Abstract

Odorant receptors (ORs) account for about 60% of all human G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). OR expression outside of the nose has functions distinct from odor perception, and may contribute to the pathogenesis of disorders including brain diseases and cancers. Glioma is the most common adult malignant brain tumor and requires novel therapeutic strategies to improve clinical outcomes. Here, we outlined the expression of brain ORs and investigated OR expression levels in glioma. Although most ORs were not ubiquitously expressed in gliomas, a subset of ORs displayed glioma subtype-specific expression. Moreover, through systematic survival analysis on OR genes, OR51E1 (mouse Olfr558) was identified as a potential biomarker of unfavorable overall survival, and OR2C1 (mouse Olfr15) was identified as a potential biomarker of favorable overall survival in isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) wild-type glioma. In addition to transcriptomic analysis, mutational profiles revealed that somatic mutations in OR genes were detected in > 60% of glioma samples. OR5D18 (mouse Olfr1155) was the most frequently mutated OR gene, and OR5AR1 (mouse Olfr1019) showed IDH wild-type-specific mutation. Based on this systematic analysis and review of the genomic and transcriptomic profiles of ORs in glioma, we suggest that ORs are potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets for glioma.

Keywords: Glioma, GPCR, Odorant receptor, OR51E1, OR51E2

INTRODUCTION

Adult diffuse gliomas account for about 80% of primary malignant tumors in brain. Glioblastoma, which is also referred to as WHO grade IV glioma, is one of the most lethal cancers and is associated with only 15 months median survival (1-3). According to the recent 2021 WHO classification, adult diffuse gliomas can be classified into three subtypes: isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH)-mutant (typically, astrocytoma), IDH mutant with chromosome 1p and 19q co-deletion (typically, oligodendroglioma), and IDH-wildtype (typically, glioblastoma) (4). These three subtypes exhibit distinct genomic features and clinical outcomes. Glioma was at the forefront of the WHO genomic characterization and is one of the most extensively studied cancers (5-7). Yet despite extensive studies on gliomas, new therapeutic strategies are needed to improve clinical outcomes. Exploring as yet under-studied potential drug targets may be key in providing therapeutic options for this disease.

The family of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) is the largest one of transmembrane proteins. They are the largest protein family of druggable targets for approved drugs; about 500-700 drugs that target GPCRs are approved for clinical use (8, 9). Repurposing approved GPCR-targeting drugs is an efficient way of developing new treatment options, as it reduces the time and effort involved in this process. To develop new treatment options for cancer, it is essential to carry out a systematic and intensive analysis of the roles of GPCRs in cancer. Among GPCRs, chemokine receptors, such as C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4), have been widely studied in gliomas (10, 11). However, in non-olfactory tissues, the role of odorant receptors (ORs), which are the largest subfamily of GPCRs and account for about 60% of all human GPCRs, remains unknown (12-14). In particular, the role of ORs in cancers such as glioma is largely unexplored, despite the enormous number of OR genes (13, 15). A well-organized review of non-olfactory GPCRs as therapeutic targets in glioblastoma by Byrne et al. was recently published (16). However, this review was not able to evaluate the potential of ORs as therapeutic targets in glioma due to the limited number of published studies. Here, we have conducted a systematic analysis and review to investigate the potential of ORs as therapeutic targets in glioma.

MAIN TEXT

Classification of HUGO-registered GPCR genes

Human GPCR families have been assigned 1414 unique gene symbols, including pseudogenes, by the HUGO (Human Genome Organization) Gene Nomenclature Committee (17). GPCRs are transmembrane receptors that bind specific ligands and activate intracellular signaling, thereby mediating senses such as vision, smell, and taste (18, 19). There are diverse subgroups within GPCR superfamilies. Human GPCRs can be largely classified into five families based on phylogenetic grouping, namely glutamate, rhodopsin, adhesion, frizzled, and secretin receptors; this grouping is known as the GRAFS classification (20, 21). In particular, the rhodopsin-like class comprises 93% (1315/1414) of human GPCRs, and ORs make up the largest portion, 61.7% (873/1414), of rhodopsin-like GPCRs according to the HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee (17).

OR expressions of brain in normal and diseases models

A previous transcriptome analysis of GPCRs revealed that the expression levels of GPCRs vary by tissue depending on the physiological function of the GPCR (22). ORs are expressed in olfactory epithelium where they conduct their major function of sensing molecules related to smell. In addition, expression of ORs is detected outside of the nose; these receptors are called “ectopic OR” (13, 14, 23). In particular, expression of the limited number of ORs in brain was detected using PCR and in situ hybridization techniques (24-27), and recently, systematic analysis on OR expression using microarray or RNA-sequencing revealed that various ORs such as OR51E1/Olfr558 and OR51E2/Olfr78 were expressed in brain region including cerebellum (28-30). In addition to expression of intact OR gene, Flegel et al. also discovered the chimeric transcript (OR2W3/Olfr322-Trim58) and internal splice variant (OR2L13/Olfr166) of ORs in brain (29). Moreover, altered gene expression levels of ORs were reported in brain diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD); upregulation of Olfr110/111 (human OR5V1) in aging and AD models (31, 32), down-regulation of Olfr1494/OR10Q1, Olfr1324, Olfr1241/OR4A16, and Olfr979/OR10G9 in central nervous system injury (33), down-regulation of OR2L13/Olfr166, OR1E1, OR2J3, OR52L1/Olfr685, and OR11H1 in PD (34), and down-regulation of OR52L1/Olfr685, OR51E1/Olfr558, OR2T1/Olfr31, OR2T33, OR52H1/Olfr648, OR2D2/Olfr715 and OR10G8 in schizophrenia (35). The expression of Olfr316/OR2AK2, Olfr558/OR51E1, Olfr166/OR2L13, Olfr287/OR10AD1, Olfr883, Olfr1344 and Olfr1505/OR9I1 were confirmed in the mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons whose abnormal functions are related to PD and schizophrenia as well (36). We also reported the expression (Olfr110/OR5V1, Olfr111/OR5V1, Olfr920, Olfr1417, and Olfr99/OR1G1) and interaction of brain OR with its ligand in brain cells, such as astrocytes and microglia (37-39). Together, Ferrer et al. emphasized the need to study the role of ORs in mammalian brain; this assertion was based on a summary of studies of ORs in human and mouse brain and the altered OR gene expression levels on neurodegenerative diseases (40).

Publications related to GPCRs in glioma

Next-generation sequencing technology has been widely used in cancer research, including systematic genomic and transcriptomic studies of GPCRs to identify new potential therapeutic targets in cancer (41-44). Until recently, GPCR-based genomic studies focused on non-olfactory receptors, but newer systematic studies highlight the role of ORs as potential contributors to tumorigenesis (45-48).

Given that ORs may have potential oncogenic roles in solid tumors, and that ORs expressed in normal brain and during neurodegenerative disease have functions distinct from odor perception, we hypothesized that ectopic ORs would perform tumor-related functions in brain. As further evidence for the role of ectopic ORs in tumor-related functions in brain, we previously reported that Olfr78 (human homolog, OR51E2) induced M2 polarization, thereby promoting tumor progression and metastasis (49). M2-like tumor-associated macrophages are abundant in the glioma microenvironment, and mediate increased resistance to radiotherapy and immunotherapy (50-52). Glioma is the most common brain malignant tumor. Therefore, a large number of studies have investigated, including the role of GPCRs in glioma. Our current analysis of PubMed literature showed that the oncogenic or tumor-suppressive roles of non-olfactory GPCRs, including CXCR4, SMO, and DRD2, have been reported in over 1,000 publications (Fig. 1A). However, only three publications describing the glioma-related functions of ORs were found: 1) Glioblastoma patients harboring OR4Q3 (mouse Olfr735) mutations have a poor prognosis (53); 2) OR51F2/Olfr568 is a potential mediator of the 4-gene signature predicting temozolomide response in lower-grade glioma (LGG) patients (54); 3) OR7E156P acts as a long non-coding RNA that contributes to tumor growth and invasion via the OR7E156P/miR–143/HIF1A axis in glioma cells (55). Also, recent single-cell tran-scriptome study of ORs in pan-cancer revealed that 65.9% and 55.2% of glioblastoma and astrocytoma cells express OR genes, obeying “one neuron-one receptor” rule (i.e., a single neuron express one OR gene (56, 57) although this study was not searchable in PubMed by the query “(OR gene name [Text Word]) AND (glioma[Text Word]) OR (glioblastoma[Text Word])” (45).

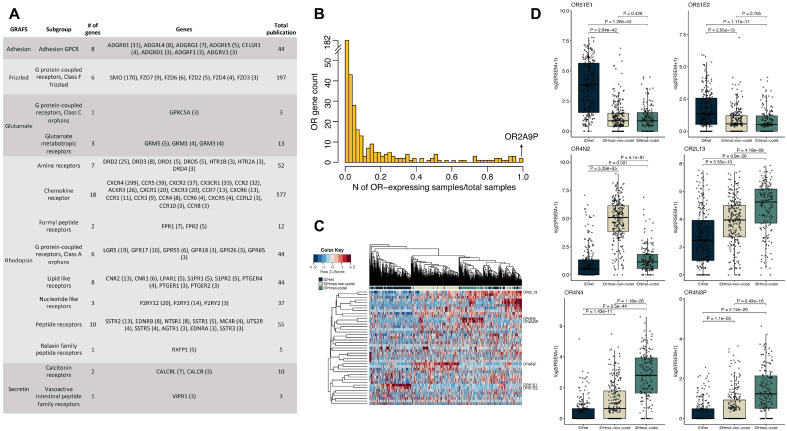

Fig. 1.

GPCR-related publications and the distribution of odorant receptor (OR) gene expression in glioma from the Cancer Genome Atlas. (A) A table describing GPCR genes associated with gliomas in more than two publications. The number in parenthesis represents the number of publications that was found in PubMed. (B) A bar plot showing the OR-expressing sample ratio for each OR gene. The x-axis represents the glioma sample ratio, which is defined by the number of OR-expressing samples divided by the total sample number, and the y-axis represents the number of ORs. (C) A heatmap showing unsupervised clustering of ORs that have highly variable expression levels between samples (standard deviation ≥ 0.3 and expressed in > 33.3% of the total number of samples). (D) A box plot showing OR gene expression levels between the three glioma subtypes. The P-values were calculated from the Student’s t-test. A black dot represents one sample.

RNA expression of GPCRs in glioma

To investigate the overall expression pattern of GPCRs in glioma, we used the integrated RNA-seq-based expression profiles of LGG and glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) from the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA; downloaded from https://gdac.broadinstitute.org/) (6). A total of 656 primary LGG and GBM samples were available, of which 229, 258, and 169 samples were IDH wild-type (IDHwt), IDH mutant without chr1p/chr19q co-deletion (IDHmut-non-codel), and IDH mutant with chr1p/chr19q co-deletion (IDHmut-codel), respectively. In total, 721 GPCR genes were mapped on the integrated LGG and GBM expression profiles, and 375 of 721 genes were categorized as OR genes, including 11 pseudogenes. RNA expression profiles of glioma revealed that 60% of non-olfactory GPCR genes show ubiquitous expression (expressed (log2(RSEM+1) > 0.1) in > 90% of samples, and 81% of the non-olfactory GPCR genes were expressed in more than half of TCGA gliomas. Three-quarters of ORs were barely expressed, and the remainder of ORs were detected only in a subset of gliomas (Fig. 1B). These observations imply that ORs might exhibit sample- or subtype-specific functions in glioma and the glioma microenvironment. Hence, we investigated the expression and mutational profiles of ORs by the glioma subtype and their clinical relevance.

Expression of ORs in glioma

When we explored the expression profiles of ORs in more detail, 373 of 375 (99.5%) ORs mapped on the integrated LGG and GBM expression profiles were expressed in at least one sample (Fig. 1B). However, 237 ORs (63.5%) were expressed only in a small subset (< 5%) of glioma samples. On the other hand, expression of OR2A9P was detected in all gliomas, and another eight ORs (OR7D2, OR2H2/Olfr90, OR7A5/Olfr57, OR2A7, OR13A1/Olfr211, OR2L13/Olfr166, OR2W3/Olfr322, and OR2C1/Olfr15) were expressed in > 90% of glioma samples.

Because glioma subtypes have subtype-specific genomic and clinical features, we performed unsupervised hierarchical clustering using 43 ORs with highly variable expression between glioma samples (standard deviation ≥ 0.3 and expressed in more than one-third of samples) to identify whether the different subtypes of gliomas displayed distinct OR expression profiles (6). Interestingly, each subtype was clustered together, indicating that enrichment of the different subsets of ORs depended on the glioma subtype (Fig. 1C). High expression levels of OR51E1 (mouse Olfr558) and OR51E2 (mouse Olfr78) were noticeable in IDHwt subtypes; OR4N2 (mouse Olfr733) was expressed in IDHmut-non-codel subtypes; and expression of OR2L13 (mouse Olfr166), OR4N4, and OR4N3P was higher in IDHmut-codel subtypes than in other subtypes (Fig. 1C, D). Similar to our findings, Pappula et al. identified the 4637 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between IDH1-mutant and IDH1-wild-type astrocytoma patients, and 18 OR genes including OR4N2 (mouse Olfr733) belonged to the DEGs (58). The distinct expression of ORs in the three glioma subtypes implies that ORs might participate in tumor formation and in the construction of the tumor microenvironment during gliomagenesis.

Clinical relevance of OR expression in glioma

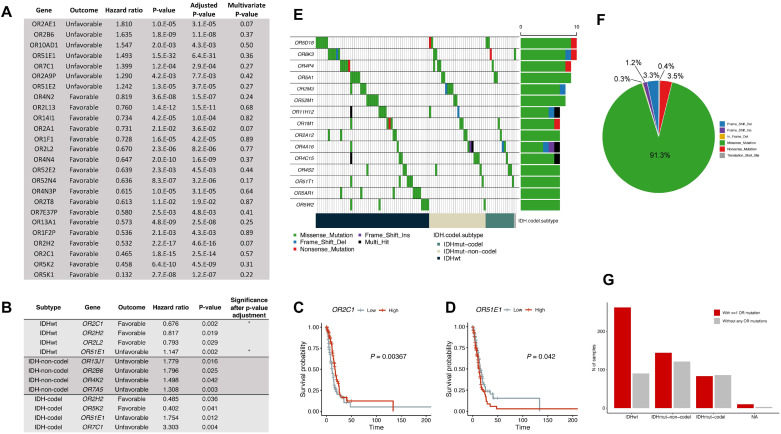

Next, we performed Cox regression survival analysis using gene expression levels to investigate the prognostic potential of OR gene expression. Univariate Cox regression analysis revealed that seven genes (OR2AE1, OR2B6/Olfr11, OR10AD1/Olfr287, OR51E1/Olfr558, OR7C1/Olfr1352, OR2A9P, and OR51E2/Olfr78) were associated with unfavorable overall survival (adjusted P-value < 0.05 and hazard ratio > 1). There were 18 genes associated with favorable overall survival, including OR4N2 (mouse Olfr733), OR4N4, and OR4N3P (adjusted P-value < 0.05 and hazard ratio < 1) (Fig. 2A). However, all of the survival-associated genes were filtered out during multivariate analysis with age, IDH status, and histologic grade; these factors are known prognostic markers of gliomas (59). Therefore, we re-conducted a survival analysis for each subtype. OR51E1 (mouse Olfr558, adjusted P-value = 0.03; hazard ratio = 1.15) and OR2C1 (mouse Olfr15, adjusted P-value = 0.03; hazard ratio = 0.68) were associated with potential unfavorable and favorable outcomes, respectively for IDHwt glioma (Fig. 2B-D). OR51E1 (mouse Olfr558) was previously reported as a potential biomarker for prostate cancer and small intestine neuroendocrine carcinoma (60). Four genes (OR13J1/Olfr71, OR2B6/Olfr11, OR4K2/Olfr730, and OR7A5/Olfr57) were associated with poor overall survival in IDHmut-non-codel gliomas, and another four genes (OR2H2/Olfr90, OR5K2/Olfr177: favorable; OR51E1/Olfr588, OR7C1/Olfr1352: unfavorable) were associated with overall survival in IDHmut-codel gliomas. However, no OR genes were associated with a significant prognosis in the IDHmut-non-codel and IDHmut-codel subtypes after P-value adjustment (Fig. 2B). OR2B6 (mouse Olfr11) has also been previously identified as a cancer biomarker (48); thus further analysis of these identified survival-associated OR genes is needed to determine if they are potential biomarkers and/or therapeutic targets in glioma (46, 48).

Fig. 2.

Cox regression survival analysis of odorant receptor (OR) gene expression levels and somatic mutational profiling of OR genes in glioma. (A) A table describing univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis of overall survival of OR genes in all glioma subtypes. Multivariate analysis was performed with age, IDH status, and histological grade. (B) A table describing OR genes that had expression levels significantly (P < 0.05 before P-value adjustment) associated with overall survival using the Cox proportional hazards regression model. An asterisk indicates the statistical significance after the P-value adjustment (P < 0.05). (C, D) A Kaplan–Meir survival curve showing the survival difference between the OR2C1/Olfr15-high group and the OR2C1/Olfr15-low group (C) or the OR51E1/Olfr558-high group and the OR51E1/Olfr558-low group (D). A high group represents samples with expression levels higher than the median expression level, and the remainder of the samples were assigned as the low group. (E) The mutational landscape of the 15 most mutated OR genes. The bottom bar indicates the glioma subtype, and the right bars indicate the number of samples harboring mutations in each OR gene. (F) The variant type distribution of somatic mutations of OR genes in glioma. (G) Bar plots showing the number of samples that have mutations in at least one OR gene and samples without OR mutations according to glioma subtype.

Mutational profiling of ORs in glioma

Single-nucleotide variants (SNV) and small insertion/deletions (INDEL) can cause changes in protein structure or mRNA degradation through nonsense-mediated mRNA decay; thus, SNV and small INDEL can generate proteins with gain or loss of functions. According to previous studies (61, 62), various natural variants of human ORs exist. Thus, in addition to transcriptomic analysis, we explored the mutational status of ORs in gliomas. Among 799 primary glioma samples that were subjected to either whole-exome or whole-genome sequencing from TCGA, 499 samples carried at least one OR non-silent somatic mutation. Overall, 330 OR genes went through 1056 somatic mutations in the 499 samples, and of the 1056 mutations, 964 (91.3%) were missense mutations (Fig. 2F). For IDHwt gliomas, 262 samples (74.4%) possessed at least one OR mutation, while 144 of 265 (54.3%) IDHmut-non-codel samples and 83 of 169 (49.1%) IDHmut-codel samples had mutations in OR genes (Fig. 2G). Figure 2E summarizes the 15 most mutated OR genes in gliomas. OR5D18 (mouse Olfr1155) was the most frequently mutated OR gene and was detected in 10 samples. Of note, OR5AR1 (mouse Olfr1019) mutations were detected in seven IDHwt samples, but OR5AR1 (mouse Olfr1019) mutations were absent in IDHmut gliomas. Taking these findings together, we suggest that functionally validating mutations in OR genes will be key to understanding the biology of gliomas.

CONCLUSION

To date, the role of ORs in glioma has barely been investigated and is likely to be underestimated. Through a systematic analysis and review of olfactory GPCRs in glioma, we revealed that there is glioma subtype-specific expression of ORs such as OR51E1/Olfr558, OR51E2/Olfr78, OR4N2/Olfr733, OR2L13/Olfr166, OR4N4, and OR4N3P. The existence of subtype-specific OR expression indicates that these ORs likely play roles in tumor formation and in the tumor microenvironment during glioma development or progression. In addition, identifying ORs associated with overall survival rates in glioma patients suggests that the expression level of ORs is a potential biomarker to predict glioma prognosis, and that these ORs should be investigated as therapeutic targets. To evaluate the oncogenic ability of ORs, an in-depth multi-omics analysis should be conducted with patient-derived resources and reliable translational models. Moreover, ORs are expressed in normal brain, and expression is up- and down-regulated in neurodegenerative diseases (32, 34). These observations demonstrate that ORs expressed in brain stromal cells and immune cells might form part of the glioma microenvironment and hence contribute to tumor progression. Therefore, single-cell RNA-sequencing analysis and reliable in vivo and/or in vitro models mimicking the tumor microenvironment are required to screen and functionally validate the cell type-specific expression of ORs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Research Foundation (2021R1A2C1009258 to J. Koo and 2021R1C1C1 004653 to H.J. Cho), the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program (2020M3A9D3038435 to J. Koo), the Korean Mouse Phenotype Center (2019M3A9D5A01102797 to J. Koo).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicting interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schwartzbaum JA, Fisher JL, Aldape KD, Wrensch M. Epidemiology and molecular pathology of glioma. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2006;2:494–503. quiz 491 p following 516. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wen PY, Kesari S. Malignant gliomas in adults. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:492–507. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0708126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Louis DN, Perry A, Wesseling P, et al. The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Neuro Oncol. 2021;23:1231–1251. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noab106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brennan CW, Verhaak RG, McKenna A, et al. The somatic genomic landscape of glioblastoma. Cell. 2013;155:462–477. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ceccarelli M, Barthel FP, Malta TM, et al. Molecular profiling reveals biologically discrete subsets and pathways of progression in diffuse glioma. Cell. 2016;164:550–563. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N, Brat DJ, Verhaak RG, et al. Comprehensive, integrative genomic analysis of diffuse lower-grade gliomas. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2481–2498. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.iram K, Sr, Insel PA. G protein-coupled receptors as targets for approved drugs: how many targets and how many drugs? Mol Pharmacol. 2018;93:251–258. doi: 10.1124/mol.117.111062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hauser AS, Attwood MM, Rask-Andersen M, Schioth HB, Gloriam DE. Trends in GPCR drug discovery: new agents, targets and indications. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16:829–842. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu A, Maxwell R, Xia Y, et al. Combination anti-CXCR4 and anti-PD-1 immunotherapy provides survival benefit in glioblastoma through immune cell modulation of tumor microenvironment. J Neurooncol. 2019;143:241–249. doi: 10.1007/s11060-019-03172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou Y, Larsen PH, Hao C, Yong VW. CXCR4 is a major chemokine receptor on glioma cells and mediates their survival. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:49481–49487. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206222200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Pizio A, Behrens M, Krautwurst D. Beyond the flavour: the potential druggability of chemosensory G protein-coupled receptors. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:1402. doi: 10.3390/ijms20061402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang N, Koo J. Olfactory receptors in non-chemosensory tissues. BMB Rep. 2012;45:612–622. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2012.45.11.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Massberg D, Hatt H. Human olfactory receptors: novel cellular functions outside of the nose. Physiol Rev. 2018;98:1739–1763. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bjarnadottir TK, Gloriam DE, Hellstrand SH, Kristiansson H, Fredriksson R, Schioth HB. Comprehensive repertoire and phylogenetic analysis of the G protein-coupled receptors in human and mouse. Genomics. 2006;88:263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Byrne KF, Pal A, Curtin JF, Stephens JC, Kinsella GK. G-protein-coupled receptors as therapeutic targets for glioblastoma. Drug Discov Today. 2021;26:2858–2870. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2021.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.HGNC Database, HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee (HGNC), European Molecular Biology Laboratory, European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI), Wellcome Genome Campus, Hinxton, Cambridge CB10 1SD, United Kingdom. 2021. Nov, www.genenames.org.

- 18.Hamm HE. The many faces of G protein signaling. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:669–672. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.2.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iiri T, Farfel Z, Bourne HR. G-protein diseases furnish a model for the turn-on switch. Nature. 1998;394:35–38. doi: 10.1038/27831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fredriksson R, Lagerstrom MC, Lundin LG, Schioth HB. The G-protein-coupled receptors in the human genome form five main families. Phylogenetic analysis, paralogon groups, and fingerprints. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:1256–1272. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.6.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nordstrom KJ, Sallman Almen M, Edstam MM, Fredriksson R, Schioth HB. Independent HHsearch, Needleman--Wunsch-based, and motif analyses reveal the overall hierarchy for most of the G protein-coupled receptor families. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2471–2480. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Regard JB, Sato IT, Coughlin SR. Anatomical profiling of G protein-coupled receptor expression. Cell. 2008;135:561–571. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hakak Y, Shrestha D, Goegel MC, Behan DP, Chalmers DT. Global analysis of G-protein-coupled receptor signaling in human tissues. FEBS Lett. 2003;550:11–17. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(03)00762-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Conzelmann S, Levai O, Bode B, et al. A novel brain receptor is expressed in a distinct population of olfactory sensory neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:3926–3934. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Otaki JM, Yamamoto H, Firestein S. Odorant receptor expression in the mouse cerebral cortex. J Neurobiol. 2004;58:315–327. doi: 10.1002/neu.10272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raming K, Konzelmann S, Breer H. Identification of a novel G-protein coupled receptor expressed in distinct brain regions and a defined olfactory zone. Recept Channels. 1998;6:141–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weber M, Pehl U, Breer H, Strotmann J. Olfactory receptor expressed in ganglia of the autonomic nervous system. J Neurosci Res. 2002;68:176–184. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feldmesser E, Olender T, Khen M, Yanai I, Ophir R, Lancet D. Widespread ectopic expression of olfactory receptor genes. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:121. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flegel C, Manteniotis S, Osthold S, Hatt H, Gisselmann G. Expression profile of ectopic olfactory receptors determined by deep sequencing. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55368. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang X, Rogers M, Tian H, et al. High-throughput microarray detection of olfactory receptor gene expression in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:14168–14173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405350101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gaudel F, Stephan D, Landel V, Sicard G, Feron F, Guiraudie-Capraz G. Expression of the cerebral olfactory receptors Olfr110/111 and Olfr544 is altered during aging and in Alzheimer's disease-like mice. Mol Neurobiol. 2019;56:2057–2072. doi: 10.1007/s12035-018-1196-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ansoleaga B, Garcia-Esparcia P, Llorens F, Moreno J, Aso E, Ferrer I. Dysregulation of brain olfactory and taste receptors in AD, PSP and CJD, and AD-related model. Neuroscience. 2013;248:369–382. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin MS, Chiu IH, Lin CC. Ultrarapid inflammation of the olfactory bulb after spinal cord injury: protective effects of the granulocyte colony-stimulating factor on early neurodegeneration in the brain. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021;13:701702. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2021.701702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garcia-Esparcia P, Schluter A, Carmona M, et al. Functional genomics reveals dysregulation of cortical olfactory receptors in Parkinson disease: novel putative chemoreceptors in the human brain. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2013;72:524–539. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e318294fd76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ansoleaga B, Garcia-Esparcia P, Pinacho R, Haro JM, Ramos B, Ferrer I. Decrease in olfactory and taste receptor expression in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in chronic schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;60:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grison A, Zucchelli S, Urzi A, et al. Mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons express a repertoire of olfactory receptors and respond to odorant-like molecules. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:729. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cho T, Lee C, Lee N, Hong YR, Koo J. Small-chain fatty acid activates astrocytic odorant receptor Olfr920. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;510:383–387. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.01.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee N, Jae Y, Kim M, et al. A pathogen-derived metabolite induces microglial activation via odorant receptors. FEBS J. 2020;287:3841–3870. doi: 10.1111/febs.15234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee N, Sa M, Hong YR, Lee CJ, Koo J. Fatty acid increases cAMP-dependent lactate and MAO-B-dependent GABA production in mouse astrocytes by activating a galphas protein-coupled receptor. Exp Neurobiol. 2018;27:365–376. doi: 10.5607/en.2018.27.5.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ferrer I, Garcia-Esparcia P, Carmona M, et al. Olfactory receptors in non-chemosensory organs: the nervous system in health and disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2016;8:163. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2016.00163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Insel PA, iram K, Sr, Wiley SZ, et al. GPCRomics: GPCR expression in cancer cells and tumors identifies new, potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:431. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.iram K, Sr, Moyung K, Corriden R, Carter H, Insel PA. GPCRs show widespread differential mRNA expression and frequent mutation and copy number variation in solid tumors. PLoS Biol. 2019;17:e3000434. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu V, Yeerna H, Nohata N, et al. Illuminating the Onco-GPCRome: novel G protein-coupled receptor-driven oncocrine networks and targets for cancer immunotherapy. J Biol Chem. 2019;294:11062–11086. doi: 10.1074/jbc.REV119.005601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O'Hayre M, Vazquez-Prado J, Kufareva I, et al. The emerging mutational landscape of G proteins and G-protein-coupled receptors in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:412–424. doi: 10.1038/nrc3521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kalra S, Mittal A, Gupta K, et al. Analysis of single-cell transcriptomes links enrichment of olfactory receptors with cancer cell differentiation status and prognosis. Commun Biol. 2020;3:506. doi: 10.1038/s42003-020-01232-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Masjedi S, Zwiebel LJ, Giorgio TD. Olfactory receptor gene abundance in invasive breast carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2019;9:13736. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-50085-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ranzani M, Iyer V, Ibarra-Soria X, et al. Revisiting olfactory receptors as putative drivers of cancer. Wellcome Open Res. 2017;2:9. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.10646.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weber L, Massberg D, Becker C, et al. Olfactory receptors as biomarkers in human breast carcinoma tissues. Front Oncol. 2018;8:33. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vadevoo SMP, Gunassekaran GR, Lee C, et al. The macrophage odorant receptor Olfr78 mediates the lactate-induced M2 phenotype of tumor-associated macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118:e2102434118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2102434118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sa JK, Chang N, Lee HW, et al. Transcriptional regulatory networks of tumor-associated macrophages that drive malignancy in mesenchymal glioblastoma. Genome Biol. 2020;21:216. doi: 10.1186/s13059-020-02140-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang Q, Hu B, Hu X, et al. Tumor evolution of glioma-intrinsic gene expression subtypes associates with immunological changes in the microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2018;33:152. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhao J, Chen AX, Gartrell RD, et al. Immune and genomic correlates of response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in glioblastoma. Nat Med. 2019;25:462–469. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0349-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yuan Y, Qi P, Xiang W, Yanhui L, Yu L, Qing M. Multi-omics analysis reveals novel subtypes and driver genes in glioblastoma. Front Genet. 2020;11:565341. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.565341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang Q, He Z, Chen Y. Comprehensive analysis reveals a 4-gene signature in predicting response to temozolomide in low-grade glioma patients. Cancer Control. 2019;26:1073274819855118. doi: 10.1177/1073274819855118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhao H, Du P, Peng R, et al. Long noncoding RNA OR7E156P/miR-143/HIF1A axis modulates the malignant behaviors of glioma cell and tumor growth in mice. Front Oncol. 2021;11:690213. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.690213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hanchate NK, Kondoh K, Lu Z, et al. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals receptor transformations during olfactory neurogenesis. Science. 2015;350:1251–1255. doi: 10.1126/science.aad2456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Serizawa S, Miyamichi K, Sakano H. Negative feedback regulation ensures the one neuron-one receptor rule in the mouse olfactory system. Chem Senses. 2005;30 Suppl 1:i99–i100. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjh133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pappula AL, Rasheed S, Mirzaei G, Petreaca RC, Bouley RA. A genome-wide profiling of glioma patients with an IDH1 mutation using the catalogue of somatic mutations in cancer database. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13:4299. doi: 10.3390/cancers13174299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aquilanti E, Miller J, Santagata S, Cahill DP, Brastianos PK. Updates in prognostic markers for gliomas. Neuro Oncol. 2018;20:vii17–vii26. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noy158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cui T, Tsolakis AV, Li SC, et al. Olfactory receptor 51E1 protein as a potential novel tissue biomarker for small intestine neuroendocrine carcinomas. Eur J Endocrinol. 2013;168:253–261. doi: 10.1530/EJE-12-0814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jimenez RC, Casajuana-Martin N, Garcia-Recio A, et al. The mutational landscape of human olfactory G protein-coupled receptors. BMC Biol. 2021;19:21. doi: 10.1186/s12915-021-00962-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Trimmer C, Keller A, Murphy NR, et al. Genetic variation across the human olfactory receptor repertoire alters odor perception. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:9475–9480. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1804106115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]