Introduction

Dychromatosis universalis heredetaria (DUH) is a rare genodermatosis that was first reported by Ichikawa and Hiraga1 in 1933. The disorder was reported initially and mainly in Japan, but has also been reported in India, South Africa, Saudi Arabia, and Iraq.2,3 Clinically, DUH is characterized by generalized mottled hyperpigmented and hypopigmented macules, commonly affecting the trunk and face, but rarely found over palms, soles, and mucous membranes.3 Although the mode of inheritance in most cases is autosomal dominant,3 autosomal recessive3 and sporadic incidence4 cases have been reported. The ABCB6 gene regulates the early steps of melanosome biogenesis, and mutation in the ABCB6 gene in the 2q33.3-q36.1 region is responsible for DUH.5,6 Here we describe 2 new cases of DUH in a Saudi mother and her son associated with a novel mutation (c.1144G>A; p.G382R) in the ABCB6 gene.

Case reports

Case 1

The mother is a 30-year-old woman. She has 6 siblings. Her parents were nonconsanguineous, and by history, neither of her parents appeared to be affected by DUH; however, 1 sister was recently diagnosed with the same condition. She married her first-degree cousin with no similar skin lesions. She presented with asymptomatic hypopigmented and hyperpigmented macules that first appeared in childhood on the chest and progressively extended to the trunk, then all over her body, including the face. Cutaneous examination showed diffuse hyperpigmented and hypopigmented macules with a mottled appearance, distributed symmetrically over her face, trunk, and extremities with normal palms and soles. Hair, nails, and mucosa were not involved. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

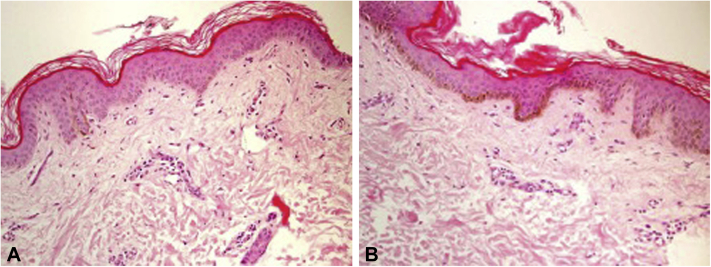

A, Photomicrograph from hypopigmented area revealing a marked decrease in melanin pigmentation in the basal layer; mild hyperkeratosis is also noted (hematoxylin-eosin stain; original magnification: ×200). B, Photomicrograph from the hyperpigmented area revealing a marked increase in melanin pigmentation in the basal layer (hematoxylin-eosin stain; original magnification: ×200).

Two punch biopsies from the abdomen, measuring 0.3 × 0.2 cm, were taken from the hypopigmented and hyperpigmented macules respectively. The hyperpigmented macule showed basal layer hyperpigmentation, whereas the hypopigmented macule showed decreased basal layer pigmentation. Both showed mild perivascular dermal lymphocytic infiltration with occasional melanophages (Fig 2, A and B).

Fig 2.

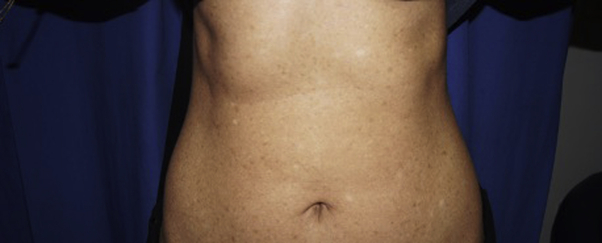

Diffuse hyperpigmented and hypopigmented macules with a mottled appearance over the abdomen and back.

Case 2

Her only child, a 13-year-old boy, presented with similar skin lesions, which initially appeared during his first 3 years of life over the inner thighs and progressed to the trunk and forehead. He was the product of an uneventful pregnancy with no perinatal complications. Cutaneous examination demonstrated diffuse hyperpigmented and hypopigmented macules with a mottled appearance, distributed symmetrically over the trunk, lower extremities, not involving his upper extremities, palms, or soles. Hair, nail, and mucosa were all spared. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable (Fig 3).

Fig 3.

Diffuse hyperpigmented and hypopigmented macules with a mottled appearance over the abdomen.

After obtaining written informed consent from the parents, blood samples were obtained from the 2 patients (mother and son). A novel heterozygous mutation (c.1144G>A; p.G382R) in the ABCB6 gene (Langereis blood group) was identified in both the mother and her son. This mutation resulted in a substitution of in a nonpolar glycine to a polar arginine in codon 382 (exon 5) of the ABCB6 gene.

Discussion

DUH is a rare heterogeneous pigmentary genodermatosis characterized by generalized asymptomatic hypopigmented and hyperpigmented macules that vary in size with a reticulated pattern appearing in early childhood or infancy, mainly over trunk and extremities, while face, palms, soles, nail, hair, and mucous membranes are less affected.3 Ocular abnormalities, such as photosensitivity, neurosensory hearing defects, learning difficulties, mental retardation, and epilepsy have been rarely reported to be associated with DUH.3,7

DUH is generally autosomal dominant with variable penetrance, but autosomal recessive and sporadic cases have been described.7,8

The histopathologic features depend upon the location from which the skin is biopsied. Hyperpigmented lesions will show an increase in melanin in the basal layer, pigmentary incontinence, and some melanophages in the upper dermis. In contrast, hypopigmented lesions exhibit decreased melanin deposition in the basal layer. As seen on electron microscopy, the number of melanosomes in melanocytes and keratinocytes is significantly reduced in hypopigmented lesions compared with hyperpigmented lesions and normal skin.6,9

ABCB6 belongs to the family of adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette transporters, which transport various molecules across extracellular and intracellular membranes.6 The ABCB6 gene is located either on 6q242-q252 or 12q21-q23, is expressed in lysosomes and early melanosomes of melanocytes, and regulates the early steps of melanogenesis.6 Downregulation of ABCB6 can impair the formation of luminal fibrils derived from the pigment cell-specific pre-melanosomal protein, most likely due to abnormalities in copper homeostasis.6

The human ABCB6 gene (OMIM 605452) was first cloned in the year 2000 and is located on chromosome 2q36. The ABCB6 gene contains 19 exons in the protein-coding region and belongs to the ABC transporter family. ABCB6 is involved in the active transport of peptides, steroids, polysaccharides, amino acids, phospholipids, ions, bile acids, and pharmaceutical drugs.

Possible differential diagnoses for similar skin lesions include dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditary, xeroderma pigmentosum, dyskeratosis congenita, and other reticulate pigmentary disorders.10 DUH clinically resembles xeroderma pigmentosum in its presentation. However, in DUH, lesions are generalized rather than being limited to photo-exposed areas. Moreover, the lesions show no atrophy or telangiectasia. The lesions also run a benign course with neither progression nor spontaneous regression with age.10

Currently, there is no effective treatment for skin pigmentary changes in DUH, but Q-switched alexandrite laser treatment can be used for hyperpigmented lesions, especially for exposed areas (eg, the face and hands).11

In conclusion, we report 2 family members who were affected by DUH with a novel heterozygous mutation (c.1144G>A; p.G382R) in the ABCB6 (Langereis blood group). This mutation resulted in a substitution of a nonpolar amino acid (glycine) with a polar amino acid (arginine) in codon 382 within exon 5 of the ABCB6 gene.

Conflicts of interest

None disclosed.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the family members for their participation.

Footnotes

Funding sources: None.

IRB approval status: Not applicable.

References

- 1.Ichigawa T., Hiraga Y. A previously undescribed anomaly of pigmentation dyschromatosisuniversalishereditaria. Jpn J Dermatol Urol. 1933;34:360–364. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yusuf S.M., Mijinyawa M.S., Maiyaki M.B., Mohammed A.Z. Dyschromatosis universalis hereditaria in a young Nigerian female. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48(7):749–750. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.03290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sethuraman G., Srinivas C.R., D'Souza M., Thappa D.M., Smiles L. Dyschromatosis universalis hereditaria. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27(6):477–479. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2002.01129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manchanda S., Arora R., Lingaraj M.M. Sporadic dyschromatosis universalis hereditaria: a rare case report. Indian J Paediatr Dermatol. 2017;18(1):43–45. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang C., Li D., Zhang J., et al. Mutations in ABCB6 cause dyschromatosis universalis hereditaria. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133(9):2221–2228. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergam P., Reisecker J.M., Rakvács Z., et al. ABCB6 resides in melanosomes and regulates early steps of melanogenesis required for PMEL amyloid matrix formation. J Mol Biol. 2018;430(20):3802–3818. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2018.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bukhari I.A., El-Harith E.A., Stuhrmann M. Dyschromatosis universalis hereditaria as an autosomal recessive disease in five members of one family. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20(5):628–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cui Y.X., Xia X.Y., Zhou Y., et al. Novel mutations of ABCB6 associated with autosomal dominant dyschromatosis universalis hereditaria. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e79808. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta A., Sharma Y., Dash K.N., Verma S., Natarajan V.T., Singh A. Ultrastructural investigations in an autosomal recessively inherited case of dyschromatosis universalis hereditaria. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95(6):738–740. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang J., Li M., Yao Z. Updated review of genetic reticulate pigmentary disorders. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177(4):945–959. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nogita T., Mitsuhashi Y., Takeo C., Tsuboi R. Removal of facial and labial lentigines in dyschromatosis universalis hereditaria with a Q-switched alexandrite laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(2):e61–e63. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]