Level of Evidence:

Level V.

Keywords: total ankle arthroplasty (TAA), anterior approach, modified anterolateral approach, wound healing

Introduction

Total ankle arthroplasty (TAA) is one of the novel procedures to reconstruct a destructive ankle joint, but delayed wound healing is one of the most frequent and problematic complications after TAA with the conventional anterior approach. 3,4 In particular, once the retinaculum of the compartment for the tibialis anterior (TA) tendon is opened, the bowstring phenomenon (pushing up the skin and/or retinaculum by the TA tendon) occurs, seriously delaying wound healing. 3 Furthermore, tenomodulin (TNMD), which is a protein secreted from the tendon, is known to inhibit angiogenesis, and it is also considered to delay wound healing because of interference with vascularization in the dermal tissue directly above the exposed TA tendon. 14 Based on these factors, in this study, the anterolateral (Böhler’s) approach 1 was modified and used for TAA, because the skin incision is not placed directly above the TA/extensor hallucis longus (EHL) tendon, and the retinaculum around the TA tendon (superior and inferior subdivisions of the superomedial band of the inferior extensor retinaculum) was not opened. 8 Instead, the medial side of the inferior extensor (extensor digitorum longus [EDL]) retinaculum was opened. 1

Patients and Methods

A retrospective, observational study of 36 consecutive ankles receiving a mobile-bearing ankle prosthesis design (The FINE mobile-bearing prosthesis; Teijin-Nakashima Medical Co, Ltd, Okayama, Japan) 5 for treatment of end-stage ankle deformity or destruction from January 2019 to December 2020 was performed. Thirteen ankles underwent TAA with the conventional anterior approach, and the remaining 23 ankles underwent the modified anterolateral approach. Patients’ demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. This research was performed in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration, and it was approved by the institutional review board of the authors’ affiliated institutions. Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Table 1.

Patients’ Demographic Characteristics.a

| Conventional Anterior | Modified Anterolateral | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 13) | (n = 23) | ||

| Age, y, mean ± SD | 74.9 ± 7.7 | 74.9 ± 5.2 | .96 |

| Height, cm, mean ± SD | 150.8 ± 4.3 | 151.6 ± 6.7 | .92 |

| Body weight, kg, mean ± SD | 58.1 ± 5.8 | 53.8 ± 8.9 | .11 |

| Body mass index, mean ± SD | 25.6 ± 2.8 | 23.4 ± 3.6 | .06 |

| Gender, male/female, n | 1:12 | 3:20 | .62b |

| OA/RA, proportion, n | 9:4 | 14:9 | .62b |

| • SAFE-Q scores (preoperative) | |||

| Pain and pain-related (100) | 47.7 ± 19.4 | 50.4 ± 17.7 | .59 |

| Physical functioning and daily-living (100) | 35.5 ± 11.5 | 41.5 ± 15.9 | .90 |

| Social functioning (100) | 56.9 ± 9.8 | 48.6 ± 18.1 | .80 |

| General health and well-being (100) | 49.2 ± 21.9 | 50.8 ± 26.8 | .54 |

| Shoe-related (100) | 36.1 ± 11.4 | 47.2 ± 23.9 | .91 |

| • RA patients, n | 4 | 9 | – |

| RA disease duration, y, mean ± SD | 19.0 ± 1.7 | 19.0 ± 5.0 | .68 |

| Steinbrocker classification | |||

| Stage (no. of ankles) | |||

| III | 1 | 2 | |

| IV | 3 | 7 | |

| Functional class (no. of ankles) | |||

| I | 1 | 1 | |

| II | 3 | 7 | |

| III | 1 | ||

| Preoperative DAS28-CRP score, points, mean ± SD | 2.89 ± 0.25 | 2.26 ± 0.65 | .08 |

| Prednisolone usage, % | 0 | 44 | .008b |

| Prednisolone dosage, mg/d, mean ± SD | 0 ± 0 | 2.0 ± 2.3 | .09 |

| Methotrexate usage, % | 100 | 67 | .19b |

| Methotrexate dosage, mg/wk | 9.0 ± 1.73 | 4.9 ± 4.0 | .07 |

| Biologics or JAKi usage, % | 25 | 44 | .51b |

| Biologics or JAKi used (no. of ankles) | |||

| Abatacept | 1 | 2 | .28b |

| Tocilizumab | 1 | ||

| Etanercept | 1 | ||

| Baricitinib | 1 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; DAS28-CRP score, disease activity score of 28 joints–C reactive protein; JAKi, Janus kinase inhibitor; OA, osteoarthritis; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; SAFE-Q, self-administered foot evaluation questionnaire.

a Values are mean ± SD.

b Evaluation performed with use of chi-square analysis.

Operative Technique

Modified anterolateral approach

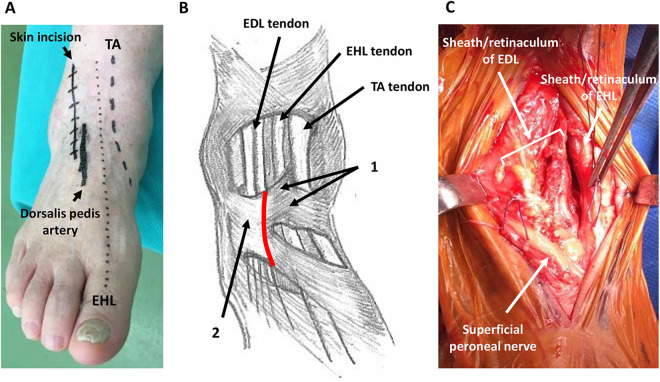

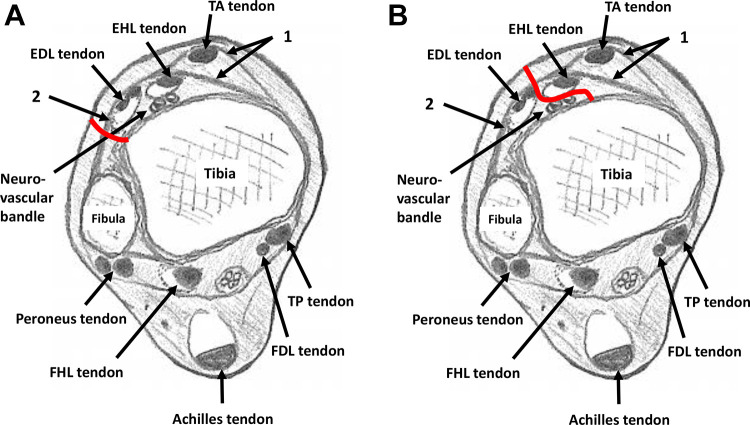

The skin incision was based on the conventional anterolateral approach/Böhler’s incision. 1 The incision was made one finger (1.5-2.0 cm) laterally from the EHL (Figure 1A), and then the superficial peroneal nerve was identified and retracted. The medial side of the stem of the inferior extensor retinaculum was opened without intervention to the superior and inferior subdivisions of the superomedial band of the inferior extensor retinaculum, which forms a tunnel for the TA tendon 8 (Figure 1B). The EDL was then retracted laterally, and the TA/EHL compartment was retracted medially (Figure 1C). The approach into the deep compartment was from the lateral side of the EDL in the original anterolateral approach (Figure 2A), but it was changed to the medial side of the EDL in the modified anterolateral approach (Figure 2B). The approach to fat tissue was continued, the medial malleolar artery was identified and ligated, and then the dorsalis pedis artery/vein and the deep peroneal nerve were retracted laterally as in the conventional anterior approach (Figure 2B).

Figure 1.

Preoperative, intraoperative photographs of the ankle. (A) Preoperative design of the skin incision. The skin incision is made 1.5 cm laterally from the EHL. (B) Illustration of retinaculum and tendons around ankle. 1: Superior and inferior subdivisions of the superomedial band of the inferior extensor retinaculum; 2: stem of inferior extensor retinaculum; red line: opening line of the retinaculum. (C) Intraoperative findings of the ankle after opening the retinaculum. The EHL and EDL tendons are covered by sheath and retinaculum. The TA tendon does not appear. Each side of the sheath and retinaculum is marked by threads.

Figure 2.

Axial illustration of the ankle. 1: Superior and inferior subdivisions of the superomedial band of the inferior extensor retinaculum; 2: stem of inferior extensor retinaculum. (A) Red line: approach route to tibia in original anterolateral (Böhler’s) approach; (B) red line: approach route to tibia in modified anterolateral approach. (FDL, flexor digitorum longus; FHL, flexor hallucis longus; TP, tibialis posterior.)

TAA and postoperative procedure

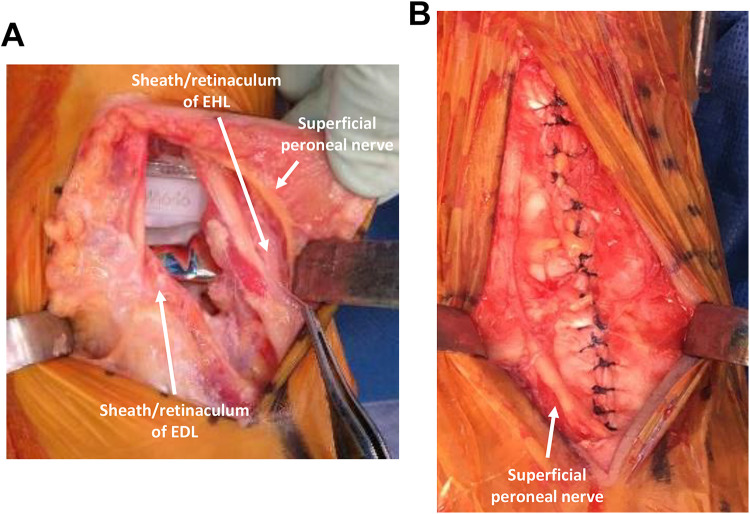

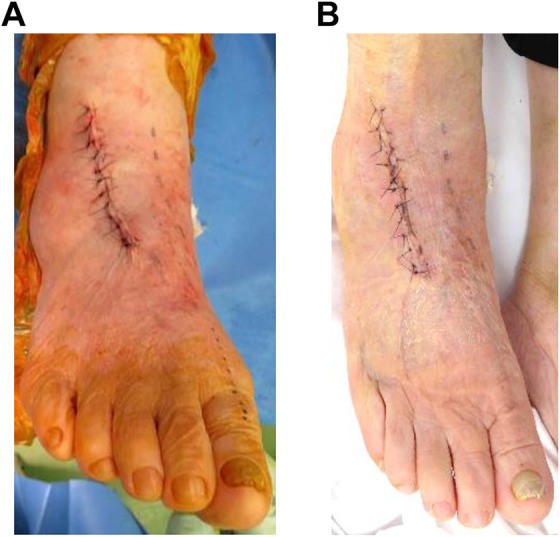

Surgery was carried out as described previously using mobile-bearing ankle prosthesis design (The FINE mobile-bearing prosthesis; Teijin-Nakashima Medical Co, Ltd, Okayama, Japan). 5 After preparation for tibia and talus implantation, medial malleolar lengthening osteotomy (preserving the periosteum) was added when tightness of the soft tissues was not acceptable. 2,5 Routine wound closure with careful suturing of the ankle joint capsule and extensor retinaculum was completed (Figure 3A, B). The subcutaneous layer was sutured with 3-0 absorbable thread, as much as possible. The skin layer was sutured with 4-0 Nylon vertical mattress sutures (Figure 4A).

Figure 3.

Intraoperative photographs of the ankle. (A) Intraoperative findings of the ankle after implantation of the prostheses. The superficial peroneal nerve appears in the subcutaneous tissue. The EHL and EDL tendons are still covered by the sheath and retinaculum. The TA tendon still does not appear. (B) Intraoperative findings after careful suturing of the sheath and retinaculum.

Figure 4.

Wound photograph after surgery. (A) Wound just after skin suturing. (B) Wound at 14 days after surgery. Healing is completed, and stitch removal has been performed.

The ankle was immobilized postoperatively in a below-knee cast for 2-3 weeks with nonweightbearing. The duration of casting was not changed if malleolar osteotomy was added, as in malleolar fracture cases, but when patients were allowed full weightbearing, it was with an attached ankle brace to avoid an ankle sprain. 5 Such intraoperative events mentioned above are described in Table 2. After suture removal was completed, range of motion exercise was started, and at the same time, gait exercise was also started.

Table 2.

Intraoperative Events.a

| Conventional Anterior | Modified Anterolateral | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 13) | (n = 23) | ||

| Medial malleolar osteotomy, % (n/n) | 77 (10/13) | 65 (15/23) | .46b |

| Lateral malleolar osteotomy, % (n/n) | 0 (0/13) | 4 (1/23) | .45b |

| Medial malleolar fracture, % (n/n) | 0 (0/13) | 9 (2/23) | .27b |

| Lateral malleolar fracture, % (n/n) | 8 (1/13) | 13 (3/23) | .62b |

| Gastrocnemius recession, % (n/n) | 46 (6/13) | 48 (11/23) | .92b |

| Concomitant subtalar joint | |||

| Talonavicular joint fusion, % (n/n) | 8 (1/13) | 9 (2/23) | .92b |

| Tourniquet time, min, mean ± SD | 109.6 ± 11.8 | 129.8 ± 15.4 | .02 |

a Values are mean ± SD.

b Evaluation performed with the use of χ2 analysis.

Clinical assessment

The number of days to stitch removal after TAA was recorded. Suture removal after TAA was considered to be done around 2 weeks after TAA with careful observation of the wound state (Figure 4B), 4 but if the skin edge was macerated and/or discharge continued, sutures were left, and the ankles were recasted for several additional days. Postoperative events including blister formation, eschar formation (width greater than 1 cm) on the wound, wound dehiscence, and exposure of the TA tendon were observed and recorded. Peri-incisional decreased sensation was also checked, because the superficial peroneal nerve was retracted during the operation. Range of motion of dorsiflexion and plantar flexion was also measured clinically only 1 month after surgery.

For cases of rheumatoid arthritis, disease activity was assessed using the disease activity score of 28 joints–C reactive protein (DAS28-CRP) score. 6 For the clinical assessment, patients completed a self-administered foot evaluation questionnaire (SAFE-Q) preoperatively and at the final follow-up. 9

Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± SD. The differences in the measured variables between 2 groups were analyzed with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test or Mann-Whitney U test, and χ2 test as appropriate using JMP 13 statistical analysis software (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). A P value less than .05 was considered significant.

Results

Postoperative Events Involving the Wound Site During Wound Healing

As shown in Table 3, blister formation was seen in both groups. Eschar formation (width greater than 1 cm) was also seen in both groups, but less frequently in the modified group (13%) compared with the conventional group (46%). TA exposure with wound dehiscence after removal of the stitch was seen only in the conventional group (in 1 patient), but in no ankles in the modified group. There was no evidence of deep infection in either groups. Peri-incisional decreased sensation was observed in 1 ankle in the modified group, but it disappeared within 5 months after the operation.

Table 3.

Postoperative Status of the Wound Site, Range of Motion of Ankle, and Clinical Outcomes.a

| Conventional Anterior | Modified Anterolateral | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 13) | (n = 23) | ||

| Blister formation, % (n/n) | 8 (1/13) | 9 (2/23) | .92b |

| Eschar formation (width >1 cm), % (n/n) | 46 (6/13) | 13 (3/23) | .03b |

| Wound dehiscence, % (n/n) | 8 (1/13) | 0 (0/23) | .18b |

| Exposure of TA tendon, % (n/n) | 8 (1/13) | 0 (0of 23) | .18b |

| Days of suture removal, d Deep infection, % (n/n) |

18.4 ± 1.8 0 (0/13) | 15.4 ± 2.3 0 (0/23) | .002 1b |

| Peri-incisional decreased sensation, % (n/n) | 0 (0/13) | 4 (1/23) | .45b |

| Range of motion 1 mo after surgery, degrees, mean ± SD | |||

| • Dorsiflexion | 13.1 ± 5.7 | 13.3 ± 6.5 | .84 |

| • Plantar flexion | 40.5 ± 4.6 | 38.3 ± 9.7 | .49 |

| • SAFE-Q scores at final follow-up, mean ± SD | |||

| Pain and pain-related (100) | 85.7 ± 19.3c | 78.7 ± 14.2c | .19 |

| Physical functioning and daily-living (100) | 67.9 ± 12.4c | 71.8 ± 6.0c | .17 |

| Social functioning (100) | 73.2 ± 14.6c | 79.2 ± 9.8c | .58 |

| General health and well-being (100) | 84.3 ± 13.5c | 82.0 ± 16.7c | .35 |

| Shoe-related (100) | 60.7 ± 16.6c | 66.7 ± 22.7c | .17 |

Abbreviations: SAFE-Q, self-administered foot evaluation questionnaire; TA, tibialis anterior.

a Values are mean ± SD.

b Evaluation performed with use of χ2 analysis.

c Significantly increased (improved) as compared with preoperative scores.

Number of Days to Suture Removal

The number of days to suture removal was significantly shorter in the modified group (15 days) compared with the conventional group (18 days). After removal, there was no wound dehiscence in the modified group (Table 3).

Range of Ankle Motion

There was no significant difference between groups in the range of ankle joint motion 1 month after surgery (Table 3).

Clinical Assessment

SAFE-Q scores showed no significant difference between groups preoperatively and at final follow-up. On the other hand, significant improvement of each score in SAFE-Q was seen in both groups after surgery (Table 3).

Discussion

In this study, some advantages of the modified anterolateral approach for TAA were expected as compared with the conventional approach, because the incision was not placed on the TA/EHL tendon, and the compartment of the TA tendon was not opened in this approach. Because the original anterolateral approach was thought to have the disadvantage of approaching the medial side of the plafond and medial malleolus (Figure 2A), the opening site of the retinaculum over the EDL and the approach route to tibia was changed to the medial side in this modified anterolateral approach (Figure 2B). There was no wound dehiscence with TA exposure in the modified group, and the number of days to suture removal was significantly shorter than the conventional group. The risk of splitting of the retinaculum and sheath of the TA tendon by the bowstring phenomenon was considered to be reduced, because the retinaculum around the TA tendon (superior and inferior subdivisions of the superomedial band of the inferior extensor retinaculum) was not opened. In addition, even if the retinaculum over the EDL suture became untied, exposure of the TA tendon would not occur. Subsequently, not only physical (bowstring phenomenon) but also biological (TNMD secretion from the TA tendon) adverse effects on subcutaneous tissue and/or skin would be decreased. As shown in Figure 1C and Figure 3A, the TA tendon did not appear during the operation. These points were considered to be advantages of the modified anterolateral approach. Results showing no significant difference of clinical assessment (SAFE-Q) after surgery was also a recommendable point for the modified anterolateral approach. Furthermore, although further radiographic evaluations would be required, there was no problem of the implantation in radiographic findings (Figure 5A, B) at present. Although appearance of eschar formation (width greater than 1 cm) was significantly reduced, blister formation was seen as in the conventional group. Blisters are defined as “skin bullae and blisters representing areas of epidermal necrosis with separation of the stratified squamous cell layer from the underlying vascular dermal layer by edema fluid.” 13 Furthermore, a blister on the skin is considered to be a pressure release mechanism, so that blister formation is one of the reactions to an abnormally high pressure in the subcutaneous compartment. 16 Malleolar osteotomy and fracture, as intraoperative events in this study (Table 2), also has the possibility of causing swelling of the ankle joint after surgery, and could induce an increase of pressure in the subcutaneous compartment. Then, even if the modified anterolateral approach was used for TAA, it is important to prevent a high-pressure state in the subcutaneous compartment after surgery. In order to do so, advanced rest, ice, compression, and elevation (RICE) treatment should be thoroughly performed after surgery. In addition, modification of drainage should also be discussed. In the near future, we aim to obtain better wound healing after TAA using the anterior approach with more advanced RICE treatment, a modified drainage system, and modified skin suturing. Limited tourniquet time is also recommended for wound healing after TAA, 4 and for preventing proteolytic activity in muscle tissue. 7 In the present study, the modified group showed significantly longer tourniquet time (Table 2), but fortunately, wound healing was faster in the modified group. If wound healing were improved more, active/passive range of motion exercise, Achilles tendon stretch, and gait exercise could be started earlier after TAA. Unfortunately, in the present study, no significant gain of ankle joint motion at 1 month after TAA was observed. However, Achilles tendon stretch exercises may be started during wound healing. Peri-incisional decreased sensation owing to retraction of the superficial peroneal nerve was seen in 1 case in the modified group. Fortunately, the symptom disappeared within 5 months after surgery, but retraction of the nerve should be gently performed to avoid this complication. In addition, greater care for wound healing is needed in rheumatoid arthritis cases. Chronic use of steroids and/or methotrexate is known to have the potential to suppress wound healing. 11,17 In the present study, although prednisolone usage was significantly higher in the modified group, wound healing was completed faster. In a systematic review, biologic use was not a risk factor for operative site infection or delayed wound healing, 12 but intraoperative and postoperative care for wound healing is important, because foot and ankle surgery in rheumatoid arthritis cases is a risk factor for delayed wound healing. 10,15 Although there were limitations of this study, discussion of the modified lateral-anterior approach should be done with more cases, with long-term follow-up, and with clinical assessment after TAA as the next step. However, the modified anterolateral approach has a potential to reduce the risk of poor wound healing after TAA with the anterior approach system. Subsequently, the possibility of operative site infection and deep infection should also be reduced. Furthermore, it is desirable that rehabilitation be started from the early phase after TAA.

Figure 5.

Radiograph at 3 months after surgery. This patient underwent TAA with a modified anterolateral approach. Concomitant medial malleolar osteotomy and gastrocnemius recession were also performed to control the soft tissue balance. After RICE treatment, suture removal was done at 13 days after surgery, then range of motion and gait exercises were started. Range of ankle joint motion was 20 degrees of dorsiflexion and 40 degrees of plantar flexion at 3 months after surgery. (A) Anteroposterior view of radiograph in the standing position (weightbearing). There is no problem in the state of implantation. Bone union after medial malleolar osteotomy is progressing. (B) Lateral view of radiograph in the standing position (weightbearing). There is no problem in the state of implantation. Posterior relocation of talar bone was completed. RICE, rest, ice, compression, and elevation.

In conclusion, the modified anterolateral approach may have advantages for wound healing after TAA using the anterior approach system. However, further investigation with a greater number of patients should be continued.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-fao-10.1177_24730114211013342 for Modified Anterolateral Approach for Total Ankle Arthroplasty by Makoto Hirao, Kosuke Ebina, Yuki Etani, Shoichi Kaneshiro, Hideki Tsuboi, Takaaki Noguchi, Gensuke Okamura, Yasuo Kunugiza, Hiroyuki Nakaya, Masataka Nishikawa, Shigeyoshi Tsuji, Koichiro Takahi, Hajime Owaki and Jun Hashimoto in Foot & Ankle Orthopaedics

Footnotes

Ethical Approval: Ethical approval for this study was obtained from Institutional Review Board of Osaka University Hospital (approval number: 14219) and National Hospital Organization, Osaka Minami Medical Center (approval number: 28-12).

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. ICMJE forms for all authors are available online.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Makoto Hirao, MD, PhD,  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1408-7851

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1408-7851

Supplemental Material: A supplemental video for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Crist BD, Khazzam M, Murtha YM, Della Rocca GJ. Pilon fractures: advances in surgical management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19(10):612–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Doets HC, van der Plaat LW, Klein JP. Medial malleolar osteotomy for the correction of varus deformity during total ankle arthroplasty. Results in 15 ankles. Foot Ankle Int. 2008;29(2):171–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Etani Y, Ebina K, Hirao M, et al. A report of three cases which required tibialis anterior tendon resection to recover delayed wound healing after total ankle arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Mod Rheumatol Case Rep. 2020;4(1):6–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gross CE, Hamid KS, Green C, Easley ME, DeOrio JK, Nunley JA. Operative wound complications following total ankle arthroplasty. Foot Ankle Int. 2017;38(4):360–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hirao M, Hashimoto J, Tsuboi H, et al. Total ankle arthroplasty for rheumatoid arthritis cases in Japanese patients: a retrospective study of mid to long-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Open Access. 2017;2(4):e00033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Inoue E, Yamanaka H, Hara M, Tomatsu T, Kamatani N. Comparison of Disease Activity Score (DAS) 28–erythrocyte sedimentation rate and DAS28–C-reactive protein threshold values. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(3):407–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jawhar A, Hermanns S, Ponelies N, Obertacke U, Roehl H. Tourniquet-induced ischaemia during total knee arthroplasty results in higher proteolytic activities within vastus medialis cells: a randomized clinical trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24(10):3313–3321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kelikian AS. Sarrafian’s Anatomy of the Foot and Ankle. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2011: chap. 5. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Niki H, Tatsunami S, Haraguchi N, et al. Validity and reliability of a self-administered foot evaluation questionnaire (SAFE-Q). J Orthop Sci. 2013;18(2):298–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Okita S, Ishikawa H, Abe A, et al. Risk factors of postoperative delayed wound healing in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with a biological agent. Mod Rheumatol. 2021;31(3):587–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pountos I, Giannoudis PV. Effect of methotrexate on bone and wound healing. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2017;16(5):535–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ramos-Petersen L, Nester CJ, Reinoso-Cobo A, Nieto-Gil P, Ortega-Avila AB, Gijon-Nogueron G. A systematic review to identify the effects of biologics in the feet of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Medicina (Kaunas). 2020;57(1):E23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shelton ML, Anderson RL. Complications of fractures and dislocations of the ankle. In: Epps CH, Jr, ed. Complications of Orthopaedic Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott; 1998: 599–648. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shukunami C, Yoshimoto Y, Takimoto A, Yamashita H, Hiraki Y. Molecular characterization and function of tenomodulin, a marker of tendons and ligaments that integrate musculoskeletal components. Jpn Dent Sci Rev. 2016;52(4):84–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tada M, Inui K, Sugioka Y, et al. Delayed wound healing and postoperative surgical site infections in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with or without biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35(6):1475–1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Varela CD, Vaughan TK, Carr JB, Slemmons BK. Fracture blisters: clinical and pathological aspects. J Orthop Trauma. 1993;7(5):417–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang AS, Armstrong EJ, Armstrong AW. Corticosteroids and wound healing: clinical considerations in the perioperative period. Am J Surg. 2013;206(3):410–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-fao-10.1177_24730114211013342 for Modified Anterolateral Approach for Total Ankle Arthroplasty by Makoto Hirao, Kosuke Ebina, Yuki Etani, Shoichi Kaneshiro, Hideki Tsuboi, Takaaki Noguchi, Gensuke Okamura, Yasuo Kunugiza, Hiroyuki Nakaya, Masataka Nishikawa, Shigeyoshi Tsuji, Koichiro Takahi, Hajime Owaki and Jun Hashimoto in Foot & Ankle Orthopaedics