Abstract

Background

Around 16% of adults have symptoms of overactive bladder (urgency with frequency and/or urge incontinence). The prevalence increases with age. Anticholinergic drugs are commonly used to treat this condition.

Objectives

To determine the effects of anticholinergic drugs for the treatment of overactive bladder syndrome.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Incontinence Group Specialised Trials Register (searched 14 June 2005) and the reference lists of relevant articles.

Selection criteria

Randomised or quasi‐randomised trials in adults with overactive bladder syndrome that compared an anticholinergic drug with placebo treatment or no treatment.

Data collection and analysis

Two reviewer authors independently assessed eligibility, trial quality and extracted data. Data were processed as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2005).

Main results

Sixty ‐one trials, 42 with parallel‐group designs and 19 crossover trials were included (11,956 adults). Most trials were described as double‐blind but were variable in other aspects of quality. The crossover trials did not present data in a way that allowed inclusion in the meta‐analysis. Nine medications were tested: darifenacin; emepronium bromide or carrageenate; oxybutynin; propiverine; propantheline; tolterodine; trospium chloride; and solifenacin. One trial included the newer, slow release formulation of tolterodine.

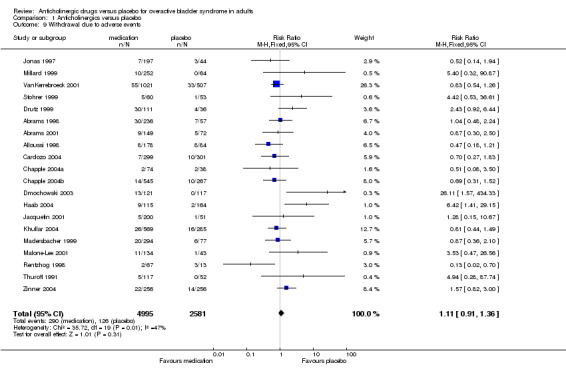

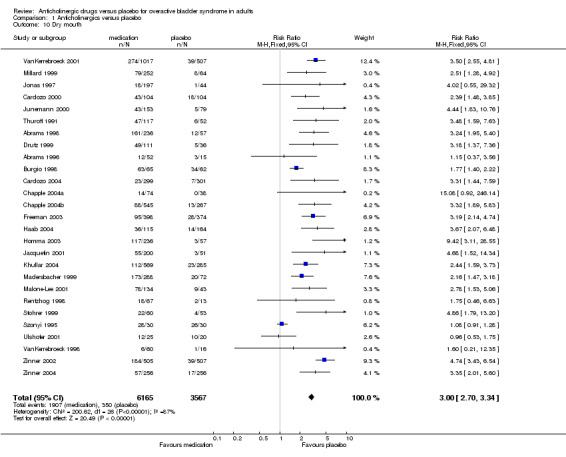

At the end of the treatment period, cure or improvement (relative risk (RR) 1.39, 95%CI 1.28 to 1.51), difference in leakage episodes in 24 hours (weighted mean difference (WMD) ‐0.54; 95% CI ‐0.67 to ‐0.41) and difference in number of voids in 24 hours (WMD ‐0.69; 95%CI ‐0.84 to ‐0.54) were statistically significant favouring medication. Statistically significant but modest sized improvements in quality of life scores were reported in recently completed trials. There was three times the rate of dry mouth in the medication group (RR 3.00 95% CI 2.70 to 3.34) but no statistically significant difference in withdrawal (RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.36). Sensitivity analysis, while limited by small numbers of trials, showed little likelihood that the effects were modified by age, sex, diagnosis, or choice of drug.

Authors' conclusions

The use of anticholinergic drugs by people with overactive bladder syndrome results in statistically significant improvements in symptoms. Recent trials suggest that this is associated with modest improvement in quality of life. Dry mouth is a common side effect of therapy but did not seem to have an effect on the numbers of withdrawals. It is not clear whether any benefits are sustained during long‐term treatment or after treatment stops.

Plain language summary

Anticholinergic drugs in patients with overactive bladder syndrome.

An overactive bladder is a condition in which bladder contracts suddenly without any control, resulting in feeling to urinate and or leakage of urine. This is a common condition in adults and is also called as 'irritable' bladder or detrusor instability, urge or urgency‐frequency syndrome. Overactive bladder becomes more common with advancing age. Anticholinergic drugs mainly by their muscle relaxant action can help adults with symptoms of urinary frequency, urgency and urge incontinence.

The review of trials found that on average people taking anticholinergic medication had about five less trips to the toilet and four less leakage episodes every week, with modest improvements in quality of life. About one in three people taking the drugs reported a dry mouth.

Background

According to the International Continence Society (ICS) "urgency, with or without urge incontinence, usually with frequency and nocturia, can be described as overactive bladder (OAB) syndrome, urge syndrome or urgency‐frequency syndrome. These terms can be used if there is no proven infection or obvious pathology" (Abrams 2002). The symptom complex do not represent and is not specific to a single disease, hence ICS definition can be debatable. Nevertheless, this term (OAB) has been commonly used in the literature.

People with overactive bladder syndrome report urgency (with or without urge incontinence), usually in combination with frequency and or nocturia. To be called overactive bladder syndrome these symptoms should not be caused by metabolic problems such as diabetes, or problems with the urinary tract such as urinary tract infection. However, people with neurological causes of overactive bladder symptoms are not excluded from the diagnosis. Overactive bladder syndrome may also be called urge syndrome or urgency‐frequency syndrome.

Urgency is the sudden and compelling desire to pass urine, which is difficult to defer. Sometimes there is involuntary leakage of urine with the feeling of urgency, and this is called urge urinary incontinence. Urgency and urge urinary incontinence usually result from an involuntary increase in bladder pressure due to detrusor (bladder smooth muscle) over‐activity. If further investigation of urgency/urge incontinence with urodynamics demonstrates spontaneous or provoked detrusor muscle contraction in the filling phase of the test then detrusor overactivity is diagnosed. If there is no defined cause for the overactivity this is called idiopathic (no known cause) detrusor overactivity but if there is a relevant neurological condition then the term neurogenic detrusor overactivity or detrusor hyperreflexia is used.

Frequency is the complaint of needing to void often during the day or at night. In clinical practice a person who voids more than eight times in 24 hours is considered to have frequency. If a person wakes more than once at night from sleep to void this is called nocturia.

Frequency, urgency, urge urinary incontinence, or the combination of these symptoms, are a common problem amongst adults living in the community. In a survey (telephone or face to face interviews) of 16,776 randomly selected adults aged 40 years or more, in six European countries, 16.6% reported overactive bladder symptoms (Milsom 2001). Similarly a telephone survey of 5204 people aged 18 years and over in the USA found that the prevalence of self reported overactive bladder symptoms was 16.6% (Stewart 2001). In a sample of 2369 adults from 11 Asian countries the prevalence of overactive bladder was 44.9% (Moothy 2001). A survey of 2005 adults in Korea found a prevalence of overactive bladder of 30.5% (Choo 2001). In a telephone survey of 819 Hong Kong Chinese aged 10‐90 years, 19% reported frequency and 15% complained of urge and/or urge incontinence (Brieger 1996). It is not clear why there are such marked differences in prevalence between some of the Asian studies and those from the USA or Europe. The differences may be real or due to different definitions. Several large population studies have reported that the prevalence of overactive bladder symptoms increases with age in men and women (Brown 1999; Milsom 2001; Moller 2000; Stewart 2001; Ueda 2000). In people with neurological conditions such as multiple sclerosis, urinary dysfunction appears to be more common than in the neurologically unimpaired population: the most frequently reported problems are frequency and/or urgency (Hennessey 1999).

Research on the amount of bother caused by overactive bladder syndrome, and the effect on quality of life, is now underway. It seems that frequency and/or urgency might can be just as bothersome as actual leakage (Milsom 2001), and overall the effects of overactive bladder symptoms on quality of life are marked (Jackson 1997). It also seems clear that many of the people affected by overactive bladder symptoms do not seek help from health care professionals (Milsom 2001; Ueda 2000).

Treatment of overactive bladder syndrome

The two main treatment options for overactive bladder syndrome are conservative management (for example bladder training, electrical stimulation) and pharmacotherapy or a combination of both. A separate Cochrane review on bladder training is available (Wallace 2004) and the scope of the current review is confined to drug treatment.

While the pathophysiology of the overactive bladder remains to be fully elucidated, the involvement of the autonomic nervous system in detrusor function is recognised (de Groat 1997). The motor nerve supply to the bladder is via the parasympathetic nervous system (via sacral nerves: S2,3,4) (Abrams 1988; Ouslander 1982; Ouslander 1986) which effects detrusor muscle contraction. This is mediated by acetylcholine acting on muscarinic receptors at the level of the bladder. Muscarinic receptors are found in other parts of the body too, for example in the gut, salivary glands and tear ducts. Pharmacotherapy relies on the use of drugs with anticholinergic properties. The rationale for using anticholinergic drugs in the treatment of overactive bladder syndrome is to block the parasympathetic acetylcholine pathway and thus abolish or reduce the intensity of detrusor muscle contraction. Unfortunately, none of the anticholinergic drugs that are available to date are specific to the muscarinic receptors in the bladder. As a result, the drugs can cause side effects by acting in other parts of the body too; these include dry mouth or eyes, constipation or nausea.

For the purpose of this review the term 'anticholinergic medications' refers to all medications with primary anticholinergic properties that are given specifically for bladder symptoms. Medications with secondary anticholinergic effects, for example tricyclic antidepressants have been excluded.

The number of anticholinergic drugs available on the market is increasing and various studies, observational and randomised controlled trials exist which evaluate effectiveness (for example Thuroff 1991; VanKerrebroeck 1998). However, uncertainty still exists as to whether anticholinergic drugs are effective and, if so, which ones and by what route of administration. There is also uncertainty about the role of anticholinergic drugs in different patient groups (for example the elderly, male and female). Despite these uncertainties, anticholinergics are increasingly being used in primary and secondary care settings for the treatment of overactive bladder syndrome, and this has considerable resource implications (Kobelt 1997).

There are many studies of the effects of anticholinergic drugs and four Cochrane reviews will consider them. This review compares anticholinergic drugs with no treatment or placebo treatment. Three other reviews consider: 1) whether different anticholinergic drugs have different effects (Hay‐Smith 2005); 2) whether anticholinergic drugs are better than other active non‐drug therapies (Alhasso 2006); and 3) whether anticholinergic drugs are better than other drug treatments (Dublin 2004). Two meta‐analyses of an anticholinergic drug (tolterodine) versus placebo have been published (Appell 1997; Larsson 1999). However, neither of these publications provides an adequate systematic review of the available trials comparing anticholinergic drugs with placebo or no treatment. Neither publication reports the objectives of the systematic review, a search strategy, inclusion and exclusion criteria for trials or the methods of data extraction and analysis. It appears that these meta‐analyses combine the results of pharmaceutical company funded phase II (Larsson 1999) and phase III (Appell 1997) trials of tolterodine versus placebo. A recent systematic review (Chapple 2005b) assessed the variation in the effects of different anticholinergic drugs. This second‐level question has been addressed in a separate Cochrane review (Hay‐Smith 2005) that focused on the safety and effectiveness of anticholinergics as a generic group.

This is an updated version of the present review. The first version was published in The Cochrane Library in 2002 (Issue 3).

Objectives

To determine the effects of anticholinergic drugs compared with placebo or no treatment in the treatment of overactive bladder syndrome.

The following hypothesis will be addressed.

Anticholinergic drugs are better than placebo or no treatment in the management of overactive bladder syndrome.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials of anticholinergic drugs versus placebo or no treatment of overactive bladder syndrome.

Types of participants

All adult men and women with a symptomatic diagnosis of overactive bladder syndrome or a urodynamic diagnosis of detrusor overactivity (either idiopathic or neurogenic), or both.

Types of interventions

At least one arm of the study had to use an anticholinergic drug and one other was a placebo or no treatment arm. To be included, the drug had to be a muscarinic anticholinergic antagonist given for the purpose of decreasing symptoms of overactive bladder. The group of drugs included: emepronium bromide or carrageenate, darifenacin, dicyclomine chloride, oxybutynin chloride, propantheline bromide, propiverine, tolterodine, and trospium chloride. Terodiline, an anticholinergic drug previously used in the treatment of overactive bladder, was excluded because it has been withdrawn from the market. Trials with intravesical anticholinergic medication administration were excluded in this updated version of the review.

Other drugs with less direct anticholinergic effects were also excluded, (for example smooth muscle relaxants, flavoxate hydrochloride, calcium channel blockers, potassium channel openers, beta‐adrenoceptor agonists, alpha‐adrenoceptor antagonists, prostaglandin synthetase inhibitors, and tricyclic antidepressants).

Types of outcome measures

Both subjective and objective outcome measures were included in this review.

Primary outcomes of interest:

A. Patient observations, e.g. symptom scores, perception of cure or improvement, satisfaction with outcome

B. Quantification of symptoms, e.g. number of leakage episodes, frequency and volume (urinary diary)

Secondary outcomes of interest:

C. Quality of life general (e.g. SF36) and condition‐specific quality of life measures (e.g. Incontinence Impact Questionnaire, King's Health Questionnaire) and psychosocial measures.

D. Socioeconomics direct and indirect costs of interventions (for patients and providers), resource implications of differences in outcome, formal economic analysis (e.g. cost effectiveness, cost utility) and desire or need for further treatment.

E. Other, e.g. adverse events, withdrawal or compliance measures, long‐term follow‐up and any other outcome not pre‐specified but judged important when performing the review.

Search methods for identification of studies

Relevant trials were identified from the Cochrane Incontinence Group's Specialised Register of controlled trials, which is described under the Group's details in The Cochrane Library (Please see the ‘Specialized Register’ section of the Group’s module in The Cochrane Library). In addition, the reference lists of identified trials were searched. The register contains trials identified from MEDLINE, CINAHL, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and handsearching of journals and conference proceedings. Date of the most recent search of the register: 14 June 2005.

The trials in the Incontinence Group Specialised Trials Register are also contained in CENTRAL.

The Incontinence Group Trials Register was searched using the Group's own keyword system. The search terms used were:

{design.rct* or design.cct*} AND{ TOPIC.URINE.INCON*} OR {TOPIC.URINE.overactivebladder.} AND{{ INTVENT.CHEM.DRUG.ANTICHOLINERGIC*} AND {INTVENT.CHEM.PLACEBO}} OR {relevant.review. anticholinergicVSplacebo} (All searches were of the keyword field of Reference Manager 9.5 N, ISI ResearchSoft).

Additional searches conducted for this review

• We checked the reference lists of identified trials and other relevant articles. We did not impose any language or other limits on any of the searches.

Data collection and analysis

Screening for eligibility

Trials under consideration for inclusion in the review were assessed independently for their appropriateness by two review authors without prior consideration of their results. Any disagreements that were unresolved by discussion were considered by a third person. Excluded studies were listed with reasons for their exclusion.

Assessment of methodological quality

The review authors independently made an assessment of methodological quality using the Incontinence Group's quality assessment tool, which includes evaluation of quality of random allocation and concealment, description of dropouts and withdrawals, analysis by intention to treat, and masking during treatment and at outcome assessment. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third person.

Data extraction

Data were independently abstracted by at least two review authors and cross‐checked. Where data were collected but were not reported, or were reported in a form not suitable for inclusion in the formal analysis, further clarification was sought from the trialists. In trials where different doses of the same drug were compared against placebo we used what is considered to be the therapeutic dose (for example solifenacin 5mg, tolterodine 2mg twice a day or 4mg once per day). When two different types of anticholinergics (for example tolterodine and solifenacin) were compared against placebo, the results from the two arms of anticholinergics were recalculated as a weighted average.

Data analysis

In trials with two or more active (anticholinergic drug) treatment arms, the data from the active treatments were combined, where possible for comparison with placebo. Included trial data were processed as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2005).

We intended, where possible, to calculate standardised effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals (CI): weighted mean differences (WMD) where outcomes were continuous variables and relative risks (RR) where they were binary. A fixed‐effect model was used to calculate the pooled estimates and the 95% CIs. The weighted mean differences were weighted by the inverse of the variance.

We combined data on number of episodes at the end of the treatment period with change from baseline scores for both leakage and micturition outcomes.

Cross‐over trials: in order to use the data from crossover trials in a meta‐analysis ideally it should be presented as the mean and standard deviation of the difference between two treatments for continuous data, or a two‐by‐two table for binary data, as the correlation between measurements on the same individual may be important. We did not attempt to include cross‐over trials in the meta‐analysis using the generic inverse variance method as there were large amounts of data available from the parallel‐group trials. The results from cross‐over trials were discussed narratively.

A priori sensitivity analyses were planned to investigate the effects of age, sex, severity of symptoms, cause of overactive bladder symptoms (that is idiopathic versus neurogenic) and type of medication.

Differences between trials were to be further investigated when it appeared obvious from visual inspection of the results, or statistically significant heterogeneity was found at the 10% probability level using the chi‐squared test or by assessment of the I‐squared statistic (Deeks 2005). If a reason was found then a judgement was to be made as to whether it was reasonable to combine the results. If there was no obvious reason for the heterogeneity, a random‐effects model could have been used. However, in the event this was not necessary.

Results

Description of studies

In this first update of the review (2006, Issue 4) fourteen extra trials were added (Cardozo 2004; Chapple 2004a: Chapple 2004b; Coombes 1996; Dmochowski 2003; Freeman 2003; Goode 2002; Haab 2004; Homma 2003; Khullar 2004; Landis 2004; Takayasu 1990; Zinner 2002; Zinner 2004). A total of sixty‐one trials are now included in the review. Thirty‐eight trials were excluded, including several abstracts with no useable data. The other reasons for exclusion are listed in the table 'Characteristics excluded studies'. Of the 61 trials included in the review, 42 were of a parallel‐group design and 19 of a crossover design.

In the parallel‐arm trials, 7822 participants were randomised to receive anticholinergic drugs and 4134 placebo medication. Three trials did not report the numbers randomised to each group (Chaliha 1998; Davila 2001; Tago 1990); and nine only reported the number after dropouts had been excluded (Abrams 1996; Cardozo 2004; Chapple 2004a; Dorschner 2000; Homma 2003; Junemann 1999; VanKerrebroeck 2001; Khullar 2004; Landis 2004). The crossover trials included 609 participants (63 known to be men and 402 known to be women); six crossover trials did not report the sex of the participants. Sample sizes ranged from 6 (Rosario 1995b) to 1529 (VanKerrebroeck 2001).

Three trials were published in German (Dorschner 2003a; Wehnert 1989; Wehnert 1992); one in Italian (Bono 1982); one in Flemish (Kramer 1987); one in Spanish (SerranoBrambila 2000) and one in Japanese (Takayasu 1990). All information and data were abstracted from the original paper.

Participant characteristics

Parallel‐arm trials

Inclusion or exclusion criteria. or both, were not always well described. People with a urodynamically determined or presumed diagnosis of idiopathic detrusor overactivity were included in 16 trials (Abrams 1998; Abrams 2001; Alloussi 1998; Burgio 1998; Chaliha 1998; Chapple 2004a; Jacquetin 2001; Jonas 1997; Homma 2003; Khullar 2004; Madersbacher 1999; Rentzhog 1998; Ulshofer 2001; VanKerrebroeck 2001; Wein 1978; Zinner 2004), and four trials restricted entry to those with neurogenic detrusor overactivity (Abrams 1996; Stohrer 1991; Stohrer 1999; VanKerrebroeck 1998;). Six trials included people with either idiopathic or neurogenic problems (Chapple 2004a;Chapple 2004b;Drutz 1999; Millard 1999; Tago 1990; Thuroff 1991); in the remaining trials participants had symptoms consistent with overactive bladder syndrome. Mean ages of the participants ranged from 30 years (no standard deviation (SD) given) to 82 years (SD 6.1) and five trials were restricted to older people (55 years and over, Burgio 1998; 60 years and over, Dorschner 2000; 60 years and over, Halaska 1994; 65 years and over, Malone‐Lee 2001; 70 years and over, Szonyi 1995). One trial reported data separately for people younger and older than 65 years of age (Zinner 2002). A common exclusion criterion was evidence of voiding dysfunction or bladder outlet obstruction, although in one trial inclusion was restricted to men with symptoms of bladder overactivity and bladder outlet obstruction (Abrams 2001).

Crossover trials

Six trials included people with urgency or urge incontinence (Bagger 1985; Coombes 1996; Kramer 1987; Wehnert 1989; Wehnert 1992; Zeegers 1987). These people usually had urodynamics performed as well but it was not one of the selection criteria. The other 14 crossover trials required a diagnosis of detrusor overactivity. One study was in spinal cord injured patients with detrusor hyperreflexia uncontrolled by oral anticholinergics (Di Stasi 2001a). Two trials recruited elderly people in institutions (Walter 1982; Zorzitto 1989) and one was confined to postmenopausal women (Tapp 1990). In the other trials the mean age ranged from 44 to 63 years, with four trials not reporting age. There was a variety of exclusion criteria.

Interventions

Parallel‐arm trials

In the majority of parallel‐group trials, intervention was preceded by run‐in periods of varying lengths and treatment with co‐medications was specifically an exclusion criterion, although for seven of the 42 included parallel arm trials this information was not reported (Burgio 1998; Chaliha 1998; Chapple 2004a; Homma 2003; Junemann 1999; Stohrer 1999; Tago 1990). All included trials were placebo controlled, and no trial made a comparison between an anticholinergic drug and no treatment.

Trials compared the following active treatments with placebo:

tolterodine (14 trials, Abrams 1996; Abrams 1998; Abrams 2001; Drutz 1999; Freeman 2003; Jacquetin 2001; Jonas 1997; Junemann 2000; Landis 2004; Malone‐Lee 2001; Millard 1999; Rentzhog 1998; VanKerrebroeck 1998; VanKerrebroeck 2001);

oxybutynin (eight trials, Abrams 1998; Burgio 1998; Drutz 1999; Goode 2002; Madersbacher 1999; Szonyi 1995; Thuroff 1991; Wein 1978);

trospium (eight trials, Alloussi 1998; Cardozo 2000; Chaliha 1998; Junemann 1999; Junemann 2000; Stohrer 1991; Ulshofer 2001; Zinner 2004), propiverine (five trials, Dorschner 2000; Halaska 1994; Madersbacher 1999; Stohrer 1999; Tago 1990);

propiverine (five trials, Dorschner 2000; Halaska 1994; Madersbacher 1999; Stohrer 1999; Tago 1990);

solifenacin (three trials, Chapple 2004a; Chapple 2004b; Cardozo 2004);

propantheline (two trials, Takayasu 1990; Thuroff 1991);

seven trials compared two different anticholinergic drugs with placebo:

Abrams 1998 tolterodine and oxybutynin; Dmochowski 2003 transdermal oxybutinin and oral tolterodine; Drutz 1999 tolterodine and oxybutynin; Homma 2003 extended release tolterodine and immediate release oxybutinin; Junemann 2000 tolterodine and trospium chloride; Madersbacher 1999 oxybutynin and propiverine; Thuroff 1991 oxybutynin and propantheline;

two trials compared different doses of the same anticholinergic medication (Chapple 2004a; Chapple 2004b);

length of treatment in most of the trials was 12 weeks (Abrams 1998; Cardozo 2004; Chapple 2004a; Chapple 2004b; Dmochowski 2003; Drutz 1999; Haab 2004; Homma 2003; Millard 1999; VanKerrebroeck 2001; Zinner 2004) with two thirds of trials choosing treatment periods of two to four weeks in duration. Some of the trials did not permit dose modification during study period (Homma 2003; Zinner 2002). Drug doses are described in the table 'Characteristics of included studies'.

Crossover trials

Some crossover trials were preceded by a week of a placebo washout period. The length of treatment varied from one dose to six weeks with a median length of three weeks. For the one dose study the washout period was three days. Eight of the nineteen trials had no washout period, and it was not clear in three more. The other washout periods varied from one week to one month. Given the short half life of the drugs, a washout period may not be important. Nine of the trials had two arms, seven had three arms and three had four arms. Some arms were the same drug at different doses. Some trials had different combinations of drugs so that they tested, for example, four drugs in a three arm study (Kramer 1987) and some had even more complicated arrangements (Massey 1986).

Eleven of the crossover trials used oxybutynin (Bono 1982; Di Stasi 2001a; Kramer 1987; Moisey 1980; Moore 1990; Murray 1984; Riva 1984; SerranoBrambila 2000; Tapp 1990; Zeegers 1987; Zorzitto 1989)

Seven emepronium ( Bagger 1985; Kramer 1987; Massey 1986; Meyhoff 1983; Murray 1984; Walter 1982; Zeegers 1987)

Two propiverine (Wehnert 1989; Wehnert 1992)

One penthienate( Coombes 1996)

Two darifenacin (Rosario 1995a; Rosario 1995b)

All trials but one (Di Stasi 2001a) used only oral administration of the drugs. Di Stasi used two methods of intravesical administration, one with an electric current, and oral administration.

Outcome measures

Overall, there was a lack of consistency in the types of outcome measures reported by trialists, and a lack of consistency in the way data were reported. Seven trials reported outcomes of interest but without useable data (Chaliha 1998; Di Stasi 2001a; Malone‐Lee 2001; Rosario 1995b; Stohrer 1991; Tago 1990; Wein 1978). Due to deficiencies in data reporting (for example point estimates without any measure of variation), many trials contributed only limited data to the review. The lack of similarity in measures reduced the possibilities for combining results from individual trials.

The primary outcomes of interest in the review were the patient observations (for example perception of cure or improvement) and quantification of symptoms (such as number of leakage episodes). Patient observations were rarely reported and in reading trial reports it does not appear that these data were often collected. Micturition diaries were commonly used to record numbers of leakage episodes and numbers of micturitions over varying lengths of time. In order to combine these data in a meta‐analysis, the number of leakage episodes and number of micturitions in 24 hours were calculated.

Urodynamic measures and adverse events were the two most commonly reported secondary outcomes of interest. A wide range of urodynamic measures were reported. In view of the lack of correlation between urodynamic measures and clinical outcome the data were not abstracted for this review.

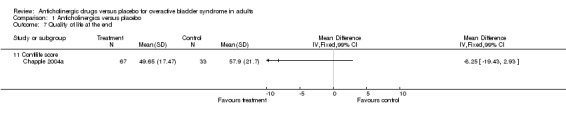

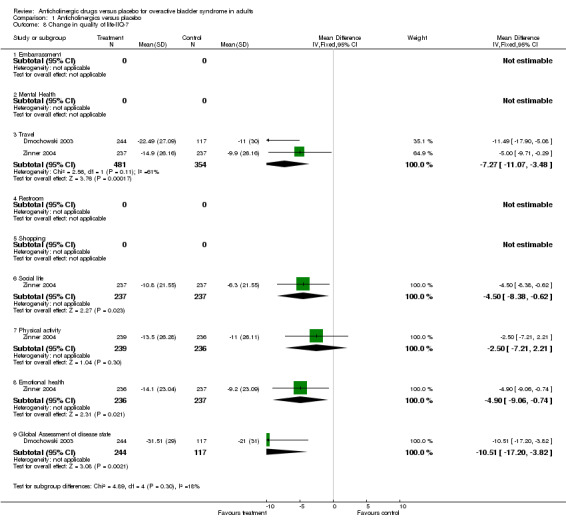

Measures of quality of life were reported in seven trials (Chapple 2004a; Dorschner 2000; Dmochowski 2003; Homma 2003; Khullar 2004; VanKerrebroeck 2001; Zinner 2004). Four studies (Chapple 2004a; Homma 2003; Khullar 2004; VanKerrebroeck 2001) used the King's Health Questionnaire (KHQ), two (Dmochowski 2003; Zinner 2004) used the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire (IIQ) and one used the Giessen Complaint Survey and Basle Subjective Wellbeing Study (Dorschner 2000). Chapple (Chapple 2004a) also reported on quality life using the Contilife score. `

In order to use the data from crossover trials in a meta‐analysis it must be presented as the mean and standard deviation of the difference between two treatments for continuous data, or a two‐by‐two table for binary data, as the correlation between measurements on the same individual may be important. Only two of the 19 crossover trials presented data in this way (Kramer 1987; Riva 1984) and then only for one outcome each, so the data could not be used in this way. The data were, therefore, discussed narratively and this is reported in the Results section after the analyses of the parallel‐arm trials. In studies, where medians were reported (Landis 2004; Zinner 2004), data could not be used in the meta‐analysis and were reported in separate data tables.

Further characteristics of the trials are reported in the table 'Characteristics of included studies'.

Risk of bias in included studies

The methodological quality of the published studies was assessed by looking at the methods of generation of random allocation, concealment of allocation, blinding of the trial participants and investigators, completeness of treatment, withdrawals and dropouts and loss to follow up.

Randomisation, allocation concealment and blinding

The method of group allocation was rarely described. Double blinding should adequately conceal group allocation but this is not guaranteed. For the purposes of the review, trials that stated group allocation was 'double‐blind' were coded as having adequate concealment. All trials but two (Wehnert 1989; Wehnert 1992) were double blind and therefore considered to have adequate allocation concealment.

Few trials specifically stated that outcome assessors were blind to group allocation (Burgio 1998; Goode 2002; Homma 2003). Some trials stated the code was broken at the completion of the study and in some it was specified as after the analysis. This would imply that the final measurement was done blinded. A recent study by DuBeau et al suggests that double‐blind designs might not be adequate to blind participants to anticholinergic versus placebo allocation, emphasising the importance of blinded outcome assessors (DuBeau 2000).

Baseline comparability of the groups was not mentioned in seven of the parallel‐group trials (Chaliha 1998; Goode 2002; Halaska 1994; Homma 2003; Junemann 1999; Junemann 2000; Wein 1978). The remaining 34 parallel‐group trials stated that the groups were comparable at baseline, although three trials did not provide supporting data (Abrams 2001; Cardozo 2000; Tago 1990). In 12 trials the evaluation of treatment efficacy was conducted on intention‐to‐treat principles (Abrams 1998; Burgio 1998; Cardozo 2000; Jacquetin 2001; Junemann 1999; Madersbacher 1999; Malone‐Lee 2001; Millard 1999; Szonyi 1995; VanKerrebroeck 2001; Wein 1978; Zinner 2002) and seven trials specifically stated that a per‐protocol analysis was used to assess treatment efficacy (Abrams 1996; Alloussi 1998; Dorschner 2000; Drutz 1999; Junemann 2000; Ulshofer 2001; VanKerrebroeck 1998). Baseline comparability is not an issue of concern for crossover trials.

Withdrawals and dropouts

The description of withdrawals or dropouts was not adequate in 11 trials (Abrams 1996; Bono 1982; Cardozo 2000; Chaliha 1998; Chapple 2004a; Chapple 2004b; Halaska 1994; Junemann 1999; Junemann 2000; Tago 1990; VanKerrebroeck 1998). There were no dropouts from the trials using single oral doses of medication (Di Stasi 2001a; Wein 1978) and in 17 trials the drop out rate was 10% or less (Bagger 1985; Dorschner 2000; Jacquetin 2001; Jonas 1997; Malone‐Lee 2001; Meyhoff 1983; Millard 1999; Murray 1984; Rosario 1995a; SerranoBrambila 2000; Stohrer 1991; Stohrer 1999; Thuroff 1991; Walter 1982; Wehnert 1989; Wehnert 1992; Zinner 2004). In the remainder of trials, drop‐out rates ranged from 12% (Madersbacher 1999; VanKerrebroeck 2001) to 21% (Drutz 1999; Szonyi 1995; Homma 2003) in parallel‐designs and 20% (Riva 1984) to 63% (Kramer 1987) in the crossover trials. Very few parallel design trials included any follow up beyond the initial assessment of outcome. In those trials that did follow up participants this was for short periods of time, that is one week (VanKerrebroeck 2001; Zinner 2002) or two weeks (Abrams 1998; Drutz 1999; Jacquetin 2001; Malone‐Lee 2001; Rentzhog 1998; Ulshofer 2001). Some trials did follow up participants longer term but this was not blinded and by this stage everyone had been offered active treatment. Long term follow up is not relevant for crossover trials: by the nature of their design crossover trials can only address short‐term effects during treatment.

The primary or only reference for nine of the 60 included trials was a conference abstract (Abrams 1996; Abrams 2001; Chaliha 1998; Junemann 1999; Junemann 2000; Murray 1984; Rosario 1995a; Rosario 1995b; Tago 1990) and all of these trials were complete at the time of reporting. Full publications were not found for any of these trials with subsequent searching. All abstracts reported limited details of methods, and few results.

Some of the large multi‐centre and multinational trials were reported in multiple publications. These publications usually presented subsets of the main trial results (for example data from one country) and subsequent publications rarely provided further methodological detail. The most notable example is VanKerrebroeck (VanKerrebroeck 2001); 14 separate reports were identified. Where there were multiple publications of the same trial a primary reference was selected and has been cited throughout the review for simplicity.

Effects of interventions

Primary outcome measures (outcomes 01.01 to 01.05)

A. Patient observations, for example symptom scores, perception of cure or improvement, satisfaction with outcome (outcome 01.01)

Parallel‐arm trials

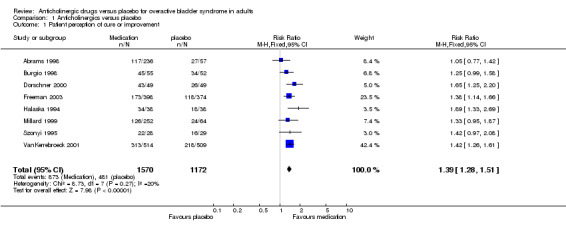

Patients' perception of change in symptoms were reported in eight trials (Abrams 1998; Burgio 1998; Dorschner 2000; Freeman 2003; Halaska 1994; Millard 1999; Szonyi 1995; VanKerrebroeck 2001). Those taking medication were more likely to report cure or improvement in their symptoms than those taking placebo (873 out of 1570, 56% cured or improved in medication group; and 481 out of 1172, 41% cured or improved in placebo group); relative risk (RR) for cure or improvement 1.39 (95% CI 1.28 to 1.51, outcome 01.01). There was no statistically significant heterogeneity.

Some form of patient‐reported outcome was used in eight further trials but these data could not be included in the meta‐analysis because they were not dichotomous or could not be dichotomised by the review authors (Cardozo 2000; Drutz 1999; Rentzhog 1998; Stohrer 1999; Tago 1990; Thuroff 1991; VanKerrebroeck 1998).

Crossover trials

Eight crossover trials reported this outcome (Bagger 1985; Kramer 1987; Moore 1990; SerranoBrambila 2000; Walter 1982; Wehnert 1989; Wehnert 1992; Zeegers 1987), all in a different way. In all trials the patient preference was in favour of anticholinergic drugs.

B. Quantification of symptoms, for example number of leakage episodes, frequency and volume (urinary diary) (outcomes 01.02 to 01.05)

Parallel ‐arm trials

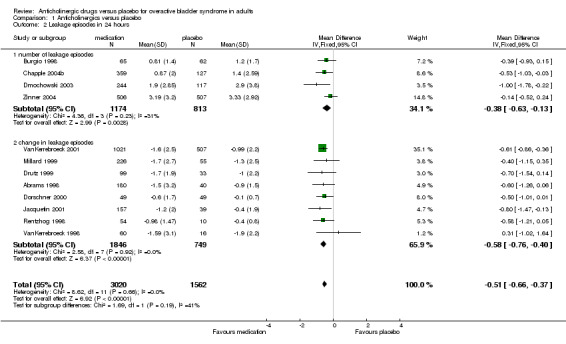

Three trials (Burgio 1998; Chapple 2004b; Dmochowski 2003) reported the number of leakage episodes in 24 hours after treatment. Chapple and Dmochowski also reported change data but this data was not entered in the analysis, only data for average number of leakage episodes in 24 hours after treatment was used. One trial (Zinner 2002) reported number of leakage episodes per week and this was converted to data for 24 hours and combined with the other three trials. Those in the anticholinergic drug groups had approximately 0.38 leakage episodes less per 24 hours than those taking placebo medication (WMD for leakage episodes in 24 hours ‐0.38, 95% CI ‐0.63 to ‐0.13, P=0.003, outcome 01.02).

Ten trials reported the change in number of leakage episodes at the end of treatment, measured over a 24 hour period (Abrams 1998; Chapple 2004b; Dmochowski 2003; Dorschner 2000; Drutz 1999; Jacquetin 2001; Millard 1999; Rentzhog 1998; VanKerrebroeck 1998; VanKerrebroeck 2001). All except one showed greater reduction in leakage episodes in the anticholinergic group (WMD ‐0.58; 95% CI ‐ 0.76 to 0.40 P<0.00001 outcome 01.02). When the two subgroups are combined (number of leakage episodes in 24 hours and change in leakage episodes) the result (WMD ‐0.51; 95% CI ‐0.66 to ‐0.37) shows on average a reduction in leakage episodes of around three to five per week. Zinner reported his result for change in leakage episode as percentages (other data table 1.03) also favouring treatment.

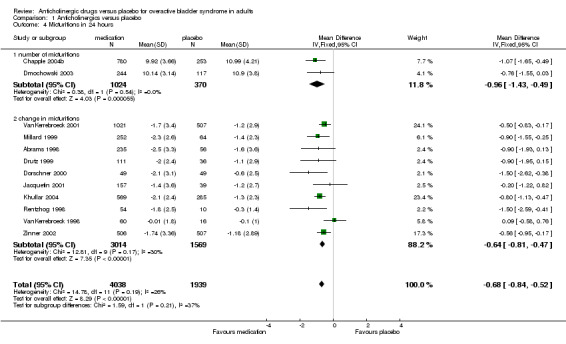

Data on number of micturitions were consistent with this (outcome 01.04). Two trials (Chapple 2004b; Dmochowski 2003) reported on number of micturitions in 24 hours (WMD ‐0.96; 95% CI ‐1.43 to ‐0.49) both studies also reported change data but this was not entered into the analysis. Twelve trials (Abrams 1998; Chapple 2004b; Dmochowski 2003; Dorschner 2000; Drutz 1999; Jacquetin 2001; Khullar 2004; Millard 1999; Rentzhog 1998; VanKerrebroeck 1998; VanKerrebroeck 2001; Zinner 2002) reported change in micturition at end of treatment, measured over 24 hours, the result favoured anticholinergic treatment (WMD ‐0.64 95% CI ‐0.81 to ‐0.47, outcome 01.04). When the two subgroups (micturitions in 24 hours and change in micturitions) are combined this translates to a WMD of ‐0.68 95% CI ‐0.84 to 0.52 i.e. around four to six fewer voids over one week compared with those taking placebo. Two trials (Landis 2004; Zinner 2004) which could not be included in the meta‐analysis as no standard deviations were reported, also found statistically significant differences favouring anticholinergics (other data table 01.05).

Crossover trials

Five crossover trials reported number of leakage episodes in some manner (Bagger 1985; Massey 1986; Meyhoff 1983; Riva 1984; Tapp 1990). In two of these, there was a clear‐cut result in favour of drugs (Massey 1986; Tapp 1990), with a dose response in Massey. Seven trials reported either the number of micturitions or the change in the number of micturitions from baseline (Bagger 1985; Kramer 1987; Massey 1986; Meyhoff 1983; Moore 1990; Riva 1984; Wehnert 1989). In four of these there was a larger decrease during the drug treatment period than during the placebo period, and in three the response, was about the same. In (Massey 1986) there was a clear dose‐response effect. No crossover study used a pad test.

C. Quality of life (outcomes 01.06 to 01.08)

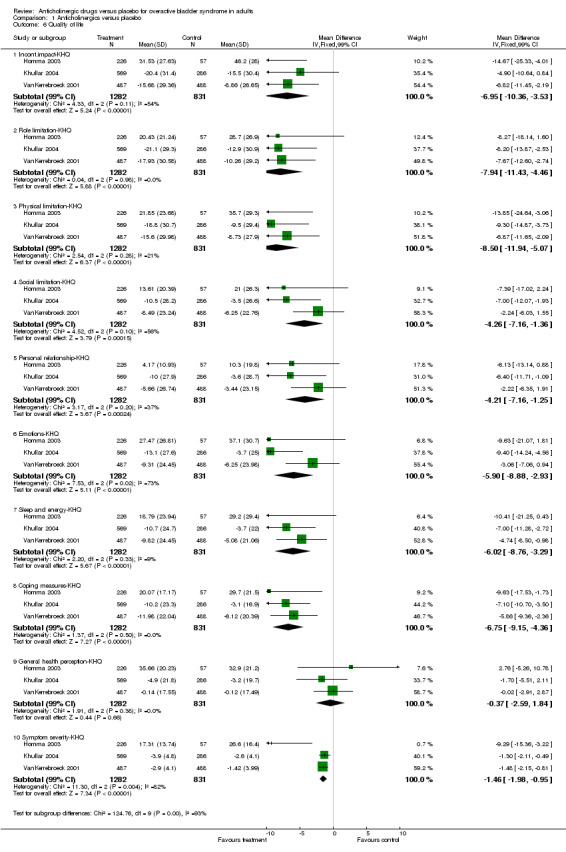

Seven trials reported on condition‐specific quality of life measures(Chapple 2004a; Dmochowski 2003; Dorschner 2000; Homma 2003; Khullar 2004; VanKerrebroeck 2001; Zinner 2002 ). Three trials (Homma 2003; Khullar 2004; VanKerrebroeck 2001) used the King's Health questionnaire; A lower score on the King's Health questionnaire indicates better quality of life. Homma (Homma 2003) reported on quality of life at the end of treatment and Khullar and Vankerrebroeck reported on change in quality of life. When data from all three trials were combined all separate domains apart from general health perception showed statistically significant difference favouring anticholinergic treatment (Outcome 01.06 for example WMD for incontinence impact score ‐6.95; 99% CI ‐10.36 to ‐3.53; P < 0.0000). Due to the fact that multiple domains in quality of life are reported we have chosen to report 99% confidence intervals. Two trials (Dmochowski 2003; Zinner 2004) used the IIQ questionnaire, when combined they showed a statistically significant difference for 'travel', favouring anticholinergics (WMD ‐7.27, 95% CI ‐11.07 to ‐3.48). Zinner found statistically significant differences for social life and emotional health, favouring anticholinergics. Dmochowski found a statistically significant difference for global health assessment of disease state, also favouring medication.

D. Socioeconomics

No trial reported any form of socioeconomic measure.

E. Adverse events (outcomes 01.09 and 01.10)

Twenty parallel‐group trials reported the number of people withdrawing due to adverse events (Abrams 1998; Abrams 2001; Alloussi 1998; Cardozo 2004; Chapple 2004a; Chapple 2004b; Dmochowski 2003; Drutz 1999; Haab 2004; Jacquetin 2001; Jonas 1997; Khullar 2004; Madersbacher 1999; Malone‐Lee 2001; Millard 1999; Rentzhog 1998; Stohrer 1999; Thuroff 1991; VanKerrebroeck 2001; Zinner 2002). There was no statistically significant difference in the number of withdrawals due to adverse events between medication and placebo groups (RR for withdrawal 1.11, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.36, outcome 01.10). The results of the meta analysis showed some statistically significant heterogeneity (P = 0.01).The data from a dose‐ranging study of tolterodine (0.5 mg, 1 mg, 2 mg, 4 mg all twice daily versus placebo, Rentzhog 1998) appeared to be different from the other trials, finding significantly more withdrawals in placebo than medication groups (RR 0.13, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.70) Excluding the data from Rentzhog et al did not change the finding of the meta‐analysis much. In contrast, the data from Dmochowski and Haab significantly favoured placebo.

Dry mouth was the most frequently reported side effect and data were available from 27 parallel‐group trials (Abrams 1996; Abrams 1998; Burgio 1998; Cardozo 2000; Cardozo 2004; Chapple 2004a; Chapple 2004b; Drutz 1999; Freeman 2003; Haab 2004; Homma 2003; Jacquetin 2001; Jonas 1997; Junemann 2000; Khullar 2004; Madersbacher 1999; Malone‐Lee 2001; Millard 1999; Rentzhog 1998; Stohrer 1999; Szonyi 1995; Thuroff 1991; Ulshofer 2001; VanKerrebroeck 1998; VanKerrebroeck 2001; Zinner 2002; Zinner 2004). The risk of dry mouth was three times greater in the medication group (1907/6165, 31%, with dry mouth in the medication group versus 350/3567, 9.8%, in the placebo group); the RR for dry mouth was 3.0, (95% CI 2.70 to 3.34, outcome Metaview 01.11). Statistically significant heterogeneity was observed in this comparison (P<0.00001). It was difficult to determine the possible causes of heterogeneity; the possible influence of the type of medication was explored.

Fourteen trials compared tolterodine with placebo (Abrams 1996; Abrams 1998; Drutz 1999; Freeman 2003; Jacquetin 2001; Jonas 1997; Junemann 2000; Khullar 2004; Malone‐Lee 2001; Millard 1999; Rentzhog 1998; VanKerrebroeck 2001; VanKerrebroeck 1998; Zinner 2002). The risk of dry mouth was three times higher in the tolterodine group (1184/3951, 29%, in tolterodine group versus 178/2091, 8.5%, in the placebo group); RR for dry mouth 3.37 (95% CI 2.90 to 3.90).

Seven trials made comparisons of oxybutynin and placebo (Abrams 1998; Burgio 1998; Drutz 1999; Homma 2003; Madersbacher 1999; Szonyi 1995; Thuroff 1991). The risk of dry mouth was more than twice as great in the oxybutynin group (RR for dry mouth 2.41, 95% CI 2.02 to 2.87). However, statistically significant heterogeneity was observed amongst the oxybutynin trials (P<0.00001). Two trials in the elderly had very high rates of dry mouth in the placebo arm (Burgio 1998; Szonyi 1995), perhaps as a consequence of polypharmacy. When these two trials were excluded from the pooled analysis the risk of dry mouth was three times greater in the oxybutynin groups (266/434, 61% in oxybutynin group versus 48/284, 17%, in placebo group); RR for dry mouth 3.23 (95% CI 2.48 to 4.20) and the test for heterogeneity was no longer significant (P = 0.43).

Three trials (Chapple 2004a; Chapple 2004b; Cardozo 2004) compared solifenancin and placebo (RR for dry mouth 3.62, 95%CI 2.29 to 5.74).

Four trials compared trospium and placebo (Cardozo 2000; Junemann 2000; Ulshofer 2001; Zinner 2004 ). The risk of dry mouth was twice as great in the trospium group (RR for dry mouth 2.66, 95% CI 1.98 to 3.55) but statistically significant heterogeneity was observed in this comparison (P = 0.0065). Both Cardozo et al (Cardozo 2000) and Junemann et al (Junemann 2000) found significantly higher rates of dry mouth in the trospium groups but Ulshofer et al (Ulshofer 2001) found similar rates (approximately 50%) in both medication and placebo groups. The drug dose in the two former trials was 20 mg trospium twice daily, while the latter used 15 mg three times a day; otherwise the trials were very similar with regard to method and study population. Ulshofer et al (2001) also stated that trial participants were asked specific questions about side effects, including dry mouth, and it is possible this yielded high positive rates of reporting.

Propiverine was compared with placebo in two trials (Madersbacher 1999; Stohrer 1999) and propantheline with placebo in a single trial (Thuroff 1991). All three trials found significantly higher rates of dry mouth in the medication groups.

Adverse events were poorly recorded in the crossover trials, many of which did not provide numbers and only one study (Kramer 1987) presented the results in such a way that they could be combined with others. Adverse events were reported for 17 trials and in most trials there were more adverse events while on anticholinergic drugs than while on placebo. A few had about the same number. In the crossover trials, dry mouth data were reported in 17 trials (Bagger 1985; Bono 1982; Kramer 1987; Massey 1986; Meyhoff 1983; Moisey 1980; Moore 1990; Murray 1984; Riva 1984; Rosario 1995a; SerranoBrambila 2000; Tapp 1990; Walter 1982; Wehnert 1989; Wehnert 1992; Zeegers 1987; Zorzitto 1989). In eight of these, anticholinergics resulted in more people suffering from dry mouth, in six the numbers were about the same, and in three it was not clear which treatment was worse. Apart from one trial (Kramer 1987) it was not clear whether those who suffered from dry mouth in the drug and placebo periods were the same or different people.

Some form of compliance measure (for example pill counting) was reported in six trials (Jacquetin 2001; Jonas 1997; Malone‐Lee 2001; Szonyi 1995; Ulshofer 2001; VanKerrebroeck 2001).

Sensitivity analysis (data not shown) Despite clinical heterogeneity of the included trials (for example populations and medication) sensitivity analyses did not suggest that the findings were significantly modified by age, sex or diagnosis (neurogenic or idiopathic detrusor overactivity). The same applied to the type of medication, except for dry mouth as discussed above.

Discussion

This review is the first of a series of Cochrane reviews of drug therapy for overactive bladder syndrome and it should be viewed in that context. Other reviews have considered or will consider: (1) whether different anticholinergic drugs have different effects (Hay‐Smith 2005); (2) whether anticholinergic drugs are better than other active (non‐drug) therapies (Alhasso 2006); and (3) whether anticholinergic drugs are better than other drug treatments (Dublin 2004).

Principal findings

In contrast to many other treatments for lower urinary tract dysfunction, there are a relatively large number of trials comparing anticholinergic drugs with placebo medication. Adults with overactive bladder were more likely to report cure or improvement when taking active anticholinergic treatment. However, it appears that treatment has a large placebo response with 41% of people in the placebo groups reporting cure or improvement in symptoms. The additional benefit of active treatment was about 15% more improved or cured (equivalent to a number needed to treat of seven). The difference between the groups in micturitions and leakage episodes after treatment is statistically significant. All the trials included in the formal analysis showed a reduction in micturitions and leakage episodes in both active treatment and placebo groups. The difference in improvement between anticholinergic and placebo medication groups was on average about four less leakage episodes and five less voids per week in favour of anticholinergics. While the difference between the groups in micturitions and leakage episodes after treatment is statistically significant (the confidence intervals are tight), the issue is their clinical significance.

Although the data are still limited, this update contains more information about quality of life (for example Chapple 2004b; Khullar 2004). Where data are available, they favour the medication group and are highly statistically significant. The key issue, then, is whether the differences are clinically important and useful to patients. Pleil and colleagues (Pleil 2005) related changes in the King's Health Questionnaire to patients perceptions of benefit: firstly if they perceived a benefit from treatment and if so, secondly, whether they perceived it as 'a little' or 'much' benefit. Generally speaking, our estimates lie somewhat below the change scores of patients who described their benefit as 'a little' but with overlapping confidence intervals. This suggests that the changes observed in leakage episodes and voiding frequency do have a broader impact to improve health, but on average the benefits are modest.

The drugs do, however, have adverse effects. While there was no significant difference in the number of people withdrawing from the active and placebo treatment arms due to adverse events the confidence interval is compatible with up to a third withdrawing due to medication (RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.36). Dry mouth was a side effect reported by many trial participants. This was not surprising as dry mouth is the most widely experienced side effect of anticholinergic therapy. The risk of dry mouth in the active treatment groups increased three fold, depending on the type of medication. Two trials in elderly populations, both comparing oxybutynin chloride with placebo, seemed to report high rates of dry mouth compared with trials in other populations. Elderly people are often taking a number of medications and the higher rates of dry mouth in both active treatment and placebo groups might be related to other concurrent therapy. Aside from this, there were no obvious differences in the outcomes for elderly patients.

Limitations

In general, the reported methods of the trials were of moderate to high quality. Overall the reporting of many trials was poor with many not even reporting the age, sex or concurrent medications of the participants. This may be important as age and polypharmacy are independent predictors of dry mouth, the main adverse side effect of anticholinergics. However, the methods of group allocation were rarely given in sufficient detail to be sure that group allocation was adequately concealed. Only one trial blinded outcome assessors. The reporting of group allocation of dropouts and/or reasons for withdrawal was adequate in less than half the trials. Crossover trials were usually poorly reported. In order to be included in a meta‐analysis the results from crossover trials for continuous variables must be reported as a difference in means together with either the standard deviation, standard error or 95% confidence interval of that difference. This does coincide with what is of clinical interest, but can become complex when there are more than two treatments. Dichotomous outcomes should be reported so that it is clear whether the events on each treatment occurred in the same or different people. Only two of the nineteen crossover trials reported outcomes in this manner, but they were not consistent in the outcomes that were reported.

In view of the substantial number of trials it is disappointing that it was not possible to combine more data. There was considerable variation in outcomes chosen to be reported, and also variation in how the same outcome was measured and reported. Relatively few trials sought the patient's opinion on satisfaction with, and acceptability of, treatment and these are important factors in the choice of management. Only seven relatively recent trials addressed quality of life, and none reported socioeconomic outcomes. These areas need to be addressed in future research. In view of the lack of validated 'normal' values and the lack of correlation between urodynamic findings and clinical outcome, the emphasis on urodynamic measures should be re‐evaluated, and we have chosen to remove these data from this update.

None of the included trials reported results for those with frequency and/or urgency alone separately from those with urge incontinence. A number of trials included men and women, but did not report outcome separately by sex so it was difficult to investigate possible differences in effects between the sexes.

We decided to combine the data from all the active anticholinergic treatment arms in trials where there was more than one drug or more than one dose of the same drug being compared. It is possible that some medications are more effective than others but that this was not seen in the formal comparisons. However, direct comparisons of different anticholinergic therapies, and comparisons of different doses of the same therapy, will be investigated in a separate review (Hay‐Smith 2005). One of the limitations of the review is that many trials do not contribute to the meta‐analyses. Those that do may or may not be a biased selection of the population of primary trials. In addition, despite comprehensive searching not all trials may have been located. Data were combined from primary trials recruiting on different criteria or using different drugs in various doses. These factors may influence the estimates of effect in this review. Examination of the graphs shows, however, that the effects are generally consistent across the included trials that did contribute. It proved difficult to explore the reasons on the few occasions where heterogeneity was observed. The best way to address these concerns would be to perform an individual patient data meta‐analysis. Many more trials would then contribute to the analysis. In addition the effect of confounders (such as age, cause of overactive bladder) could be investigated.

In general, many of the included trials had the characteristics of explanatory rather than pragmatic trials. Explanatory trials, also known as efficacy trials, address the question 'can this therapy work?'. Efficacy studies tend to have strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, a comparison of therapy versus placebo, short‐term outcomes, measure surrogate rather than patient centred outcomes (for example urodynamics rather than quality of life) and take place in centres of clinical excellence. Their results are commonly used to support applications for drug regulatory approval. In contrast, pragmatic trials, also known as effectiveness trials, address the question 'does this therapy work?'. Effectiveness studies are characterised by large, more heterogeneous samples, comparisons with standard care, less restrictive inclusion/exclusion criteria, and long‐term patient‐centred outcomes (Roland 1998). Their results inform the choice of management in everyday clinical settings.

All the included trials were of short duration and measured outcome at the end of treatment. Therefore outcome was measured when the effects of treatment were likely to be at their maximum. Anticholinergics are unlikely to cure overactive bladder syndrome, so the long term effects of treatment are of most clinical interest. Some trials have continued with open‐label follow up. The interpretation of these is difficult, not only because of the use of active treatment by those originally allocated placebo but also because of the number of overlapping pooled analyses published, based on different numbers of primary studies. In a follow up of a single study, it was found that 71% of patients completed 12 months of open label follow up on extended release tolterodine (van Kerrebroeck 2001). In contrast, Lawrence et al (2000) audited a pharmaceutical database in the USA and reported that less than a third of people continued to fill out prescriptions for either immediate release tolterodine or immediate release oxybutynin six months after the first prescription, although the use of oxybutynin was discontinued faster than tolterodine (Lawrence 2000). This may represent the differences between people prescribed anticholinergics in a trial versus a more typical care setting.

Pharmaceutical companies are continuing to develop anticholinergic drugs. Some drugs are no longer in widespread clinical use (for example emepronium ) and others have been withdrawn from the market (for example terodiline). Alternative delivery systems (such as transdermal, slow‐release preparations) and new drugs (for example darifenacin) are becoming available, which may be more effective or have fewer side effects, or both due to adverse effects.

It is worth noting that 21 of the 61 trials declared pharmaceutical company support (Abrams 1998; Bagger 1985; Cardozo 2000; Chapple 2004b; Coombes 1996;Davila 2001; Dorschner 2000; Drutz 1999; Homma 2003; Jacquetin 2001; Meyhoff 1983; Moisey 1980; Moore 1990; Rentzhog 1998; Szonyi 1995; Tapp 1990; Thuroff 1991; Ulshofer 2001; VanKerrebroeck 1998; VanKerrebroeck 2001; Walter 1982). This support ranged from the supply of active and placebo tablets (in blinded packaging) through to full funding and data analysis. None of the remaining trials made any statement about the absence or presence of company involvement. Two trials were funded by grants from health research bodies (Burgio 1998; Zorzitto 1989). In other settings, meta‐analyses comparing findings from drug company funded studies with non‐drug company funded trials have found that the outcomes of company funded studies are more favourable to the new treatment, although this is not always the case. In general, in this review, the trials supported by companies were well reported and appeared to be of better methodological quality. Their limitations are that, for understandable reasons, they addressed issues of efficacy and safety rather than clinical and cost effectiveness.

This review provides clear evidence of efficacy and of the likelihood of adverse effects, particularly dry mouth. Newer trials suggest that the positive effects are translated into improved quality of life while medication continues, at least on average. However, there is very little evidence about the long‐term effects of medication. This applies to fixed length courses of treatment and to continued treatment for an indefinite period of time, both during treatment and after it has stopped. Addressing these issues requires a shift in the research agenda to more pragmatic trial designs.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The administration of anticholinergic drugs for overactive bladder syndrome results in statistically significant differences compared to placebo medication. Those receiving anticholinergic therapy were more likely to report cure or improvement of symptoms, and a reduction in leakage episodes (about four per week) and voids (about five per week). Evidence from more recently reported trials indicates modestly improved quality of life too. There was a marked placebo response, however. When counseling those with overactive bladder syndrome, these benefits need to be balanced with the risk of side effects, notably dry mouth. Depending on the type of medication being offered, the risk of dry mouth is increased by three times.

The only long‐term follow up comes from open‐label studies, with anticholinergic therapy offered to all trial participants regardless of their original allocation to active or placebo treatment. The short duration of most trials and the lack of long‐term follow up gives little information about the long‐term effects and acceptability of anticholinergic therapy.

Cost‐effectiveness was also not addressed.

Implications for research.

To allow the results of trials to be considered together most usefully, future research in overactive bladder syndrome should incorporate standardised, validated outcome and quality of life measures that are relevant to those with an overactive bladder. Particular attention needs to be paid to the patient perception of change and satisfaction with outcome, quality of life, and economic outcomes. The current emphasis on urodynamic measures needs to be redressed. Reporting of the methods of group allocation and the description of dropouts needs to be improved; outcome assessors should be masked to group allocation. The reporting of crossover trials needs to be dramatically improved if they are to add anything to the body of knowledge about these drugs.

As anticholinergic drugs are unlikely to be curative, sustained success is likely to depend on people continuing to take them. Trials are needed to assess the long‐term usefulness of these drugs.

Both oxybutynin and tolterodine have been compared with placebo in a number of trials. For these drugs it seems that priority should be given to research in subgroups that might benefit most, or who have previously been excluded from trials. In addition, all drugs need to be tested in large pragmatic trials. Nearly all the included trials used oral administration of medication. Further research would also be useful to investigate whether the magnitude of effect changes with different delivery systems (for example skin patches or slow‐release preparations) would also be useful. Another Cochrane review comparing anticholinergics with each other will address these questions (Hay‐Smith 2005). Intravesical administration has potential as it delivers the drug directly to the desired site of action, thus eliminating some troublesome anticholinergic side effects but would only be clinically useful if intravesical administration could be made easier. In our view, placebo‐controlled trials should be confined to testing the short‐term efficacy and safety of new anticholinergic therapies.

The reliability and hence value of this review would be greatly enhanced if data from more trials could be incorporated in an individual patient data meta‐analysis.

Feedback

Study characteristics (pages 27?28) for reference

Summary

Dear Authors > > With regards to the above reference, we believe that the study > characteristics quoted on pages 27?28 do not appear to correlate to > those in the published paper. Whereas the study cited in the review > investigated only solifenacin, with tolterodine as a comparator, the > characteristics quoted include details about another anticholinergic > compound, darifenacin, implying that this compound was included for > comparison in the study. > It > seems possible that a second paper by Chapple et al, reporting on the > efficacy of darifenacin, has been included in the description of the > study characteristics by mistake (this second paper, entitled ?A > pooled analysis of three phase III studies to investigate the > efficacy, tolerability and safety of darifenacin, a muscarinic M3 > selective receptor antagonist, in the treatment of overactive bladder? > (BJU 2005;95(7):993‐1001), discusses two doses of darifenacin (7.5 mg, > n=337 and 15 mg, n=334) versus placebo (n=388)). > > We would therefore like to request a review of the text on pages 27 ? > 28, > and a potential amendment to the study characteristics as necessary. > In addition, as quality of life (QoL) data is not discussed in either > of the above papers by Chapple et al, statements such as ?QoL data > reported favours solifenacin? in the table of study characteristics > are potentially misleading to the reader. > We look forward to your review of the text and modification of the > study characteristics table.

Reply

the info in characteristics of studies table has now been changed

Contributors

Nabi Ghulam, Peter Herbison, June Cody

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 16 September 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 1999 Review first published: Issue 3, 2002

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 22 August 2006 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment. 14 trials added |

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the following: Birgit Moehrer (BM) for help with assessment of trials published in German, Italian and Flemish. Fernanda Teixeira (FT) for help with trials published in Spanish. Dr Life Rentzhog and Professor Wolfgang Dorschner for providing unpublished data. Atsuo Kondo (AK) for translation of a study reported in Japanese. Sylvia Anton (SA) for translation of a study reported in German. U Azman, P Collin, S Radley, D Richmond, C Chapple who were the authors of a previous protocol for this review.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Anticholinergics versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Patient perception of cure or improvement | 8 | 2742 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.39 [1.28, 1.51] |

| 2 Leakage episodes in 24 hours | 12 | 4582 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.51 [‐0.66, ‐0.37] |

| 2.1 number of leakage episodes | 4 | 1987 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.38 [‐0.63, ‐0.13] |

| 2.2 change in leakage episodes | 8 | 2595 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.58 [‐0.76, ‐0.40] |

| 3 Leakage episodes in 24 hours | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 4 Micturitions in 24 hours | 12 | 5977 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.68 [‐0.84, ‐0.52] |

| 4.1 number of micturitions | 2 | 1394 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.96 [‐1.43, ‐0.49] |

| 4.2 change in micturitions | 10 | 4583 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.64 [‐0.81, ‐0.47] |

| 5 Micturition in 24 hours | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 6 Quality of life | 3 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 99% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6.1 Incont.impact‐KHQ | 3 | 2113 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 99% CI) | ‐6.95 [‐10.36, ‐3.53] |

| 6.2 Role limitation‐KHQ | 3 | 2113 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 99% CI) | ‐7.94 [‐11.43, ‐4.46] |

| 6.3 Physical limitation‐KHQ | 3 | 2113 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 99% CI) | ‐8.50 [‐11.94, ‐5.07] |

| 6.4 Social limitation‐KHQ | 3 | 2113 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 99% CI) | ‐4.26 [‐7.16, ‐1.36] |

| 6.5 Personal relationship‐KHQ | 3 | 2113 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 99% CI) | ‐4.21 [‐7.16, ‐1.25] |

| 6.6 Emotions‐KHQ | 3 | 2113 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 99% CI) | ‐5.90 [‐8.88, ‐2.93] |

| 6.7 Sleep and energy‐KHQ | 3 | 2113 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 99% CI) | ‐6.02 [‐8.76, ‐3.29] |

| 6.8 Coping measures‐KHQ | 3 | 2113 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 99% CI) | ‐6.75 [‐9.15, ‐4.36] |

| 6.9 General health perception‐KHQ | 3 | 2113 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 99% CI) | ‐0.37 [‐2.59, 1.84] |

| 6.10 Symptom severity‐KHQ | 3 | 2113 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 99% CI) | ‐1.46 [‐1.98, ‐0.95] |

| 7 Quality of life at the end | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 99% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 7.11 Contilife score | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 99% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 8 Change in quality of life‐IIQ‐7 | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 8.1 Embarrassment | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8.2 Mental Health | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8.3 Travel | 2 | 835 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐7.27 [‐11.07, ‐3.48] |

| 8.4 Restroom | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8.5 Shopping | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8.6 Social life | 1 | 474 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐4.50 [‐8.38, ‐0.62] |

| 8.7 Physical activity | 1 | 475 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.5 [‐7.21, 2.21] |

| 8.8 Emotional health | 1 | 473 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐4.9 [‐9.06, ‐0.74] |

| 8.9 Global Assessment of disease state | 1 | 361 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐10.51 [‐17.20, ‐3.82] |

| 9 Withdrawal due to adverse events | 20 | 7576 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.11 [0.91, 1.36] |

| 10 Dry mouth | 27 | 9732 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.00 [2.70, 3.34] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticholinergics versus placebo, Outcome 1 Patient perception of cure or improvement.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticholinergics versus placebo, Outcome 2 Leakage episodes in 24 hours.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticholinergics versus placebo, Outcome 3 Leakage episodes in 24 hours.

| Leakage episodes in 24 hours | |

|---|---|

| Study | |

| Zinner 2004 | Treatment group: decrease of 59% from baseline at 12 weeks Placebo Group: decrease of 44% from baseline at 12 weeks |

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticholinergics versus placebo, Outcome 4 Micturitions in 24 hours.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticholinergics versus placebo, Outcome 5 Micturition in 24 hours.

| Micturition in 24 hours | |

|---|---|

| Study | |

| Landis 2004 | Treatment group: median of 9.85 voids (range 2.28 to 51.28) Placebo group: median of 10.57 voids (range 2 to 37.42) |

| Zinner 2004 | Treatment group: decrease of 2.37 voids from baseline at 12 weeks Placebo group: decrease of 1.29 voids from baseline at 12 weeks |

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticholinergics versus placebo, Outcome 6 Quality of life.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticholinergics versus placebo, Outcome 7 Quality of life at the end.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticholinergics versus placebo, Outcome 8 Change in quality of life‐IIQ‐7.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticholinergics versus placebo, Outcome 9 Withdrawal due to adverse events.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticholinergics versus placebo, Outcome 10 Dry mouth.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Abrams 1996.

| Methods | RCT. Placebo controlled, parallel design. Phase II. Double‐blind. Masking of assessors not stated. PP analysis. Multicentre. | |

| Participants | 82 patients. Inclusion criteria: Objective signs of neurological disease and urinary frequency or incontinence and urodynamically proven detrusor hyperreflexia. Exclusion criteria: Treatment within preceding 14 days with other anticholinergic drugs. | |

| Interventions | Group 1: placebo (n=15) Group 2: tolterodine 0.5mg bid (n=12) Group 3: tolterodine 1mg bid (n=14) Group 4: tolterodine 2mg bid (n=16) Group 5: tolterodine 4mg bid (n=10) 14 day treatment period. 2 week runin. | |

| Outcomes | Number of leakage episodes, frequency of micturition, volume voided. Urodynamic parameters. Adverse events. Laboratory tests. ECG. Blood pressure. | |

| Notes | Abstract. Dose reduction permitted within first week. Dropouts not stated. Incomplete subjective data. No follow up. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Abrams 1998.

| Methods | RCT. Placebo controlled, parallel design. Phase III. Randomised 2:2:1 Double‐blind. Masking of assessors not stated. ITT analysis. Multicentre (42) Multinational (3). | |

| Participants | 293 male and female patients. Inclusion criteria: At least 18 years old with urodynamically confirmed OB, increased frequency of micturition (at least 8/24 hours) UI (at least 1/24 hours) and/or urgency Exclusion criteria: Clinically significant SI, detrusor hyperreflexia, hepatic, renal or haemotological disorders, symptomatic or recurrent UTI, BOO, bladder training or electrostimulation therapy, indwelling catheter or self catheterisation, pregnant or breastfeeding or women not using reliable contraception. | |

| Interventions | Group 1: placebo (n=57) Group 2: tolterodine 2mg bid (n=118) Group 3: oxybutynin 5mg tid (n=118) 12 week treatment period. 1 week runin. | |

| Outcomes | Symptom questionnaire ( 6 point rating severity scale) Number of leakage episodes, frequency of micturition, volume voided. Adverse events. Laboratory tests. Blood pressure. | |

| Notes | Dose reduction to prevent withdrawal. Two week follow up. 37 dropouts (Group 1: 7, Group 2: 10, Group 3: 20) Company support declared. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Abrams 2001.

| Methods | RCT. Placebo controlled, parallel design. Randomised 2:1. Double‐blind. Masking of assessors not stated. Multicentre. Multinational. | |

| Participants | 221 male patients. Inclusion criteria: Men over 40 years with urodynamically verified overactive bladder and mild, moderate or severe BOO. Exclusion criteria: Concurrent treatment with 5alpha‐reductase inhibitors or alpha‐adrenergic antagonists, baseline postvoid residual >40% maximum cystometric capacity, prior prostate or bladder surgery. | |

| Interventions | Group 1: tolterodine 2mg bid (n=149) Group 2: placebo (n=72) 12 week treatment period. | |

| Outcomes | Urodynamic parameters. Adverse events. | |

| Notes | Abstract. 28 dropouts (Group 1: 16, Group 2: 12). No follow up. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Alloussi 1998.

| Methods | RCT. Placebo controlled, parallel design. Randomised 2:1. Double‐blind. Masking of assessors not stated. PP analysis. Multicentre (46) Multinational (3). | |

| Participants | 309 male and female patients. Inclusion criteria: At least 18 years old with written, informed consent, confirmed DO by medical history and urodynamics, for mixed incontinence, motor component to be dominant and accompanied by at least one unstable contraction at minimum 10cm H2O with simultaneous urge or urge incontinence. Maximum cystometric capacity <350ml. Exclusion criteria: Pregnant or breastfeeding women, urological or gynaecological surgeries <3 months previous, neurogenic detrusor hyperactivity, exclusive stress incontinence, closed‐angle glaucoma, untreated tachycardiac dysrhythmia, gastrointestinal stenoses, myasthenia gravis, UTI, allergies and/or intolerance towards atropine, oxybutynin, trospium chloride, or tablet adjuvants. Patients treated with anticholinergics, tri‐ or tetracyclic antidepressants, calcium antagonists started >3 months before study, or beta‐sympathomimetics within 7 days before first urodynamic measurement, antihistamines, amantadine, quinidine and disopyramide disallowed. | |

| Interventions | Group 1: trospium chloride 20mg bid (n=210) Group 2: placebo (n=99) 3 week treatment period. 7 day run‐in. | |

| Outcomes | Assessment of patient improvement. Micturition diaries for 2 days during study. Urodynamic parameters. Adverse events. Laboratory tests. | |

| Notes | 47 dropouts ( Group 1: 32, Group 2: 15). No follow up. Micturition diaries done inconsistently and only a few available at end of study. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Bagger 1985.

| Methods | RCT. Placebo controlled, cross‐over design. Double‐blind. Masking of assessors not stated. ITT analysis. | |

| Participants | 18 female patients. Inclusion criteria: Urge incontinence as defined by the International Continence Society. Exclusion criteria: Recent cystitis, pregnancy, vaginal vault prolapse and stress incontinence. Major neurological disorders. Intake of drugs with presumed effect on bladder function. | |

| Interventions | Treatment 1: placebo Treatment 2: emepronium carrageenate 500mg per day Treatment 3: emepronium carrageenate 1000mg per day. 2 week period for each treatment. Washout?? | |

| Outcomes | Number of leakage episodes, frequency of micturition, volume voided. Adverse events. Laboratory tests. | |

| Notes | 1 dropout (Treatment 2). No follow up. Data not in useable form for this review. Company support declared. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Bono 1982.

| Methods | RCT. Placebo controlled, cross‐over design. Assessors masked. ITT analysis. | |

| Participants | 16 male and female patients Inclusion criteria: Non‐pregnant with cystometric diagnosis or symptoms of bladder pain, hesitancy, dysuria, urgency, urge incontinence, stress incontinence, frequency, nocturia. Exclusion criteria: UTI or other urinary pathology. | |

| Interventions | Treatment 1: oxybutynin 5mg tid Treatment 2: placebo 2 x 10 day treatments. | |

| Outcomes | Urodynamic parameters. Adverse events. | |

| Notes | Translated from Italian. 1 dropout No follow up. Data not in useable form for this review. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Burgio 1998.