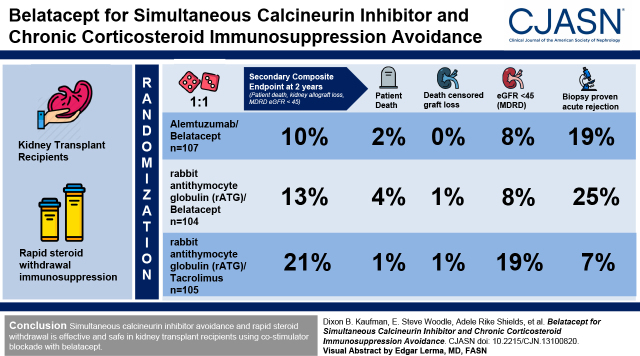

Visual Abstract

Keywords: kidney transplantation, immunosuppression, transplant outcomes

Abstract

Background and objectives

Immunosuppressive therapy in kidney transplantation is associated with numerous toxicities. CD28-mediated T-cell costimulation blockade using belatacept may reduce long-term nephrotoxicity, compared with calcineurin inhibitor–based immunosuppression. The efficacy and safety of simultaneous calcineurin inhibitor avoidance and rapid steroid withdrawal were tested in a randomized, prospective, multicenter study.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

This study reports the 2-year results of a randomized clinical trial of 316 recipients of a new kidney transplant. All kidney transplants were performed using rapid steroid withdrawal immunosuppression. Recipients were randomized in a 1:1:1 ratio to receive belatacept with alemtuzumab induction, belatacept with rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin (rATG) induction, or tacrolimus with rATG induction. The composite end point consisted of death, kidney allograft loss, or an eGFR of <45 ml/min per 1.73 m2 at 2 years.

Results

The composite end point was observed for 11 of 107 (10%) participants assigned to belatacept/alemtuzumab, 13 of 104 (13%) participants assigned to belatacept/rATG, and 21 of 105 (21%) participants assigned to tacrolimus/rATG (for belatacept/alemtuzumab versus tacrolimus/rATG, P=0.99; for belatacept/rATG versus tacrolimus/rATG, P=0.66). Patient and graft survival rates were similar between all groups. An eGFR of <45 ml/min per 1.73 m2 was observed for nine of 107 (8%) participants assigned to belatacept/alemtuzuab, eight of 104 (8%) participants assigned to belatacept/rATG, and 20 of 105 (19%) participants assigned to tacrolimus/rATG (P<0.05 for each belatacept group versus tacrolimus/rATG). Biopsy sample–proven acute rejection was observed for 20 of 107 (19%) participants assigned to belatacept/alemtuzuab, 26 of 104 (25%) participants assigned to belatacept/rATG, and seven of 105 (7%) participants assigned to tacrolimus/rATG (for belatacept/alemtuzumab versus tacrolimus/rATG, P=0.006; for belatacept/rATG versus tacrolimus/rATG, P<0.001). Gastrointestinal and neurologic adverse events were less frequent with belatacept versus calcineurin-based immunosuppression.

Conclusions

Overall 2-year outcomes were similar when comparing maintenance immunosuppression using belatacept versus tacrolimus, and each protocol involved rapid steroid withdrawal. The incidence of an eGFR of <45 ml/min per 1.73 m2 was significantly lower with belatacept compared with tacrolimus, but the incidence of biopsy sample–proven acute rejection significantly higher.

Clinical Trial registry name and registration number:

Belatacept Early Steroid Withdrawal Trial, NCT01729494

Introduction

Calcineurin inhibitor–based immunosuppression is the standard immunosuppressive therapy used in kidney transplantation. Calcineurin inhibitor–based therapy is associated with excellent patient and graft survival rates, with acute cellular rejection rates of <10% during the first year of transplantation. Calcineurin inhibitor therapy has greatly improved kidney transplant outcomes, but calcineurin inhibitors are also associated with numerous toxicities, either when used alone or when taken in combination with chronic corticosteroid use. These toxicities include nephrotoxity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and new onset diabetes after transplantation, all of which are associated with more frequent cardiovascular events (1), higher cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (2), neurotoxicity, and gastrointestinal toxicity.

Rapid steroid withdrawal regimens with calcineurin inhibitor–based immunosuppression, in combination with T-cell depletion induction immunotherapy, are commonly used regimens to minimize the toxicities associated with immunosuppression. In general, patient and graft survival rates are not compromised and corticosteroid-related morbidity is reduced, but these regimens are sometimes associated with an elevated risk of mild early acute cellular rejection (3 –6), and the calcineurin inhibitor–associated toxicities persist. In contrast, calcineurin inhibitor avoidance has been more challenging, even with corticosteroid use, due to greater rejection risks (7), but these regimens have been demonstrated to reduce nephrotoxity. The substitution of calcineurin inhibitors with a drug, belatacept, that blocks CD28-mediated T-cell costimulation in combination with corticosteroids has demonstrated acceptable patient and graft survival rates, reduced nephrotoxicity (8, 9), and lower de novo donor-specific antibody rates (10), but with higher rates of acute cellular rejection.

An interesting feasibility study, published in 2011, demonstrated that primary immunosuppression with costimulation blockade and simultaneous avoidance of both calcineurin inhibitors and corticosteroids in allograft recipients demonstrated improved kidney function with acceptable rates of acute rejection relative to a tacrolimus-based regimen (11). The Belatacept Early Steroid Withdrawal Trial (BEST) was a larger, longer-term, randomized, prospective, multicenter trial that demonstrated similar patient and graft survival rates, improved functional kidney allograft survival, and reduced neurotoxicity and electrolyte imbalances, but also demonstrated a statistically significant higher rate of acute cellular rejection at 1 year post-transplantation (12). The current report extends the follow-up to 2 years, with an emphasis on the extent to which a longer course of simultaneous avoidance of calcineurin inhibitors and corticosteroids may further improve kidney allograft function and diminish toxicities in the context of patient and graft survival and rejection rates.

Materials and Methods

This study reports the 2-year results of a randomized clinical trial of 316 recipients of a new kidney transplant. Methods have been published in detail previously (12), but the salient points are included below. Recipients who were seronegative for Epstein–Barr virus were excluded from participation. There were no changes in the methods after trial commencement.

Study Design

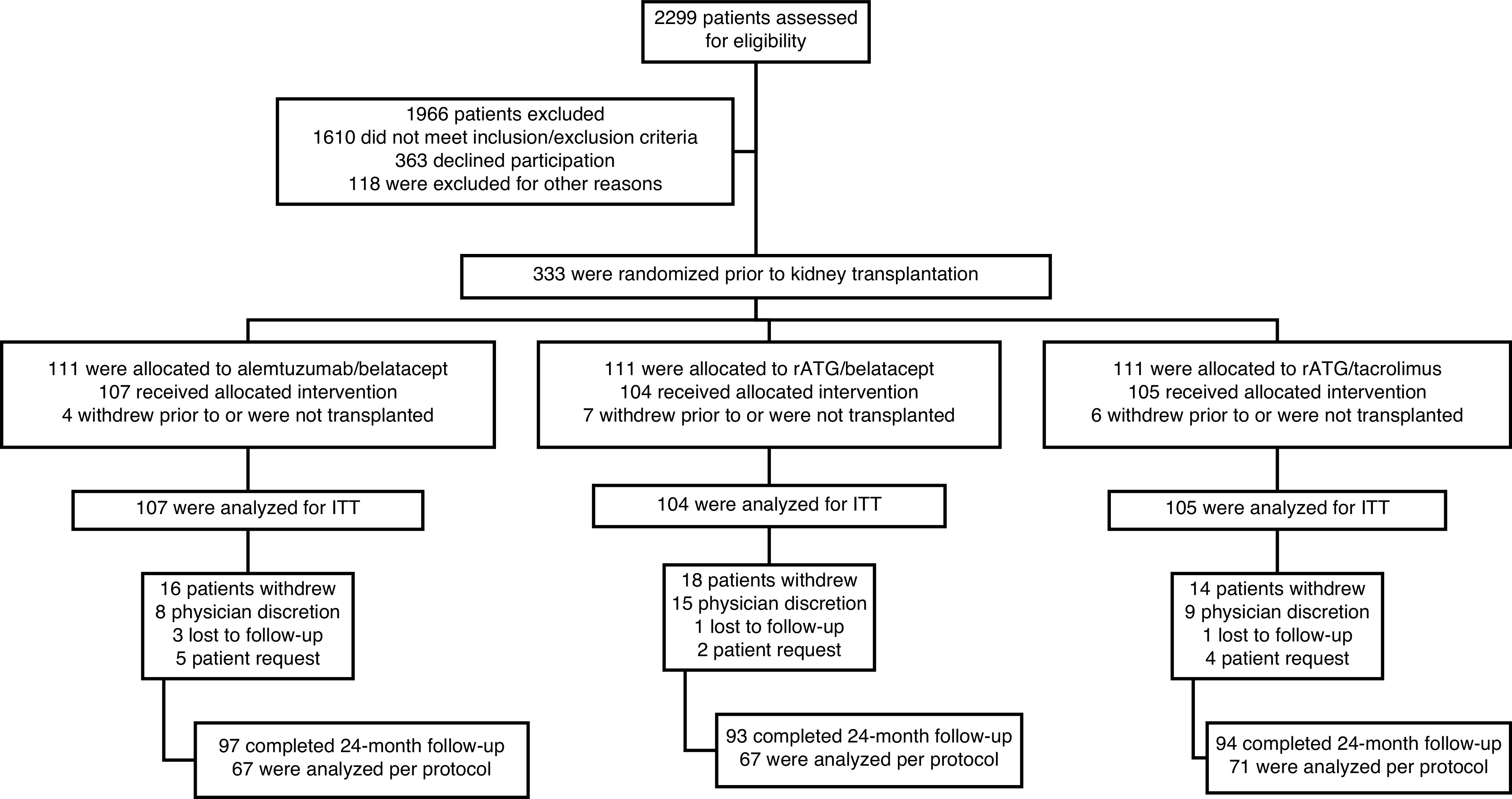

This was a prospective, randomized, open-label, multicenter safety and efficacy study. It was a three-arm trial, consisting of two study arms (belatacept/alemtuzumab and belatacept/anti-thymocyte globulin [rATG]) that both avoided calcineurin inhibitors and corticosteroids, and a control arm in which only corticosteroids were avoided (tacrolimus/rATG) (Figure 1). The intent was to conduct comparisons between belatacept/alemtuzumab versus tacrolimus/rATG, and belatacept/rATG versus tacrolimus/rATG. The clinical and research activities were consistent with the principles of the Declaration of Istanbul, as outlined in the Declaration of Istanbul on Organ Trafficking and Transplant Tourism. Participants were randomized 1:1:1 and enrolled at eight centers, with a target enrollment of 105 participants in each group. Randomization was stratified by center, living donor versus deceased donor, and Black versus non-Black recipient race. Randomization was web-based, and treatment assignment was concealed to study personnel before randomization.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram. ITT, intention to treat; rATG, rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin.

Study Conduct, Definitions, and Enrollment Criteria

Details are presented in detail in Table 1. Briefly, the study population included adults serologically positive for Epstein–Barr virus who received an ABO-compatible, brain-dead deceased (with cold ischemia time <24 hours) or living (not HLA identical) donor kidney-alone transplant. Included participants had a panel-reactive antibody level of <25%, a negative T- and B-cell crossmatch, and without donor-specific antibody levels that would be associated with a higher risk of rejection.

Study Objective and Hypotheses

The study objective was to determine the safety and efficacy of belatacept-based calcineurin inhibitor avoidance regimens with alemtuzumab or rATG induction in comparison with a tacrolimus-based regimen with rATG induction in kidney transplant recipients also treated with rapid steroid withdrawal. Two study hypotheses were tested: (1) belatacept-based immunosuppression with alemtuzumab induction will reduce allograft loss, death, or not impair kidney function at 2 years, compared with a tacrolimus-based immunosuppressive regimen with rATG induction, with all recipients also receiving mycophenolate and rapid steroid withdrawal; and (2) belatacept-based immunosuppression with rATG induction will reduce allograft loss, death, or not impair kidney function at 2 years, compared with a tacrolimus-based immunosuppressive regimen with rATG induction, with all recipients also receiving mycophenolate and rapid steroid withdrawal.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the composite end point of death, allograft loss, or an eGFR of <45 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease [MDRD] equation) measured at 2 years post-transplant. Secondary outcomes were (1) 2-year post-transplant outcomes that included the rates of each of the three individual components of the composite end point; (2) biopsy sample–confirmed acute rejection, stratified by type (acute cellular rejection, antibody-mediated rejection, or mixed acute rejection); (3) death-censored graft survival; and (4) proportion of participants developing anti-HLA antibodies against the donor (donor-specific antibodies) after transplantation. A complete list of tertiary end points is presented in Supplemental Table 1.

Materials

There were no changes in outcome considerations after the trial commenced.

All unexplained kidney dysfunction episodes were evaluated by biopsy and classified by the Banff 2007 (14) criteria. Protocol kidney transplant biopsies were not incorporated into the study design. Adverse events of interest included new onset diabetes after transplantation, exacerbation of preexisting diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, Framingham risk score, infection, malignancy, and adverse events associated with immunosuppression. Donor-specific antibodies were determined by single-antigen bead assay at pretransplant, and at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months post-transplant. The definitions of new onset diabetes after transplantation included any one of the following: (1) new requirement for insulin therapy for ≥30 days, (2) new use of oral hypoglycemic agents for ≥30 days, (3) any treatment (oral, insulin, or other) for ≥0 days, (4) two consecutive fasting blood sugar values of >126 mg/dl, or (5) hemoglobin A1C ≥6.5%.

Intervention

Induction Therapy.

Methylprednisolone (500 mg) and either alemtuzumab or rATG were administered intravenously and sequentially after induction of anesthesia. Alemtuzumab was administered as a single 30-mg dose over 2 hours. The first rATG dose was administered to provide at least 25% before allograft revascularization, and subsequent doses given over 4–6 hours. The total cumulative rATG dose was 4.0–6.0 mg/kg by post-transplant days 5–10.

Maintenance Immunosuppression.

Belatacept was administered intravenously, with the first belatacept dose (10 mg/kg) given >12 hours and <24 hours after revascularization. The second belatacept dose (10 mg/kg) was given between post-transplant days 4 and 6, and subsequent 10 mg/kg doses were given on post-transplant days 14, 28, 56, and 84. The belatacept dose was reduced to 5 mg/kg, given every 4 weeks, for 2 years. Tacrolimus was administered twice daily at a dose of 0.1 mg/kg per day within 48 hours post-transplant. The tacrolimus target trough level was 8–12 ng/ml for post-transplant days 1–30, and 5–10 ng/ml for post-transplant days 31–730. All groups received mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) or enteric-coated mycophenolate sodium and a 5-day corticosteroid taper. The first MMF/enteric-coated MMF dose was given preoperatively, and then twice daily postoperatively at 1000 mg (for MMF) or 720 mg (for enteric coated-MMF). Glucocorticoid therapy was given as intravenous methylprednisolone on post-transplant days 1–3, at a dose of 500 mg, 250 mg, and 125 mg, respectively. Oral prednisone was given at 80 mg on post-transplant day 4, 60 mg was given on post-transplant day 5, and then it was discontinued. All participants received center-specific bacterial, cytomegalovirus, fungal, and Pneumocystis prophylaxis.

No interim analysis was performed. The primary outcome at 1 year has been published previously (12). Stopping criteria were monitored by an independent data and safety monitoring board.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis plan required an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis at 2 years. All participants who were randomized and transplanted constituted the ITT population. The primary end point was the actual 1-year incidence of death, graft loss, or eGFR of <45 ml/min per 1.73 m2, which was analyzed using the stratified log-rank test to compare the Kaplan–Meier curves. The secondary end points were designed for analyses at 2 years post-transplant. For the year 2 data, the stratified log-rank test with the Hochberg adjustment for the two pairwise comparisons was used for the time-to-event analysis of the secondary composite end point of death, death-censored allograft loss, biopsy sample–proven acute rejection (BPAR), biopsy sample–proven acute cellular rejection, biopsy sample–proven antibody-mediated rejection, and biopsy sample–proven mixed acute rejection. Categoric end points were analyzed using the exact chi-squared test. Hochberg adjustment with an overall α-level of 5% was used for pairwise comparisons. Continuous variables were analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test with the Dwass–Steel–Critchlow–Fligner multiple comparison adjustment. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to evaluate subgroup variables, including (1) Black versus non-Black recipient race, (2) living donor versus deceased donor transplant, (3) male versus female recipient sex, (4) primary versus repeat recipient, (5) delayed graft function versus no delayed graft function, (6) HLA-DR mismatch of two, and (7) HLA-DQ mismatch of zero versus HLA-DQ mismatch of greater than zero.

Sample Size Determination.

The primary end point rate for the control group was assumed to be 50%. A sample size of 105 completed participants per group provided a power of 80% to detect an absolute difference of 21% between control and test groups at a two-sided α of 0.025.

Results

Study Participants

Enrollment occurred between September 2012 and December 2016. A total of 333 participants were randomized before kidney transplantation, and data from 316 participants were included in the ITT analyses: belatacept/alemtuzumab, n=107; belatacept/rATG, n=104; and tacrolimus/rATG, n=105. No differences were observed between treatment groups with respect to demographic data (including race), kidney failure etiology, donor source/characteristics, or immunologic profile (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of kidney transplant recipients in the Belatacept Early Steroid Withdrawal Trial

| Characteristics | Group A Alemtuzumab/Belatacept |

Group B rATG/Belatacept |

Group C rATG/Tacrolimus |

| Recipients, n | 107 | 104 | 105 |

| Age (yr) at transplant, median (IQR) | 54 (43–60) | 53 (45–60) | 51 (42–63) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 30 (28) | 38 (37) | 36 (34) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 82 (77) | 88 (85) | 80 (76) |

| Black | 12 (11) | 11 (11) | 19 (18) |

| Asian | 5 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 3 (3) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Other | 5 (5) | 4 (4) | 5 (5) |

| Ethnicity (Hispanic or Latino), n (%) | 8 (8) | 5 (5) | 8 (8) |

| Kidney failure etiology, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 22 (21) | 16 (15) | 16 (15) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 20 (19) | 21 (20) | 21 (20) |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 25 (23) | 24 (23) | 21 (20) |

| GN | 8 (8) | 9 (9) | 7 (7) |

| SLE | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (3) |

| FSGS | 7 (7) | 4 (4) | 5 (5) |

| IgA nephropathy | 9 (8) | 7 (7) | 7 (7) |

| Obstructive disorder/reflux | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 3 (3) |

| Unknown | 3 (3) | 3 (3) | 3 (3) |

| Other | 10 (9) | 20 (19) | 19 (18) |

| Donor type, n (%) | |||

| Living related donor | 25 (23) | 25 (24) | 33 (31) |

| Living unrelated donor | 55 (51) | 53 (51) | 47 (45) |

| Deceased donor | 27 (25) | 26 (25) | 25 (24) |

| Pre-emptive transplant, n (%) | 37 (35) | 27 (26) | 40 (39) |

| Repeat transplant, n (%) | 7 (7) | 2 (2) | 3 (3) |

| HLA-A mismatches, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 9 (8) | 7 (7) | 7 (7) |

| 1 | 52 (49) | 53 (51) | 55 (52) |

| 2 | 46 (43) | 44 (42) | 43 (41) |

| HLA-B mismatches, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 5 (5) | 3 (3) | 4 (4) |

| 1 | 42 (39) | 37 (36) | 50 (48) |

| 2 | 60 (56) | 64 (62) | 51 (49) |

| HLA-DR mismatches, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 7 (7) | 6 (6) | 14 (13) |

| 1 | 45 (42) | 56 (54) | 53 (51) |

| 2 | 55 (51) | 42 (40) | 38 (36) |

| HLA-DQ mismatches, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 15 (14) | 16 (15) | 17 (16) |

| 1 | 52 (49) | 48 (46) | 57 (54) |

| 2 | 40 (37) | 40 (39) | 31 (30) |

| Pretransplant cPRA (%) | |||

| N | 103 | 101 | 102 |

| Median (IQR) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) |

| Min, max | 0, 57 | 0, 79 | 0, 91 |

| Preexisting DSA, n (%) | 1 (1) | 4 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Deceased-donor cold ischemia time (h) | |||

| N | 21 | 22 | 20 |

| Median (IQR) | 12 (11–16) | 12 (10–17) | 13 (8–18) |

| CMV donor/recipient serology, n (%) | |||

| D+R− | 18 (17) | 21/103 (20) | 25 (24) |

| D+R+ | 37 (35) | 28/103 (27) | 33 (31) |

| D−R+ | 17 (16) | 19/103 (19) | 14 (13) |

| D−R− | 35 (33) | 35/103 (34) | 33 (31) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | |||

| Type 1 | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 6 (6) |

| Type 2 | 24 (22) | 31 (30) | 27 (26) |

| Pretransplant BMI (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 28 (24–32) | 28 (26–31) | 28 (25–32) |

| Framingham risk score, median (IQR) | 5 (1–7) | 5 (2–8) | 5 (1–8) |

| Donor data | |||

| Female donor sex, n (%) | 65 (61) | 63 (61) | 64 (61) |

| Donor age (yr), median (IQR) | 45 (32–53) | 42 (31–50) | 40 (31–48) |

| Donor race, n (%) | |||

| White | 100 (94) | 95 (91) | 95 (91) |

| Black | 3 (3) | 4 (4) | 4 (4) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Asian | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 5 (5) |

| History of hypertension, n (%) | |||

| Positive | 10 (9) | 10 (10) | 11 (11) |

| Negative | 89 (83) | 87 (84) | 85 (81) |

| N/A | 8 (8) | 7 (7) | 9 (9) |

| CVA as cause of death, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 5 (5) | 1 (1) | 3 (3) |

| No | 21 (20) | 27 (26) | 23 (22) |

| N/A | 81 (76) | 76 (73) | 79 (75) |

| Terminal creatinine >1.5 mg/dl2, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 1 (1) | 4 (4) | 3 (3) |

| No | 32 (30) | 27 (26) | 29 (28) |

| N/A | 74 (69) | 73 (70) | 73 (70) |

rATG, rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin; IQR, interquartile range; cPRA, calculated panel-reactive antibody; min, minimum; max, maximum; DSA, donor-specific antibodies; CMV, cytomegalovirus; BMI, body mass index; N/A, not available; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; D, donor; R, recipient.

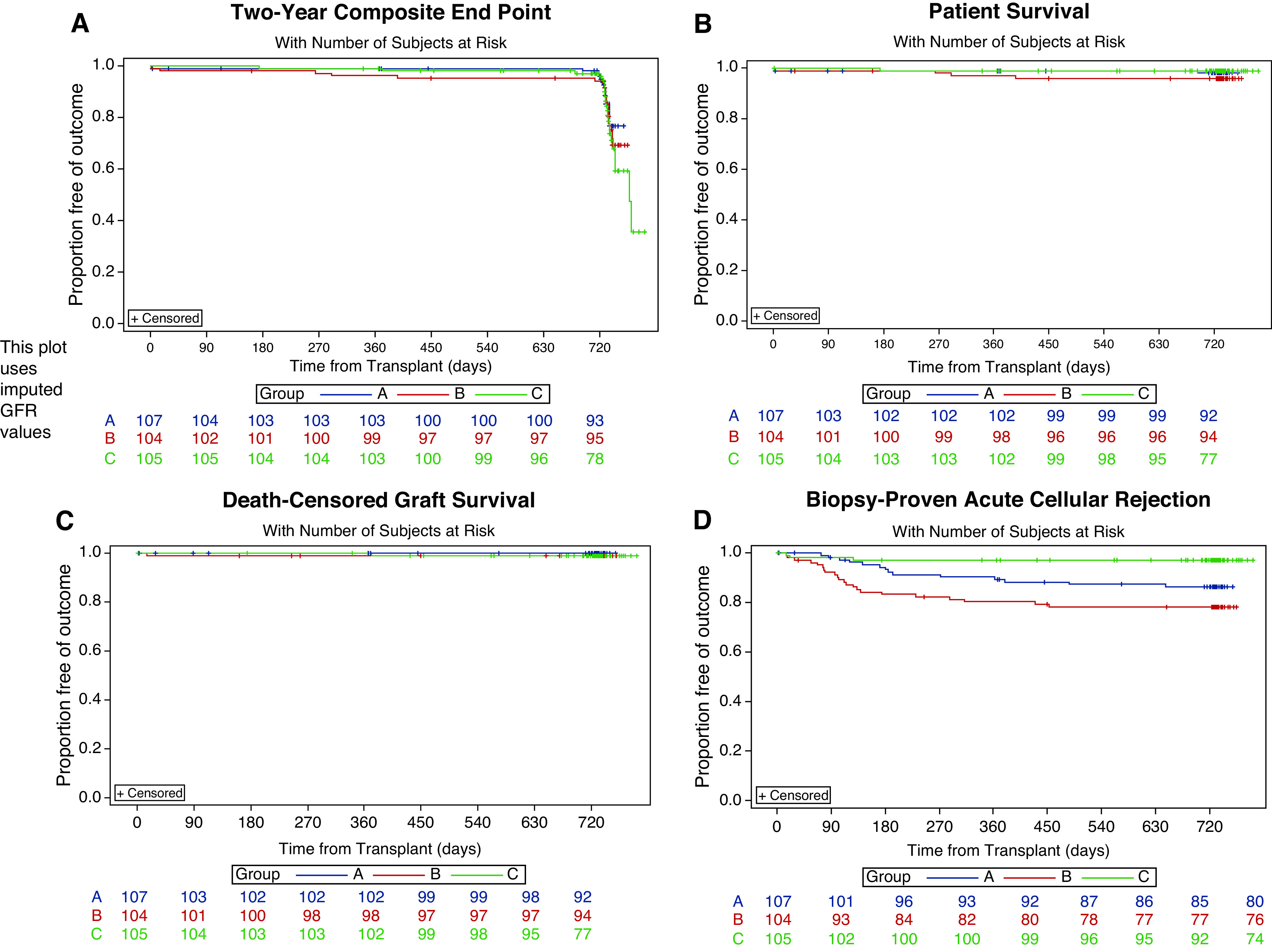

Two-Year Composite Outcome

The composite end point incidence for both belatacept-based groups did not differ from the tacrolimus-based group when follow-up was extended to 2 years post-transplant (Figure 2A). Improved outcomes in the belatacept/alemtuzumab versus tacrolimus/rATG (P<0.06) group were not observed (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of freedom from secondary end point, patient and graft survival, and biopsy sample–proven acute rejection (BPAR) at 2 years. (A) Primary composite outcome, (B) patient survival, (C) death-censored graft survival, and (D) freedom from biopsy sample–proven acute cellular rejection. Group A, alemtuzumab/belatacept; group B, rATG/belatacept; group C, rATG/tacrolimus.

Table 2.

Two-year outcomes of kidney transplant recipients in the Belatacept Early Steroid Withdrawal Trial

| Outcome | Group A Belatacept/ Alemtuzumab |

Group B Belatacept/ rATG |

Group C Tacrolimus/ rATG |

P Value (A versus C) |

P Value (B versus C) |

| Number of participants in ITT analysis | 107 | 104 | 105 | ||

| Primary composite outcome, n (%) | |||||

| Patient death, kidney allograft loss, or eGFR <45 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 11 (10) | 13 (13) | 22 (21) | 0.99 | 0.66 |

| Secondary outcomes, n (%) | |||||

| Death a | 2 (2) | 4 (4) | 1 (1) | 0.58 | 0.34 |

| Death-censored allograft loss a | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0.64 | 0.99 |

| eGFR (MDRD) <45 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 9 (8) | 8 (8) | 20 (19) | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| Biopsy sample–proven acute rejection a | 20 (19) | 26 (25) | 7 (7) | 0.009 | <0.001 |

| Biopsy sample–proven acute cellular rejection a | 14 (13) | 22 (21) | 2 (2) | 0.006 | <0.001 |

| Biopsy sample–proven antibody- mediated rejection a | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | 0.99 | 0.98 |

| Biopsy sample–proven mixed acute rejection a | 4 (4) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 0.30 | 0.38 |

| Rejection and donor-specific antibody, n (%) | |||||

| First biopsy sample–proven acute cellular rejection | |||||

| Grade 1 | 3/14 (21) | 5/22 (23) | 1/3 (33) | ||

| Grade 1b | 6/14 (43) | 5/22 (23) | 2/3 (67) | ||

| Grade 2a | 3/14 (21) | 7/22 (32) | 0/3 (0) | ||

| Grade 2b | 2/14 (18) | 5/22 (23) | 0/3 (0) | ||

| Grade 3 | 0/14 (0) | 0/22 (0) | 0/3 (0) | ||

| First biopsy proven acute cellular rejection Banff grade ≥2a | 5/107 (5) | 12/104 (12) | 0/105 (0) | 0.06 | <0.01 |

| Anti-lymphocyte antibody therapy for biopsy sample–proven acute rejection | 8 (8) | 15 (14) | 0 (0) | 0.007 | <0.001 |

| Corticosteroid-resistant, biopsy sample–proven acute cellular rejection | 4 (4) | 5 (5) | 0 (0) | 0.12 | 0.06 |

| De novo donor-specific antibodies at 2 yr | 0.75 | 0.07 | |||

| n participants with DSA/n tested (% DSA positive) | 5/90 (6) | 1/84 (1) | 5/74 (7) | ||

| Participants with HLA class I de novo donor-specific antibodies only, n | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Participants with HLA class II de novo donor-specific antibodies only, n | 5 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Participants with both HLA class I and II de novo donor-specific antibodies, n | 0 | 0 | 1 |

rATG, rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin; ITT, intention to treat; MDRD, Modification of Diet in Renal Disease; DSA, donor-specific antibodies.

a P values from the stratified log-rank test with the Hochberg adjustment was used to control for pairwise testing.

Secondary Outcomes

Prespecified secondary outcomes showed no statistically significant differences in death (Figure 2B) or death-censored graft loss at 2 years (Figure 2C). At the 2-year point, there were statistically significant differences in the eGFR <45 ml/min per 1.73 m2 outcome (belatacept/alemtuzumab versus tacrolimus/rATG, P=0.04; belatacept/rATG versus tacrolimus/rATG, P=0.05), which favored the belatacept treatment arms (<10% in either group versus >20% in the tacrolimus group; Figure 2D). Statistically significant differences in BPAR rates in both belatacept groups were observed. This was driven by higher rates of biopsy sample–proven acute cellular rejection. There were no differences in de novo donor-specific antibody rates, biopsy sample–proven antibody-mediated rejection, or biopsy sample–proven mixed antibody rejection. Table 2 details the secondary outcomes.

Death and Graft Loss Etiology

Causes of death included hemorrhagic shock and non–post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease (non-PTLD) malignancy acute myeloid leukemia (n=2, alemtuzumab/belatacept); PTLD, cardiac amyloidosis, cardiac death, and unknown etiology (n=4, rATG/belatacept); and blastomycosis (n=1, tacrolimus/rATG). Kidney allograft loss due to causes other than death included primary nonfunction (n=1, belatacept/rATG) and chronic allograft nephropathy (n=1, tacrolimus/rATG).

Kidney Allograft Rejection

Rejection severity, assessed by histology (Banff grade) and treatment (requirement for rATG treatment), was higher in belatacept groups. No participants in the calcineurin inhibitor treatment group showed rejection with a Banff grade of ≥2a, compared with 5% and 12% of participants in the belatacept/alemtuzumab and belatacept/rATG groups, respectively (Table 2).

Kidney Allograft Function

Analysis of mean or median eGFR values at 2 years did not reveal statistically significant differences between groups. The proportion of participants in each group did not differ with respect to eGFR-based CKD classifications. The absolute (and percentage differences) in mean eGFR changes at 2 years post-transplant between cohorts of recipients without and with rejection in the calcineurin inhibitor avoidance and calcineurin inhibitor treatment arms were 18.7 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (27%), 15.2 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (22%), and 24.9 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (38%) in the belatacept/alemtuzumab, belatacept/rATG, and tacrolimus/rATG groups, respectively. The proportion of participants in each treatment group with urine protein-creatinine ratios >0.8 at 24 months demonstrated a numeric improvement favoring the belatacept groups (11 of 84 [13%] participants in the alemtuzumab/belatacept group, five of 85 [6%] for rATG/belatacept, 21 of 84 [25%] for tacrolimus/rATG; P=0.08 for alemtuzumab/belatacept versus tacrolimus/rATG, and P=0.002 for belatacept/rATG versus tacrolimus/rATG; Table 3).

Table 3.

Kidney functional outcomes 2 years post-transplant in the Belatacept Early Steroid Withdrawal Trial

| Outcome | Group A Alemtuzumab/ Belatacept |

Group B rATG/Belatacept |

Group C rATG/ Tacrolimus |

P Value (A versus C) |

P Value (B versus C) |

| eGFR (MDRD) (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 0.92 | 0.92 | |||

| N | 98 | 95 | 98 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 66 (53–73) | 63 (53–78) | 64 (53–76) | ||

| eGFR (MDRD) (ml/min per 1.73 m2) in participants with biopsy sample–proven acute rejection | 0.43 | 0.40 | |||

| N | 20 | 26 | 7 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 53 (44–61) | 53 (45–63) | 48 (25–54) | ||

| eGFR (MDRD) (ml/min per 1.73 m2) in participants without biopsy sample–proven acute rejection | 0.61 | 0.99 | |||

| N | 78 | 69 | 91 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 67 (58–76) | 66 (57–80) | 66 (56–78) | ||

| Urine protein-creatinine ratio >0.8 (mg/mg) | 11/84 (13%) | 5/85 (6%) | 21/84 (25%) | 0.08 | 0.002 |

| Delayed graft function | 3/105 (3%) | 1/100 (1%) | 5/103 (5%) | 0.5 | 0.42 |

| Live donor recipients | 1/79 (1%) | 0/75 (0%) | 2/78 (3%) | 0.62 | 0.99 |

| Deceased donor recipients | 2/26 (8%) | 1/25 (4%) | 3/25 (12%) | 0.67 | >0.99 |

rATG, rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin; MDRD, Modification of Diet in Renal Disease; IQR, interquartile range.

Infection and Malignancy

Infection rates for any type of infection were similar between groups, with no statistically significant differences in rates of bacterial, viral, fungal, cytomegalovirus, or BK viral infections. PTLD occurred in only one participant treated with belatacept in the rATG/belatacept group. Central nervous system PTLD was not observed. Details are provided in Supplemental Table 1.

Maintenance Immunosuppression

Discontinuation rates for MMF and belatacept/tacrolimus and reinstitution rates for corticosteroid maintenance therapy did not differ between groups, and was approximately 10%±5% for each immunosuppressive agent at 2 years post-transplant (Supplemental Table 2). There were five participants who discontinued belatacept between the 12- and 24-month time points. The reasons included the need to travel out of the country for extended time, BPAR in two recipients, subsequent pancreas transplant received after 12 months, and participant preference due to distance from center. We performed a supplemental analysis to examine kidney allograft function in recipients in which belatacept was discontinued due to BPAR: the kidney function in these participants (for alemtuzumab, an eGFR of 45±19 ml/min per 1.73 m2; for rATG, an eGFR of 39±14 ml/min per 1.73 m2) was similar to that observed in those with rejection in the control arm (eGFR of 40±18 ml/min per 1.73 m2). Details are provided in Supplemental Table 3.

Adverse Events and Serious Adverse Events

No differences in rates of total serious adverse events (SAEs) were observed between groups. Increases in cardiovascular SAEs were observed in participants receiving rATG/belatacept: one (1%) SAE in the belatacept/alemtuzumab group, ten (10%) with belatacept/rATG, and three (3%) with tacrolimus/rATG. Of the participants in the belatacept/rATG group, one participant experienced angina on post-transplant day 27, three participants experienced coronary ischemic events (post-transplant days 148, 425, and 469), two experienced episodes of angina (post-transplant days 218 and 274), and one participant experienced sudden death (post-transplant day 395) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Serious adverse events and adverse events

| Event | Group A Alemtuzumab/ Belatacept (n=107) |

Group B rATG/ Belatacept (n=104) |

Group C rATG/Tacrolimus (n=105) |

P Value (A versus C) |

P Value (B versus C) |

| Serious adverse events | |||||

| Any, n (%) | 58 (54) | 66 (64) | 62 (59) | 0.27 | 0.26 |

| Total SAEs | 128 | 134 | 117 | ||

| SAEs per participant | 0.69 | 0.89 | |||

| N | 58 | 66 | 62 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–2) | ||

| Fatal | 2 | 3 | 1 | ||

| Life threatening | 1 | 3 | 0 | ||

| Result in disability/incapacity | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Result in hospitalization or prolonged hospitalization | 110 | 109 | 100 | ||

| Congenital anomaly/birth defect | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Medically significant | 24 | 34 | 19 | ||

| Cardiovascular event, n (%) | 1 (1) | 10 (10) | 3 (3) | 0.37 | 0.1 |

| Infection requiring hospitalization | 24 (22) | 24 (23%) | 23 (22) | >0.99 | >0.99 |

| Adverse events | |||||

| Any, n (%) | 91 (85) | 90 (87) | 92 (88) | >0.99 | 0.84 |

| AE per participant | 0.28 | 0.74 | |||

| N | 91 | 90 | 92 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 6 (2–12) | 6 (3–13) | 7 (4–12) | ||

| Hematologic | 59 (55) | 55 (53) | 60 (57) | 0.78 | >0.99 |

| White cell count <2000/mm3, n (%) | 22 (21) | 14 (14) | 15 (14) | 0.56 | >0.99 |

| Anemia (hemoglobin <8 g/dl), n (%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | >0.99 | >0.99 |

| Platelet count <50,000/mm3, n (%) | 5 (5) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 0.42 | 0.62 |

| Gastrointestinal, n (%) | 32 (30) | 34 (33) | 50 (47) | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Kidney, n (%) | 22 (21) | 28 (27) | 37 (35) | 0.04 | 0.23 |

| Neurologic, n (%) | 14 (13) | 14 (14) | 33 (31) | 0.002 | 0.003 |

| Electrolyte/metabolic, n (%) | 15 (14) | 21 (20) | 32 (31) | 0.01 | 0.11 |

| Wound healing, n (%) | 7 (7) | 10 (10) | 9 (10) | >0.99 | 0.82 |

| Musculoskeletal/bone, n (%) | 2 (2) | 6 (6) | 5 (5) | 0.55 | 0.77 |

Unless otherwise specified, values are provided as n or n (%). rATG, rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin; SAE, serious adverse event; IQR, interquartile range; AE, adverse event.

There were statistically significantly lower rates of neurotoxicity and gastrointestinal adverse events in the belatacept groups compared with the tacrolimus-based control group.

Discussion

Simultaneous avoidance of calcineurin inhibitors and corticosteroids under costimulatory blockade with belatacept-based regimens did not demonstrate superior composite outcomes (patient and graft survival and eGFR) when follow-up was extended to 2 years post-transplant, compared with the tacrolimus-based regimen.

When the composite of outcomes was examined separately, differences in kidney allograft function in terms of proportions of recipients with an eGFR of <45 ml/min per 1.73 m2 was improved at 2 years in both calcineurin inhibitor avoidance groups compared with the calcineurin inhibitor control group. This improvement emerged when the follow-up of study participants was extended to 2 years. Importantly, numeric improvements in proteinuria, favoring participants treated with belatacept, were also observed at 2 years. This may have even greater pathologic significance because belatacept does not cause the preglomerular arteriolar vasoconstriction that is known to be associated with calcineurin inhibitor therapy. Further research is needed to evaluate this possibility.

Because belatacept is non-nephrotoxic, calcineurin inhibitor regimens can be avoided, which could potentially improve long-term kidney allograft function. An important observation from the BENEFIT trial was that improvement in kidney function was observed at 7 years post-transplantation. Quantifying changes in kidney allograft function and how this parameter affected other organ systems and life span was an important consideration in evaluating the potential benefits of calcineurin inhibitor avoidance–based immunosuppression in BEST, as it was in the previous phase 3 BENEFIT trial. BENEFIT demonstrated consistent advantages over a 7-year period (13). In comparing BEST with the BENEFIT trial, it is important to understand that tacrolimus was used as the calcineurin inhibitor in BEST, as compared with the BENEFIT trial, in which cyclosporine was used. In BEST, no differences in kidney function were noted at 1 year, however, at 2 years, the proportion of participants with an eGFR of <45 ml/min per 1.73 m2 was lower in both belatacept groups. Similarly, numeric improvements favoring less proteinuria were observed in the belatacept groups.

BPAR and, more specifically, the rate and severity of biopsy sample–proven acute cellular rejection (by histologic criteria [Banff grade] and by treatment [proportion requiring rATG therapy]) were greater in the two calcineurin inhibitor avoidance groups as compared with the tacrolimus group. The rates of BPAR in each of the study cohorts at 2 years post-transplant were 19%, 25%, and 7%, in the belacept/alemtuzumab, belacept/rATG, and tacrolimus/rATG groups, respectively. It is important to note that, beyond 1 year, few differences in rejection rates were observed between groups. Specifically, the absolute increase in overall rates of BPAR from year 1 to year 2 was 3% (belacept/alemtuzumab), 3% (belacept/rATG), and 2% (tacrolimus/rATG).

Interestingly, at the relatively early time point of 2 years, the occurrence of rejection was not associated with a higher risk of kidney allograft failure and did not attenuate the quality of kidney allograft function in those in the calcineurin inhibitor avoidance treatment arms as much as the effect of rejection had in the calcineurin inhibitor treatment arm.

With respect to the type of rejection episodes that occurred, biopsy sample–proven antibody-mediated rejection and biopsy sample–proven mixed antibody-mediated rejection rates were similar and very low in all study groups. These are the two histologic types of rejection that are associated with adversely effects on kidney allograft survival (14). In addition, overall donor-specific antibody detection rates were very low in all groups. Longer-term follow-up will be important in defining whether an advantage of belatacept in reducing donor-specific antibody rates will occur under belatacept in BEST, similar to what was observed in BENEFIT and BENEFIT EXT trials (8,9,13,15).

Limitations of the study include a relatively short-term follow-up and an absence of protocol kidney allograft biopsies. In addition, it is important to note that the study population consisted of a relatively low immunologic risk population, with a high proportion of pre-emptive live donor transplants.

BEST has implications for a number of transplant-related toxicities. Rapid steroid withdrawal trials suggest that, in the long term, cardiovascular risk/events can be reduced and possibly improve cardiovascular survival. A strong rationale for pursuing calcineurin inhibitor avoidance/rapid steroid withdrawal protocols is to determine whether additional reduction in cardiovascular risk/events is possible (2). Further, calcineurin inhibitor avoidance/rapid steroid withdrawal should minimize drug-related toxicity, specifically neurotoxicity, gastrointestinal toxicity, and new onset diabetes after transplantation, thereby enhancing quality of life. Known, quantitative adherence with belatacept may minimize the effect of nonadherence on long-term kidney allograft loss.

A potential safety signal was observed with respect to cardiovascular events in the rATG/belatacept group. Detailed analysis of these events indicates that a majority occurred several months or later post-transplant, suggesting they may have been related to preexisting coronary artery disease. Further research is needed to evaluate this observation in participants treated with rATG/belatacept.

In summary, 2-year BEST results have indicated that relatively low immunologic risk kidney transplant recipients receiving simultaneous calcineurin inhibitor and corticosteroid avoidance using belatacept-based immunosuppression demonstrate a reduced risk of kidney function decreasing to <45 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and similar patient and graft survival rates. Interestingly, differences in cardiovascular toxicities were less distinct, although the gastrointestinal and neurotoxicity profiles were reduced. These results shed some light on the relative contributions of calcineurin inhibitors and corticosteroids as contributors. Although rejection episodes in BEST (as also in the BENEFIT trial) were of greater frequency and severity than with calcineurin inhibitor–based immunosuppression, it will be important to determine whether belatacept-based immunosuppression with T cell–depleting induction and early corticosteroid withdrawal will provide better long-term kidney allograft survival rates as has been observed in the BENEFIT trial.

Disclosures

R.R. Alloway reports serving on a speakers bureau for Astellas and Sanofi; receiving research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Hookipa, Nobelpharma, Novartis, and Sanofi; receiving honoraria from Sanofi and Veloxis; and having consultancy agreements with Veloxis Pharmaceuticals. D.B. Kaufman reports serving as a scientific advisor for, or member of, eGenesis and receiving research funding from Medeor Pharma and the National Institutes of Health. E.C. King reports having ownership interest in Procter & Gamble Company and STATKING Clinical Services. A. Matas reports receiving research funding from Alexion, Astellas, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CareDx, Shire, and Veloxis; receiving honoraria from Astellas, CareDx, CSL Behring, and Veloxis; serving as a scientific advisor or member of CareDx, CSL Behring, and Jazz Pharma; and having consultancy agreements with Veloxis. P. West-Thielke reports receiving research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, CSL Behring, Novartis, and Veloxis Pharmaceuticals; receiving honoraria from Veloxis Pharmaceuticals; and serving on a speakers bureau for Veloxis Pharmaceuticals. A. Wiseman reports serving as a scientific advisor for, or member of, American Journal of Transplantation; receiving research funding from Astellas, Bristol-Meyer Squibb, Hookipa, Medeor, and Novartis; having consultancy agreements with CareDx, Hansa, Mallinkrodt, Natera, Novartis, and Veloxis; serving on a speakers bureau for CareDx, Sanofi Genzyme, and Veloxis; and being employed by Centura Transplant. E.S. Woodle reports receiving research funding from Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Sanofi, and Veloxis; having consultancy agreements with, and receiving honoraria from, Novartis and Sanofi; and serving on a speakers bureau for Sanofi. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This study was supported by Bristol-Meyers Squibb (IM103-167).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

E.S. Woodle, R.R. Alloway, and A.R. Shields were responsible for study conceptualization; E.S. Woodle, D.B. Kaufman, R.R. Alloway, A.R. Shields, J. Leone, A. Matas, A. Wiseman, P. West-Thielke, and E.C. King were responsible for study design; A.R. Shields, R.R. Alloway, and E.S. Woodle were responsible for drafting and editing of the study protocol; A.R. Shields, E.C. King, and T. Sa were responsible for data analysis; D.B. Kaufman and E.S. Woodle drafted the manuscript; R.R. Alloway, A.R. Shields, J. Leone, A. Matas, A. Wiseman, P. West-Thielke, and E.C. King reviewed and edited the manuscript; E.S. Woodle was the overall study principal investigator; E.S. Woodle, D.B. Kaufman, J. Leone, A. Matas, A. Wiseman, and P. West-Thielke were the study site principal investigators; R.R. Alloway was the coordinating center director; and E.C. King was the study statistician.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: the BEST Study Group, Paul Brailey, Tonya Dorst, Alin Girnita, Amanda Naciff-Stahl, Jessica Thomas, Simon Tremblay, Kristi Schneider, Alyssa Stucke, Deborah A. Fernandez, Mary Farnsworth, Janis Cicerchi, Ann Cline, Kelly Bruno, Jessi Lipscombe, and Jennifer Rohan

Data Sharing Statement

This study began enrollment in October 2012 and did not include a data sharing plan or availability of information in the informed consent document. (1) No individual, deidentified participant data (including data dictionaries) will be able to be shared; (2) no data in particular will able to be shared; and (3) no additional, related documents will be available (e.g., study protocol, statistical analysis plan).

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.13100820/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1. Cardiac and infectious outcomes 2 years post-transplant in the belatacept early steroid withdrawal trial.

Supplemental Table 2. Immunosuppression in the belatacept early steroid withdrawal trial.

Supplemental Table 3. Immunosuppression conversion and kidney graft function.

References

- 1.Hibbs JLEJ, Alloway RR, Mogilishetty G, Govil A, Cardi M, Munda R, Woodle ES, Rike AH: Maintenance corticosteroid therapy is associated with an increased incidence of cardiovascular events in renal transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 9: 341, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Serrano OKKR, Kandaswamy R, Gillingham K, Chinnakotla S, Dunn TB, Finger E, Payne W, Ibrahim H, Kukla A, Spong R, Issa N, Pruett TL, Matas A: Rapid discontinuation of prednisone in kidney transplant recipients: 15-year outcomes from the University of Minnesota. Transplantation 101: 2590–2598, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woodle ES, First MR, Pirsch J, Shihab F, Gaber AO, Van Veldhuisen P; Astellas Corticosteroid Withdrawal Study Group: A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter trial comparing early (7 day) corticosteroid cessation versus long-term, low-dose corticosteroid therapy. Ann Surg 248: 564–577, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Humar A, Dunn T, Kandaswamy R, Payne WD, Sutherland DE, Matas AJ: Steroid-free immunosuppression in kidney transplant recipients: The University of Minnesota experience. Clin Transpl 2007: 43–50, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haller MC, Royuela A, Nagler EV, Pascual J, Webster AC: Steroid avoidance or withdrawal for kidney transplant recipients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (8): CD005632, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woodle ES, Alloway RR, Buell JF, Alexander JW, Munda R, Roy-Chaudhury P, First MR, Cardi M, Trofe J: Multivariate analysis of risk factors for acute rejection in early corticosteroid cessation regimens under modern immunosuppression. Am J Transplant 5: 2740–2744, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prashar R, Venkat KK: Immunosuppression minimization and avoidance protocols: When less is not more. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 23: 295–300, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vincenti F, Charpentier B, Vanrenterghem Y, Rostaing L, Bresnahan B, Darji P, Massari P, Mondragon-Ramirez GA, Agarwal M, Di Russo G, Lin CS, Garg P, Larsen CP: A phase III study of belatacept-based immunosuppression regimens versus cyclosporine in renal transplant recipients (BENEFIT study). Am J Transplant 10: 535–546, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Durrbach A, Pestana JM, Pearson T, Vincenti F, Garcia VD, Campistol J, Rial MC, Florman S, Block A, Di Russo G, Xing J, Garg P, Grinyó J: A phase III study of belatacept versus cyclosporine in kidney transplants from extended criteria donors (BENEFIT-EXT study). Am J Transplant 10: 547–557, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirk AD, Guasch A, Xu H, Cheeseman J, Mead SI, Ghali A, Mehta AK, Wu D, Gebel H, Bray R, Horan J, Kean LS, Larsen CP, Pearson TC: Renal transplantation using belatacept without maintenance steroids or calcineurin inhibitors. Am J Transplant 14: 1142–1151, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferguson R, Grinyó J, Vincenti F, Kaufman DB, Woodle ES, Marder BA, Citterio F, Marks WH, Agarwal M, Wu D, Dong Y, Garg P: Immunosuppression with belatacept-based, corticosteroid-avoiding regimens in de novo kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 11: 66–76, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woodle ES, Kaufman DB, Shields AR, Leone J, Matas A, Wiseman A, West-Thielke P, Sa T, King EC, Alloway RR; BEST Study Group: Belatacept-based immunosuppression with simultaneous calcineurin inhibitor avoidance and early corticosteroid withdrawal: A prospective, randomized multicenter trial. Am J Transplant 20: 1039–1055, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bray RA, Gebel HM, Townsend R, Roberts ME, Polinsky M, Yang L, Meier-Kriesche HU, Larsen CP: De novo donor-specific antibodies in belatacept-treated vs cyclosporine-treated kidney-transplant recipients: Post hoc analyses of the randomized phase III BENEFIT and BENEFIT-EXT studies. Am J Transplant 18: 1783–1789, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krisl JC, Alloway RR, Shield AR, Govil A, Mogilishetty G, Cardi M, Diwan T, Abu Jawdeh BG, Girnita A, Witte D, Woodle ES: Acute rejection clinically defined phenotypes correlate with long-term renal allograft survival. Transplantation 99: 2167–2173, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vincenti F, Rostaing L, Grinyo J, Rice K, Steinberg S, Gaite L, Moal MC, Mondragon-Ramirez GA, Kothari J, Polinsky MS, Meier-Kriesche HU, Munier S, Larsen CP: Belatacept and long-term outcomes in kidney transplantation. N Engl J Med 374: 333–343, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.