Abstract

Background: During the transition process, transgender individuals may require voice and communication services. Speech-language pathologists are increasingly involved in rendering clinical services and assisting transgender clients in voice and communication therapy. Previous studies in different countries have highlighted the lack of competence expressed by the speech-language pathologists toward serving the members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer communities. Presently, no such findings are available in the Indian context. Thus, a need was felt for identifying the concerns toward treatment for transgender individuals in speech-language pathology settings in India.

Aim: The aim of the present study was to assess the knowledge, comfort levels and attitudes of speech-language pathologists practicing in India regarding the transgender community.

Method: An online survey method was used to assess the knowledge and attitudes among speech-language pathologists working in India toward the transgender community.

Results: The findings of the study revealed higher comfort levels as compared to self-rated knowledge levels in addressing issues related to transgender healthcare. Evidence-based practices toward transgender healthcare emerged as the topic needing more information. The study also helped to identify several moral beliefs and practices for voice therapy for the transgender population.

Conclusion: There is a strong need to educate the speech language pathologists toward transgender healthcare in order to promote better cultural competence. The findings of the present study help to identify the lacunae in knowledge as well as to highlight the need to have continuing education programs in this area.

Keywords: Attitudes, clinical services, questionnaire, speech-language pathologists, transgender, voice, voice therapy

Introduction

Transgender is an umbrella term that refers to individuals whose gender identity differs from the sex assigned to them at birth. These individuals wish to live and be identified as a gender other than the one assigned at birth. They may or may not desire to undergo a surgical modification for their primary or secondary sex characteristics to match their gender identity (Denny et al., 2007). The transgender community belongs to a marginalized section of the society and often face difficulties related to finances, culture, legal and social rights. The main problems include lack of educational opportunities, unemployment, discrimination, homelessness, lack of medical facilities as well as issues related to health and marriage (Atheeque & Nishanthi, 2016; Brown et al., 2018; Heng et al., 2018).

Voice is another concern that transgender individuals may have and which can affect overall communication needs and quality of life. Alignment of visual gender presentation and voice can be vital to a successful transition for some individuals. A significant factor in successfully and happily living as a transgender person is the ability to be perceived by other people as one’s felt gender, especially in social and occupational circles (Davies & Goldberg, 2006). Thus, as a part of the transition process, transgender individuals may require voice and communication services. These individuals seek voice and communication services from speech-language pathologists (SLPs) to improve their quality of life and require culturally and clinically competent clinicians.

The World Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) have specified standards of care for assisting a client to achieve voice and communication patterns, which are congruent with their gender identity (Coleman et al., 2012). The speech-language pathologists need to consider and assess aspects of gendered voice, speech, and language, which involves voice quality, resonance, pitch, articulation, intonation patterns, loudness, prosody, word choices, style of communication as well as non-verbal communication (Coleman et al., 2012). It is however, challenging for transgender individuals to find speech-language pathologists who are supportive and skilled in the communication and masculinization/feminization voice therapy process. This barrier to essential health care for the transgender community is one such example of the health disparities seen within the LGBTQ population (Hancock & Haskin, 2015).

Research has highlighted the lack of competence expressed by the speech-language pathologists toward serving the members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) communities (Taylor et al., 2018). Studies have been conducted among speech-language pathologists (SLPs) across the world to explore their knowledge and attitudes regarding members of the LGBTQ community. Hancock and Haskin (2015) conducted an online survey of SLPs from the United States, Australia, Canada and New Zealand to assess their knowledge and attitude toward the LGBTQ groups. The findings of the study noted that the SLPs are knowledgeable about these minority groups. However, there is further need to promote LGBTQ cultural competency and therapeutic expertise among the SLPs. Sawyer et al. (2014) and Litosseliti and Georgiadou (2019) reported similar findings in their survey among SLPs in Illinois (USA) and Taiwan, respectively. The SLPs in both these studies displayed positive attitudes toward transgender individuals, but often felt incompetent to provide voice and communication therapy to this population. The findings of the studies among SLPs have indicated the need to have more inclusion of topics related to the assessment and management of transgender individuals in the curriculum. In a survey among members of the National Black Association of Speech-Language and Hearing, results indicated that SLPs felt that serving the transgender community was their ethical obligation, but only a few members felt their training was adequate (Matthews et al., 2017).

If adequate training is provided to the healthcare providers, this will facilitate a better understanding of the transgender culture, which would help in promoting better competence in imparting treatment. This training would also improve their inclusion into society (Hancock & Haskin, 2015). There is a crucial need for identifying the concerns toward treatment for transgender individuals in speech-language pathology settings in India. In order to develop knowledgeable and culturally competent professionals, it is essential to understand their knowledge levels, attitudes and comfort levels in dealing with health concerns of transgender individuals. Thus, the present study aimed to assess the knowledge, comfort levels and attitudes of SLPs practicing in India regarding the transgender community.

Method

The study was conducted in two phases. Phase I involved the development and validation of the questionnaire and phase II involved data collection from speech-language pathologists. All procedures were in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. The participants were informed about the study and participation was voluntary.

Phase I: Development and validation of the questionnaire

A self-reported questionnaire was used to gather data on the knowledge and attitudes of SLPs working in India toward the transgender community. The questionnaire was adapted from a previous study on the knowledge and attitudes of SLPs toward the LGBTQ community (Hancock & Haskin, 2015) to suit the present study objective. Permission was taken from the authors for the adaptation and use of the questionnaire. The questionnaire was content validated by three speech-language pathologists with a minimum of 5 years of experience and expertise in voice and voice disorders. Each question had to be rated using a rating scale: relevant, somewhat relevant, quite relevant and relevant by every expert (Davis, 1992). Only the items rated as relevant and quite relevant were included in the final questionnaire. The content validity index for Scale (S-CVI) developed by Polit and Beck (2006) was used to calculate S-CVI. A S-CVI score of 0.9 was obtained for the final questionnaire, indicative of excellent content validity (Polit & Beck, 2006). The final questionnaire comprised of 19 questions. The questions were broadly classified under demographic details, clinical exposure to transgender individuals and knowledge of terminology, comfort levels in addressing transgender assessment and management, healthcare team members, and domains on transgender patient care where more information is needed. Further, open-ended questions addressed knowledge of voice feminization treatment practices and feelings about serving the transgender community were included.

Phase II: Data collection and analysis

The study was conducted using a cross-sectional self-reported internet-based study design. The finalized questionnaire was made available as a Google Form, and an email link for the same was generated. The link was then mailed to speech-language pathologists with more than one year of experience in academic and/or clinical settings in India registered with the Indian Speech and Hearing Association. The contact details for the SLPs were procured from the Indian Speech and Hearing Association. However, these details also include SLPs who reside outside India, are not practicing, or pursuing further studies. Thus, it was difficult to ascertain the exact number of SLPs who fit the inclusion criteria. Data was collected between January to August 2019 using a snowball sampling procedure. No personal information was collected to maintain anonymity. All responses were saved in Google documents on Google drive.

Data analysis

All continuous variables were summarized using mean and standard deviation, while discrete variables were summarized using frequency and percentage. The terminology knowledge, comfort and attitude responses were computed using mean, standard deviation, median, interquartile range, and skewness. The frequency and percentage was determined for the correct scores in the knowledge domain. All statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS 15.

Results

One hundred and thirty-nine speech-language pathologists responded to the survey. Eight respondents were students, and thus, their responses were eliminated from the survey, while six respondents refused to participate in the study citing as a reason their religious beliefs. Thus, responses of 125 speech-language pathologists were analyzed. All the respondents were Indian citizens and practising in India. Table 1 displays the demographic details of the speech-language pathologists who participated in the study.

Table 1.

Demographic details of the speech language pathologists.

| Mean ± SD | Range | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age experience | 28 ± 5.13 years | 22 to 46 years | |

| 5 ± 4.8 years | 1–30 years | ||

| Percentage (%) | |||

| Gender | Male | 78.4% | |

| Female | 21.6% | ||

| Highest qualification | Bachelors | 36% | |

| Masters | 60.8% | ||

| Doctorate | 3.2% | ||

The respondents were asked to indicate if assessment and management of the transgender community was covered as a part of their curriculum. Only 37.6% indicated in affirmation, 36% responded in negation while 26.4% said it was briefly covered. More than 75% (n = 95) had never interacted or treated a transgender individual as a part of their clinical practice.

Knowledge of terminology

Four questions were aimed toward assessing the knowledge levels of the SLPs toward different terminologies related to the transgender community. The SLPs were asked to indicate the correct symbol used to represent the transgender community. Six-four percent replied correctly, while 36% replied incorrectly. Less than 51% of the respondents could answer the next three questions correctly, which were definitions for different terminologies such as intersex (28.8%), transgender (44%), and gender identity (51%). Overall the distribution of correct responses was as follows; 0 answers correct (8%), 1 correct (29.6%), 2 correct (37.6%), 3 correct (16%) and all 4 correct (8.8%). Two true/false questions were included related to healthcare experiences among transgender individuals. The response for the statement ‘Many transgender report negative interactions with healthcare providers’ was as follows: 28.8% responded as true, 20% as false, while 51.2% responded as ‘I don’t know’. Further, for the statement ‘Most transgender feel their identities should not affect the care they receive from healthcare providers’, 35.2% responded as true, 13.6% as false, while 51% responded as ‘I don’t know’.

Self-rated knowledge and comfort levels

The SLPs were asked to rate themselves with respect to their knowledge and comfort levels, while addressing certain healthcare aspects, such as the the process of disclosing one’s transgender identity, healthcare issues, role of SLP, voice feminization or masculinization services. SLPs displayed being more comfortable dealing with these aspects than being knowledgeable about the same. Table 2 displays the frequency and percentages of responses while Table 3 displays the summary statistics.

Table 2.

Frequency and percentages of responses for knowledge and comfort levels for SLPs.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-rated knowledge levels | Rating (1 = no knowledge, 5 = expert knowledge)* | ||||

| Process of revealing to others | 29 (23.3) | 33 (26.4) | 53 (42.4) | 7 (5.6) | 3 (2.4) |

| Healthcare issues | 30 (24) | 46 (36.8) | 33 (26.4) | 16 (12.8) | 0 |

| Role of SLP | 18 (14.4) | 30 (24) | 41 (32.8) | 26 (20.8) | 10 (8) |

| Voice feminization/masculinization | 21 (16.8) | 37 (29.6) | 36 (28.8) | 17 (13.6) | 14 (11.2) |

| Self-rated comfort levels | Rating (1 = uncomfortable, 5 = comfortable)* | ||||

| Process of revealing to others | 20 (16) | 15 (12) | 20 (24) | 28 (22.4) | 32 (25.6) |

| Healthcare issues | 8 (16.4) | 28 (22.4) | 37 (29.6) | 30 (24) | 22 (17.6) |

| Role of SLP | 3 (2.4) | 14 (11.2) | 29 (23.2) | 32 (25.6) | 47 (37.6) |

| Voice feminization/masculinization | 5 (4) | 26 (20.8) | 32 (25.6) | 28 (22.4) | 34 (27.2) |

Higher rating is indicative of higher knowledge or comfort levels.

Table 3.

Summary statistics for self-rated knowledge and comfort levels.

| Mean | SD | Median | IQR | Skewness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-rated knowledge levels | |||||

| Process of revealing to others | 2.38 | 0.98 | 3 | 1 | 0.17 |

| Healthcare issues | 2.28 | 0.97 | 2 | 1 | 0.27 |

| Role of SLP | 2.84 | 1.15 | 3 | 2 | 0.06 |

| Voice feminization/masculinization | 2.73 | 1.22 | 3 | 2 | 0.35 |

| Self-rated comfort levels | |||||

| Process of revealing to others | 3.30 | 1.39 | 3 | 3 | −0.32 |

| Healthcare issues | 3.24 | 1.17 | 3 | 2 | −0.05 |

| Role of SLP | 3.85 | 1.12 | 4 | 2 | −0.06 |

| Voice feminization/masculinization | 3.48 | 1.21 | 3 | 3 | −0.18 |

SD: Standard deviation, IQR: Interquartile range.

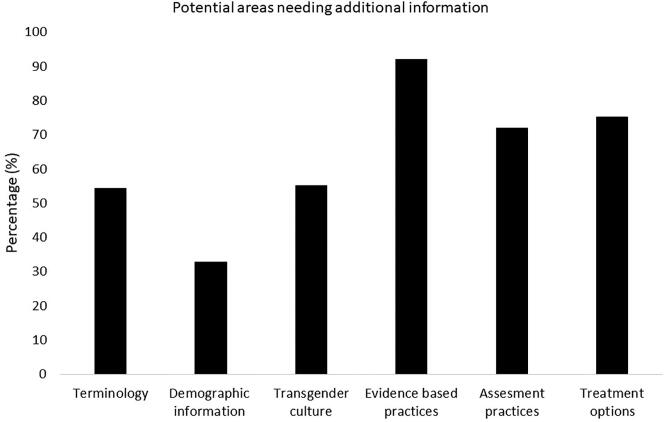

Potential areas needing additional information

The SLPs were asked to indicate the topics where they would like to have additional information. The six topic areas included the following: terminology related to transgender, demographics (related to population, distribution, etc.), transgender culture, evidence-based practices for transgender communication and voice therapy, assessment practices and treatment options. The last option was left blank so that SLPs could suggest a potential area of interest related to transgender voice and communication that they felt was missing from the survey. The responses to the open-ended question included potential areas, such as hormonal treatment options, government schemes and insurance coverage. Figure 1 depicts the responses to the six potential areas.

Figure 1.

Potential areas needing additional information.

Moral beliefs

The SLPs were asked to indicate considering their personal moral beliefs, whether there are any scenarios, which would make it difficult for them to provide quality services to a patient who belongs to the transgender community. Out of the 125 respondents, 76% responded ‘none’. The remaining 24% included lack of experience or competency, lack of social acceptance, social stigma, and being scared due to their appearance.

Team members in a multidisciplinary team

The SLPs were provided with an open ended questions: ‘Who according to you are the team members needed for a multidisciplinary team for transgender healthcare?’ All respondents provided at least two professionals (e.g., psychiatrist and speech-language pathologist) as appropriate members of the multidisciplinary team in transgender healthcare. The two most common responses were speech-language pathologist (79.2%) and psychologist (58.4%). The other professionals included general practitioner (40.8%), endocrinologist (29.6%), ENT specialist (26.4%), social worker (24%), surgeon (18.4%), gynecologist (16.8%), plastic surgeon (16%), and psychiatrist (14.4%). The least common responses included urologist (7.2%), nurse (7.2%), dietician (7.2%), dermatologist (4%), sexologist (4%), dentist (2.4%), physiotherapist (1.6%), anesthetist (1.6%), and neurologist (1.6%). Some of the SLPs also suggested the inclusion of family members (5.6%), a lawyer (3.2%) and a transgender community representative (1.6%).

Feminization therapy for male to female transgender population

The SLPs were asked to list the components typically included in feminization therapy for the female transgender population. Out of the 125 SLPs, 81 (65%) left the question blank and did not provide any answer. The remaining responses could be categorized into two main categories of (i) voice therapy and (ii) speech, language or communication therapy. Under voice therapy, the responses included breath support training, pitch raising, pitch modulation, vocal flexibility, digital manipulation, and vocal loudness. Under speech, language or communication therapy, the response included pragmatic aspects, sex-dependent difference in language use and content, articulation therapy and use of role-model.

Discussion

Speech-language pathologists are increasingly involved in providing clinical services and assisting transgender clients in voice and communication therapy. The SLPs, however, may not be adequately trained with accurate information and understanding the complexity of vocal change, its implications and treatment strategies. The present study aimed to assess the knowledge and attitudes among SLPs practising in India toward the transgender community. The findings of the study revealed higher comfort levels as compared to self-rated knowledge levels in addressing issues related to transgender healthcare. The SLPs also expressed a lack of expertise in handling issues related to voice and communication therapy for transgender individuals, however, a significant proportion were interested in learning more information related to this particular aspect of speech and language pathology.

The understating about a particular condition starts with a basic understanding of the different terminologies associated with it. The various terminologies related to the transgender community can often be confusing and cause anxiety among the professionals (Taylor et al., 2018). In the present study, fewer respondents could accurately answer the terminology-based questions for intersex, transgender and gender identity. A higher percentage of SLPs were able to identify correctly the symbol used to represent the transgender community. Hancock and Haskin (2015) reported better knowledge levels on terminology questions among graduate students as compared to practising SLPs.

The SLPs were asked to self-rate their knowledge and comfort levels while addressing certain healthcare aspects such as; the process of disclosing one’s transgender identity, healthcare issues, role of SLP, voice feminization or masculinization services. Overall, the SLPs displayed higher comfort levels as compared to the knowledge of these domains. Similar findings of higher comfort levels as compared to knowledge levels have been reported among SLPs from other countries like Australia, Canada, New Zealand and United States (Hancock & Haskin, 2015; Litosseliti & Georgiadou, 2019; Sawyer et al., 2014). These higher comfort levels could indicate the improved positive attitudes among SLPs toward this community. Low levels of knowledge on terminology as well as self-rated knowledge on healthcare aspects could be the result of a large number of SLPs indicating that assessment and management of transgender community was not covered in detail in their curriculum. A similar finding has also been reported in studies conducted across different countries (Davies & Goldberg, 2006; Hancock & Haskin, 2015). This indicates the need to increase the curriculum on transgender voice and communication treatment among speech-language pathology coursework. In this context Mahendra (2019) has provided a detailed description on the importance of integrating a teaching module on the LGBTQ community for students of speech-language pathology. The presence of such a module would improve the knowledge of students of speech-language pathology and potentially improve their attitudes and practices.

It was encouraging to note that the SLPs were interested in getting more information on different areas related to the transgender community. More than 90% of the SLPs expressed interest in knowing more on the ‘evidence-based practices available for the transgender community’. Evidence-based practices comprise of integration of expert opinion, scientific evidence and client perspectives. The SLPs expressed a keen interest in expanding their knowledge that is backed with scientific, research and clinical basis.

The personal moral beliefs toward the transgender community have an impact on the attitudes and behavior toward this particular community (Follins et al., 2014). Six SLPs had refused to participate in the study citing religious beliefs. A quarter of the respondents reported facing some hesitation in providing quality services to the transgender population due to their moral beliefs. The scenarios expressed by them are indicative of a certain amount of reluctance as well as social barriers toward the transgender community. Studies have emphasized the need to have an interdisciplinary or a multidisciplinary approach toward the provision of healthcare services for the transgender community (Hahn et al., 2019; Shipherd et al., 2016). Bachmann et al. (2017) have suggested the inclusion of obstetricians/gynaecologists, urologists, psychiatrists, endocrinologists, anesthetists, nurses, bioethicists, nutritionists as well as patient advocacy staff. The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) have emphasized that the decision-making process should involve the individual, family and multidisciplinary speciality healthcare team (Coleman et al., 2012). Further, emphasis has been given to voice and communication therapy for helping transgender individuals develop voice, verbal and non-verbal communication that facilitates conformation to their newly assigned gender. In the present study, speech-language pathologists and psychologists were rated as the most suited professionals to be members of the multidisciplinary team.

The final question in the survey was an open-ended question in which the SLPs were asked to list the components to be included in feminization therapy. Based on the literature, the most common choices to be included under feminization therapy include aspects related to the pitch and resonance (Coleman et al., 2012; Hancock & Garabedian, 2013). An recent systematic review has also emphasized on the important role played by voice therapy in transgender voice feminization. Voice therapy is preferred due to higher satisfaction levels among patients, desirable vocal pitch and noninvasive nature (Nolan et al., 2019). Ziegler et al. (2018) carried out a meta-analytic review to evaluate the effectiveness of testosterone therapy for masculinization for transgender male individuals. Their findings show the need to have a holistic management from laryngologists and speech therapists in order to increase voice and gender congruence, overcome voice problems as well as to increase the overall satisfaction with their voice. However, in the present study, only 35% of the SLPs responded to this question. These responses were categorized under voice therapy specifically and speech, language or communication therapy. The lack of any answer by a majority of SLPs could be attributed to a lack of clinical or academic exposure.

This study has a number of limitations. The participation in the study was voluntary, and the potential bias due to responses only by interested participants cannot be overlooked. The reasons for nonparticipation could be lack of knowledge, interest or moral issues. Also, it is not possible to determine nonparticipation due to not using the email regularly or perceiving the survey link as spam. Due to the sample size and data collection method, further analysis of SLPs who have treated transgender individuals was not possible. Further research needs to be aimed at analyzing the competence of the SLPs toward providing care to this population. The areas identified as SLPs where more information is required should be targeted through newsletters, articles, curriculum and continuing education programs or seminars.

Conclusion

The findings of the study revealed that SLPs have higher comfort levels as compared to self-rated knowledge levels in addressing issues related to transgender healthcare. The study also helped to identify several moral beliefs and practices for voice therapy for the transgender population. The findings help to identify the lacunae in knowledge in this area and emphasize the need for having continuing education programs in this area.

Declaration of conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Atheeque, M., & Nishanthi, R. (2016). Marginalization of transgender community: A sociological analysis. International Journal of Applied Research, 2(9), 639–641. [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann, G., Baras, J., Berner, N., Marshall, I., Salwitz, J., & Moffa, S. (2017). Transgender health care: Multi-disciplinary team approach prior to female to male confirmation surgery [3O]. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 129(5), S153–S154. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S., Kucharska, J., & Marczak, M. (2018). Mental health practitioners’ attitudes towards transgender people: A systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Transgenderism, 19(1), 4–24. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2017.1374227 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, E., Bockting, W., Botzer, M., Cohen-Kettenis, P., DeCuypere, G., Feldman, J., Fraser, L., Green, J., Knudson, G., Meyer, W. J., Monstrey, S., Adler, R. K., Brown, G. R., Devor, A. H., Ehrbar, R., Ettner, R., Eyler, E., Garofalo, R., Karasic, D. H., … Zucker, K. (2012). Standards of care for the health of transsexual, trans- gender, and gender-nonconforming people, version 7. International Journal of Transgenderism, 13(4), 165–231. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2011.700873 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davies, S., & Goldberg, J. M. (2006). Clinical aspects of transgender speech feminization and masculinization. International Journal of Transgenderism, 9(3-4), 167–196. doi: 10.1300/J485v09n03_08 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, L. L. (1992). Instrument review: Getting the most from a panel of experts. Applied Nursing Research, 5(4), 194–197.(05)80008-4 doi: 10.1016/S0897-1897(05)80008-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Denny, D., Green, J., & Cole, S. (2007). Gender variability: Transsexuals, crossdressers, and others. Sexual Health, 4, 153–187. [Google Scholar]

- Follins, L. D., Walker, J. J., & Lewis, M. K. (2014). Resilience in black lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals: A critical review of the literature. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 18(2), 190–212. doi: 10.1080/19359705.2013.828343 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, M., Sheran, N., Weber, S., Cohan, D., & Obedin-Maliver, J. (2019). Providing patient-centered perinatal care for transgender men and gender-diverse individuals: A collaborative multidisciplinary team approach. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 134(5), 959–963. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock, A. B., & Garabedian, L. (2013). Transgender voice and communication treatment: A retrospective chart review of 25 cases. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 48(1), 54–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-6984.2012.00185.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock, A., & Haskin, G. (2015). Speech-language pathologists’ knowledge and attitudes regarding lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) populations. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 24(2), 206–221. doi: 10.1044/2015_AJSLP-14-0095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heng, A., Heal, C., Banks, J., & Preston, R. (2018). Transgender peoples’ experiences and perspectives about general healthcare: A systematic review. International Journal of Transgenderism, 19(4), 359–378. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2018.1502711 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Litosseliti, L., & Georgiadou, I. (2019). Taiwanese speech–language therapists’ awareness and experiences of service provision to transgender clients. International Journal of Transgenderism, 20(1), 87–97. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2018.1553693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahendra, N. (2019). Integrating lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer issues into the multicultural curriculum in speech- language pathology: Instructional strategies and learner perceptions. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 4(2), 384–394. doi: 10.1044/2019_PERS-SIG14-2018-0007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, J. J., Sullivan, J. R., Freeman, E., & Myers, K. (2017). NBASLH’s members perceptions of communication services to trangender individuals. Journal of the National Black Association for Speech-Language and Hearing, 12(2), 100–117. [Google Scholar]

- Nolan, I. T., Morrison, S. D., Arowojolu, O., Crowe, C. S., Massie, J. P., Adler, R. K., Chaiet, S. R., & Francis, D. O. (2019). The role of voice therapy and phonosurgery in transgender vocal feminization. The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery, 30(5), 1368–1375. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000005132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2006). The content validity index: Are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Research in Nursing & Health, 29(5), 489–497. doi: 10.1002/nur.20147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer, J., Perry, J. L., & Dobbins-Scaramelli, A. (2014). A survey of the awareness of speech services among transgender and transsexual individuals and speech-language pathologists. International Journal of Transgenderism, 15(3-4), 146–163. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2014.995260 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shipherd, J. C., Kauth, M. R., & Matza, A. (2016). Nationwide interdisciplinary e-consultation on transgender care in the Veterans Health Administration. Telemedicine and e-Health, 22(12), 1008–1012. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2016.0013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S., Barr, B.-D., O'Neal-Khaw, J., Schlichtig, B., & Hawley, J. L. (2018). Refining your queer ear: Empowering LGBTQ + clients in speech-language pathology practice. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 3(14), 72–86. doi: 10.1044/persp3.SIG14.72 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler, A., Henke, T., Wiedrick, J., & Helou, L. B. (2018). Effectiveness of testosterone therapy for masculinizing voice in transgender patients: A meta-analytic review. International Journal of Transgenderism, 19(1), 25–45. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2017.1411857 [DOI] [Google Scholar]