Key Points

Question

What is the effectiveness of a multistage screening protocol for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) implemented in the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act Part C (hereafter, Part C) early intervention (EI)?

Findings

In this difference-in-difference analysis, ASD screening in EI was associated with a 60% increase in ASD diagnoses compared with standard care. Improvements were greater among Spanish-speaking families compared with English-speaking families.

Meaning

Screening for ASD in EI may improve ASD detection and reduce in health disparities.

This difference-in-difference analysis evaluates the association between a multistage screening protocol for autism spectrum disorder in early intervention settings and incidence autism spectrum disorder detection and diagnosis.

Abstract

Importance

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends referring children at elevated risk of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) for Part C early intervention (EI) services, but notes that EI services often fail to provide ASD screening.

Objective

To evaluate the hypothesis that a multistage screening protocol for ASD implemented in 3 EI settings will increase autism detection, especially among Spanish-speaking families.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Difference-in-differences analyses with propensity score weighting of a quasi-experimental design using administrative data on 3 implementation EI agencies and 9 comparison EI agencies from 2012 to 2018 provided by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health. Eligible children were aged 14 to 36 months, enrolled in EI, had no prior ASD diagnosis or medical condition precluding participation, and had parents who spoke English or Spanish. The final analytic sample included 33 326 unique patients assessed across 150 200 person-quarters.

Exposures

Multistage ASD assessment protocol including ASD screening questionnaires, observational screener, and diagnostic evaluation.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Increased incidence of ASD diagnoses as documented in Department of Public Health records and reductions in language-associated health care disparities.

Results

Implementation of screening at 3 EI sites was associated with a significant increase in the rate of ASD diagnoses (incidence rate ratios [IRR], 1.6; 95% CI, 1.3-2.1; P < .001), representing an additional 8.1 diagnoses per 1000 children per quarter. Among Spanish-speaking families, screening was also associated with a significant increase in the rate of ASD diagnoses (IRR, 2.6; 95% CI, 1.6-4.3; P < .001), representing 15.4 additional diagnoses per 1000 children per quarter—a larger increase than for non–Spanish-speaking families (interaction IRR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.0-3.1; P = .005). Exploratory analyses revealed that screening was associated with a larger increase in the rate of ASD diagnoses among boys (IRR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.4-2.3; P < .001) than among girls (IRR, 1.1; 95% CI, 0.6-1.7; P = .84).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study, associations between increased rates of ASD diagnoses and reductions in disparities for Spanish-speaking households support the effectiveness of multistage screening in EI. This study provides a comprehensive evaluation of ASD screening in EI settings as well as a rigorous evaluation of ASD screening in any setting with a no-screening comparison condition. Given that the intervention included multiple components, mechanisms of action warrant further research, as do disparities by child sex.

Introduction

With federal funding through Part C of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, all US states and territories offer Early Intervention (EI) developmental services for families of children younger than 3 years. These services are critical for addressing autism spectrum disorder (ASD)—a condition identified in about 1 in 54 children in the US,1 most frequently after age 3 years.2 The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends that “once a child is determined to be at risk for a diagnosis of ASD…a timely referral for clinical diagnostic evaluation and early intervention or school services is indicated.”3 Indeed, the US Preventive Services Task Force observes that “for many primary care providers, the most common referral pathway is a referral to Early Intervention (Part C) programs within their states.”4

As the US Preventive Services Task Force notes, “State Part C systems are increasingly incorporating specific ASD screens into their own eligibility process,”4 and there are many good reasons for doing so. First, many of the AAP’s reasons for recommending ASD screening in pediatric settings apply equally to EI. Like primary care clinicians, EI specialists have “critical access to the child,”3 which can be leveraged “to identify symptoms of ASD early in childhood, support the family through the process of diagnosis and intervention,”3 and help the family engage in shared decision-making. Second, because EI specialists typically meet frequently with families, they are often well-situated to address common challenges to pediatric care, such as promoting follow-through with “referral for and tracking of evaluation and services.”3 Third, evidence suggests that universal screening in pediatric settings is not sufficient to detect and diagnose all children with ASD. As the AAP notes, “Early screening does not identify many children with milder symptoms and typical cognitive ability as at risk for ASD”3—an observation that is consistent with recent data demonstrating that less than half of children diagnosed with ASD by age 4 years have positive screening scores on standard screening questionnaires.5 Because EI serves children younger than 3 years, it is an ideal setting to enhance early detection.

However, availability and intensity of EI services vary widely, especially for children with ASD. As the AAP notes, “Pediatricians cannot assume that early intervention systems will screen participants being served for language or global delays for ASD at the recommended ages.”3 To address this gap, we implemented an evidence-based, multistage screening protocol in 3 large EI sites. In addition, extensive research documents that low family income, racial or ethnic minority status, and being non–English-speaking are associated with less timely diagnoses of ASD.6,7,8,9 Therefore, our protocol sought to address health disparities.

In prior work,10 we demonstrated that implementation of our EI screening protocol resulted in a high proportion of ASD diagnoses and that there were no differences in rates of participation or referral with respect to race, ethnicity, or language at any stage in our screening process. In this report, we evaluate the screening protocol using a large administrative data set maintained by the Department of Public Health (DPH) that includes records of all children served by EI statewide, allowing inclusion of all children regardless of participation in screening. Identification of 9 additional EI sites that serve populations similar to those at the 3 implementation sites offers a standard care comparison condition. Using a quasi-experimental design to test the degree to which diagnosis of ASD increased following implementation compared with preimplementation and no-implementation controls, we applied econometric methods using difference-in-differences with propensity score weighting to estimate the effectiveness of our multistage screening protocol.

Methods

Data Source

Administrative records from 12 EI agencies collated by the Massachusetts DPH included demographic data, individual family service plans, insurance claims for EI services, and ASD diagnoses. Institutional review boards from UMass Boston University and the Massachusetts DPH approved this study, and individual consent was not required because analyses were limited to secondary analysis of administrative data. The study period was July 1, 2012, the first year when ASD diagnoses were reliably tracked by the DPH, to June 30, 2018, 2 years after implementation at the third study site. Data were analyzed from October 2019 to July 2021. The study followed the Transparent Reporting of Evaluations With Nonrandomized Designs (TREND) reporting guideline and the Reporting of Studies Conducted Using Observational Routinely-Collected Data (RECORD) guidelines.

Study Sample

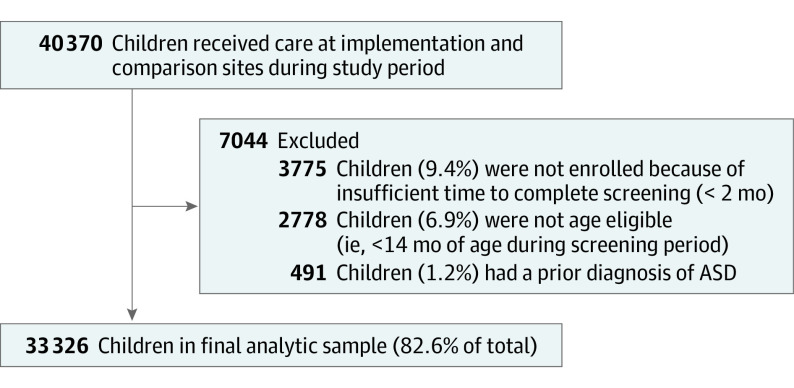

At all sites, all children who met eligibility criteria for the screening intervention were included in our sample. Exclusion criteria were assessed based on DPH data (Figure 1), including child age younger than 14 months, prior ASD diagnosis, and insufficient enrollment duration to complete screening (less than 2 months). In practice, children with chronic health conditions that precluded participation and parents with insufficient English or Spanish language proficiency to complete questionnaires were also excluded, but these criteria were not recorded in DPH data sets. Therefore, the analytic sample may be overly inclusive of children who were not actually eligible for screening. The final analytic sample consisted of 33 326 unique patients assessed across 150 200 person-quarters.

Figure 1. Children in Analytic Sample.

Multistage Screening Protocol

Whereas research often focuses on the psychometric properties of screening instruments,4 our protocol emphasizes ASD screening as a process that includes clinician and parent decision-making. Previous publications detail the protocol using standardized checklists11 and multimethod process maps to compare enacted implementation with original protocols.12 Here, we summarize protocol elements at the level of the family, EI specialist, and EI practice.

Family-Level Protocol

Parents of eligible children had the opportunity to participate in a multistage assessment protocol. In stage 1, EI specialists administered 2 screening questionnaires: the Brief Infant Toddler Social Emotional Assessment (BITSEA),13 which includes an ASD scale, and the Parent’s Observations of Social Interactions (POSI).14,15 In stage 2, EI specialists administered the Screening Tool for ASD in Toddlers and Young children (STAT).16,17 Families were referred to the next stage if the child had positive screening scores or if the EI specialist or the parent(s) expressed concern about ASD. Stage 2 was followed by a university-based diagnostic evaluation that included a comprehensive ASD evaluation. Child assessments were administered by postbaccalaureate research assistants or doctoral students in clinical psychology who were trained to research reliability and who were supervised by licensed psychologists who participated in the evaluations (eAppendix in the Supplement, section I.b.). Evaluations included the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition,18 the Mullen Scales of Early Learning,19 the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, Third Edition, parent or caregiver interview,20 and a developmental and medical history questionnaire. Final Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition) ASD diagnoses were based on the clinician’s evaluation and reported to parents and their EI specialists.

EI Specialist–Level Protocol

EI specialists received training in person and/or via prerecorded sessions throughout the implementation period. Training focused on scoring of stage 1 screening questionnaires, heterogeneity of ASD presentation, and discussing concerns with parents. In addition, select EI specialists received advanced training to administer the STAT. All EI specialists were encouraged to attend ASD diagnostic evaluations and feedback sessions, which offered contact with experienced clinicians.

EI Site-Level Protocol

Implementation leaders met with EI program directors at least twice per year. In addition, each site was assigned a research assistant to facilitate distribution of screeners and support scoring. Research staff met with the STAT-trained teams several times per year to review videos and discuss concerns. Finally, research staff met with state-level policy makers and presented at local EI conferences to maintain program support.

To mitigate linguistic disparities for Spanish-speaking families, who made up a significant proportion of the population at the 3 study sites, we provided all materials in Spanish and English, ensured that Spanish-speaking EI specialists were trained in the STAT, and hired bilingual research staff to complete evaluations and provide feedback in Spanish.

Implementation and Comparison Groups

The implementation group included all children who were eligible for screening at 1 of the 3 study sites after implementation of the screening intervention. The 3 sites were chosen from neighborhoods designated by the city of Boston, Massachusetts, as having high levels of poverty and health disparities. To optimize resources, the screening intervention was implemented at no more than 1 site per year (in 2013, 2014, and 2016), resulting in a staggered design. The comparison group included children who met eligibility criteria from the 9 EI sites that did not participate in the screening study. These EI sites were chosen from the greater Boston area because they served patient populations that were sociodemographically similar to those at the 3 implementation EI sites (eAppendix in the Supplement, section I.b.).

Outcome Measure

The primary outcome was a binary variable indicating quarter of first diagnosis of ASD, which was ascertained from DPH files based on the presence of date of diagnosis in the ASD-specific file, record of ASD diagnosis at discharge or intake, ASD-specific services outlined in an individualized family service plan, and/or receipt of ASD-specific services. To verify the reliability of the outcome measure, administrative records were linked to research study databases, which included records of ASD diagnoses conducted at a university clinic.10

Statistical Analyses

A propensity score–weighted difference-in-difference approach was used to evaluate change in outcomes. The unit of analysis was the person-quarter. This approach compares outcomes at implementation sites with comparison sites both before and after intervention while accounting for secular trends21 derived from the baseline period. To account for baseline sociodemographic differences between implementation and comparison sites and changes in population characteristics over time, we included inverse probability of treatment weights based on propensity scores to balance on observable characteristics,21 including child sex, race and ethnicity, preferred language (Spanish vs English), poverty status, and public insurance. To do so, we used a multinomial logistic model to estimate propensity scores reflecting the probability of each EI recipient being attributed to the following groups: (1) an intervention site preimplementation, (2) an intervention site postimplementation, (3) a comparison site preimplementation, (4) a comparison site during implementation (after the first site but before the last site initiated screening), and (5) a comparison site postimplementation. For each individual, weights were calculated as the ratio of the propensity associated with being in an implementation site in the preimplementation period to the propensity associated with the site or period to which they actually belonged. This approach supports estimation of average treatment effects on the individual. Weights were truncated at the 99th percentile then stabilized to a mean of 1. Whereas regression analyses revealed statistically significant differences between implementation and comparison sites at baseline, after generating propensity scores, the distribution of each covariate was balanced across groups, with a standardized difference of no more than 20%.22 To address assumptions underlying the difference-in-difference method, we also graphically and statistically tested for differences in preintervention trends for the weighted treatment vs comparison groups. To estimate the effect of the intervention on incidence of ASD, we used generalized estimating equations with a Poisson distribution and log link using the general model structure below:

| Yiq = β0 + β1 × Screeningi + β2 × Quarterq + β3 × (Screeningi × Post Periodq) + β4 × X′iq + μi + εiq |

The outcome variable Yiq is indexed to child i in quarter q. Given the staggered design, we included an interaction term to indicate the postimplementation period at the intervention sites, which reflects the effect of the multistage screening intervention, as well as fixed effects for sites (μ) and quarter.23 All models applied inverse probability of treatment weights based on propensity scores and controlled for a vector of child-level covariates to produce doubly robust estimates,24,25 specified exchangeable correlation structures using robust standard errors to account for repeated patient measures, and reported incidence rate ratios (IRRs), which represent the adjusted interaction between intervention and time. An IRR greater than 1 indicates that the independent variable was associated with greater rates of ASD diagnoses per quarter.

Potential heterogeneity of treatment effects26 by subgroup were analyzed by interacting the difference-in-difference term with select covariates. Subgroup analyses fell into 3 categories: a confirmatory analysis of our hypothesis that multistage screening would have a greater effect for Spanish-speaking than for other families, descriptive analyses of subgroups defined by study site (because of interest in the consistency of implementation) and child sex (because of a prior finding that girls were less likely to be screened and less like to have positive screening scores than boys10), and exploratory analyses of all other covariates as well as stratification on the propensity score.26 Because statistical power for tests of interaction is lower than for main effects,26 results were presented for confirmatory and descriptive subgroup analyses regardless of statistical significance.

Analyses were conducted in Stata version 16 (StataCorp), and α = .05 was considered statistically significant. To account for missing demographic data (≤2.8% of cases per covariate), 20 multiple imputations (MI) were conducted using chained equations. Further detail regarding analyses and variable coding is provided in the eAppendix in the Supplement, section II.

Results

Study population characteristics are presented in Table 1. Prior to applying inverse probability of treatment weights, study populations at implementation sites vs comparison sites included fewer White individuals (52.8% vs 83.1%), more Spanish-speaking parents (28.9% vs 12.5%), more children with public insurance (75.4% vs 60.4%), and more families living below 200% federal poverty level (66.9% vs 54.2%). After weighting using propensity scores, these differences diminished to within prespecified levels.

Table 1. Child and Family Characteristics Before and After Multiple Imputation (MI) and Propensity Weighting.

| Characteristic | Before MI and weighting, No. (%) | After MI and weighting | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention sites | Comparison sites | % | Standardized difference | ||

| Intervention sites | Comparison sites | ||||

| Child age, mean (SD), mo | |||||

| At first EI service | 16.9 (8.5) | 16.4 (8.8) | 15.7 | 16.5 | 0.127 |

| At ASD diagnosis | |||||

| Baseline | 26.4 (4.7) | 25.8 (4.6) | 26.5 | 26.3 | 0.005 |

| Postimplementation | 25.7 (4.7) | 25.8 (4.3) | 25.9 | 25.9 | 0.005 |

| Child racea | |||||

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 765 (9.3) | 2145 (8.6) | 12.4 | 16.9 | 0.170 |

| Black | 2533 (30.7) | 3053 (12.2) | 32.2 | 30.0 | 0.065 |

| White | 4352 (52.8) | 20 845 (83.1) | 46.4 | 51.6 | 0.155 |

| No race reported | 184 (2.2) | 277 (1.1) | NA | NA | NA |

| Preferred language | |||||

| Spanish | 2381 (28.9) | 3141 (12.5) | 24.6 | 23.9 | 0.024 |

| English | 5861 (71.1) | 21 943 (87.5) | 75.4 | 76.1 | [Reference] |

| Child sex | |||||

| Female | 2474 (35.0) | 10 507 (37.0) | 36.6 | 38.4 | [Reference] |

| Male | 5360 (65.0) | 15 813 (63.0) | 63.4 | 61.6 | 0.056 |

| Insurance | |||||

| Medicaid/CHIP | 6212 (75.4) | 15 147 (60.4) | 72.7 | 73.7 | 0.026 |

| Private | 2030 (25.9) | 9937 (37.8) | 27.3 | 26.3 | [Reference] |

| Household income, % FPL | |||||

| <200 | 5517 (66.9) | 13 604 (54.2) | 92.1 | 88.1 | 0.101 |

| 200-300 | 58 (0.7) | 1149 (4.6) | 3.4 | 4.3 | 0.045 |

| 301-400 | 36 (0.4) | 1383 (5.5) | 2.0 | 3.1 | 0.049 |

| 401-550 | 25 (0.3) | 1769 (7.1) | 1.6 | 2.6 | 0.058 |

| 551-750 | 18 (0.2) | 953 (3.8) | 0.6 | 1.3 | 0.060 |

| >750 | 14 (0.2) | 481 (1.9) | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.043 |

| Not reported | 2166 (26.3) | 6981 (27.8) | NA | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: ASD, autism spectrum disorder; EI, early intervention; CHIP, Children’s Health Insurance Program; FPL, federal poverty level; MI, multiple imputations; NA, not applicable.

Race categories are not mutually exclusive. Hispanic ethnicity was not reliably recorded; therefore, only language preference is reported here. Data regarding race and ethnicity were collected from Department of Public Health records, where they were collected in multiple-choice format. Data on race and ethnicity were collected for this study to explore potential health disparities in intervention outcomes.

Association Between Screening and Incidence of ASD

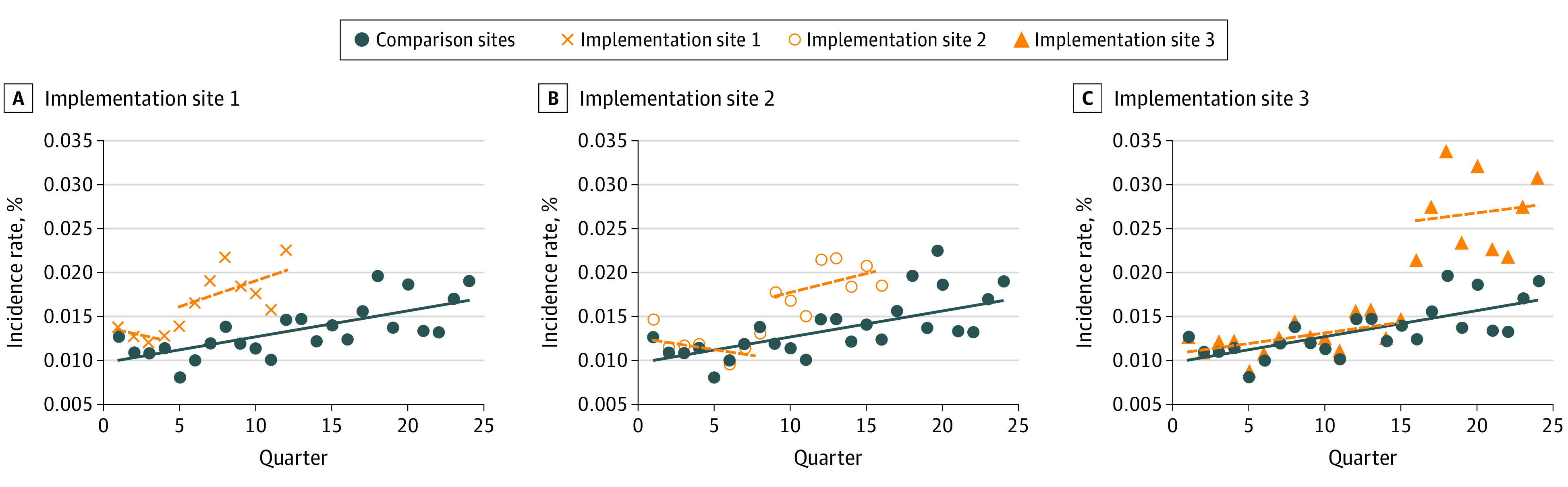

Linear trends at implementation and comparison sites were not statistically different in the preimplementation period, and graphical analyses revealed no further evidence of difference (Figure 2). Comparison sites displayed a secular trend toward increased incidence of ASD diagnoses across the study period (IRR, 1.02 per quarter; 95% CI, 1.01-1.03; P < .001) and graphical analysis suggests heterogeneity in incidence of ASD over time (eAppendix in the Supplement).

Figure 2. Incidence Rates by Implementation Site Compared With Comparison Sites.

Incidence rates represent adjusted values derived from subgroup analyses by intervention site. Covariates include insurance status, preferred language, child race, child sex, and family income with missingness (<3% per variable) addressed through multiple imputation. Analyses also included inversed probability weights based on propensity scores.

Overall, implementation of the screening intervention at the 3 EI sites was associated with a significant increase in the rate of ASD diagnoses compared with baseline (IRR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.3-2.1; P < .001) (Table 2), representing an additional 8.1 diagnoses per 1000 children per quarter. The magnitude of effect was similar across sites, and we observed no statistical difference in the effect of intervention between EI sites. However, when intervention effects were analyzed individually by site, 1 site did not show a statistically significant effect.

Table 2. Association Between Screening Intervention and Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) Incidence in Early Intervention (EI) Settingsa.

| Independent variable | Incidence of ASD per 1000 children per quarter | Difference-in-difference | Interaction | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention sites | Comparison sites | IRR | P value | Marginal effect | IRR | P value | |||

| Preintervention | Postintervention | Preintervention | Postintervention | ||||||

| Overall screening intervention | 12.7 (10.8-15.1) | 21.8 (19.4-24.5) | 12.9 (10.9-15.2) | 17.0 (15.6-18.5) | 1.6 (1.3-2.1) | <.001 | 8.1 (5.4-10.8) | NA | NA |

| Descriptive subgroup analyses | |||||||||

| EI intervention | |||||||||

| Site 1 | 13.3 (10.8-16.5) | 27.5 (22-34.3) | NA | NA | 1.5 (1.1-2.1) | .02 | 8.0 (1.3-14.6) | 0.8 (0.5-1.3) | .44 |

| Site 2 | 10.9 (8.2-14.5) | 21.9 (17.7-27) | NA | NA | 2.0 (1.3-2.9) | <.001 | 12.8 (4.9-20.6) | 1.3 (0.8-2.1) | .27 |

| Site 3 | 14.4 (9-23.2) | 18 (15.3-21.4) | NA | NA | 1.4 (0.8-.5) | .24 | 5.6 (−2.5 to 13.7) | 0.9 (0.5-1.6) | .61 |

| Preferred language | |||||||||

| Spanish | 7.1 (4.7-10.8) | 19.5 (15.4-24.7) | 9.9 (7.5-13) | 13.2 (11.1-15.7) | 2.6 (1.6-4.3) | <.001 | 15.4 (5.3-25.4) | 1.8 (1.0-3.1) | .04 |

| English | 14.5 (12.1-17.5) | 22.8 (20-26.1) | 14.0 (11.9-16.4) | 18.4 (16.8-20.1) | 1.5 (1.1-1.9) | .005 | 6.9 (1.9-12) | [Reference] | NA |

| Child sex | |||||||||

| Female | 8.8 (6.2-12.6) | 10.0 (7.4-13.5) | 7.9 (6.4-9.7) | 9.8 (8.5-11.3) | 1.1 (0.6-1.7) | .84 | 0.5 (−3.9 to 4.8) | [Reference] | NA |

| Male | 16.5 (13.7-19.9) | 31.9 (28-36.2) | 17.8 (15.1-21.1) | 23.9 (21.9-26.1) | 1.8 (1.4-2.3) | <.001 | 14.8 (7.4-22.1) | 1.7 (1-2.9) | .04 |

Abbreviations: IRR, incidence rate ratio; NA, not applicable.

Preestimates and postestimates represent the number of new ASD diagnoses per 1000 children per quarter. The difference-in-difference IRR reflects the estimate representing the interaction between screening status and postperiod status. Difference-in-difference (marginal effect) represents an estimate of the additional number of ASD diagnoses per quarter associated with the independent variable. The interaction (IRR) represents the interaction of the difference-in-difference term with select covariates, which tests whether associations vary by subgroup. An IRR >1 indicates that screening was associated with higher incidence of ASD.

Heterogeneity of Treatment Effects

As hypothesized, screening was associated with a larger increase in ASD diagnoses for Spanish-speaking families than for other families (interaction IRR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.0-3.1; P = .04). Among Spanish-speaking families, the screening intervention was associated with increased incidence (IRR, 2.6; 95% CI, 1.6-4.3; P < .001), representing 15.4 additional diagnoses per 1000 children per quarter. In comparison, the screening intervention was associated with a smaller increase among non-Spanish-speaking families (IRR, 1.5; CI, 1.1-1.9; P = .005), representing 6.9 additional diagnoses per 1000 children per quarter.

Consistent with prior research in the intervention subsample demonstrating that boys were more likely to be screened and more likely to have positive screening scores than girls, descriptive subgroup analyses revealed that, compared with baseline, the screening intervention was associated with a larger increase in ASD diagnoses among boys than among girls (interaction IRR, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.0-2.9; P = .04). For boys, the association between the screening intervention and increased incidence was high (IRR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.4-2.3; P < .001), representing 14.8 additional diagnoses per 1000 children per quarter. In comparison, the association between screening and increased incidence was lower among girls (IRR, 1.1; 95% CI, 0.6-1.7; P = .84), representing 0.5 additional diagnoses per 1000 children per quarter. Exploratory subgroup analyses were nonsignificant for other variables, including insurance status, poverty level, race, and propensity scores.

Discussion

This difference-in-difference analysis found that implementation of multistage screening in EI settings was associated with significant increases in the diagnosis of ASD, especially among Spanish-speaking families. To our knowledge, this represents the first comprehensive evaluation of ASD screening in EI settings, as well as the first rigorous evaluation of ASD screening in any setting to apply quasi-experimental methodologies with a no-screening comparison.

Limitations

We note several limitations. Causal inferences based on econometric methods should be made with caution. Propensity scores mitigate measured but not all unmeasured confounding, and results most likely generalize to diverse urban families similar to those served by our intervention sites. Difference-in-difference designs address potential confounders that vary across groups as long as they are time invariant, and they address time-varying confounders as long as trends are equivalent across sites23; however, site-by-time interactions are unaddressed. In addition, while the sample size was large, the study may have been underpowered for exploratory analyses. Moreover, while screening was associated with increased incidence, explanatory mechanisms warrant further research. The theoretical foundation of the multicomponent protocol rests on prior work demonstrating that cut scores for screening questionnaires typically display modest predictive values27 that are insufficient to justify referral decisions28 and that optimal decision thresholds are informed by evidence regarding the risks, costs, and benefits of referral.29 For this reason, training emphasized use of clinical judgment to identify risk among children with negative screening results as well as sensitivity in discussions with families to maximize engagement. Indeed, prior research on our screening protocol demonstrates that parents often experience high levels of stress during the process of screening and diagnosis,30 and that inclusion of clinical concern as a sufficient ground for referral was effective in improving case detection.31 In addition, enhanced diagnostic services may have influenced clinical decisions by increasing the potential benefit of referral. Further research is required to determine whether these elements represent core features that are necessary to achieve intervention effects.32 Further research is also needed on cost and sustainability, especially given that access to diagnostic evaluations was enhanced as part of screening implementation.

Nonetheless, the results emphasize the importance of monitoring for health disparities in ASD diagnoses. On the one hand, our protocol was designed to reduce diagnostic disparities and results generalize most clearly to racial and minority populations. In particular, the protocol was designed to engage Spanish-speaking families and results demonstrate that screening was associated with more robust outcomes in this population. However, results also suggest that screening was associated with much larger gains for boys than girls—a finding that builds on prior research demonstrating that EI specialists were less likely to screen girls than boys.10 This finding was unexpected, underscoring the importance of monitoring to address potential disparities as they emerge.

Conclusions

In summary, the results of this study demonstrate potential for screening in EI to contribute to improvements in autism detection and service receipt. As one US Preventive Services Task Force member observed, children’s journey from screening to treatment occurs along “a complex process chain” in which children “get screened or do not, get diagnosed with ASD or do not, and respond to therapy or do not.”33 Screening in primary care represents only 1 element in this chain. By focusing on downstream processes in EI settings by which children can be successfully evaluated for ASD, this study highlights the potential impact of collaborative efforts between EI and pediatrics to improve ASD services.

eAppendix

References

- 1.Data & statistics on autism spectrum disorder. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Accessed December 23, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html

- 2.Sheldrick RC, Maye MP, Carter AS. Age at first identification of autism spectrum disorder: an analysis of two US surveys. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(4):313-320. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hyman SL, Levy SE, Myers SM; Council on Children With Disabilities, Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics . Identification, evaluation, and management of children with autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics. 2020;145(1):e20193447. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siu AL, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, et al. ; US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) . Screening for autism spectrum disorder in young children: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;315(7):691-696. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guthrie W, Wallis K, Bennett A, et al. Accuracy of autism screening in a large pediatric network. Pediatrics. 2019;144(4):e20183963. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daniels AM, Mandell DS. Explaining differences in age at autism spectrum disorder diagnosis: a critical review. Autism. 2014;18(5):583-597. doi: 10.1177/1362361313480277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valicenti-McDermott M, Hottinger K, Seijo R, Shulman L. Age at diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders. J Pediatr. 2012;161(3):554-556. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zuckerman KE, Lindly OJ, Reyes NM, et al. Disparities in diagnosis and treatment of autism in Latino and non-Latino White families. Pediatrics. 2017;139(5):e20163010. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-3010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Angell AM, Empey A, Zuckerman KE. A review of diagnosis and service disparities among children with autism from racial and ethnic minority groups in the United States. Int Rev Res Dev Disabil. 2018;55:145-180. doi: 10.1016/bs.irrdd.2018.08.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eisenhower A, Martinez Pedraza F, Sheldrick RC, et al. Multi-stage screening in early intervention: a critical strategy for improving ASD identification and addressing disparities. J Autism Dev Disord. 2021;51(3):868-883. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04429-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Broder Fingert S, Carter A, Pierce K, et al. Implementing systems-based innovations to improve access to early screening, diagnosis, and treatment services for children with autism spectrum disorder: an Autism Spectrum Disorder Pediatric, Early Detection, Engagement, and Services network study. Autism. 2019;23(3):653-664. doi: 10.1177/1362361318766238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mackie TI, Ramella L, Schaefer AJ, et al. Multi-method process maps: an interdisciplinary approach to investigate ad hoc modifications in protocol-driven interventions. J Clin Transl Sci. 2020;4(3):260-269. doi: 10.1017/cts.2020.14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giserman Kiss I, Feldman MS, Sheldrick RC, Carter AS. Developing autism screening criteria for the Brief Infant Toddler Social Emotional Assessment (BITSEA). J Autism Dev Disord. 2017;47(5):1269-1277. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3044-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salisbury LA, Nyce JD, Hannum CD, Sheldrick RC, Perrin EC. Sensitivity and specificity of 2 autism screeners among referred children between 16 and 48 months of age. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2018;39(3):254-258. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith NJ, Sheldrick RC, Perrin EC. An abbreviated screening instrument for autism spectrum disorders. Infant Ment Health J. 2013;34(2):149-155. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21356 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stone WL, Coonrod EE, Ousley OY. Brief report: Screening Tool for Autism in Two-Year-Olds (STAT): development and preliminary data. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000;30(6):607-612. doi: 10.1023/A:1005647629002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stone WL, McMahon CR, Henderson LM. Use of the Screening Tool for Autism in Two-Year-Olds (STAT) for children under 24 months: an exploratory study. Autism. 2008;12(5):557-573. doi: 10.1177/1362361308096403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, et al. The autism diagnostic observation schedule-generic: a standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000;30(3):205-223. doi: 10.1023/A:1005592401947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mullen EM. Mullen Scales of Early Learning. Circle Pines; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sparrow S, Cicchetti D, Saulnier C. Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales. 3rd ed. Pearson; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stuart EA, Huskamp HA, Duckworth K, et al. Using propensity scores in difference-in-differences models to estimate the effects of a policy change. Health Serv Outcomes Res Methodol. 2014;14(4):166-182. doi: 10.1007/s10742-014-0123-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Austin PC, Stuart EA. Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Stat Med. 2015;34(28):3661-3679. doi: 10.1002/sim.6607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wing C, Simon K, Bello-Gomez RA. Designing difference in difference studies: best practices for public health policy research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2018;39(1):453-469. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-013507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Funk MJ, Westreich D, Wiesen C, Stürmer T, Brookhart MA, Davidian M. Doubly robust estimation of causal effects. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(7):761-767. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tan Z. Bounded, efficient and doubly robust estimation with inverse weighting. Biometrika. 2010;97(3):661-682. doi: 10.1093/biomet/asq035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Velentgas P, Dreyer N, Nouriah P, Smith S, Torchia M, eds. Developing a protocol for observational comparative effectiveness research: a user’s guide. 12(13)-EHC099. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Accessed December 23, 2020. https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/related_files/user-guide-observational-cer-130113.pdf [PubMed]

- 27.Sheldrick RC, Benneyan JC, Kiss IG, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Copeland W, Carter AS. Thresholds and accuracy in screening tools for early detection of psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2015;56(9):936-948. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheldrick RC, Garfinkel D. Is a positive developmental-behavioral screening score sufficient to justify referral? a review of evidence and theory. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17(5):464-470. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2017.01.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheldrick RC, Breuer DJ, Hassan R, Chan K, Polk DE, Benneyan J. A system dynamics model of clinical decision thresholds for the detection of developmental-behavioral disorders. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):156. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0517-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mackie TI, Schaefer AJ, Ramella L, et al. Understanding how parents make meaning of their child’s behaviors during screening for autism spectrum disorders: a longitudinal qualitative investigation. J Autism Dev Disord. 2021;51(3):906-921. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04502-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sheldrick RC, Frenette E, Vera JD, et al. What drives detection and diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder? looking under the hood of a multi-stage screening process in early intervention. J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;49(6):2304-2319. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-03913-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silverstein M, Radesky J. Embrace the complexity: the US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation on screening for autism spectrum disorder. JAMA. 2016;315(7):661-662. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix