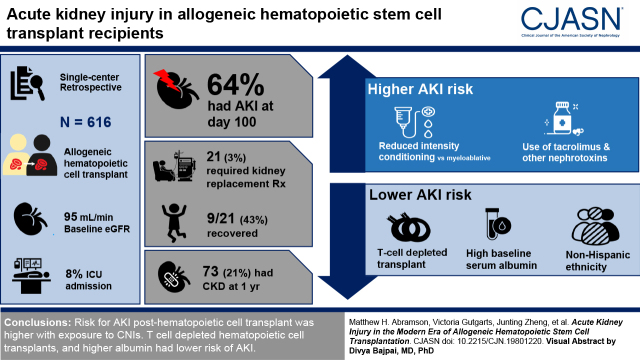

Visual Abstract

Keywords: onconephrology, bone marrow transplant, stem cell transplant, acute kidney injury, chronic kidney disease, graft vs host disease, gvhd, hemodialysis, drug nephrotoxicity, thrombotic microangiopathy

Abstract

Background and objectives

AKI is a major complication of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, increasing risk of nonrelapse mortality. AKI etiology is often ambiguous due to heterogeneity of conditioning/graft versus host disease regimens. To date, graft versus host disease and calcineurin inhibitor effects on AKI are not well defined. We aimed to describe AKI and assess pre–/post–hematopoietic transplant risk factors in a large recent cohort.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

We performed a single-center, retrospective study of 616 allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant recipients from 2014 to 2017. We defined AKI and CKD based on Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) criteria and estimated GFR using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation. We assessed AKI pre–/post–hematopoietic transplant risk factors using cause-specific Cox regression and association of AKI with CKD outcomes using chi-squared test. AKI was treated as a time-dependent variable in relation to nonrelapse mortality.

Results

Incidence of AKI by day 100 was 64%. Exposure to tacrolimus and other nephrotoxins conferred a higher risk of AKI, but tacrolimus levels were not associated with severity. Reduced-intensity conditioning carried higher AKI risk compared with myeloablative conditioning. Most stage 3 AKIs were due to ischemic acute tubular necrosis and calcineurin inhibitor nephrotoxicity. KRT was initiated in 21 out of 616 patients (3%); of these 21 patients, nine (43%) recovered and five (24%) survived to hospital discharge. T cell–depleted transplants, higher baseline serum albumin, and non-Hispanic ethnicity were associated with lower risk of AKI. CKD developed in 21% (73 of 345) of patients after 12 months. Nonrelapse mortality was higher in those with AKI (hazard ratio, 2.77; 95% confidence interval, 1.8 to 4.27).

Conclusions

AKI post–hematopoietic cell transplant remains a major concern. Risk of AKI was higher with exposure to calcineurin inhibitors. T cell–depleted hematopoietic cell transplants and higher serum albumin had lower risk of AKI. Of the patients requiring KRT, 43% recovered kidney function.

Podcast

This article contains a podcast at https://www.asn-online.org/media/podcast/CJASN/2021_09_07_CJN19801220.mp3

Introduction

The use of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation continues to increase worldwide (1), with improving overall outcomes (2). Compared with 2003–2007, the period from 2013 to 2017 showed reduced mortality, graft versus host disease (GVHD), and AKI (2). There remains concern over modifiable risk factors affecting survival, such as AKI. The effect of current conditioning and GVHD prophylaxis regimens over kidney outcomes is not well described in the literature. Incidence of AKI post–hematopoietic transplantation is high, from 16% (3) to 85% (4), depending on the definition (Supplemental Table 1). “Doubling of creatinine” was initially used to define AKI in this population (5,6), followed by RIFLE (Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss, ESKD) (7), Acute Kidney Injury Network (8), eGFR decline >25% (9), and Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) criteria (10).

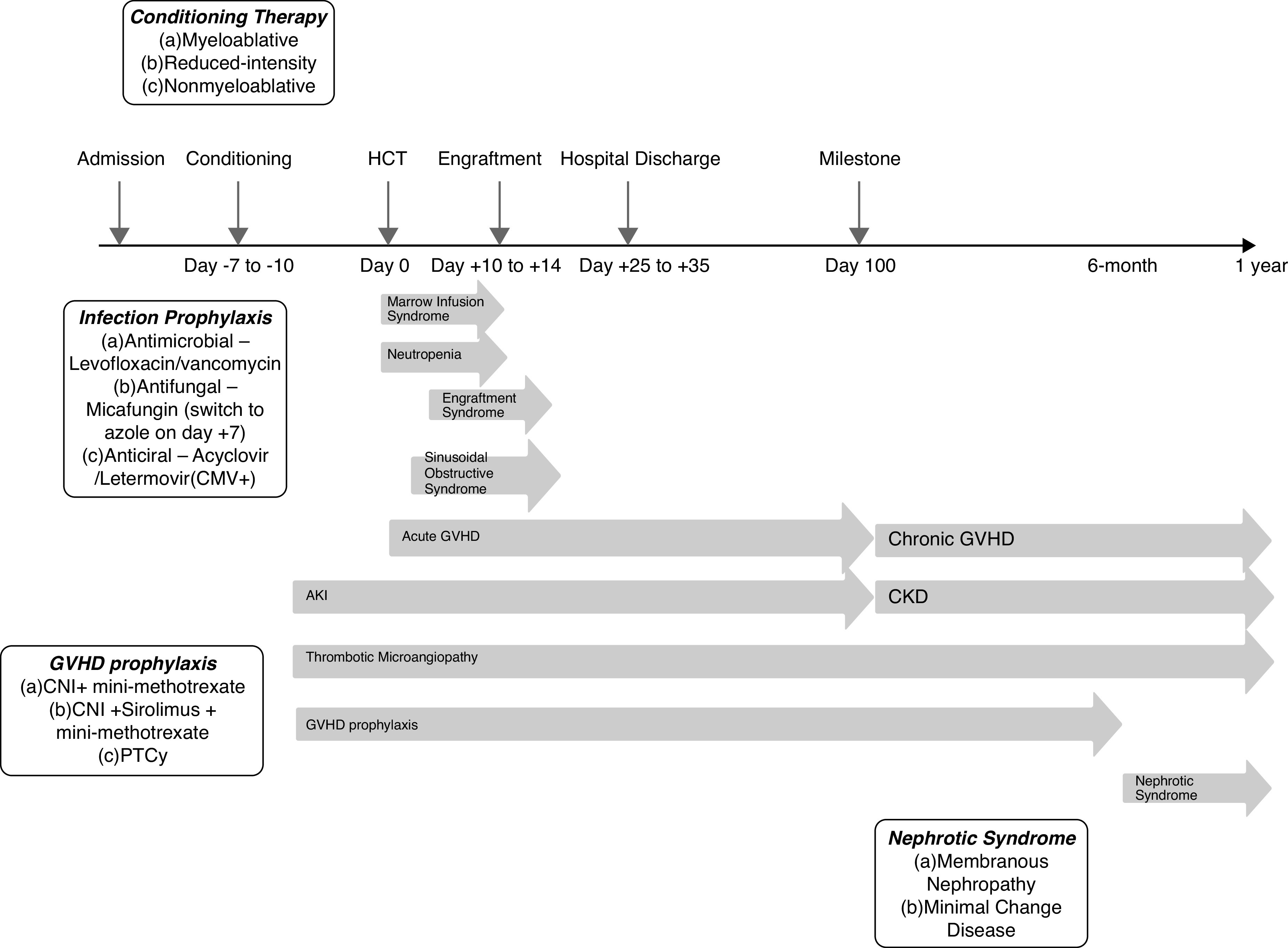

AKI post–hematopoietic cell transplantation is associated with high mortality (4,11), especially within the first 2–4 weeks (4,12). Among patients requiring KRT, mortality of 100% has been reported (13). Data are conflicting regarding the association of calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) (5) and GVHD (4 –6,14 –16) on AKI. Conditioning regimens have changed over time, and candidates at higher risk are increasingly considered for transplantation. Figure 1 highlights important milestones and complications during the first year post–hematopoietic cell transplantation.

Figure 1.

Timeline of important milestones and complications in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation from transplant admission through 1-year follow-up. CMV, cytomegalovirus; CNI, calcineurin inhibitor; GVHD, graft versus host disease; HCT, hematopoietic cell transplantation; PTCy, post-transplant cyclophosphamide.

In a large and recent cohort of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant recipients, we describe the incidence of AKI and identify pre- and post-transplant risk factors that are potentially modifiable to limit progression to CKD and improve outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

We evaluated 616 consecutive patients aged >18 years undergoing their first allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation from 2014 to 2017 at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Kidney injury after cord blood transplantation at our center has been previously described and, hence, excluded (17). AKI was defined using KDIGO criteria as follows: stage 1 (creatinine rise ≥0.3 mg/dl or 1.5× baseline), stage 2 (2× baseline), and stage 3 (3× baseline) AKI occurring up to 100 days post–hematopoietic cell transplant. All patients requiring one or more sessions of KRT were considered to have stage 3 AKI. We defined severe AKI as stage 2–3 AKI. Baseline creatinine was defined as the level on admission for transplantation, before receiving conditioning chemotherapy, which is usually given 10–15 days pretransplant. Baseline eGFR was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) formula (18). Baseline CKD was defined as admission eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Onset of AKI was defined as when AKI criteria were initially met, and maximum AKI as the onset of the highest AKI stage. Day 100 was chosen as a landmark used to study early versus late complications post-transplant, consistent with prior studies (5), and included both inpatient and outpatient laboratory test values.

Conditioning was myeloablative, reduced intensity, or nonmyeloablative, depending on underlying patient characteristics, including the hematopoietic cell transplantation–specific comorbidity index (HCT-CI); see Table 1. HCT-CI incorporates comorbidities associated with nonrelapse mortality: cardiac, kidney, hepatic, and pulmonary comorbidities (19,20). Myeloablative conditioning was used for patients with leukemia, higher risk for GVHD, and lower risk for nonrelapse mortality, on the basis of the HCT-CI. Myeloablative regimens included high-dose total-body irradiation (TBI)–based (1375 cGy) or chemotherapy. Conditioning was considered “modified” when T cells were removed ex vivo to eliminate the need for GVHD prophylaxis. Transplants without T-cell depletion were considered “unmodified.” Reduced-intensity conditioning was used in patients with lymphoma, lower risk for GVHD, and higher risk for nonrelapse mortality. Reduced-intensity regimens included combination chemotherapy and low-dose TBI-based regimens (400 cGy). Nonmyeloablative conditioning was used in patients with residual disease requiring graft versus leukemia effect of donor T cells (21), lower risk for GVHD, and highest risk for nonrelapse mortality. Nonmyeloablative regimens included low-dose TBI (200 cGy) regimens and chemotherapy (22).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and demographics of recipients of HCT

| Characteristic | Values (n=616) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 252 (41) |

| Male | 364 (59) |

| Age (yr), median (IQR) | 58 (19–79) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 512 (83) |

| Black | 36 (6) |

| Asian/Far East/Indian Subcontinent | 29 (5) |

| Other | 39 (6) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic/Latino, n (%) | 39 (9) |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino, n (%) | 403 (91) |

| Not reported, n | 174 |

| Disease, n (%) | |

| Hodgkin disease | 15 (2) |

| Leukemia | 303 (49) |

| Multiple myeloma | 61 (10) |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 99 (16) |

| Myeloproliferative disorder | 24 (4) |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 100 (17) |

| Nonmalignant disorders | 14 (2) |

| Risk, n (%) | |

| High | 162 (26) |

| Intermediate | 131 (21) |

| Low | 264 (43) |

| Not applicable | 59 (10) |

| BMI (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 27.2 (23.8–30.8) |

| Baseline albumin (g/dl), median (IQR) | 3.5 (3.3–3.8) |

| Baseline creatinine (mg/dl), median (IQR) | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) |

| Baseline eGFR (ml/min), median (IQR) | 95 (80–120) |

| Baseline eGFR (ml/min), n (%) | |

| <60 | 35 (6) |

| ≥60 | 581 (94) |

| HCT-CI score, median (IQR) | 3 (1–4) |

| HCT-CI score, n (%) | |

| 0 | 107 (17) |

| 1–2 | 195 (32) |

| ≥3 | 314 (51) |

| GVHD prophylaxis group, n (%) | |

| TCD | 242 (39) |

| Tacrolimus/methotrexate | 263 (43) |

| Tacrolimus/sirolimus/methotrexate | 37 (6) |

| PTCy-based | 71 (12) |

| Other | 3 (0.5) |

| TCD, n (%) | 242 (39) |

| Conditioning intensity, n (%) | |

| Myeloablative | 367 (60) |

| Nonmyeloablative | 50 (8) |

| Reduced intensity | 199 (32) |

| Conditioning regimen | |

| Chemotherapy based, n (%) | 462 (75) |

| Busulfan/melphalan/fludarabine, n | 178 |

| Fludarabine/busulfan, n | 231 |

| Melphalan/thiotepa/fludarabine, n | 27 |

| Other, n | 26 |

| TBI based, n (%) | 154 (25) |

| Cyclophosphamide/fludarabine, n | 39 |

| Cyclophosphamide/fludarabine/thiotepa, n | 28 |

| Cyclophosphamide/thiotepa, n | 63 |

| Other, n | 24 |

| TBI group, n (%) | |

| Low-dose TBI (200–400cGy) | 80 (52) |

| High-dose TBI (1375cGy) | 74 (48) |

| Conditioning intensity, stratified by TBI versus chemotherapy, n (%) | |

| Myeloablative, high-dose TBI | 74 (12) |

| Myeloablative, chemotherapy | 293 (8) |

| Nonablative, low-dose TBI (200cGy) | 50 (8) |

| Reduced intensity, chemotherapy | 168 (27) |

| Reduced intensity, low-dose TBI (400cGy) | 31 (5) |

| HLA, n (%) | |

| Related haploidentical | 47 (8) |

| Related identical sibling | 178 (29) |

| Related nonidentical | 1 (0.2) |

| Related twin | 2 (0.3) |

| Unrelated identical | 327 (53) |

| Unrelated nonidentical | 61 (10) |

| Donor CMV, n (%) | |

| Negative | 316 (51) |

| Positive | 298 (49) |

| Patient CMV, n (%) | |

| Negative | 259 (42) |

| Positive | 351 (57) |

HCT, hematopoietic cell transplant; IQR, interquartile range; BMI, body mass index; HCT-CI, hematopoietic cell transplant–specific comorbidity index; GVHD, graft versus host disease; TCD, T cell–depleted transplant; PTCy, post-transplantation cyclophosphamide; TBI, total-body irradiation; CMV, cytomegalovirus.

GVHD prophylaxis comprised cyclophosphamide, tacrolimus, tacrolimus/sirolimus, or T-cell depletion without pharmacologic immunosuppression. Within the first 100 days, the target range of tacrolimus was 6–12 ng/ml (10–15 ng/ml earlier in the study), or 5–10 ng/ml if combined with sirolimus. The therapeutic range for sirolimus was 4–12 ng/dl (9–12 ng/dl earlier) or, with tacrolimus, 3–9 ng/dl. Tacrolimus prophylaxis included 5 mg/m2 methotrexate on days +3, +6, and +11. With myeloablative conditioning, vancomycin was given from days −2 to +7 and levofloxacin was given until engraftment. For febrile neutropenia, vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam were used. GVHD prophylaxis with CNI use is continued until 3–6 months post-transplant, followed by a 10%–15% taper every few weeks. This may be altered if GVHD develops. In absence of complications, patients are usually off immunosuppression by 1 year post-transplant.

Variables

Pretransplant variables included demographics (age, race, ethnicity, body mass index [BMI]), serum albumin, HCT-CI score (19), cytomegalovirus (CMV) status, HLA match, and conditioning and GVHD prophylaxis regimens. HCT-CI scores were categorized as follows: low risk, score of zero; intermediate risk, one to two; and high risk, three or more. Post-transplant variables included bacteremia; admission to the intensive care unit; and exposure to vancomycin, tacrolimus/sirolimus, and other nephrotoxic medications (cidofovir, foscarnet, gentamicin, and amphotericin). All creatinine/eGFR values from admission through 100 days post-transplant were assessed, and, additionally, the closest creatinine/eGFR values to day +180 and day +360 post-transplant. For all post-transplant variables, we considered exposure occurring any time before maximum-stage AKI onset. Engraftment was defined when absolute neutrophil count reached >500/μl, with peri-engraftment defined as days −3 to +7 of engraftment (23).

We first analyzed association between pre- and post-transplant variables and development of any AKI. We then grouped together mild (stage 1) AKI with no AKI, as comparison against severe (stage 2–3) AKI to improve the strength of our analysis. Mean vancomycin and tacrolimus levels in the 7 days preceding maximum-stage AKI were compared among AKI stages. Etiologies of stage 3 AKI were independently ascertained by the authors via chart review. We defined prerenal AKI as hypovolemia and resolution with fluids. We used LeukemiaNet International Working Group criteria for defining thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) (24). Ischemic acute tubular necrosis (ATN) was diagnosed using fractional excretion of sodium >1%, granular casts on urinalysis, hypotension, and lack of supratherapeutic CNI level. We assessed the effect of AKI on nonrelapse mortality, defined as death in the absence of disease relapse, categorized as infections, GVHD, and/or organ failure (25). Finally, we calculated the risk of CKD at 6 months and at 12 months on the basis of AKI severity. CKD stages were defined per KDIGO guidelines (26).

Patients were followed thrice weekly until day +100. From day +100 until 1 year post-transplant, monitoring changed from monthly to every 4 months, depending on clinical status. Most patients reliably had post-transplant laboratory values at 6-month and 12-month time points, which were used for CKD analysis.

Statistical Analyses

We estimated cumulative risks of nonrelapse mortality and AKI. Pre- and post-transplant variable associations with AKI risk were analyzed using the cause-specific Cox regression, with post-transplant variables analyzed as time dependent. In the nonrelapse mortality analysis, AKI was treated as a time-dependent variable. We examined two outcomes within 100 days: (1) time to any stage AKI, and (2) time to maximum stage 2–3 AKI. Time to AKI was defined from transplant date to onset date of maximum-stage AKI. Patients who did not develop AKI were censored on day 100 or at second transplant. Relapse, progression, and death were competing events in the estimation of cumulative incidence of maximum-stage AKI related to the transplant. The Fisher exact test compared vancomycin and tacrolimus levels with AKI stages 1–3. Transplant-related CKD risk was explored at 6- and 12-month landmarks, including only patients who were alive and progression-/relapse-free. At each time point, chi-squared tests compared the risk of CKD between patients who had different AKI stages. Statistical analyses were performed in R version 3.6.

Results

Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

The analysis included 616 patients who received their first allogeneic transplants. Table 1 summarizes their baseline characteristics. Median follow-up was 35.7 months (interquartile range [IQR], 24.6–46.9). Most patients, 512 (83%), were White, 36 (6%) were Black, and 29 (5%) were Asian. There were 364 (59%) males, compared with 252 (41%) females. Indication was acute leukemia in 302 (49%) patients. On the basis of HCT-CI, 107 (17%) patients were low risk, 195 (32%) were intermediate risk, and 314 (51%) were high risk. Median (IQR) baseline creatinine was 0.8 ( 0.7–0.9) mg/dl and eGFR was 95 (80–120) ml/min per 1.73 m2. Conditioning was myeloablative in 367 (60%), reduced intensity in 199 (32%), and nonmyeloablative in 50 (8%) patients. A total of 35 (6%) patients had baseline CKD; 51 (8%) patients had intensive care unit admission.

AKI Outcomes

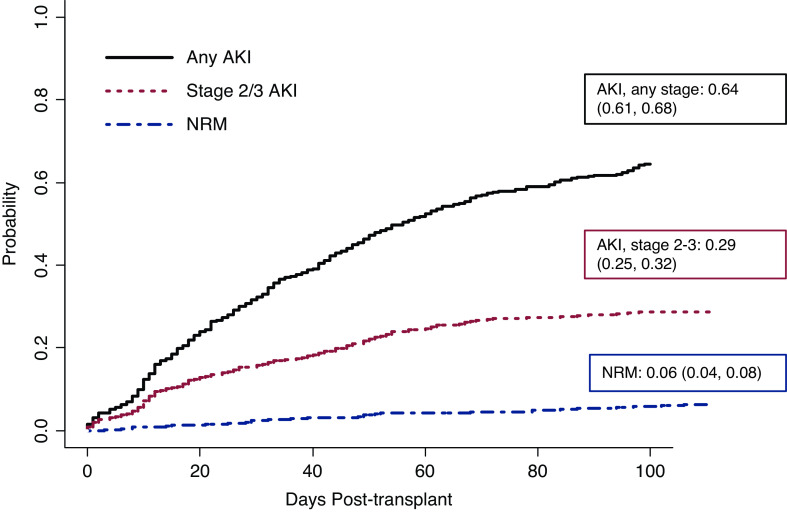

The cumulative incidence of any stage AKI of all comers was 65% (403 of 616). When excluding those who relapsed or died before AKI onset, AKI incidence was 64% (397 of 616); see Figure 2. In all comers with AKI, time to onset was 17 (IQR, 8–35) days and time to maximum stage was 31 (IQR, 13–53.5) days. AKI stage 1 occurred in 220 (36%), stage 2 in 119 (19%), and stage 3 in 64 (10%) patients. Severe (stages 2 and 3) AKI occurred in 30% (183 of 616) of patients. Median (IQR) onset for maximum AKI stage 1 and stage 2 were similar, 32 (16–58) and 31 (12–49) days, respectively, whereas the median (IQR) onset for maximum AKI stage 3 was 16 (9–49) days (Supplemental Table 2). The cumulative incidence of maximum AKI stage 1 was 7% at day 14 and 17% at day 30, compared with maximum stage 2 AKI of 6% and 9%, and, for stage 3 AKI, 5% and 6%, respectively. KRT within 100 days post-transplant was provided in 21 (3%) patients. Any AKI (hazard ratio [HR], 2.77; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.8 to 4.27) and severe AKI (HR, 2.47; 95% CI, 1.73 to 3.54) were associated with higher risk of nonrelapse mortality (Figure 2). At 6 months, nonrelapse mortality was 2% in patients without AKI, compared with 3% in maximum AKI stage 1, 4% in stage 2, and 14% in stage 3 (Supplemental Table 3). AKI in the peri-engraftment period occurred in 118 (29%) patients (stage 1, 55 of 220; stage 2, 40 of 119; and stage 3, 23 of 64). Additional AKI outcomes stratified by transplant and GVHD prophylaxis regimens are shown in Supplemental Table 4.

Figure 2.

High cumulative incidence of AKI in allogeneic stem cell transplant recipients. Cumulative incidence of any AKI and severe (stage 2 and 3) AKI in relation to nonrelapse mortality (NRM). n=591; 25 were patients omitted due to competing events (progression, relapse, death before AKI onset). Boxed numbers indicate day-100 cumulative incidence rate (95% confidence interval).

Pretransplant Risk Factors for AKI

Unadjusted analysis of risk factors for any stage and severe AKI is shown in Table 2. AKI was higher with increasing age (HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.1) and high-risk HCT-CI score (HR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.11 to 1.96). Reduced-intensity conditioning conferred higher risk compared with myeloablative conditioning (HR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.7 to 2.61). AKI was lower in T cell–depleted transplants (HR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.38 to 0.62).

Table 2.

Unadjusted analysis for any stage and severe (stage 2–3) AKI

| Variables | HR (95% CI) | |

| Any AKI | Severe (Stage 2–3) AKI | |

| Patient-specific variables | ||

| Age, per 5 years | 1.06 (1.02 to 1.10) | 1.01 (0.95 to 1.07) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | Reference | Reference |

| Male | 1.17 (0.96 to 1.44) | 0.74 (0.55 to 1.00) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | Reference | Reference |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 0.82 (0.55 to 1.22) | 0.47 (0.28 to 0.77) |

| Unknown | 1.04 (0.68 to 1.58) | 0.67 (0.40 to 1.14) |

| HCT-CI score | ||

| 0 | Reference | Reference |

| 1–2 | 1.01 (0.75 to 1.38) | 0.79 (0.5 to 1.25) |

| ≥3 | 1.48 (1.11 to 1.96) | 1.4 (0.93 to 2.1) |

| Baseline albumin (g/dl) a | 0.93 (0.71 to 1.22) | 0.59 (0.4 to 0.87) |

| Transplant-specific variables | ||

| Conditioning group | ||

| Chemotherapy | Reference | Reference |

| TBI | 0.69 (0.54 to 0.88) | 0.84 (0.59 to 1.20) |

| GVHD prophylaxis group | ||

| TCD | Reference | Reference |

| Tacrolimus based | 2.21 (1.72 to 2.84) | 1.8 (1.26 to 2.58) |

| Tacrolimus/sirolimus based | 2.02 (1.4 to 2.92) | 1.95 (1.13 to 3.37) |

| PTCy based | 1.64 (1.16 to 2.33) | 1.76 (1.08 to 2.88) |

| TCD | ||

| No | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 0.49 (0.38 to 0.62) | 0.55 (0.4 to 0.77) |

| Conditioning intensity | ||

| Myeloablative | Reference | Reference |

| Nonablative | 1.2 (0.87 to 1.65) | 1.11 (0.63 to 1.94) |

| Reduced intensity | 2.1 (1.7 to 2.61) | 2.41 (1.77 to 3.29) |

| Intensity and TBI group | ||

| Myeloablative, high-dose TBI | Reference | Reference |

| Myeloablative, chemotherapy | 1.74 (1.11 to 2.72) | 1.04 (0.57 to 1.9) |

| Nonablative | 1.89 (1.14 to 3.13) | 1.15 (0.54 to 2.41) |

| Reduced intensity, chemotherapy | 3.56 (2.27 to 5.6) | 2.56 (1.42 to 4.62) |

| Reduced intensity, low-dose TBI | 2.26 (1.3 to 3.93) | 2.16 (1.02 to 4.57) |

| Exposure-/complication-specific variables | ||

| Nephrotoxic medication use | 3.65 (2.67 to 4.99) | 3.46 (2.16 to 5.53) |

| GVHD grade I–II | 0.84 (0.6 to 1.18) | 0.81 (0.47 to 1.37) |

| GVHD grade III–IV | 0.94 (0.57 to 1.55) | 0.83 (0.36 to 1.92) |

| Bacteremia | 1.33 (0.99 to 1.78) | 1.51 (0.98 to 2.32) |

n=613 (three patients that were excluded were twins who received no GVHD prophylaxis). Age (by 5-year increments), sex, race, body mass index, HLA, cytomegalovirus status, bacteremia, and baseline CKD showed no statistically significant higher risk for any AKI or severe AKI. HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; HCT-CI, hematopoietic cell transplant–specific comorbidity index; TBI, total-body irradiation; GVHD, graft versus host disease; TCD, T cell–depleted transplant; PTCy, post-transplantation cyclophosphamide.

Baseline albumin was statistically significant for severe AKI only.

Non-Hispanic ethnicity had a lower risk for severe AKI (HR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.28 to 0.77), as was higher baseline serum albumin, per 1 g/dl higher (HR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.4 to 0.87). Higher risk of severe AKI was associated with reduced-intensity conditioning (HR, 2.41; 95% CI, 1.77 to 3.29), and lower risk with T cell–depleted compared with all other transplants (HR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.4 to 0.77). Unmodified transplants with the use of tacrolimus (HR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.26 to 2.58), tacrolimus/sirolimus (HR, 1.95; 95% CI, 1.13 to 3.37), and cyclophosphamide (HR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.08 to 2.88) were each associated with higher risk of severe AKI compared with T cell–depleted transplants. There was no association between any or severe AKI with BMI, HLA match, or CMV serostatus.

In multivariable analysis, choice of GVHD prophylaxis remained associated with higher any-AKI and severe AKI risk (Table 3). Compared with T cell–depleted transplants, AKI risk was higher in unmodified transplants with tacrolimus (HR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.39 to 2.56), combination tacrolimus-sirolimus (HR, 2.78; 95% CI, 1.62 to 4.78), and cyclophosphamide (HR, 1.72; 95% CI, 1.17 to 2.52). AKI risk remained higher in the chemotherapy-based, reduced-intensity conditioning group compared with myeloablative group (HR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.3 to 3.52).

Table 3.

Risk factors for AKI, multivariable analysis

| Variables | HR (95%CI) | |

| Any AKI | Severe (Stage 2–3) AKI | |

| Patient-specific variables | ||

| Ethnicity | n/a | |

| Hispanic/Latino | Reference | |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 0.44 (0.26 to 0.75) | |

| Unknown | 0.49 (0.27 to 0.87) | |

| Baseline albumin (g/dl) | n/a | 0.56 (0.36 to 0.87) |

| Transplant-specific variables | ||

| GVHD prophylaxis group | ||

| TCD | Reference | Reference |

| Tacrolimus based | 1.89 (1.39 to 2.56) | 1.25 (0.77 to 2.05) |

| Tacrolimus/sirolimus based | 2.78 (1.62 to 4.78) | 2.89 (1.33 to 6.29) |

| PTCy based | 1.72 (1.17 to 2.52) | 1.63 (0.93 to 2.88) |

| Intensity and TBI group | ||

| Myeloablative, high-dose TBI | Reference | Reference |

| Myeloablative, chemotherapy | 1.52 (0.97 to 2.36) | 1.04 (0.57 to 1.89) |

| Nonablative | 1.16 (0.61 to 2.22) | 0.56 (0.22 to 1.42) |

| Reduced intensity, chemotherapy | 2.14 (1.3 to 3.52) | 2.22 (1.1 to 4.45) |

| Reduced intensity, low-dose TBI | 1.46 (0.79 to 2.71) | 1.94 (0.82 to 4.58) |

| Exposure/complication-specific variables | ||

| Nephrotoxic medication use | 3.12 (2.24 to 4.34) | 2.3 (1.37 to 3.84) |

Multivariable analysis of risk factors of developing any AKI and severe (stage 2–3) AKI; n=613 (three patients who were excluded were twins who received no GVHD prophylaxis). A combined grouping variable for conditioning treatment and preparative regimen intensity was used rather than individual variables to examine detailed strata differences in the multivariable analysis. Other statistically important variables (unadjusted P<0.10) were also included in the multivariable model (results not shown). Age (by 5-year increments), sex, race, body mass index, hematopoietic cell transplant–specific comorbidity index group, HLA, cytomegalovirus status, bacteremia, and baseline CKD showed no statistically significant higher risk for any AKI or severe AKI. HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; n/a, not applicable (not included in analysis); GVHD, graft versus host disease; TCD, T cell–depleted transplant; PTCy, post-transplantation cyclophosphamide; TBI, total-body irradiation.

Post-Transplant Risk Factors for AKI

Nephrotoxic medication exposure occurred in 46 of 403 (11%) patients before development of any AKI. Amphotericin B preceded AKI in 18 of 403 (5%) patients, cidofovir in five of 403 (1%), foscarnet in 27 of 403 (7%), gentamicin in two of 403 (1%), and in six of 403 (22%) patients who received a combination thereof (Supplemental Table 5). AKI risk was higher with nephrotoxic medication exposure (HR, 3.65; 95% CI, 2.67 to 4.99; P<0.001), as was severe AKI risk (HR, 3.46; 95% CI, 2.16 to 5.53; P<0.001); see Table 2. Acute GVHD occurred in 290 (47%) patients; gastrointestinal and skin involvement were most common, occurring in 246 (40%) and 172 (28%) of patients, respectively. Mild acute GVHD (grades I–II) occurred in 230 (37%) patients and severe acute GVHD (grades III–IV) in 60 (10%) patients. Neither mild (HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.6 to 1.18) nor severe acute GVHD (HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.57 to 1.55) was associated with AKI. Bacteremia was not associated with severe AKI (HR, 1.51; 95% CI, 0.98 to 2.23).

Subgroup Analysis of AKI Population

Tacrolimus and vancomycin data are shown in Supplemental Table 6. In the AKI cohort, GVHD prophylaxis–related tacrolimus exposure preceded AKI in 228 of 403 (57%) patients. Mean tacrolimus levels preceding AKI was 10.16 ng/ml (SD, 2.0; IQR, 9.2–11.2). Vancomycin exposure occurred in 163 of 404 (40%) patients before AKI onset, with higher incidence of severe AKI in those who received vancomycin (Supplemental Table 6). Mean vancomycin levels preceding AKI onset was 14 μg/ml (SD, 8.3; IQR, 9–21). Neither tacrolimus nor vancomycin levels were associated with AKI severity.

Descriptive Analysis of Stage 3 AKI

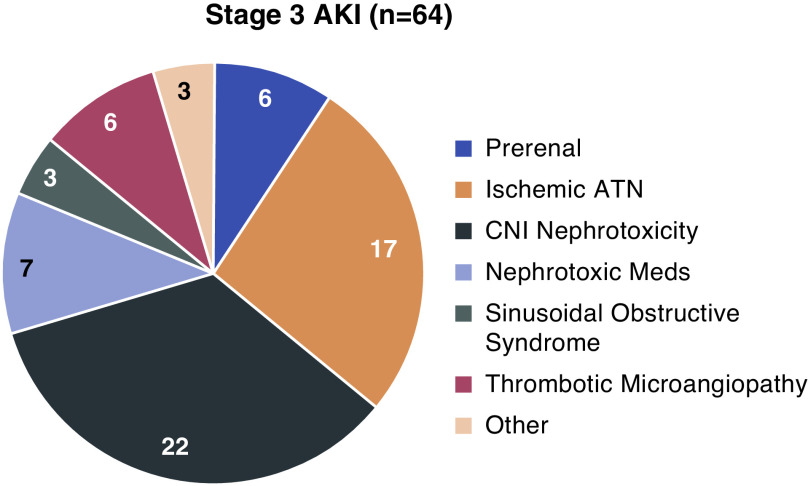

Among 64 patients who developed stage 3 AKI, 21 (33%) required KRT. Median (IQR) duration on KRT was 7 (3.5–13) days. Kidney function recovered, leading to liberation from KRT, in nine of 21 (43%) patients. Mortality of patients requiring KRT during the hospitalization was 76% (16 of 21). Etiologies for stage 3 AKI included CNI nephrotoxicity (22 of 64; 34%), ischemic ATN (17 of 64; 27%), nephrotoxic medications excluding CNIs (seven of 64; 11%), TMA (six of 64; 9%), prerenal AKI (six of 64; 9%), sinusoidal obstructive syndrome (three of 64; 5%), tumor lysis syndrome (two of 64; 3%), and suspected BK virus nephropathy (one of 64; 2%) (Figure 3). Among the 21 patients requiring KRT, etiologies of AKI included ischemic ATN (seven of 21), sinusoidal obstructive syndrome (three of 21), TMA (three of 21), CNI nephrotoxicity (five of 21), tumor lysis syndrome (two of 21), and cidofovir (one of 21).

Figure 3.

CNI toxicity and ischemic ATN are common etiologies of Stage 3 AKI, n=64. CNI nephrotoxicity was the most common etiology of stage 3 AKI, followed by ischemic acute tubular nephropathy (ATN) and tubular injury due to other nephrotoxic medications. Other etiologies (n=3) include tumor lysis syndrome (n=2) and suspected BK virus nephropathy (n=1).

All five patients requiring KRT who survived through discharge achieved dialysis independence. In this cohort, AKI was due to CNI toxicity in two patients, TMA and ischemic ATN in one patient, TMA and CNI toxicity in one patient, and tumor lysis syndrome in one patient. Median (IQR) onset of maximum AKI was 12 (2–8) days, time on KRT was 7 (6–19) days, and creatinine at discharge was 1.1 (0.8–1.1) mg/dl.

CKD Analysis

At 6 months post-transplant, 90 of 443 (20%) patients met the criteria for incident CKD (CKD stage 4, one of 90; CKD stage 3b, 24 of 90; CKD stage 3a, 65 of 90). Similarly, at 12 months post-transplant, 73 of 345 (21%) patients met the criteria for incident CKD (CKD stage 4, three of 73; CKD stage 3b, 20 of 73; CKD stage 3a, 50 of 73). Both AKI onset and severity were risk factors for CKD at both 6 and 12 months post-transplant (Table 4). Patients with baseline CKD (n=35), progression of disease or relapse (n=136 at 6 months, n=233 at 12 months), and missing data (n=6 at 6 months, n=3 at 12 months) were excluded. eGFR decline was seen in all subgroups at 6 and 12 months, and was higher for each consecutive AKI subgroup. For patients without AKI who did not develop CKD, median (IQR) eGFR decline was 8 (0–18) cc/min at 6 months and 14 (0–23) cc/min at 12 months; whereas for those with stage 3 AKI who developed CKD, eGFR decline was 52 (46–61) cc/min at 6 months and 56 (47–59) cc/min at 12 months (Table 4).

Table 4.

Six-month and 12-month CKD incidence in relation to maximum-stage AKI

| Progression Free Population at Landmark Follow-Ups | AKI Max Stage | Significance | |||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Progression free patients at 6 months (n=443), n | 168 | 163 | 84 | 28 | |

| CKD at 6 months, n (%) | 10 (6) | 43 (26) | 30 (36) | 7 (25) | <0.001 |

| eGFR decline (incident CKD), median (IQR) | 22 (15–29) | 26 (20–38) | 43 (34–53) | 52 (46–61) | |

| eGFR decline (no incident CKD), median (IQR) | 8 (0–18) | 18 (0–32) | 32 (13–58) | 42 (13–67) | |

| Progression free patients at 12 months (n=345), n | 128 | 123 | 71 | 23 | |

| CKD at 12 months, n (%) | 7 (6) | 31 (25) | 30 (42) | 5 (22) | <0.001 |

| eGFR decline (incident CKD), median (IQR) | 31 (21–42) | 26 (18–36) | 45 (31–66) | 56 (47–59) | |

| eGFR decline (no incident CKD), median (IQR) | 14 (0–23) | 15 (0–32) | 40 (16–57) | 47 (22–71) | |

Chi-squared test of independence performed for statistical significance. Six patients were excluded at 6 months and three patients were excluded at 12 months due to missing data. IQR, interquartile range.

Discussion

AKI in the current era of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation remains a major concern. As availability increases, kidney injury will continue to affect patient outcomes. Our study showed a high incidence of AKI in 64% of patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, with stage 3 AKI occurring in 10% of patients, and 3% requiring KRT. Similar to past studies (Supplemental Table 1), we found that risk of nonrelapse mortality was higher with AKI (HR, 2.77; 95% CI, 1.8 to 4.27; P<0.001). Although prior studies report close to 100% mortality with KRT (13), in our study, 43% recovered off KRT and 24% survived to hospital discharge. Of the five patients who survived to discharge, all remained dialysis independent. This is an important finding, indicating that KRT may not necessarily confer a dismal prognosis as previously reported.

Reduced-intensity conditioning, CNI-based GVHD prophylaxis, and nephrotoxic medications were significantly associated with higher AKI, whereas T cell–depleted transplants carried the lowest risk of AKI. Most patients who received myeloablative conditioning underwent T cell–depleted transplants where CNIs were not used, whereas reduced-intensity conditioning and nonmyeloablative patients received unmodified allografts requiring CNIs. Thus, use of unmodified transplant with reduced-intensity conditioning dictated the CNI-based GVHD prophylaxis strategy. The effect of reduced-intensity conditioning on AKI is also confounded by comorbidities because these patients had higher HCT-CI scores. Notably, 51% of patients had high HCT-CI risk in the entire cohort.

CNIs cause AKI by arteriolar vasoconstriction, reducing kidney perfusion, tubular toxicity, and endothelial injury with TMA (27,28). CNI nephrotoxicity after hematopoietic transplantation is reported in up to 31% of patients (29). The use of tacrolimus independently or with sirolimus imparted higher AKI risk in this study. Interestingly, there was no correlation between tacrolimus level and AKI severity. This emphasizes the existing knowledge gap regarding the ideal therapeutic target to balance risks of GVHD and AKI. Kidney vasoconstriction may not be level dependent and may be ameliorated by other factors, such as vasodilator use (30).

GVHD was not associated with AKI, similar to other studies (4,5), suggesting it may not play a significant role in kidney injury early post-transplant. Animal studies have shown interstitial mononuclear inflammation during acute GVHD post-transplant, supporting immunologic kidney involvement, which may not clinically manifest early on, but may affect kidney function later in the course (31). This has not been studied in humans due to the difficulty in obtaining kidney biopsies during the early post-transplant period. Furthermore, it is difficult to separate the effect of CNIs and GVHD on AKI because both variables are highly concordant. Podocytopathies are also reported manifestations of chronic GVHD later on (32), during taper of immunosuppression (33). Prospective studies with kidney biopsies in AKI post-transplant are needed.

A higher baseline serum albumin was associated with lower risk of severe AKI (HR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.4 to 0.87), in concordance with prior studies (17). Albumin may reduce kidney perfusion by affecting oncotic pressure and intravascular volume (34), and is a marker of baseline nutritional status; incorporation into the HCT-CI risk score should be considered. Moreover, the HCT-CI score uses serum creatinine to assess kidney comorbidity, which may inaccurately portray kidney function in certain patients. For example, in our study, non-Hispanic patients had lower risk of severe AKI (HR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.28 to 0.77; P=0.006). Hispanic individuals disproportionately suffer from CKD (worse eGFR, higher proteinuria) compared with non-Hispanic individuals (35), and race is inadequately represented in the CKD-EPI equation (36 –38). The CKD-EPI equation may also inaccurately portray GFR in patients who have low muscle mass postchemotherapy; therefore, alternative measures such as cystatin C (39) or iohexol (40,41) need further investigation for GFR estimation.

Antimicrobials were an important risk for post-transplant AKI. Foscarnet has been associated with both AKI and eGFR decline at 6 and 12 months (42). Vancomycin, postulated to cause oxidative stress and kidney tubular injury (43), also carried higher risk of AKI and, hence, should be used with caution. Substitutions for less nephrotoxic medications should be made where possible. Regarding viral infections, we did not find any association with CMV serostatus, and BK virus nephropathy was suspected in only one patient in our stage 3 AKI cohort. This is consistent with prior studies suggesting BK nephropathy is more prominent after the first 100 days post-transplant (44).

Strategies to mitigate early kidney injury are important to prevent the sequelae of CKD after allogeneic transplant, with reported incidences ranging from 20% to 66% (45 –48). AKI is a significant risk factor for CKD, increasing risk two-fold, and a lower risk of CKD has been described in T cell–depleted transplants compared with unmodified transplants (46). Our study found the incidence of CKD to be 20% at 6 months, and 21% at 12 months. Identification of biomarkers for early detection of AKI and intervention may help prevent CKD.

Limitations of this study include its retrospective nature and lack of a control group, which precluded us from determining whether CNI exposure conferred higher risk for AKI. We were unable to separate the effect of methotrexate in patients receiving tacrolimus for GVHD prophylaxis. Lack of kidney biopsies due to thrombocytopenia prevented histologic correlation. We were unable to include baseline urine studies for proteinuria. Our list of nephrotoxic medications did not include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; iodinated contrast; or other antibiotics, such as piperacillin-tazobactam, which are associated with higher AKI when used in combination (49). Heterogeneity of conditioning chemotherapy regimens limited their inclusion in analysis. We used landmark time points to define incident CKD (at 6-month and 12-month follow-ups), rather than sustained eGFR decline. This was chosen to provide a uniform time point for all patients, because visits were variable after the 100-day mark.

Despite these limitations, this study provides current information on factors affecting kidney injury in this complex patient population. Strengths of our study include a large sample size, recent cohort, and long-term follow-up. Prospective studies are needed to assess modification of pre- and post-transplant risk factors. Improved techniques to accurately measure baseline kidney function will help identify patients at higher risk for AKI.

Disclosures

E.A. Jaimes reports serving as a scientific advisor for, or member of, American Journal of Physiology, Frontiers in Pharmacology-Renal, and Goldilocks; being a shareholder and chief medical officer of Goldilocks Therapeutics, Inc; and receiving honoraria from Natera and UpToDate. M. Scordo reports having consultancy agreements with Angiocrine Bioscience, Inc. and Omeros Corporation; receiving research funding from Angiocrine Bioscience, Inc. (for a prospective clinical trial) and Omeros (for a retrospective clinical trial); receiving honoraria from i3Health for a continuing medical education–sponsored speaking event; serving ad hoc on an advisory board with Kite, a Gilead Company; and having a previous ad hoc cons-ultancy agreement with McKinsey & Company. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This research was supported by National Institute of Health Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA008748.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The abstract for this manuscript was presented at Transplantation and Cellular Therapy Meetings in 2020 (#14890) and American Society of Nephrology in 2019 (#3231158).

M.H. Abramson, E.A. Jaimes, and I.J. Sathick conceived the project; J.D. Ruiz and M.A. Maloy assisted with institutional review board approval and data collection; J. Zheng performed statistical analysis; and M.H. Abramson and V. Gutgarts wrote the manuscript, with supervision from E.A. Jaimes, M. Scordo, and I.J. Sathick.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

Supplemental Material

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi: 10.2215/CJN.19801220/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1. Prior studies of acute kidney injury in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Supplemental Table 2. Timing of max AKI, AKI, stratified by max AKI stage.

Supplemental Table 3. NRM cumulative rate (95% CI) at 6 months and 1 year by AKI stage in d100 landmark cohort (n=536).

Supplemental Table 4. Transplant type and GVHD prophylaxis regimen stratified by max AKI stage.

Supplemental Table 5. AKI subgroup analyses: Medication exposures in AKI subgroup.

Supplemental Table 6. AKI subgroup analyses: Comparison of vancomycin and tacrolimus use in patients with AKI, based on severity.

References

- 1.Health Resources and Services Administration: Transplant activity report, 2020. Available at: https://bloodstemcell.hrsa.gov/data/donation-and-transplantation-statistics/transplant-activity-report. Accessed December 20, 2020

- 2.McDonald GB, Sandmaier BM, Mielcarek M, Sorror M, Pergam SA, Cheng GS, Hingorani S, Boeckh M, Flowers MD, Lee SJ, Appelbaum FR, Storb R, Martin PJ, Deeg HJ, Schoch G, Gooley TA: Survival, nonrelapse mortality, and relapse-related mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: Comparing 2003 –2007 versus 2013 –2017 cohorts. Ann Intern Med 172: 229–239, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mima A, Tansho K, Nagahara D, Tsubaki K: Incidence of acute kidney disease after receiving hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A single-center retrospective study. PeerJ 7: e6467, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sehgal B, George P, John MJ, Samuel C: Acute kidney injury and mortality in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A single-center experience. Indian J Nephrol 27: 13–19, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hingorani SR, Guthrie K, Batchelder A, Schoch G, Aboulhosn N, Manchion J, McDonald GB: Acute renal failure after myeloablative hematopoietic cell transplant: Incidence and risk factors. Kidney Int 67: 272–277, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saddadi F, Najafi I, Hakemi MS, Falaknazi K, Attari F, Bahar B: Frequency, risk factors, and outcome of acute kidney injury following bone marrow transplantation at Dr Shariati Hospital in Tehran. Iran J Kidney Dis 4: 20–26, 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellomo R, Ronco C, Kellum JA, Mehta RL, Palevsky P; Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative workgroup: Acute renal failure - Definition, outcome measures, animal models, fluid therapy and information technology needs: The Second International Consensus Conference of the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) Group. Crit Care 8: R204–R212, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, Molitoris BA, Ronco C, Warnock DG, Levin A; Acute Kidney Injury Network: Acute Kidney Injury Network: Report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 11: R31, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D; Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group: A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: A new prediction equation. Ann Intern Med 130: 461–470, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO): 2012 KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury, 2012. Available at: https://kdigo.org/guidelines/acute-kidney-injury/. Accessed December 20, 2020

- 11.Martinez-Schlurmann N, Rampa S, Romesh N, Allareddy V, Rotta A, Allareddy V: 962: Impact of hemodialysis following arf on mortality in adult stem cell transplant recipients. Crit Care Med 43: 242, 2015. 25514715 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hingorani S: Renal complications of hematopoietic-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med 374: 2256–2267, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hahn T, Rondeau C, Shaukat A, Jupudy V, Miller A, Alam AR, Baer MR, Bambach B, Bernstein Z, Chanan-Khan AA, Czuczman MS, Slack J, Wetzler M, Mookerjee BK, Silva J, McCarthy PL Jr: Acute renal failure requiring dialysis after allogeneic blood and marrow transplantation identifies very poor prognosis patients. Bone Marrow Transplant 32: 405–410, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu H, Li YF, Liu BC, Ding JH, Chen BA, Xu WL, Qian J: A multicenter, retrospective study of acute kidney injury in adult patients with nonmyeloablative hematopoietic SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant 45: 153–158, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu ZP, Ding JH, Chen BA, Liu BC, Liu H, Li YF, Ding BH, Qian J: Risk factors for acute kidney injury in patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Chin J Cancer 29: 946–951, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piñana JL, Valcárcel D, Martino R, Barba P, Moreno E, Sureda A, Vega M, Delgado J, Briones J, Brunet S, Sierra J: Study of kidney function impairment after reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. A single-center experience. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 15: 21–29, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gutgarts V, Sathick IJ, Zheng J, Politikos I, Devlin SM, Maloy MA, Giralt SA, Scordo M, Bhatt V, Glezerman I, Muthukumar T, Jaimes EA, Barker JN: Incidence and Risk factors for acute and chronic kidney injury after adult cord blood transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 26: 758–763, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration): A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sorror ML, Maris MB, Storb R, Baron F, Sandmaier BM, Maloney DG, Storer B: Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT)-specific comorbidity index: A new tool for risk assessment before allogeneic HCT. Blood 106: 2912–2919, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sorror ML: How I assess comorbidities before hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood 121: 2854–2863, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kolb H-J: Graft-versus-leukemia effects of transplantation and donor lymphocytes. Blood 112: 4371–4383, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bacigalupo A, Ballen K, Rizzo D, Giralt S, Lazarus H, Ho V, Apperley J, Slavin S, Pasquini M, Sandmaier BM, Barrett J, Blaise D, Lowski R, Horowitz M: Defining the intensity of conditioning regimens: Working definitions. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 15: 1628–1633, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cornell RF, Hari P, Drobyski WR: Engraftment syndrome after autologous stem cell transplantation: An update unifying the definition and management approach. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 21: 2061–2068, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruutu T, Barosi G, Benjamin RJ, Clark RE, George JN, Gratwohl A, Holler E, Iacobelli M, Kentouche K, Lämmle B, Moake JL, Richardson P, Socié G, Zeigler Z, Niederwieser D, Barbui T; European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation; European LeukemiaNet: Diagnostic criteria for hematopoietic stem cell transplant-associated microangiopathy: Results of a consensus process by an International Working Group. Haematologica 92: 95–100, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanaka Y, Kurosawa S, Tajima K, Tanaka T, Ito R, Inoue Y, Okinaka K, Inamoto Y, Fuji S, Kim SW, Tanosaki R, Yamashita T, Fukuda T: Analysis of non-relapse mortality and causes of death over 15 years following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 51: 553–559, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Inker LA, Astor BC, Fox CH, Isakova T, Lash JP, Peralta CA, Kurella Tamura M, Feldman HI: KDOQI US commentary on the 2012 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 63: 713–735, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Radermacher J, Meiners M, Bramlage C, Kliem V, Behrend M, Schlitt HJ, Pichlmayr R, Koch KM, Brunkhorst R: Pronounced renal vasoconstriction and systemic hypertension in renal transplant patients treated with cyclosporin A versus FK 506. Transpl Int 11: 3–10, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oyen O, Strøm EH, Midtvedt K, Bentdal O, Hartmann A, Bergan S, Pfeffer P, Brekke IB: Calcineurin inhibitor-free immunosuppression in renal allograft recipients with thrombotic microangiopathy/hemolytic uremic syndrome. Am J Transplant 6: 412–418, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karimzadeh I, Jafari M, Davani-Davari D, Ramzi M: The pattern of cyclosporine nephrotoxicity and urinary kidney injury molecule 1 in allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients. Exp Clin Transplant 19: 553–562, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jensen RR, Healy RM, Ford CD, Child B, Majers J, Draper B, Hasan Y, Hoda D: Amlodipine and calcineurin inhibitor-induced nephrotoxicity following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Clin Transplant 33: e13633, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Higo S, Shimizu A, Masuda Y, Nagasaka S, Kajimoto Y, Kanzaki G, Fukui M, Nagahama K, Mii A, Kaneko T, Tsuruoka S: Acute graft-versus-host disease of the kidney in allogeneic rat bone marrow transplantation. PLoS One 9: e115399, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakashima H: Membranous nephropathy is developed under Th2 environment in chronic graft-versus-host disease. Med Hypotheses 69: 787–791, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brukamp K, Doyle AM, Bloom RD, Bunin N, Tomaszewski JE, Cizman B: Nephrotic syndrome after hematopoietic cell transplantation: Do glomerular lesions represent renal graft-versus-host disease? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 685–694, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siddall E, Khatri M, Radhakrishnan J: Capillary leak syndrome: Etiologies, pathophysiology, and management. Kidney Int 92: 37–46, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fischer MJ, Go AS, Lora CM, Ackerson L, Cohan J, Kusek JW, Mercado A, Ojo A, Ricardo AC, Rosen LK, Tao K, Xie D, Feldman HI, Lash JP; CRIC and H-CRIC Study Groups: CKD in Hispanics: Baseline characteristics from the CRIC (Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort) and Hispanic-CRIC Studies. Am J Kidney Dis 58: 214–227, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stevens LA, Claybon MA, Schmid CH, Chen J, Horio M, Imai E, Nelson RG, Van Deventer M, Wang HY, Zuo L, Zhang YL, Levey AS: Evaluation of the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation for estimating the glomerular filtration rate in multiple ethnicities. Kidney Int 79: 555–562, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eneanya ND, Yang W, Reese PP: Reconsidering the consequences of using race to estimate kidney function. JAMA 322: 113–114, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Powe NR: Black kidney function matters: Use or misuse of race? JAMA 324: 737–738, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stevens LA, Coresh J, Schmid CH, Feldman HI, Froissart M, Kusek J, Rossert J, Van Lente F, Bruce RD 3rd, Zhang YL, Greene T, Levey AS: Estimating GFR using serum cystatin C alone and in combination with serum creatinine: A pooled analysis of 3,418 individuals with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 51: 395–406, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hingorani S, Pao E, Schoch G, Gooley T, Schwartz GJ: Estimating GFR in adult patients with hematopoietic cell transplant: Comparison of estimating equations with an iohexol reference standard. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 601–610, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eriksen BO, Schaeffner E, Melsom T, Ebert N, van der Giet M, Gudnason V, Indridasson OS, Karger AB, Levey AS, Schuchardt M, Sørensen LK, Palsson R: Comparability of plasma iohexol clearance across population-based cohorts. Am J Kidney Dis 76: 54–62, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Foster GG, Grant MJ, Thomas SM, Cameron B, Raiff D, Corbet K, Loitsch G, Ferreri C, Horwitz M: Treatment with foscarnet after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant (Allo-HCT) is associated with long-term loss of renal function. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 26: 1597–1606, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luque Y, Louis K, Jouanneau C, Placier S, Esteve E, Bazin D, Rondeau E, Letavernier E, Wolfromm A, Gosset C, Boueilh A, Burbach M, Frère P, Verpont MC, Vandermeersch S, Langui D, Daudon M, Frochot V, Mesnard L: Vancomycin-associated cast nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 1723–1728, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abudayyeh A, Hamdi A, Lin H, Abdelrahim M, Rondon G, Andersson BS, Afrough A, Martinez CS, Tarrand JJ, Kontoyiannis DP, Marin D, Gaber AO, Salahudeen A, Oran B, Chemaly RF, Olson A, Jones R, Popat U, Champlin RE, Shpall EJ, Winkelmayer WC, Rezvani K: Symptomatic BK virus infection is associated with kidney function decline and poor overall survival in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell recipients. Am J Transplant 16: 1492–1502, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ando M, Ohashi K, Akiyama H, Sakamaki H, Morito T, Tsuchiya K, Nitta K: Chronic kidney disease in long-term survivors of myeloablative allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation: Prevalence and risk factors. Nephrol Dial Transplant 25: 278–282, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Glezerman IG, Devlin S, Maloy M, Bui M, Jaimes EA, Giralt SA, Jakubowski AA: Long term renal survival in patients undergoing T-cell depleted versus conventional hematopoietic stem cell transplants. Bone Marrow Transplant 52: 733–738, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hingorani S, Guthrie KA, Schoch G, Weiss NS, McDonald GB: Chronic kidney disease in long-term survivors of hematopoietic cell transplant. Bone Marrow Transplant 39: 223–229, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weiss AS, Sandmaier BM, Storer B, Storb R, McSweeney PA, Parikh CR: Chronic kidney disease following non-myeloablative hematopoietic cell transplantation. Am J Transplant 6: 89–94, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clemmons AB, Bech CF, Pantin J, Ahmad I: Acute kidney injury in hematopoietic cell transplantation patients receiving vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam versus vancomycin and cefepime. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 24: 820–826, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.