Abstract

Transcriptomic, proteomic, and methylation aging clocks demonstrate that aging has a predictable preset program, while transcriptome trajectory turning points indicate that the 20–40 age range in humans is the likely stage at which the progressive loss of homeostatic control, and in turn aging, begins to have detrimental effects. Turning points in this age range overlapping with human aging clock genes revealed five candidates that we hypothesized could play a role in aging or age-related physiological decline. To examine these gene’s effects on lifespan and health-span, we utilized whole body and heart-specific gene knockdown of human orthologs in Drosophila melanogaster. Whole body lysyl oxidase like 2 (Loxl2), fz3, and Glo1 RNAi positively affected lifespan as did heart-specific Loxl2 knockdown. Loxl2 inhibition concurrently reduced age-related cardiac arrythmia and collagen (Pericardin) fiber width. Loxl2 binds several transcription factors in humans and RT-qPCR confirmed that a conserved transcriptional target CDH1 (Drosophila CadN2) has expression levels which correlate with Loxl2 reduction in Drosophila. These results point to conserved pathways and multiple mechanisms by which inhibition of Loxl2 can be beneficial to heart health and organismal aging.

Keywords: Drosophila, Loxl2, aging clocks, arrhythmia, lifespan, Cadherin, Pericardin

Introduction

Molecular aging clocks use transcriptomics (Mamoshina et al. 2018; González-Velasco et al. 2020), proteomics (Lehallier et al. 2019; Johnson et al. 2020), and epigenetic markers (Horvath 2013; Bergsma and Rogaeva 2020; Galkin et al. 2021) to predict a subject’s age with high accuracy. In addition, studies examining the transcriptomes and proteomes during aging have shown that the majority of genes change their expression trends (transcriptome trajectory turning points) between ages 20 and 40 in multiple tissues (Somel et al. 2010; Skene et al. 2017; Lehallier et al. 2019). The age range of these expression turning points corresponds to the time at which most adults will begin to visibly detect aging phenotypes ranging from skin wrinkles to graying hair (Albert et al. 2007; Panhard et al. 2012). We, therefore, hypothesized that a number of the molecules having turning points in this age range should present in aging clock data, and play a role in aging or age-related phenotypes.

Through the examination of aging clocks (Horvath 2013; Lehallier et al. 2019) and transcriptome trajectory turning points (Skene et al. 2017), we identified Lysyl oxidase like 2 (Loxl2). Lysyl oxidases oxidatively deaminate lysine and hydroxylysine residues forming aldehydes on collagens which can then covalently bond, cross-linking the collagens and forming fibers (de Jong et al. 2011; Erasmus et al. 2020). Collagen is not only the most abundant protein in the extracellular matrix (Frantz et al. 2010), but when excessive fibrillar collagen accumulates in the heart it is recognized as cardiac fibrosis (Manabe et al. 2002) and the incidence of cardiac arrhythmia is frequently dependent on collagen texture (de Jong et al. 2011).

Loxl2 also binds transcription factors in the nucleus to inhibit and promote the transcription of genes that play a role in age-related diseases ranging from cancers to cardiovascular diseases (Wen et al. 2020). In human cells, Loxl2 binds the snail transcription factor to regulate E-Cadherin 1 (CDH1) expression (Peinado et al. 2005), and it has been demonstrated in flies that E-cadherin is dependent on the snail1 homolog escargot (esg; Tanaka-Matakatsu et al. 1996). Cadherins, Snail1, and LOXL2 are major components in the endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT; Cuevas et al. 2014) and EMT is a key modulator of age-related diseases including cancer and cardiovascular disease (Brabletz et al. 2018; Santos et al. 2019; Chen et al. 2020). Further linking Loxl2, cadherins, and collagen is the observation that the EMT program is highly correlated with epigenetic regulation that remodels the ECM. (Peixoto 2019). We therefore aimed to examine the multifaceted role of Loxl2 in aging and aging phenotypes using Drosophila melanogaster.

Materials and methods

Lifespan assay

All assays were performed in females unless noted. Fly lines are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Flies were maintained at 25°, 60% relative humidity, and 12-h light/dark cycle in vials containing 25 adults. Larvae were reared on a standard cornmeal and yeast-based diet. The standard cornmeal diet consists of the following master mix of materials pumped into vials: water (1700 ml), agar (15.8 g), yeast (50 g), Cornmeal (104 g), sugar (220 g), TEGOSEPT (4.76 g), and 95% EtOH (18.4 ml). Five-day old adults received standard food with either RU486 mifepristone in 95% ethanol to induce RNAi (200 µM) or 95% ethanol in control food. Food vials were exchanged every 2–3 days. Calculations and chart were generated using Log Rank Mantel Cox test and JMP statistical discovery software. Graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism version 7.03.

Heartbeat analysis

Semi-intact Drosophila adult fly hearts were dissected and imaged in oxygenated artificial hemolymph according to previously described protocols (Fink et al. 2009). Briefly, artificial hemolymph was prepared using NaCl (108 mM), KCl (5 mM), CaCl2·2H2O (2 mM), MgCl2·6H2O (8 mM), NaH2PO4 (1 mM), NaHCO3 (4 mM), Hepes pH 7.1 (15 mM), sucrose (10 mM), and Trehalose (5 mM). Heart recordings were performed at 100 frames per second for 30 s on each fly using HCImage software (Hamamatsu Corporation), Hamamatsu digital camera C11440, Olympus BX51WI microscope, at 10× magnification. Arrhythmia index was calculated using the standard deviation of heart periods (time between diastoles)/median period using Semi-automated Optical Heartbeat Analysis (SOHA) software (Fink et al. 2009).

Fluorescent immunohistochemistry

Fly abdomens were dissected in 1× PBS, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde diluted in 0.3% 1× Phosphate-buffered saline plus Triton X-100 (PBST) for 20–30 min. Samples were washed in PBST, blocked with PBST plus Donkey or Goat Serum Albumin for 1 h, and then washed in PBST three times for 10 min each. The samples were incubated with anti-Pericardin (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank # EC11) at 2 μg/ml overnight at 4°C, washed in PBST three times for 10 min each, then incubated with Alexa Fluor 594 anti-mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch # 115-585-166) for 2 h at room temperature. Samples were washed in PBST three times for 10 min each. Hoechst (Immunochemistry Technologies # 639) and Alexa Fluor 488 Phalloidin (Thermo Fisher scientific # 12379) were applied for 30 min followed by washing in 1× PBS and mounted in ProLong Diamond Antifade Mountant (Invitrogen # P36961) according to manufacturer’s protocols.

Confocal microscopy and image analysis

Images were taken on an Olympus FV3000 confocal microscope. Filament widths were quantified with CellSens Software version 2.2. Images finalized using ImageJ Fiji v1.53c.

Western blotting

Protein from 10 flies per replicate was extracted using TissueLyser II (Qiagen), Pierce IP lysis buffer, Protease Inhibitor Cocktail, and Phenylmethanesulfonyl Fluoride. Protein was quantified using Bicinchoninic acid assay (Thermo Fisher # 23225) on a Biotek Epoch 2 microplate spectrophotometer. Protein was denatured in 2-Mercaptoethanol and 2× Laemmli sample buffer at 95° for 5 min and loaded onto 4–20% Mini-PROTEAN TGX Precast Protein Gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories # 4561093) then rapid transfer to Polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio Rad # 1620177). Membranes were blocked in 5% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) and 1× Tris-Buffered Saline plus Tween (TBST) for 1 h. Pericardin antibody at 0.2 μg/ml (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank# EC11) or B-tubulin at 0.2 μg/ml (DSBH # E7) were applied in 5% BSA at 4° overnight then washed in TBST four times for 5 min. Secondary anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase (HRP; Jackson ImmunoResearch # 115-035-174) or anti-rabbit HRP (Jackson ImmunoResearch # 711-035-152) were applied at 1:5000 in 1% BSA for 1 h at room temperature then washed in TBST four times for 5 min. Super Signal West Pico Plus Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Scientific # 34577) was applied and then imaged with Bio-Rad Chemidoc. Stripping of the blot was performed using Restore Western Blot Stripping Buffer (Thermo Scientific # 21059). Band intensity ratios were calculated using BioRad Image Lab 6.1.

RT-qPCR

RNA from 10 flies per replicate was extracted using TissueLyser II (Qiagen), Trizol, chloroform, and isopropanol, then washed in RNAse free ethanol. DNase treatment (Turbo DNA-free, Ambion # AM1907) was performed following manufacturer’s protocol. RNA was quantified using Thermo Scientific Nanodrop Lite Spectrophotometer. cDNA was synthesized using qScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Quanta Bio # 95047-100) on the Applied Biosystems ProFlex PCR System. qPCR was performed using primers found in Supplementary Table S2 and PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher # A25742) on Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 3. Expression was calculated relative to Ribosomal protein L32 (RpL32).

Results

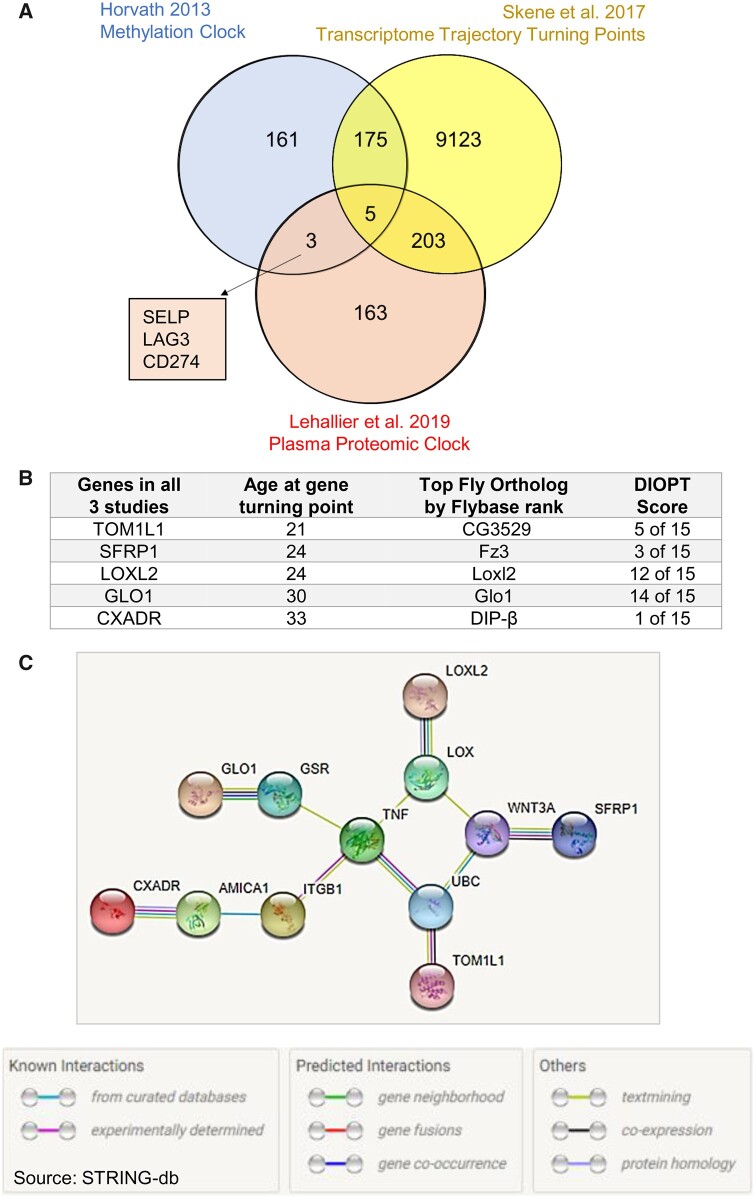

Overlapping genes in aging clocks

We first compared the list of genes that make up the Horvath methylation epigenetic aging clock (Horvath 2013) with a blood plasma proteomic clock (Lehallier et al. 2019). We next selected genes that have transcriptome trajectory turning points occurring between ages 19 and 41 in the brain (Skene et al. 2017; Figure 1A). These ages were selected because the majority of transcriptome trajectory turning points, and an end of key developmental timepoints, occur within this window (Somel et al. 2010; Skene et al. 2017). Only five genes were found to overlap between the brain turning points, plasma proteomic clock, and the methylation clock; Target Of Myb1 Like 1 Membrane Trafficking Protein (TOM1L1), Secreted Frizzled Related Protein 1 (SFRP1), Loxl2, Glyoxalase I (GLO1), and CXADR Ig-Like Cell Adhesion Molecule (CXADR; Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Overlapping genes in aging clocks. (A) Numbers of genes represented in the Horvath methylation epigenetic aging clock (Horvath 2013), Lehallier blood plasma proteomic clock (Lehallier et al. 2019), and genes that have transcriptome trajectory turning points occurring between ages 19 and 41 in the brain (Skene et al. 2017) including the amount of gene overlap between these studies. The identity of three genes not investigated in this study, but are found in the Horvath methylation epigenetic aging clock and Lehallier blood plasma proteomic clock, are found in the square inset. (B) The identity of the five human genes found in all three studies from 1A, the age at which they have human transcriptome trajectory turning points, their top ranking Drosophila ortholog, and their DRSC Integrative Ortholog Prediction Tool score (DIOPT version 9; Hu et al. 2011). (C) STRING-db analysis for how the five genes are connected in literature. The five genes are the outermost nodes.

Although at first glance these seem relatively unrelated, however, a gene network of the five genes in a STRING-db analysis suggests that the five genes may function around a TNF/WNT3A axis (Figure 1C). The genes are also target genes of the CAMP Responsive Element Binding Protein 1 transcription factor (Rouillard et al. 2016), possibly indicating a common regulatory axis.

We employed the model organism D. melanogaster due to its short lifespan and extensively available genetic toolkits to examine the age-related effects of these genes. We used Flybase (Larkin et al. 2021) to identify Drosophila genes with the highest ortholog scores for these five human genes (Figure 1B). Human CXADR had low homology with Drosophila proteins and was excluded from further study.

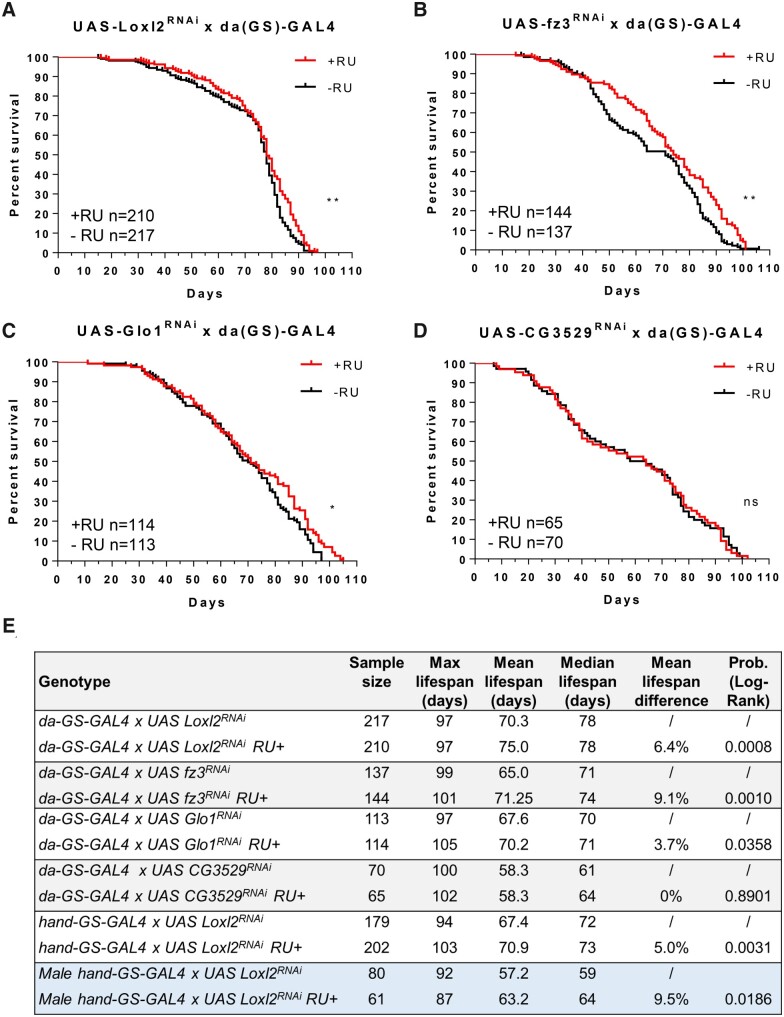

Loxl2, fz3, and Glo1 reduction affects lifespan

To determine if the four genes may be relevant to Drosophila aging, UAS RNAi fly lines for the candidate genes were crossed with whole body daughterless-GeneSwitch GAL4 (da(GS)-GAL4) lines. RNAi was initiated by RU486 (mifepristone) chemical feeding in food starting on day five post-eclosion (to avoid impacting development) and continued until death. RNAi of Loxl2, fz3, and Glo1 significantly affected lifespan of female flies while CG3529 (TOM1L1 homolog) did not (Figure 2, A–D). Mean lifespan increased in the three fly lines by 3.7%, 6.4%, and 9.1%, respectively (Figure 2E).

Figure 2.

Loxl2, fz3, and Glo1 reduction affects lifespan. (A–D) Lifespan assays for UAS RNAi of Glo1, Loxl2, fz3, and CG3529 fly lines crossed with whole body da(GS)-GAL4 lines. RNAi was initiated (+RU vs control −RU) in day five adults and continued until death. (E) Summary of lifespan assays performed in this study using JMP statistical discovery software. Log Rank Mantel Cox test *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, ****P ≤ 0.0001, ns, not significant.

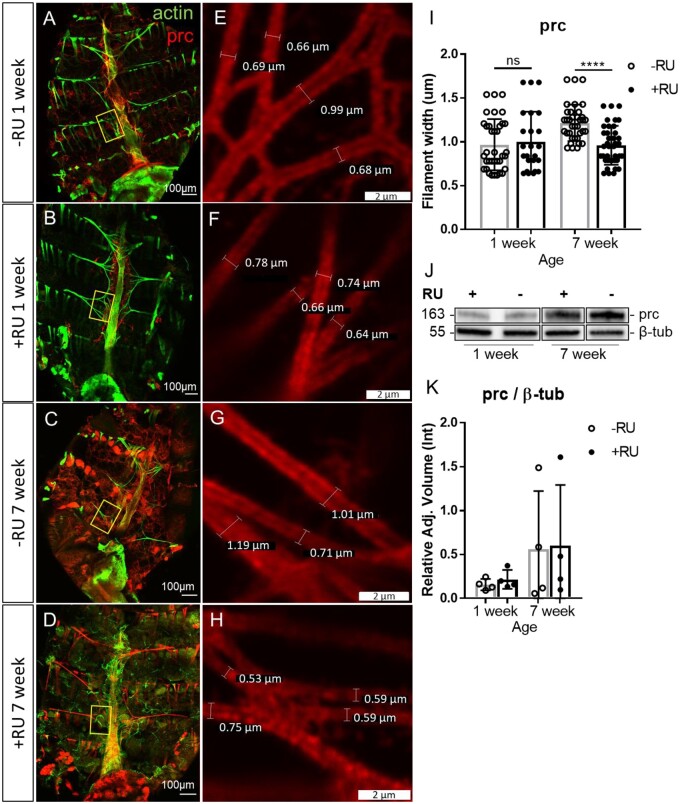

Loxl2 RNAi reduces Pericardin filament width with age

Lysl oxidases function to deaminate collagen fibers, allowing their crosslinking (Erasmus et al. 2020). We, therefore, examined the effect of Loxl2 on Drosophila collagen IV; Pericardin. Pericardin (prc) levels and filament width have been shown to increase with age, and reducing collagen-interacting protein SPARC increases lifespan while its overexpression increases arrhythmicity (Vaughan et al. 2018). We immuno-stained for Pericardin (Figure 3, A–D) and measured Pericardin filament width in alary muscles near the heart tube (Figure 3, E–H). Quantification revealed that filament widths increased with age and RNAi for Loxl2 significantly reduced this effect (Figure 3I). Western blots against Pericardin were then performed to determine if the filament width may be a result of changing Pericardin levels (Figure 3J, Supplementary Figure S1), but no significant difference of Pericardin levels between age matched +/−RU fed lines was seen (Figure 3K).

Figure 3.

Loxl2 RNAi reduces Pericardin filament width with age. (A–D) Dissected Drosophila abdomen immuno-stained for Pericardin and stained with phalloidin to indicate actin filaments in alary and cardiac muscles of da(GS)-GAL4 × UAS-Loxl2 RNAi flies +/−RU induction. Yellow boxes indicate the same region in which measurements were performed for all flies. (E–H) Magnification of representative Pericardin filament measurements. (I) Quantification of 4–5 filament widths for 5–7 flies from 1 to 7 weeks of age. Unpaired t-test *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, ****P ≤ 0.0001, ns, not significant. (J) Representative Pericardin Western blots from 1 to 7 week flies. (K) Quantification of Pericardin Western blots from Figure 3J relative to β-tub; n = 4. Unpaired t-test *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, ****P ≤ 0.0001, ns, not significant.

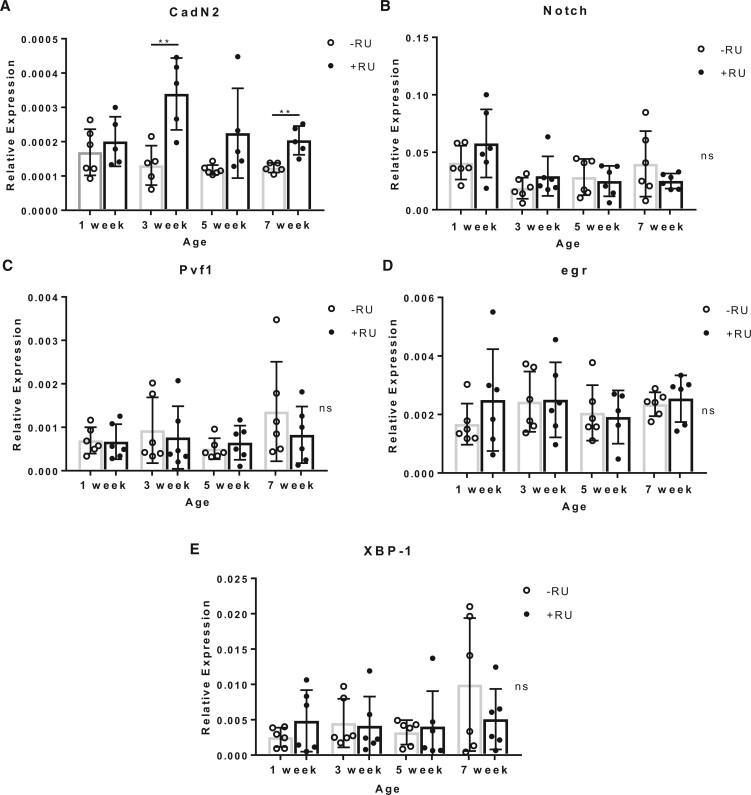

Expression of Loxl2 regulated genes from human age-related disorders

Loxl2 has also been shown to have numerous noncollagen-related functions. Critically, Loxl2 maintains transcriptional regulation of genes that play a role in age-related diseases including cancers and cardiovascular disease genes (Wen et al. 2020). These genes include Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha (TNFα) [eiger; egr] (Schumacher and Prasad 2018; Rolski and Błyszczuk 2020), X-box binding protein 1 (XBP-1; Duan et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2019), Vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) [PDGF- and VEGF-related factor 1; Pvf-1] (Taimeh et al. 2013; Braile et al. 2020), NOTCH1 (Garg et al. 2005), and Cadherin 1; CDH1 [Cadherin-N2; CadN2] (Vite and Radice 2014; Mayosi et al. 2017; Turkowski et al. 2017); Drosophila homologs in square brackets (Larkin et al. 2021). We therefore asked if these genes have differential expression under Loxl2 RNAi with age (Figure 4, A–E). We found that CadN2 expression significantly increased at three and seven weeks under Loxl2 RNAi (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Expression of Loxl2 regulated genes from human age-related disorders. (A–E) RT-qPCR for 5–6 replicates of 10 whole da(GS)-GAL4 × UAS-Loxl2 RNAi flies +/−RU induction (starting on day 5) from four time points in the Drosophila lifespan. CadN2 was significantly upregulated when Loxl2 is repressed at week three and seven; one outlier was removed from each sample before analysis. Unpaired t-test *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, *** P ≤ 0.001, **** P ≤ 0.0001, ns, not significant.

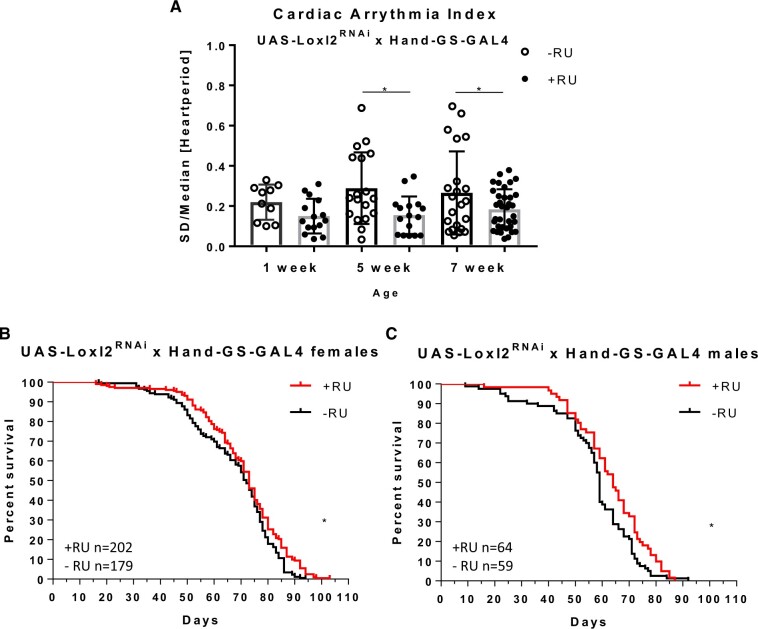

Loxl2 RNAi improves cardiac arrhythmia

Cadherins play a key role in cell matching during Drosophila heart development (Zhang et al. 2018). CadN2 is an underexplored protein in Drosophila and is the best matched ortholog to 17 Cadherins in humans (Larkin et al. 2021), of which three—CDH2 (Vite and Radice 2014; Mayosi et al. 2017; Turkowski et al. 2017), CDH5 (Bouwens et al. 2020), and CDH13 (Teng et al. 2015; Verweij et al. 2017)—play a role in, or correlate with, cardiovascular disease. Furthermore, Loxl2 has been implicated in collagen-related cardiovascular fibrosis, in particular, its reduction can reduce not only cardiac fibrosis (Yang et al. 2016) but also vascular stiffening (Steppan et al. 2019) with age in mammals.

To test if Loxl2 reduction could affect the Drosophila heart we made use of the SOHA software (Ocorr et al. 2009), to measure cardiac arrhythmia indices; which can be used as measures of heart health and cardiac aging (Ocorr et al. 2007). SOHA on crosses of UAS-Loxl2 RNAi flies with whole body daughterless-GeneSwitch GAL4 (da(GS)-GAL4) and RU486 feeding starting on day five revealed that the arrythmia indices of knockdown flies significantly improved vs. controls at aged timepoints (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Loxl2 RNAi positively affects the heart with age. (A) Whole body knockdown using da(GS)-GAL4 crossed with UAS-Loxl2 RNAi reduces cardiac arrythmia indices in Drosophila. Unpaired t-test *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, ****P ≤ 0.0001. (B, C) Heart-specific knockdown using Hand(GS)-GAL4 crossed with UAS-Loxl2 RNAi positively affects lifespan. Log Rank Mantel Cox test *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, ****P ≤ 0.0001, ns, not significant.

Due of the benefit of Loxl2 RNAi on the heart, we employed a Hand-GeneSwitch GAL4 (Hand(GS)-GAL4) heart-specific driver cross with UAS-Loxl2 RNAi to test if the lifespan benefits may be partially derived from heart Loxl2. We saw a significant mean lifespan benefit in both male and female flies (Figure 5, B and C).

Discussion

This work is the first to demonstrate that the reduction of Loxl2 has a protective mechanism in the Drosophila heart and extends mean lifespan, consistent with Loxl2’s role in mammalian cardiovascular disease (Yang et al. 2016; Steppan et al. 2019). We also show inhibiting Loxl2 can reduce Pericardin filament width and increase CadN2 expression. Our future work aims to decouple their respective contribution to the protective effects of Loxl2 reduction during aging.

Our data suggest that Loxl’s action as a transcriptional regulator may be conserved, which we can now explore in more detail utilizing the advantages of the Drosophila genetic system (McGuire et al. 2004; Allocca et al. 2018; Heigwer et al. 2018). Loxl2’s known interactions indicate that its role in aging could be through EMT which involves a transitional state that may be partially activated during aging (Brabletz et al. 2018) and interestingly EMT is even being pursued in age-related telomere shortening (Imran et al. 2021). Further investigation into the extent Loxl2 regulation in the ECM and EMT pathways in Drosophila plays with age, particularly the molecular partners and signaling of Loxl2 in the ECM and nucleus, can now be genetically explored in Drosophila. It is tempting to speculate that aging clocks and transcriptomic trajectory turning points may be picking up signals of the EMT process at a critical timepoint (20–40 years), the time at which aging phenotypes begin to be seen in humans.

The arrhythmia indices in aging Loxl2 RNAi flies without RU revealed roughly 1/3 of flies had increased arrythmia at aged timepoints revealing a biphasic distribution of arrhythmicity in the population. This is consistent with the variation that generally occurs with age, although it is not fully understood what causes this increase in variation between individuals with age (even when the population starts from the same or similar genotypes). It may be that the effects of epigenetic changes during development generate phenotypic and molecular variations that are exaggerated with age (Zhang et al. 2020). The reduction of Loxl2 may help delay certain transcriptional aspects of aging and in turn delay the effects of those variations.

Although we cannot totally rule out off target effects of the RNAi, according to the Harvard Transgenic RNAi Project led by Norbert Perrimon group, there were no off targets predicted for the RNAi line used (Perkins et al. 2015). We confirmed Loxl2 knockdown with RT-qPCR (Supplementary Figure S2), and the Drosophila RNAi phenotypes are consistent with the known crosslinking functions and cardiac effects in mouse Loxl2 knockdown models (Yang et al. 2016; Martínez Rodríguez and González 2019). It is also true that some drivers do have an effect on lifespan when combined with RU feeding in mated female flies (Landis et al. 2015), the GAL4 drivers utilized within this manuscript have been previously tested for cardiac arrythmia, lifespan, and stress impacts under RU feeding (Shaposhnikov et al. 2015; Cannon et al. 2017). Several lines of evidence including reduced lifespan or increased arrythmia under RU for several crosses from the aforementioned studies, as well as our male Loxl2 and female CG3529 lifespan data, provide support that these drivers are less likely to be affected by a positive sexually dimorphic effect of RU feeding on lifespan.

Because we saw cardiac aging related phenotypes in our Loxl2 data, but no turning point studies have been done on the heart, we wanted to see if Loxl2 had turning points in the human heart. We utilized the GTEx Portal [from The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) Project] to determine if Loxl2 had a transcriptome trajectory turning point in the human atria or ventricles within the timeframe that was seen in the brain or blood transcriptome trajectory turning point studies (Skene et al. 2017; Lehallier et al. 2019). Importantly, Loxl2 changes its average expression trajectory in the heart chambers in the 30–39 age decile consistent with the majority of transcriptome trajectory turning points seen in the blood study (Lehallier et al. 2019). Further turning point studies using human heart data would reveal other molecules important in cardiovascular aging.

Data availability

Fly lines are available upon request. The authors affirm that all data necessary for confirming the conclusions of this article are represented fully within the article, its tables, and figures.

Supplementary material is available at G3 online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The prc monoclonal antibody developed by Zaffran et al. (1995) was obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, created by the NICHD of the NIH and maintained at The University of Iowa, Department of Biology, Iowa City, IA. Stocks obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (NIH P40OD018537) were used in this study. The GTEx Project was supported by the Common Fund of the Office of the Director of the National Institutes of Health and by NCI, NHGRI, NHLBI, NIDA, NIMH, and NINDS. The data used for the analyses described in this manuscript were obtained from the GTEx Portal on December 31, 2020. Special thanks to the designers and supporters of STRING-db.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health (R01 AG058741 to H.B.).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Literature cited

- Albert AM, Ricanek K Jr, Patterson E.. 2007. A review of the literature on the aging adult skull and face: implications for forensic science research and applications. Forensic Sci Int. 172:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allocca M, Zola S, Bellosta P.. 2018. The Fruit Fly, Drosophila melanogaster: modeling of human diseases (Part II). In: Perveen F, editor. Drosophila melanogaster – Model for Recent Advances in Genetics and Therapeutics. Rijeka, Croatia: Intec. pp. 131–156. [Google Scholar]

- Bergsma T, Rogaeva E.. 2020. DNA methylation clocks and their predictive capacity for aging phenotypes and healthspan. Neurosci Insights. 15:2633105520942221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouwens E, van den Berg VJ, Akkerhuis KM, Baart SJ, Caliskan K, et al. 2020. Circulating biomarkers of cell adhesion predict clinical outcome in patients with chronic heart failure. JCM. 9:195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brabletz T, Kalluri R, Nieto MA, Weinberg RA.. 2018. EMT in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 18:128–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braile M, Marcella S, Cristinziano L, Galdiero MR, Modestino L, et al. 2020. VEGF-A in cardiomyocytes and heart diseases. IJMS. 21:5294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon L, Zambon AC, Cammarato A, Zhang Z, Vogler G, et al. 2017. Expression patterns of cardiac aging in Drosophila. Aging Cell. 16:82–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen PY, Schwartz MA, Simons M.. 2020. Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition, vascular inflammation, and atherosclerosis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 7:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas EP, Moreno-Bueno G, Canesin G, Santos V, Portillo F, et al. 2014. LOXL2 catalytically inactive mutants mediate epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Biol Open. 3:129–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong S, van Veen TA, van Rijen HV, de Bakker JM.. 2011. Fibrosis and cardiac arrhythmias. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 57:630–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Q, Chen C, Yang L, Li N, Gong W, et al. 2015. MicroRNA regulation of unfolded protein response transcription factor XBP1 in the progression of cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure in vivo. J Transl Med. 13:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erasmus M, Samodien E, Lecour S, Cour M, Lorenzo O, et al. 2020. Linking LOXL2 to cardiac interstitial fibrosis. IJMS. 21:5913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink M, Callol-Massot C, Chu A, Ruiz-Lozano P, Belmonte JCI, et al. 2009. A new method for detection and quantification of heartbeat parameters in Drosophila, zebrafish, and embryonic mouse hearts. Biotechniques. 46:101–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frantz C, Stewart KM, Weaver VM.. 2010. The extracellular matrix at a glance. J Cell Sci. 123:4195–4200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galkin F, Mamoshina P, Kochetov K, Sidorenko D, Zhavoronkov A.. 2021. DeepMAge: a methylation aging clock developed with deep learning. Aging Dis. 12:1252–1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg V, Muth AN, Ransom JF, Schluterman MK, Barnes R, et al. 2005. Mutations in NOTCH1 cause aortic valve disease. Nature. 437:270–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Velasco O, Papy-García D, Le Douaron G, Sánchez-Santos JM, De Las Rivas J.. 2020. Transcriptomic landscape, gene signatures and regulatory profile of aging in the human brain. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech. 1863:194491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heigwer F, Port F, Boutros M.. 2018. RNA interference (RNAi) screening in Drosophila. Genetics. 208:853–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath S. 2013. DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biol. 14: r 115– 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Flockhart I, Vinayagam A, Bergwitz C, Berger B, et al. 2011. An integrative approach to ortholog prediction for disease-focused and other functional studies. BMC Bioinform. 12:357– 316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imran SA, Yazid MD, Idrus RBH, Maarof M, Nordin A, et al. 2021. Is there an interconnection between epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) and telomere shortening in aging? IJMS. 22:3888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AA, Shokhirev MN, Wyss-Coray T, Lehallier B.. 2020. Systematic review and analysis of human proteomics aging studies unveils a novel proteomic aging clock and identifies key processes that change with age. Ageing Res Rev. 60:101070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis GN, Salomon MP, Keroles D, Brookes N, Sekimura T, et al. 2015. The progesterone antagonist mifepristone/RU486 blocks the negative effect on life span caused by mating in female Drosophila. Aging (Albany, NY), 7:53–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin A, Marygold SJ, Antonazzo G, Attrill H, Dos Santos G, et al. ; FlyBase Consortium. 2021. FlyBase: updates to the Drosophila melanogaster knowledge base. Nucleic Acids Res. 49:D899–D907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehallier B, Gate D, Schaum N, Nanasi T, Lee SE, et al. 2019. Undulating changes in human plasma proteome profiles across the lifespan. Nat Med. 25:1843–1850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamoshina P, Volosnikova M, Ozerov IV, Putin E, Skibina E, et al. 2018. Machine learning on human muscle transcriptomic data for biomarker discovery and tissue-specific drug target identification. Front Genet. 9:242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manabe I, Shindo T, Nagai R.. 2002. Gene expression in fibroblasts and fibrosis: involvement in cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res. 91:1103–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayosi BM, Fish M, Shaboodien G, Mastantuono E, Kraus S, et al. 2017. Identification of cadherin 2 (CDH2) mutations in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 10:p.e001605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire SE, Roman G, Davis RL.. 2004. Gene expression systems in Drosophila: a synthesis of time and space. Trends Genet. 20:384–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panhard S, Lozano I, Loussouarn G.. 2012. Greying of the human hair: a worldwide survey, revisiting the ‘50’rule of thumb. Br J Dermatol. 167:865–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peinado H, del Carmen Iglesias‐de la Cruz M, Olmeda D, Csiszar K, Fong KS, et al. 2005. A molecular role for lysyl oxidase‐like 2 enzyme in snail regulation and tumor progression. Embo J. 24:3446–3458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peixoto P, Etcheverry A, Aubry M, Missey A, Lachat C, et al. 2019. EMT is associated with an epigenetic signature of ECM remodeling genes. Cell Death Dis. 10:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins LA, Holderbaum L, Tao R, Hu Y, Sopko R, et al. 2015. The transgenic RNAi project at Harvard Medical School: resources and validation. Genetics. 201:843–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouillard AD, Gundersen GW, Fernandez NF, Wang Z, Monteiro CD, et al. 2016. The harmonizome: a collection of processed datasets gathered to serve and mine knowledge about genes and proteins. Database. 2016:baw100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ocorr K, Reeves NL, Wessells RJ, Fink M, Chen HSV, et al. 2007. KCNQ potassium channel mutations cause cardiac arrhythmias in Drosophila that mimic the effects of aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 104:3943–3948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ocorr K, Fink M, Cammarato A, Bernstein SI, Bodmer R.. 2009. Semi-automated optical heartbeat analysis of small hearts. JoVE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez C, Martínez-González J.. 2019. The role of lysyl oxidase enzymes in cardiac function and remodeling. Cells. 8:1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolski F, Błyszczuk P.. 2020. Complexity of TNF-α signaling in heart disease. JCM. 9:3267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos F, Moreira C, Nóbrega-Pereira S, Bernardes de Jesus B.. 2019. New insights into the role of epithelial–mesenchymal transition during aging. IJMS. 20:891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher SM, Prasad SVN.. 2018. Tumor necrosis factor-α in heart failure: an updated review. Curr Cardiol Rep. 20:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaposhnikov M, Proshkina E, Shilova L, Zhavoronkov A, Moskalev A.. 2015. Lifespan and stress resistance in Drosophila with overexpressed DNA repair genes. Sci Rep. 5:15299– 15212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skene NG, Roy M, Grant SG.. 2017. A genomic lifespan program that reorganises the young adult brain is targeted in schizophrenia. Elife. 6:e17915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somel M, Guo S, Fu N, Yan Z, Hu HY, et al. 2010. MicroRNA, mRNA, and protein expression link development and aging in human and macaque brain. Genome Res. 20:1207–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steppan J, Wang H, Bergman Y, Rauer MJ, Tan S, et al. 2019. Lysyl oxidase-like 2 depletion is protective in age-associated vascular stiffening. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 317: h 49–H59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taimeh Z, Loughran J, Birks EJ, Bolli R.. 2013. Vascular endothelial growth factor in heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol. 10:519–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka-Matakatsu M, Uemura T, Oda H, Takeichi M, Hayashi S.. 1996. Cadherin-mediated cell adhesion and cell motility in Drosophila trachea regulated by the transcription factor Escargot. Development. 122:3697–3705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng MS, Hsu LA, Wu S, Sun YC, Juan SH, et al. 2015. Association of CDH13 genotypes/haplotypes with circulating adiponectin levels, metabolic syndrome, and related metabolic phenotypes: the role of the suppression effect. PLoS One. 10:e0122664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkowski KL, Tester DJ, Bos JM, Haugaa KH, Ackerman MJ.. 2017. Whole exome sequencing with genomic triangulation implicates CDH2‐encoded N‐cadherin as a novel pathogenic substrate for arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Congenital Heart Disease. 12:pp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan L, Marley R, Miellet S, Hartley PS.. 2018. The impact of SPARC on age-related cardiac dysfunction and fibrosis in Drosophila. Exp Gerontol. 109:59–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verweij N, Eppinga RN, Hagemeijer Y, van der Harst P.. 2017. Identification of 15 novel risk loci for coronary artery disease and genetic risk of recurrent events, atrial fibrillation and heart failure. Sci Rep. 7:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vite A, Radice GL.. 2014. N-cadherin/catenin complex as a master regulator of intercalated disc function. Cell Commun Adhes. 21:169–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Deng Y, Zhang G, Li C, Ding G, et al. 2019. Spliced X-box binding protein 1 stimulates adaptive growth through activation of mTOR. Circulation. 140:566–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen B, Xu LY, Li EM.. 2020. LOXL2 in cancer: regulation, downstream effectors and novel roles. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA) – Rev Cancer. 1874:188435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Savvatis K, Kang JS, Fan P, Zhong H, et al. 2016. Targeting LOXL2 for cardiac interstitial fibrosis and heart failure treatment. Nat Commun. 7:13710– 13715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaffran S, Astier M, Gratecos D, Guillen A, Sémériva M.. 1995. Cellular interactions during heart morphogenesis in the Drosophila embryo. Biol Cell. 84:13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Amourda C, Garfield D, Saunders TE.. 2018. Selective filopodia adhesion ensures robust cell matching in the Drosophila heart. Dev Cell. 46:189–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Qu J, Liu GH, Belmonte JCI.. 2020. The ageing epigenome and its rejuvenation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 21:137–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Fly lines are available upon request. The authors affirm that all data necessary for confirming the conclusions of this article are represented fully within the article, its tables, and figures.

Supplementary material is available at G3 online.