Abstract

Background

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is an autoimmune disease that is increasing in prevalence worldwide. One of the contributing factors to the pathogenesis of T1D is the composition of the intestinal microbiota, as has been demonstrated. in T1D patients, with some studies demonstrating a deficiency in their levels of Prevotella. We have isolated a strain of Prevotella histicola from a duodenal biopsy that has anti-inflammatory properties, and in addition, alters the development of autoimmune diseases in mouse models. Therefore, our hypothesis is that the oral administration of P. histicola might delay the development of T1D in the non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice. To assess this, we used the following materials and methods. Female NOD mice (ages 5–8 weeks) were administered every other day P. histicola that was cultured in-house. Blood glucose levels were measured every other week. Mice were sacrificed at various time points for histopathological analysis of the pancreas. Modulation of immune response by the commensal was tested by analyzing regulatory T-cells and NKp46+ cells using flow cytometry and intestinal cytokine mRNA transcript levels using quantitative RT-PCR. For microbial composition, 16 s rRNA gene analysis was conducted on stool samples collected at various time points.

Results

Administration of P. histicola in NOD mice delayed the onset of T1D. Beta diversity in the fecal microbiomes demonstrated that the microbial composition of the mice administered P. histicola was different from those that were not treated. Treatment with P. histicola led to a significant increase in regulatory T cells with a concomitant decrease in NKp46+ cells in the pancreatic lymph nodes as compared to the untreated group after 5 weeks of treatment.

Conclusions

These observations suggest that P. histicola treatment delayed onset of diabetes by increasing the levels of regulatory T cells in the pancreatic lymph nodes. This preliminary work supports the rationale that enteral exposure to a non pathogenic commensal P. histicola be tested as a future therapy for T1D.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12866-021-02406-9.

Keywords: Diabetes, prevotella, Histicola, Microbiome, Non-obese

Background

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) has been increasing in prevalence in the last couple of decades [1–3]. Studies have shown that the intestinal microbiome of T1D patients is altered from healthy controls (dysbiosis) [4–6]. One study demonstrated that placing non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice, a mouse model of T1D, into a germ free condition inhibited the development of hyperglycemia in these mice [7]. In a prior study, we demonstrated that altering the composition of the microbiome through dietary changes can also result in a low incidence of hyperglycemia in NOD mice [8]. Another study found that altering the composition of the intestinal microbiome by administering antibiotics actually accelerated the onset and increased the level of severity of hyperglycemia in NOD mice [9]. These studies clearly suggest that the intestinal microbiome has a significant impact upon the development of hyperglycemia in NOD mice. However, results with humans are not as clear. A number of epidemiological studies have shown that administering antibiotics for infections during childhood did not increase the risk for T1D in genetically susceptible individuals [10, 11], albeit the study by Mikkelsen et al. demonstrated that administering antibiotics 5 times or more in infancy increased the risk of T1D [11]. Genetically susceptible children born by Cesarean section (broad spectrum antibiotic given to the mother) are also at greater risk of developing T1D than one that is born vaginally [12]. In addition, one study reported that the microbiomes of a child born by Cesarean section had bacteria that were from the mother’s skin and oral mucosa, which was dominated by Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium, and Propionibacterium; however, children born vaginally had microbiomes composed primarily of bacteria associated with the mother’s vagina, dominated by Lactobacillus, Prevotella, and Sneathia [13]. These data suggest that while some microbiota can inhibit the development of T1D, others such as Lactobacillus casei to NOD mice leads to the suppression of diabetes [14]. A clinical trial testing the efficacy of Lactobacillus Johnsonii to alter immunological reactions in adult patients with T1D is expected to be concluded in July of 2020 (NCT03961347). Recently we identifieded a novel strain of Prevotella histicola (P. histicola) with anti inflammatory properties that effectively inhibited collagen induced arthritis (CIA) and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) in humanized mice [15, 16]. In addition, some studies have demonstrated that T1D patients have lower levels of Prevotella species as compared to healthy controls [17, 18]. Other publications have shown that NOD mice destined to develop T1D also have decreased levels of Prevotella [19, 20]. Because of its effectiveness in inhibiting the mouse models of rheumatoid arthritis (CIA) and multiple sclerosis (EAE), we tested our strain of P. histicola for its ability to delay or inhibit the development of T1D in NOD mice.

Results

Early treatment with P.histicola delays the onset of T1D

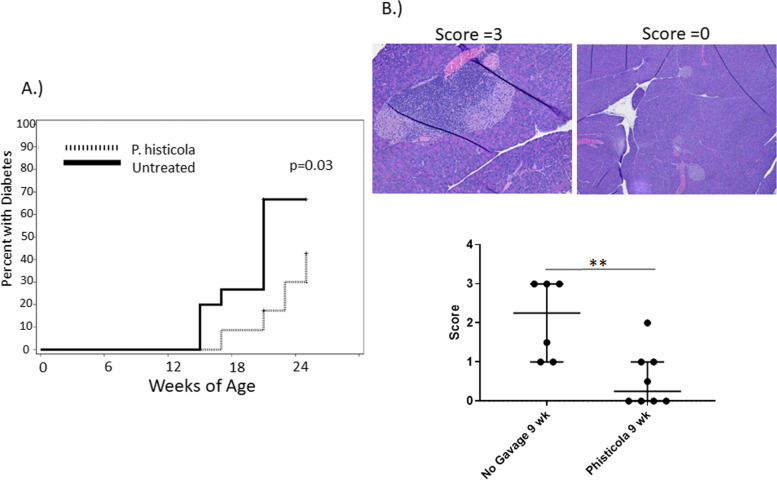

To determine if the long term administration of P. histicola did affect the onset of T1D in NOD mice, 5–8 week old female NOD mice (Jackson Laboratories) were allowed to acclimate for 1 week, and then given live P. histicola every other day. As figure one demonstrates, orally administering P. histicola significantly delayed the onset of T1D. The initial onset for the control mice that were not given P. histicola was 14 weeks of age, and the median onset age for the untreated group was 21 weeks of age. In comparison, initial onset for the mice treated with P. histicola was 17 weeks of age and the median onset for the treated group was greater than 25 weeks of age. P histicola also delayed the onset as compared to additional controls of water alone (sham) and bacterial media alone (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Pancreatic histopathology

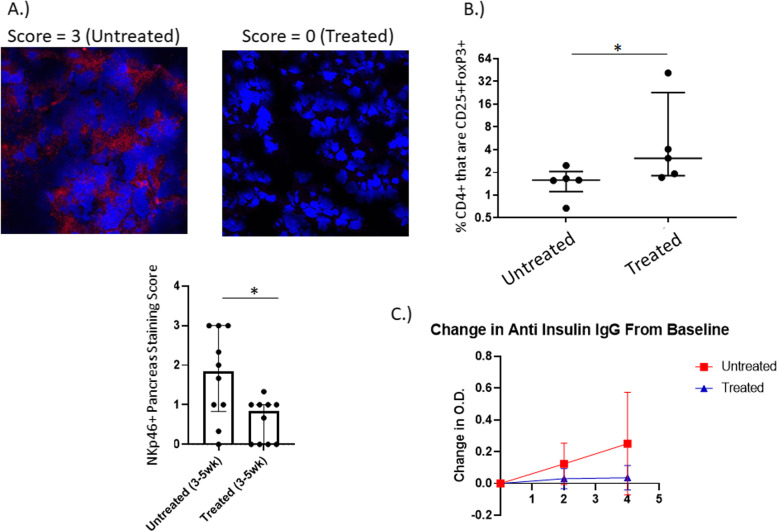

At 21 weeks of age, 14% of untreated mice had islet cells in the pancreas as determined by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, while 85% of mice in the treated group had islet cells remaining in their pancreas (Data not shown). These results demonstrate that P. histicola does have a protective effect upon the development of T1D. However, this was not complete protection, as the pancreatic B islet cells of the P. histicola treated mice at 21 weeks of age had become infiltrated. In order to determine if there was a difference in the pathology of the pancreas at earlier time points, mice were sacrificed at different time points of treatment with P. histicola: 13 weeks of age (7 weeks of treatment), 11 weeks of age (5 weeks of treatment), and 9 weeks of age (3 weeks of treatment). There was a significant difference in the level of cellular infiltration of the pancreas after 3 weeks of P histicola treatment (p < 0.01), but by 5 weeks of treatment, there was no significant difference between the two groups in the level of infiltration (Fig. 1 and supplementary Fig. 2). Immunohistochemistry staining of the pancreata of the NOD mice treated between 3 weeks and 5 weeks post treatment (9 weeks and 11 weeks of age respectively) revealed no difference in the number of FoxP3 + cells, CD4+ cells, or B220+ cells (supplementary Fig. 3). Additionally, no difference was found in the number of CD8+ cells after 5 weeks of treatment (supplementary Fig. 3). However, there was a significant reduction of NKp46+ cells in the pancreas of the NOD mice treated with P histicola for between 3 and 5 weeks (Fig. 2) of treatment. NKp46 is an activating receptor that is expressed by NK (natural killer) cells and innate lymphoid cells type 1 (ILC1) [21, 22] and has been demonstrated to be essential for the development of T1D, as the NKp46 ligand is expressed by pancreatic β islet cells [23]. This would suggest that in the NOD mouse, administration of P. histicola results in fewer NKp46+ cells in the pancreas.

Fig. 1.

A. Incidence of Diabetes. Five to – eight week old female NOD mice on a regular chow were administered P. histicola (dashed line, n = 23) or not (solid line, n = 15). Initial onset for the untreated group was 14 weeks of age and 16 weeks of age for the P. histicola treated group. The mean onset for the untreated was 21 weeks of age, and over 25 weeks of age for the treated group, which was significant (p = 0.03 Gray K-Sample). B . H&E staining of Pancreas. Hematoxylin and eosin stained pancreata from female NOD mice administered P. histicola for 3 weeks (9 weeks of age) were evaluated for inflammation on a score from 0 to 3. P. histicola treatment significantly decreased the inflammation of the pancreas score from a median of 2 to 1.5 (p < 0.01)

Fig. 2.

A. Immunohistochemistry of Pancreas. Cryosections of pancreata from NOD mice that were treated with P histicola for 3–5 weeks were stained for the presence of NKp46 and scored for intensity on a scale from 0 to 3. Treatment with P. histicola significantly decreased the intensity for NKp46 staining (p < 0.05). B. Regulatory T cells. NOD mice were treated with P. histicola (Treated) for between 3 and 5 weeks, and pancreatic lymph nodes extracted. % of CD4+ cells that are CD25%FoxP3+ cells significantly increased in the group treated with P. histicola (p < 0.05). Percentages were obtained by first gating on CD4+ cells, then generating dot plots of CD25 vs FoxP3. C. Levels of anti insulin IgG. Circulating levels of anti insulin IgG were evaluated at baseline, 2 weeks of treatment with P. histicola, and 4 weeks of treatement with P. histicola. The change in O. D, from baseline is plotted above and the mice that were treated with P. histicola (n = 10) had much less of an increase in anti insulin IgG than the untreated mice (n = 10)

Administration of P.histicola impacts systemic immune responses

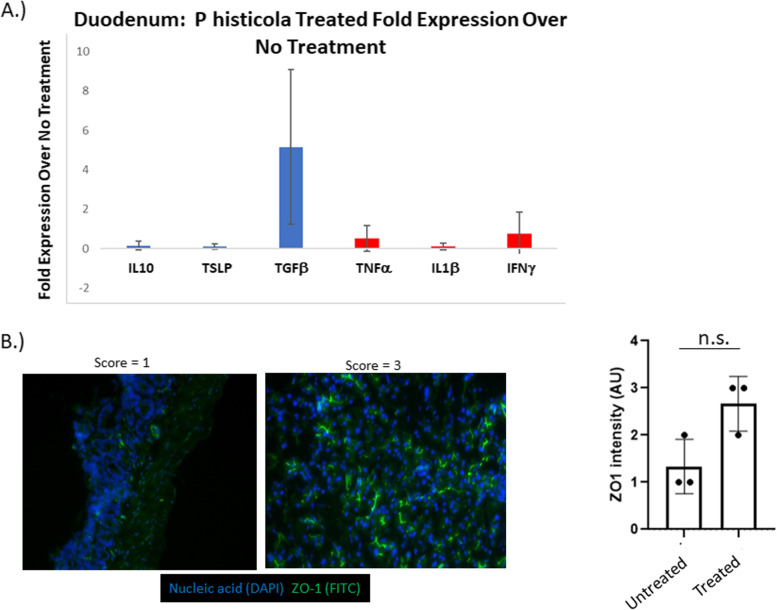

FACS analysis of the mesenteric lymph nodes, Peyer’s patches, pancreatic lymph nodes, and spleen were done on mice treated with P histicola for between 3 and 5 weeks. Regulatory T cells (CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+) made up a greater proportion of the CD4+ cells in the mice that were treated with the P. histicola, and was significantly greater in the pancreatic lymph nodes (Fig. 2). Evaluation of anti insulin IgG demonstrated that the administration of P. histicola led to less of an increase in circulating anti insulin IgG after 28 days (4 weeks) than in the untreated NOD mice (Fig. 2), even though there was no statistically significant difference. Analysis of duodenal cytokine production 18 h after gavaging with P. histicola demonstrated that there was an over five fold increase in the expression of TGFβ transcripts in P. histicola treated mice using untreated mice as the control group in the ΔΔ Ct calculation (Fig. 3). In contrast, the inflammatory cytokines, IL1β, IFNγ, and TNFα did not increase in the duodena from P. histicola treated NOD mice (Fig. 3). P histicola treatment increased expression of ZO-1, a tight junction protein, in the duodena of NOD mice, as shown in Fig. 3, albeit this was not statistically significant.

Fig. 3.

A. Intestinal cytokine mRNA. Duodenal segments from NOD mice 18 h after an oral treatment with P. histicola (n = 4) were evaluated for the fold expression of each cytokine over no treatment (n = 4). TGFβ had almost five fold increase with P histicola treatment. B. Zo1 Intestinal Expression. 18 h after treatment with P. histicola, the duodenum was extracted and stained for ZO-1. Intensity scores were on a scale of 0–3. The treated mice (n = 3) had a non-significant increase in ZO-1 expression over untreated (n = 3)

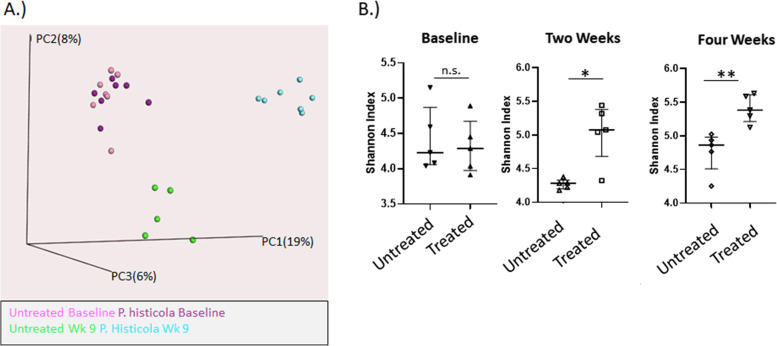

Microbiome analyses

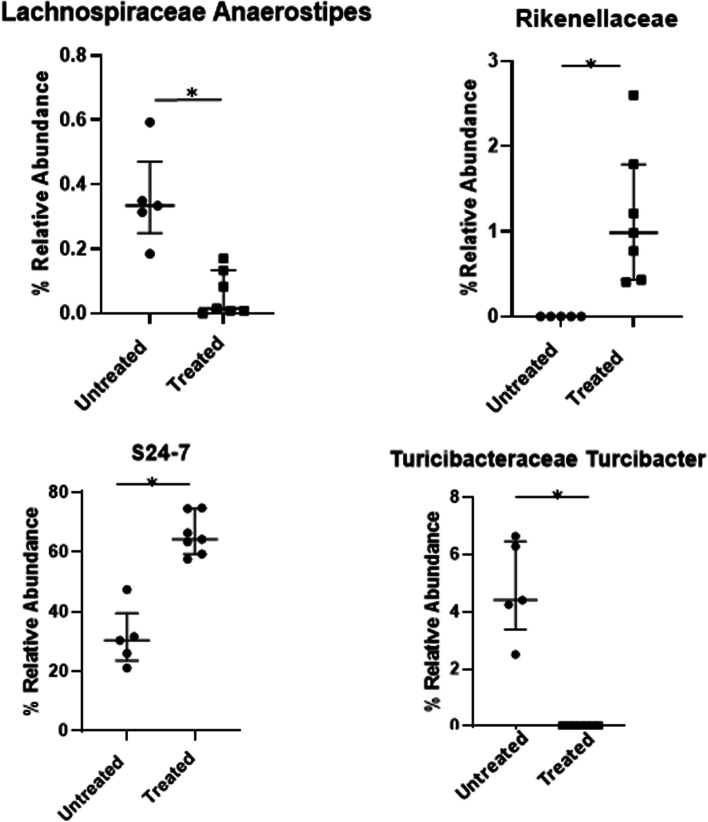

In order to determine what the changes were to the intestinal microbiomes of the NOD mice, analyses and comparisons of fecal samples were done using 16 s rRNA gene analysis. A beta diversity principal component plot demonstrates that the composition of the microbiome clearly changes after 9 weeks of administration of P. histicola (Fig. 4). The fecal microbiomes of the untreated mice also shifted from baseline, and this was distinct and separate from the fecal microbiomes of the mice treated with P. histicola for 9 weeks. Alpha diversity, as measured by Chao1, did not differ significantly between the untreated and P. histicola treated mice at any of the time points evaluated (data not shown). However, Alpha diversity, as evaluated by Shannon Index, demonstrated significant increases with 2 weeks of administering P. histicola along with a continued increase after 4 weeks of administering P. histicola, whereas the fecal microbiomes of the untreated mice did not change over the same time period (Fig. 4). The bacterial family S24–7 showed the most significant change (from 30% relative abundance of OTUs to 65% relative abundance of OTUs) and was the most abundant bacterial family in the mice (Fig. 5). A recent publication has suggested renaming S24–7 as Muribaculaceae [24], and found that the Muribaculaceae family was dominant in rodents, but was also found in other animals, including humans. This bacterium, S24–7, was associated with protection from diabetes in NOD mice [19]. Rikenellaceae was also increased with the administration of P. histicola, although the relative abundance was only 1% after the administration of P. histicola; however, a previous study has demonstrated that T1D in NOD mice is associated with decreased levels of Rikenellaceae [25]. The administration of P. histicola also inhibited the increase of Staphylococceae Staphylococcus and the Clostridium and Turcibacter families that was observed in the untreated control mice (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

A. Beta Diversity Plot of Fecal Microbiomes. Stool was collected at baseline and 9 weeks after administering P. histicola. Beta diversity was depicted in a 3 dimensional principal coordinate plot. The baseline of the untreated mice are depicted in pink, the baseline of the P histicola treated mice is depicted in lavender, the 9 week untreated group is green, and the 9 week P. histicola group is blue. B. Alpha Diversity Plot. Shannon Index is plotted for fecal microbiomes from baseline, 2 weeks, and 4 weeks of P histicola treatment along with corresponding untreated groups. There is an increasing trend of significant difference with time, such that the treated group is significantly higher than untreated at 2 weeks (p < 0.05). At 4 weeks after treatment the difference between the untreated and treated groups is greater (p < 0.01). n = 5 mice for untreated and n = 5 mice for P histicola treated

Fig. 5.

A. Increases in bacterial groups with P histicola treatment. The taxonomy of the fecal microbiomes at 9 weeks were compared and those bacterial groups that significantly increased were S24–7 and Rikenellaceae (p < 0.01 each). B. Decreases in bacterial groups with P histicola treatment. The bacterial groups that were significantly decreased with P. histicola treatment were Clostridium and the genus Staphylococcaceae Staphylococcus (p < 0.01 each). Turcibacteraceae Turcibacter and Lachnospiraceae Ruminococcus were also significantly decreased (p < 0.01 and p < 0.05, respectively)

Discussion

Treatment of NOD mice, a mouse model of T1D, with P. histicola effectively delays the onset of diabetes in these mice. Our results indicate that the administration of P. histicola to the NOD mice results in increased levels of regulatory T cells in the pancreatic draining lymph nodes. This hypothesis is supported by another study that found that regulatory T cells can traffic from the gut to the pancreatic lymph nodes [26]. Additionally, administering P. histicola significantly reduces the overall cellular infiltrate in the pancreatic β islets. When looking at immune cells present in the pancreas (CD3+, CD4+, CD8+, B220+, NKp46+), only those that express NKp46, are the cells that are significantly reduced by the administration of P. histicola. This would suggest that the administration of P. histicola exerts an anti inflammatory response in the intestines of the NOD mice, which then downregulates the extraintestinal inflammatory autoimmune response occuring in the pancreas of the NOD mice. We have previously shown that P. histicola colonizes the duodenum in mice and leads to an increase in intestinal Tregulatory cells and CD11b + myeloid suppressors [15, 27].

Data presented in this manuscript with NOD mice also shows that the administration of P. histicola increases the alpha diversity of the intestinal microbiomes of the mice. This result is similar to our findings in the mouse models of RA and MS. All of which suggest that the administration of P. histicola will improve the health of the intestinal microbiomes of the mice.

Of great interest is that the administration of P. histicola does not cause the same changes in specific bacterial groups as observed in the mouse model of MS. This is probably due to differences in the genetics of the mice, which results in different compositions of bacterial groups in the mice after weaning, and potentially before they are weaned as well. One of our previous publications demonstrated that a 3 amino acid difference in HLADR4 (0401 vs 0402) molecules resulted in differences in the intestinal microbiomes of the mice [28]. Therefore, it is quite reasonable to assume that genetic differences as great as the NOD genetic background from those of the humanized mice (HLA-DR4 and HLADR3) in the CIA and EAE studies would result in different baseline intestinal microbiomes before administering P. histicola and consequentially changes in intestinal bacterial groups after the administration of P. histicola differ between the models. Because of this then, it is unlikely that specific changes in the intestinal microbiome are exerting the anti-inflammatory responses in the intestinal epithelium, and are instead due to the intestinal epithelium responding to P. histicola or associated bacterial products. This is supported by an experiment in one of our previous observations in which the administration of antibiotics to deplete the microbiome of most bacteria, followed by the administration of P.histicola still inhibited the development of EAE in the mice [16]. A similar experiment with these NOD mice is not feasible, as studies have shown that administering antibiotics to NOD mice itself exacerbates the development of hyperglycemia [9, 25].

However, there are some limitations to this study. One limitation is that the study did not evaluate the mice beyond 25 weeks of age. Another limitation is that additional analyses beyond the incidence of diabetes was not done on the NOD mice gavaged with water alone (sham) and gavage with bacterial media. We also did not address the means by which P histicola can increase the number of Tregs. One example by which this may occur would be through CD11b + CD11c- antigen presenting cells (APCs) as demonstrated by Richer et al. [29] and by our previous studies [15].

Conclusions

In this study, we have shown that P. histicola effectively delays the onset of diabetes in NOD mice. From the three different mouse models of autoimmune disease (RA, MS, and now with this manuscript, T1D), we have observed that the commensal, P. histicola, will exert anti-inflammatory immune responses in the intestine. This intestinal anti-inflammatory immune response can then down regulate inflammatory autoimmune responses in different tissues throughout the animal. Overall then, these three studies support the premise that the administration of P. histicola could benefit patients with autoimmune diseases or who are at high risk of developing these autoimmune diseases.

Methods

Aim

To determine if the oral administration of P. histicola might delay the development of T1D in the non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice.

NOD mice

Female NOD Shi/Ltj mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine), aged between 5 weeks and 8 weeks of age. All mice were conventionally housed and maintained on a regular irradiated LabDiet rodent chow.

Method of euthanasia

All mice used in this study were humanely euthanized by CO2 inhalation as approved and directed by the Mayo Clinic IACUC.

Blood glucose measurement

Glucose levels were monitored every two weeks using a glucometer (Contour, Parsippany, NJ). Diabetes was determined when two consecutive blood glucose measurements were 250 mg/dL.

Bacterial culture and administration

P. histicola (MCI 001) was cultured using a tryptic soy broth (TSB) media under strictly anaerobic condition using a Bactron anaerobic chamber (SHELDON MANUFACTURING, INC, USA). The gas mixture was N2 (85–90%), H2 (5%) and CO2 (5–10%). The culture conditions were 37 °C for 48 h, with a pH of 7.2 ± 0.2. The purity of the bacterial culture was frequently checked, as published previously [30]. For administration to the mice by oral gavage, the bacterial concentration was 109 CFU mL-1, where each mouse received 100 μL of culture containing approximately 108 CFU of the bacterium. Administration of the prepared P. histicola culture to the mice by gavage was done every other day, as previously described [15].

Anti insulin IgG

The measurement of anti insulin IgG by ELISA was performed as described before [8].

Histopathology

Sections of pancreas were formalin fixed and snap frozen in OCT (optimal cutting temperature compound from Tissue Tek, Sakura). Duodenal sections were taken from NOD mice 18 h after treatment with P. histicola and snap frozen. Formalin fixed pancreatic tissue was paraffin embedded and one section stained with hematoxylin and eosin and scored for cellular infiltration of all the islets in the section, based on a score of 0–3. We did not isolate the islets from the pancreas in order to evaluate 35 different islets from each mouse pancreas in order to do a highly rigorous analysis of the islets for insulitis and cell markers by immunhistoochemistry as was done by Koide et al. and Inoue et al. [31, 32].

For immunohistochemistry of frozen tissue (IHF), frozen OCT blocks were cryosectioned and one to two sequential sections stained with the following fluorochrome conjugated antibodies (Fitc anti mouse CD3, Fitc anti mouse CD4, Percp anti mouse CD8, APC anti mouse FoxP3, and Fitc anti mouse B220). All conjugated antibodies were purchased from Becton Dickinson. Unconjugated anti mouse NKp46 was purchased from US Biological, and unconjugated anti mouse ZO-1 was purchased from Invitrogen. The secondary antibody for anti mouse ZO-1 was Fitc anti rabbit IgG and the secondary for anti NKp46 was AF594 anti rabbit IgG, both of which were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch. All frozen immunohistochemistry was evaluated on a confocal laser microscope (Zeiss LSM 780), analyzed using Zen Black software, and then scored on a scale of 0–3, similar to the H&E staining.

Regulatory T cells by FACs analysis

After sacrifice, the pancreatic draining lymph nodes, the mesenteric lymph nodes, Peyer’s patches, and splenocytes were extracted and stained with, Fitc anti mouse CD25, PE anti mouse CD4, and APC anti FoxP3 and then analyzed by flow cytometry. All antibodies were purchased from Becton Dickinson. Analysis was done using FlowJo software. For the analysis of Tregs, cells were gated first on CD4+ cells, then the percentages of CD25 + FoxP3+ cells were obtained (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Cytokine transcription

Segments of duodenum were extracted from NOD mice that were sacrificed 18 h after treatment with P. histicola and snap frozen. RNA was extracted using the RNAEasy Plus mini kit from Qiagen. cDNA was generated using a Superscript III reverse transcriptase kit from Invitrogen (Thermo Fisher), and semi-quantitative RTPCR done using Sybr Green master mix from Life Technologies (Thermo Fisher) on an ABI-ViiA-7 RT-PCR machine by Applied BioSystems. The specific primers used are previously published [33].

16 s microbiome

Fresh stool pellets were collected at the start of the study (baseline) and periodically throughout the experiments. Fecal DNA was extracted using the Mo-Bio PowerSoil extraction kit (Qiagen) with a bead beating step as well as an incubation period for optimal yield. Reverse primer barcodes were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT, Coralville, Iowa) and ordered as HPLC purified oligos, targeting V3-V5 regions of the 16 s ribosomal RNA gene. DNA was amplified using 357 Forward primer and reverse primer barcodes specified by Illumina as done previously [8]. Extracted DNA underwent 25 cycles on the PCR and both amplicons and generated libraries were quantitated with a Qubit 3.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher). Libraries were sequenced using Illumina MiSeq machines at Mayo Clinic and at the University of MN. All sequencing files were run through the Tornado pipeline at Mayo Clinic [34].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were done using Excel, SAS, and GraphPad Prism.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Figure S1: Incidence of diabetes. Additional controls of water alone (sham gavage n=7 ) and bacterial media alone (n=7) are included. The delayed onset by P. histicola was significant (p<0.0001 Gray K-Sample)

Additional file 2: Supplementary Figure S2: H&E staining of Pancreas at 5 weeks and 7 weeks of treatment. Hematoxylin and eosin stained pancreata from female NOD mice administered P. histicola for 5 weeks (11 weeks of age) and 7 weeks (13 weeks of age) were evaluated for inflammation on a score from 0 to 3. P. histicola treatment did not significantly decrease the inflammation of the pancreas score in either the 5 weeks of treatment (p=0.4) or the 7 weeks of treatment (p=0.5).

Additional file 3: Supplementary Figure S3: Immunofluorescent IHC of the pancreas for CD4, FoxP3, CD8, and B220. Pancreata from female NOD mice administered P. histicola for 3 weeks (9 weeks of age) were evaluated for CD4, FoxP3, and B220, and mice administered P. histicola for 5 weeks (11 weeks of age) were evaluated for CD4, FoxP3, CD8, and B220.

Additional file 4: Supplementary Figure S4: Flow cytometry gating for regulatory T cells. Using data gathered from flow cytometry analysis and FloJo software, cells were first gated on CD4+ cells. A dot plot with CD25 and Foxp3 on the axes was then generated.

Acknowledgements

We are very appreciative of the Optical Microscopy Core Facility of the Mayo Clinic Center for Cell Signaling in Gastroenterology for providing us the use of their LSM 780 confocal laser microscope, which is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P30DK084567. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- T1D

Type 1 diabetes

- NOD

Non-obeses diabetic

- CIA

Collagen induced arthritis

- EAE

Experimental encephalomyelitis

- P. histicola

Prevotella histicola

- H&E

Hematoxylin and eosin

- NK

Natural killer

- FACS

Fluorescence activated cell sorting

- OTU

Operational taxonomic unit

- TSB

Tryptic soy broth

- CFU

Colony forming unit

- IHF

Immunohistochemistry frozen

- OCT

Optimal cutting temperature compound

- HPLC

High performance liquid chromatography

Authors’ contributions

EM, AM, VT, and JM designed the experiments and study. EM, IH, SM, SK, EN, DL, and BB conducted the experiments and collected the samples. EM, AM, RC, VT, and JM analyzed and interpreted the data. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

Funding for this project was provided by Mayo Clinic in support of JM; this funding supported the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data as well as the writing of the manuscript. Funding for the use of the LSM 780 confocal laser microscope in order to collect the image data for the manuscript was provided by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P30DK084567.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated in the current study are available in the NCBI BioProject database, accession # PRJNA785662.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All studies were approved by the Mayo Clinic IACUC (Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee). All mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Consent to Participate: Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors EM, AM, VT, and JM are co-inventors on US patent #10555975B2.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Patterson CC, Dahlquist GG, Gyurus E, Green A, Soltesz G, Group ES Incidence trends for childhood type 1 diabetes in Europe during 1989-2003 and predicted new cases 2005-20: a multicentre prospective registration study. Lancet. 2009;373(9680):2027–2033. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60568-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green A, Patterson CC, Europe ETSG. Diabetes: trends in the incidence of childhood-onset diabetes in Europe 1989-1998. Diabetologia. 2001;44(Suppl 3):B3–B8. doi: 10.1007/PL00002950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marigliano M, Tadiotto E, Morandi A, Sabbion A, Contreas G, Avossa F, Fedeli U, Maffeis C. Epidemiology of type 1 diabetes mellitus in the pediatric population in Veneto region, Italy. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2015;107(3):e19–e21. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Higuchi BS, Rodrigues N, Gonzaga MI, Paiolo JCC, Stefanutto N, Omori WP, Pinheiro DG, Brisotti JL, Matheucci E, Jr, Mariano VS, et al. Intestinal Dysbiosis in autoimmune diabetes is correlated with poor glycemic control and increased Interleukin-6: a pilot study. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1689. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang Y, Li SC, Hu J, Ruan HB, Guo HM, Zhang HH, Wang X, Pei YF, Pan Y, Fang C. Gut microbiota profiling in Han Chinese with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;141:256–263. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2018.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mejia-Leon ME. Calderon de la Barca AM: perinatal factors and type 1 diabetes-associated dysbiosis in Mexican infants. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 2015;72(5):333–338. doi: 10.1016/j.bmhimx.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wen L, Ley RE, Volchkov PY, Stranges PB, Avanesyan L, Stonebraker AC, Hu C, Wong FS, Szot GL, Bluestone JA, et al. Innate immunity and intestinal microbiota in the development of type 1 diabetes. Nature. 2008;455(7216):1109–1113. doi: 10.1038/nature07336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marietta EV, Gomez AM, Yeoman C, Tilahun AY, Clark CR, Luckey DH, Murray JA, White BA, Kudva YC, Rajagopalan G. Low incidence of spontaneous type 1 diabetes in non-obese diabetic mice raised on gluten-free diets is associated with changes in the intestinal microbiome. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e78687. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Livanos AE, Greiner TU, Vangay P, Pathmasiri W, Stewart D, McRitchie S, Li H, Chung J, Sohn J, Kim S, et al. Antibiotic-mediated gut microbiome perturbation accelerates development of type 1 diabetes in mice. Nat Microbiol. 2016;1(11):16140. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kemppainen KM, Vehik K, Lynch KF, Larsson HE, Canepa RJ, Simell V, Koletzko S, Liu E, Simell OG, Toppari J, et al. Association between early-life antibiotic use and the risk of islet or celiac disease autoimmunity. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(12):1217–1225. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.2905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mikkelsen KH, Knop FK, Vilsboll T, Frost M, Hallas J, Pottegard A. Use of antibiotics in childhood and risk of type 1 diabetes: a population-based case-control study. Diabet Med. 2017;34(2):272–277. doi: 10.1111/dme.13262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clausen TD, Bergholt T, Bouaziz O, Arpi M, Eriksson F, Rasmussen S, Keiding N, Lokkegaard EC. Broad-Spectrum antibiotic treatment and subsequent childhood type 1 diabetes: a Nationwide Danish cohort study. PLoS One. 2016;11(8):e0161654. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dominguez-Bello MG, Costello EK, Contreras M, Magris M, Hidalgo G, Fierer N, Knight R. Delivery mode shapes the acquisition and structure of the initial microbiota across multiple body habitats in newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(26):11971–11975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002601107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsuzaki T, Nagata Y, Kado S, Uchida K, Kato I, Hashimoto S, Yokokura T. Prevention of onset in an insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus model, NOD mice, by oral feeding of Lactobacillus casei. APMIS. 1997;105(8):643–649. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1997.tb05066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marietta EV, Murray JA, Luckey DH, Jeraldo PR, Lamba A, Patel R, Luthra HS, Mangalam A, Taneja V. Suppression of inflammatory arthritis by human gut-derived Prevotella histicola in humanized mice. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(12):2878–2888. doi: 10.1002/art.39785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mangalam A, Shahi SK, Luckey D, Karau M, Marietta E, Luo N, Choung RS, Ju J, Sompallae R, Gibson-Corley K, et al. Human gut-derived commensal Bacteria suppress CNS inflammatory and demyelinating disease. Cell Rep. 2017;20(6):1269–1277. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mejia-Leon ME, Petrosino JF, Ajami NJ, Dominguez-Bello MG, de la Barca AM. Fecal microbiota imbalance in Mexican children with type 1 diabetes. Sci Rep. 2014;4:3814. doi: 10.1038/srep03814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murri M, Leiva I, Gomez-Zumaquero JM, Tinahones FJ, Cardona F, Soriguer F, Queipo-Ortuno MI. Gut microbiota in children with type 1 diabetes differs from that in healthy children: a case-control study. BMC Med. 2013;11:46. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krych L, Nielsen DS, Hansen AK, Hansen CH. Gut microbial markers are associated with diabetes onset, regulatory imbalance, and IFN-gamma level in NOD mice. Gut Microbes. 2015;6(2):101–109. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2015.1011876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu Y, Peng J, Li F, Wong FS, Wen L. Evaluation of different mucosal microbiota leads to gut microbiota-based prediction of type 1 diabetes in NOD mice. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):15451. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-33571-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y, Dong W, Zhang Y, Caligiuri MA, Yu J. Dependence of innate lymphoid cell 1 development on NKp46. PLoS Biol. 2018;16(4):e2004867. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2004867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turchinovich G, Ganter S, Barenwaldt A, Finke D. NKp46 calibrates Tumoricidal potential of type 1 innate lymphocytes by regulating TRAIL expression. J Immunol. 2018;200(11):3762–3768. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1701333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gur C, Porgador A, Elboim M, Gazit R, Mizrahi S, Stern-Ginossar N, Achdout H, Ghadially H, Dor Y, Nir T, et al. The activating receptor NKp46 is essential for the development of type 1 diabetes. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(2):121–128. doi: 10.1038/ni.1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lagkouvardos I, Lesker TR, Hitch TCA, Galvez EJC, Smit N, Neuhaus K, Wang J, Baines JF, Abt B, Stecher B, et al. Sequence and cultivation study of Muribaculaceae reveals novel species, host preference, and functional potential of this yet undescribed family. Microbiome. 2019;7(1):28. doi: 10.1186/s40168-019-0637-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Candon S, Perez-Arroyo A, Marquet C, Valette F, Foray AP, Pelletier B, Milani C, Ventura M, Bach JF, Chatenoud L. Antibiotics in early life alter the gut microbiome and increase disease incidence in a spontaneous mouse model of autoimmune insulin-dependent diabetes. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0125448. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jia L, Shan K, Pan LL, Feng N, Lv Z, Sun Y, Li J, Wu C, Zhang H, Chen W et al: Clostridium butyricum CGMCC0313.1 Protects against Autoimmune Diabetes by Modulating Intestinal Immune Homeostasis and Inducing Pancreatic Regulatory T Cells. Front Immunol 2017, 8:1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Balakrishnan B, Luckey D, Bodhke R, Chen J, Marietta E, Jeraldo P, Murray J, Taneja V. Prevotella histicola protects from arthritis by expansion of Allobaculum and augmenting butyrate production in humanized mice. Front Immunol. 2021;12:609644. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.609644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gomez A, Luckey D, Yeoman CJ, Marietta EV, Berg Miller ME, Murray JA, White BA, Taneja V. Loss of sex and age driven differences in the gut microbiome characterize arthritis-susceptible 0401 mice but not arthritis-resistant 0402 mice. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e36095. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richer MJ, Lavallee DJ, Shanina I, Horwitz MS. Immunomodulation of antigen presenting cells promotes natural regulatory T cells that prevent autoimmune diabetes in NOD mice. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e31153. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Balakrishnan B, Luckey D, Marietta E, Karau M, Patel R, Murray J, Taneja V. Development of a real-time PCR method for quantification of Prevotella histicola from the gut. Anaerobe. 2017;48:37–41. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2017.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koide Y, Kaidoh T, Yanagawa T, Yoshida TO A comparative study on T cell receptor V beta gene usages: spleen cells from the non-obese diabetic (NOD) mouse and its non-diabetic sister strain, the ILI mouse, and infiltrating T cells into pancreata of NOD mice. Microbiol Immunol. 1993;37(8):653–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1993.tb01688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Inoue Y, Kaifu T, Sugahara-Tobinai A, Nakamura A, Miyazaki J, Takai T. Activating fc gamma receptors participate in the development of autoimmune diabetes in NOD mice. J Immunol. 2007;179(2):764–774. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mangalam AK, Luo N, Luckey D, Papke L, Hubbard A, Wussow A, Smart M, Giri S, Rodriguez M, David C. Absence of IFN-gamma increases brain pathology in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis-susceptible DRB1*0301.DQ8 HLA transgenic mice through secretion of proinflammatory cytokine IL-17 and induction of pathogenic monocytes/microglia into the central nervous system. J Immunol. 2014;193(10):4859–4870. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jeraldo P, Kalari K, Chen X, Bhavsar J, Mangalam A, White B, Nelson H, Kocher JP, Chia N. IM-TORNADO: a tool for comparison of 16S reads from paired-end libraries. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e114804. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Supplementary Figure S1: Incidence of diabetes. Additional controls of water alone (sham gavage n=7 ) and bacterial media alone (n=7) are included. The delayed onset by P. histicola was significant (p<0.0001 Gray K-Sample)

Additional file 2: Supplementary Figure S2: H&E staining of Pancreas at 5 weeks and 7 weeks of treatment. Hematoxylin and eosin stained pancreata from female NOD mice administered P. histicola for 5 weeks (11 weeks of age) and 7 weeks (13 weeks of age) were evaluated for inflammation on a score from 0 to 3. P. histicola treatment did not significantly decrease the inflammation of the pancreas score in either the 5 weeks of treatment (p=0.4) or the 7 weeks of treatment (p=0.5).

Additional file 3: Supplementary Figure S3: Immunofluorescent IHC of the pancreas for CD4, FoxP3, CD8, and B220. Pancreata from female NOD mice administered P. histicola for 3 weeks (9 weeks of age) were evaluated for CD4, FoxP3, and B220, and mice administered P. histicola for 5 weeks (11 weeks of age) were evaluated for CD4, FoxP3, CD8, and B220.

Additional file 4: Supplementary Figure S4: Flow cytometry gating for regulatory T cells. Using data gathered from flow cytometry analysis and FloJo software, cells were first gated on CD4+ cells. A dot plot with CD25 and Foxp3 on the axes was then generated.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated in the current study are available in the NCBI BioProject database, accession # PRJNA785662.