Abstract

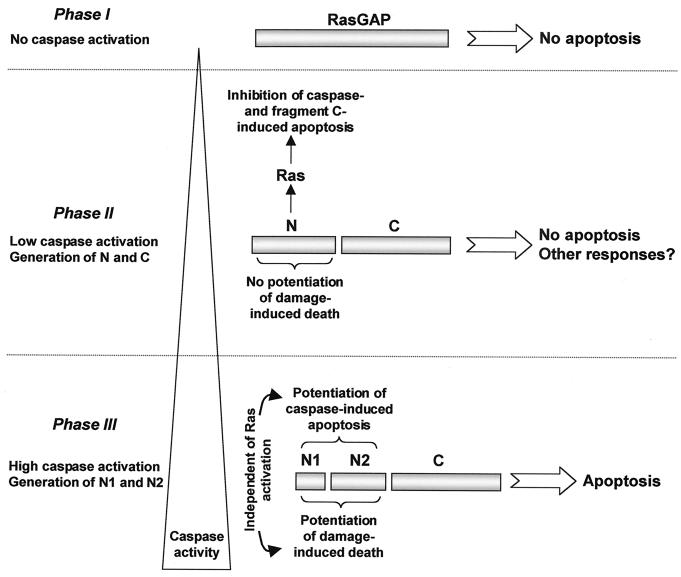

Activation of caspases 3 and 9 is thought to commit a cell irreversibly to apoptosis. There are, however, several documented situations (e.g., during erythroblast differentiation) in which caspases are activated and caspase substrates are cleaved with no associated apoptotic response. Why the cleavage of caspase substrates leads to cell death in certain cases but not in others is unclear. One possibility is that some caspase substrates generate antiapoptotic signals when cleaved. Here we show that RasGAP is one such protein. Caspases cleave RasGAP into a C-terminal fragment (fragment C) and an N-terminal fragment (fragment N). Fragment C expressed alone induces apoptosis, but this effect could be totally blocked by fragment N. Fragment N could also block apoptosis induced by low levels of caspase 9. As caspase activity increases, fragment N is further cleaved into fragments N1 and N2. Apoptosis induced by high levels of caspase 9 or by cisplatin was strongly potentiated by fragment N1 or N2 but not by fragment N. The present study supports a model in which RasGAP functions as a sensor of caspase activity to determine whether or not a cell should survive. When caspases are mildly activated, the partial cleavage of RasGAP protects cells from apoptosis. When caspase activity reaches levels that allow completion of RasGAP cleavage, the resulting RasGAP fragments turn into potent proapoptotic molecules.

Apoptosis is a vital phenomenon that participates in the elimination of unwanted or potentially harmful cells. Every cell in a multicellular organism possesses the machinery to undergo apoptosis in response to an appropriate death signal (e.g., stimulation of death receptors). The biochemical event that is believed to commit a cell irreversibly to apoptosis is the activation of caspases, a family of proteases that cleave their substrates after aspartic residues (25). Cells undergoing apoptosis display characteristic morphological and biochemical changes, including membrane blebbing, cell rounding, chromatin condensation, DNA cleavage, expression of apoptotic markers at the cell surface, and inhibition of antiapoptotic signaling pathways. All of these events can be blocked by specific caspase inhibitors (23, 28). It is thus the cleavage of the caspase substrates that is responsible for most, if not all, of the characteristic changes observed during apoptosis. Consequently, understanding the apoptotic process requires that the caspase substrates be identified, followed by the characterization of the functional roles of each cleavage event in the regulation of cell death.

The caspase family of proteases can be divided in three groups based on substrate specificity (23, 25). Group I (ICE subfamily) is composed of caspases that do not play a direct role in apoptosis but rather participate in the maturation of proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β and gamma interferon-inducing factor (13, 26). Group II and group III (CED-3 subfamily), on the other hand, correspond to initiator caspases and executioner caspases, which are directly involved in the apoptotic process (37).

Although the involvement of caspases of the CED-3 subfamily has been widely confirmed for most apoptotic responses, there are a few cases where these proteases have been suggested to play roles other than controlling the onset of apoptosis. One recent example is the demonstration that caspases stimulated by activated death receptors participate in the negative regulation of erythropoiesis by cleaving GATA-1, a transcription factor required for differentiation of mature erythroblasts (7). Importantly, this negative regulation occurs in the absence of any significant apoptotic response. Thus, in proerythroblasts, there must be a mechanism, as yet uncharacterized, that prevents caspases of the CED-3 subfamily from causing apoptosis. The notion that caspases may be implicated in the control of cell differentiation is also supported by studies using caspase-deficient mice. For example, mice deficient in caspase 8, the caspase activated following stimulation of death receptors, display unregulated erythropoiesis and lack of proper heart muscle development (37).

The mechanisms that prevent a cell with activated caspases from undergoing apoptosis have not yet been identified. One possibility is that some caspase substrates generate an antiapoptotic signal when cleaved. In the present study we have found that RasGAP, a regulator of Ras- and Rho-dependent pathways (4, 19), is a caspase substrate. RasGAP caspase cleavage fragments generate antiapoptotic signals in cells with low levels of caspase activation but potentiate the apoptotic response when caspase activity increases. RasGAP is the first example of a caspase substrate that, when cleaved, negatively or positively regulates apoptosis in a manner that is dependent on the extent of caspase activation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and transfection.

HeLa cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 containing 10% newborn calf serum (GIBCO/BRL) at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine (GIBCO/BRL) as described previously (34). Briefly, 2 × 106 cells, plated the previous day in 10-cm-diameter petri dishes, were incubated for 5 h with a DNA (6 μg)–Lipofectamine (10 μl) mixture in 5 ml of RPMI 1640 at 37°C in 5% CO2. The total amount of DNA was kept constant using empty vectors when required. Five milliliters of RPMI 1640–20% newborn calf serum was then added, and the cells were analyzed 16 to 20 h later. When cisplatin was used, it was added at the time serum was added back to the transfected cells. In many experiments, several plasmids were transfected together. To determine the cotransfection efficiency, HeLa cells were transfected with 1 μg of a green fluorescent protein (GFP)-encoding plasmid, 1 μg of a kinase-dead MEKK1 875-1493 mutant, and 4 μg of pcDNA3. Cells were then fixed, and the presence of MEKK1 was detected by immunocytochemistry. The proportion of cells expressing both GFP and MEKK1 was found to be about 80%. Thus, this transfection procedure ensures that a majority of the cells are cotransfected.

Chemicals and antibodies.

Purified caspase 3 was from Pharmingen. Cisplatin was from Sigma (catalog no. A7906). The z-VAD caspase inhibitor was from Enzyme System Products (catalog no. FK-009). The antibody specific for poly(ADP)-ribose polymerase (PARP) was from New England Biolabs (catalog no. 9542). The antiserum specific for the carboxy-terminal part of RasGAP (directed against sequence positions 1034 to 1047) was from Alexis Biochemicals (catalog no. 210-781). The antiserum against the SH2-SH3-SH2 domains of RasGAP has been described previously (29). Antibodies specifically recognizing the active forms of caspase 3 and caspase 9 were from R&D Systems (catalog no. AF835) and New England Biolabs (catalog no. 9502), respectively. The monoclonal antibody specific for the hemagglutinin (HA) tag was purchased as ascites from BabCo (catalog no. MMS-101R). This antibody was adsorbed on HeLa cell lysates to decrease nonspecific binding as follows. HeLa cells from two 15-cm-diameter petri dishes with confluent growth were lysed in 800 μl of monoQ-c (70 mM β-glycerophosphate, 0.5% Triton X-100, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 100 μM Na3VO4, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 20 μg of aprotinin per ml). The proteins of the cell lysate were coupled to 1.2 ml (dry bed volume) of Affi-Gel 10 beads and Affi-Gel 15 beads (Bio-Rad catalog no. 153-6099 and 153-6051, respectively) as per the manufacturer's protocol. The two sets of beads were loaded in different columns (Poly-Prep columns from Bio-Rad; catalog no. 731-1550). The Affi-Gel 10 column was placed above the Affi-Gel 15 column, and 500 μl of the anti-HA ascites fluid was loaded over the Affi-Gel 10 bed volume. The columns were eluted in a stepwise manner with 500 μl of TBS (1.5 mM NaCl, 2 mM Tris base [pH 7.4])–0.1% Tween every 10 min. The fractions corresponding to the flowthrough were then collected and pooled. The samples were aliquoted, complemented with 0.05% azide (final concentration), and stored at −80°C until used.

Plasmids.

The extension dn3 in the name of a plasmid indicates that the backbone plasmid is the expression vector pcDNA3 (Invitrogen). Plasmid h-RasGAP.dn3 encodes the human RasGAP protein (h indicates the human origin) (33). Plasmid HA-GAP.dn3 encodes the full-length human RasGAP protein bearing an HA tag (MGYPYDVPDYAS) at the amino-terminal end. The RasGAP mutants with an aspartate-to-alanine substitution at position 455 (plasmid HA-D455A.dn3), position 157 (plasmid HA-D157A.dn3), or position 160 (plasmid HA-D160A.dn3) were generated by PCR mutagenesis, as described previously (22), using HA-GAP.dn3 as the template. N-D157A.dn3 encodes the uncleavable form of fragment N (i.e., the form bearing the D157→A mutation). HA-GAPN.dn3, HA-N1.dn3, and HA-N2.dn3 encode the HA-tagged (at the N terminus) versions of RasGAP fragments from positions 1 to 455, 1 to 157, and 158 to 455, respectively. GFP-GAPC is a fusion protein between GFP and the fragment from position 456 to 1047 of RasGAP bearing an HA tag at the carboxy-terminal end. It was not possible to express the unfused RasGAP 456-1047 fragment in cells due to the inability of the corresponding RNA to be translated (data not shown). Plasmid pEGFP-C1, encoding GFP protein, was from Clontech. Plasmids V12Ras.cmv and N17Ras.cmv are pCMV5 plasmids encoding the constitutively active G12→V mutant Ras protein and the S17→N dominant negative mutant Ras protein, respectively. All of the constructs containing PCR inserts have been sequenced to verify that no PCR errors occurred.

Western blotting.

Cells were lysed in monoQ-c buffer as described above. Western blotting was performed as described previously (31). The enhanced chemiluminescence reagent was prepared by mixing 1 volume of solution 1 (2.5 mM Luminol [Sigma catalog no. A8511], 0.4 mM p-coumaric acid [Sigma catalog no. C9008], 100 mM Tris [pH 8.5]) and 1 volume of solution 2 (0.02% H2O2, 100 mM Tris [pH 8.5]). Quantitation was performed using a Bio-Rad Personal Imager apparatus.

In vitro translation.

In vitro translation was performed using the TNT quick coupled transcription-translation system (Promega) as per the manufacturer's protocol.

In vitro caspase 3 cleavage assay.

Five microliters of in vitro-translated 35S-labeled RasGAP proteins (see above) was incubated with the indicated amounts of purified caspase 3 for 1 to 2 h at 37°C. The reaction volume was adjusted to 20 μl with 50 mM Tris–1 mM EDTA–10 mM EGTA.

Apoptosis, cell rounding, and detachment measurements.

Apoptosis was determined by scoring the number of transfected cells (as assessed by the expression of GFP) displaying pycnotic nuclei. Nuclei were labeled with Hoechst 33342 (10 μl of a 10-mg/ml solution in water into 10 ml of culture medium). Cell rounding was assessed by determining the number of transfected cells that were round (under control conditions, HeLa cells have a spread appearance). The number of detached cells was determined after centrifugation of the cell culture medium and resuspension in 100 to 300 μl of medium. For each condition, at least 200 transfected cells (from at least five different fields) were analyzed blindly (without knowledge of sample identity) using an inverted Leica DM IRB microscope equipped with fluorescence and transmitted light optics. Assessment of apoptosis and cell rounding was performed 1 day after the transfection of the cells.

Statistics.

Statistical analysis was performed with t tests using Excel 97 SR-1 software (Microsoft). In Fig. 5B, 6, and 7, error bars that are not visible are within the width of the symbols.

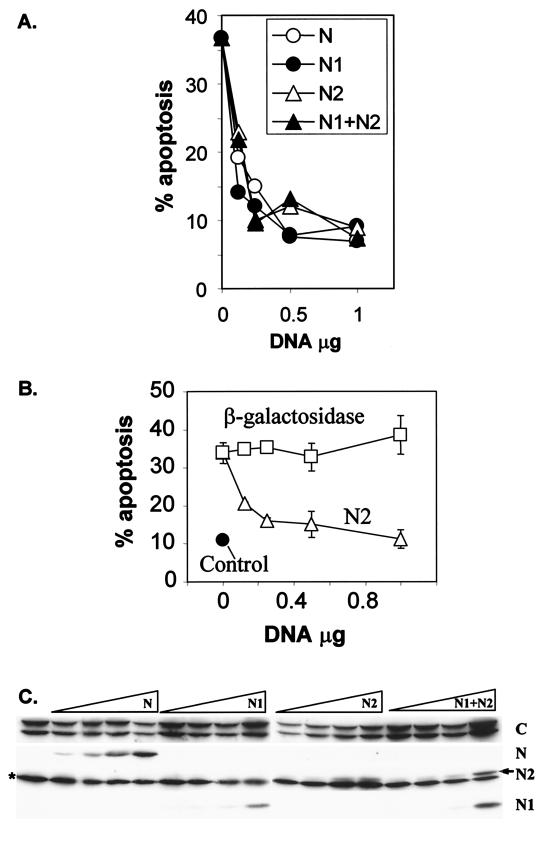

FIG. 5.

The N-terminal fragments inhibit fragment C-induced apoptosis. HeLa cells were transfected with 4 μg of the plasmid encoding HA-tagged fragment C with or without increasing quantities (0, 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, and 1 μg) of plasmids encoding the indicated N-terminal fragments (N, N1, N2, and N1 plus N2, all tagged with HA) or a plasmid encoding β-galactosidase as a specificity control. The closed circle in panel B corresponds to cells transfected only with GFP. The extent of apoptosis was then scored (A and B), and the expression levels of the HA-tagged RasGAP fragments were determined by Western blotting using an anti-HA antibody (C). Transfection of HeLa cells with fragment C resulted in the appearance of two closely migrating bands. The asterisk indicates a nonspecific immunoreactive band that migrates close to fragment N2 (arrow). The experiment depicted in panel B is representative of two independent experiments performed in duplicate. The other experiments are each representative of four independent experiments.

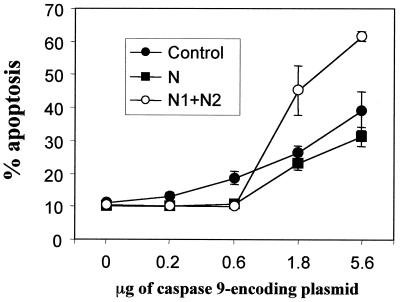

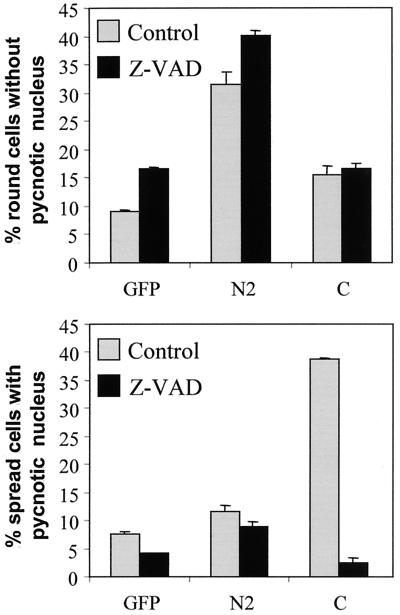

FIG. 6.

The N-terminal RasGAP fragments differentially regulate apoptosis in a manner that is dependent on the levels of caspase 9 expression. HeLa cells were transfected with 1 μg of empty vector (pcDNA3), with plasmids encoding fragments N1 and N2 (HA-N1.dn3 and HA-N2.dn3, 1 μg each), or with 1 μg of a plasmid encoding an uncleavable form of fragment N (N-D157A.dn3) in the presence of increasing amounts of a plasmid encoding caspase 9. The number of transfected cells undergoing apoptosis was then scored (mean ± standard deviation from triplicate determinations). This figure is representative of two different experiments. Fragments N, N1, and N2 inhibited apoptosis induced by low levels of caspase 9, but only fragments N1 and N2 potentiated apoptosis induced by high caspase 9 levels.

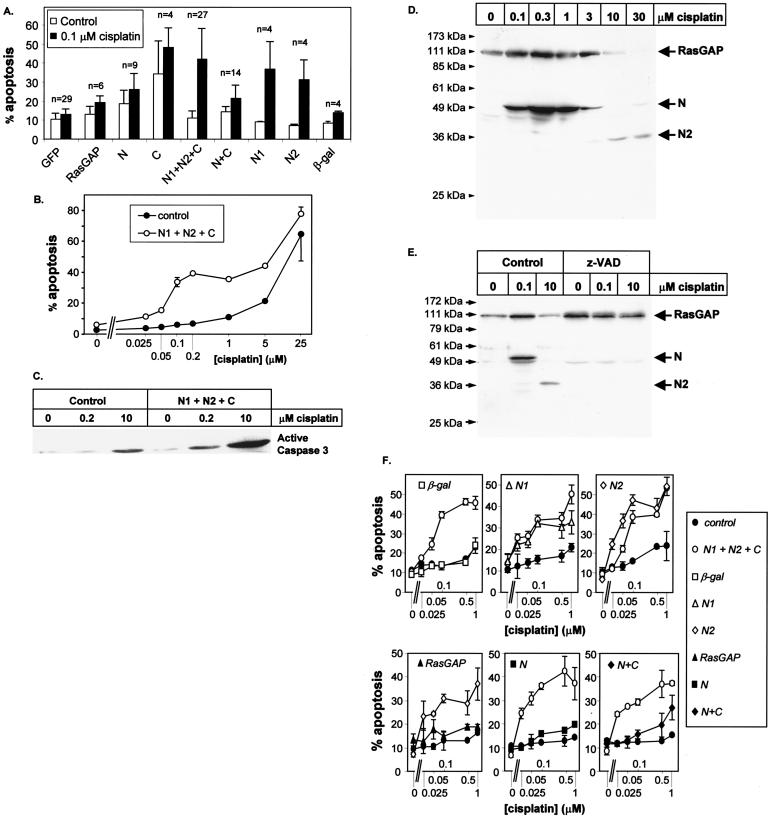

FIG. 7.

Fragments N1 and N2 sensitize cells towards DNA damage-induced apoptosis. (A) HeLa cells were transfected as described for Fig. 2 with plasmids encoding HA-tagged forms of RasGAP or the indicated HA-tagged RasGAP caspase cleavage fragments. The amounts of plasmid used for the transfection were adapted so as to result in similar protein expression levels. The cells were treated or not with 0.1 μM cisplatin for 16 to 18 h. The number of transfected cells undergoing apoptosis was then scored. The results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation from the indicated number of experiments. (B) HeLa cells were transfected with 1 μg of a GFP-expressing plasmid with or without plasmids encoding fragment N1 and N2 (1 μg each) and C (4 μg) in the presence of increasing concentrations of cisplatin. The number of transfected cells undergoing apoptosis was then scored and expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean from duplicate determinations. This figure is a representative example of eight different experiments. (C) HeLa cells were transfected as for panel B. The cells were then incubated with the indicated cisplatin concentrations for 18 h and lysed, and the presence of activated caspase 3 in the cell lysates was detected by Western blot analysis using an antibody specifically recognizing the active form of the caspase. (D) HeLa cells were incubated with the indicated cisplatin concentrations for 18 h. The cells were then lysed, and the presence of RasGAP, fragment N, and fragment N2 was identified by Western blot analysis using an antibody directed at the SH2-SH3-SH2 domains of RasGAP. (E) HeLa cells were incubated with the indicated cisplatin concentrations for 18 h in the absence (control) or in the presence of 30 μM caspase inhibitor z-VAD. The cells were then processed as described for panel D. Inhibition of caspases blocked the appearance of both fragment N and fragment N2. (F) HeLa cells were transfected with 1 μg of a GFP-expressing plasmid with or without the indicated combinations of plasmids (4 μg of the fragment C-encoding plasmid; 1 μg of the others) in the presence of increasing concentrations of cisplatin. The number of transfected cells undergoing apoptosis was then scored. β-gal, β-galactosidase.

RESULTS

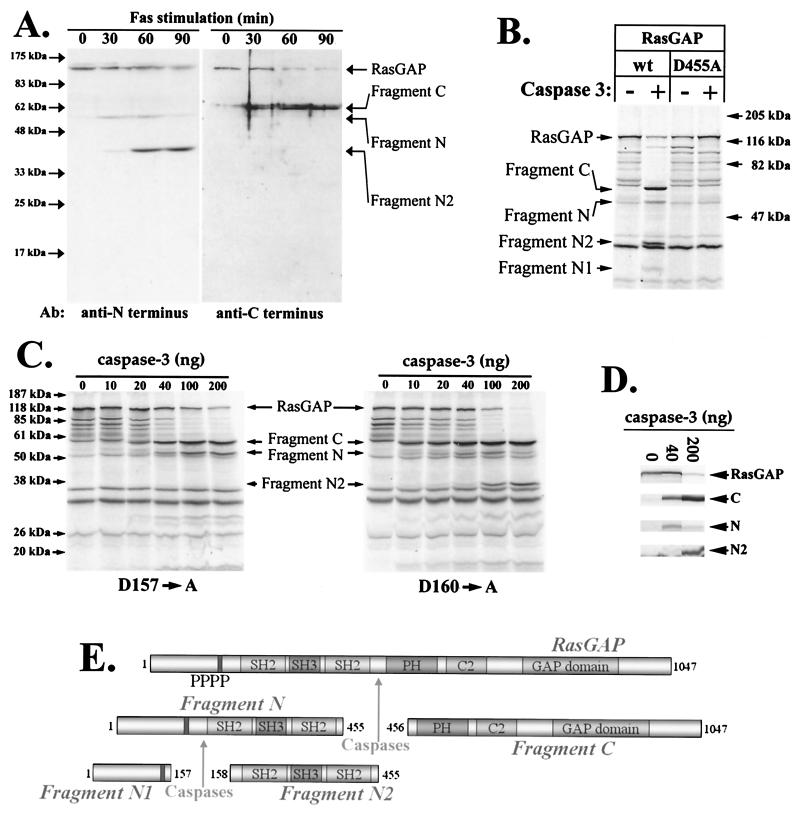

Identification of the caspase cleavage site in RasGAP.

We have recently shown that RasGAP is cleaved in apoptotic Jurkat cells (33). To determine more precisely the kinetics of the RasGAP cleavage, Jurkat cells stimulated with anti-Fas immunoglobulin M antibodies for various periods of time were lysed and the lysates were analyzed by Western blotting using N- and C-terminal RasGAP-specific antibodies. Figure 1A shows that RasGAP is sequentially cleaved during the apoptotic process. A first cleavage event generates a C-terminal fragment of about 64 kDa (fragment C) and an N-terminal fragment of about 56 kDa (fragment N). Fragment N is then further cleaved into additional fragments. The N terminus-specific antibody used here recognizes the SH2-SH3-SH2 domain of RasGAP, and thus only one fragment (fragment N2) resulting from the cleavage of fragment N is detected on the Western blot (see below).

FIG. 1.

Characterization of the RasGAP cleavage sites. (A) Jurkat cells were stimulated with anti-Fas antibodies for the indicated periods of time. Cell lysates (200 μg) were analyzed by Western blotting using antibodies specific for either the amino or the carboxy terminus of RasGAP. (B) In vitro-translated RasGAP (wild type [wt] or D455→A mutant, generated from plasmids HA-GAP.dn3 and HA-D455A.dn3, respectively) was incubated or not with 200 ng of purified caspase 3 for 1 h at 37°C. The reaction mixture was subjected to 10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The gel was then dried and autoradiographed. (C) In vitro-translated RasGAP mutants (D157→A and D160→A, generated from plasmids HA-D157A.dn3 and HA-D160.dn3, respectively) were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with the indicated quantities of purified caspase 3. The samples were then processed as described for panel B. (D) In vitro-translated wild-type RasGAP (produced as described for panel B) was incubated with the indicated amounts of caspase 3 and further processed as described for panel B. (E) Schematic representation of RasGAP cleavage by caspases. SH, Src homology domain; PH, pleckstrin homology domain; PPPP, proline-rich region; C2, calcium-dependent phospholipid binding domain; GAP domain, GTPase-activating domain.

The cleavage of RasGAP by purified caspase 3 generated the same fragments as observed in apoptotic Jurkat cells (plus fragment N1, which was not recognized by the antibodies used for the Western blots presented in Fig. 1A) (Fig. 1B). Similarly, lysates from apoptotic Jurkat cells, but not from control cells, were able to cleave in vitro-translated RasGAP into the same fragments generated by purified caspase 3 (data not shown). The ability of the lysate prepared from apoptotic Jurkat cells to cleave in vitro-translated RasGAP was abrogated by the caspase 3-specific inhibitor DEVD-CHO (data not shown). These data indicate that RasGAP is cleaved by caspase 3 or caspase 3-like enzymes during the apoptotic response.

Based on the sizes of fragments C and N, we estimated that a cleavage site should be localized slightly before the middle of the protein. In this region lies a caspase 3 consensus cleavage site (DTVD[455]G). Indeed, mutation of aspartic acid 455 to an alanine residue abrogated the ability of caspase 3 to cleave RasGAP (Fig. 1B).

The sequence GTVDEGDSLDGPE of fragment N contains two putative caspase 3 recognition sites (aspartate residues 157 and 160, underlined) that potentially could be used to generate fragments N1 and N2. These sites were thus individually mutated into alanine residues, and the resulting mutants were tested for their ability to be cleaved by purified caspase 3. Both mutants were cleaved into fragment N and fragment C, but further cleavage of fragment N was not observed in the case of the mutant lacking the aspartate at position 157 (Fig. 1C). This demonstrates that the second caspase cleavage site of RasGAP corresponds to the DEGD[157]S sequence.

Cleavage at position 157 occurs at a much higher caspase concentration than cleavage at position 455. For example, at a caspase 3 concentration of 40 ng/20 μl, RasGAP is cleaved into fragment N and fragment C but fragment N2 is not generated. Only at higher caspase 3 concentrations is fragment N2 produced (Fig. 1D; see also Fig. 1C).

Interestingly, generation of fragments N1 and N2 did not occur when cleavage at position 455 was abrogated (Fig. 1B). Thus, the cleavage event at the DEGD[157]S site occurs only after RasGAP has been cleaved at the DTVD[455] site. The kinetics of RasGAP cleavage in apoptotic Jurkat cells also supports this fact (see also Fig. 7D). Indeed, were RasGAP cleaved at position 157 before or at the same time as at position 455, fragments of about 100 and 20 kDa should be detected (that is, fragments generated by cleavage at position 157 only). However, this is not the case, suggesting that the first cleavage event induces structural modifications that allow the second cleavage event to take place. A schematic representation of how RasGAP is cleaved by caspases is shown in Fig. 1E.

The RasGAP caspase cleavage fragments fulfill different functions in the apoptotic process.

Next, we assessed the roles of the different RasGAP fragments generated by caspases in the regulation of apoptosis. Since RasGAP has the potential to modulate cell adhesion (20), we were concerned about the possibility that RasGAP fragments could induce apoptosis as a consequence of cell rounding and detachment (anoikis). We assessed the ability of each of the RasGAP fragments to induce apoptosis and cell rounding in HeLa cells, and we determined whether or not these two features were correlated (Fig. 2).

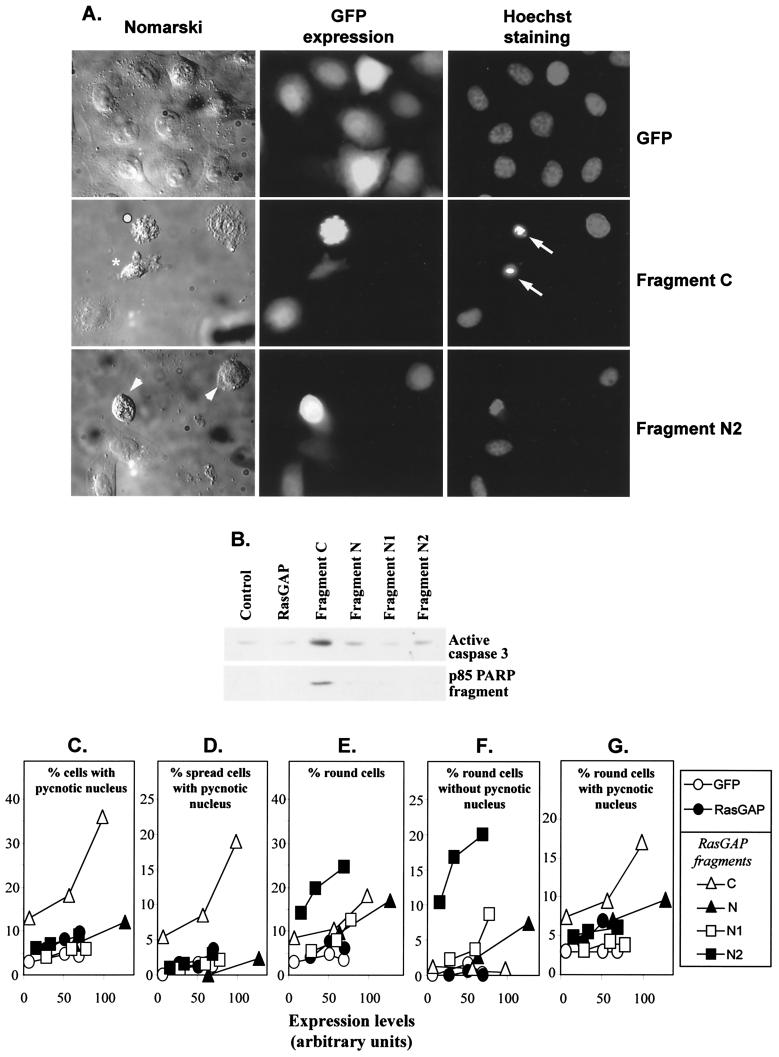

FIG. 2.

The C-terminal and N-terminal fragments of RasGAP differentially regulate apoptosis and cell shape. HeLa cells were transfected with increasing amounts of plasmids encoding HA-tagged forms of wild-type RasGAP (using plasmid HA-GAP.dn3) or of the indicated RasGAP caspase cleavage fragments (using plasmids GFP-GAPC, HA-GAPN.dn3, HA-N1.dn3, and HA-N2.dn3) together with 1 μg of a plasmid encoding GFP (to visualize the transfected cells). (A) Nomarski and fluorescent images of control cells or cells expressing fragment C or fragment N2. Arrows show cells with pycnotic (condensed) nuclei, and arrowheads show cells that are rounding up. Pycnotic nuclei were commonly observed in spread cells expressing fragment C (e.g., the cell labeled with an asterisk). These cells eventually round up (e.g., the cell labeled with a white dot) and detach. Fragment N2 induced cell rounding with no associated nuclear condensation or fragmentation. (B to G) One day after transfection, the number of fluorescent cells that were round and/or that displayed pycnotic nuclei was determined. In panels C to G, these parameters are expressed as a function of transfected protein levels (as determined by quantitative Western blot analysis using an anti-HA-specific antibody). In panel B, cell lysates corresponding to conditions leading to similar protein expression levels (as determined from panels C to G) were analyzed by Western blotting using an antibody that specifically recognizes the active form of caspase 3 or an antibody that recognizes the caspase-generated p85 fragment of PARP.

Fragment C, but not full-length RasGAP or the other fragments, induced a strong apoptotic response in HeLa cells as assessed by its ability to induce the appearance of pycnotic nuclei (Fig. 2A and C), activation of caspase 3, and cleavage of PARP (a classical caspase 3 substrate) into a 85-kDa fragment (Fig. 2B). Fragment C did not induce apoptosis as a consequence of cell detachment, because (i) many (more than half) of the apoptotic cells expressing fragment C were still adherent (compare Fig. 2C with Fig. 2D and G) and (ii) in general it was not possible to detect a normal nucleus among the round cells expressing fragment C (Fig. 2F). These data indicate that fragment C induces caspase activation, which results in an apoptotic response that eventually leads to cell rounding and detachment.

The N-terminal fragments of RasGAP promoted cell rounding (particularly so for fragment N2) (Fig. 2A). In contrast to the case for fragment C, cell rounding induced by fragment N2 was not the end result of apoptosis, because there were very few pycnotic nuclei observed in spread cells expressing fragment N2 (Fig. 2A and D) and most of the round cells expressing fragment N2 had a normal nucleus (compare Fig. 2E with Fig. 2F and G). Also, the rounding process induced by fragment N2 was much more regular and efficient than that in cells expressing fragment C (compare the Nomarski images in Fig. 2A).

While the N-terminal fragments of RasGAP did not induce a strong apoptotic response in spread or round adherent HeLa cells, it was conceivable that they could promote apoptosis as a result of cell detachment (anoikis). Thus, we determined whether the fragment that induced the strongest cell rounding response could promote cell detachment as well. Figure 3 shows that while fragment N2 induced a four- to fivefold increase in the number of round cells, it did not stimulate cell detachment. Thus, the N-terminal RasGAP fragments promote cell rounding, but this does not result in cell detachment and anoikis.

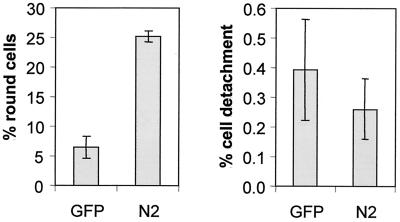

FIG. 3.

Fragment N2 does not stimulate cell detachment. HeLa cells were transfected with 2 μg of an empty vector (pcDNA3) or with 2 μg of a plasmid encoding the HA-tagged form of fragment N2 (plasmid HA-N2.dn3) together with 2 μg of a plasmid encoding GFP (to monitor transfected cells). The percentage of round cells and the percentage of detached cells among GFP-positive cells were then scored. These results are the pooled means ± standard deviations from four independent experiments.

To assess if the effects of fragment C and fragment N2 were dependent on caspase activity, cells transfected with plasmids encoding these fragments were incubated or not with z-VAD, a general caspase inhibitor. Figure 4 shows that while the apoptosis-promoting activity of fragment C was totally blocked by z-VAD, the ability of fragment N2 to promote cell rounding was not affected by the caspase inhibitor. These data confirm that fragment C induces apoptosis in a caspase-dependent manner, while fragment N2 promotes cell rounding in a caspase-independent manner.

FIG. 4.

Fragment C induces the appearance of pycnotic nuclei in a caspase-dependent manner. HeLa cells were transfected with plasmids encoding HA-tagged forms of fragment N2 or fragment C (plasmids HA-N2.dn3 and GFP-GAPC, respectively) together with 1 μg of a plasmid encoding GFP (to monitor transfected cells) in the presence or in the absence of 30 μM z-VAD. One day later, the percentage among transfected cells of round cells with a normal nucleus and the percentage of spread cells with a pycnotic nucleus were determined. These results correspond to the means ± standard errors of the means of duplicate values (this experiment was repeated four times with similar results).

The apoptosis-promoting ability of fragment C can be inhibited by the N-terminal fragments.

The effects of the different RasGAP caspase cleavage fragments expressed within the same cell were then determined. Strikingly, the combined expression of fragment C and fragment N or the combined expression of fragments C, N1, and N2 resulted in a weaker apoptosis activity than expression of fragment C alone (see Fig. 7A, open bars). Figure 5A shows that fragments N, N1, and N2 inhibited the apoptosis-inducing ability of fragment C in a dose-dependent manner without affecting the expression levels of fragment C (Fig. 5C). Inhibition of the proapoptotic ability of fragment C was not the result of a nonspecific inhibition resulting from the expression of any transfected gene, since increasing expression of β-galactosidase did not prevent fragment C-induced apoptosis (Fig. 5B). The levels of expression of each fragment were determined by quantitative Western blot analysis using an antibody specific for the HA tag born by each fragment (Fig. 5C). The N-terminal fragments inhibited the proapoptotic ability of fragment C at levels of expression that were much lower than those of fragment C. This indicates that the inhibition of the proapoptotic ability of fragment C by the N-terminal fragments does not occur as a result of stoichiometric interactions. Moreover, no coimmunoprecipitation of the N-terminal fragments with the C-terminal fragment could be detected (data not shown). These results suggest that the N-terminal RasGAP fragments indirectly block fragment C-induced apoptosis by activating antiapoptotic pathways.

Regulation of caspase 9-induced apoptosis by the RasGAP N-terminal fragments.

We next assessed whether the RasGAP N-terminal fragments were only counteracting the proapoptotic activity of fragment C or whether they had broader antiapoptotic functions. Therefore, we examined whether fragment N or fragments N1 and N2 could inhibit caspase 9-induced apoptosis. To prevent the processing of fragment N into fragments N1 and N2 that would occur in presence of caspase activity, we used an uncleavable form of fragment N (i.e., fragment N bearing the D157→A mutation). Figure 6 shows that HeLa cells transfected with a vector encoding caspase 9 underwent apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner. Fragment N or fragments N1 and N2 inhibited the apoptotic response induced by low levels of caspase 9. In contrast, fragments N1 and N2, but not fragment N, potentiated the apoptotic response induced by high levels of caspase 9. The ability of the N-terminal fragments to regulate caspase 9-induced apoptosis was not a consequence of a modulation of the expression of the caspase, since Western blot analysis revealed that the levels of caspase 9 were not affected by coexpressing the N-terminal fragments (data not shown). Our results indicate that the regulation of apoptosis by the N-terminal RasGAP fragments is a complex event modulated by the extent of caspase activity and by the cleavage of fragment N into fragments N1 and N2. The uncleaved fragment N inhibits apoptosis induced by low levels of caspases but does not potentiate apoptosis at higher levels of caspases. When fragment N is cleaved into fragments N1 and N2, apoptosis is still inhibited at low levels of caspases, but at higher levels of caspases, fragments N1 and N2 potentiate apoptosis.

The RasGAP caspase cleavage fragments potentiate cell death in genotoxin-treated cells.

The ability of the RasGAP cleavage fragments to inhibit cell death could be a mechanism to prevent inappropriate apoptosis in cells having activated low levels of caspases for reasons other than apoptosis. However, we hypothesized that in cells that have been damaged, RasGAP fragments may instead favor apoptosis. To test this hypothesis, we subjected cells coexpressing different RasGAP fragments to a low dose of the DNA-damaging drug cisplatin, which by itself only marginally induced apoptosis. In the absence of the drug, the combined expression of fragments N1, N2, and C did not induce apoptosis. However, in the presence of 0.1 μM cisplatin, these fragments generated a potent apoptotic response (Fig. 7A). To determine at what concentrations of cisplatin HeLa cells were rendered more sensitive to apoptosis by the RasGAP cleavage fragments, HeLa cells were transfected with or without fragments N1, N2, and C and were incubated with increasing concentrations of cisplatin. In the absence of RasGAP fragments, HeLa cells underwent apoptosis at cisplatin concentrations of 5 μM and higher (Fig. 7B). In the presence of the RasGAP fragments, a biphasic curve was obtained. In the first phase, apoptosis was detected at concentrations of cisplatin as low as 50 nM and reached a plateau between 100 nM and 5 μM cisplatin. In the second phase, starting at a cisplatin concentration of 5 μM, the percentage of cells with apoptosis increased again and paralleled the extent of apoptosis observed in the absence of the RasGAP fragments. Comparison of the curves obtained with or without the RasGAP fragments indicates that the presence of the RasGAP fragments rendered HeLa cells about 100 times more sensitive to cisplatin treatment. This effect was specific for the RasGAP fragments, since expression of β-galactosidase did not sensitize cells towards cisplatin (Fig. 7A and E). In cells transfected with control plasmids, only high cisplatin concentrations (10 μM) activated caspases as determined by the appearance of active caspase 3 (Fig. 7C). In contrast, in the presence of the RasGAP fragments (fragments C, N1, and N2), caspase activation was detected at cisplatin concentrations (0.2 μM) that alone did not stimulate apoptosis but that induced cell death when fragments C, N1, and N2 were expressed in cells. These results suggest that the RasGAP fragments generated when RasGAP is fully cleaved potentiate apoptosis by favoring the activation of caspases.

The extent of RasGAP cleavage in HeLa cells was a function of the cisplatin concentration. At low cisplatin concentrations (0.1 to 1 μM), RasGAP was cleaved at position 455 as demonstrated by the appearance of fragment N (Fig. 7D). This cleavage event could be totally blocked by the caspase inhibitor z-VAD (Fig. 7E), indicating that low levels of cisplatin already induce some caspase activity. At these cisplatin doses, however, the cells did not undergo apoptosis (Fig. 7B). At higher cisplatin concentrations that induced apoptosis (3 to 30 μM), fragment N was further cleaved at position 157 as shown by the appearance of fragment N2 (Fig. 7D). This cleavage event could also be totally blocked by z-VAD (Fig. 7E). These results demonstrate, therefore, that the first cleavage of RasGAP occurs at very low, barely detectable, levels of caspase activity (Fig. 7C) and is associated with cell survival. The second cleavage, generating fragments N1 and N2, occurs only when caspases are strongly activated and is associated with apoptosis.

We next determined the combinations of the RasGAP fragments that could sensitize HeLa cells towards cisplatin-induced apoptosis. Figure 7A and F show that fragment N1 alone or fragment N2 alone strongly sensitized HeLa cells towards cisplatin treatment. Fragment N did not sensitize HeLa cells towards apoptosis. The combination of fragment N and fragment C only mildly sensitized the cells towards cisplatin-induced apoptosis. This sensitization was much weaker than those observed in cells expressing either fragments N1, N2, and C or fragment N1 or N2 alone. Either fragment N1 or fragment N2 could sensitize the cells to cisplatin-induced apoptosis to the same extent as when fragments C, N1, and N2 were used together. The presence of the proapoptotic fragment C is thus not required for the sensitization process. Taken together, these results indicate that fragments N and C resulting from the first RasGAP cleavage event neither induce apoptosis nor sensitize cells towards DNA damage-induced apoptosis. In contrast, fragments resulting from the subsequent cleavage of RasGAP (fragments N1, N2, and C), while still not inducing apoptosis in control conditions, strongly sensitize cells towards DNA damage-induced apoptosis.

Ras activity requirement for the regulation of apoptosis by the RasGAP fragments.

RasGAP negatively regulates Ras by stimulating the intrinsic GTPase activity of Ras, but RasGAP can also participate positively in Ras signaling by as-yet-undefined mechanisms (21, 27). Thus, we determined whether Ras activity was required for the effects on apoptosis mediated by the different RasGAP fragments generated by caspase cleavage. For this purpose, a dominant negative Ras mutant (N17Ras) known to block the activation of the wild-type Ras protein was used. The N17Ras mutant was not able to inhibit fragment C-induced apoptosis (Fig. 8A). In contrast, the ability of fragment N or fragments N1 and N2 to block fragment C-induced apoptosis was totally reversed by N17Ras (Fig. 8A). N17Ras also completely blocked the ability of fragment N1 alone or fragment N2 alone to inhibit fragment C-induced apoptosis (data not shown). This indicates that either fragment N1 or fragment N2 inhibits apoptosis by stimulating the activation of Ras activity. In contrast, the ability of the N1 and N2 RasGAP fragments to potentiate cisplatin-induced apoptosis was not blocked by N17Ras (Fig. 8B), showing that Ras activity is not required for the proapoptotic ability of fragments N1 and N2.

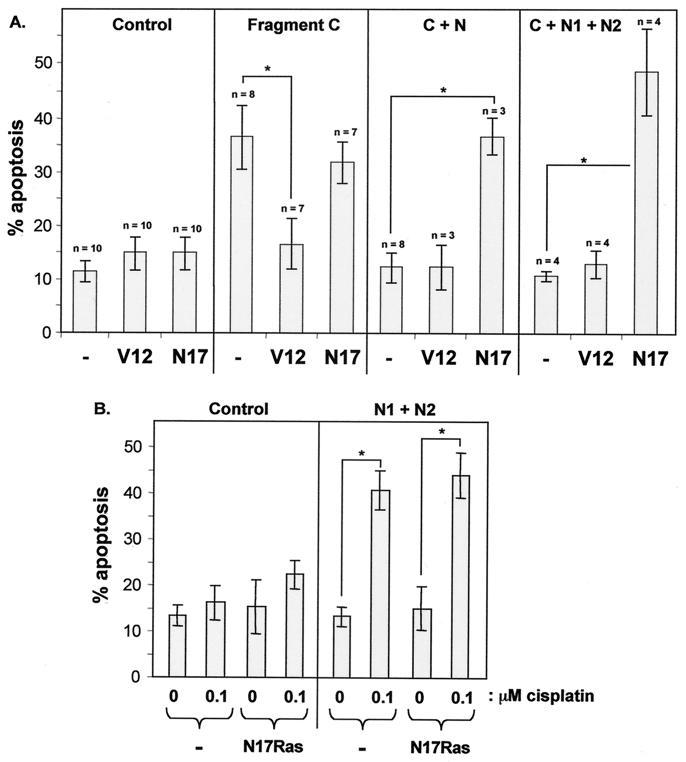

FIG. 8.

Role of Ras in the regulation of apoptosis by the RasGAP fragments. (A) HeLa cells were transfected with 1 μg of a GFP-expressing plasmid together with either empty pcDNA3 vector (control), 4 μg of the fragment C-encoding plasmid, 4 μg of the fragment C-encoding plasmid and 1 μg of the plasmid encoding fragment N, or 4 μg of the fragment C-encoding plasmid and 1 μg of plasmids encoding fragments N1 and N2 in the absence (−) or in the presence of 1 μg of a plasmid encoding the constitutively active V12Ras mutant (V12) or the dominant negative N17Ras mutant (N17). The number of transfected cells undergoing apoptosis was then scored and expressed as the mean ± standard deviation from the number of determinations indicated over the bars. The asterisk denotes a significant difference between the indicated conditions (P < 0.001). (B) HeLa cells were transfected with 1 μg of a GFP-expressing plasmid together with either empty pcDNA3 vector (control) or 1 μg of plasmids encoding fragments N1 and N2 in the absence (−) or in the presence of 1 μg of a plasmid encoding the N17Ras mutant. The cells were then stimulated or not with 0.1 μM cisplatin for 18 h. The number of transfected cells undergoing apoptosis was then scored and expressed as the mean ± standard deviation from four independent determinations. The asterisk denotes a significant difference between the indicated conditions (P < 0.001).

The C-terminal fragment of RasGAP contains the GAP activity towards Ras. If fragment C induces apoptosis by inhibiting Ras activity, it should be possible to reverse the apoptotic response by expressing a constitutively active form of Ras into cells. This is indeed what is observed. In the presence of the constitutively active V12Ras mutant, fragment C is no longer able to promote cell death (Fig. 8A). However, V12Ras was not able to inhibit the ability of the N-terminal RasGAP fragments to block fragment C-induced apoptosis, consistent with the notion that the N-terminal fragments of RasGAP block fragment C-induced apoptosis by activating Ras rather than by inactivating it. Expression of V12Ras or N17Ras into cells did not affect the expression levels of the RasGAP fragments as determined by quantitative Western blot analysis using an antibody directed at the HA tag born by all of the RasGAP constructs (data not shown). These results indicate that the effects seen in Fig. 8 are not due to modulation of the expression of the RasGAP fragments by the Ras mutants.

DISCUSSION

There are cases in which activation of the usually proapoptotic class II and III caspases (23) does not lead to a cell death response. Examples include the control of erythroblast differentiation by the caspase-mediated cleavage of GATA-1 (7) and activation and proliferation of T cells (1, 16). In these situations unknown mechanisms must be activated to prevent apoptosis following caspase stimulation. There are several candidate molecules that could be involved in such processes. Some of the members of the Bcl-2 family are well-known negative regulators of apoptosis. However, these proteins are thought to act upstream of caspase activation, in particular by preventing the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria and/or by inhibiting the activation of caspase 9 by Apaf-1. Thus, it is unlikely that they block apoptosis once caspases are activated. Caspase inhibitors such as IAPs (8, 17) could be induced, but this would result in a reduction of caspase activities, which is not observed in the cases mentioned. Our results showing that the caspase-generated N-terminal fragments of RasGAP can protect cells from apoptosis raise another provocative possibility: that the cleavage of some caspase substrates may induce antiapoptotic signals rather than proapoptotic signals.

RasGAP is a caspase substrate that is sequentially cleaved during apoptosis.

RasGAP is cleaved by caspases at two sites located at amino acids 157 and 455, generating three fragments: fragment N1 (amino acids 1 to 157), fragment N2 (amino acids 158 to 455), and fragment C (amino acids 456 to 1047) (Fig. 1E). Cleavage at position 157 can occur only if the protein is initially cleaved at position 455 (Fig. 1B), consistent with the observation that in cells subjected to apoptotic stimuli, cleavage at position 455 occurs much earlier than cleavage at position 157 (Fig. 1A). This suggests that the first cleavage event at position 455 induces structural modifications that allow the second cleavage at position 157 to take place. Such sequential cleavage events in protease substrates are not uncommon, with a classical example being the sequential cleavage of factor Va and factor VIIIa by protein C in the inhibition of the clot cascade (9, 30). The cleavage of RasGAP by caspases at its two sites is differentially regulated. Cleavage at position 455 is very efficient, occurring at caspase activities that are barely detectable and that do not induce apoptosis (Fig. 7). In contrast, the cleavage at position 157 occurs only when caspases are markedly activated and when cells undergo apoptosis (Fig. 7). Thus, cleavage at position 455 is not associated with apoptosis and, in fact, generates fragments that have strong antiapoptotic functions. In contrast, cleavage at position 157 is associated with apoptosis and generates fragments that potently potentiate the cell death response.

Regulation of apoptosis by the RasGAP caspase cleavage fragments.

When individually expressed in cells, fragment C and fragments N1 and N2 have different functions in the apoptotic process. Fragment C promotes apoptosis in a caspase-dependent manner, since this effect can be totally blocked by the z-VAD caspase inhibitor. Fragment C is thus an amplifier of the death response because it stimulates more caspase activity. There are several other examples of caspase substrates that when cleaved generate fragments that induce greater caspase activity. Examples include MEKK1 (5, 32) and protein kinase C theta (6).

In contrast to fragment C, the N-terminal fragments of RasGAP appear to regulate some of the cytoskeletal changes associated with apoptosis. Indeed, fragment N2, and fragments N and N1 to a lesser extent, promote cell rounding, a feature invariably associated with apoptosis. This effect was not blocked by caspase inhibitors, indicating that the ability of the N-terminal fragments of RasGAP to promote cell rounding is not a consequence of caspase activation. In some cell types, cell rounding and detachment can be a signal that leads to apoptosis (detachment-induced apoptosis is called anoikis) (11). However, the N-terminal fragments, while able to promote cell rounding, did not induce cell detachment (Fig. 3). Thus, it appears that cell rounding induced by the N-terminal RasGAP fragments is not a signal that promotes apoptosis. However, it is possible that at later stages of apoptosis, the ability of the N-terminal fragments to induce cell rounding facilitates elimination of apoptotic cells by phagocytosis.

The N-terminal RasGAP caspase cleavage fragments protect cells from apoptosis, provided that the cells are not damaged and/or that caspase activity is not too high.

When expressed together, the RasGAP cleavage fragments do not induce apoptosis. Since fragment C alone can generate a strong apoptotic response, this suggests that the N-terminal fragments have the capacity to inhibit cell death. This is indeed what is observed. The RasGAP N-terminal fragments, which are produced at the same time as fragment C, can totally block the proapoptotic ability of the latter (Fig. 6). Since there are no indications that the N-terminal fragments (fragment N2 in particular) are more prone to degradation than fragment C (see Fig. 1A for an example), the exact role of fragment C in the amplification of caspase activation in cells subjected to apoptotic stimuli remains to be determined.

The inhibitory effect of the N-terminal fragments is not restricted to fragment C-induced apoptosis, since they can also block caspase 9-induced apoptosis (providing that the levels of caspase 9 expression are not too high). The N-terminal fragments could thus inhibit apoptosis induced by different mechanisms.

The N-terminal RasGAP fragments generate their antiapoptotic response in a Ras-dependent manner (Fig. 8). Several pathways downstream of Ras have been shown to be antiapoptotic, including the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway (10) and the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway (35). Additional experiments using specific inhibitors will be required to determine if these pathways are used by the N-terminal RasGAP fragments to inhibit apoptosis.

Cleavage of fragment N into fragments N1 and N2 generates a potent sensitization signal towards DNA damage-induced apoptosis.

The ability of the N-terminal fragments to protect cells from apoptosis is observed only in cells displaying low caspase activity. In contrast, in cells with higher caspase activity, fragments N1 and N2, but not the parent molecule (fragment N), potentiated apoptosis (Fig. 6). Similarly, in lightly damaged cells (i.e., cells treated with low levels of genotoxins), fragments N1 and N2 render cells about 100-fold more sensitive towards apoptosis (Fig. 7). Under these conditions, the parent fragment N protein was not able to potentiate the apoptotic response. The proapoptotic function of fragments N1 and N2 did not depend on Ras activation (Fig. 8).

RasGAP signaling shifts from anti- to proapoptotic signaling as caspase activity increases: the apoptostat model.

Our data suggest that in situations where caspases are activated to low levels (possibly to fulfill functions other than apoptosis), partial cleavage of RasGAP into fragment N and fragment C generates a Ras-dependent antiapoptotic response that prevents the cells from engaging themselves in the apoptotic pathway (Fig. 9). In contrast, in situations where caspases are strongly activated, the RasGAP fragments are no longer able to protect cells from apoptosis. Moreover, in the presence of high enough caspase activity, RasGAP would be further cleaved, leading to the generation of fragments N1 and N2. These fragments strongly potentiate apoptosis in a Ras-independent manner (Fig. 9). RasGAP could thus be viewed as an “apoptostat” in the sense that it could allow the cell to determine when caspases have been mildly activated to fulfill functions other than apoptosis or when caspases are strongly activated to mediate apoptosis. The antiapoptotic mode involves the cleavage of RasGAP at position 455 that occurs at low caspase activity and that results in the generation of the antiapoptotic N-terminal fragment. The proapoptotic mode involves the cleavage of RasGAP at position 157 when caspase activity reaches a certain threshold, generating two potent proapoptotic fragments that actively participate in the apoptotic process.

FIG. 9.

Model of the roles of RasGAP caspase cleavage fragments in the regulation of apoptosis. See text for details.

What could be the mechanisms mediating the proapoptotic functions of the RasGAP cleavage fragments? Ras activation is not involved, since the dominant negative N17Ras mutant does not block the potentiation of apoptosis induced by fragments N1 and N2 (Fig. 8). The SH2 domains of RasGAP interact with RhoGAP, and thus RasGAP has the potential to regulate Rho activity (3, 15, 27). It has been shown recently that RhoB can inhibit NFκB (12). Since NFκB has been implicated in antiapoptotic signaling (2), its inhibition by Rho proteins could favor apoptosis. p62dok is another possible candidate protein that could mediate the proapoptotic signals generated by the RasGAP fragments. p62dok interacts with RasGAP via the SH2 domain borne by fragment N2 and has recently been shown to inhibit the activation of the ERK MAPK pathway in B cells (24, 36). As mentioned above, activation of the ERK MAPK pathway can lead to antiapoptotic signaling. Inhibition of the ERK MAPK pathway in a p62dok-dependent manner could thus be a mechanism employed by fragment N2 to favor apoptosis. Additional experiments are needed to resolve these issues.

There is no conserved sequence between N1 and N2. Thus, it is surprising that they both regulate apoptosis in similar manners. The only salient feature of N1 is a proline-rich region, while N2 bears one SH3 domain flanked by two SH2 domains, structures that are involved in protein-protein interactions (15). The fact that the N1 and N2 fragments regulate apoptosis similarly but independently of each other suggests that both fragments may interact with the same partner to relay their anti- or proapoptotic properties. Alternatively, the two fragments may regulate apoptosis by different mechanisms. These possibilities are currently being investigated.

Possible roles of the RasGAP cleavage fragments in nonapoptotic cells.

It appears that caspase activation occurs, and may even be required, during some differentiation processes (1, 7, 16). The function of RasGAP cleavage in these situations may be to protect cells from apoptosis that would normally occur after caspase activation. There is in fact strong evidence that RasGAP could generate antiapoptotic signals. Indeed, inhibition of RasGAP by microinjection of specific anti-RasGAP antibodies induces apoptosis in several tumor cell lines (18). Moreover, in mice lacking RasGAP, increased apoptosis is observed in the first branchial arch, in the hindbrain, in the optic stalk, and in the telencephalon (14). Since we have shown that the N-terminal fragments of RasGAP generated by caspase cleavage can protect cells from apoptosis, it remains to be determined whether the increased neuronal apoptosis observed in RasGAP knockout mice results from the absence of the full-length protein or the absence of the antiapoptotic fragments.

Studies using RasGAP knockout mice have also shown that RasGAP plays a role during development and differentiation. In the absence of RasGAP, the reorganization of yolk sac endothelial cells into a vascular network does not occur (14). Thus, RasGAP is required for the development of some embryonic structures. Whether cleavage of RasGAP is required for this function remains to be determined.

Conclusion.

Research on apoptosis performed during the previous decade has permitted the generation of a framework model in which caspases and their substrates play a central role in the induction of the cell death response. Recent evidence that caspases may be implicated in processes other than apoptosis and our findings that caspase substrates such as RasGAP can generate an antiapoptotic response indicate that the function of caspases and their substrates is more complex than originally thought.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Christelle Bonvin for expert technical assistance. We thank Fabio Martinon and Jürg Tschopp for the gift of the human caspase 9 expression plasmid. We thank Mathias Peter, Mark Epping-Jordan, Romano Regazzi, Jean-René Cardinaux, Peter Clarke, Peter Vollenweider, and Christophe Bonny for critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank the reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions.

This work is supported by grant 3100-055606 from the Swiss National Science Foundation and grants from the Botnar foundation (Lausanne, Switzerland).

REFERENCES

- 1.Alam A, Cohen L Y, Aouad S, Sekaly R P. Early activation of caspases during T lymphocyte stimulation results in selective substrate cleavage in nonapoptotic cells. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1879–1890. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.12.1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barkett M, Gilmore T D. Control of apoptosis by Rel/NF-kappaB transcription factors. Oncogene. 1999;18:6910–6924. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bar-Sagi D, Hall A. Ras and Rho GTPases: a family reunion. Cell. 2000;103:227–238. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00115-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell S L, Khosravi-Far R, Rossman K L, Clark G J, Der C J. Increasing complexity of Ras signaling. Oncogene. 1998;17:1395–1413. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cardone M, Salvesen G S, Widmann C, Johnson G L, Frisch S M. The regulation of anoikis: MEKK-1 activation requires cleavage by caspases. Cell. 1997;90:315–323. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80339-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Datta R, Kojima H, Yoshida K, Kufe D. Caspase-3-mediated cleavage of protein kinase C theta in induction of apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20317–20320. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Maria R, Zeuner A, Eramo A, Domenichelli C, Bonci D, Grignani F, Srinivasula S M, Alnemri E S, Testa U, Peschle C. Negative regulation of erythropoiesis by caspase-mediated cleavage of GATA-1. Nature. 1999;401:489–493. doi: 10.1038/46809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deveraux Q L, Reed T C. IAP family proteins—suppressors of apoptosis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:239–252. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fay P J, Smudzin T M, Walker F J. Activated protein C-catalyzed inactivation of human factor VIII and factor VIIIa. Identification of cleavage sites and correlation of proteolysis with cofactor activity. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:20139–20145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franke T F, Kaplan D R, Cantley L C. PI3K: downstream AKTion blocks apoptosis. Cell. 1997;88:435–437. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81883-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frisch S M, Francis H. Disruption of epithelial cell-matrix interactions induces apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1994;124:619–626. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.4.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fritz G, Kaina B. Ras-related GTPase RhoB represses NF-kappa B signaling. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:3115–3122. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005058200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghayur T, Banerjee S, Hugunin M, Butler D, Herzog L, Carter A, Quintal L, Sekut L, Talanian R, Paskind M, Wong W, Kamen R, Tracey D, Allen H. Caspase-1 processes IFN-gamma-inducing factor and regulates LPS-induced IFN-gamma production. Nature. 1997;386:619–623. doi: 10.1038/386619a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henkemeyer M, Rossi D J, Holmyard D P, Puri M C, Mbamalu G, Harpal K, Shih T S, Jacks T, Pawson T. Vascular system defects and neuronal apoptosis in mice lacking Ras GTPase-activating protein. Nature. 1995;377:695–701. doi: 10.1038/377695a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu K-Q, Settleman J. Tandem SH2 binding sites mediate the RasGAP-RhoGAP interaction: a conformational mechanism for SH3 domain regulation. EMBO J. 1997;16:473–483. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.3.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kennedy N J, Kataoka T, Tschopp J, Budd R C. Caspase activation is required for T cell proliferation. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1891–1896. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.12.1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LaCasse E C, Baird S, Korneluk R G, MacKenzie A E. The inhibitors of apoptosis (IAPs) and their emerging role in cancer. Oncogene. 1998;17:3247–3259. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leblanc V, Delumeau I, Tocque B. Ras-GTPase activating protein inhibition specifically induces apoptosis of tumour cells. Oncogene. 1999;18:4884–4889. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leblanc V, Tocque B, Delumeau I. Ras-GAP controls Rho-mediated cytoskeletal reorganization through its SH3 domain. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5567–5578. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.5567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGlade J, Brunkhorst B, Anderson D, Mbamalu G, Settleman J, Dedhar S, Rozakis-Adcock M, Chen L B, Pawson T. The N-terminal region of GAP regulates cytoskeletal structure and cell adhesion. EMBO J. 1993;12:3073–3081. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05976.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Medema R H, de Laat W L, Martin G A, McCormick F, Bos J L. GTPase-activating protein SH2-SH3 domains induce gene expression in a Ras-dependent fashion. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:3425–3430. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.8.3425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nelson R M, Long G L. A general method of site-specific mutagenesis using a modification of the Thermus aquaticus polymerase chain reaction. Anal Biochem. 1989;180:147–151. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90103-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nicholson D W. Caspase structure, proteolytic substrates, and function during apoptotic cell death. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:1028–1042. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tamir I, Stolpa J C, Helgason C D, Nakamura K, Bruhns P, Daeron M, Cambier J C. The RasGAP-binding protein p62dok is a mediator of inhibitory FcγRIIB signals in B cells. Immunity. 2000;12:347–358. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80187-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thornberry N, Lazebnik Y A. Caspases: enemies within. Science. 1998;281:1312–1316. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thornberry N A, Bull H G, Calaycay J R, Chapman K T, Howard A D, Kostura M J, Miller D K, Molineaux S M, Weidner J R, Aunins J, Elliston K O, Ayala J M, Casano F J, Chin J, Ding G J F, Egger L A, Gaffney E P, Limjuco G, Palyha O C, Raju S M, Rolando A M, Salley J P, Yamin T-T, Lee T D, Shively J E, MacCross M, Mumford R A, Schmidt J A, Tocci M J. A novel heterodimeric cysteine protease is required for interleukin-1β processing in monocytes. Nature. 1992;356:768–774. doi: 10.1038/356768a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tocque B, Delumeau I, Parker F, Maurier F, Multon M C, Schweighoffer F. Ras-GTPase activating protein (GAP): a putative effector for Ras. Cell Signal. 1997;9:153–158. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(96)00135-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toyoshima F, Moriguchi T, Nishida E. Fas induces cytoplasmic apoptotic responses and activation of the MKK7-JNK/SAPK and MKK6–p38 pathways independent of CPP32-like proteases. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:1005–1015. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.4.1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Valius M, Secrist J, Kazlauskas A. The GTPase-activating protein of ras suppresses platelet-derived growth factor β receptor signaling by silencing phospholipase c-γ1. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3058–3071. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.3058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van't Veer C, Golden N J, Kalafatis M, Mann K G. Inhibitory mechanism of the protein C pathway on tissue factor-induced thrombin generation. Synergistic effect in combination with tissue factor pathway inhibitor. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:7983–7994. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.12.7983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Widmann C, Dolci W, Thorens B. Agonist-induced internalization and recycling of the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor in transfected fibroblasts and in insulinomas. Biochem J. 1995;310:203–214. doi: 10.1042/bj3100203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Widmann C, Gerwins P, Lassignal Johnson N, Jarpe M B, Johnson G L. MEKK1, a substrate for DEVD-directed caspases, is involved in genotoxin-induced apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2416–2429. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.4.2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Widmann C, Gibson S, Johnson G L. Caspase-dependent cleavage of signaling proteins during apoptosis. A turn-off mechanism for anti-apoptotic signals. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7141–7147. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.12.7141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Widmann C, Lassignal Johnson N, Gardner A M, Smith R J, Johnson G L. Potentiation of apoptosis by low dose stress stimuli in cells expressing activated MEK kinase 1. Oncogene. 1997;15:2439–2447. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xia Z, Dickens M, Raingeaud J, Davis R J, Greenberg M E. Opposing effects of ERK and JNK-p38 MAP kinases on apoptosis. Science. 1995;270:1326–1331. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5240.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamanashi Y, Tamura T, Kanamori T, Yamane H, Nariuchi H, Yamamoto T, Baltimore D. Role of the rasGAP-associated docking protein p62(dok) in negative regulation of B cell receptor-mediated signaling. Genes Dev. 2000;14:11–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zheng T S, Hunot S, Kuida K, Flavell R A. Caspase knockouts: matters of life and death. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:1043–1053. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]