Abstract

How chromatin-mediated transcription regulates the beginning of mammalian development is currently unknown. Factors responsible for promoter repression and enhancer-mediated relief of this repression are not present in the paternal pronuclei of one-cell mouse embryos but are present in the zygotic nuclei of two-cell embryos. Here we show that coinjection of purified histones and a plasmid-encoded reporter gene into the paternal pronuclei of one-cell embryos at a specific histone-DNA concentration could recreate the behavior observed in two-cell embryos: acquisition of promoter repression and subsequent relief of this repression either by functional enhancers or by histone deacetylase inhibitors. Furthermore, the extent of enhancer-mediated stimulation in one-cell embryos depended on the acetylation status of the injected histones, on the treatment of embryos with a histone deacetylase inhibitor, and on the developmentally regulated appearance of enhancer-specific coactivator activity. The coinjected plasmids in one-cell embryos also exhibited chromatin assembly, as determined by a supercoiling assay. Thus, injection of histones into one-cell embryos faithfully reproduced the chromatin-mediated transcription observed in two-cell embryos. These results suggest that the need for enhancers to stimulate promoters through relief of chromatin-mediated repression occurs once the parental genomes are organized into chromatin. Furthermore, we present a model mammalian system in which the role of individual histones, and particular domains within the histones that are targeted in enhancer function, can be examined using purified mutant histones.

Transcription by RNA polymerase II is thought to be controlled primarily by two DNA elements: promoters and enhancers. Promoters, which constitute short-distance interactions, determine where transcription begins. They consist of a binding site for the basal-level transcription complex and often one or more sequence-specific transcription factor binding sites, upstream and close to the initiation site. Enhancers, which constitute long-distance interactions, stimulate weak promoters in a tissue-specific manner. Enhancers consist of transcription factor binding sites that function distal to the initiation site from either an upstream or a downstream position (28, 37). Our current knowledge of the principles that regulate mammalian transcription, including the function of enhancers, comes mainly from studies involving either cell-free in vitro systems or in vivo systems consisting of cultured cells or cultured cells infected with animal viruses. Enhancers are not active in in vitro systems unless the template DNA is reconstituted into chromatin. How transcriptional regulation controls complex physiological processes such as the development of the fertilized egg into an animal is largely unknown, in part because there are few in vivo model systems. The Xenopus system, which can be used to study early vertebrate development, does not accurately reflect mammalian development in all aspects (14, 28, 37). Recent advances in microinjection technologies have allow transcription and replication to be studied in mammalian embryos at as early as the one-cell embryo stage and provide an unprecedented opportunity to study these regulatory processes in a living system (16, 17, 28, 41, 42).

In mammals, fertilization of an egg by a sperm produces a one-cell embryo containing paternal and maternal haploid pronuclei. Each pronucleus then undergoes DNA replication before entering the first mitosis to generate a two-cell embryo containing one diploid zygotic nucleus per cell, each with a set of maternal chromosomes and a set of paternal chromosomes. Maternally inherited mRNAs are translated continuously in mature eggs and in one-cell embryos (12), but most expression of zygotic genes (zygotic gene activation [ZGA]) begins by a time-dependent mechanism (zygotic clock) at about 32 h postfertilization (hpf), when the embryo is at the two-cell stage of normal development (16, 17, 28, 41, 42). However, if inhibitors of DNA replication are used to arrest one-cell embryos in S phase, those embryos remain morphologically one-cell embryo, but ZGA still begins at 32 hpf, as in normal developing two-cell embryos (10, 33, 51). Furthermore, ZGA also begins at 32 hpf in S phase-arrested two-cell embryos. The discovery of the zygotic clock was crucial in allowing the requirements for transcription and DNA replication in arrested-mouse one-cell embryos to be compared with those in arrested two-cell embryos. To perform such comparisons, one can inject plasmid DNA into the pronuclei or nuclei of these embryos and analyze the injected plasmid DNA's activity at 32 hpf (16, 28, 35). The injected plasmid DNA can replicate or express an encoded reporter gene only when specific cis-acting regulatory sequences and their cognate transacting proteins are present and only when the embryo's genome executes the same function during its normal developmental program. Thus, this is a useful system for studying the embryo's capacity for DNA replication and gene expression and its requirements for specific regulatory elements (27, 28).

Preliminary studies using microinjected plasmid DNA revealed that the components of enhancer function that are required in all cultured cells and cell extracts are actually acquired sequentially during mouse embryonic development. (i) Enhancer function, which first appears at the two-cell stage in mouse development and coincides with ZGA, relieves repression of promoters (4, 30, 32, 33, 51, 52, 55). (ii) Enhancers stimulate promoters by a TATA-box-independent mechanism in undifferentiated embryonic cell types and later change to a TATA-box-dependent mode as cell differentiation becomes evident (11, 29). (iii) Enhancers appear to require a coactivator activity for optimal function. The coactivator activity is not available until zygotic gene expression begins at the two-cell stage (23, 31).

Here we used an improved experimental protocol of microinjecting a plasmid containing a promoter-enhancer sequence driving a luciferase reporter gene into the paternal pronuclei of one-cell embryos and the zygotic nuclei of two-cell embryos and then assayed reporter gene activity. These experiments confirmed our previous observations that promoter repression and enhancer-mediated promoter stimulation do not occur in paternal pronuclei but do occur in zygotic nuclei. We then showed that coinjection of purified histones along with the plasmid DNA at a specific histone-DNA concentration could reconstitute repression of the plasmid-encoded promoter and subsequent relief of this repression by functional enhancers in the paternal pronuclei of one-cell embryos. The reconstituted enhancer function responded to the acetylation status of the injected histones and to the treatment of embryos with histone deacetylase inhibitors. The reconstituted enhancer function also depended on the expression of enhancer-specific coactivator activity and showed properties of chromatin assembly, as determined by superhelicity assays. These results also suggest that enhancer function during mouse development occurs when the parental genomes are organized into chromatin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse embryos.

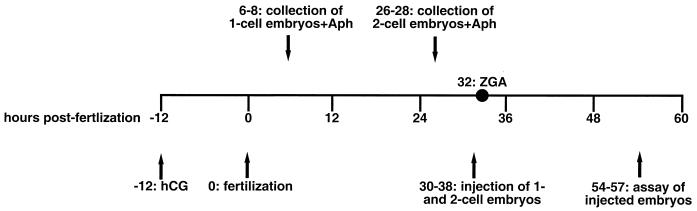

CD-1 mouse embryos were isolated and cultured as described elsewhere (16, 27, 35). Briefly, as shown in Fig. 1, superovulation was induced in 8- to 10-week-old female mice by intraperitoneal injection of 10 U (0.1 ml of a 100-U/ml stock solution) of pregnant mares' serum (Sigma), and then, 48 h later, 10 U (0.1 ml of a 100-u/ml stock solution) of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG; Sigma), which triggers ovulation 11 to 13 h later. Each injected female was mated with a single male more than 10 weeks old. Fertilization takes place at about 12 h post-hCG (0 hpf). One-cell embryos were isolated at 6 to 8 hpf and cultured in the presence of 4 μg of aphidicolin (Boehringer-Mannheim) per ml to arrest development at the beginning of S phase. Two-cell embryos were isolated at 26 to 28 hpf, when they had completed S phase, and were cultured in the presence of aphidicolin. Because the first S phase had not yet begun when the one-cell embryos were isolated, aphidicolin caused them to retain their two pronuclei (male and female) throughout the experiment. Because the two-cell embryos were isolated after they had undergone DNA replication, aphidicolin caused them to arrest at the four-cell stage. Without aphidicolin, injected one-cell and two-cell embryos developed up to the morula stage.

FIG. 1.

Timetable for injection and assay of mouse embryos. See Materials and Methods for details.

Injection of plasmid DNA and reporter gene assay.

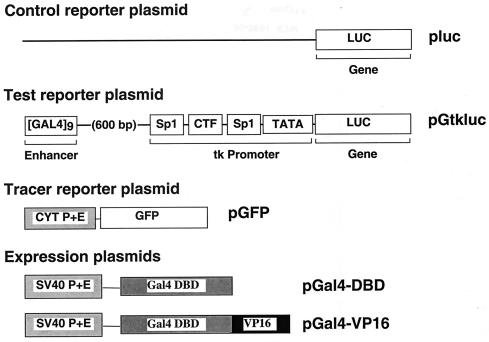

Injection and assay of reporter gene expression were performed by a modification of a protocol described elsewhere (27), according to the timetable shown in Fig. 1. We used five plasmids (pluc, pGtkluc, pGal4-VP16, pGal4-DBD, and pGFP) in this study. They are schematically shown in Fig. 2. The control plasmid pluc contains the luciferase reporter gene with no promoter or enhancer sequences. The reporter plasmid pGtkluc contains a tandem series of nine yeast GAL4 DNA-binding sites (Gal4 enhancer), placed 600 bp upstream of the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (tk) promoter, which drives expression of the luciferase gene (27, 35). The tk promoter is functional in both mouse embryos and differentiated cells (29, 30). In mouse embryos, luciferase is a very sensitive reporter gene with a short half-life; thus, its expression reflects steady-state concentration of the protein (27, 35). The luciferase activity produced in embryos from this plasmid correlates directly with the presence of the promoter-enhancer sequences encoded by the plasmid (23, 30, 31). The expression vectors pGal4-VP16 and pGal4-DBD encode the complete Gal4-VP16 protein and the Gal4 DNA-binding domain, respectively. These genes are under the control of simian virus 40 promoter-enhancer elements and are expressed in mouse embryos (23, 30, 31). Thus, coinjection of pGtkluc with pGal4-VP16 will activate the Gal4 enhancer. In contrast, pGtkluc alone or coinjection of pGtkluc with pGal4-DBD will not activate the Gal4 enhancer. The tracer plasmid pGFP encodes the green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter gene under the control of human cytomegalovirus immediate early promoter-enhancer elements and is also expressed in mouse embryos (31).

FIG. 2.

A schematic representation of the plasmids used in the study. See Materials and Methods for details.

Plasmid DNA was suspended in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6) containing 0.25 mM EDTA (27). About 2 pl of plasmid DNA solution containing a total of 0.0765 μg of plasmid DNA (0.05 μg of pGtkluc per μl; 0.025 μg of pGal4-VP16, pGal4-DBD, or pBR322 vector DNA per μl; 0.015 μg pGFP per μl, per μl with or without histones (see below) was injected into the paternal pronuclei of aphidicolin-arrested one-cell embryos or the zygotic nuclei of aphidicolin-arrested two-cell embryos between 30 and 38 hpf (Fig. 1). About 30 to 60 embryos were injected. Embryos that survived injection (∼80%) were cultured and then monitored for expression of GFP at 54 hpf. Both aphidicolin-arrested one-cell and two-cell embryos show ZGA at 32 hpf (27, 28). Between 20 and 50 GFP-positive embryos were individually assayed for luciferase activity at 54 to 57 hpf as described previously (23, 27). Briefly, each embryo was transfered into an Eppendorf tube containing 50 μl of luciferase reaction mix (LRM; 25 mM glycylglycine) [pH 7.8], 10 mM magnesium acetate, 0.5 mM ATP [pH 7], 100 mg of bovine serum albumin per ml, 1 mM dithiothreitol; LRM can be stored at 4°C for a month) containing freshly added 0.1% Triton X-100 and then frozen in a dry ice-ethanol bath. Frozen embryos can be stored at −70°C until assayed. Frozen samples were thawed at 37°C and centrifuged in an Eppendorf centrifuge at 10,000 rpm for 1 min to collect the embryo extract at the bottom of the tube. The embryo extract was mixed with 300 μl of LRM in a polystyrene cuvette, and the luciferase activity was measured using a Monolight 2010 luminometer (Analytical Luminiscence) that dispenses 100 μl of 1 mM luciferin solution in water (Analytical Luminiscence; stock solution can be stored at 4°C for a month) plus 1 mg of coenzyme A (grade II; Boehringer Mannheim; a stock solution of 100 mg/ml can be stored at −70°C for months) per ml and integrates the emitted light over a period of 10 s. For each datum point in the graph, the mean value of all the embryos was used, and the variation among individual embryos was expressed as the standard error of the mean. While the range of luciferase activities in individual embryos varied by as much as 1,000-fold, the mean values obtained from several independent experiments varied by 13 to 25% (data not shown). Moreover, the relative activities of different batches of embryos and different promoters were always similar, even when DNA injection was performed by different people. Each set of experiments was repeated two to three times.

Histones.

Individual, electrophoretically homogeneous, calf-thymus histones (Roche Diagnostics Corporation) were resuspended in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 1 mg/ml, aliquoted, and frozen at −80°C. The histone core stock was made fresh each time as a 1:1:1:1 mix of histones H2A, H2B, H3, and H4. Histone H1 was added at one-eighth the concentration of all core histones when indicated. Various dilutions of the stock were added to the plasmid DNA before injection. Nonacetylated and acetylated histones were purified from a 3-liter culture of HeLa cells (NIH Cell Culture Center) that had been grown to 7.6 × 105 cells/ml in minimal essential medium with 5% serum with or without the addition of 8 mM butyric acid 24 h before harvesting. The cells were harvested by centrifugation for 10 min at 2,500 × g, followed by two 5-min washes with PBS, with or without 8 mM butyric acid, to produce a 5-g cell pellet. The histones were then isolated as described previously (44).

Supercoiling assay.

Between 100 and 200 embryos injected with 0.076 μg of pGtkluc (plus 0.04 μg of histones per μl where indicated) per μl were flash-frozen in a siliconized tube containing 50 μl of 10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 0.1% Triton X-100, and 5 μg of yeast tRNA. The mixture was then thawed and deproteinized by digestion with proteinase K plus 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate at 56°C for 30 min. The DNA was then extracted with phenol-chloroform and precipitated with alcohol. The resulting pellet was resuspended in 15 μl of 10 mM Tris and 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) and assayed for superhelicity as described elsewhere (33) by electrophoresis of the extracted DNA in a 0.7% agarose gel and transfer onto Hybond+ (Amersham) membranes, which were then hybridized with a labeled plasmid DNA probe and analyzed by autoradiography. Each experiment was performed twice, and a representative result is shown.

RESULTS

Enhancer-dependent stimulation of promoter activity in two-cell but not in one-cell embryos.

To compare the transcriptional activity in the paternal pronuclei of S-phase-arrested one-cell embryos with that of the zygotic nuclei of S-phase-arrested two-cell embryos, we injected them with pGtkluc plus pGFP and vector DNA (pBR322), pGal4-VP16, or pGal4-DBD and assayed for luciferase activity. To measure the background level of luciferase activity in these embryos, we replaced pGtkluc by pluc. The experimental protocol described here is similar to ones we reported previously (23, 30, 31) but has three advantages. First, it permits the total amount of DNA in each injection to be kept constant by injecting the mutant form of pGal4-VP16 (pGal4-DBD), which was not used before. Second, pGFP was used as a tracer to identify embryos that were successfully injected and were biologically active. In previous experiments there was no such tracer reporter gene that could detect whether the embryos were actually injected with the plasmid DNA or whether the embryos were active. This reduced the level of error in the present experiment. Third, in previous experiments one-cell embryos were injected with plasmid DNA 4 to 8 hpf and reporter gene expression was assayed at 52 hpf and two-cell embryos were injected between 36 and 40 hpf and assayed at 84 hpf. Thus, although the microinjected plasmids were present inside one-and two-cell embryos for a total of 48 h, the exact time they were inside these embryos after fertilization was different. Thus, it was possible that any difference observed in the expression of genes from the injected plasmids between one- and two-cell embryos was due to this temporal difference and not due to the stage of the embryo. To distinguish between these possibilities, both one-cell and two-cell embryos in the present study were injected 30 to 38 hpf and assayed at 54 to 57 hpf.

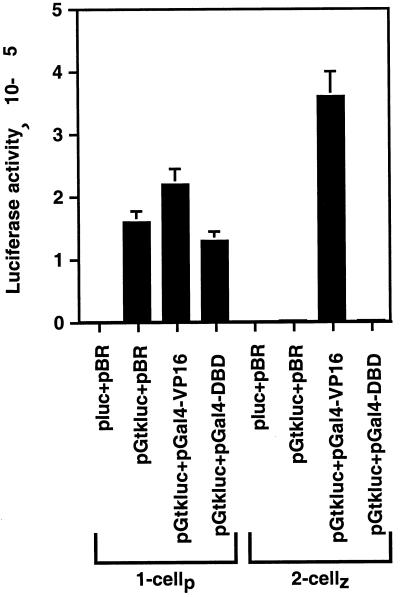

As shown in Fig. 3, microinjection of pluc plus the vector DNA, pBR322, alone produced very little luciferase, confirming that these embryos did not produce endogenous luciferase. The tk promoter activity in the absence of the enhancer function (pGtkluc plus pBR322) was very high in the paternal pronuclei of one-cell embryos but was strongly repressed in the zygotic nuclei of two-cell embryos. Activation of enhancer function by coinjection of pGal4-VP16 did not substantially change luciferase activity in one-cell embryos but stimulated promoter activity 140-fold in two-cell embryos. Expression of Gal4-VP16 in these embryos resulted in a twofold nonspecific stimulation of luciferase activity, as previously reported (30). Thus, promoter repression in two-cell embryos could be relieved by the Gal4 enhancer. Coinjection of pGtkluc with pGal4-DBD, which does not contain an activation domain and therefore cannot activate the Gal4 enhancer, did not affect the high promoter activity in one-cell embryos or the repressed promoter activity in two-cell embryos. These results indicate that even when the plasmid DNA was injected into one- and two-cell embryos at the same time after fertilization and assayed for luciferase activity also at the same time after fertilization, the tk promoter activity was high in one-cell embryos and was repressed in two-cell embryos. The presence of the Gal4 enhancer did not substantially alter the promoter activity in one-cell embryos, but in two-cell embryos the enhancer relieved the promoter repression and stimulated expression to a level similar to that in one-cell embryos.

FIG. 3.

Transcriptional enhancer function was not present in the paternal pronuclei of S phase-arrested one-cell mouse embryos (1-cellp) but was present in the zygotic nuclei of S-phase-arrested two-cell embryos (2-cellz). Embryos were isolated and injected with the plasmids indicated at a total concentration of 0.0765 μg/μl, and luciferase reporter gene expression was assayed (see Materials and Methods). pBR, pBR322.

Promoter repression and subsequent relief of repression by enhancers in paternal pronuclei of one-cell embryos after coinjection of purified histones.

Previous experiments with the histone deacetylase inhibitors sodium butyrate and trichostatin showed that they cannot stimulate promoters in one-cell embryos but do in two-cell embryos, suggesting that the lack of promoter repression and subsequent enhancer function in one-cell embryos is due to the absence of chromatin-mediated repression (1, 2, 17, 19, 31, 45, 51, 52, 54). As stated above, in addition to chromatin-mediated repression, enhancer function also requires the presence of an enhancer-specific coactivator activity that appears during mouse embryonic development at ZGA at about 32 hpf (23, 31). To discern the role of chromatin in enhancer function, we coinjected plasmid DNA and purified histones from calf thymus into the paternal pronuclei of one-cell mouse embryos at 30 to 38 hpf and assayed reporter gene activity at 54 to 57 hpf, when the enhancer-specific coactivator activity should be produced in these embryos. We did not assay embryos beyond this time point because, in aphidicolin-arrested one-cell embryos, protein translation then decreases drastically (27, 52).

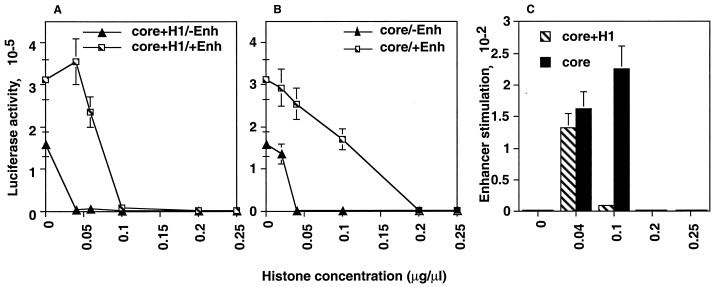

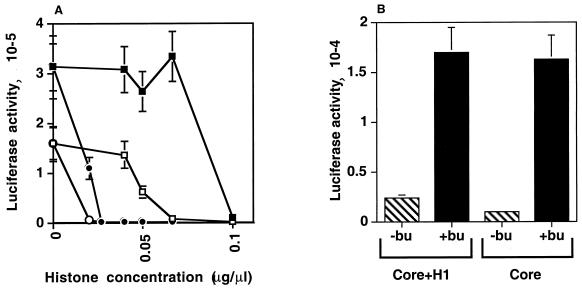

The tk promoter activity was found to depend on the histone concentration (Fig. 4). At lower concentrations of core histones plus histone H1 (<0.1 μg/μl), promoter activity was repressed in the absence of enhancer function (−Enh), but this repression was relieved by the presence of enhancer function (+Enh). Higher concentrations of histones (>0.1 μg/μl) repressed luciferase activity in both the −Enh and +Enh conditions, indicating that the higher concentrations inhibited transcription nonspecifically and that this inhibition could not be relieved by enhancers. Similar results were seen when pGtkluc was coinjected with core histones (Fig. 4), except that the enhancer function could relieve promoter repression at higher concentrations of histones (up to 0.2 μg/μl). At 0.04 μg/μl, the core histones, with or without H1, repressed promoter activity by ca. 100-fold in the absence of the enhancer function; however, this repression could be relieved and promoter activity stimulated to ca. 200-fold by the enhancer function. Thus, the appearance of promoter repression followed by enhancer-mediated relief of this repression after injection of specific concentrations of histones into the paternal pronuclei indicated that promoter repression was not simply due to the formation of nonspecific insoluble histone-DNA complexes but rather due to the reconstitution of enhancer function.

FIG. 4.

Injection of core histones with or without H1 into paternal pronuclei of S-phase-arrested one-cell embryos repressed promoter activity from coinjected plasmids, and this repression was relieved by enhancers. Plasmid DNA solution (0.0765 μg/μl) containing pGtkluc plus pGFP and either pGal4-DBD (−Enh) or pGal4-VP16 (+Enh) was coinjected with purified core histones plus histone H1 (core+H1; A and C) or core histones alone (core; B and C) at the indicated concentrations into the paternal pronuclei of S-phase-arrested one-cell embryos and assayed for luciferase activity according to the timetable shown in Fig. 1. Histones were of calf thymus origin (see Materials and Methods).

As shown in Fig. 4C, optimal enhancer-mediated stimulation was observed at 0.04 to 0.1 μg of core histones per μl and at 0.04 μg of core histones plus H1 per μl. As we coinjected 76.5 μg of total plasmid DNA per μl, the effective concentration of histones in our system was within the normal range of equimolar concentrations of histones and DNA necessary to form physiologically active chromatin. We chose to use 0.04 μg of histones per μl for further experiments for two reasons. First, this was the concentration at which both core histones and core histones plus H1 were effective. By using this concentration, the results of future experiments with or without H1 can be compared with our results. Second, since 0.04 μg/μl was the lowest effective concentration, we expected it to produce fewer nonspecific effects inside the embryo.

Enhancer-mediated relief of promoter repression into paternal pronuclei depends on acetylation status of injected histones.

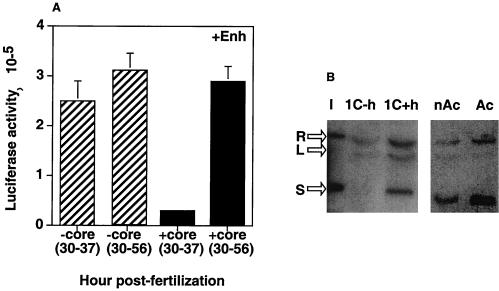

Acetylation of histones modulates chromatin structure, stimulates promoter activity, and regulates gene expression (18, 22, 26, 38, 53, 56). To determine whether the acetylation status of histones has an effect in our assay system, we performed two sets of experiments. In the first experiment we examined the effect of coinjecting the plasmids with HeLa-nonacetylated and HeLa-acetylated histones. We found that to achieve same degree of promoter repression in the absence of enhancer function required more than three times more acetylated histones than nonacetylated histones (Fig. 5A; 0.066 μg of acetylated histones per μl versus 0.02 μg of nonacetylated histones per μl). Thus, chromatin repression and subsequent enhancer stimulation in the paternal pronuclei depended on the acetylation status of the histones, as has been observed in other systems (18, 22, 26, 38, 53, 56).

FIG. 5.

(A) Acetylation status of histones injected into the paternal pronuclei of one-cell embryos determined the degree of promoter repression and relief of this repression by enhancers. Plasmid DNA solution (0.0765 μg/μl) containing pGtkluc plus pGFP and either pGa14-DBD (−Enh) or pGal4-VP16 (+Enh) was coinjected along with different concentrations of HeLa-nonacetylated core histones (○, −Enh; ●, +Enh) or HeLa-acetylated core histones (□, −Enh; ■, +Enh), and the luciferase activity was assayed. (B) Promoter repression of injected plasmids in the paternal pronuclei of one-cell embryos caused by coinjection of core histones, with or without H1, could be relieved by butyrate. Embryos injected with pGtkluc plus pGFP at a concentration of 0.0765 μg/μl and core histones plus H1 (Core+H1) or core histones alone (Core) at a concentration of 0.04 μg/μl were cultured with (+bu) or without butyrate (−bu) and assayed for luciferase activity.

Interestingly, the optimum concentration of HeLa-nonacetylated histones that was needed to obtain enhancer-mediated promoter stimulation (Fig. 5A) was different from the optimum concentration of calf thymus-histones needed to obtain similar effects (Fig. 4). This suggests that, although the pattern of reconstitution of enhancer function in paternal pronuclei by introduction of exogenous histones obtained from diverse sources remains similar, the histone source might influence the actual concentration that is required to obtain optimum enhancer function.

In the second set of experiments, we first injected histones into the male pronuclei of one-cell embryos and then treated the injected embryos with sodium butyrate. The promoter repression generated by either core histones or core histones plus H1 in one-cell embryos was relieved by butyrate to a similar degree (Fig. 5B), suggesting that promoter repression under these conditions is like that in two-cell embryos due to formation of chromatin (1, 2, 17, 19, 31, 45, 51, 52, 54). Thus, these two sets of complementary experiments support the idea that the acetylation status of injected histones in one-cell embryos determines the degree of promoter repression and relief of this repression by enhancers.

Enhancer-mediated relief of promoter repression into paternal pronuclei depends on the availability of enhancer-specific coactivator.

Previously, we observed that the enhancer function requires coactivator activity, which appears in mouse embryos at 30 hpf, and this activity increases with time (23, 31). To determine whether the enhancer function observed in one-cell embryos in the presence of core histones also depends on the coactivator activity, we injected enhancer constructs (+Enh) with or without core histones into the paternal pronuclei of one-cell embryos at about 30 hpf, close to the time when ZGA begins (32 hpf), and assayed for luciferase activity at 37 and 56 hpf. In the absence of histones, when there was no promoter repression, the promoter activity was similar at both times (Fig. 6A). This result is consistent with the observation that tk promoter-driven luciferase expression from injected plasmids in arrested one-cell embryos peaks by about 3 h after ZGA (33). However, in the presence of core histones, which cause promoter repression, the repression was not relieved when the embryos were assayed at 37 hpf but was relieved at 56 hpf. This suggested that the enhancer function observed in our embryo system required developmentally regulated coactivator activity (23).

FIG. 6.

(A) Enhancer-mediated relief of promoter repression depended on the availability of enhancer-specific coactivator activity. pGtkluc plus pGal4-VP16 and pGFP at a total concentration of 0.0765 μg/μl were injected with (+core) or without (−core) 0.04 μg of core histones per μl at 30 hpf and assayed for luciferase activity at 37 and 56 hpf. (B) Injection of core histones into the paternal pronuclei of one-cell embryos caused chromatin assembly on coinjected plasmid DNA. pGtkluc (0.0765 μg/μl) was injected into the paternal pronuclei of one-cell embryos in the absence (1C−h) or presence (1C+h) of 0.04 μg of core histones per μl, and the injected DNA was isolated and assayed for superhelicity. Supercoiled (S), relaxed (R), and linear (L) forms of the plasmid DNA are indicated. Input uninjected pGtkluc DNA (I) was used as a control. pGtkluc injected into one-cell embryos with nonacetylated (nAc) and acetylated (Ac) histones was also assayed for superhelicity.

Chromatin assembly on coinjected plasmids after injection of purified histones into paternal pronuclei.

Introduction of negative supercoiling into plasmid DNA has been used by several laboratories as an assay to examine chromatin assembly (3, 33, 49). Using this assay, plasmid DNA injected into the zygotic nuclei of two-cell embryos was mainly supercoiled, whereas that injected into paternal pronuclei was linear (33). To determine whether the injection of histones into paternal pronuclei of one-cell embryos actually causes chromatin assembly on coinjected plasmid DNA, we analyzed the superhelicity of the plasmid DNA in the embryos with or without coinjection of the core histones. As shown in Fig. 6B, the uninjected control input plasmid DNA (I) contained both relaxed and supercoiled forms. When the plasmid DNA alone was injected into the paternal pronuclei of one-cell embryos (1C−h), no superhelicity was observed. In contrast, in the presence of core histones (1C+h), the plasmid DNA exhibited superhelicity similar to that previously observed when plasmid DNA alone was injected into two-cell embryos, in which chromatin repression was observed (33). Thus, the introduction of exogenous core histones was responsible for the formation of chromatin assembly on the plasmid DNA injected into the paternal pronuclei of one-cell embryos. Interestingly, plasmid DNA injected with histones was consistently found to produce stronger signal than when injected without histones, suggesting that addition of the exogenous histones also might protect the injected DNA from degradation during the experimental procedure.

As described above, approximately three times more acetylated histones than nonacetylated histones were required to produce the same amount of promoter repression from injected plasmids into the paternal pronuclei. To determine whether acetylated histones were less efficient than nonacetylated histones in inducing chromatin assembly, plasmid DNA injected into paternal pronuclei with acetylated or nonacetylated histones was subjected to a superhelicity assay. As shown in Fig. 6B, acetylated and nonacetylated histones produced similar levels of supercoiled DNA (77 and 81%, respectively). This suggests that the transcriptional stimulation seen in the presence of acetylated histones is not due to inefficient chromatin assembly but is more likely due to the accessibility of the chromatin to transcription factors, as has been reported for other systems (20).

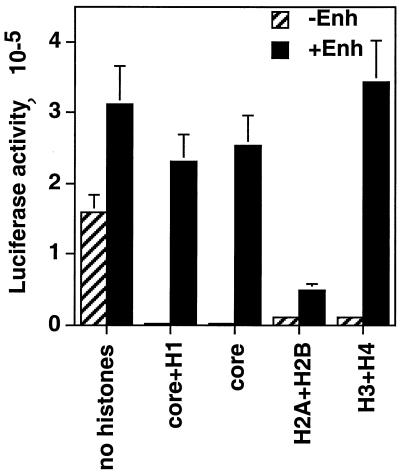

Reconstitution of enhancer function into the paternal pronuclei by injection of H3 and H4 but not H2A and H2B.

In vivo, the nucleosome assembly takes place sequentially, first by deposition of histones H3 and H4 on the DNA, followed by deposition of H2A and H2B (20). Furthermore, it has been shown that nucleosome structure can be induced in vitro by H3 and H4 but not by H2A and H2B (44). To determine whether our reconstituted enhancer function followed these principles, plasmid DNA was coinjected with purified H3 and H4 (1:1) or H2A and H2B (1:1), and the enhancer function was assayed. Plasmid DNA alone was also used as a control. Plasmid DNA without enhancer produced high promoter activity that was repressed by either core histones or core histones plus H1 (Fig. 7). Histones H2A plus H2B or H3 plus H4 also produced promoter repression (ca. 15-fold). Their combined repression was similar in magnitude to the repression produced by all core histones together or by core histones plus H1 (150-fold). However, enhancer function relieved H2A plus H2B repression only slightly (4.5-fold) but relieved H3 plus H4 repression 38-fold. Thus, enhancer function can be reconstituted by H3 plus H4 but not H2A plus H2B. This would be expected if enhancers in this system alleviate repression caused by nucleosomes formed as a result of binding of H3 plus H4 but not by DNA bound abnormally and nonspecifically by H2A plus H2B. Thus, these results suggest that coinjected histones form functional chromatin on the plasmid DNA.

FIG. 7.

Enhancer function could be reconstituted in the paternal pronuclei by injection of H3 plus H4 but not H2A plus H2B. pGtkluc plus pGFP and either pGal4-VP16 (+Enh) or pGal4-DBD (−Enh) at a final concentration of 0.0765 μg/μl were injected in the paternal pronuclei of one-cell embryos by themselves (no histones), with core histones plus H1 (core+H1), with core histones alone (core), with histones H2A and H2B (H2A+H2B), or with histones H3 and H4 (H3+H4). The final concentration of all histones was kept at 0.04 μg/μl. Promoter activity was determined as described in Materials and Methods.

DISCUSSION

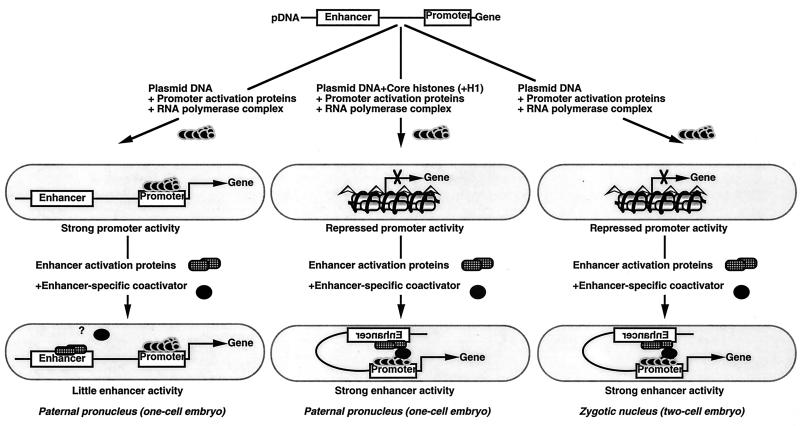

The paternal pronuclei of arrested mouse one-cell embryos do not show chromatin-mediated promoter repression and subsequent relief of this repression by enhancers. In contrast, such properties are observed in the zygotic nuclei of arrested mouse two-cell embryos. Here we showed that microinjection of a specific amount of purified histones into one-cell embryos recreated promoter repression and, most importantly, relief of this repression by enhancers and histone deacetylase inhibitors. Our results suggest that injected histones form physiologically active chromatin, since histones bound abnormally and nonspecifically to DNA would not have exhibited these properties. That the chromatin was biologically active was further supported by the fact that plasmid DNA coinjected with histones into the paternal pronuclei formed chromatin, as determined by the superhelicity assay, whereas plasmid DNA alone did not. Furthermore, the promoter-enhancer activity depended on the acetylation status of the injected histones and on the developmentally regulated appearance of enhancer-specific coactivator activity. Thus, these findings indicate that injection of purified histones into paternal pronuclei can reconstitute enhancer function expressed from coinjected plasmid DNA (Fig. 8).

FIG. 8.

Model for reconstitution of promoter repression by addition of purified histones and enhancer-mediated relief of this repression in paternal pronuclei of one-cell mouse embryos. Enhancer activity requires chromatin-mediated promoter repression, enhancer activation proteins, and enhancer-specific coactivator activity. Chromatin-mediated promoter repression is present in the zygotic nuclei of two-cell embryos but not in the paternal pronuclei of one-cell embryos. Because promoters are not repressed in the latter cell type, enhancers have no effect under these conditions. A plasmid-encoded reporter gene injected into paternal pronuclei or zygotic nuclei is subjected to two competiting reactions: assembly into an active transcription complex and assembly into a repressed chromatin state. Coinjection of purified histones into the paternal pronuclei restores promoter repression. The enhancer-specific coactivator activity that appears at ZGA (32 hpf) is required for enhancer function and mediates the interaction of enhancers with promoters, presumably by direct interaction with enhancer-activation proteins and the transcription complex that forms at the promoter (31). Thus, coinjecting purified histones and plasmid DNA into the paternal pronuclei and assaying the plasmid-encoded enhancer activity at 32 hpf can reconstitute both promoter repression and enhancer-mediated relief of this repression. It is not clear whether the enhancer-specific coactivator interacts either with the enhancer activation proteins or the transcription complex in the absence of chromatin formation.

Expression from microinjected plasmids reflects physiological regulation.

Because mammalian embryos are available in limited quantities, they are not amenable to biochemical analysis. This makes it difficult to identify cis-acting sequences and trans-acting factors that are required for DNA transcription or replication at the beginning of mammalian development. One solution to this problem has been to inject plasmid DNA into the germinal vesicles of oocytes (precursors to the maternal pronucleus), the paternal or maternal pronuclei of one-cell embryos, or the zygotic nuclei of two-cell embryos and then identify various sequences and factors that are required to either replicate the plasmid or to express an encoded reporter gene (27, 28, 37). These transient assays, like those used to assay transfected cell lines, reveal the DNA replication or transcriptional environment of the oocytes and the embryos, their capacity to replicate or express genes, their ability to utilize specific trans-acting factors, and their ability to respond to specific cis-acting sequences. The following observations indicate that the injected plasmid DNA responds to the same cellular signals that regulate endogenous DNA replication and gene expression and, therefore, that our model can be used to understand physiological regulation at the beginning of mouse development.

Injected DNA undergoes replication and transcription (i) only when unique eukaryotic regulatory sequences are present and (ii) only in cells that can replicate their own DNA (27, 28, 37). For example, because mouse oocytes are arrested in prophase of their first meiosis, they cannot replicate DNA. Accordingly, plasmid DNA does not replicate when injected into mouse oocytes, even if the injected DNA contains a viral origin and the appropriate viral proteins are provided (14, 32). Although mouse oocytes cannot replicate DNA, they express some of their genes. Likewise, injected plasmids are also immediately expressed. The same sequence that induces oocyte-specific expression of zona pellucida protein-3 when integrated into the chromosomes of transgenic animals (25, 40) also induces oocyte-specific expression when present on injected plasmid DNA (34).

Mouse one-cell and two-cell embryos do replicate their genomic DNA. Accordingly, plasmid DNA replicates when injected into either one-cell or two-cell embryos, but only if it has a polyomavirus origin core sequence in cis and the polyomavirus replication protein, large T-antigen, is provided (32). In the absence of a functional replication origin, plasmid DNA does not replicate in mouse embryos. With respect to transcription, the zygotic clock initiates expression of zygotic genes at about 32 hpf, which is when the embryo is at the two-cell stage. Plasmid-encoded promoters injected into the pronuclei of S-phase-arrested one-cell embryos do not direct the expression of the linked gene before 32 hpf. In contrast, these promoters are immediately active when injected after 32 hpf into S-phase-arrested one-cell embryos or either S phase-arrested or developing two-cell embryos (21, 28, 37). Similarly, endogenous genes are more strongly expressed in the paternal pronuclei of S-phase-arrested one-cell embryos than in either the maternal pronuclei of S-phase-arrested one-cell embryos or the zygotic nuclei of two-cell embryos, most likely because of the lack of chromatin-mediated repression in the paternal pronuclei (4). This pattern of expression of endogenous genes is very similar to that of plasmid-encoded genes microinjected into these types of nuclei (23, 30, 45, 46, 51, 52). As shown in this work, reconstitution of chromatin-mediated repression on plasmid-borne promoters injected into S-phase-arrested one-cell embryos transforms the expression pattern of these promoters into that observed in two-cell embryos, again strengthening this correlation. Furthermore, both plasmid-borne reporter genes and endogenous genes use TATA-less promoters more efficiently than TATA-containing promoters in the undifferentiated blastomeres compared to the differentiated oocytes (11, 29). These observations strongly argue that the expression from microinjected plasmids accurately reflects the inherent mechanisms these embryos and oocytes use for transcription of endogenous genes. Interestingly, similar regulation of gene expression from microinjected plasmids is also observed in rabbits (8, 13).

Role of endogenous histones in the reconstitution of enhancer function in paternal pronuclei.

Although early one-cell embryos lack synthesis of certain chromatin components, namely, histones H2A, H2B, and H1, later-stage embryos (late one-cell stage and older) synthesize them, as well as isoforms of histone H4 (2, 4, 46, 52, 55). However, the paternal pronuclei of S-phase-arrested one-cell embryos do not show chromatin-mediated repression for a long time (at least not until 60 hpf). In contrast, such chromatin-based repression is observed in either S-phase-arrested or normally developing two-cell embryos. Our reconstitution of enhancer function in the paternal pronuclei of arrested one-cell embryos, which occurs only after injection of exogenous histones, suggests that the histone components required to produce repression and subsequent derepression by enhancers are not present in sufficient amounts in these embryos. This is consistent with the observation that arrested one-cell embryos undergo a drastic decline in overall protein synthesis, including that of histones (52). The other possibilities are that the endogenous components are present in these embryos in functionally inactive forms or, for some reason, such as differential nuclear localization or histone loading (1, 50), are unable to act on microinjected DNA. Finally, although exogenous histones in arrested one-cell embryos reconstituted promoter repression and subsequent derepression by enhancers, it is not clear whether the additional components of chromatin assembly and modification that are active in other biological systems are missing from this system.

It has been postulated that the expression of somatic histone H1 is a critical factor in the initiation of the transcriptionally repressed state observed in two-cell embryos (21, 28). We observe that under our reconstitution conditions that only a twofold-lower concentration of core histones plus histone H1 is required to produce the same amount of repression compared to core histones alone (Fig. 4A and B; <0.1 versus <0.2 μg/μl, respectively). Furthermore, at the optimal concentration of both core histones plus histone H1 and core histones alone (0.04 μg/μl), the levels of enhancer-mediated promoter stimulation were of a similar magnitude (Fig. 4C), indicating that exogenous H1 did not have a major role in our enhancer-reconstitution system. Whether at this concentration the function of histone H1 can be provided by endogenous histone H1 is not clear, since reports differ on when somatic histone H1 is expressed during this window of time (1, 9, 52), and the microinjection of somatic histone H1 into one-cell embryos did not produce a transcriptionally repressed state (45).

Paternal pronuclei as an in vivo model system for studying chromatin-mediated transcription.

Because DNA in our cells is present as chromatin, any biological process that requires interaction with DNA, including enhancer-mediated transcription, requires unmasking of chromatin structure so that transcription factors can gain access to appropriate DNA sequences (18, 22, 43, 56). This in turn controls both normal biological processes such as development and abnormal processes such as cancer (15). The recent discovery that cancer-regulating molecules such as Rb (6), BRCA-1 (5), Mi2β (58), and REST/NRSF (24) exert their action by modulating chromatin structure has brought a new direction to this area of research. Studies of nonmammalian systems, as well as mammalian cell culture, and in vitro systems indicated that the role of a transcription factor may involve recruitment of chromatin-modifying machinery that results in covalent modification of histone “tails” or noncovalent ATP-dependent “remodeling” of nucleosome structure (7, 36, 39, 47, 48).

In addition, chromatin-remodeling machinery such as SWI/SNF may also modify histones (7, 36, 39, 47, 48). In fact, more and more proteins and protein complexes that perform such modifications are being discovered, suggesting that they have specific roles in this process. Specific amino acids of the target histones appears to be modified by some of these proteins, especially the enzymes performing histone acetylation (histone acetyltransferases). Furthermore, deletion of different histone acetyltransferases genes in knockout mice produces different phenotypes, again suggesting that these genes have specific roles during normal development (39, 57). Therefore, it has been postulated that different histone acetyltransferases either by themselves or in concert produce a very precise pattern of histone acetylation with a specific effect on transcription (7, 39, 47). Although a large number of studies have documented acetylation and deacetylation of histones, the effects of phosphorylation, methylation, and other modifications of the core histones have been less well studied. Thus, various pathways may result in modification of global as well as specific target histones. However, deciphering this “histone code” remains a major challenge. The ability to reconstitute promoter repression and subsequent relief of this repression by enhancers in the paternal pronuclei by microinjection of purified histones provide a physiological system in which specific interactions between an enhancer activation protein and a specific histone or a particular domain within the histone can be examined by using mutant or modified histones.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We regret that we could not cite many outstanding research articles because of space limitations and so cite only a few review articles. We are grateful to the two anonymous reviewers and to Mel DePamphilis, Jim Kadonaga, Richard Schultz, and Maureen Goode for their invaluable ideas and suggestions.

This work was supported in part by a grant to S.M. from the National Institutes of Health (GM53454). L.R. was supported by a Translational Research Award from the American Brain Tumor Association.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adenot P G, Campio E, Legouy E, Allis C D, Dimitrov S, Renard J, Thompson E M. Somatic linker histone H1 is present throughout mouse embryogenesis and is not replaced by variant H1 degrees. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:2897–2907. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.16.2897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adenot P G, Mercier Y, Renard J-P, Thompson E M. Differential H4 acetylation of paternal and maternal chromatin precedes DNA replication and differential transcriptional activity in pronuclei of one-cell mouse embryos. Development. 1997;124:4615–4625. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.22.4615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Almouzni G, Wolffe A P. Replication-coupled chromatin assembly is required for the repression of basal transcription in vivo. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2033–2047. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.10.2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aoki F, Worrard D M, Schultz R. Regulation of transcriptional activity during the first and second cell cycles in the preimplantation mouse embryos. Dev Biol. 1997;181:296–307. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.8466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bochar D A, Wang L, Beniya H, Kinev A, Xue Y, Lane W S, Wang W, Kashanchi F, Shiekhattar R. BRCA1 is associated with a human SWI/SNF-related complex: linking chromatin remodeling to breast cancer. Cell. 2000;102:257–265. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brehm A, Miska E A, McCance D J, Reid J L, Bannister A J, Kouzarides T. Retinoblastoma protein recruits histone deacetylase to repress transcription. Nature. 1998;391:597–601. doi: 10.1038/35404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheung P, Allis C D, Sassone-Corsi P. Signaling to chromatin through histone modification. Cell. 2000;103:263–271. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00118-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christians E, Campion E, Thompson E M, Renard J P. Expression of the Hsp 70.1 gene, a landmark of early zygotic activity in the mouse embryo, is restricted to the first burst of transcription. Development. 1995;121:113–122. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clarke H J, Oblin C, Bustin M. Developmental regulation of chromatin composition during mouse embryogenesis: somatic histone H1 is first detectable at the 4-cell stage. Development. 1992;115:791–799. doi: 10.1242/dev.115.3.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conover J C, Temeles G L, Zimmerman J W, Burke B, Schultz R. Stage-specific expression of a family of proteins that are major products of zygotic gene activation in the mouse embryo. Dev Biol. 1991;144:392–404. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(91)90431-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis W, Jr, Schultz R M. Developmental changes in TATA-box utilization during preimplantation mouse development. Dev Biol. 2000;218:275–283. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Moor C H, Richter J D. Translational control in vertebrate development. Int Rev Cytol. 2001;203:567–608. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(01)03017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delouis C, Bonnerot C, Vernet M, Nicolas J F. Expression of microinjected DNA and RNA in early rabbit embryos: changes in permissiveness for expression and transcriptional selectivity. Exp Cell Res. 1992;201:284–291. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(92)90275-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DePamphilis M L. Review: nuclear structure and DNA replication. J Struct Biol. 2000;129:186–197. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DePinho R A. Transcriptional repression: the cancer-chromatin connection. Nature. 1998;391:533–536. doi: 10.1038/35257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doherty A S, Schultz R M. Culture of preimplantation mouse embryos. Methods Mol Biol. 2000;135:47–52. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-685-1:47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forlani S, Bonnerot C, Capgras S, Nicolas J-F. Relief of a repressed gene expression state in the mouse one-cell embryo requires DNA replication. Development. 1998;125:3153–3166. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.16.3153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fry C J, Farnham P J. Context-dependent transcriptional regulation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:29583–29586. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.42.29583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henery C C, Miranda M, Wiekowski M, Wilmut I, DePamphilis M L. Repression of gene expression at the beginning of mouse development. Dev Biol. 1995;169:448–460. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Imhof A, Wolffe A P. Transcription: gene control by targeted histone acetylation. Curr Biol. 1998;8:R422–R424. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70268-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaneko K J, DePamphilis M L. Regulation of gene expression at the beginning of mammalian development and the TEAD family of transcription factors. Dev Genet. 1998;22:43–55. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1998)22:1<43::AID-DVG5>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kornberg R D, Lorch Y. Twenty-five years of the nucleosome, fundamental perticel of the eukaryote chromosome. Cell. 1999;98:285–294. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81958-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawinger P, Rastelli L, Zhao Z, Majumder S. Lack of enhancer function in mammals is unique to oocytes and fertilized eggs. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:8002–8011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.12.8002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lawinger P, Venugopal R, Guo Z-S, Immaneni A, Rastelli L, Sengupta D, Lu W, Zhao Z, Carneiro A, Fuller G, Echelard Y, Majumder S. Expression of REST/NRSF is a critical phenotype of medulloblastoma cells. Nat Med. 2000;6:826–831. doi: 10.1038/77565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lira S A, Kinloch R A, Mortillo S, Wassarman P. An upstream region of the mouse ZP3 gene directs expression of firefly luciferase specifically to growing oocytes in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7215–7219. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.18.7215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luger K, Richmond T J. The histone tails of the nucleosome. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1998;8:140–146. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(98)80134-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Majumder S. Mouse preimplantation embryos as an in vivo system to study gene expression. In: Cid-Arregui A, Garcia-Carranca A, editors. Microinjection and transgenesis: strategies and protocols. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1997. pp. 323–349. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Majumder S, DePamphilis M L. A unique role for enhancers is revealed during early mouse development. Bioessays. 1995;17:879–889. doi: 10.1002/bies.950171010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Majumder S, DePamphilis M L. TATA-dependent enhancer stimulation of promoter activity in mice is developmentally acquired. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:4258–4268. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.6.4258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Majumder S, Miranda M, DePamphilis M. Analysis of gene expression in mouse preimplantation embryos demonstrates that the primary role of enhancers is to relieve repression of promoters. EMBO J. 1993;12:1131–1140. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05754.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Majumder S, Zhao Z, Kaneko K, DePamphilis M L. Developmental acquisition of enhancer function requires a unique coactivator activity. EMBO J. 1997;16:1721–1731. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.7.1721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martínez-Salas E, Cupo D Y, DePamphilis M L. The need for enhancers is acquired upon formation of a diploid nucleus during early mouse development. Genes Dev. 1988;2:1115–1126. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.9.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martínez-Salas E, Linney E, Hassell J, DePamphilis M L. The need for enhancers in gene expression first appears during mouse development with formation of a zygotic nucleus. Genes Dev. 1989;3:1493–1506. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.10.1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Millar S E, Lader E, Liang L-F, Dean J. Oocyte specific factors bind a conserved upstream sequence required for mouse zona pellucida promoter activity. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:6197–6204. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.12.6197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miranda M, Majumder S, Wiekowski M, DePamphilis M L. Application of firefly luciferase to preimplantation development. Methods Enzymol. 1993;225:412–433. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(93)25029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peterson C L, Workman J L. Promoter targeting and chromatin remodeling by the SWI/SNF complex. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2000;10:187–192. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rastelli L, Majumder S. The role of chromatin in the establishment of enhancer function during early mouse development. Gene Ther Mol Biol. 1999;3:455–464. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robinson K M, Kadonaga J T. The use of chromatin templates to recreate transcriptional regulatory phenomena in vitro. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1998;1378:M1–M6. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(98)00008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roth, S., Y., J. M. Denu, and C. D. Allis. Histone acetyltransferases. Annu. Rev. Biochem., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Schickler M, Lira S A, Kinloch R A, Wassarman P. A mouse oocyte specific protein that binds to a region of mZP3 promoter is responsible for oocyte specific mZP3 gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:120–127. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.1.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schultz R M. Regulation of zygotic gene activation in the mouse. Bioessays. 1993;8:531–538. doi: 10.1002/bies.950150806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schultz R M, Davis W, Stein P, Svoboda P. Reprogramming of gene expression during preimplantation development. J Exp Zool. 1999;285:276–282. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-010x(19991015)285:3<276::aid-jez11>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sera T, Wolffe A P. Role of histone H1 as an architectural determinant of chromatin structure and as a specific repressor of transcription of Xenopus oocyte 5S rRNA genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3668–3680. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.3668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simon R H, Felsenfeld G. A new procedure for purifying histone pairs H2A+H2B and H3+H4 from chromatin using hydoxylapatite. Nucleic Acids Res. 1979;6:689–696. doi: 10.1093/nar/6.2.689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stein P, Schultz R M. Initiation of a chromatin-based transcriptionally repressive state in the preimplantation mouse embryo: lack of a primary role for expression of somatic histone H1. Mol Reprod Dev. 2000;55:241–248. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(200003)55:3<241::AID-MRD1>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stein P, Worrad D M, Belyaev N D, Turner B M, Schultz R M. Stage-dependent redistributions of acetylated histones in nuclei of the early preimplantation mouse embryos. Mol Reprod Dev. 1997;47:421–429. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199708)47:4<421::AID-MRD8>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strahl B D, Allis C D. The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature. 2000;403:41–45. doi: 10.1038/47412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sudarsanam P, Winston F. The Swi/Snf family: nucleosome-remodeling complexes and transcriptional control. Trends Genet. 2000;16:345–355. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)02060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tyler J K, Adams C R, Chen S-R, Kobayashi R, Kamakaka R T, Kadonaga J T. The RCAF complex mediates chromatin assembly during DNA replication and repair. Nature. 1999;402:555–560. doi: 10.1038/990147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vignali M, Workman J L. Location and function of linker histones. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:1025–1028. doi: 10.1038/4133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wiekowski M, Miranda M, DePamphilis M L. Requirements for promoter activity in mouse oocytes and embryos distinguish paternal pronuclei from maternal and zygotic nuclei. Dev Biol. 1993;159:366–378. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1993.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wiekowski M, Miranda M, Nothias J-Y, Turner B M, DePamphilis M L. Changes in histone synthesis and modification at the beginning of mouse development correlate with the establishment of chromatin mediated repression of transcription. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:1147–1158. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.10.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Workman J L, Kingston R E. Alteration of nucleosomal structure as a mechanism of transcriptional regulation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:545–579. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Worrard D M, Schultz R M. Regulation of gene expression in the preimplantation mouse embryo: temporal and spatial patterns of expression of the transcription factor Sp1. Mol Reprod Dev. 1997;46:268–277. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199703)46:3<268::AID-MRD5>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Worrard D M, Turner B M, Schultz R M. Temporally restricted spatial localization of acetylated isoforms of histone H4 and RNA polymerase II in the two-cell mouse embryo. Development. 1995;121:2949–2959. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.9.2949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu J, Grunstein M. 25 years after the nucleosome model: chromatin modification. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:619–623. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01718-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xu W, Edmondson D G, Evrard Y A, Wakamiya M, Behringer R R, Roth S Y. Loss of gcn512 leads to increased apoptosis and mesodermal defects during mouse development. Nat Genet. 2000;26:229–232. doi: 10.1038/79973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang Y, Leroy G, Seelig H-P, Lane W S, Reinberg D. The dermatomyositis-specific autoantigen Mi2 is a component of a complex containing histone deacetylase and nucleosome remodeling activities. Cell. 1998;95:279–289. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81758-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]