Abstract

Neurotensin is a 13 amino acid peptide which is present in many lung cancer cell lines. Neurotensin binds with high affinity to the neurotensin receptor 1, and functions as an autocrine growth factor in lung cancer cells. Neurotensin increases tyrosine phosphorylation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and the neurotensin receptor 1 antagonist SR48692 blocks the transactivation of the EGFR. Here the effects of reactive oxygen species on the transactivation of the EGFR and HER2 were investigated. Using non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines, neurotensin receptor 1 mRNA and protein were present. Using NCI-H838 cells, neurotensin or neurotensin8–13 but not neurotensin1–8 increased EGFR, ERK and HER2 tyrosine phosphorylation which was blocked by SR48692. Neurotensin addition to NCI-H838 cells increased significantly reactive oxygen species which was inhibited by SR48692, Tiron (superoxide scavenger) and diphenylene iodonium (DPI inhibits the ability of NADPH oxidase and dual oxidase enzymes to produce reactive oxygen species). Tiron or DPI impaired the ability of neurotensin to increase EGFR, ERK and HER2 tyrosine phosphorylation. Neurotensin stimulated NSCLC cellular proliferation whereas the growth was inhibited by SR48692, DPI or lapatinib (lapatinib is tyrosine kinase inhibitor of the EGFR and HER2). Lapatinib inhibited the ability of the neurotensin receptor 1 to transactivate the EGFR and HER2. The results indicate that neurotensin receptor 1 regulates the transactivation of the EGFR and HER2 in a reactive oxygen species-dependent manner.

Keywords: reactive oxygen species, neurotensin, EGFR, HER2, lung cancer

1. Introduction

Neurotensin is present in many lung cancer cell lines (Wood et al., 1980; Moody et al., 1985). It is derived from a 170 amino acid precursor protein and metabolized to a 13 amino acid peptide which is biologically active (Carraway and Leeman, 1973; Kitabgi et al., 2010). Neurotensin binds to the G protein-coupled receptors neurotensin receptor 1 and neurotensin receptor 2 (Chaolin et al., 1996; Betancur et al., 1998). The 418 amino acid neurotensin receptor 1 is antagonized by the small molecule SR48692 (Moody et al., 2001). Also, neurotensin binds to the neurotensin receptor 3 which is not a G protein-coupled receptor but is sortilin (Wilson et al., 2014). Radiolabeled neurotensin binds with high affinity to lung cancer cells (Allen et al., 1988). Neurotensin8–13 localizes to the top of the binding pocket and interacts with neurotensin receptor 1 transmembrane domains 6 and 7 as well as extracellular loops 2 and 3 (White et al., 2012). In contrast, SR48692 binds deep into the neurotensin receptor 1 binding pocket and antagonizes the effects of neurotensin.

The neurotensin receptor 1 interacts with Gq11 causing metabolism of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate to diacylglycerol, which activates protein kinase (PK) C, and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate, which causes elevation of cytosolic calcium (Ca2+). Neurotensin activates Rho GTPases, NFκB, focal adhesion kinase and extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK) (Leyton et al., 2002). The phosphorylated ERK alters the gene expression of c-fos and c-jun (Kisfalvi et al., 2012). Neurotensin addition to lung cancer cells causes rapid tyrosine phosphorylation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells (Moody et al., 2014). Similarly, neurotensin receptor 1 regulates transactivation of the EGFR in colon, foregut neuroendocrine, and prostate cancer cells (Muller et al. 2001; Hassan et al 2004; Zhou et al 2015; Di Florio et al 2013). The Wnt signaling pathway causes increased expression of E-cadherin leading to epithelial to mesenchymal transitions and cancer metastasis (Ye et al., 2016). Neurotensin stimulates the growth of numerous cancers whereas SR48692 inhibits proliferation (Evers, 2006; Moody et al., 2014).

Neurotensin receptor 1 is present in several cancers including Ewing’s sarcoma and medullary thyroid cancers (Reubi et al., 1999). Neurotensin and neurotensin receptor 1 immunoreactivity are present in approximately 60% of the lung adenocarcinoma biopsy specimens and patients with high neurotensin receptor 1 levels have significantly lower relapse-free survival than those with low neurotensin receptor 1 levels (Alifano et al., 2010). Neurotensin and neurotensin receptor 1 are expressed in approximately 70% of the NSCLC cell lines examined (Ocejo-Garcia et al., 2001). Neurotensin addition to NSCLC cell lines increased EGFR tyrosine phosphorylation which was reduced by SR48692, Neurotensin receptor 1 siRNA, gefitinib (EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor) and Tiron (reduces reactive oxygen species; Moody et al., 2014)). Little is known about the ability of neurotensin to transactivate receptor tyrosine kinases other than the EGFR. In this communication the ability of neurotensin receptor 1 to regulate transactivation of the EGFR and HER2 was investigated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell culture

NSCLC cells (NCI-H157, H322, H358, H441, H460, H520, H661, H838, H1299 as well as A549) (ATCC, Manassas VA), which are adherent, were cultured in RPMI-1640 containing 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin/streptomycin (GIBCO, Gaithersburg, MD). When the cells became confluent, the old media was removed, and the confluent cells washed in PBS. After removal of the PBS, the cells treated with 0.25% trypsin/EDTA. Routinely the cells were split 1:20 and cultured in a new T175 flask. For the Western blot experiments, cells were cultured in 10 cm dishes. For the receptor binding experiments, NSCLC cells were cultured in 24 well plates. For the MTT and reactive oxygen species experiments cells were cultured in 96 well plates.

2.2. Receptor binding

When NCI-H838 cells were confluent in the 24 well plates, they were washed 3 times in SIT (RPMI-1640 containing 5 μg/ml bovine insulin, 10 μg/ml apotransferrin and 5 × 10−8M sodium selenite (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) medium. The cells were incubated with receptor binding buffer (0.1% bovine serum albumin with 0.01% bacitracin in PBS). Varying concentrations of ligands were added to the receptor binding buffer followed by 100,000 cpm of (125I-Tyr3) neurotensin. After 30 min at 37°C, the plates were rinsed 3x with receptor binding buffer. The cells were dissolved in 0.2 N NaOH and counted in a LKB gamma counter.

2.3. RT-PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from 10 human NSCLC cell lines using a RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). RNA samples were treated with DNase Digestion (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) to remove contaminating DNA and total RNA (1 μg) was reverse transcribed using a SuperScriptTMIII First-Strand Synthesis SuperMix for qRT-PCR (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions for complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis. PCR amplification for the neurotensin receptor 1 and neurotensin receptor 2 were performed using the HotStarTaq® Master Mix Kit. The primer strands for the neurotensin receptor 1 were forward (ATCAACCCCATCCTGTACAACC) and reverse (GGGCTGCTCTGTCTGTCG) with a product size of 254 bp. The primer strands for the neurotensin receptor 2 were forward (ACGGCTTCCAGGAAGAGTTTT) and reverse (CTTCGTCATGCAGCCCTCT) with a product size of 232 bp. Amplification conditions for the PCR reactions included an initial cycle of 95°C for 15 min, followed by a 35-cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 62°C for 30 s and extension at 72°C for 1 min. After the final cycle, all PCR reactions were concluded with a 10 min extension at 72°C. The PCR products were analyzed on a 3% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. Both sets of primers were positive for control cell lines containing neurotensin receptor 1 or neurotensin receptor 2.

2.4. Western blot.

When NCI-H838 cells became confluent in 10 cm dishes, they were treated with SIT media for 3 h. Inhibitors were added 30 min prior to the experiment. NTS ligands (100 nM) were added to the plates and after 2 min, the plates were rinsed twice with PBS and treated with 0.5 ml of lysis buffer (TBS containing 1% Triton, 1% Deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, 0.4 mM EGFR and 0.1% sodium azide (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The lysate was sonicated for 5 sec at 4°C and the samples centrifuged at 10,000 x g for 5 min. The protein concentration was determined using the BCA reagent (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). Routinely 40 μg of protein extract was loaded onto a 15 well 4–20% polyacrylamide gel (Invitrogen, Frederick, MD). After transfer to nitrocellulose (Biorad, Hercules, CA), the blot was probed with anti EGFR, anti-PY1068 EGFR, anti-HER2, anti PY1248HER2, anti-ERK, anti PY204ERK or anti-tubulin (Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA). The blots were rinsed twice with TBS containing 5% non-fat dry milk (LabScientific, Highlands, NJ), twice with TBS and treated with anti-rabbit IgG HRP-linked Ab (Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA) for 60 min. After drying the blot, it was treated with SuperSignal West Dura extended substrate (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) for 4 min. The blot was dried and analyzed on a Syngene G-box Chemi XXG densitometer (Image Technologies, Alexandria, VA).

2.5. Reactive oxygen species.

NCI-H838 cells were cultured in black 96 well plates (30,000 cells/well). When the cells were confluent they were treated with 10 μM dichlorofluorescein diacetate for 1 h and washed 3 times with serum-free SIT medium. Some of the cells were treated with Tiron, DPI or SR48692 for 30 min. Stimulation was carried out by the addition of 100 nM neurotensin or 10 μM H2O2. Fluorescence measurements were taken from 0–60 min using an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and emission wavelength of 585 nm.

2.6. Proliferation.

Growth studies in vitro were conducted using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2.5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and clonogenic assays. In the MTT assay, NCI-H838 cells were placed in SIT medium and various concentrations of lapatinib or SR4892 added (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). After 2 days, 15 μl of 0.1 % MTT solution added. After 4 h, 150 μl of dimethylsulfoxide was added and the optical density at 570 nm was determined. In the clonogenic assay, the effects of neurotensin, SR48692, DPI or lapatinib were investigated on NCI-H838 cells. The bottom layer contained 0.5% agarose in SIT medium containing 5% FBS in 6 well plates. The top layer consisted of 3 ml of SIT medium in 0.3% agarose, neurotensin, SR48692 and/or lapatinib using 5 × 104 lung cancer cells. Triplicate wells were plated and after 2 weeks, 1 ml of 0.1% p-iodonitrotetrazolium violet was added and after 16 h at 37°C, the plates were screened for colony formation; the number of colonies larger than 50 μm in diameter were counted using an Omnicon image analysis system.

2.7. Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as means ± S.D. Statistical significance of differences was performed by one-way or two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). The combination index was calculated according to Chou and Talalay (1984).

3. Results

3.1. Neurotensin receptor 1 is present in NSCLC cells.

The effects of neurotensin on NSCLC cells were initially evaluated using receptor binding techniques. Table I shows that neurotensin or neurotensin8–13, but not neurotensin1–8, inhibited specific binding of (125I-Tyr3) neurotensin to NCI-H838 cells with IC50 values of 2, 3 and >2000 nM, respectively. SR48692 (neurotensin receptor 1 antagonist) inhibited specific (125I-Tyr3) neurotensin binding with an IC50 value of 160 nM whereas levocabastine (neurotensin receptor 2 agonist), gefitinib or lapatinib had little effect. Similar results using NCI-H1299 or A549 cells (Moody et al., 2014). The results suggest that neurotensin receptor 1 is present in NSCLC cells.

Table I.

Binding of NTS analogs.

| Drug | IC50, nM |

|---|---|

| Neurotensin (NTS) | 2 ± 0.4 |

| NTS8–13 | 3 ± 1 |

| NTS1–8 | > 2000 |

| SR48692 | 160 ± 25 |

| Gefitinib | > 2000 |

| Lapatinib | >2000 |

| Levocabastine | > 2000 |

The IC50 to inhibit specific (125I-Tyr3) NTS is indicated. The mean value ± S.D. of 3 determinations each repeated in duplicate is indicated. The sequence of NTS is: pGlu-Leu-Tyr-Glu-Asn-Lys-Pro-Arg-Arg-Pro-Tyr-Ile-Leu

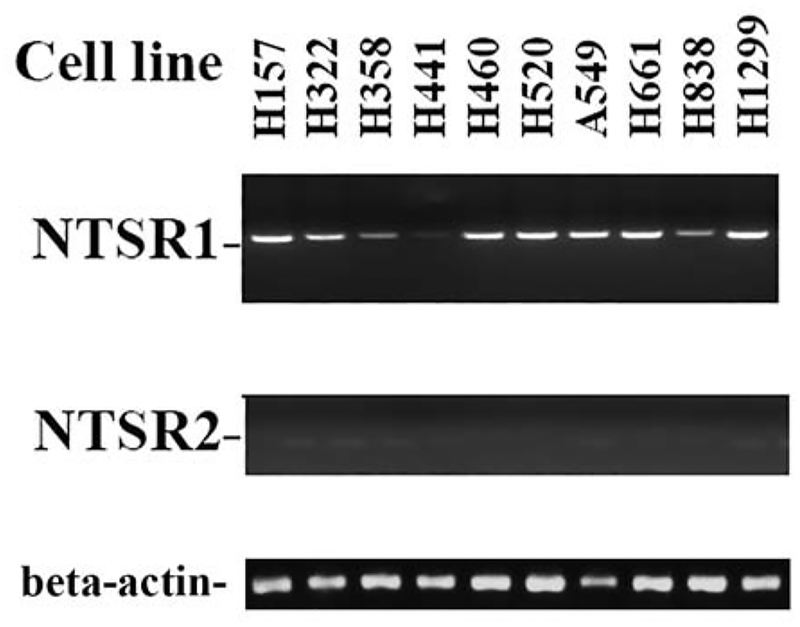

Neurotensin receptor 1 and 2 mRNA was investigated in 10 NSCLC cell lines. Fig. 1 shows that high levels of neurotensin receptor 1 mRNA were present in NCI-H157, H322, H460, H520, A549, H661 and H1299 cells. Moderate levels on neurotensin receptor 1 were detected in NCI-H358 and H838 cells. Low levels of neurotensin receptor 1 mRNA were present in NCI-H441 cells. Neurotensin receptor 2 mRNA was not present in the NSCLC cell lines examined. A loading control indicates that equal amounts of β-actin were loaded onto the gel. The results indicate that neurotensin receptor 1 but not neurotensin receptor 2 mRNA is present in NSCLC cells.

Fig. 1.

RT-PCR. RNA was isolated from pellets of 10 lung cancer cells and cDNA prepared. RT-PCR was performed as described in the methods for neurotensin receptor 1, neurotensin receptor 2 or β-actin. The PCR products analyzed on a 3% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. The experiment is representative of 2 others.

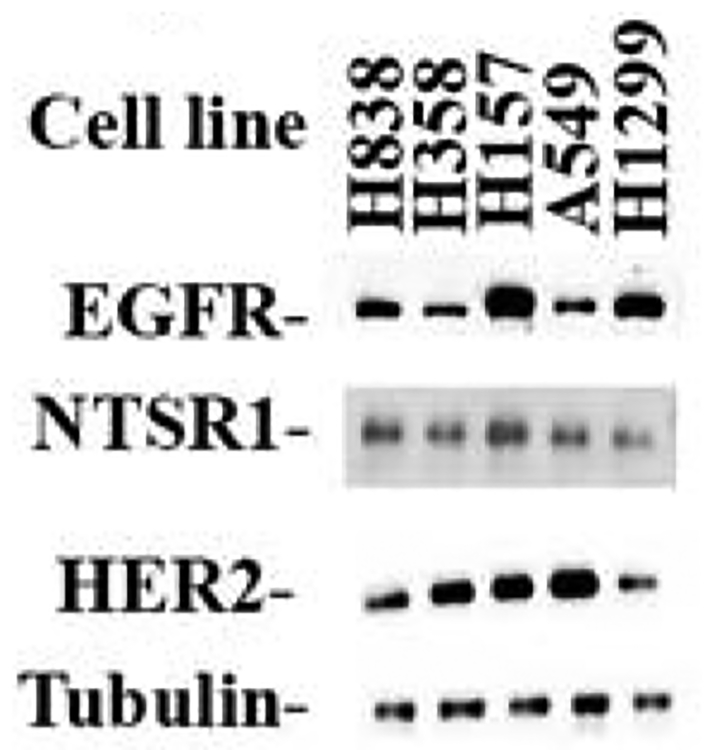

The presence of neurotensin receptor 1 protein was investigated by Western blot. Fig. 2 shows that moderate levels of neurotensin receptor 1 were present in the 5 NSCLC cell lines examined. Neurotensin receptor 1 (55 kDa) was present in NCI-H838, H358, H1299, H157 and A549 cells. Neurotensin receptor 1 was biologically active in that seconds after addition of 100 nM NTS to NCI-H1299 or A549 cells, the cytosolic Ca2+ was elevated (Moody et al., 2014). Also, Fig. 2 shows that receptor tyrosine kinases are present in NSCLC cells. High levels of total EGFR (170 kDa) were present in NCI H838, H157 and H1299 cells, whereas moderate levels were present in NCI-H358 and A549 cells. High levels of HER2 (190 kDa) are present in NCI-H358, H157 and A549 cells, whereas moderate levels were present in H838 and H1299 cells. As a control, equal levels of tubulin were present in all 5 NSCLC cell lines examined.

Fig. 2.

Western blot. NSCLC cellular extracts (40 μg) were loaded onto SDS-acrylamide gels. After transfer to nitrocellulose the blots were treated with anti-neurotensin receptor 1, anti-EGFR, anti-HER2 or anti-tubulin. This autoradiogram is representative of 3 others.

3.2. Neurotensin increases tyrosine phosphorylation of EGFR, HER2 and ERK.

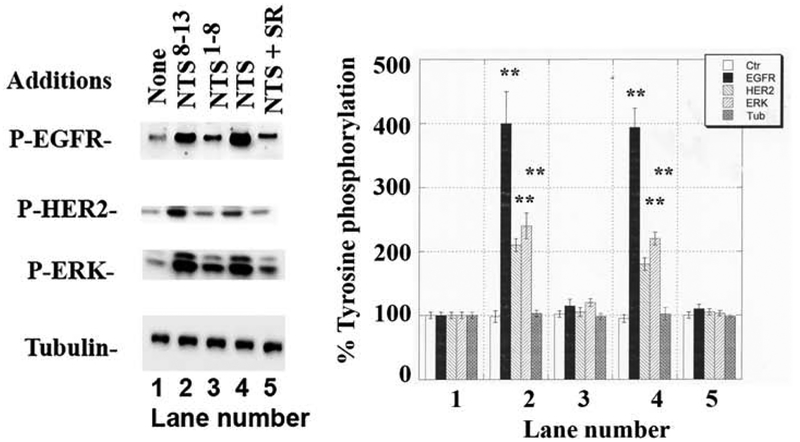

The ability of neurotensin ligands to increase the tyrosine phosphorylation of the EGFR, HER2 and ERK was investigated. Fig. 3 shows that 2 min after addition of 100 nM neurotensin to NCI-H838 cells, EGFR, HER2 and ERK tyrosine phosphorylation increased to 400, 180 and 200%, respectively. Similarly, addition of 100 nM neurotensin8–13 but not neurotensin1–8 increased EGFR, HER2 and ERK tyrosine phosphorylation significantly to 410, 200 and 220% respectively. If SR48692 (1000 nM) plus 100 nM neurotensin was added to NCI-H838 cells there was no significant increase in PY1068-EGFR, PY1248-HER2 or PY204-ERK. The results indicate that neurotensin and neurotensin8–13 are neurotensin receptor 1 agonists whereas SR48692 is an antagonist.

Fig. 3.

Neurotensin ligands and tyrosine phosphorylation. (Left) Neurotensin (NTS) analogs (100 nM) were added to NCI-H838 cells for 2 min and the phosphorylation of EGFR, HER2 and ERK determined by Western blot. SR48692 (1 μM) blocked the ability of NTS to cause transactivation of the EGFR and HER2. (Right). The mean values ± S.D. of 3 experiments is indicated; p < 0.01, ** relative to control by ANOVA.

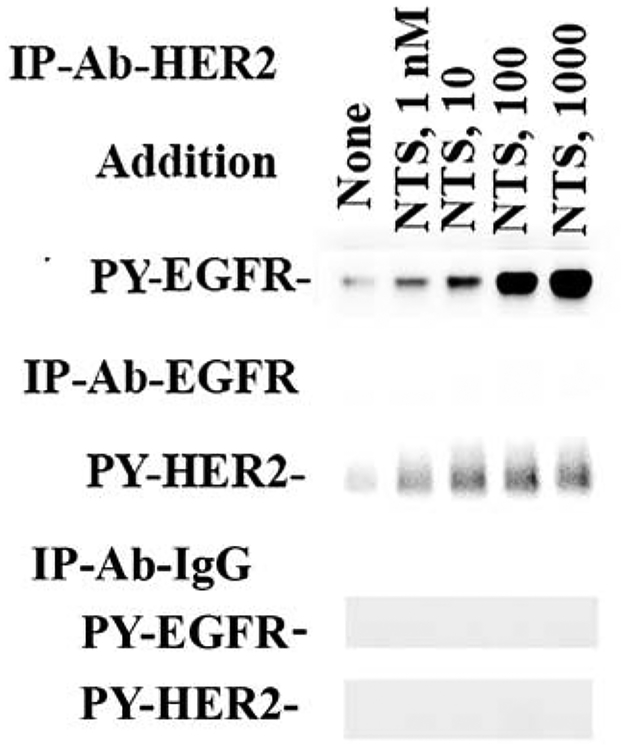

The presence of EGFR/HER2 heterodimers was investigated. NCI-H838 cells were treated with varying doses of neurotensin and immunoprecipitations performed. Fig. 4 shows that if the extracts were treated with anti-EGFR, PY-HER2 increased in a dose-dependent manner and the ED50 for neurotensin was 7 ± 2 nM. If the extracts were treated with anti-HER, PY-EGFR increased in a dose-dependent manner and the ED50 for neurotensin was 5 ± 2 nM. As a control, PY-EGFR or PY-HER2 was not detected in the extracts treated with control IgG. The results indicate that phosphorylated EGFR/HER2 heterodimers increase after neurotensin addition.

Fig. 4.

Immunoprecipitation experiments. NCI-H838 were treated with varying doses of NTS. Then the extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-EGFR, anti-HER2 or anti-IgG control. The samples were run on gels, transferred to nitrocellulose and treated with antibodies to phospho- Tyr1248-HER2 or phospho-Tyr1068-EGFR. This experiment is representative of 2 others.

3.3. Reactive oxygen species inhibitors impair EGFR and HER2 transactivation

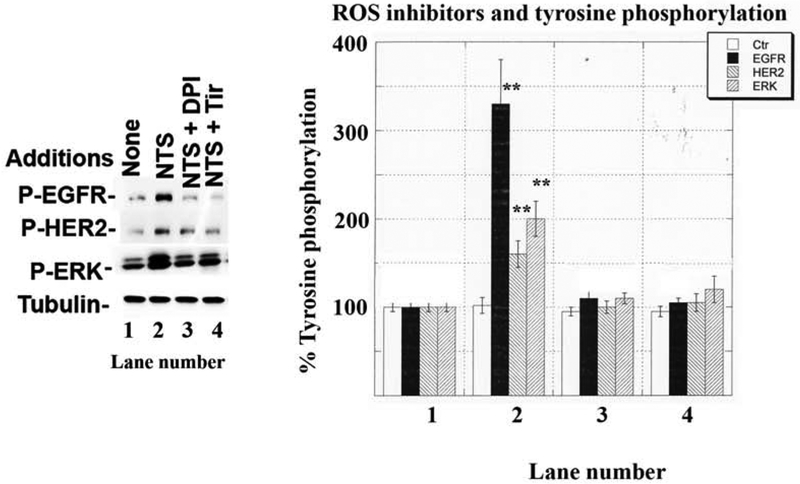

The presence of reactive oxygen species was determined in NSCLC cells. Table II shows that 1 hour after addition of 100 nM neurotensin to NCI-H838 cells, reactive oxygen species increased to 228% whereas addition of 10 uM H2O2 increased reactive oxygen species to 1154%. Addition of 1 μM SR48692, 5 μM diphenylene iodonium (DPI inhibits the ability of NADPH oxidase (Nox) and dual oxidase (Duox) enzymes to produce reactive oxygen species) or 5 mM Tiron significantly reduced the reactive oxygen species increase caused by neurotensin addition to NCI-H838 cells. The effects of the reactive oxygen species inhibitors were further investigated on transactivation. Fig. 5 shows that neurotensin addition to NCI-H838 cells increased significantly phosphorylation of the EGFR, HER2 and ERK to 330, 170 and 200%, respectively. The increase in EGFR, HER2 and ERK tyrosine phosphorylation caused by neurotensin addition to NCI-H838 cells was significantly inhibited by addition of 5 μM DPI or 5 mM Tiron. The results indicate that DPI and Tiron impair the ability of neurotensin to increase reactive oxygen species and transactivation of EGFR and HER2 using NSCLC cells.

Table II.

Reactive oxygen species

| Addition | Reactive oxygen species (% control) |

|---|---|

| None | 100 ± 7 |

| H2O2 | 1154 ± 81aa |

| NTS | 228 ± 9aa |

| NTS + SR48692 | 115 ± 12 |

| NTS + DPI | 117 ± 15 |

| NTS + Tiron | 108 ± 6 |

NCI-H838 cells were loaded with 2’−7’-dichlorofluoresceine diacetate for 30 min land treated with NTS of H2O2 in the presence or absence of inhibitors. The mean value + S.D. of 8 determinations is indicate;

p < 0.01 relative to no additions by ANOVA. This experiment is representative of 2 others.

Fig. 5.

Effect of reactive oxygen species inhibitors on EGFR and HER2 transactivation. (Left) One μM DPI or 5 mM Tiron inhibited the ability of 100 nM NTS to increase tyrosine phosphorylation of the EGFR, HER2 and ERK. (Right). The mean value + S.D. of 4 experiments is indicted p < 0.01, ** relative to control by ANOVA.

3.4. Effects of lapatinib

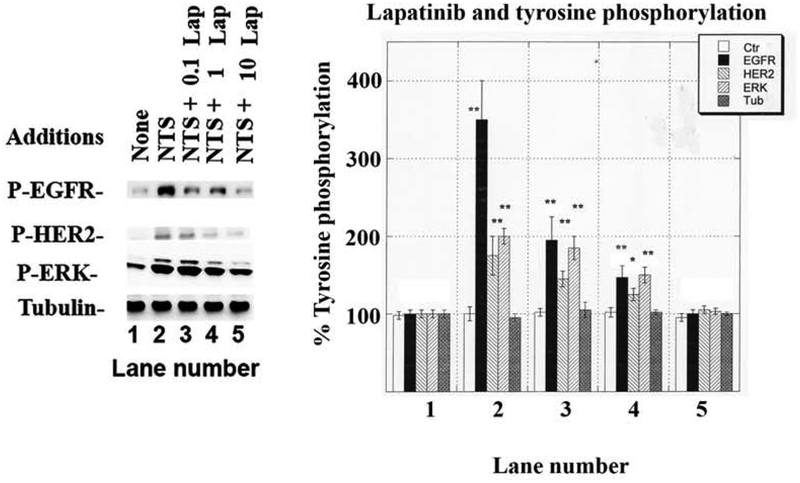

The effects of lapatinib, an EGFR and HER2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor, were investigated. Fig. 6 shows that 100 nM neurotensin increased significantly EGFR, HER2 and ERK tyrosine phosphorylation to 360, 170 and 200%, respectively. The increase in EGFR, HER2 and ERK tyrosine phosphorylation caused by neurotensin addition to NSCLC cells was reduced in a dose-dependent manner by lapatinib whereby 0.1 μM lapatinib impaired EGFR tyrosine phosphorylation, whereas 1 or 10 μM lapatinib significantly reduced EGFR, HER2 and ERK tyrosine phosphorylation caused by neurotensin. As a control, lapatinib had no effect on total tubulin.

Fig. 6.

Effect of lapatinib on EGFR, HER2 and ERK tyrosine phosphorylation. (Left) The ability of varying doses of lapatinib to inhibit the increase in tyrosine phosphorylation of the EGFR, HER2 and ERK caused by 100 nM NTS was determined. (Right) The mean value ± S.D. of 3 experiments is indicated, p < 0.05, *; p < 0.01, ** relative to control by ANOVA.

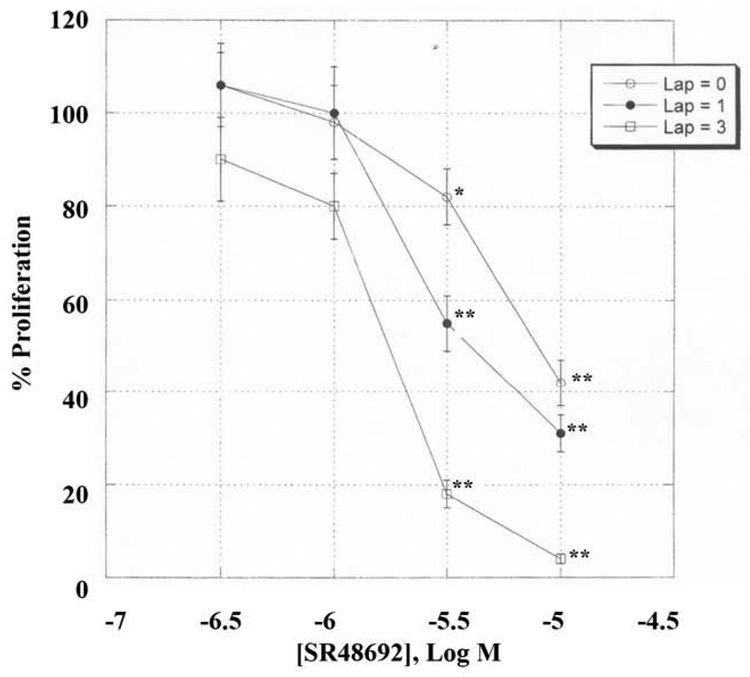

The ability of neurotensin and other agents to alter the proliferation of NSCLC cells was investigated. Table III shows that NTS increased the NCI-H838 colony number significantly by 74%. The increase in proliferation caused by neurotensin was inhibited by SR48692, lapatinib or DPI. SR48692 decreased basal proliferation by 49%. Similarly, lapatinib or DPI significantly decreased basal NCI-H838 colony number. Surprisingly, the growth inhibitory activity of SR48692 and lapatinib was greater than either agent alone. This was further investigated using the MTT assay. Fig. 7 shows that SR48692 in a dose-dependent manner with an IC50 value of 5 μM. Lapatinib shifted the SR48692 dose-response curve to the left. The combination index (0.76 ± 0.12) indicated that SR48692 and lapatinib are synergistic at inhibiting NSCLC proliferation (Chou and Talalay, 1984).

Table III.

Clonogenic Assay

| Addition | Colony number | + 10 nM NTS |

|---|---|---|

| None | 31 ± 4 | 54 ± 8a |

| SR48692 | 16 ± 7a | 33 ± 3 |

| Lapatinib | 19 ± 3a | 37 ± 6 |

| SR48692 + Lapatinib | 7 ± 2aa | 22 ± 3a |

| DPI | 22 ± 4a | 36 ± 5 |

The mean value ± S.D. of 3 determinations is indicated using NCI-H838 cells;

p < 0.05,;

p < 0.01, relative to control by ANOVA. This experiment is representative of 2 others.

Fig. 7.

Proliferation assay. In the MTT assays NCI-H838 cells were treated with varying concentrations of lapatinib and SR48692. The mean value ± S.D. of 8 determinations is indicated. This experiment is representative of 2 others p < 0.05, *; p < 0.01, ** relative to control by ANOVA.

4. Discussion

NSCLC is an epithelial tumor which kills approximately 130,000 citizens in the United States annually that is traditionally treated with platinum-based chemotherapy but the overall survival for advanced NSCLC is only 7.9 months (Qiu et al 2018). NSCLC overexpresses numerous G protein-coupled receptors and is characterized by mutations in the EGFR, amplification of HER2 and inactivation of p53 and p16 (Kaufman et al., 2011). EGFR alterations such as L858R, G719C and deletions in amino acids 747–751 are common depending on the patient sex, ethnicity and smoking history resulting in increased tyrosine kinase activity. The tyrosine kinase inhibitors gefitinib or erlotinib can be used to treat patients with EGFR mutations who have failed chemotherapy but resistance to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor develops primarily due to EGFR T790M mutations (Santoni-Rugiu et al., 2019). Recently, pembrolizumab, an immune checkpoint inhibitor, has provided significant advantage in management of non-resectable lung cancer (Qin and Li, 2019)

In this study neurotensin receptors were investigated in NSCLC cells. By RT-PCR, neurotensin receptor 1 but not neurotensin receptor 2 mRNA was present in all 10 NSCLC cell lines examined. By Western blot, neurotensin receptor 1 protein was present in all 5 NSCLC cell lines examined. By receptor binding, neurotensin or neurotensin8–13, but not neurotensin1–8, bound with high affinity to NCI-H838 cells. Neurotensin or neurotensin8–13, but not neurotensin1–8, increased tyrosine phosphorylation of EGFR, HER2 and ERK. The effects of neurotensin on EGFR and HER2 transactivation were antagonized by SR48692. The levels of neurotensin receptor1 are not static but can be altered in cancer cells. Neurotensin receptor 1 levels can be increased by neurotensin addition to cancer cells (Toy-Miou-Leong et al., 2004) primarily due to activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway (Wu et al., 2017). In colorectal cancer, noninvasive tumors have high levels of methylated neurotensin receptor 1, whereas invasive colorectal cancer has unmethylated neurotensin receptor 1(Kamimae et al., 2015). Sodium butyrate, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, reduced neurotensin receptor 1 densities leading to colorectal cancer differentiation, apoptosis and growth arrest (Wang et al., 2010). Treatment of NCI-H1299 or A549 lung cancer cells with siRNA to the neurotensin receptor 1 down-regulated expression of neurotensin receptor 1 by approximately 50% (Moody et al., 2014). The results indicate that up-regulation of neurotensin receptor 1 is associated with cancer proliferation, where tumor growth is impaired with down-regulation of neurotensin receptor 1.

Neurotensin addition to NSCLC cells increases metabolism of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate and the diacylglycerol released activates PKC, whereas the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate released causes elevation of cytosolic Ca2+ (Staley et al., 1988). In prostate cancer cells, neurotensin addition increased phosphorylation of c-Src, Stat5b and the EGFR (Amorino et al., 2007). Addition of neurotensin to A549 cells increased the tyrosine phosphorylation of c-Src, β-catenin, PYK-2 and the EGFR. The EGFR tyrosine phosphorylation was blocked by U73122 (phospholipase C inhibitor), PP2 (Src inhibitor) or GM6001 (matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor (Moody et al.,2014). In lung cancer cells matrix metalloproteinase increases the catalysis of inactive pro-TGFα to biologically active TGFα, which causes tyrosine phosphorylation of the EGFR (Moody et al 2016).

Activation of the EGFR or HER2 leads to stimulation of the MAP kinase pathway resulting in increased phosphorylation of ERK. Addition of neurotensin to lung cancer cells increases ERK phosphorylation which is impaired by SR48692, lapatinib, DPI or tiron. Phosphorylated ERK can enter the nucleus and alter the expression of growth factor genes (Ehlers et al., 2000). Addition of neurotensin to lung cancer cells increases phosphorylation of β-catenin. Phosphorylated β-catenin interacts with the Tcf transcriptional complex in the nucleus (Souaze et al., 2006) leading to increased neurotensin receptor 1 expression enhancing epithelial-to- mesenchymal transitions and promoting hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis by activating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway (Ye et al., 2016). Neurotensin activates Akt and NF-κB leading to increased cancer cellular survival (Hassan et al., 2004, Zhao et al., 2003). Neurotensin uses multiple signal transduction pathways to facilitate the development of cancer.

Neurotensin addition to NSCLC cells increased reactive oxygen species which was impaired by SR48692, Tiron (superoxide scavenger) and DPI (inhibitor of Nox and Duox). NCI-H838 cells have mRNA for Nox1, Nox3, Nox5, Duox1 and Duox2 but DPI inhibits all Nox and Duox enzymes (Moody et al., 2018, Doroshow et al., 2012). The ability of neurotensin to increase tyrosine phosphorylation of the EGFR, HER2 and ERK was impaired by SR48692, DPI or lapatinib. The growth of NSCLC cells was increased by neurotensin but decreased by SR48692, DPI or lapatinib. Reactive oxygen species may increase the tyrosine phosphorylation of the EGFR due to oxidation of protein tyrosine phosphatases such as SHP1 leading to decreased phospho-tyrosine degradation (Lee et al., 1998). Alternatively, reactive oxygen species may oxidize Cys797 of the EGFR increasing phospho-tyrosine synthesis (Paulson et al., 2012; Heppner and Van der Vliet, 2016). The results indicate that neurotensin receptor 1 activation leads to the generation of reactive oxygen species which facilitate EGFR and HER2 transactivation.

Neurotensin stimulates the clonal growth of NSCLC cells. The proliferation of NSCLC cells is inhibited by SR48692. The growth of A549 cells was impaired by siRNA to the neurotensin receptor 1, and when the neurotensin receptor 1 levels were reduced the growth inhibitory effects of SR48692 were impaired (Moody et al., 2014). The clonal growth of NCI-H838 cells is inhibited by lapatinib, an EGFR and HER2 tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Previously, SR48692 was synergistic with gefitinib at inhibiting NSCLC growth. Here, SR48692 and lapatinib were synergistic at inhibiting the growth of NSCLC cells. The results indicate that neurotensin receptor 1 antagonists can potentiate the cytotoxicity of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in NSCLC. Using PC-3M prostate cancer cells, SR48692 enhanced sensitivity to ionizing radiation (Valerie et al., 2011).

Recently, a monoclonal antibody to the neurotensin precursor protein (LF-NTS mAb) was developed which alters the homeostasis of tumors which overexpress neurotensin receptor 1 (Wu et al., 2019). Treatment of tumor cells with neurotensin increased expression of neurotensin receptor 1 whereas treatment with LF-NTS-mAb reduced neurotensin receptor 1 expression. This results in decreased tumor proliferation and metastasis. Surprisingly treatment of NSCLC tumors with LF-NTS-mAb increases sensitivity to cis-platin.

The EGFR contains 1210 amino acids whereas HER2 contains 1255 amino acids (Yarden and Pines, 2012). The 621 amino acid N-terminal of the EGFR has four domains and domains I as well as III participate in binding of ligands such as amphiregulin, β-cellulin, EGF, epigen, epiregulin, heparin binding EGF and transforming growth factor α, whereas a ligand for HER2 is unknown. Domains II and IV of the EGFR are enriched in cysteine amino acids and domain II causes homodimer and heterodimer formation of ErbB family members (Roskoski, 2019). The cytoplasmic domain for both the EGFR and HER2 has tyrosine kinase activity (Lemmon et al., 2014). NTS addition to NCI-H838 cells causes high levels of EGFR tyrosine phosphorylation, whereas there are moderate levels of HER2 tyrosine phosphorylation. These data suggest that neurotensin receptor 1 primarily regulates formation of EGFR homodimers in preference to the formation of EGFR/HER2 heterodimers. Neurotensin in a dose-dependent manner increased the tyrosine phosphorylation of the EGFR and HER2. If the cellular extract was immunoprecipitated with anti-EGFR, the phosphorylation of Tyr1248-HER2 was observed using 100 but not 1 nM NTS. If the cellular extract was immunoprecipitated with anti-HER2, increased tyrosine phosphorylation of Tyr1068-EGFR was observed using 100 but not 1 nM NTS. Addition of NTS to lung cancer cells increased expression of EGFR, HER2 and HER3 after 24 h (Younes et al., 2014). Preliminary data indicate that HER2 can form heterodimers with HER3 in lung cancer cells (L Lee, unpublished). The results indicate that G protein-coupled receptors regulate the transaction on numerous receptor tyrosine kinases in lung cancer. Use of G-protein coupled receptor antagonists combined with receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors may yield novel approaches for the treatment of lung cancer.

In conclusion, neurotensin receptor 1 regulates the tyrosine phosphorylation of the EGFR, HER2 and ERK in NSCLC cells by signaling cascades involving reactive oxygen species. The results suggest that many of the growth effects caused by peptide G protein-coupled receptors may result from activation of lung cancer receptor tyrosine kinases.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. T. Leto for helpful discussions. This research is supported by the NIH intramural programs of NIDDK and NCI.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alifano M, Souaze F, Dupouy S, Camilleri-Broet S, Younes M, Ahmed-Zaid SM, Takahashi T, Cancellieri A, Damiani S, Boaron M, Broet P, Miller LD, Gespach C, Regnard JF, Forgez P 2010. Neurotensin receptor 1 determines the outcome of non-small cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 16: 4401–4410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen AE, Carney DN, Moody TW 1988. Neurotensin binds with high affinity to small cell lung cancer cells. Peptides 9: 57–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amorino GP, Deeble PL, Parsons SL 2007. Neurotensin stimulates mitogenesis of prostate cancer cells through a novel c-Src/Stat 5b pathway. Oncogene 26: 745–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betacur C, Canton M, Burgos A, Labeeuw B, Gully D, Rostene W, Pelaprat D 1998. Characterization of binding sites of a new neurotensin receptor antagonist, [3H]ST 142948A in the rat brain. Eur. J. Pharmacol 343: 67–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carraway R, Leeman SE 1973. The isolation of a new hypotensive peptide, neurotensin, from bovine hypothalamus. J. Biol. Chem 248: 6854–6861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaolin P Vita N, Kaghad M, Guillemot M, Bonnin J, Delpech B, Le Fur G, Ferarra P, Caput D 1996. Molecular cloning of a levocabastine sensitive neurotensin binding site. FEBS Lett. 386: 91–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou TC, Talalay P 1984. Quantitative analysis of dose-effect relationships: The combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 22: 27–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Florio A, Sancho V, Moreno P, Delle Fave G, Jensen RT 2013. Gastrointestinal hormones simulate growth of foregut neuroendocrine tumors by transactivating the EGF receptor. Biochem. Biophys. Acta 1833: 573–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doroshow JH, Juhasz A, Ge Y, Holbeck S, Lu J, Antony S, Wu Y, Jiang G, Roy K 2012. Antiproliferative mechanisms of action of the flavin dehydrogenase inhibitors diphenylene iodonium and di-2-thienyliodomium based on molecular profiling of the NCI-60 human tumor cell panel. Biochem. Pharmacol 83: 1195–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers RA, Zhang Y, Hellmich MR, Evers BM 2000. Neurotensin-mediated activation of the MAPK pathways and AP-1 binding in the human pancreatic cancer cell line MIA PaCa-2. Biochem. Biopys. Res. Comm 269: 704–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evers BM 2006. Neurotensin and growth of normal and neoplastic tissues. Peptides 27: 2424–2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan S, Dobner PR, Carraway RE 2004. Involvement of MAP kinase, PI-3-kinase and EGF-receptor in the stimulatory effect of neurotensin on DNA synthesis in PC3 cells. Regul. Peptides 120: 155–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heppner DE, Van der Vliet A 2016. Redox-dependent regulation of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling. Redox Biol. 8: 24–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamimae S, Yamamoto E, Kai M, Ninuma T, Yamano HO, Nojima M, Yoshikawa K, Kimura T, Takagi R, Harada E, Harada T, Maruyama R, Sasaki Y, Tokino T, Shinomura Y, Sugai T, Imai K, Suzuki H 2015. Epigenetic silencing of NTSR1 is associated with lateral and noninvasive growth of colorectal tumors. Oncotarget 6: 29975–29990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Horn L, Carbone D 2011. Molecular biology of lung cancer, in De Vita V Jr Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA (Eds.) Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, pp.789–798. [Google Scholar]

- Kisfalvi K, Guha S, Rozengurt E 2005. Neurotensin and EGF induce synergistic stimulation of DNA synthesis by increasing the duration of ERK signaling to ductal pancreatic cancer cells. J. Cell. Physiol 202: 880–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitabgi P 2010. Neurotensin and neuromedin N are differentially processed from a common precursor by prohormone convertases in tissues and cell lines. Results Probl. Cell Differ. 50:85–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SR Kwon KS, Kim SR, Rhee SL 1998. Reversible inactivation of protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B in A431 cells stimulated with epidermal growth factor. J. Biol. Chem 273: 15366–15372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmon MA, Schlessinger J, Ferguson KM 2014. The EGFR family: Not so prototypical receptor tyrosine kinase. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol April 1;6(4):a020768.doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a020768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyton J, Garcia-Marin L, Jensen RT, Moody TW 2002. Neurotensin causes tyrosine phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase in lung cancer cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol 442: 179–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody TW, Carney DN, Korman LY, Gazdar AF, Minna JD 1985. Neurotensin is produced and secreted by classic small cell lung cancer cells. Life Sci. 36: 1727–1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody TW, Chiles J, Casibang M, Moody E, Chan D, Davis TP 2001. SR48692 is a neurotensin receptor antagonist which inhibits the growth of small cell lung cancer cells. Peptides 22: 109–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody TW, Chan DC, Mantey SA, Moreno P, Jensen RT 2014. SR48692 inhibits non-small cell lung cancer proliferation in an EGFR receptor-dependent manner. Life Sci. 100: 25–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody TW, Nuche-Berenguer B, Nakamura T, Jensen RT 2016. EGFR transactivation by peptide G protein-coupled receptors in cancer. Curr. Drug Targets 17: 520–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody TW, Lee L, Iordanskaia T, Ramos-Alvarez I, Moreno P, Boudreau HE, Leto TL, Jensen RT 2018. PAC1 regulates receptor tyrosine kinase transactivation in a reactive oxygen species-dependent manner. Peptides SO196–9781(18)30174–8. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides2018.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller KM, Tveteraas IH, Aasrum M, Odegard J, Dawood M, Dajani O, Christoffersen T, Sandnes DL 2011. Role of protein kinase C and epidermal growth factor receptor signaling in growth stimulation by neurotensin in colon carcinoma cells. BMC Cancer 11: 421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407.11-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ocejo-Garcia M, Ahmed SI, Coulson JM, Woll PJ 2001. Use of RT-PCR to detect co-expression of neuropeptides and their receptors in lung cancer. Lung Cancer 33: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulson CE, Troung TH, Garcia FJ, Homann A, Gupta V, Leonard SE, Carrol KS 2012. Peroxide-dependent sulfenylation of the EGFR catalytic site enhances kinase activity. Nature Chem. Biol 8: 57–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Q and Baosheng L 2019. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of nonsmall cell lung cancer: Current status and future discussions. J. Cancer Res. and Therapeutics. 15: 743–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Z, Chen Z Zhang C, Zhong W 2019. Achievements and futures of immune checkpoint inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer. Exp. Hematol. Oncol 8:19.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reubi JC, Waser B, Schaer JC, Laissue JA 1999. Neurotensin receptors in human neoplasm: High incidence in Ewing’s Sarcoma. Int. J. Cancer 82: 213–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roskoski R Jr. 2019. ErbB/HER protein-tyrosine kinases: Structures and small molecule inhibitors. Pharmacological Research 139: 395–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoni-Rugiu E, Melchior LC, Urbanska EM, Jakobsen JN, Stricker K, Grauslund M, Sorensen JB 2019. Intrinsic resistance to EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors in EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer: Differences and similarities with acquired resistance. Cancers 11:923–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souaze F, Viardot-Foucault V, Roullet N, You-Miou-Leong M, Gompei A, Bruyneel E, Comperat E, Faux MC, Mareel M, Rostene W, Flejou JF, Gespach C, Forgez P 2006. Neurotensin receptor 1 gene activation by the Tcf/β-catenin pathway is an early event in human colonic adenomas. Carcinogenesis 27: 708–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staley J, Fiskum G, Davis TP, Moody TW 1989. Neurotensin elevates cytosolic calcium in small cell lung cancer cells. Peptides 10: 121–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toy-Miou-Leong M, Bachelet CM, Pelaprat D, Rostene W, Forgez P 2004. NT agonist regulates expression of nuclear high-affinity neurotensin receptors. J. Histochem. Cytochem 52: 335–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valerie NCK, Casarez EV, DaSilva JO, Dunlap-Brown ME, Parsons JJ, Amorino GP, Dziegielewski J 2011. Inhibition of neurotensin receptor 1 selectively sensitizes prostate cancer to ionizing radiation. Cancer Res. 71: 6817–6826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Jackson LN, Johnson SM, Wang X, Evers BM. 2010. Suppression of neurotensin receptor type 1 expression and function by histone deacetylase inhibitors in human colorectal cancers. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics 9: 2389–2398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JF, Noinaj N, Shibata Y, Love J, Kloss B, Xu F, Gvozdenovic-Jeremic J, Shah P, Shiloach J, Tate CG, Grisshammer R 2012. Structure of the agonist-bound neurotensin receptor. Nature 490: 508–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson CM, Naves T, Saada S, Pinet S, Vincent F, Lailoue F, Jauberteau MO 2014. The implications of sortilin/vps 10p domain receptors in neurological and human diseases. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 13: 1354–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood SM, Wood JR, Ghatei MA Lee YC, O’Shaughnessy D, Bloom SR 1981. Bombesin, somatostatin and neurotensin-like immunoreactivity in bronchial carcinoma. J Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 53: 1310–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Galmiche A, Liu J, Stadler N, Wendum D, Segal-Bendirdjian E, Paradis V, Forgez P 2017. Neurotensin regulation induces overexpression and activation of EGFR in HCC and restores response to erlotinib and sorafenib. Cancer Lett. 388: 73–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Fournel L, Stadler N, Liu J, Boullier A, Hoyeau N, Flejou JF, Duchatelle V, Djebrani-Oussedik, Agoplantz M, Segal-Bendirdjian E, Gompel A, Alifano M, Melander O, Tredaniel J, Forgez P 2019. Modulation of lung cancer cell plasticity and heterogeneity with the restoration of cisplatin sensitivity by neurotensin antibody. Cancer Lett. 444.: 147–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarden Y, Pines G 2012. The ERBB network: At last, cancer therapy meets system biology. Nature Reviews/Cancer 12: 553–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y, Long X, Zhang L Chen J, Lin P, Li H, Wei F, Yu W, Ren X, Yu J 2016. NTS/NTSR1 co-expression enhances epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and promotes tumor metastasis by activating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget 7: 70303–70322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younes M, Wu Z, Dupouy S, Lupo AM, Mourra N, Takahashi T, Flejou JL, Tredaniel J, Regnard JF, Damotte D, Alfano M, Forgez P 2014. Neurotensin (NTS) and its receptor (NTSR1) causes EGFR, HER2 and HER3 over-expression and their autocrine/paracrine activation in lung tumors, confirming responsiveness to erlotinib. Oncotarget 5: 8252–8269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao D, Kuhnt-Moore S, Zeng H, Wu JS, Moyer MP, Pothaoulaki SC. 2003. Neurotensin stimulates IL-8 expression in human colonic epithelial cells through Rho GTPase-mediated NF-kappa B pathways. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 184:C1397–C1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Xie J, Cai Y, Yang S, Chen Y, Wu H 2015. The significance of NTR1 expression and its correlation with β-catenin and EGFR in gastric cancer. Diagn. Pathol 100: 173 doi: 10.1186/s13000-015-356-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]