Abstract

The protein kinase Akt is activated by growth factors and promotes cell survival and cell cycle progression. Here, we demonstrate that Akt phosphorylates the cell cycle inhibitory protein p21Cip1 at Thr 145 in vitro and in intact cells as shown by in vitro kinase assays, site-directed mutagenesis, and phospho-peptide analysis. Akt-dependent phosphorylation of p21Cip1 at Thr 145 prevents the complex formation of p21Cip1 with PCNA, which inhibits DNA replication. In addition, phosphorylation of p21Cip1 at Thr 145 decreases the binding of the cyclin-dependent kinases Cdk2 and Cdk4 to p21Cip1 and attenuates the Cdk2 inhibitory activity of p21Cip1. Immunohistochemistry and biochemical fractionation reveal that the decrease of PCNA binding and regulation of Cdk activity by p21Cip1 phosphorylation is not caused by altered intracellular localization of p21Cip1. As a functional consequence, phospho-mimetic mutagenesis of Thr 145 reverses the cell cycle-inhibitory properties of p21Cip1, whereas the nonphosphorylatable p21Cip1 T145A construct arrests cells in G0 phase. These data suggest that the modulation of p21Cip1 cell cycle functions by Akt-mediated phosphorylation regulates endothelial cell proliferation in response to stimuli that activate Akt.

The serine/threonine protein kinase Akt signals in response to insulin and a variety of growth factors. These include platelet-derived growth factor, basic fibroblast growth factor (4, 20), and, in endothelial cells, the angiogenic growth factors vascular endothelial growth factor and angiopoietin 1 (16, 17, 22, 27). Phospho-inositide 3-kinase (PI3K) mediates Akt activation following receptor stimulation (4, 20, 32). Thus, binding of PI3K-derived 3′-phosphorylated phosphoinositides to the pleckstrin homology domain of Akt renders the activation sites Thr 308 and Ser 473 accessible for phosphorylation (for a review, see reference 12). Akt targets a number of established substrates for phosphorylation. These proteins mostly conform to the consensus motif RXRXXS/T (the phospho-acceptor amino acids are underlined) required for efficient phosphorylation by Akt kinase (1). Among the phosphorylation substrates of Akt are glycogen synthase kinase 3 (11), as well as Bad (13, 14), caspase 9 (5), IκB kinase (37), the endothelial NO synthase (16, 22), and Forkhead transcription factors (28). Akt plays a critical role in the regulation of cell survival (12), consistent with the known apoptosis-regulating functions of the identified target proteins. Akt also regulates cell proliferation (15, 24, 33, 34); however, the underlying mechanism(s) for Akt-dependent cell cycle control is less well defined.

p21Cip1 is an inhibitor of cell cycle progression leading to G1 phase arrest. p21Cip1 inhibits cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk) activity with a certain selectivity for G1/S phase Cdk-cyclin complexes (26). However, by promoting cyclin D-Cdk assembly, p21Cip1 can also function as an activator of D-type Cdks (Cdk4 and Cdk6) (for a review, see reference 43). Besides Cdk regulation, p21Cip1 directly binds to PCNA (19). It thus interferes with the requirement of PCNA for DNA polymerase δ function and inhibits DNA replication (45). The dual effect of p21Cip1 on cell cycle regulatory proteins is mediated via distinct interaction sites for cyclin-Cdk complexes (7) and PCNA (46) that partially overlap. Besides the well-established transcriptional regulation of p21Cip1 (18), recent studies provide evidence that p21Cip1 function is additionally regulated on a posttranscriptional level (8, 21, 38). PKC-dependent phosphorylation of p21Cip1 at Ser 146 was shown to modulate PCNA binding by p21Cip1 in insect cells (40). However, the functional implications of p21Cip1 phosphorylation for its interaction with cell cycle regulatory elements and for the proliferative response in mammalian cells have not been elucidated.

We have investigated the interaction between Akt and p21Cip1 in human endothelial cells. Our results demonstrate that Akt phosphorylates p21Cip1 at Thr 145, which abrogates PCNA binding to p21Cip1, and attenuates the complex formation of p21Cip1 with Cdk2 and Cdk4, which results in endothelial cell proliferation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture, immunoprecipitation, and immunoblotting.

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were purchased from Cell Systems/Clonetics, Solingen, Germany, and were cultured as previously described (16). HUVEC homogenates were obtained, separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Membranes were incubated with antibodies to c-myc, DNA topoisomerase I, Cdk2, and Cdk4 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); actin (Chemicon, Temecula, Calif.); phospho-Akt substrate and Akt (Cell Signaling, Beverly, Mass.); cyclins D1, D2, and D3 and p21 (BD PharMingen); and PCNA (Transduction Laboratories). Immunoprecipitation was performed using either protein A/G-agarose beads (Santa Cruz) or agarose-conjugated antibodies (Aminolink; Pierce). Bound antibodies were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham).

Plasmids and transfection.

A plasmid encoding the human p21Cip1 was cloned by PCR into the pcDNA3.1-Myc-His vector (Invitrogen). The putative Akt site (Thr 145 or Ser 146) was changed by site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene). The plasmids encoding the bovine Akt and the truncated dominant negative Akt construct were kindly donated by J. Downward and were subcloned into the pcDNA3.1 vector as previously described (16). Clones with verified sequences were used to transfect HUVEC (3.5 × 105cells/6-cm well; 3 μg of plasmid DNA and 25 μl of Superfect) or COS-7 cells (3.8 × 105 cells/6-cm plate; 8 μg of plasmid DNA and 30 μl of Superfect) as previously described (16). For combined oligonucleotide and plasmid transfection, HUVEC were incubated with 1.5 μg of sense p21Cip1 (5′-GAGCCGCGACTGTGATGCGCT-3′) or antisense p21Cip1 (5′-AGCGCATCACAGTCGCGGCTC-3′) oligonucleotide in the presence of 2.5 μg of vector (pcDNA3.1.) or active Akt (pcDNA3.1.-Akt T308D/S473D) with Lipofectamine (Life Technologies).

p21Cip1 phosphorylation, phospho-site mapping, and kinase assay.

After serum starvation for 90 min in phosphate-free medium, COS cells were loaded with [32P]H3PO4 (250 μCi) in the presence of 10% serum for 3 h. Endogenous p21 was immunoprecipitated with agarose-coupled (Aminolink; Pierce) anti-p21 antibody (PharMingen). Following elution, p21 was digested with tosyl phenylalanine chloromethyl ketone (TPCK)-treated trypsin-agarose (Sigma). The supernatant was loaded onto a Source 5RPC column (Amersham), and peptides were eluted with acetonitrile with an Äkta explorer high-performance liquid chromatography system (Amersham). Radioactivity of the fractions collected was determined using an EasiCount system (Scotlab).

For detection of Akt phosphorylation of p21Cip1 in vitro, COS cells were transfected with myc-tagged p21Cip1 constructs, and whole-cell lysates (1 mg/sample) were immunoprecipitated with anti-myc antibodies. Active Akt kinase was obtained by immunoprecipitation of overexpressed myc-tagged constitutively active Akt (T308D/S473D). p70 S6 kinase was also obtained by overexpression and immunopurification, whereas the recombinant catalytic subunits of protein kinase A (PKA) and serum-glucocorticoid-stimulated kinase (SGK) were delivered from Calbiochem and Upstate, respectively. p21Cip1 immunoprecipitates (substrates) and the respective kinases were incubated at 30°C in 30 μl of a kinase reaction mixture containing 25 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 5 mM β-glycerophosphate, 0.1 mM Na3VO4, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM MnCl2, 50 μM ATP, and 5 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP for 30 min. The reaction was terminated by the addition of SDS sample buffer, and samples were subjected to SDS–12% PAGE and analyzed by phosphorimaging. For assessment of Cdk2 or Cdk4 kinase activity, endogenous Cdk2 or Cdk4 was immunoprecipitated, and kinase activity was detected after incubation of the immunoprecipitates with histone H1 or retinoblastoma protein (pRb) and the kinase assay reaction mixture as described above.

Immunostaining.

Endothelial cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 10 min before incubation of the cells with anti-myc antibody (1:70 in PBS–5% fetal calf serum [FCS]) and anti-mouse fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-linked secondary antibody (Dako) (1:20 in PBS–5% FCS) followed by nuclear counterstaining with DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino2-phenylindole).

Cell cycle analysis.

Thirty-six hours after transfection, HUVEC were washed with PBS, trypsinized, and fixed in 70% ice-cold ethanol, followed by incubation with RNase (100 μg/ml) and propidium iodide (4 μg/ml) in PBS. Cell cycle phases were detected with a flow cytometer (FACSCalibur; Perkin-Elmer) with CELLQuest and Modfit LT software. For detection of proliferation, cells were incubated with 10 μM bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) for 1 h, and incorporated BrdU was detected by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay according the instructions of the manufacturer (Roche). To analyze the effect of transfected protein on endothelial cell proliferation, HUVEC were cotransfected with green fluorescent protein (GFP) (1 μg) and the respective pcDNA3.1. constructs (2 μg). GFP-positive cells were isolated by a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS), air dried on cover slides, and fixed in 100% methanol for 10 min at 4°C, which destroys the fluorescence of the GFP. Immunostaining was performed using anti-Ki67 antibodies (1:50 in PBS–5% FCS; Dianova, Hamburg, Germany) and FITC-linked secondary antibodies. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Alternatively, HUVEC were incubated with BrdU for 1 h before FACS sorting and labeled by FITC-labeled anti-BrdU antibodies.

Statistics.

Data are expressed as the mean ± the standard error of the mean (SEM) from at least three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed with analysis of variance, followed by a modified least significant difference test (SPSS Software).

RESULTS

Akt phosphorylates p21Cip1.

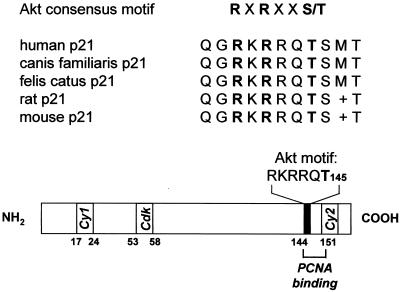

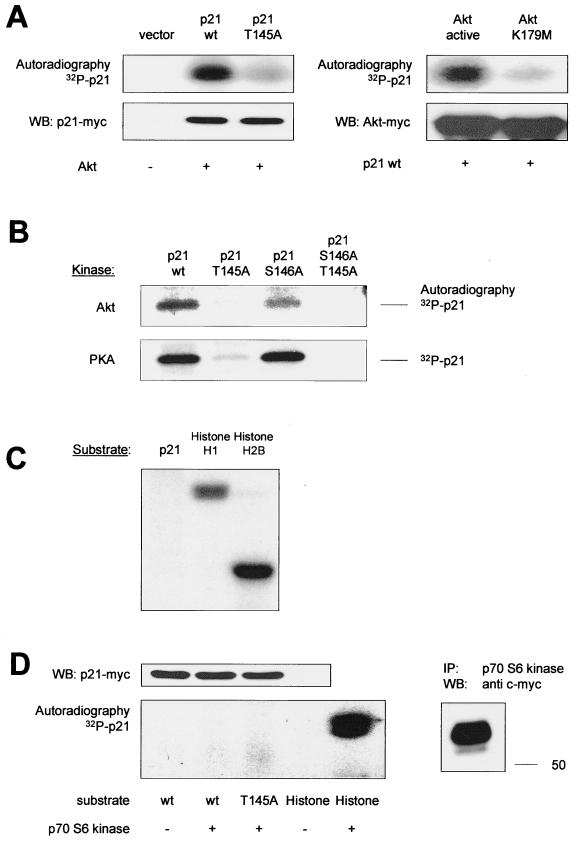

The C-terminal amino acid sequence of human p21Cip1 from arginine 140 to threonine 145 matches the reported consensus motif for Akt-mediated phosphorylation (1). The sequence at this site of p21Cip1 is highly conserved between various species (Fig. 1). We therefore examined whether p21Cip1 is a substrate for Akt kinase activity in vitro. Transfected Akt was immunoprecipitated, and a kinase assay with isolated p21Cip1 as a substrate was performed. Active Akt kinase stimulates the phosphorylation of p21Cip1 in vitro (Fig. 2A). To identify the phosphate acceptor amino acid, the putative Akt site Thr 145 of p21Cip1 was replaced by alanine (p21 T145A). Inactivation of Thr 145 markedly reduced the Akt-dependent phosphorylation of p21Cip1 (Fig. 2A). This suggests that Thr 145 serves as the Akt phosphorylation acceptor amino acid. Control experiments confirmed that kinase inactive Akt (K179 M or T308A/S473A) did not induce p21Cip1 phosphorylation (Fig. 2A and data not shown). Previously, PKA has been shown to specifically phosphorylate p21Cip1 at Thr 145 (40). In vitro kinase assay analysis confirms that Akt and PKA both phosphorylate p21Cip1 at the same site (Thr 145) (Fig. 2B). In contrast, other PI3K-dependent protein kinases, such as SGK (35) and p70 S6 kinase (10) did not display p21Cip1 phosphorylation activity in vitro (Fig. 2C and D).

FIG. 1.

Akt phosphorylation site of p21Cip1: sequence homology and localization. Cy1 (amino acids [aa] 17 to 24) and Cy2 (aa 152 to 158), cyclin-binding motifs (6, 7); Cdk, Cdk-binding motif (7); PCNA binding, PCNA binding site (aa 144 to 151) (23, 46).

FIG. 2.

In vitro phosphorylation of p21Cip1. (A) myc-tagged p21Cip1 (p21 wt or the nonphosphorylatable T145A construct), active Akt (T308D/S473D), or inactive Akt (K179 M) was overexpressed in COS-7 cells and immunoprecipitated with an anti-myc antibody. The immunoprecipitates were combined, and kinase activity towards p21Cip1 was assayed as described in Materials and Methods. Phosphorylated proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE. The lower panels demonstrate the equal expression of the proteins by Western blot analysis (WB) with anti-myc antibodies. (B) Comparison of Akt and PKA in vitro kinase activities towards p21 wt and Thr 145 constructs. (C) Lack of an effect of SGK in phosphorylating p21Cip1 in vitro. As a positive control, histone phosphorylation by SGK is shown. (D) Lack of p21Cip1 in vitro phosphorylation activity by p70 S6 kinase. Histone phosphorylation is shown as a positive control. Immunoblot analysis demonstrates p21Cip1 expression (top) and p70 S6 kinase immunopurification (IP) (right). Representative autoradiographs out of at least three different experiments are shown (A through D).

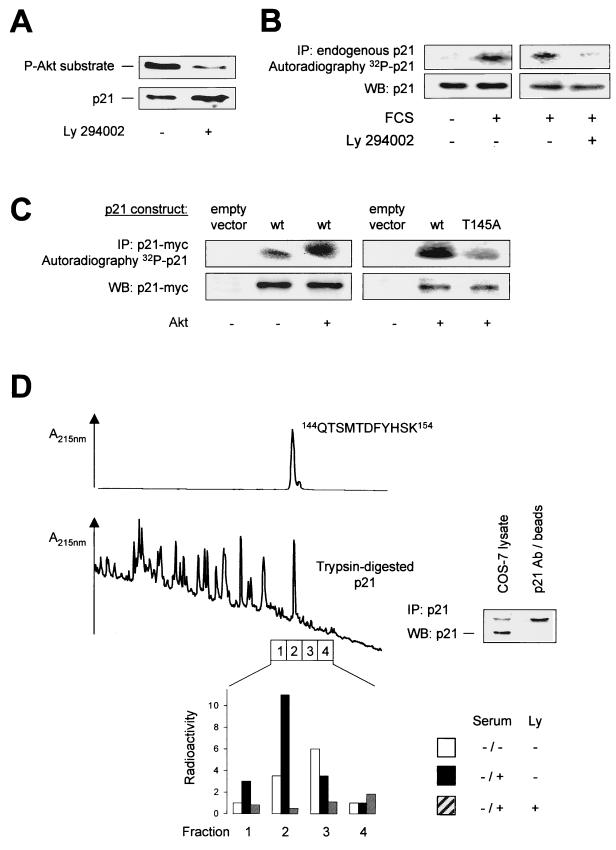

To characterize p21Cip1 phosphorylation in vivo, we employed an antibody that binds to peptide sequences containing phosphorylated Thr/Ser residues preceded by Lys/Arg at positions −5 and −3, thus specifically recognizing phosphorylation at the Akt phosphorylation consensus motif. By immunoblot analysis of endothelial cell lysates using this antibody, we were able to detect a distinct band at 21 kDa that corresponded to endogenous p21 identified by reprobing of the membrane (Fig. 3A). Treatment of the cells with Ly294002 markedly reduced this band, suggesting that a PI3K-sensitive mechanism phosphorylates p21Cip1 in endothelial cells (Fig. 3A). Similar results were obtained using a phospho-specific p21Cip1 antibody raised against a peptide containing the phosphorylated Akt consensus region of p21Cip1, NH2-CDSQGRKRRQpTSMT-CONH2 (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

In vivo phosphorylation of p21Cip1. (A) Detection of phosphorylated p21Cip1 by immunoblot analysis of HUVEC extracts using a phospho-specific antibody against the Akt phosphorylation consensus motif. Right lane, effect of Ly294002 (10 μM) for 1 h before lysis. The lower panel shows total endogenous p21Cip1 for comparison. (B) In vivo phosphorylation of p21Cip1 by a serum-induced, PI3K-sensitive mechanism. HUVEC were labeled with 32P and starved for 1 h in FCS-free medium before the addition of 10% phosphate-free FCS and Ly294002 (10 μM) for 30 min as indicated. Endogenous p21Cip1 was immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-p21Cip1 antibodies. (C). In vivo phosphorylation of p21Cip1 by Akt. COS-7 cells overexpressing myc-tagged p21Cip1 constructs and vector (pcDNA3.1) or Akt constructs were labeled with 32P for 3 h, and p21Cip1 was immunoprecipitated with anti-myc antibodies. In panels B and C, representative autoradiographs are shown: lower panels, expression of p21Cip1 as a loading control. (D) Phospho-peptide analysis. (Top) Elution of the synthetic peptide QTSMTDFYHSK (where T is the phospho-acceptor amino acid) corresponding to amino acids 144 to 154 of p21 from the reverse phase column. This peptide contains the putative Akt phosphorylation site (145Thr) in p21 and would result from tryptic digestion of p21. (Middle) Endogenous p21 was immunoprecipitated from COS cells, and tryptic p21 peptides were separated by reverse-phase chromatography. Note the peak corresponding to the peptide QTSMTDFYHSK. (Bottom) Following serum starvation, COS cells were serum treated in the presence of 32P with or without Ly294002 (10 μM). Tryptic p21 peptides were seperated as above, and fractions surrounding peptide QTSMTDFYHSK were collected for determination of radioactivity. A representative result is shown. WB, Western blotting.

To confirm that phosphorylation of p21Cip1 at Thr 145 occurs in vivo, we labeled intact cells with [32P]orthophosphate. Stimulation with serum induced the incorporation of 32P into endogenous p21Cip1 (Fig. 3B). Inhibition of the PI3K pathway with Ly294002 reduced radioactive labeling by about 90% (Fig. 3B). The phosphorylation of p21Cip1 was mainly due to incorporation of 32P into Thr 145, since inactivation of Thr 145 markedly reduced serum-dependent p21Cip1 phosphorylation (85% inhibition; data not shown). Transfection of Akt stimulated the incorporation of 32P in cells overexpressing the p21Cip1 wild type (p21 wt), whereas radioactive labeling of the T145A construct in response to Akt overexpression was markedly lower (Fig. 3C). The basal phosphorylation of p21Cip1 in vivo is most likely due to phosphorylation of p21Cip1 by another kinase(s).

To further establish Thr 145 as the phospho-acceptor amino acid by PI3K-dependent phosphorylation of p21Cip1 in intact cells, we performed a phospho-site-mapping analysis. Following in vivo radioactive labeling, p21Cip1 was immunoprecipitated from cell lysates as described in Materials and Methods (Fig. 3D, insert). Immunopurified p21Cip1 was then subjected to trypsin digestion, and the resulting peptides were separated by reverse-phase chromatography. Fraction 2 (Fig. 3D) corresponded to the eluate of a synthetic peptide according to the predicted peptide resulting from trypsin digestion containing Thr 145 (144QTSMTDFYHSK154) (Fig. 3D). In contrast to the adjacent fractions, fraction 2 contained radioactivity when cells were stimulated with serum. Coincubation with the PI3K inhibitor Ly294002 abolished incorporation of radioactivity in this specific peptide (Fig. 3D). These results indicate that serum induces phosphorylation of the peptide 144QTSMTDFYHSK154, which contains the Akt site Thr 145, in a PI3K-dependent manner. Taken together, the present data demonstrate that Akt interacts with and phosphorylates p21Cip1 in vitro and in vivo at Thr 145.

Thr 145 phosphorylation inhibits PCNA binding to p21Cip1.

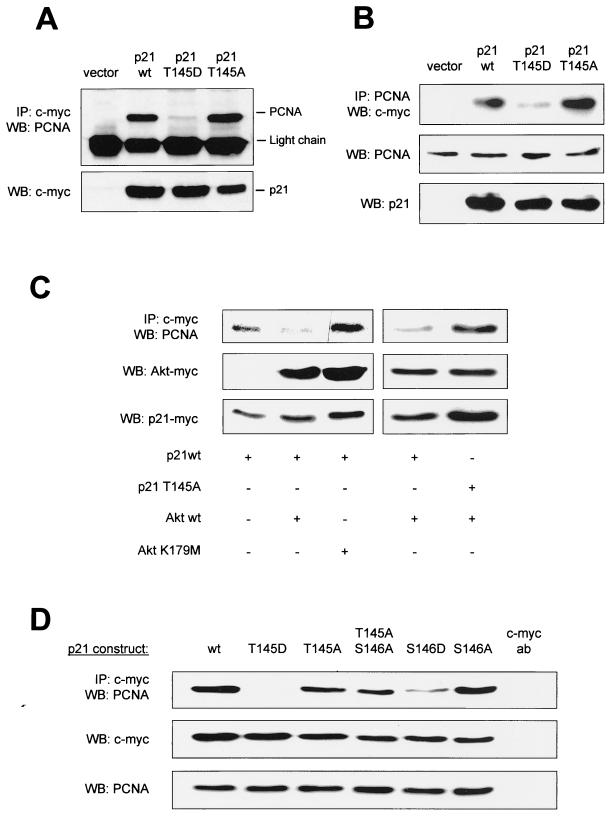

The PCNA binding site of p21Cip1 overlaps with the Akt phosphorylation site (Fig. 1) (6, 25, 46). Therefore, we analyzed whether p21Cip1 phosphorylation at Thr 145 affects PCNA binding. p21 wt binds to PCNA as shown by coimmunoprecipitation studies with anti-myc antibodies for immunoprecipitation of myc-tagged p21 wt followed by Western blotting against endogenous PCNA (Fig. 4A), as well as by immunoblot analysis of p21 bound to immunoprecipitates of endogenous PCNA (Fig. 4B). Cotransfection of Akt substantially reduced PCNA binding to p21 wt, whereas overexpression of kinase-inactive Akt (Akt K179 M) did not interfere with the p21Cip1-PCNA interaction (Fig. 4C), clearly demonstrating that Akt regulates the complex formation between PCNA and p21Cip1.

FIG. 4.

Regulation of PCNA binding by Akt-dependent phosphorylation of p21Cip1. (A) Coimmunoprecipitation of p21Cip1-PCNA complexes. myc-tagged p21Cip1 constructs were expressed in COS-7 cells and immunoprecipitated (IP) with an anti-myc antibody followed by Western blotting (WB) against PCNA (n = 4 different experiments). (B) Endogenous PCNA was immunoprecipitated from COS-7 cells overexpressing the various myc-tagged p21Cip1 constructs followed by Western blot analysis using an anti-myc antibody (n = 3). (C) COS-7 cells were cotransfected with myc-tagged p21Cip1 and vector, active Akt (T308D/S473D), or kinase-inactive Akt (K179 M). Then, PCNA was detected by immunoblot analysis of anti-myc immunoprecipitates (n = 3). (D) COS-7 cells were transfected with p21Cip1 constructs mutated at Thr 145 and/or Ser 146. Again, endogenous PCNA was detected from anti-myc immunoprecipitates. Right lane, anti-myc antibody without cell lysate. Expression of p21Cip1 constructs and endogenous PCNA is shown in the lower panels (A through D). Similar results were obtained using HUVEC.

To characterize the role of Thr 145 phosphorylation for p21Cip1-PCNA complex formation, we used a phospho-mimetic p21Cip1 construct, where Thr 145 was replaced by aspartic acid (p21 T145D). Simulated p21Cip1 phosphorylation at Thr 145 completely prevented p21Cip1-PCNA binding, whereas the nonphosphorylatable p21 T145A construct displayed no change in PCNA binding compared to p21 wt (Fig. 4A and B). In contrast to p21 wt, active Akt did not affect PCNA binding to the phospho-acceptor-deficient T145A construct (Fig. 4C). Reversible phosphorylation of an amino acid residue in the vicinity close to Thr 145, Ser 146, has previously been shown to regulate PCNA binding to p21Cip1 in Sf9 insect cells (40). Therefore, we designed additional p21Cip1 constructs carrying a mutation to an unphosphorylatable (S146A) or to a phosphomimetic amino acid (S146D) at position 146. Coimmunoprecipitation experiments confirmed that in mammalian cells stimulation of p21Cip1 phosphorylation at serine 146 indeed decreases PCNA binding (Fig. 4D). However, phosphorylation of p21Cip1 at the Akt phosphorylation site Thr 145 exerts a more pronounced inhibition of complex formation with PCNA than Ser 146 phosphorylation (Fig. 4D). Taken together, Akt regulates p21Cip1-PCNA binding via specific phosphorylation of the Thr 145 residue.

Effect of Akt-dependent p21Cip1 phosphorylation on Cdks.

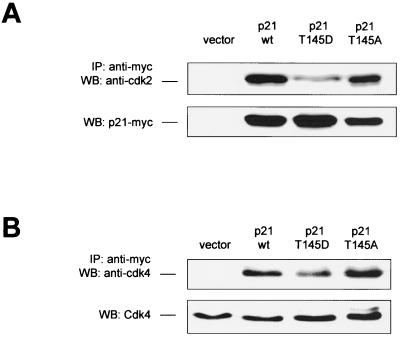

Besides its interaction with PCNA, p21Cip1 forms complexes with cyclins and Cdks and can inhibit Cdk activity (26). In close proximity to the Akt-dependent phosphorylation site Thr 145, p21Cip1 contains a cyclin-binding motif (Cy2), which has been reported to play an important role in the Cdk inhibitory function of p21Cip1 (7). To explore the potential regulation of p21Cip1-Cdk complex formation by Akt-mediated p21Cip1 phosphorylation, we characterized Cdk2 and Cdk4 binding to various p21Cip1 constructs by coimmunoprecipitation studies. Simulation of p21Cip1 phosphorylation at Thr 145 (T145D) reduced Cdk2 binding in endothelial cells by 59% ± 15% (Fig. 5A) and affected complex formation with Cdk4 to a minor degree (Fig. 5B), whereas both p21 wt and the T145A construct complexed with Cdk2 and Cdk4 to similar extents (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Effect of p21Cip1 phosphorylation at Thr 145 on Cdk binding. COS-7 cells were transfected with p21Cip1 constructs, and endogenous Cdk2 (A) or Cdk4 (B) was detected from anti-myc immunoprecipitates (IP) by immunoblot analysis (n = 4 experiments). The expression of the constructs is shown in the lower panel.

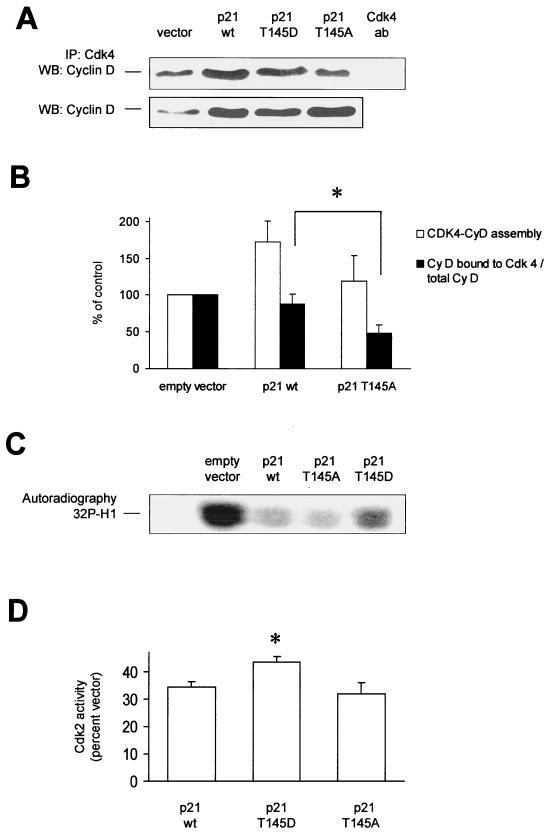

In addition to direct binding of Cdks by complex formation, p21Cip1 affects Cdk function by promoting the assembly of D-type cyclins with Cdk4 (30), thereby activating these Cdks (8). We therefore analyzed the effect of Thr 145 phosphorylation of p21Cip1 on the regulation of cyclin D-Cdk4 assembly. Interestingly, overexpression of p21 wt leads to an increase in cyclin D protein levels (Fig. 6A). Accordingly, in cells overexpressing p21Cip1 the amount of cyclin D complexed with Cdk4 was increased, as assessed by immunoblot analysis of Cdk4-immunoprecipitates with an antibody against cyclin D (Fig. 6A and B). The Akt–phospho-mimetic p21Cip1 T145D construct induced no further increase in cyclin D-Cdk4 assembly. However, prevention of p21Cip1 phosphorylation by Akt in cells transfected with the p21Cip1 T145A construct resulted in a significant decrease in cyclin D-Cdk complex formation (Fig. 6A and B). Overexpression of the p21Cip1 T145D and T145A constructs had no effect on cyclin E-Cdk2 assembly (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Regulation of Cdk function by p21Cip1 phosphorylation at Thr 145. (A) Effect of p21Cip1 phosphorylation at Thr 145 on cyclin D-Cdk4 assembly. Endogenous cyclin D was detected in Cdk4 immunoprecipitates (IP) from HUVEC overexpressing the various Thr 145 constructs of p21Cip1 (n = 4). The lower panel shows endogenous cyclin D expression in HUVEC transfected with vector or p21Cip1 constructs. (B) Densitometric analysis of cyclin D expression and binding to Cdk4 in p21Cip1-transfected HUVEC. Data are mean ± SEM, n = 4, *P < 0.05. (C and D) Cdk2 kinase activity. Immunoprecipitated Cdk2 from HUVEC overexpressing p21Cip1 constructs was incubated with histone H1 as an in vitro substrate. A representative autoradiograph is shown in panel C. The quantitative analysis is shown in panel D (n = 4, *, P < 0.05 versus the wild type). WB, Western blotting.

We then examined whether the observed modulation of Cdk2 binding and cyclin D-Cdk4 complex formation by Akt-dependent phosphorylation of p21Cip1 does indeed change Cdk activity. Overexpression of p21Cip1 significantly reduced the kinase activity of Cdk2 (35% ± 6% of vector-transfected cells; P < 0.001). However, cells transfected with the Akt–phospho-mimetic p21Cip1 T145D construct displayed reduced inhibition of Cdk2 activity compared to cells overexpressing either p21 wt or the p21Cip1 T145A construct (Fig. 6C). p21Cip1 overexpression also inhibited the kinase activity of Cdk4, though to a lesser extent than Cdk2 (data not shown). However, no difference in Cdk4 activity was determined by comparing the different p21 contructs (data not shown). Taken together, Akt-dependent phosphorylation of p21Cip1 ameliorates the Cdk2 inhibitory function of p21Cip1, presumably by interfering with p21Cip1-Cdk2 complex formation, whereas Cdk4 activity remained unchanged.

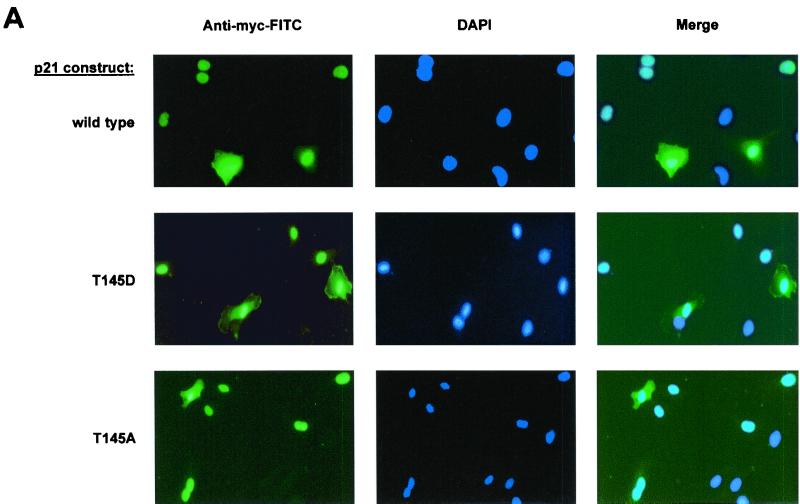

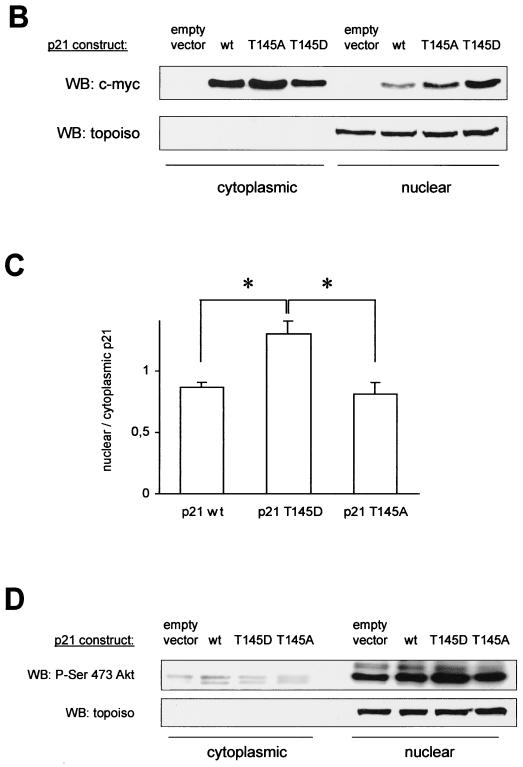

Thr 145 phosphorylation and subcellular localization of p21Cip1.

Since the nuclear translocation sequence of p21Cip1 is localized within the PCNA binding site, we tested whether the functional effects of Akt-dependent p21Cip1 phosphorylation on PCNA and Cdk binding may be caused by an effect on the subcellular localization of p21Cip1. Immunocytochemical staining of endothelial cells demonstrates that p21 wt, the nonphosphorylatable T145A, and the phospho-mimetic T145D construct localize to both the nucleus and the cytoplasm (Fig. 7A). About one-third of the cells revealed strong cytoplasmic staining of p21Cip1, whereas a predominant nuclear localization was detected in 70% of the endothelial cells (Fig. 7A). The numbers of cells with cytoplasmic staining were similar in cells expressing p21 wt, T145A, and T145D (Fig. 7A and data not shown). Immunoblot analysis of subcellular fractions confirms that p21Cip1 is indeed located in the cytoplasm as well as in the nucleus (Fig. 7B). Interestingly, protein levels of the phosphomimetic p21Cip1 T145D construct appeared even slightly higher in the nuclear fraction than p21 wt and the T145A construct, such that both localize in almost equal amounts to the nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions (Fig. 7C). Consistently, the PI3K inhibitor Ly294002 decreases the protein amount of endogenous p21Cip1 in the nuclear fraction, whereas cytoplasmic p21Cip1 levels remain largely preserved (data not shown). Active Akt mainly localizes to the nucleus of endothelial cells under serum-containing conditions, thus confirming data that were obtained with another cell type (2), with no difference between cells overexpressing the various p21Cip1 constructs (Fig. 7D). These data suggest that, in endothelial cells, Akt-mediated phosphorylation modulates the cell cycle regulatory functions of p21Cip1 not via promoting nuclear export and/or interfering with the nuclear translocation of p21Cip1, but rather via inducing a conformational change of the C terminus of p21Cip1 following Thr 145 phosphorylation.

FIG. 7.

Subcellular distribution of p21Cip1 in dependency on Thr 145 phosphorylation. (A) Immunostaining of human endothelial cells transfected with p21 wt or the Thr 145 constructs. Immunocytochemistry was performed using anti-myc antibody and counterstained with DAPI (n = 4). Due to the limited transfection efficiency, not all cells reveal FITC staining. (B) Immunoblot analysis of p21Cip1 protein levels in the nuclear versus cytoplasmic fraction of HUVEC overexpressing p21 wt and Thr 145 constructs. (C) Densitometric analysis of four individual experiments as in panel B. Data are mean ± SEM; *, P < 0.05 versus the wild type and T145A. (D) Relative subcellular distribution of Akt in nucleus and cytosol of HUVEC transfected with p21Cip1 constructs or vector. A representative result of three individual experiments is shown. In the results shown in panels B and D, immunoblots were reprobed with anti-topoisomerase antibody to verify separation of the nuclear fraction and as a loading control. WB, Western blotting.

PI3K-Akt-dependent regulation of endothelial cell cycle progression.

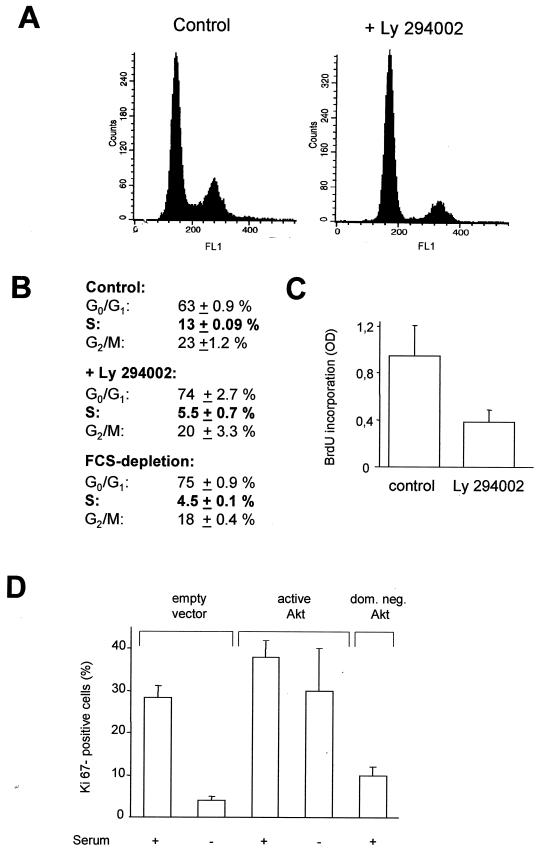

Since Akt-dependent phosphorylation interferes with the cell cycle regulatory functions of p21Cip1, we explored the functional consequences of p21Cip1 phosphorylation by Akt on cell cycle progression of endothelial cells. In the presence of serum, about 13% of endothelial cells are in S phase (Fig. 8A and B). The PI3K inhibitor Ly294002 significantly reduced the percentage of cells in S phase to about 5% (Fig. 8A and B), which is similar to the effect of serum starvation (Fig. 8B). Thus, PI3K-dependent mechanisms are involved in the regulation of endothelial cell proliferation. To assess the contribution of Akt kinase to cell cycle progression, endothelial cells were cotransfected with GFP and various Akt constructs, GFP-positive cells were isolated by FACS, and proliferating cells were identified by immunostaining against the proliferation-associated antigen Ki67, which is only expressed in active phases of the cell cycle, but not in G0 phase (39). Overexpression of active Akt increased endothelial cell proliferation and, importantly, almost entirely compensated for serum depletion-induced cell cycle arrest (Fig. 8D). Consistently, the dominant negative Akt construct markedly suppressed endothelial cell proliferation (Fig. 8D). Proliferation assessment by the BrdU incorporation assay revealed similar results (active Akt, 187% ± 0.5%, and dominant negative Akt, 59% ± 0.6%, compared to vector-transfected cells). These data demonstrate that the PI3K/Akt pathway plays an important role in the regulation of endothelial cell cycle progression.

FIG. 8.

Regulation of endothelial cell proliferation by the PI3K/Akt pathway. (A and B) Serum-stimulated HUVEC were incubated with the PI3K inhibitor Ly294002 (10 μM) or starved for 24 h in serum-free medium plus 1% bovine serum albumin. Cell cycle phases were detected by FACS (data are mean ± SEM; n = 4). (C) HUVEC were incubated with Ly294002 (10 μM) for 24 h, and cell proliferation was assessed by measuring BrdU incorporation via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (data are mean ± SEM; n = 4). (D) HUVEC were cotransfected with GFP (1 μg) and the respective pcDNA3.1 constructs (2 μg) and incubated for 20 h. During the last 12 h, cells were starved in FCS-free medium plus 1% bovine serum albumin. GFP-positive cells were isolated, and proliferating endothelial cells were identified by immunostaining against the proliferative marker protein Ki67. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Ki67-positive cells were counted, and values were calculated as the number of Ki67-positive cells/the number of DAPI-stained nuclei × 100 (data are mean ± SEM; n = 3).

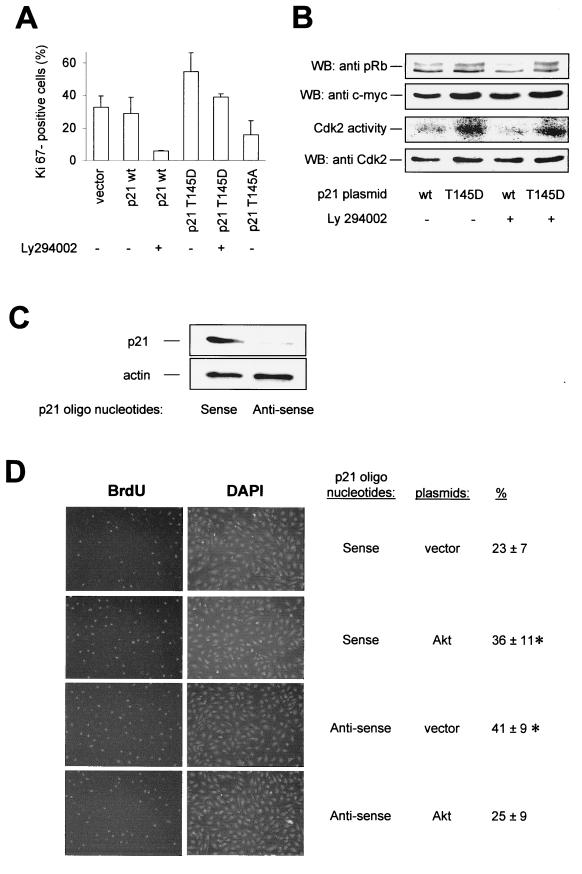

Effect of p21Cip1 Thr 145 phosphorylation on endothelial cell proliferation.

To examine the specific contribution of p21Cip1 phosphorylation, we cotransfected endothelial cells with GFP and either p21 wt or the mutated constructs and analyzed endothelial cell proliferation in GFP-positive cells. Overexpression of p21 wt led to a minor reduction of cell proliferation (Fig. 9A). In contrast, the Akt–phospho-mimetic p21Cip1 construct (T145D) induced an increase in the number of proliferating cells, whereas the nonphosphorylatable p21Cip1 construct (T145A) further reduced endothelial cell proliferation to levels similar to those caused by serum withdrawal or the effect of the dominant negative Akt construct (Fig. 9A). Similarly, inhibition of PI3K with Ly294002 inhibited proliferation in cells transfected with p21 wt but not in cells that were overexpressing p21Cip1 T145D. In accordance with the cell cycle effects, cells overexpressing the T145D construct showed no significant decrease in Cdk2 kinase activity in response to Ly294002 treatment, and these cells were largely resistant to pRb dephosphorylation when compared to p21 wt (Fig. 9B). Then, we analyzed whether Akt-dependent phosphorylation of p21Cip1 mediates the proliferative effects of PI3K. In p21 wt-transfected cells, Ly294002 treatment markedly reduced the number of Ki67-positive endothelial cells, whereas cells transfected with the phospho-mimetic p21Cip1 T145D construct are partially resistant to the cell cycle arrest induced by Ly294002 or serum depletion (Fig. 9A and data not shown). Similar results were obtained when proliferation was assessed by BrdU incorporation. To examine whether the proliferative effect of Akt indeed depends on p21Cip1, endothelial cells were transfected with p21Cip1 antisense oligonucleotides to inhibit endogenous p21Cip1 expression (Fig. 9C). p21Cip1-depleted cells displayed significantly increased proliferation, as detected by BrdU incorporation (Fig. 9D), consistent with a recent report of a similar effect in p21Cip1-null hematopoietic stem cells (9). To assess the dependency of Akt-induced cell proliferation on the availability of p21Cip1, cells were simultaneously transfected with sense or antisense oligonucleotides to p21Cip1, GFP, and Akt or mock transfected, and transfected cells were isolated by fluorescence sorting. Cotransfection of Akt stimulated the proliferation of p21Cip1 sense-transfected endothelial cells, whereas p21Cip1-deficient cells were not responsive to Akt-induced cell proliferation but showed even decreased proliferation when Akt was overexpressed (Fig. 9D).

FIG. 9.

Effect of p21Cip1 Thr 145 phosphorylation on endothelial cell proliferation. (A) HUVEC were cotransfected with GFP (1 μg) and the respective pcDNA3.1 constructs (2 μg) and incubated for 20 h. Then, cells were treated with Ly294002 (10 μM) for 12 h. GFP-positive cells were isolated by FACS, and proliferative endothelial cells were identified by immunostaining against the proliferative marker protein Ki67 (data are mean ± SEM; n = 3 to 4). (B) (Top) Western blot analysis (WB) of pRb phosphorylation in intact cells; the upper band corresponds to hyperphosphorylated pRb and the lower band corresponds to hypophosphorylated pRb in HUVEC overexpressing p21 wt or T145D in the absence or presence of Ly294002. In the second panel from the top, expression of p21Cip1 constructs is shown; in the third panel, an autoradiograph of in vitro-phosphorylated pRb in a Cdk2 kinase assay is shown. The bottom panel shows a Western blot of Cdk2 immunoprecipitates from the respective lysates. (C) HUVEC were transfected with p21Cip1 antisense or sense oligonucleotides, and p21Cip1 protein expression was detected by Western blot analysis using an antibody against endogenous p21Cip1. A representative blot of three individual experiments is shown. (D) Effect of Akt in p21Cip1 antisense-transfected HUVEC that were cotransfected with p21Cip1 antisense or sense oligonucleotides, GFP, and active Akt (T308D/S473D) or vector. Eighteen hours after transfection, the proliferation of GFP-positive cells was assessed by BrdU staining, followed by counterstaining with DAPI. Representative photomicrographs are shown (data are mean ± SEM, n = 3; P < 0.05 versus p21 sense plus vector).

DISCUSSION

We have shown that Akt phosphorylates p21Cip1 specifically at Thr 145 in vitro and in vivo, which results in the release of PCNA from p21Cip1 and regulates the mode of Cdk inhibition by p21Cip1. As a functional consequence, phosphorylation of p21Cip1 abrogates the inhibitory effect of p21Cip1 on cell cycle progression, thereby mediating the proliferative effect of Akt signaling in endothelial cells.

The data of the present study provide evidence that Akt specifically phosphorylates p21Cip1 at Thr 145 in vitro and in intact cells. Akt overexpression leads to the incorporation of 32P into p21 wt, but not into the phosphorylation site-deficient T145A construct. Moreover, serum-induced phosphorylation of endogenous p21Cip1 was reduced by a PI3K inhibitor. These data indicate that Akt can stimulate p21 phosphorylation at Thr 145. However, a recent study by Scott et al. identified Thr 145 within p21Cip1 as a PKA phosphorylation site in an insect cell line (40). Consistent with these data, Akt and PKA displayed equal kinase activities towards Thr 145 in our in vitro experiments. However, PKA inhibitors affected serum-induced cell cycle progression in endothelial cells much less than the PI3K inhibitor Ly294002 or overexpression of dominant negative Akt (S. Dimmeler, unpublished data).This suggests that, in endothelial cells, Akt phosphorylation of Thr 145 of p21Cip1 represents a proliferation signal of potential physiological and/or pathophysiological importance, whereas the functional implications of PKA-dependent p21Cip1 phosphorylation remain to be defined.

PI3K-derived 3′-phosphorylated phospholipids are capable of activating a number of cellular signaling pathways, including tyrosine kinases, GTPase-activating proteins for small G proteins, and a variety of serine/threonine protein kinases such as SGK and the p70 S6 kinase (36). Therefore, a PI3K-coupled mechanism beyond Akt could account for the observed effects of the PI3K inhibitor in endothelial cells. Although we demonstrate that the PI3K-dependent kinases SGK and p70 S6 kinase display no kinase activity towards p21Cip1 in vitro, we cannot formally rule out that other kinases downstream of Akt mediate the phosphorylation as well as the biological effect of p21Cip1 in response to PI3K-Akt-coupled stimuli in vivo.

Recognizing p21Cip1 as a phosphorylated protein implies the possible existence of posttranslation mechanisms regulating p21Cip1, the functional control of which was so far merely attributed to the regulation at the transcriptional level. Posttranslational regulation has previously been reported to regulate protein stability of p21Cip1 and for another cell cycle inhibitor, p27Kip1 (21, 41, 42). Here we demonstrate that phosphorylation of p21Cip1 at Thr 145 provides a novel regulatory mechanism to modulate p21Cip1 function by inducing the release of PCNA from complexes with p21Cip1 and by regulating Cdk2 and Cdk4 complex formation and activity. A previous study has shown that binding of the human papillomavirus type 16 E7 oncoprotein to a sequence overlapping with the PCNA binding site of p21Cip1 interferes with the inhibition of PCNA-dependent DNA replication by p21Cip1 (23). This suggests that the release of PCNA from p21Cip1 enables PCNA to exert its essential function for the process of DNA replication (44). In addition, a broader spectrum of functions is mediated by PCNA beyond DNA replication (for a review, see reference 44). Taking into consideration that p21Cip1 competes with the endonucleases Fen1 and XPG as well as with the DNA methyl transferase Dnmt1 for PCNA binding, these effects could potentially also be regulated by Akt-dependent phosphorylation of p21Cip1 and warrant future investigations on this topic.

In contrast to the complete reversal of PCNA binding, p21Cip1 phosphorylation at Thr 145 only partially inhibited complex formation with Cdk2 and Cdk4 (Fig. 5). This is consistent with previous findings showing that both the cyclin inhibitory sites Cy1 and Cy2, which are located at the N- and C-terminal parts of p21Cip1, respectively (Fig. 1), are necessary for the complete inhibition of Cdk binding (7). Still, the phospho-mimetic mutation of Thr 145 markedly ameliorated the Cdk2 inhibitory activity of p21Cip1. Also, overexpression of the p21Cip1 Thr 145 construct in endothelial cells is associated with a less-compromised phosphorylation of the in vivo Cdk2 substrate, pRb, compared to p21 wt. This suggests that Thr 145 phosphorylation of p21Cip1 has a dual effect on the cell cycle: liberation of PCNA to fulfill its task for DNA replication plus reduction of the amount of inactivated Cdks to manage G0/G1/S-phase transition processes. As the underlying molecular mechanism, growth factor-induced Akt-dependent phosphorylation of p21Cip1 at Thr 145 may induce a conformational change of the PCNA and cyclin-binding domain to modulate the cell cycle inhibitory effects of p21Cip1. Alternatively, Thr 145 phosphorylation of p21Cip1 may create binding sites for other proteins competing with PCNA and/or Cdk binding.

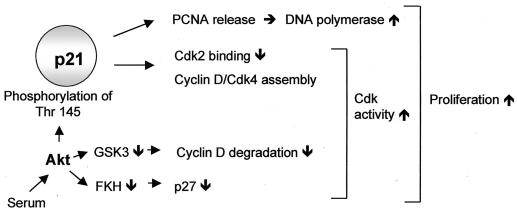

The inhibition of serum-induced endothelial cell cycle progression by overexpression of a dominant negative Akt construct demonstrates a key role for Akt in the regulation of human endothelial cell proliferation. Consistently, stimulation of the PI3K/Akt pathway was previously shown to promote cell cycle progression in other cell types (15, 24, 33, 34). Interestingly, simulation of phosphorylation of p21Cip1 at Thr 145 not only reduces its cell cycle inhibitory effect but even slightly stimulates cell cycle progression. This observation could help to explain the surprising finding that platelet-derived growth factor, a potent activator of the PI3K/Akt pathway, does require the presence of p21Cip1 to stimulate vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation (47) as well as seemingly paradoxical pro-proliferative effects of p21Cip1 revealed by knockout studies, in which cytokine treatment reduced rather than stimulated the proliferation of p21Cip1-null cells (9, 31). Our findings that Akt did not additionally stimulate proliferation of p21Cip1 antisense-transfected cells confirm these data. Previous studies of the mechanisms by which the PI3K/Akt pathway controls proliferation have focused on cell cycle regulators other than p21Cip1. As illustrated in Fig. 10, Akt was shown to transcriptionally down-regulate p27Kip1 expression by inhibition of Forkhead transcription factors and to stabilize cyclin D protein levels via glycogen synthase kinase 3β inhibition (15, 24, 33, 34). Therefore, Akt appears to affect additional signaling pathways, which in concert regulate cell cycle progression (Fig. 10). The importance of the individual signaling pathway may depend on the specific cell type examined and the stimulus used for induction of proliferation. In addition, the cellular differentiation status importantly determines the differential activation of downstream signaling pathways (49).

FIG. 10.

Proposed Akt effector pathways regulating cell cycle progression. The scheme illustrates the data reported in this study in the context of previous publications demonstrating p27 and cyclin D regulation in response to Akt (15, 24, 33, 34). FKH, Forkhead transcription factors; GSK-3, glycogen synthase kinase 3.

Accumulating evidence indicates that Akt plays a key role in angiogenesis regulation both in vitro and in vivo (17, 29). Given that p21Cip1-null mice do not have an obvious endothelial phenotype, the specific contribution of p21Cip1 phosphorylation in mediating Akt-dependent endothelial cell proliferation in vivo has yet to be proven. However, the lack of an overt endothelial phenotype in the absence of p21Cip1 under basal conditions does not negate the potential importance of Akt-dependent p21Cip1 phosphorylation in a disease model. Indeed, recent studies of p21Cip1-null mice showed that p21Cip1 is essential for the regulation of stem cell cycling (9) as well as for the maintenance of progenitor cells (31). Since bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells importantly contribute to neovascularization of ischemic tissue (3), Akt-mediated p21Cip1 phosphorylation and functional modulation could contribute to the mobilization and maintenance of endothelial progenitor cells to warrant timely stem cell cycling. Indeed, preliminary findings indicate that the PI3K/Akt pathway regulates endothelial progenitor cell number and is essential for endothelial progenitor cell function (S. Dimmeler, unpublished). However, further studies are required to investigate whether p21Cip1-null mice are defective in the Akt-mediated angiogenic response to ischemia.

During the preparation of the present manuscript, we noticed the electronic prepublication of Zhou and coworkers that characterizes the interaction of Akt and p21Cip1 in cancer cells (48). To a large proportion, the results of Zhou et al. are in consistence with our data on the specific phosphorylation of p21Cip1 Thr 145 by Akt as well as the functional importance of p21Cip1 phosphorylation for the proliferative effect of Akt kinase. However, in contrast to fibroblasts and cancer cells used in that study, in endothelial cells Akt-mediated phosphorylation does not induce cytoplasmic relocalization of p21Cip1, which Zhou et al. postulated as the underlying mechanism for Akt-mediated proliferation.

In summary, we show that the PI3K/Akt pathway is in addition to the established survival function also involved in the regulation of endothelial cell cycle progression. Phosphorylation of p21Cip1, therefore, mediates at least in part the proliferative effect of Akt. We provide evidence that the functional modulation of p21Cip1 by Akt-dependent phosphorylation involves major alterations in PCNA binding and Cdk complex assembly. These findings characterize a novel pathway by which Akt regulates endothelial cell proliferation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Christiane Mildner-Rihm, Rebeca Salguero-Palacios, Susanne Ficus, and Meike Stahmer for expert technical assistance.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Di600/2-3 and Ba1668/3-1) and the Heinrich und Erna Schaufler-Stiftung. L.R. received a Young Investigator's grant from the University of Frankfurt.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alessi D R, Andjelkovic M, Caudwell B, Cron P, Morrice N, Cohen P, Hemmings B A. Mechanism of activation of protein kinase B by insulin and IGF-1. EMBO J. 1996;15:6541–6551. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andjelkovic M, Alessi D R, Meier R, Fernandez A, Lamb N J, Frech M, Cron P, Cohen P, Lucocq J M, Hemmings B A. Role of translocation in the activation and function of protein kinase B. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31515–31524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asahara T, Masuda H, Takahashi T, Kalka C, Pastore C, Silver M, Kearne M, Magner M, Isner J M. Bone marrow origin of endothelial progenitor cells responsible for postnatal vasculogenesis in physiological and pathological neovascularization. Circ Res. 1999;85:221–228. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.3.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burgering B M T, Coffer P J. Protein kinase B (c-Akt) in phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase signal transduction. Nature. 1995;376:599–602. doi: 10.1038/376599a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cardone M H, Roy N, Stennicke H R, Salvesen G S, Franke T F, Stanbridge E, Frisch S, Reed J C. Regulation of cell death by protease caspase-9 by phosphorylation. Science. 1998;282:1318–1321. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5392.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen J, Jackson P K, Kirschner M W, Dutta A. Separate domains of p21 involved in the inhibition of Cdk kinase and PCNA. Nature. 1995;374:386–388. doi: 10.1038/374386a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen J, Saha P, Kornbluth S, Dynlacht B D, Dutta A. Cyclin-binding motifs are essential for the function of p21CIP1. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4673–4682. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng M, Olivier P, Diehl J A, Fero M, Roussel M F, Roberts J M, Sherr C J. The p21(Cip1) and p27(Kip1) CDK ‘inhibitors’ are essential activators of cyclin D-dependent kinases in murine fibroblasts. EMBO J. 1999;18:1571–1583. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.6.1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng T, Rodrigues N, Shen H, Yang Y, Dombkowski D, Sykes M, Scadden D T. Hematopoietic stem cell quiescence maintained by p21cip1/waf1. Science. 2000;287:1804–1808. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung J, Grammer T C, Lemon K P, Kazlauskas A, Blenis J. PDGF- and insulin-dependent pp70S6k activation mediated by phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase. Nature. 1994;370:71–75. doi: 10.1038/370071a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cross D A, Alessi D R, Cohen P, Andjelkovich M, Hemmings B A. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by insulin mediated by protein kinase B. Nature. 1995;378:785–789. doi: 10.1038/378785a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Datta S R, Brunet A, Greenberg M E. Cellular survival: a play in three Akts. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2905–2927. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.22.2905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Datta S R, Dudek H, Tao X, Masters S, Fu H, Gotoh Y, Greenberg M E. Akt phosphorylation of BAD couples survival signals to the cell-intrinsic death machinery. Cell. 1997;91:231–241. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80405-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.del Peso L, Gonzalez-Garcia M, Page C, Herrera R, Nunez G. Interleukin-3-induced phosphorylation of BAD through the protein kinase Akt. Science. 1997;278:687–689. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diehl J A, Cheng M, Roussel M F, Sherr C J. Glycogen synthase kinase-3â regulates cyclin D1 proteolysis and subcellular localization. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3499–3511. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.22.3499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dimmeler S, Fisslthaler B, Fleming I, Hermann C, Busse R, Zeiher A M. Activation of nitric oxide synthase in endothelial cells via Akt-dependent phosphorylation. Nature. 1999;399:601–605. doi: 10.1038/21224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dimmeler S, Zeiher A M. Akt takes centre stage in angiogenesis signaling. Circ Res. 2000;86:4–5. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.el-Deiry W S, Tokino T, Velculescu V E, Levy D B, Parsons R, Trent J M, Lin D, Mercer W E, Kinzler K W, Vogelstein B. WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell. 1993;75:817–825. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90500-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flores-Rozas H, Kelman Z, Dean F B, Pan Z Q, Harper J W, Elledge S J, O'Donnell M, Hurwitz J. Cdk-interacting protein 1 directly binds with proliferating cell nuclear antigen and inhibits DNA replication catalyzed by the DNA polymerase delta holoenzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8655–8659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franke T F, Yang S-I, Chan T O, Datta K, Kazlauskas A, Morrison D K, Kaplan D R, Tsichlis P N. The protein kinase encoded by the Akt proto-oncogene is a target of the PDGF-activated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Cell. 1995;81:727–736. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90534-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fukuchi K, Watanabe H, Tomoyasu S, Ichimura S, Tatsumi K, Gomi K. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitors, wortmannin or LY294002, inhibited accumulation of p21 protein after gamma-irradiation by stabilization of the protein. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1496:207–220. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(00)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fulton D, Gratton J P, McCabe T J, Fontana J, Fujio Y, Walsh K, Franke T F, Papapetropoulos A, Sessa W C. Regulation of endothelium-derived nitric oxide production by the protein kinase Akt. Nature. 1999;399:597–601. doi: 10.1038/21218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Funk J O, Waga S, Harry J B, Espling E, Stillman B, Galloway D A. Inhibition of CDK activity and PCNA-dependent DNA replication by p21 is blocked by interaction with the HPV-16 E7 oncoprotein. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2090–2100. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.16.2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gille H, Downward J. Multiple ras effector pathways contribute to G(1) cell cycle progression. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:22033–22040. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.22033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gulbis J M, Kelman Z, Hurwitz J, O'Donnell M, Kuriyan J. Structure of the C-terminal region of p21(WAF1/CIP1) complexed with human PCNA. Cell. 1996;87:297–306. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81347-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harper J W, Elledge S J, Keyomarsi K, Dynlacht B, Tsai L H, Zhang P, Dobrowolski S, Bai C, Connell-Crowley L, Swindell E, et al. Inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinases by p21. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:387–400. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.4.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim I, Kim H G, So J-N, Kim J H, Kwak H J, Koh G Y. Angiopoietin-1 regulates endothelial cell survival through the phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase/Akt signal transduction pathway. Circ Res. 2000;86:24–29. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kops G J, de Ruiter N D, De Vries-Smits A M, Powell D R, Bos J L, Burgering B M. Direct control of the Forkhead transcription factor AFX by protein kinase B. Nature. 1999;398:630–634. doi: 10.1038/19328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kureishi Y, Luo Z, Shiojima I, Bialik A, Fulton D, Lefer D J, Sessa W C, Walsh K. The HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor simvastatin activates the protein kinase Akt and promotes angiogenesis in normocholesterolemic animals. Nat Med. 2000;6:1004–1010. doi: 10.1038/79510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.LaBaer J, Garrett M D, Stevenson L F, Slingerland J M, Sandhu C, Chou H S, Fattaey A, Harlow E. New functional activities for the p21 family of CDK inhibitors. Genes Dev. 1997;11:847–862. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.7.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mantel C, Luo Z, Canfield J, Braun S, Deng C, Broxmeyer H E. Involvement of p21cip-1 and p27kip-1 in the molecular mechanisms of steel factor-induced proliferative synergy in vitro and of p21cip-1 in the maintenance of stem/progenitor cells in vivo. Blood. 1996;88:3710–3719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marte B M, Downward J. PKB/Akt: connecting phosphoinositide 3-kinase to cell survival and beyond. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:355–358. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01097-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Medema R H, Kops G J, Bos J L, Burgering B M. AFX-like Forkhead transcription factors mediate cell-cycle regulation by Ras and PKB through p27kip1. Nature. 2000;404:782–787. doi: 10.1038/35008115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muise-Helmericks R C, Grimes H L, Bellacosa A, Malstrom S E, Tsichlis P N, Rosen N. Cyclin D expression is controlled post-transcriptionally via a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:29864–29872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park J, Leong M L, Buse P, Maiyar A C, Firestone G L, Hemmings B A. Serum and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase (SGK) is a target of the PI 3-kinase-stimulated signaling pathway. EMBO J. 1999;18:3024–3033. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.11.3024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rameh L E, Cantley L C. The role of phosphoinositide 3-kinase lipid products in cell function. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:8347–8350. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Romashkova J A, Makarov S S. NF-êB is a target of AKT in anti-apoptotic PDGF signalling. Nature. 1999;401:86–90. doi: 10.1038/43474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rousseau D, Cannella D, Boulaire J, Fitzgerald P, Fotedar A, Fotedar R. Growth inhibition by CDK-cyclin and PCNA binding domains of p21 occurs by distinct mechanisms and is regulated by ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Oncogene. 1999;18:4313–4325. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scholzen T, Gerdes J. The Ki-67 protein: from the known and the unknown. J Cell Physiol. 2000;182:311–322. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200003)182:3<311::AID-JCP1>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scott M T, Morrice N, Ball K L. Reversible phosphorylation at the C-terminal regulatory domain of p21(Waf1/Cip1) modulates proliferating cell nuclear antigen binding. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:11529–11537. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.11529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sheaff R J, Groudine M, Gordon M, Roberts J M, Clurman B E. Cyclin E-CDK2 is a regulator of p27Kip1. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1464–1478. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.11.1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sheaff R J, Singer J D, Swanger J, Smitherman M, Roberts J M, Clurman B E. Proteasomal turnover of p21Cip1 does not require p21Cip1 ubiquitination. Mol Cell. 2000;5:403–410. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80435-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sherr C J, Roberts J M. CDK inhibitors: positive and negative regulators of G1-phase progression. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1501–1512. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.12.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsurimoto T. PCNA, a multifunctional ring on DNA. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1443:23–39. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(98)00204-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Waga S, Hannon G J, Beach D, Stillman B. The p21 inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinases controls DNA replication by interaction with PCNA. Nature. 1994;369:574–578. doi: 10.1038/369574a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Warbrick E, Lane D P, Glover D M, Cox L S. A small peptide inhibitor of DNA replication defines the site of interaction between the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21WAF1 and proliferating cell nuclear antigen. Curr Biol. 1995;5:275–282. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weiss R H, Joo A, Randour C. p21(Waf1/Cip1) is an assembly factor required for platelet-derived growth factor-induced vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:10285–10290. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.14.10285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou B-P, Liao Y, Xia W, Spohn B, Lee M-H, Hung M-C. Cytoplasmic localization of p21Cip1/WAF1 by Akt-induced phosphorylation in HER-2/neu-overexpressing cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:245–252. doi: 10.1038/35060032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zimmermann S, Moelling K. Phosphorylation and regulation of Raf by Akt (protein kinase B) Science. 1999;286:1741–1744. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5445.1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]