Abstract

Background: Trans male gender affirming surgery is becoming more available resulting in an increase in patients undergoing these procedures. There are few reports evaluating the outcomes of these procedures in the transgender population. This study was performed to provide patient-centric insight on self-image and other concerns that arise during surgical transition.

Methods: A 22-question survey was sent to 680 trans male patients. The survey was broken down into the following sections: demographics, timing and type of surgical procedures, self-image, sex/dating life, social life, employment, co-existing psychiatric morbidity, and common issues faced during the surgical transition.

Results: A total of 246 patients responded (36% response rate). Most patients (54%) waited 1–2 years after starting their transition before having a surgical procedure, and 10% waited longer than 6 years. In regard to self-image, sex/dating life, and social life there was a significant improvement (p < 0.001) after undergoing gender affirming surgery. Patients reported significantly less difficulty with employment after having gender affirming surgery (p < 0.001). If present, the following psychiatric morbidities were self-reported to have a statistically significant improvement after surgery: depression, anxiety, substance abuse, suicidal ideation, panic disorder, social phobia, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (P < 0.003).

Conclusion: It is important to provide patients, surgeons, and insurance companies with expected outcomes of gender affirming surgery along with the potential risks and benefits. Post-surgical trans male patients reported a significant improvement in overall quality of life. Initial hesitations to having surgery such as regret and potential complications were found to be non-issues. Additional research should be done to include more patients with phalloplasties, trans females, and nonbinary identifying patients.

Keywords: mental health, quality of life, satisfaction, surgery outcomes, trans men, transgender

Introduction

Trans male gender affirming surgery is becoming more popular with increased coverage by insurance companies and the availability of surgeons offering these procedures. The gender affirming procedures most commonly performed on trans male patients include: mastectomy, hysterectomy, oophorectomy, phalloplasty, scrotoplasty, and insertion of testicular and/or penile prosthesis (Ratnam & Ilancheran, 1987). At this time, there is a paucity of data evaluating the outcomes of these procedures in the transgender population. There have been a few studies in the last ten years reporting the benefits of mastectomy in the trans male population. These studies have specifically shown improvements in self-confidence, personal relationships, social interactions, work, hobbies, body image, and quality of life (Nelson et al., 2009; van de Grift et al., 2016).

We sought to propose a more comprehensive survey that included patients who have undergone some or all of the above listed procedures. During the time we were implementing this study, there was no validated survey that would address all of the points we present here (Cohen et al., 2019). The purpose of our study was to evaluate the timing and sequence of gender affirming surgery(ies), the impact on self-image, dating life, social life, employment, psychiatric morbidities, and the hurdles that transgender patients face throughout their surgical transition. Additionally, we would like to present the largest known trans male series collected by a single surgeon to date (some procedures were done by other surgeons). Analyzing these surgical outcomes is important regarding not only counseling patients on realistic expectations, but also in providing data to healthcare providers and insurance companies on the impact of gender affirming surgery on trans male patients.

Materials and methods

In July of 2016, a 22-question survey developed using SurveyMonkey (Palo Alto, CA) was sent to patients who identified as being trans male during their initial consultation with the senior author. If a patient in our database did not yet undergo a masculinizing procedure, they were excluded. Furthermore, the senior author did not perform all of the reported surgeries. Six hundred and eighty patients were contacted and responses were collected for a two-month period. During this time, two reminder emails were sent without any incentives to complete the survey. Our study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board (IRB).

The survey is contained in Appendix 1, and the questions were aimed to evaluate satisfaction in their surgical transition in addition to learning more about the timing and preferences each patient had. The first page of the survey was aimed at understanding the patient’s background with emphasis on self-image, psychiatric history, and hormonal therapy. The second page elicited the patient’s surgical and procedural history to determine what surgeries each patient had already completed with a focus on genital surgery. The third page inquired about the patient’s recovery phase to help elucidate more about how they perceived the process, improvements in self-image, mental health, and duration of follow-up.

Data from both surveys were performed using Stata/SE version 12.0 (StataCorp Inc., College Station, TX, USA). All statistical tests were two-sided and significance was set to the level of p < 0.05. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used as an alternative to the paired Student’s t-test because the sample size is small, and the population cannot be assumed to be normally distributed. Logistic regression was used to examine correlations for dichotomous variables.

Results

A total of 246 patients responded resulting in a response rate of 36%. Most patients (54%) waited 1-2 years after starting their transition before they had their first procedure with only 10% of patients waiting longer than 6 years. Seventy-four percent of patients had their first procedure within 2 years of being on hormonal therapy. The average age range at which patients had their first transgender operation was between 21-25 years old. There were three patients who did not have their first procedure until after the age of 50. Of the patients surveyed, the following procedures were reported in descending popularity: 94% had a mastectomy, 20.5% had a hysterectomy, 1.5% had a phalloplasty (zero metoidoplasties, one anterio-lateral thigh flap, and 2 radial forearm free flaps), 0.5% had a scrotoplasty, and 0.5% had a prosthesis inserted to achieve an erection. The average follow-up time after surgery was 1 year. For those who had a hysterectomy, this would usually precede mastectomy. For those who had a phalloplasty, this was always the last procedure to be completed. The following are the most to least common reasons why patients were not interested in phalloplasty at the time of the survey: “too many complications” (59%), “price” (53%), “I am happy now the way that I am” (38%), “I plan to have bottom surgery in the future” (24%), and “too far to travel” (15%). Some other notable hesitations include: “the current available procedures don’t give good results” and “possible loss of ability to orgasm.”

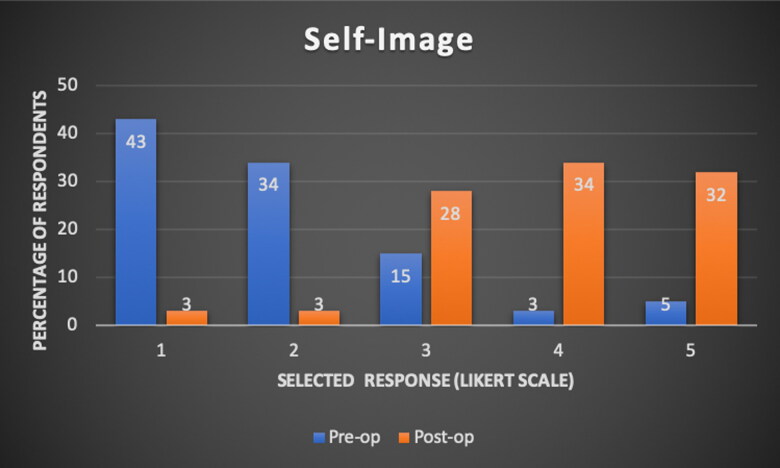

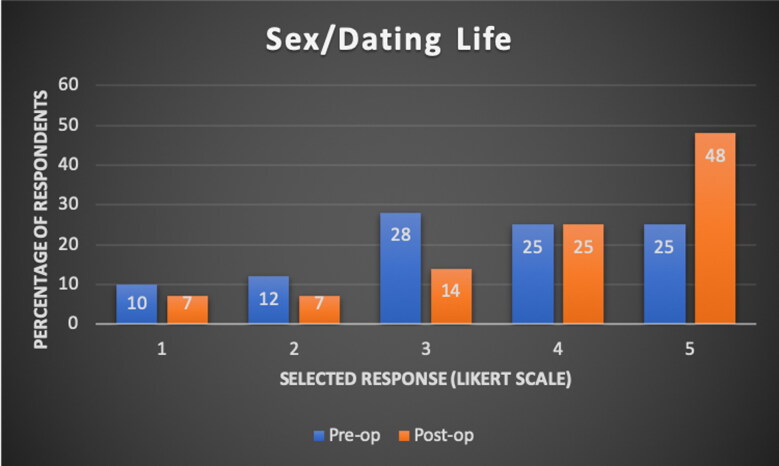

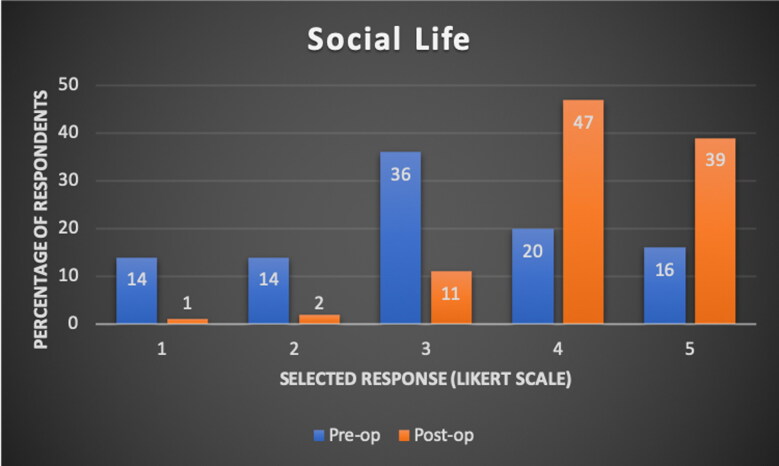

Each patient was asked to recollect how they felt about their self-image prior to undergoing any masculinizing procedures on a 5-point scale with 1= “uncomfortable, and I don’t even like to look at myself naked” and 5= “very comfortable, and I’m not afraid to show off my body.” This data is shown in Figure 1. The category with the highest response rate was 1. Each patient was then asked about their current self-image given the fact that they had undergone at least one masculinizing procedure. The category with the highest response rate was a 4. The improvement in self-image was statistically significant with a p-value of <0.001. A similar 5-point scale was given to evaluate sex/dating life with 1= “not sexually active, or unable to have a fulfilling dating experience” and 5= “very satisfied with my dating life or level of sexual activity.” This data is shown in Figure 2. In the memory of the patient (prior to having procedures), the category with the highest response rate was 3. At the time of the survey (after having at least one procedure), the sex/dating life improved with the highest response rate being 5. The improvement in sex/dating life is statistically significant with a p-value of <0.001. Social life was evaluated on a 5-point scale with 1= “I avoided being around other people” and 5= “I loved being around other people.” (See Figure 3) In the memory of the patient, their pre-operative social life was most commonly reported as 3. After surgery, social life improved with 47% responding 4 and 39% responding 5. The improvement in social life was statistically significant with a p-value of <0.001. Pre-operative employment was assessed, and 19% of patients recollected having trouble obtaining or keeping employment due to their gender identity. This improved after undergoing at least one masculinizing procedure as only 9% of transgender patients admitted to having trouble with employment at the time of the survey (p-value <0.001). Overall, 60% of patients felt as though their quality of life had very much improved with an additional 26% feeling as though their life was at least 80% better when looking back to how they felt prior to having undergone surgery.

Figure 1.

Self-Image (1-being the lowest desired outcome, and 5-being the highest).

Figure 2.

Sex/Dating Life (1-being the lowest desired outcome, and 5-being the highest).

Figure 3.

Social life response rates (1-being the lowest desired outcome, and 5-being the highest).

Patients were asked if they had a history of any psychiatric morbidities before undergoing any procedure. The following list is the most to least common reported psychiatric morbidity: depression (73%), anxiety (70%), suicide attempt (27%), social phobia (23%), panic disorder (18%), obsessive-compulsive disorder (16%), and substance abuse (15%). Although nobody admitted to genital mutilation, two patients mentioned a history of self-harm, two patients suggested that they had an “eating disorder,” and only 18% of patients denied having any prior psychiatric history. At the time of the survey, patients admitted to having at least some improvement in the following psychiatric morbidities: depression (52%), anxiety (48%), suicidal ideation (14%), social phobia (14%), panic disorder (7%), obsessive-compulsive disorder (5%), and substance abuse (9%). The subjective improvement in psychiatric morbidities was statistically significant in all of the above with p-value <0.003.

The concerns and hesitations that each patient remembered having prior to their surgery are listed from most to least common: complications from the surgery (70%), inability to afford the procedure (61%), social expectations or non-acceptance of my decision (35%), not being able to pass as my gender (35%), mistreatment by a member of the medical team (26%), potential regret after having surgery (13%), and dissatisfaction with results (7%). Thirteen percent of patients did not have any significant concerns that they could recall. At the time of the survey, when patients had already undergone a procedure, the following percentage of patients actually experienced these issues peri-operatively: complications from the surgery (18%), inability to afford the procedure (5%), social expectations or non-acceptance of my decision (10%), not being able to pass as my gender (14%), mistreatment by a member of the medical team (5%), regret after having surgery (1%), and dissatisfaction with results (2%).

This survey was given at a single point during each patient’s transition. It is a retrospective study; therefore, all of the pre-op responses are based on the recollection of each patient and is subjected to recall bias. There are many patients who reported on desiring additional procedures. More specifically, 41% plan on undergoing phalloplasty (20% metoidioplasty, 13% anterior-lateral thigh flap, and only 8% desiring radial forearm free flap), 39% plan on having a hysterectomy, 19% plan on having a scrotoplasty, 12% plan on having a prosthesis to achieve erection, and 6% plan on having facial masculinization.

Discussion

The baseline incidence of gender affirming surgery has not yet been fully determined. Surgical volume clearly seems to be increasing in reports and varies widely amongst countries. This is likely based on different reporting agencies, temporal changes in financial coverage by country and transparency of the individuals. According to a study done by Berry et al. in 2012, the prevalence ranges from between 10 and 44:100,000 (Berry et al., 2012). For the properly selected transgender patient, some of the known beneficial therapeutic approaches are hormonal and surgical gender affirmation in conjunction with mental health providers (Hage & Karim, 2000). Of those who seek gender affirming surgery, mastectomy in trans male individuals is frequently the initial surgical procedure (Berry et al., 2012). Most of our patients underwent their first surgical procedure within 2 years of transitioning and starting hormonal therapy.

Many trans male patients never undergo genital surgery other than hysterectomy and salpingo-oophorectomy (Hage & De Graaf, 1993). In our patient population only 1.5% had undergone phalloplasty. There were many reasons for this low percentage with the most common (59%) being “too many complications” followed by “price” (53%). The patients who wish to undergo phalloplasty (41%) plan on doing so when they have financial means and/or “better procedures” are developed with less complications and improved function/cosmetic result. An article published in 1993 reported that 32% did not wish for phalloplasty because of too many operations, 44% risk of surgical failure, and 42% not pleased with cosmetic result (Hage & De Graaf, 1993). The improvements in surgical technique strive for a one-stage, esthetic penis with erogenous and tactile sensation, the ability to void while standing, and sexual intercourse (Hage & Bloem, 1993). In a more recent article published in 2008, phalloplasties had 5% flap loss, 37% urinary fistula, and 90% satisfied with cosmetic appearance (Leriche et al., 2008). In 2011, Doornaert et al. reported 11% phalloplasty flap revision, urinary complications in 40%, and prosthetic complications in 41% requiring removal or revision surgery due to infection, erosion, dysfunction, or leakage (Doornaert et al., 2011). Even though some patients develop severe surgical complications they seldom regret having undergone surgery. Furthermore, fewer than 2% of patients expressed regret after therapy (Coleman et al., 2012). In our data alone, only 1% of patients reported having some degree of regret after surgery and 41% desire to have a phalloplasty in the future. Forearm based phalloplasty has been shown to have 97% of patients being fully satisfied with cosmesis and size of the phallus. Sensation of the phallus was reported by 86% of patients (Garaffa et al., 2010).

Whether patients agreed to undergo mastectomy alone or multiple gender affirming surgical procedures, our data focused on the impact on self-image, dating life, social life, employment, psychiatric morbidities, and the hurdles that transgender patients face during their surgical transition. More recently, there have been reports claiming that trans male patients who undergo mastectomy improve their self-image and social interaction with no regret (Cohen et al., 2019; Nelson et al., 2009; Owen-Smith et al., 2018; van de Grift et al., 2016; Wilson et al., 2018). The improvement in both self-image and social interaction was statistically significant in our population as well. Patients’ sex and dating life was also significantly improved which has been further supported by Klein et al who showed that sexual desire appears unequivocally to increase (Klein & Gorzalka, 2009). It was shown that there was an increase in frequency of masturbation following gender affirming surgery (De Cuypere et al., 2005). Furthermore, the rates of orgasm have generally been found to be consistently higher in trans male patients after undergoing gender affirming surgery (Klein & Gorzalka, 2009). Overall, the quality of life and employment rate improved after surgery as well.

It is well known that gender dysphoria often co-exists with psychiatric conditions. Our data help fill the gap that exists in showing that the following psychiatric morbidities are at least somewhat improved after undergoing gender affirming surgery: depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, social phobia, panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and substance abuse. In the memory of our patients, it was common to have at least one of these conditions in addition to other concerns that delayed them from completing their surgical transition. At the time of the survey, only 18% admitted to experiencing what they perceived as “complications” from the surgery, 5% experienced difficulty with price, 10% had social non-acceptance, 14% were unable to pass, 5% felt mistreatment by a member of the medical team, and 2% were dissatisfied with the results. Clearly, prospective outcome studies using validated instruments will be necessary to further support our initial self-reported data. Nonetheless, these favorable numbers should be encouraging to transgender patients seeking to undergo gender affirming surgery.

Many of the patients who were surveyed plan on undergoing additional operations. The vast majority of patients who responded had undergone bilateral mastectomy. We had an acceptable response rate of 36%. However, limitations of our study include few patients with a history of phalloplasty. Furthermore, our survey was not rigorously validated. However, we feel as though the questions and descriptions were kept simple in order to minimize inaccurate responses. As in most areas of gender affirming surgery, additional prospective data using validated quality of life instruments are ultimately necessary in order to more definitively support our initial conclusions. We chose to focus on trans male patients instead of grouping in trans female and non-binary identifying individuals to limit the number of confounding variables. Similar studies should be performed in these patient populations. Since this study was based on an anonymous survey, we were not able to link patients to complications that might have occurred post-operatively. This study is primarily aimed at understanding the patient’s experience so we asked them to report if they had any complications from the surgery.

Conclusion

Gender affirming surgery is becoming more prevalent within the transgender community. Therefore, it is important to provide patients, surgeons, and insurance companies with expected outcomes of the procedures along with the potential risks and benefits. After surveying 246 post-surgical trans male patients, they reported a significant subjective improvement in overall quality of life; including benefits to self-image, sex, dating, socializing, employment, and psychiatric morbidities. The initial hesitations to having surgery such as regret and potential complications were found to occur much less often than patients had anticipated. Overall, patients reported that gender affirming surgery had a very positive impact on their lives and they strongly supported increased access. Future work should focus on development of well-designed prospective studies to help identify which patients benefit most from gender affirming surgery.

Appendix 1. Survey Questionnaire.

How long after starting your transition did you wait until you had a procedure to modify your body?

1-2 years

2-4 years

4-6 years

6-10 years

>10 years

At what age did you have your first transgender operation?

<16 years old

16-17 years old

18-20 years old

21-25 years old

26-30 years old

31-40 years old

41-50 years old

51-60 years old

>60 years old

How long were you on hormonal therapy prior to your first procedure?

<1 year

1-2 years

2-5 years

>5 years

Overall, how did you feel about your body prior to having any surgical procedures? (Please rate response from 1-5)

Uncomfortable, and I don’t even like to look at myself naked

2

Comfortable, and I wouldn’t mind having a significant other seeing me naked

4

5- Very comfortable, and I’m not afraid to show off my body.

Prior to having any surgical procedures, how was your sex/dating life? (Please rate response from 1-5)

Not sexually active or unable to have a fulfilling dating experience

Rare sexual activity or dating experiences

Some sexual or dating activity, but not as much as I would like

Mostly satisfied with the amount of sexual or dating activity

Very satisfied with my dating life or level of sexual activity

Overall, how was your social life prior to having your first surgery? (Please rate response from 1-5)

I avoided being around other people

2

I only liked being around close friends and family

4

5- I loved being around other people

Did you have any of the following fears about surgery prior to having any procedures done? (Please check all that apply)

Not being able to pass as my gender

Complications from the surgery

Social Expectations or Nonacceptance of my decision

Potential Regret after having surgery

Inability to afford the procedure

Mistreatment by a member of the medical team

None of the above

Other (please specify)

Do you have a history of any of the following? (check all that apply)

Depression

Anxiety

Substance Abuse

Genital Mutilation

Suicide Attempt

Panic Disorder

Fear of being in a social setting (Social Phobia)

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

None of the Above

Other (please specify)

Did you have any problems with employment prior to having any surgery?

Yes

No

How many of the following procedures have you already completed? (check all that apply)

Mastectomy (Top surgery, removal of breast tissue)

Phalloplasty (Creation of penis using Metoidioplasty)

Phalloplasty (Creation of penis using skin from thigh)

Phalloplasty (Creation of penis using skin from arm)

Creation of Scrotum with Testicle Prosthesis

Insertion of Prosthesis to Achieve Erection

Hysterectomy

Facial Masculinization

Other (please specify)

Which of the following was your most recent procedure?

Mastectomy (Top surgery, removal of breast tissue)

Phalloplasty (Creation of penis using Metoidioplasty)

Phalloplasty (Creation of penis using skin from thigh)

Phalloplasty (Creation of penis using skin from arm)

Creation of Scrotum with Testicle Prosthesis

Insertion of Prosthesis to Achieve Erection

Hysterectomy

Facial Masculinization

Other (please specify)

If you have NOT had bottom surgery, which of the following reasons apply? (check all that apply)

Price

Too many complications

Too far to travel

I am happy now the way that I am

I plan to have bottom surgery in the future

I have already had bottom surgery

Other (please specify)

How long has it been since your last procedure?

<1 month

1-6 months

-

6 months - 1 year

1 year

Overall, how do you feel about your body now? (Please rate response from 1-5)

Uncomfortable, and I don’t even like to look at myself naked

2-

Comfortable, and I wouldn’t mind having a significant other seeing me naked.

4-

5- Very comfortable, and I’m not afraid to show off my body.

After your most recent procedure, how is your sex/dating life? (Please rate response from 1-5)

Not sexually active or unable to have a fulfilling dating experience

Rare sexual activity or dating experiences

Some sexual or dating activity, but not as much as I would like

Mostly satisfied with the amount of sexual or dating activity

Very satisfied with my dating life or level of sexual activity

Overall, how is your social life since your last surgery? (Please rate response from 1-5)

I avoid being around other people

2-

I only like being around close friends and family

4-

5- I love being around other people

Have you had any problems with employment since your last surgery?

Yes

No

Since your last procedure, did you actually experience any of the following? (Please check all that apply)

Not being able to pass as my gender

Complications from the surgery

Social Expectations or Nonacceptance of my decision

Potential Regret after having surgery

Inability to afford the procedure

Mistreatment by a member of the medical team

None of the above

Other (please specify)

If you had any of the following prior to surgery, which of these have improved? (check all that apply)

Depression

Anxiety

Substance Abuse

Genital Mutilation

Suicide Attempt

Panic Disorder

Fear of being in a social setting (Social Phobia)

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

None of the Above

Other (please specify)

Which of the following additional procedures would you like to have done in order to feel comfortable in your body? (check all that apply)

Mastectomy (Top surgery, removal of breast tissue)

Phalloplasty (Creation of penis using Metoidioplasty)

Phalloplasty (Creation of penis using skin from thigh)

Phalloplasty (Creation of penis using skin from arm)

Creation of Scrotum with Testicle Prosthesis

Insertion of Prosthesis to Achieve Erection

Hysterctomy

Facial Masculinization

Other (please specify)

Do you feel as though your quality of life has improved since surgery? (Please rate response from 1-5)

Not Improved

2-

3-

4-

5- Very Much Improved

From your experience, would you change anything about your surgical transition? (If yes, please explain)

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Berry, M. G., Curtis, R., & Davies, D. (2012). Female-to-male transgender chest reconstruction: A large consecutive, single-surgeon experience. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery: JPRAS, 65(6), 711–719. 10.1016/j.bjps.2011.11.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, W. A., Shah, N. R., Iwanicki, M., Therattil, P. J., & Keith, J. D. (2019). Female-to-male transgender chest contouring. Annals of Plastic Surgery, 83(5), 589–593. 10.1097/SAP.0000000000001896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, E., Bockting, W., Botzer, M., Cohen-Kettenis, P., DeCuypere, G., Feldman, J., Fraser, L., Green, J., Knudson, G., Meyer, W. J., Monstrey, S., Adler, R. K., Brown, G. R., Devor, A. H., Ehrbar, R., Ettner, R., Eyler, E., Garofalo, R., Karasic, D. H., … Zucker, K. (2012). Standards of care, for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender nonconforming people. International Journal of Transgenderism, 13(4), 165–232. 10.1080/15532739.2011.700873 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Cuypere, G., T'Sjoen, G., Beerten, R., Selvaggi, G., De Sutter, P., Hoebeke, P., Monstrey, S., Vansteenwegen, A., & Rubens, R. (2005). Sexual and physical health after sex reassignment surgery. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 34(6), 679–690. 10.1007/s10508-005-7926-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doornaert, M., Hoebeke, P., Ceulemans, P., T’Sjoen, G., Heylens, G., & Monstrey, S. (2011). Penile reconstruction with the radial forearm flap: An update. Handchirurgie Mikrochirurgie Plastische Chirurgie, 43(04), 208–214. 10.1055/s-0030-1267215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garaffa, G., Christopher, N. A., & Ralph, D. J. (2010). Total phallic reconstruction in female-to-male transsexuals. European Urology, 57(4), 715–722. 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hage, J. J., & Bloem, J. J. (1993). Review of the literature on construction of a neourethra in female-to-male transsexuals. Annals of Plastic Surgery, 30(3), 278–286. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8494313 10.1097/00000637-199303000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hage, J. J., & De Graaf, F. H. (1993). Addressing the ideal requirements by free flap phalloplasty: Some reflections on refinements of technique. Microsurgery, 14(9), 592–598. 10.1002/micr.1920140910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hage, J. J., & Karim, R. (2000). Ought GIDNOS get nought? Treatment options for nontranssexual gender dysphoria. Plastic and Reconstuctive Surgery, 105(3), 1222–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein, C., & Gorzalka, B. B. (2009). Sexual functioning in transsexuals following hormone therapy and genital surgery: A review. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 6(11), 2922–2939. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01370.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leriche, A., Timsit, M. O., Morel-Journel, N., Bouillot, A., Dembele, D., & Ruffion, A. (2008). Long-term outcome of forearm flee-flap phalloplasty in the treatment of transsexualism. BJU International, 101(10), 1297–1300. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07362.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, L., Whallett, E. J., & McGregor, J. C. (2009). Transgender patient satisfaction following reduction mammaplasty. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery: JPRAS, 62(3), 331–334. 10.1016/j.bjps.2007.10.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen-Smith, A. A., Gerth, J., Sineath, R. C., Barzilay, J., Becerra-Culqui, T. A., Getahun, D., Giammattei, S., Hunkeler, E., Lash, T. L., Millman, A., Nash, R., Quinn, V. P., Robinson, B., Roblin, D., Sanchez, T., Silverberg, M. J., Tangpricha, V., Valentine, C., Winter, S., … Goodman, M. (2018). Association between gender confirmation treatments and perceived gender congruence, body image satisfaction, and mental health in a cohort of transgender individuals. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 15(4), 591–600. 10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.01.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratnam, S. S., & Ilancheran, A. (1987). Sex reassignment surgery in the male transsexual. British Journal of Hospital Medicine, 38(3), 212–213. 10.1055/s-0031-1281493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Grift, T. C., Kreukels, B. P. C., Elfering, L., Özer, M., Bouman, M.-B., Buncamper, M. E., Smit, J. M., & Mullender, M. G. (2016). Body image in transmen: multidimensional measurement and the effects of mastectomy. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 13(11), 1778–1786. 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, S. C., Morrison, S. D., Anzai, L., Massie, J. P., Poudrier, G., Motosko, C. C., & Hazen, A. (2018). Masculinizing top surgery: A systematic review of techniques and outcomes. Annals of Plastic Surgery, 80(6), 679–683. 10.1097/SAP.0000000000001354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]