Visual Abstract

Keywords: kidney transplantation, mortality, COVID-19, United States

Abstract

Background and objectives

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has had a profound effect on transplantation activity in the United States and globally. Several single-center reports suggest higher morbidity and mortality among candidates waitlisted for a kidney transplant and recipients of a kidney transplant. We aim to describe 2020 mortality patterns during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States among kidney transplant candidates and recipients.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

Using national registry data for waitlisted candidates and kidney transplant recipients collected through April 23, 2021, we report demographic and clinical factors associated with COVID-19–related mortality in 2020, other deaths in 2020, and deaths in 2019 among waitlisted candidates and transplant recipients. We quantify excess all-cause deaths among candidate and recipient populations in 2020 and deaths directly attributed to COVID-19 in relation to prepandemic mortality patterns in 2019 and 2018.

Results

Among deaths of patients who were waitlisted in 2020, 11% were attributed to COVID-19, and these candidates were more likely to be male, obese, and belong to a racial/ethnic minority group. Nearly one in six deaths (16%) among active transplant recipients in the United States in 2020 was attributed to COVID-19. Recipients who died of COVID-19 were younger, more likely to be obese, had lower educational attainment, and were more likely to belong to racial/ethnic minority groups than those who died of other causes in 2020 or 2019. We found higher overall mortality in 2020 among waitlisted candidates (24%) than among kidney transplant recipients (20%) compared with 2019.

Conclusions

Our analysis demonstrates higher rates of mortality associated with COVID-19 among waitlisted candidates and kidney transplant recipients in the United States in 2020.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has had a dramatic effect on organ transplantation in the United States and globally, with a particularly large effect on kidney transplantation (1–4). A substantial reduction in transplant activity in the United States resulted from the need to conserve health care resources where possible and a desire to avoid COVID-19–related morbidity and mortality in immunosuppressed recipients perceived to be at higher risk of severe disease (3,5,6).

Assessment of the risk and the effect that COVID-19 has had on candidates waitlisted for a kidney transplant and transplant recipients has largely been restricted to single-center studies or registry studies that leveraged voluntary reporting from a relatively small set of transplant centers (7–13). These individual case series have included patients with varying severity of disease and have reported a wide range of mortality, making it difficult to accurately assess the excess risk experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic by these patient cohorts or the factors associated with COVID-19 mortality (14). Even fewer studies have reported the burden of COVID-19 infections on their patients who are waitlisted and transplanted (14–17). Understanding the differential effect of the pandemic on each of these populations is critical to guide policies about how to best care for patients with kidney failure and inform institutional resource allocation planning during the pandemic and subsequently.

We describe COVID-19 mortality across the United States in 2020 and associated factors among patients waitlisted for a kidney transplant and active transplant recipients with a functioning kidney transplant, on the basis of national data as of April 23, 2021.

Materials and Methods

This study used national data from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) Standard Transplant Analysis and Research files on the basis of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation (OPTN) database as of March 5, 2021, and a supplemental data file from UNOS providing additional data through April 23, 2021 (received May 6, 2021). The primary study population included two groups: (1) all kidney-only transplant candidates alive and prevalent on the waitlist as of January 1, 2020 or incident candidates added to the waitlist in 2020, regardless of active or inactive status, and (2) active transplant recipients as of January 1, 2020 or incident transplant recipients with a transplant date in 2020. Active transplant recipients were defined as recipients with no graft failure date before January 1, 2020 and a last patient follow-up date of January 1, 2019 or later. Descriptive characteristics were calculated for each of these two groups as of their cohort entry time (January 1 or later waitlisting/transplant date in 2020) and are presented in Table 1. From this population, we identified two cohorts of all deaths occurring in 2020 among (1) candidates still on the waiting list, and (2) active transplant recipients (patients with graft failure before death were not included). Deaths occurring in 2020 were identified using all death dates available in the Standard Transplant Analysis and Research files as of April 23, 2021, which includes deaths reported directly by transplant centers and supplemented from the Social Security Death Master File. The primary outcome of interest was death in 2020 attributed to COVID-19, defined as the presence of a primary or contributory cause of death code corresponding to “INFECTION: VIRAL–COVID-19” as reported by the transplant centers in the OPTN database. Non–COVID-19 deaths in 2020 were defined as the absence of any COVID-19 cause of death code and included deaths with missing/unknown cause codes. We also identified all deaths among corresponding cohorts of kidney-only transplant candidates or active transplant recipients in 2019 and 2018 for historical comparison.

Table 1.

Characteristics of kidney-only candidates on the waiting list or active transplant recipients as of January 1, 2020 plus incident waitlist additions or transplants later in 2020

| Characteristics, Median (Interquartile Range) or n (%) | Waitlisted Candidates (n=134,948) | Transplant Recipients (n=190,481) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 56 (45–64) | 57 (45–66) |

| Sex, M | 83,797 (62) | 113,310 (59) |

| Race/ethnicity a | ||

| White | 49,645 (37) | 94,123 (49) |

| Black | 42,401 (31) | 47,374 (25) |

| Hispanic | 27,650 (20) | 32,229 (17) |

| Asian | 11,855 (9) | 13,080 (7) |

| Other/multiracial | 3397 (3) | 3674 (2) |

| Education level | ||

| High school/GED or lower | 58,744 (44) | 82,492 (43) |

| Attended college/technical school | 33,799 (25) | 44,529 (23) |

| Associate or bachelor degree | 26,685 (20) | 35,227 (18) |

| Graduate degree | 11,028 (8) | 14,908 (8) |

| N/A or unknown | 4692 (3) | 13,325 (7) |

| Primary payer at listing or transplant | ||

| Private | 58,204 (43) | 69,536 (37) |

| Public | 76,353 (57) | 119,035 (62) |

| Other/unknown | 391 (0.3) | 1910 (1) |

| History of diabetesa | 59,958 (44) | 53,704 (29) |

| BMI at transplant or latest WL valuea | 28.9 (25.0–33.0) | 27.1 (23.4–31.3) |

| Obese (BMI ≥30)a | 57,358 (43) | 60,482 (32) |

| Blood group | ||

| O | 70,774 (52) | 86,144 (45) |

| A | 38,514 (29) | 69,552 (37) |

| B | 21,855 (16) | 25,574 (13) |

| AB | 3805 (3) | 9211 (5) |

| OPTN region | ||

| 1 | 6035 (4) | 8436 (4) |

| 2 | 17,112 (13) | 24,031 (13) |

| 3 | 18,332 (14) | 24,568 (13) |

| 4 | 14,580 (11) | 15,864 (8) |

| 5 | 28,367 (21) | 30,391 (16) |

| 6 | 3524 (3) | 7215 (4) |

| 7 | 9922 (7) | 18,388 (10) |

| 8 | 5742 (4) | 12,751 (7) |

| 9 | 10,070 (7) | 13,737 (7) |

| 10 | 7997 (6) | 16,547 (9) |

| 11 | 13,267 (10) | 18,553 (10) |

| Time since listing or transplant, yr | 1.0 (0.0–2.8) | 4.1 (1.2–8.7) |

| <1 | 67,533 (50) | 43,525 (23) |

| 1–5 | 53,504 (40) | 63,443 (33) |

| >5 | 13,911 (10) | 83,513 (44) |

| PRA ≥98%a | 9302 (7) | 9908 (5) |

| KDPI, if deceased donor transplanta | – | 39 (18–61) |

| HLA mismatcha | – | 4 (3–5) |

| Donor typea | ||

| Deceased | – | 125,692 (66) |

| Living | – | 64,784 (34) |

| Preemptive | 36,707 (27) | 33,105 (18) |

| Dialysis time (yr) if nonpreemptivea | 3.0 (1.5–5.1) | 3.1 (1.4–5.4) |

The other/multiracial category includes: (waitlist) 1157 American Indian/Alaska native, 785 Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander, and 1455 multiracial; (transplant) 1373 American Indian/Alaska native, 745 Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander, and 1556 multiracial. GED, general educational development; M, male; WL, waitlist; BMI, body mass index; OPTN, Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network; PRA, panel reactive antibodies; KDPI, Kidney Donor Profile Index.

Missing values excluded. Waitlist: 62 missing diabetes, 297 BMI; transplant: one missing race, 2586 diabetes, 697 BMI, 1607 PRA, 1411 KDPI, 830 HLA mismatch, five foreign donors excluded, 937 missing dialysis time.

Characteristics were compared between deaths in 2020 attributed to COVID-19, deaths in 2020 from all other causes (including unknown/no cause code reported), and deaths in 2019 among waitlisted candidates or active transplant recipients using descriptive statistics (median and interquartile range or count and column percentages) with chi-squared or Kruskal–Wallis tests. Further pairwise comparisons between the three groups were performed using Dunn’s test or chi-squared tests with a Bonferroni multiple comparisons adjustment. Characteristics of interest included candidate or recipient age at the time of death, sex, race/ethnicity as reported by transplant centers and combined into the single ethcat variable in the UNOS database (categorized in our study as non–Hispanic White, non–Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Asian, and other/multiracial), highest educational attainment at candidate registration, primary insurance payer at listing or transplant (private, public, or other/unknown), history of diabetes, body mass index at transplant or latest reported waitlist value, obesity (body mass index ≥30 kg/m2), ABO blood group, OPTN region, years between listing or transplant and death, panel reactive antibodies (PRA) sensitization ≥98% calculated from the maximum of all PRA/cPRA variables recorded in the KIDPAN data file, Kidney Donor Profile Index (KDPI) for deceased donor transplants, HLA mismatch and donor type for transplants, preemptive status at death or transplant (defined as dialysis start dates missing and pretransplant dialysis variables not recorded as yes), and dialysis time at death or transplant for nonpreemptive patients. Missing data for primary payer and education level were included as categories, otherwise patients with missing data for other variables were excluded from the statistical comparisons in the descriptive tables, as noted in the table footnotes.

Counts of all deaths recorded in the UNOS database among candidates or recipients were calculated by the week beginning January 1 for the years 2020, 2019, and 2018 to visualize all-cause and COVID-19–attributed mortality trends across recent years. The count of reported deaths in 2019 or 2018 were subtracted from the count of reported deaths (all-cause) in 2020 to estimate the magnitude of excess mortality in these patient groups. Relative change from recent years was calculated as the difference in number of deaths divided by the number of deaths in 2019 or 2018, respectively, times 100. Mortality rates in 2020 and 2019 were calculated per 100 person-years for both the waitlisted candidate cohort and the active transplant recipient cohort.

Analyses were conducted using Stata MP 15.1 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX) with the additional Dunn test package. An alpha of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance.

Results

Patients Who Are Waitlisted

There were 4774 deaths reported in 2020 in the United States among waitlisted kidney-only transplant candidates, including 516 (11%) deaths that were attributed to COVID-19. Candidates who died of COVID-19 were of similar age to those who died of other causes in 2020, but significantly more likely to be male (72% versus 65%), obese (53% versus 45%), and belong to a racial/ethnic minority group (85% versus 60%) (Table 2). History of diabetes was slightly more frequent among COVID-19–related deaths (69% versus 66% among non–COVID-19 deaths in 2020), but blood group was not associated with COVID-19 attributed mortality. Only a small minority of candidates who died of COVID-19 were White (15%), whereas 72% of all COVID-19–related waitlist deaths occurred in Black or Hispanic candidates. This was significantly different from both non–COVID-19 deaths in 2020 (40% White and 50% Black or Hispanic) and deaths in 2019 (39% White and 50% Black or Hispanic, Figure 1). Educational attainment was significantly different for candidates who died of COVID-19 in 2020 compared with both non–COVID-19 deaths in 2020 and deaths in 2019. Patients with high school/general educational development education or less were over-represented among the COVID-19–attributed deaths in 2020 (60%) compared with non–COVID-19 deaths in 2020 (46%) and deaths in 2019 (46%).

Table 2.

Characteristics of kidney transplant candidates who died on the waiting list in 2019, in 2020 with a cause of death code attributed to coronavirus disease 2019, or in 2020 without a coronavirus disease 2019 cause of death code, from United Network for Organ Sharing registry data as of April 23, 2021

| Characteristics, Median (Interquartile Range) or n (%) | Deaths on the Waitlist | 2019 | Global | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Deaths, 2019–2020 | Coronavirus Disease, 2019–2020 | Non–Coronavirus Disease, 2019–2020 | |||

| (n=8630) | (n=516) | (n=4258) |

(n=3856) |

P Value | |

| Age at time of death | 61 (53–67) | 60 (53–66) | 61 (53–67) | 61 (53–67) | 0.57 |

| Sex, M | 5579 (65) | 371 (72) | 2779 (65)a | 2429 (63)a | <0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.001 | ||||

| White | 3294 (38) | 79 (15) | 1703 (40)a | 1512 (39)a | |

| Black | 2713 (31) | 178 (34) | 1317 (31) | 1218 (32) | |

| Hispanic | 1722 (20) | 193 (37) | 811 (19) | 718 (19) | |

| Asian | 675 (8) | 53 (10) | 317 (7) | 305 (8) | |

| Other/multiracial | 226 (3) | 13 (3) | 110 (3) | 103 (3) | |

| Education level | <0.001 | ||||

| High school/GED or less | 4039 (47) | 309 (60) | 1944 (46)a | 1786 (46)a | |

| Attended college/technical school | 2149 (25) | 103 (20) | 1076 (25) | 970 (25) | |

| Associate or bachelor degree | 1526 (18) | 68 (13) | 780 (18) | 678 (18) | |

| Graduate degree | 625 (7) | 21 (4) | 317 (7) | 287 (7) | |

| N/A or unknown | 291 (3) | 15 (3) | 141 (3) | 135 (4) | |

| Primary payer at listing | 0.15 | ||||

| Private | 3181 (37) | 166 (32) | 1568 (37) | 1446 (38) | |

| Public | 5429 (63) | 350 (68) | 2679 (63) | 2400 (62) | |

| Other/unknown | 20 (0) | 0 (0) | 11 (0) | 9 (0) | |

| History of diabetesb | 5592 (65) | 356 (69) | 2787 (66) | 2449 (64) | 0.02 |

| BMI at latest WL measureb | 29.3 (25.5–33.4) | 30.4 (26.9–34.0) | 29.3 (25.4–33.5)a | 29.2 (25.3–33.2)a | <0.001 |

| Obese (BMI ≥30)b | 3887 (45) | 272 (53) | 1928 (45)a | 1687 (44)a | 0.001 |

| Blood group | 0.30 | ||||

| O | 4707 (55) | 276 (53) | 2328 (55) | 2103 (55) | |

| A | 2332 (27) | 138 (27) | 1187 (28) | 1007 (26) | |

| B | 1370 (16) | 87 (17) | 637 (15) | 646 (17) | |

| AB | 221 (3) | 15 (3) | 106 (2) | 100 (3) | |

| OPTN region | <0.001 | ||||

| 1 | 432 (5) | 25 (5) | 221 (5)a | 186 (5)a | |

| 2 | 1138 (13) | 63 (12) | 568 (13) | 507 (13) | |

| 3 | 1234 (14) | 52 (10) | 621 (15) | 561 (15) | |

| 4 | 877 (10) | 56 (11) | 443 (10) | 378 (10) | |

| 5 | 2102 (24) | 124 (24) | 988 (23) | 990 (26) | |

| 6 | 105 (1) | 3 (1) | 55 (1) | 47 (1) | |

| 7 | 552 (6) | 29 (6) | 281 (7) | 242 (6) | |

| 8 | 280 (3) | 12 (2) | 134 (3) | 134 (3) | |

| 9 | 762 (9) | 110 (21) | 343 (8) | 309 (8) | |

| 10 | 420 (5) | 12 (2) | 225 (5) | 183 (5) | |

| 11 | 728 (8) | 30 (6) | 379 (9) | 319 (8) | |

| Time since listing (yr) | 2.9 (1.4–4.9) | 2.6 (1.3–4.5) | 2.8 (1.4–4.8) | 3.1 (1.5–5.2)a | <0.001 |

| PRA ≥98% | 687 (8) | 34 (7) | 322 (8) | 331 (9) | 0.12 |

| Preemptive (at death) | 1353 (16) | 83 (16) | 683 (16) | 587 (15) | 0.58 |

| Dialysis time (yr) if nonpreemptive | 4.6 (2.9–6.7) | 4.6 (3.1–6.3) | 4.4 (2.8–6.5) | 4.8 (3.1–6.9) | <0.001 |

M, male; GED, general educational development; WL, waitlist; BMI, body mass index; OPTN, Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network; PRA, panel reactive antibodies.

Denotes a significant pairwise P value (after Bonferroni multiple comparisons adjustment) compared with 2020.

Missing values excluded: 13 missing diabetes, 23 missing BMI.

Figure 1.

Comparison of the distribution of race and ethnicity among kidney transplant candidate or recipient deaths attributed to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in 2020, not attributed to COVID-19 in 2020, and in 2019. An asterisk (*) indicates statistical significance after a three-way Bonferroni multiple comparisons adjustment, and “ns” indicates not statistically significant.

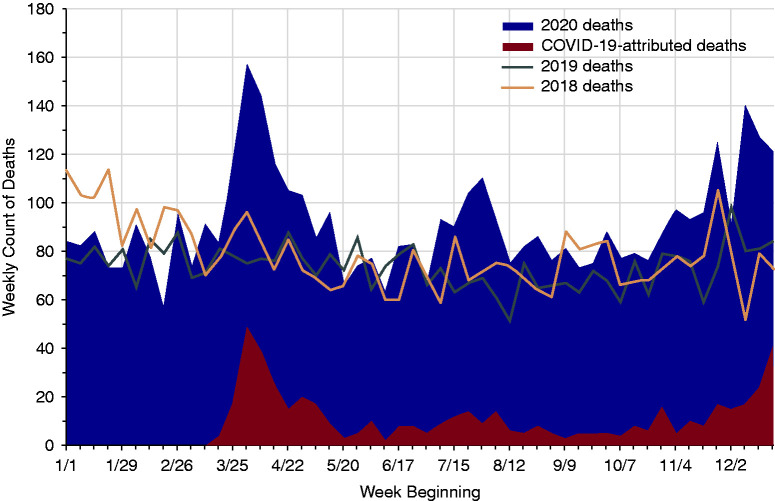

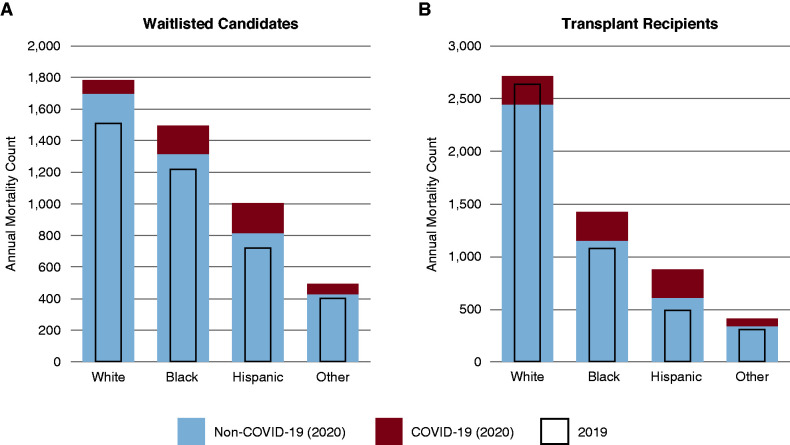

There was considerable variation in the geographic distribution of COVID-19 deaths among waitlisted candidates, with 21% of all COVID-19 deaths in this cohort reported in OPTN region 9, compared with just 8% of all non–COVID-19 deaths in 2020 in this region (Table 2). As a proportion of all deaths in a region, region 9 led with 24% of deaths attributed to COVID-19, followed by regions 4 (11%), 5 (11%), and 1 (10%). Region 6 had the fewest deaths on the waitlist attributed to COVID-19 in 2020, with only three deaths (5%). The total number of all-cause deaths on the waitlist in 2020 exceeded that in 2019 by 918 deaths, which was 24% higher than deaths occurring in 2019 and 16% higher (659 deaths) than in 2018. The all-cause mortality rate per 100 person-years among waitlisted candidates was 26% higher in 2020 compared with 2019, from a mortality rate of 3.87 (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 3.75 to 3.99) deaths per 100 person-years in 2019 to 4.87 (95% CI, 4.73 to 5.01) in 2020. The highest weekly number of COVID-19–related deaths among patients who were waitlisted was reported in the spring with 49 deaths in the week starting April 1, accounting for 31% of all reported deaths among candidates that week (Figure 2). There were excess all-cause deaths observed among candidates from all race/ethnicity subgroups in 2020 compared with 2019, but COVID-19 deaths accounted for a higher proportion of the 2020 deaths among Black and Hispanic candidates (Figure 3A).

Figure 2.

Number of deaths among waitlisted kidney transplant candidates in 2020 compared with deaths in 2019 and 2018 by week.

Figure 3.

Annual mortality counts. Deaths attributed to COVID-19 in 2020, deaths not attributed to COVID-19 in 2020, and deaths in 2019 among (A) waitlisted kidney transplant candidates and (B) active kidney transplant recipients by race/ethnicity.

Kidney Transplant Recipients

Nearly one in six deaths (16%) in 2020 among active transplant recipients in the United States were attributed to COVID-19. These individuals were notably younger and more likely to be obese than those who died of other causes, but, unlike waitlisted candidates, male recipients did not appear to be significantly over-represented among COVID-19 deaths (Table 3). Although White recipients represented more than half of non–COVID-19 deaths in 2020 and 2019 (54% and 59%, respectively), they represented only 30% of COVID-19–related deaths in 2020. This difference in the distribution of race/ethnicity across cause of death was driven by higher proportions of Hispanic (31%) and Black (31%) recipient deaths attributed to COVID-19 (Figure 1). In comparison, Hispanic and Black transplant recipients accounted for only 14% and 25%, respectively, of the non–COVID-19 deaths among transplant recipients in 2020 and 11% and 24% of deaths in 2019. Notably in 2020, there were actually fewer non–COVID-19 deaths among White recipients compared with 2019 and almost no excess all-cause deaths, which stands in stark comparison with the large numbers of excess deaths among Black and Hispanic recipients (Figure 3B).

Table 3.

Characteristics of active kidney transplant recipients who died in 2019, died in 2020 with a cause of death attributed to coronavirus disease 2019, or died in 2020 without a coronavirus disease 2019 cause of death code, from United Network for Organ Sharing registry data as of April 23, 2021

| Characteristics, Median (Interquartile Range) or n (%) | Deaths among Active Transplant Recipients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Deaths, 2019–2020 | Coronavirus Disease, 2019–2020 | Non–Coronavirus Disease, 2019–2020 | 2019 | Global P Value |

|

| (n=9962) | (n=893) | (n=4542) | (n=4527) | ||

| Age at time of death | 68 (60–74) | 65 (57–71) | 68 (60–74)a | 68 (61–75)a | <0.001 |

| Sex, M | 6374 (64) | 598 (67) | 2925 (64) | 2851 (63) | 0.06 |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.001 | ||||

| White | 5364 (54) | 269 (30) | 2443 (54)a | 2652 (59)a | |

| Black | 2505 (25) | 276 (31) | 1151 (25) | 1078 (24) | |

| Hispanic | 1370 (14) | 274 (31) | 610 (13) | 486 (11) | |

| Asian | 499 (5) | 40 (4) | 239 (5) | 220 (5) | |

| Other/multiracial | 224 (2) | 34 (4) | 99 (2) | 91 (2) | |

| Education level | <0.001 | ||||

| High school/GED or lower | 4680 (47) | 507 (57) | 2090 (46)a | 2083 (46)a | |

| Attended college/technical school | 2109 (21) | 185 (21) | 997 (22) | 927 (20) | |

| Associate or bachelor degree | 1532 (15) | 107 (12) | 729 (16) | 696 (15) | |

| Graduate degree | 750 (8) | 39 (4) | 351 (8) | 360 (8) | |

| N/A or unknown | 891 (9) | 55 (6) | 375 (8) | 461 (10) | |

| Primary payer at transplant | <0.001 | ||||

| Private | 2595 (26) | 178 (20) | 1199 (26)a | 1218 (27)a | |

| Public | 7217 (72) | 707 (79) | 3275 (72) | 3235 (71) | |

| Other/unknown | 150 (2) | 8 (1) | 68 (1) | 74 (2) | |

| History of diabetesb | 4746 (49) | 453 (52) | 2199 (49) | 2094 (48) | 0.04 |

| BMI at transplantb | 28.0 (24.4–32.0) | 29.0 (25.8–33.0) | 27.8 (24.3–31.9)a | 27.9 (24.3–31.9)a | <0.001 |

| Obese (BMI ≥30)b | 3627 (37) | 390 (44) | 1625 (36)a | 1612 (36)a | <0.001 |

| Blood group | 0.51 | ||||

| O | 4378 (44) | 400 (45) | 1998 (44) | 1980 (44) | |

| A | 3751 (38) | 317 (35) | 1742 (38) | 1692 (37) | |

| B | 1327 (13) | 124 (14) | 586 (13) | 617 (14) | |

| AB | 506 (5) | 52 (6) | 216 (5) | 238 (5) | |

| OPTN region | <0.001 | ||||

| 1 | 455 (5) | 32 (4) | 194 (4)a | 229 (5)a | |

| 2 | 1234 (12) | 77 (9) | 563 (12) | 594 (13) | |

| 3 | 1274 (13) | 93 (10) | 626 (14) | 555 (12) | |

| 4 | 783 (8) | 81 (9) | 375 (8) | 327 (7) | |

| 5 | 1275 (13) | 113 (13) | 589 (13) | 573 (13) | |

| 6 | 342 (3) | 17 (2) | 134 (3) | 191 (4) | |

| 7 | 1054 (11) | 90 (10) | 448 (10) | 516 (11) | |

| 8 | 709 (7) | 50 (6) | 342 (8) | 317 (7) | |

| 9 | 831 (8) | 172 (19) | 337 (7) | 322 (7) | |

| 10 | 1012 (10) | 78 (9) | 469 (10) | 465 (10) | |

| 11 | 993 (10) | 90 (10) | 465 (10) | 438 (10) | |

| Time since transplant, yr | 6.8 (3.1–11.4) | 4.8 (2.0–9.0) | 6.6 (2.9–11.1)a | 7.4 (3.7–11.9)a | <0.001 |

| <1 | 1102 (11) | 127 (14) | 518 (11)a | 457 (10)a | <0.001 |

| 1–5 | 2687 (27) | 335 (38) | 1284 (28) | 1068 (24) | |

| >5 | 6173 (62) | 431 (48) | 2740 (60) | 3002 (66) | |

| PRA ≥98%b | 425 (4) | 33 (4) | 199 (4) | 193 (4) | 0.64 |

| KDPI, if deceased donor transplantb | 47 (25–69) | 50 (31–70) | 47 (25–69)a | 46 (24–68)a | 0.004 |

| HLA mismatchb | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3–5)a | 0.0001 |

| Donor typeb | 0.02 | ||||

| Deceased | 7592 (76) | 708 (79) | 3483 (77) | 3401 (75)a | |

| Living | 2368 (24) | 185 (21) | 1058 (23) | 1125 (25) | |

| Preemptive (at transplant) | 1265 (13) | 68 (8) | 597 (13)a | 600 (13)a | <0.001 |

| Dialysis time (yr) if nonpreemptiveb | 3.5 (1.7–5.8) | 3.9 (2.0–6.4) | 3.5 (1.7–5.8)a | 3.3 (1.7–5.5)a | <0.001 |

M, male; GED, general educational development; WL, waitlist; BMI, body mass index; OPTN, Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network; PRA, panel reactive antibodies; KDPI, Kidney Donor Profile Index; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

Denotes a significant pairwise P value (after Bonferroni multiple comparisons adjustment) compared with 2020 COVID-19 deaths.

Missing values excluded: 242 missing diabetes, 63 BMI, 111 PRA, 168 KDPI, 31 HLA, two foreign donor type, 73 missing dialysis time.

There was a significantly greater proportion of recipients with high school or lower education among those who died of COVID-19 and fewer individuals with college education compared with both non–COVID-19 deaths in 2020 and deaths in 2019 (Table 3). Primary insurance payer was significantly associated with death due to COVID-19 among transplant recipients, but not among waitlisted candidates. Fewer recipients who died of COVID-19 had a private primary insurance payer at the time of transplant (20%) compared with non–COVID-19 deaths in 2020 (27%) and deaths in 2019 (28%). The largest number of COVID-19–related deaths were reported from region 9, which accounted for 19% of COVID-19 deaths among kidney transplant recipients although this region accounted for only 7% of all non–COVID-19–related deaths among kidney transplant recipients in 2020. Pretreatment dialysis exposure was associated with death from COVID-19, as transplant recipients who died from COVID-19 were less likely to have received a preemptive transplant and had been exposed to approximately 5–7 months more dialysis time if not preemptive. COVID-19 was also over-represented among recipients who died in 2020 within a year of their transplant, and recipients who died from COVID-19 had more recent transplants.

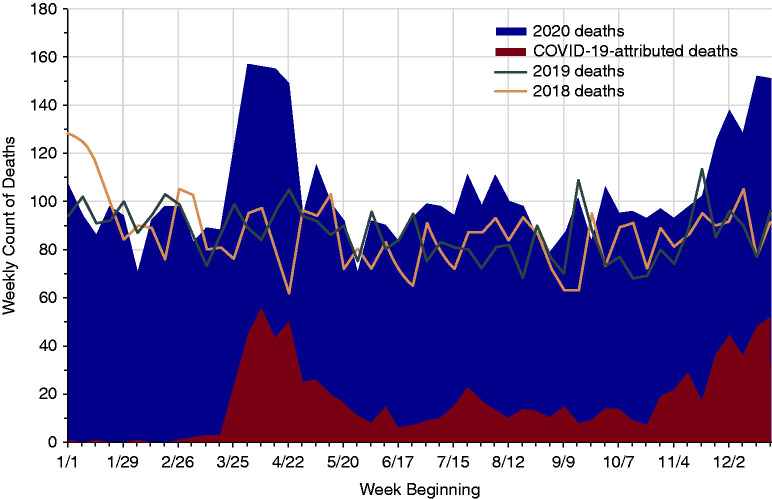

Among deaths reported in the UNOS database as of April 23, 2021, there were 908 and 896 additional deaths (all-cause) in 2020 compared with 2019 and 2018, respectively, each 20% higher compared with deaths in the prior years. There were 3.09 (95% CI, 3.01 to 3.18) all-cause deaths per 100 person-years in 2020 compared with 2.67 (95% CI, 2.59 to 2.75) in 2019, for a 16% higher mortality rate among active transplant recipients in 2020. The largest observed upward trend in recipient mortality in 2020 also occurred during the initial spring surge of the pandemic in the United States and reached a peak in the week of April 8, with 56 COVID-19–related deaths accounting for 36% of all deaths in kidney transplant recipients reported that week. Deaths began to rise above historic levels again at the end of 2020 with the beginning of the winter surge (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Number of deaths among active kidney transplant recipients in 2020 compared with deaths in 2019 and 2018 by week.

Discussion

The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on patients with advanced kidney disease has been unmistakable, with high mortality rates among patients with kidney failure coupled with reductions in transplantation activity (18,19). Our analysis identifies the burden of COVID-19–associated mortality among candidates waitlisted for a kidney transplant and active transplant recipients. Although single-center reports have largely focused on outcomes of recipients, we note 24% higher all-cause mortality on the transplant waitlist compared with the previous year. Although 11% of deaths on the waitlist in 2020 were attributed to COVID-19, the remainder of the difference in mortality observed is also likely to be COVID-19 related to the extent that the pandemic has adversely affected access to and delivery of health care, particularly during the peak of the initial surge.

Although mortality among active transplant recipients was also higher in 2020, the relative difference was smaller than that seen among waitlisted candidates. This difference in mortality among these cohorts is notable and likely driven by a variety of factors. Although we do not have data on the number of patients who were transplanted and waitlisted and infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, these groups likely had different rates of exposure and thus infection. The early heightened awareness of the higher risk for immunosuppressed individuals and protective behavior that would have resulted, including their ability to remain socially distanced, would have likely been protective. This stands in stark contrast to patients who were waitlisted and continued to receive in-center dialysis, which would have precluded complete social distancing. Given that most patients on dialysis in the United States receive in-center hemodialysis, waitlisted candidates are subject to repeated exposure to a health care setting where they may be exposed to COVID-19. Additionally, given evidence about the adverse prognostic implications of poor kidney function, patients with functioning kidney transplants might reasonably be expected to fare better than their counterparts who are on dialysis (20).

Differences in the racial/ethnic distribution of the groups who died of COVID-19 compared with other causes of death or deaths in 2019 are particularly startling, and are consistent with trends observed in the general population (21). Black and Hispanic patients together account for 50% of all non–COVID-19–related deaths on the waitlist, but were 72% of all COVID-19–related deaths. Similarly, these groups account for 39% of non–COVID-19–related deaths among transplant recipients but 62% of COVID-19–related deaths. Some studies have also suggested a possible association between ABO blood type and COVID-19 infection or outcomes, yet our results did not demonstrate any significant relationships between COVID-19 mortality and blood type among candidates or recipients (22,23).

We should note there may be delays or under-reporting of deaths to UNOS by individual transplant centers or from other sources of death data that depend in part on how actively centers monitor their waitlist or transplant population. Deaths attributed to COVID-19 may be undercounted, especially in the beginning months of the pandemic, due to challenges with incomplete testing and diagnosis of COVID-19. Deaths in the UNOS database very frequently have an “unknown” cause of death reported or are missing a code entirely; however, cause of death coding was more complete for deaths in 2020 than in 2019. Our analysis examining 2020 mortality in three ways (COVID-19 attributed, not attributed to COVID-19, and all-cause) in comparison with the pre–COVID-19 era may help overcome some of these limitations of the dataset, along with the restriction to only active transplant recipients with a last recorded follow-up date no >1 year before cohort entry on January 1. Given the continued effects of the pandemic throughout the United States with fall and winter surges, the actual counts of deaths in 2020 attributed to COVID-19 or other causes may rise if mortality reporting becomes more complete in the transplant databases.

The excess risk of COVID-19 mortality for both candidates and recipients may alter the amount of benefit associated with transplantation and affect clinical decision making. With considerable excess death observed among waitlisted candidates, patients who are high risk and on the waiting list may have greater incentive to accept higher risk donors or consider living donor transplantation to avoid remaining a candidate on dialysis. Recipients at particularly high risk may require increased monitoring or safety precautions during pandemic outbreaks. The risk calculation may also change as more evidence emerges on the efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines in specific subgroups of patients with kidney disease, including transplant recipients, patients on dialysis, and recipients who were vaccinated before transplantation.

In conclusion, our analysis demonstrates higher rates of mortality in 2020 associated with COVID-19 among waitlisted candidates and kidney transplant recipients in the United States and highlights the disproportionate burden of the pandemic on racial/ethnic minority groups among individuals with kidney disease.

Disclosures

J.D. Schold reports employment with Cleveland Clinic; consultancy agreements with Guidry and East, Novartis, Sanofi Corporation, and the Transplant Management Group; reports receiving honoraria from Novartis and Sanofi Inc.; reports serving as a scientific advisor or member of the Bristol Myers Squibb Data Safety Monitoring Board and Nephrosant; and serving on the speakers bureau for Sanofi. S.A. Husain reports receiving research funding from National Center for Advancing Translational Science and honoraria from the Renal Research Institute. S. Mohan reports having consultancy agreements with Angion Biomedica; reports receiving research funding from Angion Biomedica and National Institutes of Health (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities); and reports serving as Deputy Editor of Kidney International Reports (ISN), Vice Chair of UNOS Data advisory committee, a member of the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients Visiting Committee, a member of the American Society of Nephrology Quality committee, and the Angion Pharma scientific advisory board; and reports being supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grants U01-DK116066 and R01 DK114893 and U01 DK and National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities grant R01014161. This work was supported in part by Health Resources and Services Administration contract 234-2005-370011C. The remaining author has nothing to disclose.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grants U01 DK116066, R01 DK114893, U01 DK130058, and R01 DK126739 and National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities grant R01 MD014161, National Science Foundation award 2032726 (to J.D. Schold and S. Mohan) and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences grant KL2 TR001874 (to S.A. Husain).

Acknowledgments

S. Mohan and J.D. Schold were responsible for the research idea and study design; S. Mohan was responsible for data acquisition; K. King, S. Mohan, and J.D. Schold were responsible for data analysis and interpretation; and S.A. Husain, K. King, S. Mohan, and J.D. Schold drafted and revised the paper and approved the final version of the manuscript. The content is the responsibility of the authors alone and does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Rodrigo E, Miñambres E, Gutiérrez-Baños JL, Valero R, Belmar L, Ruiz JC: COVID-19-related collapse of transplantation systems: A heterogeneous recovery? Am J Transplant 20: 3265–3266, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azzi Y, Bartash R, Scalea J, Loarte-Campos P, Akalin E: COVID-19 and solid organ transplantation: A review article. Transplantation 105: 37–55, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loupy A, Aubert O, Reese PP, Bastien O, Bayer F, Jacquelinet C: Organ procurement and transplantation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 395: e95–e96, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li MT, King KL, Husain SA, Schold JD, Mohan S: Deceased donor kidneys utilization and discard rates during COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Kidney Int Rep 6: 2463–2467, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lentine KL, Vest LS, Schnitzler MA, Mannon RB, Kumar V, Doshi MD, Cooper M, Mandelbrot DA, Harhay MN, Josephson MA, Caliskan Y, Sharfuddin A, Kasiske BL, Axelrod DA: Survey of US living kidney donation and transplantation practices in the COVID-19 era. Kidney Int Rep 5: 1894–1905, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lentine KL, Mannon RB, Josephson MA: Practicing with uncertainty: Kidney transplantation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Kidney Dis 77: 777–785, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pereira MR, Mohan S, Cohen DJ, Husain SA, Dube GK, Ratner LE, Arcasoy S, Aversa MM, Benvenuto LJ, Dadhania DM, Kapur S, Dove LM, Brown RS Jr, Rosenblatt RE, Samstein B, Uriel N, Farr MA, Satlin M, Small CB, Walsh TJ, Kodiyanplakkal RP, Miko BA, Aaron JG, Tsapepas DS, Emond JC, Verna EC: COVID-19 in solid organ transplant recipients: Initial report from the US epicenter. Am J Transplant 20: 1800–1808, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azzi Y, Parides M, Alani O, Loarte-Campos P, Bartash R, Forest S, Colovai A, Ajaimy M, Liriano-Ward L, Pynadath C, Graham J, Le M, Greenstein S, Rocca J, Kinkhabwala M, Akalin E: COVID-19 infection in kidney transplant recipients at the epicenter of pandemics. Kidney Int 98: 1559–1567, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Montagud-Marrahi E, Cofan F, Torregrosa JV, Cucchiari D, Ventura-Aguiar P, Revuelta I, Bodro M, Piñeiro GJ, Esforzado N, Ugalde J, Guillén E, Rodríguez-Espinosa D, Campistol JM, Oppenheimer F, Moreno A, Diekmann F: Preliminary data on outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection in a Spanish single center cohort of kidney recipients. Am J Transplant 20: 2958–2959, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Husain SA, Dube G, Morris H, Fernandez H, Chang JH, Paget K, Sritharan S, Patel S, Pawliczak O, Boehler M, Tsapepas D, Crew RJ, Cohen DJ, Mohan S: Early outcomes of outpatient management of kidney transplant recipients with coronavirus disease 2019. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 1174–1178, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kates OS, Haydel BM, Florman SS, Rana MM, Chaudhry ZS, Ramesh MS, Safa K, Kotton CN, Blumberg EA, Besharatian BD, Tanna SD, Ison MG, Malinis M, Azar MM, Rakita RM, Morillas JA, Majeed A, Sait AS, Spaggiari M, Hemmige V, Mehta SA, Neumann H, Badami A, Goldman JD, Lala A, Hemmersbach-Miller M, McCort ME, Bajrovic V, Ortiz-Bautista C, Friedman-Moraco R, Sehgal S, Lease ED, Fisher CE, Limaye AP; UW COVID-19 SOT Study Team : COVID-19 in solid organ transplant: A multi-center cohort study [published online ahead of print August 7, 2020]. Clin Infect Dis [Google Scholar]

- 12.Columbia University Kidney Transplant Program : Early description of coronavirus 2019 disease in kidney transplant recipients in New York. J Am Soc Nephrol 31: 1150–1156, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chandorkar A, Coro A, Natori Y, Anjan S, Abbo LM, Guerra G, Mattiazzi AD, Mendez-Castaner LA, Morris MI, Camargo JF, Vianna R, Simkins J: Kidney transplantation during coronavirus 2019 pandemic at a large hospital in Miami. Transpl Infect Dis 22: e13416, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elias M, Pievani D, Randoux C, Louis K, Denis B, Delion A, Le Goff O, Antoine C, Greze C, Pillebout E, Abboud I, Glotz D, Daugas E, Lefaucheur C: COVID-19 infection in kidney transplant recipients: Disease incidence and clinical outcomes. J Am Soc Nephrol 31: 2413–2423, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Craig-Schapiro R, Salinas T, Lubetzky M, Abel BT, Sultan S, Lee JR, Kapur S, Aull MJ, Dadhania DM: COVID-19 outcomes in patients waitlisted for kidney transplantation and kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 21: 1576–1585, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akalin E, Azzi Y, Bartash R, Seethamraju H, Parides M, Hemmige V, Ross M, Forest S, Goldstein YD, Ajaimy M, Liriano-Ward L, Pynadath C, Loarte-Campos P, Nandigam PB, Graham J, Le M, Rocca J, Kinkhabwala M: Covid-19 and kidney transplantation. N Engl J Med 382: 2475–2477, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valeri AM, Robbins-Juarez SY, Stevens JS, Ahn W, Rao MK, Radhakrishnan J, Gharavi AG, Mohan S, Husain SA: Presentation and outcomes of patients with ESKD and COVID-19. J Am Soc Nephrol 31: 1409–1415, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsu CM, Weiner DE, Aweh G, Miskulin DC, Manley HJ, Stewart C, Ladik V, Hosford J, Lacson EC, Johnson DS, Lacson E Jr: COVID-19 among US dialysis patients: Risk factors and outcomes from a national dialysis provider. Am J Kidney Dis 77: 748–756.e1, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schold JD, King KL, Husain SA, Poggio ED, Buccini LD, Mohan S: COVID-19 mortality among kidney transplant candidates is strongly associated with social determinants of health. Am J Transplant 21: 2563–2572, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohamed NE, Benn EKT, Astha V, Okhawere KE, Korn TG, Nkemdirim W, Rambhia A, Ige OA, Funchess H, Mihalopoulos M, Meilika KN, Kyprianou N, Badani KK: Association between chronic kidney disease and COVID-19-related mortality in New York [published online ahead of print January 22, 2021]. World J Urol [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Webb Hooper M, Nápoles AM, Pérez-Stable EJ: COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities. JAMA 323: 2466–2467, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barnkob MB, Pottegard A, Støvring H, Haunstrup TM, Homburg K, Larsen R, Hansen MB, Titlestad K, Aagaard B, Møller BK, Barington T: Reduced prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in ABO blood group O. Blood Adv 4: 4990–4993, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zietz M, Zucker J, Tatonetti NP: Associations between blood type and COVID-19 infection, intubation, and death. Nat Commun 11: 5761, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]