Abstract

CKD affects 15% of US adults and is associated with higher morbidity and mortality. CKD disproportionately affects certain populations, including racial and ethnic minorities and individuals from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds. These groups are also disproportionately affected by incarceration and barriers to accessing health services. Incarceration represents an opportunity to link marginalized individuals to CKD care. Despite a legal obligation to provide a community standard of care including the screening and treatment of individuals with CKD, there is little evidence to suggest systematic efforts are in place to address this prevalent, costly, and ultimately fatal condition. This review highlights unrealized opportunities to connect individuals with CKD to care within the criminal justice system and as they transition to the community, and it underscores the need for more evidence-based strategies to address the health effect of CKD on over-represented communities in the criminal justice system.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, disparity, equity, prisoners

Introduction

Defined as kidney damage or GFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 for >3 months, CKD is a highly prevalent disease with significant effect on individual and public health (1,2). Fifteen percent of US adults, or 37 million people, are estimated to have CKD, yet approximately 90% of adults with CKD are unaware of their diagnosis (3). CKD can progress to kidney failure, which may require hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, or kidney transplantation to delay death. Additionally, CKD is associated with a higher risk of early death through cardiovascular disease, stroke, infections, cancer, and AKI (2–4).

Like many other chronic noncommunicable diseases, CKD disproportionately affects certain communities and demographic groups. CKD is more prevalent among older adults, ethnic minorities such as Hispanic and Black populations, and individuals of lower socioeconomic status (4,5). Black individuals experience almost three times greater incidence of kidney failure than their White peers while requiring tailored diagnostic approaches (6,7). There are many possible explanations for these disparities, including higher rates of risk factors for CKD in these populations, such as tobacco use, obesity, geospatial location, household poverty, and limited access to primary and specialty care (8–12).

Access to medical care is essential to avoiding the development of CKD and its progression to kidney failure. The two most common risk factors for CKD in the United States are diabetes and hypertension, both chronic diseases that if poorly controlled may potentially lead to kidney failure and the need for KRT (4,5). CKD is noted to be one of the most costly chronic diseases, with significant burdens on the health care system, caregiver costs, and costs associated with loss of productivity (13). In 2016, total Medicare spending for beneficiaries with a diagnosis of CKD exceeded $79 billion, up 23% from 2015 (6). When adding an extra $35 billion for kidney failure costs, total Medicare spending on individuals with CKD or kidney failure was over $114 billion, representing 23% of total Medicare fee-for-service spending (6). The Medicare data alone demonstrate that the financial burden for CKD is high (14).

The incarcerated population in the United States, around 2.1 million individuals (15), is over-represented by groups that disproportionately suffer from CKD, including racial and ethnic minorities and those with substance use disorders, such as alcohol and tobacco use, that are also associated with kidney dysfunction (9,12,16). Additionally, changes in demographic trends have led to an increasing number of elderly detained individuals facing a number of chronic health issues, including cardiovascular disease and other chronic health conditions associated with CKD (17). The prevalence of chronic diseases, as well as the aging incarcerated population, places increasing burdens on the individuals suffering from poor health, the correctional systems required to provide them with medical care, and the communities that individuals return to upon release from incarceration.

Health service availability and delivery in the US criminal justice system are highly variable, and there is relatively limited detailed information available. A recent survey of state correctional systems reported inconsistent availability of on-site testing such as electrocardiograms (18). Medical specialty care on-site availability is also highly variable, with certain states reporting on-site availability, others reporting exclusively off-site availability, and still others reporting a mix of both (18). This was also true of dialysis availability, with 24 states reporting dialysis services exclusively on site, another ten reporting dialysis services exclusively off site, and another ten reporting a mix of on-site and off-site service availability (18). The variability in health care delivery in correctional settings is also present globally, with limited population-level data on kidney pathology, including effective measures to prevent or manage CKD, available (19). This review summarizes the existing literature on CKD among people remanded to the criminal justice system, highlights areas of kidney pathology where little is known about the effect on those who are incarcerated, and identifies potential strategies for reducing the burden of kidney disease on this disproportionately affected population.

Risk Factors for CKD among Incarcerated Populations

Several demographic trends highlight concerns related to an increasing burden of chronic diseases that are linked to the disproportionate development of CKD and its progression in incarcerated populations. Imprisoned individuals are more likely to come from predominantly non-White communities, which are at higher risk of developing multiple chronic diseases (20). At the end of 2017, the US imprisonment rate of sentenced Hispanic and Black men was almost three times and six times that of sentenced White men, respectively (21). Individuals sentenced to the criminal justice system are more likely to be from communities of lower socioeconomic status, which alone is associated with a higher prevalence of chronic disease (22–25).

Age is also a risk factor for the development of CKD, and older incarcerated individuals make up the fastest growing demographics in the US prison system. Various estimates show that the number of incarcerated individuals aged 55 and older increased by 79% between 2000 and 2009 (26,27) and that the number of incarcerated individuals aged 65 and older increased by 282% from 1995 to 2010 (17). At the end of 2017, 12% of those sentenced to >1 year in state or federal prisons were age 55 or older; it has been estimated that by 2030, individuals aged 55 years or older will constitute over one third of the entire prison population (17,21).

In addition to demographic trends, a number of biobehavioral health trends are linked to the development of CKD in incarcerated populations. Obesity, a risk factor for numerous chronic health conditions linked to CKD, disproportionately affects Black individuals compared with their White peers, as well as incarcerated women compared with incarcerated men (28). Substance use, including tobacco, is another CKD risk factor that is prevalent in the incarcerated populations. In 2004, the national prevalence of people of all ages in state prisons who were current smokers was 39% of the prison population (29), compared with an estimated 21% of all US adults who reported currently smoking in 2004 (30). Alcohol and drug use disorders are also associated with higher prevalence of major medical conditions (31), including CKD (32), and have a higher prevalence in the incarcerated population in comparison with the general population. A meta-regression analysis across ten countries found that incarcerated individuals had an estimated 12-month prevalence of 24% of alcohol use disorder (33), compared with a 12-month prevalence of 14% of alcohol use disorder in the general US population in 2012–2013 (34). More than half (58%) of incarcerated individuals in state prisons and two thirds (63%) of individuals sentenced to jail met the criteria for drug dependence or abuse in 2007–2009, in comparison with approximately only 5% of the total general population age 18 or older (35).

With these demographic changes and trends in biobehavioral health in the overall prison population, chronic health conditions related to kidney dysfunction have become a growing concern in the prison system (36–38). In several large surveys of the health of incarcerated individuals, more than a third of those incarcerated suffered from a chronic medical illness, including 36% of individuals incarcerated in the federal system, 43% of those in state prisons, and 39% of those in local jails (39). In the same study, the prevalence rates of both diabetes and hypertension were higher in the criminal justice–involved population than in the general US population. The prevalence of diagnosed diabetes was 11% in the federal prison population, 10% in state prisons, and 8% in local jails, compared with 7% in the general US adult population (39). The prevalence of hypertension was 30% in federal prisons, 31% state prisons, and 28% local jail, compared with 26% in the general US adult population (39).

CKD among the Criminal Justice–Involved Population

Generally, little is known about the status of CKD among imprisoned individuals. In several large surveys of population health in the correctional setting, the prevalence of self-reported “persistent kidney problems” (without further definition) was noted to be highest in the federal prisons, with 6% of those detained in the federal system followed by 5% in the state penitentiary system and 4% in local jails (39). In a survey of newly detained individuals in maximum-security prisons in New York ages 16–64 years old, the prevalence of kidney disease was 2% (38). In a report published by the Bureau of Justice Statistics in February 2015, 6% of individuals incarcerated in state and federal correctional systems were reported to have “kidney-related problems” (without further definition) (40). However, surveys may significantly underestimate the prevalence of CKD, and nuanced data characterizing kidney disease trends in the correctional population are lacking.

There is also little peer-reviewed literature regarding dialysis and kidney transplantation during incarceration. Several peer-reviewed papers provide examples of correctional health systems that perform on-site dialysis or facilitate kidney transplantation (41–43), but these efforts are not analyzed or standardized at a national level. There are no published data on how many individuals are on the transplant list from the criminal justice setting or how many have already received kidney transplants while incarcerated.

The Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network laid out in a 2015 ethics paper that prisoners’ incarceration status “should not preclude them from consideration for a transplant,” adding, however, that “such consideration does not guarantee transplantation” (44). Many programs preclude prisoners from consideration for transplantation because of the logistical hurdles to bringing prisoners to hospitals on short notice and getting laboratory results rapidly (45). The University of Buffalo has maintained a program for transplantation of prisoners from a nearby correction facility for men. According to Gowda et al. (45), 45 prisoners were referred and 27 were listed for cadaveric kidney transplant between March 2013 and July 2018. Twenty transplants were performed in 18 prisoners. Graft survival rates were 94% at 1 year and 72% at 3 years (three graft failures and three unknown, no deaths). Although the authors argued that a kidney transplant program for prisoners can be successful, they noted the need for better long-term follow-up of transplant recipients. Others have argued for the need to make transplantation available to parolees (46). Ahmad and Eves (46) note in a recent article that although prisoners have a constitutional right to health care on the basis of the 1976 US Supreme Court ruling in Estelle v. Gamble (47), free (nonimprisoned) persons enjoy no such right under the Constitution. They argue that transplant centers and health care professionals have an ethical duty “to attend to the needs of parolees as a class.” Although Rhode Island Hospital is one of the centers that does not transplant prisoners while they are in prison, it has successfully listed and transplanted several people after they were released from the state prison.

Barriers to Management of CKD during and after Release from Incarceration

Although correctional systems are constitutionally required to provide community standard health care as outlined in Estelle v. Gamble, the Prison Litigation Reform Act substantially diminished the ability of people who are incarcerated to have the requirement for health care enforced. There is very little accountability or even data on access to, quantity, type, or quality of health care that is available for people who are incarcerated, despite the best efforts of organizations such as the National Commission on Correctional Healthcare and the American Correctional Association (48,49). Surveys have shown significant variability in health screening services, testing availability, and access to medical providers at correctional institutions throughout the country (50–52). Important yet basic health measures, such as BP screening and laboratory work measuring creatinine and blood glucose levels, may not be readily available to the many millions of individuals who pass through the criminal justice system annually. Yet, identifying CKD or its risk factors is impossible without these fundamental health screening capabilities.

At the same time, the post-prison release time frame is particularly crucial for individuals as they exit confinement. The risk of death after release from prison is highest during the first 2 weeks after release, with a >12-fold higher mortality risk compared with the general population (53). The mortality risk remains elevated for at least 4 weeks, with drug overdose as the most common cause of death among individuals recently released from prison, followed by cardiovascular disease, which is closely linked to kidney function (54).

There are significant barriers to promoting health postrelease, including accessing health care services upon release. Health insurance coverage is a crucial element to accessing health services and has historically been an important barrier to health care access in the United States for many individuals after release from prison (55). Medicaid is an important social safety net; yet, nearly all states have policies suspending or even terminating Medicaid benefits upon incarceration (56). For individuals who qualify for Medicaid benefits, they often must receive some case management or navigation assistance to reactivate or enroll in Medicaid coverage upon release, but availability of these services can be highly variable depending on the correction system and the state (57). The implementation of the Affordable Care Act expanded access to health insurance coverage with important implications for the criminal justice–involved population through expanded Medicaid coverage, although its implementation varies significantly by state (58,59).

In addition to a lack of insurance coverage, other barriers to accessing health care services include the stigma associated with a history of incarceration, difficulty finding a primary care provider, difficulty navigating the complex health system, and socioeconomic barriers often encountered by individuals postrelease, among others (60–62).

Interventions to Improve CKD and Associated Health Conditions for the Criminal Justice–Involved Population

Several studies have shown successful approaches to reducing health disparities among those experiencing incarceration, highlighting the need to address health inequities within the criminal justice system (63). Modifications to nutrition in prison can improve health, including reducing the prevalence of obesity and improving control of chronic diseases linked to CKD such as diabetes (64). Additionally, the implementation of tobacco bans in prison is associated with reductions in smoking-related mortality among those who are incarcerated, particularly cardiovascular and pulmonary deaths. However, it is important to note that the overall negative health aspects and expense of incarceration, especially the epidemic of mass incarceration in the United States, make it important to state emphatically that it is never appropriate to justify incarceration on the basis of an individual’s or population’s unmet health care needs.

In terms of the management of CKD and kidney failure in the prison setting, there are scant data. The University of Connecticut started a pilot for incarcerated individuals with kidney failure and showed that detained individuals are able to self-administer continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis while in prison (41). In the United Kingdom, a prison site near Sutton provided on-site hemodialysis starting in 2011, with the goal of improving adherence, providing continuity of care, and reducing escorting costs from the prison (43). The Erie County Medical Center protocol for obtaining kidney transplants for incarcerated individuals with kidney failure also included transplantation of kidneys from donors who were positive for hepatitis C virus to hepatitis C virus–positive recipients (45). Cost savings from the program if the allograft survived 2 years after transplant were estimated at $118,815 versus $131,256 if patients remained on dialysis, which would translate to an approximate overall cost reduction of $12,441 2 years post-transplant and $50,644 every year thereafter (42). Although limited in size and scope, these experiences highlight the feasibility of innovative programming to manage CKD, particularly in its advanced stages, as well as the informative role that cost-effectiveness analyses can have in assisting in population health decision making when considering costly interventions, such as dialysis and organ transplantation (65).

There are also a lack of data on interventions to improve the management of CKD when transitioning from incarceration to the community. In one proposed model of care, clinic programs focusing on the transition period from incarceration to the community link individuals to health care postincarceration using community health workers and clinicians to establish a relationship with individuals prior to release. They then facilitate postrelease clinical appointments as well as postrelease services to help individuals navigate the complex socioeconomic environment, with a focus on promoting and protecting the health of people newly released from prison (66). This approach has been effective in reducing postrelease emergency room visits for recently released individuals, but its efficacy at improving other health outcomes is less clear (60). There are now a number of such clinics around the country that try to connect incarcerated individuals with chronic health problems to primary care in the community postrelease (66–69).

Need for Future Action

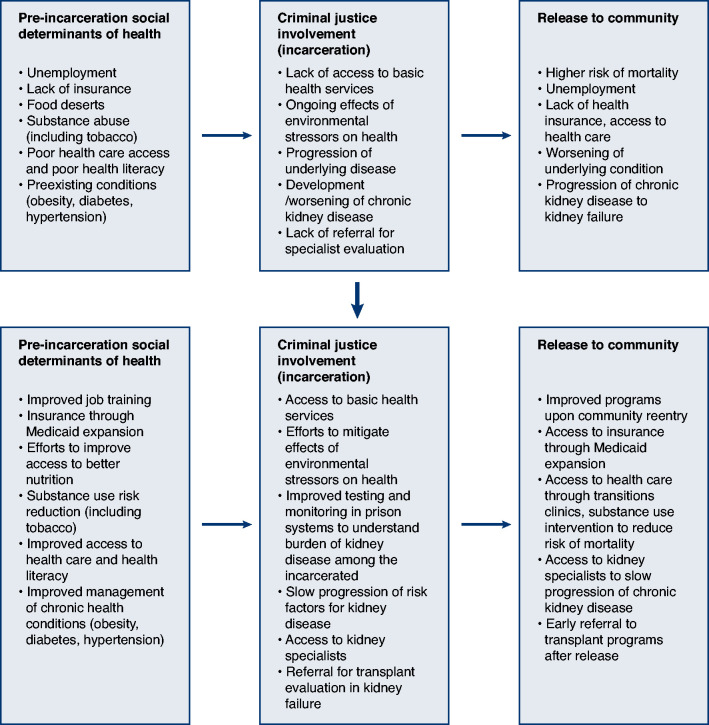

US prisons and jails are constitutionally required to provide health care to incarcerated individuals. The highly variable and mostly unknown availability of basic health screening and monitoring services, underscored by the general lack of knowledge of the burden of kidney disease, highlights the need for greater oversight to ensure that incarcerated individuals have access to community standard of care as legally required. Chronic noncommunicable diseases like CKD, kidney failure, and their major risk factors, diabetes and hypertension, are examples of conditions that necessitate structural change and innovative interventions to narrow health disparities that are more prevalent in criminal justice–involved populations compared with the general population (Figure 1). Effective screening, diagnostic, and treatment services are essential to identify and treat kidney dysfunction and its underlying causes, including hypertension, diabetes, and obesity. Given the number of individuals who pass through the criminal justice system and their known vulnerability to medical and socioeconomic conditions associated with kidney disease, there is a pressing need to understand the burden of CKD on the criminal justice–involved population and to develop a public health approach to ameliorating its disproportionate effect on those who experience incarceration (Table 1).

Figure 1.

The path to improve care for people with kidney disease in the criminal justice system.

Table 1.

Key action steps for the challenge of the significant yet largely uncharacterized burden of CKD among those involved with the criminal justice system

| Key Action Steps |

|---|

| 1. Implement essential health screening services, including BP evaluation upon entry into the criminal justice system |

| 2. Expand access to laboratory testing to evaluate for the presence of CKD and key associated conditions, such as diabetes |

| 3. Develop health-promoting interventions that prevent the development or progression of kidney disease |

| 4. Provide access to medical care to manage CKD and associated conditions, such as hypertension and insulin resistance |

| 5. Link individuals with CKD to care in the community upon release from incarceration |

| 6. Expand the evidence base to better understand the burden of CKD and interventions that improve kidney health outcomes |

Additionally, given the potential challenges of effectively managing the clinical care of CKD in the criminal justice setting, along with the known elevated risk of morbidity in the postrelease period, innovative approaches are needed to connect incarcerated individuals to health care services after they are released from prison to address the complex socioeconomic environment individuals encounter as well as the high rates of mortality particularly related to drug overdose and cardiovascular disease. The transition clinic model is a promising approach to addressing these needs, although a greater understanding of the effectiveness of interventions in preserving kidney health is needed. This is particularly true for individuals with advanced CKD, those who are dialysis dependent, and those who have received kidney transplants or might be eligible for one. With its increasing availability and use, both in the correctional setting and the community, telemedicine may provide an innovative approach for transitioning individual’s care to the community upon release from incarceration.

Finally, with an aging prison population that is also experiencing a growing burden of chronic disease, criminal justice systems can consider reassessing the criteria used for compassionate release and medical parole while developing a public health–informed decarceration strategy that seeks to protect the health of vulnerable incarcerated individuals while reducing the caregiver and financial burdens on correctional systems. The public health benefit of releasing people with chronic illness, like kidney failure/CKD, has been recently highlighted by the rapid spread, morbidity, and mortality among incarcerated people with CKD due to coronavirus disease 2019 (70). The experience of criminal justice systems during the pandemic underscores the need to revise compassionate release laws and regulations so that individuals with advanced chronic diseases are not placed at a higher health risk because of the uniquely challenging public health environment of incarceration.

Many men and women entering the criminal justice system bring with them chronic health problems as well as biobehavioral conditions that put them at risk of developing CKD, a progressive pathologic syndrome that, left untreated, may lead to permanent kidney failure and the need for KRT or death. Treating CKD in addition to diabetes, hypertension, substance use, and tobacco dependence while people are incarcerated and providing effective linkage to medical care in the community postrelease could mark a paradigm shift in the approach to managing chronic noncommunicable disease in this vulnerable and often marginalized population. Providing health care for incarcerated individuals before and after release could help people rejoin society as productive members after they have completed their sentences, with benefits that go beyond just reducing public health expenditures for KRT.

Disclosures

G. Bayliss reports employment with Brown Physicians Inc. (formerly University Medicine Foundation); reports serving as a scientific advisor or member of the Editorial Board of International Journal of Nephrology and Renovascular Disease (2016 to present), as a member of the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) Workforce Committee (2011–2015), as a member of the ASN Leadership Committee (2020), as a member of the Organ Procurement and Transplant Network Ethics Committee and region 1 representative (2020 to present), and as a member of the Editorial Board of Rhode Island Medical Journal (2021 to present); and is a donor of the ASN annual fund. J. Berk reports employment with Alpert Medical School at Brown University and Rhode Island Department of Corrections. A. Ding reports employment with Brown University and Lifespan. M. Murphy reports receiving research funding from Gilead Sciences and reports employment with the Rhode Island Department of Corrections and Brown Physicians Inc. J. Rich reports employment with Brown Physicians, Inc.; serving as a consultant to the Rhode Island Department of Corrections and a consultant to the Department of Homeland Security; being a stockholder in Ionis and Repligen; and serving as a member of the Board of Directors of The Drug Policy Alliance.

Funding

Support for this work was provided by National Institutes of Health grants LRP SCSE2410, P20GM125507, and P30AI042853.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.National Kidney Foundation : K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: Evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis 39: S1–S266, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group : KDIGO 2012 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int Suppl 3: 1–150, 2013. Available at: https://kdigo.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/KDIGO_2012_CKD_GL.pdf. Accessed April 26, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention : Chronic Kidney Disease in the United States, 2019. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/kidneydisease/publications-resources/CKD-national-facts.html. Accessed April 24, 2021

- 4.Webster AC, Nagler EV, Morton RL, Masson P: Chronic kidney disease. Lancet 389: 1238–1252, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drawz P, Rahman M: Chronic kidney disease. Ann Intern Med 162: ITC1–ITC16, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.United States Renal Data System : USRDS 2018 Annual Data Report Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. Available at: https://www.usrds.org/media/2282/2018_volume_1_ckd_in_the_us.pdf. Accessed April 27, 2020

- 7.Vyas DA, Eisenstein LG, Jones DS: Hidden in plain sight - Reconsidering the use of race correction in clinical algorithms. N Engl J Med 383: 874–882, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Volkova N, McClellan W, Klein M, Flanders D, Kleinbaum D, Soucie JM, Presley R: Neighborhood poverty and racial differences in ESRD incidence. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 356–364, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McClellan WM, Newsome BB, McClure LA, Howard G, Volkova N, Audhya P, Warnock DG: Poverty and racial disparities in kidney disease: The REGARDS study. Am J Nephrol 32: 38–46, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans K, Coresh J, Bash LD, Gary-Webb T, Köttgen A, Carson K, Boulware LE: Race differences in access to health care and disparities in incident chronic kidney disease in the US. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 899–908, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stenvinkel P, Zoccali C, Ikizler TA: Obesity in CKD--What should nephrologists know? J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 1727–1736, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bundy JD, Bazzano LA, Xie D, Cohan J, Dolata J, Fink JC, Hsu CY, Jamerson K, Lash J, Makos G, Steigerwalt S, Wang X, Mills KT, Chen J, He J; CRIC Study Investigators : Self-reported tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drug use and progression of chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 993–1001, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang V, Vilme H, Maciejewski ML, Boulware LE: The economic burden of chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease. Semin Nephrol 36: 319–330, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chapel JM, Ritchey MD, Zhang D, Wang G: Prevalence and medical costs of chronic diseases among adult Medicaid beneficiaries. Am J Prev Med 53[6S2]: S143–S154, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maruschak LM, Minton TD: Correctional populations in the United States, 2017-2018. Bur Justice Stat Bull August: 1–16, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pan CS, Ju TR, Lee CC, Chen YP, Hsu CY, Hung DZ, Chen WK, Wang IK: Alcohol use disorder tied to development of chronic kidney disease: A nationwide database analysis. PLoS One 13: e0203410, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skarupski KA, Gross A, Schrack JA, Deal JA, Eber GB: The health of America’s aging prison population. Epidemiol Rev 40: 157–165, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maruschak L, Chari KA, Simon AE, DeFrances CJ: National survey of prison health care: Selected findings. Natl Health Stat Rep 96: 1–23, 2016 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization : Prisons and Health, 2014. Available at: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/249188/Prisons-and-Health.pdf. Accessed April 21, 2021

- 20.Quiñones AR, Botoseneanu A, Markwardt S, Nagel CL, Newsom JT, Dorr DA, Allore HG: Racial/ethnic differences in multimorbidity development and chronic disease accumulation for middle-aged adults. PLoS One 14: e0218462, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bronson J, Carson A: Prisoners in 2017, 2019. Available at: http://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=6546%0A%0A. Accessed July 22, 2019

- 22.Sampson RJ, Loeffler C: Punishment’s place: The local concentration of mass incarceration. Daedalus 139: 20–31, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dennison CR, Demuth S: The more you have, the more you lose: Criminal justice involvement, ascribed socioeconomic status, and achieved SES. Soc Probl 65: 191–210, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weidner RR, Schultz J: Examining the relationship between U.S. incarceration rates and population health at the county level. SSM Popul Health 9: 100466, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaw KM, Theis KA, Self-Brown S, Roblin DW, Barker L: Chronic disease disparities by county economic status and metropolitan classification, behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 2013. Prev Chronic Dis 13: E119, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beck A, Harrison P: Prisoners in 2000. Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin, 2001. Available at: http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/p00.pdf. Accessed November 4, 2020

- 27.West HC, Sabo WJ, Greenman SJ: Prisoners in 2009. Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin, 2010. Available at: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/p09.pdf. Accessed November 4, 2020

- 28.Gates ML, Bradford RK: The impact of incarceration on obesity: Are prisoners with chronic diseases becoming overweight and obese during their confinement? J Obes 2015: 532468, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Binswanger IA, Carson EA, Krueger PM, Mueller SR, Steiner JF, Sabol WJ: Prison tobacco control policies and deaths from smoking in United States prisons: Population based retrospective analysis. BMJ 349: g4542, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) : Cigarette smoking among adults--United States, 2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 54: 1121–1124, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bahorik AL, Satre DD, Kline-Simon AH, Weisner CM, Campbell CI: Alcohol, cannabis, and opioid use disorders, and disease burden in an integrated health care system. J Addict Med 11: 3–9, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Novick T, Liu Y, Alvanzo A, Zonderman AB, Evans MK, Crews DC: Lifetime cocaine and opiate use and chronic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol 44: 447–453, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fazel S, Yoon IA, Hayes AJ: Substance use disorders in prisoners: An updated systematic review and meta-regression analysis in recently incarcerated men and women. Addiction 112: 1725–1739, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, Chou SP, Jung J, Zhang H, Pickering RP, Ruan WJ, Smith SM, Huang B, Hasin DS: Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry 72: 757–766, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bronson J, Stroop J, Zimmer S, Berzofsky M: Drug Use, Dependence, and Abuse among State Prisoners and Jail Inmates , 2007-2009. Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report, 2017. Available at: https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/dudaspji0709.pdf. Accessed November 10, 2020

- 36.Dumont DM, Brockmann B, Dickman S, Alexander N, Rich JD: Public health and the epidemic of incarceration. Annu Rev Public Health 33: 325–339, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahalt C, Trestman RL, Rich JD, Greifinger RB, Williams BA: Paying the price: The pressing need for quality, cost, and outcomes data to improve correctional health care for older prisoners. J Am Geriatr Soc 61: 2013–2019, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bai JR, Befus M, Mukherjee DV, Lowy FD, Larson EL: Prevalence and predictors of chronic health conditions of inmates newly admitted to maximum security prisons. J Correct Health Care 21: 255–264, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilper AP, Woolhandler S, Boyd JW, Lasser KE, McCormick D, Bor DH, Himmelstein DU: The health and health care of US prisoners: Results of a nationwide survey. Am J Public Health 99: 666–672, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maruschak LM, Berzofsky M, Unangst J: Medical Problems of State and Federal Prisoners and Jail Inmates, 2011-12. Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin, 2015. Available at: https://bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/mpsfpji1112.pdf. Accessed August 10, 2020

- 41.Sankaranarayanan N, Agrawal R, Guinipero L, Kaplan AA, Adams ND: Self-performed peritoneal dialysis in prisoners. Adv Perit Dial 20: 98–100, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Panesar M, Bhutani H, Blizniak N, Gundroo A, Zachariah M, Pelley W, Venuto R: Evaluation of a renal transplant program for incarcerated ESRD patients. J Correct Health Care 20: 220–227, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robinson C: On-site haemodialysis for prisoners with end-stage kidney disease. Nurs Times 114: 1–5, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network : Convicted Criminals and Transplant Evaluation. OPTN, 2015. Available at: https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/resources/ethics/convicted-criminals-and-transplant-evaluation/. Accessed April 24, 2021

- 45.Gowda M, Gundroo A, Lamphron B, Gupta G, Visger JV, Kataria A: Kidney transplant program for prisoners: Rewards, challenges and perspectives. Transplantation 104: 1967–1969, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahmad MU, Eves MM: The structural conundrum of parolees and kidney transplantation. Clin Transplant 34: e14104, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marshall T: Supreme Court. U.S. Reports: Estelle v. Gamble, 429 U.S. 97, 1976. Available at: https://www.loc.gov/item/usrep429097/. Accessed April 21, 2021

- 48.National Commission on Correctional Healthcare : NCCHC Historical Time Line, 2019. Available at: https://www.ncchc.org/time-line. Accessed April 21, 2021

- 49.American Correctional Association : The History of Standards & Accreditation. Available at: https://www.aca.org/ACA_Member/Standards___Accreditation/About_Us/ACA/ACA_member/Standards_and_Accreditation/SAC_AboutUs.aspx. Accessed November 10, 2020

- 50.Nunn A, Zaller N, Dickman S, Nijhawan A, Rich JD: Improving access to opiate addiction treatment for prisoners. Addiction 105: 1312–1313, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Solomon L, Montague BT, Beckwith CG, Baillargeon J, Costa M, Dumont D, Kuo I, Kurth A, Rich JD: Survey finds that many prisons and jails have room to improve HIV testing and coordination of postrelease treatment. Health Aff (Millwood) 33: 434–442, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nowotny KM: Health care needs and service use among male prison inmates in the United States: A multi-level behavioral model of prison health service utilization. Health Justice 5: 9, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Binswanger IA, Stern MF, Deyo RA, Heagerty PJ, Cheadle A, Elmore JG, Koepsell TD: Release from prison--A high risk of death for former inmates. N Engl J Med 356: 157–165, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Binswanger IA, Blatchford PJ, Mueller SR, Stern MF: Mortality after prison release: Opioid overdose and other causes of death, risk factors, and time trends from 1999 to 2009. Ann Intern Med 159: 592–600, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.National Commission on Correctional Health Care Board of Directors : Position statement: Optimizing insurance coverage for detainees and inmates postrelease. J Correct Health Care 21: 186–187, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morrissey JP, Steadman HJ, Dalton KM, Cuellar A, Stiles P, Cuddeback GS: Medicaid enrollment and mental health service use following release of jail detainees with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv 57: 809–815, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Healey KM: Case Management in the Criminal Justice System. National Institute of Justice Res Action, 1999. Available at: http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/nij. Accessed September 24, 2020

- 58.Rich JD, Chandler R, Williams BA, Dumont D, Wang EA, Taxman FS, Allen SA, Clarke JG, Greifinger RB, Wildeman C, Osher FC, Rosenberg S, Haney C, Mauer M, Western B: How health care reform can transform the health of criminal justice-involved individuals. Health Aff (Millwood) 33: 462–467, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Knapp CD, Howell BA, Wang EA, Shlafer RJ, Hardeman RR, Winkelman TNA: Health insurance gains after implementation of the Affordable Care Act among individuals recently on probation: USA, 2008-2016. J Gen Intern Med 34: 1086–1088, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang EA, Hong CS, Shavit S, Sanders R, Kessell E, Kushel MB: Engaging individuals recently released from prison into primary care: A randomized trial. Am J Public Health 102: e22–e29, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fahmy N, Kouyoumdjian FG, Berkowitz J, Fahmy S, Neves CM, Hwang SW, Martin RE: Access to primary care for persons recently released from prison. Ann Fam Med 16: 549–551, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hadden KB, Puglisi L, Prince L, Aminawung JA, Shavit S, Pflaum D, Calderon J, Wang EA, Zaller N: Health literacy among a formerly incarcerated population using data from the transitions clinic network. J Urban Health 95: 547–555, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dumont DM, Allen SA, Brockmann BW, Alexander NE, Rich JD: Incarceration, community health, and racial disparities. J Health Care Poor Underserved 24: 78–88, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Firth CL, Sazie E, Hedberg K, Drach L, Maher J: Female inmates with diabetes: Results from changes in a prison food environment. Womens Health Issues 25: 732–738, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Luyckx VA, Tonelli M, Stanifer JW: The global burden of kidney disease and the sustainable development goals. Bull World Health Organ 96: 414–422D, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang EA, Hong CS, Samuels L, Shavit S, Sanders R, Kushel M: Transitions clinic: Creating a community-based model of health care for recently released California prisoners. Public Health Rep 125: 171–177, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Baillargeon JG, Giordano TP, Harzke AJ, Baillargeon G, Rich JD, Paar DP: Enrollment in outpatient care among newly released prison inmates with HIV infection. Public Health Rep 125: 64–71, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fox AD, Anderson MR, Bartlett G, Valverde J, Starrels JL, Cunningham CO: Health outcomes and retention in care following release from prison for patients of an urban post-incarceration transitions clinic. J Health Care Poor Underserved 25: 1139–1152, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fox AD, Anderson MR, Bartlett G, Valverde J, MacDonald RF, Shapiro LI, Cunningham CO: A description of an urban transitions clinic serving formerly incarcerated people. J Health Care Poor Underserved 25: 376–382, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine : Decarcerating Correctional Facilities during COVID-19: Advancing Health, Washington, DC, Equity, and Safety, 2020 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]