Abstract

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) has emerged as an intractable cancer with scanty therapeutic regimens. The aberrant activation of Yes-associated protein (YAP) and transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding motif (TAZ) are reported to be common in CCA patients. However, the underpinning mechanism remains poorly understood. Deubiquitinase (DUB) is regarded as a main orchestrator in maintaining protein homeostasis. Here, we identified Josephin domain-containing protein 2 (JOSD2) as an essential DUB of YAP/TAZ that sustained the protein level through cleavage of polyubiquitin chains in a deubiquitinase activity-dependent manner. The depletion of JOSD2 promoted YAP/TAZ proteasomal degradation and significantly impeded CCA proliferation in vitro and in vivo. Further analysis has highlighted the positive correlation between JOSD2 and YAP abundance in CCA patient samples. Collectively, this study uncovers the regulatory effects of JOSD2 on YAP/TAZ protein stabilities and profiles its contribution in CCA malignant progression, which may provide a potential intervention target for YAP/TAZ-related CCA patients.

KEY WORDS: Cholangiocarcinoma, Deubiquitinase, JOSD2, YAP/TAZ

Abbreviations: CCA, cholangiocarcinoma; DAB, 3,3-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride chromogen; DUB, deubiquitinase; FGFR, fibroblast growth factor receptor; FOLFOX, folinic acid, 5-FU and oxaliplatin; IDH1/2, isocitrate dehydrogenase 1/2; IHC, immunohistochemistry; IP, immunoprecipitation; KRAS, kirsten rat sarcoma 2 viral oncogene homolog; LATS1/2, large tumor suppressor kinase 1/2; MST1/2, mammalian Ste20-like kinases 1/2; OTUB2, otubain-2; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; PDC, patient derived cell; PDX, patient-derived xenograft; rhJOSD2, recombinant human JOSD2; RTV, relative tumor volume; shRNA, specific hairpin RNA; SRB, sulforhodamine B; TAZ, transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding motif; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; USP9X/10/47, ubiquitin-specific peptidase 9X/10/47; YAP, Yes-associated protein; YOD1, ubiquitin thioesterase OTU1

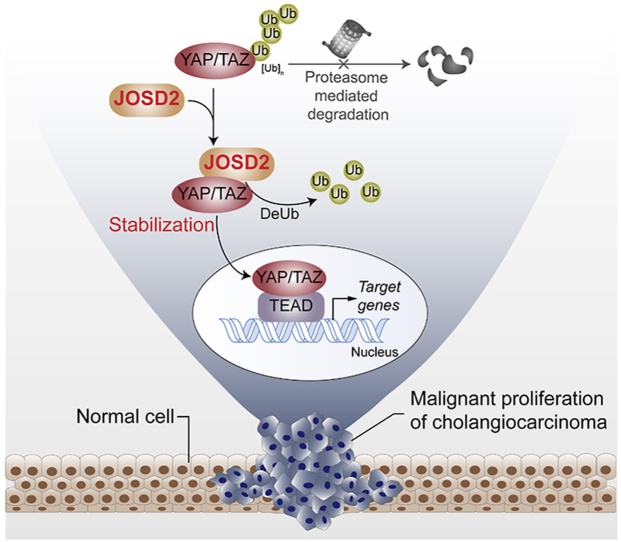

Graphical abstract

JOSD2, a deubiquitinating enzyme, increases YAP/TAZ abundance and reinforces their signaling through the cleavage of polyubiquitin chains, observably contributing to cholangiocarcinoma progression.

1. Introduction

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) is a heterogeneous malignancy with features of cholangiocyte differentiation and has been regarded as the second most common primary hepatic malignancy1. The silent presentation, aggressive nature and highly resistance to chemotherapy have brought a globally increasing incidence and mortality of this complicated and fatal cancer type over the past few decades1, 2, 3. About 70% patients are diagnosed at late stages, preventing curative surgery and considering as a contraindication for liver transplantation2. For those unresectable patients, multiple researches have emphasized the use of cisplatin and gemcitabine chemotherapy as first-line regimen. However, the median overall survival is still less than 1 year, showing limited effectiveness2. More intensive triple–chemotherapy combinations have been explored such as FOLFOX (folinic acid, 5-FU and oxaliplatin), but the result is also disappointing1,4. Therefore, the exploration and identification of the key regulators essential for CCA are urgently needed, to develop effective anti-CCA therapies.

Accumulating data have implicated that, two critical downstream effectors of the Hippo pathway, Yes-associated protein (YAP) and transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding motif (TAZ), play fundamental roles in the pathogenesis of multiple devastating malignancies, including CCA5, 6, 7, 8. Acting as transcriptional cofactors, YAP/TAZ translocate into nucleus and bind to transcriptional enhancer factor family protein to enhance the transcription of proliferation-, differentiation- and stemness-related genes. YAP/TAZ are phosphorylated by mammalian Ste20-like kinases 1/2 (MST1/2) and large tumor suppressor kinase 1/2 (LATS1/2) serine kinase cascades, then restrained in the cytosol by 14-3-3 and E3 ligase SCFβ−TRCP, then subjected to their ubiquitination and ultimate proteasomal degradation9. In spite of the rare mutation of Hippo components, YAP/TAZ is yet aberrantly activated in most CCA patient, with the mechanisms poorly defined10, 11, 12. Meanwhile, downregulation of YAP/TAZ by lentivirus in vitro is reported to be effectively alleviate CCA cell proliferation7. However, YAP/TAZ are technically challenging to be directly targeted, since these two transcriptional coactivators have no active pockets for small molecule compounds13. Therefore, it gives rise to the necessity to study posttranslational modifications of YAP/TAZ and explore potential targets13,14.

Deubiquitinases (DUBs) which catalyze the removal of ubiquitin chains from their protein substrates, play essential roles in regulating protein ubiquitination and maintaining protein homeostasis. Recently, DUBs have been emerging as appealing drug targets for cancer therapy, not only due to the frequently dysregulated ubiquitination level of a variety of oncoproteins, but also owing to their well-clarified crystal structures and targetable catalytic clefts15, 16, 17. Nevertheless, except some studies reveal that loss of BRCA1-associated protein 1 expression coincides with CCA, the roles of DUBs in CCA progression have remained largely unknown18,19. Therefore, identification of the oncogenic DUBs would contribute to the mechanistic understanding and therapeutic regulation of elevated YAP/TAZ activity in CCA.

Here in this study, we identified an uncharacterized deubiquitinase Josephin domain-containing protein 2 (JOSD2) as a positive upstream regulator of YAP/TAZ which removes the poly-ubiquitin chains and leads to the protein stabilization of YAP/TAZ, thus reinforce their tumor-promoting function in CCA. Inhibition of JOSD2 exerted potent anti-CCA effects both in vitro and in vivo. Meanwhile, a high correlation between YAP and JOSD2 protein level was observed in CCA clinical samples, and the increased expression of JOSD2 predicted poor prognosis of CCA patients. Our finding provides a novel mechanism underlying the aberrant activation of YAP/TAZ in CCA, which may offer a feasible therapeutic target for CCA treatment.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture

Human embryonic kidney HEK293T cells and human CCA cell line RBE were obtained from the Cell Bank of Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). Human CCA cell lines CCLP-1 and HuCCT-1 were purchased from Beina Chuanglian Biotechnology (Beijing) Institute and GuangZhou Jennio Biotech (Guangzhou, China) respectively. All the cells were cultured in DMEM or PRMI-1640 medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) separately supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) at 37 °C, in 5% CO2 humid atmosphere. The cell lines were monitored for mycoplasma contamination ever six months.

2.2. Gene transfection

To transiently overexpress the protein of interested, the plasmids were transfected into cells by jetPRIME (#114-15, Polyplus, Strasbourg, France) according to the manufacture's recommendation. Empty vector was introduced as a negative control.

For stable overexpression or silence of interest genes, the lentivirus stocks were produced as described before20. The lentiviral vector pCDHEF1-Puro plasmid and specific hairpin RNA (shRNA) vectors pLKO.1 were obtained from Addgene (Watertown, MA, USA) and the targeted fragments or gene-specific shRNAs were cloned into pCDH-EF1-Puro plasmid by CloneEZ PCR Cloning Kit (GeneScript, Nanjing, China). The targeting sequences of shRNA used in this study were as follows:

shRNA-YAP#1: CCCAGTTAAATGTTCACCAAT;

shRNA-YAP#2: GCCACCAAGCTAGATAAAGAA;

shRNA-TAZ#1: GCGTTCTTGTGACAGATTATA;

shRNA-TAZ#2: GCGATGAATCAGCCTCTGAAT;

shRNA-JOSD2#1: CCAGGTGGACGGTGTCTACTA;

shRNA-JOSD2#2: CACCGGCAACTATGATGTCAA.

2.3. Plasmids, reagents and antibodies

The 8 × GTIIC-Luc plasmid was purchased from Addgene. The pCDNA3.0-WWTR1-Luc plasmid was cloned as described21. Primary antibodies used for immunoblotting were as follows: YAP/TAZ (#8418), β-TRCP (#4394) antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA); anti-YAP (#A1002) antibody was from ABclonal (Wuhan, China); anti-cullin1 (#sc-11384) antibody was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA); anti-JOSD2 (#SAB2103354) was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA); anti-Myc (#db457), anti-GAPDH (#db106) and anti-HA (#db2603) antibodies were purchased from Diagbio (Hangzhou, China). The anti-FLAG resin beads (#L00425), anti-HA magnetic beads (#B26202) and SureBeads™ Protein G (#161-4023) for immunoprecipitation (IP) were obtained from GenScript (Nanjing, China), Biomake (Houston, TX, USA) and Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA, USA), respectively. For immunofluorescence, DAPI (#EF704) and secondary antibody (#A21206 and #A0037) were purchased from Dojindo Molecular Technologies (Tokyo, Japan) and Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA) respectively. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) analyses were completed by using anti-JOSD2 antibody (#orb184482) obtained from Biorbyt (Cambridge, UK) and anti-Ki67 antibody (#sc-23900) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (PV-6001) and 3,3-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride chromogen (DAB) kit (#ZLI-9018) for IHC were purchased from ZSGB-BIO company (Beijing, China). Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (#E1960) was obtained from Promega (Madison, WI, USA). Protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX), proteasome inhibitor MG132 and DUBs inhibitor PR-619 were obtained from Selleck Chem (Houston, TX, USA).

2.4. Immunohistochemistry

Tissue microarrays were purchased from Liaoding (Shanghai, China). The microarrays and paraffin section were first de-paraffinized and immersed for 5 min in PBS three times. The sections were heated in microwave oven for 5 min in citrate antigen retrieval buffer for 3 times, followed by endogenous peroxidase activity blocking with 3% H2O2 and non-specific staining blocking with 10% goat serum20. The sections were subsequently incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C (JOSD2 and YAP were 1:200 diluted, Ki67 was 1:100 diluted) and treated for 30 min with indicated second antibodies, respectively. The sections were then exposed for 1.5 min to DAB and rinsed off in deionized water to terminate DAB reaction. The evaluation of the IHC staining was performed as before21.

2.5. Real-time PCR

Cells harvested in TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) were carried out as described previously20. The sequences of primers were used as following:

Actin, forward primer: 5′-GGTCATCACTATTGGCAACG-3′,

Actin, reverse primer: 5′-ACGGATGTCAACGTCACACT-3′;

WWTR1, forward primer: 5′-ATCCCCAACAGACCCGTTTC-3′,

WWTR1, reverse primer: 5′-ACAGCCAGGTTAGAAAGGGC-3′;

YAP, forward primer: 5′-TAGCCCTGCGTAGCCAGTTA-3′,

YAP, reverse primer: 5′-TCATGCTTAGTCCACTGTCTGT-3′;

JOSD2, forward primer: 5′-CCCACCGTGTACCACGAAC-3′,

JOSD2, reverse primer: 5′-CTCCTGGCTAAAGAGCTGCTG-3′.

2.6. Recombinant protein purification

Recombinant human JOSD2 (rhJOSD2) with N-terminal GST-tag was transfected into Trans109 Chemically Competent Cell (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China). After inoculation, the bacterial cells were grown at 37 °C to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.4–0.6 OD value, and expression of the GST-fusion JOSD2 was induced by 300 μmol/L isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside (Selleck Chem, Houston, TX, USA) for 18 h at 25 °C. The bacterial cells were then spun down and resuspended in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with pH 7.4. Subsequently, the bacterial cells were sonicated and centrifuged to collect soluble fraction. GST-JOSD2 was purified using GSTrap™ HP columns (AKTA purifier; GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2.7. In vitro deubiquitination assay

Flag-tagged YAP and HA-tagged ubiquitin were transfected into 293T cells. After 24 h, cells were harvested and lysed by 4% SDS for immunoprecipitation with anti-DYKDDDDK IP resin beads. Subsequently, poly-ubiquitinated YAP protein was incubated with bacterial-expressed rhJOSD2 for 2 h at 37 °C. The buffer contains 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, 5 mmol/L MgCl2, 2 mmol/L DTT and 2 mmol/L ATP-Na2 with MG13221.

2.8. Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

The co-immunoprecipitation assay and immunoblotting was performed as described20. For endogenous immunoprecipitation, the HEK293T cell lysate was incubated with the anti-YAP or anti-TAZ antibodies coupled to G-sepharose beads at 4 °C overnight and analyzed by immunoblotting.

2.9. Immunofluorescence

CCLP-1, HuCCT-1 and Hela cells were plated in fluorescent chamber slides and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde 24 h later. The slides were washed by PBS for 5 min three times. Cells were permeabilized with blocking buffer (0.1% Triton-X100 in PBS) at room temperature for 30 min, then incubated with anti-YAP antibody (dilution rate 1:200) and/or anti-JOSD2 antibody (dilution rate 1:100) at 4 °C overnight. The slides were washed three times by PBS, and incubated with Alexa 488-conjugated and 568-conjugated secondary antibodies with 1:1000 dilution rate at room temperature for 1 h avoiding light. Followed by PBS washing three times and DAPI (1:5000 diluted in PBS) incubating at room temperature for 5 min. Ultimately, the slides were sealed with anti-fade reagent (#0100-01, SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, AL, USA) and observed by confocal microscope.

2.10. Cell proliferation and colony formation assay

HuCCT-1, RBE, CCLP-1 and patient derived cells (PDCs) infected scramble or shRNA lentivirus were seeded 1000/well in 96 well plates and the OD value was measured every day for 9 days. The fold change of cell proliferation on Day n was calculated as Eq. (1) by sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay:

| (1) |

The scramble or shRNA lentivirus infected cells were seeded 1000/well in 6 well plated for three weeks in colony formation assay. The cells were stained by SRB and dissolved by 1% Tris-base for quantification.

2.11. Antitumor activity in vivo

BALB/c nude mice (4–5 weeks old) were purchased from Zhejiang Chinese Medical University (Hangzhou, China) and maintained in a pathogen-free animal facility. 8.0 × 106 HuCCT-1 cells were suspended 1:1 in culture medium and Matrigel, then injected subcutaneously into the nude mouse. Subsequently, the tumor was inoculated in 16 mice evenly and randomized into indicated groups (8 animals/group). Intratumor injection of the scramble or shJOSD2 lentivirus were performed every two days. Tumor volume (V) was calculated as Eq. (2):

| (2) |

The animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Zhejiang University (Hangzhou, China) with the ethical approval number IACUC-s20-015.

2.12. Patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models

Tumors from CCA patients (P0) were fragmented and then subcutaneously transplanted into nude mice (P1) for engraftment. After grown, the tumors were subcutaneously transplanted into 16 nude mice as described21. Once the tumor volume reached about 50 mm3, mice were randomized into indicated groups (8 animals/group). Intratumor injection of the scramble or shJOSD2 lentivirus were performed every two days. Relative tumor volume (RTV) and therapeutic treatment effects (T/C) were calculated as previously described. The animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Zhejiang University (Hangzhou, China) with the ethical approval number IACUC-s20-037.

2.13. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SigmaPlot 10.0. Grayscale analysis and colocalization analysis were performed using ImageJ Fiji. Results determined from three independent experiments are presented as mean ± SD or mean ± SEM and two-tailed unpaired Student t tests were used for statistical analysis. Results are considered significant when P < 0.05 (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001)21.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of JOSD2 as a novel YAP/TAZ regulator in CCA

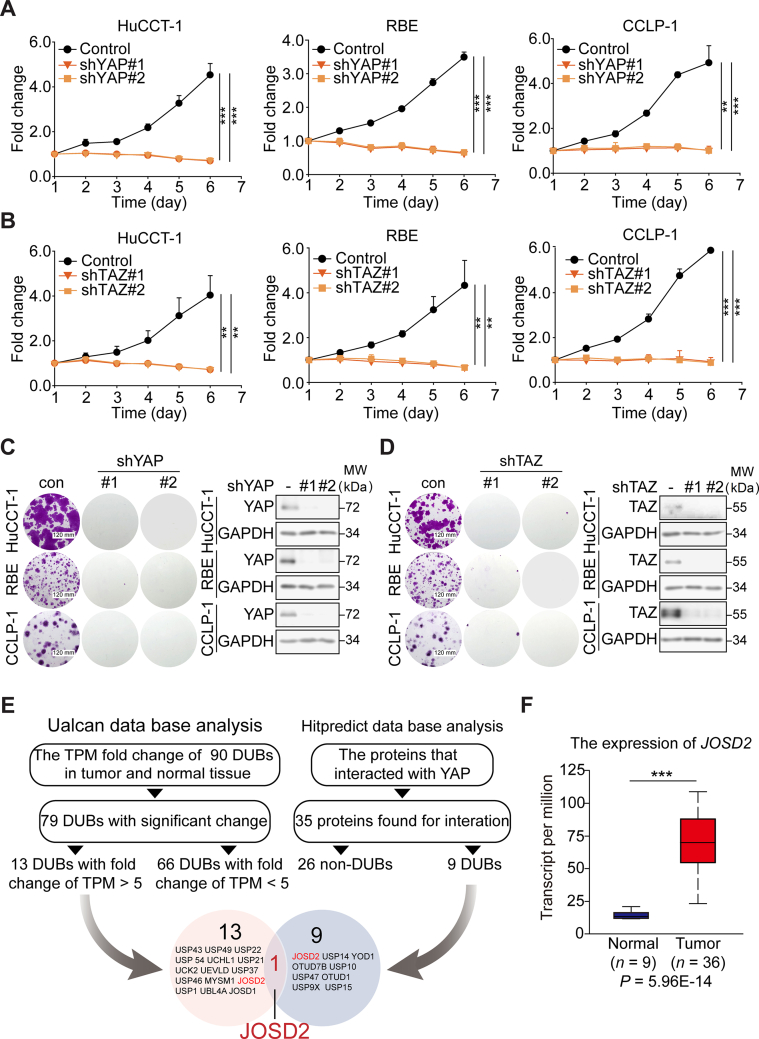

Some studies have pointed out the aberrant activation of YAP in CCA, indicating its pivotal role in tumor progression7,10,22. In this context, we firstly verified the consequence of YAP/TAZ depletion in three CCA cell lines (HuCCT-1, RBE, and CCLP-1). Using lentiviral infection, we established stable YAP or TAZ deficient cell clones. As measured by SRB assay and colony formation assay, the down regulation of YAP or TAZ evidently suppressed cell growth (Fig. 1A–D, Supporting Information Fig. S1A and S1B), which was in line with the previous studies7,12. As we aimed to explore a druggable regulator, namely, a DUB controlling the abundance of YAP/TAZ in CCA, database mining and analyses were utilized. We have compared the expression levels of 90 DUBs in CCA and normal tissues according to The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database (http://ualcan.path.uab.edu/analysis.html). As a result, 79 DUBs exhibited significant change of Transcripts Per Million (Supporting Information Table S1). In order to narrow down the scope of candidate DUBs, we focused on those top 13 DUBs with fold change greater than 5 (Fig. 1E). Meanwhile, Hitpredict data base, a confident resource of protein–protein interactions revealed 9 DUBs that interacted with YAP (http://www.hitpredict.org/htp_int.php?Value=9087). JOSD2, a member of Machado-Joseph Disease subfamily, stood out as the only candidate DUB casted in the overlay of aforementioned two analyses (Fig. 1E).

Figure 1.

JOSD2 is a new regulator of YAP/TAZ in CCA. YAP (A) or TAZ (B) silencing significantly impedes HuCCT-1, RBE and CCLP-1 cell proliferation as determined by SRB assay. These results represent the mean ± SD of three independent experiments; ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001. Knock-down of YAP (C) or TAZ (D) dramatically suppresses CCA colony formation as displayed by SRB assay. (E) The scheme for identification of JOSD2 as a candidate DUB of YAP in CCA. (F) JOSD2 expression level is significantly up-regulated in CCA tumor tissues; ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

Next, we sought to confirm the clinical significance of JOSD2 in CCA by using the TCGA database. As a result, most CCA samples exhibited markedly higher transcripts per million of JOSD2 than normal tissues (P < 0.001, Fig. 1F). Notably, the expression level of JOSD2 was correlated with the risk of CCA patients (P < 0.001, Fig. S1C). Furthermore, the JOSD2 expression level inversely correlated with the disease-free survival of CCA patients, highlighting the crucial role of JOSD2 in the malignant evolution of CCA (Fig. S1D).

These results collectively indicate that YAP/TAZ have critical roles in CCA proliferation and JOSD2 is a potential oncogenic DUB in YAP/TAZ-related CCA.

3.2. JOSD2 promotes CCA cells proliferation and stabilizes YAP/TAZ proteins

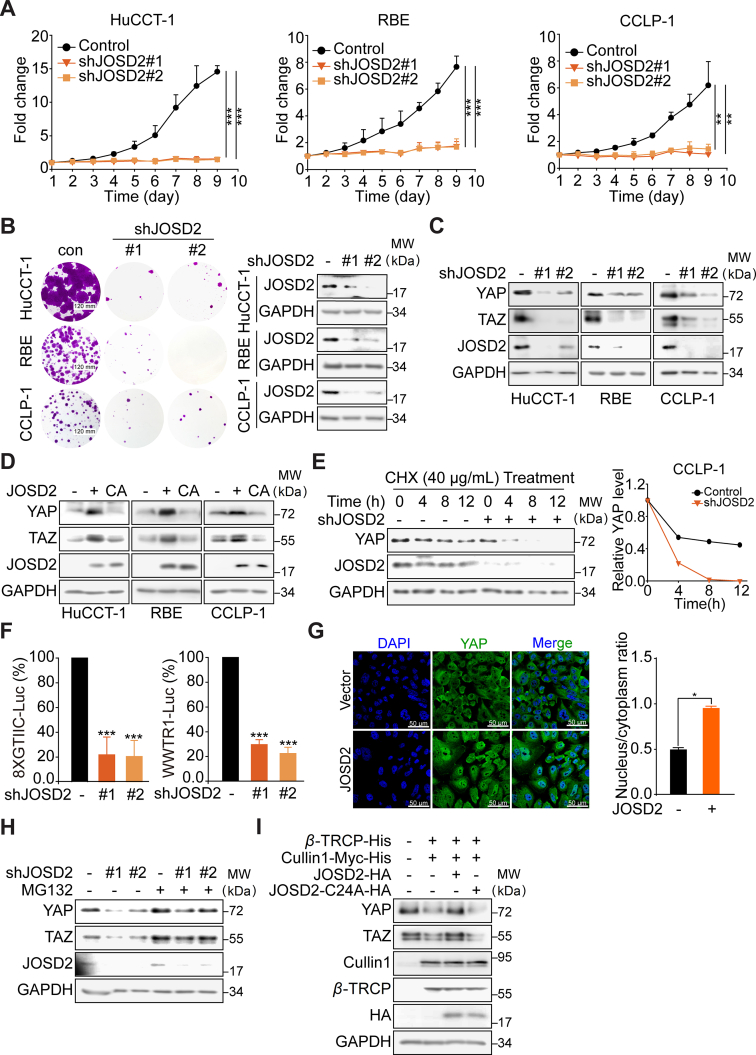

In order to further corroborate that JOSD2 indeed involved in the progress of CCA, we stably silenced JOSD2 in three CCA cell lines (HuCCT-1, RBE and CCLP-1, Fig. 2A). The depletion of JOSD2 significantly impaired the proliferation of CCA cells. Similar results were obtained in colony formation assay (Fig. 2B and Supporting Information Fig. S2A).

Figure 2.

JOSD2 plays vital role in CCA proliferation and stabilizes YAP/TAZ through deubiquitinase activity. The stably silence of JOSD2 remarkably inhibits CCA proliferation (A) and colony formation (B). The results represent the mean ± SD of three independent experiments; ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001. (C) Knockdown of JOSD2 down-regulates YAP and TAZ protein levels. (D) Over-expression of JOSD2-WT but not its catalytically inactive mutant JOSD2-C24A greatly increases YAP/TAZ protein levels. (E) Knockdown of JOSD2 dramatically decreases YAP/TAZ protein stability. The protein levels were quantified by Image J. (F) Silencing of JOSD2 in 293T cells distinctly reduces fluorescence signals in 8 × GTIIC-luciferase system (shJOSD2#1 inhibition ratio = 78.2%, shJOSD2#2 inhibition ratio = 79.5%) and WWTR-luciferase reporter system (shJOSD2#1 inhibition ratio = 70.3%, shJOSD2#2 inhibition ratio = 77.6%). The results represent the mean ± SD of three independent experiments; ∗∗∗P < 0.001. (G) Representative images of immunofluorescence with YAP in green and DAPI in blue shows nuclear translocation of YAP in JOSD2 over-expressed HuCCT-1 cells. The nuclear vs cytoplasm ratio was determined in 50 cells per cohort by Image J and represented as the mean ± SEM; ∗P < 0.05. (H) Down-regulation of YAP/TAZ caused by JOSD2 depletion in CCLP-1 cells can be rescued by MG132 (10 μmol/L, 6 h). (I) JOSD2 can antagonize SCFβ−TRCP E3 Ligase to stabilize YAP/TAZ protein levels in RBE cells.

The above findings encouraged us to further examine the potential role of JOSD2 in the regulation of YAP/TAZ turnover and function in CCA. Deletion of endogenous JOSD2 by two specific shRNA substantially reduced YAP/TAZ protein levels (Fig. 2C). Moreover, over-expression of JOSD2-WT, but not the catalytically inactive C24A mutant, robustly up-regulated YAP/TAZ protein levels, indicting a deubiquitinase activity-dependent manner was involved (Fig. 2D). To exclude the possibility that the effect of JOSD2 on YAP/TAZ was mediated through transcriptional regulation, we performed qRT-PCR assay to examine the mRNA levels of YAP/TAZ. As shown in Fig. S2B and S2C, in JOSD2-depleted or -overexpressed cells, the mRNA levels of YAP/TAZ remained unchanged, suggesting that the influence on YAP/TAZ by JOSD2 was not dependent on the mRNA levels. Subsequently, CCLP-1 cells infected with lentivirus encoding empty vector or JOSD shRNA were treated with protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide for the indicated times. Depletion of JOSD2 accelerated the YAP protein degradation and the half-life was significantly reduced (Fig. 2E). We then introduced two reporter systems, YAP- and TAZ-induced 8 × GTⅡC-luciferase reporter and WWTR1-luciferase fusion construct, to monitor the transcriptional activity of YAP/TAZ and the protein abundance of TAZ, respectively20. As expected, JOSD2 shRNA greatly reduced both the YAP/TAZ transcriptional activities and protein abundance (Fig. 2F), suggesting that JOSD2 was required to optimally maintain the protein stabilities and transcriptional responses of YAP/TAZ. We also utilized JOSD2 over-expressed HuCCT-1 to conduct immunofluorescence analyses using confocal microscopy. The results indicated that JOSD2 increased the protein level of YAP and significantly enhanced the nuclear/cytoplasm ratio of YAP (Fig. 2G).

In this context, we next asked whether such regulation of YAP/TAZ was implicated with previous reported ubiquitin–proteasome pathway. Upon treating JOSD2-depletion cells with proteasome inhibitor MG132, we demonstrated that the degradation of YAP/TAZ protein mediated by JOSD2 depletion was significantly attenuated (Fig. 2H). In addition, we transfected β-TRCP and cullin 1, two subunits of E3 ligase SCFβ−TRCP into RBE cells, and found that YAP/TAZ protein levels were down-regulated as expected; in the contrast, the exogenous introduction of JOSD2 abrogated SCFβ−TRCP-mediated degradation of YAP/TAZ in a deubiquitinase activity-dependent manner (Fig. 2I).

Taken together, these results validate that JOSD2 inhibition exhibited potent anti-proliferation effect in CCA cells. Meanwhile, JOSD2 regulates YAP/TAZ through the stabilization of their protein levels in a deubiquitinase activity-dependent manner.

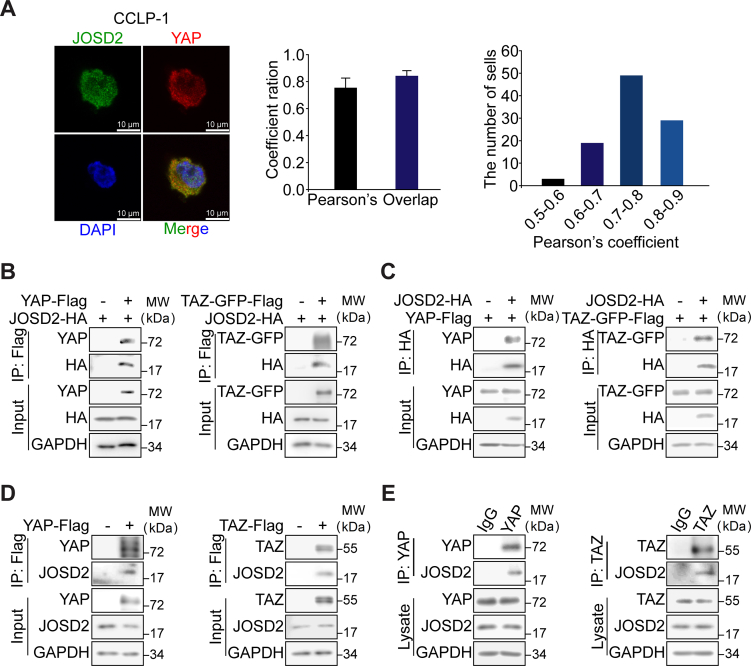

3.3. JOSD2 interacts with YAP/TAZ proteins

We then asked whether JOSD2 stabilized YAP/TAZ through the direct protein–protein interaction. Firstly, immunofluorescence assay was conducted to examine the cellular localization of JOSD2 and YAP. Fig. 3A displayed that an overlapping signal (in yellow) from JOSD2 (in green) and YAP (in red) confirming the co-localization between JOSD2 and YAP, as revealed by the high co-localization degree obtained in 100 randomly-analyzed CCLP-1 cells (Pearson's coefficient = 56.9 ± 8.5%, overlap coefficient = 72.8 ± 5.7%). The similar result was obtained in Hela cells in Supporting Information Fig. S3A. To further verify the protein–protein interaction of JOSD2 with YAP/TAZ, plasmids encoding HA-tagged JOSD2 and Flag-tagged YAP or TAZ-GFP fusion protein were co-transfected into 293T cells for co-immunoprecipitation assays. As expected, both the exogenous YAP and TAZ indeed physically interacted with JOSD2 (Fig. 3B and C). Consistently, we observed an interaction of the Flag-tagged YAP/TAZ and endogenous JOSD2 (Fig. 3D). Similar results were also obtained from endogenous co-immunoprecipitation assays which attested JOSD2–YAP/TAZ interaction at endogenous levels (Fig. 3E).

Figure 3.

JOSD2 interacts with YAP/TAZ. (A) Representative images of immunofluorescence with JOSD2 in green, YAP in red and DAPI in blue shows high co-localization of YAP and JOSD2 in CCLP-1 cells. The pearson's and overlap coefficient ratio were determined by Image J. The results represent as the mean ± SD, n = 100. (B) and (C) Interaction between exogenous JOSD2 and YAP/TAZ. HA-tagged JOSD2 and Flag-tagged YAP or TAZ plasmids were co-transfected into 293T, followed by incubation of cellular extracts and anti-HA magnetic beads or anti-DYKDDDDK (anti-Flag) IP resin. Immunoblotting was performed with indicated antibodies. (D) Interaction between endogenous JOSD2 and exogenous YAP/TAZ. Exogenous Flag-tagged YAP or TAZ was transfected into 293T, then the cell lysate was prepared for Co-IP with anti-DYKDDDDK IP resin and examined by immunoblotting. (E) Endogenous interaction of YAP/TAZ with JOSD2 was determined by Co-IP analyses using antibodies against YAP or TAZ, and followed by the immunoblotting with anti-JOSD2 antibody.

In aggregate, these data illustrate the physically interaction between JOSD2 and YAP/TAZ at exogenous and endogenous levels.

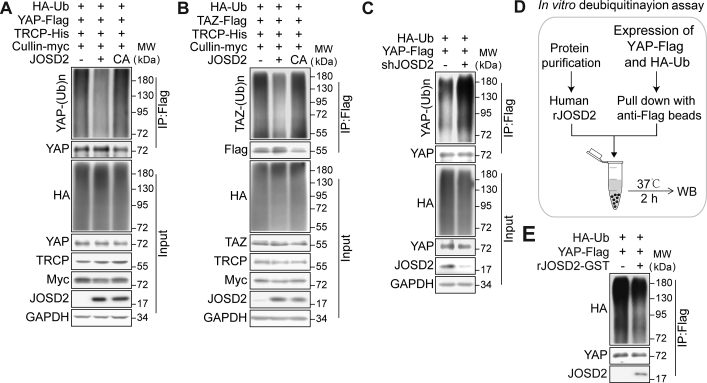

3.4. JOSD2 removes poly-ubiquitin chains on YAP/TAZ proteins

Our above-mentioned results verified the interaction between JOSD2 and YAP/TAZ, since JOSD2 has been validated as a DUB, we next asked whether JOSD2 removed the poly-ubiquitin chains on YAP/TAZ. As the ubiquitination of YAP/TAZ is largely mediated by SCFβ−TRCP E3 ligase, we firstly investigated the influence of JOSD2 on β-TRCP and cullin1 mediated ubiquitination of YAP/TAZ. As shown in Fig. 4A and B, introduction of JOSD2-WT, but not the catalytic mutant JOSD2-C24A, significantly reduced the ubiquitination levels of YAP/TAZ. Consistently, knock down of JOSD2 obviously increased YAP ubiquitination levels (Fig. 4C). In order to further confirm this effect of JOSD2, we performed an in vitro deubiquitination assay using bacterial expressed recombinant human JOSD2 (rhJOSD2, Fig. 4D). Flag-tagged YAP and HA-tagged ubiquitin were transfected into 293T cells, then ubiquitnated YAP was purified from the cell lysate using anti-Flag IP resin, and subjected to the rhJOSD2 incubation for 2 h at 37 °C in a cell-free system. As shown in Fig. 4E, the poly-ubiquitin chains on YAP were significantly reduced by rhJOSD2.

Figure 4.

JOSD2 removes the poly-ubiquitin chains on YAP/TAZ. (A, B) JOSD2 decreases ubiquitination of YAP (A) and TAZ (B) in a catalytic activity-dependent manner. JOSD2-WT or JOSD2-C24A, HA-tagged ubiquitin and flag-tagged YAP or TAZ were co-expressed into 293T cells in the presence of β-TRCP and cullin1 (known as E3 ligase of YAP/TAZ), then the cells were treated with MG132 (10 μmol/L) for 6 h before harvest. Total cell lysates were immune-precipitated with anti-DYKDDDDK IP resin to detect the poly-ubiquitin chains on YAP/TAZ. (C) Depletion of JOSD2 increases YAP ubiquitination. HA-tagged ubiquitin and flag-tagged YAP plasmids were co-transfected into 293T cells with or without JOSD2 depletion followed by MG132 (10 μmol/L, 6 h) treatment. Cell lysates were immune-precipitated with anti-DYKDDDDK IP resin and subjected to immunoblotting analysis. (D) and (E) Bacterial-expressed recombinant human JOSD2 (rhJOSD2) effectively removes the poly-ubiquitination on YAP in vitro. 293T cells transfected with HA-tagged ubiquitin and Flag-tagged YAP were lysed and the ubiquitinated YAP was pulled down by anti-DYKDDDDK IP resin to incubate with purified rhJOSD2 for 2 h at 37 °C. Subsequently, immunoblotting was performed to assess YAP ubiquitination level.

We next introduced a pan DUB inhibitor PR619 to further verify the regulation of JOSD2 toward YAP/TAZ. As shown in Supporting Information Fig. S4A, PR619 greatly abolished the deubiquitinating efficiency of JOSD2 on YAP, as indicated by the reversal of loss of poly-ubiquitin chains on YAP in PR619 treated cells.

Collectively, these results demonstrate that JOSD2 stabilizes YAP/TAZ through the cleavage of poly-ubiquitin chains from YAP/TAZ, which confirm its regulation on YAP/TAZ as a DUB.

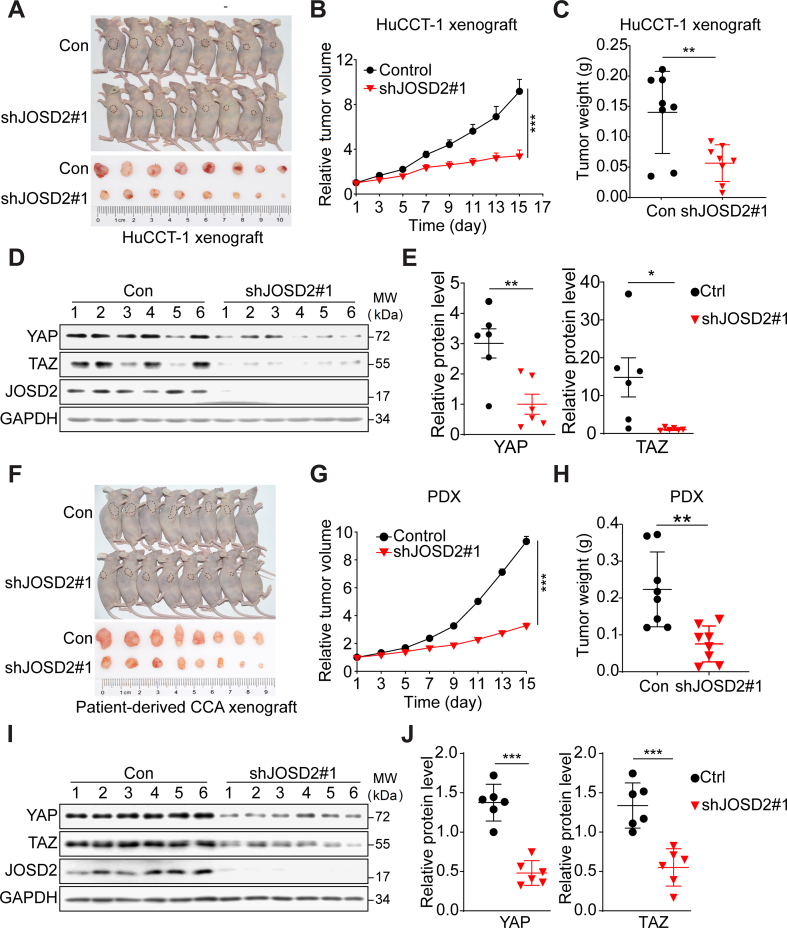

3.5. JOSD2 is essential for the growth of CCA xenograft and positively correlated with YAP in CCA patients

To further substantiate the action and mechanism of JOSD2 in CCA progress, we established an CCA xenograft model through subcutaneous inoculation of HuCCT-1 cells in BALB/c nude mice with equal volume Matrigel and engrafting the parental tumor into two groups. Intratumoral injection of JOSD2-shRNA lentivirus significantly delayed the tumor growth (>60% relative volume inhibition, P < 0.001) with no significant weight loss observed (Fig. 5A and B, Supporting Information Fig. S5A and S5B). Consistently, JOSD2 silence markedly decreased >50% tumor weight (P < 0.01, Fig. 5C). We next monitored the intratumoral protein level to verify the interference on YAP/TAZ protein level and found an evidently reduction of YAP/TAZ protein in shJOSD2-treated group (Fig. 5D and E). Moreover, patient derived cell (PDC) and patient-derived xenograft (PDX) model were further introduced to validate the YAP/TAZ regulation and tumor-promoting roles of JOSD2 in CCA patients. As shown in Fig. S5C and S5D, JOSD2 silence notably impeded PDC proliferation and colony formation. Intratumoral injection of JOSD2-shRNA lentivirus also arrested PDX tumor growth with 65% RTV inhibition and no body weight loss (Fig. 5F and G, P < 0.001; Fig. S5E and S5F). Reduced Ki67 staining indicated a slower proliferation rate in shJOSD2 group (Fig. S5G). Meanwhile, tumor weight was also decreased to 34% in JOSD2-shRNA infected group (Fig. 5H, P < 0.01). Examination of intratumoral protein level revealed that JOSD2 depletion significantly reduced YAP and TAZ abundance (Fig. 5I and J).

Figure 5.

JOSD2 regulates CCA cell proliferation in vivo. (A, B) JOSD2 depletion arrests the growth of HuCCT-1 xenograft tumors. The HuCCT-1 xenograft bearing mouse was passaged for intratumor injection of shJOSD2 virus every two days. RTV is expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 8/group; ∗∗∗P < 0.001. (C) Knockdown of JOSD2 decreases tumor weight as present. n = 8/group; ∗∗P < 0.01. (D) and (E) The knockdown efficiency was confirmed by immunoblotting and the intratumor YAP/TAZ protein levels were decreased as quantified by Image J. ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗P < 0.05. (F) and (G) JOSD2 depletion arrests the growth of PDX. RTV is expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 8/group; ∗∗∗P < 0.001. (H) Knockdown of JOSD2 decreases PDX tumor weight as present; ∗∗P < 0.01. (I) and (J) The knockdown efficiency of JOSD2 and intratumor YAP/TAZ protein levels was confirmed by immunoblotting and quantified by Image J; ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

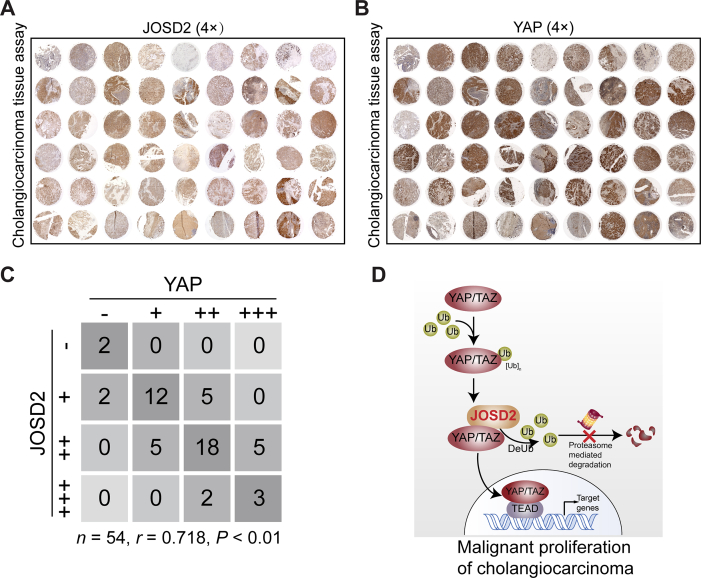

Subsequently, we performed immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining in tissue microarray from 54 CCA patients to evaluate the clinical pathological correlation between JOSD2 and YAP (Fig. 6A and B). Intensities of JOSD2 and YAP were detected in most tumor specimens and more notably, a significant correlation between JOSD2 and YAP was observed (r = 0.718, n = 54, P < 0.01; Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

JOSD2 shows high correlation with YAP in CCA patients. (A) and (B) Immunohistochemical staining of YAP and JOSD2 in CCA microarray (n = 54/group). (C) JOSD2 and YAP expression levels were positively correlated in CCA tumor samples; n = 54, r = 0.718, P < 0.01. (D) Scheme for the regulatory mechanism of JOSD2 on YAP/TAZ in CCA malignant proliferation.

Collectively, these results support our hypothesis that the high profile of JOSD2 facilitates CCA progression in correlation with YAP/TAZ, and JOSD2 could be a potential therapeutic target for CCA treatment.

4. Discussion

Emerging evidence has highlighted the essential roles of DUBs in tumorigenesis and malignant progression of various cancer types23. These aberrantly-activated DUBs in cancer therefore represent novel promising intervention targets for therapy. However, the oncogenic functions and underlying mechanisms of DUBs are not fully uncovered in CCA. Given the essential role of YAP/TAZ pathway in CCA, we globally profiled the potential contribution of DUBs to CCA and YAP signaling, and identified JOSD2 as a novel YAP/TAZ orchestrator which promoted cell proliferation in CCA (Fig. 6D).

As a member of Machado–Joseph Disease family, JOSD2 is reported to cleave poly-ubiquitin chains in vitro, while its cellular function remains elusive24. Recently, Norberg's group25,26 reported that JOSD2 deubiquitinates and stabilizes 3 important components (aldolase A, phosphofructokinase-1 and phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase) of glucose metabolic enzyme complex, leading to enhanced glycolytic rate and lung adenocarcinomas progression. While Zhou et al.27 found that JOSD2 mediates the deubiquitination of NOD-like receptor family, pyrin domain containing 3 inflammasome R779C variant, which exacerbates very-early-onset inflammatory bowel disease. Hence, these clues implicate the critical role of JOSD2 in different physiological and pathological processes. Our observation that JOSD2 strengthens the protein abundance of YAP/TAZ by decreasing their ubiquitination has opened new opportunity to target JOSD2 for CCA treatment.

Addiction to YAP/TAZ is regarded as an attribute of many solid tumors that may be exploited therapeutically5,28. Upon phosphorylation by Hippo kinases MST1/2 and LATS1/2, YAP/TAZ are retained in the cytoplasm and then subjected to ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation9. However, it is frustratingly hard to provoke kinase activity so as to suppress the YAP signaling. Therefore, the manipulation of ubiquitination by inhibiting DUBs’ catalytic activity may provide a feasible way to destabilize YAP/TAZ. In addition to JOSD2 identified in this study, a few other DUBs have been characterized as potential regulators of Hippo–YAP pathway. Ubiquitin-specific peptidase 9X (USP9X) may exert dual function in regulating Hippo–YAP signaling as it has been found to increase the protein stability of YAP and its upstream negative regulating kinase LATS29,30. Through stabilizing the E3 ligase of LATS, ubiquitin thioesterase OTU1 (YOD1) is also reported to modulate the Hippo–YAP/TAZ pathway31. However, its indirect mode of action make it not preferred as an ideal target to address the undruggablility of YAP/TAZ. Another three DUBs, ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase 10 (USP10), otubain-2 (OTUB2) and ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase 47 (USP47) deubiquitinate YAP/TAZ, playing important roles in hepatocellular carcinoma, breast cancer and colorectal cancer, respectively21,32,33. However, for CCA patients, the expression levels of USP10, OTUB2 or USP47 were not correlated with the disease free survival, indicating that these three DUBs may not be activated in CCA (Supporting Information Fig. S6A–S6C). Similar results were also obtained for USP9X or YOD1 (Fig. S6D and S6E). In the contrast, our results not only support the regulation of JOSD2 on YAP/TAZ, but also demonstrate the highly correlation of JOSD2 in CCA poor prognosis.

Admittedly, molecular profiling has identified a number of oncogenes in CCA, including fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) fusion, isocitrate dehydrogenase 1/2 (IDH1/2) mutation and Kirsten rat sarcoma 2 viral oncogene homolog (KRAS) mutation34. However, despite those FGFR- or IDH1/2-tarrgeting agents indeed exhibited anti-CCA activities on cellular and animal models, most CCA patients are still incurable and exhibit dismal prognosis, probably owing to that these targets only cover less than 50% CCA patients1. In contrast, YAP/TAZ is generally overactive in CCA tumors: Marti et al.7 have observed a YAP positive rate over than 80% in CCA specimens using IHC; while Pei et al.35 found that ∼90% patients with positive YAP expression and significant nuclear localization are correlated with worse clinical outcomes. In line with these findings, our IHC results are also highly consistent with the above findings with YAP positive rate around 90% (Fig. 6A and B). Up to now, the relation between YAP/TAZ and FGFR or IDH hasn't been well clarified yet, but our results show the silence of YAP/TAZ as well as JOSD2 in RBE, a cell line that characterized with IDH1 mutation, has notably arrested cell proliferation. Therefore, we are encouraged to speculated that YAP and its paralogous protein TAZ may be regarded as potential intervention targets for a large population of advanced CCA patients.

YAP and TAZ are two paralogs which retain remarkable similarities and have been regarded as functionally redundant36. In the past decades, some studies have supported their incompletely overlapping cell functions36. Typically, it is reported that TAZ seems to be more relevant than YAP in lung cancer37. Unfortunately, in the progression of CCA, the distinctive or divergent function of YAP and TAZ is still lack of study. Nevertheless, many literatures have emphasized on the CCA-promoting effect not only of YAP but also TAZ7,12. Our data also suggested that YAP and TAZ both play vital roles in regulating CCA proliferation (Fig. 1A and B). What's more, YAP is regarded to regulate more in cell division and cell cycle, whereas TAZ controls migration based on their non-overlapping transcriptional programs. However, they may exert complementary roles in tumor progression under complicated tumor genetic background various stimuli such as chemotherapeutic drugs36,38. Since JOSD2 regulates both YAP and TAZ abundance, targeting JOSD2 may be able to orchestrate two CCA drivers and circumvent such complementary activation to exhibit potent tumor inhibition effect.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our current study unravels the JOSD2–YAP/TAZ signaling axis in regulating CCA progress. Mechanistically, JOSD2 functions as a DUB of YAP/TAZ and stabilizes their protein levels, which may represent a promising intervention target. Consequently, further exploration of specific and potent JOSD2 inhibitors is merited to improve the clinical outcome of CCA patients.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Ms. Renhua Gai from Zhejiang University for providing technical assistance in IHC. This work was supported by the Key Program of the Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81830107), the Natural Science Foundation for Distinguished Young Scholar of China (No. 81625024), the Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81773753, No. 81973349), and the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. LR19H310002 and No. LR21H300003, China).

Author contributions

Meijia Qian, Fangjie Yan, Weihua Wang, Jiamin Du and Tao Yuan performed most of the experiments in this work and prepared the figures. Ruilin Wu, Chenxi Zhao, Jiao Wang and Xiaoyang Dai performed the in vivo experiments. Jiabin Lu performed some of the IF analyses and helped in the revision of manuscript. Bo Zhang, Nengming Lin, Xin Dong, Xiaowu Dong and Bo Yang provided some material supports. Hong Zhu and Qiaojun He conceived the conception of the study, designed the experiments and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

All the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. All institutional and national guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals were followed.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Supporting data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2021.04.003.

Contributor Information

Hong Zhu, Email: hongzhu@zju.edu.cn.

Qiaojun He, Email: qiaojunhe@zju.edu.cn.

Appendix ASupplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Banales J.M., Marin J.J.G., Lamarca A., Rodrigues P.M., Khan S.A., Roberts L.R., et al. Cholangiocarcinoma 2020: the next horizon in mechanisms and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17:557–588. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-0310-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rizvi S., Khan S.A., Hallemeier C.L., Kelley R.K., Gores G.J. Cholangiocarcinoma-evolving concepts and therapeutic strategies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15:95–111. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Razumilava N., Gores G.J. Cholangiocarcinoma. Lancet. 2014;383:2168–2179. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61903-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelley R.K., Bridgewater J., Gores G.J., Zhu A.X. Systemic therapies for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 2020;72:353–363. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zanconato F., Cordenonsi M., Piccolo S. YAP/TAZ at the roots of cancer. Cancer Cell. 2016;29:783–803. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nguyen C.D.K., Yi C. YAP/TAZ signaling and resistance to cancer therapy. Trends Cancer. 2019;5:283–296. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2019.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marti P., Stein C., Blumer T., Abraham Y., Dill M.T., Pikiolek M., et al. YAP promotes proliferation, chemoresistance, and angiogenesis in human cholangiocarcinoma through TEAD transcription factors. Hepatology. 2015;62:1497–1510. doi: 10.1002/hep.27992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao C., Zeng C., Ye S., Dai X., He Q., Yang B., et al. Yes-associated protein (YAP) and transcriptional coactivator with a PDZ-binding motif (TAZ): a nexus between hypoxia and cancer. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10:947–960. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2019.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Totaro A., Panciera T., Piccolo S. YAP/TAZ upstream signals and downstream responses. Nat Cell Biol. 2018;20:888–899. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0142-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sugihara T., Isomoto H., Gores G., Smoot R. YAP and the Hippo pathway in cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastroenterol. 2019;54:485–491. doi: 10.1007/s00535-019-01563-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu H., Liu Y., Jiang X.W., Li W.F., Guo G., Gong J.P., et al. Clinicopathological and prognostic significance of Yes-associated protein expression in hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:13499–13508. doi: 10.1007/s13277-016-5211-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiao H., Tong R., Yang B., Lv Z., Du C., Peng C., et al. TAZ regulates cell proliferation and sensitivity to vitamin D3 in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2016;381:370–379. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yan F., Qian M., He Q., Zhu H., Yang B. The posttranslational modifications of Hippo–YAP pathway in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 2020;1864:129397. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2019.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qian M., Yan F., Yuan T., Yang B., He Q., Zhu H. Targeting post-translational modification of transcription factors as cancer therapy. Drug Discov Today. 2020;25:1502–1512. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2020.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deng L., Meng T., Chen L., Wei W., Wang P. The role of ubiquitination in tumorigenesis and targeted drug discovery. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5:11. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-0107-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schauer N.J., Magin R.S., Liu X., Doherty L.M., Buhrlage S.J. Advances in discovering deubiquitinating enzyme (DUB) inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2020;63:2731–2750. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bushweller J.H. Targeting transcription factors in cancer—from undruggable to reality. Nat Rev Cancer. 2019;19:611–624. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0196-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen X.X., Yin Y., Cheng J.W., Huang A., Hu B., Zhang X., et al. BAP1 acts as a tumor suppressor in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma by modulating the ERK1/2 and JNK/c-Jun pathways. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:1036. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-1087-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Artegiani B., van Voorthuijsen L., Lindeboom R.G.H., Seinstra D., Heo I., Tapia P., et al. Probing the tumor suppressor function of BAP1 in CRISPR-engineered human liver organoids. Cell Stem Cell. 2019;24:927–943. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2019.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yuan M., Chen X., Sun Y., Jiang L., Xia Z., Ye K., et al. ZDHHC12-mediated claudin-3 S-palmitoylation determines ovarian cancer progression. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10:1426–1439. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu H., Yan F., Yuan T., Qian M., Zhou T., Dai X., et al. USP10 promotes proliferation of hepatocellular carcinoma by deubiquitinating and stabilizing YAP/TAZ. Cancer Res. 2020;80:2204–2216. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sugihara T., Werneburg N.W., Hernandez M.C., Yang L., Kabashima A., Hirsova P., et al. YAP tyrosine phosphorylation and nuclear localization in cholangiocarcinoma cells are regulated by LCK and independent of LATS Activity. Mol Cancer Res. 2018;16:1556–1567. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-18-0158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.D'Arcy P., Wang X., Linder S. Deubiquitinase inhibition as a cancer therapeutic strategy. Pharmacol Ther. 2015;147:32–54. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seki T., Gong L., Williams A.J., Sakai N., Todi S.V., Paulson H.L. JosD1, a membrane-targeted deubiquitinating enzyme, is activated by ubiquitination and regulates membrane dynamics, cell motility, and endocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:17145–17155. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.463406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang B., Zheng A., Hydbring P., Ambroise G., Ouchida A.T., Goiny M., et al. PHGDH defines a metabolic subtype in lung adenocarcinomas with poor prognosis. Cell Rep. 2017;19:2289–2303. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.05.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krassikova L., Zhang B., Nagarajan D., Queiroz A.L., Kacal M., Samakidis E., et al. The deubiquitinase JOSD2 is a positive regulator of glucose metabolism. Cell Death Differ. 2020;28:1091–1109. doi: 10.1038/s41418-020-00639-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou L., Liu T., Huang B., Luo M., Chen Z., Zhao Z., et al. Excessive deubiquitination of NLRP3-R779C variant contributes to very-early-onset inflammatory bowel disease development. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;147:267–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moroishi T., Hansen C.G., Guan K.L. The emerging roles of YAP and TAZ in cancer. Nat Rev Canc. 2015;15:73–79. doi: 10.1038/nrc3876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu C., Ji X., Zhang H., Zhou Q., Cao X., Tang M., et al. Deubiquitylase USP9X suppresses tumorigenesis by stabilizing large tumor suppressor kinase 2 (LATS2) in the Hippo pathway. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:1178–1191. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA117.000392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Toloczko A., Guo F., Yuen H.-F., Wen Q., Wood S.A., Ong Y.S., et al. Deubiquitinating enzyme USP9X suppresses tumor growth via LATS kinase and core components of the Hippo pathway. Cancer Res. 2017;77:4921–4933. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-3413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim Y., Kim W., Song Y., Kim J.R., Cho K., Moon H., et al. Deubiquitinase YOD1 potentiates YAP/TAZ activities through enhancing ITCH stability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:4691–4696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1620306114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Z., Du J., Wang S., Shao L., Jin K., Li F., et al. OTUB2 promotes cancer metastasis via Hippo-independent activation of YAP and TAZ. Mol Cell. 2019;73:7–21. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pan B., Yang Y., Li J., Wang Y., Fang C., Yu F.X., et al. USP47-mediated deubiquitination and stabilization of YAP contributes to the progression of colorectal cancer. Protein Cell. 2020;11:138–143. doi: 10.1007/s13238-019-00674-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Rourke C.J., Munoz-Garrido P., Andersen J.B. Molecular targets in cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology. 2020;73:62–74. doi: 10.1002/hep.31278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pei T., Li Y., Wang J., Wang H., Liang Y., Shi H., et al. YAP is a critical oncogene in human cholangiocarcinoma. Oncotarget. 2015;6:17206–17220. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reggiani F., Gobbi G., Ciarrocchi A., Sancisi V. YAP and TAZ are not identical twins. Trends Biochem Sci. 2021;46:154–168. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2020.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Noguchi S., Saito A., Horie M., Mikami Y., Suzuki H.I., Morishita Y., et al. An integrative analysis of the tumorigenic role of TAZ in human non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:4660–4672. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hayashi H., Higashi T., Yokoyama N., Kaida T., Sakamoto K., Fukushima Y., et al. An imbalance in TAZ and YAP expression in hepatocellular carcinoma confers cancer stem cell-like behaviors contributing to disease progression. Cancer Res. 2015;75:4985–4997. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.