Abstract

Objectives

Young parents may be particularly vulnerable to poor mental health during the postpartum period. Little research exists, however, to adequately describe trajectories of depressive symptoms during their transition to parenthood, particularly among young fathers. Therefore, we aim to explore trajectories of depressive symptoms from pregnancy through 1 year postpartum among young expectant mothers and their partners.

Methods

Data are derived from a longitudinal cohort of pregnant adolescent females (ages 14–21; n = 220) and their male partners (n = 190). Multilevel regression models examined the impact of time on depressive symptoms, and generalized linear regression models examined predictors of experiencing elevated depressive symptoms.

Results

Depressive symptoms significantly decreased from pregnancy through 1 year postpartum among young females. Overall, depressive symptoms did not significantly change over time among young males. Predictors of elevated depressive symptoms common across genders included social support and relationship satisfaction. Marijuana use resulted in almost twice the odds of experiencing elevated depressive symptoms among young fathers (OR 1.82; 95 % CI 1.04, 3.20).

Conclusion for Practice

Providing strategies for strengthening social support networks among young parents may be an effective way to improve mental health among young parents, particularly during this period of potential social isolation. Additionally, providing tools to strengthen relationships between partners may also be effective for both young mothers and fathers. Substance use may be a marker for depressive symptoms among young fathers and thus screening for substance use could be important to improving their mental health. Future research is needed to better understand how IPV affects mental health, particularly among young fathers.

Keywords: Mental health, Depression, Parenthood, Adolescent father, Adolescent mother

Introduction

Postpartum depression affects up to 1 in 5 new mothers and has been associated with several negative outcomes, including impairment in daily functioning, relationship instability, less secure maternal-infant attachment, and worse child development and behavioral outcomes (Gavin et al. 2005; O’Hara and McCabe 2013).

Young mothers suffer from higher rates of postpartum depression than older mothers (Clare and Yeh 2012; Yozwiak 2010). Young parents are be particularly vulnerable because they often experience social isolation (Yozwiak 2010) as they integrate their role as a parent with other roles in life (e.g., daughters, students) (Letourneau et al. 2004). They also tend to have difficulty developing parental competence and confidence, especially when they may be reliant on their own parents for support (Birkeland et al. 2005). Additionally, compared with older parents, young parents are at greater risk for unhealthy coping behaviors, such as substance use and increased sexual activity (Crittenden et al. 2009), which lead to increased risk for sexually transmitted infections and rapid repeat pregnancies.

Additional research is needed to better understand and characterize young parents who are at risk for poor mental health outcomes. Among young mothers, findings consistently suggest that low social support and negative family relationships are associated with higher depressive symptomology (Birkeland et al. 2005; Logsdon et al. 2010; Reid and Meadows-Oliver 2007), but evidence on the effect of demographic characteristics often conflicts. For instance, age and current school status have had mixed findings, with studies reporting both null and significant associations between these characteristics and depressive symptoms (Barnet et al. 1996; Caldwell and Antonucci 1997; Kalil et al. 1998; Reid and Meadows-Oliver 2007). Furthermore, research on the effect of partner characteristics on mental health is limited and primarily focuses on the level of relational support provided to the young mother and the decreasing involvement of the father over time (Florsheim et al. 2003; Gee and Rhodes 1999; Roye and Balk 1996). Last, literature describing depressive symptoms among young fathers in the early postpartum period is scarce, and primarily suggests that young fathers may be more vulnerable to poor mental health than older fathers as is the case among young mothers (Heath et al. 1995; Lee et al. 2011). More recent research suggests an important vulnerability to poor mental health among young resident fathers (mean age of 26 years) during the postpartum period and up through his child’s fifth birthday (Garfield et al. 2014). This evidence also suggests that income, employment, race/ethnicity, marital status, and education may be important predictors of depressive symptoms over time (Garfield et al. 2014). Additional research is needed.

Accordingly, we aimed to describe mental health among young couples as they transition to parenthood. Specifically, we described trajectories of depressive symptoms among expectant mothers, ages 14–21, and their partners, ages 14 and older from pregnancy through 1 year postpartum. Additionally, we identified factors associated with elevated depressive symptoms during this period. We hypothesized that depressive symptoms would decline from pregnancy into the postpartum period among both mothers and fathers and that dyadic characteristics would be most important for understanding these patterns over time.

Methods

Sample

Data from this study were derived from a larger longitudinal cohort of young pregnant females and their partners, who were followed from pregnancy through 12 months postpartum. Couples were recruited between July 2007 and February 2011 from obstetrics and gynecology clinics and from an ultrasound clinic in four university-affiliated hospitals in Connecticut. Research staff screened potential participants for eligibility. Young women ages 14–21 who were in their second or third trimester of pregnancy and their partners (ages ≥ 14) were eligible to participate in the study. Further eligibility criteria included the following: both partners had to report being in a romantic relationship with one another at enrollment and report being the biological parents of the unborn baby, agree to participate in the study, and be able to speak English or Spanish. Additionally, neither partner could knowingly be HIV positive. If partners were not present, research staff provided informational materials to the female and asked her to discuss the study with him. Participants gave their informed consent prior to being included in the study. Of the 296 females and males who completed the baseline assessment during pregnancy, 226 females (76.4 %) and 206 males (69.6 %; 228 or 77.0 % of couples) participated in the second interview at approximately 6 months postpartum, and 261 females (88.2 %) and 239 males (80.7 %; 261 or 79.4 % of couples) participated in the third interview approximately 1 year postpartum. Our analytic sample was limited to participants with valid measures of depressive symptoms at all 3 assessments for a total sample size of 220 females and 190 males. Participants who were excluded were older, less likely to be Hispanic, more likely to be non-Hispanic white, and less likely to be in school than participants who were retained in the analysis (p values <0.05). There were no significant differences in depression scores between the two groups (p > 0.05).

Participants were interviewed separately during the third trimester of pregnancy (M = 29.1 weeks, SD = 5.27 weeks, range 17.6–42.4 weeks), at six months postpartum (M = 5.7 months, SD = 1.40 months, range 3–10 months), and at 1 year postpartum (M = 11.9 months, SD = 2.47, range 6–26 months). Participants completed an automated computerized self-interview (ACASI) simultaneously on two separate computers. Participation was voluntary, confidential, and did not influence the provision of health care or social services in any way. A total of 93 % of interviews were completed in English; 7 % were completed in Spanish. All procedures were approved by the Yale University Human Investigation Committee and by Institutional Review Boards at study clinics. Analysis of these data was approved by the University of Illinois at Chicago. Participants were paid $25 at each assessment.

Measures

Outcomes

Outcomes were self-reported at all time points, including pregnancy, 6 months, and 1 year postpartum.

Depression

Depressive symptoms were measured with the Center of Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) (Radloff 1977). Participants reported how often they felt or behaved in the specified way over the past week using a Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3, where 0 = ‘‘Rarely or none of the time (less than 1 day)’’, 1 = ‘‘Some or a little of the time (1–2 days)’’, 2 = ‘‘Occasionally or a moderate amount of time (3–4 days)’’, and 3 = ‘‘Most or all of the time (5–7 days).’’ Five of the 20 items were removed because they describe depressive symptoms that also may be symptoms of pregnancy and are thus deemed less reliable during pregnancy (Milan et al. 2007). The scale could therefore range between 0 and 45; higher scores indicated greater depressive symptomology; internal consistency for this measure was good (α = 0.83–0.85).

Exposures

We included actor and partner effects for several individual and dyadic characteristics based on prior literature on postpartum depression.

Individual

We used participant characteristics reported during pregnancy, including age (years), education (years of schooling), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic White and other), parity, and pregnancy wantedness. Parity was dichotomized for analysis to indicate if this baby was her/his first baby. Pregnancy wantedness, or the extent to which she/he wanted a baby, was measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘‘Definitely no’’ (0) to ‘‘Definitely yes’’ (4). At each time point (i.e., pregnancy, 6 months postpartum, and 12 months postpartum), we measured whether or not the participant was currently in school (yes vs. no) and whether or not they had any kind of medical insurance (yes vs. no). Social support was measured using 9 items adopted from the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (Sherbourne and Stewart 1991). Participants indicated how often others were available to them for companionship, assistance, and other forms of support; responses ranged on a 5-point scale from ‘‘None of the time’’ (0) to ‘‘All of the time’’ (4); thus, the total score could range between 0 and 36. Internal consistency was excellent (α = 0.95–0.97). Parental support of the pregnancy was measured during pregnancy by asking participants the following question: ‘‘In this current pregnancy, how supportive were your parents when they found out you were (she was) pregnant?’’ Possible responses ranged from ‘‘Not at all supportive’’ (1) to ‘‘Very supportive’’ (7). Last, we asked participants how often they used alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana during the past six months on a 5-point scale ranging from ‘‘Never’’ (0) to ‘‘Everyday’’ (4) (Halkitis and Parsons 2003).

Dyad

Dyadic characteristics were measured at each assessment. Participants were asked to describe their relationship with the father/mother of the baby, with responses ranging on a 4-point Likert scale from ‘‘Totally Non-Committed’’ (1) to ‘‘Very Committed’’ (4); responses were dichotomized for analysis into ‘‘very committed’’ vs. ‘‘less than very committed’’ based on frequency distributions. Living arrangements were assessed by participants indicating whether or not they lived with the father/mother of the baby (yes vs. no). Participants were also asked whether or not they had experienced intimate partner violence (IPV) from their partner, including any sexual violence, physical violence, threats or emotional abuse. IPV was assessed using an adapted version of the revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2) (Strauss et al. 1996). Participants were asked to respond yes or no to the following questions: ‘‘Have you ever been shoved, punched, hit, slapped, or physically hurt by [father/mother] of your baby?’’ ‘‘Has [father/mother] of your baby ever used force (hitting, holding down, using a weapon) to make you have sex (vaginal, oral, or anal sex) with him/her?’’ and ‘‘Has [father/mother] of your baby ever threatened to hurt you physically?’’ At baseline, if participants indicated ‘‘yes,’’ he/she was asked if it had occurred since becoming pregnant. Participants who indicated that any of the forms of violence had occurred since pregnancy were coded as having experienced IPV within their relationship with the father/-mother of the baby. Similar questions were asked at 6 and at 12 months postpartum. Relationship satisfaction was measured with the 32-item Dyadic Adjustment Scale (Spanier 1976), which was adapted to be more relevant to adolescent couples. For example, ‘‘Do you ever regret that you married (live together)?’’ was changed to ‘‘Do you ever regret being with your partner?’’ Participants responded to most items on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from ‘‘Never’’ (0) to ‘‘All the time’’ (5) or from ‘‘Always disagree’’ (0) to ‘‘Always agree’’ (5). Responses were summed for a total score; the scale ranged from 0 to 151. Higher scores indicated greater relationship satisfaction; reliability for this measure was excellent (α = 0.92–0.93). Last, family support of their relationship was assessed through 4 statements concerning reactions and attitudes toward their romantic relationship (e.g., ‘‘My family approves of my romantic relationship.’’). Participants responded to statements on a 6-point scale, ranging from ‘‘Strongly disagree’’ (1) to ‘‘Strongly agree’’ (6). Items were summed and ranged from 4 to 24 with higher scores indicating greater support of the relationship (Knobloch and Donovan-Kicken 2006); reliability for this measure was good (α = 0.83–0.85).

Data Analysis

We first generated means and frequencies to describe our sample at baseline. We then assessed the concordance between partners using correlation coefficients and Chi-square tests. Next, we described the trajectories of depressive symptoms at baseline, 6 months postpartum, and 1 year postpartum with mean values and t tests and constructed a multilevel linear regression model to test the effect of time on depressive symptoms. We used the upper-most quartile of scores (i.e., 75th percentile and higher) for the whole sample across all time points to represent elevated depressive symptoms, because there are no widely-accepted cut-points for the 15-item CES-D scale (5 somatic items removed). The 75th percentile was a score of 13 and thus, we chose 13 as our cut-point and dichotomized the CES-D score to indicate whether or not participants experienced elevated symptoms at each time point. We then used generalized linear regression to determine predictors of elevated symptoms across time using both actor and partner main effects and to determine if the trajectories over time differed by our predictors using predictor X time interactions. We first constructed unadjusted models, accounting for the effect of time, and then included all variables that were significant in the unadjusted analysis (p values <0.10) into a single multi-variate model. We then used backwards elimination to derive the most parsimonious model until all remaining variables were significant. We conducted a complete case analysis and used SPSS 21.0 (Chicago, IL) for all analyses.

Analyses were stratified by sex, because we hypothesized that young mothers and fathers experience the transition to parenthood differently from one another, specifically due to physical and biological differences between female and male partners. Additionally, we found that the male and female trajectories of depressive symptoms over time are significantly heterogeneous, thus suggesting the need for a stratified analysis.

Results

Sample Characteristics

On average, expectant mothers were 19 years old and expectant fathers were 21 years old at baseline (Table 1). Forty percent of females and 51 % of males were non-Hispanic black, and 42 % of females and 38 % of males were Hispanic. This pregnancy was the first for approximately three of every four participants, and half reported ‘‘kind of’’ or ‘‘definitely’’ wanting the pregnancy. Less than 5 % of females used alcohol or marijuana since the pregnancy began, and almost 14 % smoked cigarettes. Approximately half of the young males used alcohol (54.6 %) and smoked cigarettes (47.7 %). A total of 38 % used marijuana since the pregnancy began. Approximately 58 % of couples lived together, and 31 % of females and 48 % of males reported being a victim of IPV from his or her current partner. Most characteristics, such as age, education, pregnancy wantedness, and relationship satisfaction, were positively correlated, although social support, parental support of the pregnancy, and family support of the relationship were not significantly associated between partners. There were also differences between partners in frequencies of being in-school, race/ethnicity, medical insurance status, IPV victimization, and use of alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics at baseline by gender (n = 220 couples)

| n (%) |

Pearson correlation coefficienta | McNemar p valueb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | Males | |||

| Individual | ||||

| Age (years; M ± SD) | 18.7 ± 1.62 | 21.2 ± 3.67 | 0.556** | |

| Education (years; M ± SD) | 11.8 ± 1.91 | 11.9 ± 1.81 | 0.250** | |

| Currently in school | 97 (44.1) | 59 (26.8) | <0.001 | |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.004 | |||

| Non-Hispanic black | 87 (39.5) | 111 (50.5) | ||

| Hispanic | 93 (42.3) | 84 (38.2) | ||

| Non-Hispanic white/Other | 40 (18.2) | 25 (11.3) | ||

| Has medical insurance | 208 (94.5) | 137 (62.3) | <0.001 | |

| First child | 175 (79.9) | 162 (74.3) | 0.148 | |

| Wanted pregnancy (M ± SD) | 2.2 (1.39) | 2.4 (1.25) | 0.343** | |

| Social support (M ± SD) | 27.9 ± 7.69 | 25.2 ± 8.97 | 0.039 | |

| Parental support of pregnancy (M ± SD) | 5.8 ± 1.70 | 6.0 ± 1.50 | 0.053 | |

| Risk behaviors (during last 6 months) | ||||

| Any alcohol use | 9 (4.1) | 119 (54.6) | <0.001 | |

| Any smoking | 30 (13.6) | 104 (47.7) | <0.001 | |

| Any marijuana use | 9 (4.1) | 83 (38.1) | <0.001 | |

| Dyad | ||||

| Very committed relationship | 182 (82.7) | 170 (77.3) | 0.111 | |

| Lives with mother/father of the baby | 127 (57.7) | 128 (58.2) | 1.000 | |

| IPV from father/mother of the baby | 69 (31.4) | 105 (47.7) | <0.001 | |

| Relationship satisfaction (M ± SD) | 115.8 ± 19.93 | 114.1 ± 20.89 | 0.467** | |

| Family support of relationship (M ± SD) | 19.6 ± 4.64 | 19.5 ± 4.13 | 0.082 | |

| CES-D score | 10.7 ± 7.55 | 8.9 ± 6.73 | 0.223** | 0.008 |

| Elevated depressive symptoms (≥13) | 71 (32.3) | 48 (21.8) | ||

Missing values range from 0 to 10 among females and 0 to 12 among males

p value <0.01;

p value <0.05

Pearson correlation coefficient suggests the strength of the association between female and male measures; the p value suggests the probability that the magnitude of the association is equal to 0

McNemar’s Chi-square test p value indicates probability that the two proportions are equal to one another

Mean Depressive Symptoms Between Partners and Over Time

Young females reported significantly greater depressive symptomology (M = 10.7, SD = 7.55) than their male partners (M = 8.9, SD = 6.73) during pregnancy (paired t test p value = 0.002). Scores between female and male partners were not significantly different at 6 months postpartum (M = 9.1, SD = 7.77 and M = 9.3, SD = 6.98, respectively; paired t test p value = 0.799). At 12 months postpartum, young females reported less depressive symptomology (M = 8.9, SD = 7.43) than males (M = 9.6, SD = 7.44), but this difference was not significant (p value = 0.275).

Generalized linear models suggested significant effect modification by gender (B = 1.40, SE = 0.44, p < 0.01). Depressive symptoms significantly decreased from pregnancy through 12 months postpartum among females (B = −0.92, SE = 0.30, p = 0.003; Fig. 1). And although depressive symptoms increased among males from pregnancy through 12 months postpartum, this trend was non-significant (B = 0.47, SE = 0.31, p = 0.132). No curvilinear effects of time were found.

Fig. 1.

Mean CES-D scores among young females and their male partners through their transition to parenthood (n = 220 couples)

Elevated Depressive Symptoms Between Partners

Approximately one-third (32.3 %) of young females and one-fifth (21.8 %) of their male partners were experiencing elevated depressive symptoms during pregnancy (Table 1). Compared with during pregnancy, fewer young females (24.5 %) and more young males (27.9 %) were experiencing elevated depressive symptoms at 6 months post partum. Frequencies remained relatively stable from 6 to 12 months postpartum with 27.3 % of young females and 25.7 % of their partners experiencing elevated depressive symptoms.

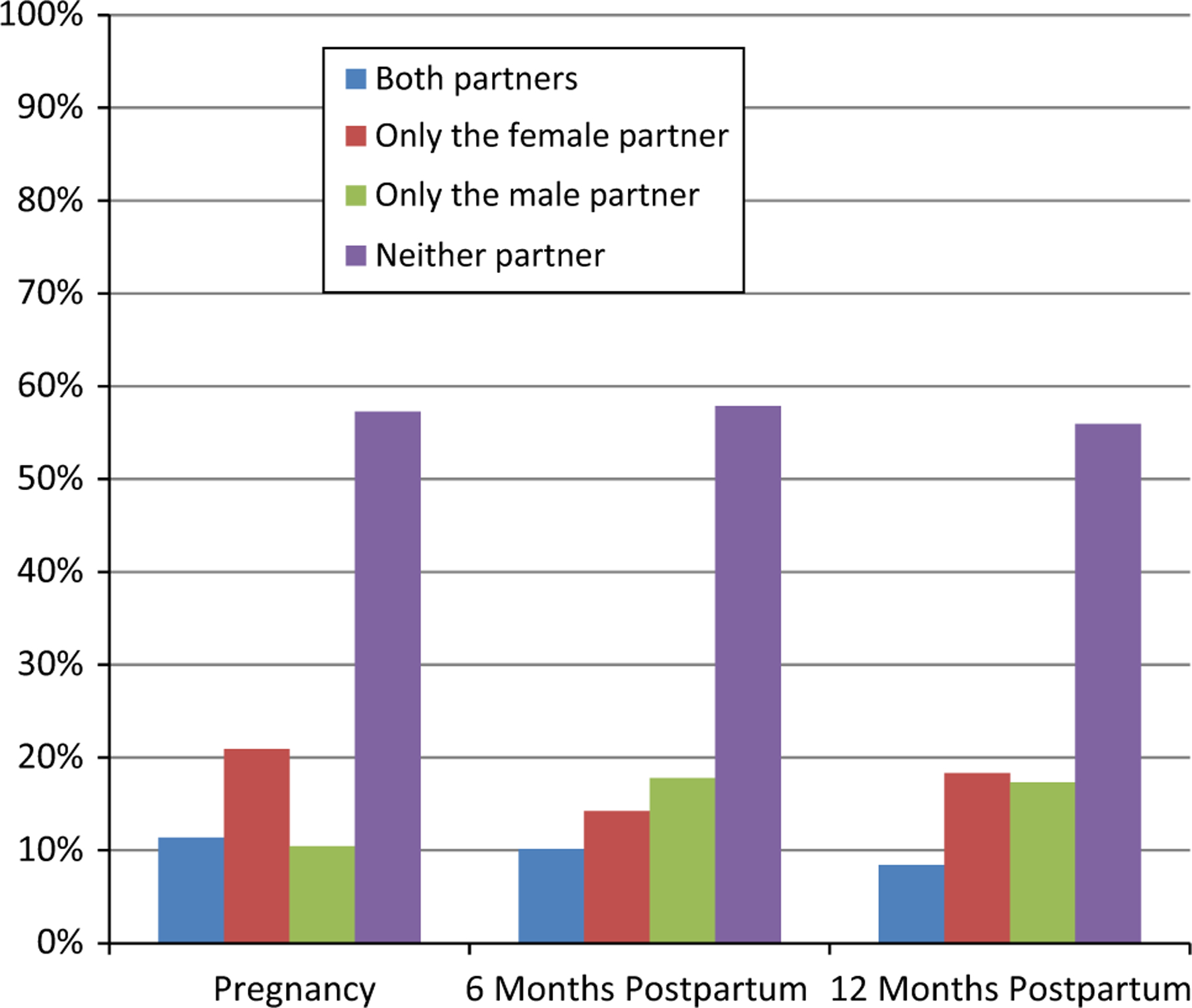

McNemar Chi-square tests suggested differences in the proportion of partners experiencing elevated depressive symptoms during pregnancy (p value = 0.008), with young females having a greater likelihood than their male partners of experiencing elevated depressive symptoms, but no differences at 6 and 12 months postpartum (p values = 0.450 and 0.906, respectively). Concordance of elevated depressive symptoms among couples at each time point is shown in Fig. 2. For instance, during pregnancy, neither partner had elevated depressive symptoms in 126 couples (57.3 %); the female partner had elevated symptoms, but the male partner did not in 46 couples (20.9 %); the male partner had elevated symptoms, but the female partner did not in 23 couples (10.5 %); and both partners had elevated depressive symptoms in 25 couples (11.4 %). The proportion of couples in which only the male was experiencing elevated depressive symptoms slightly increased from pregnancy to the postpartum period, but the proportion of couples in which only the female was experiencing elevated depressive symptoms slightly decreased over this same period.

Fig. 2.

Young couples experience of elevated depressive symptoms during the transition to parenthood (n = 220 couples). Elevated depressive symptoms was considered to be a score of 13 or higher on the modified (15-item) CES-D

Predictors of Elevated Depressive Symptoms Over Time

Among young females, after adjusting for other factors, the odds of experiencing elevated depressive symptoms decreased over time from pregnancy through the first postpartum year (OR 0.70; 95 % CI 0.55, 0.89; Table 2). Being older and having more social support were both associated with significantly lower odds of elevated depressive symptoms (OR 0.74; 95 % CI 0.64, 0.86 and OR 0.95; 95 % CI 0.93, 0.97; respectively). Additionally, each unit increase in her relationship satisfaction and her partner’s relationship satisfaction was predictive of lower odds of elevated depressive symptoms (OR 0.97; 95 % CI 0.96, 0.98 and OR 0.99; 95 % CI 0.98, 1.00; respectively).

Table 2.

Generalized linear regression models predicting elevated depressive symptoms (≥13 on modified CES-D) over time among partners from pregnancy through 1 year postpartum

| OR (95 % CI) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Females (n = 220) | Males (n = 189) | |

| Main effectsa | ||

| Time | 0.70 (0.55, 0.89)** | 0.96 (0.74, 1.26) |

| Individual | ||

| Age at baseline (actor) | 0.74 (0.64, 0.86)** | |

| Social support (actor) | 0.95 (0.93, 0.97)** | 0.97 (0.95, 1.00)* |

| Any marijuana use (past 3 months; actor) | 1.82 (1.04, 3.20)* | |

| Dyad | ||

| Relationship satisfaction (actor) | 0.97 (0.96, 0.98)** | 0.98 (0.96, 0.99)** |

| Relationship satisfaction (partner) | 0.99 (0.98, 1.00)* | |

| Family support of relationship (actor) | 0.92 (0.87, 0.97)** | |

| Family support of relationship (partner) | 0.93 (0.88, 0.98)* | |

| Effects over timeb | ||

| Individual | ||

| Any cigarette use (past 3 months; actor) | 0.50 (0.27, 0.90)* | |

| Dyad | ||

| IPV from father/mother of the baby (actor) | 0.56 (0.31, 1.00)* | 0.49 (0.25, 0.94)* |

| Elevated depressive symptoms (partner) | 0.40 (0.23, 0.69)** | |

p value <0.01;

p value <0.05

The main effects model for young females includes time, age, social support, and relationship satisfaction for both her and her partner. The main effects model for young males includes time, social support, marijuana use, relationship satisfaction, his and his partner’s family support of the relationship

The effects over time (e.g., IPV*time and partner depressive symptoms*time for females) were modeled independent of one another by including the interaction term with its main effect (e.g., IPV and partner depressive symptoms, respectively, for females) into the corresponding main effect model presented above

Results also suggest that the effects of particular factors, namely IPV and partner’s elevated depressive symptoms, modify the trajectory of depressive symptoms among young females (OR 0.56; 95 % CI 0.31, 1.00 and OR 0.40; 95 % CI 0.23, 0.69; respectively). Specifically, female participants’ odds of experiencing elevated depressive symptoms decreased over time if they experienced IPV (OR 0.47; 95 % CI 0.29, 0.76) or if they had a partner with elevated depressive symptoms (OR 0.35; 95 % CI 0.22, 0.56); there were no significant changes over time if they had not experienced IPV (OR 0.84; 95 % CI 0.62, 1.14) or if they did not have a partner with elevated depressive symptoms (OR 0.88; 95 % CI 0.67, 1.16).

Among young males, after adjusting for other factors, time did not have a significant effect on the experience of elevated depressive symptoms (OR 0.96; 95 % CI 0.74, 1.26). Social support reduced the odds of experiencing elevated depressive symptoms (OR 0.97; 95 % CI 0.95, 1.00), but marijuana use was associated with significantly higher odds of experiencing depressive symptoms (OR 1.82; 95 % CI 1.04, 3.20). Higher relationship satisfaction was associated with lower odds of elevated depressive symptoms (OR 0.98; 95 % CI 0.96, 0.99) as was his family’s support of the relationship (OR 0.92; 95 % CI 0.87, 0.97) and his partner’s family’s support of the relationship (OR 0.93; 95 % CI 0.88, 0.98).

Results also suggest that cigarette use and experience of IPV modify the trajectory of depressive symptoms over time among young males (OR 0.50; 95 % CI 0.27, 0.90 and OR 0.49; 95 % CI 0.25, 0.94; respectively). Specifically, the odds of experiencing elevated depressive symptoms decreased over time if they smoked cigarettes (OR 0.57; 95 % CI 0.35, 0.94) or if they had experienced IPV (OR 0.63; 95 % CI 0.39, 1.02); and there were modest increases over time if they did not smoke cigarettes (OR 1.15; 95 % CI 0.84, 1.60) or did not experience IPV (OR 1.30; 95 % CI 0.87, 1.94), but these effects were not statistically significant.

Discussion

Young expectant mothers demonstrated significantly greater depressive symptomology than their partners during pregnancy, but symptoms decreased over time into the postpartum period, corroborating the pattern found among adult women (Heron et al. 2004). It is not clear, however, how depressive symptomology may have fluctuated within the first 6 months postpartum and thus, this period warrants additional research as it is critical for developing maternal-infant attachment and establishing healthy behaviors, such as breastfeeding. Results also suggest that younger age increases vulnerability to depressive symptoms, which corroborates some but not all research on this association (Barnet et al. 1996; Caldwell and Antonucci 1997; Kalil et al. 1998; Reid and Meadows-Oliver 2007).

Overall, after accounting for other potential confounders, young males experienced no significant changes in depressive symptomology over time. With the exception of one other study (Areias et al. 1996), most longitudinal research among adult fathers suggests that depressive symptoms decrease from pregnancy to the postpartum period (Condon et al. 2004; Matthey et al. 2000; Ramchandani et al. 2008). Our results may differ because young fathers may have been less likely to have planned for the pregnancy and for providing appropriate support throughout the first year (Schumacher et al. 2008), increasing stress and thus creating a null effect on depressive symptoms over time. Increased stress may also result from the natural transition from adolescence to adulthood, during which time young fathers may have taken on additional responsibilities to care for his growing family. The patterns seen in our unadjusted analyses, however, mirror recent work by Garfield et al. (2014), which suggests that depressive symptoms among young fathers may increase during the postpartum period. Future research is needed to continue exploring trajectories of depressive symptoms among young fathers.

Elevated depressive symptomology was significantly associated with social support and relationship satisfaction among both young females and males, findings that are generally consistent with research conducted among adult parents (Matthey et al. 2000; Wee et al. 2011; Yim et al. 2015). These characteristics may be particularly important as adolescent parents, mothers in particular, tend to experience social isolation as they try to re-integrate into their peer groups (Yozwiak 2010). Interventions to enhance support networks and relationships between partners (whether or not they are still romantically involved) may therefore effectively improve mental health of young parents. Researchers may think creatively about enhancing social support among young parents, particularly through social media and other web-based or cellular phone-based applications since the overwhelming majority of adolescents today have access to smart phones and are texting with enormous frequency (PewResearchCenter 2012).

Depressive symptoms among young females also appear to be influenced by her partner’s relationship satisfaction. This finding may suggest that she tends to seek affirmation in her partner during this time of significant physical changes and role transitions. Interestingly, young males appear to be affected instead by his and his partner’s family’s support of the relationship, thus looking for affirmation external to the couple.

Both young mothers and fathers who experienced IPV from their partners experienced a decrease in depressive symptomology during the transition to parenthood. This finding may suggest that addition of the baby lessens the impact of discord within the parents’ relationship and somehow mutes its effects. Possibly, during this transition to parenthood, young mothers and fathers sense additional worth beyond what is attributed to them by their partner, reducing the impact of IPV. This finding, however, does not negate the urgent need to reduce the frequency with which IPV appears to be occurring within these young couples and deserves additional attention from researchers and health care providers. It is important for future research to understand the extent to which IPV is occurring with respect not only to its frequency but also its impact on both the victim and perpetrator.

Similarly, the new baby may also lessen the potential detrimental effects of the male partner’s depression on the new mother. This idea is consistent with the hypothesis young mothers may be looking moreso to their relationship for affirmation than their families’ support of the relationship, but also that her sense of self-worth may also be coming from her new role as a mother. Future work should aim to empower and promote competency among new mothers, focusing on demonstrating the unique value of the young mother—and father—for the new child.

Depressive symptoms among young fathers appear closely related to substance use, such as smoking and marijuana use, and thus, substance use may be a marker for poor mental health among young males as they transition to fatherhood. This finding is consistent with research that suggests young males may be more susceptible to adverse coping strategies such as violence, substance abuse, and other risk-taking behaviors than young females (Byrnes et al. 1999). These poor coping strategies can compound conflict and worsen a disadvantaged context. Due to the high frequencies of substance use observed among this sample of young males, it is possible that screening for marijuana use in particular among young fathers may be an important step to understanding his mental health.

There are several study limitations worth considering, including the self-reported nature of the data. Depressive symptomology, in particular, may have been underreported due to social desirability bias; this tendency to underreport may have affected males to a greater extent than females. This effect, however, suggests that results may be biased downward or towards the null. Furthermore, the cut-point we used to assess elevated depressive symptoms was artificial, based on the upper-most quartile of overall scores. This score, however, is slightly higher than what would be expected (Gee and Rhodes 1999) if we based on our cut-point on the one commonly used for the overall 20-item scale (Kalil et al. 1998), which implies 0.8 points per item. Therefore, our cut-point of 13 may underestimate the prevalence of young mothers and fathers at risk for depression. Second, attrition may have also affected our results; however, there were no significant differences in depressive symptoms between our participants who were included in and excluded from our analysis. Third, because our results are derived from couples engaged in health care systems in predominantly urban settings, these results may not be generalizable to a broader population of adolescent parents. In fact, pregnant adolescents who received no prenatal care are at highest risk for poor outcomes and would have been excluded by our recruitment strategy. It is possible therefore that our prevalence data underestimates the prevalence of depressive symptoms in a broader population. Factors associated with these patterns over time also may differ. Last, we did not ask participants about prior depressive symptoms, which may have been the strongest predictor of future depressive symptoms and may have explained variation that we attributed to other characteristics by our modeling.

This study, however, has many strengths, including the use of a prospective cohort of adolescent couples as they transition to parenthood. These results are among the first to describe depressive symptoms among young fathers during pregnancy and through the first year postpartum and partner effects on both young mothers’ and fathers’ depressive symptoms. Results can inform the development of interventions for improving mental health among young couples transitioning into parenthood. Text-based interventions may be highly effective for this particular population and should be considered for future work, as there is preliminary evidence that they can effectively increase knowledge and reduce sexually risky behaviors (Jones et al. 2014) as well as promote healthy behaviors (Militello et al. 2012). Improving the mental health of young parents is a critical step for ensuring the overall health of young families.

Supplementary Material

Significance.

Poor postpartum mental health can have important adverse effects on parents and the new baby. Young parents may be particularly vulnerable to depression and are at greater risk for unhealthy coping behaviors.

Depressive symptoms decreased from pregnancy through 1 year postpartum among young females, but did not change over time among young males. Higher relationship satisfaction and social support were associated with fewer depressive symptoms among both genders. Providing strategies for strengthening social support networks and relationships among young parents may effectively improve mental health. Furthermore, substance use may be a marker for depressive symptoms among young fathers, and thus, screening may be warranted.

Acknowledgments

Supported by a Grant from the National Institutes of Mental Health (1R01MH75685).

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Areias M, Kumar R, Barros H, & Figueiredo E (1996). Comparative incidence of depression in women and men, during pregnancy and after childbirth. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in Portuguese mothers. British Journal of Psychiatry, 169(1), 30–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnet B, Joffe A, Duggan A, Wilson M, & Repke J (1996). Depressive symptoms, stress, and social support in pregnant and postpartum adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 150, 64–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkeland R, Thompson J, & Phares V (2005). Adolescent motherhood and postpartum depression. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 34(2), 292–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrnes J, Miller D, & Schafer W (1999). Gender differences in risk taking: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 125(3), 367–383. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell C, & Antonucci T (1997). Perceptions of parental support and depressive symptomatology among black and white adolescent mothers. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 5, 173–183. [Google Scholar]

- Clare C, & Yeh J (2012). Postpartum depression in special populations: A review. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey, 67(5), 313–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condon J, Boyce P, & Corkindale C (2004). The First-Time Fathers Study: A prospective study of the mental health and wellbeing of men during the transition to parenthood. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 38(1–2), 56–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden C, Boris N, Rice J, Taylor C, & Olds D (2009). The role of mental health factors, behavioral factors, and past experiences in the prediction of rapid repeat pregnancy in adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health, 44, 25–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florsheim P, Sumida E, McCann C, Winstanley M, Fukui R, Seefeldt T, et al. (2003). The transition to parenthood among young African American and Latino couples: Relational predictors of risk for parental dysfunction. Journal of Family Psychology, 17(1), 65–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfield C, Duncan G, Rutsohn J, Dade T, Adam E, Coley R, et al. (2014). A longitudinal study of paternal mental health during transition to fatherhood as young adults. Pediatrics, 133(5), 836–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin N, Gaynes B, Lohr K, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, & Swinson T (2005). Perinatal depression: A systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 106(5, Part 1), 1071–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee C, & Rhodes J (1999). Postpartum transitions in adolescent mothers’ romantic and maternal relationships. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 45(3), 512–532. [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis P, & Parsons J (2003). Recreational drug use and HIV-risk sexual behavior among men frequenting gay social venues. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 14(4), 19–38. [Google Scholar]

- Heath D, Mckenry P, & Leigh G (1995). The consequences of adolescent parenthood on men’s depression, parental satisfaction, and fertility in adulthood. Journal of Social Service Research, 20(3–4), 127–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron J, O’Connor T, Evans J, Golding J, & Glover V (2004). The course of anxiety and depression through pregnancy and the postpartum in a community sample. Journal of Affective Disorders, 80(1), 65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones K, Eathington P, Baldwin K, & Sipsma H (2014). The impact of health education transmitted via social media or text messaging on adolescent and young adult risky sexual behavior: A systematic review of the literature. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 41(7), 413–419. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalil A, Spencer M, Spieker S, & Gilchrist L (1998). Effects of grandmother coresidence and quality of family relationships on depressive symptoms in adolescent mothers. Family Relations, 47, 433–441. [Google Scholar]

- Knobloch L, & Donovan-Kicken E (2006). Perceived involvement of network members in courtships: A test of the relational turbulence model. Personal Relationships, 13(3), 281–302. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Fagan J, & Chen W (2011). Do late adolescent fathers have more depressive symptoms than older fathers? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41(10), 1366–1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letourneau N, Stewart M, & Barnfather A (2004). Adolescent mothers: Support needs, resources, and support-education interventions. Journal of Adolescent Health, 35, 509–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logsdon M, Foltz M, Stein B, Usui W, & Josephson A (2010). Adapting and testing telephone-based depression care management intervention for adolescent mothers. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 13, 307–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthey S, Barnett B, Ungerer J, & Waters B (2000). Paternal and maternal depressed mood during the transition to parenthood. Journal of Affective Disorders, 60(2), 75–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milan S, Kershaw T, Lewis J, Westdahl C, Rising S, Patrikios M, et al. (2007). Caregiving history and prenatal depressive symptoms in low-income adolescent and young adult women: Moderating and mediating effects. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31, 241–251. [Google Scholar]

- Militello L, Kelly S, & Melnyk B (2012). Systematic review of text-messaging interventions to promote healthy behaviors in pediatric and adolescent populations: implications for clinical practice and research. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 9(2), 66–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara M, & McCabe J (2013). Postpartum depression: Current status and future directions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9, 379–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PewResearchCenter. (2012). Texting is nearly universal among young adult cell phone owners Retrieved June 3, 2013. From http://www.pewresearch.org/daily-number/texting-is-nearly-universal-among-young-adult-cell-phone-owners/.

- Radloff L (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Ramchandani P, Stein A, O’Connor T, Heron J, Murray L, & Evans J (2008). Depression in men in the postnatal period and later child psychopathology: A population cohort study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(4), 390–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid V, & Meadows-Oliver M (2007). Postpartum depression in adolescent mothers: An integrative review of the literature. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 21, 289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roye C, & Balk S (1996). The relationship of partner support to outcomes for teenage mothers and their children: A review. Journal of Adolescent Health, 19, 86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher M, Zubaran C, & White G (2008). Bringing birth-related paternal depression to the fore. Women and Birth: Journal of the Australian College of Midwives, 21(2), 65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne C, & Stewart A (1991). The MOS social support survey. Social Science and Medicine, 32, 713–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanier G (1976). Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scale for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage & the Family, 38, 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss M, Hamby S, Boney-McCoy S, & Sugarman D (1996). The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues, 17(3), 283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Wee K, Skouteris H, Pier C, Richardson B, & Milgrom J (2011). Correlates of ante- and postnatal depression in fathers: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 130(3), 358–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yim I, Tanner Stapleton L, Guardino C, Hahn-Holbrook J, & Dunkel Schetter C (2015). Biological and psychosocial predictors of postpartum depression: Systematic review and call for integration. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 11, 99–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yozwiak J (2010). Postpartum depression and adolescent mothers: A review of assessment and treatment approaches. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 23, 172–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.