin cytoskeleton (35). Activation of Rac1 is necessary for the early phase of cell spreading (55). The membrane targeting and coexpression of Crk and p130Cas enhances DOCK180-dependent activation of Rac1 (35). Similarly to p130Cas, phosphorylated paxillin presumably recruits DOCK180 to the membrane fraction through Crk, subsequently activating Rac. Therefore, Hic-5-mediated inhibition of cell spreading may involve the regulation of Rac1 activity through the reduction of paxillin-Crk-DOCK180-Rac complex formation. In addition to the paxillin-Crk-DOCK180 complex, the involvement of p95PKL, a paxillin interaction factor, has not yet been excluded. p95PKL forms the paxillin-p95PKL-PAK-PIX complex, which has been suggested to mediate Rac function (84).

The Rho family of small GTPases, including Rho, Rac, and Cdc42, regulates the actin cytoskeleton (20). Previous reports have shown that Rho stimulates organization of actin stress fibers, Rac stimulates membrane ruffling and the formation of lamellipodia, and Cdc42 induces the formation of filopodia (51). Among these small GTPases, the activities of Rac and Cdc42 are necessary for cell spreading (55). Since Hic-5-mediated inhibition of cell spreading might involve Rac1 function as described above, we assessed the effects of constitutively active forms of Rho family small GTPases. Although DOCK180 activates Rac specifically (35), constitutive active forms of Rac1 and Cdc42 rescued Hic-5-mediated inhibition of spreading (Fig. 10). It may have been that activated Cdc42 leads to the subsequent activation of Rac, which then contributes to cell spreading (55).

Endogenous levels of Hic-5 were higher in mortal MEFs (28, 70), and its decrease by antisense expression vector increased spreading significantly (Fig. 11). These results indicate that the effect of forced expression of Hic-5 was not due to an artifact. Furthermore, we previously showed that the levels of paxillin and Hic-5 were antiparallel in the immortalization process of MEFs. Possibly, the relative balance of these homologues affects spreading and other cellular behaviors through the modulation of FAK and c-Src.

Crk binds to tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins through the SH2 domain and to the effector proteins through the SH3 domains (14, 77). Thus, Crk recruits signaling molecules such as guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs), C3G and SOS (14, 77) as well as DOCK180, to tyrosine phosphorylated proteins. Tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin results in the recruitment of these GEFs to focal adhesions that are built on the plasma membrane. C3G and SOS act as upstream regulators for Rap1A/k-Rev1 and Ras, respectively (18, 73). These small GTPases are involved in the regulation of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases (13, 32). Previous studies using dominant-negative mutants of Crk demonstrated the involvement of Crk in the activation of the MAP kinase pathway (36, 76). Therefore, the phosphorylation of paxillin may be involved in the regulation of MAP kinase through the pathway including Crk and its effector proteins. MAP kinases are activated by a variety of mitogenic stimuli and regulate proliferation. Since tyrosine phosphorylation on paxillin is decreased by the overexpression of Hic-5, the growth-inhibitory effect of Hic-5 is probably due to the inhibition of the MAP kinases. Further studies will lead to a clearer understanding of the relationship between mortality control and ECM components.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Kohzoh Kaibuchi (Nara Institute of Science and Technology, Ikoma, Japan) for providing Rho-family GTPase expression vectors, Michel L. Tremblay (McGill University, Montreal, Canada) for GST fusion Crk SH2 expression vectors, and Tadashi Yamamoto (Institute of Medical Science, University of Tokyo, Minato-ku, Japan) for MEFs from FAK-null mice. Anti-Cas antibody was kindly provided by Tatsuya Nakamoto, University of Tokyo Medical School. We also thank Takeshi Shirai, Momoko Fujisaki, Wataru Suzuki, and Tomoko Kanome for technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by grants-in-aid for Scientific Research, a grant-in-aid for Cancer Research, and the High-Technology Research Center Project from the ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture of Japan and by a grant-in-aid from the Takeda Science Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Angers-Loustau A, Cote J-F, Charest A, Dowbenko D, Spencer S, Lasky L A, Tremblay M L. Protein tyrosine phosphatase-PEST regulates focal adhesion disassembly, migration, and cytokinesis in fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:1019–1031. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.5.1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avraham S, London R, Fu Y, Ota S, Hiregowdara D, Li J, Jiang S, Pasztor L M, White R A, Groopman J E, Avraham H. Identification and characterization of a novel related adhesion focal tyrosine kinase (RAFTK) from megakaryocytes and brain. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:27742–27751. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.46.27742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellis S L, Miller J T, Turner C E. Characterization of tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin in vitro by focal adhesion kinase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17437–17441. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.29.17437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birge R B, Fajardo J E, Reichman C, Shoelson S E, Songyang Z, Cantley L C, Hanafusa H. Identification and characterization of a high-affinity interaction between v-Crk and tyrosine-phosphorylated paxillin in CT10-transformed fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:4648–4656. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.8.4648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bockholt S M, Burridge K. Cell spreading on extracellular matrix proteins induces tyrosine phosphorylation of tensin. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:14565–14567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown M C, Perrotta J A, Turner C E. Identification of LIM3 as the principal determinant of paxillin focal adhesion localization and characterization of a novel motif on paxillin directing vinculin and focal adhesion kinase binding. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:1109–1123. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.4.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown M C, Curtis M S, Turner C E. Paxillin LD motifs may define a new family of protein recognition domains. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:677–678. doi: 10.1038/1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burridge K, Fath K, Kelly T, Nuckolls G, Turner C E. Focal adhesions: transmembrane junctions between the extracellular matrix and the cytoskeleton. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1988;4:487–525. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.04.110188.002415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burridge K, Turner C E, Romer L H. Tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin and pp 125 FAK accompanies cell adhesion to extracellular matrix: a role in cytoskeletal assembly. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:898–903. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.4.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark E A, Brugge J S. Integrins and signal transduction pathways: the road taken. Science. 1995;268:233–239. doi: 10.1126/science.7716514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cote J-F, Turner C E, Tremblay M L. Intact LIM 3 and LIM 4 domains of paxillin are required for the association to a novel polyproline region (Pro 2) of protein-tyrosine phosphatase-PEST. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:20550–20560. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.29.20550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Courtneidge S A. Activation of the pp60c-src kinase by middle T antigen binding or by dephosphorylation. EMBO J. 1985;4:1471–1477. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03805.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis R J. MAPKs: new JNK expands the group. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19:470–473. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feller S M, Knudsen B, Hanafusa H. Cellular proteins binding to the first Src homology 3 (SH3) domain of the proto-oncogene product c-Crk indicate Crk-specific signaling pathways. Oncogene. 1995;10:1465–1473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujita H, Kamiguchi K, Cho D, Shibanuma M, Morimoto C, Tachibana K. Interaction of Hic-5, a senescence-related protein, with focal adhesion kinase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:26516–26521. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garton A J, Tonks N K. Regulation of fibroblast motility by the protein tyrosine phosphatase PTP-PEST. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:3811–3818. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.6.3811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glenney J R, Jr, Zokas L. Novel tyrosine kinase substrates from Rous sarcoma virus-transformed cells are present in the membrane skeleton. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:2401–2408. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.6.2401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gotoh T, Hattori S, Nakamura S, Kitayama H, Noda M, Takai Y, Kaibuchi K, Matsui H, Hatase O, Takahashi H. Identification of Rap1 as a target for the Crk SH3 domain-binding guanine nucleotide-releasing factor C3G. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;1995 15:6746–6753. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.12.6746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guan J L, Shalloway D. Regulation of focal adhesion-associated protein tyrosine kinase by both cellular and oncogenic transformation. Nature. 1992;358:690–692. doi: 10.1038/358690a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hall A. Rho GTPases and the actin cytoskeleton. Science. 1998;279:509–514. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanks S K, Polte T R. Signaling through focal adhesion kinase. Bioessays. 1997;19:137–145. doi: 10.1002/bies.950190208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hasegawa H, Kiyokawa E, Tanaka S, Nagashima K, Gotoh N, Shibuya M, Kurata T, Matsuda M. DOCK180, a major CRK-binding protein, alters cell morphology upon translocation to the cell membrane. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1770–1776. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.4.1770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hemler M E. VLA proteins in the integrin family: structures, functions, and their role on leukocytes. Annu Rev Immunol. 1990;8:365–400. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.08.040190.002053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hildebrand J D, Schaller M D, Parsons J T. Paxillin, a tyrosine phosphorylated focal adhesion-associated protein binds to the carboxyl terminal domain of focal adhesion kinase. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:637–647. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.6.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirai H, Suzuki T, Fujisawa J, Inoue J, Yoshida M. Tax protein of human T-cell leukemia virus type I binds to the ankyrin motifs of inhibitory factor B and induces nuclear translocation of transcription factor NF-B proteins for transcriptional activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3584–3588. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hynes R O. Integrins: versatility, modulation, and signaling in cell adhesion. Cell. 1992;69:11–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90115-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Illic D, Furuta Y, Kanazawa S, Tanaka N, Sobue K, Nakatsuji N, Nomura S, Fujimoto J, Okada M, Yamamoto T. Reduced cell motility and enhanced focal adhesion contact formation in cells from FAK-deficient mice. Nature. 1995;377:539–544. doi: 10.1038/377539a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ishino K, Kaneyama J, Shibanuma M, Nose K. Specific decrease in the level of Hic-5, a focal adhesion protein, during immortalization of mouse embryonic fibroblasts, and its association with focal adhesion kinase. J Cell Biochem. 2000;76:411–419. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(20000301)76:3<411::aid-jcb9>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ishino M, Aoto H, Sasaski H, Suzuki R, Sasaki T. Phosphorylation of Hic-5 at tyrosine 60 by CAK β and Fyn. FEBS Lett. 2000;474:179–183. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01597-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Juliano R L, Haskill S. Signal transduction from the extracellular matrix. J Cell Biol. 1993;120:577–585. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.3.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaplan K B, Swedlow J R, Morgan D O, Varmus H E. c-Src enhances the spreading of src−/− fibroblasts on fibronectin by a kinase-independent mechanism. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1505–1517. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.12.1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kitayama H, Sugimoto Y, Matsuzaki T, Ikawa Y, Noda M. A ras-related gene with transformation suppressor activity. Cell. 1989;56:77–84. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90985-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kiyokawa E, Mochizuki N, Kurata T, Matsuda M. Role of Crk oncogene product in physiologic signaling. Crit Rev Oncog. 1997;8:329–342. doi: 10.1615/critrevoncog.v8.i4.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kiyokawa E, Hashimoto Y, Kurata T, Sugimura H, Matsuda M. Evidence that DOCK180 up-regulates signals from the CrkII-p130C as complex. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:24479–24484. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.38.24479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kiyokawa E, Hashimoto Y, Kobayashi S, Sugimura H, Kurata T, Matsuda M. Activation of Rac1 by a Crk SH3-binding protein, DOCK180. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3331–3336. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.21.3331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kizaka-Kondoh S, Matsuda M, Okayama H. CrkII signals from epidermal growth factor receptor to Ras. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12177–12182. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kmiecik T E, Shalloway D. Activation and suppression of pp60c-src transforming ability by mutation of its primary sites of tyrosine phosphorylation. Cell. 1987;49:65–73. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90756-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koch C A, Anderson D, Moran M F, Ellis C, Pawson T. SH2 and SH3 domains: elements that control interactions of cytoplasmic signaling proteins. Science. 1991;252:668–674. doi: 10.1126/science.1708916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kozak M. At least six nucleotides preceding the AUG initiator codon enhance translation in mammalian cells. J Mol Biol. 1987;196:947–950. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kozma R, Ahmed S, Best A, Lim L. The Ras-related protein Cdc42Hs and bradykinin promote formation of peripheral actin microspikes and filopodia in Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:1942–1952. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.4.1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lev S, Moreno H, Martinez R, Canoll P, Peles E, Musacchio J M, Plowman G D, Rudy B, Schlessinger J. Protein tyrosine kinase PYK2 involved in Ca2+-induced regulation of ion channel and MAP kinase functions. Nature. 1995;376:737–745. doi: 10.1038/376737a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manser E, Huang H Y, Loo T H, Chen X Q, Dong J M, Leung T, Lim L. Expression of constitutively active alpha-PAK reveals effects of the kinase on actin and focal complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1129–1143. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matsuda, M., S. Tanaka, S. Nagata, A. Kojima, T. Kurata, and M. Shibuya. Two species of human CRK cDNA encode proteins with distinct biological activities. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:3482–3489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Matsuda M, Hashimoto Y, Muroya K, Hasegawa H, Kurata T, Tanaka S, Nakamura S, Hattori S. CRK protein binds to two guanine nucleotide-releasing proteins for the Ras family and modulates nerve growth factor-induced activation of Ras in PC12 cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:5495–5500. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.8.5495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsuya M, Sasaki H, Aoto H, Mitaka T, Nagura K, Ohba T, Ishino M, Takahashi S, Suzuki R, Sasaki T. Cell adhesion kinase beta forms a complex with a new member, Hic-5, of proteins localized at focal adhesions. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:1003–1114. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.2.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matsuyama T, Yamada A, Kay J, Yamada K M, Akiyama S K, Schlossman S F, Morimoto C. Activation of CD4 cells by fibronectin and anti-CD3 antibody: a synergistic effect mediated by the VLA-5 fibronectin receptor complex. J Exp Med. 1989;170:1133–1148. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.4.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mayer B J, Hamaguchi M, Hanafusa H. A novel viral oncogene with structural similarity to phospholipase C. Nature. 1988;332:272–275. doi: 10.1038/332272a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mazaki Y, Hashimoto S, Sabe H. Monocyte cells and cancer cells express novel paxillin isoforms with different binding properties to focal adhesion proteins. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:7437–7444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.11.7437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Naviaux R K, Costanzi E, Haas M, Verma I M. The pCL vector system: rapid production of helper-free, high-titer, recombinant retroviruses. J Virol. 1996;70:5701–5705. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5701-5705.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nishiya N, Iwabuchi Y, Shibanuma M, Cote J-F, Tremblay M L, Nose K. Hic-5, a paxillin homologue, binds to the protein-tyrosine phosphatase PEST (PTP-PEST) through its LIM 3 domain. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:9847–9853. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nobes C D, Hall A. Rho, Rac, and cdc42 GTPases regulate the assembly of multimolecular focal complexes associated with actin stress fibers, lamellipodia, and filopodia. Cell. 1995;81:53–62. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90370-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Owen J D, Ruest P J, Fry D W, Hanks S K. Induced focal adhesion kinase (FAK) expression in FAK-null cells enhances cell spreading and migration requiring both auto- and activation loop phosphorylation sites and inhibits adhesion-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of Pyk2. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:4806–4818. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.7.4806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Petit V, Boyer B, Lentz D, Turner C E, Thiery J P, Valls A M. Phosphorylation of tyrosine residues 31 and 118 on paxillin regulates cell migration through an association with CRK in NBT-II cells. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:957–970. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.5.957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Polte T R, Hanks S K. Complexes of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and Crk-associated substrate (p 130cas) are elevated in cytoskeleton-associated fractions following adhesion and Src transformation. Requirements for Src kinase activity and FAK proline-rich motif. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:5501–5509. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.9.5501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Price L S, Leng J, Schwartz M A, Bokoch G M. Activation of Rac and Cdc42 by integrins mediates cell spreading. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:1863–1871. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.7.1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Richardson A, Parsons T. A mechanism for regulation of the adhesion-associated protein tyrosine kinase pp 125FAK. Nature. 1996;380:538–540. doi: 10.1038/380538a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Richardson A, Malik R K, Hildebrand J D, Parsons J T. Inhibition of cell spreading by expression of the C-terminal domain of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) is rescued by coexpression of Src or catalytically inactive FAK: a role for paxillin tyrosine phosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6906–6914. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.12.6906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Romer L H, McLean N, Turner C E, Burridge K. Tyrosine kinase activity, cytoskeletal organization, and motility in human vascular endothelial cells. Mol Biol Cell. 1994;5:349–361. doi: 10.1091/mbc.5.3.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ruoslahti E, Reed J C. Anchorage dependence, integrins, and apoptosis. Cell. 1994;77:477–478. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90209-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sakai R, Iwamatsu A, Hirano N, Ogawa S, Tanaka T, Masno H, Yazaki Y, Hirai H. A novel signaling molecule, p130, forms stable complexes in vivo with v-Crk and v-Src in a tyrosine phosphorylation-dependent manner. EMBO J. 1994;13:3748–3756. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Salgia R, Avraham S, Pisick E, Li J, Raja S, Greenfield E A, Sattler M, Avraham H, Griffin J D. The related adhesion focal tyrosine kinase forms a complex with paxillin in hematopoietic cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:31222–31226. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sander E E, ten Klooster J P, van Delft S, van der Kammen R A, Collard J G. Rac downregulates Rho activity: reciprocal balance between both GTPases determines cellular morphology and migratory behavior. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:1009–1022. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.5.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sasaki H, Nagura K, Ishino M, Tobioka H, Kotani K, Sasaki T. Cloning and characterization of cell adhesion kinase, a novel protein-tyrosine kinase of the focal adhesion kinase subfamily. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:21206–21219. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.36.21206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sanders L C, Matsumura F, Bokoch G M, de Lanerolle P. Inhibition of myosin light chain kinase by p21-activated kinase. Science. 1999;283:2083–2085. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5410.2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schaller M D, Borgman C A, Cobb B S, Vines R R, Reynolds A B, Parsons J T. pp125FAK, a structurally distinctive protein-tyrosine kinase associated with focal adhesions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5192–5196. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.11.5192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schaller M D, Parsons J T. pp125FAK-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin creates a high-affinity binding site for Crk. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2635–2645. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.5.2635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schmeichel K L, Beckerle M C. The LIM domain is a modular protein-binding interface. Cell. 1994;79:211–219. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schwartz M A, Schaller M D, Ginsberg M H. Integrins: emerging paradigms of signal transduction. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1995;11:549–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.11.110195.003001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shibanuma, M., J. Mashimo, T. Kuroki, and K. Nose. Characterization of the TGF beta 1-inducible hic-5 gene that encodes a putative novel zinc finger protein and its possible involvement in cellular senescence. J. Biol. Chem. 17:26767–26774. [PubMed]