Abstract

The Protein Data Bank in Europe – Knowledge Base (PDBe-KB, https://pdbe-kb.org) is an open collaboration between world-leading specialist data resources contributing functional and biophysical annotations derived from or relevant to the Protein Data Bank (PDB). The goal of PDBe-KB is to place macromolecular structure data in their biological context by developing standardised data exchange formats and integrating functional annotations from the contributing partner resources into a knowledge graph that can provide valuable biological insights. Since we described PDBe-KB in 2019, there have been significant improvements in the variety of available annotation data sets and user functionality. Here, we provide an overview of the consortium, highlighting the addition of annotations such as predicted covalent binders, phosphorylation sites, effects of mutations on the protein structure and energetic local frustration. In addition, we describe a library of reusable web-based visualisation components and introduce new features such as a bulk download data service and a novel superposition service that generates clusters of superposed protein chains weekly for the whole PDB archive.

INTRODUCTION

The structure of biological macromolecules and their complexes is invaluable for understanding their functions (1,2). These structures allow researchers to infer atomic-level mechanisms of biological systems and enable them to modulate biological processes through, for example, structure-based drug design, synthetic biology, and protein engineering (3–5).

For 50 years, the Protein Data Bank (PDB), managed by the worldwide Protein Data Bank consortium (wwPDB) (6), has served as the global archive for experimentally determined structures. To date, the PDB contains over 180 000 structures of 55 000 distinct proteins, with around 12 000 new PDB entries deposited annually (7). Advances in structure determination promise that the repertoire of known structures will continue to grow, mainly owing to the widespread application of single-particle cryo-electron microscopy yielding high-resolution structures. Nevertheless, the known sequence space is expanding even faster (8); only 0.27% of protein sequences in the Universal Protein Data Resource (UniProt) has structural representations in the PDB. This gap between the knowledge of sequences and structures will continue to grow (6,9–11). Although high-accuracy predicted models made public recently have the potential to expand the structural coverage of the sequence space massively, these methods still have limitations in modelling mutant structures and assemblies (12–14).

While macromolecular structures are invaluable, they often need to be interpreted using additional structural and functional annotation layers to answer specific biological questions (15). For example, annotating structures with druggable surface pockets, molecular channels or identifying residues critical for stabilising an interaction interface can give more in-depth insights than 3D coordinates alone (16–18).

Many specialist data resources, and scientific software provide such annotations, and their number keeps growing (15). However, while having access to such a rich ecosystem of annotations empowers the scientific community, it is becoming increasingly difficult to track and combine these data. While most annotations are openly accessible, they may not be easily findable, and the lack of standard data formats often hinders interoperability and reusability.

We established PDBe-KB in 2018 to make these annotations FAIR (i.e. findable, accessible, interoperable, reusable) through a global collaboration between PDBe and leading specialist data providers and scientific software developers (15). This collaborative consortium aims to place macromolecular structures in their biological context by providing FAIR access to structural, functional and biophysical annotations of protein, nucleic acid and small-molecule structures in the PDB.

PDBe-KB is an open consortium transparently governed by a collaboration guideline (https://pdbe-kb.org/guidelines). Contributing data resources are requested to provide their PDB residue or PDB chain annotations in a data format defined and maintained by the consortium (https://github.com/PDBe-KB/funpdbe-schema). This data exchange format evolves according to the partner resources' requirements, and the consortium reviews the specification during annual PDBe-KB workshops. In addition, PDBe-KB makes the integrated annotations openly accessible to the scientific community through file transfer protocol (ftp://ftp.ebi.ac.uk/pub/databases/pdbe-kb), programmatic access (https://pdbe-kb.org/graph-api) and web pages (https://pdbe-kb.org/proteins). As a result, the consortium grew from 18 to 30 collaborating data resources from 11 different countries in the past two years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Data resources and scientific software contributing annotations to PDBe-KB

| Partner resource | Resource leader | Type of annotations | Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| 14–3–3-Pred (19) | G. Barton | Binding site predictions | GBR |

| 3D Complex (20) | E. D. Levy, S. Dey | Interaction interfaces | ISR |

| 3DLigandSite (21) | M. Wass | Binding site predictions | GBR |

| AKID (22) | M. Helmer-Citterich | Kinase-target predictor | ITA |

| Arpeggio (23) | T. Blundell | Ligand interactions | GBP |

| CamKinet (in preparation) | M. Kumar | Curated post-translational modification sites | DEU |

| canSAR (16) | B. al-Lazikani | Druggable pocket predictions | GBR |

| CATH-FunSites (24) | C. Orengo | Functional site predictions | GBR |

| ChannelsDB (18) | R. Svobodova, K.Berka | Molecular channels | CZE |

| COSPI-Depth (25) | M. S. Madhusudhan | Residue depth | IND |

| Covalentizer (26) (new) | N. London | Predicted covalent binding molecules | ISR |

| DynaMine (27) | W. Vranken | Backbone flexibility predictions | BEL |

| ELM (28) | T. Gibson | Short linear motifs | DEU |

| EMV (29) (new) | J. R. Macias | EM validation annotations from 3DBionotes | ESP |

| EVcouplings (30) (new) | D. Marks | Covariations | USA |

| FireProt DB (31) (new) | J. Damborsky | Effects of mutations on protein stabilities | CZE |

| FoldX (32) | L. Serrano | Energetic consequences of mutations | ESP |

| FrustratometeR (33)(new) | R. Gonzalo Parra | Energetic local frustration | ESP |

| KinCore (34) (new) | R. Dunbrack | Conformational annotations | USA |

| KnotProt (35) (new) | J. Sulkowska | Topology annotations | POL |

| M-CSA (36) | J. Thornton | Curated catalytic sites | GBR |

| MetalPDB (37) | C. Andreini, A. Rosato | Curated metal-binding sites | ITA |

| Missense3D (38) | M. Sternberg | Mutations in human proteome | GBR |

| MobiDB (39) (new) | S. Tosatto | Consensus disorder predictions | ITA |

| P2rank (40) | D. Hoksza | Binding site predictions | CZE |

| POPS (41) | F. Fraternali | Solvent accessibility | GBR |

| ProKinO (42) | N. Kannan | Curated post-translational modification sites | USA |

| Scop3P (43) (new) | L. Martens, W. Vranken | Phosphorylation sites | BEL |

| SKEMPI (44) (new) | J. Fernandez-Recio | Thermodynamic effects of mutations | ESP |

| WEBnm@ (45) (new) | N. Reuter | Flexibility predictions | NOR |

PDBe-KB integrates annotations from 30 partner resources who provide functional, biophysical and biochemical annotations.

IMPLEMENTATION

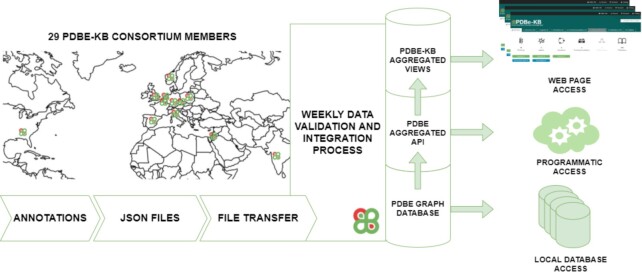

The infrastructure of PDBe-KB consists of four main components. These are (i) a deposition system for annotations; (ii) a graph database that integrates annotations with the core PDB data; (iii) a rich set of application programming interface (API) endpoints that provide access to the data; (iv) a set of reusable web components that are combined to create the PDBe-KB aggregated views (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the PDBe-KB infrastructure. PDBe-KB partner resources convert their annotations to a predefined JSON format and transfer these file sets via FTP. Weekly data validation and integration processes parse and load the annotations into the PDBe graph database. A rich set of API endpoints expose the data and power the PDBe-KB aggregated views. Researchers can access the data by setting up a local instance of the graph database, using the API endpoints, or visiting the aggregated view pages.

Data deposition

The data deposition system changed significantly to ensure scalability as more partner data resources joined the consortium. Data providers are required to convert their annotations to JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) files, according to the data exchange format specification, which is available at https://github.com/PDBe-KB/funpdbe-schema. Collaborators then copy their JSON files to private FTP areas provided by PDBe-KB, hosted at EMBL-EBI in Hinxton. A weekly running data processing pipeline parses, validates and integrates the data from these JSON files into the PDBe graph database. When displaying or providing access to annotations from any PDBe-KB partner resources, we provide direct links the users can follow to find the original data set from the corresponding database or scientific software.

Data access

The PDBe graph database is an up-to-date knowledge graph that contains the latest PDB data, linked to the corresponding UniProt accessions and integrated with structural, functional and biophysical annotations. It is implemented in Neo4j v3.5 and has over 1 billion nodes and 1.5 billion edges. The database is openly accessible at https://pdbe-kb.org/graph-download, and users can install it in-house to use it as a research tool for data mining. It requires ∼0.5TB of local storage space, preferably on an SSD drive with a recommended 6 GB RAM and eight cores.

The PDBe aggregated API provides programmatic access to all the aspects of the data contained within the graph database. As we integrated new annotations into PDBe-KB, we have expanded the API and currently provide over 90 different API endpoints. We have described these endpoints and provided use case examples elsewhere (46). The API is available at https://pdbe-kb.org/graph-api.

Web components library

PDBe-KB web pages use modular web components which can be reused and customised easily. We have created an open-source library for these components so that data service developers can use them as plugins for visualising structural data. In addition, they provide built-in support for the PDBe aggregated API, allowing developers to display data from PDBe-KB conveniently. We implemented the web components using the AngularJS framework. They are available and freely reusable from GitHub at https://github.com/PDBe-KB?q=component.

New features on the aggregated views of proteins

We continuously develop the PDBe-KB pages, displaying all the available structural information for a protein, keyed on a UniProt accession. We call these pages aggregated views of proteins. In addition, we have added several features, in particular: (i) a superposition service to visualise protein chains clustered by structural similarity; (ii) a bulk download service that provides easy access to all the coordinate files, validation reports, sequences for a protein of interest; (iii) a section dedicated to processed proteins and (iv) annotations for small molecules and macromolecular interaction partners.

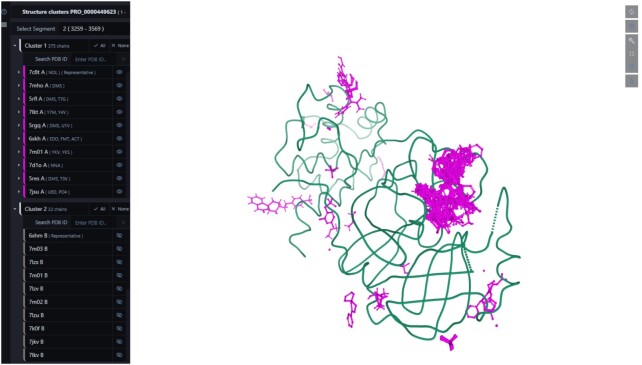

We have designed a weekly process to generate superposed UniProt segments for the whole PDB archive. We described the details of the data process on the public Wiki pages of PDBe-KB at https://github.com/PDBe-KB/pdbe-kb-manual/wiki/Superposition. The superposed coordinates are made available on the aggregated views of proteins, where clustered, superposed PDB chains can be displayed using the interactive 3D molecular viewer, Mol* (47), by clicking on the ‘view structure clusters’ buttons. We also provide a unique superposition view that displays all the ligand molecules overlaid on representative chains from superposition clusters (Figure 2). In the example below, we display the 3C-like proteinase nsp5 of SARS-CoV-2. By overlaying all the bound small molecules, researchers can identify a frequently populated binding pocket.

Figure 2.

Superposition of protein chains and ligand molecules. The aggregated views of proteins provide access to superposed protein segments and offer a display mode that overlays all the observed ligands on representative chains from superposition clusters. The figure displays the ligand superposition of all the available small molecules in PDB structures of the 3C-like proteinase nsp5 of SARS-CoV-2.

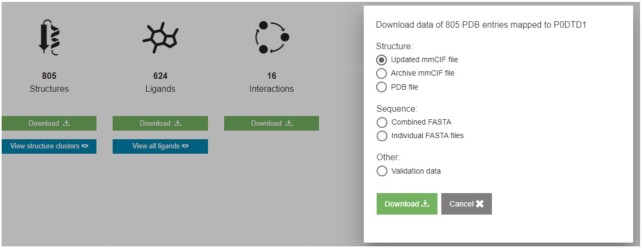

Previously, it was cumbersome to download all the structural and functional data available for a protein of interest from its aggregated view. We have recently designed a download service that has a graphical user interface to enable users to download coordinates (archive mmCIF, updated mmCIF and PDB format), sequences (FASTA format) and validation data (Figure 3). The updated mmCIF is based on the archive mmCIF file. Both files follow the same PDBx/mmCIF dictionary. The updated mmCIF has two major differences from the archive mmCIF file: (i) selected data values are cleaned up to standardise the enumerations; (ii) additional data categories and items are added as required to support PDBe data out activities and external users. An example of a standardised enumeration is the values in _exptl.method which is standardised and changed from uppercase to title case. Another example of additional categories is the _chem_comp_bond which defines the expected bond order for every bond in every component in the PDB entry. Users can download these data for all the PDB entries for a protein of interest or only those containing small molecules or macromolecular complexes. Users can also interact with the download service programmatically through a set of API endpoints. Documentation of this API is available at https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/download/api/docs.

Figure 3.

Bulk data download service. The aggregated views of proteins provide a graphical user interface to a new bulk data download service which enables researchers to download all the coordinates, sequences and validation data available for a protein of interest.

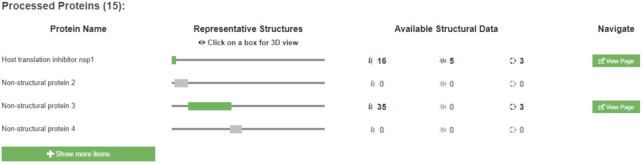

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, we developed a unique set of web pages focused on the proteins of SARS-CoV-2 in early 2020. However, it became apparent that we could improve the display of polyproteins. In particular, the aggregated views were not highlighting the mature, processed proteins, and users could not zoom in on these proteins. To address this, we have integrated information on processed proteins from UniProt and have added a new section that highlights the segments they occupy on the full-length polyprotein sequences (Figure 4). We now also enable users to view pages specifically for a particular processed/mature protein, using the PRO identifiers from UniProt. For example, https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/pdbe-kb/proteins/PRO_0000449633 is the dedicated page of the 2'-O-methyltransferase nsp16 of SARS-CoV-2, which is a processed protein from Replicase polyprotein 1ab (UniProt accession P0DTD1). These pages are available for all the processed/mature proteins with known structures, not only viral proteins.

Figure 4.

Processed proteins section. The aggregated views of proteins now include a section highlighting all the mature, processed proteins for a polyprotein. In addition, users can click on the green boxes to view the 3D structures using Mol*, and they can navigate to dedicated processed proteins pages by clicking on the ‘view page’ button.

While experimentally determining structures remains a costly and labour-intensive endeavour, there have been significant advances in the field of structural predictions. Researchers increasingly deploy Artificial Intelligence (AI) techniques to predict a protein's structure computationally from its amino-acid sequence alone (12,13,48). While the aggregated views of proteins already provided an overview of all the protein structures available in the PDB, we have expanded the scope to include predicted models from data providers such as SWISS-MODEL and AlphaFold DB (14,49) (Figure 5). Displayed in ProtVista, users can compare the structural coverage of the protein sequences and directly download predicted models.

Figure 5.

Predicted models of a protein of interest. The aggregated views of proteins now provide an overview of available predicted models from data resources such as AlphaFold DB and SWISS-MODEL.

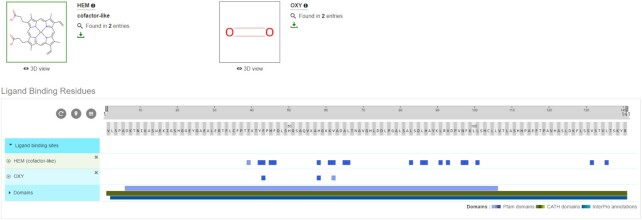

Most of the annotations provided by the PDBe-KB partner resources focus on amino acid residues and their functions or biophysical characteristics, yet PDBe-KB has information also on molecular entities such as small molecules or macromolecular interaction partners (Figure 6). For example, using a previously developed semi-automated annotation process, we can now flag small molecules as enzyme cofactors and cofactor-like molecules (50). We display this information on the sequence feature viewer, ProtVista and ligand gallery. Similarly, we have weekly processes for identifying and annotating peptides and antibody structures, which we display in the macromolecular interactions section.

Figure 6.

Ligand annotations. The aggregated views of proteins now display annotations for ligand molecules based on a cofactor data pipeline. Similarly, we annotate peptides and antibodies in the macromolecular interactions section.

Training and tutorials

Working together with the Training team of EMBL-EBI, we actively participated in training courses and continued to create training materials and tutorials that describe the new functionalities and changes to PDBe-KB web services and web pages. Recently, we created a set of tutorials that encompass programmatic access to PDBe data, data processing packages and web components that visualise the structures and annotations. These tutorials are available at https://pdbeurope.github.io/api-webinars/index.html.

DISCUSSION

PDBe-KB expands the structural, functional, and biophysical annotations of molecular structure data according to its long-term goals. By allowing integrated and FAIR access to these annotations, researchers in academia and industry can take advantage of the rich ecosystem of specialist data resources and scientific software and efficiently collate data to answer specific biological questions. Since we established PDBe-KB in 2018, the collaboration grew, integrating data from 30 partner resources across 11 countries, providing over 1.2 billion residue-level annotations. Furthermore, PDBe-KB continues to be one of the main activities of the ELIXIR 3D-BioInfo community, which brings together researchers, structural bioinformatics developers and data providers to discuss and strive for data FAIRness, benefitting the broader scientific community (51).

While we plan to further improve the aggregated views of proteins, we are also developing novel aggregated web pages for ligands, providing comprehensive structural and functional information on all the observed small molecules in the PDB archive.

Finally, we would like to extend an invitation to all the data providers and scientific software developers to join the consortium and increase user exposure through this community-driven data-sharing platform and knowledge base.

In conclusion, PDBe-KB keeps evolving and makes structural data and their structural, functional, and biophysical annotations more accessible to the scientific community, reaching over 340 000 users annually either through their usage of the rich set of programmatic access endpoints or by their visits to the PDBe-KB aggregated views pages.

DATA AVAILABILITY

PDBe-KB is available at https://pdbe-kb.org. Individual, protein-focused pages per UniProt accessions are available at https://pdbe-kb.org/proteins/P0DTD1. Documentation of the consortium members is available at https://github.com/PDBe-KB/pdbe-kb-manual/wiki. Users can download the graph database from https://pdbe-kb.org/graph-download, and users can find the aggregated API at https://pdbe-kb.org/graph-api. The PDBe-KB web component library is public at https://github.com/PDBe-KB?q=component. Finally, we make all the annotations available in JSON format from ftp://ftp.ebi.ac.uk/pub/databases/pdbe-kb.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all the members of the PDBe team for their continued support of the design and development of PDBe-KB. In addition, we thank the consortium members and the users of PDBe-KB, who continuously provide suggestions and feedback on how to improve our services. The author has applied a CC BY public copyright licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.

APPENDIX

Current PDBe-KB Consortium Members with Affiliations

Mihaly Varadi1,*, Stephen Anyango1, David Armstrong1, John Berrisford1, Preeti Choudhary1, Mandar Deshpande1, Nurul Nadzirin1, Sreenath S. Nair1, Lukas Pravda1, Ahsan Tanweer1, Bissan Al-Lazikani2, Claudia Andreini3, Geoffrey J. Barton4, David Bednar5, Karel Berka6, Tom Blundell7, Kelly P Brock8, Jose Maria Carazo9, Jiri Damborsky5, Alessia David10, Sucharita Dey11, Roland Dunbrack12, Juan Fernandez Recio13, Franca Fraternali14, Toby Gibson15, Manuela Helmer-Citterich16, David Hoksza17, Thomas Hopf8, David Jakubec17, Natarajan Kannan18, Radoslav Krivak17, Manjeet Kumar15, Emmanuel D Levy11, Nir London11, Jose Ramon Macias9, Madhusudhan M. Srivatsan19, Debora S Marks8, Lennart Martens20, 21, Stuart A McGowan4, Jake E McGreig22, Vivek Modi12, R. Gonzalo Parra23, Gerardo Pepe16, Damiano Piovesan24, Jaime Prilusky11, Valeria Putignano3, Leandro G. Radusky25, Pathmanaban Ramasamy20, 21, 26, Atilio O. Rausch27, Nathalie Reuter28, Luis A. Rodriguez13, Nathan J Rollins8, Antonio Rosato3, Paweł Rubach29, Luis Serrano25, Gulzar Singh19,Petr Skoda17, Carlos Oscar S. Sorzano9, Jan Stourac5, Joanna I Sulkowska29, Radka Svobodova30, Natalia Tichshenko20, 21, Silvio C.E. Tosatto24, Wim Vranken26, Mark N Wass22, Dandan Xue28, Daniel Zaidman11, Janet Thornton1, Michael Sternberg10, Christine Orengo31, Sameer Velankar1*

1European Molecular Biology Laboratory, European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI), Wellcome Genome Campus, Hinxton, UK

2Cancer Research UK Cancer Therapeutics Unit, Division of Cancer Therapeutics, The Institute of Cancer Research, London, UK

3University of Florence and C.I.R.M.M.P., Magnetic Resonance Center, Sesto Fiorentino, Italy

4School of Life Sciences, University of Dundee, Dundee, UK

5Masaryk University & International Centre for Clinical Research, St. Anne's University Hospital Brno, Department of Experimental Biology and RECETOX, Brno, Czech Republic

6Palacky University Olomouc, Department of Physical Chemistry, Olomouc, Czech Republic

7University of Cambridge, Department of Biochemistry, Cambridge, UK

7Computational and Systems Biology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA

9CNB-CSIC, Biocomputing Unit - Instruct Image Processing Center, Madrid, Spain

10Imperial College London, London, UK

11Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel

12Fox Chase Cancer Center, Institute for Cancer Research, Philadelphia, PA, USA

13Instituto de Ciencias de la Vid y del Vino (CSIC - Universidad de La Rioja - Gobierno de La Rioja), Oenology, Barcelona & Logroño, Spain

14Randall Centre for Cell & Molecular Biophysics, King's College London, London, UK

15European Molecular Biology Laboratory, Heidelberg, Germany

16Centre for Molecular Bioinformatics, Department of Biology, University of Rome Tor Vergata, Rome, Italy

17Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic

18University of Georgia, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology & Institute of Bioinformatics, Athens, USA

19Indian Institute of Science Education and Research, Pune, India

20Ghent University, Department of Biomolecular Medicine, Ghent, Belgium

21VIB-UGent, Center for Medical Biotechnology, Ghent, Belgium

22University of Kent, Canterbury, Kent, UK

23Barcelona Supercomputing Center, Life Sciences Department, Barcelona, Spain

24University of Padova, Deptartment of Biomedical Sciences, Padova, Italy

25Centre for Genomic Regulation, Systems Biology, Barcelona, Spain

26Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Department of Bioengineering Sciences, Brussels, Belgium

27Facultad de Ingenieria, Universidad Nacional de Entre Rios, Oro Verde, Argentina

28University of Bergen, Department of Chemistry and Computational Biology Unit, Bergen, Norway

29University of Warsaw, Centre of New Technologies, Warsaw, Poland

30Masaryk University, CEITEC - Central European Institute of Technology and National Centre for Biomolecular Research, Faculty of Science, Brno, Czech Republic

31University College London, Department of Structural and Molecular Biology, London, UK

Contributor Information

PDBe-KB consortium:

Mihaly Varadi, Stephen Anyango, David Armstrong, John Berrisford, Preeti Choudhary, Mandar Deshpande, Nurul Nadzirin, Sreenath S Nair, Lukas Pravda, Ahsan Tanweer, Bissan Al-Lazikani, Claudia Andreini, Geoffrey J Barton, David Bednar, Karel Berka, Tom Blundell, Kelly P Brock, Jose Maria Carazo, Jiri Damborsky, Alessia David, Sucharita Dey, Roland Dunbrack, Juan Fernandez Recio, Franca Fraternali, Toby Gibson, Manuela Helmer-Citterich, David Hoksza, Thomas Hopf, David Jakubec, Natarajan Kannan, Radoslav Krivak, Manjeet Kumar, Emmanuel D Levy, Nir London, Jose Ramon Macias, Madhusudhan M Srivatsan, Debora S Marks, Lennart Martens, Stuart A McGowan, Jake E McGreig, Vivek Modi, R Gonzalo Parra, Gerardo Pepe, Damiano Piovesan, Jaime Prilusky, Valeria Putignano, Leandro G Radusky, Pathmanaban Ramasamy, Atilio O Rausch, Nathalie Reuter, Luis A Rodriguez, Nathan J Rollins, Antonio Rosato, Paweł Rubach, Luis Serrano, Gulzar Singh, Petr Skoda, Carlos Oscar S Sorzano, Jan Stourac, Joanna I Sulkowska, Radka Svobodova, Natalia Tichshenko, Silvio C E Tosatto, Wim Vranken, Mark N Wass, Dandan Xue, Daniel Zaidman, Janet Thornton, Michael Sternberg, Christine Orengo, and Sameer Velankar

FUNDING

ELIXIR [IDP implementation study]; Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council via the 3D-Gateway [BB/T01959X/1]; FunPDBe [BB/P024351/1]; European Molecular Biology Laboratory-European Bioinformatics Institute who supported this work; J.D. acknowledges support from the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sport of the Czech Republic [INBIO CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_026/0008451]; R.S., K.B. and J.D. also acknowledge support from the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sport of the Czech Republic [ELIXIR-CZ LM2018131]; L.M. acknowledges support from the European Union's Horizon 2020 Programme (H2020-INFRAIA-2018-1) [823839]; Research Foundation Flanders (FWO) [G032816N, G042518N, G028821N]; W.V. acknowledges support from the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO) [G032816N, G028821N]; A.R. acknowledges support from the Fondazione Cassa Di Risparmio di Firenze [24316]; European Commission [101017567]; M.H.C. acknowledges the AIRC project to MHC [IG 23539]; J.F.-R. acknowledges support from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation [PID2019-110167RB-I00]; N.R. acknowledges support from the Norwegian Research Council (Norges Forskningsråd) [288008]; E.D.L. acknowledges support from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme [819318]; M.J.E.S. acknowledges support from the Wellcome Trust [104955/Z/14/Z, 218242/Z/19/Z]. Funding for open access charge: Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council grant [BB/T01959X/1]; Wellcome Trust [104955/Z/14/Z and 218242/Z/19/Z].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lee D., Redfern O., Orengo C.. Predicting protein function from sequence and structure. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007; 8:995–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Waman V.P., Sen N., Varadi M., Daina A., Wodak S.J., Zoete V., Velankar S., Orengo C.. The impact of structural bioinformatics tools and resources on SARS-CoV-2 research and therapeutic strategies. Brief. Bioinform. 2021; 22:742–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Knott B.C., Erickson E., Allen M.D., Gado J.E., Graham R., Kearns F.L., Pardo I., Topuzlu E., Anderson J.J., Austin H.P.et al.. Characterization and engineering of a two-enzyme system for plastics depolymerization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2020; 117:25476–25485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Batool M., Ahmad B., Choi S.. A structure-based drug discovery paradigm. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019; 20:2783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Marques S.M., Planas-Iglesias J., Damborsky J.. Web-based tools for computational enzyme design. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2021; 69:19–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. wwPDB consortium Burley S.K., Berman H.M., Bhikadiya C., Bi C., Chen L., Costanzo L.D., Christie C., Duarte J.M., Dutta S.et al.. Protein Data Bank: the single global archive for 3D macromolecular structure data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47:D520–D528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Armstrong D.R., Berrisford J.M., Conroy M.J., Gutmanas A., Anyango S., Choudhary P., Clark A.R., Dana J.M., Deshpande M., Dunlop R.et al.. PDBe: improved findability of macromolecular structure data in the PDB. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 48:D335–D343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Masrati G., Landau M., Ben-Tal N., Lupas A., Kosloff M., Kosinski J.. Integrative structural biology in the era of accurate structure prediction. J. Mol. Biol. 2021; 433:167127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Consortium The UniProt Bateman A., Martin M.-J., Orchard S., Magrane M., Agivetova R., Ahmad S., Alpi E., Bowler-Barnett E.H., Britto R.et al.. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021; 49:D480–D489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Velankar S., Burley S.K., Kurisu G., Hoch J.C., Markley J.L.. Owens R.J. The Protein Data Bank Archive. Structural Proteomics, Methods in Molecular Biology. 2021; 2305:New York, NY: Springer US; 3–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dana J.M., Gutmanas A., Tyagi N., Qi G., O’Donovan C., Martin M., Velankar S.. SIFTS: updated structure integration with function, taxonomy and sequences resource allows 40-fold increase in coverage of structure-based annotations for proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47:D482–D489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Baek M., DiMaio F., Anishchenko I., Dauparas J., Ovchinnikov S., Lee G.R., Wang J., Cong Q., Kinch L.N., Schaeffer R.D.et al.. Accurate prediction of protein structures and interactions using a three-track neural network. Science. 2021; 373:871–876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jumper J., Evans R., Pritzel A., Green T., Figurnov M., Ronneberger O., Tunyasuvunakool K., Bates R., Žídek A., Potapenko A.et al.. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 2021; 596:583–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tunyasuvunakool K., Adler J., Wu Z., Green T., Zielinski M., Žídek A., Bridgland A., Cowie A., Meyer C., Laydon A.et al.. Highly accurate protein structure prediction for the human proteome. Nature. 2021; 596:590–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. consortium PDBe-KB, Varadi M., Berrisford J., Deshpande M., Nair S.S., Gutmanas A., Armstrong D., Pravda L., Al-Lazikani B., Anyango S.et al.. PDBe-KB: a community-driven resource for structural and functional annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020; 48:D344–D353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mitsopoulos C., Di Micco P., Fernandez E.V., Dolciami D., Holt E., Mica I.L., Coker E.A., Tym J.E., Campbell J., Che K.H.et al.. 2021) canSAR: update to the cancer translational research and drug discovery knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 49:D1074–D1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Levy E.D., Teichmann S.A.. Structural, evolutionary, and assembly principles of protein oligomerization. Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science. 2013; 117:Elsevier; 25–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pravda L., Sehnal D., Svobodová Vařeková R., Navrátilová V., Toušek D., Berka K., Otyepka M., Koča J.. ChannelsDB: database of biomacromolecular tunnels and pores. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018; 46:D399–D405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Madeira F., Tinti M., Murugesan G., Berrett E., Stafford M., Toth R., Cole C., MacKintosh C., Barton G.J.. 14-3-3-Pred: improved methods to predict 14-3-3-binding phosphopeptides. Bioinformatics. 2015; 31:2276–2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Levy E.D., Pereira-Leal J.B., Chothia C., Teichmann S.A.. 3D complex: a structural classification of protein complexes. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2006; 2:e155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wass M.N., Kelley L.A., Sternberg M.J.E.. 3DLigandSite: predicting ligand-binding sites using similar structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010; 38:W469–W473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Parca L., Ariano B., Cabibbo A., Paoletti M., Tamburrini A., Palmeri A., Ausiello G., Helmer-Citterich M. Kinome-wide identification of phosphorylation networks in eukaryotic proteomes. Bioinformatics. 2019; 35:372–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jubb H.C., Higueruelo A.P., Ochoa-Montaño B., Pitt W.R., Ascher D.B., Blundell T.L. Arpeggio: a web server for calculating and visualising interatomic interactions in protein structures. J. Mol. Biol. 2017; 429:365–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sillitoe I., Dawson N., Lewis T.E., Das S., Lees J.G., Ashford P., Tolulope A., Scholes H.M., Senatorov I., Bujan A.et al.. CATH: expanding the horizons of structure-based functional annotations for genome sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47:D280–D284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tan K.P., Nguyen T.B., Patel S., Varadarajan R., Madhusudhan M.S. Depth: a web server to compute depth, cavity sizes, detect potential small-molecule ligand-binding cavities and predict the pKa of ionizable residues in proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013; 41:W314–W321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zaidman D., Gehrtz P., Filep M., Fearon D., Gabizon R., Douangamath A., Prilusky J., Duberstein S., Cohen G., Owen C.D.et al.. An automatic pipeline for the design of irreversible derivatives identifies a potent SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitor. Cell Chem. Biol. 2021; 10.1016/j.chembiol.2021.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cilia E., Pancsa R., Tompa P., Lenaerts T., Vranken W.F. The DynaMine webserver: predicting protein dynamics from sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014; 42:W264–W270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kumar M., Gouw M., Michael S., Sámano-Sánchez H., Pancsa R., Glavina J., Diakogianni A., Valverde J.A., Bukirova D., Čalyševa J.et al.. ELM—the eukaryotic linear motif resource in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 48:D296–D306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Segura J., Sanchez-Garcia R., Sorzano C.O.S., Carazo J.M. 3DBIONOTES v3.0: crossing molecular and structural biology data with genomic variations. Bioinformatics. 2019; 35:3512–3513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hopf T.A., Green A.G., Schubert B., Mersmann S., Schärfe C.P.I., Ingraham J.B., Toth-Petroczy A., Brock K., Riesselman A.J., Palmedo P.et al.. The evcouplings Python framework for coevolutionary sequence analysis. Bioinformatics. 2019; 35:1582–1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stourac J., Dubrava J., Musil M., Horackova J., Damborsky J., Mazurenko S., Bednar D. FireProtDB: database of manually curated protein stability data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021; 49:D319–D324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Delgado J., Radusky L.G., Cianferoni D., Serrano L. FoldX 5.0: working with RNA, small molecules and a new graphical interface. Bioinformatics. 2019; 35:4168–4169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rausch A.O., Freiberger M.I., Leonetti C.O., Luna D.M., Radusky L.G., Wolynes P.G., Ferreiro D.U., Parra R.G. FrustratometeR: an R-package to compute local frustration in protein structures, point mutants and MD simulations. Bioinformatics. 2021; 10.1093/bioinformatics/btab176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Modi V., Dunbrack R.L. Defining a new nomenclature for the structures of active and inactive kinases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2019; 116:6818–6827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dabrowski-Tumanski P., Rubach P., Goundaroulis D., Dorier J., Sułkowski P., Millett K.C., Rawdon E.J., Stasiak A., Sulkowska J.I. KnotProt 2.0: a database of proteins with knots and other entangled structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47:D367–D375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ribeiro A.J.M., Holliday G.L., Furnham N., Tyzack J.D., Ferris K., Thornton J.M. Mechanism and Catalytic Site Atlas (M-CSA): a database of enzyme reaction mechanisms and active sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018; 46:D618–D623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Putignano V., Rosato A., Banci L., Andreini C. MetalPDB in 2018: a database of metal sites in biological macromolecular structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018; 46:D459–D464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Khanna T., Hanna G., Sternberg M.J.E., David A. Missense3D-DB web catalogue: an atom-based analysis and repository of 4M human protein-coding genetic variants. Hum. Genet. 2021; 140:805–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Piovesan D., Necci M., Escobedo N., Monzon A.M., Hatos A., Mičetić I., Quaglia F., Paladin L., Ramasamy P., Dosztányi Z.et al.. MobiDB: intrinsically disordered proteins in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021; 49:D361–D367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Krivák R., Hoksza D. P2Rank: machine learning based tool for rapid and accurate prediction of ligand binding sites from protein structure. J. Cheminformatics. 2018; 10:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kleinjung J., Fraternali F. POPSCOMP: an automated interaction analysis of biomolecular complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005; 33:W342–W346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. McSkimming D.I., Dastgheib S., Talevich E., Narayanan A., Katiyar S., Taylor S.S., Kochut K., Kannan N. ProKinO: a unified resource for mining the cancer kinome. Hum. Mutat. 2015; 36:175–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ramasamy P., Turan D., Tichshenko N., Hulstaert N., Vandermarliere E., Vranken W., Martens L. Scop3P: a comprehensive resource of human phosphosites within their full context. J. Proteome Res. 2020; 19:3478–3486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jankauskaitė J., Jiménez-García B., Dapkūnas J., Fernández-Recio J., Moal I.H. SKEMPI 2.0: an updated benchmark of changes in protein–protein binding energy, kinetics and thermodynamics upon mutation. Bioinformatics. 2019; 35:462–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tiwari S.P., Fuglebakk E., Hollup S.M., Skjærven L., Cragnolini T., Grindhaug S.H., Tekle K.M., Reuter N. WEBnm@ v2.0: Web server and services for comparing protein flexibility. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014; 15:427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nair S., Váradi M., Nadzirin N., Pravda L., Anyango S., Mir S., Berrisford J., Armstrong D., Gutmanas A., Velankar S. PDBe aggregated API: programmatic access to an integrative knowledge graph of molecular structure data. Bioinformatics. 2021; 10.1093/bioinformatics/btab424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sehnal D., Bittrich S., Deshpande M., Svobodová R., Berka K., Bazgier V., Velankar S., Burley S.K., Koča J., Rose A.S. Mol* Viewer: modern web app for 3D visualization and analysis of large biomolecular structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021; 49:W431–W437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ramanathan A., Ma H., Parvatikar A., Chennubhotla S.C. Artificial intelligence techniques for integrative structural biology of intrinsically disordered proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2021; 66:216–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Waterhouse A., Bertoni M., Bienert S., Studer G., Tauriello G., Gumienny R., Heer F.T., de Beer T.A.P., Rempfer C., Bordoli L.et al.. SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018; 46:W296–W303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mukhopadhyay A., Borkakoti N., Pravda L., Tyzack J.D., Thornton J.M., Velankar S. Finding enzyme cofactors in Protein Data Bank. Bioinformatics. 2019; 35:3510–3511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Orengo C., Velankar S., Wodak S., Zoete V., Bonvin A.M.J.J., Elofsson A., Feenstra K.A., Gerloff D.L., Hamelryck T., Hancock J.M.et al.. A community proposal to integrate structural bioinformatics activities in ELIXIR (3D-Bioinfo Community). F1000Research. 2020; 9:278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

PDBe-KB is available at https://pdbe-kb.org. Individual, protein-focused pages per UniProt accessions are available at https://pdbe-kb.org/proteins/P0DTD1. Documentation of the consortium members is available at https://github.com/PDBe-KB/pdbe-kb-manual/wiki. Users can download the graph database from https://pdbe-kb.org/graph-download, and users can find the aggregated API at https://pdbe-kb.org/graph-api. The PDBe-KB web component library is public at https://github.com/PDBe-KB?q=component. Finally, we make all the annotations available in JSON format from ftp://ftp.ebi.ac.uk/pub/databases/pdbe-kb.