Abstract

Objective:

Antibody responses are often impaired in old age and in HIV-positive (HIV+) infection despite virologic control with antiretroviral therapy but innate immunologic determinants are not well understood.

Design:

Monocytes and natural killer cells were examined for relationships to age, HIV infection and influenza vaccine responses.

Methods:

Virologically suppressed HIV+ (n=139) and HIV-negative (HIV−) (n=137) participants classified by age as young (18–39 years), middle-aged (40–59 years) and old (≥60 years) were evaluated preinfluenza and postinfluenza vaccination.

Results:

Prevaccination frequencies of inflammatory monocytes were highest in old HIV+ and HIV−, with old HIV+ exhibiting higher frequency of integrin CD11b on inflammatory monocytes that was correlated with age, expression of C-C chemokine receptor-2 (CCR2) and plasma soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor-1 (sTNFR1), with inverse correlation with postvaccination influenza H1N1 antibody titers. Higher frequencies of CD11b+ inflammatory monocytes (CD11bhi, >48.4%) compared with low frequencies of CD11b+ inflammatory monocytes (<15.8%) was associated with higher prevaccination frequencies of total and inflammatory monocytes and higher CCR2 MFI, higher plasma sTNFR1 and CXCL-10 with higher lipopolysaccharide stimulated expression of TNFa and IL-6, concomitant with lower postvaccination influenza antibody titers. In HIV+ CD11bhi expressers, the depletion of inflammatory monocytes from peripheral blood mononuclear cells resulted in enhanced antigen-specific CD4+ T-cell proliferation. Immature CD56hi natural killer cells were lower in young HIV+ compared with young HIV participants.

Conclusion:

Perturbations of innate immunity and inflammation signified by high CD11b on inflammatory monocytes are exacerbated with aging in HIV+ and negatively impact immune function involved in Ab response to influenza vaccination.

Keywords: aging, CD11b, HIV infection, inflammation, inflammatory monocytes, seasonal influenza vaccination, vaccine responses

Introduction

Combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) has improved the life expectancy and quality of life of HIV+ population in recent years [1,2]. However, HIV infection leads to early immunological aging, termed as immune senescence along with onset of age-related chronic diseases and frailty [3–5]. Even in the presence of cART, chronic inflammation and immune activation are not completely reversed [6–8]. Previously, we demonstrated that impaired serologic responses to seasonal influenza vaccines in HIV+ adults on antiretroviral therapy (ART) are associated with deficiencies in components of adaptive immunity [9–12]. In the context of aging, we have reported that both HIV+ and HIV− postmenopausal women had impaired influenza vaccine responses, but the HIV+ women had greater qualitative defects in adaptive immunity in association with underlying inflammation [11,13–14]. We observed that impairment in function of peripheral T-follicular helper cells (pTfh) and ongoing immune activation were associated with altered antigen-specific memory B-cell responses in these women [13]. More recent data in a larger cohort of influenza-vaccinated participants of different ages have expanded these observations and confirmed the presence of defects in CD4+ T cells and B-cell subsets in the context of HIV infection and aging [15,16], but information about the innate immune system is lacking in this regard.

Innate immune cells are the first to interact with microbes in the event of infection or immunization and play an important role in vaccine responses [17–19], and serve as potent antigen-presenting cells for naive and memory CD4+ T cells [20]. Monocytes are necessary for inducing proper immune responses but increase of inflammatory monocyte subsets with age can contribute to suppression of vaccine responses [17–19]. In HIV infection, damage to the gut results in translocation of microbial products to the circulation that persists at a low level despite virologic suppression with cART [8], resulting in chronic activation of immune cells such as monocytes through ligation of Toll-like receptor (TLR)-4 and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines [21,22]. Importantly, inflammatory monocytes are associated with cardiovascular disease, the incidence of which is increased in HIV infection [23,24]. Natural killer cells are also known to be affected by age with redistribution of natural killer cell subsets towards a terminally differentiated subset [25]. In this study, we examined the role of monocytes and natural killer cells in inflammation and vaccine responses in the context of aging and HIV infection.

Materials and methods

Study population and samples

This study (termed FLORAH for FLu Responses Of people in relation to Age and HIV) was conducted during the influenza seasons 2013–2014, 2014–2015 and 2015–2016 with informed consent in participants recruited at the University of Miami clinics and Miami Veteran Affairs Medical Center (MVAMC). Characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. Participants were classified into three groups; young (age 19–39 years), middle aged (40–59 years) and elderly (≥60 years). The study population included a total of 276 participants with 139 HIV+ and 137 HIV− participants, hereafter referred to as healthy controls. HIV+ participants were on combined ART (cART) with virologic suppression (plasma HIV RNA <40 copies/ml) for at least 1 year at the time of recruitment. HIV infection was documented by licensed enzyme immunoassay. HIV+ and healthy controls were matched for age and sex. Individuals receiving hormonal replacement therapy, steroids, immunosuppressant medications, active malignancies and other immunodeficiency disorders were excluded from the study. All study participants were given a single intramuscular (i.m.) vaccine dose of recommended trivalent influenza vaccination (TIV) for the general population for that particular season (2013–2014; Fluzone, Sanofi Pasteur, 2014–2015; Fluzone, Sanofi Pasteur and 2015–2016; Affluria, Seqirus), containing 15 μg hemagglutinin of each vaccine antigen. Peripheral venous blood was collected by venipuncture at prevaccination (baseline, T0), and at day 7 (T1) and days 21–28 (T2) postvaccination after obtaining signed informed consent from the participants. Serum and plasma were stored at −08°C. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were cryopreserved into the vapor phase of liquid nitrogen. For the present study, all participants were analyzed at prevaccination and a sub-group of 125 participants (HIV+ young n=21, middle-aged n=18, old n=29; healthy controls young n=15, middle-aged n=9, old n=33) were analyzed postvaccination. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study participants.

| HC (n=137) | HIV+ (n=139) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Young | Middle | Old | Young | Middle | Old | |

|

| ||||||

| Number | 40 | 56 | 41 | 28 | 67 | 44 |

| Sex (M/F) | 19/21 | 30/26 | 24/17 | 17/11 | 37/30 | 29/17 |

| Mean age in years (range) | 30.2 (19–39) | 51.6 (40–59) | 65.1 (60–83) | 29.3 (19–39) | 51.5 (41–59) | 65 (60–77) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 15 (38) | 17 (30) | 13 (32) | 12 (43) | 16 (24) | 12 (27) |

| Non-Hispanic/non-Latino | 23 (58) | 36 (64) | 24 (58) | 16 (57) | 51 (76) | 29 (66) |

| Not specified | 2 (5) | 3 (5) | 4 (10) | 0 | 0 | 3 (7) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||||

| White | 20 (50) | 23 (41) | 23 (56) | 9 (32) | 18 (27) | 14 (32) |

| Black | 14 (35) | 31 (55) | 13 (32) | 17 (61) | 48 (72) | 30 (68) |

| Asian | 5 (13) | 1 (2) | 5 (12) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Not specified | 1 (3) | 1 (2) | 0 | 2 (7) | 1 (1.5) | 0 |

| pVL copies/ml | ND | ND | ND | <40 | <40 | <40 |

HC, healthy control; pVL, plasma virus load.

Serological assessments

Antibody titers were determined at T0, T1 and T2 in serum by hemmagglutination inhibition (HAI) against individuals vaccine Ags (H1N1, H3N2 and B, gift from Seqirus, Pennsylvania, USA) as described previously [10,26,27]. Seroprotection was defined as a HAI titer of at least 1:40. Participants with a postvaccination titer of at least 1:40 and at least four-fold increase from prevaccination titer were classified as vaccine responders.

Phenotypic characterization of monocytes and natural killer cell subsets

The following monoclonal antibodies (MoAbs) were utilized: CD3-BUV-395 (Clone SK7), CD16-AF647 (3G8), CD45-PeCy5 (HI30), HLA-DR-APCCy7 (L243), CD11B-QDot655 (ICRF44), CD56-QDot605 (HCD56), CX3CR1-PE (2A9–1), CCR2-FITC (K036C2), CD14-PECy7 (MPP9), CCR7-PE-CF594 (150503), invariant natural killer T (Vα24JαQ TCR++, 6B11)(BD Biosciences, San Jose, California, USA) cell and LIVE/DEAD Fixable Aqua Dead Cell Stain Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA).

Cryopreserved PBMC were thawed and rested overnight prior to further processing. For flow cytometry, cells were stained with mAb and resuspended in PBS with 1% paraformaldehyde and acquired on LSRII Fortessa and analyzed using FlowJo (TreeStar, Ashland, Oregon, USA). Live CD45+CD3− cells were gated to identify monocytes, defined as CD56−HLA-DR+CD14+. Natural killer cells were defined as CD45+CD14−CD8−CD56+. Monocyte subsets included classical monocytes (CD14+CD16−, CM), inflammatory monocytes (CD14+CD16+, inflammatory monocytes) and nonclassical monocytes (CD14−CD16+, NCM). Natural killer cell subsets included immature (CD56hiCD16−) and mature CD56dimCD16− and CD56dimCD16+ natural killer cells. Natural killer T cells were defined as live CD45+CD14−CD56+Vα24JαQTCR+. Frequencies of cells expressing CCR2 (CC motif chemokine receptor 2), CX3CR1 (CX3C chemokine receptor 1) and CD11b (integrin alpha M) were analyzed for monocytes and natural killer cell subsets. Activation marker HLA-DR was also analyzed on monocyte subsets.

Cytokine measurements

Plasma levels of soluble cytokines and adhesion molecules (IFNα, IFNγ, IL10, IL17a, IL8, MCP1, TNFα, sICAM, sVCAM) were measured prevaccination using MILLIPLEX cytokine magnetic bead panel in the MAGPIX instrument (Luminex Corporation, Austin, Texas, USA) [14]. MFI were analyzed with MILLIPLEX Analyst Software (EMD Millipore, Temecula, California, USA) and soluble marker levels were determined as pg/ml. sTNFR1 and II were measured using commercially available ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA).

Cytokine detection and gene expression of sorted CD11b+ monocytes

Inflammatory monocytes were bulk-sorted from CD11bhi expressers and CD11blo expressers and stimulated with 50ng/ml lipopolysaccharide (LPS) for 22h for cytokine quantification or 6h for gene expression studies. TNFα and IL-6 were determined in cell supernatants using commercially available kits (Biolegend, San Diego, California, USA). For gene expression studies, cells were lysed using lysis buffer (Invitrogen, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) and targeted preamplification was performed using CellsDirect reagents (Invitrogen) and Taqman gene expression assays (TNF, IL6 and CXCL10) by PCR (50°C for 20 min, 95°C for 2 min, 95°C for 15 s, 18 cycles). Preamplified cDNA was subjected to standard RT-PCR for 40 cycles. For determining relative quantification for each transcript, Ct values were subtracted from house-keeping gene (GAPDH) Ct and then from Unstimulated (Medium) Ct and expressed as ddCT [28].

CD4+ T-cell proliferation following inflammatory monocyte depletion

For proliferation assays, inflammatory monocytes were depleted by sorting from overnight-rested PBMC (T1) from 4 HIV+ CD11bhi-expressing middle-aged participants. The following mAb were utilized: CD3-FITC (SK7), CD56 (NCAM), CD45-PECy5 (HI30), CD4−PerCPCy5.5 (A161A1) (Biolegend). CD14+CD16+ monocyte depleted cells were labeled with Cell Trace violet proliferation dye (Life Technologies, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) and stimulated with 5 μg/ml H1N1 antigen for 5 days. Following stimulation, cells were washed, stained with monoclonal antibodies and live CD3+CD8−CD4+ cells were analyzed for proliferation (Cell Trace dim) by flow cytometry on the BD Fortessa (BD Biosciences).

Statistical analysis

All correlations were evaluated using the Spearman test. The two groups’ comparisons were evaluated using the Mann–Whitney test. Wilcoxon test was performed for the before–after paired analysis. The tests were considered statistically significant with a P value at least 0.05. All the statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 7.02 for Windows, GraphPad Software, La Jolla California, USA (www.graphpad.com).

Results

Alterations in innate cell subsets at prevaccination with aging and HIV infection

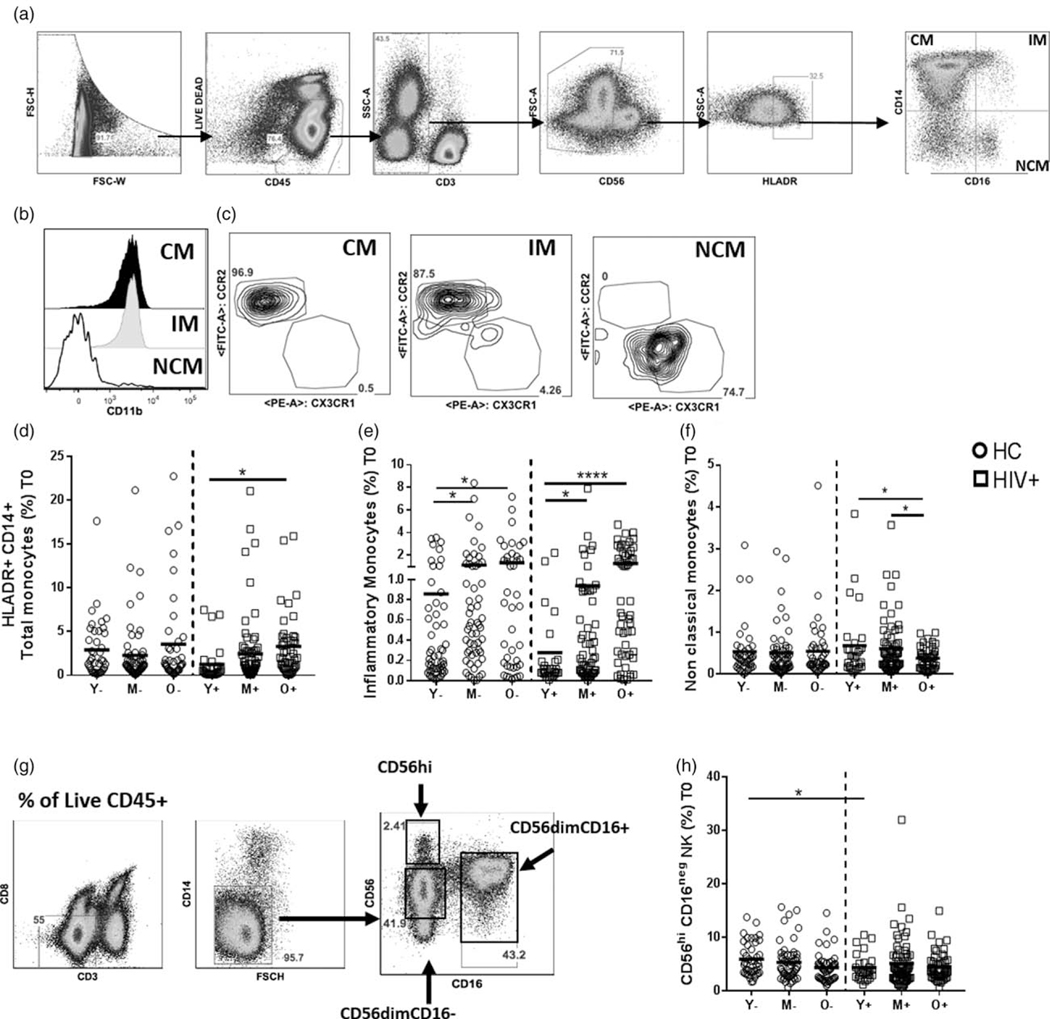

We first determined the contribution of biological age and HIV infection on frequencies of monocytes and natural killer cells in our study participants at prevaccination. In the monocyte compartment, frequencies of total monocytes defined by expression of HLA-DR, CD14+ and CD16+ were higher in old HIV+ compared with young HIV+ participants (Fig. 1a–d). Frequencies of CD14+CD16+ inflammatory monocytes were higher in middle and old age groups compared with young in both HIV+ and healthy control participants (Fig. 1e). Frequencies of nonclassical monocytes (NCM) were higher in middle and young compared with old only in HIV+ participants (Fig. 1f). No changes in classical monocytes were observed in different age groups or between HIV+ and healthy controls participants (Supplementary Fig. 1a, http://links.lww.com/QAD/B258). We did not observe any differences in total natural killer cell frequencies between HIV+ and healthy control participants or between different age groups within HIV+ and healthy control groups (Fig. 1g, Supplementary Fig. 1c, http://links.lww.com/QAD/B258). Young healthy controls showed higher CD56hiCD16− immature natural killer cells at baseline compared with young HIV+ (Fig. 1g–h). No changes in frequencies of other natural killer cell subsets or invariant natural killer T cells were observed between HIV+ and healthy controls or between different age groups (Supplementary Fig. 1d–f, http://links.lww.com/QAD/B258) and there were no correlations among natural killer subsets with age in HIV+ or healthy controls at baseline. These results point to alterations with aging particularly in monocyte subsets in HIV+ participants.

Fig. 1. Frequencies of innate cell subsets in healthy controls and HIV+ participants at baseline.

Cryopreserved PBMC from HIV-infected and healthy participants (n=276, HIV+ n=139, HC, n=137) from different age groups (young; HIV+,Y+ n=28, HC, Y – n=40, middle aged; HIV+, M+ n=67, HC, M – n=56, old; HIV+, O+ n=44, HC, O – n=41) at baseline (pre vaccination) were thawed and rested overnight followed by ex-vivo staining with mAb. (a) Flow cytometric dot plots showing the gating strategy for monocytes from live CD45+ cells. Monocyte subsets are gated from live CD45+HLADR+CD3−CD56− and based on CD14+ and CD16+, they are defined as Classical (CM, CD14hiCD16−), inflammatory (inflammatory monocytes, CD14+CD16+) and nonclassical (NCM, CD14loCD16hi). (b) Histogram depicting CD11b expression on classical monocytes (black solid fill), inflammatory monocytes (grey solid fill) and nonclassical (solid line). (d–f) Frequencies of monocyte subsets at T0 in HIV+ and HC participants. (G) natural killer cells were gated from Live CD45+CD3−CD8−CD14−cells. Based on CD56+ and CD16+, three populations namely, CD56hi immature natural killer cells, CD56dimCD16neg and CD56dim CD16+ mature natural killer cells were analyzed. (h) Frequencies of CD56hiCD16− natural killer cells in HIV+ and HC at baseline. Stars indicate the level of significance. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. HC, healthy controls.

Altered monocyte inflammation in HIVR participants at prevaccination

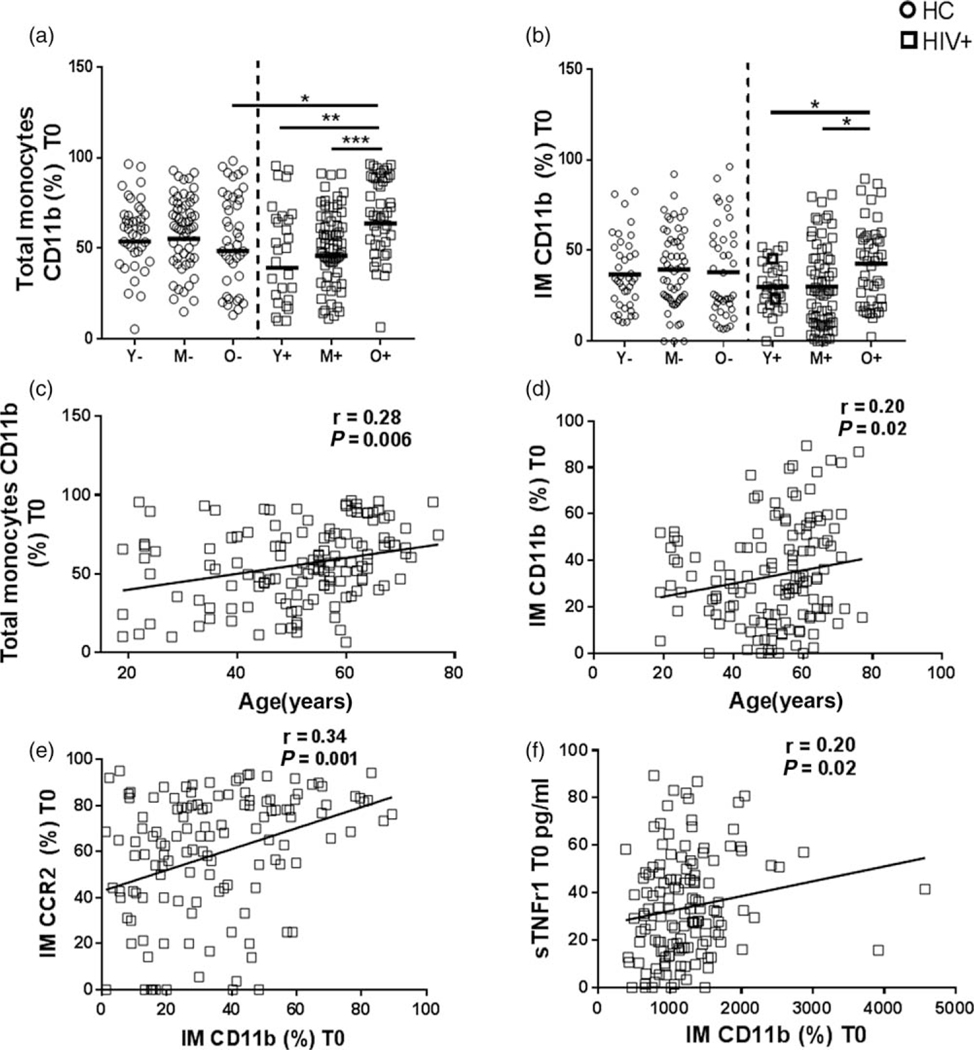

As frequencies of total monocytes and their subsets were altered with age in HIV infection, we assessed the surface expression of activation and inflammatory markers on monocytes at prevaccination. Old healthy controls had higher median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of HLA-DR expression on classical monocytes and inflammatory monocytes than young healthy controls whereas young HIV+ had higher HLA-DR expression on inflammatory monocytes than young healthy controls at prevaccination (Supplementary figure 1b, http://links.lww.com/QAD/B258). Frequencies of total monocytes expressing CD11b+ were higher in old HIV+ compared with old healthy controls (Fig. 2a). In HIV+, CD11b+ total monocytes and inflammatory monocytes correlated with age (Fig. 2b–d). Additionally, we also found a direct correlation between frequency of CD11b and CCR2 expression on inflammatory monocytes in HIV+ participants (Fig. 2e). Frequencies of CD11b+ inflammatory monocytes correlated with plasma sTNFRI at prevaccination only in HIV+ participants (Fig. 2f). No changes in CCR2 and CX3CR1 expression on monocyte subsets were observed with age or HIV infection (data not shown). These results indicate that expression of CD11b on monocyte subsets increases with age and is directly associated with baseline inflammation in HIV infection.

Fig. 2. Elevated frequencies of CD11b expression on monocytes in HIV+ participants at baseline.

Frequencies of (a) CD11b+ total monocytes and (b) CD11b+ inflammatory monocytes at baseline in all age groups in HIV+ and HC participants. Correlation between age and frequencies of (C) CD11b+ total monocytes and (d) CD11b+ inflammatory monocytes at baseline in HIV+ participants by Spearman’s correlation test. (e) Correlation between dual expression of CD11b and CCR2 on inflammatory monocytes in HIV+ participants at baseline. (f) Correlation between frequencies of CD11b+ inflammatory monocytes and plasma soluble TNFrI in HIV+ participants. Stars indicate the level of significance. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001

Elevated expression of CD11b on inflammatory monocytes at prevaccination is associated with impaired antibody responses in HIVR participants

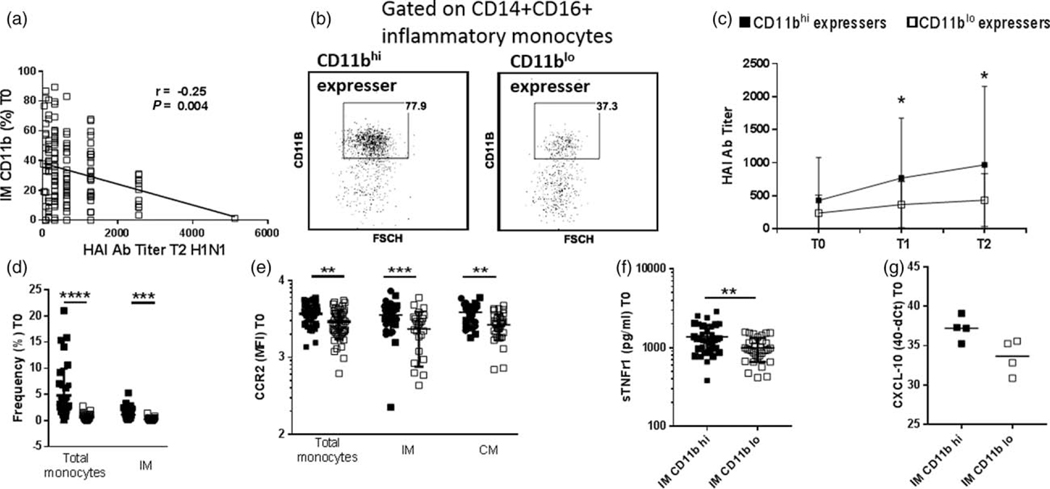

We analyzed changes in natural killer and monocyte subsets following vaccination at 7 days (T1) and 21 days (T2) in a sub-group of 125 participants (HIV+ young n=21, middle aged n=18, old n=29; healthy controls young n=15, middle-aged n=9, old n=33; Supplementary Fig. 2a–h, http://links.lww.com/QAD/B258). Following vaccination at T2, young HIV+ showed increase in CD56dimCD16+ natural killer cells with concomitant decrease in CD56dim CD16− mature natural killer cells and increase in invariant natural killer T cells (Supplementary Fig. 2b–d, http://links.lww.com/QAD/B258). Baseline frequencies of natural killer subsets did not correlate with vaccine responses (data not shown). Old HIV+ showed higher frequencies of total monocytes and inflammatory monocytes at T1 postvaccination compared with young HIV+ (Supplementary Fig. 2e and g, http://links.lww.com/QAD/B258). As a potential role of monocytes in inhibition of vaccine-induced responses has been postulated [17], we questioned whether CD11b expression on inflammatory monocytes influenced influenza vaccine responses. We did not observe any changes in the frequencies of CD11b+ inflammatory monocytes postvaccination in HIV+ or healthy control participants (Supplementary Fig. 3a, http://links.lww.com/QAD/B258). However, frequency of CD11b+ inflammatory monocytes at prevaccination inversely correlated with serum antibody titers against H1N1 Ag at T2 in HIV+ participants (Fig. 3a). As this monocyte phenotype showed no correlation with vaccine responses or with age in healthy controls, further analyses were performed in HIV+ participants.

Fig. 3. HIVR participants expressing high CD11b on inflammatory monocytes have lower antibody responses post vaccination.

(a) Correlation between frequencies of CD11b+ inflammatory monocytes at baseline and hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) antibody titers at week 4 postvaccination in HIV+ participants by Spearman correlation test. (b) HIV+ participants were categorized as those with high frequencies of CD11b+ inflammatory monocytes (upper quartile 75%, frequency of CD11b+ inflammatory monocytes >48.4%, n=34) and those with low frequency of CD11b+ inflammatory monocytes (lower quartile 25%, CD11b+ inflammatory monocytes <15.8, n=33). (c) Comparison of H1N1 antibody titer at T0, T1 and T2 between CD11bhi expressers and CD11blo expressers. (d) Frequencies of total monocytes and inflammatory monocytes in CD11bhi expressers and CD11blo expressers at baseline. (e) CCR2 MFI expression on total monocytes, inflammatory monocytes and classical monocytes in CD11bhi expressers and CD11blo expressers at baseline. (f) sTNFR1 levels in plasma of HIV+ CD11bhi expressers and CD11blo expressers at baseline. (g) CXCL-10 gene expression in sorted inflammatory monocytes from CD11bhi expressers (n=4) and CD11blo expressers (n=4) at baseline. Stars indicate the level of significance.

In order to clearly delineate the contribution of CD11b+ inflammatory monocytes to baseline inflammation, prevaccination inflammatory monocytes in HIV+ participants were dichotomized based on expression of CD11b on these cells. Participants were categorized as CD11blo expressers (25th percentile, CD11b+ inflammatory monocytes <15.8%, n=33; young n=3, middle-aged n=24, old n=6) and CD11bhi expressers (75th percentile CD11b+ inflammatory monocytes >48.4%, n=34; young n=3, middle aged n=15, old n=16), as shown in Fig. 3b. Interestingly, CD11bhi expressers had significantly lower H1N1-specific HAI titers at T1 and T2 compared with CD11blo expressers (Fig. 3c). CD11bhi expressers also showed elevated frequencies of total monocytes, inflammatory monocytes, higher CCR2 expression on total, inflammatory and classical monocytes and higher plasma sTNFRI compared with CD11blo expressers (Fig. 3d–f). In sorted inflammatory monocytes from CD11bhi and CD11blo participants analyzed at prevaccination, CXCL10 gene expression by PCR was elevated in CD11bhi expressers compared with CD11blo expressers (Fig. 3g). Similar results were obtained whenever HIV+ participants were dichotomized based on MFI of CD11b on inflammatory monocytes (Supplementary Fig. 3b–g, http://links.lww.com/QAD/B258).

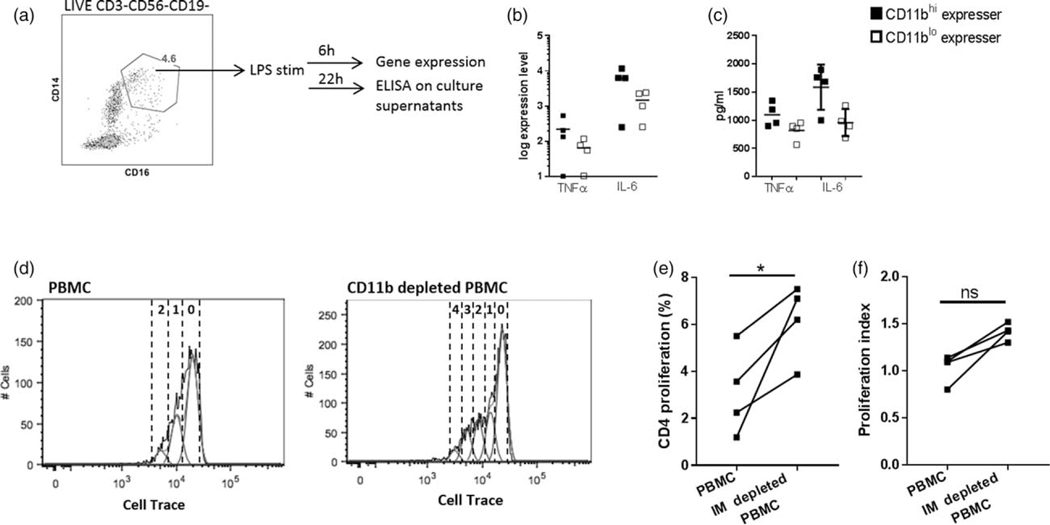

CD11b expression on inflammatory monocytes is associated with inflammatory profile in HIV infection

As high frequencies of CD11b+ inflammatory monocytes in HIV+ participants was associated with higher frequencies of monocytes (total monocytes and inflammatory monocytes), inflammatory markers (CCR2 expression on monocytes, soluble TNFR1) and weakened Ab responses, we analyzed the function of these cells at prevaccination. As shown in Fig. 4a, following 6h of stimulation with LPS of sorted inflammatory monocytes from PBMC of HIV+ CD11bhi and CD11blo expressers, cells of CD11bhi expressers showed higher gene expression levels of TNF and IL-6 by PCR (Fig. 4b). Presence of TNF and IL6 were confirmed by ELISA in cell culture supernatants following LPS stimulation of sorted inflammatory monocytes for 22h (Fig. 4c). Altogether, these data indicate that in HIV+ participants, high expression of CD11b on inflammatory monocytes at prevaccination is associated with underlying inflammation.

Fig. 4. CD11b expression on inflammatory monocytes is associated with inflammatory profile in HIV infection at baseline and inhibit antigen-specific T-cell proliferation.

(a) PBMC from HIV+ CD11bhi expressers (n=4) and CD11blo expressers (n=4) were thawed, rested and CD14+ CD16+ monocytes were sorted and stimulated with LPS (50 ng/ml) for 6 h for gene expression analysis and for 22 h for cytokine estimation in culture supernatants. (b) Expression levels of cytokine genes TNFα and IL6 by real time PCR. (c) Culture supernatants following stimulation with LPS were analyzed for TNFα and IL-6 using commercially ELISA kit. PBMC from CD11bhi expressers (n=4) at T1 were thawed, rested and CD14+ CD16+ inflammatory monocytes were depleted by sorting. Inflammatory monocyte depleted and untouched PBMC was stained with cell trace dye and stimulated with H1N1 Ag (5 μg/ml) for 5 days and CD4+ T-cell proliferation assessed by Cell trace. (d) Representative histogram of whole PBMC and inflammatory monocyte-depleted PBMC from a single HIV+ CD11bhi expresser showing CD4+ T-cell proliferation using Cell Trace violet. (e) Frequencies of Cell Tracedim CD4+ T cells and (f) proliferation index in PBMC and inflammatory monocytes depleted PBMC of CD11bhi expressers.

Inflammatory monocytes from CD11bhi expressers inhibit antigen-specific CD4+ T-cell proliferation

We asked whether depletion of inflammatory monocytes from CD11bhi expressers would result in greater antigen-specific T-cell proliferation. Depletion of inflammatory monocytes from PBMC of CD11bhi expressers resulted in higher CD4+ T-cell proliferation compared with unmanipulated PBMC following 5 days of stimulation with H1N1 antigen (Fig. 4d–f) resulting in four or more divisions as compared with one or two divisions in the unmanipulated PBMC cultures. Together, these results indicate that CD11b+ inflammatory monocytes is associated with higher baseline inflammation in HIV infection and can interfere with antigen-specific adaptive immune responses.

Discussion

Impaired immunity in the aging population and in HIV infection are independently considered to be responsible for suboptimal efficacy of current influenza vaccines [1,29,30]. In order to better comprehend the effects of aging and HIV infection on innate immune responses, we evaluated monocyte and natural killer cell subsets in young, middle aged and old adults.

The data presented in this study indicate that CD11b expression on circulating inflammatory monocytes increases with age in HIV+ participants and is a marker of weakened influenza vaccine responses. Moreover CD11bhi expressers have higher baseline inflammation (CCR2+ monocytes, plasma sTNFR1, TNFα, IL-6 and CXCL-10 gene expression) and that the CD11b+ inflammatory monocytes interfere with proliferation of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells. Proliferation of these CD4+ T cells is a requisite for B-cell differentiation into Ab-secreting cells following influenza vaccination. It is to be noted that even though CD11bhi expressers were constituted of HIV+ participants from all age groups, there were far greater older participants (n=16) than younger (n=3) with this phenotype. Altogether, our data further solidifies the concept of adverse effects of inflammation on immunity and shows the contribution by innate cells at prevaccination in impairing the immune response to influenza vaccination in the aging HIV+ population. We did not find any association of natural killer cells and their subsets with age or antibody responses in HIV+ compared with healthy control participants. We observed lower frequencies of CD56hi immature natural killer subset, a precursor of the mature natural killer, in young HIV+ compared with young healthy at baseline. This is in accordance with previous studies that indicate a decrease in this subset during chronic infection [50]. As we did not evaluate natural killer cells in depth or their functional properties, for example (cytokine secretion), we cannot state definitively whether this subset compromised the immune response in the context of aging and HIV infection [31]. In the context of innate immunity, our study pointed predominantly to a monocyte defect.

Peripheral blood monocytes and tissue macrophages play central roles in responding to infection and are also responsible for the development of comorbidities attributed to inflammation [32–34]. In particular, the CD14+CD16+ inflammatory monocytes are implicated in a variety of disease conditions [35–38]. A recent study showed transcriptional and functional alterations in monocyte subsets including inflammatory monocytes from older healthy individuals compared with young [39]. Following stimulation with pattern recognition receptor agonists, sorted classical monocytes from older healthy adults had enrichment in genes associated with phagocytosis and migration compared with younger adults [39]. Higher frequencies of inflammatory monocytes were also observed in aging [40–42], consistent with our findings in healthy controls. In our study, we observed not only an increase in the frequencies of inflammatory monocytes but also age-associated elevated expression of the inflammatory marker CD11b on inflammatory monocytes in HIV+ participants.

Integrin alpha M or CD11b is a polypeptide linked to the beta subunit of CD18+, which constitute the macrophage-1 antigen (Mac-1) [43]. Resting monocytes constitutively express these integrins, which play a role in migration. Upon cellular activation, changes in the expression levels of these integrin molecules lead to adhesion of monocytes to endothelial cells followed by translocation through the endothelial layer to sites of inflammation [43,44]. Increase in CD11b expression on monocytes has been observed with biologic aging as well as HIV infection and has been shown to correlate with inflammatory soluble markers such as CXCL-10, neopterin and sCD163 [45]. In our study, we found a direct correlation between proinflammatory markers TNFR1 in plasma and CD11b+ inflammatory monocytes (Fig. 2f) only in HIV+ participants. Additionally, expression of CCR2, the receptor for Chemokine ligand-2 (CCL2), which plays an important role in monocyte trafficking to sites of inflammation was correlated with CD11b expression on inflammatory monocytes. These data indicate that CD11b expression on inflammatory monocytes is an indicator of underlying baseline inflammation during HIV infection [43,18]. Interestingly, we observed similar frequencies of CD11b+ inflammatory monocytes in healthy controls compared with HIV+. However, this subset in healthy controls did not correlate with age, antibody responses and baseline plasma soluble markers. Although studies have shown lower CD11b on monocyte subsets in healthy controls compared with HIV+, further investigation into the role of CD11b on inflammatory monocytes in healthy aging is necessary [45].

In our study, sorted inflammatory monocytes from CD11bhi-expressing HIV+ participants confirmed that inflammatory monocytes were highly proinflammatory (production of TNFα and IL-6 following LPS stimulation) compared with CD11blo expressers [46]. The increased responsiveness of CD11bhi-expressing inflammatory monocytes to LPS could also indicate the pro-inflammatory potential of this subset of monocytes in the event of translocation of bacterial products from the gut to the circulation [47]. Previous data has shown that CD11b expression on inflammatory monocytes is directly associated with plasma CXCL-10, a pro-inflammatory chemokine [45]. In line with this, our gene expression data showed that baseline transcript levels of CXCL10 were elevated in CD11bhi expressers compared with CD11blo expressers. Altogether, these results demonstrate that expression of CD11b on inflammatory monocytes identifies a subset involved in ongoing inflammation in HIV infection.

We noted a negative association between CD11b+ inflammatory monocytes and serum antibody titers postvaccination in HIV+ participants. This observation is supported by a recent study in healthy individuals showing that inflammatory responses contributed by monocytes at baseline could be detrimental in induction of influenza vaccine responses with age [17]. Inhibitory effects of monocytes on antigen-specific T-cell proliferation and antibody responses has have been reported in both humans and animal models [17,19,48]. In a mouse model, it was shown that inflammatory monocytes are able to migrate to the lymph nodes and suppress T-cell responses to vaccination [19]. Blockade of this migration led to enhanced cellular and humoral responses to vaccine. The authors demonstrated that inflammatory monocytes suppress T-cell responses by sequestering cysteine as a possible mechanism [19]. Our finding that CD11bhi-expressing inflammatory monocytes were able to inhibit antigen-specific CD4+ T-cell proliferation supports and extends these observations. Further support for this finding stems from the observation that inflammatory monocytes recruited to lymph nodes in a CCR2-dependent fashion in an LCMV model are able to inhibit antiviral B-cell responses [48]. Altogether, these findings point to the potential role of inflammatory monocytes expressing high CD11b in interfering with antigen-specific CD4+ T-cell proliferation following vaccination.

In conclusion, we have shown the contribution of inflammatory monocytes to baseline inflammation and antigen-specific vaccine responses in HIV infection. It should be noted that the observed findings in HIV+ participants related to deleterious effects of inflammatory monocytes were evident, despite HIV suppression with ART [45]. We also did not observe any association between time under ART and CD11b+ inflammatory monocytes (data not shown). Our previous studies on the adaptive responses to influenza vaccination highlighted the importance of peripheral T-follicular helper cells as determinants of a successful vaccine response to influenza vaccination [13,27]. It is conceivable that inflammatory monocytes play an important role in suppressing T-cell responses in draining lymph nodes in response to vaccination [19,49]. Further research on their interaction with Tfh may provide insight into mechanisms underlying inhibition of vaccine responses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the Flow Cytometry Core Facility at University of Miami for facilitating conduct of the flow cytometry and the Clinical Research Center at University of Miami for part of the blood drawn; Seqirus (Maidenhead, UK) for influenza vaccine antigens; Celeste M. Sanchez, Maria Fernanda Pallin, Margaret Roach for providing technical support; Gordon Dickinson, Allan Rodriguez, Margaret Fischl and Maria Alcaide from the Clinical Sciences Core who did patient recruitment; and volunteers who participated in the study.

Financial support: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant: R01AI108472 (to S.P.) and Miami Center for AIDS Research (CFAR, P30AI073961), University of Miami Miller School of Medicine (Miami, Florida), awarded by National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevention and Control of Seasonal Influenza with Vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices –— United States, 2013–2014. MMWR Recomm Rep 2013; 62 (RR07):1–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaplan-Lewis E, Aberg JA, Lee M. Aging with HIV in the ART era. Semin Diagn Pathol 2017; 34:384–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deeks SG. HIV infection, inflammation, immunosenescence, and aging. Annu Rev Med 2011; 62:141–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Appay V, Kelleher AD. Immune activation and immune aging in HIV infection. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2016; 11:242–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fulop T, Herbein G, Cossarizza A, Witkowski JM, Frost E, Dupuis G, et al. Cellular senescence, immunosenescence and HIV. Interdiscip Top Gerontol Geriatr 2017; 42:28–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lichtfuss GF, Hoy J, Rajasuriar R, Kramski M, Crowe SM, Lewin SR. Biomarkers of immune dysfunction following combination antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection. Biomark Med 2011; 5:171–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slim J, Saling CF. A Review of management of inflammation in the HIV population. Biomed Res Int 2016; 2016:3420638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hileman CO, Kinley B, Scharen-Guivel V, Melbourne K, Szwarcberg J, Robinson J, et al. Differential reduction in monocyte activation and vascular inflammation with integrase inhibitor-based initial antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected individuals. J Infect Dis 2015; 212:345–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pallikkuth S, Parmigiani A, Silva SY, George VK, Fischl M, Pahwa R, et al. Impaired peripheral blood T-follicular helper cell function in HIV-infected nonresponders to the 2009 H1N1/09 vaccine. Blood 2012; 120:985–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pallikkuth S, Pilakka Kanthikeel S, Silva SY, Fischl M, Pahwa R, Pahwa S. Upregulation of IL-21 receptor on B cells and IL-21 secretion distinguishes novel 2009 H1N1 vaccine responders from nonresponders among HIV-infected persons on combination antiretroviral therapy. J Immunol 2011; 186: 6173–6181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parmigiani A, Alcaide ML, Freguja R, Pallikkuth S, Frasca D, Fischl MA, et al. Impaired antibody response to influenza vaccine in HIV-infected and uninfected aging women is associated with immune activation and inflammation. PloS One 2013; 8:e79816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pallikkuth S, Kanthikeel SP, Silva SY, Fischl M, Pahwa R, Pahwa S. Innate immune defects correlate with failure of antibody responses to H1N1/09 vaccine in HIV-infected patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011; 128:1279–1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.George VK, Pallikkuth S, Parmigiani A, Alcaide M, Fischl M, Arheart KL, et al. HIV infection worsens age-associated defects in antibody responses to influenza vaccine. J Infect Dis 2015; 211:1959–1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alcaide ML, Parmigiani A, Pallikkuth S, Roach M, Freguja R, Della Negra M, et al. Immune activation in HIV-infected aging women on antiretrovirals–implications for age-associated comorbidities: a cross-sectional pilot study. PloS One 2013; 8:e63804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rinaldi S, Pallikkuth S, George VK, de Armas LR, Pahwa R, Sanchez CM, et al. Paradoxical aging in HIV: immune senescence of B Cells is most prominent in young age. Aging 2017; 9:1307–1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Armas LR, Pallikkuth S, George V, Rinaldi S, Pahwa R, Arheart KL, Pahwa S. Re-evaluation of immune activation in the era of cART and an aging HIV-infected population. J Clin Invest Insight 2017; 2:e95726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakaya HI, Hagan T, Duraisingham SS, Lee EK, Kwissa M, Rouphael N, et al. Systems analysis of immunity to influenza vaccination across multiple years and in diverse populations reveals shared molecular signatures. Immunity 2015; 43: 1186–1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gane JM, Stockley RA, Sapey E. TNF-alpha autocrine feedback loops in human monocytes: the pro- and anti-inflammatory roles of the TNF-alpha receptors support the concept of selective TNFR1 blockade in vivo. J Immunol Res 2016; 2016:1079851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitchell LA, Henderson AJ, Dow SW. Suppression of vaccine immunity by inflammatory monocytes. J Immunol 2012; 189: 5612–5621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warrick JW, Timm A, Swick A, Yin J. Tools for single-cell kinetic analysis of virus-host interactions. PloS One 2016; 11: e0145081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sandler NG, Douek DC. Microbial translocation in HIV infection: causes, consequences and treatment opportunities. Nat Rev Microbiol 2012; 10:655–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zevin AS, McKinnon L, Burgener A, Klatt NR. Microbial translocation and microbiome dysbiosis in HIV-associated immune activation. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2016; 11:182–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wildgruber M, Lee H, Chudnovskiy A, Yoon TJ, Etzrodt M, Pittet MJ, et al. Monocyte subset dynamics in human atherosclerosis can be profiled with magnetic nano-sensors. PloS One 2009; 4:e5663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anzinger JJ, Butterfield TR, Gouillou M, McCune JM, Crowe SM, Palmer CS. Glut1 expression level on inflammatory monocytes is associated with markers of cardiovascular disease risk in HIV-infected individuals. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2018; 77:e28–e30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Camous X, Pera A, Solana R, Larbi A. NK cells in healthy aging and age-associated diseases. J Biomed Biotechnol 2012; 2012:195956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsiung GD, Fong CKY, Landry ML. Hsiung’s diagnostic virology: as illustrated by light and electron microscopy. 4th edn. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1994, 404. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pallikkuth S, Parmigiani A, Silva SY, George VK, Fischl M, Pahwa R, et al. Impaired peripheral blood T-follicular helper cell function in HIV-infected nonresponders to the 2009 H1N1/09 vaccine. Blood 2012; 120:985–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Armas LR, Cotugno N, Pallikkuth S, Pan L, Rinaldi S, Sanchez MC, et al. Induction of IL21 in peripheral T follicular helper cells is an indicator of influenza vaccine response in a previously vaccinated HIV-infected pediatric cohort. J Immunol 2017; 198:1995–2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lambert ND, Ovsyannikova IG, Pankratz VS, Jacobson RM, Poland GA. Understanding the immune response to seasonal influenza vaccination in older adults: a systems biology approach. Expert Rev Vaccines 2012; 11:985–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pera A, Campos C, Lopez N, Hassouneh F, Alonso C, Tarazona R, et al. Immunosenescence: implications for response to infection and vaccination in older people. Maturitas 2015; 82:50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hazeldine J, Lord JM. The impact of ageing on natural killer cell function and potential consequences for health in older adults. Ageing Res Rev 2013; 12:1069–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palmer CS, Crowe SM. How does monocyte metabolism impact inflammation and aging during chronic HIV infection? AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2014; 30:335–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ziegler-Heitbrock L. The CD14+ CD16+ blood monocytes: their role in infection and inflammation. J Leukoc Biol 2007; 81:584–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Albright JM, Dunn RC, Shults JA, Boe DM, Afshar M, Kovacs EJ. Advanced age alters monocyte and macrophage responses. Antioxid Redox Signal 2016; 25:805–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schlitt A, Heine GH, Blankenberg S, Espinola-Klein C, Dopheide JF, Bickel C, et al. CD14+CD16+ monocytes in coronary artery disease and their relationship to serum TNF-alpha levels. Thromb Haemost 2004; 92:419–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takeyama N, Yabuki T, Kumagai T, Takagi S, Takamoto S, Noguchi H. Selective expansion of the CD14(+)/CD16(bright) subpopulation of circulating monocytes in patients with hemophagocytic syndrome. Ann Hematol 2007; 86:787–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Campbell JH, Hearps AC, Martin GE, Williams KC, Crowe SM. The importance of monocytes and macrophages in HIV pathogenesis, treatment, and cure. AIDS 2014; 28:2175–2187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mohanty S, Joshi SR, Ueda I, Wilson J, Blevins TP, Siconolfi B, et al. Prolonged proinflammatory cytokine production in monocytes modulated by interleukin 10 after influenza vaccination in older adults. J Infect Dis 2015; 211:1174–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Metcalf TU, Wilkinson PA, Cameron MJ, Ghneim K, Chiang C, Wertheimer AM, et al. Human monocyte subsets are transcriptionally and functionally altered in aging in response to pattern recognition receptor agonists. J Immunol 2017; 199: 1405–1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seidler S, Zimmermann HW, Bartneck M, Trautwein C, Tacke F. Age-dependent alterations of monocyte subsets and monocyte-related chemokine pathways in healthy adults. BMC Immunol 2010; 11:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hearps AC, Angelovich TA, Jaworowski A, Mills J, Landay AL, Crowe SM. HIV infection and aging of the innate immune system. Sex Health 2011; 8:453–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Angelovich TA, Hearps AC, Maisa A, Martin GE, Lichtfuss GF, Cheng WJ, et al. Viremic and virologically suppressed HIV infection increases age-related changes to monocyte activation equivalent to 12 and 4 years of aging, respectively. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015; 69:11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cifarelli V, LibmanI M, DeLuca A, Becker D, Trucco M, Luppi P. Increased expression of monocyte CD11b (Mac-1) in overweight recent-onset type 1 diabetic children. Rev Diabet Stud 2007; 4:112–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bouma G, Lam-Tse WK, Wierenga-Wolf AF, Drexhage HA, Versnel MA. Increased serum levels of MRP-8/14 in type 1 diabetes induce an increased expression of CD11b and an enhanced adhesion of circulating monocytes to fibronectin. Diabetes 2004; 53:1979–1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hearps AC, Maisa A, Cheng WJ, Angelovich TA, Lichtfuss GF, Palmer CS, et al. HIV infection induces age-related changes to monocytes and innate immune activation in young men that persist despite combination antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 2012; 26:843–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Puchta A, Naidoo A, Verschoor CP, Loukov D, Thevaranjan N, Mandur TS, et al. TNF drives monocyte dysfunction with age and results in impaired antipneumococcal immunity. PLoS Pathog 2016; 12:e1005368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Deeks SG, Lewin SR, Havlir DV. The end of AIDS: HIV infection as a chronic disease. Lancet 2013; 382:1525–1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sammicheli S, Kuka M, Di Lucia P, de Oya NJ, De Giovanni M, Fioravanti J, et al. Inflammatory monocytes hinder antiviral B cell responses. Sci Immunol 2016; 1:pii: eaah6789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moxon ER, Siegrist CA. The next decade of vaccines: societal and scientific challenges. Lancet 2011; 378:348–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hong HS, Ahmad F, Eberhard JM, Bhatnagar N, Bollmann BA, Keudel P, et al. Loss of CCR7 expression on CD56bright NK cells is associated with a CD56dimCD16+ NK cell-like phenotype and correlates with HIV viral load. PLos One 2012; 7:e44820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.