Abstract

The aim of the current research is to investigate the cerebral-protection of protodioscin on a transient cerebral ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) model and to explore its possible underlying mechanisms. The rats were preconditioned with protodioscin at the doses of 25 and 50 mg Kg−1 prior to surgery. Then the animals were subjected to right middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) using an intraluminal method by inserting a thread (90 min surgery). After the blood flow was restored in 24 h via withdrawing the thread, some representative indicators for the cerebral injury were evaluated by various methods including TTC-staining, TUNEL, immunohistochemistry, and western blotting. As compared with the operated rats without drug intervening, treatment with protodioscin apparently lowered the death rate and improved motor coordination abilities through reducing the deficit scores and cerebral infarct volume. What’s more, an apparent decrease in neuron apoptosis detected in hippocampus CA1 and cortex of the ipsilateral hemisphere might attribute to alleviate the increase in Caspase-3 and Bax/Bcl-2 ratio. Meanwhile, concentrations of several main pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6) in the serum were also significantly suppressed. Finally, the NF-κB and IκBa protein expressions in the cytoplasm of right injured brain were remarkably up-regulated, while NF-κB in nucleus was down-regulated. Therefore, these observed findings demonstrated that protodioscin appeared to reveal potential neuroprotection against the I/R injury due to its anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptosis properties. This therapeutic effect was probably mediated by the inactivation of NF-κB signal pathways.

Keywords: protodioscin, middle cerebral artery occlusion, Caspase-3, Bax/Bcl-2 ratio, pro-inflammatory cytokines, NF-κB

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

With the improvement of modern life standards, cerebrovascular diseases (CVD) are becoming prevalent in worldwide both in developed and developing countries, because of lacking effective and convenient medical treatment and health care system [1]. Stroke also called “Brain attack” (a kind of CVD) is primarily composed of following two forms: cerebral ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes [2].

Cerebral ischemic stroke caused by terminating the blood supply to either a part of the brain-(focal) or the whole brain (global) is a representative form accounting for 80% of stroke patients [3, 4]. This leads to insufficient supply of oxygen and glucose to the brain, and interrupts its normal physiological functions, such as the ability of speech, cognition, motor activities, and memory [5]. Consequently, patients suffer from severe physical problems and heavy economic burden. Due to these characteristics of high adult morbidity such as disability and mortality as well as recurrence rate [6], it becomes the second cause of death in the world [7]. In order to inhibit the further brain damage caused by ischemia immediate reperfusion is a vital remedial treatment and considered to be the best clinical approach [8]. Although the ischemic districts of the brain regain the supply of oxygen and nutrient, the secondary impairment, i.e. ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury, may occur after reperfusion causing brain tissue damage which is even worse or beyond the ischemia itself under certain conditions [9]. This cerebral injury is a complicated disorder, and several major mechanisms are involved such as inflammatory response, oxidative stress, apoptosis, excitotoxicity, ion imbalance, and acidotoxicity [10, 11]. Extensive scientific researches on this I/R have been carried out, however, this pathogenesis still remains obscure, and there are no generally recognized mechanisms reported until now.These aforementioned underlying mechanisms might cooperate synergistically to cause the final severe pathogenesis. Thanks to plentiful efforts made in the laboratory after numerous studies exploring the complex cellar pathways of I/R, various safe and effective therapeutic treatments have beenproposed [12]. Unfortunately, many of these strategies proved to be cerebroprotective in laboratory studies, but failed to exhibit promising efficacy in clinical trials [13]. Despite available medical agents of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) and tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) approved by American Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [14, 15], to our disappointment, the window of time is extremely short [16], and is inconvenient to treat I/R. Therefore, development of highly potential anti-ischemic stroke agents is still urgently warranted at present.

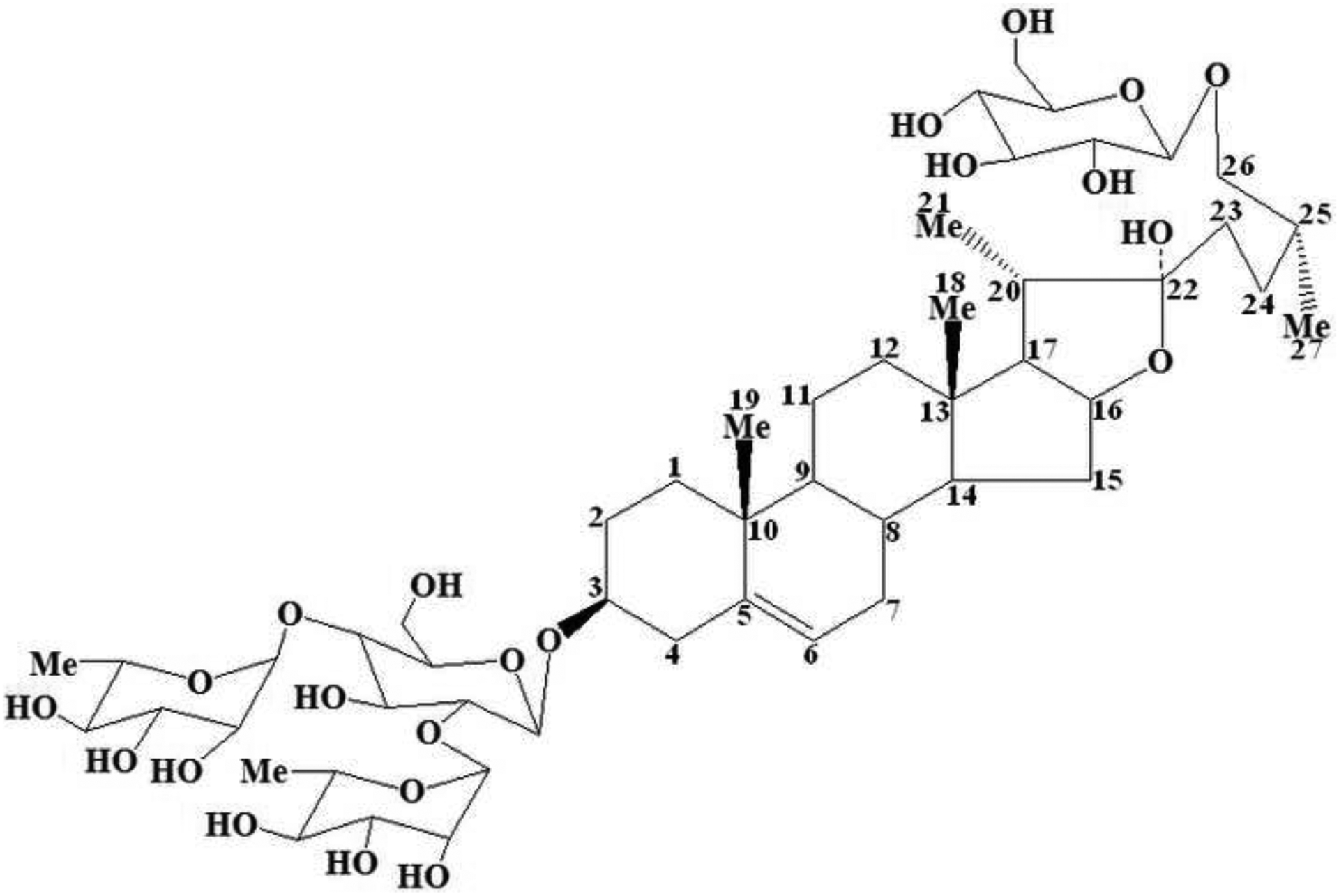

For many centuries, the Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) has been used to treat human diseases. To discover ideal sources for the treatment of I/R, much more attention has been paid to the active ingredients from TCM due to its weak toxicity and multiple target spots in recent years. After systematic and detailed pharmacological investigations, enough supporting data has been accumulated. Steroid saponins consisting of spirostanol and furostanol forms are bioactive compounds abundantly present in various plants [17]. Protodioscin, also written as 25(R)-26-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-furost-△5(6)-en-3β, 22α, 26-triol-3-O-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→4)-[α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→2)]-β-D-glucopyranoside, is a furostanol and naturally occurring steroid saponin present in the rhizome of Dioscorea zingiberensis C.H. Wright (D. zingiberensis) [18]. Its structure is shown in Fig. 1. According to the experiments performed by Gauthaman et al., Adaikan et al., and Gauthaman et al., it displays a broad range of charming bioactivities mainly including anti-cancer effects against cell lines of HL-60 cells, leukemia, and NCI’s [18]. However, to our best knowledge no report on the activities of protodioscin against I/R injury is available.

Figure 1:

The chemical structure of protodioscin with numbers marked on carbon atoms in aglycone which are consistent with the expression of the 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR in section 3.1.

Therefore, the purpose of the current study is to investigate whether or not protodioscin has the neuroprotective activity on cerebral I/R injury in rat. This model, i.e. transient focal middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO), is established to simulate the clinical symptoms of human cerebral ischemia-reperfusion. If it reveals satisfactorily therapeutic effect of protodioscin in rats, the possible underlying mechanisms are also assessed in this research.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Materials and chemicals

The dried rhizomes of D. zingiberensis were offered by Heng Xiang Biological Chemical CO., Ltd (Ankang, Shannxi) and kindly identified by Professor Wenzhe Liu (College of Life Science of Northwest University, Xi’an 710069, PRC). Its voucher specimen (NO.Drsr009) was deposited in the Key Laboratory of Resource Biology and Biotechnology in West China, Ministry of Education (Northwest University, PRC). The analytical reagents of methanol, ethanol, n-butanol, dichloromethane, and acetonitrile were purchased from Hongyan Chemical Reagent Factory (Tianjing, PRC). The distilled water (18 MΩ cm−1) was obtained by a Millipore Milli-Q water system in our laboratory (Milford, MA, USA).

The nimodipine pills (140851, 98% purity) and TTC reagent (1014795, 99% purity), also named 2,3,5-Triphenyltetrazolium Chloride, were supplied by Yabao Pharmaceutical Group CO., Ltd (Shanxi, PRC) and Xiya Reagent (Chengdu, PRC), respectively. The inflammatory factor ELISA kits of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 were all obtained from Roche Diagnostics (Germany). The primary anti-bodies (rabbit anti-rat) of Caspase-3, Bcl-2, Bax, NF-κB and IκBa were provided by the Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, PRC), while other anti-bodies (including secondary ones), TUNEL, DAB, and BCA kits by Wuhan Boster Biological Technology Co., LTD (Hubei, PRC). All other experimental materials were of analytical grade.

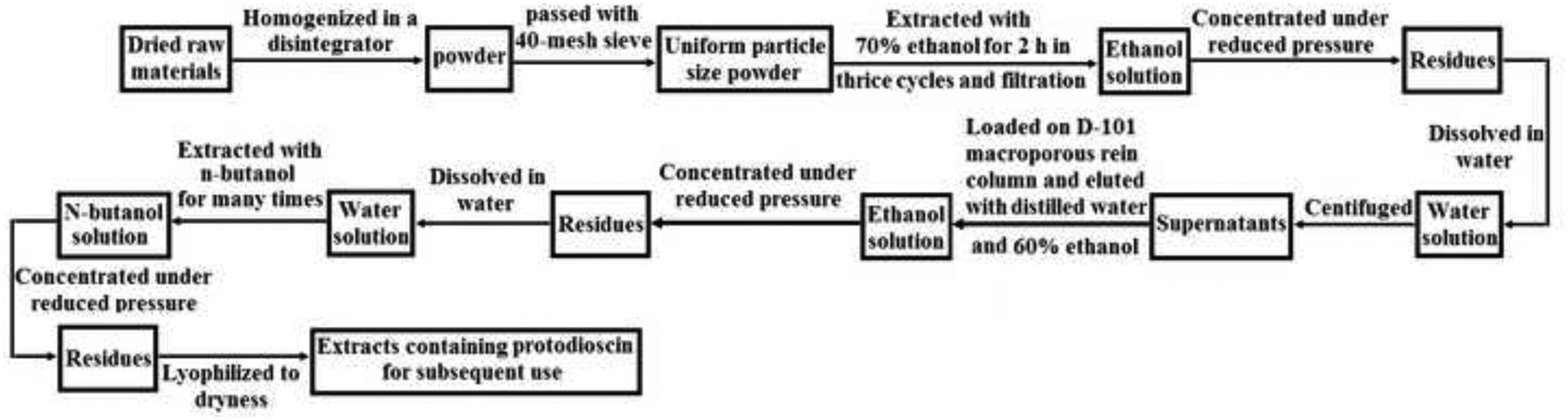

2.2. Preparation of protodioscin

The dried raw rhizomes of D. zingiberensis were cut into small pieces and homogenized in a speed disintegrator. The fine powder obtained after passing through a 40-mesh sieve was extracted with 70% ethanol (M/V=10, i.e. the ratio of mass and volume equals 10) under reflux for 2 h in thrice cycles. The collected solution was pooled and concentrated to a proper volume under reduced pressure and vacuum in a rotary evaporator. The obtained residues were redissolved in 20-fold volume of distilled water under continuous stirring, and centrifuged at 4000 rpm for15 min to remove lipophilic constituents. The supernatants were combined and loaded on a D-101 macroporous resin column (0.15 m × 1.0 m, 5.0 Kg macroporous resin), and then eluted with distilled water and 60% ethanol in sequence. The accumulated 60% ethanol eluent was concentrated to an appropriate volume and continuously extracted with 2-fold volume of n-butanol at least for six repetitions until no steroid saponins were detected on Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC). The combined n-butanol extracts were concentrated to dryness and eluted through a silica gel column (100–160 mesh) under a gradient mode with the lower layer of dichloromethane-methanol-water at various ratios from 12:3:1 to 6:3:1 (v/v/v, reduction of dichloromethane one ratio step-by-step), sequentially. This 8:3:1 fractions were collected according to the Rf value in the range of 0.2~0.5 on TLC, concentrated to residues, and then further chromatographed over the silica gel column (200–300 mesh). After loading sample, this column was eluted again with the above-mentioned solvent system at the ratio of 8:3:1. The eluate was also gathered based on the Rf value (0.2~0.5) on TLC and concentrated to dryness. After that, the remaining residues were transferred to the semi-preparative HPLC DAC-HB50 C18 column (450 mm×50 mm, 10 μm) for further isolation and purification. According to the chromatogram recorded in ELSD (Evaporative Light Scattering Detector, Alltech 800), the fractions from the column was manually collected during 50–78 min in the isocratic elution mode with the mobile phase composed of acetonitrile-water (28:72, v/v) at a flow rate of 50 mL min−1. The pooled eluate was concentrated under reduced pressure and lyophilized to obtain white powder of pure protodioscin. The structure of this compound was determined by combined spectroscopy methods of MS and NMR. After analysis, protodioscin was stored in a 4°C refrigerator for subsequent use.

2.3. Animals

The healthy male Sprague-Dawley rats (weighting 250~280 g, aged 8~10 weeks) supplied from the Experimental Animal Center of Xi’an Jiaotong University were used in this research. They were maintained in cages (5 rats in each cage) at constant temperature of 22 ± 1°C and 45–55% relative humidity with 12 h light/12 h dark cycles in our air-conditioned SPF grade laboratory. These animals were acclimatized the environment for at least one week before performing the experiments and allowed free access to rodent chow diets and purified water ad libitum. The standard food but not water was deprived 12 h prior to the surgery. The animal experimental schemes were strictly in accordance with the protocols and guidelines approved by the Animal Experimental Committee of Xi’an Jiaotong University (NO. XAJTU 2014–03). The animal care and use were executed and consistent with the local Animal Ethical Committee (2012, NO. 3245/2012). All procedures were carried out under deep anesthesia, and extensive efforts were made to relief animal suffering.

2.4. Drug treatment and surgical procedure

All the animals were randomly allocated into 5 groups each containing 12 rats as follows: Sham group (SG), Model group (I/R), Nimodipine group (NG), and Protodioscin groups at two dose levels namely low dose group (LG) and high dose group (HG). NG, LG, and HG were intragastrically infused at the doses of 20, 25, and 50 mg Kg−1 of the corresponding drugs respectively, once daily for consecutive 6 days before establishing this model and the final treatment after this surgery, while SG and I/R were only received the same volume of physiological saline.

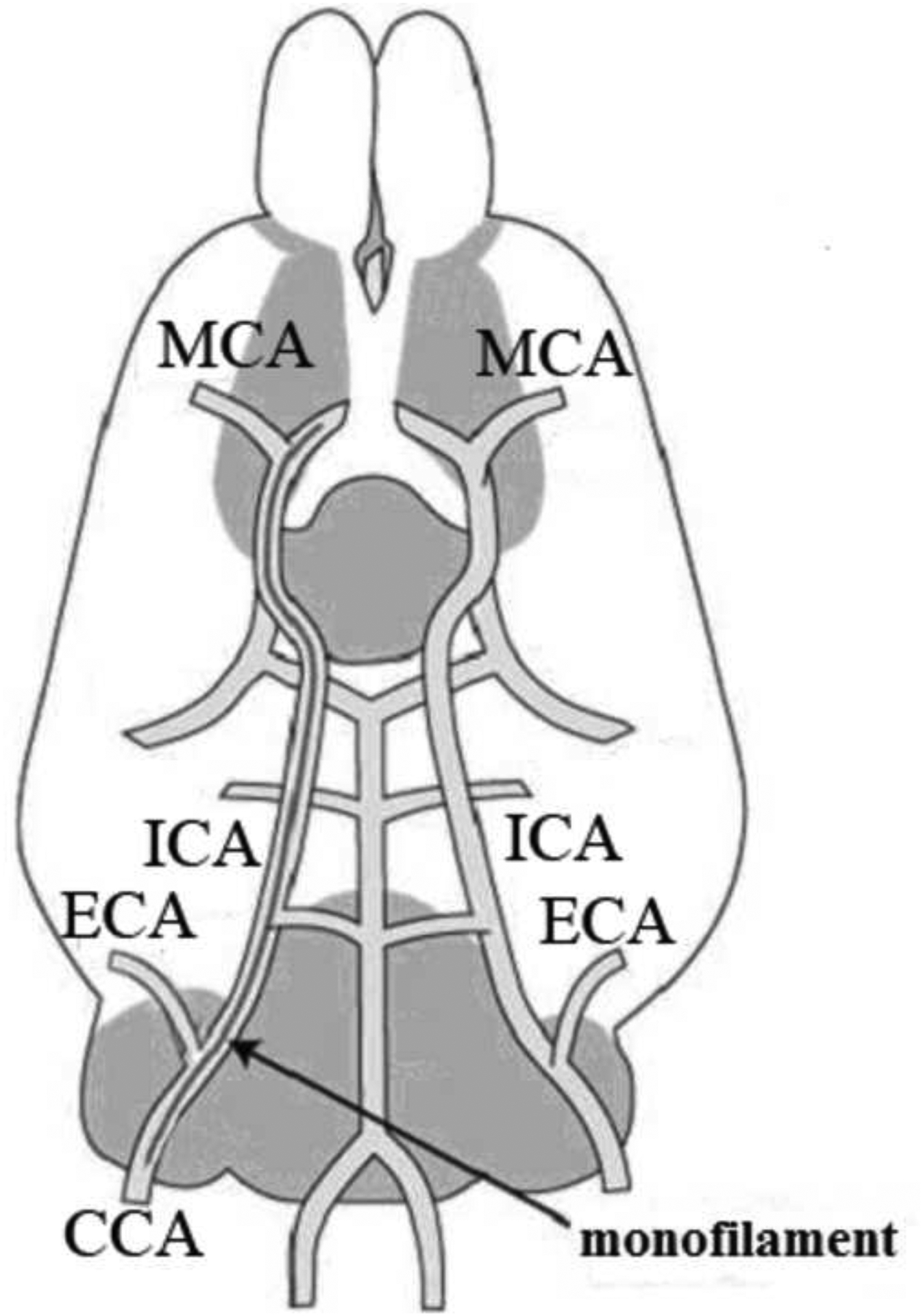

This transient focal I/R injury was induced in rats by MCAO using the intraluminal suture method according to the previous description with minor modifications half an hour after the sixth drug administration [19]. In brief, animals were anesthetized through intraperitoneal injection of chloral hydrate (350 mg Kg−1) and placed in the supine position during entire surgical operation. After a midline incision made on the neck skin, the right common carotid artery (CCA), the external carotid artery (ECA), and the internal carotid artery (ICA) were gently exposed and bluntly separated from the vagus nerve under an operating lamp. The proximal end of CCA and origin of ICA near bifurcation on CCA were both ligated with 4–0 silk suture, and another same suture was simultaneously placed around the origin of ECA like ICA but without tying. The nylon monofilament suture (38 mm in length and 0.24~0.26 mm in diameter), polished round and coated with nail oil tip, was transiently introduced into ECA through a small puncture on CCA at approximately 5 mm from the bifurcation and advanced into the lumen of ICA until feeling gentle resistance, which suggested it reaching the origin of middle cerebral artery (MCA). After finishing this procedure, the silk suture around ECA was tightly ligated to prevent bleeding at this moment, and the rupture on neck skin was sutured. The inserted length from bifurcation to origin of MCA depended on the weight of animal and was in the range of 18~20 mm. In order to establish reperfusion, the filament was cautiously withdrawn from intraluminal by about 10 mm to recover the flow after 90 min blocking of the blood flow (ischemia). Meanwhile, the same procedure was subjected to the rats of SG but without filament insertion. The position of filament in ICA was displayed in Fig. 2. After finishing this surgery, the animals were placed in the cages with soft saw dust to naturally recover their physical strength. A heating-pad was used to maintain the temperature between 37 ± 0.5°C throughout the entire treatment.

Figure 2:

The distribution of major blood vessels in the right cerebral hemisphere of a rat.

MCA: Middle Cerebral Artery; ICA: Internal Carotid Artery; ECA: External Carotid Artery; CCA: Common Carotid Artery

2.5. Keeping records of death rate

The number of death in every group was recorded 24 h after the onset of reperfusion, and expressed as percentage by dividing with the number of rats subjected to the 90 min MCAO surgery.

2.6. Measurement of neurological deficit scores

The neurological examination was performed 24 h after the onset of reperfusion using a modified 5-point scale neurological score system as follows: 0, no neurological deficit symptoms (normal); 1, failure to fully stretch left forepaw when suspended by tails (mildly injured grade); 2, circling to the contralateral side (moderately injured grade); 3, falling toward the left side (severely injured grade); 4, losing the abilities of spontaneous walk and revealing depressed consciousness (most severely injured grade), according to the previous description [20]. The above test was executed in a blind manner and analyzed by an observer who had no knowledge about the treatments.

2.7. Assessment of infarct volume

The anesthetized rats after intraperitoneal injection of chloral hydrate (350 mg Kg−1) were quickly withdrawn all blood from the body through the left ventricle into heparinized saline 24 h after the onset of reperfusion. The whole brains were immediately and gently removed and stored at low temperature based on the corresponding experimental requirements.

The above-obtained brain tissues were at once kept in a −20°C refrigerator for 20 min. After that, the soft frozen brains were cut into five uniform coronal sections at 3 mm thickness with a sharp blade. Then, these slices were immersed into the water bath and incubated in 10 ml of 4% TTC solution containing 3 mL of 4% TTC (4 g TTC was dissolved 100 mL distilled water), 6.8 mL of distilled water and 0.1 mL of 1 mol mL−1 K2HPO4 at 37°C for 30 min in dark. In order to dye evenly, the sections were turned over several times. The well-dyed brain slices were rinsed with ice-cold PBS to avoid further reaction, where the stained red colour indicated non-infarct and unstained white color, infarct. To determine the infarct volume in each section, the TTC-stained tissues were scanned and photographed with a Canon digital camera (PowerShot SX400 IS, Japan), and measured with Image-Pro plus (version 6.0) analyzer software. The percentage of the infarct volume of each section was calculated as follows: the ratio between infarct and total ipsilateral hemisphere areas was multiplied by the thickness (3 mm). The total infarct volume was estimated through summing the infarct volume of 5 sections together.

2.8. TUNEL and immunohistochemistry staining

The collected brains in section 2.7 were immersed into 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 mol L−1 phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH=7.4) and fixed at 4°C overnight. After dehydrated with a graded serial concentration of ethanol for 5 min, the brain tissues were embedded in paraffin and sliced into continuous coronal sections of 5 μm thickness with a rotary microtome. The obtained sections were rehydrated with graded concentrations of alcohol and dewaxed with xylene. To avoid intervening with endogenous peroxidise activity, these processed sections were successively pre-incubated with 1.5% H2O2 in methanol for 15 min to block this reaction and nonspecific protein binding with 3% normal goat serum dissolved in PBS for 20 min. They were rinsed thrice with PBS to clear the goat serum, and these well-handled slices were ready for subsequent use.

For TUNEL (Terminal transferase-mediated dUTP nick end-labeling) assay, an in situ Cell Death Detecting Kit, was used to stain the above histological sections according to the manufacturer’s instructions at 37°C for 1 h under the indicated conditions with darkness and humidity. After rinsing thrice with PBS, these sections were incubated with 3, 3-di-amino-benzidine (DAB) as a chromogen for 15 min, washed with PBS, and then covered with glycerine. The well-stained sections were observed under a fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, CO., Ltd., Germany).

For immunohistochemistry assay, the processed sections were incubated at 4°C for overnight with corresponding primary antibodies namely anti-Caspase-3 diluted at 1:200. It was incubated with avidin-biotin binding peroxidise connected with secondary antibodies at 37°C for 30 min and diluted 1:1000 in the next step. Subsequently, the same samples were finally treated with DAB, a peroxidase substrate combined with secondary antibodies. To stop the reaction and clear remaining antibodies in the incubated sections, they were rinsed at least thrice before and after the corresponding treatments. The images of these sections were photographed using an optical microscope (Olympus/BX51, Tokyo, Japan).

The positive cells of TUNEL and Caspase-3 in the cortex and hippocampus CA1 of the right ipsilateral injured hemisphere were evaluated by a blinded observer. Five microscopic fields in each section were randomly selected, and the number of stained cells in these regions was counted. The average value was regarded as the final result after counting three times.

2.9. Determining the concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines in rat serum

The rats were anesthetized with intraperitoneal injection of chloral hydrate at the dose of 350 mg Kg−1, and the blood was extracted from the abdominal vein immediately 24 h after onset of reperfusion. This sample was kept for 1~2 h at 4°C, and then centrifuged for 10 min at 4000 rpm. The serum was stored in a −20°C refrigerator for subsequent use. The levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in the serum were measured by commercially available ELISA kits according to their corresponding manufacturer’s instructions. The units of these detected indicators were expressed in nanograms per litre.

2.10. Evaluation of Bcl-2, Bax, NF-κB and IκBα protein expression by western blotting analysis

The right hemisphere of injured brain tissues was carefully isolated from the obtained brains (section 2.7) and stored in −80°C for subsequent use. These tissues were homogenized and lysed in proper cold RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitors. The generated lysates were centrifugated at 15000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatants were collected. The total protein contents were estimated by the BCA assay kit based on its manufacturer’s instructions. Then, 50-microgram of protein sample solution was separated by10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacryl-amide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) for 4 h. After finishing electrophoresis, they were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (PVDF, Millipore), and then the membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat dried milk dissolved in TBST buffer (pH=7.5), containing Tris-HCl (10 mmol L−1), NaCl (150 mmol L−1), and 0.1% Tween 20, for 2 h at room temperature. After washing three times with PBS, the membranes were individually incubated with primary antibodies of anti-Bcl-2, anti-Bax, anti-NF-κB and anti-IκBα (1:500, 1:200, 1:1000, and 1:1000 dilution, respectively) at 4°C in a refrigerator overnight. Subsequently, these membranes were incubated with the secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish-peroxidase diluted at 1:5000 at ambient temperature for 30 min after rinsing thrice by PBS. After extensive washing, the target immunoreactive bands were detected using the enhanced chemical luminescence system and visualized by an autoradiography. The interested bands were analyzed and quantified with image analysis software (USA). NF-κB protein expression was investigated in cell cytoplasm and nucleus, while IκBα expression only in cell cytoplasm. To avoid variations, the data were adjusted and expressed as the ratio after the IOD of aimed protein versus IOD of Actin and H3 protein, which were both selected as the internal loading control.

2.11. Statistical analysis

The results were presented as means ± SD (standard deviation) and analyzed with the SPSS software (version 19.0). This One-Way analysis of variance (ANOVA) following the Dunnett’s multiple comparison tests system was used to evaluate the statistical significance. After estimation, P values less than 0.05 as threshold index were considered as statistically significant difference in the current research.

3. Results

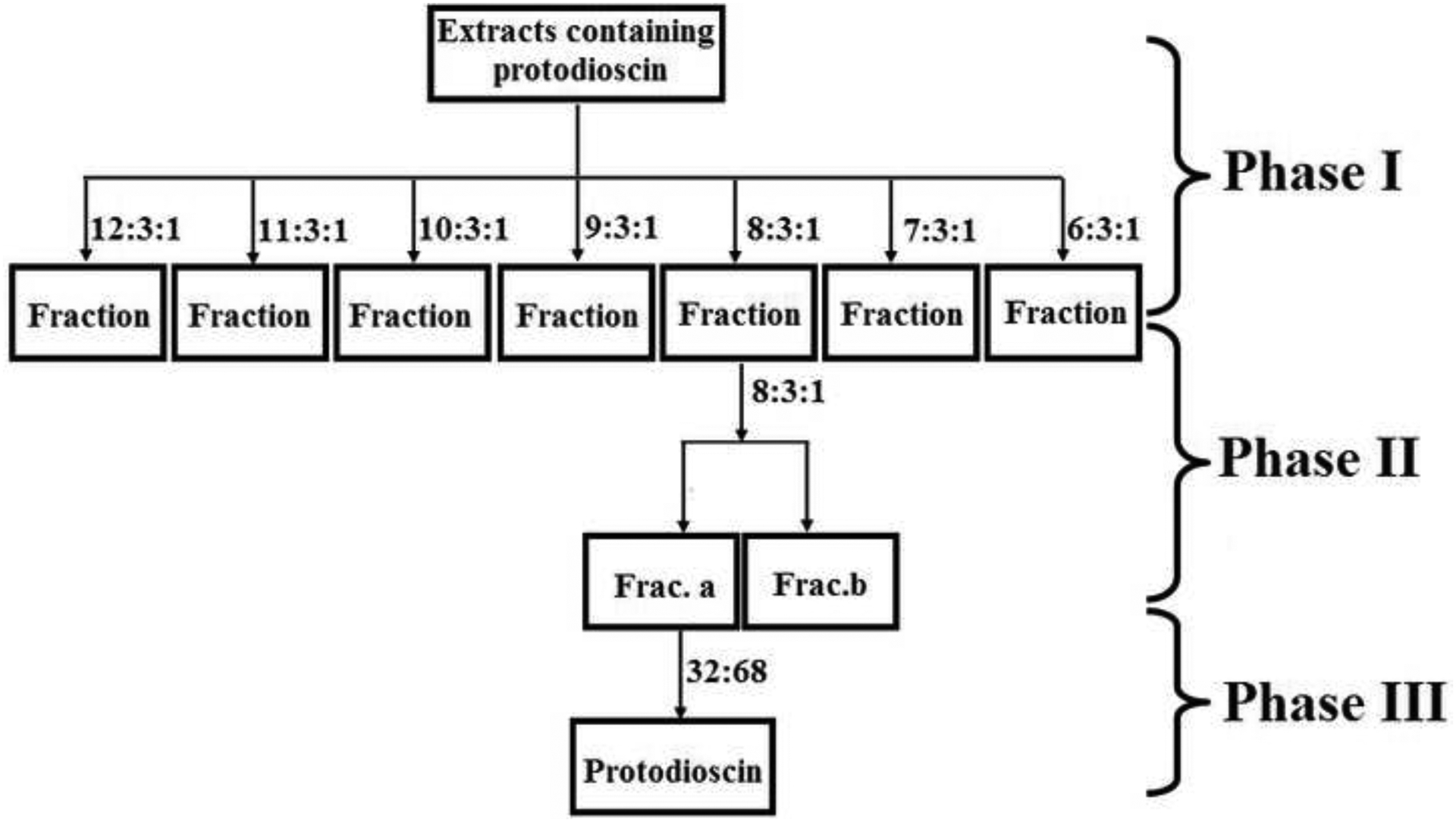

3.1. Purification and identification of protodioscin from D. zingiberensis

As detailed in section 2.2, the pure protodioscin was isolated from the dried rhizome of D. zingiberensis through a series of various separation technologies including extraction, D-101 macroporous resin column, normal silica gel column, and semi-preparative HPLC. This tedious procedure was shown in a simplified flow diagram in Fig. 3–5. The chemical structure of the obtained protodioscin was analyzed by combined spectroscopic techniques of ESI-MS, 1H-NMR, and 13C-NMR. Its molecular formula was deduced and calculated as C51H84O22 from the protonated molecular ion [M+H]+ (m/z 1050.2033), and there were two hexoses and two methyl-pentoses in the structure according to its major ion fragmentation patterns. After acidolysis of protodioscin, the identification of sugars was performed on TLC, and the hexose was demonstrated as D-glucose, while pentose as L-Rhamnose, based on the similar chromatographic behaviours of reference standards, i.e. displaying the same Rf values. There were major four methylic proton peaks at δ 0.71 (s, 3H, Me-18), 0.85 (s, 3H, Me-19), 1.02 (d, 3H, J=7.2 Hz, Me-21) and 1.29 (d, 3H, J=7.2 Hz, Me-27) in 1H-NMR, and they were characteristic signals of steroidal aglycone. What’s more, chemical shifts at δ 4.81 (d, J=7.8 Hz, 1H), 4.90 (d, J=7.2 Hz, 1H), 6.35 (br s, 1H) and 6.25 (br s, 1H) in this spectrogram belonged to the signals of sugar anomeric (?) carbon protons, and were consistent with the sugar number in the structure of protodioscin. While, δ 1.68 (d, J=6.1 Hz, 3H, Me-Rha) and 1.76 (d, J=6.1 Hz, 3H, Me-Rha) were attributed to the two methylic protons of rhamnose. Along with the data of 13C-NMR shown in Table 1 and the reference standard, this compound was finally confirmed to be protodioscin.

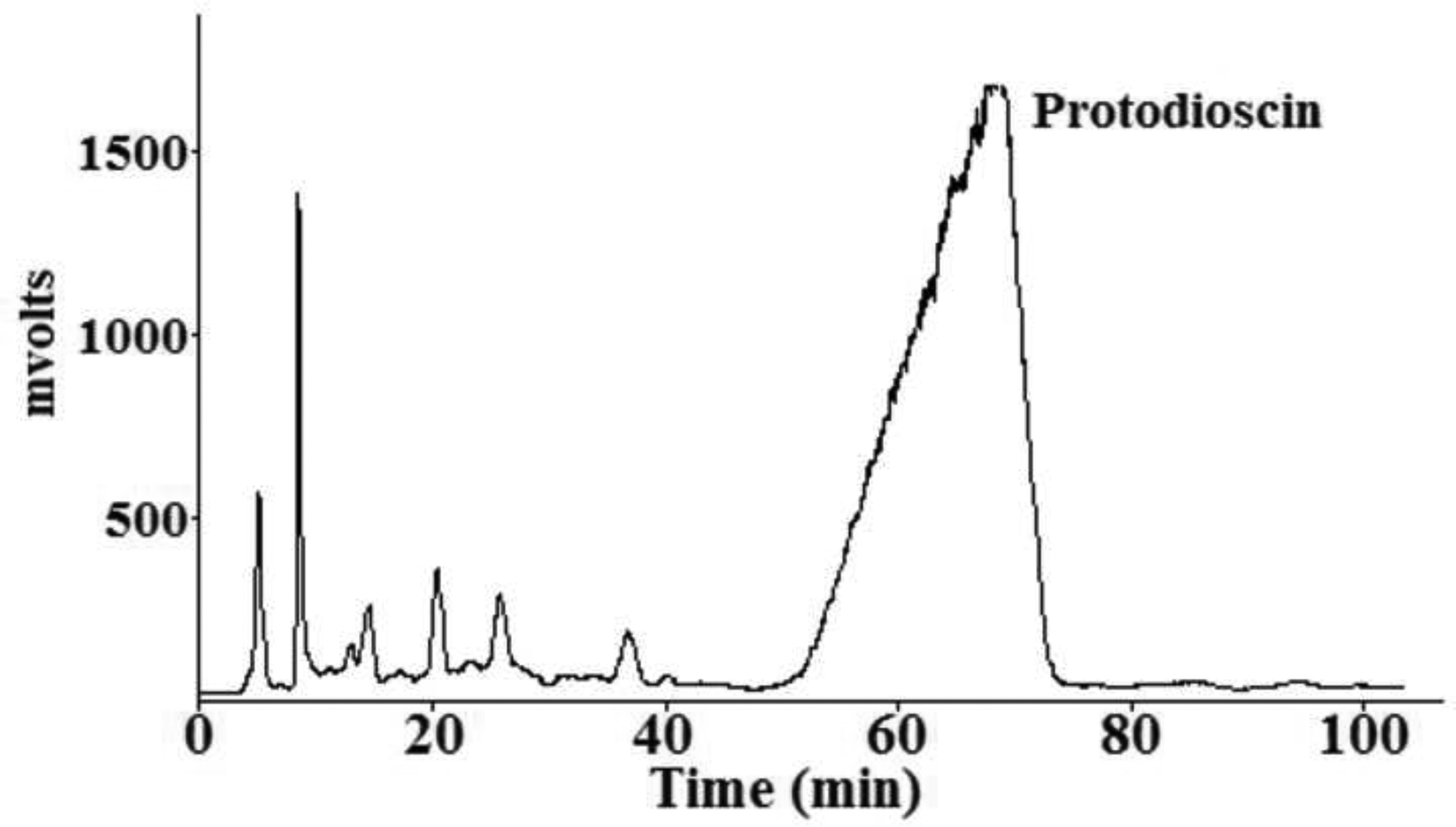

Figure 3:

The flow diagram of the procedure used for extraction of protodioscin from the rhizome of Dioscorea zingiberensis C.H. Wright

Figure 5:

The chromatograph of purifying protodioscin from Frac. A obtained after tedious steps.

The mobile phrase: acetonitrile-water; Flow rate: 50 mL min−1; Conditions of ELSD: the drift tube temperature was set 55, and the gas flow rate was 3 L min−1.

Table 1.

The chemical shifts of carbon atoms of protodioscin in 13C-NMR (C5D5N-d6, 125 MHz).

| NO. | Aglycone | Glu′ | Glu″ | Rha′ | Rha″ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 37.4 | 101.2 | 105.5 | 102.7 | 103.2 |

| 2 | 29.9 | 78.0 | 75.4 | 72.3 | 72.2 |

| 3 | 79.2 | 78.2 | 78.0 | 72.9 | 72.6 |

| 4 | 38.2 | 77.5 | 72.2 | 73.5 | 72.4 |

| 5 | 141.1 | 75.9 | 78.3 | 69.4 | 70.8 |

| 6 | 121.4 | 61.8 | 63.3 | 18.8 | 18.5 |

| 7 | 32.8 | ||||

| 8 | 31.1 | ||||

| 9 | 50.5 | ||||

| 10 | 36.2 | ||||

| 11 | 21.6 | ||||

| 12 | 39.4 | ||||

| 13 | 40.2 | ||||

| 14 | 57.0 | ||||

| 15 | 31.8 | ||||

| 16 | 92.2 | ||||

| 17 | 63.2 | ||||

| 18 | 17.2 | ||||

| 19 | 19.6 | ||||

| 20 | 40.5 | ||||

| 21 | 16.9 | ||||

| 22 | 110.2 | ||||

| 23 | 37.9 | ||||

| 24 | 27.3 | ||||

| 25 | 34.9 | ||||

| 26 | 75.5 | ||||

| 27 | 17.1 |

3.2. Protodioscin ameliorated the death rate induced by MCAO in rats

The death rate was a direct-viewing indicator to offer valuable information and its records were saved to reflect the therapeutic efficacy of protodioscin. Five rats couldn’t suffer from 24 h reperfusion and died ahead of prescribed time. To guarantee 12 animals in every group, 17 rats were finally experienced the surgical operation. Therefore, the death rate of I/R group was 45.5% (10/22). Two rats died in the NG group, and its death rate was 14.2% (2/14). Due to without blockage of ICA, the SG group revealed no death. To our astonishment, the death rate was 7.7% (1/13), and 0% in the LG and HG groups, respectively, 24 h after restoring the blood flow, and all other rats lived longer beyond the time range of reperfusion. Before obtaining other supportive evidences, the above simple findings implied that protodioscin could effectively protect the rats from the I/R injury by its 7-day pre-treatments.

3.3. Protodioscin inhibited the increase in neurological deficit scores and infarct volume induced by MCAO in rats

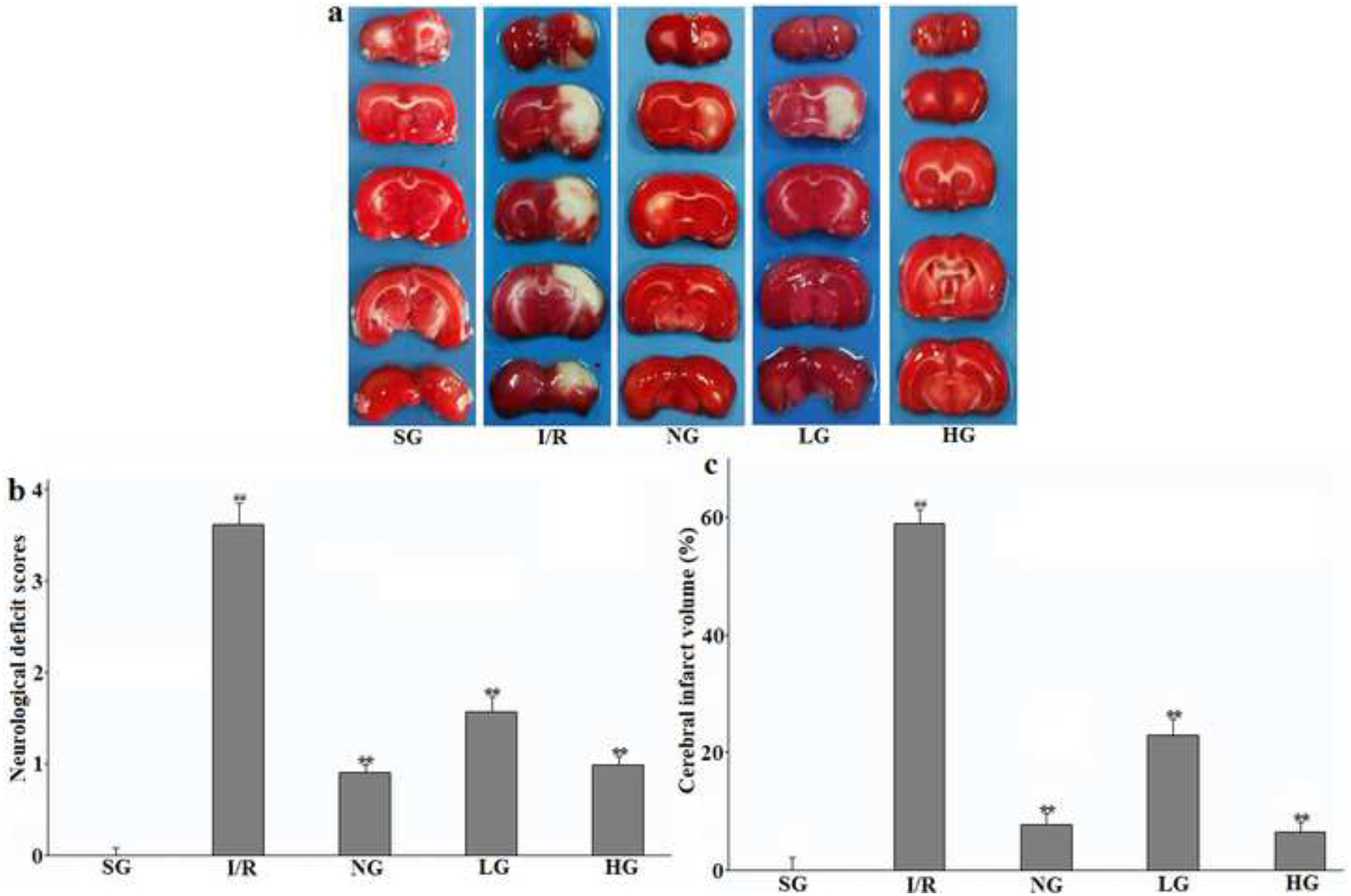

Compared with the SG group, the I/R group produced a significantly increased neurological deficit score (P<0.01) as shown in Fig. 6, suggesting that this imitative model was successfully established. The higher this evaluated score system, the more severe impairments of motor abilities. The rats in the I/R group showed uneasy or alleviated mobility and depressed emotion 24 h after the onset of reperfusion. However, these symptoms were attenuated after administration of protodioscin, and this treatment finally led to a functional recovery and reduction of neurological deficit scores in a dose-dependent manner (P<0.05 for two dosages). What’s more, protodioscin revealed similar therapeutic effect to the positive control drug nimodipine (P<0.05).

Figure 6:

Therapeutic effect of protodioscin on neurological deficit scores and cerebral infarct volume.

The rats were exposed to transient ischemia for 90 min exerted by MCAO and sacrificed 24 h after reperfusion. The treatments with drugs were kept for seven days. The brain was sliced into coronal sections and stained with TTC solution. (a): Representative TTC-stained photos; (b): Neurological deficit scores; (c): Cerebral infarct volume. The obtained values were presented as mean ± SD (n=12 each group). #p versus SG group and *p versus the I/R group, respectively. SG, sham group without occluding the blood flow and drug treatment; I/R, model group without drug treatment after MCAO operation; NG, nimodipine-treated group after MCAO; LG, protodioscin (low dose)-treated group after MCAO; HG, protodioscin (high dose)-treated group after MCAO.

The typical histological slides of coronal sections after TTC-strained to observe brain infarct volume were shown in Fig. 6 which clearly indicates that there were no infarct volumes in rats of the SG group with no filament in the intraluminal of ICA. After 24 h of reperfusion, percentage of the infarct volume was remarkably increased in the I/R group (P<0.01). As expected, the pre-treatment with protodioscin dose-dependently (P<0.05 for two dosages) suppressed this change so that the infarct areas in the HD and LD groups were much smaller than that in the I/R group. At the same time, this positive effect was also observed in NG group (P<0.05). This indicator was in agreement with the neurological deficit scores.

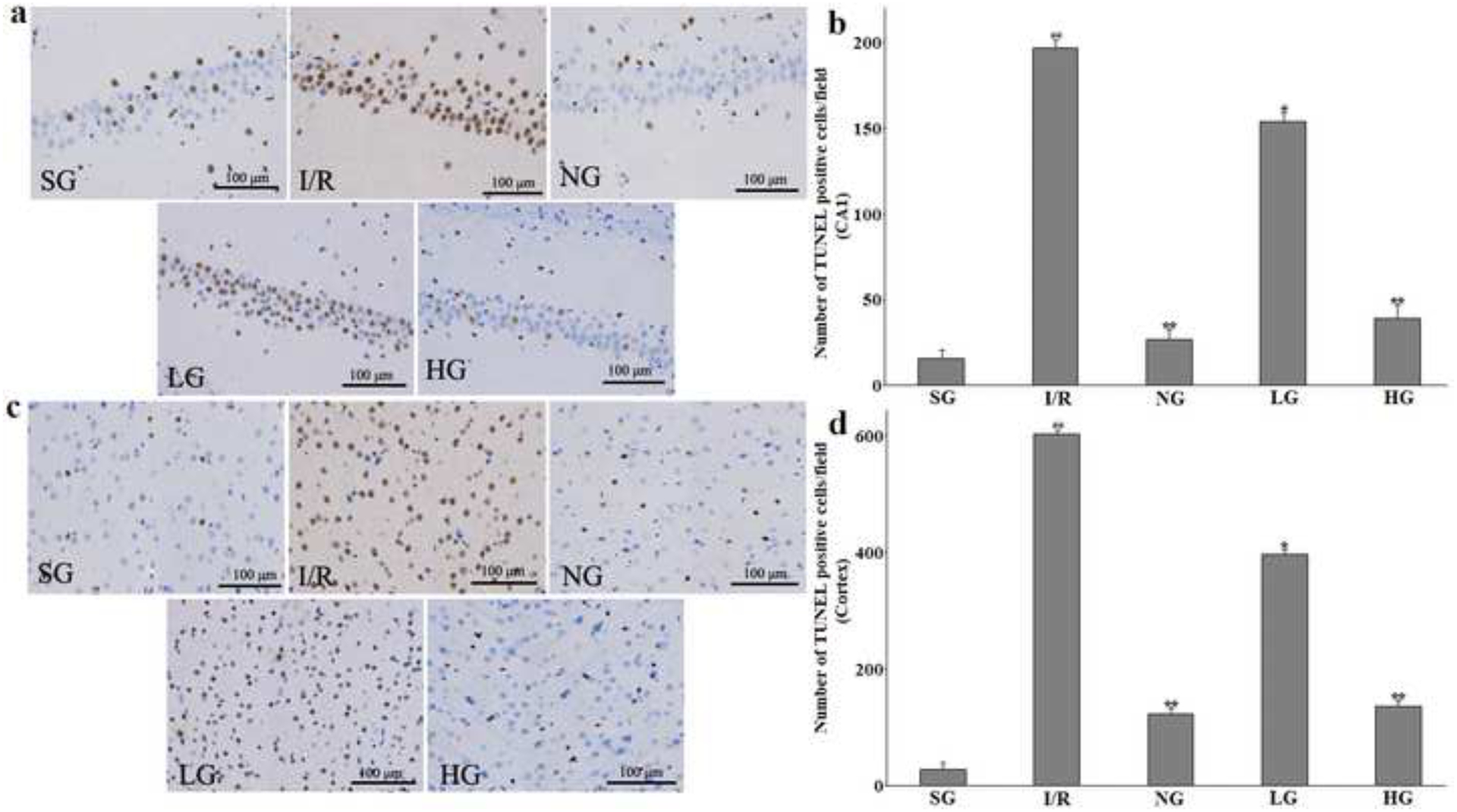

3.4. Protodioscin reduced the apoptotic nerve cells induced by MCAO in rats

The TUNEL staining to detect DNA fragmentation which was characteristic markers and manifestations of apoptosis was used to evaluate the apoptotic neurons in the right ipsilateral hemisphere. As compared to the SG group with no existence of apoptotic neurons, the number of positively stained cells in I/R group was significantly increased in the cortex and hippocampus CA1 24 h after the reperfusion (P<0.01 for both two regions displayed in Fig. 7a–b). After preconditioning with protodioscin for a 7-day period, the number of TUNEL-stained cells were gradually reduced (P<0.05 for 25 mg Kg−1 in two regions; P<0.01 for 50 mg Kg−1 in two regions) compared with the I/R group which showed that a smaller penumbra area was seen in a surrounding smaller infarct core area. This similar pharmacological result was seen in the NG group, and the P values of statistical difference were less than 0.01 at above-discussed areas.

Figure 7:

Therapeutic effect of protodioscin on neurons apoptosis measured by TUNEL staining.

The rats were exposed to transient ischemia for 90 min exerted by MCAO and sacrificed 24 h after reperfusion. The treatments with drugs were kept for seven days. The positive TUNEL cells on the photomicrographs were stained with tawny colour and indicated the apoptotic neurons. a and c: The representative images of TUNEL assay in hippocampus CA1 and cortex, respectively. b and d: The quantitative analysis of the positive cells in hippocampus CA1 and the cortex, respectively. The obtained values were presented as mean ± SD (n=5 each group). #p versus SG group and *p versus the I/R group, respectively. Photomicrographs are magnified by 200 times, and scale bar equals 100 μm. SG, sham group without occluding the blood flow and drug treatment; I/R, model group without drug treatment after MCAO operation; NG, nimodipine-treated group after MCAO; LG, protodioscin (low dose)-treated group after MCAO; HG, protodioscin (high dose)-treated group after MCAO.

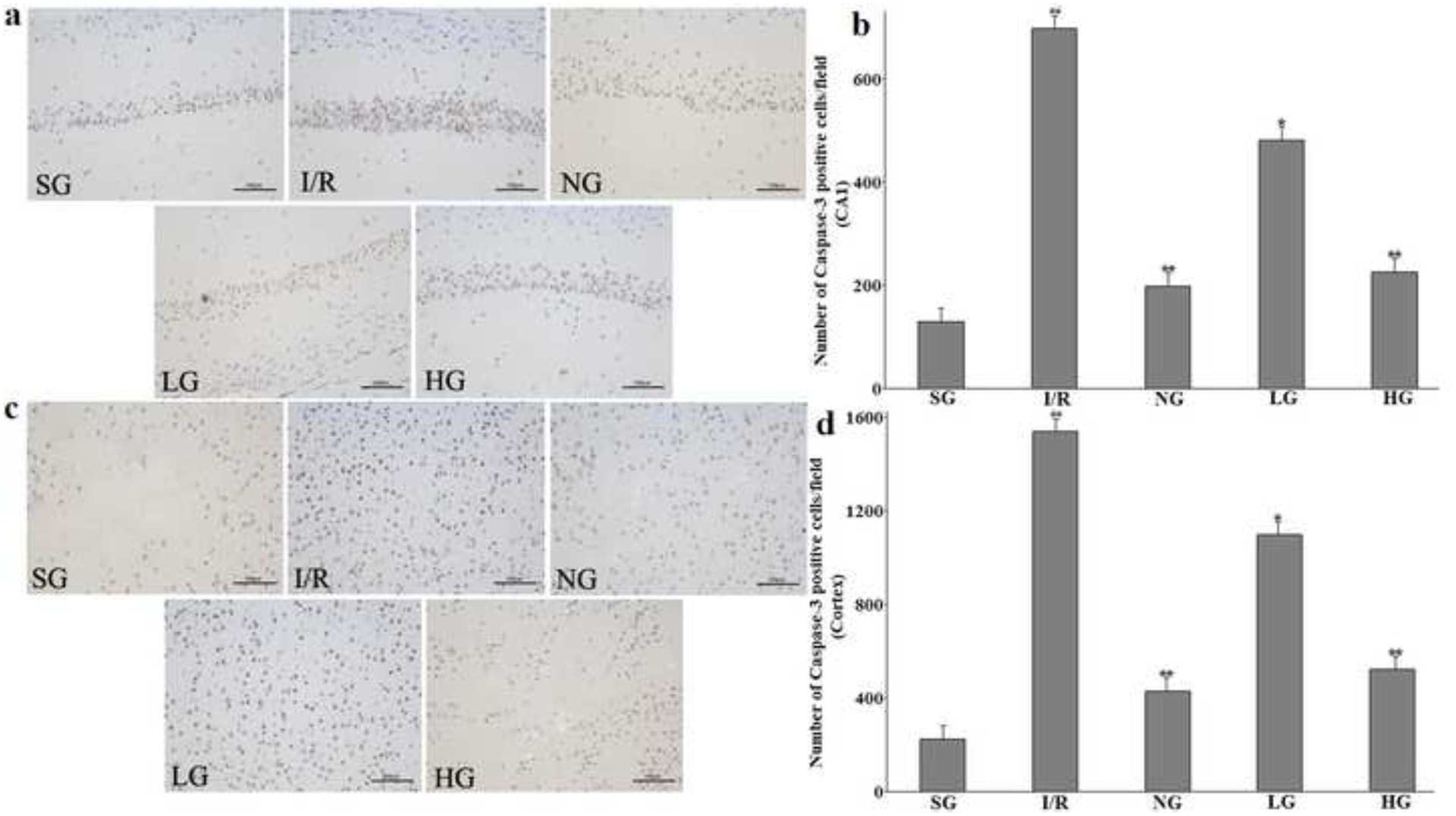

3.5. Protodioscin attenuated the change of relevant apoptins induced by MCAO in rats

In order to find out the mechanism involved in the apoptosis protective effect of protodioscin in the brain, the related protein expressions of Caspase-3 was investigated by immunohistochemical analysis after 24 h reperfusion. As illustrated in Fig. 8a–b, compared to the SG group, the positive cells of Caspase-3 in the I/R group were markedly elevated in the cortex and hippocampus CA1 of the injured ipsilateral hemisphere (P<0.01), which was distinctly and dose-dependently ameliorated after oral administration of the corresponding drugs in rats of NG, LG, and HG groups as compared with I/R group. All their statistical data revealed the significant difference.

Figure 8:

Therapeutic effect of protodioscin on Caspase-3 activity evaluated by immunohistochemistry.

The rats were exposed to transient ischemia for 90 min exerted by MCAO and sacrificed 24 h after reperfusion. The treatments with drugs were kept for seven days. a and c: The representative pictures of positive Caspase-3 cells in hippocampus CA1 and the cortex, respectively. b and d: The quantitative analysis of the positive cells in hippocampus CA1 and the cortex, respectively. The obtained values were presented as mean ± SD (n=5 each group). #p versus SG group and *p versus the I/R group, respectively. Photomicrographs are magnified by 200 times, and scale bar equals 100 μm. SG, sham group without occluding the blood flow and drug treatment; I/R, model group without drug treatment after MCAO operation; NG, nimodipine-treated group after MCAO; LG, protodioscin (low dose)-treated group after MCAO; HG, protodioscin (high dose)-treated group after MCAO.

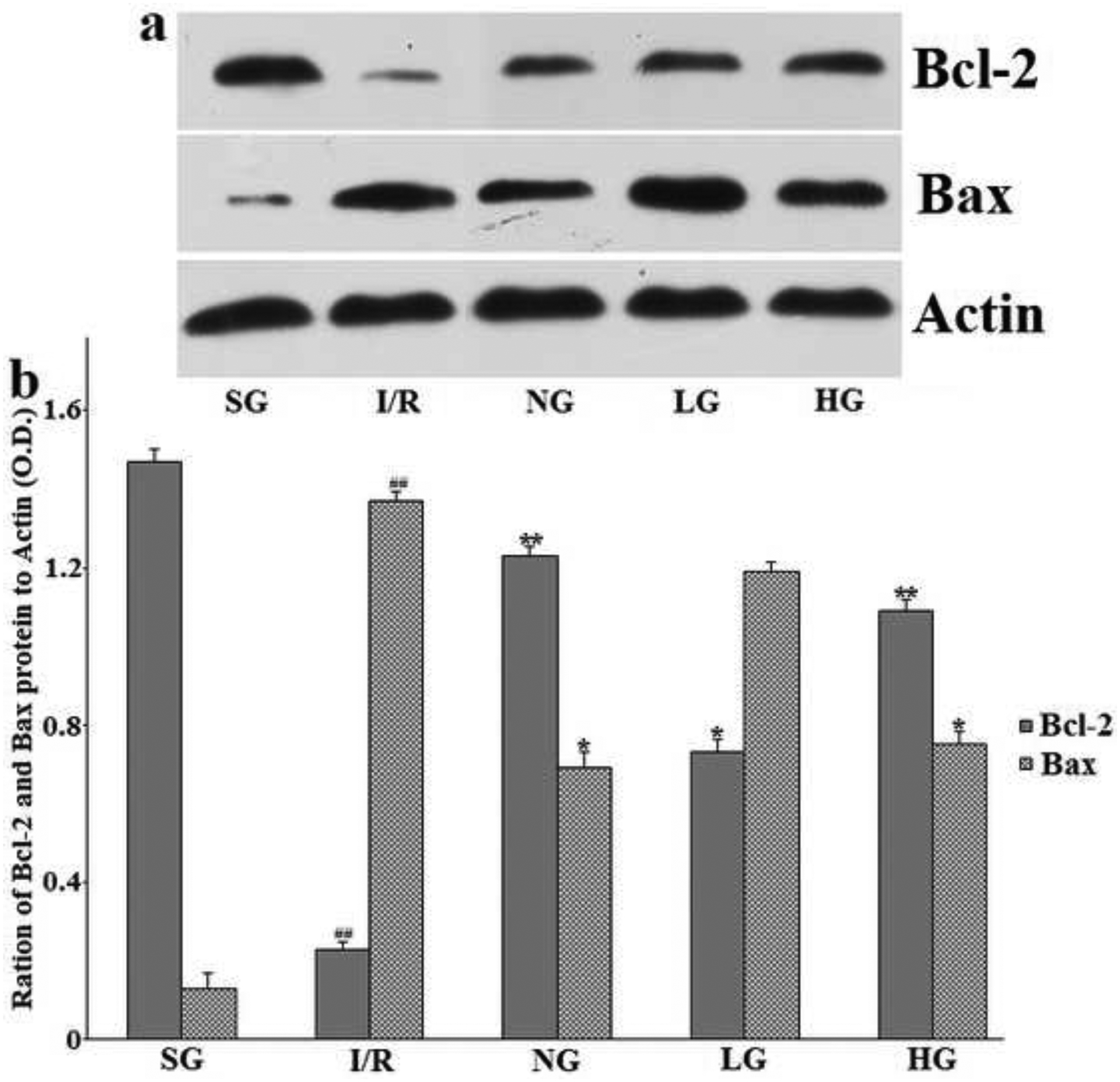

In order to further explore the apoptotic signal, the expressions of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 and pro-apoptotic protein Bax in the injured hemisphere of the rat brain were also evaluated by western blotting after 24 h reperfusion. Aspresented in Fig. 9a–b, it elaborated that Bcl-2 protein levels decreased by I/R compared with SG group was remarkably increased after treatment with PG (P<0.01 for HG, P<0.05 for LG). However, the expression of Bax protein was restored to its normal level in the opposite direction on the contrary (P<0.05 for HG). Correspondingly, the ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 was obviously inhibited in the PG group compared with the I/R group without drug treatment.

Figure 9:

Effect of protodioscin and Nimodipine on expression Bcl-2 and Bax protein in the ipsilateral ischemic hemisphere.

The rats were exposed to transient ischemia for 90 min exerted by MCAO and sacrificed 24 h after reperfusion. The treatments with drugs were kept for seven days. (a) Representative results of Western blotting. (b) Quantitative analysis. The protein levels were normalized against the Actin, which served as loading control. Values are expressed in relative optical density and represented as means ± SD (n=3 per group). #p<0.05 versus the Sham group, *p<0.05 versus the I/R group, respectively. SG, sham group without occluding the blood flow and drug treatment; I/R, model group without drug treatment after MCAO operation; NG, nimodipine-treated group after MCAO; LG, protodioscin (low dose)-treated group after MCAO; HG, protodioscin (high dose)-treated group after MCAO.

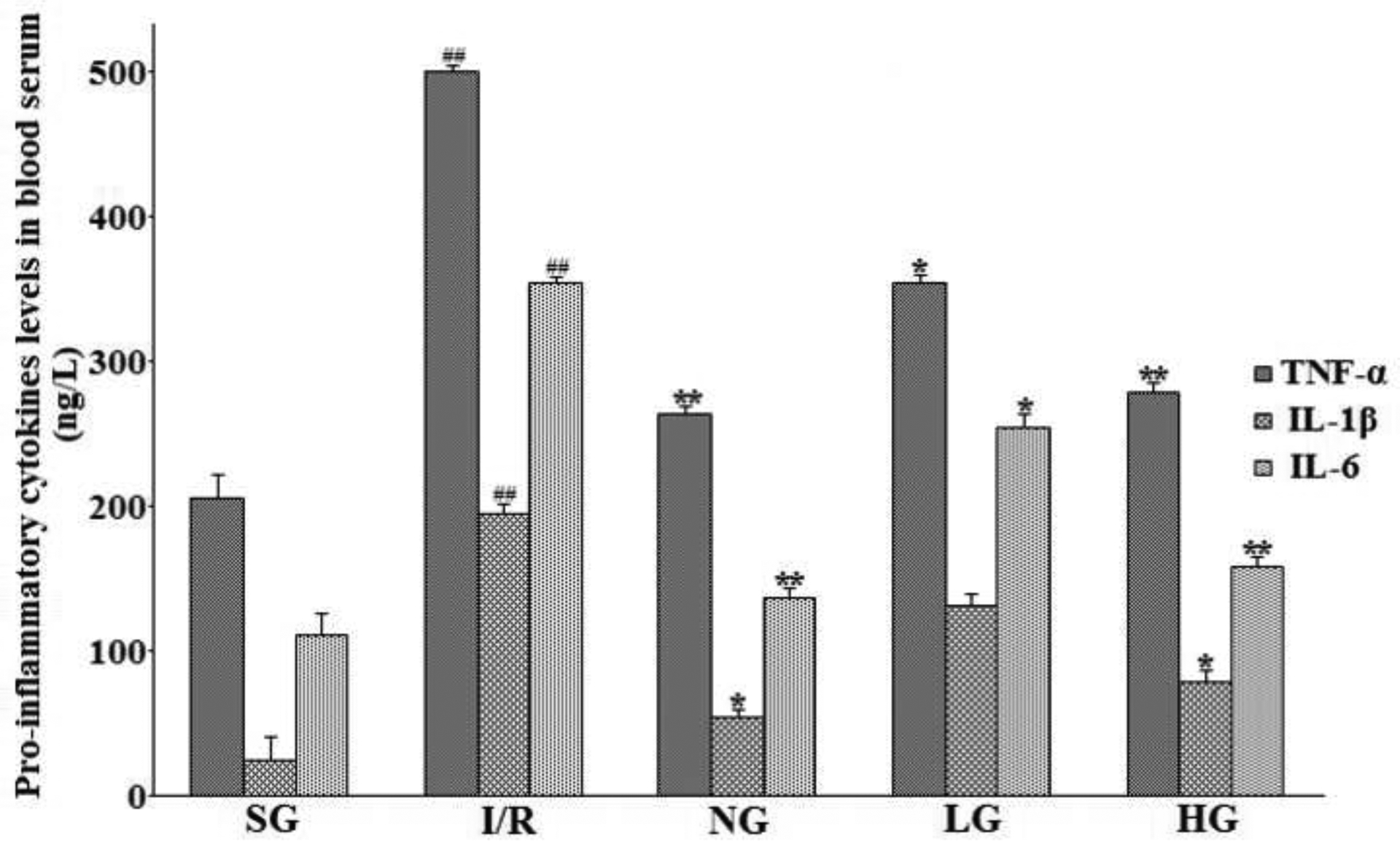

3.6. Protodioscin suppressed the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines in serum induced by MCAO in rats

When the body is exposed to internal or external stimulus, the inflammatory signal pathways is triggered to release various inflammatory factors into the blood. So is the same with the cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. Therefore, several crucial pro-inflammatory cytokines, i.e. TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, in rat serum were analyzed using commercially available ELISA kits 24 h after starting reperfusion. As demonstrated in Fig. 10, the concentrations of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 in the rat serum of the I/R group were evidently increased by 152.7% (P<0.01), 138.4% (P<0.01), and 125.3% (P<0.01), respectively, when compared with those in the SG group. However, administration of purified protodioscin (25, 50 mg Kg−1) and nimodipine (20 mg Kg−1) for several days prior to performing MACO led to a remarkable decrease in these levels of three detected indicators by 63.7%, 44.8%, and 41.2% for TNF-α, 58.1%, 32.7%, and 30.9% for IL-1β, 69.7%, 48.8%, and 44.5% for IL-6, respectively, as compared with the I/R group.

Figure 10:

Therapeutic effect of protodioscin on pro-inflammatory cytokines determined by ELISA.

The rats were exposed to transient ischemia for 90 min exerted by MCAO and sacrificed 24 h after reperfusion. The treatments with drugs were kept for seven days. The units were presented as ng L−1. The obtained values were presented as mean ± SD (n=12 each group). #p versus SG group and *p versus the I/R group, respectively. SG, sham group without occluding the blood flow and drug treatment; I/R, model group without drug treatment after MCAO operation; NG, nimodipine-treated group after MCAO; LG, protodioscin (low dose)-treated group after MCAO; HG, protodioscin (high dose)-treated group after MCAO.

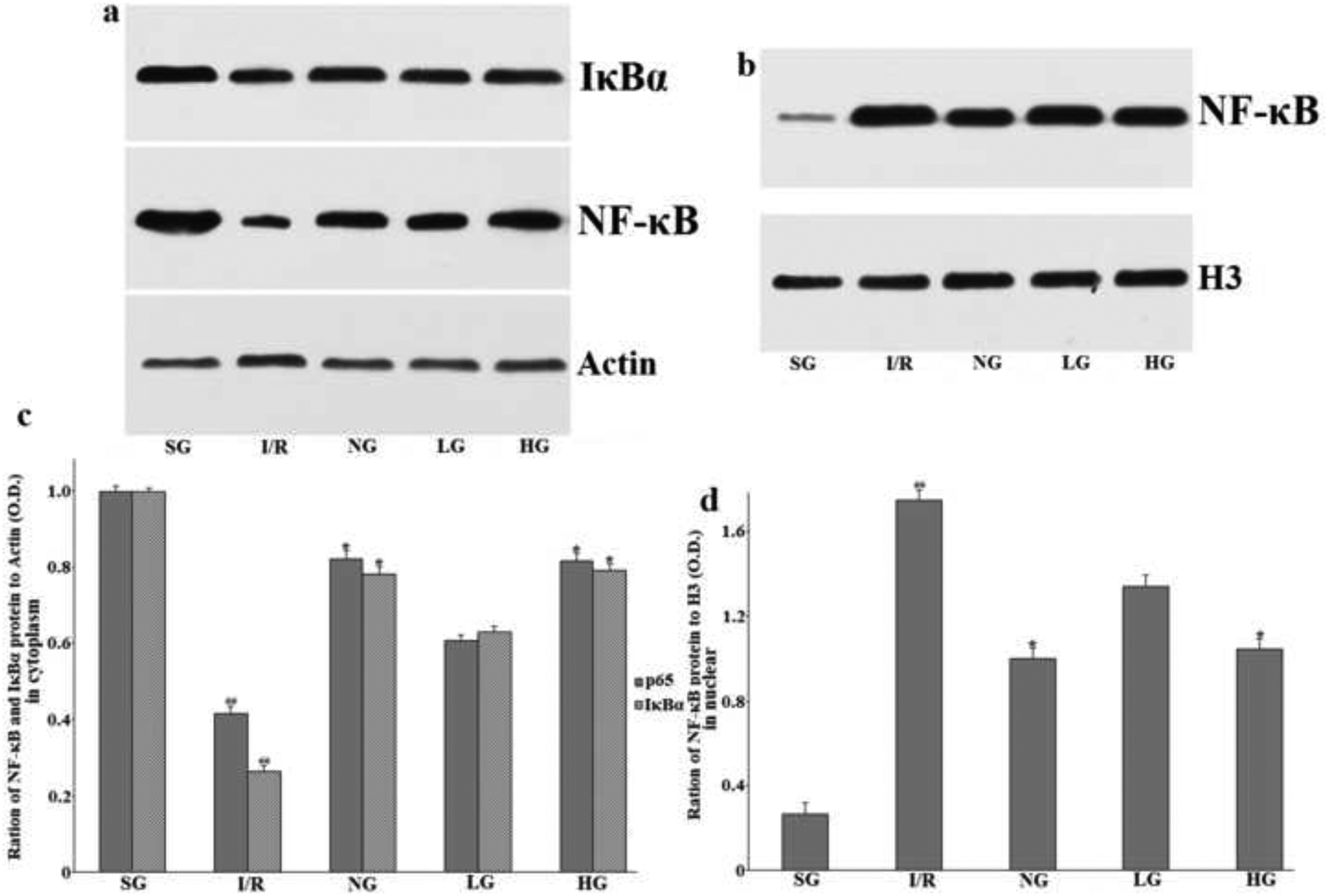

3.7. Protodioscin reversed the protein expression of NF-κB (in nucleus and cytoplasm) and IκBα (in cytoplasm) induced by MCAO in rats

As compared with the SG group and illustrated in Fig. 11 (a and c), the NF-κB and IκBα protein expression, measured by western blotting analysis in cytoplasm of the injured ipsilateral hemisphere brain were both remarkably down-regulated in the I/R rats subjected to MCAO after 24 h reperfusion with P less than 0.01, whereas the circumstance of NF-κB in Fig. 11 (b and d) expression in nucleus was contrary to that in cytoplasm forming a sharp increase (P<0.01). When compared with the I/R group, these protein expressing in nucleus and cytoplasm induced by this harmful operation was restored almost to their normal level before surgery after administration with protodioscin and nimodipine at the corresponding dosages for seven days in a dose-dependent manner. The statistical analysis showed significant difference, confirming that protodioscin indeed influenced the protein expression of NF-κB and IκBα in a positive way.

Figure 11:

Therapeutic effect of protodioscin on NF-κB and IκBα protein expression in cytoplasm and nucleus by western blotting analysis.

The rats were exposed to transient ischemia for 90 min exerted by MCAO and sacrificed at 24 h after reperfusion. The treatments with drugs were kept for seven days. a: The typical western blotting of NF-κB and IκBα in cytoplasm; b: The typical western blotting of NF-κB in nucleus; c and d: The quantitative analysis. The protein expression levels were normalized to the level of H3, a loading control in this research. The obtained values were presented as mean ± SD (n=3 each group). #p versus SG group and *p versus the I/R group, respectively. SG, sham group without occluding the blood flow and drug treatment; I/R, model group without drug treatment after MCAO operation; NG, nimodipine-treated group after MCAO; LG, protodioscin (low dose)-treated group after MCAO; HG, protodioscin (high dose)-treated group after MCAO.

4. Discussion

In the current research, the cerebroprotective therapeutic effect of protodioscin was evaluated using a transient focal cerebral ischemia-reperfusion rat model, which was successfully established by MCAO for 90 min followed by the 24 h reperfusion by restoring the blocked blood flow. In this experimental model, intragastrical infusion of protodioscin for seven days in the injury rats markedly decreased the death rate, and produced various positive results such as reduction of the neurological deficit scores, inhibition of the cerebral infarct volume analyzed by TTC-staining, suppression of the apoptotic cells detected by TUNEL-staining, and attenuation of the release of several crucial pro-inflammatory factors. Also, the neurological function and motor coordination ability were widely improved in some extent and these findings well confirmed the potential effect of protodioscin against this severe cerebral injury.

Two major different regions, i.e. “core and penumbra”, of the brain subjected to I/R insult are defined according to their response which are well understood by the researchers in this field [21]. Penumbra is “the area that can be rescued by pharmacological agents” or “the region of constrained blood supply in which energy metabolism is preserved” [22]. The penumbra is mainly located in the peripheral portions of the ischemic core. The primary difference between these two areas is the survival manners of neurons [23]. The cells in the I/R brain suffer from the necrosis or apoptosis. Because the cerebral blood flow into the core below the threshold fails to supply the energy for metabolisms and ion pump functions, these necrotic cells in the core region suffer from swelling and lysis ending at rapid death, and this change is irreversible [24]. On the other hand, the cells in penumbra die from the programmed apoptosis during the I/R, which is different from the necrosis in the core region, as this cell impairment could be saved through timely measures [25]. As aforementioned, in “penumbra” defined as a focal area, some of the neurons in this portion will be recovered by agents intervention, because they remain viable for several hours after subjected to the I/R injury. Otherwise, neuronal damage will spread from the ischemic core to the penumbra until the infarct reaches its maximal volume. Our present study revealed that the protodioscin could apparently ameliorate the increase in the number of apoptotic cells evaluated by TUNEL staining method. The results contributed to the reduction of brain injury, and this anti-apoptotic effect seems to be the underlying mechanisms of efficacy of protodioscin in resisting against I/R injury.

Amounting materials have suggested that apoptosis plays a pathogenetic part in conditioning the neuron loss induced by I/R in rats, where several major mediators including caspases and Bcl family were involved during this process. It has been proved that apoptosis is mainly consisted of the initial and executional steps and carried out by caspases, a group of intracellular cysteine proteases [26]. Some initiator and executioner members of the caspases have been obtained and their spatial configuration also identified. Activating one caspase protease could cause activation of the other additional molecules of proteases by cleaving the corresponding substrates [27], and this neuron apoptosis mediated in the above-mentioned manner results in an amplified cascade event in the end. Among these proteases, Caspase-3 is considered as a critical participator and the final executioner of neuron apoptosis [28]. When the upstream caspase proteases such as caspase-8 and caspase-9 are activated, they both could finally lead to the down-stream Caspase-3 activation [29]. Then, the morphological changes and the DNA fragmentation of neuron might be attributed to this activated Caspase-3 after a series of reactions, and the apoptotic cell death occurs. The current results revealed that the activity of Caspase-3 in hippocampus CA1and the cortex of the injured ipsilateral hemisphere was apparently increased after the rats were subjected to I/R. Pre-treatment with protodioscin could evidently improve the neuron survival via examination of enhanced positively stained Caspase-3 cells in agreement with TUNEL analysis, and this anti-apoptotic effect could be contributed to the attenuation of this activation of Caspase-3.

Further, Bcl-2 and Bax are other important regulators of apoptosis. Bcl-2 which is located in the mitochondrial outer membrane and regarded as an anti-apoptotic protein is a crucial activator in the apoptotic pathways. It suppresses the secretion of cytochrome C into the cytoplasm to interfere with the programmed death and promote the cell survival [30]. On the contrary, the pro-apoptotic protein of Bax, whose DNA sequence is homologous with Bcl-2, is an antagonist of Bcl-2 and triggers the cell apoptosis [31]. In cell, the Bcl-2 and Bax are binding together to form either homologous or heterologous dimmers depending on the physiological conditions [32], and the occurrence of neuron apoptosis is governed by the heterodimers of Bax/Bcl-2. The neurons will sustain their survival when this equilibrium towards Bcl-2 is kept in normal. If not, they will be susceptible to apoptosis when this equilibrium is shifted towards Bax after the exposure to harmful stimuli [33]. Therefore, the expression levels between Bcl-2 and Bax could be used to determine the neuron destiny. The Bcl-2 protein expression was decreased in the injured ipsilateral hemisphere when rats suffered from I/R injury induced by MCAO, while the Bax were markedly increased. Due to disturbance of the afore-discussed equilibrium, the neurons died from apoptosis consistent with the results of TUNEL histological examination. When the rats were administrated with protodioscin according to the experimental scheme, these changes induced by I/R were significantly ameliorated and restored towards their normal level. This finding implied that the maintaining the physiological balance between Bcl-2 and Bax is possibly another anti-apoptotic effect of protodioscin.

Accumulating researches have demonstrated that over-release of inflammatory cytokines in I/R, and subsequent secondary inflammatory response is a dominant event during the development of brain injury and deterioration. Numerous inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 are involved in the course of the I/R injury to form an inflammatory cascade event [34]. Due to poor permeability of vascular endothelial cells and over-expressing cell adhesion molecules, TNF-α secreted by macrophages can stimulate the infiltration of polymorphonuclear leukocytes and enhance the release of inflammatory mediators, which finally contribute to pathogenetic development induced by I/R [35, 36]. IL-1β, another momentous factor in inflammation, activates both B and T cells via synergying with other cytokines and promotes the adhesion of leukocytes to corresponding endothelial cells via producing other inflammatory cytokines [37]. Moreover, it could also regulate the expression of TNF-α. Infusion with protodioscin prior to executing the I/R alleviated the increase in concentrations of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in the rat serum, indicating that the excellent neuroprotection of protodioscin against I/R injury might be attributed to its anti-inflammatory action through the prevention of over secretion of related inflammatory cytokines.

Nuclear factor κappa B (NF-κB) acting in a signal transduction pathway is participating in the amplification and continuation of inflammatory and apoptotic responses [38]. NF-κB mainly composed of p50 and p65 subunits (the latter was selected to represent the NF-κB protein expression in the current research by western blotting analysis) is usually located in the cytoplasm and remains inactive in a complex form combined with this inhibitory binding protein IκBα [39]. Once the cells are stimulated by internal or external stimuli such as I/R, IκBα will be phosphorylated in its specific sites of amino acid parts. This phosphorylation leads to the degradation of IκBα, and NF-κB dissociated from this complex becomes activated [40]. The released subunit of P65 is translocated from the cytosol to the nucleus where it is adsorbed with response elements (particular DNA sequence), and activates target responsive genes, such as cytokines and related mediators to promote their transcription [41, 42]. These final transcriptional products are involved in the inflammation and apoptosis, ultimately aggravating the I/R brain injury and further enhancing NF-κB activation. Protodioscin could increase the expression of IκBα in cytoplasm and block the movement of NF-κB from cytoplasm to nucleus in the injured right brain of rats, which was consistent with the low expression levels of NF-κB in the nucleus. This inhibits the activation of NF-κB signal pathways to attenuate the neuron damage of rats underwent with MCAO, and this seems to be another mechanism of the protodioscin activity to protect the brain from I/R injury.

Steroid saponins isolated from Dioscorea, Costus, and Trigonella have been extensively studied in the past. It was found that they improve coronary blood flow, facilitate peripheral circulation, suppress platelet aggregation, and lower blood cholesterol as well as triglyceride [43]. Due to these biological activities, some drugs such as Dunyeguanxinning Tablet and Di’aoxinxuekang Capsules made from steroid saponins of D. zingiberensis and Dioscorea nipponica Makino, respectively, are widely used to cure cardiovascular diseases for many years in China [44]. In addition, they display many other promising pharmaceutical effects such as anti-inflammatory, anti-thrombosis, and anti-tumor according to modern pharmacological researches [45]. Stroke treatments are recently performed with drugs with three different pharmaceutical mechanisms, namely thrombolytic prevention, anti-platelet drugs (Acetylsalicylic acid), and oral anti-coagulation (Warfarin). Protodioscin indeed protects the brain from the I/R injury on the experimental rats, although many studies about these aforementioned bioactivities other than its anti-tumor effect are not yet confirmed. After oral administration protodioscin or its aglycone could enter the neurons through the cell membrane and take the pharmacological effect by influencing the activities of Caspase-3, Bcl-2, Bax, and the NF-κB signal pathways. According to the previous reports [46, 47], aglycone i.e. diosgenin has been proved to possess anti-inflammatory effects to inhibit the release of some inflammatory cytokines through inactivation of the NF-κB signal pathways. They probably never enter the cells, but are combined with responsive receptors existed on the outer cell membranes, and the associated intercellular signal pathways are triggered via transforming conformation of receptors to cause the final positive effect. Of course, the above-discussion is just a speculation, and subsequent detailed experiments should be further carried out before its verification.

In conclusion, the observed phenomenon in the current study clarified that administration with protodioscin in vivo satisfactorily exhibited pharmacological effects on the rat model of transient cerebral ischemia-reperfusion induced by MCAO. It is suggested that neuroprotection was effected by intervening the activation of NF-κB signal pathways to suppress the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6. The underlying mechanisms were attributed to its anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects. Therefore, our efforts provided the valuable possibility that protodioscin could become a novel drug for the treatment of I/R injury in clinical use in the near future due to its potential and robust therapeutic properties.

Figure 4:

The flow diagram of isolating pure protodioscin from the extracts with a series of chromatographic technologies.

Phase I: The extracts were separated on silica gel column (particle size in 100~160 mesh), and eluted with the solvent system composed of dichloromethane-methanol-Water (the lower layer of this system) at various ratios under a gradient mode. Phase II: The fraction after elution at the ratio of 8:3:1 in previous step was further separated on silica gel column (particle size in 200~300 mesh), and used the solvent system at the same ratio of 8:3:1 again. Phase III: The obtained Frac. A after phase II was loaded on semi-preparative HPLC DAC-HB50 C18 (450 mm×50 mm, 10 μm) and successively separated under the mobile phrase of acetonitrile-water. The ratios in this graph were all the ratios of volumes.

Protodioscin was obtained with combined traditional and modern separation methods.

Protodioscin alleviated ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) cerebral injury on animal mode.

Anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptosis were its underlying mechanisms.

The neuroprotection of protodioscin was mediated by inactivating NF-κB pathways.

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by Scientific Research Supporting Project for New Teacher of Xi’anjiaotong University (NO. 1191320023) and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (First-class). The authors sincerely thank the Guge Biological Technolog y Co., Ltd (Hubei, China) for the analysis of various indicators, such as Nissl staining, determination of the inflammatory cytokines, and Western blotting.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

Reference

- 1.Truelsen T, Ekman M, Boysen G. Cost of stroke in Europe. Eur J Neurol 2005; 12: 78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deb P, Sharma S, & Hassan KM. Pathophysiologic mechanisms of acute ischemic stroke: An overview with emphasis on therapeutic significance beyond thrombolysis. Pathophysiology, 2010; 17: 197–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donnan CA, Fisher M, Macleod M, Davis SM. Stroke. Lancet 2008; 371: 1612–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ringelstein EB, Nabavi DG. Cerebral small vessel diseases: cerebral microangiopathies. Curr. Opin. Neurol 2005; 18: 179–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’ Brien JT, Erkinjuntti T, Reisberg B, Roman G, Sawada T, et al. Vascular cognitive impairment. Lancet Neurol. 2003; 2: 89–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou XQ, Zeng XN, Kong H, Sun XL. Neuroprotective effects of berberine on stroke models in vitro and in vivo Neurosci. Lett. 2008; 447: 31–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feigin VL, Lawes CMM, Bennett DA, Barker-Collo SL, Parag V. Worldwide stroke incidence and early case fatality reported in 56 population-based studies: a systematic review. Lancet Neurol. 2009; 8: 355–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong CH, Crack PJ. Modulation of neuro-inflammation and vascular response by oxidative stress following cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. Curr. Med. Chem 2008; 15: 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehta SL, Manhas N, Raghubir R. Molecular targets in cerebral ischemia for developing novel therapeutics. Brain Res. Rev 2007; 54: 34–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaushal V, Schlichter LC. Mechanisms of microglia-mediated neurotoxicity in a new model of the stroke penumbra, J. Neurosci 2008; 28: 2221–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gursoy-Ozdemir Y, Can A, Dalkara T. Reperfusion-induced oxidative/nitrative injury to neurovascular un it after focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke 2004; 35: 1449–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doyle KP, Simon RP, Stenzel-Poore MP. Mechanisms of ischemic brain damage. Neuropharmacology 2008; 55: 310–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng YD, Al-Khoury L, Zivin JA. Neuroprotection for ischemic stroke: two decades of success and failure. NeuroRx 2004; 1: 36–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Micieli G, Marcheselli S, Tosi PA. Safety and efficacy of alteplase in the treatment of acute ischemic stroke. Vascular Health Risk Manag 2009; 5: 397–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young AR, Ali C, Duretete A, Vivien D. Neuroprotection and stroke: time for a compromise. J. Neurochem 2007; 103: 1302–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bariyal S, Shah S, Gulati A. Neuroprotective and anti-apoptotic effects of liraglutide in the rat brain following focal cerebral ischemia. Neuroscience 2014; 281: 269–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qiu LL, Niu H, Huang W. Ultrasonic and fermented pretreatment technology for diosgenin production from Diosorea zingiberensis C.H. Wright. Chem Eng Res Des 2011; 89: 239–47. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang TJ, Liu ZB, Li J, Zhong M, Li JP, et al. Determination of protodioscin in rat plasma by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B 2007; 848: 363–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Longa EZ, Weinstein PR, Carlson S, Cummins R. Reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion without craniectomy in rats. Stroke 1989; 20: 84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murakami K, Kondo T, Kawase M, Li Y, Sato S. Mitochond rial susceptibility to oxidative stress exacerbates cerebral infarction that follows permanent focal cerebral ischemia in mutant mice with manganese superoxide dismutase deficiency. J. Neurosci 1998; 18: 205–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ueda H, Fujita R. Cell death mode switch from necrosis to apoptosis in brain. Biol. Pharm. Bull 2004; 27: 950–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barone FC. Ischemic stroke interve ntion requires mixed cellular protection of the penumbra. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs 2009; 10: 220–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaushal V, Schlichter LC. Mechanisms of microglia-mediated neurotoxicity in a new model of the stroke penumbra. J. Neurosci 2008; 28: 2221–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lulli M, Di Gesualdo F, Witort E, Pessina A, Capaccioli S. Cell death: physiopathological and therapeutic implications. Cell Death Dis 2010; 1: e30. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beilharz EJ, Williams CE, Dragunow M, Sirimanne ES, Gluckman PD. Mechanisms of delayed cell death following hypoxic-ischemic injury in the immature rat: evidence for apoptosis during selective neuronal loss. Mol Brain Res 1995; 29: 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Faubel S, Edelstein CL. Caspases as drug targets in ischemic organ injury. Current Drug Targets-Immune, Endocrine & Metabolic Disorders 2005; 5: 269–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Degterev A, Boyce M, Yuan J. A decade of caspases. Oncogene 2003; 22, 8543–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nicholson DW, Ali A, Thornberry NA, Vaillancourt JP, Ding CK. Identification and inhibition of the ICE/CED-3 protease necessary for mammalian apoptosis. Nature 1995; 376, 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bai Y, Zhang SY, Ren J, Yang YM, Liu M. Panax notoginseng saponins injection in treatment of cerebral infarction with a multicenter studies. Chinese Journal of New Drugs and Clinical Remedies 2001; 20: 257–9. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Korsmeyer SJ, Shutter JR, Veis DJ, Merry DE, Oltvai ZN. Bcl-2/Bax: a rheostat that regulates an anti-oxidant pathway and cell death. Semin. Cancer Biol 1993; 4: 327–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oltvai ZN, Milliman CL, Korsmeyer SJ. Bcl-2 hetero-dimerizes in vivo with a conserved homolog, Bax, that accelerates programmed cell death. Cell 1993; 74: 609–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Polster BM, Fiskum G. Mitochondrial mechanisms of neural cell apoptosis. J Neurochem 2004; 90: 1281–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao H, Yenari MA, Cheng D, Sapolsky RM, Steinberg GK. Bcl-2 overexpression protects against neuron loss within the ischemic margin following experimental stroke and inhibits cytochrome c translocation and caspase-3 activity. J Neurochem 2003; 85: 1026–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benveniste EN. Inflammatory cytokines within the central nervous system: sources, function, and mechanism of action. Am. J. Physiol 1992; 263: C1–C6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cyktor JC, Turner J. IL-10 and immunity against prokaryotic and eukaryotic intrace llular pathogens. Infect Immun 2011; 79: 2964–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sairanen T, Carpen O, Karjalainen-Lindsberg ML. Evolution of cerebral tumor necrosis factor-alpha production during human ischemic stroke. Stroke 2001; 32: 1750–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vakili A, Mojarrad S, Akhavan MM, Rashidy-Pour A. Pentoxifylline attenuates TNF-α protein levels and brain edema following temporary focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Brain Res 2011; 1377: 119–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Campbell KJ, Perkins ND. Regulation of NF-κappaB function, Biochem. Soc. Symp 2006; 73: 165–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kassed C, Willing A, Garbuzova-Davis S, Sanberg P, Pennypacker K. Lack of NF-κB p50 exacerbates degeneration of hippocampal neurons after chemical exposure and impairs learning. Exp. Neurol 2002; 176: 277–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Belayev L, Alonso OF, Busto R, Zhao W, Ginsberg MD. Middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat by intraluminal suture, neurological and pathological evaluation of an improved model. Stroke 1996; 27: 1616–22 discussion 1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ridder DA, Schwaninger M. NF-κB signaling in cerebral ischemia. Neuroscience 2009; 158: 995–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qiao H, Zhang X, Zhu C, Dong L, Wang L. Luteolin downregulates TLR4, TLR5, NF-j B and p-p38MAPK expression, upregulates the p-ERK expression, and protects rat brains against focal ischemia. Brain Res. 2012b; 1448: 71–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun Q, Ju Y, Zhao Y. Steroid saponins with biological activities. Chinese Traditional and Herbal Drugs 2002; 33: 276–80. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu Z, Zou W, Wang R, Zhou Z. Clinical application of Di’ao Xin Xue Kang capsule for ten years in China. China Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Pharmacy 2004; 19: 620–2. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sparg SG, Light ME, Staden JV. Biological activities and distribution of plant saponins. J Ethnopharmacol 2004; 94: 219–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jung DH, Park HJ, Byun HE, Park YM, Kim TW, et al. Diosgenin inhibits macrophage-derived infl ammatory mediators through downregulation of CK2, JNK, NF-κB and AP-1 activation. Int. Immunopharmacol 2010; 10: 1047–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Manivannan J, Shanthakumar J, Rajeshwaran K, Arunagiri P, Balamurugan E. Effect of diosgenin on cardiac tissue lipids, trace elements, molecular changes, TNF-α and IL-6 expression in CRF rats. Biomedicine & Preventive Nutrition 2013; 3: 389–92. [Google Scholar]