Abstract

Objectives: To develop a thematic framework for the range of consequences arising from a diagnostic label from an individual, family/caregiver, healthcare professional, and community perspective.

Design: Systematic scoping review of qualitative studies.

Search Strategy: We searched PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, Cochrane, and CINAHL for primary studies and syntheses of primary studies that explore the consequences of labelling non-cancer diagnoses. Reference lists of included studies were screened, and forward citation searches undertaken.

Study Selection: We included peer reviewed publications describing the perceived consequences for individuals labelled with a non-cancer diagnostic label from four perspectives: that of the individual, their family/caregiver, healthcare professional and/or community members. We excluded studies using hypothetical scenarios.

Data Extraction and Synthesis: Data extraction used a three-staged process: one third was used to develop a preliminary framework, the next third for framework validation, and the final third coded if thematic saturation was not achieved. Author themes and supporting quotes were extracted, and analysed from the perspective of individual, family/caregiver, healthcare professional, or community member.

Results: After deduplication, searches identified 7,379 unique articles. Following screening, 146 articles, consisting of 128 primary studies and 18 reviews, were included. The developed framework consisted of five overarching themes relevant to the four perspectives: psychosocial impact (e.g., positive/negative psychological impact, social- and self-identity, stigma), support (e.g., increased, decreased, relationship changes, professional interactions), future planning (e.g., action and uncertainty), behaviour (e.g., beneficial or detrimental modifications), and treatment expectations (e.g., positive/negative experiences). Perspectives of individuals were most frequently reported.

Conclusions: This review developed and validated a framework of five domains of consequences following diagnostic labelling. Further research is required to test the external validity and acceptability of the framework for individuals and their family/caregiver, healthcare professionals, and community.

Keywords: labelling, diagnosis, consequences, qualitative, scoping review

Introduction

Worldwide there has been an increase in the use of diagnostic labels for both physical and psychological diagnoses (1, 2). Diagnoses reflects the process of classifying an individual who presents with certain signs and symptoms as having, or not having, a particular disease (3). The diagnostic process can involve various assessments and tests, however, culminates to a “diagnostic label” that is communicated to the individual (4). The term “diagnostic label” will be used to indicate diagnosis or labelling of health conditions listed in current diagnostic manuals (5, 6). Diagnostic definitions and criteria continue to expand and, with this, individuals who are asymptomatic or experience mild symptoms are increasingly likely to receive a diagnostic label (7, 8). It is acknowledged that the consequences of a diagnostic label are likely individual, and how each is perceived is dependent on numerous internal (e.g., medical history, age, sex, culture) and external (e.g., service availability, country) factors, and differs by perspective (9). Motivation for expanding disease definitions and increased labelling includes the presumed benefits such as validation of health concerns, access to interventions, and increased support (3, 10). However, often less considered are the problematic or negative consequences of a diagnostic label. This may include increased psychological distress, preference for invasive treatments, greater sick role behaviour, and restriction of independence (11–14). Additionally, research indicates the impact of a label is diverse and varies depending on your perspective as an individual labelled (15, 16), family/caregiver (15, 17, 18), or healthcare professional (15, 19).

Psychosocial theories, including social constructionism, labelling theory, and modified labelling theory, have attempted to explain the varied influence of labels on an individuals' well-being and identity formation, in addition to society's role in perpetuating assumptions and necessity of particular labels (3, 20–22). In terms of quantifying this impact, research to date has examined the impact of changes to diagnostic criteria (e.g., cut-points/thresholds), how and when diagnoses are provided (e.g., tests used, detection through screening, or symptom investigation), the prevalence of diagnoses, or treatment methods and outcomes (4, 23–26). However, clinicians and researchers have paid relatively less attention to the consequences a diagnostic label has on psychological well-being, access to services, and perceived health. Of particular concern, are the implications of a diagnostic label for people who are asymptomatic or present with mild signs and symptoms are of critical importance as it is this group of people who are less likely to benefit from treatments and are at greater risk of harm (4, 27).

The limited work in this area has reported on individual diagnostic labels, used hypothetical case scenarios, or failed to differentiate between condition symptoms and condition label (28, 29). Few studies have synthesised the real-world consequences of diagnostic labelling, with existing syntheses restricted to a specific condition or limited in the methodological approach used (e.g., hypothetical case-studies) (30–32). This suggests a paucity of information available for individuals, their family/caregivers, healthcare professionals, and community members to understand the potential consequences of being given a diagnostic label. Therefore, the aim of this scoping review is to identify and synthesise the potential consequences of a diagnostic label from the perspective of an individual who is labelled, their family/caregiver, healthcare professional, and community members.

Methods

Design

This systematic scoping review was conducted and reported in accordance with the published protocol (33), the Joanna Briggs Methodology for Scoping Reviews (34), and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (35). Originally, we proposed to report the results of both qualitative and quantitative studies together, however, due to the large volume of included studies and the richness of the data, only results from the qualitative studies are reported in this paper. Results from quantitative studies will be reported separately. Subsequently, this article presents the results of the qualitative synthesis.

Search Strategy

An electronic database search was conducted in PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, Cochrane, and CINAHL from database inception to 8 June 2020. The search strategy combined medical subject headings and key word terms related to “diagnosis” and “effect” (see PubMed Search Strategy in Supplementary Material). Forward and backward citation searching was conducted to identify additional studies not found by the database search.

Inclusion Criteria

We included peer reviewed publications, both primary studies and systematic or literature reviews, that reported on consequences of a diagnostic label for a non-cancer diagnosis. Included studies could report consequences from the perspectives of the individual, their family, friends, and/or caregivers, healthcare professional, or community member.

Studies reporting labelling of cancer conditions were excluded as existing research suggests that individuals labelled as having a cancer condition may report different experiences, for example, associating the condition with lethality, or desiring invasive treatments, to those labelled with other physical (e.g., diabetes, polycystic ovarian syndrome) or psychological (e.g., autism spectrum disorder, dementia) diagnoses (36–39). Similarly, hypothetical scenarios, or labelling of individuals with intellectual disabilities and/or attributes such as race, sexual identity, or sexual orientation were also excluded.

Study Selection

Published studies retrieved by database searches were exported to EndNote and deduplicated. Two reviewers (RS, LK) independently screened ~10% of studies and achieved an interrater reliability of kappa 0.92. Disagreements were resolved by discussion or additional reviewers (RT, ZAM) as necessary. The remaining screening was completed by one reviewer (RS), with studies identified as unclear for inclusion reviewed by additional reviewers (RT, ZAM) as required.

Preliminary Framework Development

Prior to commencement of this scoping review, a poll was conducted on social media (Twitter, Facebook) asking a single question about people's experiences of receiving a diagnostic label and any associated consequences. A preliminary framework was developed and agreed upon by members of the research team from the responses received from 46 people. The preliminary framework included five primary themes and seven sub-themes detailed in the published protocol (33). This preliminary framework was used as a starting point from which to iteratively develop and synthesise the range of consequences that emerged from the studies included in this review.

Data Extraction and Analysis

Once eligible articles were identified, data was extracted and analysed from randomly selected articles using a three-stage process. The first stage (i.e., first third of randomly selected articles) was used to iteratively develop the framework. The second stage (i.e., second third of randomly selected articles) was used to examine the framework for completeness and explore the extracted data for thematic saturation. The final third of included studies was to be extracted and analysed only if saturation had not occurred. Thematic saturation was defined as the non-emergence of new themes that would result in revision of the framework (40).

Three authors (RS, RT, and ZAM) independently extracted data from 10% of the first third of included studies and mapped this to the preliminary framework. As new consequences were identified the framework was revised and subthemes emerged. Conflicts were resolved through discussion. One reviewer (RS) completed extraction of the remaining studies in the first third. Reflexivity was achieved through regular discussions with an additional reviewer (RT or ZAM) to ensure articles were relevant, coding was reliable, and homogeneity existed between data extracted to major themes and subthemes (41, 42). When data extraction was completed, two additional reviewers (RT and ZAM) examined the extracted data and disagreements in coding were resolved through discussion.

Extracted data included study characteristics (author, journal, year of publication, study country, and setting), participant characteristics (number of participants, age, diagnostic label), and abstracted themes and relevant supporting quotes identified by the authors of the included studies that pertained to the consequences of a diagnostic label. Direct quotes were not extracted in isolation to preserve the author's meaning and ensure contextual understanding from the primary study was retained. These qualitative meta-analysis techniques have been described elsewhere (43–45).

Results

Search Results

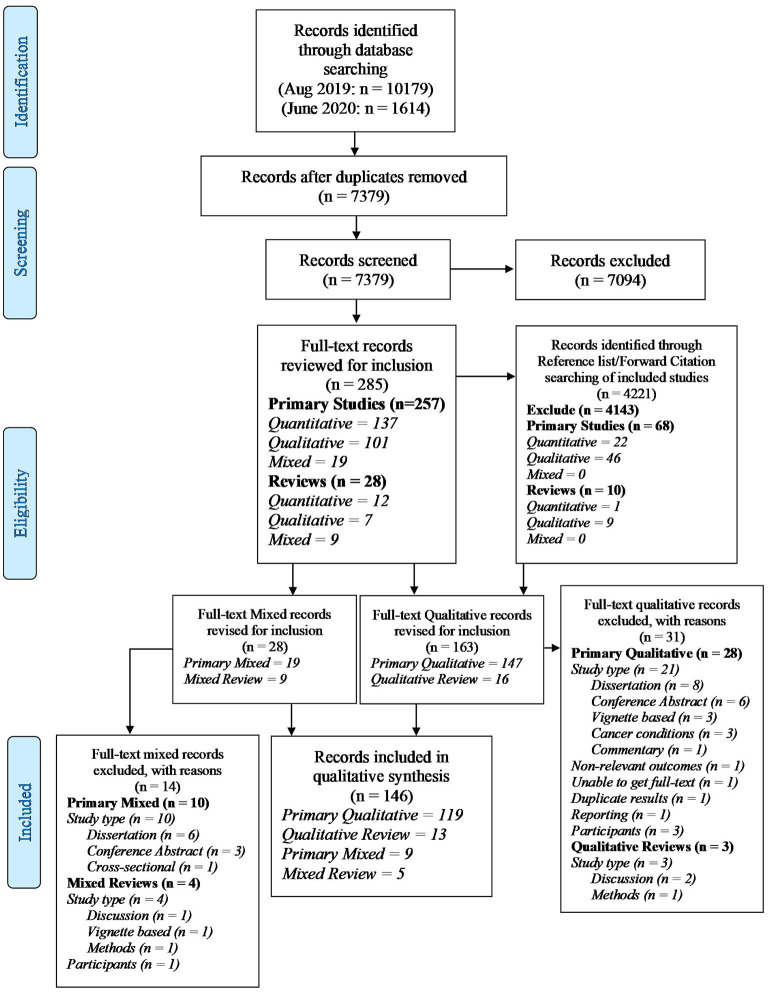

Searches identified 16,014 unique records which we screened for inclusion. Full texts were retrieved for 191 qualitative studies, of which 146 (128 studies, 18 reviews) were included in this systematic scoping review (Figure 1). Data extraction was completed using the staged processed described above. Saturation of themes was achieved by the conclusion of the second stage of data extraction. Therefore, 97 studies (of which 13 were reviews) directly informed our results.

Figure 1.

PRISMA-ScR flow diagram.

Of the studies that directly informed the coding framework, 61 examined physical diagnostic labels (e.g., diabetes, female reproductive disorders) and 36 examined psychological diagnostic labels (e.g., autism spectrum disorder, dementia). Over half of the studies (58%, 56/97) reported individual perspectives on being labelled with a diagnostic label, 9% (9/97) reported on family/caregiver perspectives, 14% (14/97) reported healthcare professional perspectives, and 19% (18/97) reported multiple (including community) perspectives. Key characteristics of the included studies are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Key characteristics of extracted qualitative studies and reviews.

| References | Condition* (Scr, Sym, NR, Mix) | Country | Participants | N | Age Range (years) | % Female | Data collection | Data analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular disease | ||||||||

| Asif et al. (46) | Cardiac conditions (Scr) | USA | Individual | 25 | 14–35 | 48 | Individual semi-structured interview | Consensual qualitative research |

| Chronic kidney disease | ||||||||

| Daker-White et al. (47) | Chronic kidney disease (Sym) | UK | Individual (control arm of trial) | 13 | 59–89 | 69.2 | Individual interview | Grounded theory |

| Individual (intervention arm of trial) | 13 | 59–89 | 61.5 | |||||

| Diabetes | ||||||||

| Twohig et al. (48) | Pre-diabetes (Sym) | UK | Individual | 23 | 37–81 | 56 | Individual semi-structured interview | Thematic analysis with interpretivist analytical approach |

| Burch et al. (49) | Pre-diabetes (NR) | UK | GP, GP registrar, nurse practitioners, practise nurse, healthcare assistant, patient advocates | 17 | NR | NR | Individual semi-structured interview | Grounded theory approach |

| 7 | NR | NR | Focus groups (n = 2) | |||||

| de Oliveira et al. (50) | Diabetes (NR) | Brazil | Individual | 16 | NR | NR | Focus groups (n = 4) | Thematic content analysis |

| Due-Christensen et al. (51) | Type 1 diabetes (NR) | Canada, Sweden, UK | Individual | 124 | 23–58 | NR | Systematic review | Meta-synthesis |

| Sato et al. (52) | Type 1 diabetes (NR) | Japan | Individual | 13 | 21–35 | 77 | Individual semi-structured interview | NR |

| Jackson et al. (53) | Type 1 diabetes (Sym) | UK | Siblings | 41 | 7–16 | 58.5 | Individual semi-structured interview | Grounded theory |

| Fharm et al. (54) | Type 2 diabetes (NR) | Sweden | GPs | 14 | 43–64 | 57.1 | Focus group (n = 4) | Qualitative content analysis |

| Kaptein et al. (55) | GDM (Scr) | Canada | Individual | 19 | 29–50 | 100 | Semi-structured interview | Conventional content analysis |

| Singh et al. (56) | GDM (Scr) | USA | Individual | 29 | NR | 100 | Semi-structured interview | Thematic analysis |

| Female reproduction | ||||||||

| Copp et al. (57) | PCOS (Sym) | Australia | Individual | 26 | 18–45 | 100 | Individual semi-structured interview | Framework |

| Copp et al. (58) | PCOS (Sym) | Australia | GPs, gynaecologists, endocrinologists | 36 | NR | 72.2 | Individual semi-structured interview | Framework analysis |

| Newton et al. (59) | Pelvic inflammatory disease (NR) | Australia | Individual | 23 | 18–46 | 100 | Semi-structured interview | Inductive thematic approach |

| O'Brien et al. (60) | Anti-Mullerian hormone testing (Scr) | Ireland | Individual | 10 | 24–69 | 100 | Semi-structured interview | Thematic analysis |

| Patterson et al. (61) | MRKH (Sym) | UK | Individual | 5 | 18–22 | 100 | Individual semi-structured interview | Interpretative phenomenological approach |

| Harris et al. (62) | Pre-eclampsia (Scr) | UK | Individual | 10 | 28–36 | 100 | Semi-structured interview | Framework analysis |

| Genome/Chromosome | ||||||||

| Delaporte (63) | Facioscapulohumeral dystrophy (Sym) | France | Individual | 22 | NR | NR | Individual semi-structured interview | Content analysis |

| Neurologists | 10 | NR | NR | |||||

| Houdayer et al. (64) | Chromosomal abnormalities (Scr) | France | Parents | 60 | NR | 63.3 | Individual semi-structured interview | Transversal analysis |

| Geneticists | 5 | NR | NR | |||||

| HIV/AIDS | ||||||||

| McGrath et al. (65) | AIDS (NR) | Uganda | Individual | 24 | 18–55 | 58 | Individual semi-structured interview and observations | NR |

| Family members | 22 | NR | NR | |||||

| Anderson et al. (66) | HIV (NR) | UK | Individual | 25 | NR | 20 | Individual semi-structured interview | NR |

| Freeman (67) | HIV (NR) | Malawi | Individual | 18 | 50–70 | NR | Individual interview | Constructivist grounded theory |

| Individual attending support group | NR | 30–75 | NR | Focus group (n = 3) | ||||

| Kako et al. (68) | HIV (NR) | Kenya | Individual | 40 | 26–54 | 100 | Individual interview | Multistage narrative analysis |

| Kako et al. (69) | HIV (NR) | Kenya | Individual | 24 | 20–39 | 100 | Semi-structured interview | Thematic analysis |

| Stevens and Hildebrandt (70) | HIV (NR) | USA | Individual | 55 | 23–54 | 100 | Individual interview | NR |

| Firn and Norman (71) | HIV/AIDS (Sym) | UK | Individual | 7 | NR | 28.6 | Individual semi-structured interview | Inductive categorisation |

| Nurses | 10 | NR | 80 | |||||

| Immune system | ||||||||

| Hale et al. (72) | Systemic lupus erythematosus (Sym) | UK | Individual | 10 | 26–68 | 100 | Individual semi-structured interview | Interpretative phenomenological approach |

| Infectious/Parasitic | ||||||||

| Almeida et al. (73) | Leprosy (NR) | Brazil | Individual | 14 | 21–80 | 57 | Individual semi-structured interview | NR |

| Silveira et al. (74) | Leprosy (NR) | Brazil | Individual | 5 | 36–70 | NR | Unstructured interview | Content analysis |

| Zuniga et al. (75) | Tuberculosis (NR) | USA | Individual | 13 | NR | 0 | Semi-structured interview | Secondary analysis using qualitative descriptive methods |

| Dodor et al. (76) | Tuberculosis (NR) | Ghana | Individual | 34 | NR | 29.4 | Individual semi-structured interview | Grounded theory |

| 65 | NR | 24.6 | Focus groups (n = 6) | |||||

| Community members | 66 | NR | 56.1 | Individual semi-structured interview | ||||

| 177 | NR | 46.3 | Focus groups (n = 16) | |||||

| Metabolic | ||||||||

| Bouwman et al. (77) | Fabry disease (NR) | Netherlands | Individual | 30 | 12–68 | 57 | Semi-structured interview | NR |

| Musculoskeletal | ||||||||

| Erskine et al. (78) | Psoriatic arthritis (Sym) | UK | Individual | 41 | 46.6–69–4 | 51.2 | Focus groups (n = 8) | Secondary analysis using deductive thematic analysis |

| Martindale and Goodacre (79) | Axial spondyloarthritis (Sym) | UK | Individual | 10 | 26–49 | 30 | Individual semi-structured interview | Interpretative phenomenological approach |

| Hopayian and Notley (80) | Low back pain/sciatica (Sym) | Australia, Finland Ireland, Israel, Netherlands, Norway, UK, USA | Individual | NR | NR | NR | Systematic review | Thematic content analysis |

| Barker et al. (81) | Osteoporosis (Mix) | Brazil, Canada, Denmark, Sweden, UK, USA | Individual | 773 | 33–93 | 89.2 | Review | Meta-ethnography |

| Hansen et al. (82) | Osteoporosis (NR) | Denmark | Individual | 15 | 65–79 | 100 | Individual interview | Phenomenological hermeneutic approach |

| Weston et al. (83) | Osteoporosis (Scr) | UK | Individual | 10 | 68–79 | 100 | Individual semi-structured interview | Interpretative phenomenological approach |

| Boulton (84) | Fibromyalgia (Sym) | Canada, UK | Individual | 31 | 21–69 | 81 | Individual semi-structured interview | Narrative analysis |

| Madden Sim (85) | Fibromyalgia (Sym) | UK | Individual | 17 | 25–55 | 94 | Individual semi-structured interview | Induction-abduction method |

| Mengshoel et al. (86) | Fibromyalgia (Sym) | Africa, Belgium, Canada, Finland, France, Japan, Mexico, Norway, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, UK, USA | Individual | 475 | 16–80 | 94.7 | Review | Meta-ethnography |

| Raymond and Brown (87) | Fibromyalgia (Sym) | Canada | Individual | 7 | 38–47 | 85.7 | Individual semi-structured interview | Phenomenological approach |

| Sim Madden (88) | Fibromyalgia (Sym) | Canada, Norway, Sweden, UK, USA | Individual | 383 | NR | 94 | Review | Meta-synthesis |

| Undeland and Malterud (89) | Fibromyalgia (Sym) | Norway | Individual | 11 | 42–67 | 100 | Focus Groups (n = 2) | Systematic text condensation |

| Nervous system | ||||||||

| Chew-Graham et al. (90) | CFS/ME (Sym) | UK | GPs | 22 | NR | NR | Individual semi-structured interview | Thematic analysis |

| Hannon et al. (91) | CFS/ME (Sym) | UK | Individual | 16 | 28–64 | 68.8 | Individual semi-structured interview | hematic analysis using modified grounded theory |

| Carers | 10 | 46–71 | 50 | |||||

| GPs, specialists, practise nurses | 18 | NR | 77.8 | |||||

| De Silva et al. (92) | CFS/ME (Sym) | UK | Individual | 11 | NR | 72.7 | Individual semi-structured interview | Secondary analysis |

| Carers | 2 | NR | 50 | |||||

| GPs | 9 | NR | 67 | |||||

| Community Leaders | 5 | NR | 40 | |||||

| Johnston et al. (93) | MND (Sym) | UK | Individual | 50 | 38–85 | 34 | Individual interview | NR |

| Zarotti et al. (94) | MND (Sym) | UK | Dietitians, dietetics managers, MND specialist nurses, Speech and language therapists, MND coordinators, service user representatives, GPs, physiotherapists | 51 | NR | 90 | Focus Group (n = 5) | Thematic analysis |

| Johnson (95) | Multiple sclerosis (Sym) | UK | Individual | 24 | 34–67 | 58.3 | Individual interview | Framework of data reduction, data display, and conclusion drawing/verification |

| Thompson et al. (96) | Non-epileptic seizures (Sym) | UK | Individual | 8 | NR | 100 | Semi-structured interview | Interpretative phenomenological approach |

| Wyatt et al. (97) | Non-epileptic attack disorder (Sym) | UK | Individual | 6 | 29–55 | 83.3 | Semi-structured interview | Descriptive phenomenological approach using inductive analytic approach |

| Partners | 3 | NR | 0 | |||||

| Neurological | ||||||||

| Nochi (98) | Traumatic brain injury (Sym) | USA | Individual | 10 | 24–54 | 20 | Semi-structured interview | Grounded theory |

| 13 | 26–61 | 61.5 | Written narrative accounts | |||||

| Daker-White et al. (99) | Ataxia (Sym) | NR | Individual | NR | NR | NR | Review of internet discussion forums | NR |

| Partners or parents | NR | NR | NR | |||||

| Newborn/Foetal | ||||||||

| Hallberg et al. (100) | 22q11 Deletion syndrome (Scr) | Sweden | Parents | 12 | NR | 83.3 | Conversational interview | Classical grounded theory |

| Johnson et al. (101) | Cystic fibrosis (Scr) | UK | Parents | 8 | NR | 62.5 | Semi-structured interview | Interpretative phenomenological analysis |

| Dahlen et al. (102) | GERD (Sym) | Australia | Child health nurses; enrolled/mothercraft nurses; psychiatrists; GPs; paediatricians | 45 | NR | NR | Focus Group (n = 8) | Thematic analysis |

| Sleep-Wake disorder | ||||||||

| Zarhin (103) | Obstructive sleep apnoea (Sym) | Israel | Individual | 65 | 30–66 | 47.7 | Interview | Coded thematically and analysed based on constructivist grounded theory |

| Sexually transmitted | ||||||||

| Mills et al. (104) | Chlamydia trachomatis (Scr) | UK | Individual | 25 | 18–28 | 68 | Individual semi-structured interview | Inductive |

| Rodriguez et al. (105) | HPV (NR) | Australia, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Denmark, Ireland, Mexico, Peru, Sweden, UK, USA | Individual | 34 | NR | 85.3 | Scoping review | NR |

| Multiple physical diagnoses | ||||||||

| Kralik et al. (106) | Adult-Onset chronic illness (Sym) | Australia | Individual | 81 | NR | 100 | Written narrative accounts | Secondary analysis |

| Diabetes (Sym) | Individual | 10 | NR | 100 | Focus groups (n = 8) | Secondary analysis | ||

| Bipolar disorder | ||||||||

| Fernandes et al. (107) | Bipolar disorder (Sym) | Australia | Individual | 10 | 29–68 | 100 | Individual semi-structured interview | Constant comparative method |

| Proudfoot et al. (108) | Bipolar disorder (Sym) | Australia | Individual | 26 | 18–59 | 54 | Online communication with public health service | Phenomenology and lived experience framework |

| Depression | ||||||||

| Wisdom and Green (109) | Depression (Sym) | USA | Individual | 15 | NR | 53.3 | Individual semi-structured interview | Modified grounded theory |

| Chew-Graham et al. (110) | Depression (Sym) | UK | Inner-city GPs | 22 | NR | NR | Individual semi-structured interview | Inductive thematic analysis |

| Semi-rural/Suburban GPs | 13 | NR | NR | |||||

| Neurocognitive | ||||||||

| Beard and Fox (111) | AD; MCI (Sym) | USA | Individual | 8 | NR | NR | Individual semi-structured interview | Grounded theory |

| 32 | NR | NR | Focus group (n = 6) | |||||

| Bamford et al. (112) | Dementia (Sym) | Australia, Canada, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Scotland, Sweden, UK, USA | Individual | NR | NR | NR | Systematic review | NR |

| Carers | NR | NR | NR | |||||

| GPs, Psychiatrists, Psychologists, Geriatricians, Nurses, Neurologists | NR | NR | NR | |||||

| Bunn et al. (113) | Dementia; MCI (Sym) | Asia, Australia, Canada, Europe, New Zealand, UK, USA | Individual | 74 | 40–97 | NR | Review | Thematic synthesis |

| Carers | 72 | 40–97 | NR | |||||

| Robinson et al. (114) | AD; Dementia (Sym) | UK | Individual | 9 | 73–85 | 55.6 | Semi-structured interview with partner | Interpretative phenomenological analysis |

| Partners | 9 | 68–81 | NR | |||||

| Ducharme et al. (115) | AD (Sym) | Canada | Spouses | 12 | 48.1–61.9 | 66.7 | Individual semi-structured interview | Phenomenology |

| Abe et al. (116) | Dementia (Sym) | Japan | Rural GPs | 12 | NR | 25 | Individual semi-structured interview | Thematic analysis |

| Urban GPs | 12 | NR | 33 | |||||

| Phillips et al. (117) | Dementia (Sym) | Australia | GPs | 45 | NR | NR | Individual semi-structured interview | Thematic analysis |

| Walmsley and McCormack (118) | Dementia (Sym) | Australia | Aged Care directors; GP, nurse unit manager, dementia body representative | 8 | 48–60 | 75 | Individual semi-structured interview | Interpretative phenomenological analysis |

| Werner and Doron (119) | AD (Sym) | Israel | Social workers | 16 | NR | NR | Focus group (n = 3) | Thematic analysis using constant comparative method |

| Lawyers | 16 | NR | NR | |||||

| Neurodevelopmental | ||||||||

| Carr-Fanning and Mc Guckin (120) | ADHD (Sym) | Ireland | Individual | 15 | 7–18 | 40 | Individual semi-structured interview | Thematic analysis |

| Parents | 17 | NR | 88.2 | |||||

| Mogensen and Mason (121) | ASD (Sym) | Australia | Individual | 5 | 13–18 | 40 | Individual interview, communication cards, e-mails | Interpretative phenomenological analysis |

| Fleischmann (122) | ASD (Sym) | NR | Parents | 33 | NR | NR | Web page mining | Grounded theory |

| Hildalgo et al. (123) | ASD (Sym) | USA | Primary caregiver | 46 | NR | 100 | Individual structured interview | Thematic analysis |

| Loukisas and Papoudi (124) | ASD (Sym) | Greece | Parent | 5 | 35–45 | 100 | Review of written blogs | Content analysis |

| Selman et al. (125) | ASD (Sym) | UK | Parent | 15 | 28–56 | 0 | Individual semi-structured interview | Thematic analysis |

| Smith et al. (126) | ASD (Sym) | NR | Individual | 14 | 8–21 | NR | Systematic review | NR |

| Parents | 7 | NR | NR | |||||

| Obsessive compulsive disorder | ||||||||

| Pedley et al. (127) | OCD (Sym) | UK | Family member | 14 | 25–71 | NR | Individual semi-structured interview | Thematic analysis |

| Peri/Postnatal anxiety and/or depression | ||||||||

| Ford et al. (128) | Perinatal anxiety and depression (Scr) | Australia, UK | GPs | 405 | NR | NR | Review | Meta-ethnography |

| Chew-Graham et al. (129) | Postnatal Depression (Sym) | UK | GPs | 19 | NR | NR | Individual semi-structured interview | Inductive thematic analysis |

| Health Visitors | 14 | NR | NR | |||||

| Personality disorder | ||||||||

| Horn et al. (130) | BPD (Sym) | UK | Individual | 5 | 23–44 | 80 | Individual semi-structured interview | Interpretative phenomenological analysis |

| Lester et al. (131) | BPD (Sym) | NR | Individual | 172 | NR | 75 | Systematic review | Thematic analysis |

| Nehls (132) | BPD (Sym) | USA | Individual | 30 | NR | 100 | Individual semi-structured interview | Interpretative phenomenological analysis |

| Schizophrenia/psychotic disorder | ||||||||

| Thomas et al. (133) | Schizophrenia (Sym) | NR | Individual | 97 | NR | NR | Online survey | Thematic analysis |

| Welsh and Tiffin (134) | At risk mental state (Sym) | UK | Individual | 6 | 13–18 | 50 | Individual semi-structured interview | Interpretative phenomenological analysis |

| Welsh and Tiffin (135) | At risk for psychosis (Sym) | UK | Child and adolescent mental health clinicians | 6 | NR | NR | Individual semi-structured interview | Thematic analysis |

| Multiple psychological diagnoses | ||||||||

| Hayne (136) | Mental illness (Sym) | Canada | Individual | 14 | NR | NR | NR | Hermeneutic phenomenological study; Thematic analysis |

| McCormack and Thomson (137) | Depression; PTSD (Sym) | Australia | Individual | 5 | 38–62 | 60 | Individual semi-structured interview | Interpretative phenomenological analysis |

| O'Connor et al. (138) | ADHD, AN, ASD, depression, developmental coordination disorder, non-epileptic seizures (Sym) | Australia, Canada, Denmark, Finland, Hong Kong, Israel, Norway, Puerto Rico, Sweden, UK, USA | Individual | 1,083 | 6–25 | NR | Systematic review | Thematic synthesis |

| Probst (139) | ADHD, AN, Anxiety, ASD, bipolar disorder, depression, dissociative identity disorder, dysthymia, PTSD (Sym) | USA | Individual | 30 | NR | 70 | Individual semi-structured interview | Narrative and thematic analysis |

| Schulze et al. (140) | Schizophrenia (Sym) | Switzerland | Individual | 31 | 23–66 | 33 | Individual interview | Inductive qualitative approach |

| BPD (Sym) | Individual | 50 | 18–56 | 81 | ||||

| Sun et al. (141) | Psychiatric diagnoses (Sym) | Hong Kong | Psychiatrists | 13 | NR | 15.4 | Focus group (n = 2) | Conventional content analysis |

| Perkins et al. (31) | Anxiety, AN BPD, bipolar disorder, depression, schizophrenia, personality disorder, psychosis (Sym) | Australia, Belarus, Brazil, Canada, Denmark, Israel, Latvia, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, UK, USA | Individual Caregiver Clinicians |

NR NR NR |

NR NR NR |

NR NR NR |

Systematic review | Thematic synthesis |

Conditions organised according to the international classification of diseases 11th edition; Scr, Condition identified through screening; Sym, Condition identified through symptoms; NR, Condition identification methods not reported; Mix, Multiple condition identification methods; GDM, Gestational diabetes mellitus; GERD, Gastro-oesophageal reflux disorder; PCOS, Polycystic ovary syndrome; MRKH, Mayer-rokitansky-kuster-hauser syndrome; HIV, Human immunodeficiency Virus; AIDS, Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; CFS, Chronic fatigue syndrome; ME, Myalgic encephalitis; MND, Motor neuron disease; HPV, Human papillomavirus; OCD, Obsessive compulsive disorder; AD, Alzheimer's disease; MCI, Mild cognitive impairment; ADHD, Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; ASD, Autism spectrum disorder; BPD, Borderline personality disorder; PTSD, Posttraumatic stress disorder; AN, Anorexia nervosa; GPs, General practitioners.

The 44 studies and five reviews includable in our review but not subjected to data extraction due to thematic saturation (final third), had a similar pattern to those used: 28 explored physical and 21 explored psychological diagnostic labels; most reported individual perspectives (76%, 37/49), significantly less reported multiple (12%, 6/49) or family/caregiver perspectives (10%, 5/49), and one (2%) reported healthcare professional or community perspectives. References of these studies are provided in References not subjected to qualitative analyses in Supplementary Material.

Thematic Synthesis

Qualitative synthesis of included studies identified five overarching themes: psychosocial impact (8 subthemes), support (6 subthemes), future planning, behaviour, and treatment expectations (2 subthemes each). Table 2 reports the number and proportion of records that supported each theme for each of the four perspectives while Table 3 reports the themes and subthemes supported by each included study. Due to the breadth of results, only themes which were supported by >25% of studies, are reported in the text, with themes supported by <25% of articles presented only in tables. Detailed descriptions of all themes and subthemes, with supporting quotes from the individual perspective, are reported in Table 4. Findings from the perspective of family/caregiver, healthcare professionals and community members are briefly reported in text, with details of these themes and supporting quotes reported in Supplementary Tables 1–3, respectively.

Table 2.

Proportion of records supporting each theme from the various perspectives.

| Major themes | Sub themes | Description | Perspective | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

I (n = 71) |

F (n = 19) |

H (n = 21) |

C (n = 3) |

|||

| Psychosocial impact | Negative psychological impact | Negative psychological impact of labelling | 51 (72%) |

10 (53%) |

7 (33%) |

0 |

| Positive psychological impact | Positive psychological impact of labelling | 43 (61%) |

5 (26%) |

4 (19%) |

0 | |

| Mixed psychological impact | Both positive and negative impact of labelling | 9 (13%) |

3 (16%) |

2 (10%) |

0 | |

| Psychological adaptation | Psychological adaptation to label and coping strategies/mechanisms | 37 (52%) |

8 (42%) |

1 (5%) |

0 | |

| Self-Identity | Changes to self-identity following provision of label (can be positive or negative) |

31 (44%) |

0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Social identity | Changes to social identity as a result of label, including becoming a member/mentor of a support group | 28 (39%) |

6 (32%) |

3 (14%) |

2 (67%) |

|

| Social stigma | Perceptions/assumptions of others toward individual labelled | 23 (32%) |

5 (26%) |

2 (10%) |

1 (33%) |

|

| Medicalisation | Asymptomatic label and understanding/perception of symptoms | 18 (25%) |

4 (21%) |

6 (29%) |

0 | |

| Support | Close relationships | Managing relationships and interactions; support required, offered, and accepted following labelling | 13 (18%) |

8 (42%) |

3 (14%) |

0 |

| Healthcare professionals interactions/relationships | Interactions with healthcare professionals; support provided; explanations | 32 (45%) |

5 (26%) |

13 (62%) |

0 | |

| Emotional support reduced/limited | Emotional support lost as a result of label or support absent but perceived to be required | 26 (37%) |

3 (16%) |

0 | 1 (33%) |

|

| Emotional support increased/maintained | Emotional support maintained or increased as a result of label | 19 (27%) |

5 (26%) |

2 (10%) |

1 (33%) |

|

| Disclosure | Fear and methods of disclosing label to others (friends/family/employers/colleagues) | 26 (37%) |

3 (16%) |

3 (14%) |

0 | |

| Secondary gain | Gains from label | 5 (7%) |

0 | 4 (19%) |

0 | |

| Future planning | Action | Forward planning and decision making as a result of label | 12 (17%) |

3 (16%) |

3 (14%) |

0 |

| Uncertainty | Questions regarding future health and lifestyle | 20 (28%) |

4 (21%) |

0 | 0 | |

| Behaviour | Beneficial behaviour modifications | Behaviour modification/changes as a result of label beneficial to overall health and well-being | 21 (30%) |

1 (5%) |

2 (10%) |

0 |

| Detrimental/unhelpful behaviour modifications | Behaviour modification/changes as a result of label unhelpful/restrictive to overall health and well-being | 23 (32%) |

9 (47%) |

3 (14%) |

1 (33%) |

|

| Treatment expectations | Positive treatment experiences | Perceptions of treatment/intervention (and outcomes) to be positive/beneficial |

20 (28%) |

1 (5%) |

3 (14%) |

0 |

| Negative treatment experiences | Perceptions of treatment/intervention (and outcomes) to be negative/unhelpful | 30 (42%) |

5 (26%) |

4 (19%) |

1 (33%) |

|

I, Individual perspective; F, Family/Caregiver perspective; H, Healthcare professional perspective; C, Community perspective; Shaded cells represent the numbers of studies that contribute to that theme, Unshaded cells, 0% of studies; Red cells, 1–24% of studies; Yellow cells, 25–49% of studies; Green cells, >50% of studies; one study could reference multiple themes and/or perspectives; Numbers and proportions of studies referenced in the results are calculated from included studies/reviews, with the final third of included studies not included in these tallies.

Table 3.

Themes and subthemes supported by each record.

| References (population) | Condition* (Scr, Sym, NR, Mix) | Psychosocial impact | Support | Future planning | Behaviour | Treatment expectations | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative psychological | Positive psychological | Mixed psychological | Psychological adaptation | Self-identity | Social identity | Social stigma | Medicalisation | Close relationships | Healthcare professionals |

Reduced limited |

Increased maintained | Disclosure | Secondary gain | Action | Uncertainty | Beneficial modifications | Detrimental modifications | Positive experiences | Negative experiences | ||

| Cardiovascular disease | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Asif et al. (46) (I) | Cardiac conditions (Scr) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Chronic kidney disease | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Daker-White et al. (47) (I) | Chronic kidney disease (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Diabetes | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Twohig et al. (48) (I) | Pre-diabetes (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Burch et al. (49) (H) | Pre-diabetes (NR) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||

| de Oliveira et al. (50) (I) | Diabetes (NR) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Due-Christensen et al. (51) (I) | Type 1 diabetes (NR) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Sato et al. (52) (I) | Type 1 diabetes (NR) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Jackson et al. (53) (F) | Type 1 diabetes (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Fharm et al. (54) (H) | Type 2 diabetes (NR) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Kaptein et al. (55) (I) | GDM (Scr) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Singh et al. (56) (I) | GDM (Scr) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Female reproduction | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Copp et al. (57) (I) | PCOS (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Copp et al. (58) (H) | PCOS (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Newton et al. (59) (I) | Pelvic inflammatory disease (NR) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| O'Brien et al. (60) (I) | Anti-Mullerian hormone testing (Scr) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Patterson et al. (61) (I) | MRKH (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Harris et al. (62) (I) | Pre-eclampsia (Scr) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Genome/Chromosome | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Delaporte (63) (I, H) | Facioscapulohumeral dystrophy (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Houdayer et al. (64) (F, H) | Chromosomal abnormalities (Scr) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| HIV/AIDS | |||||||||||||||||||||

| McGrath et al. (65) (I, F) | AIDS (NR) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Anderson et al. (66) (I) | HIV (NR) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Freeman (67) (I) | HIV (NR) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Kako et al. (68) (I) | HIV (NR) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Kako et al. (69) (I) | HIV (NR) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Stevens et al. (70) (I) | HIV (NR) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Firn and Norman (71) (I, H) | HIV/AIDS (NR) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Immune system | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Hale et al. (72) (I) | Systemic lupus erythematosus (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Infectious/Parasitic | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Almeida et al. (73) (I) | Leprosy (NR) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Silveira et al. (74) (I) | Leprosy (NR) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Zuniga et al. (75) (I) | Tuberculosis (NR) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Dodor et al. (76) (I, C) | Tuberculosis (NR) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Metabolic | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Bouwman et al. (77) (I) | Fabry disease (NR) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Musculoskeletal | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Erskine et al. (78) (I) | Psoriatic arthritis (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Martindale and Goodacre (79) (I) | Axial spondyloartritis (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Hopayian and Notley (80) (I) | Back pain and sciatica (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Barker et al. (81) (I) | Osteoporosis (Mix) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Hansen et al. (82) (I) | Osteoporosis (NR) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Weston et al. (83) (I) | Osteoporosis (Scr) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Boulton (84) (I) | Fibromyalgia (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Madden Sim (85) (I) | Fibromyalgia (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Mengshoel et al. (86) (I) | Fibromyalgia (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Raymond and Brown (87) (I) | Fibromyalgia (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Sim Madden y (88) (I) | Fibromyalgia (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Undeland and Malterud (89) (I) | Fibromyalgia (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Nervous system | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Chew-Graham et al. (90) and Zarotti et al. (94) (H) | CFS/ME (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Hannon et al. (91) (I, F, H) | CFS/ME (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| De Silva et al. (92) (I, F, H, C) | CFS (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Johnston et al. (93) (I) | MND (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Zarotti et al. (94) (H) | MND (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Johnson (95) (I) | Multiple sclerosis (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Thompson et al. (96) (I) | Non-epileptic seizures (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Wyatt et al. (97) (I, F) | Non-epileptic attack disorder (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Neurological | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Nochi (98) (I) | Traumatic brain injury (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Daker-White et al. (99) (I, F) | Progressive ataxias (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Newborn/Foetal | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Hallberg et al. (100) (F) | 22q11 Deletion syndrome (Scr) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Johnson et al. (101) (F) | Cystic fibrosis (Scr) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Dahlen et al. (102) (H) | GORD/GERD (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sleep-Wake disorder | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Zarhin (103) (I) | Obstructive sleep apnoea (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Sexually transmitted | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Mills et al. (104) (I) | Chlamydia trachomatis (Scr) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Rodriguez et al. (105) (I) | HPV (NR) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Multiple physical diagnoses | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Kralik et al. (106) (I) | Chronic illness, diabetes (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Bipolar disorder | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Fernandes et al. (107) (I) | Bipolar (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Proudfoot et al. (108) (I) | Bipolar (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Depression | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Wisdom and Green (109) (I) | Depression (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Chew-Graham et al. (110) (H) | Depression (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Neurocognitive | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Beard and Fox (111) (I) | AD; MCI (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Bamford et al. (112) (I, F, H) | Dementia (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Bunn et al. (113) (I, F) | Dementia (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Robinson et al. (114) (I, F) | AD; Dementia (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Ducharme et al. (115) (F) | AD (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Abe et al. (116) (H) | Dementia (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Phillips et al. (117) (H) | Dementia (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Walmsley and McCormack (118) (H) | Dementia (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Werner and Doron (119) (H, C) | AD (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Neurodevelopmental | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Carr-Fanning and Mc Guckin (120) (I, F) | ADHD (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Mogensen and Mason (121) (I) | ASD (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Fleischmann (122) (F) | ASD (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Hildalgo et al. (123) (F) | ASD (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Loukisas and Papoudi (124) (F) | ASD (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Selman et al. (125) (F) | ASD (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Smith et al. (126) (I, F) | ASD (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Obsessive compulsive disorder | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Pedley et al. (127) (F) | OCD (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Peri/Postnatal anxiety and/or depression | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Ford et al. (128) (H) | Perinatal anxiety and depression (Scr) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Chew-Graham et al. (129) (H) | Postnatal depression (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Personality disorder | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Horn et al. (130) (I) | BPD (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Lester et al. (131) (I) | BPD (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Nehls (132) (I) | BPD (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Schizophrenia/Psychotic disorder | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Thomas et al. (133) (I) | Schizophrenia (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Welsh and Tiffin (134) (I) | At-Risk psychosis (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Welsh and Tiffin (135) (H) | At-Risk mental state (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Multiple psychological diagnoses | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Hayne (136) (I) | Mental illness (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| McCormack and Thomson (137) (I) | Depression, PTSD (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| O'Connor et al. (138) (I) | ADHD, AN, ASD, depression, developmental coordination disorder, non-epileptic seizures (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Probst (139) (I) | ADHD, AN, anxiety, ASD, bipolar disorder, depression, dissociative identity disorder, dysthymia, PTSD (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Schulze et al. (140) (I) | Schizophrenia, BPD (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Sun et al. (141) (H) | Psychiatric diagnoses (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Perkins et al. (31) (I, F, H) | Anxiety, AN, bipolar disorder, BPD, depression, personality disorder, psychosis, schizophrenia (Sym) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Totals | 67 | 49 | 14 | 45 | 31 | 38 | 30 | 28 | 24 | 47 | 30 | 26 | 31 | 9 | 19 | 24 | 24 | 34 | 25 | 41 | |

I, Individual perspective; F, Family/Caregiver perspective; H, Healthcare professional perspective; C, Community perspective; Cells with “✓” indicate theme explicitly mentioned in the study; Blank cells indicate theme not explicitly mentioned in the study; one study could reference multiple themes and/or perspectives; *Conditions organised according to the International Classification of Diseases 11th edition; Scr, Condition identified through screening; Sym, Condition identified through symptoms; NR, Condition identification methods not reported; Mix, Multiple condition identification methods; GDM, Gestational diabetes mellitus; GERD, Gastro-oesophageal reflux disorder; PCOS, Polycystic ovary syndrome; MRKH, Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome; HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus; AIDS, Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; CFS, Chronic fatigue syndrome; ME, Myalgic encephalitis; MND, Motor neuron disease; HPV, Human papillomavirus; OCD, Obsessive compulsive disorder; AD, Alzheimer's disease; MCI, Mild cognitive impairment; ADHD, Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; ASD, Autism spectrum disorder; BPD, Borderline personality disorder; PTSD, Posttraumatic stress disorder; AN, Anorexia nervosa.

Table 4.

Major and subthemes arising as consequences for the individual.

| Theme, subtheme, description | Exemplary comment |

|---|---|

| Psychosocial impact | |

| Negative psychological impact Negative psychological impact of labelling |

For some, being seen through the lens of their diagnosis meant being deflated, “robbed of flesh,” crudely translated into an incomplete symbolic language that “doesn't capture my reality, doesn't see me in my full human complexity, doesn't tell anything substantive about what it's like to actually be me.” As one person said, “the diagnosis is like looking at a map of the city but it isn't the city itself” (139) That number doesn't sum me up, it doesn't tell the whole storey. I felt offended when I saw it. I didn't feel understood–I felt reduced, diminished. There's nothing in the diagnosis that was really at the heart with what I felt I was afflicted with (139) |

| Positive psychological impact Positive psychological impact of labelling |

Patients of [Black and Minority Ethnicity] origin described the importance of being believed and taken seriously by their healthcare professionals, and they described how difficult it had been to convince the GPs of their symptoms: “That is the hardest thing, that is what I find the hardest, even if they didn't find they can cure me, but, just to believe me and have understanding of me, that's all I want” (92) The diagnosis was used as retaliation against the scepticism encountered within participants' interactions with professionals and the public, and reduced the self-doubt which had been fostered by experiences of being disbelieved. “Now we've got a label you can turn around and say that's what it is” (97) |

| Mixed psychological impact Both positive and negative impact of labelling |

Some women shared that they felt relief mixed with fear when a diagnosis was made because they had experienced symptoms that had been very disruptive to their life, and ‘getting diagnosed’ had been a frightening process: Upon diagnosis I actually felt relief mixed with fear. Relieved because the problem had a name, fearful because there is no cure and no known cause (106) …she described the conflicting emotions of feeling a sense of relief tempered by the knowledge that this was a long-term condition: ‘But it’s a double-edged sword, really, because getting the diagnosis is helpful and you know where you stand, and when you talk to people they don't think you are swinging the lead or you are trying to get out of something… but then the flip-side is, oh God, this is me for the rest of my life; it's not going to go away, it's not going to go anywhere' (79) |

| Psychological adaptation Psychological adaptation to label and coping strategies/mechanisms |

…[diagnosis] eliminated a natural mechanism of coping with stress. This compounded emotional stress related to their diagnosis: “What I would usually do in a situation like that was run…I was extremely stressed out and because the way I cope with stress is to run and I couldn't run” (46) Others focused on strategies for symptom management, including “relaxation,” “sleep,” setting “limitations,” “exercise,” and maintaining a “positive attitude” (107) |

| Self-Identity Changes to self-identity following provision of label (can be positive or negative) |

Reconstructing a view of self. This construct referred to how, for many adults in these studies, the diagnosis seemed to change their personal identity which in turn influenced the way they engaged with others and their future aspirations and goals (51) Their perception of themselves had changed so dramatically that, even in a state of physical health after having received curative treatments, they continued to perceive themselves as living with illness (106) |

| Social identity Changes to social identity as a result of label, including becoming a member/mentor of a support group |

Many participants felt that being involved in research allowed them to be proactive, to help advance science, to aid future generations, and to possibly even receive personal benefits (111) Others who had gone public viewed their public acknowledgement of positive [diagnosis]…as a means of reaching others in the community to educate them about [diagnosis] and encourage them to be tested. To these women, disclosure was done out of a sense of duty. They felt they were ambassadors to their communities, even though they risked ridicule and rejection (68) |

| Social stigma Perceptions/assumptions of others toward individual labelled |

They felt disrespected by people who had heard of the diagnosis but still remarked that they did not look ill enough (89) They experienced stigma because of the way the label changed the way other people saw them (133) Besides the image of abnormality, some informants reported that they are considered to be as powerless as children or sick patients (98) |

| Medicalisation Asymptomatic label and understanding/perception of symptoms |

“Normal” vs. “Abnormal” memory loss. Although all respondents acknowledged [symptoms], they had difficulty balancing the “everyday nature of [symptoms]” with the new “reality” that rendered what was previously considered normal, a symptom of disease. Diagnosed individuals were forced to incorporate this tension into their new identities as people living with [symptoms] that was simultaneously the same as past experiences and yet decidedly different (111) The invisible disease. An underlying theme that emerged for many women was the struggle to accept a diagnosis when they felt healthy and had no visible signs of disease. This meant they felt that they had to believe an abstract diagnosis, or they interpreted it as incorrect or insignificant. The absence of visual evidence created mixed reactions to the diagnosis among the women (83) |

| Support | |

| Close relationships Managing relationships and interactions; support required, offered, and accepted following labelling |

Participants also reported a loss of control when their family, friends, or work colleagues engaged in symptom surveillance: I have actually had friends say, “Are you symptomatic? You are talking a lot. Maybe you have got some [diagnosis]?” (107)

My boss was really worried that I might have been becoming unwell and, unfortunately, she contacted my psychiatrist before I got there. That was such a breach of confidentiality and just triggered a whole lot of stuff for me.…My boss had said I was wearing different clothes, so it is this fear of, I cannot look different, I cannot wear different things, I cannot have a lot of money or act in certain ways (107) Loving and caring relationships were felt integral to health and quality of life. Some had become isolated at home or dependent on family and friends for social contact (81) |

| Healthcare professionals interactions/relationships Interactions with healthcare professionals; support provided; explanations |

Some informants felt better understood by health care professionals than by friends or family, whereas others felt misunderstood by the medical profession and society in general. Some informants felt that they were looked upon as being an uninteresting patient, and that once no cure was evident professionals lost patience with them and seemed uninterested and unbelieving (88) They tended to view their health care provider as responsible for “fixing” the problem and did not take responsibility for its remedy. They tended to become frustrated with providers who were not as available as they would like (109) |

| Emotional support reduced/limited Emotional support lost as a result of labelling; or support absent but perceived to be required |

Others were forced out of their communities; they lost some of their friends and family members avoided direct contact with them. (75) Those patients who had experienced a cancelation of their engagement or a divorce because of the disease felt burdened by a handicap that makes them different from others. (52) |

| Emotional support increased/maintained Emotional support maintained or increased as a result of labelling |

Participants thought that their partner, family, friends, health professionals, and support groups provided “advice” and “safety.” For one participant, the support of her husband gave her strength and made her feel “empowered.” Participants also commented on the practical and emotional support they received from friends. For example, one participant stated, “They used to come and do the washing for me, bring me homemade bread, and look after the family” (107) Participants consistently described the importance of relationships in terms of hope, recovery and survival. People described how the most significant support they received was from people whom they could trust and who could, as Carol said, “treat you as a person, rather than a diagnosis” (130) |

| Disclosure Fear and methods of disclosing label to others (friends/family/employers/colleagues) |

In general, sharing the diagnosis with friends and family was not a problem, though several people expressed anger that they did not have control over the manner, timing, or extent to which this information was shared with employers or other health care providers (139) Other participants discussed the fear they held of losing support people if they told them about their illness. There are others I would like to share things with, but I don't want to lose anyone else at the present time and it's a risk I'm not willing to take (108) |

| Secondary gain Gains from label |

Knowing, naming or labelling one's symptoms was also articulated as an important issue in more practical matters such as obtaining benefits or insurance payouts (99) He interpreted this difference positively in terms of the allowances that were sometimes made for him, explaining: ‘I know that if I wasn’t [diagnosis] my Mum wouldn't let me get away with much stuff' and ‘I think I get a bit of easier work’ at school. So although Dylan indicated that the diagnosis was not significant for his self-identity, he recognised that it had a meaning and a function–in perhaps reducing some of the typical school expectations and the way others saw him (121) |

| Future planning | |

| Action Forward planning and decision making as a result of label |

Family planning Some women discussed feeling pressured to have children earlier than they would have liked because they were concerned that if they left it later they would be unable to conceive. A few women did have children earlier than preferred, which was seen to impact on their careers ‘Yes, that did put the career on hold. I focused on having the children early… I felt with the diagnosis, yeah, you're always thinking about, you know, that fertility side of it. So, yeah, it does affect your decisions’ (57) …felt that an “early” diagnosis made it possible to anticipate future [diagnosis]-related problems, which allowed them to make choices in life “So you can make conscious decisions: What will I do in life?(…) I am a pharmacist now, so that is not so hard, but what if you have to do something else?(…) If it involves heavy physical activity, you will not be able to do it at a certain point in time. So that is why I feel it is of interest to know” (77) |

| Uncertainty Forward planning and decision making as a result of label |

…patients indicated that a disadvantage of an early diagnosis was the loss of carefree life and increased worrying about the future. “Yes, because I have two boys (…) and because I was aware of the medical history in the family, and it's like, well, this is what's in store. My uncle had a couple of kidney transplants and he eventually died of heart failure (…) and then hearing the storeys about my grandmother's brothers–three of them I believe, dying at 35 years of age. Okay, we're talking the turn of the last century of course, but it was disheartening to hear, all the same, and although knowledge of the disease has improved, you still think if you have to go through what my uncle went through, that's not easy” (77) Fear of what is to come. This describes deep concern with what the future might bring. Hope hinged on success of treatment or being able to successfully accommodate manifestations of [diagnosis] and was countered by fear of unpredictable consequences. Participants described fears of losing mobility, of being wheelchair bound, of being dependent on others and of further fractures, falls and deformity (81) |

| Behaviour | |

| Beneficial behaviour modifications Behaviour modification/changes as a result of label beneficial to overall health and well-being |

Some women acknowledged that developing [diagnosis] was the push they needed to begin adopting healthier behaviour patterns. One woman articulated that diabetes was the “ammunition” her partner needed to encourage her to change her dietary habits and avoid [diagnosis] in the future (55) Although the women did not allow the diagnosis to intrude on their lives, they described themselves as being more sensible than they were previously. These minor adaptations allowed them to manage their increased [symptom] risk but still live as normal. They described taking extra precautions against falling, for example, when it was icy, and they asked for aids such as handrails: I'm a little more careful in the garden, where I put my tools, where I put my weed bin so I don't fall over it, things like that. We've got quite a large patio with quite a number of steps. I've had a handrail put there and I'm more careful coming down them, whereas I wasn't before…I'm just a little more alert to the dangers if you did fall (83) |

| Detrimental/unhelpful behaviour modifications Behaviour modification/changes as a result of label unhelpful/restrictive to overall health and well-being |

Another participant thought that she could not be her “usual jolly self” because she feared others would perceive her as being symptomatic of [diagnosis]. Consequently, she thought she had become more “serious” and “less spontaneous,” and she “[thought] twice” about her actions (107) …drug and alcohol use escalated after [diagnosis]. The substance misuse problems they may have had before “really took off” when they found out they had [diagnosis]: When I went in there and they told me that I was positive, I broke down. I just started drinking and drugging and popping pills. I was devastated. I started severely abusing crack cocaine because it kept the feelings away (70) |

| Along with deep sadness came inactivity, lack of motivation, loss of vigour and initiative, and isolation from family and friends: I went through depression. I pushed myself away from the family. I had nothing to do with my kids. My sister had to take care of my kids. I was always in my room locked up, crying. (70) | |

| Treatment expectations | |

| Positive treatment experiences Perceptions of treatment/intervention (and outcomes) to be positive/beneficial |

Participants spoke to healing gained from a diagnosis which made illness evident and treatment possible, thus, reinstating them to life (136) Naming experience brought knowledge that there were treatments, which in turn brought hope and a sense of control (139) |

| Negative treatment experiences Perceptions of treatment/intervention (and outcomes) to be negative/unhelpful |

Many participants in our sample were troubled by their medication. Significant concerns were expressed about the negative side-effects and the impact of medication on other areas of their lives, such as blunting their creativity, reducing their energy levels, increasing their weight. Some participants also expressed frustration associated with trialling different medications to find the right combination (108) There was a consistent feeling that diagnosis often led to withdrawal of services, that once this diagnostic decision was made then support was withdrawn (130) |

Individual Perspective

Psychosocial Impact

Psychosocial impact was identified as the most prevalent theme impacting individuals following being labelled with a diagnostic label. Within this major theme, eight subthemes emerged. Negative psychological impact, positive psychological impact, and psychological adaptation were developed with over 50% of studies preferencing the individual's perspective. Subthemes developed with <50% of included articles were self-identity (44%), social identity (39%), social stigma (32%), medicalisation (25%), and mixed psychological impact (13%) (see Table 2 for overview and Table 4 for details).

Negative and Positive Psychological Impact

Both positive and negative consequences of diagnostic labelling to individuals were reported. Almost 72% of studies describing consequences of labelling from the individual's perspective reported negative psychological consequences including resistance, shock, anxiety, confusion, bereavement, abandonment, fear, sadness, and anger frequently reported (46, 50–52, 56, 57, 59–63, 65, 66, 68–70, 74, 75, 81, 82, 85, 88, 92, 95–97, 99, 103–106, 108, 112, 113, 126, 136, 138, 139). Conversely, 61% of studies reported a positive psychological impact of being provided with a diagnostic label. For example, many individuals reported that receiving a diagnostic label produced feelings of relief, validation, legitimisation, and empowerment (31, 46, 57, 60, 66, 72, 77, 79, 80, 83, 84, 86–89, 91, 92, 96, 97, 99, 105–109, 111, 113, 120, 121, 126, 133, 134, 136, 139). Other studies reported individuals described diagnostic labels as providing hope and removing uncertainty (93, 95, 96, 112, 121, 130, 134, 136, 137), facilitating communication with others (98, 130), and increasing self-understanding (97, 131, 138).

Psychological Adaptation

Upon receipt of a diagnostic label, 52% of included studies from an individual's perspective reported a need to change their cognitions and emotions. Included studies reported individuals described adaptive (e.g., using humour) and maladaptive (e.g., suicidality) coping mechanisms (46, 48, 50, 57, 61, 67–69, 71, 74, 82, 85, 88, 98, 105, 107–109, 111, 112, 114, 136, 138, 139), adapting to new condition-specific knowledge (62, 79, 87, 88, 121), rejecting negative perceptions (50, 51, 70, 104, 138), and accentuating positive elements of the condition (51, 52, 61, 86, 105, 111). These adaptations were reported to be centred around living fulfilling lives post diagnostic labelling (70, 83, 88, 107).

Changes to self-identity was reported by individuals in 44% of included studies. These studies reported individuals experienced a disruption to their perception of self and previously held identities (46, 51, 57, 59, 61, 78, 81, 103, 104, 107, 113, 136, 137, 139). Some of these changes were viewed constructively, including reported perceptions of empowerment, transformation, and self-reinforcement (51, 67, 83, 88, 107, 109, 121, 137–139). Others, however, reported negative impacts such as enforced separation from those who did not have a label, and perceptions of themselves as unwell and less competent (31, 51, 52, 60, 63, 76, 88, 105–107, 109, 111–113, 121, 136, 138, 139).

Changes to social identity and experiences of social stigma were reported in 39% and 32% of included studies, respectively. Within newly developed social identities, mentorship and support groups were frequently reported as beneficial (31, 46, 51, 56, 57, 68, 69, 81, 85–88, 97, 107, 109, 111, 113, 134, 138, 139), although sometimes not (61, 85, 107, 113). In some studies, individuals perceived increased stigmatisation, including judgement, bullying, powerlessness, isolation, and discrimination, from families, friends, and society (31, 51, 61, 63, 74, 78, 85, 98, 105, 107, 108, 121, 133, 137, 138), and healthcare professionals (88, 133). Few studies reported individuals perceived their diagnostic label negatively impacted employment (71, 76, 138).

A quarter of the studies reporting individual perspectives, referenced the concept of medicalisation at various points along the diagnostic labelling pathway. For example, at the point of diagnostic labelling, some individuals described the diagnostic label as medicalising their asymptomatic diagnosis (71, 76, 138), others struggled with differentiating normal and abnormal experiences (99, 111), while others attributed all symptoms and behaviours to the provided diagnostic label (85, 86, 121, 133).

Support

Within this major theme, six subthemes emerged. The most frequently reported was individuals' interactions with healthcare professionals in 45% of included studies. Fewer studies reported on disclosure (37%), or changes in the perceived or actual support received following receipt of a diagnostic label with loss of support reported in 37% of studies and increased support reported in 27% of studies. Close relationships and secondary gains were less prevalent themes reported in <25% of included studies.

Healthcare professional interactions were reported to occur along a spectrum from individuals feeling adequately supported and reassured (31, 46, 51, 59, 60, 87, 93, 95, 96, 131) through to individuals feeling dismissed and not listened to (31, 59, 61, 72, 78, 80, 84–86, 89, 91, 93, 95, 97, 98, 104–107, 120). Perception of interactions with healthcare professionals often reflected the individual's understanding of the healthcare professionals': role [e.g., responsible for correcting the diagnosis, open discussion between professional and individual (47, 109)]; the perceived level of skill, knowledge and competency (95, 97); and communication skills (47, 91, 112).

Individuals disclosing their diagnostic label to others was a dilemma reported in 37% of included studies. Concerns about whether, when and to whom to disclose where frequently reported (46, 47, 57, 61, 104, 105, 132, 134, 139, 140). Reasons for hesitation included worry, shame, and embarrassment (65, 81), fear of rejection or loss of support (52, 61, 65, 68, 74, 105, 108), anticipation of stigma (65, 68, 86, 88, 89, 105, 121); loss of pre-diagnostic labelled self (82, 107, 113, 138), and fear of losing employment (74, 86, 138). Disclosure was often reported to occur out of a “sense of obligation” (68, 91, 126, 134, 138).

As a result of the diagnostic label, individuals in the included studies reported similar, increased, and decreased emotional support. Some individuals reported others became more emotionally and physically distant, either overtly or covertly, and more stigmatising (48, 51, 56, 69, 71, 73–76, 81, 88, 89, 105, 107, 108, 133, 134, 136, 138) following label disclosure, some experienced breakdowns of romantic relationships and marriages (52, 66, 105, 107), and some perceived a reduction in support from healthcare professionals following diagnostic labelling (46, 56, 86, 106, 132, 133, 136, 139). In contrast, others indicated no change or an increase in support from family, friends, and communities, reporting acceptance, tolerance, and strengthened relationships (31, 46, 48, 50, 55, 57, 68, 69, 73, 74, 86, 91, 105, 107, 113, 130, 134, 138, 140).

Future Planning

Within this major theme, two subthemes emerged which were related to the certainty of future aspirations and planning: uncertainty (28%) and action (imminent need or ability to respond, 17%).

Individuals who reported uncertainty about their future health and lifestyles reported fear, worry, stress, anxiety, and passivity around their futures (57, 69, 88, 97), with these emotions related to changes to life-plans (66, 69, 77, 108, 138), including reproductive abilities (57, 59, 60, 105), potential complications due to the diagnostic label and/or its treatment (52, 57, 62, 63, 69, 81), and unclear disease progressions (31, 77, 78, 85, 87, 93).

Behaviour Modification

Behaviour modification was reported as either beneficial to greater overall health and well-being (reported in 30% of included studies) or detrimental and perpetuated or exacerbated condition difficulties (reported in 32%).

Beneficial behaviour modifications included greater ownership of health (51, 82, 109, 136) and positive changes to physical activity practises, dietary choices, self-awareness, and risk management (48, 50, 51, 55–57, 59, 62, 67, 81–83, 87, 88, 104, 105, 107, 109, 113, 136, 138). While detrimental behaviour modifications were reported as activity restriction (46, 51, 66, 88, 105, 107, 112, 133), reduction in employment and educational opportunities (63, 81, 107, 133, 138), and withdrawal from social interactions and relationships (51, 61, 66, 74, 75, 81, 95, 96, 105). Other individuals indicated increased hypervigilance (51, 57, 75, 112) and additional disruptive and risk-taking behaviours (50, 57, 70, 82, 98) and suicide attempts (70, 107, 138).

Following receipt of a diagnostic label, treatment expectations were reported by some individuals as both positive (reported in 28% of included studies) and negative treatment experiences (42%). Some individuals reported condition labelling facilitated access to treatment, monitoring, and support (31, 55, 57, 59, 62, 69, 86, 106, 112, 133, 136–138), which produced hope, empowerment, and perceived control (31, 80, 83, 88, 97, 105, 139) and contributed to positive treatment experiences. Contributing to negative treatment experiences, however, others indicated the labels failed to guide treatment (31, 57, 59, 77, 80, 86, 89, 95, 105, 114, 132), and that treatments were ineffective, difficult to sustain, and had detrimental effects (46, 50, 52, 55, 56, 77, 80–83, 88, 91, 105, 107–109, 113, 120, 131, 138); and lack of control over (72, 107, 140), or rejection from services (31, 95, 130–132).

Perspectives of Family/Caregivers, Healthcare Professionals, and Community Members

Fewer studies reported consequences of a diagnostic label from the perspectives of family/caregivers (n = 19 studies), healthcare professionals (n = 21 studies) and community perspectives (n = 3 studies; Table 2 for overview and Supplementary Tables 1–3, respectively, for details). Family/caregivers primarily reported negative psychological impacts of diagnostic labelling (53%). Other subthemes comprised evidence from <50% of included articles, including detrimental behaviour modifications (47%), psychological adaptation and close relationships (42%), social identity (32%), and positive psychological impact, social stigma, healthcare professional interactions/relationships, increase/maintained emotional support, and negative treatment experiences (all 26%).

Healthcare professionals predominantly reported on their interactions/relationships (62%) with patients following diagnostic labelling, the potential negative psychological impact (33%) a diagnostic label would have and how this could lead to medicalisation (29%) of symptoms.

Although the community perspective was least frequently reported, two-thirds of the included studies (67%) reported the diagnostic label had an impact on the social identity of the individual labelled. Single studies from the community perspective reported themes of social identity, social stigma, increased/maintained emotional support, reduced/limited emotional support, detrimental/unhelpful behaviour modifications, and negative treatment experiences (all 33%). No studies from the community perspective supported the remaining 14 subthemes.

Discussion

The findings from our systematic scoping review identified a diverse range of consequences of being labelled with a diagnostic label that vary depending on the perspective. Five primary themes emerged: psychosocial impact, support, future planning, behaviour, and treatment expectations, with each theme having multiple subthemes. All five primary themes were reported from each perspective: individual; family/caregiver; healthcare professional; or community member. Within each primary theme there were examples of both positive and negative impacts of the diagnostic label.

However, the developed framework suggests that receiving a diagnostic label is not solely beneficial. For example, of the studies in our review which reported a psychosocial consequence of a diagnostic label, 60% of these reported negative psychological impacts, compared with 46% that reported positive psychological impacts. The results of this review also suggest many individuals experience changes in their relationships with healthcare providers (and the latter agreed), lost emotional support, and experienced a mix of both beneficial and detrimental changes in behaviour due to the diagnostic label.

Strengths and Limitations