Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are noncoding RNAs with 18–26 nucleotides; they pair with target mRNAs to regulate gene expression and produce significant changes in various physiological and pathological processes. In recent years, the interaction between miRNAs and their target genes has become one of the mainstream directions for drug development. As a large-scale biological database that mainly provides miRNA–target interactions (MTIs) verified by biological experiments, miRTarBase has undergone five revisions and enhancements. The database has accumulated >2 200 449 verified MTIs from 13 389 manually curated articles and CLIP-seq data. An optimized scoring system is adopted to enhance this update’s critical recognition of MTI-related articles and corresponding disease information. In addition, single-nucleotide polymorphisms and disease-related variants related to the binding efficiency of miRNA and target were characterized in miRNAs and gene 3′ untranslated regions. miRNA expression profiles across extracellular vesicles, blood and different tissues, including exosomal miRNAs and tissue-specific miRNAs, were integrated to explore miRNA functions and biomarkers. For the user interface, we have classified attributes, including RNA expression, specific interaction, protein expression and biological function, for various validation experiments related to the role of miRNA. We also used seed sequence information to evaluate the binding sites of miRNA. In summary, these enhancements render miRTarBase as one of the most research-amicable MTI databases that contain comprehensive and experimentally verified annotations. The newly updated version of miRTarBase is now available at https://miRTarBase.cuhk.edu.cn/.

INTRODUCTION

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are noncoding RNAs with around 18–26 nucleotides in length and are found in plants, fungi, animals and protozoa (1). Currently, >35 000 miRNA sequences have been identified in >270 organisms (2). Primarily in mammalian cells, miRNA can induce mRNA decapping and alkenylation via base pairing with the complementary sequence of 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) within target mRNA (3). The seed sequence in the 5′ region of miRNA is essential for binding to the target mRNA (4,5). miRNAs play a role in crucial cell activities such as cellular signaling, metabolism, cell differentiation and proliferation, and apoptosis by controlling the expression of multiple genes and are abundant in cells (6,7). More importantly, some miRNAs may become potential targets for diagnosis, prognosis and cancer treatment (8).

In recent years, the need to identify and analyze miRNA–target interactions (MTIs) and miRNA expression profiles has propelled the development of a growing number of online resources, including data warehousing and functional analysis of MTIs, to assess the biological significance of miRNAs. DIANA-TarBase includes manually curated interactions between miRNAs and genes through detailed metadata, experimental methods and conditional annotations (9). miRATBase applies a high-throughput miRNA interaction reporter assay to identify >500 target associations for four miRNAs (10). miRBase is the main miRNA sequence repository, which helps to query comprehensive miRNA name, sequence and annotation data (11). TissueAtlas presents a human miRNA tissue atlas by determining the miRNA abundance in 61 tissue biopsies (12). EVmiRNA can provide comprehensive miRNA expression profiles in extracellular vesicles, including exosomes and microvesicles (13). MiREDiBase contains information on validated and putative A-to-I (adenosine-to-inosine) and C-to-U (cytosine-to-uracil) miRNA modifications in humans (14). A vast number of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and disease-related variants (DRVs) were collected from dbSNP (15), GWAS Catalog (16), ClinVar (17) and COSMIC (18).

Various computational strategies have been published according to miRNA and target sequences to predict the target binding sites of miRNAs. However, these approaches developed based on perfect seed pairing may lead to false-positive predictions of MTIs (19). Candidate miRNA targets should always be verified experimentally, regardless of the strategies to predict miRNA–mRNA interactions. Experimental methods can be divided into two types: direct and indirect methods. Direct methods determine the interaction between a miRNA and its target by directly studying the miRNA–mRNA pairs or by introducing specific target sites that bind miRNA and reporter genes (20). Indirect methods observe the effect of high-throughput technology to derive miRNA expression from altered mRNA or protein expression (21). The sequencing data obtained from CLASH (22) and PAR-CLIP (23) can be used to explore thousands of interactions between miRNAs and their targets with expression profiles.

The miRNA–target binding can induce changes in the gene of a certain protein and indirectly affect several other genes (24). Thus, the changes of genes may not necessarily be the result of MTIs obtained by these methods. Four main biological criteria should be satisfied when predicting miRNA–mRNA target pairs through computational tools. First, the co-expression of miRNA and predicted target mRNA must be experimentally verified. Second, the demonstration of the direct interaction between the miRNA of interest and the specific region within the target mRNA should be provided. Third, experiments related to gain of function and loss of function are necessary to illustrate how miRNA regulates target protein expression. Fourth, verifying the association between predicted changes in protein expression and changes in biological functions is fundamental during experimental validation (25,26).

miRTarBase is a curated database of MTIs. Since 2011, miRTarBase has undergone five revisions and hundreds of data proofreading and system updates to integrate MTIs and molecular functions of miRNAs in various biological processes (27–31). In this update, miRTarBase aims to accumulate experimentally verified MTIs and integrate them with more miRNA expression profiles and more biological data to meet the needs of biologists. An optimized scoring system is adopted to enhance the key recognition of MTI-related articles and corresponding disease information. We have also characterized SNPs and DRVs related to the binding efficiency of miRNA and target in miRNA and gene 3′UTR and integrated miRNA expression profiles across extracellular vesicles, blood and different tissues, including exosomal miRNAs and tissue-specific miRNAs. Furthermore, the seed sequence information is provided to evaluate the binding sites between miRNA and the target gene. In improving the user-friendly interface, this update classifies miRNA-related experimentally validation methods involving different molecular levels and provides MTIs in sequence complementary status and classification levels.

SYSTEM OVERVIEW AND DATABASE CONTENT

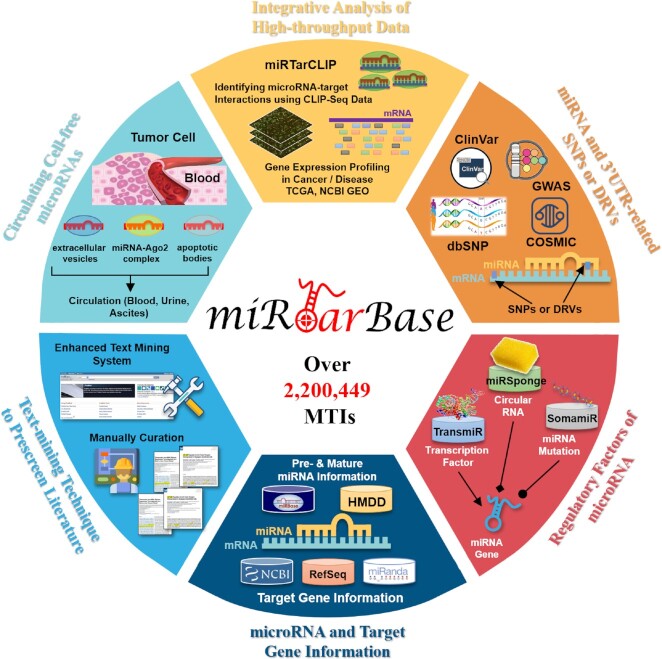

miRTarBase was first released in 2011. During this decade, the number of experimentally verified MTIs has increased dramatically and reached a significant number. At the same time, the web interface of miRTarBase has been constantly updated and enhanced to provide users with a more efficient and high-quality access experience. Aside from adding more comprehensive information on MTIs in this recent upgrade, various miRNA expression profiles and more biological data have been integrated. Such information is presented in a user-friendly, aesthetically pleasing and concise web interface. Figure 1 illustrates the current design and significant advances of miRTarBase 9.0. An optimized scoring system extracted MTIs from related articles downloaded from the PubMed literature database more efficiently. miRNA expression profiles across extracellular vesicles, blood and different tissues, and SNPs and DRVs in miRNAs and gene 3′UTRs provided insights into the specificity and heterogeneity of miRNAs and support the miRNA biomarker discovery.

Figure 1.

Highlighted improvements of miRTarBase 9.0. As the most comprehensive resource on MTIs, this update accumulates >2 200 449 manually confirmed MTIs supported with experimental evidence.

Moreover, many other biological databases were integrated, including TransmiR (32), miRSponge (33), HMDD (34), miRBase (11) and National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Entrez (35) and RefSeq (36), for information of target genes to increase the academic value of miRTarBase. In detail, miRNA regulatory information was collected from TransmiR (32) and miRSponge (33); SNPs and DRVs were collected from dbSNP (15), GWAS Catalog (16), ClinVar (17) and COSMIC (18); disease associations were obtained from HMDD (34); gene and miRNA expression profiles, including circulating and extracellular miRNAs within vesicles, were collected from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (37), The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (38,39), Circulating MicroRNA Expression Profiling (CMEP) (40), TissueAtlas (12) and EVmiRNA (13); and editing events in miRNAs were integrated from MiREDiBase (14). Table 1 shows a detailed list of databases that are integrated into miRTarBase.

Table 1.

List of the databases that are integrated by miRTarBase

| Type | Database name |

|---|---|

| Gene- and miRNA-specific databases | miRBase_22.1 (11), NCBI Entrez Gene (35), NCBI RefSeq_208 (36) |

| SNPs and DRVs | dbSNP_155 (15), GWAS Catalog_v1.0 (16), ClinVar_20210828 (17), COSMIC_v94 (18) |

| miRNA–disease association database | HMDD_v3.2 (34) |

| Regulation of miRNAs | TransmiR_v2.0 (32), miRSponge_2015 (33) |

| miRNA expression | TissueAtlas_2016 (12), EVmiRNA_2019 (13), GEO (37), TCGA (38,39), CMEP (40) |

| Editing events in miRNAs | MiREDiBase_v1.0 (14) |

UPDATED DATABASE CONTENT AND STATISTICS

Table 2 presents the updated database content of miRTarBase 9.0, such as the number of curated articles, MTIs and species. Compared with version 8.0, this update (version 9.0) has significantly increased the number of MTIs extracted from research articles and CLIP-seq data. A total of 19 912 394 experimentally validated MTIs between 4630 miRNAs and 27 172 mRNAs (target genes) were manually curated from 13 389 research articles and CLIP-seq data. Version 9.0 has implemented 440 CLIP-seq data from 44 independent studies to support the many MTIs recorded, as shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Table 2.

Improvements and the number of MTIs with different validation methods provided by miRTarBase

| Features | miRTarBase 8.0 | miRTarBase 9.0 |

|---|---|---|

| Release date | 15 September 2019 | 15 September 2021 |

| Known miRNA entry | miRBase v22 | miRBase v22 |

| Known gene entry | Entrez 2019 | Entrez 2021 |

| Species | 32 | 37 |

| Curated articles | 11 021 | 13 389 |

| miRNAs | 4312 | 4630 |

| Target genes | 23 426 | 27 172 |

| CLIP-seq datasets | 331 | 440 |

| Curated MTIs | 479 340 | 2 200 449 |

| Text mining technique to prescreen literature | Enhanced NLP+ scoring system | Enhanced NLP+ scoring system |

| Download by validated miRNA target sites | Yes | Yes |

| Browse by miRNA, gene and disease | Yes | Yes |

| Regulation of miRNAs | Yes | Yes |

| Cell-free miRNA expression | Yes | Yes |

| miRNAs in extracellular vesicles | No | Yes |

| Human miRNA tissue atlas | No | Yes |

| Editing events in miRNAs | No | Yes |

| SNPs and DRVs | No | Yes |

| MTIs supported by strong experimental evidence | ||

| Number of MTIs validated by ‘reporter assay’ | 13 922 | 16 257 |

| Number of MTIs validated by ‘western blot’ | 12 179 | 14 665 |

| Number of MTIs validated by ‘qPCR’ | 13 263 | 16 483 |

| Number of MTIs validated by ‘reporter assay and western blot’ | 10 257 | 12 171 |

| Number of MTIs validated by ‘reporter assay or western blot’ | 15 710 | 18 751 |

This update enhances the text mining system, in which the scoring system was improved and optimized to become more accurate and sensitive, greatly enhancing the recognition of MTIs and facilitating further manual collation. Information including miRNA disease association, expression values, and mRNA and miRNA sequences was updated from previously integrated databases. In addition, data from TissueAtlas (12), EVmiRNA (13), MiREDiBase (14), dbSNP (15), GWAS Catalog (16), ClinVar (17) and COSMIC (18) were integrated to improve information related to miRNA abundance in tissue biopsies, expression profiles in extracellular vesicles, miRNA modification, and SNPs and DRVs in human miRNAs and gene 3′UTRs. Moreover, this updated version categorized validation methods into four sections: (i) miRNA and mRNA co-expression; (ii) miRNA- and mRNA-specific interaction; (iii) miRNA effects on protein expression; and (iv) miRNA effects on biological function. Sequence complementary status and classification for experimental evidence were also provided.

Text mining pipeline to accelerate MTI sentences

The corresponding research literature continues to explode with the rapid development of miRNA-related bioinformatics research in recent years. Up to September 2021, the number of retrieval results on PubMed for the term miRNA exceeded 120 000. Literature searching for the relative miRNA and target gene information would be time-consuming under this circumstance. Therefore, we constructed a text mining-based model to automatically identify MTI sentences from the literature. The workflow of the model is shown in Supplementary Figure S1.

This model combines natural language processing technology and deep learning methods in two parts: feature representation and deep learning classifier. We applied the BioBERT model (41) to represent each sentence as a vector and fully exploit semantic-related information. This domain-specific language representation model was pretrained on a large-scale biomedical corpus to solve the problem that ordinary text mining methods cannot handle these medical terms well. After obtaining the representation vectors, we applied principal component analysis (42) to adjust each vector dimension to reduce dimensionality and also optimize the model performance. We have tested different dimension values and found that the model with a 100-dimension input vector obtained the best performance. Long short-term memory network is applied as the deep learning-based classifier. It contains a total of three layers: input layer, hidden layer and fully connected layer. First, the vectors obtained from the previous stage of information representation are input. Then, the vectors with fixed dimensions are fed into the hidden layer, which consists of an encoder and a decoder. Finally, the vector obtained from hidden layers is computed by the fully connected layer to obtain the scores of sentences on each class, and the label with the highest score is selected as the output result. The accuracy of the model exceeds 82%. Then, we apply the model to enhance the recognition of MTIs and facilitate further manual collation.

SNPs and disease-related variations in miRNAs and miRNA targets

SNPs or variants could destroy or modify the efficiency of miRNA binding to the 3′UTR of a gene, resulting in gene dysregulation. Thus far, SNPs in miRNA binding sites are associated with multiple cancer subtypes, and various resources have been developed to assess the effects of variation on miRNA and determine how they alter secondary structure and targeting. In this update, we have characterized SNPs and DRVs from dbSNP (14), GWAS Catalog (15), ClinVar (16) and COSMIC (17) related to the binding efficiency of miRNA and target in miRNA and gene 3′UTR.

Exosomal miRNAs and tissue-specific miRNAs

Increasing evidence has shown that miRNAs can significantly affect the radiation response (43), where exosome-bound circulating miRNAs of tumor tissues or body fluids are considered to be related to radiosensitivity with high potential in predicting clinical response (44). Exosomes are small membrane-derived vesicles that can be released by a variety of cell types; these exosome-derived miRNAs offer exceptional prospects in radiology and cancer research (45). They not only carry different cargoes, including miRNA, mRNA and proteins used explicitly for cell-to-cell communication (46,47), but also clarify that the miRNA profile of exosomes can be altered under the influence of radiation and these radiation-related miRNAs may affect the proliferation and radiosensitivity of cancer cells (45). Here, we collected comprehensive miRNA expression profiles in extracellular vesicles and human tissues by integrating EVmiRNA (13) and TissueAtlas (12), respectively.

Accumulated CLIP-seq data

Recent advances in high-throughput sequencing of immunoprecipitated RNAs after cross-linking (CLIP-seq, HITS-CLIP, PAR-CLIP, CLASH, and iCLIP) provide a powerful approach to identify biologically relevant MTIs (48,49). miRNAs bind to their corresponding target sites by coupling with Argonaute family proteins and induce mRNA degradation and translational repression. Therefore, CLIP-seq can identify miRNAs and targets that are part of the Ago silencing complex. The increasing CLIP-seq data available on public biological databases should be integrated into miRTarBase to explore novel MTIs.

In this miRTarBase updated version, 440 CLIP-seq datasets (Table 3 and Supplementary Table S1) are retrieved from GEO and analyzed through a systematic tool called miRTarCLIP (50) developed by our laboratory to mine MTIs, which contribute to 19 900 906 MTIs to update the database. Besides, to facilitate the annotation, visualization, analysis and discovery of these MTIs from large-scale CLIP-seq data, we optimized the search and search result pages by adding the ‘CLIP-seq (analyzed by miRTarCLIP)’ column and modifying the dataset information display in CLIP-seq viewer page, providing a more concise interface to explore CLIP-seq-supported MTIs to users.

Table 3.

CLIP-seq datasets from GEO that are incorporated into miRTarBase

| Species | Number of experiments | Number of tissues/cell lines | Number of MTIs | Publication date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | 324 | 30 | 1 774 829 | Until 1 September 2021 |

| Mouse | 116 | 9 | 411 683 |

miRNA-mediated gene regulatory network

miRNAs can regulate gene expression by post-transcriptional regulation mechanism, and their expression can be mediated by an upstream transcription factor and circular RNA (51–56). A comprehensive investigation of miRNA expression profiles in extracellular vesicles or tissues will be helpful to explore their functions and biomarkers. Recent studies suggested that instead of being mediated by regulators, miRNA–mRNA binding affinity and miRNA expression are affected by SNPs and variations (57,58). Thus, this update aims to provide an extended platform for investigating the regulation mechanism of miRNAs by constructing the regulatory networks among miRNAs, regulators and targets. We also reveal distribution of miRNA expression across tissues or extracellular vesicles, and SNPs and DRVs harbored in miRNAs or gene 3′UTRs, which could relate to disease causation.

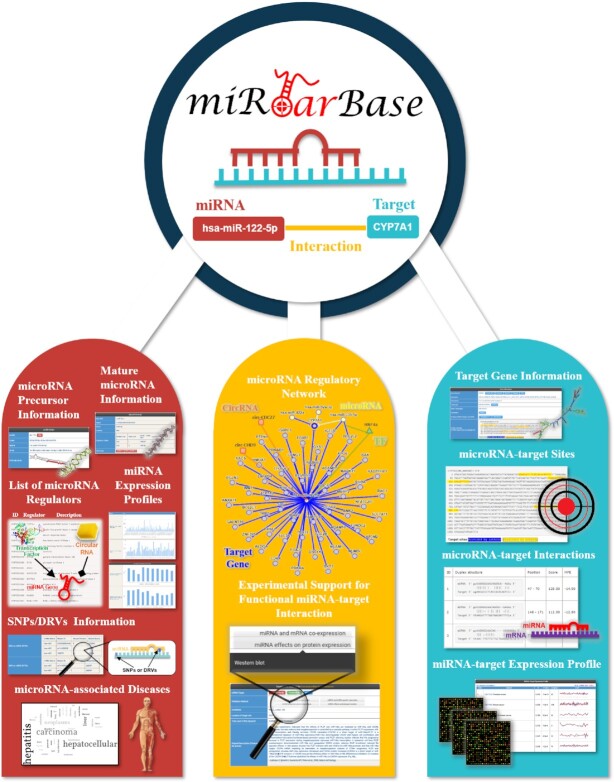

ENHANCED WEB INTERFACE

The previous version provided a user-friendly, snappy and aesthetically pleasing interface for biologists to investigate MTIs, miRNA regulators and miRNA regulatory networks. However, improvements were implemented to satisfy the need to present newly added data. As presented in Figure 2, the web interface has been updated with several new feature areas and a user-friendly interface. Users can search for miRNA expression profiles based on different categories: (i) circulation miRNA expression profiling; (ii) miRNAs in extracellular vesicles; and (iii) human miRNA tissue atlas. Users can also directly explore SNPs and DRVs of miRNA and interaction sites on the corresponding sequence. The layout of the validation method has been rearranged and grouped into four major categories.

Figure 2.

Enhanced web interface of miRTarBase. More comprehensive information related to miRNAs, such as miRNA precursor, mature miRNA information, miRNA-associated diseases, miRNA regulators, supporting evidence, display of miRNA regulatory network, target gene information, miRNA target sites and the expression profiles of miRNAs and their targets, is provided on the web interface of miRTarBase.

The scientific contribution of miRTarBase

The function of miRNA is primarily defined by its gene targets, but reliably identifying MTIs from a significant data source remains challenging. We developed the first version of miRTarBase in 2011 and made four updates over the years, specifically in 2014 (version 4), 2016 (version 6), 2017 (version 7) and 2020 (version 8). As mentioned earlier, users may freely retrieve all experimentally validated targets for a specific miRNA of interest. Interestingly, articles citing miRTarBase are spread across many different fields, but the top two citation fields alternate between ‘biochemistry and molecular biology’ and ‘oncology’ for all miRTarBase versions and ‘genetics and heredity’ usually follows right after. miRNA regulation and target interaction are essential in understanding disease progression. The updated miRTarBase helps integrate regulators and targets and provides known experimentally validated MTIs to investigate miRNA regulation by providing a new web query interface.

Furthermore, by integrating the experimentally validated public miRNA and target interaction database, miRTarBase built an osteoarthritis-specific miRNA interactome expressing the gene in cartilage affected by miRNA (59). miRTarBase provides a flexible way of searching for miRNA, the gene of interest and related diseases. For example, as we search for hsa-miR-122-5p, the information of major related diseases will be displayed; in this case, this miRNA is mainly related to liver diseases, including hepatocellular carcinoma, and shows a significant negative correlation to disease progression in TCGA data and independent studies. Collectively, by filtering known MTIs present in miRTarBase, we can discover novel MTIs within our disease of interest and obtain details of miRNA regulation.

The role of miRNAs in coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic has been studied using bioinformatics methods and high-throughput sequencing of patients to reveal upregulated and downregulated miRNAs, such as miR-16-2-3p and miR-183-5p; the functional enrichments for the predicted targets of miRNA using miRTarBase indicate the involvement of miRNAs in processes, such as virus binding and defense response (60). Therefore, changes involving or including these miRNAs prove to have potential as biomarkers for disease diagnosis and treatment.

Taken together, miRTarBase will be helpful for scientists to seek miRNA targets of high confidence for MTIs involved in disease progression. With the rapid development of sequencing technologies, miRTarBase acts as a potent tool that is updated regularly to keep up with the increasingly large data of all known experimentally validated MTIs for over 20 kinds of diseases and plants.

SUMMARY AND PERSPECTIVES

MiRTarBase has provided scientists with a high-quality, high-performance, reference-value, convenient-to-use biological database in the past decade. So far, miRTarBase 9.0 contains >13 389 articles that provide experimental evidence to support MTI, involving 27 172 target genes from 37 species. With the increasing number of CLIP-seq datasets, the number of MTIs currently covered by miRTarBase is close to 19 912 394. miRTarBase provides users with a more efficient experience by using natural language technology to collect comprehensive targeting relationships and network functions and annotation information, integrate useful data content and improve miRNA regulation-related information. The database also allows using miRNAs to regulate target gene information and performance trends and analyzes miRNAs in regulating specific biological metabolic pathways and the pathogenesis of different cancers or complex diseases. miRTarBase can be applied to miRNA-related disease treatment and drug development. This database will be constantly updated in the future to continue providing a reliable database platform for the majority of scientific researchers and the science community.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The miRTarBase 9.0 database will be continuously maintained and updated. The database is now publicly accessible at https://miRTarBase.cuhk.edu.cn/.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Hsi-Yuan Huang, The Genetics Laboratory, Longgang District Maternity & Child Healthcare Hospital of Shenzhen City, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China; School of Life and Health Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China; Warshel Institute for Computational Biology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China.

Yang-Chi-Dung Lin, The Genetics Laboratory, Longgang District Maternity & Child Healthcare Hospital of Shenzhen City, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China; School of Life and Health Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China; Warshel Institute for Computational Biology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China.

Shidong Cui, School of Life and Health Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China; Warshel Institute for Computational Biology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China.

Yixian Huang, School of Life and Health Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China; Warshel Institute for Computational Biology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China.

Yun Tang, School of Life and Health Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China; Warshel Institute for Computational Biology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China.

Jiatong Xu, School of Life and Health Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China; Warshel Institute for Computational Biology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China.

Jiayang Bao, Division of Biological Sciences, Section of Bioinformatics, University of California, San Diego, San Diego, CA 92093, USA.

Yulin Li, School of Life and Health Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China; Warshel Institute for Computational Biology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China.

Jia Wen, School of Life and Health Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China; Warshel Institute for Computational Biology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China.

Huali Zuo, School of Life and Health Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China; Warshel Institute for Computational Biology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China; School of Computer Science and Technology, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei 230027, China.

Weijuan Wang, School of Life and Health Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China; Warshel Institute for Computational Biology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China.

Jing Li, School of Life and Health Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China; Warshel Institute for Computational Biology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China.

Jie Ni, Warshel Institute for Computational Biology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China.

Yini Ruan, Warshel Institute for Computational Biology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China.

Liping Li, Warshel Institute for Computational Biology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China.

Yidan Chen, School of Life and Health Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China; Warshel Institute for Computational Biology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China.

Yueyang Xie, Warshel Institute for Computational Biology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China.

Zihao Zhu, School of Life and Health Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China; Warshel Institute for Computational Biology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China.

Xiaoxuan Cai, School of Life and Health Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China; Warshel Institute for Computational Biology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China.

Xinyi Chen, School of Life and Health Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China; Warshel Institute for Computational Biology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China.

Lantian Yao, Warshel Institute for Computational Biology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China; School of Science and Engineering, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong 518172, China.

Yigang Chen, School of Life and Health Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China; Warshel Institute for Computational Biology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China.

Yijun Luo, School of Life and Health Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China; Warshel Institute for Computational Biology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China.

Shupeng LuXu, School of Life and Health Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China; Warshel Institute for Computational Biology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China.

Mengqi Luo, School of Life and Health Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China; Warshel Institute for Computational Biology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China.

Chih-Min Chiu, School of Life and Health Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China; Warshel Institute for Computational Biology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China.

Kun Ma, Warshel Institute for Computational Biology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China.

Lizhe Zhu, School of Life and Health Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China; Warshel Institute for Computational Biology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China.

Gui-Juan Cheng, School of Life and Health Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China; Warshel Institute for Computational Biology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China.

Chen Bai, School of Life and Health Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China; Warshel Institute for Computational Biology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China.

Ying-Chih Chiang, Kobilka Institute of Innovative Drug Discovery, School of Life and Health Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong 518172, China.

Liping Wang, Department of Reproductive Medicine Centre, Shenzhen Second People’s Hospital, The First Affiliated Hospital of Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, Guangdong 518035, China.

Fengxiang Wei, The Genetics Laboratory, Longgang District Maternity & Child Healthcare Hospital of Shenzhen City, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China; Department of Cell Biology, Jiamusi University, Jiamusi, Heilongjiang 154007, China; Shenzhen Children’s Hospital of China Medical University, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China.

Tzong-Yi Lee, School of Life and Health Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China; Warshel Institute for Computational Biology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China.

Hsien-Da Huang, The Genetics Laboratory, Longgang District Maternity & Child Healthcare Hospital of Shenzhen City, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China; School of Life and Health Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China; Warshel Institute for Computational Biology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518172, China.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

National Natural Science Foundation of China [32070674, 32070659]; Key Program of Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Fund (Guangdong–Shenzhen Joint Fund) [2020B1515120069]; Shenzhen City and Longgang District for the Warshel Institute for Computational Biology; Ganghong Young Scholar Development Fund [2021E0005, 2021E007]; Science, Technology and Innovation Commission of Shenzhen Municipality [JCYJ20200109150003938]; Guangdong Province Basic and Applied Basic Research Fund [2021A1515012447]; Basic research project of Shenzhen Science and Technology Research Projects [JCYJ20190808102405474]. Funding for open access charge: Shenzhen City and Longgang District for the Warshel Institute for Computational Biology.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bartel D.P. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004; 116:281–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kozomara A., Birgaoanu M., Griffiths-Jones S.. miRBase: from microRNA sequences to function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47:D155–D162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stroynowska-Czerwinska A., Fiszer A., Krzyzosiak W.J.. The panorama of miRNA-mediated mechanisms in mammalian cells. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2014; 71:2253–2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bartel D.P. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009; 136:215–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shukla G.C., Singh J., Barik S.. MicroRNAs: processing, maturation, target recognition and regulatory functions. Mol. Cell. Pharmacol. 2011; 3:83–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen J.F., Mandel E.M., Thomson J.M., Wu Q., Callis T.E., Hammond S.M., Conlon F.L., Wang D.Z.. The role of microRNA-1 and microRNA-133 in skeletal muscle proliferation and differentiation. Nat. Genet. 2006; 38:228–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shivdasani R.A. MicroRNAs: regulators of gene expression and cell differentiation. Blood. 2006; 108:3646–3653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jiao X., Qian X., Wu L., Li B., Wang Y., Kong X., Xiong L.. microRNA: the impact on cancer stemness and therapeutic resistance. Cells. 2019; 9:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vlachos I.S., Paraskevopoulou M.D., Karagkouni D., Georgakilas G., Vergoulis T., Kanellos I., Anastasopoulos I.L., Maniou S., Karathanou K., Kalfakakou D.et al.. DIANA-TarBase v7.0: indexing more than half a million experimentally supported miRNA:mRNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015; 43:D153–D159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kern F., Krammes L., Danz K., Diener C., Kehl T., Kuchler O., Fehlmann T., Kahraman M., Rheinheimer S., Aparicio-Puerta E.et al.. Validation of human microRNA target pathways enables evaluation of target prediction tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021; 49:127–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kozomara A., Griffiths-Jones S.. miRBase: annotating high confidence microRNAs using deep sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014; 42:D68–D73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ludwig N., Leidinger P., Becker K., Backes C., Fehlmann T., Pallasch C., Rheinheimer S., Meder B., Stahler C., Meese E.et al.. Distribution of miRNA expression across human tissues. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016; 44:3865–3877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu T., Zhang Q., Zhang J., Li C., Miao Y.R., Lei Q., Li Q., Guo A.Y.. EVmiRNA: a database of miRNA profiling in extracellular vesicles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47:D89–D93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Marceca G.P., Distefano R., Tomasello L., Lagana A., Russo F., Calore F., Romano G., Bagnoli M., Gasparini P., Ferro A.et al.. MiREDiBase, a manually curated database of validated and putative editing events in microRNAs. Sci. Data. 2021; 8:199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sherry S.T., Ward M.H., Kholodov M., Baker J., Phan L., Smigielski E.M., Sirotkin K.. dbSNP: the NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001; 29:308–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Buniello A., MacArthur J.A.L., Cerezo M., Harris L.W., Hayhurst J., Malangone C., McMahon A., Morales J., Mountjoy E., Sollis E.et al.. The NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog of published genome-wide association studies, targeted arrays and summary statistics 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47:D1005–D1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Landrum M.J., Chitipiralla S., Brown G.R., Chen C., Gu B., Hart J., Hoffman D., Jang W., Kaur K., Liu C.et al.. ClinVar: improvements to accessing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020; 48:D835–D844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tate J.G., Bamford S., Jubb H.C., Sondka Z., Beare D.M., Bindal N., Boutselakis H., Cole C.G., Creatore C., Dawson E.et al.. COSMIC: the Catalogue Of Somatic Mutations In Cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47:D941–D947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Didiano D., Hobert O.. Perfect seed pairing is not a generally reliable predictor for miRNA–target interactions. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006; 13:849–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kuhn D.E., Martin M.M., Feldman D.S., Terry A.V. Jr, Nuovo G.J., Elton T.S. Experimental validation of miRNA targets. Methods. 2008; 44:47–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee Y.J., Kim V., Muth D.C., Witwer K.W.. Validated microRNA target databases: an evaluation. Drug Dev. Res. 2015; 76:389–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Helwak A., Kudla G., Dudnakova T., Tollervey D. Mapping the human miRNA interactome by CLASH reveals frequent noncanonical binding. Cell. 2013; 153:654–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hafner M., Landthaler M., Burger L., Khorshid M., Hausser J., Berninger P., Rothballer A., Ascano M. Jr, Jungkamp A.C., Munschauer Met al.. Transcriptome-wide identification of RNA-binding protein and microRNA target sites by PAR-CLIP. Cell. 2010; 141:129–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ritchie W., Rasko J.E.. Refining microRNA target predictions: sorting the wheat from the chaff. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014; 445:780–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Elton T.S., Yalowich J.C.. Experimental procedures to identify and validate specific mRNA targets of miRNAs. EXCLI J. 2015; 14:758–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Riolo G., Cantara S., Marzocchi C., Ricci C.. miRNA targets: from prediction tools to experimental validation. Methods Protoc. 2020; 4:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chou C.H., Chang N.W., Shrestha S., Hsu S.D., Lin Y.L., Lee W.H., Yang C.D., Hong H.C., Wei T.Y., Tu S.J.et al.. miRTarBase 2016: updates to the experimentally validated miRNA–target interactions database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016; 44:D239–D247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chou C.H., Shrestha S., Yang C.D., Chang N.W., Lin Y.L., Liao K.W., Huang W.C., Sun T.H., Tu S.J., Lee W.H.et al.. miRTarBase update 2018: a resource for experimentally validated microRNA–target interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018; 46:D296–D302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hsu S.D., Lin F.M., Wu W.Y., Liang C., Huang W.C., Chan W.L., Tsai W.T., Chen G.Z., Lee C.J., Chiu C.M.et al.. miRTarBase: a database curates experimentally validated microRNA–target interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011; 39:D163–D169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hsu S.D., Tseng Y.T., Shrestha S., Lin Y.L., Khaleel A., Chou C.H., Chu C.F., Huang H.Y., Lin C.M., Ho S.Y.et al.. miRTarBase update 2014: an information resource for experimentally validated miRNA–target interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014; 42:D78–D85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Huang H.Y., Lin Y.C., Li J., Huang K.Y., Shrestha S., Hong H.C., Tang Y., Chen Y.G., Jin C.N., Yu Y.et al.. miRTarBase 2020: updates to the experimentally validated microRNA–target interaction database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020; 48:D148–D154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tong Z., Cui Q., Wang J., Zhou Y.. TransmiR v2.0: an updated transcription factor–microRNA regulation database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47:D253–D258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wang P., Zhi H., Zhang Y., Liu Y., Zhang J., Gao Y., Guo M., Ning S., Li X.. miRSponge: a manually curated database for experimentally supported miRNA sponges and ceRNAs. Database. 2015; 2015:bav098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Huang Z., Shi J., Gao Y., Cui C., Zhang S., Li J., Zhou Y., Cui Q.. HMDD v3.0: a database for experimentally supported human microRNA–disease associations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47:D1013–D1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Maglott D., Ostell J., Pruitt K.D., Tatusova T.. Entrez Gene: gene-centered information at NCBI. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011; 39:D52–D57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. O’Leary N.A., Wright M.W., Brister J.R., Ciufo S., Haddad D., McVeigh R., Rajput B., Robbertse B., Smith-White B., Ako-Adjei D.et al.. Reference sequence (RefSeq) database at NCBI: current status, taxonomic expansion, and functional annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016; 44:D733–D745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Barrett T., Wilhite S.E., Ledoux P., Evangelista C., Kim I.F., Tomashevsky M., Marshall K.A., Phillippy K.H., Sherman P.M., Holko M.et al.. NCBI GEO: archive for functional genomics data sets—update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013; 41:D991–D995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Deng M., Bragelmann J., Schultze J.L., Perner S.. Web-TCGA: an online platform for integrated analysis of molecular cancer data sets. BMC Bioinformatics. 2016; 17:72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tomczak K., Czerwinska P., Wiznerowicz M.. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA): an immeasurable source of knowledge. Contemp. Oncol. (Pozn). 2015; 19:A68–A77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Li J.R., Tong C.Y., Sung T.J., Kang T.Y., Zhou X.J., Liu C.C.. CMEP: a database for circulating microRNA expression profiling. Bioinformatics. 2019; 35:3127–3132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lee J., Yoon W., Kim S., Kim D., Kim S., So C.H., Kang J.. BioBERT: a pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. Bioinformatics. 2020; 36:1234–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Groth D., Hartmann S., Klie S., Selbig J.. Principal components analysis. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013; 930:527–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Czochor J.R., Glazer P.M.. microRNAs in cancer cell response to ionizing radiation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014; 21:293–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sun Y., Hawkins P.G., Bi N., Dess R.T., Tewari M., Hearn J.W.D., Hayman J.A., Kalemkerian G.P., Lawrence T.S., Ten Haken R.K.et al.. Serum microRNA signature predicts response to high-dose radiation therapy in locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2018; 100:107–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Malla B., Zaugg K., Vassella E., Aebersold D.M., Dal Pra A.. Exosomes and exosomal microRNAs in prostate cancer radiation therapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2017; 98:982–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Vanni I., Alama A., Grossi F., Dal Bello M.G., Coco S. Exosomes: a new horizon in lung cancer. Drug Discov. Today. 2017; 22:927–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Long L., Zhang X., Bai J., Li Y., Wang X., Zhou Y.. Tissue-specific and exosomal miRNAs in lung cancer radiotherapy: from regulatory mechanisms to clinical implications. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019; 11:4413–4424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bottini S., Pratella D., Grandjean V., Repetto E., Trabucchi M.. Recent computational developments on CLIP-seq data analysis and microRNA targeting implications. Brief. Bioinform. 2018; 19:1290–1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Konig J., Zarnack K., Luscombe N.M., Ule J.. Protein–RNA interactions: new genomic technologies and perspectives. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012; 13:77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chou C.H., Lin F.M., Chou M.T., Hsu S.D., Chang T.H., Weng S.L., Shrestha S., Hsiao C.C., Hung J.H., Huang H.D.. A computational approach for identifying microRNA–target interactions using high-throughput CLIP and PAR-CLIP sequencing. BMC Genomics. 2013; 14:S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Murakami Y., Yasuda T., Saigo K., Urashima T., Toyoda H., Okanoue T., Shimotohno K.. Comprehensive analysis of microRNA expression patterns in hepatocellular carcinoma and non-tumorous tissues. Oncogene. 2006; 25:2537–2545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chen X., Ba Y., Ma L., Cai X., Yin Y., Wang K., Guo J., Zhang Y., Chen J., Guo X.et al.. Characterization of microRNAs in serum: a novel class of biomarkers for diagnosis of cancer and other diseases. Cell Res. 2008; 18:997–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Liu R., Chen X., Du Y., Yao W., Shen L., Wang C., Hu Z., Zhuang R., Ning G., Zhang C.et al.. Serum microRNA expression profile as a biomarker in the diagnosis and prognosis of pancreatic cancer. Clin. Chem. 2012; 58:610–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Eisenberg I., Eran A., Nishino I., Moggio M., Lamperti C., Amato A.A., Lidov H.G., Kang P.B., North K.N., Mitrani-Rosenbaum S.et al.. Distinctive patterns of microRNA expression in primary muscular disorders. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007; 104:17016–17021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hunter M.P., Ismail N., Zhang X., Aguda B.D., Lee E.J., Yu L., Xiao T., Schafer J., Lee M.L., Schmittgen T.D.et al.. Detection of microRNA expression in human peripheral blood microvesicles. PLoS One. 2008; 3:e3694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Li L.M., Hu Z.B., Zhou Z.X., Chen X., Liu F.Y., Zhang J.F., Shen H.B., Zhang C.Y., Zen K.. Serum microRNA profiles serve as novel biomarkers for HBV infection and diagnosis of HBV-positive hepatocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2010; 70:9798–9807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ryan B.M., Robles A.I., Harris C.C.. Genetic variation in microRNA networks: the implications for cancer research. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2010; 10:389–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Galka-Marciniak P., Urbanek-Trzeciak M.O., Nawrocka P.M., Dutkiewicz A., Giefing M., Lewandowska M.A., Kozlowski P.. Somatic mutations in miRNA genes in lung cancer-potential functional consequences of non-coding sequence variants. Cancers (Basel). 2019; 11:793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. de Almeida R.C., Ramos Y.F., Mahfouz A., Hollander W., Lakenberg N., Houtman E., van Hoolwerff M., Suchiman H.E.D., Ruiz A.R., Slagboom P.E.et al.. RNA sequencing data integration reveals an miRNA interactome of osteoarthritis cartilage. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2019; 78:270–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zhang S., Amahong K., Sun X., Lian X., Liu J., Sun H., Lou Y., Zhu F., Qiu Y.. The miRNA: a small but powerful RNA for COVID-19. Brief. Bioinform. 2021; 22:1137–1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The miRTarBase 9.0 database will be continuously maintained and updated. The database is now publicly accessible at https://miRTarBase.cuhk.edu.cn/.