Abstract

Background: Many jurisdictions globally have no specific prison policy to guide prison management and prison staff in relation to the special needs of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) prisoners despite the United Nations for the Treatment of Prisoners Standard Minimum Rules and the updated 2017 Yogyakarta Principles on the Application of International Human Rights Law in relation to Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity. Within LGBT prison groups, transgender people represent a key special population with distinct needs and rights, with incarceration rates greater than that of the general population, and who experience unique vulnerabilities in prisons.

Aims/Method: A scoping review was conducted of extant information on the transgender prison situation, their unique health needs and outcomes in contemporary prison settings. Fifty-nine publications were charted and thematically analyzed.

Results: Five key themes emerged: Transgender definition and terminology used in prison publications; Prison housing and classification systems; Conduct of correctional staff toward incarcerated transgender people; Gender affirmation, health experiences and situational health risks of incarcerated transgender people; and Transgender access to gender-related healthcare in prison.

Conclusions: The review highlights the need for practical prison based measures in the form of increased advocacy, awareness raising, desensitization of high level prison management, prison staff and prison healthcare providers, and clinical and cultural competence institutional training on transgender patient care. The review underscores the need to uphold the existing international mandates to take measures to protect incarcerated transgender people from violence and stigmatization without restricting rights, and provide adequate gender sensitive and gender affirming healthcare, including hormone therapy and gender reassignment.

Keywords: Health, LGBT, prison, scoping review, transgender, violence, trans, human rights

Background

A total of 10 million men, women and children are incarcerated across the world (Penal Reform, 2019), with almost a 20 percent increase observed between 2000 and 2015, despite the reduction in global crime trends (Penal Reform, 2018). The prison population is not homogeneous, with several key groups identified by the United Nations (UN) as having needs requiring special consideration within the prison setting. These include pretrial detainees, children in conflict with the law, women, people with disabilities, mental health needs, foreign nationals, people belonging to ethnic and racial minorities or indigenous communities, older people, those with drug dependence, terminal illness, and lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people (UNODC, 2009, 2016). LGBT prisoners are especially vulnerable in certain countries where same sex relationships are criminalized under sodomy laws or under the abuse of morality laws (International Commission of Jurists, 2006; WHO, 2014). Grant et al. (2011) found that 7% of their transgender sample had been held in a cell solely due to their gender identity. If the individuals were Black or Latino, the rates rose dramatically to 41% and 21%, respectively. Further to this, LGBT prisoners, which include sex workers, men who have sex with men, and transgender women housed in male prisons, have unique vulnerabilities exacerbated by the prison environment (Arnott & Crago, 2009; Baral et al, 2013; The Global Fund, 2017). They can be marginalized on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity, subjecting them to increased risk of violence, ill-treatment or physical, mental or sexual abuse by other prisoners as well as officers. The impact that this form of victimization can have on the prisoner can cause or exacerbate mental health issues leading to depression, suicide ideation, and the potential for auto-castration and auto-penectomy (Brown & McDuffie, 2009). Furthermore, there is a distinct increased risk and vulnerability between transgender and non-transgender prisoner vulnerabilities. For example in 2015–2016, 0.04% of the general US population experienced sexual assault in prison (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2020; United States Census Bureau, 2020; Wagner & Sawyer, 2018), whilst Grant et al. (2011) found that 38% of their transgender sample had been harassed during incarceration, 9% physically assaulted, and 7% sexually assaulted.

States are obliged to protect all prisoners under their care and supervision, in addition to supporting their social integration (UNODC, 2009). Many jurisdictions globally have no specific prison policy to guide prison management and prison staff in relation to the special needs of LGBT prisoners (UNODC, 2009). This is despite the 2016 Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (Nelson Mandela Rules) mandating prison administrations to “take account of the individual needs of prisoners, in particular the most vulnerable categories in prison settings” (Rule 2(2)) (United Nations General Assembly, 2016, p. 8). The 2006 and updated 2017 Yogyakarta Principles on the Application of International Human Rights Law in relation to Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity, principle 9 further mandates the right to treatment with humanity while in detention (International Commission of Jurists, 2007; Yogyakarta Principles, 2006). The extreme vulnerability of LGBT, especially transgender people, within closed settings requires dedicated policies to supporting their needs, encouraging social integration and prevent victimization (UNODC, 2009, 2016). Standards of care mandated in the Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, the Prison Elimination Act (PREA; Beck, 2015) and the 2017 Yogyakarta Principles as well as well-established research that will be analyzed in this paper such as Brown and McDuffie (2009), work to ensure that placement in detention avoids further victimization by identifying inadequacies in prison policies and providing human rights agendas that institutions can comply to. Furthermore, they advocate for the provision of adequate access to medical care and counseling appropriate to the needs of those in custody, recognizing any particular needs of persons on the basis of their sexual orientation or gender identity, including with regard to reproductive health, access to HIV/AIDS information and therapy, access to hormonal or other therapy, and access to gender-reassignment treatments where appropriate, as outlined in the World Professional Association for Transgender Healthcare Standards of Care (WPATH SOC; 2012) section XIV (UNODC, 2009, 2016).

We refer specifically to incarcerated transgender people in this review. Transgender is a term that “describes a diverse group of people whose internal sense of gender is different than that which they were assigned at birth” (WHO, 2020). It is not a diagnostic term and does not imply a medical or psychological condition or any specific form of sexual orientation. It is an umbrella term which includes a broad range of experiences and identities. It includes individuals who undergo medical treatment or are in the process of transitioning their physical appearance to conform to their internal gender identity, as well as those who live in accordance with their gender identity without seeking any medical treatment. As prisons are segregated by gender, the actual number of incarcerated transgender individuals across different countries is unknown (Clark et al., 2017). Two countries which document rates of transgender people in prisons are the United States (US) and the United Kingdom (UK). In the US, Grant et al. (2011), estimated that 16% of transgender individuals have been imprisoned at some point, in comparison to up to 0.7% of the whole US population (Prison Policy, 2020). In the UK, in 2016, 0.8% (n = 70) of incarcerated individuals reported being transgender (Ministry of Justice, 2016a). In 2018, this increased to 125 people across England and Wales (Reality Check Team, 2018) and then in 2019 it was reported that the figure had risen to 1,500 out of 90,000 (1.6%) of the general incarcerated population (Hymas, 2019).

Transgender health and social disparities even prior to detention or incarceration are well documented in the literature, and underpinned by their experience of pervasive stigma, humiliation, sexual assault, exploitation and violence, barriers to employment and housing, exclusion from legitimate economies and their participation in street economies (for example the sex work industry and drug dealing) (Fletcher et al., 2014; Grant et al., 2011; Nadal et al., 2012; Reback & Fletcher, 2014; White Hughto et al., 2015; Wilson et al., 2009). Garofalo et al. (2006) highlighted that 59% of their transgender women sample, reported a lifetime history of sex work. Reasons for this significance include economic hardship as a consequence of transphobic discrimination (Wilson et al., 2009), family rejection (Fuller & Riggs, 2018), and poor school attendance and dropout rates resulting from peer harassment (Grossman & D’Augelli, 2006). When transgender individuals then enter into sex work, they are at a significantly increased risk of acquiring HIV, as well as being arrested and detained (Brown & Jones, 2016; Poteat et al., 2014; 2015; Wilson et al., 2009).

Experiences of such prejudices are further amplified within the prison context (International Commission of Jurists, 2006; UNDP, 2013; WHO, 2014), as transgender individuals are vulnerable to sexual abuse and rape when they do not conform to gender expectation, and are also at risk of developing or exacerbating existing mental health issues, engaging in high risk substance use whilst inside, all of which compound their risk of self-harm and suicide (Bradford et al., 2013; Penal Reform, 2019; Stotzer, 2009; UNDP, 2013; UNODC, 2009, 2016; Yang et al., 2015). The hostile prison environment for transgender people also includes unsanitary and violent conditions that impede rehabilitation; widely used sanctions by prison staff against them, solitary confinement and forms of torture or degrading treatment (Penal Reform, 2019). The Association for the Prevention of Torture (APT) has identified a ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’ policy for LGBT people in prison settings, where they ‘render themselves invisible’, therefore allowing authorities to breach their human rights and deny their dignity, including in prisons (Blanc, 2018).

Given the increased recognition of transgender incarcerated people as a key population with specific needs and rights within the prison setting, we conducted a scoping review to extensively map extant literature on their prison situation, their unique health needs and outcomes in contemporary prison settings.

Method

Scoping reviews are a research synthesis which map literature on a particular topic or research area and provide an opportunity to identify key concepts and evidence to inform practice, policymaking, and technical guidance (Levac et al., 2010). They are particularly useful as they include a wide range of data across identified sources and designs, and are used to raise awareness, and inform policy and practice (Daudt et al., 2013; Levac et al., 2010). The underpinning research question for this scoping review was: ‘What is known in the literature about the health situation and health experiences of incarcerated transgender people?’ The term ‘prison’ was defined and adopted as representing facilities housing both on-remand transgender prisoners (including jails, police holding cells, and other detention centers) and convicted transgender prisoners representing facilities housing both on-remand young people and convicted adult prisoners (Van Hout & Mhlanga-Gunda, 2018).

The scoping review method is deemed rigorous and transparent in terms of its step by step protocol to identify and analyze all relevant available sources of information (Daudt et al., 2013; Levac et al., 2010). The five-stage iterative process was closely adhered to and consisted of (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting the data and (5) collating, summarizing and reporting the results (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005). Detailed search terms were subsequently generated by the team. The general search strategy is illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Search strategy.

| Search | Search terms |

|---|---|

| #1 | (Prison* OR detention* OR incarcerat* OR custod* OR jail OR gaol OR "correction* facilit*" OR "correction* setting*" OR “correction* service*” OR "detain* setting*" OR “Her Majesty* Prison” OR HMP OR probation OR confinement OR penitentiar* OR penal OR imprison*) |

| #2 | (Prisoner* OR detainee* OR offender* OR criminal* OR inmate* OR felon OR custodial OR cellmate* OR convict*) |

| #3 | (Transgender* OR “transgender men” OR transmen OR transman OR transmale OR “trans man” OR "trans men” OR “trans male” OR "transgender women" OR LGBT* OR trans OR "gender identit*" OR “trans* identit*” OR “Female to Male” OR “Male to Female” OR transsexual OR transexual OR transvestite OR intersex OR “gender reassignment” OR “sex reassignment” OR “gender minority” OR “sex change” OR “gender change” OR “gender dysphoria” OR transsexualism OR “gender identity disorder*”) |

| #4 | (Health OR “health situation” OR “health experience*” OR “health service*” OR “health service* availability” OR “health management” OR transphob* OR homophob* OR “quality* of life” OR “mental health”) |

The search was conducted using the university databases at Liverpool John Moores University, PubMed Clinical Queries and Scopus (exploratory search with selected references downloaded for the purpose of clarifying search terms). Comprehensive searches were subsequently conducted in the Web of Science, Medline, PsycINFO, Google and CINAHL, and restricted to the time period 2000–2019. The search was confined to the English language. In order to ensure full coverage of current knowledge and perspectives relating to incarceration and the transgender health experience, health management and situation in worldwide prisons; we included international and national policy briefs, handbooks, documents and reports, country situational assessment reports, conference proceedings, news reports, commentary pieces and editorials, in addition to empirical peer-reviewed scholarly literature.

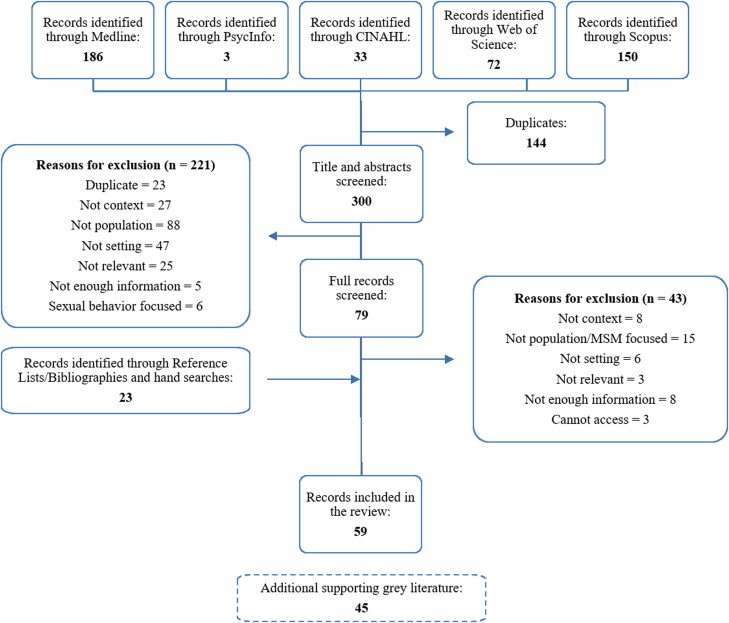

Citations were managed using the bibliographic software manager EndNote, with duplicates removed manually. Records included both reference to transgender people (male-to-female; female-to-male) and prison official perspectives in their management within prisons or other closed settings. Follow-up search strategies included hand searching of reference listings. Hand searches were conducted on international aid and development organizational websites, law enforcement, correctional, social, health, medical and human rights related databases, and websites of country governments and non-governmental bodies. Key LGBT and trans organization websites were also searched. Figure 1 reflects the screening and filtering process of the resulting studies.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of screening and filtering process.

All records warranting inclusion were procured for full text review. Eligibility criteria for inclusion in the review were based on whether citations mentioned transgender prisoners’ health experiences, unique transgender prison healthcare needs and healthcare outcomes or contained health related content directly relating to transgender people in prisons worldwide. Records were also excluded if the transgender population was solely under 18 years of age and found not to meet the eligibility criteria.

The remaining records were charted and thematically analyzed, as per scoping review protocols (Daudt et al., 2013; Levac et al., 2010). This involved the creation of a spreadsheet used to chart relevant data (data collection categories were the year of publication, author, location, method and aim, key guidance points). The team conducted a trial charting exercise of five records as recommended by Levac et al. (2010), followed by a joint consultation to ensure alignment with the scoping question and its purpose. Based on this preliminary exercise, the team developed prior categories which guided the subsequent extraction and charting of the data from the records. The charted data was analyzed and systematized by thematic manual coding, which organized the data, and structured it into themes through patterns in associated categories. Disagreements around theme allocation were resolved through team discussion.

Results

From the database and hand searches, 59 publications were included in the final sample (Figure 1). From the searches, we reviewed empirical studies (n = 23), commentaries (n = 23), literature reviews (n = 8), reports (n = 2), a book chapter, case study and a set of conference slides. The searches were not limited by country, yet only the US (n = 47), the UK (n = 6), Australia (namely the state of New South Wales; n = 3), Brazil, Canada, Hong Kong and Italy (n = 1), are represented (Table 2). Three articles focused on the global perspective, with some referring to more than one country. A further 45 documents were identified through grey literature searches and were used to inform the results as well as throughout the discussion (Table 3). Types of documents included reports (n = 23), legal rulings (n = 9), newspaper articles (n = 4), websites (n = 4), a bulletin, framework, guidelines, a policy document and a policy review (n = 1). Table 4 identifies results by country, highlighting the various policies and attitudes toward transgender rights in prison.

Table 2.

Article results from database and hand searches.

| Authors | Article details | Type | Location | Method and Gender Included (M2F & F2M) | Key Themes | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexander, R. and Meshelemiah, J. C. A. | Gender Identity Disorders in Prisons: What Are the Legal Implications for Prison Mental Health Professionals and Administrators? Prison J; 2010; 90 (3); pp. 269-286 | Journal article | US | A literature review of recent cases and lawsuits of both M2F & F2M |

|

The article focuses on transgender case law in the US. In most cases cited, the discourse focuses on GD and if it is a mental disorder. Guidelines provided by WPATH SOC, state that mental health professionals should evaluate and counsel individual’s around treatments options and then determine eligibility for hormone treatment or SRS. One of the main issues in the US is the restrictive insurance policies, which will not cover SRS. Due to this, WPATH SOC state that SRS should only be considered when ‘medically necessary’. In the courts the term ‘medically necessary’ is regularly disputed with claims made that denial of a basic level of specialized care, is viewed as a violation of the Eighth Amendment. |

| Bacak, V., Thurman, K., Eyer, K., Qureshi, R., Bird, J. D. P., Rivera, L. M. and Kim, S. A. | Incarceration as a Health Determinant for Sexual Orientation and Gender Minority Persons; Am J Public Health; 2018; 108 (8) pp. 994-998 | Commentary | US | Both M2F & F2M |

|

Authors comment on how transgender inmates should be considered based on how they self-identify as they have unique health risks in correctional facilities that other inmates do not have. Authors note however, if they self-identify as a sexual minority in prison, they are at an even higher risk of harm or victimization. Authors highlight the need for additional mental health support before and after incarceration for transgender people, with focus on social support and sexual and gender minority communities. The paper stresses the obstacles faced with many prisons refusing access to transition-related care. Authors discuss the problem with housing based on inmates’ birth sex or external genitalia, noting an increased risk to mental and physical health. Authors argue inmates should be assigned based on their chosen gender identity. |

| Bashford, J., Hasan, S. and Marriott, C. | Inside Gender Identity: A report on meeting the health and social care needs of transgender people in the criminal justice system (2017) | Report | UK | Cross sectional survey Research. Data collected using Interview, documents/records; analyzed using thematic analysis both M2F & F2M |

|

Report highlights transgender populations experience high levels of stigma, discrimination, victimization and harassment. With prison staff overlooking transphobic. Males prisons, place of isolation and fear, with inmates at an increased risk of self-harm and suicide. Transgender inmates are not only treated unfairly by other inmates but also by professionals and the wider criminal justice system. The report finds reluctance among healthcare professionals to prescribe hormone therapy. Report highlights consequences hormone withdrawal including higher likelihood of auto-castration, depression, dysphoria or suicide. Some UK prisons allow transgender inmates to pursue gender affirmation by accessing clothing, makeup and prosthetics, others have found it more difficult. While some prisons in UK allocate to preferred gender prison, others are still determined by birth gender. Lack of knowledge around transgenderism is cause. |

| Beckwith, C., Castonguay, B. U., Trezza, C., Bazerman, L., Patrick, R., Cates, A., Olsen, H., Kurth, A., Liu, T., Peterson, J. and Kuo, I. | Gender Differences in HIV Care among Criminal Justice-Involved Persons: Baseline Data from the CARE + Corrections Study; PLoS One; 2017; 12 (1); p. e0169077 | Journal article | US (Washington) | N = 110 Self-reported adult HIV + ve inmates. Data collected computer-assisted personal interview and blood samples; analyzed using inferential statistics considered M2F only |

|

The study found transgender women were more likely to have a healthcare provider prior to incarceration compared to men and women. Given this, they were more likely to have participated in drug treatment programs than men (90% versus 61%) and women (90% versus 50%). More impressively, 94.7% (n = 18/20) of transgender women took HIV treatment during incarceration and at baseline, 80% of transgender women achieved HIV viral suppression (<200 copies/mL). |

| Beckwith, C. G., et al., | Risk behaviors and HIV care continuum outcomes among criminal justice-involved HIV-infected transgender women and cisgender men: Data from the Seek, Test, Treat, and Retain Harmonization Initiative; PLoS One; 2018; 13 (5); p. e0197729 | Journal article | US (Washington; California; Illinois) | Retrospective study pooling data from three US studies. inferential statistics used to analyze data, using only M2F sample |

|

Analysis found risky behavior in population including, 42% of transgender women classified as hazardous drinkers and more likely to report crack and cocaine use compared to general population (40% and 16% respectively), more likely to use multiple (more than two) substances (74% vs. 62%). They reported higher rates of condomless sex (58%) than the general population (64%) and they were significantly more likely to have more than one sexual partner. Although riskier sexual behaviors, there was no difference between transgender women and the general population in taking ART or in regard to adherence, achieving viral suppression or lowered CD4 counts. |

| Brömdal, A., Clark, K. A., White Hugho, J. M., Debattista, J., Tania M. Phillips, T. M., Mullens, A. B., Gow, J. and Daken, K. | Whole-incarceration-setting approaches to supporting and upholding the rights and health of incarcerated transgender people; International Journal of Transgenderism; 2019; 20 (4); pp. 341-350 | Journal article | Global | Review and recommendations. Both M2F & F2M |

|

Editorial reviewing existing literature, providing a key set of recommendations and calling for a ‘whole-incarceration-setting approach’ to support incarcerated transgender people. The article describes the global incarceration of transgender populations; lived experiences of incarcerated transgender people; violence, abuse, and harassment toward incarcerated transgender people; lack of adequate gender-affirming medical care; solitary confinement and prolonged “protective custody”; health consequences of discrimination and violence for incarcerated transgender people and the whole-incarceration-setting approach. |

| Brömdal, A., Mullens, A. B., Phillips, T. M. and Gow, J. | Experiences of transgender prisoners and their knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding sexual behaviors and HIV/STIs: A systematic review; Int J Transgend; 2019; 20 (1); pp. 4-19 | Journal article | Global | Scoping review. Data collected using narrative analysis and document/records. Analyzed using Thematic Analysis of both M2F & F2M |

|

The article reports on the sexual and violent assaults of transgender inmates, assaults reported when sexual advances were turned down and examples of homophobic discrimination from other inmates. Plus, experiences of interpersonal violence, including sexual assault, lack of respect and sensitivity, discrimination, mistreatment, harassment, or stigma from prison staff. Impact of such experiences are significant. HIV-infected report hiding HIV medications or transgender status to protect self. Vulnerability and heightened mental health issues associated with self-treatment, self-harm and sometimes suicide. An example of self-castration was observed as a means to cope with gender dysphoria. High levels of transactional condomless sex. Lack of general medical assessment and treatment including HIV care management and gender affirming care, with challenges to accessing medication and treatment also being discussed. Lack of knowledge and understanding regarding gender diversity and how gender identity and expression is related to yet distinct from sexual orientation was also reported. Transgender inmates housed in specific units as they were deemed 'at risk'. This was a designated are for men who have sex with men and transgender women only in a men’s central jail to ensure their safety from the male general population. |

| Brown, G. R. | Recommended Revisions to the World Professional Association for Transgender Health's Standards of Care Section on Medical Care for Incarcerated Persons with Gender Identity Disorder; Int J Transgend; 2009; 11 (2); pp. 133-138 | Commentary | US | Discussion relating to M2F & F2M |

|

Author discusses significant levels of depression, exacerbation of other mental illnesses, sexual and violent abuse as well as suicides. The authors argue treatment should be tailored to the individual but note current lack of access to healthcare (consequences include mental illnesses, suicidal thinking and behavior, auto-castration and/or auto-penectomy). Authors note some institutions base housing arrangements on the appearance of external genitalia rather than considering the gender role, thus causing greater distress to the inmate. |

| Brown, G. R. | Autocastration and autopenectomy as surgical self-treatment in incarcerated persons with gender identity disorder; Int J Transgend; 2010; 12 (1); pp. 31-38 | Journal article | US | Content analysis of three written accounts of M2F inmates |

|

The article outlines the journey of three transgender inmates who displayed gender dysphoria symptoms, mental health issues and requested evaluation for gender identity disorder. A result of failure to evaluate, diagnose and treat the inmates resulted in hunger strikes, being moved to maximum security prison to access services, access transition related treatment continued to be denied, resulting in all three inmates self-treating with auto-castration. Following this, one inmate was treated for comorbid conditions including psychosis, another eventually transferred and given hormones, another placed in solitary confinement on suicide watch. Following litigation, one has been allowed cross-sex hormone therapy and was able to gender affirm but still denied access to GD treatment. |

| Brown, G. R. | Qualitative analysis of transgender inmates' correspondence: implications for departments of correction; J Correct Healthcare; 2014; 20 (4); pp. 334-341 | Journal article | US | N = 129 documents and records of both M2F & F2M transgender prisoners analyzed thematically |

|

Findings include 42% of inmates reported abuse while in prison, with '23% reporting physical abuse or harassment and 19% relating that they had been sexually mistreated or abused by other inmates, corrections officers (COs), or both'. One inmate was allowed to have sex-reassignment surgery and 14% used hormone therapies. However, access to transgender healthcare is limited, leading to 2% having attempted and 3% completing auto-castration. |

| Brown, G. R. and McDuffie, E. | Health care policies addressing transgender inmates in prison systems in the US; J Correct Healthcare; 2009; 15 (4); pp. 280-290 | Journal article | US | N = 46 Department of Correctional documents and reports and were thematically analyzed; Thematic Analysis to consider both M2F & F2M |

|

Findings detail three different options available for transgender inmates in relation to hormone therapy: the continuation of hormones for inmates, ‘‘freeze-frame’’ or initiation of hormonal treatment de novo under appropriate clinical circumstances. Most inmates were able to continue to use hormones as this required extensive documentation proving diagnosis and existing care pathway. However, only one state did not rule out sex reassignment surgery as a treatment option in prisons. Illinois states that the prison system will allow it but only under extreme circumstances. Due to this, auto-castration was observed and reported by the authors. furthermore, 12 (71%) states base housing on external genitalia with only four states having more lenient policies based on sexual orientation. |

| Chianura, L.., Di Salvo, G., and Giovanardi, G. | Clandestine transgender female convicts in Italian detention centers: a pilot inquiry; Ecol della Mente; 2010; 33; 219-238 | Journal article | Italy; Brazil | Discussion relating to M2F & F2M |

|

The article, cited by Hochdorn et al. (2018), states that Italy has protected sectors for transgender inmates which has 'improved the situation either of the transgender prisoners, who suffered less violence and discrimination, or of the prison workers, who received special courses for interacting in an appropriate manner with these inmates'. It takes a systemic approach, discussing a binary system to housing and gender identification. Some form of rehabilitation services available to Italian transgender inmates, with particular reference to drug and alcohol use. These changes are highlighted to originate from the 1980s onwards that look to 'humanise the penitentiary system'. Training programs are offered to staff to understand the situation (Hochdorn et al. 2018) |

| Clark, K. A., Hughto, J. M. W. and Pachankis, J. E. | What's the right thing to do? Correctional healthcare providers' knowledge, attitudes and experiences caring for transgender inmates; Soc Sci Med; 2017; 193; pp. 80-88 | Journal article | US (New England) | N = 20 practitioners using Grounded Theory and analyzed using Thematic Analysis M2F & F2M |

|

The article reported that gender affirmation was unacceptable due to lack of transgender training and therefore confusion among staff; lack of knowledge/experience, prison culture, clinical incompetency, and personal bias. Clinical incompetency was largely seen through mental health issues with GD and custody staff biases toward healthcare and transgender inmates. Treatment ceased for inmates without documentation when inmates entered prison. Healthcare budget explanation for lack of treatment. |

| Coleman, E., Bockting, W., Botzer, M., Cohen-Kettenis, P., DeCuypere, G., Feldman, J., et al. | Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, version 7; 2012; Int. J. Transgenderism; 13: 165-232 | Commentary | US | Discussion relating to M2F & F2M |

|

Whilst there is no direct mention of prisons, the commentary draws on the WPATH SOC. The main points include the need for more understanding and evidence-based from across the world as currently sources used to inform the SOC are predominantly from North America and Western Europe; discussion on the definition of gender dysphoria and therefore evaluation and diagnosis as well as wider treatment options. |

| Colopy, T. W. | Setting gender identity free: expanding treatment for transsexual inmates; Health Matrix Clevel; 2012; 22 (1); pp. 227-271 | Commentary | US | Discussion relating to M2F & F2M |

|

Authors discuss literature regarding high levels of reported sexual and violent assault and need for inmates to receive a continuation of treatment. Authors note how inmates diagnosed after incarceration should also be provided with treatment and while other treatment options are available, these do not necessarily lead to 'adequate care'. Authors note need for healthcare professional training to effectively evaluate, assess and provide 'sound medical diagnosis without discrimination.' Often officers have full discretion on the treatment of inmates, this is an issue due to bias or inappropriate reasoning. Authors call for more appropriate prison officials to act as decision makers and to house inmates on their subjective gender rather than their physical sex, although the risks are noted. Alternatively a more progressive (but controversial) strategy would be to have transgender specific prisons. |

| Culbert, G. J. | Violence and the perceived risks of taking antiretroviral therapy in US jails and prisons; Int J Prison Health; 2014; 10 (2); pp. 94-109 | Journal article | US (Illinois) | Ethnography of N = 42 HIV-infected male and male to-female transgendered adults. Data analyzed using Thematic Analysis |

|

The study found more than a third of transgender inmates were diagnosed with HIV in prison. Some did not disclose their status for the entirety of their sentence as HIV disclosure was seen by officers as a bid for special treatment. Thus, treatment was not provided. Nearly half initiated ART while in prison. However, many reported missing doses or sustained treatment interruptions lasting weeks or months due to delayed prescribing, out-of-stock medications, and intermittent dosing. Those diagnosed in prison reported suicidal thoughts increased violence widespread stigma and homophobia. Numerous institutional barriers were reported to accessing HIV care including 'physical isolation, interpersonal violence, actions for controlling violence, CO apathy or unwillingness, and fees for health services'. |

| Disspain, S., Shuker, R. and Wildgoose, E. | Exploration of a transfemale prisoner’s experience of a prison therapeutic community; Prison Serv. J; 2015; 219, 9-18. | Case study | UK | Discussion relating to M2F & F2M |

|

The case study discusses the role of prison therapeutic communities (TC). Literature highlights high levels of assault, lack of knowledge from officers, sexual violence and overall bias. Little evidence of delivering treatment to offenders. Four elements to TG inmates situation: identity, understanding, openness and coping at the TC. We need to bridge the gap between supporting needs and knowing how to practically. TCs allowed a positive experience to engage with situation and treatment. |

| Drakeford, L. | Correctional Policy and Attempted Suicide Among Transgender Individuals; J Correct Healthcare; 2018; 24 (2); pp. 171-181 | Journal article | US | Cross-sectional survey of N = 500 organizations, Inferential statistics used to analyze data of M2F & F2M |

|

The study reports states which provide high levels of transgender-related medical services were significantly less likely to report their transgender inmates attempting suicide. Yet, there was a strong correlation between gender-based victimization and lifetime suicide attempts in transgender inmates. Mental health issues were reported and were seen to be interchangeable with suicide. |

| Edney, R. | To keep me safe from harm-transgender prisoners and the experience of imprisonment; Deakin. L. Rev; 2004; 9; 327. | Commentary | US | Discussion relating to M2F & F2M |

|

The commentary discusses sexual violence, disproroptionate punishment and the differing levels of medical treatment. A major source of contention, which is highlighted in the article, is the failure of correctional facilities to differentiate between sex and gender. |

| Emmer, P., Lowe, A. and Marshall, R. | This Is a Prison, Glitter Is Not Allowed: Experiences of Trans and Gender Variant People in Pennsylvania's Prison Systems; Hearts on a Wire Collective; 2011 | Report | US (Pennsylvania) | Discussion relating to M2F & F2M |

|

The report discusses the varied levels of housing and methods of classification; difficulty of bathrooms and showers with reports of rape and humiliation from officers; unfair solitary confinement; different levels of hormone use; general healthcare access with specific reference to HIV/STIs care and management; institutionalized discrimination and violence and risky sexual behavior. The report provides recommendations that include expanding options for housing placement; tailoring healthcare to address health needs; education and training programs; gender-based policy change as well as increased accountability and advocacy. |

| Erni, J. N. | Legitimating Transphobia: The legal disavowal of transgender rights in prison; Cult Stud; 2013; 27 (1); pp. 136-158 | Commentary | US; Hong Kong | Discussion relating to M2F & F2M |

|

Authors describe rape of transgender inmates as sexual terrorism. Prison officials see two genders placing transsexuals at high risk as housing based on the appearance of external genitalia. |

| Garcia, N. | Starting with the Man in the Mirror: Transsexual Prisoners and Transitional Surgeries Following Kosilek v. Spencer; Am J Law Med; 2014; 40 (4); pp. 442-462 | Journal article | US | Discussion relating to M2F & F2M |

|

The article reports on the deterioration of inmate mental health and inmates being at risk of assault and rape, stating that it can be caused from the housing of inmates based on genitalia. Authors note the refusal of gender transitional care, is deemed a violation of an individual’s Eighth Amendment right as it is viewed as a form of 'cruel and unusual punishment'. |

| Glezer, A. , McNiel, D. E. and Binder, R. L. | Transgendered and incarcerated: a review of the literature, current policies and laws, and ethics; J Am Acad Psychiatry Law; 2013; 41; pp. 551-558 | Commentary | US | Discussion relating to M2F & F2M |

|

Authors report on the violence against transgender inmates, noting that it is significantly higher than that of the general population. One study reported that 59% of GD inmates in a Californian prison were sexually assaulted. According to WPATH SOC, to proceed with surgery the individual must have had continuous 12 months’ worth of hormones and real-life experience. The classification of housing inmates was also reported on. |

| Green, R. | Transsexual legal rights in the US and UK: employment, medical treatment, and civil status; Arch Sex Behav; 2010; 39 (1); pp. 153-159 | Commentary | US; UK | Discussion relating to M2F & F2M |

|

Authors report on the US prison’s denial of transition related treatment. Under the federal Bureau of Prisons, if the inmate can provide documents of hormone use prior to incarceration, there is a greater chance of continued therapy. However, in most cases this is not practiced and abruptly stopping treatment can be extremely dangerous. In contrast, in the UK, inmates have received surgeries while imprisoned. This is more likely to happen if inmates have gender affirmed or are on hormones. The extent to which inmates are allowed to cross dress differs by prison given concern for prisoner safety and housing is allocated by birth gender unless undergone surgery. |

| Halbach, S. | Framing a narrative of discrimination under the eighth amendment in the context of transgender prisoner healthcare; J Crim Law Criminol; 2016; 105 (2); pp. 463-497 | Commentary | US | Discussion relating to M2F & F2M |

|

The article discussed the commonality of additional mental health problems if the inmate is denied hormones or surgery. The authors stated that a physician must diagnose an inmate with GD using the DSM and then must deem hormones or surgery to be a necessity. It states that by denying an inmate access to an evaluation and subsequent treatment, prisons are violating the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments. |

| Harawa, N. T., Amani, B., Rohde Bowers, J., Sayles, J. N. and Cunningham, W. | Understanding interactions of formerly incarcerated HIV-positive men and transgender women with substance use treatment, medical, and criminal justice systems; Int J Drug Policy; 2017; 48; pp. 63-70 | Journal article | US (California) | N = 19 M2F formerly incarcerated HIV positive participants interviewed with data analyzed using Thematic Analysis |

|

Findings include intense HIV stigma experienced by inmates, resulting in many not disclosing HIV status. Many were marginalized and denied benefits that they would normally be entitled to. Some hid their HIV status to other prisoners as well as healthcare professionals and so would forgo their treatment altogether for the duration of their sentence. Alcohol, drug use and mental were treated in prison but symptoms would cease on release. Some inmates had self-medication regimes, but the majority were processed through electronic databases and used pill-call allowing for almost complete adherence. Some misused prescribed medication while incarcerated. |

| Harawa, N. T., Sweat, J., George, S. and Sylla, M. | Sex and condom use in a large jail unit for men who have sex with men (MSM) and male-to-female transgenders; J Healthcare Poor Underserved; 2010; 21 (3); pp. 1071-1086 | Journal article | US (California) | Mixed methods with N = 109 M2F & F2M |

|

Sex is commonplace in prisons. 32% of inmates were HIV positive and 24% had received a positive STI diagnosis during their last incarceration period. Most people would not disclose if they are HIV positive as they want to continue having sex while incarcerated. 25% had sex with women during incarceration; two-thirds had oral sex and 53% anal sex. 13% had exchange sex, this was evident more in transgender inmates than men (28% vs. 10%) and 75% reported at least one act of unprotected anal sex. Condoms were distributed once per week. Custody staff were aware of sexual activity but chose not to do anything about it. In relation to housing, if homosexual or transgendered M2F pre-sex reassignment surgery, inmates are dubbed ‘K6G’ and segregated from general population. |

| Hochdorn, V., Faleiros, P., Valerio, P. and Vitelli, R. | Narratives of Transgender People Detained in Prison: The Role Played by the Utterances “Not” (as a Feeling of Hetero- and Auto-rejection) and “Exist” (as a Feeling of Hetero- and Auto-acceptance) for the Construction of a Discursive Self. A Suggestion of Goals and Strategies for Psychological Counseling Alexander; Frontiers in Psychology; 2018; Volume 8; Article 2367 | Journal article | Italy; Brazil | N = 23 in-depth interviews with transgender women detained in either female or male prison contexts in Italy and Brazil. |

|

The article contrasts the current treatment of transgender inmates in Brazil and Italy. In Brazil, there were reports of self-harm, sexual violence and assault as well as maltreatment by officers. Transgender inmates are not considered separate or different from the general inmate population and so they must dress and cut their hair the same as cis-gender men and are not allowed hormone treatment. In contrast, Italy allows individual or private cells with a maximum of 3 people, each with a toilet. No uniforms are required to be worn and inmates are allowed real life experience and gender affirmation. Hormonal treatments are allowed, these are partially supported by local health policies. |

| Jenness, V., Sexton, L. and Sumner, J. | Transgender inmates in California’s prisons: an empirical study of a vulnerable population. The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation Wardens’ Meeting; 2009 | Conference slides | US (California) | Discussion relating to M2F & F2M |

|

The Powerpoint slides were presented at the Californian Department of Corrections and Rehabilitations Warden's meeting in 2009. They reference the Detention Elimination Act regarding sexual abuse among transgender inmates. They report that sexual assault rates are significantly higher in transgender populations. It highlights that more research is needed on perceptions and opinions of staff and other inmates. Furthermore, they make reference to high profile cases such as Farmer v. Brennan and legislative mandates e.g. PREA, SADEA and AB382 of the penal code. Housing and expressed preference for classification were also considered. |

| Jones, L. and Brookes, M. | Transgender offenders: A literature review; Prison Service Journal; 2013; 206; 11-18. | Journal article | US; UK | Literature review relating to M2F & F2M |

|

The book chapter literature review identifies the significance of the 2004 Gender Recognition Act as allowing transsexual people to have legal recognition of their new gender. It also highlights that the majority of literature on transgender offenders is conducted in the US, which are more advanced than the UK guidance documents. It identifies that transgender inmates are extremely vulnerable from sexual violence as they have a unique set of health issues that can be a problem for the system. The article points out that the legal system has not informed prisons on how they should treat transgendered inmates. In the UK, there is no official monitoring within the prison system for gender identity, with only one study published at the time of the review. The comorbidity rates for psychological problems in transgender inmates are greater than in other groups. There was further discussion on treatment by officers, medical treatment and gender affirmation. The review concludes that more research is needed in the UK due to difficulty in engaging in effective therapeutic interventions. |

| Kendig, N. E., Cubitt, A., Moss, A. and Sevelius, J. | Developing Correctional Policy, Practice, and Clinical Care Considerations for Incarcerated Transgender Patients Through Collaborative Stakeholder Engagement; J Correct Healthcare; 2019; pp. 1-9 | Journal article | US | Stakeholder Focus Groups analyzed using discourse analysis considering M2F & F2M |

|

Findings from focus groups include recommendations of a tailored approach to healthcare through counseling. This approach should be carried through transition related care with hormone therapy to be recommended, continued and medically adjusted if required. If no prior hormone therapy or documentation is available, inmates should be assessed, and treatment initiated. Medical officers should recognize and understand the range of medical services that are important and necessary in order to provide good standards of care to transgender inmates. Knowledge and training of correctional staff should be implemented. The article also discusses the role of specific units to address the housing and classification complex and also acknowledges that it could be down to the choice of the inmate by tailoring the decision making of housing transgender individuals through interdisciplinary assessment. |

| Lamble, S. | Rethinking Gendered Prison Policies: Impacts on Transgender Prisoners; The Howard League for Penal Reform: Early Career Academics Network Bulletin; 2012; 16; 7-12. | Commentary | UK | Discussion relating to M2F & F2M |

|

UK-based commentary that discussed gender segregation in prisons. Until recently, regardless if an individual has a Gender Recognition Certificate, they are housed based on their birth gender. This changed when a M2F won a case v Ministry of Justice after they ignored the certificate. This was in breach of Article 8 of the European Convention of Human Rights. The Equality Act of 2010 also offers transgender inmates greater protection. Other issues discussed in the commentary include unsolicited solitary confinement, denial to trans-specific healthcare such as make-up, hormones and surgery, with many stopping the transition once they enter prison. Harassment, assault and abuse was also discussed. Furthermore, it identified that the PSI 2011 issues. The Care and Management of Transsexual Prisoners guidelines in compliance with the Equality Act 2010 |

| Lea, C. H., GDeonse, T. K. and Harawa, N. T. | An examination of consensual sex in a men's jail; Int J Prison Health; 2018; 14 (1); pp. 56-61 | Journal article | US (California) | N = 17 M2F Participants Interviewed and data Thematically Analyzed |

|

This paper examined sexual behaviors of consensual sex and the enhanced provision of condom distribution in a specialist protective custody unit. Transgender women felt they were not attractive to men in some units who were homosexuals and attracted to men, so felt slightly safer in the segregated unit where they can live as a woman. However, they still witnessed and engaged in high levels of sexual activity regularly. They reported how condom use was poor as most prisoners in the unit already had HIV and it was prison policy for only one condom to be issued each week – this was even when men were having sex several times a night. In the new condom distribution program, more condoms were issued and some prisoners took lots of condoms and gave these out to others who were not on the program. |

| Levine, S. B. | Reflections on the Legal Battles Over Prisoners with Gender Dysphoria; J Am Acad Psychiatry Law; 2016; 44 (2); pp. 236-244 | Commentary | US | Discussion relating to M2F & F2M |

|

Personal commentary exploring existing paradigms of GD and how they are used in legal battles. Further exploration by author into general experiences of transgender prisoners and the treatment of GD using hormones and SRS. |

| Mann, R. | The treatment of transgender prisoners, not just an American problem: A comparative analysis of American, Australian, and Canadian prison policies concerning the treatment of transgender prisoners and a ‘‘universal’’ recommendation to improve treatment; 2006; 15; pp. 91-133 | Commentary | US; Australia (New South Wales); Canada | Discussion relating to M2F & F2M |

|

This paper notes the high levels of violence and abuse experienced in prison, as well as the severe side effects of coming off hormone treatment. The paper focused mainly on the issues of hormone treatment and surgery, authors highlight the disparity of treatment across countries but, in the main, if a prisoner has not started treatment prior to incarceration, it is unlikely they will be issued it in prison. Authors discuss housing of prisoners and how this is a difficult process when considering the risk to the transgender prisoner and the potential risk to other prisoners (usually females). Prisons allocate prisoners by sex at birth although some prisons are moving transgender prisoners to pods or specialist units. Authors note the trend to of prisons to use segregation units, but note the significant consequences for MH, ability to socialize etc. |

| Maruri, S. | Hormone therapy for inmates: a metonym for transgender rights; Cornell J Law Public Policy; 2011; 20 (3); pp. 807-831 | Commentary | US | Discussion relating to M2F & F2M |

|

This paper highlights the problem with a diagnosis from the DSM-IV for GD means that prisoners are often viewed as sick or abnormal in some way |

| McCauley, E., Eckstrand, K., Desta, B., Bouvier, B., Brockmann, B. and Brinkley-Rubinstein, L. | Exploring Healthcare Experiences for Incarcerated Individuals Who Identify as Transgender in a Southern Jail; Transgender Health; 2018; 3 (1); pp. 34-40 | Journal article | US (Florida) | Use of screening questionnaire and Interview N = 10 M2F inmates of color, data analyzed using Thematic Analysis |

|

Participants report a significant lack of access to healthcare resulting in an increase in mental health symptoms during imprisonment. Imprisonment in and of itself was reported to trigger MH episodes and symptoms. Sexual and violent assaults are regularly experienced along with routine harassment. The mental health implications mean transgender prisoners feel dehumanized have low levels of self-worth, self-esteem and self-stigma. Participants experienced disruption in their treatment (hormone therapy) which had consequences in terms of negative side effects. In terms of housing, participants reported the use of segregation in solitary confinement for long periods to deal with the prisons housing issue. Participants were sometimes moved to specialized wings with people who have significant vulnerabilities or problems, but they did not feel protected in these wings, at times felt more at risk, as participants describe rapists targeting them in the showers. Solitary confinement is used to punish people and so being sent there was very hard, many reported wanting to commit suicide. Participants noted issues with being placed in a female jail too in that they were just as at risk of abuse and violence there and wanted to be placed in a transgender unit. |

| Okamura, A. | Equality behind bars: improving the legal protections of transgender inmates in the California prison systems; Hastings Race Poverty LJ; 2011; 8; 109 | Commentary | US (California) | Discussion relating to M2F & F2M |

|

The commentary outlined the legal protections for transgender inmates in California, US. It discussed sexual assault and prison rape; lack of adequate healthcare (citing Estelle v Gamble), which itself is underfunded for the general population; identified that between 60-80% of transgender inmates are HIV + ve; classification, housing and segregation; PREA; Detention Elimination Act, SADEA and the concept of deliberate indifference and duty to protect through the Eighth Amendment. |

| Osborne, C. S. and Lawrence, A. A. | Male Prison Inmates With Gender Dysphoria: When Is Sex Reassignment Surgery Appropriate?; Arch Sex Behav; 2016; 45 (7); pp. 1649-1662 | Commentary | US | Discussion relating to M2F & F2M |

|

Authors discuss eligibility criteria for SRS. They note inmates are disadvantaged as the a) are unable to document persistent and well documented GD b) do not have access to full information or comprehend the challenges, consent is an issue c) can not always get a diagnosis of MH and keep it under control in prison; d) cannot always live in preferred gender for minimum of 12 months while possible in prison. Post SRS, authors note transgender women should be housed in a women's prison automatically after surgery, but there are issues e.g. some men opting out of SRS even when they medically need it, or when transgendered women have engaged in violence against women |

| Peek, C. | Breaking Out of the Prison Hierarchy: Transgender Prisoners, Rape and the Eighth Amendment’; Santa Clara Law Review; 2004; 1211-1248 | Commentary | US | Discussion relating to M2F & F2M |

|

The legal commentary covering the following topics: evaluation and diagnosis; lack of understanding of GD and what it means to be transgender; housing and placement; surgery; rape, sexual abuse and coercive sex; the 'modern' Eighth Amendment in the context of Farmer v Brennan and deliberate indifference. |

| Poole, L., Whittle, S. and Stephens, P. | Working with transgendered and transsexual people as offenders in the Probation Service; Probation Journal; 2002; 49 (3); 227-232 | Journal article | UK | Discussion relating to M2F & F2M |

|

Research study that interviewed officers as part of their sample. The article that discusses officers understanding and existing bias toward transgender inmates. Officers stated that transgender inmates were much like general population and so their offending behavior needed to be challenged regardless of their gender, therefore no discrimination either way. It discussed the need for hormones in order to control sexual needs and that officers needs better education and training. |

| Poteat, T. C., Malik, M. and Beyrer, C. | Epidemiology of HIV, Sexually Transmitted Infections, Viral Hepatitis, and Tuberculosis Among Incarcerated Transgender People: A Case of Limited Data; Epidemiol Rev; 2018; 40 (1); pp. 27-38 | Journal article | Global | Systematic literature review studies including M2F & F2M |

|

This systematic review found very few studies detailing the HIV, STI, viral hepatitis and TB status among transgender inmates. They found 1 HIV prevalence study and one TB study that support the view that prevalence of HIV and related infections are high amongst this population. Likewise, they found limited prevention programs as a result of facilities fearing the promotion of sexual activity in prison. |

| Reisner, S. L., Bailey, Z. and Sevelius, J. | Racial/ethnic disparities in history of incarceration, experiences of victimization, and associated health indicators among transgender women in the U.S; Women Health; 2014; 54 (8); pp. 750-766 | Journal article | US | Survey Research of N= 6456 M2F transgender participants analyzed using Inferential statistics |

|

Study found 19.3% of transgender women had previously been incarcerate and were more likely, when compared to others in the survey to be women of color, have a low income, education, be uninsured. Black transgender women were three times more likely to have been imprisoned. Transgender participants had disproportionate health disadvantages when compared to others including smoking, use of substances, HIV positive status, sex work, experiencing physical and sexual assault. When in prison, this population reported greater victimization and mistreatment and denial of healthcare was reported by 24.5%. These women were more likely to report daily cigarette smoking, substance use, suicide attempts compared to those not in jail. |

| Routh, D., Abess, G., Makin, D., Stohr, M. K., Hemmens, C. and Yoo, J. | Transgender Inmates in Prisons: A Review of Applicable Statutes and Policies; Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol; 2017; 61 (6); pp. 645-665 | Journal article | US | Systematic review of US statutes considering M2F & F2M |

|

Authors found 37 states allow for counseling services for transgender prisoners; over half of states do not allow to obtain treatment after incarceration; 13 states allow for initiation, or beginning of hormone treatment, 21 states allow continuation of hormone therapy and 20 states do not allow. Only 7 states allow for SRS. They also found that some states use DSM-5 for gender identity disorder or gender dysphoria and this then dictates treatment pathways, but this is not consistent across all 50 states reviewed. |

| Schneider, D. | Decency, Evolved: The Eighth Amendment Right to Transition in Prison; Wis L Rev; 2016; 4; pp. 835-870 | Commentary | US | Discussion relating to M2F & F2M |

|

Author discusses the physical and psychological consequences of stopping hormone treatment on arrival to prison, which is often experienced by inmates. The commentary highlights how not all states in the US have formal policies requiring the provision of medical treatment to transgender inmates and that the Standards of Care do not appear to be routinely applied. Although, some prisons have worked flexibly, not all have and as a result law suits have followed. The author also notes the risk of harm to male to female prisoners who remain housed in male prisons. Authors advise a case by case approach has been adopted in many states |

| Sevelius, J. and Jenness, V. | Challenges and opportunities for gender-affirming healthcare for transgender women in prison; Int J Prison Health; 2017; 13 (1); pp. 32-39 | Commentary | US (California) | Discussion relating to M2F & F2M |

|

Authors note how left untreated the mental health outcomes for people with GD can be significant resulting in suicide and depression. Transgender women are most likely to be living with HIV experience serious MH conditions and as such should be regularly assessed for these conditions and offered support. Authors also discuss housing in prison and highlight the range of policies in prisons and detention centers that now consider the gender identity of the prisoner rather than their gender at birth. Consideration is given to place transgender women in female units as the policy recognizes the greater risk of victimization this group face and thus, aim to reduce this. The authors also note it remains unclear if this type of housing addresses the victimization of transgender women. |

| Sexton, L., Jenness, V. and Sumner, J. M. | Where the Margins Meet: A Demographic Assessment of Transgender Inmates in Men's Prisons; Justice; 2010; 27 (6); pp. 835-865 | Journal article | US (California) | Mixed methods using N = 316 M2F & F2M transgender inmates |

|

This study found transgendered prisoners a highly victimized population with 61.1% experiencing physical assaults outside of prison and 85.1% physically assaulted in lifetime. 60-80% have HIV. 40.2% had to engage in sexual acts against their will outside of prison, 52.7% had done sexual acts they would rather not have done outside prison, and 70.7% had engaged in sexual acts against will in lifetime. 21.0% were homeless right before their most recent incarceration, 47.4% had ever experienced homelessness. 66.9% report mental health problems since being incarcerated and 42% participated in sex work. The sexual and gender identity of transgender prisoners are complex in prison. Often a conflation of identity and sexuality occurs, in that transgender prisoners are viewed homosexual. |

| Simopoulos, E. F. and Khin, E. K. | Fundamental principles inherent in the comprehensive care of transgender inmates; J Am Acad Psychiatry Law; 2014; 42 (1); pp. 26-35 | Commentary | US | Discussion relating to M2F & F2M |

|

This discussion paper reports how transsexualism or Gender Identity Disorder (GD)/Gender Dysphoria has been criticized for its use as a labeling tool that serves to add to already stigmatized group. Authors note the criteria for diagnosis in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), is under much debate. They note issues with diagnosis, many people are not being diagnosed, or wrongly diagnosed – resulting in no medical treatment. Authors note transgendered prisoners have greater healthcare needs are at increased risk of MH, suicide, HIV infection. The authors discuss the binary nature of prison classification that does not accommodate transgender inmates, often placed in segregation or vulnerable wings. This housing strategy does not mean conditions are any safer or in cases of F2M where inmates are placed in male prisons, are arguably greater risk. Management of inmates in terms of record keeping is inconsistent. |

| Stotzer, R. L. | Law enforcement and criminal justice personnel interactions with transgender people in the US: A literature review; Aggress Violent Behav; 2014; 19 (3); 263-276 | Journal article | Global | Literature review discussing M2F & F2M |

|

This literature review found transgendered prisoners are denied basic care and access to hormone treatment. When living out in the community, transgender people report being treated as criminal suspects by correctional staff in the community, experience high arrest rates, and face harassment and assaults from police. When in prison they face abuse and harassment by staff including physical and sexual assaults. They feel they are treated unfairly by staff compared to other inmates and when correctional staff respond to complaints of abuse these are undermined. Sentencing of transgender prisoners appear to receive longer sentences and less conditional release options. |

| Sultan, B. A. | Transsexual prisoners: how much treatment is enough?; New Engl Law Rev; 2003; 37 (4); pp. 1195-1229 | Commentary | US | Discussion relating to M2F & F2M |

|

This paper details legislation and strategies relevant to transgender prisoners in the Commonwealth of Australia. Authors note how transgender prison policies typically focus on four domains: identification, classification and placement, health services/treatments, and ‘every day’ living issues. Authors note the rights of transsexuals v. the rights of other prisoners as well as the need to administer justice and punishment. The author notes transsexual inmates do not “deserve” more treatment or concern than non-transsexual inmates. The author highlights the costs of surgery and treatment. Individuals need to pay privately, although low-income transgender people can usually not afford this – the author highlights, if treatment/gender reassignment surgery was made available in prisons, transgender people would commit crime just to get into prison. The author further notes that society would be dissatisfied if transgendered inmates received better treatment than non-transgendered inmates. That it is not the role of prison staff to make inmates happy. |

| Sumner, J. and Jenness, V. | Gender Integration in Sex-Segregated U.S. Prisons: The Paradox of Transgender Correctional Policy; 2014; New York: Springer | Book Chapter | US | Systematic review of documents and records; Thematically Analyzed examining M2F & F2M |

|

This book chapter outlined findings from a systematic review that analyzed a range of US correctional policies, court opinions, etc. Authors present issues with medical treatment in terms of diagnosis, surgery, and gender affirming treatment, as well as the rationale for using segregation to house transgender inmates. They first note the problem with the varying definitions making diagnosis a challenge. Authors highlight how use of inmates preferred name has become part of correctional policy under the recognition that prisoners have the right to be treated with respect, impartially and fairly by all employees. Likewise, wearing gender appropriate clothing is also now recognized in policy with the aim to ensure dignity and respect. However, in some operation/healthcare manuals, gendered specific clothing are not tolerated and often seen as contraband e.g. women's bras, cosmetics. In practice policy is not yet fully implemented. Historically, people with Gender Dysphoria had been loosely classified as "effeminate homosexuals" and classification very rarely occurs on the basis of sexual preference. While there have been legal challenges to housing decisions, inmates continue to be segregated even though this is usually for the purpose of punishment. While, male to female prisoners are less victimized when placed in female prison, authors note how female inmates may be at greater risk of violence, or at the least have their privacy violated. In some US prisons screening for transgender status is taking place, and prisoners are housed in wards or pods for gay inmates, where gendered housing is provided, developments have been noted |

| Tarzwell, S. | Gender lines are marked with razor wire: addressing state prison policies and practices for the management of transgender prisoners; Columbia Hum Rights Law Rev; 2006; 38; 167-219 | Commentary | US | Discussion relating to M2F & F2M |

|

The legal commentary focuses on 'hyper-gendered systems' and 'sex-segregated facilities where traditional gender roles are strictly enforced' (p. 177). The article also discusses safety concerns; victimization and stigma; solitary confinement; mental health; denial of gender affirming medical care and hormone therapy. It places the challenges in the context of Eighth Amendment Jurisprudence, 'deliberate indifference to serious medical need' (p. 181), citing key legal cases throughout. The article concludes, 'Transgender advocates must pressure prisons to voluntarily adopt policies embodying concrete reforms that will improve the daily lives of transgender prisoners.' (p. 219) |

| von Dresner, K. S., Underwood, L. A., Suarez, E. and Franklin, T. | Providing counseling for transgendered inmates: a survey of correctional services; Int. J. Behav. Consult. Ther; 2013; 7; 38-44 | Commentary | US | Discussion relating to M2F & F2M |

|

Commentary describing the high rates of sexual assault, risk taking behavior and STI/HIV transmission among transgender inmates. Transgender inmates are also at considerable risk of relapsing or increasing psychological symptoms. It discusses the main treatment for TG inmates, 'freeze-framing' in that they should maintain status quo of their appearance and current treatment when they enter into a correctional facility. However, this does not account for those that have not been previously diagnosed with GD. Mental health assessment and services should therefore be working with transgender and potential transgender inmates to abide by SOCs. Other areas addressed include housing and provisions, such as gender affirmation and tailored services |

| Wall, B. W. | Commentary: gender nonconformity within a conformist correctional culture; J Am Acad Psychiatry Law; 2014; 42 (1); pp. 37-38 | Commentary | US | Discussion relating to M2F & F2M |

|

The author highlights the nature and risk of violence/abuse, mental health, and medication/treatment for transgender inmates. How the binary nature of prison system presents issues of bias and prejudice. Authors refer to the principles as outlined by Simopoulos and Khin could serve to improve healthcare in prisons. Authors note that a need for openness and sensitivity to gender concerns is called for as well as approaching transgender prisoners as individuals with individual needs. |

| White Hughto, J. M. and Clark, K. A. | Designing a Transgender Health Training for Correctional Healthcare Providers: A Feasibility Study; Prison J; 2019; 99 (3); 329-342 | Journal article | US | Seven stage evaluation of previous intervention |

|

The article describes the authors’ research study that piloted a transgender health training for correctional healthcare provider. Key topics include the integrating gender affirming language such as preferred pronouns; exposure to stories from transgender inmates; hormone provision; surgical considerations and mental health therapies. 'Providers indicated that the training provided them with the required cultural competencies to provide care to transgender patients and basic competencies for affirming clinical interactions' (p. 6) |

| White Hughto, J. M., Clark, K. A., Altice, F. L., Reisner, S. L., Kershaw, T. S. and Pachankis, J. E. | Creating, reinforcing, and resisting the gender binary: a qualitative study of transgender women's healthcare experiences in sex-segregated jails and prisons; Int J Prison Health; 2018; 14 (2); pp. 69-87 | Journal article | US | N = 20 M2F former inmates interviewed, data analyzed using Thematic Analysis |

|

Participants fear violence and abuse in male prisons, some participants complied with male norms and did not disclose transgender status. Participants report inadequate healthcare e.g. not being able to access hormone treatment, as a result of them using street hormones and not officially prescribed drugs prior to incarceration; the state would not recognize their need for continued treatment without official prescriptions. Some health providers use the argument that if prisoners used hormone treatment they would be at increased risk of violence. Poor knowledge amongst treatment providers along with transphobic attitudes was reported, this meant some prisoners would simply conform to male norms or exert their gender and behave more feminine. |

| White Hughto, J. M., Clark, K. A., Altice, F. L., Sari, L. R., Kershaw, T. S. and Pachankis, J. E. | Improving correctional healthcare providers’ ability to care for transgender patients: Development and evaluation of a theory driven cultural and clinical competence intervention; Soc Sci Med; 2017; 195; pp. 159-168 | Journal article | US (Massachu-setts; Connecticut) | Mixed methods exploration of N = 34 health practitioners discussed M2F & F2M |

|

This study discussed methods to improve healthcare provisions rather than document prisoner’s experiences. Authors note that interventions are needed to not only improve the knowledge, attitudes and skills of healthcare providers, but to encourage a willingness to provide gender-affirming care also. However, authors report how healthcare providers do not feel equip or skilled to give gender affirming care. |

| Wilson, M., Simpson, P. L., Butler, T. G., Richters, J., Yap, L. and Donovan, B. | ‘You’re a woman, a convenience, a cat, a poof, a thing, an idiot’: Transgender women negotiating sexual experiences in men’s prisons in Australia; Sexualities; 2017; 20 (3); pp. 380-401 | Journal article | Australia (New South Wales) | N = 7 M2F Inmates interviewed |

|

Participants reported experiencing sexual abuse in prison, including rape, assaults, witnessing rape and assaults and sexual harassment. Personal strategies to cope in prison were discussed including (stand up and fight getting support from other prisoners, affiliating with ethnic groups for support, being in female prison). While hormone treatment was not discussed by participants, reference was made to prisons appearing to know nothing of hormone treatments. New South Wales policy takes a case management approach, they consider the offense, risk to others in the prison and risk to the transgender prisoner before determining which gender prison to allocate them too. |

| Yap, L., Richters, J., Butler, T., Schneider, K., Grant, L. and Donovan, B. | The Decline in Sexual Assaults in Men’s Prisons in New South Wales: A “Systems” Approach; Journal of Interpersonal Violence; 2011; 26, 15; 3157-3181 | Journal article | Australia (New South Wales) | Interviews with N = 33 men and N = 7 M2F in a New South Wales prison |

|

The study from New South Wales, Australia, reported that prison rapes and sexual violence was occurring less frequently than previous decades. One participant believed that this is due to generational differences, who are now less violent and more open-minded. It is also effected by reduced drug supply, demand and harm reduction progams. However sexual violence is still present, and can turn violent if not reciprocated. The study calls for new programs to be implemented that support the changing environments of correctional facilities |

Table 3.

Additional grey literature results.

| Author | Title, year and other details | Location | Type of publication | Definition of transgender synonym | Findings/key points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| American Psychological Association | Guidelines for psychological practice with transgender and gender non-conforming people. Am. Psychol; 2015; 70; 832-864 | US | Guidelines | Transgender and gender nonconforming (TGNC) people are those who have a gender identity that is not fully aligned with their sex assigned at birth. | Guidelines that focus on the psychological aspect of transgender incarceration, including addressing issues such as harassment, abuse and victimization. Also discussing the role of mental health professionals. |

| Arnott, J. and Crago, A. | Rights Not Rescue: A Report on Female, Male, and Trans Sex Workers’ Human Rights in Botswana, Namibia and South Africa; 2009; New York: Open Society Institute | South Africa | Report | Not mentioned | The report namely discusses South Africa (SA) where, 'trans sex workers are systemically submitted to violence by being locked in jail with men' (p 40). Also, no condoms are distributed in prisons in SA. Police will also encourage other prisoners to harm trans inmates. 'Hormone replacement for trans women and other trans-specific medical treatment is not available in South African prisons because it is not considered primary healthcare.' (p 50). |

| Blight (2000) | Transgender Inmates. Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice; Australian Institute of Criminology | Australia | Report | According to The New South Wales Anti-Discrimination Act a transgender person as someone who: • identifies as a member of the opposite sex by living, or seeking to live, as a member of the opposite sex • has identified as a member of the opposite sex by living as a member of that sex • being of indeterminate sex, identifies as a member of a particular sex by living as a member of that sex, and includes a person being thought of as a transgender person, whether the person is, or was, in fact a transgender person. | The report covers different Australian province prison policy, discrimination protection and birth/sex recognition. It discusses housing based on self-choice; self-harm, sexual assault and surgery. |

| Blazer and Hutta (2012) | Transrespect versus Transphobia Worldwide: A Comparative Review of the Human-rights Situation of Gender-variant/Trans People; 2012; Transrespect | Global | Report | Not mentioned | Report on the international transgender situation. E.g. 1. Uganda - inmates gender identity denied and suffered assaults from other inmates and prison wards (p 35); E.g. 2. Thailand and Philippines - ' In Thailand and the Philippines, penal laws also do not recognize transpeople’s gender identity…Many transpeople in the Philippines try to circumvent the law’s limitations by securing identification documents that reflect their identity through sometimes illegal but mostly creative means (i.e., black-market passports, credit-card or bill statements declared in their preferred names, fake IDs, etc.)' (p 82). |

| Bassichis and Spade (2007) | It's War in Here: a Report on the Treatment of Transgender and Intersex People in New York State Men's Prisons. Sylvia Rivera Law Project; 2007; New York | US | Report | Not mentioned | The report is affiliated to the Sylvia Rivera Law Project, which was opened in 2002. The Project has 'provided free legal services to over 700 intersex, transgender, and gender non-conforming people'. Includes: assault, sexual violence, stigma and discrimination, denial of treatment, housing, lack of medical care, HIV/STI and gender affirmation. Other topics covered in the report include showers, lack of privacy and searches. Recommendations put forward include to improve safety and treatment of transgender inmates, enhance grievance procedures and ensure access to healthcare. |