Abstract

BACKGROUND

The incidence of retrorectal lesions is low, and no consensus has been reached regarding the most optimal surgical approach. Laparoscopic approach has the advantage of minimally invasive. The risk factors influencing perioperative complications of laparoscopic surgery are rarely discussed.

AIM

To investigate the risk factors for perioperative complications in laparoscopic surgeries of retrorectal cystic lesions.

METHODS

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of patients who underwent laparoscopic excision of retrorectal cystic lesions between August 2012 and May 2020 at our hospital. All surgeries were performed in the general surgery department. Patients were divided into groups based on the lesion location and diameter. We analysed the risk factors like type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, the history of abdominal surgery, previous treatment, clinical manifestation, operation duration, blood loss, perioperative complications, and readmission rate within 90 d retrospectively.

RESULTS

Severe perioperative complications occurred in seven patients. Prophylactic transverse colostomy was performed in four patients with suspected rectal injury. Two patients underwent puncture drainage due to postoperative pelvic infection. One patient underwent debridement in the operating room due to incision infection. The massive-lesion group had a significantly longer surgery duration, higher blood loss, higher incidence of perioperative complications, and higher readmission rate within 90 d (P < 0.05). Univariate analysis, multivariate analysis, and logistic regression showed that lesion diameter was an independent risk factor for the development of perioperative complications in patients who underwent laparoscopic excision of retrorectal cystic lesions.

CONCLUSION

The diameter of the lesion is an independent risk factor for perioperative complications in patients who undergo laparoscopic excision of retrorectal cystic lesions. The location of the lesion was not a determining factor of the surgical approach. Laparoscopic surgery is minimally invasive, high-resolution, and flexible, and its use in retrorectal cystic lesions is safe and feasible, also for lesions below the S3 level.

Keywords: Laparoscopic excision, Retrorectal cystic lesions, Minimally invasive, Risk factors, Perioperative complications

Core Tip: The incidence of retrorectal tumors is low, and no consensus has been reached regarding the most optimal surgical approach. Advantages of laparoscopic approach has been demonstrated in this field. We retrospectively reviewed the patients who underwent laparoscopic excision of retrorectal cystic lesions in our center. This study aimed to investigate the risk factors for perioperative complications in laparoscopic surgeries of retrorectal cystic lesions. We also evaluated the feasibility and safety of laparoscopic excision of retrorectal cystic lesions below the S3 Level.

INTRODUCTION

Retrorectal cystic lesions are located in the space between the sacrum and the rectum, also called presacral cysts. The incidence of these lesions is 1/40000[1]. Common lesions include epidermoid/dermoid cysts, tailgut cysts, and cystic teratomas. Most lesions are benign, but teratomas have a 5%-10% risk of malignant transformation[2-4]. Treatment of retrorectal lesions is surgical. The surgical approach was chosen based on the tumor's location, size, and relationship with the surrounding viscera. Common approaches include transsacral (posterior), abdominal (anterior), and combined abdominosacral approaches[5,6].

The incidence of retrorectal lesions is low, and no consensus has been reached regarding the surgical approach. Retrospective investigations at some medical centers reported that most operations adopted the transabdominal or transsacral approach[5,7,8]. It was proposed that the surgical approach should be determined based on the anatomical relationship between the tumor and the 3rd sacral vertebra level(S3). Specifically, tumors under the S3 Level should be accessed via the transsacral approach and those above the S3 Level via the abdominal approach[9]. However, strong evidence is still lacking to support this empirical preference.

In the mid-1990s, laparoscopic excision of retrorectal cystic lesions was first reported[10]. To date, most studies on laparoscopy in this disease have been case reports, except for some small retrospective studies[11-13]. We used the experience of the literatures of retrospective studies with large sample size on risk factors related to perioperative complications of retrorectal tumor[14-16]. Factors included the general condition of the patient such as age, body mass index (BMI) and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification. Factors associated with surgery included surgical approach, tumor size, and tumor location. We aimed to investigate the risk factors for perioperative complications in laparoscopic surgeries of retrorectal cystic lesions. We can also evaluate the feasibility and safety of laparoscopic excision of retrorectal cystic lesions below the S3 Level.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient characteristics

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of patients who underwent laparoscopic excision of retrorectal cystic lesions between August 2012 and May 2020 at our hospital. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Diagnosis of retrorectal cystic lesion before surgery; and (2) Underwent laparoscopic excision of the retrorectal cystic lesion with or without the combined use of the transsacral approach. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Open abdominal or transsacral operations; and (2) Surgical pathology report revealed solid tumors such as lipoma, fibroma, gastrointestinal stromal tumors, and neuroendocrine tumors.

We divided the patients into two groups based on the relative position of the upper margin of the lesion to the level at the lower margin of the S3 vertebra. The two groups were named under and above-S3 groups. We also grouped patients based on whether the diameter of the lesion reached 10 cm. Patients were divided into smaller lesion (d < 10 cm) and massive-lesion (d ≥ 10 cm) groups. In both pairs of groups, we compared the patients’ age, BMI, type 2 diabetes mellitus, systemic arterial hypertension, ASA classification, history of abdominal surgery, previous management at other hospitals, clinical manifestation, rectal examination, operation duration, blood loss, perioperative complications, postoperative length of hospital stay, and readmission rate within 90 d. The ASA classification reflected comorbidities that some patients presented. Perioperative complications were reported using the Clavien-Dindo (CD) classification. Severe complications were defined by a CD classification of 3a or higher.

After discharge, patients were scheduled for regular follow-ups (every 6 mo in the first 2 years, every 1 year thereafter). Additional information was collected via telephone interviews conducted by a specific researcher.

Surgical procedures

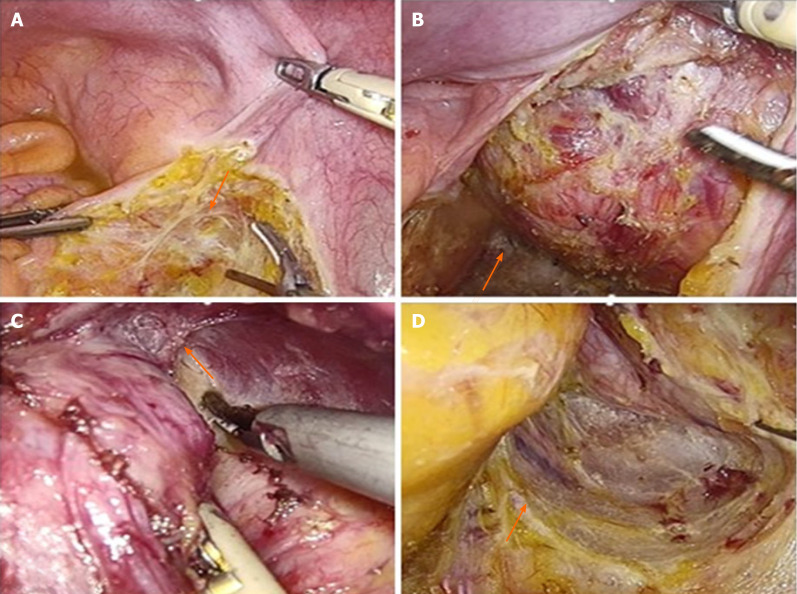

After anesthesia induction, the patient was placed in the lithotomy position. Usually, 4-5 trocars were used, which were placed in the anterior resection of rectal cancer. Based on the location of the tumor, an incision was made on the left (or right) side of the mesorectum, exposing the retrorectal space (Figure 1A). The hypogastric plexus was protected. To find the lesion, we dissected the retrorectal space and mobilized the rectum and mesorectum to the front (Figure 1B). The capsule of the lesion was exposed and dissected along the capsule. In most cases, we first dissected the top of the lesion and then dissected the lateral wall, reaching the attachment points of the pelvic floor muscles (Figure 1C). When dissecting the medial wall and base of the lesion, the rectal wall was carefully protected. The rectum could be pushed to the other side to achieve en bloc excision. Throughout the operation, the pelvic autonomous nerves and the presacral venous plexus should be carefully protected (Figure 1D). The fascia of the levator ani muscle was sometimes resected for lesions extending to the pelvic floor. For very large cysts, after dissecting the pelvic floor, the cystic fluid was intentionally aspirated to reduce tension, facilitating en bloc excision. The specimens were removed using a retrieval bag. After irrigation and bleeding control, a drainage tube was placed on the pelvic floor.

Figure 1.

Important steps in the laparoscopic excision technique of retrorectal lesions. A: An incision was made on the left side of the mesorectum; B: Dissection the retrorectal space and mobilized the rectum and mesorectum to the front; C: Dissection the top of the lesion and then dissected the lateral wall, reaching the attachment points of the pelvic floor muscles; D: Protection of the pelvic autonomous nerves and the presacral venous plexus.

Statistical analysis

SPSS statistical software (version 26.0, for Windows) was used for data analysis. Variables following a normal distribution were reported as median or mean ± SD. The t-test and rank-sum test were used to analyze quantitative data. Enumeration data were analyzed using χ2 and Fisher tests and are reported as numbers or percentages. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Statistically significant variables in the univariate analyses were included in the multivariate analysis using the logistic regression of ordinal categorical variables. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

A total of 62 patients were included in this study. Five of them were men and 57 were women, with a male to female ratio of 1:11.4. The age at surgery was 15 to 70 years, with a mean age of 37.6 ± 12.9 years. The range of body mass index (BMI) was 17.6 to 35.3 kg/m2, with a mean of 24.5 ± 3.8 kg/m2. Severe perioperative complications occurred in seven patients. Severe complications were defined by a CD classification of 3a or higher. Prophylactic transverse colostomy was performed in four patients with suspected rectal injury. Two patients underwent puncture drainage due to postoperative pelvic infection. One patient underwent debridement in the operating room due to incision infection.

Under- and above-S3 groups

Twenty-three patients were included in the under-S3 group and 39 patients in the above-S3 group. Patient characteristics are detailed in Table 1. No significant differences were observed in baseline characteristics such as age, BMI, and ASA class (P > 0.05). There was no significant difference in the size of lesions between the two groups (above-S3, 8.3 ± 3.5 cm; under-S3, 8.2 ± 2.8 cm; P > 0.05). There was also no significant difference in operation duration (above-S3, 132.9 ± 66.2 min; under-S3, 139.4 ± 56.9 min; P > 0.05) and blood loss (above-S3, 61.8 ± 130.0 mL; under-S3, 67.4 ± 101.8 mL, P > 0.05). No significant differences in perioperative complications or postoperative length of hospital stay were observed. Three patients in the above-S3 group and one in the under-S3 group were readmitted within 90 d of discharge.

Table 1.

Comparisons of the perioperative variables between two groups (n = 62)

| Variables |

No. (%) or mean ± SD

|

|

|

|

Above-S3, n = 39

|

Under-S3, n = 23

|

P

value

|

|

| Age, yr | 38.7 ± 12.4 | 35.8 ± 13.8 | 0.387 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.5 ± 3.5 | 23.5 ± 4.2 | 0.963 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 0.623 | ||

| Yes | 2 (5.1) | 2 (8.7) | |

| No | 37 (94.9) | 21 (91.3) | |

| Hypertension | 0.356 | ||

| Yes | 5 (12.8) | 5 (21.7) | |

| No | 34 (87.2) | 18 (78.3) | |

| ASA classification | 0.744 | ||

| Class I | 27 (69.2) | 15 (65.2) | |

| Class II | 12 (30.8) | 8 (34.8) | |

| Previous abdominal surgery | 0.838 | ||

| Yes | 21 (53.8) | 13 (56.5) | |

| No | 18 (46.2) | 10 (43.5) | |

| Previous treatment | 0.836 | ||

| Yes | 6 (15.4) | 4 (17.4) | |

| No | 33 (84.6) | 19 (82.6) | |

| Symptomatic | 0.602 | ||

| Yes | 16 (41.0) | 11 (47.8) | |

| No | 23 (59.0) | 12 (52.2) | |

| Digital rectal examination | 0.764 | ||

| Positive | 31 (79.5) | 19 (82.6) | |

| Negative | 8 (20.5) | 4 (17.4) | |

| Tumor size, cm | 8.3 ± 3.5 | 8.2 ± 2.8 | 0.882 |

| Operation duration, min | 132.9 ± 66.2 | 139.4 ± 56.9 | 0.694 |

| Blood loss, mL | 61.8 ± 130.0 | 67.4 ± 101.8 | 0.860 |

| Perioperative complications | 0.146 | ||

| Yes | 18 (46.2) | 15 (65.2) | |

| No | 21 (53.8) | 8 (34.8) | |

| Severe complications1 | 0.520 | ||

| Yes | 4 (10.3) | 3 (13.0) | |

| No | 35 (89.7) | 20 (87.0) | |

| Postoperative length of hospital stay,d | 6.5 ± 3.1 | 7.5 ± 4.4 | 0.296 |

| Readmission within 90 d | 0.524 | ||

| Yes | 3 (7.7) | 1 (4.3) | |

| No | 36 (92.3) | 22 (95.7) | |

Severe complications are defined as perioperative complications of Clavien-Dindo grade 3a or higher.

Smaller- and massive-lesion groups

The smaller-lesion group included 24 patients with a lesion diameter of less than 10 cm. The massive-lesion group included 38 patients whose lesion diameters were equal to or larger than 10 cm. Patient characteristics are detailed in Table 2. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics, such as age, BMI, and ASA class (P > 0.05). The mean lesion diameter was 11.5 ± 2.3 cm in the massive-lesion group and 6.2 ± 1.5 cm in the smaller-lesion group. No significant difference was observed in the operation duration, blood loss, or complications of CD ≥ 2. A significant difference was observed in complications of CD 3a or higher. Six patients in the massive lesion group and one in the small lesion group had such complications (P < 0.05). The postoperative length of hospital stay was not significantly different between the groups. Three patients in the massive-lesion group and one in the smaller tumor group were readmitted within 90 d of discharge.

Table 2.

Comparisons of the perioperative variables between two groups (n = 62)

| Variables |

No. (%) or mean ± SD

|

|

|

|

Massive-lesion, n = 24

|

Smaller-lesion, n = 38

|

P

value

|

|

| Age, yr | 36.6 ± 13.5 | 39.3 ± 11.8 | 0.426 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.8 ± 3.1 | 22.7 ± 2.8 | 0.07 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 0.289 | ||

| Yes | 3 (12.5) | 1 (2.6) | |

| No | 21 (87.5) | 37 (97.4) | |

| Hypertension | 0.927 | ||

| Yes | 4 (16.7) | 6 (15.8) | |

| No | 20 (83.3) | 32 (84.2) | |

| ASA classification | 0.678 | ||

| Class I | 17 (70.8) | 25 (65.8) | |

| Class II | 7 (29.1) | 13 (34.2) | |

| Previous abdominal surgery | 0.660 | ||

| Yes | 14 (58.3) | 20 (52.6) | |

| No | 10 (41.7) | 18 (47.4) | |

| Previous treatment | 0.027a | ||

| Yes | 7 (29.2) | 3 (7.9) | |

| No | 17 (70.8) | 35 (92.1) | |

| Symptomatic | 0.416 | ||

| Yes | 12 (50.0) | 15 (39.5) | |

| No | 12 (50.0) | 23 (60.5) | |

| Digital rectal examination | 0.924 | ||

| Positive | 20 (83.3) | 30 (78.9) | |

| Negative | 4 (16.6) | 8 (21.1) | |

| Tumor location | 0.258 | ||

| Above-S3 | 13 (54.2) | 26 (68.4) | |

| Under-S3 | 11 (45.8) | 12 (31.6) | |

| Tumor size, cm | 11.5 ± 2.3 | 6.2 ± 1.5 | 0.000a |

| Operation duration, min | 183.6 ± 57.5 | 104.7 ± 43.7 | 0.000a |

| Blood loss, mL | 117.1 ± 175.7 | 30.3 ± 36.7 | 0.004a |

| Perioperative complications | 0.027a | ||

| Yes | 17 (70.8) | 16 (42.1) | |

| No | 7 (29.2) | 22 (57.9) | |

| Severe complicationsa | 0.022a | ||

| Yes | 6 (25.0) | 1 (2.6) | |

| No | 18 (75.0) | 37 (97.4) | |

| Postoperative length of hospital stay,d | 7.7 ± 4.6 | 6.3 ± 2.9 | 0.111 |

| Readmission within 90 d | 0.019a | ||

| Yes | 4 (16.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| No | 20 (83.3) | 38 (100.0) | |

Severe complications are defined as perioperative complications of Clavien-Dindo grade 3a or higher.

P value < 0.05 indicates the statistical difference.

Risk factor for perioperative complications

All 62 patients underwent laparoscopic excision of the retrorectal cystic lesions. In 5 patients, a combined transsacral approach was used for laparoscopic surgery. Univariate logistic regression showed that lesion diameter was a risk factor for perioperative complications. In multivariate analysis, we included factors that could potentially affect complications, such as lesion location, history of abdominal surgery, and previous treatment at other hospitals. The diameter of the cyst was an independent risk factor for complications (P < 0.05). The data are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of factors associated with perioperative complication in all patients (n = 62)

| Variates |

Univariate analysis

|

Multivariate analysis

|

||||

|

OR

|

95%CI

|

P

|

OR

|

95%CI

|

P

value

|

|

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | Reference | |||||

| Female | 5.125 | 0.538-48.718 | 0.155 | |||

| Age, yr | ||||||

| ≤ 60 | Reference | |||||

| > 60 | 0.559 | 0.087-3.605 | 0.541 | |||

| BMI, kg/m2 | ||||||

| ≤ 23 | Reference | |||||

| > 23 | 1.700 | 0.621-4.657 | 0.302 | |||

| ASA | ||||||

| Class I | Reference | |||||

| Class II | 0.826 | 0.284-2.400 | 0.726 | |||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | ||||||

| No | Reference | |||||

| Yes | 3.954 | 0.306-51.098 | 0.292 | |||

| Hypertension | Reference | |||||

| No | ||||||

| Yes | 0.591 | 0.126-2.774 | 0.505 | |||

| Tumor diameter, cm | ||||||

| < 10 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| ≥ 10 | 3.339 | 1.122-9.938 | 0.030a | 3.286 | 1.020-10.587 | 0.046a |

| Tumor location | ||||||

| S3↑ | Reference | Reference | ||||

| S3↓ | 2.187 | 0.755-6.341 | 0.149 | 1.991 | 0.655-6.054 | 0.225 |

| Operation duration, min | ||||||

| < 121 min | Reference | |||||

| ≥ 121 min | 1.670 | 0.611-4.568 | 0.318 | |||

| Blood loss, ml | ||||||

| < 25 mL | Reference | |||||

| ≥ 25 mL | 1.923 | 0.699-5.285 | 0.205 | |||

| Previous abdominal surgery | ||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Yes | 0.750 | 0.274-2.051 | 0.575 | 0.667 | 0.227-1.963 | 0.462 |

| Previous treatment | ||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Yes | 1.389 | 0.350-5.505 | 0.640 | 0.938 | 0.208-4.226 | 0.933 |

P value < 0.05 indicates the statistical difference.

Surgical pathology and follow-up

Final surgical pathology reports showed that 20 patients had teratoma, of which 2 patients had mature teratoma with mucinous adenocarcinoma and one patient had mature teratoma with neuroendocrine carcinoma. There were 29 cases of epidermoid cysts, 11 cases of dermoid cysts, and 2 cases of tailgut cysts.

Sixty-one (98.4%) patients were followed up. Follow-up ranged from 10 to 103 mo, with a median follow-up of 58 months. During follow-up, a subcutaneous cyst was found in 1 patient 8 mo postoperatively, who underwent local excision of the cyst. In another patient, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at the 6-month follow-up showed recurrence of small presacral cysts. The cysts had not grown by March 2021, and the patient is still followed up. Recurrence was not observed in the remaining 59 patients.

DISCUSSION

Traditionally, low retrorectal cystic lesions are accessed via the posterior transsacral approach, which provides a good surgical view and facilitates en bloc excision[17,18]. However, the coccyx and part of the sacrum were removed when using this approach. This leads to more tissue damage and a higher rate of fluid accumulation and wound infection[19]. When the upper border of the cyst is high, dissection of the top can be difficult via the posterior approach, which can lead to incomplete excision and presacral bleeding[20]. Our center performed the first laparoscopic excision of retrorectal cystic lesions in 2012[21,22]. The surgical field can be better exposed through high-resolution cameras and flexible tools. Therefore, we can explore the area from the inlet of the true pelvis to the levator hiatus, which cannot be achieved using traditional laparotomy or the transsacral approach. In the 62 patients reported, there was no conversion from laparoscopy to an open approach. The traditional abdominal approach had a higher recurrence rate than the posterior approach because of the difficulty in exposing and dissecting deep sacrococcygeal lesions. Even with laparoscopy, a combined transsacral approach is sometimes needed for some massive lesions that penetrate the pelvic floor to the gluteal subcutaneous tissue. Under these circumstances, the laparoscopic approach is first used to dissect the lesion as much as possible, reaching beyond the pelvic floor. The patient was then switched to the prone jackknife position, and the lesion was resected en bloc via the transsacral approach. Of the 62 patients reported in this study, five underwent combined laparoscopic and transsacral surgery.

Retrorectal cystic lesions grow slowly in the pelvis, leading to silent onset. Most patients present with non-specific or non-specific clinical characteristics[23,24]. Some patients show symptoms suggestive of compression by large tumors, including lower back or sacrococcygeal pain, constipation, urinary frequency, and dysuria. Very large retrorectal cysts surround the posterior and lateral sides of the rectum. They can also penetrate the pelvic floor muscles, protrude into the gluteal subcutaneous tissue, and even ulcerate. Of the 62 patients included in this study, 33 (53.2%) were asymptomatic and diagnosed by routine health checkups. Two patients (3.2%) experienced recurrence after previous surgery at other hospitals. Twenty-seven (43.6%) patients presented with symptoms such as changes in bowel habits (14 cases), abdominal pain (6 cases), urinary frequency (2 cases), dysuria (1 case), and sacrococcygeal pain (4 cases).

Imaging examinations used for the assessment of retrorectal cystic lesions include B ultrasonography, enhanced computed tomography (CT), and pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)[25]. MRI has been reported to be the most accurate diagnostic tool, which can effectively detect solid components and assess the relationship between the lesion and surrounding structures[26,27]. In this study, 56 patients underwent pelvic MRI before excision, while 6 patients underwent both ultrasound and enhanced CT. The decision of the surgical approach was based on the location, size, possibility of malignancy, and relationship with the surrounding tissues. Retrorectal cystic lesions are often polycystic lesions with septa. Our review of patient imaging examinations showed that approximately two-thirds of the tumors were polycystic. We suggest that surgeons review imaging examinations carefully before the operation to facilitate thorough exploration and complete excision of all lesions.

We analyzed the differences between postoperative patients with lesions above and below the S3 Level[28]. General conditions such as age, BMI, and ASA class were similar between the groups, with no significant differences observed. Some patients were treated in other hospitals. Procedures such as needle biopsy and exploratory laparotomy can aggravate adhesion in the surgical area, adding to the difficulty and risk of the operation. However, there was no significant difference in previous treatment between the two groups. Additionally, no significant difference was observed in the size of the lesion between the groups (above-S3, 8.3 ± 3.5 cm; under-S3, 8.2 ± 2.8 cm; P > 0.05). Therefore, the baseline characteristics of the patients before surgery were similar. Blood loss, operation duration, and postoperative length of hospital stay were not significantly different between the groups. Perioperative complications ≥ CD grade II or ≥ CD grade IIIa also showed no significant difference. The readmission rate within 90 d of discharge was also similar between the groups. These results suggest that the location of the lesion relative to the S3 Level might not be a determinant of the proper surgical approach. For lesions under the S3 Level, laparoscopic surgery is feasible after a thorough review of the imaging examinations.

Based on our experience, we defined lesions with diameters ≥ 10 cm as massive lesions. The baseline characteristics of the massive- and smaller-lesion groups were not significantly different. As expected, the massive-lesion group showed significantly longer operation duration and larger blood loss. The massive-lesion group also had higher rates of complications ≥ CD grade II and ≥ CD grade IIIa (P < 0.05). For larger retrorectal lesions, there was a higher risk of perioperative complications such as damage to the rectum and rectal fistula, and we usually performed a temporary transverse colostomy for patients with rectal damage during surgery. The same procedure was also performed in patients who did not respond to conservative treatment. After recovery, the ostomy reversal procedure contributed to a longer length of hospital stay (P < 0.05).

Univariate and multivariate analyses showed that lesion diameter might be a risk factor for complications in laparoscopic excision of retrorectal lesions. Larger lesions tended to have a longer operation duration, larger blood loss, and a higher risk of severe complications. Larger cysts interfere with dissection into the deeper parts of the pelvis. Therefore, after dissecting as much as possible towards the pelvic floor, we sometimes puncture the cyst and aspirate the cyst fluid to create a space for the en bloc excision. With sufficient irrigation in the direct view of the laparoscope, such cyst decompression procedures will not increase the risk of complications, as Abe et al showed in their study[29].

This study has certain limitations. First, it was a retrospective study, and selection bias should be considered. Second, to evaluate the use of laparoscopy in lesions under the S3 Level, we compared laparoscopy and the combined use of laparoscopic and transsacral approaches. In future research, larger multi-center, prospective studies can be used to better evaluate the use of laparoscopy in retrorectal lesions at the S3 Level or larger than 10 cm in diameter.

CONCLUSION

This is the largest single-center report of laparoscopic excision of retrorectal cystic lesions, with a mean follow-up period of more than 4 years[12,16]. Comparison between the groups and univariate or multivariate analyses showed that the diameter of the lesion was an independent risk factor for perioperative complications. However, the location of the lesion is not necessarily a determinant of the surgical approach. Laparoscopic surgery is minimally invasive, high-resolution, and flexible, and its use in retrorectal cystic lesions is safe and feasible, also for lesions below the S3 Level. It can better expose the surgical area and play an important role in the treatment of retrorectal cystic lesions.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

The incidence of retrorectal lesions is low. Advantages of laparoscopic approach has been demonstrated in this field. Surgeons should minimize the incidence of perioperative complications.

Research motivation

Laparoscopic surgery of retrorectal cystic lesions have been widely used. The risk factors influencing perioperative complications of laparoscopic surgery should be discussed.

Research objectives

To investigate the risk factors for perioperative complications in laparoscopic surgeries of retrorectal cystic lesions.

Research methods

We retrospectively collected patient data as detailed as possible. Besides univariate analysis and multivariate analysis, patients were divided into groups based on the lesion location related to the 3rd sacral vertebra(S3) and diameter to investigate the possible risk factors.

Research results

Tumor diameter larger than 10 cm could be an independent risk factor. No significant differences in perioperative complications between the under-S3 group and the above-S3 group.

Research conclusions

Laparoscopic excision of retrorectal cystic lesions below the S3 Level is safe and feasible. Lesion diameter was an independent risk factor for the development of perioperative complications.

Research perspectives

Larger multi-center, prospective studies can be conducted to verify whether tumors larger than 10 cm in diameter could be the risk factor.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First of all, we sincerely thank the patient for his cooperation. Secondly, we thank the surgeons, physician, nurses, technical staff, and hospital administration of contributions to this study. Moreover, we thank Dr Wu for advice and support. Finally, the authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital.

Informed consent statement: The analysis used anonymous clinical data that were obtained after each patient agreed to treatment by written consent.

Conflict-of-interest statement: We have no financial relationships to disclose.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review started: July 19, 2021

First decision: September 5, 2021

Article in press: October 27, 2021

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Navarrete Arellano M, Ortmann O, Reiter M S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang LL

Contributor Information

Pei-Pei Wang, Department of General Surgery, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China.

Chen Lin, Department of General Surgery, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China.

Jiao-Lin Zhou, Department of General Surgery, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China.

Kai-Wen Xu, Department of General Surgery, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China.

Hui-Zhong Qiu, Department of General Surgery, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China.

Bin Wu, Department of General Surgery, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China. wubin@pumch.cn.

References

- 1.Whittaker LD, Pemberton JD. TUMORS VENTRAL TO THE SACRUM. Ann Surg. 1938;107:96–106. doi: 10.1097/00000658-193801000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hobson KG, Ghaemmaghami V, Roe JP, Goodnight JE, Khatri VP. Tumors of the retrorectal space. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1964–1974. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0122-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glasgow SC, Birnbaum EH, Lowney JK, Fleshman JW, Kodner IJ, Mutch DG, Lewin S, Mutch MG, Dietz DW. Retrorectal tumors: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1581–1587. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wohlmuth C, Bergh E, Bell C, Johnson A, Moise KJ, Jr , van Gemert MJC, van den Wijngaard J, Wohlmuth-Wieser I, Averiss I, Gardiner HM. Clinical Monitoring of Sacrococcygeal Teratoma. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2019;46:333–340. doi: 10.1159/000496841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chéreau N, Lefevre JH, Meurette G, Mourra N, Shields C, Parc Y, Tiret E. Surgical resection of retrorectal tumours in adults: long-term results in 47 patients. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:e476–e482. doi: 10.1111/codi.12255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dozois EJ, Jacofsky DJ, Billings BJ, Privitera A, Cima RR, Rose PS, Sim FH, Okuno SH, Haddock MG, Harmsen WS, Inwards CY, Larson DW. Surgical approach and oncologic outcomes following multidisciplinary management of retrorectal sarcomas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:983–988. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1445-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jao SW, Beart RW, Jr , Spencer RJ, Reiman HM, Ilstrup DM. Retrorectal tumors. Mayo Clinic experience, 1960-1979. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28:644–652. doi: 10.1007/BF02553440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patsouras D, Pawa N, Osmani H, Phillips RK. Management of tailgut cysts in a tertiary referral centre: a 10-year experience. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17:724–729. doi: 10.1111/codi.12919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baek SK, Hwang GS, Vinci A, Jafari MD, Jafari F, Moghadamyeghaneh Z, Pigazzi A. Retrorectal Tumors: A Comprehensive Literature Review. World J Surg. 2016;40:2001–2015. doi: 10.1007/s00268-016-3501-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharpe LA, Van Oppen DJ. Laparoscopic removal of a benign pelvic retroperitoneal dermoid cyst. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1995;2:223–226. doi: 10.1016/s1074-3804(05)80023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kondo T. Retrorectal tumour. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:e654. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30370-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mullaney TG, Lightner AL, Johnston M, Kelley SR, Larson DW, Dozois EJ. A systematic review of minimally invasive surgery for retrorectal tumors. Tech Coloproctol. 2018;22:255–263. doi: 10.1007/s10151-018-1781-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Messick CA. Presacral (Retrorectal) Tumors: Optimizing the Management Strategy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61:151–153. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kilic A, Basak F, Su Dur MS, Sisik A, Kivanc AE. A clinical and surgical challenge: Retrorectal tumors. J Cancer Res Ther. 2019;15:132–137. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.183192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carpelan-Holmström M, Koskenvuo L, Haapamäki C, Renkonen-Sinisalo L, Lepistö A. Clinical management of 52 consecutive retro-rectal tumours treated at a tertiary referral centre. Colorectal Dis. 2020;22:1279–1285. doi: 10.1111/codi.15080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yalav O, Topal U, Eray İC, Deveci MA, Gencel E, Rencuzogullari A. Retrorectal tumor: a single-center 10-years' experience. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2020;99:110–117. doi: 10.4174/astr.2020.99.2.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmed F, Fogel E. Reply to Reiss G, Ramrakhiani S. Right upper-quadrant pain and a normal abdominal ultrasound. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;7:603. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1256. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanemitsu T, Kojima T, Yamamoto S, Koike A, Takeshige K, Naruse T. The trans-sphincteric and trans-sacral approaches for the surgical excision of rectal and presacral lesions. Surg Today. 1993;23:860–866. doi: 10.1007/BF00311362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghosh J, Eglinton T, Frizelle FA, Watson AJ. Presacral tumours in adults. Surgeon. 2007;5:31–38. doi: 10.1016/s1479-666x(07)80109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Böhm B, Milsom JW, Fazio VW, Lavery IC, Church JM, Oakley JR. Our approach to the management of congenital presacral tumors in adults. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1993;8:134–138. doi: 10.1007/BF00341185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou JL, Wu B, Xiao Y, Lin GL, Wang WZ, Zhang GN, Qiu HZ. A laparoscopic approach to benign retrorectal tumors. Tech Coloproctol. 2014;18:825–833. doi: 10.1007/s10151-014-1146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou J, Zhao B, Qiu H, Xiao Y, Lin G, Xue H, Niu B, Sun X, Lu J, Xu L, Zhang G, Wu B. Laparoscopic resection of large retrorectal developmental cysts in adults: Single-centre experiences of 20 cases. J Minim Access Surg. 2018 doi: 10.4103/jmas.JMAS_214_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oguz A, Böyük A, Turkoglu A, Goya C, Alabalık U, Teke F, Budak H, Gumuş M. Retrorectal Tumors in Adults: A 10-Year Retrospective Study. Int Surg. 2015;100:1177–1184. doi: 10.9738/INTSURG-D-15-00068.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neale JA. Retrorectal tumors. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2011;24:149–160. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1285999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Macafee DA, Sagar PM, El-Khoury T, Hyland R. Retrorectal tumours: optimization of surgical approach and outcome. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:1411–1417. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.02994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu KJ, Lee PJ, Austin KKS, Solomon MJ. Tumors of the Ischiorectal Fossa: A Single-Institution Experience. Dis Colon Rectum. 2019;62:196–202. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sagar AJ, Koshy A, Hyland R, Rotimi O, Sagar PM. Preoperative assessment of retrorectal tumours. Br J Surg. 2014;101:573–577. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woodfield JC, Chalmers AG, Phillips N, Sagar PM. Algorithms for the surgical management of retrorectal tumours. Br J Surg. 2008;95:214–221. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abel ME, Nelson R, Prasad ML, Pearl RK, Orsay CP, Abcarian H. Parasacrococcygeal approach for the resection of retrorectal developmental cysts. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28:855–858. doi: 10.1007/BF02555492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]