Significance Statement

In the United States, dialysis provision is an example of a robust, single-payer dominant system with cost containment. When compared with the cost of dialysis in other countries, Medicare dialysis costs in the United States as a function of overall health care expenditures are approximately $60,000 per patient less than expected, likely due to substantial cost containment imposed by Medicare as the dominant payer.

Keywords: ESRD, single payer, dialysis, health economics, health care costs

The United States spends more per capita on health care than every other country in the world.1 Proponents of a single-payer system in the United States contend that one potential benefit could be a reduction in total health care costs. However, examining this concept is challenging in the United States because of the current complicated multipayer system.

Maintenance dialysis is a unique health system in the United States because most patients, regardless of age, are insured by Medicare. In 2018, approximately 85% of 554,000 patients receiving dialysis in the United States were insured by Medicare, and most had Medicare fee-for-service as primary coverage.2 Therefore, maintenance dialysis is an example of a robust single-payer dominant system in the United States. This study evaluates the association of this single-payer dominant system with total health care costs by examining dialysis-specific expenditures as a function of total health care expenditures in the United States compared with other countries.

International dialysis reimbursement data for the year 2016 were obtained from a previously published cross-sectional survey of nephrologists from 80 other countries who estimated the reimbursement for a single hemodialysis session.3 This was multiplied by 156 (three hemodialysis treatments per week per year) to estimate the annual dialysis cost. Nephrologists did not specify if the physician supervision fee was included. Health care expenditure per capita in 2017 was collected from the World Health Organization Global Health Expenditure Database.4 Our final analysis included 71 countries plus the United States; nine countries were excluded for absent health expenditure data, and one (Costa Rica) was excluded for high standard residual on initial modeling.

The association between the cost of dialysis and a country’s health care expenditure (excluding the United States) was calculated using a Pearson correlation test and fit to a univariate linear regression model to predict the expected cost of dialysis in the United States and its associated prediction interval. This projected cost was examined in relation to the actual cost of dialysis in the United States, which was derived from the Medicare Prospective Payment System 2020 Final Rule. Actual costs included a US$239 facility fee per session (reimbursement per session varied from US$230 to US$239 between 2014 and 2020) and US$240 supervising physician fee per month, assuming that Medicare reimbursed 100% of allowable charges.5 Analyses were conducted using R, version 4.0.3.

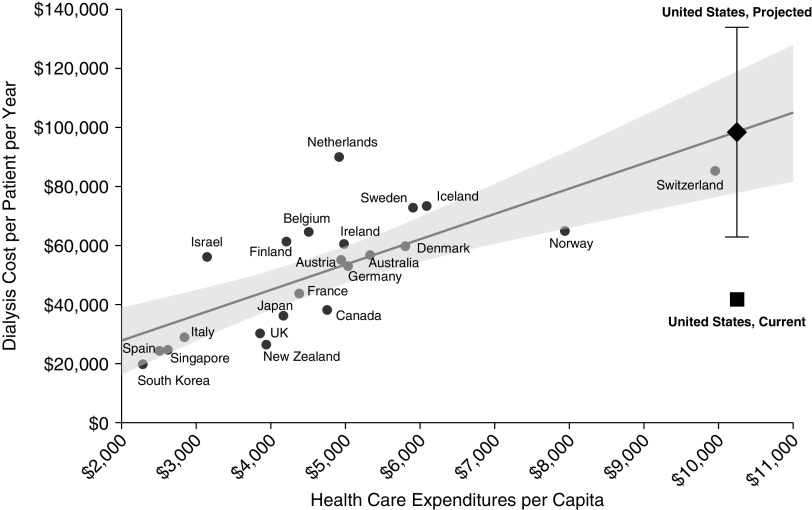

The estimated annual cost for dialysis ranged from US$1560 (Cameroon) to US$89,958 (Netherlands). Health care expenditures per capita ranged from US$24 (Burundi) to $10,246 (US) (Supplemental Table 1). There was a strong correlation between a country’s dialysis cost per patient and its health care expenditure per capita, both when limiting analyses to only higher income nations identified as those with at least $2000 in per capita health care expenses (Pearson r, 0.75; 95% confidence interval, 0.47 to 0.89, P<0.001; Figure 1) and when evaluating all nations (Pearson r, 0.92; 95% confidence interval, 0.87 to 0.95, P<0.001; Supplemental Figure 1). Using these models, the predicted annual dialysis cost per patient in the United States is US$98,410 (95% prediction interval, US$62,827–US$133,994) and US$101,385 (US$82,490–US$120,279) when evaluating wealthier nations and all nations, respectively. Assuming 156 sessions per year, the actual annual dialysis cost per patient in the United States is approximately US$40,000, less than half of the predicted payment (Figure 1). Similar results were seen in a sensitivity analysis limited to high income countries and exploring single versus multipayer systems (Supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Linear regression of dialysis costs and health care expenditures of 22 countries with per capita health care expenditures of at least US$2000 and the United States. The shaded area represents 95% confidence interval, excluding the United States from regression models. Error bar represents 95% prediction interval of US cost of dialysis per patient per year.

This study demonstrates the annual cost of dialysis per patient in the United States is approximately US$60,000 below its predicted cost. Considering that approximately 550,000 patients currently receive maintenance dialysis in the United States, this equates to a more than US$33 billion difference in expenditures if all patients on maintenance dialysis in the United States had Medicare fee-for-service coverage and dialysis costs paralleled other United States health care costs. The extensive difference in cost compared with typical health care expenditures in the United States suggests these findings may relate to the effects of a quasi–single-payer system controlling the rate of reimbursement. Future research could further evaluate the effects of a single-payer system in the United States by comparing these results to procedures reimbursed by multiple payers.

Rising health care costs contribute to higher premiums and long-term financing challenges. A single-payer system may have a strong influence over cost containment because dialysis providers have fewer bargaining capabilities with a large homogenous payer, such as Medicare, and fewer opportunities to cost-shift to other payers on the basis of market power.6 More broadly, on the basis of the example of dialysis, a single-payer system could be an effective strategy to limit total healthcare spending in the United States. Critically, however, a single-payer system leading to cost containment may have tradeoffs, including reducing incentives for new technology and innovation, limiting pay for health care professionals, and reducing patient access to care.5,7

This study has several limitations. First, international dialysis reimbursement data are self-reported, provided by a single representative of each country. Actual reimbursement may vary on the basis of geography or practice. Second, assessment of dialysis costs may also vary depending moderately on the respondent’s inclusion or exclusion of nephrologist fees, medications, or laboratory tests. In determining costs in the United States, both nephrologist charges and dialysis provision charges, including erythropoiesis stimulating agents, were included; this approach likely includes as many or more elements of dialysis care than most other included countries. Third, international cost estimates are from 2016 and may underestimate current costs due to inflation or recent policy changes. Underestimation would imply the difference between actual and predicted dialysis cost in the United States is greater than presented here.

In conclusion, the single-payer infrastructure of maintenance dialysis in the United States may contribute to cost containment. Evaluating this relative to potential disadvantages of cost containment requires further analyses.

Disclosures

D. Weiner is a member of the Quality Committee and the Policy and Advocacy Committee of the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) and is the Medical Director of Clinical Research for Dialysis Clinic, Inc. (DCI); reports having consultancy agreements with Tricida (2019), Cara Therapeutics (2020), Janssen Biopharmaceuticals for participation in Medical Advisory Boards (2019); reports receiving honoraria from Akebia (2020, 2021) paid to DCI; reports receiving research funding paid to author’s institution via Dialysis Clinic, Inc. (local site principal investigator [PI] for clinical trials contracted through DCI sponsored by Ardelyx (ongoing) and Cara Therapeutics (completed)) and for trials sponsored by AstraZeneca (site PI, capitated on the basis of recruitment, completed 2020), Goldfinch Bio (site PI, capitated on the basis of recruitment, ongoing), and Janssen Biopharmaceuticals (site PI, capitated on the basis of recruitment, completed 2019); reports receiving honoraria from the National Kidney Foundation (NKF) for an editorial positions at Kidney Medicine and the American Journal of Kidney Diseases, Elsevier for royalties from the NKF's Primer on Kidney Diseases; reports being a scientific advisor or member as ASN representative to KCP; Scientific Advisory Board for National Kidney Foundation; and having other interests/relationships as chair of the adjudications committee for the Evaluation of Effect of TRC101 on Progression of Chronic Kidney Disease in Subjects With Metabolic Acidosis (VALOR-CKD) Trial (George Institute), and Member of Data Monitoring Committee, “Feasibility of Hemodialysis with GARNET in Chronic Hemodialysis Patients with a Bloodstream Infection” Trial (Avania). All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

All authors are responsible for the data acquisition, data analysis/interpretation, and the statistical research idea and study design; D. Finch is responsible for the analysis; D. Weiner provided supervision and mentorship. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and agrees to be personally accountable for the individual’s own contributions, and to ensure questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work, even one in which the author was not directly involved, are appropriately investigated and resolved, including with documentation in the literature if appropriate. Special thanks to Dr. Raymond Vanholder, from the Department of Internal Medicine at Ghent University Hospital, for assistance with data acquisition and conceptualization.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

See related editorial, “Comparative health care spending for dialysis: An example of public cost containment?,” on pages 2103–2104.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2021010082/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1. Estimated dialysis reimbursement data and health care expenditure data.

Supplemental Figure 1. Dialysis costs and health care expenditures.

Supplemental Figure 2. Dialysis costs and health care expenditures among wealthier nations, stratified by payer system.

References

- 1.Papanicolas I, Woskie LR, Jha AK: Health care spending in the United States and other high-income countries. JAMA 319: 1024–1039, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.United States Renal Data System: USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States, 2020. Available at: https://www.usrds.org/annual-data-report. Accessed June 18, 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Tol A, Lameire N, Morton RL, Van Biesen W, Vanholder R: An international analysis of dialysis services reimbursement. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 84–93, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization Global Expenditure Database: Current health expenditure per capita (current US$). Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.CHEX.PC.CD. Accessed June 6, 2020

- 5.Mendu ML, Weiner DE: Health policy and kidney care in the United States: Core curriculum 2020. Am J Kidney Dis 76: 720–730, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee JS, Berenson RA, Mayes R, Gauthier AK: Medicare payment policy: Does cost shifting matter? Health Aff (Millwood) 22: W3-480–8, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baicker K: Trade-offs in public health insurance design. JAMA 325: 814–815, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.