Abstract

An awakening to systemic anti-Black racism, anti-Indigenous racism, and harmful colonial structures in the context of a pandemic has made health inequities and injustices impossible to ignore, and is driving healthcare organizations to establish and strengthen approaches to inclusion, diversity, equity, and accessibility (IDEA). Health research and care organizations, which are shaping the future of healthcare, have a responsibility to make IDEA central to their missions. Many organizations are taking concrete action critically important to embedding IDEA principles, but durable change will not be achieved until IDEA becomes a core leadership competency. Drawing from the literature and consultation with individuals recognized for excellence in IDEA-informed leadership, this study will help Canadian healthcare and health research leaders—particularly those without lived experience—understand what it means to embed IDEA within traditional leadership competencies and propose opportunities to achieve durable change by rethinking governance, mentorship, and performance management through an IDEA lens.

Introduction

Research-intensive and healthcare organizations are generating the knowledge and training for the professionals shaping the future of healthcare. Recognizing that anti-Black and anti-Indigenous racism are insufficiently addressed within health research1,2 and create barriers to equitable health outcomes for Indigenous peoples3,4 and racialized individuals in Canada,5,6 research-intensive and healthcare organizations have a unique, urgent, and challenging responsibility to make inclusion, diversity, equity, and accessibility (IDEA; Box 1) central to their organizational missions and cultures. The COVID-19 pandemic—which has made these pervasive health inequities and injustices impossible to ignore—has underscored the critical importance of addressing and embedding IDEA in healthcare and health research as one way to begin to address anti-Black racism, anti-Indigenous racism, and dismantle systemic colonial structures.

Box 1. Defining inclusion, diversity, equity, and accessibility (IDEA)7,8

Inclusion. Creating environments in which any individual or group can be and feel welcomed, respected, represented, supported, and valued to fully participate.

Diversity. Examining the makeup of an institution to ensure that people from different backgrounds and with multiple perspectives are represented.

Equity. The fair and just treatment of all members of a community.

Accessibility. The commitment for everyone along the continuum of human ability and experience to be included in all programs and activities.

Although many organizations are taking concrete actions to address racism in the workplace, there is clearly more work to be done to create diverse and inclusive workplaces and build teams—particularly at the senior leadership level—that represent the broader Canadian demographic.9,10 By infusing traditional leadership competencies with the values, principles, and commitments of IDEA, efforts to address racism and foster inclusion can be strengthened, helping organizations transform and achieve lasting cultural change. Drawing from the literature and consultation with individuals recognized for excellence in IDEA-informed leadership, this study will (i) help Canadian healthcare and health research leaders—particularly those without lived experience—understand what it means to embed IDEA within traditional leadership competencies and (ii) propose opportunities to achieve durable change by rethinking governance, mentorship, and performance management through an IDEA lens. When leaders are empowered and able to integrate IDEA as a leadership competency, the knowledge, skills, and behaviours intrinsic to superior leadership performance are enhanced and, as a result, health research and healthcare organizations will attract and retain top talent, enhance innovation, improve care, and increase productivity.

Inclusion, diversity, equity, and accessibility can elevate leadership competencies

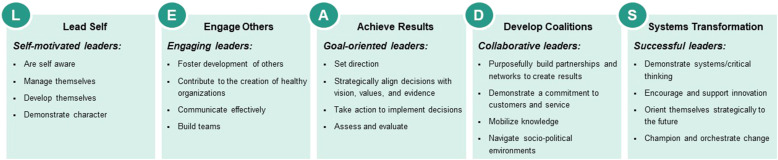

Many scholars11-13 and professional societies and associations14-16 provide recommendations, analysis, and frameworks that help define leadership competencies in healthcare, health research, and beyond. Notably, the Canadian College of Health Leaders (CCHL) and the Canadian Certified Physician Executive champion the LEADS in a Caring Environment (LEADS) framework as a tool for fostering the development of future health leaders in Canada.15,16 The LEADS framework 15 is centred around five pillars: (i) lead self; (ii) engage others; (iii) achieve results; (iv) develop coalitions; and (v) systems transformation (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of the LEADS in a caring environment framework.

Taken as a whole, most leadership frameworks,11-15 including the LEADS framework, align on five competencies: (i) uphold justice, fairness, and ethical standards; (ii) exhibit and support flexibility, open-mindedness, and ability to manage change; (iii) enable and uplift talent; (iv) develop and model a high standard of excellence; and (v) demonstrate accountability for results. Each of these competencies is indispensable to healthcare and research leadership—and each can be strengthened and improved when infused with the principles of IDEA. Indeed, CCHL has developed equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) toolkits outlining promising EDI practices mapped to each of the four pillars of the LEADS framework. 17 While leaders must explore opportunities to lead in a way that represents and reflects the cultures of the communities they serve, there are some common ways that IDEA can strengthen core leadership competencies (Table 1), many of which are reinforced by the LEADS EDI toolkit and the Centre for Global Inclusion’s Global Diversity and Inclusion Benchmarks. 18

Table 1.

Strengthening common leadership competencies in health research and healthcare settings by integrating IDEA.

| Leadership competency | Integrating IDEA |

|---|---|

| Uphold justice, fairness, and ethical standards and reflect the values of the organization in decision-making that shapes culture, strategy, and operations | An inclusive leader will share their personal IDEA beliefs, create a safe space for others to do the same, foster a common understanding of IDEA within their organization, and approach decision-making in a way that demonstrates that IDEA is a core value |

| Exhibit and support flexibility, open-mindedness and ability to manage change, anticipating, and responding to internal and external dynamics that can impact the organization | Leaders must demonstrate an ability to understand and incorporate diverse points of view, overcome resistance, and, given the dynamic nature of current understanding of IDEA and the systems and structures that oppose progress, to identify, adapt, and implement emerging best practices. Where leaders do not have the knowledge or lived experience, there is an expectation that they build a deeper understanding and recalibrate what is required to lead change |

| Enable and uplift talent by creating conditions that allow people (researchers and clinicians) to maximize their potential, to contribute to the organization and their teams, and to be as innovative, creative, and collaborative as possible | Inclusive leaders will help individuals and teams build their IDEA skill sets in the context of research, care, management, and collaboration. They will also advocate for marginalized groups and design and implement recruitment, retention, and professional development initiatives that create pathways for diverse candidates to succeed |

| Develop and model a high standard of excellence in scientific and care delivery settings | Prevailing standards of excellence and merit are not universal and can propagate inequity and injustice. There is an opportunity to reduce bias and barriers by expanding and enriching excellence in research and care and diversifying metrics of success |

| Demonstrate accountability for results to the funders supporting research (who are often public sector) and to the beneficiaries of innovation and care (patients, humankind) | Inclusive leaders will define and monitor near- and long-term goals related to IDEA, clarify roles and responsibilities for the activities/initiatives that advance IDEA goals, communicate progress, take responsibility for failures, and share success |

How do IDEA-informed leadership competencies become transformational in healthcare and research settings?

A set of behaviours, policies, and approaches—many of which are broadly applicable to diverse organizations, sectors, and disciplines—are emerging and setting a standard for IDEA-infused leadership (See Box 2).

Box 2. Practices and initiatives to embed IDEA in healthcare and research organizations

Board engagement. Activate a meaningful and authentic commitment to IDEA at the board level through, for example, development of a subcommittee to model this competency and set an organizational expectation.

Strategic planning. Measure and assess the current state of IDEA in an organization as a starting point. Engage people with lived experience to determine needs and embed IDEA in organizational strategy.

Enabling implementation and impact. Assign an accountable party at the executive and implementation levels. Develop, monitor, and report on IDEA metrics. Create a system of incentives and recognition that links some compensation/bonus and/or professional advancement to IDEA-based metrics, performance, and initiatives.

Training and education. Bring focus to an enlightened version of unconscious bias training; share information to build a clear understanding of IDEA best practices as well as internal policies/practices; and leverage participatory training tools (e.g. case studies and role playing) to enhance engagement and learning. Engage potential participants to understand their IDEA training objectives and build training and education programs around those goals to help ensure that mandatory training does not heighten resistance to IDEA and depress individual responsibility.

Talent and recruitment. Recruit leaders with lived experience and/or a clear track record of IDEA leadership/action/initiatives. Intentionally hire people of colour (BIPOC) who reflect the demographics of your local population. Mandate the career advancement and promotion of BIPOC employees.

Strengthening culture. Create a physically and psychologically safe place to speak up. Foster a shared understanding of why IDEA is important.

Despite the progress enabled by these initiatives, a significant gap remains between practicing a behaviour or implementing polices/approaches and achieving durable change. Individuals from Canada’s healthcare and research ecosystem, who bring lived and living experience and a track record of excellence in IDEA-informed leadership, were interviewed to gather real-world perspective and advice. These conversations exposed three domains that are particularly challenging and complex in healthcare and research settings and where constructive disruption of the status quo can drive transformation.

Governance

While IDEA leadership can originate at all levels of an organization, boards have a powerful opportunity and responsibility to make IDEA a key metric in the assessment of an institution’s organizational effectiveness and cultural well-being. Unless IDEA is explicitly understood as a key success factor and core measure of organizational performance, the potential for meaningful transformation will be diminished. It is prudent to assess board members’ knowledge and readiness before developing an inaugural IDEA strategy and advancing any significant organizational change. Very often, it will be critical to provide education and build awareness of the need to prioritize IDEA at the governance and senior leadership levels. As noted by Dr. Elizabeth Douville, Chair, Genome Canada and Founding and Managing Partner, AmorChem: “You must not take for granted that IDEA conversations are commonplace. They are not. Discussion, education, and preparation may be needed to bring a board to a place of readiness to act.”

But embedding IDEA at the board level is not just about education. As a critical mechanism for demonstrating commitment and overseeing IDEA initiatives, it can require a rethinking of who deserves to be at the table and why. Our hospital and academic institutions are conducting the health research, advancing the innovation, and delivering the care needed by communities across Canada. And yet, their competency-based boards are typically populated by experts or elite members of society who may not live in—or even represent—the community served by these institutions. Indeed, in Canada, where women and racialized individuals represent 51% and 23% of the population, respectively, a survey of nearly 9,843 board members in Canada conducted by Ryerson’s Diversity Institute found that hospital boards have 39.6% women and 12.5% racialized members, while university and college boards have 43.1% women and 14.6% racialized members. 19 There is an urgent need to take a critical look at the skills and experiences needed among board members and consider how to reimagine these competencies through the lens of IDEA. Upon arriving at Ontario Tech, Dr. Steven Murphy, President and Vice Chancellor, recognized that the institution’s Board members, who were 75% men and predominantly white, did not reflect his aspirations for how the university would prioritize the values of IDEA, nor did they reflect the communities the university serves. Within six months, Dr. Murphy earned the board chair’s support to engage an executive search firm known for IDEA, develop a thoughtful and inclusive skills matrix, and lead a rigorous, nationwide search to select seven new board members. He argues: “When you focus on skills and experience and alternative ways of understanding and knowing, talent is never the issue.” Ultimately, a diverse board that understands and champions IDEA can showcase priorities and accelerate IDEA initiatives.

Mentorship

Strengthening IDEA competencies among leaders can be daunting due the complexity of the challenge: established and emerging leaders bring an enormous range of knowledge, readiness, lived experience, and aptitudes. Mentorship is often proposed as a solution, but best practices and measurements of impact, beyond the satisfaction of those who participate, are often poorly understood or developed. 20 It is therefore important to be clear about what is meant by mentorship and to advance what works best based on evidence. Mentorship may provide a mechanism for propagating IDEA as a mindset and competency. Mentors can educate and inspire diverse communities by ensuring that IDEA is a part of every agenda, conversation, decision, and initiative, exploring people and perspectives that have been excluded, extending opportunities to equity-seeking groups, and uplifting communities. In this way, team members learn to anticipate this line of thinking and will, in time, apply it reflexively while also developing their own strategies to implement IDEA in practice. Mentorship can also provide a mechanism for members of the dominant demographic to sponsor the historically excluded. 21 More specifically, Dr. Notisha Massiquoi, Principal Consultant, Nyanda Consulting, calls for a shift in the mentorship mentality: “We need mentors who think about developing their own successors. We need proactive mentors who will create the conditions for advancement, and guide their mentees through their career journey.”

Mentorship is not about propagating a single, proven approach to leadership; rather, to optimize benefit, mentorship should be tailored to the individual(s) who will be engaged and inclusive of the diverse models of leadership organizations need foster. Many Indigenous peoples—who, as rights bearers, do not see themselves as part of the IDEA framework—have been raised to understand leadership in a way that is less compatible with the values of academia. Dr. Carrie Bourassa, Professor Indigenous Health, University of Saskatchewan, pointed out that “Indigenous peoples often place more emphasis on humility, which can be at odds with settler notions of leadership. I have taken a mentorship approach to support young Indigenous scholars to find a voice and a way to lead in academia and beyond.” Through mentorship, a culturally safe space for learning and development can be created, making mentorship a compelling mechanism for building IDEA competencies among our leaders. As IDEA leadership is strengthened within the healthcare and research setting, there is an opportunity to embrace and amplify mentorship practices that move beyond the model of competitive merit that is so intrinsic to healthcare and, perhaps especially, research-intensive organizations.

Employee performance measurement

Many of the individuals interviewed in the development of this article spoke to the critical importance of employee performance appraisal to fully embedding IDEA in organizational cultures and practices. However, unlike many private sector settings, performance reviews are not often a standard practice in research-intensive settings, including hospitals and universities, where scientists and health leaders—despite the value they place on evidence—rarely seek or are offered data measuring their own performance beyond the institutions of peer review and tenure and promotion, which are often biased.22,23 Establishing a system of performance measurement using metrics for impact and change fosters accountability for IDEA. This is a significant cultural shift that must be met with patience, tenacity, leadership, and courage. As Christopher Townsend, Manager, Organizational Development and Leadership, Sunnybrook Hospital notes: “We have done a disservice when we say we are practicing IDEA, when we are not getting to the granular data needed to show we are impacting the culture of inclusion and transformational change with measurable outcomes.”

In addition to assessing performance of IDEA at the organizational level, specific data on the culture of IDEA should be collected. The collection of data for measurement and impact can start with employee engagement surveys and be complemented with dialogue on how leaders can foster a more inclusive workplace. Leaders in research-intensive settings—whether academic, private sector, or healthcare—must also reflect on whether prevailing definitions of excellence, which often influence promotion, compensation, and power are inclusive. Traditional models of reward and recognition place heavy emphasis on the accomplishments of the individual, frequently undervaluing success in collaborative settings. Healthcare and research organizations need to acknowledge that publications are one measure of excellence; an inclusive definition of excellence will recognize the value of diverse ways of knowing, the value of partnership development, the value of excellence in community engagement, and the value of commitment to effective communication. When this thinking and clear, granular metrics that measure its application begin to reshape systems of hiring, promotion, and tenure, the diversity of those who succeed will begin to expand.

Building a better health research and care ecosystem calls for the development of leaders inspired and guided by IDEA

When health research and healthcare professionals lead with competencies infused with IDEA, organizational performance will be enhanced. A strong and growing evidence base confirms that organizations committed to IDEA will be more successful in attracting and retaining people from a larger pool of talent, 18 drawn to organizations that are known for their progressive and inclusive culture; building teams that are stronger, more innovative, 24 engaged, and productive; and contributing to accountability within the broader healthcare and research ecosystem. The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the disproportionate impact of SARS-CoV-2 on marginalized communities, underscored how vulnerable our systems are for racialized and Indigenous groups, and how much work we have to do to ensure they are fully part of research and healthcare communities. Now is the time to develop an IDEA mindset and practical toolkit among the leaders who will create the policies, processes, and strategies at the heart of Canada’s health research and innovation ecosystem.

Conclusions and future considerations

This study has drawn attention to the pervasiveness of racism within the health research and care ecosystems and the importance of embedding IDEA in leadership as a means to dismantle systems of oppression and prejudice. Expanding upon this study, future consideration should be directed towards understanding metrics and monitoring tools to evaluate IDEA as a leadership competency and to assess impact of IDEA-infused leadership on people, culture, research, and care. Monitoring and evaluation will provide feedback required to optimize initiatives and refine approaches as health research and healthcare organizations aspire to lead through IDEA.

ORCID iD

Anne E. Mullin https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4704-2542

References

- 1.Datta G, Siddiqi A, Lofters A. Transforming race-based health research in Canada. Can Med Assoc J. 2021;193(3):E99-E100. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.201742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCarthy CR. Historical background of clinical trials involving women and minorities. Acad Med. 1994;69(9):695-698. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199409000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phillips-Beck W, Eni R, Lavoie JG, Avery Kinew K, Kyoon Achan G, Katz A. Confronting racism within the Canadian Healthcare System: systemic exclusion of first nations from quality and consistent care. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2020;17(22):8343. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17228343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nguyen NH, Subhan FB, Williams K, Chan CB. Barriers and mitigating strategies to healthcare access in indigenous communities of Canada: a narrative review. Healthcare. 2020;8(2):112. doi: 10.3390/healthcare8020112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Public Health Agency of Canada . Social determinants and inequities in health for Black Canadians: a snapshot. 2020.

- 6.Dryden O, Nnorom O. Time to dismantle systemic anti-black racism in medicine in Canada [published correction appears in CMAJ. 2021 Feb 16;193(7):E253]. Can Med Assoc J. 2021;193(2):E55-E57. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.201579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Indiana Arts Commission . What exactly is inclusion, diversity, equity and access. 2021. Available at: https://www.in.gov/arts/programs-and-services/resources/inclusion-diversity-equity-and-access-idea/. Accessed July 15, 2021.

- 8.American Alliance of Museums . Diversity, equity, accessibility and inclusion definitions. 2021. Available at: https://www.aam-us.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/AAM-DEAI-Definitions-Infographic.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2021.

- 9.Universities Canada . Equity diversity and inclusion at Canadian universities. Report on the 2019 National Survey, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sinha S, Chaudhry S, Mah B. A snapshot of diverse leadership in the health care sector. DiverseCity, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giles S. The most important leadership competencies according to leaders around the world. Harv Bus Rev. 2016;15:11-19. [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacKinnon NJ, Chow C, Kennedy PL, Persaud DD, Metge CJ, Sketris I. Management competencies for Canadian health executives: views from the field. Health Manag Forum. 2004;17(4):15-45. doi: 10.1016/S0840-4704(10)60624-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lockhart W, Backman A. Health care management competencies: identifying the GAPs. Health Manag Forum. 2009;22(2):30-37. doi: 10.1016/S0840-4704(10)60463-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Centre for Healthcare Leadership . Updated career spanning competency model for health care leaders. 2021.

- 15.Canadian College of Health Leaders . LEADS in a caring environment framework. 2021. Available at: https://leadscanada.net/site/framework. Accessed May 4, 2021.

- 16.Canadian Certified Physician Executives . About the credential. 2021. Available at: https://ccpecredential.ca/#aboutthecredetnial. Accessed May 10, 2021.

- 17.Canadian College of Health Leaders . EWOLIH toolkit. 2021. Available at: https://leadscanada.net/site/products-services/products/edi-toolkit/ewolih_toolkit/overview?nav=sidebar. Accessed May 10, 2021.

- 18.95 Expert Panelists. O’Mara J, Richter J. Global diversity and inclusion benchmarks. Standards for organizations around the world. 2017.

- 19.Cukier W, Latif R, Atputharaja A, Parameswaran H, Hon H. Diversity leads. Diverse representation in leadership: a review of eight Canadian cities. 2020.

- 20.House A, Dracup N, Burkinshaw P, Ward V, Bryant LD. Mentoring as an intervention to promote gender equality in academic medicine: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2021;11(1):e040355. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beech BM, Calles-Escandon J, Hairston KG, Langdon SE, Latham-Sadler BA, Bell RA. Mentoring programs for underrepresented minority faculty in academic medical centers: a systematic review of the literature. Acad Med. 2013;88(4):541-549. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828589e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barber PH, Hayes TB, Johnson TL, Márquez-Magaña L, 10,234 signatories . Systemic racism in higher education. Science. 2020;369(6510):1440-1441. doi: 10.1126/science.abd7140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Witteman HO, Hendricks M, Straus S, Tannenbaum C. Are gender gaps due to evaluations of the applicant or the science? A natural experiment at a national funding agency. Lancet. 2019;393(10171):531-540. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32611-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hofstra B, Kulkarni VV, Munoz-Najar Galvez S, He B, Jurafsky D, McFarland DA. The diversity-innovation paradox in science. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(17):9284-9291. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1915378117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]