Abstract

Differentiated service delivery for HIV treatment seeks to enhance medication adherence while respecting the preferences of people living with HIV. Nevertheless, patients’ experiences of using these differentiated service delivery models or approaches have not been qualitatively compared. Underpinned by the tenets of descriptive phenomenology, we explored and compared the experiences of patients in three differentiated service delivery models using the National Health Services’ Patient Experience Framework. Data were collected from 68 purposively selected people living with HIV receiving care in facility adherence clubs, community adherence clubs, and quick pharmacy pick-up. Using the constant comparative thematic analysis approach, we compared themes identified across the different participant groups. Compared to facility adherence clubs and community adherence clubs, patients in the quick pharmacy pick-up model experienced less information sharing; communication and education; and emotional/psychological support. Patients’ positive experience with a differentiated service delivery model is based on how well the model fits into their HIV disease self-management goals.

Keywords: patients’ experiences, differentiated care, differentiated service delivery models, antiretroviral therapy

Introduction

Differentiated HIV care is a simplified, tailored, client-centered approach to HIV service delivery (International AIDS Society, 2016). Differentiated HIV care aims to enhance patients’ care experience by putting the patient at the center of service delivery while ensuring that the health system is functioning in a medically accountable and efficient manner. As such, it acknowledges the specific barriers identified by patients and empowers them to self-manage their condition with the support of the health system (Shubber et al., 2016). Differentiated HIV care models or approaches are, therefore, designed to improve HIV diagnosis, linkage to care, treatment, and care for people living with HIV towards achieving the 95-95-95 goals of the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS—95% of people living with HIV are diagnosed, 95% of those diagnosed are initiated on antiretroviral treatment, and 95% of those on ART achieve viral suppression (The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, 2014). Differentiated service delivery for HIV treatment is a component of differentiated HIV care, which focuses on the last two 95s: retaining people in antiretroviral treatment and maintaining viral suppression (International AIDS Society, 2016).

Outcome-based evaluations show that differentiated service delivery models (hence simply called models) for HIV treatment improve the rates of retention in care and adherence to medication compared to the standard clinic antiretroviral therapy program in different sub-populations (Luque-Fernandez et al., 2013; Tsondai et al., 2017; Tun et al., 2019). It is further argued that models for HIV treatment ensure antiretroviral therapy safety, leading to improved viral suppression (Kwarisiima et al., 2017). Implementers of models for HIV treatment suggest that they also decongest public health care facilities (Mukumbang et al., 2016) and are instrumental in achieving national HIV treatment goals (Prust et al., 2017).

South Africa has the largest number of people living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa with 7.8 million in 2020 (The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, 2020). The enthusiastic roll-out of antiretroviral treatment to all people living with HIV irrespective of CD4 count—a significant predictor for HIV disease progression, survival, and treatment outcome—following the national guidelines has created congestion at the health facilities and placed a severe burden on under-resourced public health care facilities in South Africa (Department of Health, 2016). The congestion of patients for antiretroviral treatment services leads to increasing numbers of patients defaulting on medication owing to long waiting times and healthcare worker fatigue (MacGregor et al., 2018). In addition to these health systems barriers, individual-level factors such as forgetfulness and use of herbal remedies, faith healing, and alcohol use have also been reported in the literature (Azia et al., 2016; Heestermans et al., 2016). Interpersonal-level and community-related factors such as fear of disclosure, food insecurity, and stigma have also significantly contributed to poor medication adherence and retention in care (Mukumbang et al., 2017; Reda & Biadgilign, 2012).

To address these challenges, in 2016, the National Department of Health of South Africa encouraged the roll-out of models, namely, facility adherence clubs, community adherence clubs, and quick pharmacy pick-up, nationwide. A recent document review indicated that eight of the nine South African provinces had adopted these models (Mukumbang, Orth, et al., 2019). Models for HIV are ancillary to the mainstream antiretroviral treatment care delivery schemes, and they streamline antiretroviral treatment service delivery by adapting the care components to the needs of stable patients on antiretroviral treatment (Grimsrud et al., 2016). Stable patients are defined as those on the same antiretroviral treatment regimen for at least 6–12 months, with the two most recent consecutive viral loads undetectable, and having no medical condition requiring regular clinical consultations more than once a year (Mukumbang et al., 2016).

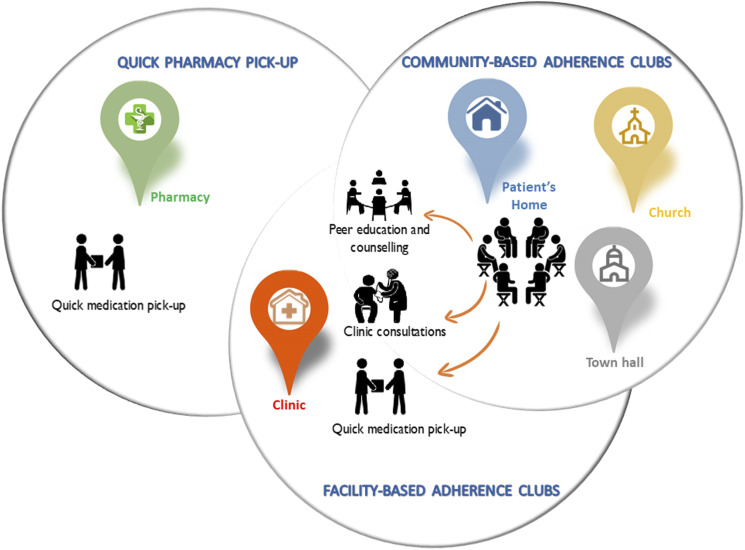

The adherence club model groups stable patients (15–30) who meet and get antiretroviral drug supply every two or three months (Mukumbang et al., 2018b). The groups are facilitated by a lay health worker who provides counseling and education sessions, weighs the patients, and distributes prepacked medication as well as facilitates the space for patients to discuss various issues for social support (Mukumbang, Orth, et al., 2019). The adherence club model intervention can be hosted in a facility (facility-based) or out of the facility (community-based), depending on the availability of space and resources. By contrast, the quick pick-up model is a fast-lane model of care where patients pick up their medication in the facility without a visit to a clinician. The quick pick-up was designed to include more patients and can accommodate 50 patients in one quick pick-up group. The quick pick-up model is also considered a flexible approach because it allows patients to send people they trust to pick up their medication supply (Mukumbang, 2021). Figure 1 shows the similarities and differences shared by these models.

Figure 1.

Similarities and differences between the three antiretroviral treatment delivery models (Mukumbang, 2021).

While various evaluation studies have shown that models improve retention in care and adherence to medication of patients on antiretroviral treatment, patients’ experiences of using these models have not been systematically compared. Understanding the experiences of people living with HIV receiving antiretroviral treatment in models can improve the delivery of antiretroviral treatment care to improve their experiences, consequently improving their retention in care and medication adherence. To this end, we conducted a comparative qualitative research on the experiences of patients in facility adherence clubs, community adherence clubs, and quick (pharmacy) pick-up in a public health facility in a township in the greater Cape Town area in South Africa.

Theoretical Framework

Our study aimed to compare the experiences of patients on antiretroviral treatment in three differentiated care delivery models. Because our comparison is based on the lived experience descriptions of these patients, we underpinned our study within the phenomenological paradigm, specifically descriptive phenomenology (Lopez & Willis, 2004). We adopted this paradigm because our study focuses on experience and intentionality for comparative determinations (Van Manen, 2017). Although we adopted tenets such as epoché or bracketing—eliminating preconceptions that may taint the research process (Tufford & Newman, 2012), we by no means argue that it is phenomenological in its purest form. The methodological consequences of adopting tenets from descriptive phenomenology are that we could allow “experience” to appear in its terms (Smith, 2018) and be reflective of these experiences to tease out differences and similarities for comparisons.

Methods

Study Design

An exploratory qualitative research study design underpinned by tenets of the descriptive phenomenological paradigm (Lopez & Willis, 2004) was conducted from June to November 2019 to compare the experiences of people accessing antiretroviral treatment through differentiated care models. Our approach allowed us to document and interpret the different ways in which people living with HIV make sense of their experiences of health and disease (Bradshaw et al., 2017). The comparison of patients’ experiences was guided by the National Health Services Patient Experience Framework (Department of Health, 2011).

Study Setting

The study was conducted in a primary health clinic situated in the community of Khayelitsha. Khayelitsha is a predominantly black township, which was established in 1983 and situated approximately 30.5 km from the City of Cape Town city center. Khayelitsha has a mix of formal and informal housing structures, although dominated by informal housing known as shacks (Knight et al., 2018). Most adult residents of Khayelitsha were born in the Eastern Cape province and retain close links to their rural areas of birth. Poverty and crime are widespread in Khayelitsha, with half of its population falling into the lowest income quintile and the rest into the second lowest income quintile for the entire city of Cape Town (Seekings, 2013). The majority of the population of Khayelitsha relies on government social grants, especially child support grants (Seekings, 2013).

The clinic was identified by the Khayelitsha Eastern sub-structure management in November 2015 to pilot three differentiated service delivery models, namely, facility adherence clubs, community adherence clubs, and quick pick-ups. As of June 2017, the clinic had 7091 patients retained in antiretroviral care. Of these, 2483 were retained in the adherence club care; amounting to 35% of patients getting their care in either facility adherence clubs or community adherence clubs. The facility had 110 adherence clubs, 50 community adherence clubs, and 60 facility adherence clubs at the time of this study. The quick pick-ups model has 28 groups of patients with each group having an average of 45 patients. An estimated 1054 patients were retained in quick pick-ups in June 2017.

Our case study clinic was selected because it is one of the facilities in the sub-structure with the highest HIV cohort and one of the few public health facilities implementing all three models (Mukumbang, 2021). With most of the patients on antiretroviral treatment at the facility being stable patients, the facility adherence clubs reached maximum capacity as determined by the available resources. The facility consequently introduced the community adherence clubs and the quick pick-ups to further decentralize antiretroviral delivery and broaden patients’ preferences on the option of care to reduce clinic congestion.

Participant Selection and Data Collection

The study population included people living with HIV using models in the case study clinic. The inclusion criteria of the study population were people living with HIV (18 years plus) who at the time of the study were receiving antiretroviral treatment in models. A multi-level participant selection process was adopted.

At the first level, a couple of facility adherence clubs, community adherence clubs, and quick pick-ups were randomly selected for focus group discussions. The random selection was achieved using the fishbowl or lottery method of sampling (Punsalan & Uriarte, 1987) from the 50 community adherence clubs, 60 facility adherence clubs, and 28 quick pick-ups existing at the time of this study. Each model was randomized separately.

At the second level of participant selection, six to ten participants were purposively selected to take part in a focus group discussion, two for each type of model. The purposive selection was achieved by open invitation during the attendance of an HIV service delivery session in the respective model. Participants were included in the initial focus group discussions if they (1) were enrolled in one of the models and (2) had been receiving care for more than 6 months.

A particular disadvantage of a focus group is the possibility that the members may be hesitant to describe their experiences, especially when their experiences are not in line with those of another participant. Thus, the third level of participant selection was undertaken, which involved using in-depth interviews to provide the platform for these participants to express their experiences without fear of contradiction or judgment. From each of the models, four focus group discussions participants were purposively selected to participate in one-on-one in-depth interviews. We estimated that two participants from each of the six focus group discussions were enough to provide sufficient information power based on (a) the aim of the study, (b) quality of dialogue, and (c) analysis strategy (Malterud et al., 2016). An additional nine participants, who were not part of the focus group discussions, three from each of the models, were purposively recruited for in-depth interviews to confirm that the themes identified were not unique to those patients who participated in the focus group discussions.

Following the three steps of participant selection, there were 68 participants: 29 males and 39 females. The characteristics of the study participants are described in Supplemental File 1. Two participants approached in the quick pick-up model turned down our invitation suggesting that they were in a hurry and did not have time to participate. Two participants from the facility adherence club after agreeing to take part in the in-depth interviews changed their minds and had to be replaced. The community adherence club participants were the most enthusiastic to participate in the study. Supplemental Figure 2 provides a summary of the participant selection process.

Ms. Ndlovu attended HIV service delivery sessions of the different models and introduced the attendees to the study. Ms. Ndlovu also conducted the interviews and facilitated the focus group discussions. Given the close relationship between the researchers/authors and the research topic, bracketing techniques were applied. We applied memoing as our approach in the form of theoretical notes explaining our cognitive process of conducting the study, methodological notes illustrating the research steps, and observational comments that allowed us to explore feelings about the study (Tufford & Newman, 2012). Discursive and reflective meetings between the researchers/authors were also applied as an approach to bracketing, which usually took place a day after the data collection session and before the next planned data collection activities.

Those who consented participated in the focus group discussions in their next scheduled HIV service delivery session. Focus group discussions were conducted at the place where the HIV service delivery activities of the model are held and each focus group discussion lasted between 45–60 minutes. For instance, facility boardroom for facility adherence clubs or church hall for community adherence clubs. Focus group discussion and in-depth interview guides were piloted with one focus group discussion and two in-depth interviews, respectively, and revised (Supplemental File 3). The questions were related to (1) their experience with their preferred modalities of their differentiated service delivery models; (2) why the participants preferred their selected model over others; and (3) how the model helped the participants to remain in care and adhere to medication. The similarities and differences in opinion during the discussion sessions were noted and further explored in the in-depth interviews.

The in-depth interviews lasted between 20–30 min each and were conducted in a private room within the healthcare facility. The in-depth interviews allowed the researchers to explore further the experiences of the participants in their respective models. The focus group discussions and in-depth interviews were conducted in isiXhosa, the local language. The focus group discussion and in-depth interview sessions were audio-recorded with permission from the participants.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This study received ethics approval from the University of the Western Cape’s Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (Ref. BM19/1/18) and permission from the Western Cape Province’s Provincial Health Research committee (Ref. WC_201903-029). Permission was sought from the Community Health Facility where the study was conducted.

Informed consent was obtained from all study participants before their participation. The purpose and objectives of the study were provided to each participant before their enrollment into the study. The informed consent also detailed the voluntary nature of the participation to the participants emphasizing their right to withdraw at any phase of the research focus group discussions or in-depth interviews. Confidentiality was ensured at all stages of the study, and pseudonyms are used in reporting the findings.

Data Analysis

We transcribed the recorded interviews verbatim in isiXhosa and translated them into English. Based on the study objective, a thematic Constant Comparative Analysis Method (Boeije, 2002) was adopted. In this analysis approach, we sought to describe and conceptualize the variety that exists within the participants using the different models. These variations were extracted by looking for commonalities and differences in behavior, experiences, reasons, and perspectives of the differentiated service delivery users (Boeije, 2002). Our comparisons were at three levels: (1) Comparison within a single focus group discussion/interview; (2) Comparison between focus group discussions and interviews within the same group; and (3) Comparison of focus group discussions and interviews from different models.

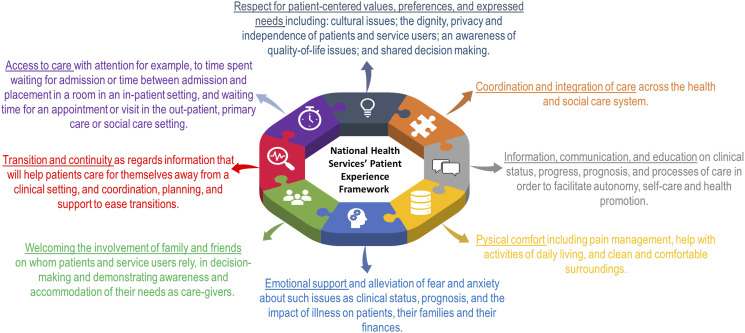

Our data analysis and comparison were informed by the National Health Services’ Patient Experience Framework—Figure 2 (Department of Health, 2011). The Patient Experience Framework is based on a modified version of the Picker Institute Principles of Patient-Centered Care, an evidence-based definition of a good patient experience (Department of Health, 2011). This evidence-based framework is centered around the Care Quality Commission’s key themes to enable healthcare providers to continuously improve the experience of patients (Department of Health, 2011). We, therefore, found this framework useful to compare the patients’ experiences in the available models to improve patients’ experiences towards HIV self-management.

Figure 2.

National Health Services’ patient experience framework.

We coded the transcripts on each of the models independently based on a codebook developed by all three authors following the Patient Experience Framework. The codes were grouped into themes while comparing the codes obtained in the different models. The authors met up a week later to compare their coding and classification. Discussions were held first on the coding and then on the comparisons between experiences of the study participants in the various models. Issues of contention were resolved through discursive reflections.

Results

The reporting or our findings followed guidance offered by Broom (2021) to conceptualize the data to speak to what underpins the study beyond mere description. Table 1 illustrates the main themes abstracted through the thematic analysis based on the different components of the National Health Services’ Patient Experience Framework.

Table 1.

Thematic table informed by the Patient Experience Framework.

| Categories | Themes | Sub-themes |

|---|---|---|

| Respect for patient-centered value, preferences, and expressed need | - Selection of model of care as preference and expressed need | - Model selection |

| - Quick service | ||

| - Shorter waiting times | ||

| - Easy access to medication | ||

| - Flexible | ||

| - Buddy support | ||

| - Service delivery as patients’ expressed need | - Effective service rendered | |

| - Addressing patient needs | - Patient-centeredness | |

| - Self-management as a patient-centered value | - Patient empowerment | |

| Coordination and integration of care | - Amalgamation of complementary services in differentiated service delivery models | - Health promotion |

| - Psychosocial support | ||

| Information, communication, and education | - Provision of health education | - Health empowerment |

| - Relationship with the facilitator as an information and communication tool | - Psychosocial support | |

| Physical comfort | - Venue/location convenience | - Safe space |

| - Good infrastructure | ||

| - Environment convenience | - Stigma-free environment | |

| - Safety | ||

| Emotional support | - Camaraderie | - Peer-to-peer support |

| - Psychosocial benefits | ||

| - Group empowerment | ||

| Welcoming the involvement of family and friends | - Inclusion of the social structure (family and friends) as psychosocial support | - Coping mechanisms |

| - Family support | ||

| Transition and continuity | - Allocation of health practitioners to support running differentiated service delivery models | - Clinical support system |

| - Supporting mobility of patients (migration period) | - Longer supply of medication (festive season) | |

| Access to care | - Differentiated service delivery models visit preparation | - Easy access to ART medication |

| - Travel to point of differentiated service delivery models care | - Easy access to point of care |

Respect for Patient-Centered Value, Preferences, and Expressed Need

Four themes were identified in this category and they include (1) the selection of the model of care as a preference, (2) service delivery as patients’ expressed need, (3) addressing patient needs, and (4) self-management as a patient-centered value.

Preference and expressed need

Patients in the facility adherence clubs indicated that the selection of patients to join the model did not follow the notion of patient preferences. Most participants in the facility adherence clubs reported that they were not offered the opportunity to choose which of the three models they preferred as only the facility adherence clubs existed at the inception.

I did not choose the club [facility adherence club]. I was told to come here by the nurse after seeing that I was up-to-date with all my appointments and my blood results were always good and that the club was very easy and quick than in the clinic. That is how I joined the club—Male; Facility adherence club.

I was told I was doing well on my dates of coming to the clinic. They told me that there was something called a club where you get your treatment easy unlike queuing for long hours in the clinic—Female; Facility adherence club.

Although the whole range of models was not in operation in the early stages, stable patients on antiretroviral treatment who qualified for models were presented with the opportunity to leave the mainstream care and join the facility adherence clubs.

For me, the nurse asked if I liked waiting and sitting all day waiting to access the services. I told them I did not like it. They then asked me if I could join the club and I said I would be very happy to. She then explained to me about the club how it works and all its benefits and then I joined—Female; Facility adherence club.

Patients receiving care in community adherence clubs and quick pick-up models unlike facility adherence club patients were offered the three options of care to choose from when they fulfilled the criteria for joining a model.

The sister [nurse] realized that I always came to the clinic on my appointment date and that I was never sick, and she told me that I am fit to be in the three programs that offer antiretrovirals in the clinic. She mentioned them and she asked which one I chose. She explained all these programs and I told her it will be ok for me to join quick pick-up—Male; Quick pick-up

Service delivery as patients’ expressed need

Service delivery as patients’ expressed need is achieved in the models through quick services or short waiting times. Patients in all three models stated that they experienced quick service delivery concerning getting their antiretroviral treatment. They indicated less time spent in the models compared to when they were in the facility’s standard antiretroviral treatment service—where they would spend almost the whole day waiting to get their medication. Patients indicated that the time they spent in the models was shorter and allowed them to go to work and continue with other daily activities.

I like it more here because you do not wait long. See now, I will be able to go to work and I have not even asked for a day off work, but I have my medication. This community club is helping us—Female, Community adherence club.

An aspect of patient-centered care is related to addressing the expressed needs of the patients. This is achieved through easy access to antiretroviral treatment without the need to stand in long queues before getting their medication. Each patient’s medication is prepacked and prepared before their attendance.

Yes, it is quick here and we find our things [medication] prepared for us…you do not spend more than an hour here—Male; Community adherence club.

The models addressed patients’ healthcare needs and accommodated their social lives, as they were able to continue with their daily activities while accessing and taking their medication.

I chose this one for the morning because it was working for me. I am a person who works. So, starting here for me is very easy. I can also inform my workplace that I will be a bit late when I come here, and I get my medication. So, I know I can start here—Male; Facility adherence club.

Self-management is an important aspect of long-term HIV treatment. Most participants in all the models for HIV indicated they could self-manage their disease with what the models offered.

Most of us have been long on treatment. They said we could manage ourselves in the community as compared to the new ones who still needed to be in the facility and monitored by the nurses there close by—Male; Community adherence club.

Addressing patient needs

Different patients had different needs regarding the time to pick up their medication. The scheduled time for patients to collect their medication varied across the models. Patients in both facility adherence club and community adherence club collected their medication early in the morning before they could go to work.

It is very quick such that you can go to work from here unlike in the clinic where you spend the whole day. You come to the club at 7:30 in the morning, at about 8:30 you know you are going to work—Female; Community adherence club.

However, here when you come to the club like now at 7 in the morning. You know by 7:30 and 8 o’clock you are gone when you are late. It is very quick than in the facility. That is why I like it—Female; Facility adherence club.

Patients in the quick pick-up model have the option of collecting their medication in the evening between 4:00 and 6:00, which they expressed as convenient for them being after working hours.

The time for quick pick-up is really flexible for me. Quick pick-up is easy for me to come after work. That is why I chose it—Male, Quick pick-up.

Although issues related to dedicated personnel to run the model were identified by participants interviewed across all models, the overall experience was that, compared to the mainstream health facility, service delivery in the different models of care was effective.

No one in this club that I know of has experienced such a thing as going home without medication. Everyone comes here and we have our medication ready for us—Male; Community adherence club.

Another aspect of patient-centered care is patients’ participation—where patients are offered the opportunity to play active roles in their care. A participant explained why contact with healthcare providers is important.

Yes, we do have the contact for the facilitator so that we ask questions when there is something that we do not understand. She often encourages me to take my medication every day so that my viral load remains suppressed—Female; Community adherence club.

Self-management as a patient-centered value

Some of the participants made statements that indicate that they receive continuous support, which enhanced their ability to self-manage their disease. Two participants recounted that they are in WhatsApp groups and can contact their group facilitators at any time should they have antiretroviral treatment-related challenges.

In this club, we have a WhatsApp group where we not only remind each other of club appointments, but people also post different things. Most people ask in the group if they have symptoms that they do not understand—Female; Facility adherence club.

We even have her phone number. If there are things that we do not understand we can send her a WhatsApp message—Female; Community adherence club.

Coordination and Integration of Care

Coordination and integration of care refer to a collaboration between the health and social health care systems. Apart from receiving their medication, patients were asked if they accessed any other services in their models of care, and if not, what could be provided.

Complementary services received at the models varied among participants interviewed. Adherence clubs provide health promotion aspects through the education or health-talk session where club patients engage with each other on different topics and discussion affecting them in a more general platform. Most participants interviewed identified health talks as some form of peer-to-peer support that they got from adherence clubs in addition to their medication pick-up:

No, we only get an education with the facilitator. We talk about different things and most of the time she talks about the importance of taking treatment as expected and nothing else—Female; Facility adherence club.

We come here and we give our facilitator the cards. After that, we get onto a scale and then we chat as a group. Most of the discussion we talk about making sure people take their treatment—Female; Community adherence club.

The peer-to-peer support aspect of the adherence club model was strongly present in the community adherence clubs where patients interact and engage with each other and even contact each other outside of the club space.

We always advise each other on the importance of taking medication in our group. We are few women that are in the club and we also have a “Stokvel” [financial contribution]—Female; Community adherence club.

Unlike the adherence clubs, quick pick-up does not have health-talk sessions because the main idea was to only provide quick access to medication.

Here [QPUP] we only get our medication and go. There are no other sessions that we have—Male; Quick pick-up.

Information, Communication, and Education

Patients who were interviewed were asked if they received any information on their health and treatment journey to enhance their disease management in their model of care.

Access to health education and information

Patients in facility and community adherence clubs stated that they received health education. They indicated that it is in these sessions they were encouraged to remain adherent to their medication.

Here, in the club, we arrive and we give them our clinic cards. We take the weights and we sit. After that, we have a talk session where they ask about how we are doing. We also state we are ok. If we are not, they tell us to go to the clinic and meet up with the sister [nurse]. We are also encouraged to take antiretrovirals as expected so that we are not taken out of the club—Female; Community adherence club.

Communication: Relationship with club facilitator

The health education session in the adherence clubs allowed patients to form a relationship with the club facilitator. Participants stated that this created an environment where they can interact and ask for information from the club facilitator.

Yes, the facilitator often talks and advises us on the importance of taking medication and how we need to make sure we have drawn blood every year to see if the medication is working in the blood—Male; Facility adherence club.

Patients in adherence clubs indicated having a very good and interactive relationship with their club facilitators and that emotionally supported their continued adherence to medication.

You know you come here, and the club facilitator is already waiting for you. In the clinic, you would not even know the person assisting you. You are told sometimes that the person helping you is not there and then someone else comes. Here we know this lady is the one who will help us—Male; Community adherence club.

Quick pick-up patients’ experiences in terms of educational talks varied vastly from those in the facility adherence club and community adherence club. Although the quick pick-up model does not have health-talk sessions as part of their model of care, participants using the quick pick-up model indicated that the facilitator was approachable and provided any required information.

Here [Quick pick-up] the person who helps us does not have any issues or attitudes. You can even ask anything; they politely explain to you in a kind manner—Female; Quick pick-up.

Although I have never asked for anything, he [facilitator] is approachable. I have seen people talk to him and I think he is a nice person—Male; Quick pick-up.

Physical Comfort

Physical comfort considers elements such as venues and settings where patients access their care. Patients in the models were asked about their thoughts on the environment or setting in which their models operated. Facility adherence club and quick pick-up models took place in facility-based structures. The community adherence clubs used a community hall, church, or other social venues in the community.

Venue convenience

Patients in the quick pick-up model expressed that the venue was convenient for them as they spent less time in the facility.

For me, I like it here because we are in the clinic like anyone else. No one knows or cares who is here for what—Male; Quick pick-up.

Patients in community adherence clubs, using a community hall run by a local Community-Based Organization, explained that they felt comfortable and safe.

It is ok to collect our medication from this place… there are even chairs here where we can sit comfortably—Female; Community adherence club.

We always find the door open and there is a security guard here and we feel safe. The place also has a heater especially now in winter and it is always warm—Female, Community adherence club.

Patients in the facility adherence club accessed their care in the facility’s boardroom and were happy that they had a dedicated space close to other health care services if they need them.

I like it here because we do not get to mix with the whole patient in the clinic. We are on our own here—Male; Facility adherence club.

This venue is ok for me. If I need to see the nurse or doctor on the day, I only go to the reception and get my folder just around the corner. We do not queue and there is no crowding. It is only club patients—Female, Facility adherence club.

Environmental convenience

Most participants indicated that the models offered a stigma-free environment. This was because they met with people in the same situation as them.

People would come when we are seated there to collect and ask ‘which one is quick pick-up line” so no one knows what QPUP is except for the people who are in this program and that is fine for me—Female; Quick pick-up.

Although some patients found safety in the environment provided by the models, some patients indicated that they did not mind being seen collecting their antiretroviral medication as they are considered their health more important.

For me, I am just concerned about my health and nothing else. I do not care what they say or do not. The other thing is, people should not judge other people because you do not know what made them be here—Female, Quick pick-up

As much as the models encourage disclosure of HIV status to family and friends, some participants in adherence clubs, on the contrary, stated that they were afraid for their status to be known in the communities as they feared being stigmatized and discriminated against.

We are free to talk about HIV at home but in the community, there are also some frustrating situations because they do not call it HIV, they say that thing, they call it “Omo” [HIV] and that is not nice. I fear what they will say to me if they know that I am HIV positive—Female, Community adherence club.

Emotional Support From Peers and Health Workers

This category explores the extent to which each of the models provided emotional support to their patients as this has been viewed as a motivator for patients to be adherent to remain in care and adhere to their medication.

Group camaraderie and peer support

Emotional support among patients in the three models of care varied as they expressed different opinions regarding peer-to-peer support. Most patients in community adherence clubs highlighted that they offered each other peer support as they had built camaraderie.

I do have the number of everyone here... this is for us to remind each other of the club date and even when there are blood draws and we need to go to the facility—Female; Community adherence club.

Although not as conspicuous as in the community adherence clubs, patients in facility adherence clubs highlighted that they interact with other club members including outside of the club appointment sessions and schedules to enhance their treatment journey.

I have someone I know but she moved to another club. If I am not feeling well, I can call her, and we talk because she is also with this disease. It is easy to interact with her—Female; Facility adherence club.

Patients in the quick pharmacy pick-up model indicated that they never interacted with their peers in the same model of care outside of the facility. Patients highlighted that most of the time, they went at different times to pick up their medication making it unlikely that they interacted with each other.

Most of the time we just come in here and pick up our medication and go. We often do not come at the same time—Female; Quick pick-up.

We have not met each other. Even today, we met because you called us. Otherwise, we just come and get our medication and go. I have never met other group members before this meeting—Female; Quick pick-up.

Group empowerment

Adherence clubs have been reported to be a source of peer-to-peer encouragement and empowerment for patients to navigate common challenges. Patients in facility adherence clubs and community adherence clubs suggested that they were empowered by the support they received from their peers.

If you are not feeling well, they can also advise on what to do since we are all on the same journey. Maybe I might have gone through the same thing. So, I will share my experiences—Male; Community adherence club.

For me, I have someone whom we stay close to in the community... We chat and talk often, and we have a good relationship—Female; Facility adherence club.

Welcoming the Involvement of Family and Friends

The involvement of family and friends as a principle in the National Health Services’ Patient Experience Framework focuses on the importance of support from family and friends. The most conspicuous opportunity of family involvement in the models is through practical support.

Practical support

Most participants interviewed across the models suggested making use of the “buddy” modality, a system where a relative or significant other is allowed to collect their medication on their behalf.

I always send my child to collect medication for me when I cannot come—Female; Community adherence club.

Transition and Continuity

It is pivotal that the health care system puts measures in place to ensure patients have continued access to care. Continued patient support enhances their retention in care and adherence to medication. These were achieved through (1) a dedicated health practitioner and (2) increased supplies over festive seasons.

Allocation of a health practitioner

Patients in all the models have annual blood and clinical visits to the facility where they have blood drawn and comprehensive clinical visits to check their overall clinical concerns, and a health practitioner is allocated to support these activities. Patients who were interviewed in the models indicated that they came to the facility, and a clinician was allocated to facilitate the process.

The facilitator always directs us to the nurse that will do our blood or clinical visit—Male; Community adherence club.

Although we stay longer than usual on the clinical visits, we know that we have an allocated nurse for us on the day—Female; Facility adherence club.

With the nature of the quick pick-up model, and how the model was designed, unlike in clubs where they have an allocated clinician for their blood and clinical visits, patients in the quick pick-up model follow clinic routine like any other patient on their annual clinical visit. When asked about their thoughts around the clinical visit and having to queue like any other patient, they had this to say:

When I joined quick pick-up they told me I will come and pick up my medication in the window and everything else will continue as before like drawing blood and clinical visits. Although it is not easy to queue because we are now used to picking up medication and go, it is also important that I have a nurse check me if everything is still ok—Male; Quick pick-up.

Migration/annual transition period

During the festive season period where patients migrate outside of the province, the models provide four monthly supplies of medication to accommodate the migration period. Participants interviewed highlighted this feature, which allows them to travel without the worry of running out of medication.

We get four months’ medication during December because some of us go to the Eastern Cape—Female; Community adherence club.

I like the holiday season because that is where we get four months’ medication. You get to stay at home and travel without even thinking of coming to the clinic—Male; Quick pick-up.

Access to Care

It is important to address the needs of populations, taking into consideration their social, economic, cultural, and environmental aspects. Two relevant themes were captured, namely: (1) visit preparation and (2) easy travel to model sites.

Visit preparations

To provide effective healthcare services, the facilitator prepares for the particular model visit a day before depending on the type of visit. For all the visits, medications are pre-prepared so that all patients in the model have their medication ready. If it is a blood or clinical visit, appropriate forms and files are also prepared before the sessions.

We know that when we arrive at 7 in the morning, he will be here waiting for us. He always tells us when it is a clinical visit to come early because he has organized with the nurse to see us. So that is why we come early—Female; Facility adherence club.

Easy travel to point of ART collection

Patients in all the models interviewed highlighted the convenience of accessing their health care services at the clinic for patients accessing care in the quick pick-up and facility adherence club models. Most patients highlighted the convenience of walking to the facility. They indicated that the venues allowed them to collect their medication without any traveling challenges.

I walked because I stay very close—Male; Facility adherence club.

I do not know about others no we walk most of us because we stay close to the area—Female; Facility adherence club.

Thematic Comparison of the Patient Experiences

Following the comparative analytic approach, after identifying the relevant themes attributed to patients’ experiences as informed by the National Health Services’ Patient Experience Framework on patient healthcare experience, we charted the differences and similarities of patients’ experiences of the different models (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of themes in the three differentiated ART delivery models.

| Identified codes based on patients’ experiences | Facility adherence clubs | Community adherence clubs | Quick pick-up |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respect for patient-centered value, preferences, and expressed need | |||

| Model selection | √ | √ | √ |

| Quick service | √ | √ | √ |

| Shorter waiting times compared to standard clinic care | √ | √ | √ |

| Easy access to medication | √ | √ | √ |

| Flexible | √ | √ | √ |

| Buddy support | √ | √ | √ |

| Effective service rendered | √ | √ | √ |

| Patient-centeredness | √ | √ | √ |

| Patient empowerment | √ | √ | √ |

| Coordination and integration of care | |||

| Health promotion | √ | √ | X |

| Psychosocial support | √ | √ | X |

| Information, communication and education | |||

| Health empowerment | √ | √ | X |

| Sensitization | √ | √ | X |

| Physical comfort | |||

| Safe space | √ | √ | X |

| Good infrastructure | √ | √ | - |

| Stigma-free environment | √ | √ | - |

| Safety | √ | √ | - |

| Emotional support | |||

| Peer-to-peer support | √ | √ | X |

| Psychosocial benefits | √ | √ | X |

| Group empowerment | √ | √ | X |

| Transition and continuity | |||

| Clinical support system | √ | √ | X |

| Longer supply of medication (festive season) | √ | √ | √ |

| Access to care | |||

| Easy access to ART medication | √ | √ | √ |

| Easy access to point of care | X | √ | X |

√: Yes; X: No -: Not applicable.

Discussion

Since models started showing promising results regarding the improvement of retention in care of people living with HIV and their medication adherence, there have been calls to unearth the experiences of patients using these models to improve their effectiveness (Eshun-Wilson et al., 2019). We provide experiential evidence of receiving antiretroviral treatment in three models—facility and community adherence clubs, quick pick-up—in a township public health facility in Cape Town, South Africa.

Based on patients’ experiences, the respect for the patient-centered value, preferences, and expressed need aspect of the National Health Services’ Patient Experience Framework were met by all three models. Patients from all three models identified the availability (including after-hours) and quick access to antiretroviral treatment as being valuable to their experience and informed their preference of the quick pick-up model. Nevertheless, the experience of camaraderie and social support attracted other patients to facility and community adherence clubs. Regarding the attributes of patient-centeredness as prescribed by the National Health Services’ Patient Experience Framework, we found that although some patients prefer the quick pick-up model, it fell short on attributes such as coordination and integration of care, information sharing, communication, and education, and psychological support.

We uncovered that patients experienced quick service delivery and shorter waiting times regarding access to their medication across the three models. Patients’ preferences and needs were addressed through the flexibility on the times of collection, who to collect, and the grace period. The effective service delivery and flexibility of the models to addressing patients’ needs in models as compared to the standard of care allow patients to comfortably collect their medication and continue with their daily activities (Dudhia & Kagee, 2015). This notion is supported by other studies purporting that the flexibility in models increased patients’ appeal as they are patient-centered and speak to different patients’ preferences and expressed needs (Eshun-Wilson et al., 2019; Sharer et al., 2019).

Our study also found that patients were allowed to choose the care model they preferred. Patients were offered the opportunity to choose any of the models they desired to join when they met the criteria to join a differentiated service delivery model. Sharer et al. (2019) and Trafford et al. (2018) revealed that patients desired to receive care from models that accommodate their daily routine; thus, desirability is pivotal in addressing patients’ needs and preferences. They further reiterate that models should fit within the health system and match patient preferences in different settings and contexts for them to be effective.

Regarding coordination and integration, this study showed that complementary services to those provided in the models were integral to achieving positive health outcomes. Mukumbang, Orth, et al. (2019) unearthed that models such as facility and community adherence clubs have the additional treatment and care modalities supplementing the standard antiretroviral treatment collection session, where needed. Therefore, there is an opportunity for patients using models with comorbidities to be managed within the model to enhance their medication adherence and overall health.

Health talks were identified as a form of psychosocial support as the people living with HIV had the freedom to share their experiences, challenges, and fears with people in similar situations and circumstances. Root and Whiteside (2013) confirmed that health talks cultivate social relationships between the healthcare workers and people living with HIV whereby patients experiencing stigma, side effects, and any other obstacles are supported. Studies have shown a significant increase in HIV knowledge and perceived psychosocial support when HIV-related services are provided together (Kaplan et al., 2017). Quick pick-up patients’ experiences in terms of educational talks varied vastly from those in the facility and community adherence clubs because this model does not have any education modality.

We found that venue and space convenience and the general environment where patients accessed their care are of importance to people living with HIV. In congruence to the requirement of healthcare interventions to offer physical comfort, we found that patients were comfortable in the different venues where they met. According to Jones (2004), physical design and presentation affect aspects of care delivery. Therefore, venues need to be logistically feasible and safe—the latter being a concern shared by most of the study participants.

We found that models cushioned stigma and discrimination. Patients highlighted the sense of security regarding stigma based on the biosocial environment offered by the models. Nevertheless, patients using models with non-HIV patients perceived the possibility of being stigmatized (Mukumbang et al., 2018a). We found that people living with HIV using the quick pick-up selected the model, in part, because it has less interaction with other people living with HIV, thus fewer chances of their status being inadvertently revealed to the community. Models’ role in neutralizing or buffering stigma and discrimination has also been highlighted by several studies (Mannell et al., 2014; Venables et al., 2019; Zanolini et al., 2018).

Our study unveiled that patients valued peer-to-peer social and emotional support amongst patients in models. Peer-to-peer social support is facilitated in models such as facility and community adherence clubs that accommodate group interaction, and the development of community-based treatment social support networks (Venables et al., 2019). Their study findings suggested that peer-to-peer relationships spilled outside of the club session creating bigger community relationships. Other studies confirmed that the psychosocial aspect of the group antiretroviral treatment models provided patient support and improved adherence to treatment (Agaba et al., 2018; Ware et al., 2009). Social support including emotional support has been found to empower patients to self-manage their disease (MSF, 2014; Mukumbang, Wyk, et al., 2019). We found that group-based models are a mechanism for bringing individuals together for peer support, which is crucial for navigating the treatment journey. Patients in the quick pick-up model varied in their experience of group support as they mostly picked their medication individually and at random times, and not in a group setting or set time.

Our study uncovered the involvement of family and friends in all three models. The opportunity provided by models for families and friends to pick up medication on behalf of the patients is an important way that models enhance the involvement of families and friends in treatment support. Clinical and empirical findings suggest that strategies meant to improve and strengthen family support and care for people living with HIV are paramount to positive health outcomes (Belsey, 2005; Xu et al., 2017).

Our findings unveiled that patients in models appreciated the inclusion of other modalities to support and ensure their continued access to other care services. To support continued access to care, the models have a health practitioner allocated to support the clinical aspects to the models as evidenced by patients having their viral load monitored on an annual basis through a comprehensive clinical consultation (Flämig et al., 2019; Tsondai et al., 2017; UNAIDS, 2016).

Because most adults living in Khayelitsha are from the Eastern Cape province and retain their ties to their villages (Seekings, 2013), to ensure continued access to antiretroviral treatment, models provide patients with 4 months’ supply of medication during the festive season (November to February) to accommodate patients traveling to their villages. According to Mesic et al. (2017), providing 4 months of medication during the festive season rather than 2 months’ supply contributes to the improved retention in care of patients in models.

Our study revealed that models provide flexibility to patients to navigate taking their treatment and continue with their daily commitments. Being in a model allowed for easy access to medication, which facilitates timely medication pick-up to accommodate other commitments. The quick pick-up model allowed patients to pick up their medication on their way from work. Flexibility in terms of time for medication pick-up allowed patients to schedule their daily work activities around their antiretroviral treatment commitments. The flexibility of models increased their appeal to patients and allowed the patients to choose where and when they want to access care (Sharer et al., 2019).

We found that models offered easy accessibility to antiretroviral treatment collection venues and reducing out-of-pocket expenditure on transportation. Easy access to antiretroviral treatment is a vital component in improving health outcomes (Duncombe et al., 2015). Studies have found long distances from the facility and transport costs as barriers to accessing HIV services (Agaba et al., 2018; Eshun-Wilson et al., 2019). Increased community-based antiretroviral treatment services options can address these barriers.

Policy Implications

As unveiled by our findings, patients in the quick pick-up model rarely received any interaction with the health service providers other than picking up their medication and during their blood draw and clinical consultation dates. The use of text messaging to provide health information and promotion can allow patients to update their knowledge and take control of their care and treatment.

Once a year, patients in the models have their blood drawn for viral load monitoring and comprehensive clinical consultation check-up. Patients in community adherence clubs need to return to the host facility to access these services. Providing a conducive environment and clear process flow to have a clinician visit the community adherence clubs and offer the service at their community venue can improve patients’ antiretroviral treatment experiences.

Through models, especially the community-oriented models, people living with HIV and communities affected by HIV are empowered to take control of their disease management. According to Pantelic et al. (2018), the wealth of experience gained by people living with HIV through models empowers them to maneuver their lives, knowing exactly what is appropriate and effective in their circumstances. We hereby support calls to re-direct the design and roll-out of effective HIV treatment and care services based on a thorough understanding of clients’ lived experiences and their expertise gained through service use to further empower them.

Strengths and Limitations

Only two groups per model were included in the study, which is not representative of the antiretroviral treatment cohort in the facility. To overcome this limitation, study participants were recruited until thematic saturation was achieved. Because a comparative thematic analytic approach was used, we systematically recruited participants from all three models. We also recruited participants for in-depth interviews from other models apart from those selected for the focus group discussions to confirm the themes identified were not unique to those patients sampled for the focus group discussions.

Interviews were conducted once-off; therefore, we could not explore the patients’ experiences prospectively, which could capture how individuals’ experiences and perceptions change (or not) over time. These findings, therefore, represent the cross-sectional experiences of the people living with HIV using models in the specific context. We provided extensive and/or comprehensive quotations in reporting our results to illustrate the comparative perspectives and experiences of the participants in the different models while illustrating the analysis process (Eldh et al., 2020).

Excluding people who had dropped out of models is a limitation as this comparison could have offered potential negative experiences for each of the models. Their contribution might have provided other insights such as how the models did not work for them and what could have been done differently.

The National Health Services’ Patient Experience Framework facilitated the comparative thematic analysis as it guided and streamlined the different aspects of patient experience and the patients’ perspectives on these different modalities. Although the different modalities of the National Health Services’ Patient Experience Framework offered us the opportunity to streamline the comparison, we found that there were some overlaps across some of the framework’s modalities. This overlap is reflected in our data presentation and discussions.

Conclusions

The findings in this study highlight that patients found models easily accessible and convenient and overall had positive experiences aligning to the National Health Services’ Patient Experience Framework patients experience principles. Facility and community adherence clubs especially addressed most of the attributes of patient-centeredness, but the quick pick-up model falls short on some of the attributes. These findings can inform the roll-out of relevant models to accommodate the preferences of people living with HIV in different settings. Comparative quantitative studies of the different models can shed light on the impact of patients’ experiences and preferences on their retention in care and adherence to medication behaviors.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-qhr-10.1177_10497323211050371 for Comparing Patients’ Experiences in Three Differentiated Service Delivery Models for HIV Treatment in South Africa by Ferdinand C. Mukumbang, Sibusiso Ndlovu and Brian van Wyk in Qualitative Health Research

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-2-qhr-10.1177_10497323211050371 for Comparing Patients’ Experiences in Three Differentiated Service Delivery Models for HIV Treatment in South Africa by Ferdinand C. Mukumbang, Sibusiso Ndlovu and Brian van Wyk in Qualitative Health Research

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge all the patients who took part in the study.

Author Biographies

Ferdinand C. Mukumbang is an Acting Assistant Professor at the Department of Global Health, School of Medicine, the University of Washington in Seattle. He is a Public Health Scientist specializing in health policy and systems research with a focus on Implementation Sciences. He obtained his Ph.D. in Public Health in 2018 from the School of Public Health, University of the Western Cape, South Africa. He is particularly interested in the development and adoption of Critical Realist research methods for evidence-based theorizing in health care and global health.

Sibusiso Ndlovu is a Public Health Professional working as Health Promotion Lead with Medecins Sans Frontiers (MSF)/Doctors Without Borders Migrant Project in Tshwane, South Africa. She holds an MPH qualification from the University of the Western Cape and another Master's degree in Social Development majoring in Community Development from the University of Cape Town. Her interests are Health Systems Strengthening and Community Development and Engagement.

Brian van Wyk is a Professor in Public Health at the University of the Western Cape in South Africa. He is a social scientist with a DPhil in Psychology. His research interests are in HIV/AIDS and health systems research. Current research projects investigate treatment outcomes of adolescents on antiretroviral therapy, particularly looking at developing guided transition protocols and psychosocial support interventions to improve mental wellness, adherence, retention in care, and viral suppression in this key population.

Authors’ contributions: FCM: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, and Writing - Original draft preparation. SN: Investigation, Data curation, and Writing - Original draft preparation. BvW: Supervision, Validation, and Editing

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Data Availability: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental Material for this article is available online at journals.sagepub.com/home/qhr/10.1177/10497323211050371

ORCID iD

Ferdinand C. Mukumbang https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1441-2172

References

- Agaba P. A., Genberg B. L., Sagay A. S., Agbaji O. O., Meloni S. T., Dadem N. Y., Kolawole G. O., Okonkwo P., Kanki P. J., Ware N. C. (2018). Retention in differentiated care: Multiple measures analysis for a decentralized HIV care and treatment program in North Central Nigeria. Journal of AIDS & clinical research, 9(2), 1–18. 10.4172/2155-6113.1000756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azia I. N., Mukumbang F. C., Van Wyk B. (2016). Barriers to adherence to antiretroviral treatment in a regional hospital in Vredenburg, Western Cape, South Africa. Southern African Journal of HIV Medicine, 17(1), 476. 10.4102/sajhivmed.v17i1.476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsey M. A. (2005). AIDS and the family: Policy options for a crisis in family capital. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, UNAIDS. http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/family/Publications/belsey/FINAL REPORT - BELSEY’S HIV REPORT (PDF).pdf [Google Scholar]

- Boeije H. (2002). A purposeful approach to the constant comparative method in the analysis of qualitative interviews. Quality and Quantity, 36(4), 391–409. 10.1023/A:1020909529486 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw C., Atkinson S., Doody O. (2017). Employing a qualitative description approach in health care research. Global Qualitative Nursing Research, 4(1), 2333393617742282. 10.1177/2333393617742282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broom A. (2021). Conceptualizing qualitative data. Qualitative Health Research, 31(10) 1767–1770. 10.1177/10497323211024951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health . (2011). NHS Patient experience framework. Department of Health; (Issue 17273) https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/215159/dh_132788.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health . (2016). Adherence Guidelines for HIV, TB and NCDs | 1 Policy and service delivery guidelines for linkage to care, adherence to treatment and retention in care. http://www.nacosa.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Integrated-Adherence-Guidelines-NDOH.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Dudhia R., Kagee A. (2015). Experiences of participating in an antiretroviral treatment adherence club. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 20(4), 488–494. 10.1080/13548506.2014.953962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncombe C., Rosenblum S., Hellmann N., Holmes C., Wilkinson L., Biot M., Bygrave H., Hoos D., Garnett G. (2015). Reframing HIV care: Putting people at the centre of antiretroviral delivery. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 20(4), 430–447. 10.1111/tmi.12460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldh A. C., Årestedt L., Berterö C. (2020). Quotations in qualitative studies: Reflections on constituents, custom, and purpose. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19(1), 1-6. 10.1177/1609406920969268. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eshun-Wilson I., Mukumbwa-Mwenechanya M., Kim H.-Y., Zannolini A., Mwamba C. P., Dowdy D., Kalunkumya E., Lumpa M., Beres L. K., Roy M., Sharma A., Topp S. M., Glidden D. V., Padian N., Ehrenkranz P., Sikazwe I., Holmes C. B., Bolton-Moore C., Geng E. H. (2019). Differentiated care preferences of stable patients on antiretroviral therapy in Zambia: A discrete choice experiment. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 81(5), 540–546. 10.1097/qai.0000000000002070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flämig K., Decroo T., van den Borne B., van de Pas R. (2019). ART adherence clubs in the Western Cape of South Africa: What does the sustainability framework tell us? A scoping literature review. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 22(3), e25235. 10.1002/jia2.25235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimsrud A., Bygrave H., Doherty M., Ehrenkranz P., Ellman T., Ferris R., Ford N., Killingo B., Mabote L., Mansell T., Reinisch A., Zulu I., Bekker L.-G. (2016). Reimagining HIV service delivery: The role of differentiated care from prevention to suppression. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 19(1), 21484. 10.7448/IAS.19.1.21484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heestermans T., Browne J. L., Aitken S. C., Vervoort S. C., Klipstein-Grobusch K. (2016). Determinants of adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-positive adults in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. BMJ Global Health, 1(4), e000125. http://gh.bmj.com/content/1/4/e000125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International AIDS Society . (2016). Differentiated care for HIV: A decision framework for antiretroviral therapy. http://www.differentiatedcare.org/Portals/0/adam/Content/yS6M-GKB5EWs_uTBHk1C1Q/File/Decision Framework.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Jones L. (2004). The role of the physical environment in delivering better health care. Practice Development in Health Care, 3(4), 234–237. 10.1002/pdh.160 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan S. R., Oosthuizen C., Stinson K., Little F., Euvrard J., Schomaker M., Osler M., Hilderbrand K., Boulle A., Meintjes G. (2017). Contemporary disengagement from antiretroviral therapy in Khayelitsha, South Africa: A cohort study. PLoS Medicine, 14(11), e1002407. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight L., Schatz E., Mukumbang F. C. (2018). “I attend at Vanguard and i attend here as well”: Barriers to accessing healthcare services among older South Africans with HIV and non-communicable diseases 11 Medical and Health Sciences 1117 Public Health and Health Services. International Journal for Equity in Health, 17(1), 147. 10.1186/s12939-018-0863-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwarisiima D., Kamya M. R., Owaraganise A., Mwangwa F., Byonanebye D. M., Ayieko J., Plenty A., Black D., Clark T. D., Nzarubara B., Snyman K., Brown L., Bukusi E., Cohen C. R., Geng E. H., Charlebois E. D., Ruel T. D., Petersen M. L., Havlir D., Jain V. (2017). High rates of viral suppression in adults and children with high CD4+ counts using a streamlined ART delivery model in the SEARCH trial in rural Uganda and Kenya. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 20(S4), 21673. 10.7448/IAS.20.5.21673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez K. A., Willis D. G. (2004). Descriptive versus interpretive phenomenology: Their contributions to nursing knowledge. Qualitative Health Research, 14(5), 726–735. 10.1177/1049732304263638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luque-Fernandez M. A., Van Cutsem G., Goemaere E., Hilderbrand K., Schomaker M., Mantangana N., Mathee S., Dubula V., Ford N., Hernán M. A., Boulle A. (2013). Effectiveness of patient adherence groups as a model of care for stable patients on antiretroviral therapy in Khayelitsha, Cape Town, South Africa. PLoS ONE, 8(2), e56088. 10.1371/journal.pone.0056088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor H., McKenzie A., Jacobs T., Ullauri A. (2018). Scaling up ART adherence clubs in the public sector health system in the Western Cape, South Africa: A study of the institutionalisation of a pilot innovation. Globalization and Health, 14(1), 40. 10.1186/s12992-018-0351-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malterud K., Siersma V. D., Guassora A. D. (2016). Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies. Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1753–1760. 10.1177/1049732315617444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannell J., Cornish F., Russell J. (2014). Evaluating social outcomes of HIV/AIDS interventions: A critical assessment of contemporary indicator frameworks. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 17(1), 19073. 10.7448/IAS.17.1.19073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesic A., Fontaine J., Aye T., Greig J., Thwe T. T., Moretó-Planas L., Kliesckova J., Khin K., Zarkua N., Gonzalez L., Guillergan E. L., O’Brien D. P. (2017). Implications of differentiated care for successful ART scale-up in a concentrated HIV epidemic in Yangon, Myanmar. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 20(Suppl 4), 21644. 10.7448/IAS.20.5.21644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MSF (2014). Art adherence club report and toolkit. Doctors Without Borders, pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Mukumbang F. C. (2021). Leaving no Man behind: How differentiated service delivery models increase Men’s engagement in HIV care. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 10(3), 129–140. 10.34172/IJHPM.2020.32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukumbang F. C., Marchal B., Van Belle S., van Wyk B. (2018. a). Patients are not following the [adherence] club rules anymore”: A realist case study of the antiretroviral treatment adherence club, South Africa. Qualitative Health Research, 28(12), 1839-1857. 10.1177/1049732318784883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukumbang F. C., Marchal B., Van Belle S., Van Wyk B. (2018. b). A realist approach to eliciting the initial programme theory of the antiretroviral treatment adherence club intervention in the Western Cape Province, South Africa. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 47. 10.1186/s12874-018-0503-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukumbang F. C., Orth Z., Van Wyk B. (2019). What do the implementation outcome variables tell us about the scaling-up of the antiretroviral treatment adherence clubs in South Africa? A document review. Health Research Policy and Systems, 17(1), 28. 10.1186/s12961-019-0428-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukumbang F. C., Van Belle S., Marchal B., van Wyk B. (2016). Towards developing an initial programme theory: Programme designers and managers assumptions on the antiretroviral treatment adherence club programme in primary health care facilities in the metropolitan area of western cape province, South Africa. PLoS One, 11(8), e0161790. 10.1371/journal.pone.0161790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukumbang F. C., Van Belle S., Marchal B., van Wyk B. (2017). Exploring ‘generative mechanisms’ of the antiretroviral adherence club intervention using the realist approach: A scoping review of research-based antiretroviral treatment adherence theories. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 385. 10.1186/s12889-017-4322-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukumbang F. C., van Wyk B., Van Belle S., Marchal B. (2019). Unravelling how and why the Antiretroviral Adherence Club Intervention works (or not) in a public health facility: A realist explanatory theory-building case study. PLos One, 14(1), e0210565. 10.1371/journal.pone.0210565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantelic M., Stegling C., Shackleton S., Restoy E. (2018). Power to participants: a call for person-centred HIV prevention services and research. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 21(S7), e25167. 10.1002/jia2.25167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prust M. L., Banda C. K., Nyirenda R., Chimbwandira F., Kalua T., Jahn A., Eliya M., Callahan K., Ehrenkranz P., Prescott M. R., McCarthy E. A., Tagar E., Gunda A. (2017). Multi-month prescriptions, fast-track refills, and community ART groups: results from a process evaluation in Malawi on using differentiated models of care to achieve national HIV treatment goals. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 20(Suppl 4), 21650. 10.7448/IAS.20.5.21650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punsalan T., Uriarte G. (1987). Statistics: a Simplified Approach. In Ochave J. A., Seville C. G. (Ed.), (1st ed.). Rex Book Store. [Google Scholar]

- Reda A. A., Biadgilign S. (2012). Determinants of adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected patients in Africa. AIDS Research and Treatment, 2012(574656), 1–8. 10.1155/2012/574656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Root R., Whiteside A. (2013). A qualitative study of community home-based care and antiretroviral adherence in Swaziland. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 16(1), 17978. 10.7448/IAS.16.1.17978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seekings J. (2013). Economy, society and municipal services in Khayelitsha. https://s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3.sourceafrica.net/documents/14388/10-b-professor-jeremy-seekings-affidavit.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Sharer M., Davis N., Makina N., Duffy M., Eagan S. (2019). Differentiated antiretroviral therapy delivery: Implementation barriers and enablers in South Africa. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 30(5), 511–520. 10.1097/JNC.0000000000000062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shubber Z., Mills E. J., Nachega J. B., Vreeman R., Freitas M., Bock P., Nsanzimana S., Penazzato M., Appolo T., Doherty M., Ford N. (2016). Patient-reported barriers to adherence to antiretroviral therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine, 13(11), e1002183. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. A. (2018). “Yes it is phenomenological”: A reply to Max Van Manen’s Critique of interpretative phenomenological analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 28(12), 1955–1958. 10.1177/1049732318799577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trafford Z., Gomba Y., Colvin C. J., Iyun V. O., Phillips T. K., Brittain K., Myer L., Abrams E. J., Zerbe A. (2018). Experiences of HIV-positive postpartum women and health workers involved with community-based antiretroviral therapy adherence clubs in Cape Town, South Africa. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 935. 10.1186/s12889-018-5836-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsondai P. R., Wilkinson L. S., Grimsrud A., Mdlalo P. T., Ullauri A., Boulle A. (2017). High rates of retention and viral suppression in the scale-up of antiretroviral therapy adherence clubs in Cape Town, South Africa. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 20(Suppl 4), 21649. 10.7448/IAS.20.5.21649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tufford L., Newman P. (2012). Bracketing in qualitative research. Qualitative Social Work, 11(1), 80–96. 10.1177/1473325010368316 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tun W., Apicella L., Casalini C., Bikaru D., Mbita G., Jeremiah K., Makyao N., Koppenhaver T., Mlanga E., Vu L. (2019). Community-based antiretroviral therapy (ART) delivery for female sex workers in Tanzania: 6-Month ART initiation and adherence. AIDS and Behavior, 23(Suppl 2), 142–152. 10.1007/s10461-019-02549-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unaids (2014). Treatment 2015. Unaids, p. 44. www.unaids.org/.../unaids/.../2013/gr2013/UNAIDS_Treatment _2015 [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS (2016). Global AIDS update 2016. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/global-AIDS-update-2016_en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS (2020). HIV testing and treatment cascade. Country Factsheets. https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/southafrica. [Google Scholar]

- Van Manen M. (2017). But is it phenomenology? Qualitative Health Research, 27(6), 775–779. 10.1177/1049732317699570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]